Abstract

Policy changes have resulted in a shift of focus from greenfield to brownfield development, leading to densification and transformation of the urban fabric. Planning decisions are necessary steps towards implementation. However, such decisions do not necessarily mean that development projects materialise. From there, public authorities can choose an active role, as in greenfield urban expansion, or a passive role leaving the implementation of the plan to private developers.

Despite obvious shortcomings, zoning is still the common statutory instrument of land-use planning. Traditional flat, exclusionary zoning has been under attack and is claimed to be inflexible and narrowly focused. However, adaptability has been a principal feature of zoning, evolving as a system from rigid zoning to case-by-case approvals. Consequently, modern zoning decisions are often made in direct negotiations with developers.

Still, it is claimed that the statutory planning system leaves too little room for negotiations. Hence, informal strategic land-use planning has been adapted as an additional framework for negotiations. Norwegian planning has followed this international trend, introducing flexible zoning instruments and negotiations between planning authorities and developers and local public authorities rely on private property development as a means of urban development. The purpose of this article is to examine how municipal authorities and developers conduct negotiations on detailed zoning plans for the implementation of brownfield transformation projects in the existing urban fabric. The study is based on four cases in Oslo, where municipal authorities and developers have negotiated the content of the zoning plans for the implementation of primarily residential development. The findings indicate that statutory and legally binding planning could work just as well as informal planning as the basis for integrative negotiations if statutory master plans are made more generic and allow for a necessary degree of flexibility. However, it seems that the parties’ ability to trust each other is even more fundamental for both the opportunity to establish integrative negotiations and for the outcome of the negotiations.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to analyse and discusses empirical findings related to Norwegian statutory land-use planning and the room for manoeuvre that this system provides for negotiations between municipal planning authorities and private property developers on the content and design of Detailed Zoning plans. Both the content of negotiations and the subsequent outcome are affected by how the parties enable the building of trust in each other. In this sense, the system design influences the design of the built environment.

As will be explained later in the article, Norwegian land-use planning consists of a development-led detail zoning practice within a formally plan-led system, not unlike equivalent international systems (see, for example, Muñoz Gielen, Tasan-Kok 2010; Buitelaar et al. 2011; Hartmann, Spit Citation2014; Valtonen et al. Citation2017). This framework is a necessary starting point for understanding how legal structures affect the scope of action of negotiations. Formally, Norwegian statutory land-use planning does not allow for negotiations between the authorities and private property developers. Nevertheless, there is reasonably broad agreement that such negotiations are widespread. The article, thus, contributes to the international debate on the relationship between regulatory and discretionary planning systems, particularly on how development-led planning practices emerge from distinct statutory framings.

Systems that are initially designed as planled and regulatory might provide for distinct discretionary room for manoeuvre. Purposeful integrative negotiations are, however, dependent on a certain degree of trust between the parties participating in the negotiations. Depending on the design of the planning system, as in Norwegian statutory land-use planning, zoning as a central structuring element will influence the negotiations in the direction of more limited distributive negotiations. What mainly distinguishes the Norwegian planning system from Nordic or continental European systems that are assumed to be relatively similar is that (1) the planning authority has a wide discretion to choose between several different types of legally binding land-use plans for most purposes, (2) that in principle, everyone has the right to initiate a Detailed Zoning plan, without prior planning permission, and (3) that the municipality has a duty to process such initiatives without unnecessary delay (Røsnes Citation2005).

These deviations affect the relationship between public authorities and developers. When developers are allowed to initiate a Detailed Zoning plan, this also gives them an additional opportunity to influence the regulatory framework for plan implementation (Kalbro, Røsnes Citation2013). The tendency, thus, has been that Norwegian municipalities refrain from actively pursuing plan implementation and urban development through zoning (Røsnes Citation2005). Rather, they pursue higher-level strategic planning (Hanssen, Aarsæther Citation2018), including political strategies and planning instruments that are not authorised in the Planning and Building Act. Consequently, the municipalities also refrain from active plan implementation. This has some important consequences, most notably that implementation most often is dependent on private developers finding the plan financially viable. New planning practices emerge as a response to the need to coordinate and negotiate public and private interests in land-use planning (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2011).

Historically, urban land development has been associated with concentric development of greenfield land for urban use. A growing need for housing was met through the development of new residential areas on the outskirts of and outside existing urban areas. Harald Hals, the influential former director of land-use planning in Oslo, Norway for three decades in the first half of the 20th century, distinguished between the older inner-city transformation, where “[existing] property boundaries, acquired rights and possessions, … must be respected” (Hals Citation1929: 84), and the newer, outer urban expansion, “which should provide a secure guideline, show the large groups of diverse buildings, reserve free land, park area, etc.” (Hals Citation1929: 86f). What Hals named outer urban expansion is commonly understood as zoning (Holsen Citation2020), a planning instrument which, in principle, does not take into account property boundaries or rights in real estate. However, from the mid-1990s, densification and transformation of the urban fabric has been the stated national Norwegian policy for urban development. The policy change has resulted in a shift of focus form greenfield to brownfield development, in which a planning decision is a necessary step towards implementation.

