ABSTRACT

Quantification is a central instrument of tourism governance, as numbers are perceived as a solid factual basis for action. However, critical studies of quantification reveal the political, performative and constructed nature of statistics. Adopting this perspective, we offer an original methodological and conceptual framework for the analysis of tourism quantification systems. The framework includes the mapping of actors and datasets, ethnomethodological observation applied to statistical work, and discourse and controversy analysis. Such an investigation illuminates how the production of quantitative knowledge reflects and is embedded in power structures and power shifts in the tourism sector. It also allows to study quantitative observation as part of the sector's response to contemporary challenges, such as overtourism, the rise of big data, or sustainability.

Introduction

Tourism policy reports, tourism industry annual reports, academic papers in tourism research: all these routinely begin with a series of striking figures, generally intended to convey the global importance of the phenomenon, its growth dynamics and potential – or, on the contrary, in recent years, its spectacular halt due to the pandemic. Indeed, numbers and statistics are viewed as a powerful and reliable way of stating facts, in tourism as in many other areas of contemporary societies (Desrosières, Citation2008; Porter, Citation1995). Historically, the institutionalised production of statistics has accompanied and enabled the structuring of political entities, first and foremost the state (Desrosières, Citation1998), and has early on been concerned with the international coordination of statistical categories and rules (Cussó, Citation2020; Randeraad, Citation2011). The same can be said for tourism: statistics have played a key role in structuring tourism as an economic sector and policy domain, and have been the subject of much work in international institutions to ensure comparability (see, for instance, the UNWTO's International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008).

Rather than using statistics and data as mere tools, social sciences need to make them a central object of critical inquiry. This is the central assumption of critical studies of quantification (Desrosières, Citation1998; Espeland & Stevens, Citation2008; Porter, Citation1995), and the perspective that we adopt here. Indeed, the role of statistics and data in the construction of social structures is far from being simply a technical matter. Statistics are an instrument of government in the Foucauldian sense, as they participate in the establishment of norms and classifications, and allow a certain degree of control over heterogeneous realities, individuals or entities. It is therefore crucial for social sciences to account for the situated nature of these norms and classifications, that is to say, to examine the social processes that lead to their definition. Some of the processes of definition of quantitative indicators are highly controlled by the state or coalitions of states, such as the definition of tourism by the United Nations, which explicitly aimed to better control international population movements (United Nations Economic and Social Council, Citation1956). Other processes rather result from the competition between economic actors, such as the proliferation of rankings and performance indicators in the neoliberal era, which produce order through reactive behavioural change (Espeland & Sauder, Citation2007). Technological changes may also generate new quantitative data, which can subsequently reconfigure relations between actors. Examples are the emergence of online consumer-based ratings of tourism services and products (Orlikowski & Scott, Citation2014), and the new regime of knowledge advocated by ‘big data’ analysis (Weaver, Citation2021). The critical perspective applies to all quantification apparatuses, from the newest data sources to long-standing international norms for tourism statistics.

In all these cases, the critical analysis of tourism quantification procedures allows for the identification of the underlying stakes and leading forces at play: for instance, state control, or market dynamics, or socio-technical reconfigurations. In other words, the critical analysis of tourism quantification aims to uncover who controls the quantification instruments and to what purposes they are made. Tourism industry actors can benefit from a better awareness of the power relations in the production of tourism quantitative data. Such awareness may prompt them to request greater transparency from their data providers regarding quantification procedures, and to assess the alignment of data providers with their needs and interests, particularly when the providers are external to the tourism sector; or even prompt them to engage in their own quantification procedures. But to date, very little research has addressed the broader politics of statistics and numbers in tourism, as we will develop in the next section; this paper aims to contribute to this effort on the methodological level.

The main aim of the paper is to offer an original methodological and conceptual framework for mapping and analysing tourism quantification systems at different geographical levels. Tourism quantification systems can be defined as interrelated actors and sources that produce and disseminate tourism statistics on a specific area or destination. The term quantification refers to a process that includes not only measurement but also all the social and technical operations necessary to define measurement categories and rules, such as ‘conventions of equivalence’ (Desrosières, Citation1998) or operations of ‘commensuration’ (Espeland & Stevens, Citation1998). Thus, to speak of quantification points to the fact that statistical instruments and institutions are always the result of negotiations aimed at meeting policy and business intelligence needs as best as possible, but also reflect power relations within a field. Hence, mapping and analysing tourism quantification systems is of great relevance for both tourism research and the tourism industry, as it provides insights into the structuring processes, but also the current states of tourism fields – from local destinations to the international tourism system. The paper proceeds as follows:

After reviewing the ‘state of tourism research’ in terms of critical approaches to the role of knowledge and statistics, we provide a ‘theoretical framework’ centred on the social sciences of quantification in next section. We then proceed to the main part of the paper i.e. ‘a methodological framework for the critical analysis of tourism quantification systems’. This methodological protocol was initially developed within a research project focused on the comparative analysis of tourism quantification systems in three European countries (Italy, Switzerland and France) and several cities. The methodological protocol includes ‘mapping quantification systems’ and ‘ethnomethodological observation of statistics-making’ sections where short examples drawn from this project will illustrate some of the proposed methods and their application. The project also focuses on ‘overtourism’ as a controversy involving acts of tourism quantification and/or discourses on tourism quantities. We will use this case to offer methodological reflections on the use of tourism statistics or figures in public debates in ‘statistical discourses or tourism statistics in the public arena’ section.

Our proposition opens up a new area for tourism research, where statistics have been scrutinised and criticised, but quantification systems and processes have not yet been. We argue that tourism research cannot afford to ignore such a central aspect of tourism governance and structuration. Moreover, the methodological framework we propose could help tourism professionals to reflect on their data needs and strategies.

