Abstract

Starting from what the Hou Hanshu says about the Southern Man in Later Han times, this article aims to measure the prescriptive importance of Fan Ye’s text, through a comparison with other types of documents, mostly unearthed documents from the Middle Yangzi area. Beyond the stereotypical image of benevolent officials educating savage barbarians, it suggests that the “Man problem” was not an ethnic issue, but rather a political and fiscal one. Indeed, most Man rebellions occurred not only because of the gradual imperial colonization of the southern part of the realm, but also because the officials holding office in the Middle Yangzi regularly questioned the Man’s fiscal status.

本文通過⟪後漢書⟫及近五十年來長江中游地區出土文獻來考察漢代南蠻的歷史。摒除了蠻人頑劣,受循吏諄諄教導的千篇一律形象,筆者認為“南蠻問題”并不是民族問題,而是政治和財政上的難題。事實上儘管在帝國南部的長江中游地區逐步殖民化進程中發生了許多南蠻叛亂,其主要原因還是當地任職官員對南蠻的財政及經濟身份經常有所質疑。

Introduction

During the first millennium of the Chinese empire, the Southern Man (Nan Man 南蠻) people remained a constant threat to the political stability of Southern China, as their territory was not really controlled by the imperial armies. However, and contrary to modern common assumptions,Footnote1 standard histories did not portray them as “barbarians,” ethnically different from the other subjects of the empire. More precisely, the Southern Man people (hereafter Man) who were geographically incorporated into the Chinese ecumene were treated differently from the commoners, or min 民, i.e., the subjects of the empire who were neither soldiers nor officials, but this different treatment was not grounded on ethnicity.

In order to assess who the Man were, where they lived, and how they were represented and integrated, I suggest in this article that the issue of the Man people should be mainly addressed as a political and fiscal problem rather than an ethnic one. To do this, I will focus throughout this article on Fan Ye’s Hou Hanshu (History of the Later Han), which contains the earliest substantial description of the Man people.Footnote2 In order to provide a comprehensive image of the way the Man were perceived in Han times, this article also contrasts this transmitted account with some of the recently unearthed manuscripts from wells and tombs of the Middle Yangzi area, namely Liye 里耶 (Hunan), Zhangjiashan 張家山 (Hubei) and Dongpailou 東牌樓 (Hunan). Above all, I argue for a need to rethink the nature of the relationship between the empire and the Man, in line with that recounted in the original sources and documents. By moving away from moral and ethnic preoccupations and concentrating instead on a pragmatic approach to administrative and social issues, the officials’ strategies are exposed as quite clearly aiming to optimize the land’s human and natural resources. This reveals the regional story of governmental control of social unrest used for taxation gain and efficiency.

First, I will briefly explain why we should put aside the question of ethnicity, or why it is currently a problem for modern historians, and why it should not be viewed as a problem for the Man people living within the ecumene in Han times. There is a wealth of important scholarship on the question of ethnicity in premodern China,Footnote3 however, I assert that “ethnicity” is not an operating concept here, first of all because it is an anachronism. The sources describing the Man of the Middle Yangzi do not portray them as ethnically distinct from other imperial subjects. Reflecting on this matter, Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書 (1910–1998) convincingly dismissed any differentiation based upon ethnic criteria (zulei zhi shu 族類之殊), insisting instead on an ethical kind of differentiation (lijiao zhi bian 禮教之辨).Footnote4 Rather than using ethnic markers to describe various groups of people, like the Man, who lived within the borders of the realm, it certainly appears more productive to consider “imperial” subjects (including commoners, officials and the military) in comparison to “hill people” (i.e., the Man), who were described in relation to their geographical setting.

In the Hou Hanshu, a chapter such as the one dedicated to the Southern Man (“Nan Man liezhuan” 南蠻列傳, juan 86) is relevant, for it demonstrates the themes of interest for any official regarding his next post: such as, what he should know about the local people and landscape, and how he should behave. In addition, the numerous examples of previous exemplary officials provide extremely useful information to help an official deal with a territory he is not familiar with. Ethnic considerations appear irrelevant in this context, since an analysis of the political, fiscal and social interactions between roughly identifiable groups – i.e., the Man and the benevolent officials (xunli 循吏) –, is the key to understanding the social and political climate of the period through the perception and representation of the Man people in Chinese historiography.

Drawing from both an officially transmitted source (the Hou Hanshu) and administrative documents excavated in the Middle Yangzi area, the first part of this article will focus on retracing the Man’s geographical setting and their uprisings, as well as on a political and fiscal account of the Man people. The second part will examine a few biographical accounts taken from the “benevolent officials” biographical section of the Hou Hanshu (juan 76), for those officials were intended to be the conduits of “Confucianization” in the South, civilizing agents who were meant to teach the Man people the proper rites.

