吉德煒 (1932–2017) 是西方漢學界甲骨文研究的先鋒,亦是商周兩朝歷史研究領域的巨擘。他一生著作頗豐,其中他獨到的見解對甲骨學殷商史學科的貢獻尤為顯著。在這訃聞中,髙嶋謙一教授回顧他們生活與學術上的相遇,痛悼摯友——吉德煒。

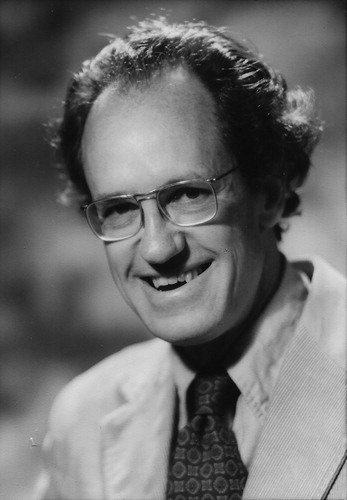

David N. Keightley, Professor Emeritus at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, and scholar of the highest stature in the field of Chinese history, specifically Shang (ca. 13th – 11th c. B.C.E.), passed away peacefully in Berkeley, California on 23 February 2017 at the age of 84 years.

A memorial service was held in honor of David Keightley at Sunset View Cemetery, El Cerrito, CA 94530, on Saturday, 25 March 2017, with Rev. Stephen Winton-Henry officiating. There were approximately 60 to 70 attendants, a great majority of whom seemed to have had some connection with UC Berkeley and included, of course, David’s family members and their friends. I flew from Nagoya to Vancouver in late February and then flew from there to Oakland to attend the service and pay my profound respects. I only knew two other people at the service from earlier times: David’s wife, Vannie Keightley and Michael Nylan, who succeeded David as professor of early Chinese history in the Department of History, UC Berkeley. I did not see any other Sinologists at the service and the ensuing luncheon reception except for David Johnson, also professor emeritus, Department of History, UC Berkeley.

If a scholar or teacher in any field of study is to be evaluated, it should be based on the merit of the works that he or she has produced as perceived by those in the same profession. I personally feel, however, that there is a humanity that underlies and percolates throughout the works of a scholar, both in the substance of the works and the ways in which they are put forward. This especially seems to be the case in the field of humanities. In addition to my almost half-a-century association with David as my mentor and friend, three books David wrote (CitationKeightley 1978, Citation2000, and Citation2012) provide the basis for my judgment of him as a scholar of the highest stature. To these I would add one short paper (Citation1989) as the basis for my further judgment of him as a teacher of great resourcefulness.

David was born on 25 October 1932 in London, to Walter A. Keightley, an American veteran of WW I and petroleum engineer, and Jeanne G. Descoutter, an Anglo-French dress designer living and working in London. They met and married there and gave birth to David. He received his early education in English boarding schools until he was fifteen years old. Then, in 1947, the family moved to Evanston, Illinois. Since such biographical information, including that for his later years, is widely available from two other sources,Footnote1 I would like to provide my personal memories and reminiscences about David that show that he was a true junziru 君子儒 (gentleman-scholar) and describe how he influenced my own tenets for scholarship, ever since a life-changing spring-quarter break in 1970 when I visited him in Berkeley.

I was then just a beginning graduate student at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle. I was working towards an M.A. in the field of Chinese and Japanese linguistics. I was struggling to understand these subjects under the tutelage of Professors Li Fang-kuei 李方桂 (1902–1987), Leon Hurvitz (1923–1992), and Paul L-M. Serruys (1912–1999), but became interested enough to see if I could compare the vowel systems of the two old languages. The Old Chinese phonological system as reconstructed by Professor Li has four vowels, which I compared with the then prevalent eight-vowel system of Old Japanese to see if there were systematic correspondences. After I managed to obtain the degree in 1967 with a thesis on a phonological comparison of Old Chinese and Old Japanese, I took a year off from graduate school because I found a job at Washington University in St. Louis, teaching modern Japanese. I did not yet know David at that time.

