ABSTRACT

Destructive human action is causing interconnected ecological and social challenges on an unprecedented scale. Scholars and artists from varied fields have critically expressed their concern about this in their research and practice. In this article, we interrogate the transformative potential of critically engaged art by analysing the work of the Finnish artist duo Gustafsson&Haapoja, a collaboration between writer Laura Gustafsson and visual artist Terike Haapoja. Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work focuses on the intersecting human exceptionalist, racist, imperialist, patriarchal, and capitalist histories of violence towards nonhuman animals and dehumanised humans. These histories often provoke uncomfortable affects. As such, they can be challenging to confront. To account for this difficulty, we approach Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art through the idea of transformative learning, a process designed to shake established thinking and behavioural patterns. We investigate how Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art—and art more generally—could function as a transformative learning resource and enable sudden ruptures in hegemonic cultural norms, privileges, and power positions. We focus on how transformative learning emerges through central features in Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work: (1) their investigation and reimagination of the museum, an institution historically tied to notions of humanity and human action; and (2) their critical dissection of the complex relationship between Western-centric conceptualisations of humanity and its “others.” The article is based on a theoretical discussion and a qualitative analysis of works, exhibitions, and texts published by Gustafsson&Haapoja’s Museum of Becoming (2020–21) as well as an interview with the artists.

Introduction

Destructive human action is currently causing interconnected ecological and social challenges on an unprecedented scale. A move towards a more socially and ecologically sustainable society is not only a matter of technology, innovation, or science, but requires a cultural transformation, meaning “a large-scale change in the shared knowledges, lifestyles, traditions, beliefs, morals, laws, customs, values, institutions, and worldviews, and how they are practiced in everyday life” (Koistinen et al. Citation2023, 232). In this article, we suggest that art can promote such change by enabling transformative ways of knowing and learning. We interrogate this transformative potential in the art of Gustafsson&Haapoja, a collaboration between two Finnish artists, writer Laura Gustafsson and visual artist Terike Haapoja.

We have chosen to focus on Gustafsson&Haapoja’s artwork because it addresses pressing sociocultural issues, such as the intersecting human exceptionalist, racist, imperialist, patriarchal, and capitalist histories of violence directed to nonhuman animals and dehumanised humans—including women, colonial subjects, and “other others” (see Ahmed Citation2004, e.g. 4–12, 24–25). Their work is driven by a desire to approach the intertwining histories of human and nonhuman lifeforms from a non-anthropocentric perspective (GH Citation2020). It is also marked by a critical take on the Western scientific, philosophical, and religious discourses in which humanity has been defined (see also Koistinen et al. Citation2023).

As a collaborative effort of a writer and a visual artist, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art relies not only on visual but also on verbal (and aural) forms of expression. Their immersive artworks combine video and image material with text in ways that are prone to evoke thoughts, feelings, and associations—including cognitive dissonance, denial, and other uncomfortable affects. Moreover, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work deals with the question of knowledge production and its inherent ethics. The artists themselves identify the “cerebral” nature of their work as the most prominent element of their collaboration (GH Citation2020). They refer here to the fact that their art tends to be heavily centred around language and utilises scientific knowledge (GH Citation2020).

It is Gustafsson&Haapoja’s (1) outspoken desire to engage in sociocultural debates while challenging existing knowledge structures and (2) tendency to play with scientific and artistic ways of producing knowledge, making surprising connections and associations, that motivated us to approach their art through the idea of transformative learning (Mezirow Citation2018). Transformative learning refers to learning processes that can shake established thinking, knowing, and accustomed behavioural patterns, enabling sudden ruptures in hegemonic cultural norms, privileges, and power positions. A key element in this sort of learning is facing the uncomfortable feelings and cognitive dissonance invoked by the acknowledgement and critical reflection of one’s prejudices and presuppositions (Matikainen Citation2022).

Although we discuss the concept of learning, we do not seek to measure learning outcomes or develop concrete pedagogical tools. Instead, we offer a theoretical and analytical contemplation on art’s potential to invoke transformative learning that can inspire societal, ecological, and cultural change—with Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art as our case study. We are especially interested in the ways that Gustafsson&Haapoja’s artistic choices and the affective and cognitive affordances of their art could challenge collectively held sociocultural truths. In other words, we focus on how Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art foregrounds certain affective and cognitive responses related to human exceptionalist and violent practices, and how it may participate in modifying societal, ecological, and cultural realities.

