ABSTRACT

To transform traditional postgraduate psychotherapeutic training programmes, we need educational strategies which acknowledge every clinical interaction as culturally situated. Autoethnography is put forward as a method of research-based self-study which can enable students to foster an awareness of the social unconscious. This approach can aid students bridge the gap between social order and the individual psyche, allowing the conceptualisation of collective aspects of individual subjectivity. An example of educator autoethnography – which explores accent as an embodied expression of both personal and sociocultural identity – is offered as illustration of the potential application of this strategy to the classroom.

Introduction

Increasingly psychoanalytic theory has come under criticism for neglecting the influence of taken-for-granted sociocultural norms and values around diversity, and for privileging internal life over the external reality of the patient (Brown Citation2010, 289; Wachtel Citation2009). In response to these criticisms, scholars examining cultural competence have attempted to forge a way forward. For the clinician, cultural competence is the ability to provide therapy that can overcome cultural barriers existing in the therapeutic relationship. This is based on the premise that the more a clinician knows about a patient's culture, the more likely that person will feel understood. However, difficulties have arisen when integrating cultural competence into psychotherapeutic training and practice, with a formulaic approach being taken, promoting a concrete script of issues related to otherness (Hart Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Hart Citation2019, Citation2020). While psychoanalytic scholars often address specific aspects of diversity such as gender, race, immigration, religion, sexual orientation and social class, the literature lacks a set of core principles to inform and support a culturally competent practice.

In place of what Hart (Citation2017b) refers to as the acquisition of competency in relation to issues of sociocultural diversity, Tummala-Narra et al. (Citation2018) recommend that psychotherapeutic training integrating an in-depth understanding of sociocultural issues with an emphasis on unconscious processes, defenses and emotionality is vital for culturally informed psychotherapeutic practice. South African critical scholars – such as Esprey (Citation2013), Foster (Citation1999), Hook and Parker (Citation2002), Lobban (Citation2013) and Swart (Citation2013), amongst others – also make a similar argument about the importance of challenging mainstream psychological practice and advocate engagement with the concept of the psycho-political. Psychoanalytic cultural competence, both locally and internationally, should refer to “a process of recognising, understanding, and engaging with sociocultural context and its influence on intrapsychic and interpersonal processes, including the therapeutic relationship” (Tummala-Narra Citation2016, 77). What is needed, therefore, are postgraduate psychotherapeutic training programmes which reflect an appreciation of how minority and majority group identities are rooted in the context of particular social (racialised, classed and gendered) interactions. In response to this need, autoethnography is suggested as a way for postgraduate psychology studentsFootnote1 to begin to integrate the impact of how identity is formed at particular historical and political junctures. In doing so, autoethnography can enable psychotherapeutic training to enlarge its project, moving beyond the dyadic, to embrace every clinical interaction as culturally situated (González Citation2016).

Autoethnography is, as Ellis, Adams, and Bochner (Citation2011, 273) note, “an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experiences (auto) in order to understand cultural experiences (ethno)”. It can be a useful pedagogical tool to assist students to develop an awareness of the social unconscious – a concept drawn from group psychoanalysis (Dalal Citation1998; Foulkes Citation1964; Fromm and Funk Citation2017; Hopper Citation2001, Citation2007, Citation2011, Citation2018; Volkan Citation2001; Weinberg Citation2007). The social unconscious refers to an understanding of the unconscious that includes taken-for-granted attitudes, social norms and values, born out of a particular time and place in history. The basis of the social unconscious is to be found in the conventions that we are born into but have not reflected upon (Dalal Citation1998). In other words, we absorb, replicate and reinforce attitudes, norms and values without knowing that we are doing so. Our cultural milieu privileges particular ways of viewing and experiencing the world, while at the same time closes off other possibilities. An awareness of the social unconscious, therefore, affords us insight into how we are organised by our sociocultural and political context. It enables us to recognise the multiple sociocultural forces that affect us, potentially opening up the possibility to reorganise our constraints (c.f. Hopper Citation2018).

Drawing on the tenets of autobiography and ethnography, autoethnography is an approach which can enable students to engage in research-based self-study in order to begin to dismantle taken-for-granted cultural ties around gender, class, sexuality and dominant or minoritised cultural status. (For example, how certain forms of religion can reinforce patriarchy via beliefs concerning marriage and the family – seeing the father as the head of the home and responsible for the conduct of his family.) Self-study is characterised by Hauge (Citation2021, 2) as a specific form of action research which should not only be of significance to the person conducting the study, but also of importance for creating meaning and contributing to increased understanding and knowledge for others. Through engaging with autoethnography in the classroom, both educator and student can explore links between socio-political power relations and their subjective emotions, helping explicate feelings about shared unconsciously accepted assumptions of how things should be. Such a reflective process is important for students as how we see and make sense of the world influences how we perceive our patients and the causes of the difficulties presented (Swart Citation2013; Tummala-Narra Citation2015).

In terms of the potential application of this strategy to the classroom, educator autoethnography is a useful first step in integrating the impact of how identity is formed at particular historical and political junctures into psychotherapeutic training. Educator autoethnography undercuts traditional hierarchical power dynamics, forging an educational environment that is democratic and collaborative, emphasising teaching through dialogue, and learning through lived experience.

In this paper my example of educator autoethnography explores accent as an embodied expression of both personal and sociocultural identity. This is a useful example as, in the clinical interaction, our accent (both the patient’s and the clinician’s) is one way our sociocultural embeddedness is embodied. While an accent can be defined as “the way a speaker sounds, which reflects the speaker’s linguistic backgrounds” (Kumagai Citation2013, 12), several researchers highlight that, once speakers are involved in interaction with one another, accents encompass the speakers’ group membership choices and the tensions between their personal identities and group identities (Gluszek and Dovidio Citation2010; Hooper Citation1994; Jenkins Citation2007; Lippi-Green Citation2012; Trudgill Citation1999).

To further substantiate autoethnography as an educational tool, I begin with a review of the gaps in the field of psychotherapeutic training before exploring how autoethnography can address these.