Despite the recognition that zoning is not necessarily a well-suited instrument for managing densification and the observed emergence of negotiations between public and private actors in urban development, zoning is still the common statutory instrument of land-use planning. For this reason, traditional, flat, exclusionary zoning has been under attack (Kayden Citation1992; Hoyt 2013), and has been claimed to be inflexible, having a narrow focus and a blunt approach to land use (Baker et al. Citation2006). As a system for land-use planning, this approach can be described as passive, aimed at controlling land use (Albrechts Citation2006). However, adaptability has been a principal feature of zoning, evolving as a system from rigid zoning to case-by-case approvals (Green Citation2004; Selmi Citation2011). Consequently, modern zoning decisions are often made in direct negotiations with developers (Frank Citation2009).

Through amendments, Norwegian statutory planning has followed this international trend, introducing flexible zoning instruments as conditional zoning, performance-based zoning, form-based zoning, etc., which, in turn, widens the room for discretion and negotiations between planning authorities and developers. However, it is claimed that the statutory planning system still leaves too little room for negotiations. Consequently, various informal strategic planning tools are developed outside the planning system and used alongside statutory plans to guide development (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015). The municipality of Oslo, Norway, has adopted informal strategic land-use planning as a framework for negotiations between the municipal planning authorities and private developers (de Vibe Citation2015), believing that such informal plans could guide the negotiations, establish trust between the parties and create the stable conditions necessary for interest-based negotiations.

The purpose of this article is to examine how the municipality of Oslo and property developers conduct negotiations on Detailed Zoning plans for the implementation of brownfield transformation projects in the existing urban fabric. In part, it is examined whether and, if so, how the planning authorities’ extensive opportunities to choose between different types of planning instruments and land-use plans, including both legally binding statutory plans and strategic tools outside the domain of the Planning and Building Act, affect the negotiations. In part, it is examined whether and, if so, how the planning authorities’ choices and the property developers’ patterns of action affect the trust between the parties in the negotiations on Detailed Zoning plans and subsequent results of the negotiations. The article is primarily based on a study (Kind, Vedrana 2017) of four cases in Oslo, where municipal authorities and developers have negotiated the content of the zoning plans for the implementation of primarily residential development.

Before these case studies are presented and discussed, however, it is necessary to establish an understanding of the current Norwegian land-use planning system. Today’s legislation is built on and is an amendment to previous legislation. This affects the institutional understanding of the current legislation and, thus, also the parties’ understanding of their own and the others’ positions on urban development and, through this, also the actual room for undertaking negotiations.

Land-use planning in Norway

The Norwegian planning system

An active attitude by public authorities towards plan implementation is usually associated with plan-led systems. The Norwegian land-use planning system should, in theory, and based on the legally binding nature of both the Land-use Element of the Municipal Master plan and the Detailed Zoning plan, be regarded as plan-led. This certainly was the aim when implementing the current Planning and Building Act in 2008. The planning system was developed with the aim of strengthening the Municipal Master plan and the Land-use Element of the Master plan’s function as a comprehensive and coordinating instrument for private property development (Proposition to the Storting 2008). For more than 50 years, Norwegian legislative authorities have regarded the comprehensive municipal master planning as the important hierarchical level.

However, the policy changes from greenfield urban expansion to brownfield transformation, the right of external stakeholders to initiate Detailed Zoning plans and the municipal emphasis on strategic planning all affect the relationship between public authorities and developers, leaving active implementation to the private market. Today, urban transformation in Norway rarely take place unless real estate developers consider brownfield areas as profitable. Seen this way, it is not an antagonistic relationship between Norwegian public planning and real estate development, but rather an acceptance of symbiotic and necessary cooperation. Private real estate development is the major means for the implementation of zoning decisions and private developers initiate the lion’s share of Detailed Zoning plans.

The current Norwegian planning legislation is based on three areas of action: comprehensive planning, land-use planning and plan implementation (NOU 2003). The individual parts of this tripartite domain have been emphasised in varying degrees over the past 50 years, both in legislation and in planning practice. The 1965 planning legislation emphasised land-use planning understood as zoning on the municipal level, often referred to as the General plan. The aim of this planning was overall management of urbanisation, understood as urbs, and particularly, to control and locate the expansion of the built environment into the green fields. Unlike later generations of higher-level municipal land-use planning, this first generation was not legally binding.

The next generation of Norwegian planning legislation was passed in 1985 and introduced quite ambitious comprehensive planning and the Municipal Master plan as the new overall planning instrument. The former General plan was retained as an element in the Master plan, now referred to as the Land-use Element of the Municipal Master plan. The planning system was built on the assumption that public planning authorities should have the leading role in initiation and preparation of plans at all levels of planning.

Quite soon after the implementation of the 1985 planning legislation, the neoliberal turn, together with densification as a governing national land-use policy, challenged this assumption. The attention of planning practice was soon directed towards plan implementation and privately initiated Detailed Zoning plans. A large number of development-led zoning plans were adopted with completely different land-use objectives to those in the Municipal Master plans.

In the current Planning and Building Act of 2008, municipal Master plans still have comprehensive planning goals. The plan still contains the legally binding Land-use Element of the Municipal Master plan and introduces two types of local zoning plans: the Area Zoning plan and the Detailed Zoning plan. The role of private developers in the implementation of plans is acknowledged. The Detailed Zoning plan should be understood as a plan for implementation of development projects (NOU 2003), i.e. the plan to be used by private developers as a part of the process of granting a permit for developing the building plot. For this reason, the current Planning and Building Act has been designed with quite comprehensive ambitions for compliance between the hierarchical levels of the land-use planning system (Kalbro, Røsnes Citation2013). Private proposals for Detailed Zoning plans should contextually comply with the main features and limitations in the Land-use Element of the Municipal Master plan and the Area Zoning plan (if this exists). If the detailed plan implies deviations beyond minor necessary clarifications, the higher-level land-use plans must be changed before or at the same time as the decision of the Detailed Zoning plan.