We focus on the Museum of Becoming (henceforth MoB), a tripartite art installation displayed in Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), Finland, between 2 June 2020 and 17 January 2021. MoB consisted of the reinstallation of The Museum of Nonhumanity (MoN, 2016), an award-winning imaginary museum exploring the intersections between the exploitation of nonhuman animals and the dehumanisation of certain human beings; and two new entities, Remnants (2020), a curated collection of art objects from the HAM collection; and Becoming (2020), a three-hour multichannel video work dealing with possibilities for ethical coexistence of humans and nonhumans on this planet. We take a cultural studies approach to Gustaffson&Haapoja’s work, understanding art as embedded in and in interaction with its broader cultural context (e.g. hooks Citation1995; Williams Citation1985, 14). Our analysis is grounded in intersectional feminist perspectives and decolonial and posthumanist theories.

The article is based on a qualitative analysis of the two parts of the exhibition that included original artworks by Gustafsson&Haapoja (MoN and Becoming, visited in August 2020) and an interview with the artists on 15 December 2020 (henceforth GH Citation2020). Our analysis is structured around two central features in Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work: (1) their non-anthropocentric investigation and reimagination of the museum, an institution historically tied to notions of humanity and human action; (2) their critical, intersectional dissection of the complex relationships between Western-centric conceptualisation of humanity and the dehumanisation of the multitudes of human and animal others who are constructed as its counterpart.

The museum of becoming

Before embarking on the analysis, we offer a short description of MoB. The idea of the museum has been a consistent, repeating theme in Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work; the fascination with the museum stems from their first artistic collaboration. As Gustafsson describes, they were initially united by an aspiration to explore alternatives to human exceptionalist thinking and “quickly got the idea that the history of other animal species [besides humans] ought to be told from a non-anthropocentric perspective, and that an installation of some kind ought to be established for this history”Footnote1 (GH Citation2020). The idea resulted in the 2013 “ethnographic museum,” The Museum of the History of Cattle, exhibiting the shared history of cattle and humans from a “bovine perspective.” This was followed by the 2016 installation MoN, and eventually the MoB, which extends these considerations of what a museum can be.

Each of the aforementioned installations was accompanied by a multimodal book (Gustafsson and Haapoja Citation2015, Citation2019, Citation2020). These books not only repeat the themes, texts, and visual imagery of the installations but add theoretical and poetic contemplations (including images) on their themes. Additionally, both artists have published several essays and articles on the theoretical underpinnings of their artistic practice (e.g. Gustafsson Citation2020; Haapoja Citation2019, Citation2021, Citation2023).

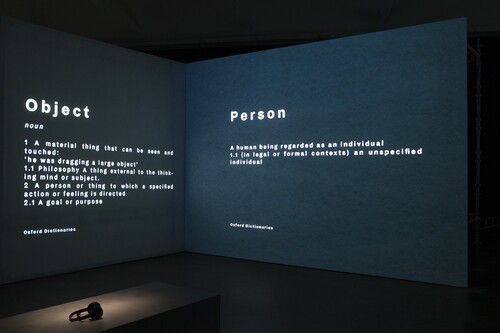

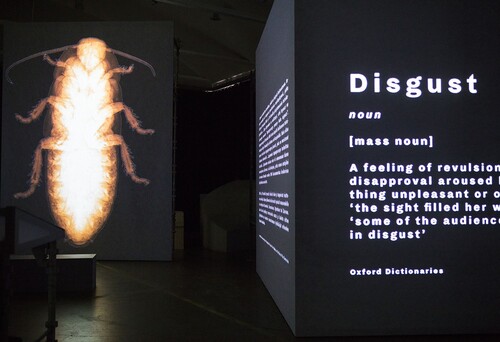

At HAM, MoB consisted of three parts that were displayed in three separate spaces. When entering MoB, the visitors first find themselves in MoN, a ten-channel, seventy-minute video installation, the only part of the exhibition that has been exhibited previously as an independent entity. MoN deals with the techniques of dehumanisation, or rather animalisation (see Haapoja Citation2021), which are used to justify the violence toward nonhuman animals as well as some human animals. The exhibit is constructed around twelve affectively loaded concepts: “person,” “potentia,” “monster,” “resource,” “boundary,” “purity,” “disgust,” “anima,” “tender,” “distance,” “animal,” and “display” (). Each concept’s violent history is “excavated” (see Foucault Citation1972) in a three- to ten-minute-long video installation, in slideshow-like presentations that consist of textual fragments from a wide range of sources (e.g. encyclopaedia entries, etymological excerpts, historical records, policy documents, and media and social media commentaries) and visual imagery, like photographs, blueprints, and historical illustrations.