Principles for culturally informed psychotherapeutic training and practice

In South Africa, our violent history of apartheid and post-apartheid strife – including the xenophobic attacks, poverty driven riots and devastating floods that have gripped KwaZulu-Natal in 2022 – highlight issues of physical and emotional anguish, fractured and displaced families, acting out around difference, and economic suffering, that not only inform the backdrop to, but are also very palpable within the psychotherapeutic space. Often, in my teaching experience, the profound socio-political struggles students have encountered with their patients are brought to supervision. However, given the positivist underpinning of psychotherapeutic training programmes, educator and student often engage with these struggles in terms of internal defensive operations, negative automatic thoughts or genetic predisposition. This represents a missed opportunity to see people as active, purposeful agents, creating meaning and making choices in their lives, while their subjectivity is both restrained and contained by their social embeddedness.

Reviewing attempts to embrace the psychosocial and achieve cultural competence, international psychoanalytic scholars have also been critical of burgeoning cultural competence training, seeing such training as simply promoting a concrete script of issues related to otherness, leading to mechanical dialogue around difference within both the educational and therapeutic setting (Hart Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Citation2019, Citation2020; Hymer Citation2005; Petrucelli Citation2020). South African scholars, Ahmed and Swan (Citation2006), also caution that, as a result, current systems of injustice can remain unchecked. Such formulaic cultural competence training is seen as promoting an automated way of attending to difference and otherness, and may constitute a social defense (Jaques et al. Citation1955; Menzies-Lyth Citation1988) against anxieties associated with genuine openness to diversity. This form of cultural competence training represents a lost opportunity for personal reflection and deeper engagement (Hart Citation2017b). The challenge in psychotherapeutic training, therefore, is to develop pedagogical strategies which move away from focusing solely on intrapsychic processes, or which promote formulaic cultural competence, to ones which enable every clinical interaction to be understood as culturally situated.

In South Africa, as a result of the domination of patriarchal, heterosexual and white discourses, there has tended to be an avoidance of discussion around identity in psychotherapeutic training and practice (Esprey Citation2013). There is a pressing need, therefore, for race, class, gender, religion and sexual orientation, as well as other diversities, to be seen as aspects of identity which are dynamics of both the patient and clinician in the therapeutic space (Lobban Citation2013). To address this need, pedagogical strategies, which highlight that the individual cannot be separated from their social context, must be brought into all disciplines and sub-disciplines of the psychotherapeutic training programme. Such pedagogical strategies need to make students aware of their own gender, race and history, as, the more aware students are of their own social embeddedness, the less likely they are to dissociate from their own otherness and project it onto their patients (Swart Citation2013; Tummala-Narra Citation2015).

Transforming psychotherapeutic training, however, is complex and fraught with difficulties. There have been other attempts at tackling the positivist underpinning of training programmes in order to relinquish the idea of psychology as a neutral science. A good example of this is the emergence of community psychology, and the work of Organisation for Appropriate Social Services in South Africa (OASSSA), in the 1980s. At that time, in response to the need to address apartheid atrocities and traumas, diverse community interventions arose alongside, and as part of, organised social activism. Here, trauma debriefing was provided for torture victims, counselling for former political detainees and support for conscientious objectors. As a result, psychology had to make sense of processes of social (as well as individual) change. However, subsequently there has been an increasing institutionalisation of the discipline of psychology. While community psychology is now an established sub-discipline in most South African universities, it is yet to make a significant impact (Yen Citation2015). The act of confining community psychology to a separate sub-discipline allows mainstream South African psychology to continue as usual (Yen Citation2015).

Ultimately, diversity-related pedagogy should be dialogic, with both educator and student being open to learn from each new encounter (Hart Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Citation2019, Citation2020). Based on his research and experience, Anton Hart also notes that curiosity in the face of difference and diversity can be difficult, as openness disturbs our understanding of self, other and the world. Acknowledging this, Hart believes that it is useful to bring to students’ attention the ways in which their curiosity has been limited and narrowed over the course of their lifetime. He argues that such self-reflection can help students formulate and understand something about the resistances they (and subsequently their patients) may feel when engaging with difference. In Hart’s words, “The defenses against the potential losses of status and sense of self that are contained in encounters with information about (distanced) others must first be approached, before there can be an appetite for new, nourishing information and contact” (Citation2020, 414).

Also highlighting the need for diversity-related training, Pratyusha Tummala-Narra (Citation2007, Citation2015, Citation2016; Tummala-Narra et al. Citation2018) has spearheaded research into psychoanalytic cultural competence. She introduces a framework for culturally informed psychoanalytic psychotherapy where she outlines approaches she believes are essential for cultural competence within psychoanalytic training.

Importantly, like Hart (Citation2017b, Citation2017a), Tummala-Narra also believes that self-examination in theory and practice is critical for developing a sense of authenticity. She highlights the importance of understanding how conscious and unconscious processes are shaped by sociocultural realities and social oppression, and how these processes affect dynamics between the student (or clinician) and the patient. She points to unconscious processes that perpetuate social oppression – for example, defense mechanisms that inform understandings of prejudice and aggression. Tummala-Narra believes that attention should be paid to unconscious processes relevant to the student’s own experiences of trauma and social oppression, as, like Swart (Citation2013), she believes such processes can influence how the student engages with the patient. Significantly, Tummala-Narra’s work highlights the need to develop pedagogical tools which facilitate student exploration of how their own sociocultural realities and social oppression shape both their conscious and unconscious processes.

Drawing together Hart (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2019, Citation2020) and Tummala-Narra’s (Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018) thoughts on diversity-related teaching, it is clear that they believe psychoanalysis can open up dialogue across boundaries marked by racial, ethnic and cultural difference in a way that is deeply personal. Here in South Africa, and globally, this does not simply entail rote learning about difference and diversity, but rather involves a process of interested curiosity, self-reflection and radical openness to how conscious and unconscious processes are shaped by sociocultural realities (including social oppression and trauma), and how these processes are played out in the clinical dyad. Hart (Citation2017b) sees such radical openness as bringing about the possibility of challenging and revising the understandings the student (or clinician) and patient bring individually to the dialogue, be they cultural, racial, sexual, socioeconomic or otherwise.