In September 1968, I resumed my graduate studies at UW. Because I was very much interested in Classical Chinese, I signed up for all the courses offered by Prof. Rev. Fr. Paul L-M. Serruys, who had succeeded to the position held by Professor Erwin Reifler (1903–1965). Professor Reifler had continued to teach up to the moment he passed away in April 1965, including a course on Chinese epigraphy that I was auditing. Fr. Serruys came to UW that fall to teach the Classical Chinese courses (first- and second-year levels) Professor Reifler had taught. He also introduced a new course on the earliest dictionary of Chinese characters, Shuowen jiezi 說文解字, followed by graduate seminars in Zhou bronze inscriptions and then in Shang oracle-bone inscriptions in the fall of 1969.

When I first saw David, after studying oracle-bone inscriptions for a few months under Fr. Serruys, I knew nothing about the subject. I can probably ascribe such lack of confidence to the fact that initially we, the students, were not expected to read the original inscriptions reproduced on rubbings (or “ink squeezes”); we were taught to read the normalized Chinese script transcribed from the palaeographs by other scholars. However, I became interested in David’s Columbia University Ph.D. dissertation “Public Work in Ancient China: A Study of Forced Labor in the Shang and Western Chou” (CitationKeightley 1969a), which he had sent to me upon my request. He also sent me a copy of the typescript review of Shima Kunio’s Inkyo bokuji sōrui 殷墟卜辭綜類 before it was formally published (CitationKeightley 1969b). I was immensely impressed. I was also so excited to realize that there was in Berkeley a scholar who, besides my most feared and exacting teacher Fr. Serruys in Seattle, could write about oracle-bone inscriptions and the society that had produced them with such consummate skill. It made me wish to beg an audience with him. When asked if I could see him, he said he would be pleased to do so. When the spring-quarter break came, I took a long-distance Greyhound bus to Berkeley.

David and his wife, Vannie, an artist, invited me to their rented apartment in Berkeley for lunch on the day after my arrival in Berkeley. I was surprised to see that they had also invited Professor Chao Yuen Ren 趙元任 (1892–1982), as well as his wife Yang Buwei 楊步偉 (1889–1981), who had studied medicine at Tokyo Women’s College of Medicine (Tokyo Joshi Igaku Daigaku) for a few years before she married Chao in 1921. Mrs. Chao still spoke a bit of Japanese, and she started a conversation with me in Japanese. She understood most of my Japanese, but her own was a bit rusty. After all, more than half a century had elapsed since she had lived and studied in Tokyo. Professor Chao was so well known, and I had read many of his works when I was studying Chinese linguistics. In any event, I had a very pleasant afternoon with all of them.

Particularly memorable on that occasion was when David asked me how my study of oracle-bone inscriptions with Fr. Serruys was going and how I planned to pursue oracle-bone inscriptions studies in the future. All I could answer was that I wanted to understand what the inscriptions said as originally intended, since that was what Fr. Serruys taught us to do. In the classroom all Fr. Serruys did was to discuss characters, words, and grammar. My ready answer to David’s question was therefore no more than a mere reflection of Fr. Serruys’s teaching. But, in point of fact, after nearly half a century of study, I would still give exactly the same answer as I did in 1970, though this time not in parrot-fashion. By now I understand my aims. David went on to tell me what he wanted to work on in the future. I cannot remember most of the topics he mentioned, but I can still recollect that one of them was “Shang divination and metaphysics,” because I told Fr. Serruys about it when I returned to Seattle. He replied: “Metaphysics! We don’t even understand what the inscriptions say!”

One would think that Fr. Serruys, having been an ordained priest of Congregatio Immaculati Cordis Mariae (C.I.C.M.) and having had solid training in theology, metaphysics, religion, ideologies, and the like, might perhaps have been more interested in such matters. While he spent most of his novitiate at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, he also spent a year studying theology at Nijmegen in Holland. However, he never even touched on any such topics in his seminars. There, the subject matter was always graphology, phonology, syntax, philology and, above all, oracle-bone inscriptions as texts. More than three quarter of my life has now passed since I began studying oracle-bone inscription texts, but I confess I know next to nothing about them. I will think to myself one day that I have finally deciphered a graph or an inscription, but the next day I may come up with a completely different interpretation. The late Professor Peter A. Boodberg (1923–2014) of UC Berkeley – the teacher of my teacher – reportedly remarked: “Philology is an endless conversation with the dead.” It is so profound a subject that any scholar of oracle-bone inscriptions ought to be humbled by the notion of “obtaining the lofty goal,”Footnote2 before he can claim that he figured out what the diviners, kings, and other ruling elite were saying some three millennia ago. Decipherment is a reverse process of estimating what they said or inscribed. Most importantly, however, the oracle-bone inscriptions represent a language, and there are ways we can use to come closer to deciphering it, but never, I am afraid, perfectly.

