Abstract

Urban sprawl in Latin America is described as one of the major problems of ‘the growth machine’. As a reaction, most planning policies are based on anti-sprawl narratives, while in practice, urban sprawl has been thoroughly consolidated by all tiers of government. In this paper – and using the capital city of Chile, Santiago, as a case study – we challenge these anti-sprawl politics in light of the emerging environmental values and associated meanings of the interstitial spaces resulting from land fragmentation in contexts of urban sprawl. Looking at the interstitial spaces that lie between developments becomes relevant in understanding urban sprawl, considering that significant attention has been paid to the impact of the built-up space that defines the urban character of cities and their governance arrangements. We propose that looking at Santiago’s urban sprawl from the interstitial spaces may contribute to the creation of more sustainable sprawling landscapes and inspire modernisations beyond anti-sprawl policies. Finally, it is suggested that a more sustainable urban development of city regions might include the environmental values of suburban interstices and consider them as assets for the creation of more comprehensive planning and policy responses to urban sprawl.

1 Introduction

Urban sprawl has evolved over the years from residential communities towards more complex environments characterised by multifunctional land-uses, decentralisation of industry, polycentric structuring, and alternative modes of suburban governance (Hamel, Keil Citation2015). This increasing complexity is partly the outcome of overlapping processes of governance and provision of infrastructure at regional scales in which land fragmentation resonates at both institutional and spatial levels (Irwin, Bockstael Citation2007). Assuming this fragmentation, the resulting sprawling geography of city-regions is composed of a mix of built-up areas and interstitial spaces that lie between developments. Such interstices are the outlying geography of metropolitan regions existing between the developed or urbanised areas produced alongside the urbanisation process (Phelps, Silva Citation2017). As such, an interstitial space would be a space ‘surrounded by other spaces that are either more institutionalized and therefore economically and legally powerful, or endowed with a stronger identity, and therefore more recognizable or typical’ (Brighenti Citation2013: xvi). It is important to notice, however, that this definition can be complemented by the fact that the ‘interstitiality’ is an in-between situation that emerges as a ‘gap’ of something; as such, it is mainly a context-dependent condition. On this basis – and from a developer perspective – an interstitial space can also be a well-integrated but clearly sub-densified area within heavily densified surroundings. Thus, the spectrum of interstitial spaces would typically include open spaces, natural areas, obsolete infrastructures, undeveloped lands, open tracts, geographical restrictions, leftover spaces, farming lands, as well as less densified areas within the fabric of cities that contribute to its environmental and functional performance. At an urban scale, the interstitial spaces are often described by unused parks, abandoned sites, and the leftover spaces often identified as ‘lost spaces’ (Trancik Citation1986), which are latent, dormant, partially used, or in a transition to becoming definitively urbanised (Kamvasinou, Roberts Citation2014).

At a larger scale, the spaces between metropolitan areas are those usually identified as part of ‘the countryside’, a ‘glaringly inadequate term for all the territory that is not urban’ (Koolhaas Citation2021: 3). A similar inference applies for ‘the rural’ as the ‘claim that the notion of a purely “rural” realm occupying the interstitial spaces between cities is archaic and misleading’ (Storper, Scott Citation2016: 1128) considering the diversity of in-between territories: spaces between cities and regions that include rural areas as well as oceans, beaches, deserts, forests, mountain ranges, farming sites, industrial agriculture, spaces of resource extraction, tourist regions, and any other non-strictly cityspace. All these interstitial spaces – at micro and macro scales – constitute eclectic geography that enables different strategies of densification and retrofitting to accommodate further growth, while also feeding narratives of planetary urbanisation (Brenner, Schmid Citation2014), and large-scale climate change and adaptation strategies (Hugo, du Plessis Citation2020).

Apart from their functional importance, interstitial spaces signify the suburban context in social and environmental terms, opening further questions around the negative connotations of urban sprawl. By focusing on smallscale interstices, Brighenti (Citation2013) argues that the spaces between buildings, under bridges, or abandoned urban lands can be occupied by marginalised groups where alternative modes of social organisation emerge. Similarly, Shaw and Hudson (Citation2009) refer to interstitial spaces as catalysts of alternative artistic expressions, highlighting the creative ways in which the interstices are occupied and how they challenge ideas of ‘place-making’ and social order. Dovey and King (Citation2012) refer to informal practices that occur in these ‘urban interstices’ – such as trading, parking, hawking, begging and advertising – tied to the also informal morphologies that support them; informal settlements themselves take a spatial position in cities as ‘urban interstices’ because of the morphological contrast with the institutionally produced space (Dovey, King Citation2012). Tonnelat (Citation2008) describes the ‘interstices’ as transitional spaces where immigrants are integrated into society.

While the ecological and social potentials of interstitial spaces have been clarified, little attention has been given to their environmental values and associated social meanings and how they contribute to the sustainability of sprawling geographies. Interstitial spaces are not mere empty sites but active spaces that can become influential in the promotion of more sustainable suburban landscapes. In this paper, these environmental values and meanings are highlighted. The varied morphologies of interstices, their temporalities, scales, and relationalities configure rich geography that embraces alternative conceptions of rurality, green infrastructure, human ecologies, natural heritage, history and culture and urban-rural transitions that deserve closer attention including reflections on the political meanings of the type of suburbia they suggest (Gandy Citation2011). We begin by reviewing urban sprawl and how interstitial spaces emerge as part thereof. These provide insights about the origins of interstitiality and their spatial characteristics that we combine in a subsequent section situating their environmental meanings. In the next section, we provide key examples from the southern area of Santiago de Chile to demonstrate how interstitial spaces contribute to the environmental characterisation of Santiago’s suburban sprawl. The conclusions underline the environmental values and meanings of interstitial spaces and how they suggest a more sustainable urban development. As such, the contribution of the paper is twofold. First, while the focus thus far has been almost exclusively on urban manifestations, the paper draws attention to the non-urbanised geographies lying between built-up lands and metropolitan areas; second, the paper unveils the environmental potential of interstitial spaces. In doing so, interstitial spaces support both natural and societal processes alike (Naveh Citation2000).

2 Urban sprawl, sustainability, and interstitial spaces

Urban sprawl is a contradictory phenomenon in terms of politics as, while it can be credited with fostering global economic growth and stability, it has also been pointed to as the cause of significant repercussions on climate change and oil depletion (Phelps Citation2015). In Latin America, urban sprawl is characterised by fragmented growth around transport infrastructure (Inostroza et al. Citation2013), the peripheral concentration of large social housing developments (Coq-Huelva, Asián-Chaves Citation2019), consolidation of outer (upper class) gated communities (Vidal-Koppmann Citation2021; Roitman, Phelps Citation2011), and fragmented expansion driven by ‘auto construction’ and privatised implementation of housing with important consequences for social and spatial segregation (Monkkonen et al. Citation2018; Heinrichs, Nuissl Citation2015). As such, urban sprawl is one of the main motives for the implementation of urban sustainability strategies, including containment policies and functional intensification (Ahani, Dadashpoor Citation2021). Cases in point are the ‘green belts’ (Dockerill, Sturzaker 2019), ‘urban limits’ (Morrison Citation2010), ‘Urban Growth Boundaries’ (Lang Citation2002), and the ‘Rural-Urban Boundary’ (RUB) in New Zealand and Australia (Silva Citation2019). In Latin America, the implementation of an ‘urban limit’ has been debated considering impacts on the land market and that it does not restrain urban sprawl (Vicuña del Río Citation2017). These policies, indeed, often stimulate further urbanisation of the countryside in the way of ‘leapfrogging’ development (Zhang et al. Citation2017). In terms of functional intensification, empirical studies advocate for the creation of multi-functional and spatially diverse (post)suburban places (Phelps, Woods 2011). Moreover, policies of retrofitting have derived into ‘compact’ and polycentric urban sprawl (Burger, Meijers Citation2012; Ståhle, Marcus Citation2008) often illustrated by the cases of the Randstad in the Netherlands (van der Wouden Citation2020) or the Finger Plan of Copenhagen (Xue Citation2018). Based on the case of Oslo, Røe and Saglie (Citation2011) propose a model for urban sustainability through the consolidation of suburban ‘minicities’, functionally self-sufficient districts with comparatively higher indicators of urban quality.