Figure 1. As one excavated concept in MoN, Gustafsson&Haapoja study “person” through debating the object–person dichotomy. Photo © Terike Haapoja. Courtesy of the artists.

Beyond the videos projected onto multiple screens, the exhibition space of MoB is rather minimalist, consisting of scaffolding covered by white sheets and not much else. Behind the sheets are scattered wooden boxes, on top of which regular natural history museum objects, like taxidermy animal remains and skeletons, are displayed in vitrines, visible as shadows on the white sheets (). Simple seats invite the visitors to sit down to watch the projections. Each thematic section in the video has a distinctive colour scheme that effectively tints the entire space covered by the white cloths. The exhibition is accompanied by sombre, mournful instrumental soundscape, which, together with the changing colours, contributes to the affective atmosphere of the installation space (see Sumartojo and Pink Citation2019).

A more spacious installation room is occupied by Becoming, a three-hour, three-channel video work offering a meditation on how humans could better coexist with one another and with other lifeforms. The video consists of interviews with scholars, artists, activists, and other individuals such as children, who Gustafsson&Haapoja have found essential for reimagining human societies and human–nature relationships from a more sustainable and ethical viewpoint. Questions—including how to live, how to listen, how to love, and how to die—create a central focus of the interviews. The interviewees could decide which of thirty-one questions they answered, and were encouraged to create questions of their own (GH Citation2020). The video is pieced together from headshot interview clips, closeups of interviewees’ embodied gestures, and atmospheric clips of human and natural environments, with children playing, a river flowing, and treetops swaying in the wind. As the artists recount, the long video itself is not intended to be viewed in one go: it could be accessed on Vimeo through a QR code presented at the exhibition.

The video is exhibited on three huge screens at the one end of a large yet mostly empty museum space, with three circular seats positioned near the screens, where the visitors can either sit or lie down to experience the video that fills the space with imagery and a soundscape of speech, nature sounds, and music. The back end of the space includes the names and information of the individuals interviewed for the video, as well as printed pages from Bud Book, the publication expanding the themes of the video work. In this sense, the exhibition provides transmedial access points (see Klastrup and Tosca Citation2014) that expand Becoming beyond the exhibition space: a physical copy of Bud Book can be purchased and read whenever and wherever one wishes.

One option to experience the exhibition is offered by a map designed by queer feminist curatorial duo nynnyt (“sissies”), offering a path to approach the themes of Becoming. The four exercises on the map invite children, but also “their adults,” to sense the sensory stimuli in the museum space. Tasks include: “What is the most silent sound you can hear? Listen to it. What does it tell you?” or “Listen to yourself. What do you sound like? What kinds of things do you contain? What kind of things can you do?” As a multimedia and multimodal installation that engages visitors via cognitive and sensual modes of expression—with a guided map encouraging visitors to pay close attention to the affects, emotions, and experiences it evokes—MoB offers myriad opportunities for invoking transformative learning. In what follows, we first describe our theoretical approaches, after which we delve deeper into the analysis of Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art by focusing on what we deem the most relevant parts of MoB for transformative learning.

Uncomfortable knowledges and transformative learning: theoretical approaches

Addressing the themes dominating Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art can be an unpleasant and deeply uncomfortable process both individually and collectively. First, it means challenging intertwining notions and internalised attitudes about valuable life, rooted into hierarchical configurations between human and other life (Chen Citation2012). Recognising this interconnectedness between the exploitation of nature and nonhuman animals, and the oppression and dehumanisation of certain human beings, Sanna Karkulehto et al. (Citation2016, 3) note:

the cultural meanings given to nonhuman animals often reflect and coincide with the attitudes and assumptions held toward repressed or marginalized groups, whereby the treatment of animals and nonhumans is connected to the treatment of the humans who are, in varying contexts, viewed as lesser, weaker, subordinate, or substandard.