David was actually instrumental to shaping the way I feel about studying oracle-bone inscriptions. Just to mention one anecdote, three of us, David, David S. Nivison of Stanford University, and I debated for well over ten years about the meaning of just one word, the so-called modal particle qi 其, which has been variously translated into English as “perhaps, perchance,” “in this case,” “certainly, resolutely, surely,” “I/we fear … ,” and “his, her, its, their.” Some of these translations are actually conflicting if we think about them carefully. The printed copies of our exchanges, most of which have never been published, amount to a 3-inch thick binder, more or less. I still have these papers and occasionally dip into them to refresh my mind about what we were discussing. One of them is a paper over two hundred page long David wrote (CitationKeightley 1995b). I responded with a typescript paper (CitationTakashima 1995). Fr. Serruys had joined the debate soon after it all got started with David Nivison’s unpublished paper (CitationNivison 1968). While Father Serruys’s paper (Citation1974) was duly published in T’oung Pao, the two Davids and I continued to argue back and forth well into the 1990s. I myself will soon have an article on this subject, with step-by-step explanations, in an edited volume; hopefully it will be the decisive say on the matter (Takashima, forthcoming, Citation2019a). But, alas, the two Davids, both gentleman-scholars with the greatest minds I have been lucky to encounter, are no longer here to critically respond to it.Footnote3

In connection with the books he wrote – I cannot even remember which one now, but conceivably with all of them, including most of his papers – David Keightley once told me “my scholarly responses are in the footnotes.” About which David Johnson (Citation2003, pp. v–vi) wrote: “I believe I introduced David to the saying (attributed to Aby Warburg) ‘God is in the details.’ He made this motto his own, as his students and colleagues can attest, and it does sum up an important part of his scholarly credo.” I also think that David Keightley’s scholarship reflects a deep sense of humanity, whether it is related to early Chinese civilization in general or his explicative modules on Shang civilization in particular. His often-imaginative archaeological analyses of material seem to support this,Footnote4 and sometimes even his commentaries to his English translations of the oracle-bone inscription textsFootnote5 seem to demonstrate humanity.

Frances Starn, who carried out extensive oral interviews with David Keightley, kindly commented on an earlier draft of this memorial essay by saying: “David always stressed his dedication to detail, but in fact he also had a much larger historical vision.”Footnote6 David’s zeal for detail has already been noted in his own words and in Johnson’s “Introduction” to CitationStarn 2003. However, we cannot end this essay without giving a bit more thought to Frances’s comment, as well as to another remark by David Johnson who added that “He is of course interested in words as well as things, and in interpretive schemes as well as technical detail, and is extremely good at finding large themes and writing about them with precision and elegance. Yet it seems to me that his instincts always pull him back from the general to the specific, from the broad generalization to the concrete particular” (Johnson Citation2003; emphasis mine). The question is how David acquired such a “larger historical vision” or “large themes” in the first place? Being basically a palaeographer-cum-philologist, it is difficult to imagine that David – or any cultural historian for that matter – had any large vision of ancient Chinese history or far-reaching historical themes, before the arduous task of trying to understand or decipher Shang oracle-bone inscriptions was seriously undertaken.

In this connection, David once told me about the expression “hedgehog and fox,” the former figuratively referring to a rather ugly animal that, with its single-mindedness, delves into a fact and is proud of trying to know everything about one big thing, while the latter is a sophisticated, elegant creature that accumulates a lot of facts and is proud of knowing many things, though it is sometimes deceitful.Footnote7 He mentioned the expression when he was working on his review article of a book on Shang religion and culture by the Japanese scholar, Akatsuka Kiyoshi 赤塚忠 (1913–1983) (CitationKeightley 1982), and he deemed Akatsuka a wily fox in our conversation. The expression “a fox knows many things, but a hedgehog one important thing” has been interpreted in different ways ever since a Greek lyric poet named Archilochus (ca. 7th c. B.C.E.) first used it and later, in the 1950s, Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997) wrote a popular essay about it.Footnote8 But I liked the image of a hedgehog that does the spadework of digging and gnawing at any fact, deriving great pleasure in trying to make sense of it. David was both a hedgehog and a fox, though without the slightest trace of deceitfulness. It is easy to admire him, but difficult to emulate him.