Savage Barbarians? The Southern Man as a Political and Fiscal Problem

The Southern Man and the Middle Yangzi: Topography and Rebellions

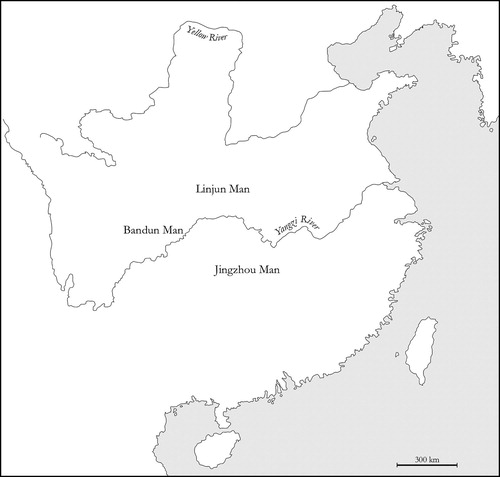

Depending on the historical context, “Southern Man” or “Man” can refer to different types of people, which I have separated into two distinct groups, based on the way they are treated by historiography. The first were the “outer Man,” who lived beyond the southern borders of the empire, and the second were the “inner Man,” who lived within the empire’s borders. The Hou Hanshu distinguishes between these two groups, according to their distance from the imperial centre: the author first addresses the inner Man, and then, moving away from the realm, the outer Man. The present article only discusses the inner Man. The inner Man were further separated into three different subgroups according to Fan Ye, who followed three distinct Man lineages. They were, in order of importance: the Jingzhou 荊州 Man, otherwise called Man from Wuling 武陵 and Changsha 長沙 (ancestor: Panhu 槃瓠; see below), the Linjun 廩君 Man (ancestor: Lord Lin 廩), who were the northernmost Man, scattered around the commanderies of Ba 巴 and Nan 南, and the Bandun 板楯 Man (ancestor: Wuxiang 務相), in present-day Sichuan (see ).

There were two key moments in the history of the Man, as told by imperial sources: first, encounters with the Man people during the Eastern Han’s progressive conquest of the South, mostly during the first two centuries CE, and probably earlier; officials were expected to describe the people’s physical characteristics, as well as their origin myths, and their social behaviour. There was a gradual evolution during the Six Dynasties (220–589), with an alternation of pacification, rebellions, taxation, intermixing and eventual absorption of the Man into the population of the realm. Indeed, Fan Ye’s account is more of a constructed narrative than simple and random notes: he provides us with the story of Panhu, a dog-man who killed a general and enemy of the sovereign Gao Xin 高辛, who had promised his daughter’s hand in marriage to anyone who could slay the general. Directly following the account of Panhu’s success, more interestingly than the origin myth, the following passage gives us information about the environment of the Man:

Panhu took the [monarch’s] daughter, he carried her on his back and he fled to Mount Nan.Footnote5 He stopped in a stone grotto. This place was dangerous and difficult to access. No traces of humans had ever reached it. Then, the daughter of the monarch undressed, tied her hair in a “dog-style” bun, and put on the clothes that she had made herself. Since the monarch was sad and suffered from the separation, he sent emissaries to look for [her]. They encountered rain, winds, thunder, and darkness, and were not able to penetrate further [ … ]. [The Man] enjoy living in the valleys between mountains and do not like flat expanses.Footnote6

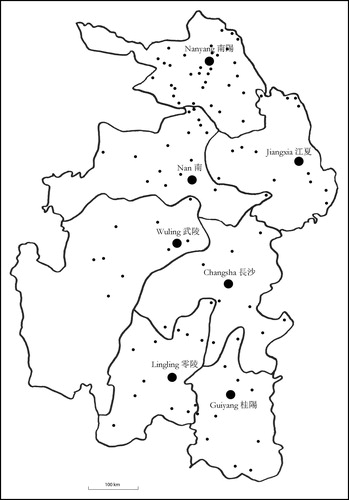

Although Man uprisings occurred throughout the Eastern Han dynasty, a geography of conflicts in Jing 荊 province shows that during the second half of the second century, most Man rebellions happened in the province’s four southernmost commanderies, the “Jingnan” 荊南,Footnote8 comprising Wuling (in 151, 160, 186), Lingling (160), Guiyang (160), and Changsha (157, 160). (For a map of Jing province, see .) This period followed the imperial colonization of the South, and was a time when the dynasty’s political power was weakening. Yet, hilly and dangerous Wuling stood out for its tumultuous history: given the Man people’s ability to cut off roads and rivers, the main rebellions (in 47–48, 76, 78, 80, 92, 115, 116, 136, 137, 151, 160, 186) of the first two centuries CE confirm that they had a topographical superiority and that the Wuling commandery was a very dangerous area for the imperial troops.Footnote9 For more than 150 years, Wuling was never really under official control. Indeed, the 47–48 conflicts must have had a lasting impact on the imperial power, as it sent fewer soldiers to engage in the subsequent battles that spanned for another hundred years. The Man, whose guerrilla-style warfare, which was particularly well adapted to the landscape south of the Middle Yangzi, had indeed a clear advantage over heavily-armed troops. Still, the imperial troops’ progress must have been smoother on the plains, and one should not forget that most local rebellions were probably not considered important enough to be recorded.

Why did these numerous and apparently sudden outbursts of violence occur? One obvious reason was the massive relocation of commoners in the Middle Yangzi area, the most important social and demographic factor of the first two centuries CE as shown in the dramatic increase in the registered population between the censuses of 2 CE and 140 CE.Footnote10 However, this is not the only possible explanation, as the Man lived in hills and mountainous areas and would generally leave the plains to the commoners. The next section addresses an often-overlooked aspect of this question, the fiscal control of the Man people.