In sum, to generate culturally informed psychotherapeutic practice we need to develop pedagogical strategies which help us recognise how some of our most deeply held attitudes and feelings have their roots not only in our family, but in the cultural and societal circumstances in which we grew up. We need educational tools which help us recognise and work with how such deeply held attitudes and feelings unconsciously affect our relationships and choices in very profound ways. We need strategies that help us challenge the psycho-social split within psychoanalysis itself, which has resulted in the unlinking of the personal from the political. In other words, we need tools which enable us to see our social embeddedness as complex, constitutive and meaningful – as helping us make sense of ourselves and others (Adams Citation2008; Bochner Citation2001).

Autoethnographic methodology

In response to the crisis of representation relating to claims of universal truths within traditionally dominant positivist methodologies in the human sciences (Marcus and Fischer Citation1986), autoethnography has been developed as a means of legitimising personal experience as a knowledge source. Moving away from universal truths, autoethnography is an approach to research which recognises subjectivity, emotionality and the researcher’s influence on the research itself (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011). In other words, autoethnographic writing does not feature the traditional distanced researcher, but is written in the first person, highlighting stories of relationships and emotions affected by social and cultural frameworks (Meekums Citation2008). Here, researcher subjectivity is seen as a legitimate lens for the examination of social and cultural phenomena, rather than a voice to be purged.

As a method, autoethnography combines characteristics of autobiography and ethnography; I will look at each in turn. With autobiography, the writer explores their own past experiences, interviews others and consults texts such as photographs, journals and recordings. Ellis, Adams, and Bochner (Citation2011) point out that often autobiographers write about epiphanies, moments felt to have significantly impacted on the course of that person’s life. With ethnography, on the other hand, researchers study a culture’s relational practices, common values, beliefs and shared experiences for the purpose of helping both cultural insiders and outsiders better understand that culture (Maso Citation2001). Ethnographers do this by becoming participant observers, interviewing cultural insiders, examining insiders’ ways of speaking and relating, investigating use of space and place, analysing artefacts such as clothing and architecture, and texts such as books, movies and photographs (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011). Thus, combining the characteristics of autobiography and ethnography, autoethnographers write about epiphanies that stem from being part of a culture.

Whilst authoethnographic methods vary considerably, Bonnie Meekums (Citation2008) points out that a broad methodological approach is consistent with reflective clinical practice. Her perspective is useful for the purpose of this paper. In developing her methodology, Meekums draws on the philosophical tradition of postmodernism which assumes multiple positions, perspectives and voices. She understands stories as the bridge between self and culture, where the things we “know” about ourselves, and the world are seen as influenced by dominant cultural narratives. Meekums also draws from narrative forms of psychotherapy, where the process of reauthoring implies a progressive process, rather than a static product. In other words, Meekums imagines authoethnographic research as both ongoing and potentially uncomfortable, like the process of psychotherapy itself.

Methodologically, Meekums (Citation2008, 289) proposes the researcher starts with initial questions around a chosen epiphany, such as: “How did I get to this turning point?” To explore the unconscious aspects of such a turning point she suggests following up with secondary questions:

How much of my journey so far has been agentic, and how much opportune?

What role has the social unconscious played?

What has influenced my decision-making?

What role does my body play in this process?

How does the process of writing this story contribute to the ongoing construction of my identity?

Following from these research questions, Meekums suggests that a researcher should discover for themselves the most appropriate way to engage with their inquiry, be this in the form of journaling, a dream diary, poetry, prose, photographs, archival material or intentional reflection and recall. Struthers (Citation2012) highlights that engagement and reflection around the process of inquiry can provide the researcher with an opportunity to further understand psychological and cultural influences on subjectivity. Also, in relation to the pedagogical use of autoethnography, Goffman (Citation1963) stresses the benefit of the educator disseminating self-awareness about their own identity to students, in alignment with Hart’s (Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Citation2019, Citation2020) ideas of self-reflective, radical openness, humility and fallibility.

Procedure

As I mentioned earlier, the act of the educator opening aspects of their identity to their students dissolves the traditional hierarchy between teacher and student, expert and novice. It also allows students to engage with sensitive human issues and offers the potential for them to become more aware of taken-for-granted sociocultural and political norms in preparation for their own researched-based self-study. Educator autoethnography allows for social dialogue and exploration in an atmosphere of shared learning between students and educator. Through group discussion and facilitation, educator autoethnography can help students reflect on their own socially embedded values and perspectives, leading to deeper analysis of concepts, ideas and solutions (Good and Brophy Citation2003; Killen Citation2013). In this way, autoethnography, as a pedagogical strategy, can be seen to promote Freire’s (Citation2018) idea of teaching through dialogue, rather than banking learning, as well as learning through lived experience.

Educator autoethnography can be effective when introduced at the beginning of postgraduate psychotherapeutic training. Here it can form a foundation, bridging the gap between social order and the individual psyche, creating a basis upon which all psychotherapeutic disciplines and sub-disciplines within the programme can then be built. This foundation can also be developed by encouraging students to engage in their own autoethnographic study as a research component of the programme.

The procedure that I followed in my self-study (and when training students) evolved as I engaged in a process of free association and reflective contemplation of my own social embeddedness in the traditions, routines and practices into which I was born. This unconscious process brought to the fore my accent and its significance to me. Such an idiosyncratic journey is important for the autoethnographer as it affords the self-study its uniquely personal dimension. For others this journey might lead them to focus on other ways our sociocultural embeddedness is embodied, such as religion, race, class, gender, manners, gestures or colloquialisms, amongst others.