State of research

Techniques of knowledge in the structuring of tourism

The very existence of tourism studies as a field of research depends on the recognition of a certain coherence of tourism; as a significant social practice, and as a professional and economic sector. Part of the effort of the social sciences in the study of tourism has therefore been to give an account of how the various realities and actors of tourism ‘hold together’ or work together to, for instance, shape a destination, or regulate work practices in the hospitality sector. This question has been addressed in particular by studies of governance, characterised, for instance, by Bramwell and Lane (Citation2011, p. 412): ‘The processes of tourism governance are likely to involve various mechanisms for governing, “steering”, regulating and mobilising action, such as institutions, decision-making rules and established practices.’ The study of such processual and relational ‘mechanisms’ has been carried out, in tourism research, through the lens of actor-network theory (ANT) in particular (Jóhannesson, Citation2005; van der Duim et al., Citation2013). ANT is used as a tool to study how collectives are made and maintained in tourism, through processes of translation (the making of common objects across heterogeneous perspectives) and processes of ordering (conventions, classifications, rules …), as outlined by Franklin (Citation2004).

As a central component of such processes, knowledge has been a major focus of tourism studies. Cooper (Citation2015) emphasised the importance of knowledge management for tourism destinations and organisations, while ‘social learning’ was analysed as an essential component of resilient tourism governance (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2011; Islam et al., Citation2018). At the regional or local level, tourism-specific knowledge networks (Dredge, Citation2015) are integral to the elaboration of tourism policies. Indeed, knowledge of the tourism phenomenon, its characteristics and processes, is an essential component of the contemporary actions of both the tourism industry and public authorities. However, while the literature cited above has insisted on interactions within these networks and on translation processes to elaborate common objects of work, very few authors have delved into the actual processes of knowledge-making in terms of elaborating categories of understanding, observation, or measurement. Exceptions include Dredge (Citation2015), who shared insights on knowledge sources, epistemic discussions and boundaries within a tourism policy planning process; and Font et al. (Citation2021), who closely followed the elaboration and assimilation of indicators for sustainable tourism, at the European and destination levels. Overall, however, critical examination of knowledge categories and knowledge-making practices in tourism is lacking. This examination is particularly timely given the crucial current debate on technological assemblages as modes of governance in tourism (Dredge & Gyimóthy, Citation2015). Big data and algorithms are indeed new and powerful ways of extracting and processing knowledge, in opaque ways (Smith, Citation2020) that take away some of the control over knowledge resources from many other actors, and as such are likely to reconfigure power relations in the structures of tourism.

Critical perspective on tourism statistics

Scientific commentary, critiques and suggestions have accompanied the development and international standardisation of tourism statistics. When both the UNWTO and Eurostat were developing international standards for tourism statistics in the 1990s, tourism scholars closely followed this work and shared concerns and recommendations regarding reliability and comparability (Bar-On, Citation1991; Hannigan, Citation1994; Terrier, Citation2006; Wöber, Citation2000). Since then, tourism research has continuously provided critical and constructive reports, either to improve these statistics or to highlight their gaps and shortcomings (Adamiak & Szyda, Citation2022; Antolini & Grassini, Citation2020; Batista e Silva et al., Citation2018). Problems of blind spots and underestimations have been highlighted, especially in accommodation statistics (De Cantis et al., Citation2015; Guizzardi & Bernini, Citation2012; Van Truong et al., Citation2022; Volo & Giambalvo, Citation2008); serious limitations in the comparability of international statistics have been pointed out, due to different sources and indicators, or to discrepancies in the application of regulations, including in the European Union (Antolini & Grassini, Citation2020); in economic statistics, the methodology of the tourism satellite account has been detailed (Frechtling, Citation2010), and criticised for its narrow view of tourism-related value added (Smeral, Citation2006); technological innovations to improve the measurement of tourism mobility and presence, in particular GPS tracking and mobile positioning data, have been extensively discussed (Mashkov & Shoval, Citation2023; Nyns & Schmitz, Citation2022; Saluveer et al., Citation2020; Vanhoof et al., Citation2017)

Overall, there is a wealth of research on statistical aspects of tourism statistics, that is to say, technical and institutional issues related to quality, reliability, completeness, standardisation or improvement; but much less research on socio-political aspects of tourism statistics. Such a research effort implies addressing how tourism statistics are embedded in policy structures and programmes and how they contribute to shaping the social reality of the tourism phenomenon. Such a perspective implies a critical look not only at the biases and gaps in tourism statistics, but more fundamentally at the very categorisations and conventions on which these statistics are based. This allows, for instance, to highlight the geopolitical dimension of international tourism figures and their contested geographical delineations (Pratt & Tolkach, Citation2018). More generally, contemporary, internationally standardised tourism statistics are narrowly constrained by ‘methodological nationalism’ (Stock et al., Citation2020, chapter 2); and at all scales they are subject to all sorts of manipulations permitted by the choice of the geographical scale of observation, generally with the aim of presenting the largest possible numbers and appearing well in the various rankings of countries or destinations. A second major avenue of critique, which is still barely explored, is the role of the tourism industry in shaping tourism statistics. The UNWTO's definitions of tourism concepts are not only suited to statistical purposes, but also tailored to an economic view of tourism that prioritises the ‘supply’ side of the phenomenon (Stock et al., Citation2020, chapter 2). The recent enthusiastic embrace of big data sources to monitor tourism demand can also be read as a profit-driven, industry-led trend towards economic modelling – i.e. a quantitative simplification – of tourism practices (Weaver, Citation2021).

Theoretical framework

Quantification is politics

The methodological proposition that we develop below is based on a central postulate: tourism statistics co-constitute the reality of tourism. Indeed, they are an essential part of what we know and how we know about tourism and, consequently, key to the governance structures of the tourism field. Such a postulate is a direct application of the central tenets of the sociology of quantification: statistics ‘not only count, but constitute’ their objects (Espeland & Stevens, Citation2008, p. 405); as such, they are both a tool of evidence and a tool for governing (Desrosières, Citation2008, chapter 1). As a field of research, the sociology of quantification provides a critical analysis of the production and use of numbers in society by contextualising quantification practices and revealing the many roles and functions that numbers have in everyday politics (Alonso & Starr, Citation1987; Bruno et al., Citation2016). In tourism, this can mean paying attention to how tourism statistics are designed to serve government or industry purposes, or how they are used to guide or perform action, for instance in destination management or market regulation.