Although less discussed, this search for sustainability has also been examined through the lenses of land fragmentation (Ntihinyurwa et al. Citation2019). This fragmentation talks about both physical and political (Colsaet et al. Citation2018), and the ambiguous urban-rural nature of urban sprawl where non-urbanised lands are confined by – or in-between – built-up areas. Hebbert (Citation1986) earlier observed that ‘the built-up area of any modern city tends to be surrounded by a transitional zone which is neither fully urban nor fully rural but instead displays a mixture of uses and building types interspersed with agricultural and vacant land’ (141). This mixture and the non-contiguous character of sprawling landscapes include pieces of the countryside, farmlands, forest lands, geographical accidents, industrial lands, empty sites, leftover spaces, buffers of security, open tracts, green/blue corridors, restricted zones, and other non-urbanised areas that characterise urban sprawl. The emergence of these interstitial spaces relates to different geographical, social, economic, infrastructural, and policy-based determinants (Silva Citation2019). It has also been clarified that physical constraints – such as hills, fertile lands, floodplains, landslides, lands without accessibility and/or feasibility of water and energy supply, unsuitable land sizes, lands with a very thin soil layer or no/little water sources and others – are not suitable for new developments; their physical constraints affect building costs that keep them undeveloped. Additionally, lands with irregular shapes remain leftovers as ‘parcels that are extremely elongated, many-sided, constricted at one end, and the like do not lend themselves to usual forms of development, especially involving construction of a building’ (Northam Citation1971: 351). The urbanisation of outer locations driven by housing affordability policies and the provision of open space also determine the presence of interstitial spaces. So, residents accept longer commutes in exchange for lower-priced houses while the interstitial spaces become ‘the commuting space’ (Gallent, Shaw Citation2007). In many European cities, open space plays an important role in local planning, which engages municipalities and multiple actors in partnership projects to attract a new population. Named ‘discrete landscapes’ (Santos Citation2017: 7), local planning interventions consider interstitial spaces as fragmentation of suburbia to ensure immaterial qualities of the space (ibid 2017).

Lands without physical or regulatory restrictions can nevertheless remain undeveloped considering windfall gain. This is exacerbated in places with no taxation on empty lands or impact fees for regressive investment. Some of these interstitial lands are further commodified by plans and urban design projects that contemplate further profits on future development (Stanley Citation2014). There is enough evidence of land-banking strategies as a leitmotif for the creation of interstitial spaces (van der Krabben, Jacobs Citation2013). As part of normative planning, interstitial spaces appear in master plans for future growth or in the form of buffer zones, industrial sites, reservoirs for residential and institutional growth, or future public space (Talen Citation2010). Planners tend to identify interstitial areas as ‘buffers’ between incompatible functions – such as industries and residences (Zhang et al. Citation2013). In the South African context, interstitial spaces were also implemented to socially segregate cities, so, they ‘formed part of the apartheid city planning strategies to separate different racial groups’ (Hugo, du Plessis Citation2020: 593). Graham and Marvin’s ‘splintering urbanism’ (2001) highlights the leftover spaces resulting from the implementation of heavy infrastructures of connectivity. The infrastructure of networks – such as pumping stations, telephone exchanges, electricity power plants, railway services and motorways – are ‘often closed and recycled, as cities sourced their power and water resources from further afield (…) the huge technological networks of ducts, pipes, conduits and wires were themselves relegated to the urban background’ (Graham Citation2000: 183). Similarly, lands with restricted access also produce interstitial spaces, which emerge when the urban expansion reaches outer military facilities, chemical and/or power (nuclear) plants, mining sites, high-tech enclaves, upper class gated communities, heavy industries and others (Arboleda Citation2016; Bagaeen Citation2006). It has also been demonstrated that ‘with shrinkage and numerous demolition programs, vacant spaces became very important’ (Dubeaux, Sabot Citation2018: 8).

3 The environmental values of suburban interstices

Interstitial spaces have varied spatial attributes that qualify urban sprawl in morphological, functional, and environmental terms (Douglas Citation2008). Looking at these qualities, what is an ‘undeveloped land’ – or simply a leftover space through a development perspective – can be an unambiguous ‘ecotone’ or a very well-defined zone of transition between two or more ecological communities (Odum, Barret Citation2006). Yet the interstitial spaces provide valuable insights into the environmental processes that flourish at the margins of urbanisation (Brenner, Elden Citation2009); the question is whether these environmental qualities can be analysed through current planning rationales for ‘the city’ as in some way the interstitial spaces suggest alternative points of entry into the studies of the urban space. This has been suggested by Sieverts (Citation2003), who illustrates how the Zwischenstadt becomes non-continuous geography that is more an ‘urbanised countryside’. As such, urban sprawl is ‘neither city nor landscape, but which has characteristics of both’ (Sieverts Citation2003: 3). Here, the system of interstitial spaces emerges as an environmental signifier that cannot simply be conceptualised as buildable land but as a key component of sprawling geographies: ‘the grain and density of development of the individual urban areas and the degree of penetration with open spaces and landscapes determine the specific character of the Zwischenstadt (ibid: 9); a geography where ‘the landscape becomes the glue’ (ibid: 9).

3.1 Suburban interstices as green networks and infrastructure

It is known that suburban farmlands, parks, woods, shrubs, and other green interstices have ‘an important role in controlling evapotranspiring processes and in mitigating urban pollution inside highly urbanized settlements’ (La Rosa, Privitera Citation2013: 96), and contribute to ‘preserve biodiversity, sequester CO2, produce O2, reduce air pollution and noise, regulate microclimates, reduce the heat island effect, affect house prices, have recreational value and are useful for health, well-being and social safety’ (ibid: 94–95). Studies on open spaces and suburban green infrastructure have also highlighted the environmental benefits associated with stormwater management (Hoover, Hopton Citation2019), conservation of biodiversity (Aronson et al. Citation2017), and provision of ecosystem services, including effects on social sustainability (Derkzen et al. Citation2015). Detailed soil taxonomies allow for identifying the specific capacity of interstices to retain infiltration, improve absorption, and drain large amounts of water (Barkasi et al. Citation2012). Studies on urban porosity conclude that cities need ‘innovative solutions that lever existing unused and underutilized interstitial spaces within the urban fabric for climate change adaptation and mitigation purposes’ (Hugo, du Plessis Citation2020: 591) and that ‘identifying and using these unused and underutilized interstitial space networks present the potential to insert small-scale climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies within the city, whilst retaining its overall functionality’ (ibid: 593). Essential to this strategy is a better understanding of the quantity of underused and leftover interstices and how they connect to strengthen metropolitan resilience (Santos Citation2017).

3.2 Interstitial spaces as intra-urban boundaries

Sociological approaches have also drawn attention to interstitial spaces as boundary spaces, or environments of transition between different places or socially differentiated groups. As boundary spaces, the meanings of interstices can be socially constructed and used to minimise ambiguity around the rights and ownership of space (van Houtum, van Naerssen Citation2002). Boundary spaces can be closed and rigid (such as military or industrial sites), or open and permeable (such as parks and open green spaces), and articulate socio-spatial interchange between surroundings in various ways. These interchanges illustrate the relationality of interstitial spaces that can connect or separate places (Phelps, Silva Citation2017) as well as their flexibility considering ‘their location and especially their character, openness and impacts are constantly renegotiated’ (Breitung Citation2011: 57). As such, interstitial spaces can become symbolic infrastructures that speak about social integration and contestation and dispute between communities: zones of contact at the edge of differentiated groups in terms of wealth, the religion of programmatic focus (Herrault, Murtagh Citation2019). The interstices between religious communities in Belfast, Northern Ireland, are examples of these boundaries in which the ‘peace walls’ are not mere physical elements but embedded symbols within the urban fabric (ibid 2019); elements of individual and collective significance that ‘beyond their functions and physical impacts, also carry meanings for people’s identities and daily lives’ (Breitung Citation2011: 57). This boundary condition would apply to the mediating spaces, devices, infrastructures and surroundings that confine the interstitial spaces and crystalise them as ‘objects which both inhabit several intersecting social worlds (…) and satisfy the informational requirements of each of them’ (Star, Griesemer Citation1989: 393). These are the cases in which ‘boundary crossing’ can be introduced as modes of entering an unfamiliar territory (Akkerman, Bakker Citation2011) and ‘face the challenge of negotiating and combining ingredients from different contexts to achieve hybrid situations’ (Engestrom et al. 1995: 319). Interstitial spaces are borderlands within cities; bridges between differing functionalities or self-contained (and bounded) urban enclaves (Iossifova Citation2013).