Epilogue: I am most grateful to Professor Michael Nylan who kindly read the second draft of this essay and suggested a number of editorial and stylistic revisions. She also informed me that David donated quite a sum to help fund graduate students interested in early China. In our exchanges about this memorial essay, she said, “As I get older, I appreciate how unusual it is for great intelligence and great humanity to come together in a single person. I miss him sorely.”

Besides Frances, to whom I have already expressed my appreciation for her help in writing this memorial essay, I am also grateful to Steven Keightley and Chris Button (my former student at University of British Columbia) for their input in finalizing this essay. It is thus fair to say that this piece is the result of the collaborative effort of at least four supportive friends. Our message is: how we miss David Keightley!

Notes on Contributor

Takashima Ken-ichi is professor emeritus of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. His research covers the fields of Chinese palaeography, philology and linguistics of Old Chinese, with an emphasis on the study of bronze incriptions of the Western Zhou dynasty. Among his most recent publications are: “Shāng 商 Chinese, Textual Sources and Decipherment,” in: Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics, vol. 4 Shā–Z, pp. 5–22. Ed. Rint Sybesma (general ed.), Wolfgang Behr, Yueguo Gu, Zev Handel, C.-T. James Huang, and James Myers (associate eds.) (Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2017) and A Little Primer of Chinese Oracle-Bone Inscriptions with Some Exercises, 2nd revised ed. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2019).

Notes

1 One is an obituary prepared by David’s two sons, Steven and Richard, based on a biosketch David himself wrote. Their obituary is available on the website of Sunset View Cemetery at: https://www.sunsetviewcemetery.com/obituary/david-n-keightley/ (last accessed 31 January 2019). The second source is not an obituary, but a very detailed transcript of an oral history interview conducted by Frances Starn, running over 200 pages (CitationStarn 2003).

2 This is an adapted translation of a Japanese expression.

3 David Shepherd Nivison, Professor Emeritus at Stanford University, passed away in Los Altos, California on 16 October 2014 at the age of 91. An “Obituary for Stanford University Professor Emeritus David S. Nivison,” written by one of his students was posted on Philosophy Talk (website) on 6 March 2015 at: https://www.philosophytalk.org/blog/obituary-stanford-professor-emeritus-david-s-nivison (last accessed 31 January 2019).

4 For example, in Keightley (Citation2014, pp. 4–7) he divided Neolithic North China into forming two cultural complexes: East Coast and Northwest. He contrasted their pottery types, characterizing the East Coast pots as “(1) unpainted; (2) angular, segmented, carinated profiles were common; (3) frequently constructed componentially; and (4) frequently elevated in some way,” while “[t]he ceramic tradition of the Northwest [ … ] was characterized by a more limited repertoire of jars, amphoras, and round-bottomed bowls and basins, [ … ]” (pp. 4–5). He then considers the design, manufacture, styles, functions, mensuration, and other properties of these pots, squeezing out the “mentality” of the potters who made the vessels and the peoples who used them. For the East Coast cultural sphere, he has identified “deliberation and control, a taking of time to plan the shapes, to measure the parts, and to join them together” and the “prescriptive, and thus componential, construction” of the East Coast pots. I would not have expected that in a later section, “Fit and Mensuration” (pp. 19–21), he connected (3), the componential construction of the East Coast pots, to the origins of Chinese characters by noting that the oracle-bone graph typically consists of the signific and the phonetic elements that are combined to form a unit. This is, to say the least, a completely new idea. Its validity, however, is another question.

5 For example, in Keightley (Citation2014, p. 102) he discusses the “rationality and clarity of the divination charges” by which he means that even though Shang pyromancy is supposed to be a symbolic activity, the inscribed divination charges in the oracle-bone inscription text are couched in straightforward, administrative prose that indicate “nothing manifestly symbolic about them” (ibid.). This may be discerned, he argues, from such oracle-bone inscription examples as: “‘it will rain’; ‘it will not rain’; ‘the king should ally with this tribe’; ‘the king should attack that one’; ‘the king’s dream was caused by such-and-such an ancestor’; ‘there will be good harvest,’ etc.” All these, he says, “were recorded ‘in clear’. Anyang was not Delphi, where the words of the Pythia had to be translated, frequently ambiguously, by priests. Shang divination was ‘cool’ and ordinary, uninspired and rational.”

