Abstract

Thematic assessment is offered with regard to Critical Arts’s incorporation into various Chinese trajectories and networks of cultural and media studies. The predominance of discourse analysis, corpus linguistics, and comparative empirical studies of Western and Chinese media is addressed for the period 2016–2023, as is the recent location of Critical Arts within the global discourse analysis publishing sector, that is mapped in Wang and Sun (2023, “Bibliometric Study on Chinese Discourse (1994-2021).” Critical Arts 1–17). The reasons for this narrow discursive framing are offered in comparison with another trajectory that is evident in the pages of the journal, one that emerges out of Chinese literary studies in conversation with Western theories, Western philosophies and which addresses big epistemological questions rather than questions of comparative “us-them” differences/correspondences or of administrative or linguistic detail. Finally, in addressing the different methodological directions that have been experienced in the journal’s pages, this overview seeks to act as something of a manifesto in returning Critical Arts to a more general cultural and media studies position. Our method of analysis is to symptomatically track and frame the Chinese meta-narratives as published in the journal, to identify and describe the themes that have been of concern to our various Chinese authors and editors, to relate these to cultural studies as inherited from the field’s earlier origins across the world, and to offer a paradigmatic map for future authors through which to conceptually filter their submissions. Our analysis was pre-circulated to the four Critical Arts editorial board China specialists, amongst others, who were invited to contribute to our narrative.

Taking our cue from British cultural studies as bequeathed by the Birmingham school, Critical Arts conducts periodic self-reflexive analyses of its content, spread of topics, and contemporary relevance (see, e.g. Tomaselli and Shepperson Citation2000). These reflexive self-reflections can be read in conjunction with the five yearly assessments of South African journals conducted by panels constituted by the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf Citation2019). Where the latter is concerned with the technicalities of international best practice, disciplinary and social impact, Critical Arts’ self-assessments aim at examining whether, and how, the journal has shaped cultural and media studies, and to identify what the contours look like. In the examination below we are particularly interested in how our Chinese authorship over the past 15 years has influenced the content, methodologies and theories that are now evident in the pages of the journal.

When Western cultural studies constructs images of itself it tends to restrict recognition of itself to the North Atlantic (see e.g. Hermes et al. Citation2017). Critical Arts has tried to open the door however to inter-hemispherical manifestations by rebranding itself in 2001 to address South–North relations, and since 2016, East–West relations also. The latter latitudinal inclusion has been largely effected by the welter of Chinese-based scholarship that found its way to our journal after 2015, following the first author’s integration into Chinese scholarship networks.

This analysis, then, firstly, offers a critical overview of the topics, themes and concerns of Chinese scholarship. Our second aim is to analyze what our Chinese authors consider as cultural and media studies, what trajectories are evident. Third, we are alert to these works’ choice of preferred methodologies and theoretical concerns, and in what ways they address – or elide – issues of power relations, state and social structures and democratization (see, e.g. Luo Citation2022).

Most importantly for our editorial board is the need to sketch some epistemological boundaries. We do this to emphasize some lacks, and to open up some areas that, while they are abundantly evident in African, Western Australasian and South American cultural Studies, have yet to find secured purchase within the Chinese conceptual frameworks promoted in the journal.

Mapping critical arts in discourse analysis journals

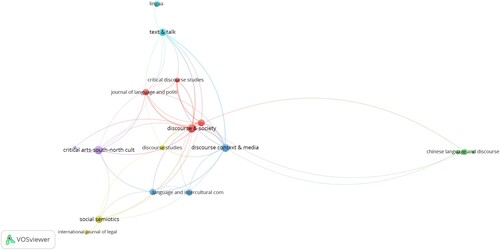

In doing a review of articles we have published on Asia more broadly, what stands out with the Chinese corpus is an astonishing emphasis on the use of comparative case study functionalist forms of discourse analysis (DA). The cognate corpus methods are technically applied in comparative discursive validity analysis of the image of China as represented in Chinese and Western newspapers respectively. This discourse emphasis by the majority of our Chinese authors has to some extent repositioned the journal from cultural and media studies as the field is applied in Western and African contexts. This positioning within the discourse analysis community is visually mapped by Wang and Sun (Citation2023). We are keen to explain why discourse analysis is so popular for so many of our Chinese authors and what the distribution of articles is (see and ).

Figure 1. Number of articles from each journal generated from VOSviewer. In a node represents a specific journal, and the size of the node indicates the number of publications, the larger it is the more papers it publishes, and connections between nodes constitute the cooperative relationship of different journals. Thanks to Xi Wang for generating the chart from his own data base (see Wang and Sun Citation2023).

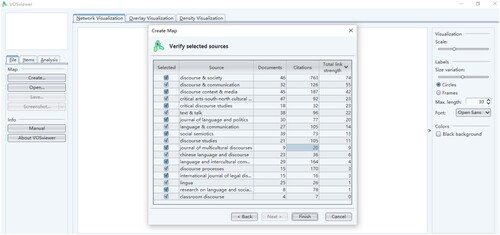

Table 1. Number of articles, citations and total link strength from each journal.

offers a schematic visual mapping of the 18 journals publishing in the area of discourse analysis. While Critical Arts is a late comer, largely driven by our Chinese authorship, the map alerts us to ask questions of position, positioning, and paradigm.

Figure 2. Screenshot of documents and citations of 18 journals in VOSviewer. From Wang and Sun (Citation2023).

Most analysis generated from Chinese-based scholars remains internal within the texts under scrutiny with little connection to the contexts, or to grounded realities, let alone political economy. The power dynamics processes of national policymaking dream speech are subordinated instead to strictly interpreting particular terms, phrases and sentences and moral values, many of which are attributed to the Chinese President (see, e.g. Feng, Chen, and Zheng Citation2016; Wang Citation2021; Zhang Citation2023). In fact, his frame of reference more or less mirrors exactly the scholars’ frame/s of reference, and the benchmark against which most Chinese-authored analysis is offered. This approach, as useful and linguistically rigorous as it is, rarely aligns with the journal’s expectation of critical analysis of texts, power relations, and how legitimacy is engineered through discursive means. In the Chinese context, although such work does propose new categorizations and understandings of hegemony at some levels, it rarely offers critical analysis that, in contrast, takes the goals and objectives of those agencies and organizations as the object of study (see Morgan Citation2006, 15). The journal opened its door to discourse analysis and corpus-based approaches as these seemed to us to be negotiating the China-trying-to go-global policy moment after 1978 when President Deng succeeded Mao Zedong, which requires an understanding of how the West makes sense of China in relation to how China makes sense of the West. This reciprocal sense making is the recurring theme in many of the discourse analyses published in Critical Arts (see, e.g. Duan Citation2020; Qiao Citation2020; Wu Citation2020b; Zeng Citation2020; Zhou Citation2020). To elaborate briefly, a comparative discourse analysis, for example, of “One country, two systems”, examines differences between British and American newspapers (Liu and Lin Citation2021). Another uses the visual evidence of classical Chinese gardens as a medium to reveal the influence and role of Western-centric theories on Chinese culture (Shen and Liu Citation2023).

The Wang and Sun (Citation2023) mapping study empirically reveals that Critical Arts has been incorporated into the discourse analysis publishing industry/community previously dominated by North Atlantic Journals. While the unsolicited Wang and Sun study does not explain this incorporation or the predilection for discourse and corpus analyses (as do we) it offers an enlightening descriptive mapping companion to our own article. We thus frame the Wang and Sun map in a tactical application to reveal the silences in discourse analysis and corpus-based approaches.

The volume of submissions from China for general issues from 2022 became a tsunami. Twenty articles a week were submitted just from Chinese scholars, and more from elsewhere. Of every 10 submissions from China, perhaps three are appropriate for consideration by us, as the rest are more suited for other journals in communication, linguistics and discourse analysis, art, music, folklore etc., as they are rarely grounded in what we understand – broadly – to be cultural studies (see, e.g. Connell and Hilton Citation2016). This has been a fascinating experience, as most Chinese authors apply some form of discourse analysis (DA) and related discursive methods, which are rare in Western British-derived cultural studies, though ubiquitous within the linguistic, literary, and language scholarly communities. From the Critical Arts perspective we are intrigued as to why the journal is now so prominent now in Chinese scholarship in general. Shi Xu, founder and editor of Multicultural Discourses, an early Chinese board member, and especially Doreen Wu had first kicked the discourse ball through with her special issues that she edited and co-edited (see, e.g. Wu Citation2008; Wu and Mao Citation2011; Xu Citationn.d.).