To explore “How did I get to this turning point?” I had to engage in a process of attempting to make the unconscious aspects of my epiphany, conscious. To do this, I followed Meekums (Citation2008) suggestion and contemplated the question, “How did I get to this turning point?” Here, I recalled that my accent was a very contentious issue during my childhood and adolescence. To elaborate, when I considered the question “How much of my life’s journey so far has been agentic, and how much opportune?” I realised that throughout my life I have been acutely aware of my accent as both a personal and cultural expression of who I am. Mulling over the question, “What role has the social unconscious played in this process?”, I realised how, having moved around a lot as a child, my accent always made me stand out from my peers as someone alien or foreign – not a cultural insider. Reflective introspection around my “otherness” coalesced as I considered the question, “What has influenced my decision-making?” I realised how at times this experience of otherness has been traumatic and devastating, while at other times, a bedrock of my individuality and creativity.

Once I decided upon my accent as the focus of my self-study, I then engaged with the following brief steps adapted from Meekums (Citation2008, 289–290). These steps may be a useful guide when engaging with autoethnographic research within psychotherapeutic training:

I wrote a very brief list of the influences I could recall.

As I contemplated this list, I began to see certain connections. Key experiences emerged, which I noted down.

I brought out some old photograph albums, journals and diaries, and looked at significant items I had kept from childhood. I looked for signs of embodied experience and a sense of my whole self being involved and potentially changed. These experiences triggered strong emotional reactions of love and acceptance, as well as fear and rejection in me.

I selected artefacts which included maps, poems and personal manuscripts that were especially evocative, and arranged them into tables. I noted down some associations I had with each.

I then asked myself a specific question, in response to these aspects: “What has their impact been on my accent as an embodiment of my identity?” My answers to this question form the subject matter of the discussion and conclusion of this paper.

An example of educator autoethnography

What follows are the notes I kept during my own self-study, used subsequently as a starting point for discussion with my students and as an example of how they might go about their own autoethnographic research:

A brief list of the sociocultural and political influences impacting on my accent:

The Troubles (the Northern Ireland Conflict, 1968–1998)

Moving countries (from Northern Ireland to the mainland [England] at age 6)

Personal “troubles” (being discriminated against and stereotyped at school)

A list of key experiences I connected with these influences:

Experiences with my grandparents and parents

Experiences with bullies at school

Next, I gathered together a group of significant artefacts which evoked strong emotional reactions in me. These artefacts included maps, personal photographs, press images, a poem and a picture I drew for the cover of a school magazine. I noted down my associations to these artefacts as follows:

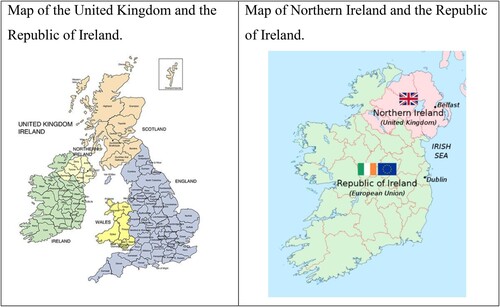

Maps of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland ()

Northern Ireland is a very small country, comprising only six counties. The population is also tiny: in 2011, according to the census (ONS Citation2011), it was 1 810 863, making up about 30% of Ireland’s total population and about 3% of the population of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland has no natural resources and has a long and turbulent history of violence and unrest which has impacted industry and industrial development. In my experience, these difficulties, coupled with Northern Ireland’s cold, wet climate, have contributed toward people emigrating away from the country. As a result of these factors, even the capital, Belfast, feels more like a village than a city.

As a child I recall passers-by greeting one another as they walked along the street, always sparing a kind word, a sweet or some loose change to give to a “youngster”. There was little crime: cars would be left unlocked and front doors ajar. It is hard to believe from this impression that, simultaneously, this neighbourly and peaceful society was profoundly divided. Deep hatred fuelled a violent conflict that lasted thirty years, resulting in a generation of children who grew up against a backdrop of bombs, explosions, assassinations and riots. According to Rose (Citation1976) by 1975 nearly one family in every six had a relative killed or injured in the Troubles.

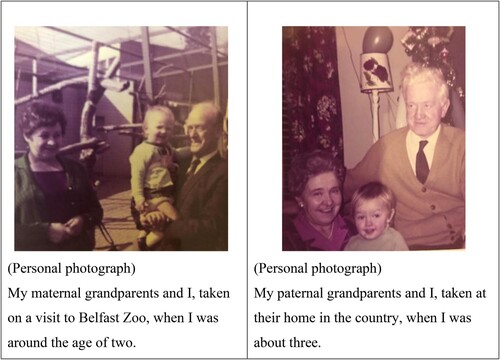

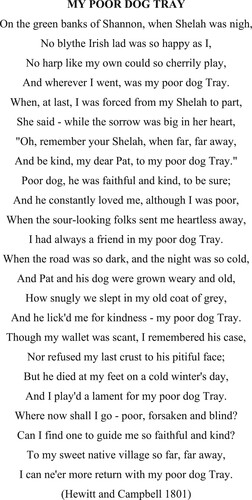

Personal photographs and a press image ()

My early memories of my childhood are informed by a strong sense of cultural heritage – filled with a poignant oral history. This was passed down to me from my grandparents and parents in the form of stories, poems, music and dance – rich in a sense of the past, magic and lore. All related to a pastoral sense of a life close to nature, with homemade artisanal food such as stews, breads and hearty soups.

My paternal grandparents lived in the countryside. My grandfather played the violin in the local orchestra and would entertain the family after returning from long walks across the fields. My paternal grandmother was an avid Royalist and spent her evenings reading by a turf fire (turf, or peat, is a Northern Irish coal substitute dug by hand from peat bogs). My maternal grandparents, while originating from the countryside, settled in Belfast after their marriage. My maternal grandmother was a great dancer, dress maker and orator. While she was a headstrong matriarch, she was also incredibly caring, kind and generous. My maternal grandfather “escaped her clutches” by working well into his seventies, enthusiastically supporting the local football team on the “wireless” and attending live matches in his free time. ()

My maternal grandfather was always playful, often enquiring of the four-year-old me: “Who are you going to marry when you grow up? A soldier or Georgie Best?” While said in a tongue and cheek manner, these suggestions reflect the social unconscious at play – there was a privileging of particular ways of viewing and experiencing the world. Beyond privileging heterosexuality, my grandfather’s suggestions of a soldier emphasised a strongly British heroic machismo. Of the two possible life partners, the soldier was an acknowledgement of Operation Banner, the British Armed Forces’ operation in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2007. For my grandfather British soldiers were heroes, risking life and limb to protect Northern Ireland from terrorists. Similarly, “Georgie” (George) Best was also a British heroic figure, a sporting icon. While the choice of Best was a clear reference to my grandfather’s love of football, it was also a nod to a strong sense of nationalism.