Quantification is a practice

Understanding the structuring and performative role of statistics in society requires a detailed analysis of the webs of relations, of social and institutional conventions, of mundane and professional practices, that are involved in the production and dissemination of these statistics. Such a constructivist stance draws in part on science and technology studies, which have developed detailed ethnographic and pragmatic accounts of knowledge-making work (Knorr-Cetina, Citation1981). However, accounts of knowledge in-the-making need to be completed with the ‘historicisation and sociologisation of statistical tools’ that Bourdieu already advocated in the 1960s (Desrosières, Citation2008, p. 296) in order to fully understand the politics of quantification (Gephart, Citation1988). Moreover, the study should not be limited to the producers of statistics, but should be extended to all other professional practices, or political issues, where statistics can exert power. This means, in particular, paying attention to the diffusion of new computational methods and quantitative instruments within professional sectors, as they have the potential not only to change work practices, but also to profoundly alter the broader goals of an activity, as the many contemporary cases of financialisation of professional sectors show (Bardet et al., Citation2020).

Between constructivism and realism

Adopting a critical perspective on the making of tourism statistics does not mean discarding them as worthless. Instead, we embrace Desrosières's constructivist-realist view: ‘Statistical tools allow the discovery or creation of entities that support our descriptions of the world and the way we act on it. Of these objects, we may say both that they are real and that they have been constructed, once they have been repeated in other assemblages and circulated as such, cut off from their origins’ (Desrosières, Citation1998, p. 3). The ‘reality’ of statistics is therefore not to be understood as a degree of truth in the representation of society, but rather as a degree of confidence in its efficacy to act in society. The reality of statistics is the sum and scope of the collective investments that rely on them: the more actions and organisations they support, the more ‘real’, or rather robust, they are. Tourism statistics may be partial and imperfect, they nonetheless result from the coordination efforts of many different entities and serve as a reference for many strategies and policies. They are real for the field of tourism in the sense that they act in it.

Methodological framework for a critical analysis of tourism quantification systems

The combination of methods we present in this section is primarily aimed at analysing how tourism quantification systems are structured and how they work; on the one hand, what are their main actors, tasks, statistical sources and outputs, and data flows, and on the other hand, what are the work practices within these systems, with which rules and underlying assumptions, and by which people and professions. Additionally, we offer methodological propositions for analysing how tourism quantification systems are involved in statistical discourses in the public arena – discourses where non-expert, vernacular voices may meet or confront official, professional ones. Thus, the methodological framework proposes, first, a mapping protocol; second, a set of methods inspired by ethnostatistics, a form of ethnomethodology applied to statistical work; and third, mixed qualitative methods focused on discourse analysis and controversies. The three methodological approaches are best applied in a simultaneous and mutually reinforcing way. Some of the main methods, in particular interviews, are designed to provide material for all parts of the framework, with necessary adaptation depending on the relative position of the actor being interviewed within or towards the tourism quantification system.

Mapping quantification systems: the structures of statistics-making

In order to develop a functional description of what we call a ‘tourism quantification system’, a systematic inventory and characterisation of statistics producers and aggregators is carried out and presented in a visual form, as diagrams or ‘maps’. These maps represent the actors, the datasets and the relationships between them. We consider tourism quantification systems to be structured mainly by the actors who produce, aggregate and/or publish statistics directly relevant to tourism. The respective diagrams therefore do not represent the final users or consumers of these statistics.

Documentary collection and actor/expert interviews

The first step in the process is to identify the main datasets and actors that have an interest or are involved in the production, aggregation or transmission of tourism statistics. It relies on (1) the collection of published documents on tourism statistics (from which the organisations publishing data and their roles can be identified) and (2) interviews with key individuals who work in these organisations, and thus have a central role in the tourism quantification system.

The documentary research is mainly carried out online, starting with an inspection of the websites of the main organisations producing or transmitting tourism statistics, and the documents and reports they publish. Moreover, a keyword-based research in online search engines can help to find possible additional sources of tourism statistics. This first step provides a general view of the main channels and formats for communicating statistics: databases or data tables, statistical compilation, regular or one-off analytical reports, online dashboards, etc. Publicly available statistics on tourism make it possible to get a first solid picture of tourism quantification systems, be it at national, regional or city level. By following the ‘flow’ of data (transmission between actors), the research must then be completed by tracking and including the private companies and non-profit organisations that produce and process data for purposes other than public administration (e.g. commercial activities or political activism). Data products commercialised by private companies may be included depending on their relative centrality in the tourism quantification system; that is to say, if they appear to be an important resource for a sufficient number of actors and organisations.

The professionals identified through the documentary collection as the authors or editors of the statistics are then contacted for interviews. summarises the interview protocol developed for our project, structured around four key points that can form the basis for the study of any quantification system: 1. the role of the actor, 2. the quantified objects and quantification methods, 3. the relationships between the actors in the tourism quantification system, and 4. their perception of the influence and the impact of their work – especially in relation to the specific theme or issue under study, in our case overtourism.

Table 1. Simplified interview protocol.

The interviews are a key part of the methodological framework and serve several purposes. The first is to clarify and complete the structure of the quantification system, in particular through points 1 and 3 of the interview guide. The first interviews make it possible to draw up a draft ‘map’ of the quantification system by identifying the organisations, their roles, the data produced and their uses. Gradually, as the interview campaign progresses, the map is refined: important actors and datasets that did not appear in the documents collected can be added, and the triangulation of sources gives a more precise idea of the relative importance of the different elements of the system. Such a map also leads directly to a list of organisations and individuals to be interviewed. Finally, the quantification system may need to be delimited by excluding the least important elements or those that are only remotely related to tourism.

Point 2 of the interview protocol contributes to the functional description of the quantification system with additional, precise information; but it also provides initial material for the ethnomethodological analysis (see ethnomethodology section) by questioning work practices. Finally, point 4 of the interview protocol is also designed to provide material for discourse and controversy analysis (see statistical discourse section) by allowing key actors of the quantification system to express their views on the contribution of their work to social organisation and social and political issues.

Inventory and mapping

The second phase aims to characterise the actors and datasets identified in the first phase and to classify them according to categories and criteria in line with the critical analysis of the tourism quantification system:

Descriptive ‘portraits’ define the main attributes of the actors and datasets. These portraits include at least their mission, organisational structure, position within the tourism quantification system, main datasets produced, channels of publication and access. Such a description, based almost exclusively on the actor's self-representation through official documentation or interviews, offers no critical distance, but is nevertheless an essential starting point. Portraits of datasets include at least the type of data (survey, registry, database …), the main themes and variables, the status (public, private, open …), and the format in which it is available.