As stated in the Bill on the current Planning and Building Act, the interaction between public authorities and private stakeholders is more important when planning is initiated by private developers and has become negotiation-oriented (Proposition to the Storting 2008). For this reason, the Bill emphasised that statutory land-use planning should be procedurally flexible, allowing the municipality wide discretion to choose the level of detail and statutory instruments to be used, and simultaneously be able to zone more rigidly and in detail. Evaluations have shown that this opportunity for detailed and rigid zoning has been implemented by municipalities for higher-level land-use planning to a considerable extent (Børrud Citation2018). From the planning authorities’ point of view, Norwegian statutory land-use planning appears to be a flexible system. From the developers’ point of view, the system can, to a far greater extent, be described as procedurally arbitrary and substantially rigid.

Private developers preparing proposals for Detailed Zoning plans are required to submit the initiative before the planning authorities in a compulsory and formal start-up meeting. Here, the parties are expected to discuss the layout and scope of the planning initiative, clarifying the overall premise for the drafting of a zoning plan, requirements for further documentation and procedural clarifications, etc. ( NOU 2003). National planning authorities consistently denote the meeting as a dialogue aimed at establishing a common understanding of the further planning work (KMD 2018). However, it is commonly understood de facto as an opportunity for bilateral negotiations between developers and the municipality (Holsen 2018). For this reason, it could be analysed through negotiation theory.

At the end of this process of dialogue/negotiations, the developer probably will submit his proposal for a Detailed Zoning plan, which the municipality is obliged to consider whether to submit for public inspection. The municipal planning authority has the right simultaneously to submit their alternative proposal for zoning of the area. When public inspection is completed, the negotiations continue with the intention of incorporating necessary changes. The final draft of a Detailed Zoning plan is then submitted to the municipal council for approval, optionally still with alternatives.

In summary, the Norwegian planning system can be described as a deliberate attempt at rigid, imperative zoning. Although privately initiated plans are accepted and private property development is seen as a major instrument for plan implementation, the intention is to curb private initiatives to conform to the Municipal Master plan. However, the discretionary room for negotiations is relatively prominent. This is in line with the findings of Muñoz Gielen and Tasan-Kok (2010) on Western European countries that theoretically have plan-led planning systems but show characteristics more similar to development-led planning. Buitelaar and Sorel (Citation2010), commenting on the current Dutch planning system, describe planning systems in general as a trade-off between flexibility and legal certainty. As they conclude on planning practice in the Netherlands, even Norwegian planning practice seems to be more flexible than the general assumptions of the Norwegian planning system. An important question, however, is how the previously mentioned discrepancies between the Norwegian planning system and comparable international systems affect the negotiating space and negotiated land-use plans.

The Oslo model for non-statutory strategic land-use planning

Although the Norwegian planning system is generally rather flexible, the municipality of Oslo has found the system of legally binding land-use plans on two hierarchical levels too inflexible, primarily because large-scale overall statutory planning processes are procedurally slow and unsuitable for controlling a reality where the planning authorities are processing more than 100 Detailed Zoning plans throughout the whole city at any time (de Vibe Citation2015). This requires flexible, coordinated, strategic, higher-level land-use plans. The difficulties of statutory comprehensive planning, described by Mäntysalo et al. (Citation2015: 361) as “overblown survey and assessment demands, as well as time-consuming participation procedures and public checks”, limit its capacity to serve as an instrument of strategic planning.

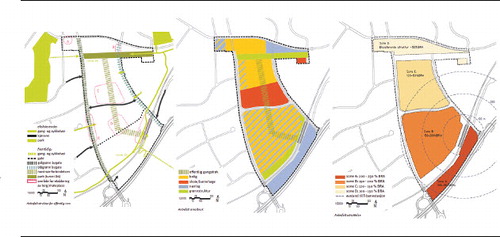

To address this situation, the “Oslo model” has been developed. Unlike statutory zoning, this model rests on indicative planning, named the “Guiding Principle Plan for Public Spaces” (In Norwegian “Veiledende Prinsipplan for Offentlige Rom”, abbreviated as VPOR). Although these plans are not statutory, they are adopted by the City Council. The purpose of VPOR is to improve the authorities’ relative strength in negotiations with developers (de Vibe Citation2015). In VPOR, the main issues relate to the management of public infrastructure, including the location of streets, squares and parks. Additionally, VPOR indicate principles for the design of the urban green structure, the approximate location and need for schools, kindergartens and other social infrastructure. A third area governed by VPOR is densities, heights and categories of land use, more generally formulated than how it is usually done in statutory plans (see for an example of VPOR maps). The VPOR model has later been further developed into what the Oslo Municipality has called “Urban planning measures”. Contrasting VPOR, which is intended to be a non-statutory type of strategic plan in itself, the “Urban planning measures” approach is intended as an early, indicative communication of a desired land-use pattern for a transformation district, intended to end with a statutory zoning plan.