Taxing the Southern Man in Order to Control Them

Closely related to the Man’s origin myth, the following lines show the basis of the Man’s “myth” of fiscal privilege:

In light of the previous achievements of their ancestor [Panhu] and given the fact that their ancestress was the daughter of a monarch, [the Man] live off their farming production which they can [freely] trade, and are not required to present a pass when crossing passes and bridges, nor to pay any land tax.Footnote11

Fragments addressing the fiscal status of the Man can be found in the documents recently excavated from well J1 at Liye (Hunan) in 2002. Although their exact meanings are still being debated among specialists because of a lack of ample contextual evidence, the following examples give us an insight into the fiscal situation of the local Man population. As early as 213 BC (and thus probably earlier as well), the Man were required to pay “a four zhang and seven chi [long piece of] jia,”Footnote13 the jia referring to the name of a tax made of cloth. Moreover, we read that:

Zi, acting magistrate of Qianling [county], dares to say: “[This] is the corvée [to be paid by] Wu Man from a hamlet on the road to Qianling [county].”Footnote14

Some twenty years after the Liye events, 450 km northeast, in Nan commandery, the documents excavated in 1983–1984 from tomb M247 at Zhangjiashan (Hubei) record among other legal processes a judicial case that occurred in 196 BC. A Man deserter (ironically) named Wu You 毋憂 was denounced and summoned to the garrison to explain his behavior:

Wu You said: “[I am a] Man adult male. Every year, fifty-six cash is paid as corvée service. I do not have to be made a garrison [conscript]. Commandant Yao sent me to become a garrison [conscript]. I was on my way [to my post] but had not yet arrived when I left and absconded. The rest is as [Bailiff of the Crossbowmen] Jiu [said].” Yao said: “There is an ordinance governing the commandant of Nan commandery sending out garrison [conscripts], and the ‘Statutes on the Manyi’ does not say ‘do not order them to be garrison [conscripts]’; thus, I sent him [to his post]. I do not know the reason for his absconding. Everything else is as Wu You [has said].” Wu You was cross-examined: “[According to] the statute, ‘Man males are to remit their annual cong in cash in order to be redeemed from the corvée.’ It does not say that [the Man] should not be ordered to be garrison [conscripts]. In addition, even though it was not fitting that you be made a garrison [conscript], Yao had already sent you out, and thus, you became a garrison conscript. Then, shortly afterward, you left and absconded. How do you explain [this]?” Wu You said: “We have a chieftain who every year remits the cong in cash in order to redeem us from the corvée. Therefore, we are exempt.”Footnote16

Overall, the fact that such information was found in administrative documents from 213 and 196 BC is evidence that “Man-oriented” taxes were in place and were a rather common practice under the Qin and Western Han regimes, and that they probably predated imperial unification. In creating a specific income tax for the Man people, by registering and conscripting them, the goal of such a regional policy was obviously to control the Man and eventually to prevent them from rebelling: as the Hou Hanshu chronicle recounts, this was the main problem posed by the Man for nearly two centuries.

An overly simplistic presentation linking the origins of the Man’s rebellions to their bellicose nature is clearly unsatisfactory, while questions related to whether they were obliged to pay taxes or not seem historically more convincing. In fact, and in apparent contradiction to the previous extract relating to a form of fiscal privilege taken from the Hou Hanshu (quoted above), Fan Ye mentions that the Man had to pay a specific tax, the cong, describing its materiality:

Each year, the Man had to pay an entire piece of cloth for each adult, and a piece two zhang long for each child. This is what is called congbu.Footnote18

To put it in a nutshell, peace was attainable as long as the Man were left alone in the hills of the Middle Yangzi and as long as they kept paying the specific tax that was required from them. Why then did rebellions continue to break out during the Eastern Han? Fan Ye’s account in fact reveals that most outbursts in and around Jing province were a consequence of amendments to taxation concerning the Man. They occurred when drafts and requisitions were considered harsh, arbitrary or unnecessary, or when the Man people’s tax level was adjusted to meet that of the commoners, the very same commoners who also rebelled when they felt they were being treated less favourably than the Man.

A telling example involves the governor of Wuling who proposed increasing taxation of the Man in 136, stating that they had submitted to the empire for a long time and were as obedient as the commoners. Emperor Shun accepted the proposal. Alarmed at the potential consequences, a clear-sighted official named Yu Xu 虞詡 submitted the following memoir to the throne:

“From ancient times, the sage kings did not consider those of different customs their subjects. It was not that their virtue was not able to reach them or that their military authority did not affect them; it was because they had the hearts of wild animals and were full of greed. Thus, they would bridle them in order to soothe them. When they attached themselves [the sage kings] would receive them without going to meet them. When they rebelled, they would take this seriously without trying to pursue them. According to the old statutes of the previous emperors, the amount of the payment that they had to provide has been in place for a long time. If we suddenly decide to increase its amount today, we will face resentment and uprising. What we would gain would not compensate for what we would lose, and then we would regret it for sure.” The emperor did not follow [his recommendations].Footnote21

The previous quotation contains the sequence of an unsuccessful interaction between the government and the Man. First, it is asserted that the apparent calmness of the Man justifies an increase in taxation; second, a virtuous official warns the emperor of the potential risks; third, the increase is implemented, and the uprisings start. The exemplary lesson of these lines is that the Man considered the government had broken an agreement whenever it tried to tax the Man unduly. Most times, fiscal pressure and unequal treatment were indeed the reasons why the Man rebelled.

Lastly, let us turn to a document excavated from well J7 at Dongpailou (Hunan) in 2004. It refers to events that took place in Changsha commandery in the final years of the 180s.Footnote23 It is extremely valuable for various reasons: it was written when the region of Changsha was still under threat from the Man and, as such, it documents the judicial reality in an area heavily populated with Man people; it furthermore links the social unrest caused by the Man to their taxation:

Chen Su, acting magistrate of Linxiang [county], respectfully reports: “The south of Jing [province] is frequently under the assault from armed bandits. The commoners have ceased paying their legally required taxes. They hope to receive an act of amnesty in order to be exempted from paying taxes. After consecutive years with no [tax] payments, the granaries are empty of rice, and storehouses are empty of cash and cloth. However, the village officials who are responsible for collecting the taxes are still making an effort [to collect the taxes]. Therefore, if there is an act of amnesty, a [tax] exemption should not be included. Zhaoling and Liandao [counties] still have ying governors stationed there. Should they encounter disturbances, the officials on duty will return to their homes. They will not respond to calls to order, and they will store their crossbows and abandon their arrows.”Footnote24

Although the Dongpailou document does not explain why the Man rebelled, the mention of local officials abandoning their posts emphasizes their role (whether positive or not) in the management of the Man problem, as the next section will show.