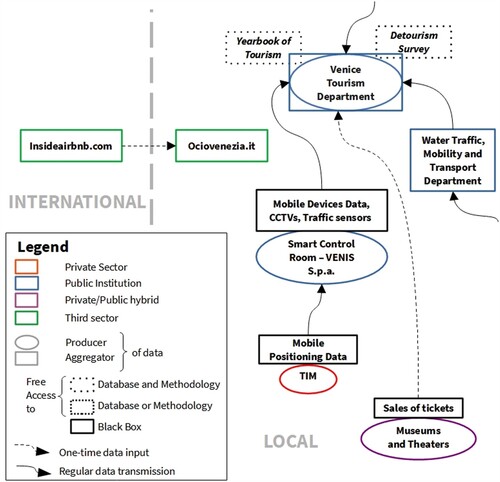

The relationship diagrams (the ‘maps’) outline the relationships between actors and datasets and, more generally, present the tourism quantification system in a visual form, representing a condensed selection of the main elements of the system and the relations between them – i.e. the circulation of the data. shows an example of such a map. Graphical choices have to be made in order to represent a selection of the main parameters or typologies of the system. These choices are explained in the following paragraphs. While some parameters are essential for the analysis of any quantification system, others may depend on the specific research questions or topics. Of course, different maps may be drawn to represent different aspects of the same system.

The status of the organisation is a first parameter that is often essential to characterise actors. Possible statuses include public, private sector, public-private partnership and not-for-profit organisation. They correspond to different goals or missions that are directly relevant to the politics of quantification. Public producers of statistics are mandated by governments to produce and disseminate publicly relevant and publicly accessible knowledge. Business entities, on the other hand, produce statistics or data mostly as commercial products or assets in business strategies. Public-private partnerships act as intermediaries between the needs of the public and private sectors, usually to facilitate the circulation of data of common interest. Finally, non-profit (or ‘third sector’) organisations may aggregate or publish statistics for a variety of purposes, such as political activism. Status largely determines the relations an actor has with other actors in the quantification system, and the resulting power relations: hierarchy, cooperation, competition, dependency, centrality, etc.

The role in the quantification process is a second key parameter for describing quantification systems. As noted above, quantification is a social process that begins with the definition of indicators and calculation rules, includes the collection of data shaped by these categories and rules, and results in the communication of quantitative information through these ordered and standardised data. The most central role is played by the producers of statistics or data, that is to say the actors involved in the definition, collection and calculation of the quantitative datasets, and generally also in their publication. National statistical institutes, statistical offices of large companies or organisations, and some NGOs or activist organisations assume such a role. A second essential and common role is that of the data aggregators, who compile data from different sources and publish or make them available to their partners or clients in a form that serves certain specific purposes, such as knowledge of a policy or business area, or the formulation of a discourse on a public issue (overtourism, for instance). As mentioned above, we limit the quantification systems to these two main roles, producers and aggregators. Other roles, and in particular the variety of end-users of statistics and data, are of course essential to the functioning of the system, and their influence is in many cases worth analysing; but they remain outside of the ‘map’ of the quantification system as they do not take part in the quantification process.

The scale of quantification is a third important parameter for the organisation of such systems. The actors of quantification are classified according to their main geographical level of action, that is to say according to the scale of the territory on which they produce data, or within which they publish and disseminate data. Some actors may occupy an intermediate position, for instance when they are in charge of the circulation of data between the local/regional level and the national level. Some actors seek to operate strategically at different levels, for instance platform companies when they try to negotiate rules with national or supranational governments and at the same time negotiate and/or exchange data with local authorities. Representing actors and datasets at different scales allows us to highlight how power relations in quantification systems are embedded in spatial relations and in the ability to influence or participate in the production and circulation of data at different geographical levels.

Finally, the openness of the dataset can be an important feature to display on maps of quantification systems. It covers both the accessibility of the data and the transparency of the methodology. Transparency is essential for assessing the scope and quality of a dataset. However, openness may be restricted for many different reasons. Even in the case of public statistics, access to granular data is often restricted for confidentiality reasons, as it might allow re-identification of individuals or entities. Methodological documentation, when available, is seldom disclosed at a very detailed level, partly due to the complexity of the data collection and production processes. Requirements for openness and quality standards have been established for public statistics (e.g. Eurostat protocols). For the private sector, standards have been defined to ensure the reliability of data products such as market surveys (e.g. the ISO 20252 certification). However, companies generally do not disclose their production methods, as they are considered to be commercial assets.

Examples of analysis

These schematic representations not only show, in an efficient way, the nature and scale of the action of the different entities, the circulation of data between them, but also the intersections, dead-ends and densities of information flows. They serve not only as visual syntheses, but also as tools for critical analysis of positions and relationships within the quantification system. They can yield results and ideas such as, for instance, the relative centralisation or dispersion of tourism statistics. Indeed, applied to our national case studies, the mapping showed that tourism as a domain of national official statistics appears rather fragmented. In Italy and France, the main statistical sources on tourism are distributed between the national statistical institute and the national bank (for the foreign demand survey and some economic statistics), and in Switzerland between different sections (mobility, national accounts and tourism) of the national statistical institute. In addition, tourism statistics are often peripheral to broader surveys or production processes: the tourism satellite accounts are fundamentally peripheral, since they are a re-calculation of the national accounts with tourism coefficients; another example is the Swiss survey on national tourism demand, which is collected as a separate, final module of the household budget survey. The mapping also provides a general idea of the relative centrality and/or recent emergence of private data providers. In France, for instance, one of the main mobile phone operators, Orange, has recently become an increasingly important source for destination management organisations and other tourism stakeholders, thanks to a mobile positioning data offer tailored to the tourism sector.

Maps of tourism quantification systems also serve as a basis for subsequent parts of the methodological framework. In particular, ethnomethodological observation should ideally take place in the most central organisations of the quantification system under study (for instance tourism observatories or national statistical offices, depending on the scale of the study area). The actors of the quantification system are also key subjects, although not the only ones, of the discourse and controversy analysis section. Conversely, these other parts of the methodological framework may provide insights that lead to the revision of the map of the tourism quantification system.