Similarly, Tonnelat (Citation2008) refers to suburban interstices as ‘zones of transitions’ – residual spaces between industrial facilities, roads, canals, and the poor tenements occupied by workers – in which immigrants learn about the local culture before moving into more permanent residences. Brighenti (Citation2013) has described these interstices as disorganised spaces used by marginal groups that react against official institutions or societal anomalies. According to Arvanitis et al. (Citation2019), interstices can also take the form of ‘liminal spaces’ where meaningful living experiences take place (the ‘rite of passage’) and in which different transformative social interactions occur for a specific period of time. As such, it is ‘of inferential significance here insofar as it is “located” in terms of both its geography and its constitutive temporality’ (Roberts Citation2018: 40).

3.3 Interstitial spaces as spatial signifiers of imaginative practices

On an urban scale, some suburban interstitial spaces are protected by plans and seldom changed. These are the cases of private gardens and community squares, or small parks. As part of the green space networks, these spaces are used to diminish air pollution, noise and increase biological patrimony. These interstices also become ecological entities that support ecosystem services at different levels (Kim et al. 2015) that ‘may also be described as conservation or protection from extreme intervention such as imposed by development’ (Maruani, Amit-Colen 2007: 3). As such, they diversify the spatial homogeneity of suburban neighbourhoods derived from housing standardisation while defining security zones or public spaces. These spaces also provide a sense of spatial stability, legibility, wellbeing, and orientation (Dennis, James Citation2017).

At an urban and regional scale, some interstitial spaces describe a range of spatial characteristics that influence their quality, facilities, and accessibility to enable different uses and forms of occupation (Ma, Haarhoff Citation2015). Their spatial quality defines different modes of interiority, intimacy, light and colouring, darkness, narrowness, amplitude, depth, diversity of perspectives, and textures ‘fundamental to increase urban quality creating more pedestrian friendly and visually pleasant settlements’ (La Greca et al. Citation2011: 2193). Suburban farming spaces, for instance, contribute to the spatial qualification of suburbia in an ‘urbanised countryside’ (van Leeuwen, Nijkamp Citation2006) and contexts of suburban rurality that have shifted from productivist farming towards an agricultural sector with a greater focus on food quality, environmental processes, and socially sustainable farming processes (Wickham et al. Citation2010). In the case of green interstitial spaces, their spatial diversity is partly determined by quality and distribution – key indicators to measure human interaction with nature – as they affect walking distances, time spending, and financial restrictions for supply and maintenance. Equal access is essential in achieving quality of life considering greater interaction and easier access to opportunities (van Wee, Geurs Citation2011). Accessibility is one of the key indices to assess geospatial relationships between citizens and socio-economic activities, while on a regional scale, it reflects the ease with which a certain area spatially interacts with other areas. The impedance between green spaces and residential areas, time, transportation modes, and attractiveness influence how people access certain services and imagine places as well as how institutional agencies deploy imaginative planning and design practices regarding improvement in functionality and the spatial quality (Ma Citation2016). As highlighted by Johnson et al. (Citation2019), ‘imaginative practices are central to ongoing transformations in the form and function of suburbia’ (1042); imaginaries deployed on interstitial spaces considering their transition to become something else. They offer experiences in the planning and establishment of ideal city forms and invoke images, representations, and ideologies of urban progress.

Less planned interstitial spaces and abandoned facilities become environmental assets by giving space to wild urban nature. These spaces include suburban woodlands, abandoned allotments, water canals and rivers, brownfield sites, and others where the city’s forces of control have not defined the space at all. These ‘wildscapes’ (Jorgensen, Keenan Citation2012) – despite their certain degree of marginality and abandonment – are scenarios of informal practices and collective imagination, above all in regions where residents are excluded from the experience with nature. These sites are spaces of multiple human ecologies and are beneficial for both human systems and nature alike ‘since they can give a contribution to the enhancement of urban settlement quality and to the improvement of human health’ (La Greca et al. Citation2011: 2201). Gandy (Citation2011) has extensively analysed these interstitial spaces in Berlin by highlighting their unexplored ecological and aesthetic contents. They are abandoned, marginalised, and somehow forgotten spaces where spontaneous and exuberant vegetation configures rich habitats for urban insects and birds. These interstitial spaces offer strong sensorial stimulation considering their particular aesthetics, random expressions of freedom, spontaneity and some hints of history and novelty at the same time. The spatially ambivalent condition of these environments appears as a prolific scenario to combine new cultural and scientific expressions of urban life; ‘practical challenges for the utilitarian impetus of capitalist urbanization’ (Gandy Citation2013: 1312).

The interstitial spaces of urban sprawl present different environmental values that are also discussed regarding their ideological meanings while supporting narratives of climate change (Matthews et al. Citation2015), environmental justice (Ambrey et al. Citation2017), the right to the city (Rigolon, Németh Citation2018), and health and social wellbeing (Tzoulas et al. Citation2007). As such, they serve as a conceptual basis for the creation of institutions and programmes worldwide ‘in which nature can be called to support other more dominant (or ‘harder’) political discourses’ such as ‘ecological modernisation’ (Thomas, Littlewood Citation2010: 212).

4 Methodology

4.1 Santiago de Chile as a case study

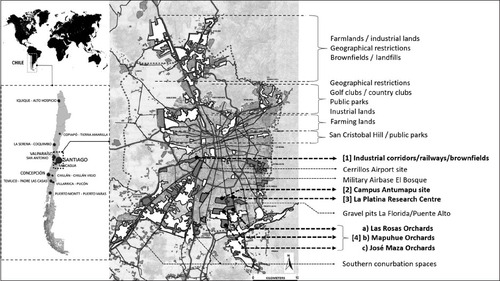

The analysis presented in this paper is based on the capital city of Chile, Santiago. The city illustrates common patterns of urban development observed in other Latin American cities defined by sprawling growth around transport infrastructure and peripheral location of housing (Flores et al. Citation2017; Inostroza Citation2017). This study specifically focuses on the southern metropolitan space of Santiago as it illustrates one of the highest rates of suburbanisation characterised by the massive location of social housing developments (Tapia Citation2011), population growth (de Mattos et al. Citation2014), eradication of slums (Paredes, Vásquez Citation2020; Suazo et al. 2020), location of upper-class residential developments (Fuentes, Pezoa Citation2018), expressions of suburban rurality (Silva Citation2019), lack of green and open space (Banzhaf et al. Citation2013), and the presence of transport infrastructure and industrial facilities (Sagaris, Landon Citation2017). These elements have configured a clearly differentiated environment compared to the north area, which has become the preferred location for upper-class (gated) communities with higher standards of urban quality and infrastructure (Hidalgo et al. 2019). Taken from the southern space of Santiago, a few interstitial spaces are used to illustrate their environmental values and how they qualify suburban sprawl ().

These selected interstices are large undeveloped sites of about 300 hectares identified by various actors as ‘strategic’ in light of their location, land capacity, connectivity, and distinctive environmental characteristics. These interstices are also the most contested spaces in the city, as different government bodies and institutional representations operate upon their current governance, including agricultural businesses, public works, housing, natural environment, research and education, and industries. These agencies have different interpretations of both current and future land uses of the interstices, a situation that leaves them undeveloped.

4.2 Research design, methodological approach and methods

The data and findings presented in this paper are distilled from a case study conducted between 2012 and 2021, in which a mixed methodological approach was used to articulate qualitative and quantitative data (Tashakkori, Creswell Citation2007). The methods included document reviews, site visits, morphological analysis and mapping, and semi-structured interviews with relevant actors. The analytical approach is based on the examination of policy conflicts and stakeholders’ understandings of Santiago’s urban development and interstitial spaces, allowing the examination of the extent to which planning policies affect the emergence of interstitial spaces in Santiago and their environmental values.

The policy review was based on Bowen’s approach (2009) in which documents are ‘social facts’ (produced, shared, and used in socially organised ways) that require finding, selecting, appraising (making sense of), and synthesising data contained in documents. The analytical procedure considered a selection of excerpts and quotations then organised into major themes, categories, and case examples specifically through content analysis (Gavin Citation2008). Selected policies considered The National Policy of Urban Development (NPUD/1979), the new version of the NPUD (2014), reports from the Institute of National Statistics (INE), the Metropolitan Development Plan of Santiago (PRMS/100), various local development plans, urban design proposals, master plans, and various ministerial reports from the Ministries of Public Works, Agriculture, Social Development, Environment, and Housing and Urban Development (MINVU) inter alia.