Fig. 1: Maps/plans from the VPOR for Vollebekk, Oslo. Left map shows main street network with squares and parks, middle map shows designated land use (yellow: residential, red: school/kindergarten, blue: business), right map shows accepted densities. The VPOR also consists of written descriptions that further elaborate on the criteria for development of Detailed Zoning plans.

Negotiations

The starting point for negotiations is opposing interests, rather than conflict, as the parties are interdependent and have a common interest in finding solutions. Negotiations take place when the parties believe that a negotiated deal is a better solution than otherwise (Rognes Citation2015). Because of the interdependence, trust is an integral part of negotiations (Lewicki, Polin Citation2013). Furthermore, there is a relationship between trust and risk. Having something invested in the situation is a prerequisite to trust (Mayer et al. Citation1995).

In negotiation theory, a distinction is often made between distributive and integrative negotiation (McCarty, Hay 2015). Distributive negotiations are games of win and lose, usually regarding one dimension, such as price. What one actor is able to earn through the process, the other loses. Integrative negotiations, on the other hand, are about win-win resolutions over multiple dimensions that may have different values between the parties. As stated by Fisher et al. (Citation1991), you should not bargain over position but focus on interests. Positions tend to obscure what you really want to achieve. By focusing on interests, there is the possibility to broaden the basis for solutions and thereby change the prerequisites so that both parties achieve solutions they think are better for themselves. For this reason, integrative negotiations tend to be more complex and demanding than distributive (Rognes Citation2015), and, above all, rely on trust between the parties involved (Butler Citation1999). Trust seems to inhibit distributive behaviour and facilitate integrative behaviour, leading to the sharing of information, which subsequently promotes the joint outcome of negotiations (Kong et al. Citation2014). However, integrative behaviour is inherently risky, as the other party could exploit it. Hence, if you do not trust the other party in a negotiation, the risk associated with information sharing tends to lead to your own withdrawal back to distributive bargaining.

The initial problem of legally binding zoning plans is that they tend to focus on positions. Land-use objectives, maximum densities, building heights, building lines, etc. are fixed positions. The interests behind the positions are to be discussed (negotiated) in the plan-making process before the planning decision. As described above, Norwegian statutory planning consists of legally binding zoning at two hierarchical levels where a Detailed Zoning plan must comply with the overall Municipal Master plan. Consequently, the statutory system describes a situation where, to gain influence, real estate developers ought to take part in the ordinary participatory processes, which most likely took place several years prior to the land acquisition. This is an unlikely situation. Most likely, the private property developer will first get involved when initiating and developing the Detailed Zoning plan, which must comply with regulations in the higher-level zoning plan. This easily leads to positional bargaining and distributive negotiations between developer and planning authorities about the more detailed elaboration of the higher-level plan. To some extent, this problem might be solved by changing the higher-level plans to have a more generic character, for example, as is the case with the Oslo model (VPOR). The belief is that strategic, indicative land-use planning can help with focusing on interests and facilitate integrative negotiations over interest rather than positional bargaining.

Several stages of trust can be identified in negotiations (Lewicki, Polin Citation2013). First, there is deterrence-based trust, relying on the belief that the other party will follow agreed promises due to negative consequences for not complying with them. The next stage is calculus-based trust, which is to trust the other party because you want to achieve positive consequences. A further stage is knowledge-based trust, understood as trust residing in the ability to know and understand the other party accurately enough to predict what it wants and how it will behave. Finally, there is identification-based trust, characterised by an identification with the other and an effort to help the other realise their goals. According to Lewicki and Polin, this latter type of trust “is often seen in integrative negotiations, and particularly between parties who know each other very well, where the parties not only have individual goals to achieve but also define and work to accomplish joint goals” (p. 164). In any case, trust is not the same as trustworthiness. Your propensity to trust depends on judgements of three attributes of the other party: characteristics of their ability, benevolence and integrity to be trusted (Mayer et al. Citation1995). For this reason, negotiations are not only dependent upon the existence of necessary structural conditions, as have been developed in the Oslo model. Additionally, the parties who negotiate must possess the necessary skills to become good negotiators, including the ability to consider the trustworthiness of the other party and accept the risk involved in the trust game.

In addition to trust, there are three prerequisites for the success of integrative negotiations. Firstly, the problem must have more than one dimension. Secondly, the parties must be motivated to invest the time needed to carry out complex negotiations. Lastly, one must have the competence to conduct such negotiations (Rognes Citation2015). While distributive negotiations are of a competitive nature, integrative negotiations are not. They require cooperation (McCarty, Hay 2015) and the ability to find possible mutual gain (Fisher et al. Citation1991). As an example, developers could prefer risk reduction, trading this against higher quality of public infrastructure. On the other hand, public authorities could accept alternative concepts for the building pattern or densities, if developers are willing to incorporate new public facilities into the development.

However, not all negotiations end with an agreement. You negotiate with the desire to find a better solution than otherwise possible. Hence, you should know what is a better solution. This is often referred to as BATNA (Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement) (Fisher et al. Citation1991). For private developers, the ultimate test would be the bottom line of the budget, although, for some developers, red numbers in one project might be acceptable if this leads to later gains. For planning authorities, the BATNA may be to postpone the urban transformation in anticipation that changed market conditions may lead to the developer accepting the desired qualities at a later date.