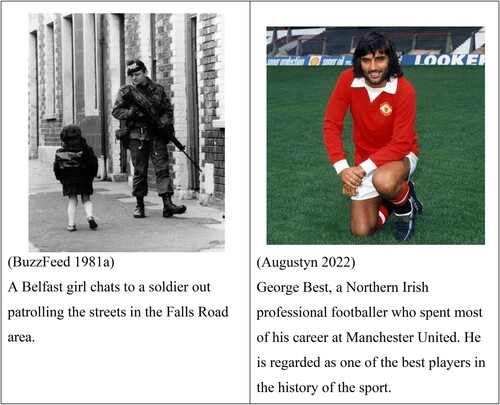

A poem my maternal grandmother would recite to me

The poem “My Poor Dog Tray” (Hewitt and Campbell Citation1801) speaks to me on multiple levels. It expresses my maternal grandmother’s love for a past filled with love, devotion, loyalty and commitment. Not only is it evocative of her as a person, but these attributes are perhaps reflective of all that was right and wrong with Northern Irish society – a conservativism that bread obedience rather than curiosity. According to Cairns (Citation1987), Northern Ireland during the Troubles was a society where the majority of young people still had doubts about gambling, drunkenness and premarital sexual intercourse. The majority of children attended school regularly and kept on the right side of the law. Cairns notes that they did so because they accepted what their elders told them. He suggests that this same unquestioning attitude, or conservative outlook, may have also perpetuated the Troubles from generation to generation. ()

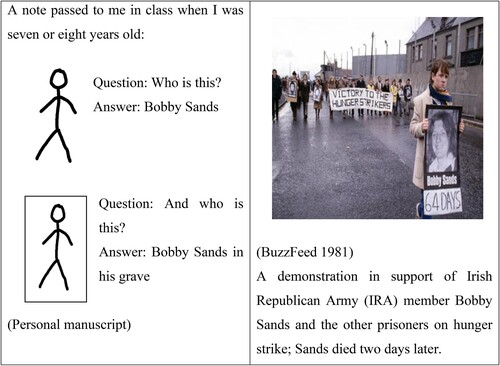

A personal manuscript and a press image

When I was six my family moved from Northern Ireland to England. Our move was met with much excitement and hailed a great opportunity by both our immediate and extended family and friends. My father, as an industrial chemist in the textile industry, had been headhunted by a large manufacturing company based in Cheshire, England. To my parents, the fit seemed perfect: a great job, nice house and good schools. My family faced the move without trepidation – England was simply another part of the British Isles. However, my peers at my new school did not take the same position. As soon as I introduced myself my accent made me stand out from my peers as someone alien and foreign – not a cultural insider – and they treated me as such.

A particularly frightening experience occurred when, on one occasion, I was passed a note in class. This caused me great discomfort – I knew it was a transgression of the school rules. It put me at risk of being sanctioned by my teacher. The note itself also scared me – I interpreted its subject matter as referring to terrorism and death. ()

I could not understand why my peers had linked me with Bobby Sands. He was a member of the IRA who fought for the united Ireland cause. He died on hunger strike while imprisoned at HM Prison Maze in Northern Ireland, in 1981. The impression the note left me with was that my peers wanted me dead.

In dismay, I turned to my parents for help. Their advice to me was simple, “Talk slow to be understood.”

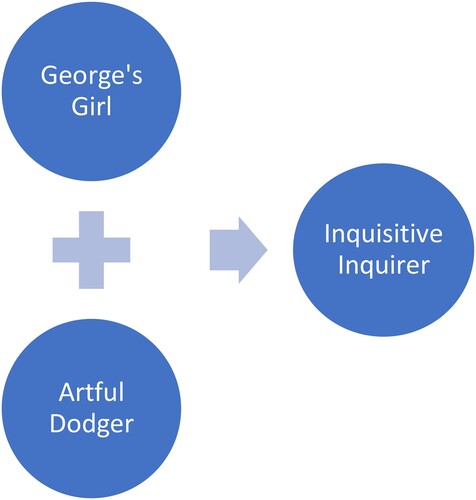

“George’s Girl”, the “Artful Dodger” and the “Inquisitive Inquirer”

Thinking about my parents’ advice to me, and reflecting on these influences, I came up with the following three central personas: “George’s Girl”, “Artful Dodger” and “Inquisitive Inquirer”. The George’s Girl persona is associated with the question my grandfather would ask me about my choice of life partner, and also after St George, the patron saint of England. The Artful Dodger persona is associated with the character in Charles Dickens’ novel Oliver Twist. This character is known both for his skill and cunning, but also as a child who had suffered. In the discussion that follows I will explore how these two aspects came together to form the Inquisitive Inquirer persona.

Discussion

Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, by age six I had developed the soft, lilting “brogue” that identified me firmly as an insider – not only a member of my particular family, but also part of the community of east Belfast. While, from an outsider’s perspective, this may seem mildly informative, to an insider during the Troubles this identified me in terms of my nationality and religion, and, by the tender age of six, as having a position in the conflict.

My brogue was the embodiment of a close-knit sense of love, security and support, conveyed through culturally vibrant traditional stories, music, dance and poetry. This cultural heritage was palpable in our home and, at a civic level, in the schools, bars, restaurants and theatres frequented by my family and community. This very partisan start to life gave my George’s Girl persona a sense of strength, community and solidarity.

The Artful Dodger, on the other hand, was a much lonelier persona. This was a persona that went through an evolution from being bullied and put upon by classmates, to holding herself apart, evaluating and making up her own mind about things. In many ways it was a persona in stark contrast to George’s Girl. The Artful Dodger’s gift was hiding in plain sight – part of the group but separate, removed and, eventually, agentic.