6 Private communication, e-mail message dated 3 August 2017.

7 In Japanese folklore, foxes are considered as crafty, sly, cunning and good at deceiving and leading humans astray.

8 The Hedgehog and the Fox (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1953).

9 Frank Joseph Shulman, “David Noel Keightley (1932–2017), Publications and Unpublished Writings: A Comprehensive Bibliography and Research Guide.” EC 40 (2017), pp. 17–61.

10 Under (3) Shulman included two items that had been “directed by David N. Keightley.” If we strictly follow Keightley’s “publications and unpublished writings,” these two items – both Ph.D. dissertations written by his students – do not belong in here.

11 The bibliographical details of CitationKeightley 1995a, Song Zhenhao – Chang Yaohua 1999 are given above, under “Bibliography.” This is due in part to avoid confusion with the entries in this supplement. For Paul Goldin’s bibliography (last updated 7 December 2018), visit: “Ancient Chinese Civilization: Bibliography of Materials in Western Languages” (http://www.academia.edu/37490636/Ancient_Chinese_Civilization_Bibliography_of_Materials_in_Western_Languages [last accessed 11 January 2019]). “My own files” refer to many papers Keightley sent to me over the years.

12 Although Shulman included Keightley’s unpublished works that were eventually published, we have chosen not to do so. This will reduce the total number of Keightley’s works. Most of the works given here were produced in typescript, which he sent to me. Keightley also deposited some of them to C.V. Starr East Asian Library at UC Berkeley and to the University of California Library, East Asian Rare Extension. There is little doubt that Keightley made use of all the results of much research that went into producing these unpublished papers. For example, in 1976 Keightley wrote a paper called “Where Have All the Heroes Gone: Reflections on Art and Culture in Early China and Early Greece” which was published under the title “Where Have All the Swords Gone? Reflections on the Unification of China,” EC 2 (1976), pp. 31–34.

13 Quite uncharacteristic of David Keightley, this paper is not dated. However, judging from the use of pinyin, it was written in the early 1990s – cf. Henry Rosemont’s Introduction (p. xvii) in CitationKeightley 2014.

14 This is cited by Song Zhenhao – Chang Yaohua (1999, p. 65, item #771), but no other details are given. It is possible that this was a conference paper presented in China.

Bibliography

- Johnson, David. 2003. “Introduction.” In: Starn 2003, pp. v–vi. [Johnson’s Introduction is dated 18 June, 2002, but he wrote it a few years before with some editing. See id., “DNK – Some Recollections, in Celebration.” EC 20 (1995), pp. vii–x.]

- Keightley, David N. 1969a. “Public Work in Ancient China: A Study of Forced Labor in the Shang and Western Chou.” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, New York.

- Keightley, David N.. 1969b. “[Review of] Shima Kunio 島邦男, Inkyo bokuji sōrui 殷墟卜辭綜類.” Monumenta Serica 28 (1969), pp. 467–471.

- Keightley, David N.. 1978. Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Keightley, David N.. 1982. “Akatsuka Kiyoshi and the Culture of Early China: A Study in Historical Method.” HJAS 42 (1982), pp. 267–320. [Review article of Akatsuka Kiyoshi 赤塚忠, Chūgoku kodai no shūkyō to bunka: In’ōchō no saishi 中國古代の宗教と文化——殷王朝の祭祀. Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten, 1977.]

- Keightley, David N.. 1989. “‘There Was an Old Man of Chang’an … ’: Limericks and the Teaching of Early Chinese History.” The History Teacher 22 (1989) 3, pp. 325–328. Also contained in: Keightley 2014, pp. 311–313. doi: 10.2307/492868

- Keightley, David N.. 1995a. “The Works of David Noel Keightley.” EC 20 (1995), pp. xi–xvii.