Four cases and two developers in OsloFootnote1

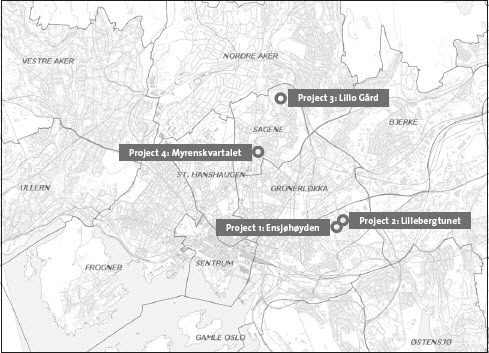

In order to explore whether and, if applicable, how the Oslo model is able to establish a basis for integrative negotiations, four processes of granting planning decisions for real estate development projects in Oslo have been analysed – two projects where VPOR has been used as the informal planning frameworkFootnote2 and two projects planned based on the ordinary statutory planning system. See for the location of projects and for details about each project. In order to reduce the risk that different attitudes towards negotiations among various property developers and responsible departments of the planning authorities would affect the analyses, it was decided to refine the analysis to two different but experienced developers operating in two neighbourhoods of Oslo. The planning processes were completed in the period 2011–2017, conducted by real estate developers OBOS and Neptune Properties, with one plan with and one without VPOR respectively.

Fig. 2: Location of the four cases in Oslo, Norway. (Source of map: https://od2.pbe.oslo.kommune.no/kart)

Fig. 3: Project 1: Ensjøhøyden. (Source: http://www.ensjohoyden.no/galleri/)

Fig. 4: Project 2: Lillebergtunet. (Source: https://www.obos.no/privat/ny-bolig/boligprosjekter/oslo/lillebergtunet

Fig. 5: Project 3: Lillo Gård. (Source: https://lillogard.no/)

Fig. 6: Project 4: Myrenskvartalet. (Source: http://www.myrenskvartalet.no/galleri/)

Although not a part of the chosen criteria for selecting cases for this empirical study, all four projects are located in designated transformation areas in Oslo’s Municipal Master plan. There will always be some ongoing privately initiated planning processes throughout the construction zone (infill projects). However, the bulk of the construction in Oslo for the last couple of decades has been located in designated development areas.

The data collection follows a multiple, embedded case study design (Yin Citation2018). The four Detailed Zoning plans are the case units. Study questions concern how and why the parties to the negotiations leading to the proposed zoning plans acted as they did. The initial study proposition was that informal non-statutory strategic plans (VPOR) entail more efficient processes and lower levels of conflict. For this reason, the case study was designed in order to contrast processes guided by non-statutory strategic plans (VPOR) with processes solely based on statutory planning. In order to isolate the effects of VPOR from other potential explanatory variables as much as possible, the cases were limited to (1) housing projects with a minimum of 50 apartments in (2) comparable urban environments. Furthermore, the cases were chosen so that (3) it was possible to compare how the same private developers behaved in the two different situations (with/without VPOR). The criteria led to the cases being selected in two geographically delimited transformation areas, both relatively centrally located in Oslo. Furthermore, the cases were selected from two property developers with comparable projects in both transformation areas. One of the developers is a major national developer, the other a significant local developer in Oslo. By choosing two relatively different developers, it was possible to assess whether the developer’s status with the planning authorities affected the outcome of the negotiations.

Data was collected partly through qualitative semi-structured interviews with leading actors both at the developers and in the agency for planning and building services. Data was also collected through quantitative and qualitative document studies of planning documents. Documents concerning land-use planning, including documents produced and exchanged between the parties negotiating privately initiated Detailed Zoning plans, are publicly available in Norway and relevant documents were obtained through searchable databases on the web.

Discussion

The four planning processes can be analysed based on different parameters. Three factors seem to differentiate between the projects: type of negotiation, number of plans submitted for approval by the City Council and number of responsible planning officers involved in the negotiations. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, there is little evidence that the use of informal plans through VPOR instead of the ordinary statutory planning system has had a significant impact on the outcome of the planning processes.

All four Detailed Zoning plans are located within designated transformation areas, zoned in the Municipal Master plan for the City of Oslo. Except being designated as transformation areas, there are few guidelines in the Master Plan for the specific land use that may be permitted. An underlying premise is, however, that Oslo’s estimated need for new housing is to be covered. The main new zoning objective for all four projects is housing. For the two cases subject to VPOR, some more detailed guidelines, however informal, have been provided in generic terms for street infrastructure, urban green structure and land-use goals with specified density. In the two cases following the ordinary statutory planning system, urban green structure and, to some extent, the street infrastructure and land-use objectives are determined through the statutory Master Plan.

Due to the generic nature and complex goals of both the municipal Master Plan and the informal VPOR, all four cases contain the multidimensionality suitable for integrative negotiations. There seem to be only small factual differences between the statutory and informal plans regarding their ability to control urban transformation. Nor do there appear to be significant differences in how the parties have invested time and resources in the planning processes. In all four cases, several meetings have been held between developers and planning authorities. A number of proposals for plans and more detailed elaborations on how to solve specific problems have been prepared and adjusted during the process of creating the final plans submitted to the City Council for a decision.