Ritual Agents? The Role of the Benevolent Officials

The first part of this article has revealed that officials could hold conflicting views regarding Man affairs: some were inclined to leniency (as they were probably aware of the devastating consequences of the Man raids), some absconded when threatened, while others treated the Man severely, regardless of the specific (and sometimes explosive) context. Through reading biographical accounts from the Hou Hanshu, one can clearly see Fan Ye’s main idea, that a military response was not the solution to ensure long-term peace with a given group of people. He believed that generals and troops were important and should often be sent as an immediate response when trouble arose, but that no form of peace could last in such conditions. He thought that the only sustainable option involved the paramount role of benevolent officials, as they were the only potential peacemakers.

How then did these officials enforce peaceful relations with the Man? To explain this phenomenon, Miyakawa Hisayuki has written about the “Confucianization of South China.”Footnote25 Indeed, the capacity to conform oneself and others to certain rites was what determined effective integration into Chinese society. Thus, in the context of early and early medieval China, imperial subjects were differentiated from the Man, or hill people, through a set of values that were determined by customs, feng 風 (“wind”) and su 俗 (“mores”) at the commoners’ level, and by the respect of li 禮 (“rites”) – or the absence of it – among the elite. As some of the next examples will demonstrate, the benevolent officials’ actions might appear dual: their goals as governmental agents were to ensure peace, to modify local customs and teach local people the proper rites, but also to correct those officials who had gone rogue.

The Structure of the Hou Hanshu’s Chapter Dedicated to the Benevolent Officials

There are nine chapters of collective biographies in the Hou Hanshu, the first of which is dedicated to the benevolent officials, which immediately highlights their importance in Fan Ye’s mind.Footnote26 Arranged chronologically, the following table records their social backgrounds, the places where they held office, and the reasons why they were included in the “benevolent” section.

TABLE OF THE HOU HANSHU’S BENEVOLENT OFFICIALS

Their goal, as their biographies show, consisted of changing the customs wherever they went and improving local people through their own positive example. What is more, the benevolent officials were usually sent to dangerous or unassimilated territory precisely because they were upright and morally flawless.Footnote27 Whether they came from a poor background or not, the benevolent officials usually showed a commitment to their studies, coupled with a humble attitude. But what mattered to Fan Ye was their ability to improve the inhabitants’ lives, by bringing in new technology and morals, as well as through their honest administration and fair allocation of resources.

As the map below illustrates (see ), seven out of a total of twelve benevolent officials were sent south of the Huai river, in areas traditionally inhabited by Man people, while five benevolent officials upheld the law in the North. This article now focuses on three officials (in chronological order, Wei Li 衛颯, Xu Jing 許荊, and Liu Chong 劉寵) sent to areas densely populated by Man people, in order to see if we can gain a different perspective on them from that given in the Hou Hanshu’s chapter on the Southern Man.

Benevolent Officials in Man Territory

The first biography in the Hou Hanshu is dedicated to Wei Li (fl. 26–49), who held office in Guiyang commandery. It is concerned with the troubled context of the end of the 40s, when the Man controlled neighbouring Wuling:

The people lived deep in the mountains, nearby valley torrents. They were used to their old customs, and they never paid farming taxes. Among those who dwelt far from the seat of the commandery, some were almost a thousand li away. When the local officials needed to perform their duty [and collect taxes], they would always use the people’s boats to reach them, and this was called “transportation corvée.” Whenever an official set out, forced labour would affect several families, and the commoners suffered from it. Thus Wei Li pierced through the mountain and created a road of more than five hundred li, and he established a series of inns and post houses along the road. Then forced labour diminished, and the illegal activities of the selfish officials were put to an end. The people who had been scattered slowly returned and formed settlements and villages, and they ended up paying land taxes, just like commoners.Footnote28

Approximately fifty years later, in the same commandery, the case involving Xu Jing (fl. 100) represents a more “traditional” type of biography:

Under emperor He, Xu Jing progressively rose to the position of governor of Guiyang. The commandery was at the border of the Far South. The customs of the people were frivolous and they had no understanding of classical learning and righteousness. Xu Jing implemented a proper system for funerals and marriages, and he taught them the proper rites and prohibitions. […] Xu Jing stayed in office as governor for twelve years and the elders praised him with songs. He asked to retire because he was ill, but he was named Counsellor Censor to the Emperor (at the capital) and died in office. The people of Guiyang erected a temple and a stele [to honour him].Footnote29

Moving eastwards and into the final decades of the Eastern Han, one last example shows Liu Chong’s (fl. end of 2nd c.) exemplary administration of the “hill people” (i.e., the Man, and another example of the polysemy of min). The sharp contrast between the rusticated lives of the Man and the overly complicated and thus potentially corrupt attitude of the crooked officials introduces the vivid sequence of Liu Chong improving the local laws, being summoned to the court, witnessing a few elders manifesting their sorrow and gratitude, and … the continuous barking of dogs:

The hill people were so simple and honest that they would grow old without having been once to the town market. They would get a lot of trouble from the local officials. Liu Chong reduced and suppressed the severe and complicated laws, and examined illicit actions: this brought great improvements within the commandery. When he was summoned to the court to take the position of Imperial architect, a few elders from the county of Shanyin with salt-and-pepper eyebrows and white hair came out of the Ruoxie valley. Each wanted to offer a hundred cash to Liu Chong. Acknowledging their efforts, Liu Chong said: “Honourable elders, what did you trouble yourselves for?” They replied: “We, humble people from the valley, hardly see the governor. Previous governors would regularly send their clerks among the people to take something from them, it would not stop from dawn till dusk, and sometimes during entire nights the dogs would not stop barking, the people would not be able to rest. Since your honour has taken up his position, dogs do not bark at night any longer, and the people do not see any official any more. We old folks have encountered a holy and bright person; now we hear that you will be abandoning us, thus we have come to offer you this present.” Liu Chong said: “The quality of my administrative work does not match your words. You should not have troubled yourselves to come.” And he chose to accept only one cash from each of them.Footnote30

Conclusion

Interestingly enough, the situation depicted in the Hou Hanshu (especially that of the last decades of the Eastern Han) echoes to a certain extent the author’s own times, i.e., the fifth century. Even then, the empire found the Middle Yangzi area extremely hard to control, and the Man difficult to tame.Footnote31 Similar patterns (alternating periods of peace and unrest, actual control of large areas by the Man for a long period of time) show that the lessons of the past may not have been completely learnt by fifth century local officials, or at the very least by officials sent to the Middle Yangzi area, as evidenced by factors such as the poor choice of governing officials, their personal greed and disdain for the special status claimed by the Man, and the growing population of commoners from Eastern Jin times. Moreover, the garrisons of the Middle Yangzi were composed of violent and illiterate people, which probably did not help much in pacifying the area.Footnote32 In the end, Fan Ye’s take on the Man gives way to a double paradox: how can you write about unity whilst living in times of disunity, and how can you write about an area’s history and people when it is not really officially integrated into the empire?

Fan Ye’s notes can be taken as a first attempt at presenting solutions to assimilate the Man. From an ethical point of view, he used the term “barbarian” to mean someone who was not civilized, i.e., who did not know the imperial rites, and thus remained at the bottom of the social hierarchy, defined by ritual. In fact, the Man did not appear to be barbarians (in the sense that has been attributed to non-Chinese polities like the Xiongnu 匈奴),Footnote33 as they did not invade lands that were not theirs, they did not pay a tribute,Footnote34 and their origin myths should not be understood as reflecting their contemporary situation in relation to the empire. Rather, they comprised various social groups defined by their locality, hill people that were frequently invaded.

A remaining problem is taxonomy, as the Man were not always referred to as “Man.” Indeed, they were called other names, such as “hill people” (shanmin 山民), which we find especially in the Sanguo zhi 三國志. Moreover, it is not always clear who the min might be: commoners when contrasted with the Man, “people,” but also “Man.” In such a historiographical context, it does make sense to refer to them as regional groups that were identified mainly in relation to their control of the local topography, and who were simply given a generic demonym to differentiate them from commoners living on the plains. To cut a long story short, in departing from a Man–Hua 華 (or Huaxia 華夏) dichotomy, I argue for a distinction between people from the plains and people from the hills, between regular taxpayers and fiscally privileged ones. In this context, ethnic criteria are irrelevant.

Ultimately, Fan Ye shows nuances in his account of the Southern Man, and does not hesitate to pinpoint the failures of local officials and their responsibilities in some of the uprisings. However, in his chapter on the benevolent officials, the anecdotes bring contrasting impressions to the fore: they authenticate the reality of good government through tangible examples of moral uprightness, while providing the reader with stereotypical examples of this righteousness. Periods of peace are depicted as corresponding to times when good governors ruled; those who would attract the Man on the plains, would give them land, tools, seeds, and more importantly, would teach them agricultural techniques and Confucian rites. The main point of these actions was of course to civilize the people but, beyond this obvious assessment, it also aimed to subdue them in order to stop ongoing conflicts, and to turn them into taxable subjects who would contribute financially to the local government.

Notes on Contributor

Alexis Lycas is a postdoctoral fellow in Department III of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin. His research examines the production of geographical knowledge (broadly defined) during the first millennium of the Chinese empire. He recently published “La mort par noyade dans la littérature géographique du haut Moyen Âge chinois,” Études chinoises 36 (2017) 1, pp. 51–77.

Notes

1 Notable studies on the Man incluCitationde Wylie 1882; CitationLiu Chungshee Hsien 1932; Jin CitationBaoxiang 1936; CitationTan Qixiang 1987, pp. 300−360; CitationHe Guangque 1988; CitationWhite 1991, pp. 140−160; CitationBai Cuiqin 1996, pp. 422−430; CitationLu Xiqi 2008; CitationWang Wan-chun 2009.

2 Although both the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian) and the Hanshu (History of the Han) mention or refer to the Man on several occasions, they do not devote an entire chapter to the Southern Man. The Hou Hanshu is thus the earliest standard history to do so.

3 For Early China, see studies by CitationMaspero 1927; CitationSchafer 1954; CitationYü Ying-shih 1967; CitationWang Ming-ke 1992; CitationPines 2005; CitationDi Cosmo 2010; CitationChin 2012; CitationNylan 2012; CitationBrindley 2015; CitationGoldin 2015; CitationLi 2017; CitationPines 2018. CitationHolcombe 1997−1998; CitationAbramson 2007; CitationYang Lu 2014; CitationChurchman 2016; CitationClark 2016; CitationTackett 2017 and CitationYang Shao-yun (forthcoming) have addressed those issues in relation to the Tang−Song period. For late imperial times, see CitationLombard-Salmon 1972 and CitationFiskesjö 1999.

4 CitationQian Zhongshu 1979, p. 1488. Similarly, CitationChittick 2009 (p. 65) recently proposed decreasing the importance given to ethnicity in the context of early medieval China.