- Keightley, David N.. 1995b. “Divinatory Conventions in Late Shang China: A Diachronic and Contextual Analysis of Oracle-Bone QI 其 and Related Issues.” Typescript ms. dated 19 July 1995. iii, 236 pp. plus one-page abstract, unpaginated.

- Keightley, David N.. 2000. The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.). China Research Monograph, 53. Center for Chinese Studies. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.

- Keightley, David N.. 2012. Working for His Majesty: Research Notes on Labor Mobilization in Late Shang China (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.), as Seen in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions, with Particular Attention to Handicraft Industries, Warfare, Hunting, Construction, and the Shang’s Legacies. China Research Monograph, 67. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.

- Keightley, David N.. 2014. These Bones Shall Rise Again: Selected Writings on Early China. Edited and with an Introduction by Henry Rosemont, Jr. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Nivison, David S. 1968. “So-called ‘Modal Ch’i’ in Classical Chinese.” Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the American Oriental Society. Berkeley, 19 March 1968.

- Serruys, Paul L-M. 1974. “Studies in the Language of the Shang Oracle Inscriptions.” TP 60 (1974) 1–3, pp 12–120.

- Song Zhenhao 宋鎮豪 – Chang Yaohua 常耀華 (eds.). 1999. Bainian jiaguxue lunzhumu (budingban) 百年甲骨學論著目 (補訂版) [One Hundred Years of Discussions on Oracle Bones]. Beijing: Yuwen chubanshe.

- Starn, Frances (ed.). 2003. “David N. Keightley, ‘Historian of Early China, University of California, Berkeley, 1969–1998,’ an Oral History Conducted in 2001 by Frances Starn, Regional Oral History Office, the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2003,” see online: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/rohoia/ucb/text/earlychinaunicali00keigrich.pdf (last accessed 31 January 2019).

- Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一. 1979. “Some Philological Notes to Sources of Shang History.” EC 5 (1979), pp. 48–55.

- Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一. 1995. “Divinatory Conventions and Grammar in the Shang Oracular Inscriptions: Notes on a Recent Contribution of Professor David Keightley.” Typescript ms. dated 13 August 1995. 12 pp.

- Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一. 2014. “Review Article: Working for His Majesty: Research Notes on Labor Mobilization in Late Shang China (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.), as Seen in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions, with Particular Attention to Handicraft Industries, Warfare, Hunting, Construction, and the Shang’s Legacies by David N. Keightley (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 2012).” TP 100 (2014), pp. 237–263.

- Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一. 2019a. “A Lexical Category in Oracle-Bone Inscriptions: Vcontrollable or Vuncontrollable.” Paper presented to International Symposium on Typological Regularity of Semantic Change in Grammaticalization and Lexicalization. Bellingham: Western Washington University, 22–23 April 2017.” Scheduled to appear in a volume edited by Janet Z. Xing. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

- Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一. 2019b. “A Review Article of These Bones Shall Rise Again: Selected Writings on Early China by David N. Keightley.” Edited and with an Introduction by Henry Rosemont, Jr. (Albany: SUNY, 2014).” In preparation.

Appendix: A Supplement to Frank Shulman (2017)Footnote9

As a tribute to David Keightley, Frank Shulman, a professional bibliographer, compiled a comprehensive bibliography of David Keightley’s writings, both published and unpublished, with terse descriptions of many entries, often excerpted from the contents of individual entries, collectively referred to as “research guide.” Shulman organized his bibliography under ten major sections: (1) Monographs, (2) Editorships and Edited Volumes, (3) Dissertations and Theses,Footnote10 (4) Articles and Book Chapters, (5) Review Articles and Reviews, (6) Translations, (7) Conference Papers, Seminar Papers, Guest Lectures, and Selected Unpublished Manuscripts, (8) Reviews of David N. Keightley’s Publications, (9) Other Publications, and (10) Publications and Information about David N. Keightley. In this supplement to Shulman (2017) we have excluded sections (8), (9) – which includes introductions by other scholars to Keightley’s works in the field of oracle-bone studies –, and (10) as well.

Shulman gives 4 titles for Monographs, 4 items for Editorships and Edited Volumes, 3 titles (without counting the two items written by Keightley’s students, q.v. n. 10) for Dissertations and Theses, 66 titles for Articles and Book Chapters, 37 items for Review Articles and Reviews, 2 items for Translations, and 48 items for Conference Papers, Seminar Papers, Guest Lectures, and Selected Unpublished Manuscripts. Thus, Keightley authored or edited a total of 164 scholarly works. The scholarly impact his works gave to the field of ancient Chinese civilization in general and to that of oracle-bone studies in particular are profound.