In contrast, scholars like Huimin Jin (Citation2017), Mao Sihui, You Wu and those located at Shanghai University (see, e.g. Zeng Citation2020, Citation2022) and in Australia provide the middle ground between the technical DA comparative case studies on the one hand and philosophically grounded social theories of globality, a cultural studies-in-the-world (where we would like Critical Arts to remain). The differences might be partly explained by Huang Zhuo-yue’s (Citation2016) presentation in 2014 at the 50th anniversary of the Birmingham’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. He identifies a number of attractions of the British initiative, but having to balance this with the period that said “farewell to revolutions” that evacuated debate over “the centre of politics”. This farewell and retreat from finding critical theory connecting points “to articulate their profession and the wider society” opened the door to the more highly technicized methods derived by discourse analyses, with “empirical and scientific studies being the only evaluating criteria for scholars’ achievements” (237). Chinese scholars during the early 2000s were looking for ways of dealing with global encounters and the “transcoding of ‘meanings’” (235), and cultural studies had afforded such a widening of analysis. One of the goals of the first generation of Chinese scholars was to resist and prevent all-dominating power which manifested as authoritarianism in the past and as domination of capitals and market in contemporary times. As such, concludes Zhuo-yue, “cultural studies always attempts to mobilize and release the agency of ‘a passive historical-cultural force’ in the social process … ” (238). We develop this analysis below.

Origins of critical arts

Critical Arts started life in 1980 as a deliberate anti-apartheid project that questioned notions of “high culture” from within a drama and film school. Critical theory was then a term unknown to us, but our approach serendipitously and with much less capacity shadowed the similar intellectual sources of what was already known in the Anglo-Saxon world as British cultural studies. Our approaches drew on the guidance of Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, whose grounding in politics, development studies and literature, presaged our studies of Karl Marx, Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser, Nicos Poulantzas, and later working in South America, Armand and Michele Mattelart, Jesus Barbiero and Bob White. The latter four were much more rooted in in the coalface grind of daily struggle than was the far more self-reflexive historicized trajectories generated by Stuart Hall, Richard Johnson and their extraordinarily innovative teams at the University of Birmingham from the 1970s (see e.g. Hall et al. Citation1980). To an extent, before the internet, and thanks to the cultural and academic boycott of South Africa, South Africans were at that time largely reliant on travelling academics, both ourselves and internationals, for exposure to new ideas, new syntheses and new ways of reading older theories.

South Africa shook off the shackles of apartheid after 1990 and set about reconstructing itself as a democracy. We also bid farewell to revolution, but with entirely different results to the Chinese trajectory as organized crime orchestrated via rogue state-owned enterprises became the norm (Buthelezi and Vale Citation2023). However, during the optimistic period of the 1990s, local journals needed to rethink themselves on how to work within the politically open conjuncture that followed liberation. Having rejoined the community of nations, with the economic, cultural and academic boycotts no longer in operation, Critical Arts thus rebranded as an inter-hemispherical cultural and media studies journal, still with a foot in Africa.

Like the Chinese under the presidency of Deng Xiaoping (1978–1997), South Africa started going global within two years of the first elections in 1994. At Critical Arts, we sought to extend both our authorship and readership into Asia, the South Pacific and Australasia, which faced us across the Indian Ocean Rim. This shift had been led by two editorial board members based in Australia. Ien Ang, of Indonesian origin, then at Murdoch University, guest edited “Asia, Africa, Australia” (Citation1996), drawing in authors from Aboriginal Australia, Singapore, India and South Africa. Ang’s Introduction responding to the post-apartheid transition of the 1990s had called on the journal to adopt “a new orientation towards the outside world, a new outward-lookingness which locks into, and responds to, the late twentieth century global drive towards transnationalism, regionalization and globalization” (Ang Citation1996, xxiii). She pointed out that the world’s oceans serve as geographic organizing principles for the major powers. New imaginations were needed to transgress the military, political, and economic boundaries that separate those countries looking into the Indian Ocean. However, in an analysis of Shanghai as a brand, Duncan Harte (Citation2017) argues that China’s gateway city has been a process less concerned with articulating an ethical stance of hospitality than with the reaffirming the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and attracting inward foreign investment (2017, 76).

Two years after Ang’s issue, her successor at Murdoch, Tom O’Regan, guest edited a theme issue on “Policy, Governance and Culture” (1998) to inform nascent moves within the new South African government of the utility of cultural policy studies and the principles of governmentality (see also Wu and Cheng Citation2022). The Ang and O’Regan numbers included articles on Aboriginal issues in Australia (e.g. Trees and Turk Citation1998; see also Galliford Citation2022), Singapore (Souchou Citation1996), Korea, India (Devadas Citation1996), Philippines and Hong Kong (Milgram Citation2012) and boat people (Neilson Citation1996). Since then, articles dealing with the Koreas and Japan have appeared (Cho & Chung Citation2009; Kim Citation2014; Wagner Citation2016; Yoon Citation2016, Citation2021).

Our essay aims to enable some sort of movement towards a more contextual Chinese cultural studies approach that addresses the central theoretical questions that characterize Western cultural studies and of course, those to which Zhuo-yue (Citation2016) refers, such as Chen Si-he (Citation1977) and his own books (see e.g. Zhuo-yue Citation2012).

Dissolving borders

In transgressing and denaturalizing inherited cultural borders we can now think of boundaries as meeting grounds, and not just places of conflict and inclusion/exclusion, enforced national consolidation, migration, dispossession and displacement (see Garbutt et al. Citation2012). Indeed, this is what Critical Arts has offered during the last decade. An article on Nepal (O’Neill Citation2012) examines how migrants recover their lives that extend beyond a landscape on which their cultural history has been inscribed. Jacobson (Citation2012), as does O’Neill, deals with the nature of the encounter in bottom-up historiographies. An article on Sri Lanka analyzes television commercials, promoting prominent cellular phone network service providers that were telecast, with a view to grasping how intertextuality becomes a live social process and how it is connected to ideology and localization in advertising (Nath and Liyanage Citation2015). These kinds of grounded topics tend to be missing from our submissions from China.

However, moving from what was basically a national to a regional African and then an international journal took nearly a decade. The end of apartheid meant that we had to rethink our objectives, as having sided with anti-apartheid forces, that struggle had been won. In the West, the shakeup of publishing models and consolidation of small into big publishing firms, the entré of key indexes and the new global best practice regimes, required the kind of strategy suggested by Ang.

Ang’s description of borders as sites of intercultural and symbolic contact explains exactly the South African and Chinese experiences after the end of the Cold War. Both societies opened up, China earlier than did South Africa, but both now seem to be looking inwards, South Africa though now much more so than China. Both tend to be xenophobic. India, however, remains the wild card in that it remains not only culturally but also geographically bounded, and unlike, with China’s scholars, only a handful of resident Indians have submitted articles (see Devadas Citation1996; Prasad Citation2012; Sarma Citation2012). However, Damodaran and Sitas (Citation2016) weave together the historical journey of a set of lament-like musical tropes from the seventh century AD to the 15th, tracing the commonalities in composition and performance. They argue that key to this transmission were Indian women in servitude or slavery, and they explore the role of Africans in this long-distance transfer of symbolic goods. Of contemporary relevance is Ngema and Lange (Citation2020) whose reflection on Indra practice and the use of arts for social change in the Global South is related to critical questions and the on-going discussions about cultural literacy.

Following the earlier appointment of two Chinese editorial board members, Shi-xu and Doreen Wu in 2011, the journal saw an upsurge of submissions from China, including Hong Kong, following a single earlier study from Macao (Kelen Citation2009). The first special issue from China was edited by Wu and Mao Sihui (Citation2011) on “Media Discourses and Cultural Globalisation: A Chinese perspective” (see also Cheng Citation2021). Articles on development strategies (Jiang Citation2022) were followed by additional studies and the edited volume Brand China in the Media, drawn from previously published articles in Critical Arts (Cao et al. Citation2020).