The question of whether the parties have the necessary competence to conduct integrative negotiations is somewhat more difficult to answer. Both property developers have extensive experience in conducting such negotiations. Furthermore, the financial burdens associated with real estate development should motivate developers to develop the necessary skills for integrative negotiation. Consequently, there is reason to conclude that both developers should have sufficient negotiating competence. However, for two projects – Project 2: Lillebergtunet (with VPOR, developer: OBOS) and Project 4: Myrenskvartalet (without VPOR, developer: Neptune Properties) – the developer’s preparation for the negotiating processes seems to have reduced the capacities for integrative negotiations. For project 2, the developer met at the start-up meeting with a fully developed project, including site plan, plan drawings, section and elevation drawings and a complete proposal for the Detailed Zoning plan. Hence, it became difficult for the developer to distinguish between positions and interests and accept adjustments to the plan. The planning authorities experienced that they had reached a situation where there was a better alternative than continued negotiations. Their BATNA was to promote their own alternative zoning plan for adoption by the City Council. For project 4, some actual information regarding the plan, section and elevation provided by the developer turned out to be incorrect, which meant that the planning authority lost trust in the developer and had to double-check a large amount of information.

With the large number of private proposals for Detailed Zoning plans that are discussed with the planning authorities at any time, the necessary competence should also be found there. However, two issues may challenge the planning authorities’ ability to provide the necessary negotiation skills in planning processes initiated by private developers. First, the large number of plans discussed at any time can put pressure on available capacity. Second, high turnover among planning officials at the planning authority occasionally results in frequent replacements of planning officers responsible for some privately initiated plans. Both conditions may cause the planning authorities to change focus from interests and back to positions. New and inexperienced planning officers with limited time and capacity to acquire adequate insight into the concrete issues of complex planning processes are likely to concentrate on more technical and quantifiable topics. In some cases, this could result in intentions of integrative negotiations diminishing into distributive, without this being a conscious strategy.

Consequently, it appears that the parties’ ability to establish mutual trust, rather than structural conditions, has been the central prerequisite for the ability to establish integral negotiations in the four planning processes. Two factors seem to have been decisive for whether developers and planning authorities have succeeded in commencing and continuing negotiations. First, if they have clearly managed to distinguish between positions and interests. Second, whether and to what extent they perceive the other party to be trustworthy. Two of the cases – Project 1: Ensjøhøyden and Project 2: Lillebergtunet – clearly started out as distributive negotiations. In Project 1, the planning authorities seemed to have problems trusting the developer’s integrity as a negotiator. Put another way, they did not want to take the risk of trusting the other party and then experiencing being exploited. Hence, they withdrew to distributive bargaining. Quite early in the process, they clarified that they were prepared to promote an alternative zoning plan for public inspection and, if necessary, for adoption by the City Council if the developer did not make the necessary changes to their plan proposal. Along the way, several replacements of senior planning officers lowered the trust between the parties, who were not even fully able to establish deterrence-based trust. However, the tense relationship changed after yet another replacement. A planning officer who the developers had previously had good dialogue with was able to restore trust. Distributive negotiations turned into integrative and knowledge-based trust was established. The process ended with the submission of a unified Detailed Zoning plan for approval.

Project 4: Myrenskvartalet clearly demonstrates the importance of trust. Due to the lack of accuracy in the information provided by the developer, the planning authority seemed to have questioned the developer’s ability to be a trustworthy party. This initial lack of trust developed throughout the negotiations into a situation questioning the benevolence and integrity of the developer. On the other hand, the developer seemed to have questioned whether several replacements of planning officers made the planning authority possibly unable to see the complexity of the project, while also questioning their benevolence towards the search for joint solutions. Overall, this project was characterised by a substantially high degree of perceived conflict.

The only case that clearly can be described as a truly integrative negotiation is Project 3: Lillo gård. Insiders described the process as “give-and-take”. Even if the developer came to the kick-off meeting with a thoroughly developed project, it seems that both parties’ propensity to trust the other developed into a climate of identification-based trust. In this case, two planning officers were involved. However, the second planning officer was appointed early in the process and, in practical terms, one planning officer handled the negotiations throughout most of the zoning process. It seems that both parties valued the ability, benevolence and integrity of the other.

The trust, or rather lack thereof, between the parties also seemed to be a consequence of structural choices made by the municipality. The procedural discretion of planning authorities to choose among several planning instruments and land-use plans, both statutory and informal, appears to have a significant role in the ability to build trust. Over time, the City of Oslo has used this discretion to develop a number of new instruments and plans for the dissemination of future land-use structures. Apparently, this has led to some degree of confusion among developers about the actual strength and status of the higher-level landuse plans. Rather than clarifying the framework conditions for negotiations on Detailed Zoning plans, this seems to have contributed to weakening their status, giving developers a belief that the space for the possible outcome of negotiations is greater than what the municipality intended to communicate. It may seem that this has contributed to weakening trust between the parties and thus also pulling the negotiations in the direction of distributive negotiations.

Conclusions

The planning authority in Oslo has developed its own model – the “Oslo model” – with the “Guiding Principle Plan for Public Spaces” (abbreviated VPOR) as a key instrument for informal strategic land-use planning, alongside the statutory system. They believe that this model is better suited to managing negotiations with real estate developers than traditional statutory planning alone. This paper contains a study of four planning processes initiated by two experienced property developers, two where VPOR is used and two based on traditional statutory planning. The findings from this study indicate that the statutory and legally binding planning system could work just as well as VPOR as the basis for integrative negotiations. There is reason to assume that this is largely a consequence of the use of more principled and overriding Land-use Element of the Municipal master plan of Oslo. This is a key point, allowing the planning system to be flexible enough to negotiate interests instead of positions.