My agency was hard won, however. To elaborate, despite my overtly nationalistic, politicised and religious start to life, there is little trace of the east Belfast brogue in my accent today. My accent is nonaligned. In fact, despite having moved to several countries throughout the world, and currently residing in South Africa, my accent has changed little since I was thirteen. Many people have tried to figure out where I am from, but none have succeeded (part of the skill of the Dodger).

In many ways my accent is neutral. This neutrality is beguiling, masking as it does the obliteration of George’s Girl’s sense of strength, community and solidarity. However, while my brogue may have been extinguished, it was not conquered – I have not assimilated the accent of any new culture – my accent is uniquely my own. While the extinction of the east Belfast brogue was akin to taking off the albatross around my neck, with the loss of the bird came a fracturing of the social fabric that connected me to my extended family and my country’s rich cultural heritage. This loss was a bitter cross to bear for my fledging self.

Denzin (Citation1989) suggests that cultural discourses and conventions provide framing devices for the stories we tell about our lives. One such framing device was the Northern Irish Conflict. The Troubles organised my sense of self and life at a physical, social and political, as well as an unconscious, level. I lived in the British/Protestant side of Belfast, went to a British/Protestant school, a British/Protestant church, belonged to British/Protestant clubs and played with British/Protestant children. I grew up with the Union Jack flying from flag poles in peoples’ gardens and houses, red-white-and-blue paint on the street curbs, and British soldiers patrolling the streets with the understanding that they were there to keep me, and my fellow British citizens, safe. I was accustomed to bag inspections and body checks by soldiers and security officers upon entering a large shop. (This was done in an effort to prevent such items as miniaturised incendiary devices being smuggled in). In an attempt to halt car bombing, Belfast city centre was closed to private cars, and “control zones” were established. These were areas where cars could be parked but never left unattended. Thus, I became accustomed to going with my parents when they went to the city centre but stayed in the car while my parents went off to the shops – a living symbol that our car did not contain a bomb.

Violence and death were everyday realities during the Troubles. The conflict was the longest period of concentrated civil disturbance and sectarian violence to have hit the western world in modern times (Cairns Citation1987). The conflict was primarily political and nationalistic, fuelled by historical events, read differently by each opposing side. It also had an ethnic, or sectarian, dimension. A key issue was the status of Northern Ireland. Unionists and loyalists, who for historical reasons were mostly Ulster Protestants, wanted Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom. (Ulster is the name for Northern Ireland used commonly by Unionists). Irish nationalists and republicans, who were mostly Irish Catholics, wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and join a united Ireland. Northern Ireland has two histories – one for each religious community. These histories impinged on day-to-day life, arose in arguments and, ultimately, became justification for the Troubles.

The traditions, routines and practices of the British/Protestant citizens of Northern Ireland during the Troubles (in which I was embedded) perhaps represent aspects of a social defense system (Jaques et al. Citation1955; Menzies-Lyth Citation1988). Here, traditions, routines and practices seemed to have a defensive function which served to bind me and the community members of east Belfast together as “brothers in arms” within the “family” of the British/Protestant Northern Irish community. Social defenses working as a system comprised many aspects of my reality. Unconscious defenses, such as splitting, projection, denial and idealisation, seemed to become entwined with cultural practices. For example, splitting and idealisation were clearly evident in the “all good/all bad” thinking about the Protestants and Catholics, the British Army and the IRA. This social defense system bound me together with my peers while also physically and psychologically distancing me from other citizens around me, as well as the violence of the conflict. The purpose of such a system appeared to detract from any anxiety that may have arisen from loss and death, and reflecting on, or contemplating, a sense of identity from an outsider’s perspective.

Although the Troubles mostly took place in Northern Ireland, at times violence spilled over into parts of the Republic of Ireland, England and Europe. Over the thirty-year span of bloody unrest, political tensions and religious rhetoric, the Troubles received extensive media coverage, both locally and internationally. However, although this media coverage enabled vast numbers of people to witness the same traumatic events, the meaning ascribed to these events differed greatly. This is evident in the reaction of my new peers, and their families, when I moved to England. To better understand this difference, some insight into the social defense systems and social unconscious operating within my new culture is essential.

Economic recession gripped the British Isles during the 1980s, with falling output, rising unemployment and a decline in the inflation rate. Jobs were hard to come by, strikes and protests became an everyday occurrence, and coal mines were forced to close, causing more people to be without work. A solution to unemployment was for people to join the British Armed Forces. Thus, many of my peers’ friends and family members became soldiers – the same soldiers who were then deployed to the streets of Northern Ireland. Night after night the news was filled with horror stories of the Troubles. At the height of the Troubles, heavily armed British soldiers were a common sight in Northern Ireland, with a peak of about 27 000 British troops garrisoned there. Marked by street fighting, sensational bombings, sniper attacks, roadblocks and internment without trial, the confrontation had the characteristics of a civil war. This made the British soldiers, and members of the Northern Irish Police – Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) – what the IRA called “legitimate targets”. Unfortunately, these “targets” mostly lived in their own homes with their families, and so these civilians were brought into the firing line. To cope with the anxiety of death and loss, a social defense system may have arisen. Here, unconscious defenses, such splitting, projection, denial and idealisation, seemed to become entwined with cultural practices, such as the playground jokes, games, teasing and bullying I experienced in England. Like the dinosaur in the picture I drew for my school magazine cover, I suddenly found myself surrounded and under attack. ()

Attack came in the form of jibs and jibes from other children the same age as me, being called names like “Paddy” and chased home from school by older children. I became a “legitimate target” because of my accent. I was stereotyped as Irish, and, therefore, the enemy – killer of British soldiers. Through stereotyping my peers could humiliate and belittle me, making me the butt of a plethora of jokes which portrayed the Irish as imbecilic. Again, we can see the defense of splitting (whereby the moral complexities of psychic and social life become reduced to good and bad polarities) in operation here: if I was bad/stupid then they were good/clever. The creation of me as the evil enemy served a cohesive social function, providing these children with what Rustin (Citation2004, 34) suggests are “psychic reassurances in identification with their nation against its enemies”. Ironically, my brogue, which had so clearly identified me as British in east Belfast, had the opposite effect in this English playground.