Ethnomethodology and ethnostatistics, or the technicalities and tacit politics of statistical work

This second part of the methodological protocol focuses on the practices that make tourism quantification systems work. It is based on the voices and actions of the human actors of these systems. It is grounded in ethnomethodology, that is, the study of how ‘ordinary activities consist of methods to make practical actions […] analyzeable’ (Garfinkel, Citation1967, p. viii), or in other words, the study of the sensemaking practices that guide actions within a given group. Ethnostatistics, as proposed by Gephart (Citation1988), is the specific ethnomethodological approach designed to study the work of statisticians. It is sensitive both to the sociology of the professional group and to the history and dynamics of the rules and conventions by which they operate, in particular how ‘conventions of equivalence’ (Desrosières, Citation1998) and statistical standards are negotiated. In this sense, ethnostatistics shares the central tenets of the sociology of quantification and translates them into an applied method focused on the daily work of statistics-making.

Sensemaking practices and interpretation procedures are arguably a central part of statisticians’ work, as they have to account for the reliability and adequacy of statistical procedures in a highly controlled and formalised way. In this sense, statisticians are likely to be able to explain their own practices in a way that is close to ethnomethodology. However, as statistics-making becomes a ‘mundane everyday practice’ (Gephart, Citation1988, p. 10) for them, part of their work inevitably relies on ‘untold’, non-scientifically codified and taken-for-granted practices and assumptions (Winiecki, Citation2008, p. 186–188), which are the main focus of ethnostatistics. Thus, such an approach is a tool to empirically criticise positivist assumptions that quantitative analysis is intransigently based on objective facts (Bogdan & Ksander, Citation1980, p. 302).

Ethnostatistical research consists of the investigation of three areas (or orders, see ): the production of statistics (quantification and datafication of phenomena), statistics at work (categorisation and analysis of data) and statistics as rhetorics (making data influential in society) (Gephart, Citation1988; Winiecki, Citation2008, p. 204). These three main axes of ethnomethodology were taken into account in the design of the interview guide (cf. documentary collection and actor/ expert interviews section).

Table 2. The three principal steps of the ethnostatistical approach (Gephart, Citation1988).

First-order ethnostatistics is a form of field research, and should be conducted on-site. This means, for the study of tourism quantification systems, in the workplaces of the tourism quantifiers. In this context, it is much easier to ask questions, for example, about the daily work, the hierarchy of positions or the frequency of exchanges with other departments in the institution. As for the second order, the depth of the investigation depends on the skills of the researcher and their access to statistical organisations; it will often have to remain modest unless the researcher is particularly skilled in statistics and able to fully integrate the organisation over a long period of time. Nevertheless, even in a mostly externalist approach, it is possible to ask respondents to give concrete demonstrations of their work (visualising the interface of a database, knowing in detail the functionalities of a technical tool, understanding the importance of a methodological change, for example sampling). The third order of ethnostatistics is dealt with in the following subsection. Finally, depending on the research focus, ethnostatistics can greatly benefit from a historical approach to statistical categories and their application, thus adding a fourth ‘order’ to the ethnostatistical approach (Stoycheva & Favero, Citation2020).

Examples of analysis

The close attention to work practices that ethnostatistics offers is, for instance, particularly efficient for capturing the finer shifts and trends in the making of tourism statistics. In our study case, the various instances of coordination work between public quantification and industry-oriented quantification are particularly fertile ground for such a method. Public-private partnership organisations are tasked with communicating the needs of the industry to public statistical bodies and ensuring interoperability between public official statistics and data produced by private companies. Examples of current projects are the ‘observation platform’ recently launched by Atout France, the French agency for the development and promotion of tourism, which aims to gather as many relevant data sources as possible and make them available to its members; and the reflection process launched by the Swiss Tourism Federation (STV-FST) to create sustainability indicators tailored to tourism businesses. Ethnostatistical observation of such developments, by following the work of these organisations as closely as possible, is an effective way of understanding how tourism quantification is being re-thought and re-made, and in reference to which general purposes of the tourism sector and which challenges.

Statistical discourses or tourism statistics in the public arena

An exploration of the rhetorical power of statistics is particularly important in the study of controversies. In the current controversy on overtourism, for instance, tourism statistics can be used in public discourses either to support pro-growth positions or to defend anti-tourism positions. And tourism statistics may develop in relation to these debates. Quantitative arguments may be mobilised by decision-makers (public and private) as constitutive parts of ‘instruments of public action’ (Lascoumes & Le Galès, Citation2005). Tourism statistics may be criticised in academic publications as well as in the professional tourism or statistical sectors. Discourses of innovation, disruption, or datafication in the quantification sector can also be analysed, as actors of the digital economy strive to expand their markets and traditional statistical producers strive to keep up with new data sources and new methods of data processing. In each of these discourses, numbers are present, but may hold different positions and statuses: evidence, instruments, products, or even the object of debate (see below for details on this categories).

In line with the critical perspective on tourism quantification systems, these discourses and debates are best analysed through qualitative data analysis, or more specifically using the tools of controversy mapping (Venturini & Munk, Citation2021). To conduct such an analysis, a corpus of various discursive materials should be gathered. Ideally, these materials should be representative of the range of positions within the quantification system as well as the range of opinions on the debate under study. Statistical reports such as yearbooks, trend reports, barometers, where key statistics are presented in a standardised form, and statistical analyses where statistics are selected and interpreted, are a first type of valuable material. Although generally presented as factual, neutral and purely descriptive, such publications are inevitably selective and embedded in positionalities. Policy reports and government material are another important type of material, as they express strategies and views, for example on tourism issues and developments. The private sector elaborates statistical discourses in documents such as reports to shareholders, marketing campaigns and press releases. These corporate sources are valuable material for understanding the positions of companies in controversies related to their activities – Airbnb, for instance, has had to engage in significant public relations efforts to defend its business against public criticism and regulatory projects (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2018). Finally, citizen, activists, or NGOs sometimes also engage in their own production and publication of statistics, with various degrees of professionalism in statistical work. Their discourse may be supported by such statistics within pamphlets, websites, media statements, or even demonstrations. The use of statistics within political struggles or debates to illustrate a social issue or to carry the voice of a particular group has been termed ‘statactivism’ (Bruno et al., Citation2014), or ‘data activism’. As a part of the analysis of tourism quantification systems, discourse and controversy analysis must also examine these actors who protest against some aspects of tourism by mobilising existing statistics and sometimes creating new data to strengthen their arguments.