On the other hand, it seems that the parties’ ability to trust each other is even more fundamental for both the opportunity to establish integrative negotiations and for the outcome of the negotiations. Predominantly two conditions seem to be important. First, the initial propensity of the parties to trust the other affects both parties’ assessments of the ability and benevolence of the other party’s ability to negotiate. In two of the cases in this study, it appears that the negotiators for the real estate developer had inadequate trust in the planning authority’s ability and benevolence to negotiate as early as the preparation phase, which means that they had gone a long way in developing completed plans before the start-up meeting. The lack of trust led them initially to lock in positional negotiations. In two of the cases, the relevant planning officer at the planning authority initially showed similar inadequate trust in the other party. Such propensity not to trust the other party necessarily leads to positional bargaining and consequently to reduced reluctance to use your BATNA. Second, the ability to maintain and build trust throughout the process seems to have significant influence on the immediate output and even the longer-term outcome of negotiations. Frequent changes of the negotiators responsible affect the climate of negotiations, substantially reducing the capacity for integrative negotiations. The immediate output is a reduction of trust, understood as the ability to conduct integrative negotiations. The outcome of such negotiations is more likely to be “win-lose” rather than the desired “win-win” situation. Frequent change of the negotiator responsible is a particular problem within the planning authority, due to high turnover. In two cases, the frequent change of planning officer contributed to the developers asking questions about the planning authority’s capacity to invest enough time and resources and, hence, the ability to negotiate.

A primal concern of both Norwegian statutory land-use planning and the informal strategic land-use planning of the Oslo model has been the system’s capacity to be proactive and plan-led. Both systems can be characterised as a deliberate attempt at introducing proactive and plan-led governance of the relationship between real estate developers and planning authorities, avoiding the commonly understood antagonistic attitudes toward each other. The changes implemented in the current planning law, with greater demands for hierarchical conformity, seem to work to some extent. At least, together with the principal and generic character of the Land-Use Element of the Municipal Master Plan in Oslo. Requirements for conformity and generic overall planning seem to have strengthened the plan-led dimension. At the same time, more generic Master plans seem to give the developer greater room to manoeuvre in line with their own goals as they initiate and propose private zoning plans. As most Detailed Zoning plans are initiated by real estate developers only when and where they need them, development-led planning still becomes dominant. Hence, the parties’ ability, benevolence and integrity as negotiators will be decisive for the outcome, both as seen by the planning authorities and the developers. There is reason to believe that such trust must develop over time. As such, the frequent changes of planning officers responsible and high turnover within the planning authorities poses a challenge for the opportunities to achieve the desired integrative negotiations with “win-win” solutions. However, as long as the parties to such negotiations pursue opposing interests and operate through quite different risk regimes, to some extent, conflict, positional behaviour and distributive negotiations are unavoidable.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Terje Holsen

Terje Holsen, Ph.D. Assoc. Prof. in Land-Use planning and Real Estate, Department of Property and Law, Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Teaching responsibiliIes: Masters level course on “Project initiation and project implementation in urban development”, Ph.D. and M.Sc. thesis supervision.

Notes

1 The empirical data presented in this paper derive from a Master’s thesis by Kind and Vedrana (2017) supervised by the author of this article. The case studies were designed jointly by the author and the two Master’s students.

2 Veiledende prinsipplan for det offentlige rom (VPOR) for Ensjø.

References

- Albrechts, L. (2006): Bridge the Gap: From Spatial Planning to Strategic Projects. European Planning Studies, 14 (10), pp.1487–1500. doi: 10.1080/09654310600852464

- Baker, D. C. et al. (2006): Performance-Based Planning. Perspectives from the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 25, pp. 369–409. doi: 10.1177/0739456X05283450

- Barlindhaug, R. et al. (2014): Boligbygging i storbyene – virkemidler og handlingsrom. NIBR-rapport 2014:8. Oslo: NIBR.

- Buitelaar, E.; Sorel, N. (2010): Between the rule of law and the quest for control: Legal certainty in the Dutch planning system. Land Use Policy, 27 (3), pp. 983–989. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.01.002

- Butler, J. (1999): Trust Expectations, Information Sharing, Climate of Trust, and Negotiation Effectiveness and Efficiency. Group & Organization Management, 24 (2), pp. 217–238. doi: 10.1177/1059601199242005

- Børrud, E. (2018): Områderegulering – forventning om helhet og sammenheng. In Hanssen, G. S.; Aarsæther, N. (eds.), Planog bygningsloven – fungerer loven etter intensjonene? Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Dalton, L. C. et al. (1989): The Limits of Regulation. Evidence from Local Plan Implementation in California. Journal of the American Planning Association, 55 (2), pp. 151–168. doi: 10.1080/01944368908976015

- de Vibe, E. (2015): Hvor går vi fremover? Oslomodellen for bruk av planog bygningsloven. Plan, 46 (1), pp. 32–35.

- Fisher, R. et al. (1991): Getting to yes. Negotiating an agreement without giving in. 2nd edition. London: Century Business.

- Frank, S. P. (2009): Yes in My Backyard: Developers, Government and Communities Working Together Through Development Agreements and Community Benefit Agreements. Indiana Law Review, 42, pp. 227–255.