5 Mount Wu 武, in the hilly regions of western Hunan. See Taiping yulan 49.368−1; CitationLiu Chungshee Hsien 1932, p. 366.

6 HHS 86.2829: 槃瓠得女,負而走入南山,止石室中。所處險絕,人跡不至。於是女解去衣裳,為僕鑒之結,著獨力之衣。帝悲思之,遣使尋求,輒遇風雨震晦,使者不得進。[ … ] 好入山壑,不樂平曠。

7 Such a form of environmental determinism can be found in most early Chinese geographical accounts (see for instance the “Yugong” 禹貢 and Shanhai jing 山海經).

8 As for the other inner Man, we have rebellions among the Linjun Man in 47 and 101 in Nan 南, then in 169 and 180 in Jiangxia 江夏. For the Bandun Man, we have rebellions in 147, 179 and 188.

9 See HHS 86.2831−2832; Citationde Crespigny 1990, pp. 8−9.

10 Wei CitationDongchao 2003, p. 64.

11 HHS 86.2829−2830: 以先父有功,母帝之女,田作賈販,無關梁符傳,租稅之賦。

12 HHS 86.2841 explains jia 幏 as a form of tax paid in Ba. Evidence from the unearthed Cang Jie pian 蒼頡篇 does not depict the Man having to pay the cong (戎翟給賨兼百越貢織), but does show the Rong 戎 and Di 翟 doing this (see Beijing daxue cang Xi Han zhushu yi, slips #8 and #9). Thanks to Christopher Foster for pointing me to this reference.

13 Liye Qin jiandu jiaoshi, vol. 1, p. 3 (J1:8−998): 幏布四丈七尺。

14 Liye Qin jiandu jiaoshi, vol. 1, p. 328 (J1:8−1449+8−1484): 遷陵守丞玆敢言之:遷陵道里毋蠻更者. See also CitationLiu Jialing 2013, pp. 104−106. It should be noted that the meaning of daoli 道里 (“hamlets on the road,” or “road distance”) is not entirely clear. I would like to thank Olivier Venture for his very helpful comments on this part.

15 Liye fajue baogao, p. 203 (board K27): 南陽戶人荊不更蠻強. Although one could read this as “people from Jing are exempted and the Man are forced,” or that “Qiang, a Man from Jing, exempted … ,” I follow Olivier Venture’s understanding: see CitationVenture 2011, p. 86. Note also that bugeng 不更 is a Qin rank (translated as “Service Rotation Exempt” in CitationBarbieri-Low – Yates 2015, p. xxii), but I use it here in the local context and in relation to the previous quotation.

16 Zhangjiashan Han mu zhujian: 247 haomu, p. 213: 毋憂曰:變(蠻)夷大男子,歲出五十六錢以當䌛(徭)賦,不當爲屯,尉窯遣毋憂爲屯,行未到,厺(去)亾(亡)。它如九。窯曰:南郡尉發屯有令,變(蠻)夷律不曰勿令爲屯,卽遣㞢(之),不𥏼(智-知)亾(亡)故,它如毋憂。詰毋憂:律變(蠻)夷男子歲出賨錢,以當䌛(徭)賦,非曰勿令爲屯也,及雖不當爲屯,窯巳(已)遣,毋憂卽屯卒,巳(已)厺(去)亾(亡),何解?毋憂曰:有君長,歲出賨錢,以當䌛(徭)賦,卽復也. For a meticulous study and full translation of this text, see CitationBarbieri-Low – Yates 2015, pp. 1171−1183. See also CitationWang Wan-chun 2009, pp. 129−132, and CitationKorolkov 2011, pp. 51−55. My translation is based on Barbieri-Low – Yates and Korolkov, with minor changes.

17 CitationBarbieri-Low – Yates 2015, pp. 79−80. See also CitationZeng – Wang 2004.

18 HHS 86.2831: 歲令大人輸布一匹,小口二丈,是謂賨布。

19 Huayang guo zhi jiaobu tuzhi, 1.14; CitationWang Zhongqian 2003, pp. 187−189.

20 See Shuowen jiezi, 6b.131. CitationWylie 1882, p. 203 translates it as “Guest cloth.”

21 HHS 86.2833: 「自古聖王不臣異俗,非德不能及,威不能加,知其獸心貪婪,難率以禮。是故羇縻而綏撫之,附則受而不逆,叛則篤而不追。先帝舊典,貢稅多少,所由來久矣。今猥增之,必有怨叛。計其所得,不償所費,必有後悔。」帝不從。

22 HHS 86.2833.

23 Wang CitationSu 2005, p. 72.

24 Changsha Dongpailou Dong Han jiandu, pp. 77−78: 臨湘守令臣肅上言:荊南頻遇軍寇,租茤法賦,民不輸入,冀蒙赦令,云當虧除。連年長逋, 倉空無米,庫無錢布。督課鄉吏如舊。故自今雖有赦令,不宜復除。昭陵,連道尚有營守,小頍驚急,見職吏各便歸家,召喚不可復致,![]() 弩委矢. Although based on CitationYang Lu 2014, p. 102, my translation differs in several aspects. See also Wang CitationSu 2005, p. 71.

弩委矢. Although based on CitationYang Lu 2014, p. 102, my translation differs in several aspects. See also Wang CitationSu 2005, p. 71.

26 HHS 76.2457−2486.

27 The same could be said about military men: only seasoned generals were sent to Man territory. However, there are no conclusive patterns in terms of the civil officials’ geographical and social origins. For a list of Han governors and inspectors, see Yan CitationGengwang 2007.