A key dimension of the discourse and controversy analysis is the relative position (both ideological and hierarchical) of actors within the field. Here the analysis can build on the mapping of the tourism quantification system (mapping quantification section). This prior knowledge of tourism actors and the statistics they produce or mobilise makes it possible to situate their discourses, but also to contrast their formal, institutional, public discourse with everyday practices and internalised discourses, drawing on interviews (see documentary collection) as well as ethnostatistical observation (see ethnomethodology section). Discourse analysis is understood here in a ‘classical’ or Foucauldian way; as the contrast between these multiple versions of a discourse or position, especially between the ‘official/controlled’ version and the ‘embodied or internalised’ version (Foucault, Citation2009).

Examples of analysis

Another key aspect of the discourse analysis method when applied to tourism quantification systems is the characterisation of the role of statistics or figures in the discourses under study. We suggest that there are at least four roles for statistics or figures that are relevant in the discourses within and about tourism quantification systems: as evidence, instrument, product, or object of debate.

In the debate about overtourism, figures are often used as evidence: the increased cost of living, housing shortage, traffic congestion, can all be related or attributed – convincingly or not – to the presence of ‘too many’ tourists in a given space–time. This was the case when, in 2017, the city of Paris began to communicate in various media about the ‘20 000 to 30 000′ apartments ‘lost’ to short-term rental platforms. As mentioned above, some groups categorised as ‘stactivists’ or ‘datactivists’ produce data or figures on tourism in order to warn of some of its detrimental effects. The most prominent example of this is the ‘scraping’ of data from Airbnb carried out by Inside Airbnb and similar initiatives (Cox & Slee, Citation2016; Piganiol & Aulnay, Citation2021).

Figures on tourism become instruments when they are integrated into decision-making processes, whether public or private, for example to guide investments, policies or legislation. The city of Lucerne in Switzerland, for instance, has developed a policy plan for tourism called ‘Vision Tourismus 2030′Footnote1, which sets out several targets relying on quantitative indicators. Among such quantitative goals, the plan demands an ‘increase of the average length of stay’ of tourists, or the ‘reduction of the share of day-tripper groups (bus tours)’ in the visiting population.

Data and statistics can also be products when they are sold by private companies. As such, they are promoted and supported by marketing discourses; the talk of disruption and innovation around big data should always be analysed with this fact in mind. A recent example is the launch of a ‘Tourism Innovation Hub’ by Mastercard in Spain, framed by the company as a contribution to the recovery of the tourism industry after the Covid crisis: ‘Mastercard data shows that there are opportunities for a robust recovery in the relatively near future. Many consumers are looking at how to spend their share of the extra US$5 trillion saved since the onset of COVID-19Footnote2’. The discourses of the consumers of these products (in tourism, often public entities or destination management organisations) on the benefits, reliability and opacity/transparency of the data are also an important resource for the analysis of the evolving politics of quantification.

When critical, these discourses address the fourth discursive role of numbers and statistics, that of the object of debate. Then, as when data activists denounce partial or skewed representations of statistics (Cox & Slee, Citation2016), as when academics highlight the gaps and biases in official tourism statistics, the central object of the debate becomes the production and representation of statistics themselves.

Identifying who counts, but also who mobilises the numbers, what kind of numbers and in what debates, is therefore essential to understand in detail the impact of the process of quantification of tourism on the tourism sector itself. In other words, it is important to study the active and retroactive effects of quantification on what is quantified (Desrosières, Citation2014, chap. 1). The multi-perspective approach of identifying (mapping) the numbers, their producers, users and sources; observing (ethnomethodologically) the processes of production, diffusion and use; and investigating the main actors (interviewing and analysing their discourse) about their practices with tourism numbers and their position in the tourism debates, allows a relevant and critical analysis of the tourism quantification process.

Perspectives and conclusion

With this paper we offer an innovative methodological framework for mapping and analysing tourism quantification systems. We bring to tourism research a new body of theory (the sociology of quantification) and an unprecedented level of critical scrutiny of statistics and quantification. In doing so, we open up a new area of research, a new window on some of the central issues of tourism governance. We argue that quantitative knowledge-making is instrumental to the structuring of tourism and the decision-making of many key stakeholders, and that statistical categories and statistics providers reflect both the solidity of organisational arrangements and the changing interests and issues in the field of tourism. To fully grasp this, we argue that it is important not only to map networks of knowledge production and circulation, but also to investigate everyday work practices of statistics-making and all kinds of discourses that mobilise tourism statistics. We outline the main principles and steps of a methodological framework that addresses these three dimensions: first, a mapping of tourism quantification systems, based mainly on documentary collection about organisations and datasets, and on interviews with key actors; second, an ethnomethodological approach applied to statistical work, termed ethnostatistics, that relies on (participant) observation of the production of statistics; and third, a qualitative analysis of discourses ‘with statistics’, borrowing tools from controversy mapping.

We present some of the insights, drawn from our research, that this method can yield, such as how it reveals the structural power relations of tourism quantification systems, and shifts in these power relations in the context of the emergence of new actors in the quantification sector, or in relation to socio-political issues such as overtourism. Among the other global challenges currently facing tourism, at least two would greatly benefit from investigation using this method, as they directly question the way tourism is quantified: (1) the imperatives of sustainability, which call for the abandonment of apparatuses and discourses that rely on growth as a cardinal value, and for the invention of suitable indicators to account for the environmental costs of tourism; and (2) the continuous expansion of digital technologies, which offers many new flows of quantitative information, adding a third main source, traces, to traditional statistical knowledge relying on surveys and on registries (Boullier, Citation2015; Desrosières, Citation2005); but which also imposes a new regime of knowledge through the ideal of exhaustive, big data and through the primacy of correlation over explanation.