The solution came in the form of advice from my parents to make myself understood. The conscious act of talking slower gave me space to think and reflect, to find my voice. This was an aspect of my identity that could consider and evaluate, rather than simply accept and bear. With new-found space, the rhythm of my speech changed – it lost some of its lyrical quality. I consciously removed colloquialisms such as “wee” for “small”, and “you’s” for “more than one person”. I also adjusted certain pronunciations to a more standard form – “film” instead of “fil-im”. Over time, as the Dodger persona became more established, I was able to re-integrate some Northern Irish colloquialisms and embrace more of the lyricism of the east Belfast brogue. With this reclamation came a sense of agency and empowerment. I could use these expressions to create the impression I desired. Here, the “Inquisitive Inquirer” was formed. The Inquisitive Inquirer persona was associated with someone aware of her historic context yet open and curious about others. ()

Conclusion

This example of educator autoethnography highlights the potential application of this methodology to research-led teaching and learning. Introducing this constructivist pedagogical strategy at the beginning of postgraduate psychotherapeutic training lays the foundation for students to make use of the methodology to trace the impact of how their identity has been formed at particular historical and political junctures (Foster Citation1999; González Citation2016; Hart Citation2017a; Hook and Parker Citation2002). It demonstrates a potential means for students to gain a personal understanding of sociocultural issues, unconscious processes, defenses, affective experience and the complexity of identity (Tummala-Narra et al. Citation2018). Through autoethnography students can explore the conventions that they have been born into but have not reflected upon, gaining the opportunity to reflect on an understanding of the unconscious that includes taken-for-granted attitudes, social norms and values, born out of a particular time and place in history (Dalal Citation1998; Hopper Citation2018). This can enable students to more fully understand the culturally situated resources they bring into their future work as clinicians.

The fragments of texts and narratives presented here are one woman’s experience of the Northern Irish Conflict and its impact on her identity. However, the hope is that it can speak powerfully to others in the way that brings the socio-political context to life. Following Meekums (Citation2008), the process of writing has demanded a self-reflexive engagement with very personal material. At the same time this practice has encouraged me, as an educator, to consider my development within a socio-historical context. This has been empowering as it relocates my experience beyond the personal and into political discourse.

Subsequent research will explore student engagement with autoethnography in the classroom, as well as the usefulness of this pedagogical tool to other fields in the social and human sciences. It is hoped that such research may prove useful in challenging the domination of positivism in these fields (Marcus and Fischer Citation1986).

Acknowledgements

This work is based on the research supported by the National Institute for The Humanities and Social Sciences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Hereafter referred to simply as students.

References

- Adams, Tony E. 2008. “A Review of Narrative Ethics.” Qualitative Inquiry 14 (2): 175–194. doi:10.1177/1077800407304417.

- Ahmed, Sara, and Elaine Swan. 2006. “Doing Diversity.” Policy Futures in Education 4 (2): 96–100. doi:10.2304/pfie.2006.4.2.96.

- Bochner, Arthur P. 2001. “Narrative’s Virtues.” Qualitative Inquiry 7 (2): 131–157. doi:10.1177/107780040100700201.

- Brown, L. S. 2010. Feminist Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Cairns, Ed. 1987. Caught in the Crossfire. Belfast: Appletree Press.

- Dalal, Farhad. 1998. “Taking the Group (Really) Seriously. Race, Racism and Group Analysis.” Group Analysis 0 (0): 05333164211041549. doi:10.1177/05333164211041549.

- Denzin, Norman K. 1989. Interpretive Biography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ellis, C., T. E. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Historical Social Research 36 (4): 273–290. doi:10.12759/hsr.36.2011.4.273-290.

- Esprey, Y. 2013. “Raising the Colour bar: Exploring Issues of Race, Racism and Racialised Identities in the South African Therapeutic Context.” In Psychodynamic Psychotherapy in South Africa, edited by C. Smith, G. Lobban, and M. O’Loughlin, 304. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Foster, Don. 1999. “Racism, Marxism, Psychology.” Theory & Psychology 9 (3): 331–352. doi:10.1177/0959354399093004.

- Foulkes, S. H. 1964. Therapeutic Group Analysis/by S.H. Foulkes. Vol. London: Allen & Unwin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn849953.

- Freire, Paulo. 2018. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Fromm, Erich, and Rainer Funk. 2017. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx and Freud. Bloomsbury Revelations Edition. ed.Bloomsbury Revelations. New York: Bloomsbury Academic USA.

- Gluszek, Agata, and John F. Dovidio. 2010. “The way They Speak: A Social Psychological Perspective on the Stigma of Nonnative Accents in Communication.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14 (2): 214–237. doi:10.1177/1088868309359288.

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books.

- González, Francisco J. 2016. “Only What is Human Can Truly be Foreign: The Trope of Immigration as a Creative Force in Psychoanalysis.” In Immigration in Psychoanalysis: Locating Ourselves, edited by Julia Beltsiou, In Relational Perspectives Book Series, 15–38. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Good, Thomas L., and Jere E. Brophy. 2003. Looking in Classrooms. 9th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Hart, A. 2017a. “Diversifying Psychoanalysis: Reasons and Resistances.” In Unknowable, Unspeakable, and Unsprung: Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Truth, Scandal, Secrets and Lies, edited by J. Petrucelli, and S. Schoen, 225–231. London: Routledge.

- Hart, A. 2017b. “From Multicultural Competence to Radical Openness: A Psychoanalytic Engagement of Otherness.” The American Psychoanalyst 51 (1): 12–27.

- Hart, A. 2019. “Why Diversities?” The American Psychoanalyst 53 (3): 8–10.

- Hart, A. 2020. “Principles For Teaching Issues Of Diversity In A Psychoanalytic Context.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 56 (2-3): 404–417. doi:10.1080/00107530.2020.1760084.