The bulk of Chinese unsolicited contemporary submissions to Critical Arts tend to apply technical discourse analyses, corpus approaches and translation theory via discrete case studies involving China-Western comparisons involving trade disputes, issues of national news representation, political congresses, grammatology, metaphors, utterances and phrases, in the context of “soft power” being a diplomatic strategy rather than in terms of its description by Western scholars as a form of hegemony (see Cao Citation2011; Du Citation2021; Riva Citation2017; Song Citation2021; Wang, Humblé and Chen Citation2020). In analyzing these technical methodological preferences Jun Zeng, an editorial board member, makes the point that they tend to be formulaic, in our terms “repetition with difference”, offering a set of discrete fly-on-the wall studies that would seem to drive the publication of administrative applications rather than offering transformative critique, which was the objective of the earlier generation of Chinese scholars. Min Liu’s (Citation2019, 13) fascinating and revealing study of how Tibet is constructed in the Western media, concludes rather self-evidently, for example, that this “study can contribute to the growing literature of using CI [corpus linguistics] in CDA [critical discourse studies].” The actual findings are useful if related to the wider context of how Tibetans themselves engage with both Western and Chinese representations of themselves.

However, of a different, more recognizable order for Critical Arts was the theme issue on “Thinking on the Research Methods of Dialogism in Chinese and Western Literary Theories” edited by Jun Zeng (Citation2020). This trajectory is found more integrally within British and Western European cultural studies and literary derivations, in which the objective seems to be trying to make sense of the West trying to make sense of China (Cheng Citation2021; Fu and Wang Citation2022; Tomaselli and Du 2018). The negotiation through modernity and ethnic representation and beyond of identity and class determination follows such projects (Cao and Wu Citation2017; Ding Citation2017; Weber 2017). Studies of film abound (Dong Citation2023; Luo Citation2023; Yang Citation2014; Yu Citation2020b), especially on Disney’s Mulan (Artz Citation2004; Xu and Tian Citation2013); and with regard to film theory, see Yu (Citation2020b); on the relationship between neoliberalism, precariousness and creative economy, see Lin (Citation2020); and science fiction, Wu (Citation2020a).

The reasons for the increase of submissions from Chinese authors, we suspect are: (a) our journal is indexed in the Web of Science, a key criterion for research recognition in China; (b) the extraordinary promotion of the journal by Doreen Wu and Mao Sihui through the International Association of Intercultural Studies and from all our Chinese board members and authors like Huimin Jin through the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) from 2016 and the institutions to which Tomaselli had been invited; (c) the co-incidence with the Chinese “going abroad” foreign policy that included a national academic emphasis on the English language that had reached its height between 2010 and 2019 (see Wu and Ng Citation2011); (d) the unbated thirst by Chinese humanities scholars for conceptual integration and dialogue with Western philosophical thought (see Zhou Citation2020); and (e) perhaps insufficient capacity by existing Western journals to absorb such high volumes of Chinese authored articles.

Critical Arts thus finds itself navigating its African origination in relation to Asian concerns. In addressing what could become a bifurcated outcome Handel Wright and Yao Xiao (Citation2020) undertook a survey of over 100 contributions on African Cultural Studies previously published in Critical Arts and other scholarly venues. Just as Africa is extraordinarily diverse, so is Asia, and indeed, as is China itself. We now have two sets of thematic analyses within the pages of our journal that could be brought into something of a dialogue via the prism of cultural and media studies. The point of this essay is to offer a manifesto for Asian authors choosing Critical Arts as a venue for publication. Critical Arts has always aimed at “making a difference”, especially mobilizing textualization and activism, and its central concern has been on democratization and engaging with the lived world.

In now orientating a more contextual way of doing cultural studies in Asia – and the Chinese context (China itself and the complex Chinese diasporas and the multiple interfaces in-between), we recognize the contours of our deeply conjunctural and problematic project (see, e.g. Cheng Citation2021; Hou Citation2021; Liu and Lin Citation2021; Lowe and Ortmann Citation2022; Song Citation2021; Wang and Ma 2022; Zhang and Wu Citation2017). Some of the problems/questions on which we have been pondering are itemized below.

First, is the question of “North/South/East/West”, the interhemispherical relations within which Critical Arts now places itself. How does China see itself in the world, geopolitically, culturally, and epistemologically? In the educational context, the past two decades of higher education development in China have witnessed an increasing number of international students coming from Central Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and from various African countries. China (and specifically its educational system and labour market) seems to be very keen on capitalizing on cultural power, as an emerging centre of knowledge production and generator of cultural capital in Asia. In this process, however, China seems to be internalizing some kind of Orientalism that exoticizes both itself and “Others” in Asia who have long been subjects of British, French, and American Orientalism. By holding onto certain kinds of epistemological frames, value systems, and institutional practices, such internalized OrientalismFootnote1 tends to centre/re-centre the West. This is done, for example, through prevalent Western theorization and representation of knowledge systems taught and applied in humanities and social sciences. Greater value is attached to Western higher education credentials, and to publishing in Western (Anglophone-centric) journals. The gigantic Chinese market/industrial complex of UK-authorized and US-authorized English language standardized tests such as IELTS and TOEFL are contributors to hierarchies of value. Many urban middle-class parents desire and strive to register their children in international schools or schools with connections to international study programmes – mostly to UK, USA, Canada, Australia, etc.

Notably, with the global outreach of cultural China, the One Belt One Road (OBOR) or Belt & Road development strategy – now into the second decade since its initiation in 2013 as a soft power strategy – has created new diasporic networks and transnational landscapes of representation of Chineseness (see Fang et al. Citation2021). This occurs in the context of infrastructure building, capital investment, and controversies around global “land grabbing” (Hwang and Black Citation2020; Mora Citation2022; Xu Citation2018) which situates China more deeply and expansively into the already imperialist capitalist world development order. Sometimes a sense of Han-Chinese cultural superiority, expansionism, and ‘civilization’ assumptions (through the establishment of Confucius Institutes, for example) is constructed in conversation/contestation with the United States’ imperialist development logics and hegemony. How does this new context inform old and new ethnocultural identities? In China itself, there has been “a gradual abandonment of the use of Marxist shibboleths in propaganda, and their replacement by Confucian adages … ” (de Burgh and Feng Citation2017, 146). Some other manifestations are those from the older and more established Sinophone diasporas (e.g. centuries of Sinophone network and migration in East Asia and Southeast Asia), and those from the relatively new migrations with much more technological access and closer ties to Sinophone media (e.g. contemporary Chinese migrant workers and expatriates in Africa). Although in many of these and various other contexts (e.g. Asia, Africa, Americas) both historical and nascent streams of Chinese diaspora exist, how can one think about diasporic Chineseness on Indigenous lands? What are the multiple, changing relations between the Sinophone diasporic and China?

Re-orienting China and Chinese-ness also means re-visiting and re-theorizing part of what “Global South/North” means and part of what “The East/The West” means (see Chapman Citation1997; Tomaselli and Du Citation2021). In the Chinese mediascape (especially the state-sanctioned mainstream narratives), China no longer projects itself as part of “The Third World”, or “The Developing World”, or “The Global South”. Concomitantly, “The East” seems to be an ostensibly stable category through which China articulates itself, with discourses such as 中国梦 zhongguo meng (Chinese Dream),Footnote2 and 中华民族伟大复兴 zhonghua minzu weida fuxing (Great Rejuvenation of The Chinese Nation) against the imperialist West culturally and geopolitically. These are entangled with civilization narratives and metaphors centred on Han epistemologies, sometimes to the point of reproducing stereotypical binary notions of culture and “race” at the expense of those who are misrepresented as “underdeveloped” and in “The Third World”. Today, it seems that the Chinese context might yield important insights into the changing historical-cultural conjunctures between East/West/North/South, and into potential movements beyond binaries.