This methodological proposition, as well as the theoretical perspective in which it is rooted, complements studies on the role of knowledge in the tourism sector. Indeed, the critical study of quantification confirms that knowledge is a key element in the governance of tourism (Moscardo, Citation2011), but it also outlines the specific, structuring role of quantitative indicators, as tools for standardisation and as central instruments for policy. Our contribution also emphasises the need to pay attention to power dynamics in the circulation of knowledge. In doing so, it complements studies on innovation and governance (Raisi et al., Citation2020) in tourism with a more critical lens that goes beyond a conception of the circulation of knowledge as beneficial to all actors involved, and suggests that knowledge resources are unevenly controlled and can reproduce power structures (Dredge & Gyimóthy, Citation2015). The methodological framework we propose is also designed to provide further, more detailed arguments to previous lines of inquiry into the flaws, biases and gaps of tourism statistics. The critical study of quantification demonstrates that tourism statistics are constrained and modelled not just by technical matters, but also by the interests of the stakeholders who control the quantification procedures. In this regard, we concur for instance with the analyses of Pratt and Tolkach (Citation2018) on the skewed representation of international tourism flows; but we would further analyse how this state of affairs is inherently linked to the status and functioning of the UNWTO: the statistical authority of this agency is limited to recommending global standards, and does not go as far as imposing statistical methods to member states. The critical study of quantification can also help establish the pivotal role of the traditional accommodation sector in the development of tourism statistics, and thus help hypothesise that a significant part of tourism remains ‘unobserved’ (De Cantis et al., Citation2015; Volo & Giambalvo, Citation2008) because it lies outside of the economic interests of that sector. Insights gained from the application of this methodological protocol are valuable for the tourism industry and to tourism policy makers. Indeed, these insights can help tourism stakeholders to reflect on their own position within the quantification systems, to see quantification processes as arenas of negotiation between different interests in the tourism sector, and to defend their own interests in the currents developments of the quantification of tourism. In particular, critical reflection on the quantification apparatuses is needed today to challenge the dominant narrative of ‘the more data, the better’ and to question the adequacy of data for specific needs. Critical studies of quantification systems could also allow tourism stakeholders to look more closely at the ownership of data and demand more transparency in the methods of data production, especially in the era of big data and the platformisation of tourism services. Although our methodological proposition focuses on statistics and other quantitative data, the basic principles and methods can easily be adapted to other types of knowledge and to other areas of tourism governance where knowledge is a key resource – arguably all areas of tourism governance. For instance, it would be of great hermeneutic value, both for academia and for the tourism industry, to map and analyse systems of financing and investments in tourism, or systems of land and urban planning in tourism destinations. Indeed, it is only through a critical understanding of the structures and practices of knowledge that we can fully comprehend how tourism governance systems are equipped to face the contemporary shocks and shifts in the tourism phenomenon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Valérian Geffroy

Valérian Geffroy is a Post-doctoral researcher. A geographer, his research interests include the quantification of tourism, mobility and outdoor sport tourism.

Victor Anduze Rivero

Victor Anduze Rivero is a Doctoral candidate. Trained in geography and sociology, his interests include the quantification of tourism, overtourism and other socio-political issues in urban space.

Davide Ceccato

Davide Ceccato is a Doctoral candidate. Trained in history, philosophy and international relations, his interests include the quantification of tourism and digital and surveillance studies, in Venice in particular.

Notes

1 Grossen Stadtrat von Luzern, Vision Tourismus Luzern 2030, report n° B+A 41/2021.

2 ‘Mastercard Launches Tourism Innovation Hub in Spain’, 20th January 2022, www.businesswire.com/news/home/20220120005584

References

- Adamiak, C., & Szyda, B. (2022). Combining conventional statistics and big data to map global tourism destinations before COVID-19. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1848–1871. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211051418

- Alonso, W., & Starr, P. (1987). The politics of numbers. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Antolini, F., & Grassini, L. (2020). Issues in tourism statistics: A critical review. Social Indicators Research, 150(3), 1021–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02361-4

- Bardet, F., Coulondre, A., & Shimbo, L. (2020). Financial natives: Real estate developers at work. Competition & Change, 24(3-4), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529420920234

- Bar-On, R. R. (1991). Improving the reliability of international tourism statistics. The Tourist Review, 46(2), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb058066

- Batista e Silva, F., Marín Herrera, M. A., Rosina, K., Ribeiro Barranco, R., Freire, S., & Schiavina, M. (2018). Analysing spatiotemporal patterns of tourism in Europe at high-resolution with conventional and big data sources. Tourism Management, 68, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.020

- Bogdan, R., & Ksander, M. (1980). Policy data as a social process: A qualitative approach to quantitative data. Human Organization, 39(4), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.39.4.x42432981487k54q

- Boullier, D. (2015). The Social Sciences and the Traces of Big Data: Society, Opinion or Vibrations?. Revue française de science politique, 65(5–6), 805–828. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfsp.655.0805

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

- Bruno, I., Didier, E., & Prévieux, J. (2014). Statactivisme: Comment lutter avec des nombres [Statactivism: How to Fight with Numbers]. Zones.

- Bruno, I., Jany-Catrice, F., & Touchelay, B. (Eds.) (2016). The social sciences of quantification: From politics of large numbers to target-driven policies (Vol. 13). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44000-2

- Cooper, C. (2015). Managing tourism knowledge. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1006418

- Cox, M., & Slee, T. (2016, février 10). How Airbnb’s data hid the facts in New York City. Inside Airbnb. http://insideairbnb.com/research/how-airbnb-hid-the-facts-in-nyc/.

- Cussó, R. (2020). Building a global representation of trade through international quantification: The league of nations’ unification of methods in economic statistics. The International History Review, 42(4), 714–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2019.1619611

- De Cantis, S., Parroco, A. M., Ferrante, M., & Vaccina, F. (2015). Unobserved tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.10.002

- Desrosières, A. (1998). The politics of large numbers: A history of statistical reasoning. Harvard University Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=XUOCAAAAIAAJ

- Desrosières, A. (2005). Décrire l’État ou explorer la société: Les deux sources de la statistique publique [Describing the State or Exploring Society: The Two Sources of Official Statistics]. Geneses, 58(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.3917/gen.058.0004

- Desrosières, A. (2008). Pour une sociologie historique de la quantification: L’Argument statistique I [For a historical sociology of quantification The Statistical Argument I]. Presses des Mines. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pressesmines.901

- Desrosières, A. (2014). Prouver et gouverner. Une analyse politique des statistiques publiques [Prove and govern. A Political Analysis of Public Statistics]. La Découverte. https://www.cairn.info/prouver-et-gouverner–9782707178954.htm

- Dredge, D. (2015). Tourism-planning network knowledge dynamics. In M. T. McLeod & R. Vaughan (Eds.), Knowledge networks and tourism (pp. 9–27). Routledge.