- Hauge, Kåre. 2021. Self-Study Research: Challenges and Opportunities in Teacher Education. London: IntechOpen.

- Hewitt, James, and Thomas Campbell. 1801. “My Poor Dog Tray.” New York: Sold by J. Hewitt No. 23 Maiden Lane.

- Hook, Derek, and Ian Parker. 2002. “Deconstruction, Psychopathology and Dialectics.” South African Journal of Psychology 32 (2): 49–54. doi:10.1177/008124630203200207.

- Hooper, J. 1994. “‘Speaking Proper’: Accent, Dialect and Identity.” Occasional Papers No. 22.

- Hopper, Earl. 2001. “The Social Unconscious: Theoretical Considerations.” Group Analysis 34 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1177/05333160122077686.

- Hopper, Earl. 2007. “Theoretical and Conceptual Notes Concerning Transference and Countertransference Processes in Groups and by Groups, and the Social Unconscious: Part II.” Group Analysis 40 (1): 29–42. doi:10.1177/0533316407076113.

- Hopper, Earl. 2011. “The Social Unconscious in Persons, Groups, and Societies, Vol. 1: Mainly Theory.” In The Social Unconscious in Persons, Groups, and Societies, Vol. 1: Mainly Theory, edited by Earl Hopper, and Haim Weinberg. London: Karnac Books.

- Hopper, Earl. 2018. “Notes on the Concept of the Social Unconscious in Group Analysis.” Group 42 (2): 99. doi:10.13186/group.42.2.0099.

- Hymer, Sharon. 2005. “Subversive Redemption in Psychoanalysis.” The American Journal of Psychoanalysis 65 (3): 207–217. doi:10.1007/s11231-005-5760-0.

- Jaques, Elliot, Melanie Klein, Paula Heimann, and R. E. Money-Kyrle. 1955. New Directions in Psychoanalysis. London: Tavistock.

- Jenkins, J. 2007. English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and Identity. London: Oxford University Press.

- Killen, Roy. 2013. Effective Teaching Strategies: Lessons from Research and Practice. South Melbourne, Vic.: Cengage Learning Australia.

- Kumagai, Kazuaki. 2013. How Accent and Identity Influence Each Other: An Investigation of L2 English Speakers’ Perceptions of Their own Accents and Their Perceived Social Identities. MA: Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2012. “English with an Accent”. doi:10.4324/9780203348802.

- Lobban, G. 2013. “Subjectivity and Identity in South Africa Today.” In Psychodynamic Psychotherapy in South Africa, edited by C Smith, G Lobban and M O’Loughlin, 304, 54–72. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Marcus, George E., and Michael M. J. Fischer. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Maso, Ilja. 2001. “Phenomenology and Ethnography.” In Handbook of Ethnography, edited by Amanda Coffey Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, John Lofland, and Lyn Lofland, 136–144. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Meekums, Bonnie. 2008. “Embodied Narratives in Becoming a Counselling Trainer: An Autoethnographic Study.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 36 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1080/03069880802088952.

- Menzies-Lyth, I. 1988. “A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Social Institutions.” In Melanie Klein Today, Volume 2: Mainly Practice, edited by Elizabeth Bott Spillius, 463–475. London: Routledge. http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p = 179054.

- ONS. 2011. “2011 Census.” Edited by Office for National Statistics. www.ons.gov.uk: Open Government Licence.

- Petrucelli, Jean. 2020. “Introduction: Can We Speak to the Ism in Racism?: Changing the Conversation1.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 56 (2-3): 191–200. doi:10.1080/00107530.2020.1778993.

- Rose, R. 1976. Northern Ireland: A Time of Choice. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Rustin, Micheal. 2004. “The Perversion of Loss: Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Trauma.” In The Perversion of Loss: Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Trauma, edited by Susan Levy, and Alessandra Lemma, 21–36. Philadelphia, PA: Whurr Publishers.

- Struthers, John T. 2012. “Analytic Autoethnography: A Tool to Inform the Lecturer's Use of Self When Teaching Mental Health Nursing?”.

- Swart, S. 2013. “Naming and Otherness: South African Intersubjective Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy and the Negotiation of Racialised Histories.” In Psychodynamic Psychotherapy in South Africa, edited by C Smith, G Lobban and M O’Loughlin, 304, 13–30. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Trudgill, P. 1999. “Standard English: What it Isn’t.” In Standard English: The Widening Debate, edited by T. Bex, and R. Watts, 117–128. New York: Routledge.

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha. 2007. “Skin Color and the Therapeutic Relationship.” Psychoanalytic Psychology 24: 255–270.

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha. 2007 [2015]. “Cultural Competence as a Core Emphasis of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy.” Psychoanalytic Psychology 32 (2): 275–292. doi:10.1037/a0034041.

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha. 2007 [2016]. “Psychoanalytic Theory and Cultural Competence in Psychotherapy”.

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha, Milena Claudius, Paul J. Letendre, Ema Sarbu, Vincenzo Teran, and William Villalba. 2018. “Psychoanalytic Psychologists’ Conceptualizations of Cultural Competence in Psychotherapy.” Psychoanalytic Psychology 35 (1): 46–59. doi:10.1037/pap0000150.

- Volkan, Vamik D. 2001. “Transgenerational Transmissions and Chosen Traumas: An Aspect of Large-Group Identity.” Group Analysis 34 (1): 79–97. doi:10.1177/05333160122077730.

- Wachtel, Paul L. 2009. “Knowing Oneself from the Inside out, Knowing Oneself from the Outside in: The “Inner” and “Outer” Worlds and Their Link Through Action.” Psychoanalytic Psychology 26 (2): 158–170. doi:10.1037/a0015502.

- Weinberg, Haim. 2007. “So What is This Social Unconscious Anyway?” Group Analysis 40 (3): 307–322.

- Yen, J. 2015. “A History of ‘Community’ and Community Psychology in South Africa.” In Community Psychology: Analysis, Context and Action, edited by N. Duncan, B. Bowman, A. Naidoo, J. Pillay, and V. Roos, 51–66. Cape Town: UCT Press.