Second, is the question of decoloniality vis-à-vis Han Chineseness. One of the most noted dialogues on Han Chinese decoloniality, in contemporary China, has been revolving around de-Westernisation through the articulation of Chinese nation emerging out of semi-colonization under imperial forces. This involves revisiting Chinese 国学 guoxue (National Culture) such as the study of Taoism, Confucianism, guqin, ancient Han language, etc., to approach indigenous Chinese epistemologies. Nevertheless, what remains relatively underdiscussed and deserves more critical reflection is the question of de-Sinicization vis-à-vis Han supremacy which begs deeper questions around ethnicity and Indigeneity within the complex construct of Chinese-ness and Chinese nation. The multiethnic body politics of Chinese-ness as 中华民族多元一体 zhonghua minzu duoyuan yiti (Diversity in Unity of The Chinese Nation) – through the anthropological and sociological work of the Han scholar Fei Xiaotong – has been incorporated by the state as the mainstream narrative on Chinese nationality. To what extent, then, could we create more (radical and fluid) spaces that empower the articulation of incredibly nuanced, complex, and different non-Han worldviews and ways of being that are not centred on Han narration of historiography, literacy, culture, spirituality, and political economy? In cinema, for example, there has been, and arguably still is, the production of ethnic minority films which reproduce the Han gaze on peoples who have been ethnicized and “included” into the 中华民族 zhonghua minzu (Chinese Nation). This gaze operates in the larger context of Sinicization where Han cultures (and Han-centred political economy, legal system, and epistemologies) dominate and overdetermine how non-Han folks might articulate their different relationships to the land, to the society, to their histories, to their communities, and to themselves.

Another example would be the political administrative construct of ethnic minority autonomous governments across different levels from the provincial-status, largest “autonomous region”, to the lower administrative-status and smaller “autonomous prefecture” and further to “autonomous county”. While on surface this might speak to the ethnocultural and demographic dynamics in these areas, with several ethnic minority policies on representation in government, employment, and access to higher education, the deeper questions have always been to what extent this empowers the local peoples (who have been variously ethnicized and minoritized) in affirming their histories and cultures, and expressing who they were, who they are, and who they want to become.

While many of these power dynamics continue, our hope is to carefully generate and hold space for more reflexive, multi-modal dialogues on decoloniality (i.e. de-Westernisation, de-Sinicization, non-Han articulation of alternative identity and indigeneity) vis-à-vis Han Chineseness (i.e. Han/non-Han ethnicization, Han/non-Han “integration”, Han supremacy, Han-ness, different levels/processes/power dynamics of Sinicization). Related to the Han-Tibetan-Western triad, for example, Ming Liu’s (Citation2019) analysis offers a corpus-assisted discourse analysis of how Tibet was represented in five Anglo-American newspapers between 2000 and 2015. Tibet was either constructed as being under atheist totalitarian rule or and being “objects of gaze” with regard to mythical and exotic religious practices, eliding the “intrusions of dominant Western countries” (13). Applying Stuart Hall’s theory of identity, Han (Citation2017, 50) examines the idea of identity dilemma with regard to Chineseness and Americanness in a cosmopolitan world. The dialogical relationship is “between being and becoming, between the past and the present, between homeland and diaspora, as well as being between the local and the global”. As Jieyun Feng and Yanan Li (Citation2017, 109) observe in a domestic context with regard to heritage tourism, those “visiting the Great Wall are far more impressed by the modern facilities and services than by its history and culture”. While de-Westernisation consists of one important dimension of decolonial dialogues and spaces, more nuanced work would be needed to unpack Han-Chineseness and the multivalent processes of (de)Sinicization.

Third, is the question of racism and racialized identity (see Liu and Deng Citation2020). Since the 2000s, there have been various formations of diasporic African communities of merchants/traders/migrant workers in Guangzhou – a city that has been hosting the biannual China Import and Export Fair since 1957 – and most recently, in Yiwu – a city known for its productivity in the global nexus of small commodity trades. The logic of othering occurs in reverse also, expressed as the “China threat” in David Katiambo’s (Citation2019) study of newspaper reportage of fish imports from China into Kenya and the popular Kenyan association of China with fakes. Katiambo explains how international trade is part of the process of fixing public meaning. This study on a “food scare” moral panic is supplemented by Fan Yang’s (Citation2016) earlier narrative about Faked in China that traces the interaction between national branding and counterfeit culture, as China tried to gain legitimacy and membership of the World Trade Organisation in 2001. The branding was captured in the phrase, “From Made in China”, as a manufacturer of foreign goods, to “Created in China”, eligible for global intellectual property rights protections. In contrast, is Hou’s (Citation2021) analysis of A Bite of China, a documentary series whose “food as method” (120) to construct national identity is designed to “evoke people’s collective memory aspects of tradition within Chinese cultural continuities.”

Racism became quite obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, anti-black and anti-African racism evidenced deep structural issues and everyday realities beyond the official government narrative of China–Africa relations (e.g. the media, the formal education, the immigration policy, the urban planning, etc., which involve racist, sexist, and classist profiling) (see Liu and Deng Citation2020). Most recently, Hangzhou-based South African scholar Ke -Schutte's (Citation2023) work Angloscene unpacked the complex experiences of diverse African and Chinese students with their language-mediated and race-mediated interactions in higher education contexts. This study of language, race, cosmopolitanism, mobility, and subjectivity – through contemporary ethnographic and archival historical work on Africa–China educational encounters – offered a nuanced and insightful analysis of how the interwoven pedagogical, communicative, economic as well as symbolic power dynamics of English language not only complicated the meanings of African-ness, Black-ness, Chinese-ness, and Whiteness, but also (re)constructed place-based, social network-based, gender-based, and linguistically-culturally-inflected racialized hierarchies, standing quite contradictory to a futurity that is imagined to be more horizontally cosmopolitan. Given this and various other conjunctures of anti-Black, anti-African racism coupled with Islamophobia in China (e.g. even the historically more trusted and integrated Chinese Muslim Hui is now subject to tightening state surveillance and control), what should be the anti-racism initiatives/policies, especially in relation to the racism directed towards/faced by black Africans, Muslim Africans, black Muslim Africans, among various racialized groups?

Both Chinese and English media reports have revealed that some children of African migrant workers in Guangzhou have had a hard time finding a place in the local educational system. This system has evolved into a complex multiple-tiered structure – the public schools require 户口hukou, or the Chinese household registration document which many of these children do not have. The elite private schools are too expensive and only accessible to children of diplomats/expatriates/government officials/business elites, while the more affordable private schools are very competitive and have limited seats. The mechanisms might vary across elementary schools and secondary schools, or some private schools might become institutionalized as public schools, or in some exceptional cases some children will be accepted in private/public schools. But, in all these variations, the main question is the lack of genuine respect, understanding and empowerment of these children as residents who deserve a place in the process of urban planning and educational planning.

Part of that reality of racialized relations includes, although not common, the formation of relationships, partnerships, and families between the Chinese and diasporic Africans (each with enormous complexity). In these relationships, there are already “mixed-race” children – who might speak fluently in any combination of Cantonese, Mandarin, Igbo, Swahili, etc. – yet facing uncertainties (at best) in everyday life and institutionalized space, as well as stereotypes (quite often) in media representations. Oftentimes “mixed-race” is romanticized, in the specific senses of privileging the kind of Chinese-ness mixed with elite Eurocentric whiteness, and/or valorizing relations to the Blackness of African-American athletes rather than the Blackness of ordinary Black African migrant workers. Will there be a new localized, ethnicized categorization of mixed Chinese-ness entangled with African diasporas? In the future, where will Afro-Chinese children/youth belong?

Fourth, is the question of queerness and representation. What might queer liberation sound like/look like in the Sinophone contexts? What are the Chinese representation, theorization and practices of queerness? Considering queer media, identity, and power (e.g. cinema, music, dance, TV, social media), one might move in a (transnational) mediascape created by, on the one hand, independent queer cultural work (sometimes public, sometimes underground) for community-building and queer/non-queer collaboration, and on the other hand, state-sanctioned mainstream commercialization and consumption of queerness in entertainment industry (e.g. filmic productions), especially since the early 2000s. There is progress, as select queer visibility and recognition are present through the state/industrial acceptance and cooptation of a few urbanized, upper-middle class celebrities such as Jin Xing (a famous dancer and a talk show host in China), Cai Kangyong or Kevin Tsai (a writer, producer, and talk show host from Taiwan who has hosted several popular TV shows and has published several bestsellers in China), and the late Leslie Cheung (a Cantonese-Hong Kong singer and actor whose work has attracted a global fandom).