The data found in policy reports was triangulated with empirical data from official statistical databases (INE Citation2017), and information from the interviews (Stender Citation2017; Galletta Citation2013). Interviewees included politicians (senators, deputies), central and local authorities (local mayors, former ministries), policymakers, planners, urban designers, scholars, developers and business groups, residents, and members of social and environmental organisations. These interviews were designed in accordance with the sponsors’ ethical codes of conduct; key informants were anonymised, so that the respondents could be candid without fear of professional repercussions. Thematic analysis was implied to codify data into three categories regarding the nature of interstitial spaces: a) determinants, b) environmental values, and c) socio-political meanings, all linked to contents of policy documents (Evans, Lewis Citation2018).

Site visits and direct observations were used to assess the environmental quality and characteristics of the selected sites. This included observations and visual records on physical infrastructure, environmental and spatial attributes, functions and daily activities, accessibility, and quality of surroundings. Site visits were necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of existing environmental conditions – as secondary research on these sites is limited – and to contrast maps and written records (Collier, Collier Citation1986). Site visits were based on Rayback’s approach (2016) who indicates that observations, visual records, and measurements allow comparisons between two or more different cases to establish commonalities and differences and testing if a site meets the study goals.

5 Santiago’s suburban sprawl and its interstitial spaces

There is a growing consensus that Santiago’s urban development illustrates clear patterns of ‘urban sprawl’ (Silva, Vergara-Perucich 2021; Banzhaf et al. Citation2013). As such, it is characterised by a fragmented morphology, a permanent expansion to outer areas, high rates of car dependency, and the presence of varied interstitial spaces (Cox, Hurtubia 2020; Silva Citation2019). The geographic scope of Santiago’s sprawl is well-represented by Sieverts’ Zwischenstadt (2003), wherein suburbia, the peri-urban, and exurbia configure a distinctive geographical space where rural, industrial, infrastructural, residential, and interstitial lands coexist; a geography of interrelation between the consolidated city and the open countryside that ‘separates itself from the core city (…) and achieves a unique form of independency’ (ibid: 6). Santiago’ sprawl has been highly criticised by its environmental impacts (de la Barrera et al. 2018; Smith, Romero Citation2016), high rates of residential segregation (Fuentes et al. Citation2017; Gainza, Livert Citation2013), the concentration of poverty, and territorial disparities between municipalities (Heinrichs, Nuissl Citation2015). Indeed, efforts against segregation have been the focus of the urban debate in Chile in the last years considering that ‘the concern about a “social divide” and segregation between groups with different socio-economic status is very visible in the (extant) literature. This comes as no surprise, given that Latin American cities exhibit a high degree of segregation’ (ibid: 221). The unsustainable character of Santiago’s sprawl has consequently raised narratives of retrofitting and compactness – something of a Zeitgeist in architectural, design and planning circles – that have feed anti-sprawl discourses and the rise of planning ideas around sustainable and compact development and benefits of densification (Aquino, Gainza Citation2014; del Piano Citation2010).

Despite efforts, Santiago’s urban sprawl remains one of the most longstanding patterns of urban development and a permanent structure in the aftermath of The National Policy of Urban Development (NPUD/1979). This is partly because Santiago’s urban sprawl is more a product of modernists-inspired nations where capital cities reflect projects of national development driven by a neoliberal approach in policymaking adjusted to facilitate urban growth, land privatisation, and centralisation of social housing supply (Vergara, Boano Citation2020). Recent empirical studies have identified thirteen determinants of urban sprawl in Santiago that operate as interlinked. These determinants are derived from legal norms, housing policies, (urban-rural) institutional asymmetries, restrictive controls on urban growth, the creation of outer developments, and improvements in regional connectivity. All these determinants ‘are placed at different institutional levels – and with repercussions at different spatial scales – configuring a challenging policy context that calls for the development of theories of urban politics beyond normative rationales (…) and the supremacy of technical macro-scale plans’ (Silva, Vergara Citation2021: 28).

Like in most Latin American cities, interstitial spaces in Santiago have become qualitatively and quantitatively significant. Only the vacant lands represent around 19% of the total metropolitan area (Clichevsky Citation2007). This can be increased considering that planning authorities also count informal occupations that need to be demolished or eradicated, reaching a total of 23% of the whole urban space (Cámara Chilena de la Construction 2012). Furthermore, the interstitial spaces found in Santiago include agricultural and industrial lands, brownfields, landfills, public spaces, geographical restrictions, conurbation zones, former airports, military facilities, small-scale farming areas, research centres, infrastructural spaces, buffers of security, and even built-up areas ‘that can be further urbanised considering their lack of density in comparison with their surroundings’ (interview with Honorary advisor and real estate developer, Chilean Chamber of Construction, May 2014). Some of these interstitial spaces are currently well located near transport infrastructure, energy supply, services, and populated surroundings that make them attractive for both public and private investments. This poses important questions regarding the unsustainable character of urban sprawl that – despite coming under severe criticism – represents a major source of infrastructural and environmental assets (Gavrilidis et al. Citation2019), and describes clear scenarios for the implementation of innovative solutions in urban regeneration projects (Silva Citation2017). On a regional scale, conurbation zones become eclectic interstitial spaces defined by an amalgamation of infrastructures, empty sites, farming lands, abandoned industrial facilities, agglomeration hubs, and mining sites inter alia. As such, the conurbation space deserves closer attention considering that some of the most radical environmental alterations take place here (Arboleda Citation2020): a type of interstitial space that poses practical challenges by tackling the ‘rural question’ within critical urban studies (Harrison, Heley Citation2015).

6 The environmental values of Santiago’s interstices

The environmental values of Santiago’s interstitial spaces can manifest as green infrastructure – with reminiscences of rurality and social sustainability –boundary spaces, and spatial signifiers that stimulate imaginative practices on the present and future use of the space. These environmental values derive different social and political meanings linked to different ideologies associated with ‘the urban’. These connotations affect their integration and influence their role within planning policies, suburbia, and the metropolitan space.

6.1 Santiago’s suburban rurality and green space

For scholars, residents, and consultants on environmental sustainability, Santiago’s suburban interstices are ‘rural places’ within suburbia and as such, part of the green infrastructure network. These are the cases of various sub-urban vineyards and small-size farming plots surrounded by the suburban expansion. These interstitial spaces describe a category of rurality that resonates with Sieverts’ notion of an ‘urbanised countryside’ (2003) and projects of urban agriculture. The rural interstices are mainly located at La Pintana commune, recognised as the most fertile lands in the whole metropolitan region (ODEPA 2012; SINIA 2012). As currently well-located rural and green space, these interstices are often the subject of development pressures to become urbanised. However, some of them resist processes of land commodification by overpassing their infrastructural stand to become socially meaningful, and in which rurality becomes strongly tied to political resistance against land liberalisation.

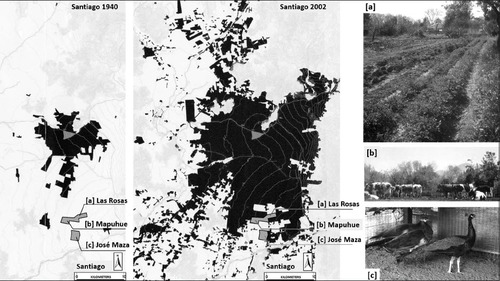

A case in point that demonstrates this resistance to land-use changes is the ‘Huertos Obreros y Familiares’ [Workers and Familial Orchards] of La Pintana commune. This is a system of half-hectare lands – divided into three main clusters: Las Rosas, Mapuhue, and José Maza Orchards – created in the 1940s as a social housing model composed of a house and a half-hectare site destinated to the cultivation of food and animal husbandry. The orchards became known for the production of seasonal vegetables, medicinal plants, animal husbandry, seasonal jam and handcrafted meat, vegetable seeds, hydroponics and organic compost inter alia, all distributed across the communal and regional space. Residents, environmental and social organisations see the orchards as ‘foodscapes’ internationally recognised by the provision of organic food (interview with Consultant in Local Food Systems, FAO-RLC, May 2014) ().