Given below are bibliographical items to supplement and, in some cases, modify Frank Shulman’s list of David Keightley’s works. This supplement was made on the basis of four sources: (1) CitationKeightley 1995a, pp. xi–xvii; (2) CitationSong Zhenhao – Chang Yaohua 1999; (3) Paul R. Goldin (updated 7 December 2018); and (4) my own files.Footnote11

Review Articles and Reviews

“Lun taiyang zai Yindai de zongjiao yiyi” 論太陽在殷代的宗教意義 (The Religious Significance of the Sun in Shang Times). Translated by Liu Xueshun 劉學順. Yindu xuekan 殷都學刊 1999/1, pp. 16–21. [This is a translation of “With an Excursus into the Religious Role of the Day or Sun,” from entry no. 2].

“Graphs, Words, and Meanings: Three Reference Works for Shang Oracle-Bone Studies, with an Excursus into the Religious Role of the Day or Sun.” JAOS 117 (1997) 3, pp. 507–524. [Review Article of: Matsumaru Michio 松丸道雄 – Takashima Ken-ichi 高嶋 謙一, Kōkotsumoji jishaku sōran 甲骨文字字釋綜覽; Yao Xiaosui 姚孝遂 – Xiao Ding 肖丁 (eds.), Yinxu jiagu keci moshi zongji 殷墟甲骨刻辭摹釋總集 and Yao Xiaosui – Xiao Ding (eds.), Yinxu jiagu keci leizuan 殷墟甲骨刻辭類纂.] The Chinese translation of Keightley’s review article by Liu Yifeng 劉義峰 is: “Wenzi, cihui he hanyi: Shangdai jiagu yanjiu de sanbu cankao zhuzuo” 文字、詞匯和涵義——商代甲骨研究的三部參考著作, Yindu xuekan 殷都學刊 2007/3, pp. 15–23.

Translations

3. Wang Ningsheng 汪寧生, “Yangshao Burial Customs and Social Organization: A Comment on the Theory of Yangshao Matrilineal Society and Its Methodology.” EC 11–12 (1985–1987), pp. 6–32. [The original title in Chinese of an abbreviated version (revised October 1986) appearing in Wenwu 文物 4 (1987), pp. 36–43, was: “Yangshao wenhua zangsu he shehui zuzhi de yanjiu: Dui Yangshao muxi shehuishuo ji qi fangfalun de shangque” 仰韶文化葬俗和社會組織的研究——對仰韶母系社會說及其方法論商榷.]

Unpublished WorksFootnote12

4. “‘These Bones May Live / These Bones May Perhaps Not Live’ (A Comment on ‘Can These Bones Live? The Concept of Royal “Virtue” [De (德)] in Shang China’, by David Shepherd Nivison).” Presented at the Workshop on Classical Chinese Thought, Harvard University, 2–13 August 1976. 8 pp.

5. “The Pyromantic Cracks: Their Significance and Power.” March 1978. 12 pp.

6. “Happy New Year: A Response to Edward Shaughnessy’s Christmas Card of 15 December 1988.” 15 January 1989. 6 pp.

7. “Shang Charges and Prognostications: The Strong and the Weak?” Presented at the 25th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley, 11 October 1992. ii, 44 pp.

8. “Certainty and Control in Late Shang China: Modal QI in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions.” 28 July 1993. i, 64 pp.

9. “Executive QI [其] in Shang Oracle-Bone Inscriptions: A New Hypothesis.” 30 January 1994. 49 pp.

10. “Making a Mark: Reflections on the Sociology of Reading and Writing in the Late Shang and Zhou.” Presented at the conference on “Sociology of Writing,” University of Chicago, 6–7 November 1999. 55 pp.

11. “Wai Bing [卜丙=外丙] and Wo Ding [沃丁] in the Late Shang Ritual Cycle and Genealogy.” 5 June 2002. 15 pp.

12. “On the Term SIMU [司母].”Footnote13 12 pp.

13. “The World of the Royal Diviner.”Footnote14