- Dredge, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2015). The collaborative economy and tourism: Critical perspectives, questionable claims and silenced voices. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1086076

- Espeland, W. N., & Sauder, M. (2007). Rankings and reactivity: How public measures recreate social worlds. American Journal of Sociology, 113(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/517897

- Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (1998). Commensuration as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.313

- Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (2008). A sociology of quantification. European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 49(3), 401–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975609000150

- Ferreri, M., & Sanyal, R. (2018). Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London. Urban Studies, 55(15), 3353–3368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017751982

- Font, X., Torres-Delgado, A., Crabolu, G., Palomo Martinez, J., Kantenbacher, J., & Miller, G. (2023). The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European tourism indicator system. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1608–1630. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1910281

- Foucault, M. (2009). L’ordre du discours: Leçon inaugurale au Collège de France prononcée le 2 dećembre 1970 [The Order of the Discourse: Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France on December 2, 1970]. Gallimard.

- Franklin, A. (2004). Tourism as an ordering: Towards a new ontology of tourism. Tourist Studies, 4(3), 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604057328

- Frechtling, D. C. (2010). The tourism satellite account: A primer. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.08.003

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

- Gephart, R. P. (1988). Ethnostatistics: Qualitative foundations for quantitative research. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984133

- Guizzardi, A., & Bernini, C. (2012). Measuring underreporting in accommodation statistics: Evidence from Italy. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(6), 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.667071

- Hannigan, K. (1994). Developing European community tourism statistics. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(2), 415–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90062-0

- Islam, M. W., Ruhanen, L., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). Exploring social learning as a contributor to tourism destination governance. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(3), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2017.1421294

- Jóhannesson, G. T. (2005). Tourism translations: Actor–network theory and tourism research. Tourist Studies, 5(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797605066924

- Knorr-Cetina, K. D. (1981). The manufacture of knowledge: An essay on the constructivist and contextual nature of science. Pergamon Press.

- Lascoumes, P., & Le Galès, P. (2005). Introduction: Public action seized by its instruments. In P. Lascoumes, & P. Le Galès (Eds.), Gouverner par les instruments [Governing by instruments] (pp. 11–44). Presses de Sciences Po. https://doi.org/10.3917/scpo.lasco.2005.01.0011

- Mashkov, R., & Shoval, N. (2023). Using high-resolution GPS data to create a tourism intensity-density index. Tourism Geographies, 25(6), 1657–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2023.2276910

- Moscardo, G. M. (2011). The role of knowledge in good governance for tourism. In E. Laws, H. Richins, & J. F. Agrusa (Eds.), Tourist destination governance: Practice, theory and issues. (pp. 67–80) CABI.

- Nyns, S., & Schmitz, S. (2022). Using mobile data to evaluate unobserved tourist overnight stays. Tourism Management, 89, 104453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104453

- Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2014). What happens when evaluation goes online? Exploring apparatuses of valuation in the travel sector. Organization Science, 25(3), 868–891. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0877

- Piganiol, V., & Aulnay, V. (2021). Carte à la une. La France d’AirBnB [Featured map. AirBnB France]. Géoconfluences. http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/a-la-une/carte-a-la-une/france-airbnb

- Porter, T. (1995). Trust in numbers: The pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton University Press.

- Pratt, S., & Tolkach, D. (2018). The politics of tourism statistics. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2181

- Raisi, H., Baggio, R., Barratt-Pugh, L., & Willson, G. (2020). A network perspective of knowledge transfer in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102817

- Randeraad, N. (2011). The International Statistical Congress (1853—1876): Knowledge transfers and their limits. European History Quarterly, 41(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691410385759

- Saluveer, E., Raun, J., Tiru, M., Altin, L., Kroon, J., Snitsarenko, T., Aasa, A., & Silm, S. (2020). Methodological framework for producing national tourism statistics from mobile positioning data. Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102895

- Smeral, E. (2006). Tourism satellite accounts: A critical assessment. Journal of Travel Research, 45(1), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506288887

- Smith, G. J. (2020). The politics of algorithmic governance in the black box city. Big Data & Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720933989

- Stock, M., Coëffé, V., & Violier, P. (2020). Les enjeux contemporains du tourisme: Une approche géographique [The contemporary challenges of tourism. A geographical approach] (2ème édition). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Stoycheva, S., & Favero, G. (2020). Research methodology for ethnostatistics in organization studies: Towards a historical ethnostatistics. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 9(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-03-2019-0016

- Terrier, C. (2006). Tourist flows and influxes: measuring instruments, the geomathematics of flows. Flux, 3(3), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.3917/flux.065.0047

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. (1956). International Tourist Statistics (E/CN.3/221). https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/doc56/1956-221-TouristStats.pdf.

- van der Duim, R., Ren, C., & Thór Jóhannesson, G. (2013). Ordering, materiality, and multiplicity: Enacting actor–network theory in tourism. Tourist Studies, 13(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797613476397

- Vanhoof, M., Hendrickx, L., Puussaar, A., Verstraeten, G., Ploetz, T., & Smoreda, Z. (2017). Exploring the use of mobile phone data for domestic tourism trip analysis. Netcom. Réseaux, Communication et Territoires, 31(3&4), 335–372. https://doi.org/10.4000/netcom.2742

- Van Truong, N., Shimizu, T., Kurihara, T., & Choi, S. (2022). Accommodation statistics: The current issues and an innovation. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(11), 1731–1747. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1978951

- Venturini, T., & Munk, A. K. (2021). Controversy mapping: A field guide. Polity Press.

- Volo, S., & Giambalvo, O. (2008). Tourism statistics: Methodological imperatives and difficulties: The case of residential tourism in island communities. Current Issues in Tourism, 11(4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802140398

- Weaver, A. (2021). Tourism, big data, and a crisis of analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103158

- Winiecki, D. J. (2008). An ethnostatistical analysis of performance measurement. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 3-4(20), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.20010

- Wöber, K. W. (2000). Standardizing city tourism statistics. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00054-7