These orchards are opened to local schools and children who learn about nature, planting, cultivation, and healthy nutrition (Catalán et al. Citation2013). At present these are large green spaces that create a clear contrast with surrounding suburbanisation primarily composed of homogeneous social housing developments as a network of green spaces with social significance; these interstices contribute to balancing the distribution of metropolitan green infrastructure, cleaning the air, providing public space, and preserving micro-climates that minimise impacts of urban pollution:

“In the case of La Platina, the orchards and other green spaces help with decreasing the temperature of the whole metropolitan region through evapotranspiration. So, when the average temperature in Puente Alto [the neighbouring commune] is 4°C, here [in La Pintana] it is 0°C, which is an important difference. Also, underground water streams supply superficial water for the city, i.e. through these open tracts. In this light, La Pintana and the orchards are one of the key spaces to support the natural water drainage and other environmental services, with important impacts on the social life of people” (interview with the Director of Environmental Operations. Municipality of La Pintana, June 2014).

These orchards have the potential to support urban agriculture and educational projects, improve social organisation, and preserve historical practices in agriculture (Roubelat, Armijo Citation2012). They are widely recognised as healthy places and social venues where people can share and learn about nature:

“These rural spaces within the city have enormous educational impacts. You can take a kid here to see the bugs, animals and birds, or simply to explore and learn about the local flora. They can also improve their social skills while being in contact with other children, learn about planting trees and vegetables. These places have intangible values, unfortunately not included in the economic equations” (interview with professional advisor, National Department of Agriculture, May 2014).

6.2 The intra-urban boundaries of Santiago

Some interstitial spaces in Santiago are understood as spatial disruptions in the urban fabric, especially when they emerge as intra-urban boundaries between districts. These interstitial boundaries result from the implementation of heavy infrastructure of transportation as well as ‘administrative absences’ that correlate with political disparities. The boundary areas between municipalities appear as politically abandoned territories ‘as local authorities avoid placing services, amenities and infrastructure in the boundary space to avoid serving a neighbouring population that will then not vote for them’ (interview with the director of urban planning, Puente Alto Municipality, May 2014). Local mayors prefer to target their interventions at their own constituency, benefiting the population already enrolled as taxpayers and voters within the communal boundary. This situation ‘leaves municipal boundaries as politically ambiguous territories that remain undeveloped or in hands of central authorities’ (interview with Minister of Housing, Urbanization, and Public Lands 2001–2004, June 2014). As such, the boundary space tends to be used for the implementation of regional infrastructure or metropolitan artefacts such as shopping malls or metropolitan facilities of centralised maintenance: ‘these interstitial spaces emerge as divisions; spatial barriers between neighbourhoods and places that separate communities and make the city less efficient and spatially segregated’ (interview with Director of the Department of Regional Planning, Metropolitan Regional Government of Santiago, GORE, May 2014). This is the case of the inner motorways placed in the boundary between the communes of Pedro Aguire Cerda and Lo Espejo, or the different networks mingling at the boundary of Cerrillos and Pedro Aguirre Cerda communes ().

Fig. 3: An interstitial boundary space between Cerrillos and Pedro Aguirre Cerda.

(Source: Authors’ photo, 2016).

In these spaces, several transport and energy infrastructures – including regional motorways, buffers of security, railway services, water canals, or electricity lines – separate the interstice from the suburban fabric. Although they configure physical divisions and restricted areas, this intensive provision for mobility might signal significant regional economic potential. At the local level, they remain perceived as negative because of their pollution, or their lack of public access and connection with nearby employment sites. The networks of these interstitial spaces contribute to their functional indeterminacy and environmental ambiguity; the motorway and its leftover spaces coexist with the now less functional railway as the heritage of the former commercial heydays, and a polluted canal to evacuate industrial residues bounded by a few wild green areas. For local authorities these interstitial boundaries can be potential public venues; ‘reservoirs of public space – currently informally used – that could improve the living conditions of nearby surroundings if properly designed and physically incorporated into the city’ (interview with Director of urban planning, Municipality of Cerrillos, May 2014). These interstitial spaces can eventually facilitate transboundary interactions and socio-spatial transitions between districts, thus shifting their environmental character as territorial lines of divisions toward environments of political, social, and functional significance.

6.3 The spatial signifiers of Santiago’s suburbia

For local planners, residents, developers, and policymakers, Santiago’s suburban interstices describe non-standard environments that qualify homogenous suburbia derived from standardised housing developments. However, the environmental meanings of the interstices differ between actors and can even be contradictory. For central planners ‘Santiago’s interstitial spaces are wasted lands … lands out of the market, but also reservoirs of space to improve urban quality and standards and to implement workplaces and services at metropolitan levels’ (interview with National Director of Urban Development 2014–2018, MINVU, May 2014– 2018). This optimistic view is contrasted, however, by developers:

“These interstices are sometimes beautiful green and open spaces but generally inaccessible, and as empty sites they only create market distortions. Their environmental values are mainly defined by their condition as under-utilised spaces that are derelict, unsafe, lacking of maintenance, absence of grass, presence of stagnant water, and rotten materials. They are an invitation for informal occupations, and stimulate the arrival of wild animals and plagues such as rats, wild dogs, carrion birds; dead animals are here and there with bad smells” (interview with Honorary advisor and real estate developer, Chilean Chamber of Construction, C.Ch.C, May 2014).

A case in point is a site called ‘La Platina’ located at La Pintana commune. This is a 300-hectare site that functions as an agricultural research centre (Experimental Station La Platina) under the administration of the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA). This is mainly an open space used for cultivation and specialised research on fruit and vegetables, management of diseases, analysis of quality of agricultural products, water, and pesticide residues. As such, the environment is literally a ‘piece of the countryside’ within the highly densified suburban landscape of La Pintana that feeds the planning imagination of authorities and residents. The site is considered strategic by central and local authorities owing to its location, connectivity, land capacity, and lack of planning restrictions ().

Although partially abandoned and marginalised – as cultivation covers no more than 25% of the total land – surrounding residents understand the site as an opportunity to enrich the whole area and provide public and green space: “From this space, La Platina, it is possible to see the landscape, the mountains, and the grass. It is also possible to see how seasons change over the year. It is like having the countryside on your doorstep. Some days ago, it was snowing and that was simply beautiful. My daughter sometimes goes there to play and fly her kite. For 18 September [Independence Day] the place is full of people and families. As an open space it is just amazing, this is a space of freedom” (interview with Secretary of the committee of neighbours ‘Villa San Ambrosio III’, La Pintana, June 2014).

Although managed by the Ministry of Agriculture, the MINVU has reclaimed the site for new social housing units. The local municipality also uses the place for parks and amenities, while residents informally use it for recreation. Hence, the environmental values of the site have physical, spatial, functional, and social aspects. Moreover, although at present it mainly contributes to the ecological performance of the commune, it could also support improvements in local metropolitan social sustainability and inspire the institutional and popular imagination regarding the ideal life that can unfold.

Another similar case is the site known as ‘Campus Antumapu’ – also located at La Pintana commune. This is a 245-hectare site that belongs to the Universidad de Chile (the main public university), used for educational purposes related to agriculture and veterinary sciences. The site is slightly densified with a few institutional buildings located closer the Santa Rosa Avenue ().

Considering its non-intensive use, the site has been the subject of numerous projects. The university authorities aim to change the land use and rent or sell some portions for private farming. Local authorities, however, have projected several social housing developments, while central authorities have projected a stadium, commercial services, social housing, and metropolitan public space. The university currently has an alternative master plan that contemplates housing, public space and services. Local residents describe the site as an idyllic rural atmosphere that inspires the imagination as it offers a different ‘rural experience’ while offering learning about vegetables, gardening, agriculture, animal husbandry, and scientific exploration led by the academic staff:

“If you walk in that direction, you can see the mountains, butterflies and bees while you are talking to one of the professors. This is not common in other open spaces in Santiago. You can perceive the rurality much better while still in the city, and your sensitivity is better when you learn about what you are experiencing. Yesterday, it was snowing, and children, students, and teachers were playing and talking together. We can observe the children wandering around, climbing trees, chasing butterflies, drawing animals, talking to the researchers or simply playing with the grass as the place offers good views” (interview with resident at Villa Ambrosio III, La Pintana, June 2014).