And yet, however rosy this select ‘visibility' might seem, the moral/legal affirmation of humanity, the adequate access to institutional spaces (from marriage/family formation to anti-discrimination in employment, education, healthcare and housing), and the freedom to express/move in public spaces, have not been the lived realities of most ordinary LGBTQ folks. This diverse community faces/confronts a spectrum of discrimination. These include, for example, heteronormative gaze and stigmatization to a lack of representation in school curricula and pedagogies. Attending to the school experiences and mental wellbeing of LGBTQ students in Mainland China, Wei and Liu (Citation2019) did an online survey with 732 LGBTQ students (from high school to graduate school). The authors suggested “a more inclusive school climate and more school resources, especially a positive LGBTQ role model” (192), in response to the survey results that many students remained closeted with their siblings/parents/teachers and were at great risk for psychological distresses. Examining the agency of queer teachers in Chinese universities, for example, Le Cui (Citation2022) interviewed gay academics and learned about how their pedagogies might challenge heteronormativity in classrooms – that in the context of largely unfriendly and repressive campus climate and curricula, the closeted gay teachers’ agency is “located between the extremes of conformity and subversion”.

A whole spectrum of realities – from the lack of protection from discrimination in labour market, housing, healthcare and social-cultural services to the state-sanctioned policing and capitalist appropriation of queerness for consumption market – are further concerns. We are deeply interested in how people would/could move in this direction through everyday practices and resistances; in the meantime, we are also interested in the concomitant direction of Chinese queer theorizing, in ways that might de-Westernize queer theory. On the one hand, there is a foundation on which more Chinese context-sensitive queer theorizing could be built – drawing on the rich histories, cultures, and contemporary changes in the landscape of Chinese gender and sexuality culture, moral normativity, self-representation, identification, and ways of being and relating, through a careful and critical reflection on the work by scholars such as Li Yinhe, Pan Suiming, Cui Zi’en, and Tan Jia (e.g. Bao Citation2022; Cui Citation2008; Tan Citation2017).

On the other hand, in the work of some of these scholars, as well as in much of the contemporary queer literature since the 1980s, the articulation of queerness (especially in the positive affirmative sense) – remained heavily influenced by Western theorization and conceptualization, albeit with critical creativity. For example, the Chinese term ku’er is a transliteration of “queer”, lala or lazi of “lesbian”, while tongzhi (same-sex orientation) signified creative appropriation of the twentieth century Chinese nation-building as well as Marxist class-struggle term “comrade” – first through the creative projects of a Hong Kong artist Edward Lam in the late 1980s. Beyond the question of translation (see Song Citation2023), it is also a matter of epistemological framing/re-framing, in the context where knowledge production/flow seems to be unidirectional from the so-called Global North to Global South – including queer theory which also situates in the context/shadow of historical imperial domination. This issue has been highlighted, for example, in an essay Beijing meets Hawaii where the author Tan Jia (2017) reflected on dialogues between Chinese queer cinema and the work of educator/filmmaker Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu who is a Hawaiian māhū. In both theories and practices, we are thinking about questions like: How to generate a more grounded theory of queerness in China, and for whom and what purposes? What are the works of Western scholars such as Michel Foucault and Judith Butler doing in theorizing Chinese queerness, in what productive ways and with what limitations? What might queer liberation sound like/look like in China? Be it in media representation or in theorization, what are the small everyday acts of queer resilience and moments of joy and hope?

Fifth, is methodological preference for discourse analysis. One of the issues that the journal’s editors have been wanting to analyze is the almost unique penchant for our Chinese authors (with the exception of authors from Shanghai University, Shanghai Jaio Tong University and CASS) to the endless use of an instrumentalist discourse analysis, whose publication patterns are sketched by Wang and Sun (Citation2023). What started from 2016 as a few such submissions has now become a flood, with very little new being said, with no discernable interrogation of methodology, conceptual development or theorization of Chinese conditions evident. These many and bounded case studies, however, attract high readerships, even as they say very little about epistemology, cultural studies or methodology. The extensive universal use of discourse analysis is possibly a defensive mechanism on the part of China-resident scholars who are trying to engage in a kind of covert critique without alerting the powers that be to the much deeper issues with which Western cultural studies is concerned, and as we argue here are of relevance to China. Critical Arts is one of the few Western journals that is making systematic space for Chinese cultural studies, and the Asia-Africa interface as a growth area. We have published some work that is critical, for example on the very different framing of disobedience separating Western and Chinese news media in Hong Kong (see e.g. Lowe and Ortman Citation2022; Wang and Ma Citation2021), and we have employed our resident Chinese board members as reviewers of these papers, amongst others from elsewhere. So, there is a grounding on which we can build.

Sixth, is the question of the relations between the people and the state – how the state’s gazes are operating in ways that define the “good”, the “bad”, and the “unspeakable/invisible”, and how different citizens and communities are adapting to/appropriating/transgressing those definitions. The new “Three-Child Policy” exemplifies the operation of the state’s heteronormative-patriarchal gaze, in defining what is “good”, through the institution of marriage and family. This policy (2021), promulgated not long after the “unsatisfactory” promotion of Two-Child Policy (2015), primarily aims at increasing birth rate and the reproduction of industrial labour for capitalist production, in the context of aging populations, insufficient provision of social welfare, and class divides where many working class adults – born as the Only-Child Generation under the One-Child Policy (1979) – simply cannot afford to take care of their aging parents. Imagine, for example, a scenario where a working class wage labourer without any siblings would need to take care of their parents, or a married couple needs to take care of four seniors, besides their own children, if any, oftentimes also intertwined with the cultural norms of filial piety. Behind these, in fact, were decades of disciplining women’s will, body, and choice, and men’s, with the state’s heavy-handed One-Child Policy which has rarely empowered women’s decision-making in their sexual and reproductive health, but also has seriously led to, in a system of patriarchy, forced abortion and gender-selective abortion/female infanticide.

When it comes to how the state defines “bad”, the contemporary cultural stigmatization and legal punishment of sex work in China deserves further critical reflections. Li Yinhe, one of the leading sociologists in China, has argued for basic human and labour rights of sex workers, such as the access to safe space, the access to healthcare, the right to work, the right to exist with dignity, etc. (see Cochrane and Wang Citation2020). With what assumptions and purposes does the state (from the central to local levels) regulate sexuality, labour, markets, and justice, when the existence of the sex industry is an open secret? How does the media (from mainstream to relatively independent sources) look at and represent sex work, with or without conflation of human trafficking and sex work, with or without reproducing stereotypes of sex workers? And above all, how do sex workers themselves – women, men, non-binary people – tell different stories, create and construct a culture which sustain them, and speak for themselves?

Beyond “good” and “bad” under the state’s gazes, we wonder whose self-determination and self-expression would be considered “unspeakable” or rendered “invisible”. While structural issues of policing, censorship, and the justice system are an indispensable dimension in thinking critically about the state, we are also interested in learning more about the everyday cultural expressions, acts of resistance, small movements, ways of being resilient, and nuanced grassroots community-building (see e.g. Yu Citation2020a). And we do note that instances of resistance and identification (Huang Citation2014), freedom of speech (Chen and Zhang Citation2011) and censorship (Luo and Ming Citation2020) are always bubbling below the surface and are always factors to be taken into consideration anywhere. Some of these power contestations and changing representations could be observed in education. Haifen Hui’s (Citation2022) study, for example, analyzes the rationale of the recent nationwide textbook replacement in China, and argues that “the reform can partly be regarded as a corrective measure taken to adjust the inculcation of national identity, patriotism and citizenship” (113). In light of the 2019 Hong Kong protests, Hui (Citation2022) considers the “riot” has its “deep cause in elementary and middle school education even decades before it happened” (124), and what happened in Hong Kong (long before 2019) could be a partial catalyst/rationale for the state’s large-scale school textbook replacement in Mainland China. In the process of nation-building and subject formation, what laws could be modified, what kinds of books could be read, and what kinds of music could have a voice? What kinds of folk memories emerge (see, e.g. Hu Citation2019)? What are the lines being drawn? When, where, how, who, and why?