28 HHS 76.2459: 民居深山,濱溪谷,習其風土,不出田租。去郡遠者,或且千里。吏事往來,輒發民乘船,名曰「傳役」。每一吏出,傜及數家,百姓苦之。颯乃鑿山通道五百餘里,列亭傳,置郵驛。於是役省勞息,姦吏杜絕。流民稍還,漸成聚邑,使輸租賦,同之平民。

29 HHS 76.2472: 和帝時,稍遷桂陽太守。郡濱南州,風俗脆薄,不識學義。荊為設喪紀婚姻制度,使知禮禁。[ … ] 在事十二年,父老稱歌。以病自上,徵拜諫議大夫,卒於官。桂陽人為立廟樹碑。

30 HHS 76.2478: 山民愿朴,乃有白首不入市井者,頗為官吏所擾。寵簡除煩苛,禁察非法,郡中大化。徵為將作大匠。山陰縣有五六老叟,尨眉皓髮,自若邪山谷閒出,人齎百錢以送寵。寵勞之曰:「父老何自苦?」對曰:「山谷鄙生,未嘗識郡朝。它守時吏發求民閒,至夜不絕,或狗吠竟夕,民不得安。自明府下車以來,狗不夜吠,民不見吏。年老遭值聖明,今聞當見棄去,故自扶奉送。」寵曰:「吾政何能及公言邪?勤苦父老!」為人選一大錢受之。

31 Wang CitationGungwu 1973, p. 194.

32 CitationChittick 2009, p. 51.

33 In doing so, I follow Yuri Pines’s recent conclusions regarding the so-called otherness of the earlier Chu culture: using local excavated manuscripts, he has demonstrated that “Chu was not a ‘barbarian entity’ attracted by the glory of the Zhou culture as hinted in the Mengzi, but a normative Zhou polity that developed cultural assertiveness in tandem with the increase in its political power” (CitationPines 2018, p. 5).

34 Without trying to define what the complex notion of “tribute” (gong 貢) might have entailed in different political and social situations, let us remark here that the distinction between the Man who are required to pay specific taxes (the “inner Man”) and those who belong to an ad hoc form of “tributary system” (the “outer Man”), is chiefly based upon geographical criteria. For an up-to-date and challenging view on tribute in early imperial China, see CitationSelbitschka 2015.

Bibliography

Primary Sources and Unearthed Documents

- Beijing daxue cang Xi Han zhushu yi 北京大學藏西漢竹書壹. Ed. Beijing daxue chutu wenxian yanjiusuo 北京大學出土文獻研究所. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2015.

- Changsha Dongpailou Dong Han jiandu 長沙東牌樓東漢簡牘. Ed. Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 長沙市文物考古研究所. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2006.

- Huayang guo zhi jiaobu tuzhu 華陽國志校補圖注. Chang Qu 常璩 (author, fl. mid-fourth c.). Ren Naiqiang 任乃強 (editor). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1987 (2011).

- Liye Qin jiandu jiaoshi 里耶秦簡簡牘校釋, vol. 1. Chen Wei 陳偉 (editor). Wuhan: Wuhan daxue chubanshe, 2012.

- Liye fajue baogao 里耶發发掘报告. Ed. Hunan sheng wenwu kaogusuo 湖南省文物考古所. Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 2007.

- Shuowen jiezi zhu 說文解字注. Xu Shen 許慎 (author, ca. 58 – ca. 147). Duan Yucai 段玉裁 (editor, 1735–1815). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1981 (1996).

- Taiping yulan 太平御覽. Li Fang 李昉 (compiler, 925–996). Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan, 1997.

- Zhangjiashan Han mu zhujian: 247 hao mu 張家山漢墓竹簡―二四七號墓. Ed. Zhangjiashan ersiqihao Han mu zhujian zhengli xiaozu 張家山二四七號漢墓竹簡整理小組. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2001.

Secondary Sources

- Abramson, Marc. 2007. Ethnic Identity in Tang China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bai Cuiqin 白翠琴. 1996. Wei Jin Nanbeichao minzu shi 魏晋南北朝民族史. Chengdu: Sichuan minzu chubanshe.

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony – Robin Yates. 2015. Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China: A Study with Critical Edition and Translation of the Legal Texts from Zhangjiashan Tomb no. 247. Leiden – Boston: Brill.

- Brindley, Erica. 2015. Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identity on the Southern Frontier c. 400 BCE–50 CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chin, Tamara. 2012. “Antiquarian as Ethnographer: Han Ethnicity in Early China Studies.” In: Thomas Mullaney et al. (eds.), Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 128–146.

- Chittick, Andrew. 2009. Patronage and Community in Medieval China: The Xiangyang Garrison 400–600 CE. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Churchman, Catherine. 2016. The People between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of the Bronze Drum Culture 200–750 CE. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Clark, Hugh. 2016. The Sinitic Encounter in Southeast China through the First Millennium CE. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. 1990. Generals of the South: The Foundation and Early History of the Three Kingdoms State of Wu. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. 2010. “Ethnography of the Nomads and ‘Barbarian’ History in Han China.” In: Lin Foxhall (ed.), Intentional History: Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart: Steiner, pp. 299–325.

- Fiskesjö, Magnus. 1999. “On the ‘Raw’ and the ‘Cooked’ Barbarians of Imperial China.” Inner Asia 1 (1999), pp. 139–168. doi: 10.1163/146481799793648004

- Goldin, Paul R. 2015. “Representations of Regional Diversity during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty.” In: Yuri Pines – Paul R. Goldin – Martin Kern (eds.), Ideology of Power and Power of Ideology in Early China. Leiden – Boston: Brill, pp. 31–48.

- He Guangyue 何光岳. 1988 (1992). Nan Man yuanliu shi 南蛮源流史. Nanchang: Jiangxi jiaoyu chubanshe.