7 Conclusions

The search for urban sustainability has become a permanent objective for planners, policymakers, and scholars, above all in light of the impacts of urban sprawl. Part of this search has been focused on controlling extended suburbanisation through restrictions to suburban growth and enhancing suburban intensification. However, less examined are the interstitial spaces produced alongside the urbanisation process that are spatially, functionally, and environmentally diverse. In this paper, we conceptualised the environmental values of these interstitial spaces as green infrastructure, boundary spaces, and spatial signifiers of imaginative practices. Using the case of Santiago de Chile, we examined how these environmental values contribute to diversifying the sprawling context of cities while embracing complex socio-ecological processes and different modes of social engagement. The interstitial spaces offer a range of spatial and infrastructural diversification that situate them as rich sources of the collective imagination. These values are inherently connected with the social and planning constructions around the impacts of suburban interstices as abandoned spaces, but also their environmental potentials in such a way that each interstitial space can be fully understood only in relation to the city.

It has been clarified that the interstices of Santiago’s urban sprawl are not inert or ‘empty’ spaces. They are composed of a variety of spatial characteristics and functions that frame their environmental values. As green infrastructure, Santiago’s interstices support planning policies linked to social and environmental sustainability. Further, as boundary areas, they separate and connect different surroundings while hosting varied and intermingled infrastructures. As spatial signifiers, Santiago’s interstitial spaces encompass collective interpretations around dignity, memory, learning, science, ecology, rurality, landscape, community, history, and future life while still abandoned, functionally obsolete or unattended. As such, they highlight the role of specific representations of urban space in informing the expectations of residents, planners and policymakers, and crystalise their role as signifiers in the realisation of suburban ideals or construct new notions of ‘the good city’. The environmental values of Santiago’s interstitial spaces reflect the impetus of collective consumption as well as the collective imagination in the production of the space as a mode of participation and inclusion. They qualify Santiago’s suburbia and may support a more sustainable urban development if codified in planning and included in debates around ‘the urban’, environmental services, and the environmental character of sprawling city regions. In that sense, interstitial spaces are interfaces between various types of knowledge and urban systems including infrastructure, neighbourhoods, and metropolitan planning.

Santiago’s suburban sprawl further confirms that a certain range of urban processes, imaginaries, and emerging ecologies do occur in interstitial spaces – functions that are intrinsically urban and highly place-specific – proving that interstices are far from being delinked from what makes cities ‘urban’ and thus, what can potentially shift Santiago’s unsustainable sprawling development. Aside from binomial debates around urbanisation versus preservation, interstitial spaces suggest a more interdisciplinary approach to the urban sprawl phenomenon by expanding theories about the ‘the city’ to the non-urban geographies within, between, and beyond cities and regions, and the intrinsic environmental services that are part thereof.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the interviewees for providing data and valuable insights for this article. The author is also grateful to the reviewers and the editors for helpful comments and suggestions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cristian Silva

Dr Cristian Silva has a PhD in Urban Studies (UCL) and is a Lecturer in Spatial Planning at Queen’s University Belfast. His research profile lies in the intersections between urban planning, urban design, and social theory. His current research is centred on the explorations of contemporary patterns of urban growth and change, urban sprawl, and (post) suburbanisation, with a particular emphasis on the role of ‘interstitial spaces’ in restructuring city-regions.

Jing Ma

Dr Jing Ma works as an Associate/Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning in the Division of Architecture and Water at Luleå University of Technology, Sweden. Her research focuses on green infrastructure planning and management, the role of perceptions in sustainable development, and various factors that influence decision-making for improving the quality of life.

References

- Ahani, S.; Dadashpoor, H. (2021): Urban growth containment policies for the guidance and control of peri-urbanization: a review and proposed framework. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23, pp.14215–14244.

- Akkerman, S. F.; Bakker, A. (2011): Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 81 (2), pp. 132–169.

- Ambrey, C.; Byrne, J.; Matthews, T.; Davison, A.; Portanger, C.; Lo, A. (2017): Cultivating climate justice: Green infrastructure and suburban disadvantage in Australia. Applied Geography, 89, pp. 52–60.

- Aquino, F. L.; Gainza, X. (2014): Understanding density in an uneven city, Santiago de Chile: Implications for social and environmental sustainability. Sustainability, 6 (9), pp. 5876–5897.

- Arboleda, M. (2016): In the nature of the non-city: expanded infrastructural networks and the political ecology of planetary urbanisation. Antipode, 48 (2), pp. 233–251.

- Arboleda, M. (2020): Planetary Mine. Territories of Extraction Under Late Capitalism. New York: Verso.

- Aronson, M. F.; Lepczyk, C. A.; Evans, K. L. et al. (2017): Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15 (4), pp. 189–196.

- Arvanitis, E.; Yelland, N. J.; Kiprianos, P. (2019): Liminal spaces of temporary dwellings: Transitioning to new lives in times of crisis. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 33 (1), pp. 134–144.

- Bagaeen, S. (2006): Redeveloping former military sites: Competitiveness, urban sustainability and public participation. Cities, 23 (5), pp. 339–352.

- Banzhaf, E.; Reyes-Paecke, S.; Müller, A.; Kindler, A. (2013): Do demographic and land-use changes contrast urban and suburban dynamics? A sophisticated reflection on Santiago de Chile. Habitat International, 39, pp.179–191.

- Barkasi, A.; Dadio, S.; Losco, R.; Shuster, W. (2012): Urban soils and vacant land as stormwater resources. World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2012 – Crossing Boundaries. American Society of Civil Engineers, pp. 569–579.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009): Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9 (2), pp. 27–40.

- Breitung, W. (2011): Borders and the city: Intra-urban boundaries in Guangzhou (China). Quaestiones Geographicae, 30 (4), pp. 55–61.

- Brenner, N.; Elden, S. (2009): Henri Lefebvre on state, space, territory. International Political Sociology, 3, pp. 353–377.

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. (2014): The “urban age” in question. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (3), pp.731–755.

- Brighenti, A. M. (2013): Urban Interstices: The Aesthetics and the Politics of the In-between. Surrey, England: Ashgate.

- Burger, M.; Meijers, E. (2012): Form follows function? linking morphological and functional polycentricity. Urban Studies, 49 (5), pp.1127–1149.

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción – C.Ch.C (2012): Disponibilidad de suelo en el gran Santiago [Land availability in greater Santiago] Resultados Estudio 2012, Evolución 2007–2012.

- Catalán, J.; Fernandez, J.; Olea, J. (2013): Cultivando Historia. Trayectorias, Problemáticas y Proyecciones de los Huertos de La Pintana [Cultivating History. Trajectories, Problematics, and Projections of the Worker and Familial Orchards of La Pintana]. Santiago, Chile: Ed. Dhiyo.

- Clichevsky, N. (2007): La tierra vacante “revisitada”: elementos explicativos y potencialidades de utilización [Vacant lands revisited: explicative elements and land-use potentials]. Cuaderno urbano: espacio, cultura y sociedad, 6, pp. 195–219.

- Collier, J.; Collier, M. (1986): Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Mexico: UNM Press.

- Colsaet, A.; Laurans, Y.; Levrel, H. (2018): What drives land take and urban land expansion? A systematic review. Land Use Policy, 79, pp. 339–349.

- Coq-Huelva, D.; Asián-Chaves, R. (2019): Urban sprawl and sustainable urban policies. A review of the cases of Lima, Mexico City and Santiago de Chile. Sustainability, 11 (20), 5835.

- Cox, T.; Hurtubia, R. (2021): Subdividing the sprawl: Endogenous segmentation of housing submarkets in expansion areas of Santiago, Chile. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48 (7), pp.1770–1786.

- de la Barrera, F.; Henríquez, C.; Coulombié, F.; Dobbs, C.; Salazar, A. (2019): Periurbanization and conservation pressures over remnants of native vegetation: impact on ecosystem services for a Latin-American capital city. Change and Adaptation in Socio-Ecological Systems, 4 (1), pp. 21–32.

- de Mattos, C.; Fuentes, L.; Link, F. (2014): Tendencias recientes del crecimiento metropolitano en Santiago de Chile¿ Hacia una nueva geografía urbana? [Recent trends of metropolitan growth in Santiago de Chile]. Revista invi, 29 (81), pp.193–219.

- del Piano, A. (2010): Memoria explicativa, Ciudad Parque Bicentenario. Una nueva forma de hacer ciudad [Executive report Bicentenary Park City. A new way of making city]. Ministerio de Vivienda y urbanismo (MINVU), Chile.

- Dennis, M.; James, P. (2017): Evaluating the relative influence on population health of domestic gardens and green space along a rural-urban gradient. Landscape and Urban Planning, 157, pp. 343–351.