Seventh, is the question of new identities expressed by new generations and youth in China, i.e. 00后 [00 hou] (the post-00s generation born after 2000) and 10后 [10 hou] (the post-10s generation born after 2010). We are interested in at least three dimensions and sub-questions. One, how do the new generations live with the new media including social media, and with broadly the innovation of digital communication technology? (see, e.g. Lin and Zhao Citation2021). For example, how do we make sense of the making of 网红 [wang hong] (online influencers) on various digital media platforms, including the original Chinese version of TikTok, or Douyin (literal meaning “trembling sound” or “trembling voice”)? (see Weber Citation2011). How should we understand the whole spectrum of voices and agency, from the community-making and gig economy where some disabled youth, queer youth, and youth of modest family backgrounds are able to claim some space to share their everyday stories? How can they create networks and generate some income through advertisements and audience support? How do we make sense of the live streaming economy where influencers and celebrities could make a significant amount of money by being a middleperson and recommending various merchandises to millions of live stream viewers/consumers, with “discounts”? These questions differ from the literary studies that have been recently published, as indicated by You Wu’s (Citation2023a, Citation2023b) study on Internet literature, which enables a new form of literary expression based on interactivity, hypertextuality and multimedia. A special issue edited from Shanghai by Jun Zeng and Siying Duane on the metaverse elevates analysis beyond the discourse and linguistic methodologies (see, e.g. Chen Citation2023). More down to earth is a study of wushu martial arts, which has become “a remarkable part of modern popular culture present in the context of cinema, computer games, social networks” (Xue et al. Citation2023, see also Yang Citation2020).

How might these changes bring people together, and/or create new divides? Crossing class lines that are so embedded in the socioeconomic and educational system, crossing rural/urban divides that tend to be relentlessly widened through regional planning where the power of decision-making is concentrated and urbanized, and crossing the material gaps that benefit some at the expense of others – all these experiences/dilemmas/acts/aspirations of crossing are part of the making of the new generations (especially those from underprivileged families). What could be learned from their expressions of who they are, the society they live in, and the kinds of human beings they want to become? For example, many post-00s youth are talking about 躺平[tang-ping] – beyond laid-back and simply “lie down” without any motivation, and佛系[foxi], or “The Buddhist Way” – using and appropriating Buddhist vocabulary to articulate the difficulties in transcending intergenerational material and social divisions. Even the youth from relatively comfortable urban middle class families are complaining about fierce competition and resisting 内卷 [nei-juan], the phenomenon of endless social mobility contestation like rat race. How do we listen more deeply to – and to what extent do we understand – the voices of the三和Sanhe Youth? While Sanhe is the name of a precarious migrant labour recruitment centre in the global metropolis of Shenzhen, it is a name that symptomatically describes the condition of the migrant youth who dropped out of schools, looked for housing, and found precarious gig work through the urban labour markets and many other places. It is a quite saddening term, among many others, that reflects the disillusion of a whole new generation – many from rural towns and villages; many are children of migrant workers and small peasants, some of whom remain resilient and optimistic, while some might have lost hope.

Last but not least, we wonder if there is, culturally, a new and long revolution underway. What are the cultures and ways of life that the new generations and youth are making, with the new media and digital technologies available? What are their processes of re/articulating and re/creating what life means in quotidian lived contexts? What transgressions might be possible, and whose identities and cultures, after all, are being forgotten in debris and/or shaping the directions where the society moves? Modestly, we are asking these questions with uncertainty, ambivalence, and hope.

Eighth, is the lack of equivalence of class configurations. Where capital and class are obvious bedfellows in the West, in China there was a distinction between the elite and the masses, though their boundaries were somewhat less clear or stable than those in capitalist countries. A fluid system enabled periodic cycles of inter-class upwards and downward circulation, thus the elite and the popular groups could contain each other (Zhou-yue Citation2012, 36–39). Since in the West popular resistance was understood primarily to be a social expression of class oppression, in China the scholar has to understand the work, culture and lifestyle of the New Workers (including those in rural areas), “the social underdogs who are most severely exploited by the capital accumulations and market rules in China” which nevertheless claims the status of a socialist state. These differences obviously need to be addressed in light of how the different class structures operate in their respective political economic environments.

Conclusion

In the spirit of critical dialogue, collaboration, and reciprocity, we work modestly and wholeheartedly for inter-hemispheric perspectives-sharing and knowledge production. Two questions remain the heart of the matter in such work. One is the politics of representation, in which transnational and transcontinental dynamics are complicating the already significant politics of differences in class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, religion, spirituality, language, nationality, age, and many more. Rather than issues of/about the “minorities” (and who are the quintessential “mass” or “majority” anyway?), these are questions around normativity, subjectivity, minoritization, and ordinariness in which everyone has a stake, in different ways, with uneven positions. In particular, the colonial legacies and ongoing neocolonialism (e.g. political, economic and cultural) on both the African and Asian continents constitute one of the most burning questions of representation, that is, how to de-Westernize and decolonize relationships to the land, to knowledge, to each other, and to ourselves?

Conversely, and alongside geopolitics, the mediascapes of these representations are changing. New media (especially social media) has informed new ways of expression, culture-making and community-building. It generates every day new and analogous forms of power, where the subaltern/subordinate/marginalized might speak and connect to each other, where the privileged/dominant/elite might profit from and reproduce dominant discourses, where the states might employ new technologies of surveillance, and where gigantic consumption markets might emerge.

Another question is how to take seriously the relationship between text and context. Since cultural formation is almost always already embedded in power differentials and contestations, as culture is inseparable from community and society, what, then, are the changing societal contexts, terrains, and conjunctures that situate the (constant movements and infinite arrays of) signs, symbols, ideologies, feelings, and in general, texts? How does the meaning of the text speak/translate to the meaning of its context?

So, what’s to be done with discourse and corpus approaches? Have they simply become a template, and a distancing objective method in which researcher position is silenced, to be applied to anything and everything, without the ethical keystones required by cultural studies, following Karl Marx, not only to study the world, but to change it for the better. This ethic is underlined by Feng, Chen, and Zheng (Citation2016, 706):

Being aware of social class does not necessarily entail labelling or stigmatizing people, but rather knowing what is possible and how to change it or improve one’s situation. Thus, the real meaning of sociology is not merely to interpret or explain social phenomena and problems, but to rather play a more active role in society, for instance by guiding less advantaged groups and protecting their rights, interests and capacities … . [and] boost their confidence and moral[e], and eventually supply the needed motivation and enthusiasm to improve their existing conditions and strive for better lives.

To end, we find ourselves in dialogue with Stuart Hall (Citation1983) who – revisiting the formation of cultural studies (as quoted in Slack and Grossberg Citation2016, 11) – asked: “Where is this society going? What is happening to culture?” Forty years later, today, we re-articulate these questions, with a decolonial, transnational, inter-hemispheric and global sensitivity, and still with hope: Where is your society going? What is happening to your culture? Does cultural studies matter?

For us, and for Zhou-yue (Citation2016) and the generation he was reporting on, yes, cultural studies does matter, no matter from where one is working. However, we need to keep our eyes on the ball and ensure that the field’s raison d’être is always foregrounded, as we have tried to do in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Scholars such as Louisa Schein (Citation1997), for example, unpacked the power dynamics of domination in the construction of exoticized, non-Han, minoritized, ethnicized rural working women in China through ethnographic studies (in particular with the Miao people in the 1980s) and suggested an important concept “internal Orientalism”. Although the author/ethnographer/researcher’s own positionality reproduced certain dynamics of Orientalism, this idea that Orientalism could be internalized to produce stereotypical non-Han, gendered, classed, and spatialized “Others” in both structural and everyday ways that reinforce and recentre Han-Chinese-ness was insightful. This conceptualization of “internal Orientalism” is more relevant to our second question around decoloniality vis-à-vis Han-Chinese-ness. Our concern around internalization here, for the first question, is more about the international, inter-continental, and inter-hemispherical context of Chinese-ness.

2 In this article, for terms used in the context of mainland China, simplified Chinese characters and Mandarin pinyin spelling system are used, followed by English translation in the brackets. Readers should also note that there are multiple ways of writing and spelling Chinese characters, as well as multiple languages related to Han-Chinese-ness.

References

- Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). 2019. Report on Grouped Peer Review of Scholarly Journals in Communication and Information Sciences. Available online. https://doi.org/10.17159/assaf.2019/0041.