- Holcombe, Charles. 1997–1998. “Early Imperial China’s Deep South: The Viet Regions through Tang Times.” T’ang Studies 15–16 (1997–1998), pp. 125–156. doi: 10.1179/073750397787772740

- Jin Baoxiang 金寶祥. 1936. “Han mo zhi Nanbeichao nanfang Manyi de qianxi” 漢末至南北朝南方蠻夷的遷徙. Yu gong 禹貢 5 (1936) 12, pp. 19–20.

- Korolkov, Maxim. 2011. “Arguing about Law: Interrogation Procedure under the Qin and Former Han Dynasties.” Études chinoises 30 (2011), pp. 37–71.

- Li Wai-yee. 2017. “Anecdotal Barbarians in Early China.” In: Paul van Els – Sarah A. Queen (eds.), Between History and Philosophy: Anecdotes in Early China. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 113–144.

- Liu Chungshee Hsien. 1932. “The Dog-Ancestor Story of the Aboriginal Tribes of Southern China.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 62 (1932), pp. 361–368.

- Lu Jialiang 鲁家亮. 2013. “Liye chutu Qin ‘buniao qiuyu’ jian chutan” 里耶出土秦“捕鸟求羽”简初探. In: Wei Bin 魏斌 (ed.), Gudai Changjiang zhongyou shehui yanjiu 古代长江中游社会研究. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, pp. 91–111.

- Lombard-Salmon, Claudine. 1972. Un Exemple d’acculturation chinoise: La province du Gui Zhou au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient.

- Lu Xiqi 魯西奇. 2008. “Shi Man” 釋蠻. Wenshi 文史 84 (2008) 3, pp. 55–75.

- Maspero, Henri. 1927. La Chine antique. Paris: De Boccard.

- Miyakawa, Hisayuki. 1960. “The Confucianization of South China.” In: Arthur F. Wright (ed.), The Confucian Persuasion. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 21–46.

- Nylan, Michael. 2012. “Talk about ‘Barbarians’ in Antiquity.” PEW 62 (2012) 4, pp. 580–601.

- Pines, Yuri. 2005. “Beasts or Humans: Pre-imperial Origins of the Sino-Barbarian Dichotomy.” In: Reuven Amitai – Michal Biran (eds.), Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World. Leiden – Boston: Brill, pp. 59–102.

- Pines, Yuri.. 2018. “Chu Identity as Seen from Its Manuscripts: A Reevaluation.” Journal of Chinese History 2 (2018), pp. 1–26. doi: 10.1017/jch.2017.17

- Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書. 1979. Guanzhui bian 管錐編. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- Schafer, Edward. 1954. The Empire of Min. Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle.

- Selbitschka, Armin. 2015. “Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik vs. the so-called Tributary System.” AM 28 (2015) 1, pp. 61–114.

- Tackett, Nicolas. 2017. The Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tan Qixiang 谭其骧. 1987. Changshui ji, shang 长水集上. Beijing: Renmin chubanshe.

- Venture, Olivier. 2011. “Caractères interdits et vocabulaire officiel sous les Qin: l’apport des documents administratifs de Liye.” Études chinoises 30 (2011), pp. 73–98.

- Wang Gungwu. 1973. “The Middle Yangtze in Tang Politics.” In: Arthur F. Wright – Denis Twitchett (eds.), Perspectives on the T’ang. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 193–235.

- Wang Ming-ke. 1992. “The Ch’iang of Ancient China through the Han Dynasty: Ecological Frontiers and Ethnic Boundaries.” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University.

- Wang Su 王素. 2005. “Changsha Dongpailou Dong Han jiandu xuanshi” 长沙东牌楼东汉简牍选释. Wenwu 文物 2005/ 12, pp. 69–75.

- Wang Wan-chun (Wanjun) 王萬雋. 2009. “Qin-Han Wei-Jin shidai de ‘cong’” 秦漢魏晉時代的“賨”. Zaoqi Zhongguo shi yanjiu 早期中國史研究 1 (2009), pp. 125–156.

- Wang Zhongqian 王仲牽. 2003. Wei Jin Nanbeichao shi 魏晋南北朝史. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe.

- Wei Dongchao 韦东超. 2003. “Yimin yu zuji chongtu: Dong Han shiqi Wuling Changsha Lingling sanjun ‘Manbian’ dongyin qianlun” 移民与族际冲突——东汉时期武陵、长沙、零陵三郡“蛮变”动因浅论. Zhongnan minzu daxue xuebao 中南民族大学学报 23 (2003) 1, pp. 62–65.

- White, David Gordon. 1991. Myths of the Dog-Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wylie, Alexander. 1882. “History of the Southern and South-Western Barbarians: Translated from the How Han Shoo, Book CXVI.” Revue de l’Extrême-Orient 1 (1882), pp. 200–246.

- Yan Gengwang 嚴耕望. 2007. Liang Han taishou cishi biao 兩漢太守刺史表. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

- Yang Lu. 2014. “Managing Locality in Early Medieval China: Evidence from Changsha.” In: Wendy Swartz et al. (eds.), Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 95–107.

- Yang Shao-yun. 2014. “Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500–1200.” In: Francesca Fiaschetti – Julia Schneider (eds.), Political Strategies of Identity-building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 9–35.

- Yang Shao-yun. (Forthcoming). The Way of the Barbarians: Reinterpreting Chineseness and Barbarism in Tang and Song China, 800–1140. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Yü Ying-shih. 1967. Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Zeng Daiwei 曾代伟 – Wang Pingyuan 王平原. 2004. “Manyi lü kaolüe” 蛮夷律考略. Minzu yanjiu 民族研究 2004/3, pp. 75–84.