- Derkzen, M. L.; van Teeffelen, A. J.; Verburg, P. H. (2015): Quantifying urban ecosystem services based on high resolution data of urban green space: an assessment for Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52 (4), pp. 1020–1032.

- Dockerill, B.; Sturzaker, J. (2020): Green belts and urban containment: The Merseyside experience. Planning Perspectives, 35 (4), pp. 583–608.

- Douglas, I. (2008): Environmental change in periurban areas and human and ecosystem health. Geography Compass, 2 (4), pp.1095–1137.

- Dovey, K.; King, R. (2012): Informal urbanism and the taste for slums. Tourism Geographies, 14 (2), pp. 275–293.

- Dubeaux, S.; Sabot, E. C. (2018): Maximizing the potential of vacant spaces within shrinking cities, a German approach. Cities, 75, pp.6–11.

- Engeström, Y.; Engeström, R.; Kärkkäinen, M. (1995): Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learning and Instruction, 5 (4), pp. 261–417.

- Evans, C.; Lewis, J. (2018): Analysing Semi-Structured Interviews Using Thematic Analysis: Exploring Voluntary Civic Participation Among Adults. SAGE Publications Limited.

- Flores, M.; Otazo-Sánchez, E. M.; Galeana-Pizana, M. et al. (2017): Urban driving forces and megacity expansion threats. Study case in the Mexico City periphery. Habitat International, 64, pp. 109–122.

- Fuentes, L.; Pezoa, M. (2018): Nuevas geografías urbanas en Santiago de Chile 1992–2012. Entre la explosión y la implosión de lo metropolitan [New urban geographies in Santiago de Chile 1992-2012. Between the explosion and implosion of the metropolitan]. Revista de Geografia Norte Grande, 70, pp.131–151.

- Fuentes, L.; Mac-Clure, O.; Moya, C.; Olivos, C. (2017): Santiago de Chile¿ ciudad de ciudades? Desigualdades sociales en zonas de mercado laboral local [Santiago de Chile: towards a city of cities? Social inequalities in zones of labour market]. Revista de la CEPAL, 121, pp. 93–109.

- Gainza, X.; Livert, F. (2013): Urban form and the environmental impact of commuting in a segregated city, Santiago de Chile. Environment and Planning B, 40 (3), pp. 507–522.

- Gallent, N.; Shaw, D. (2007): Spatial planning, area action plans and the rural-urban fringe. Journal of Environmental Planning and management, 50 (5), pp. 617–638.

- Galletta, A. (2013): Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication ( = Qualitative Studies in Psychology, 18). NYU press.

- Gandy, M. (2011): Interstitial landscapes: Reflections on a Berlin corner. In Gandy, M. (ed.), Urban Constellations. Berlin: Jovis, pp.149–152.

- Gandy, M. (2013) Marginalia: Aesthetics, ecology, and urban wastelands. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103 (6), pp.1301–1316.

- Gavin, H. (2008): Thematic Analysis. In Gavin, H., Understanding Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology. SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 273–281.

- Gavrilidis, A. A.; NiȚĂ, M. R.; Onose, D. A.; Badiu, D. L.; NĂstase, I. I. (2019): Methodological framework for urban sprawl control through sustainable planning of urban green infrastructure. Ecological Indicators, 96, pp. 67–78.

- Graham, S. (2000): Constructing premium network spaces: reflections on infrastructure, networks and contemporary urban development. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24 (1), pp.183–200.

- Graham, S.; Marvin, S. (2001): Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. New York: Psychology Press.

- Hamel, P.; Keil, R. (2015): Suburban Governance. A Global View. University of Toronto Press.

- Harrison, J.; Heley, J. (2015): Governing beyond the metropolis: Placing the rural in city-region development. Urban Studies, 52 (6), pp.1113–1133.

- Hebbert, M. (1986): Urban Sprawl and Urban Planning in Japan. The Town Planning Review, 57 (2), pp. 141–158.

- Heinrichs, D.; Nuissl, H. (2015): Suburbanisation in Latin America: Towards new authoritarian modes of governance at the urban margin. In Hamel, P.; Keil, R. (eds.), Suburban Governance. A Global View. University of Toronto Press, pp. 216–238.

- Herrault, H.; Murtagh, B. (2019): Shared space in post-conflict Belfast. Space and Polity, 23 (3), pp. 251–264.

- Hidalgo Dattwyler, R.; Santana Rivas, L. D.; Link, F. (2019): New neoliberal public housing policies: Between centrality discourse and peripheralization practices in Santiago, Chile. Housing Studies, 34 (3), pp. 489–518.

- Hoover, F. A.; Hopton, M. E. (2019): Developing a framework for stormwater management: leveraging ancillary benefits from urban greenspace. Urban Ecosystems, 22 (6), pp.1139–1148.

- Hugo, J.; Du Plessis, C. (2020): A quantitative analysis of interstitial spaces to improve climate change resilience in Southern African cities. Climate and Development, 12 (7), pp. 591–599.

- Inostroza, L. (2017): Informal urban development in Latin American urban peripheries. Spatial assessment in Bogotá, Lima and Santiago de Chile. Landscape and Urban Planning, 165, pp. 267–279.

- Inostroza, L.; Baur, R.; Csaplovics, E. (2013): Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: A dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. Journal of Environmental Management, 115, pp. 87–97.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas (INE) (2017): Censo de Poblacion y Vivienda [National Institute of Statistics, INE. Statistics of population and housing]. Online: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/censos-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/poblacion-y-vivienda (accessed in June 2021).

- Iossifova, D. (2013): Searching for common ground: Urban borderlands in a world of borders and boundaries. Cities, 34, pp.1–5.

- Irwin, E.; Bockstael, N. (2007): The evolution of urban sprawl: Evidence of spatial heterogeneity and increasing land fragmentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104 (52), pp. 20672–20677.

- Johnson, C.; Baker, T.; Collins, F. L. (2019): Imaginations of post-suburbia: Suburban change and imaginative practices in Auckland, New Zealand. Urban Studies, 56 (5), pp.1042–1060.

- Jorgensen, A.; Keenan, R. (2012): Urban Wildscapes. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kamvasinou, K.; Roberts, M. (2014): Interim spaces: Vacant land, creativity and innovation in the context of uncertainty. In Mariani, M.; Barron, P. (eds.), Terrain Vague: On the Edge of the Pale. London: Routledge, pp.189–200.

- Koolhaas, R. (2021): Countryside. A report. The countryside in your pocket! Taschen.

- La Greca, P.; La Rosa, D.; Martinico, F.; Privitera, R. (2011): Agricultural and Green infrastructures: The role of non-urbanized areas for eco-sustainable planning in metropolitan region. Environmental Pollution, 159 (1), pp. 2193–2202.

- La Rosa, D.; Privitera, R. (2013): Characterization of non-urbanized areas for land-use planning of agricultural and green infrastructure in urban contexts. Landscape and Urban Planning, 109 (1), pp. 94–106.

- Lang, R. (2002): Does Portland’s urban growth boundary raise house prices? Housing policy Debate, 13 (1), pp.1–5.

- Ma, J. (2016): Green Infrastructure and Urban Liveability: Measuring Accessibility and Equity (Doctoral dissertation, ResearchSpace@Auckland).

- Ma, J.; Haarhoff, E. (2015): The GIS-based research of measurement on accessibility of green infrastructure-a case study in Auckland. In MIT CUPUM Conference Proceeding, The 14th International Conference on Computers in Urban Planning and Urban Management, July 7–10. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Maruani, T.; Amit-Cohen, I. (2007): Open space planning models: A review of approaches and methods. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81 (1) pp.1–13.

- Matthews, T.; Lo, A. Y.; Byrne, J. A. (2015): Reconceptualizing green infrastructure for climate change adaptation: Barriers to adoption and drivers for uptake by spatial planners. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, pp.155–163.

- Ministerio de Agricultura (2012): Análisis de los catastros sobre autorizaciones de cambio de uso de suelo de la región metropolitana de Santiago. Estudio de impacto de la expansión urbana sobre el sector agrícola en la región metropolitana de Santiago. [Analysis of land-use changes survey of the metropolitan región of Santiago. Study of imapct of urban expansión on agricultural lands]. Centro de Información de Recursos Naturales. Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias del Ministerio de Agricultura (ODEPA): Santiago, Chile.