- Ang, I. 1996. “Introduction.” Critical Arts 10 (2): xx111–xxvii.

- Artz, L. 2004. “The Righteousness of Self-Centred Royals: The World According to Disney Animation.” Critical Arts 18 (1): 116–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560240485310071.

- Bao, H. 2022. “Ways of Seeing Transgender in Independent Chinese Cinema.” Feminist Media Studies 22 (5): 1278–1281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2077798.

- Buthelezi, M., and P. Vale, eds. 2023. State Capture in South Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

- Cao, Q. 2011. “The Language of Soft Power: Mediating Socio-Political Meanings in the Chinese Media.” Critical Arts 25 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2011.552203.

- Cao, Q., and D. Wu. 2017. “Modern Chinese Identities at the Crossroads.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1405456.

- Cao, Q., D. D. Wu, and K. G. Tomaselli. 2020. Brand China in the Media Transformation of Identities. London: Routledge.

- Chapman, M. 1997. “South Africa in the Global Neighbourhood: Towards a Method of Cultural Analysis.” Critical Arts 11 (1-2): 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560049785310041.

- Chen, C. F. 2023. “Literary Theory and Cultural Practice of ‘Metaverse’ in China.” Critical Arts 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2269238.

- Chen, K., and X. Zhang. 2011. “Trial by Media: Overcorrection of the Inadequacy of the Right to Free Speech in Contemporary China.” Critical Arts 25 (1): 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2011.552207.

- Cheng, X. 2021. “Media Construction of China: A Review of Relevant Studies.” Critical Arts 35 (3): 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1985551.

- Cho, S., and J. Y. Chung. 2009. “We Want Our MTV: Glocalisation of Cable Content in China, Korea and Japan.” Critical Arts 23 (3): 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560040903251076.

- Cochrane, D., and J. Wang. 2020. “Vision Without Action is Merely a Dream’: A Conversation with Li Yinhe.” Critical Asian Studies 52 (3): 446–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2020.1768132.

- Connell, K., and M. Hilton, eds. 2016. Cultural Studies 50 Years on. History, Practice and Politics. London: Roman & Littlefield.

- Cui, Z. 2008. Queer China, ‘Comrade’ China [Documentary, 60 minutes, Mandarin with English subtitles]. dGenerate Films.

- Cui, L. 2022. “‘Teach as an Outsider’: Closeted gay Academics’ Strategies for Addressing Queer Issues in China.” Sex Education 23 (5): 570–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2103109.

- Damodaran, S., and A. Sitas. 2016. “The Musical Journey – Re-centring AfroAsia Through an Arc of Musical Sorrow.” Critical Arts 30 (2): 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1187792.

- de Burgh, H., and D. Feng. 2017. “The Return of the Repressed: Three Examples of How Chinese Identity Is Being Reconsolidated for the Modern World.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1408665.

- Devadas, V. 1996. “(Pre)Serving Home: ‘Little India’ and the Indian-Singaporean.” Critical Arts 10 (2): 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560049685310141.

- Ding, S. 2017. “Articulating for Tibetan Experiences in the Contemporary World: A Cultural Study of Pema Tseden’s and Sonthar Gyal’s Films.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1407808.

- Dong, W. 2023. “Drifting Between Paris and Beijing: Transnational Cityscapes in Lou Ye’s Sino-French Film Love and Bruises (2011).” Critical Arts 37 (2): 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2218451.

- Du, L. 2021. “Different Discursive Constructions of Chinese Political Congresses in China Daily and The New York Times: A Corpus-Based Discourse Study.” Critical Arts 35 (5-6): 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2055593.

- Duan, S. 2020. “Yixiang (意象) in Contemporary Chinese Ink Installation art.” Critical Arts 34 (2): 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1679207.

- Feng J. Li, and P. Wu. 2017. “Conflicting Images of the Great Wall in Cultural Heritage Tourism.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 109–127. DOI: 10.1080/02560046.2017.1405455

- Fang, Y., W. Jiao, L. Feng, J. Liu, and X. Zhang. 2021. “A Comprehensive Evaluation of Urban Cultural Soft Power for the Silk Road Economic Belt.” Critical Arts 35 (2): 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1919163.

- Feng, B., J. Chen, and H. Zheng. 2016. “Who Are They? The Small and Micro Entrepreneurs in Yiwu and Cixi.” Critical Arts 30 (5): 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1262440.

- Fu, X., and G. Wang. 2022. “Confrontation, Competition, or Cooperation? The China–US Relations Represented in China Daily’s Coverage of Climate Change (2010–2019).” Critical Arts 36 (1-2): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2116466.

- Galliford, M. 2022. “Further Travels in “Becoming-Aboriginal”: The Country of Oodnadatta, the Importance of Aboriginal Tourism, and the Critical Need for Ecosophy.” Critical Arts 36 (5-6): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2148709.

- Garbutt, R., S. Biermann, and B. Offord. 2012. “Into the Borderlands: Unruly pedagogy, tactile theory and the decolonising nation.” Critical Arts 26 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1080/02560046.2012.663160

- Han, Q. 2017. “Negotiated “Chineseness” and Divided Loyalties: My American Grandson.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 59–75. doi:10.1080/02560046.2017.1405447

- Hall, Stuart. 1983. “Life and Times of the First New Left.” New Left Review no. 61, 2010. https://newleftreview.org/II/61/stuart-hall-life-and-times-of-the-first-new-left#_edn1.

- Hall, S., D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis, eds. 1980. Culture, Media. Language. London: Hutchinson.

- Harte, D. 2017. “Shanghai Cosmopolis: Negotiating the Branded City.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1405450.

- Hermes, J., J. Kooijman, J. Littler, and H. Wood. 2017. “On the Move: Twentieth Anniversary Editorial of the European Journal of Cultural Studies.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 20 (6): 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549417733006.

- Hou, Z. 2021. “Alibaba’s Media Empire Dream? A Discursive Analysis of Legitimacy Strategies Over Cross-Border Media Acquisition.” Critical Arts 35 (1): 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1887312.

- Hu, L. 2019. “Self-Portraiture and Historical Memory: Zhang Mengqi’s Documentary Practice.” Critical Arts 33 (2): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1671887.

- Huang, Y. 2014. “From ‘Talent Show’ to ‘Circusee’: Chinese Youth Resistant Acts and Strategies in the Super Girl Voice Phenomenon.” Critical Arts 28 (1): 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2014.883700.

- Hui, H. 2022. “China’s School Textbook Replacement and Curriculum Reform in the New Era of Globalization.” Critical Arts 36 (5-6): 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2189279.

- Hwang, Y., and L. Black. 2020. “Victimized State and Visionary Leader? Questioning China’s Approach to Human Security in Africa.” East Asia 37 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-020-09327-w.

- Jacobson, C. 2012. “Identity Papers, Lamas’ Books, and the Magical Essays of Lenin: Literacies of Desire and Exclusion in Nepal.” Critical Arts 26 (2): 208–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.684440.

- Jiang, Y. 2022. “A Systematic Literature Review of the Belt and Road Initiative in Australia from 2013 to 2021.” Critical Arts 36 (1-2): 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2112726.

- Jin, H. 2017. “Existing Approaches of Cultural Studies and Global Dialogism: A Study Beginning with the Debate Around “Cultural Imperialism.” Critical Arts 31 (1): 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1290666.

- Katiambo, D. 2019. “International Trade as Discourse: Construction of a ‘China Threat’ Through Fakes.” Critical Arts 33 (2): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1676281.

- Ke-Schutte, J. 2023. Angloscene: Compromised Personhood in Afro-Chinese Translations. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Kelen, C. 2009. “Crossing the Road in Macao.” Critical Arts 23 (3): 283–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560040903251035.

- Kim, G. 2014. “When Schoolgirls Met Bertolt Brecht: Popular Mobilisation of Grassroots Online Videos by Korea's Unknown People.” Critical Arts 28 (1): 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2014.883698.

- Lin, Z. 2020. “Precarious Creativity: Production of Digital Video in China.” Critical Arts 34 (6): 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1826550.