- Green, S. D. (2004): Development Agreements: Bargained-for Zoning That Is Neither Illegal Contract Nor Conditional Zoning. Capital University Law Review, 33, pp. 383–497.

- Hals, H. (1929): Fra Christiania til Stor-Oslo. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Hanssen, G. S.; Aarsæther, N. (2018): Behov for en bro mellom kommuneplanens samfunnsdel og arealdel. In Hanssen, G. S.; Aarsæther, N. (eds.), Planog bygningsloven – en lov for vår tid? Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hartmann, T.; Spit, T. (2014): Dilemmas of involvement in land management – Comparing an active (Dutch) and a passive (German) approach. Land Use Policy, 42, pp.729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.10.004

- Hirt, S. (2013): Form Follows Function? How America Zones. Planning Practice & Research, 28 (2), pp. 204–230. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2012.692982

- Holsen T. (2019): A path dependent systems perspective on participation in municipal land-use planning in Norway. Paper delivered to the AESOP annual conference, Venice 9–13 July.

- Holsen, T. (2020): Forhandlinger ved private for-slag til reguleringsplaner. In Sky, P. K.; Elvestad, H. E., Eiendom og juss, vol. 1. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kalbro, T.; Røsnes, A. E. (2013): Public Planning Monopoly – or Not? The Right to Initiate Development Plans in Norway and Sweden. In Hepperle, E. et al. (eds.), Land Management: Potential Problems and Stumbling Blocks. Zurich: VDF Hochschulverlag AG, pp. 49–65.

- Kayden, J. S. (1992): Market-Based Regulatory Approaches A Comparative Discussion of Environmental and Land Use Techniques in the United States. Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review, 19, pp. 565–580.

- Kind, A. M. O.; Lozancic, V. (2017): Hvordan påvirker Veiledende plan for det offentlige rom (VPOR) planprosessen? Masteroppgave, NMBU: Ås.

- KMD (Kommunalog moderniseringsdepartementet) [Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation] (2018): Reguleringsplanveileder [Zoning Plan Guidelines]. Oslo: KMD.

- Kong, D. T. et al. (2014): Interpersonal trust within negotiations: Metaanalytic evidence, critical contingencies, and directions for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 57 (5), pp. 1235–1255. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.0461

- Lai, L.W. C. (1994): The economics of land-use zoning. A literature review and analysis of the work of Coase. Town Planning Review, 65 (1), pp. 77–98. doi: 10.3828/tpr.65.1.j15rh7037v511127

- Lewicki, J. R.; Polin, B. (2013): The role of trust in negotiation processes. In Bachmann, R.; Zaheer, A. (eds.), Handbook of Advances in Trust Research. 2nd revised edition. Edward Elgar Pub, pp. 161–190.

- Lowi, T. (1964). American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political Theory. World Politics, 16 (4), pp. 677–715. doi: 10.2307/2009452

- Mayer, R. et al. (1995): An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20 (3), pp.709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

- McCarthy, A.; Hay, S. (2015): Advanced Negotiation Techniques. Berkley: Apress.

- Muñoz-Gielen, D.; Tasan-Kok, T. (2010): Flexibility in Planning and the Consequences for Public-value Capturing in UK, Spain and the Netherlands. European Planning Studies, 18 (7), pp. 1097–1131. doi: 10.1080/09654311003744191

- Mäntysalo, R. et al. (2011): Between Input Legitimacy and Output Efficiency: Defensive Routines and Agonistic Reflectivity in Nordic Land-Use Planning. European Planning Studies, 19 (12), pp. 2109–2126. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.632906

- Mäntysalo, R. et al. (2015): Legitimacy of Informal Strategic Urban Planning – Observations from Finland, Sweden and Norway. European Planning Studies, 23 (2), pp. 349–366. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.861808

- NOU [Official Norwegian Report] (2003): Bedre kommunal og regional planlegging etter planog bygningsloven [Better municipal and regional planning under the Planning and Building Act]. NOU 2001: 7.

- Oslo: Statens forvaltningstjeneste. Proposition to the Storting 32 B (2008): Om lov om planlegging og byggesaksbehandling (planog bygningsloven) (plandelen) [About the Planning and Building Procedures Act (Planning and Building Act) (the planning section)]. Oslo: Miljøverndepartementet.

- Rognes, J. (2015): Forhandlinger. 4. Utgave. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Røsnes, A. E. (2002): Regulatory Systems and the Enabling of Plans. Paper delivered to FIG XXII International Congress, Washington D.C., April 19–26.

- Røsnes, A. E. (2005): Regulatory Power, Network Tools and Market Behaviour: Transforming Practices in Norwegian Urban Planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 6 (1), pp. 35–51. doi: 10.1080/1464935042000334958

- Selmi, D. P. (2011): The Contract Transformation in Land Use Regulation. Stanford Law Review, 63, pp. 591–645.

- Valtonen, E.; Falkenbach, H; Viitanen, K. (2017): Development-led planning practices in a planled planning system: empirical evidence from Finland, European Planning Studies, 25 (6), pp. 1053–1075. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1301885

- van der Krabben, E.; Jacobs, H. (2013): Public land development as a strategic tool for redevelopment: Reflections on the Dutch experience. Land Use Policy, 30 (1), pp.774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.06.002

- Yin, R. K. (2018): Case study research and applications. Design and methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.