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU) (2014): Towards a New Urban Policy for Chile: National Policy of Urban Development. Online: https://cndu.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/L4-PoliticaNacional-Urbana.pdf (accessed in March 2021).

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (2012): Diagnóstico de los suelos de la Región Metropolitana [Analysis of Metropolitan Region’s lands]. Servicio Nacional de Información Ambiental – SINIA. Centro de Documentación, Subsecretaría de Medio Ambiente.

- Monkkonen, P.; Comandon, A.; Escamilla, J. A. M.; Guerra, E. (2018): Urban sprawl and the growing geographic scale of segregation in Mexico, 1990–2010. Habitat International, 73, pp. 89–95.

- Morrison, N. (2010): A green belt under pressure: The case of Cambridge, England. Planning Practice & Research, 25 (2), pp. 157–181.

- Naveh, Z. (2000): What is holistic landscape ecology? A conceptual introduction. Landscape and Urban Planning, 50 (1–3), pp.7–26.

- Northam, R. (1971): Vacant land in the American city. Lands Economics, 47 (4), pp. 345–355.

- Ntihinyurwa, P.D.; de Vries, W.T.; Chigbu, U.E.; Dukwiyimpuhwe, P.A. (2019): The positive impacts of farm land fragmentation in Rwanda. Land Use Policy, 81, pp. 565–581.

- Odum, E.; Barret, G. (2006): Fundamentals of Ecology. Cengage Learning Latin America.

- Paredes, F. A.; Vásquez, F. L. (2020): Análisis multicriterio: proyección y relocalización en la comuna de La Pintana, Chile [Multi-criteria analysis: projection and relocation in the Commune La Pintana, Chile]. Forum International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2 (2), pp. 67–78.

- Phelps, N. (2015): Sequel to Suburbia. Glimpses of America’s Post-Suburban Future. USA: IT Press.

- Phelps, N. A.; Silva, C. (2018): Mind the gaps! A research agenda for urban interstices. Urban Studies, 55 (6), pp.1203–1222.

- Phelps, N.; Wood, A. (2011): The new post-suburban politics? Urban Studies, 48 (12), pp. 2591–2610.

- Rayback, S. (2016): Making observations and measurements in the field. In Clifford, N.; Cope, M.; French, S.; Gillespie, T. (eds.), Key Methods in Geography. London: Sage, pp. 325–335.

- Rigolon, A.; Németh, J. (2018): We’re not in the business of housing: Environmental gentrification and the nonprofitization of green infrastructure projects. Cities, 81, pp.71–80.

- Roberts, L. (2018): Spatial Anthropology. Excursions in Liminal Spaces. London: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

- Røe, P. G.; Saglie, I. L. (2011): Minicities in suburbia – A model for urban sustainability? FormAkademisk-forskningstidsskrift for design og designdidaktikk, 4 (2), pp. 38–58.

- Roitman, S.; Phelps, N. (2011): Do gates negate the city? Gated communities’ contribution to the urbanisation of suburbia in Pilar, Argentina. Urban Studies, 48 (16), pp. 3487–3509.

- Roubelat, L.; Armijo, G. (2012): Urban Agriculture in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago de Chile. An Environmental Instrument to Create a Sustainable Model. PLEA 2012 – 28th Conference, Opportunities, Limits & Needs Towards an environmentally responsible architecture Lima, Perú 7–9 November 2012.

- Sagaris, L.; Landon, P. (2017): Autopistas, ciudadanía y democratización: la Costanera Norte y el Acceso Sur, Santiago de Chile (1997–2007) [Motorways, citizenship, and democracy: The North Motorway and the South Access of Santiago de Chile, 1997–2007]. EURE (Santiago), 43 (128), pp.12–151.

- Santos, J. R. (2017): Discrete landscapes in metropolitan Lisbon: Open space as a planning resource in times of latency. Planning Practice & Research, 32 (1), pp. 4–28.

- Shaw, P.; Hudson, J. (2009, July): The Qualities of Informal Space: (Re)appropriation within the informal, interstitial spaces of the city. In Proceedings of the Conference Occupation Negatiations of the Constructed Space, pp.1–13.

- Sieverts, T. (2003): Cities Without Cities. An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt. London and NY: Spon Press.

- Silva, C. (2017): The infrastructural lands of urban sprawl: Planning potentials and political perils. Town Planning Review, 88 (2), pp. 233–256.

- Silva, C. (2019): Auckland’s urban sprawl, policy ambiguities and the peri-urbanisation to Pukekohe. Urban Science, 3 (1), pp.1–20.

- Silva, C. (2019): The interstitial spaces of urban sprawl: Unpacking the marginal suburban geography of Santiago de Chile. In Geraghty N.; Massidda A. (eds.), Creative Spaces: Urban Culture and Marginality in Latin America. London: University of London Press, pp. 55–84; DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvp2n322.7.

- Silva, C. (2020): The rural lands of urban sprawl: Institutional changes and suburban rurality in Santiago de Chile. Asian Geographer, 37 (2), pp. 117–144.

- Silva, C.; Vergara, F. (2021): Determinants of urban sprawl in Latin-America: Evidence from Santiago de Chile. SN Social Sciences, 202 (1), pp.1–35; DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545021-00197-4.

- Smith, P.; Romero, H. (2016): Factores explicativos de la distribución espacial de la temperatura del aire de verano en Santiago de Chile. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 63, pp. 45–62.

- Ståhle, A.; Marcus, L. (2008): Compact sprawl experiments. Four strategic densification scenarios for two modernist suburbs in Stockholm. In Stahle, A. (ed.), Compact Sprawl: Exploring Public Open Space and Contradictions in Urban Density. Published Doctoral Dissertation, KTH Architecture and the Built Environment, School of Architecture, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

- Stanley, B.W. (2014): Local property ownership, municipal policy, and sustainable urban development in Phoenix, AZ. Community Development Journal, 50 (3), pp. 510–528.

- Star, S. L.; Griesemer, J. R. (1989): Institutional ecology, translations and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19 (3), pp. 387–420.

- Stender, M. (2017): Towards an architectural anthropology – What architects can learn from anthropology and vice versa. Architectural Theory Review, 21 (1), pp. 27–43.

- Storper, M.; Scott, A. J. (2016): Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment. Urban studies, 53 (6), pp.1114–1136.

- Suazo-Vecino, G.; Muñoz, J. C.; Fuentes Arce, L. (2020): The displacement of Santiago de Chile’s downtown during 1990–2015: Travel time effects on eradicated population. Sustainability, 12 (1), p. 289.

- Talen, E. (2010): Zoning for and against sprawl: The case for form-based codes. Journal of Urban Design, 18 (2), pp.175–200.

- Tapia, R. (2011): Social housing in Santiago. Analysis of its Locational Behavior between 1980–2002. INVI, 73 (26), pp.105–131.

- Tashakkori, A.; Creswell, J.W. (2007): Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (3), pp. 207–211.

- Thomas, K.; Littlewood, S. (2010): From green belts to green infrastructure? The evolution of a new concept in the emerging soft governance of spatial strategies. Planning Practice & Research, 25 (2), pp. 203–222.

- Tonnelat, S. (2008): Out of frame. The (in) visible life of urban interstices – a case study in Charenton-le-Pont, Paris, France’. Ethnography, 9 (3), pp. 291–324.

- Trancik, R. (1986): Finding Lost Space; Theories of Urban Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; KaŹmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. (2007): Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and urban planning, 81 (3), pp.167–178.

- van der Krabben, E.; Jacobs, H. M. (2013): Public land development as a strategic tool for redevelopment: Reflections on the Dutch experience. Land Use Policy, 30 (1), pp.774–783.

- van der Wouden, R. (2020): In control of urban sprawl? Examining the effectiveness of national spatial planning in the Randstad, 1958–2018. In Zonneveld, W.; Nadin, V. (eds.), The Randstad. Routledge, pp. 281–296.

- van Houtum, H.; Van Naerssen, T. (2002): Bordering, ordering and othering. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 93 (2), pp.125–136.

- van Leeuwen, E.; Nijkamp, P. (2006): The urbanrural nexus: A study on extended urbanization and the Hinterland. Studies in Regional Science, 36(2), pp. 283–303.

- van Wee, B.; Geurs, K. (2011): Discussing equity and social exclusion in accessibility evaluations. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 11 (4); DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18757/ejtir.2011.11.4.2940.