- Lin, Y., and Y. Zhao. 2021. “Dis)Assembling ESports: Material Actors and Relational Networks in the Chinese ESports Industry.” Critical Arts 35 (5-6): 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1986731.

- Liu, M. 2019. “New Trend, but Old Story: A Corpus-Assisted Discourse Study of Tibet Imaginations in Anglo-American Newspapers.” Critical Arts 33 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1583678.

- Liu, T., and Z. Deng. 2020. “They’ve Made our Blood Ties Black”: On the Burst of Online Racism Towards the African in China’s Social Media.” Critical Arts 34 (2): 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1717567.

- Liu, M., and L. Lin. 2021. “One Country, Two Systems”: A Corpus-Assisted Discourse Analysis of the Politics of Recontextualization in British, American and Chinese Newspapers.” Critical Arts 35 (3): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1985156.

- Lowe, J., and S. Ortmann. 2022. “Graffiti of the ‘New’ Hong Kong and Their Imaginative Geographies During the Anti-Extradition Bill Protests of 2019–2020.” Critical Arts 36 (1-2): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2071452.

- Luo, M. 2022. “Power and Identity Transition in Symphonic Music: Shanghai Symphony Orchestra from the 1920s to the Early 1950s.” Critical Arts 36 (1-2): 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2022.2066702.

- Luo, T. 2023. “Tradition, Transmediality, and Modernity: Representation of the Double in Chinese Modern Visual Culture.” Critical Arts 36 (5-6): 144–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2168024.

- Luo, M., and W. Ming. 2020. “From Underground to Mainstream and Then What? Empowerment and Censorship in China’s Hip-Hop Music.” Critical Arts 34 (6): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1830141.

- Milgram, B. L. 2012. “Tangled Fields: Rethinking Positionality and Ethics in Research on Women's Work in a Hong Kong–Philippine Trade.” Critical Arts 26 (2): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.684438.

- Mora, S. 2022. “Land Grabbing, Power Configurations and Trajectories of China’s Investments in Argentina.” Globalizations 19 (5): 696–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2021.1920197.

- Morgan, M. 2006. “Keynote Address: To Count or Not to Count in Communication Research. What Is the Question?” In Communication Science in South Africa: Contemporary Issues, edited by W. E. Fourie, H. Wasserman, and C. Muir, 11–23. Cape Town: Juta.

- Nath, D., and D. Liyanage. 2015. “Intertextuality and Localization in Contemporary Sri Lankan Advertisements on Television.” Critical Arts 29 (3): 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2015.1059553.

- Neilson, N. 1996. “Threshold Procedures: ‘Boat People’ in South Florida and Western Australia.” Critical Arts 10 (2): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560049685310121.

- Ngema, L. N., and M. E. Lange. 2020. “Pathways Indra Congress: Cultural Literacy for Social Change.” Critical Arts 34 (5): 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1839238.

- O'Neill, T. 2012. “The Heart of Helambu.” Critical Arts 26 (2): 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.684439.

- Prasad, P. 2012. “The Baba and the Patrao: Negotiating Localness in the Tourist Village.” Critical Arts 26 (3): 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.705461.

- Qiao, G. 2020. “A Critical Response to Western Critics’ Controversial Viewpoints on Chinese Traditional Narrative and Fiction Criticism.” Critical Arts 34 (2): 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1712444.

- Riva, N. 2017. “Putonghua and Language Harmony: China’s Resources of Cultural Soft Power.” Critical Arts 31 (6): 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2017.1405449.

- Sarma, P. M. 2012. “The Politics of Curriculum and Pedagogy: Teaching Cultural Studies in North East India.” Critical Arts 26 (1): 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2012.663173.

- Schein, L. 1997. “Gender and Internal Orientalism in China.” Modern China 23 (1): 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/009770049702300103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/189464.

- Shen, Q., and Y. Liu. 2023. “The Classical Chinese Gardens as a Medium: Rethinking the Visual Transformation in Chinese Culture in the Twentieth Century.” Critical Arts 37 (3): 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2263055.

- Si-he, C. 1997. “Three Value Orientations of Intellectuals in a Period of Transformation.” In A Collection of Chen Si-He’s Essays, 177–178. Guilin: Guangxi University Press.

- Slack, J. D., and L. Grossberg, eds. 2016. Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Song, G. 2023. “Cross-cultural Exchange of Heritage in Museums: A Study of Dunhuang Art in the Hong Kong Heritage Museum from the Perspective of Cultural Translation.” Critical Arts 37 (2): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2237094.

- Song, J. 2021. “Appraising with Metaphors: A Case Study of the Strategic Ritual for Invoking Journalistic Emotions in News Reporting of the China–US Trade Disputes.” Critical Arts 35 (5-6): 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.2004182.

- Souchou, Y. 1996. “Patience, Endurance and Fortitude”: Ambivalence, Desire and the Construction of the Chinese in Colonial Singapore.” Critical Arts 10 (2): 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560049685310131.

- Tan, J. 2017. “Beijing Meets Hawai’i: Reflections on Ku’er, Indigeneity, and Queer Theory.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 23 (1): 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3672429.

- Trees, K. and A. Turk. 1998. “Community, participation and cultural heritage: The Ieramugadu Cultural Heritage Information System (ICIS).” Critical Arts 12: 1–2, 78–91. doi:10.1080/02560049885310061

- Tomaselli, K. G., and Y. Du. 2021. “Identity, Différance, and Global Cultural Studies: China Going Abroad.” In Literature and Interculturality (3). From Cultural Junctions to Globalization, edited by M. Steppat, and S. Kulich, 231–263. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Educational Press.

- Tomaselli, K. G., and A. Shepperson. 2000. “South African Cultural Studies: A Journal's Journey from Apartheid to the Worlds of the Post.” In Cultural Studies: A Research Volume 5, edited by N. Denzin, 3–24. Stamford: JAI Press.

- Wagner, K. B. 2016. “Endorsing Upper-Class Refinement or Critiquing Extravagance and Debt? The Rise of Neoliberal Genre Modification in Contemporary South Korean Cinema.” Critical Arts 30 (1): 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1164389.

- Wang, X. 2020. “Reception and Dissemination of Qiyun Shengdong in the Western Art Criticism.” Critical Arts 34 (2): 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1690536.

- Wang, X. 2021. “Construing Community with a Shared Future in President Xi Jinping’s Diplomatic Discourse (2013–2018): The Role of Personal Pronouns we and They.” Critical Arts 35 (3): 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1985154.

- Wang, G., and X. Ma. 2021. “Were They Illegal Rioters or Pro-Democracy Protestors? Examining the 2019–20 Hong Kong Protests in China Daily and The New York Times.” Critical Arts 35 (2): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2021.1925940.

- Wang, X., and X. Sun. 2023. “Bibliometric Study on Chinese Discourse (1994-2021).” Critical Arts 37 (3): 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2229908.

- Wang, F., P. Humblé, and J. Chen. 2020. “Towards a Socio-Cultural Account of Literary Canon’s Retranslation and Reinterpretation: The Case of The Journey to the West.” Critical Arts 34 (4): 117–131. doi:10.1080/02560046.2020.1753796

- Weber, I. 2011. “Mobile, Online and Angry: The Rise of China's Middle-Class Civil Society?” Critical Arts 25 (1): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2011.552204.

- Wei, C., and W. Liu. 2019. “Coming out in Mainland China: A National Survey of LGBTQ Students.” Journal of LGBT Youth 16 (2): 192–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1565795.

- Wright, H. K., and Y. Xiao. 2020. “African Cultural Studies: An Overview.” Critical Arts 34 (4): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1758738.

- Wu, D. D. 2008. Discourses of Cultural China in the Globalizing Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Wu, Y. 2020a. “Globalization, Science Fiction and the China Story: Translation, Dissemination and Reception of Liu Cixin’s Works Across the Globe.” Critical Arts 34 (6): 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1850820.

- Wu, Y. 2020b. “Globalization, Divergence and Cultural Fecundity: Seeking Harmony in Diversity Through François Jullien’s Transcultural Reflection on China.” Critical Arts 34 (2): 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1713836.

- Wu, Y. 2023a. “Digital Globalization, Fan Culture and Transmedia Storytelling: The Rise of web Fiction as a Burgeoning Literary Genre in China.” Critical Arts 37 (3): 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2228856.