Our interest lies in Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art’s capability to invite people to become aware of the often-denied histories and practices of violence and inspire them to act against the prevailing norms—two principles inherent to transformative learning. The idea of transformative learning is based on three foundational principles (e.g. Kegan Citation2018; Matikainen Citation2022; Mezirow Citation2018). First, creating and assigning meanings is an essential part of human life (see also Hall Citation1997, 61). Second, a person can become more aware of these meaning-making processes, and the cultural and political norms and ideologies that drive their actions. Third, thereby one gains tools to oppose, unlearn, or resist hegemonic interpretive frames and knowledges. This third stage, transformation, can often be achieved only through an uncomfortable process, or rupture, of coming to terms with one’s own innate assumptions and attitudes, sociocultural privileges, and positions of power. If successful, transformative learning may change collective notions of normal or desired behaviour in a society (Ziehe Citation2018, 206).

It has been argued that the feeling of discomfort may be “productively unsettling” in teaching and learning, meaning that uncomfortable feelings have potential to challenge fixed epistemologies, thus inspiring new knowledges (e.g. Hyvärinen, Koistinen, and Koivunen Citation2021; Juvonen Citation2006). Feminist scholars, such as Katariina Kyrölä (Citation2018), have also argued that feeling uncomfortable is sometimes important in the learning process. We argue that productive unsettlement, or learning through discomfort, is an incremental part of transformative learning, and art can serve as a space for it (see Hyvärinen, Koistinen, and Koivunen Citation2021, 12). Art, therefore, can have transformative potential.

Cultural studies commonly understands art as a powerful form of meaning-making (e.g. Hall Citation1997; hooks Citation1995; Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2022). This connects art to transformative learning. Art’s potential to evoke affective responses, which may lead to activism, has been widely recognised (e.g. Hiltunen, Saresma, and Sääskilahti Citation2020; Simoniti Citation2018). So has its potential to engender transformative ways of knowing (e.g. Eisner Citation2008). The transformative capacity of art, art education, and art-based research has been connected to their power to enrich human imagination regarding the experiences of others, including the engendering and learning of empathy (e.g. Lähdesmäki and Koistinen Citation2021; Leavy Citation2017; Stout Citation1999), and opening “the door for multiple forms of knowing” (Eisner Citation2008, 5).

Elliot W. Eisner posits that art influences knowledge production in three ways: first, by evoking nuanced understanding by emphasising phenomena’s situatedness; second, by generating a “kind of empathy that makes action possible”; and third, offering “a fresh perspective so that our old habits of mind do not dominate our reactions with stock responses” (2008, 10–11). Art can serve as a space where different knowledges and experiences can be safely encountered (Lähdesmäki and Koistinen Citation2021; on safe spaces, see Gurian Citation2010; Kyrölä Citation2018). As it helps people to grasp the experiences of others, art has the capacity to foreground situated knowledges based on for example gendered, classed, or racialised experiences (Lähdesmäki and Koistinen Citation2021; see also Haraway Citation1988). Furthermore, imagining of the experiences of others, leading to empathic or sympathetic responses, may extend to nonhuman beings (Koistinen et al. Citation2023; Weik von Mossner Citation2017). These factors therefore make art suitable for engaging in transformative learning, including dismantling anthropocentric perspectives.

The transformative potential of a museum in the state of unravelling

The museum is a loaded platform for criticising the human exceptionalist tendencies of contemporary societies. Ethnographic and natural history museums have contributed to the moral binary of humanity versus animality by dividing the world between viewers (the White, Western, upper-class—and human—audiences) and viewed (the many human and animal others, plants, artefacts, and other others that have been objectified in their exhibits). The knowledges constructed on this binary have had extensive and long-lasting effects. In MoN, Gustafsson&Haapoja attack the reality created through this violent, elitist, patriarchal, racist, and human exceptionalist history of the museum institution (e.g. Abungu Citation2018; Bal Citation1992; Levitt Citation2015; Mignolo Citation2011) head on. As they explain in their interview, the artists find the notion of the museum as an institution of knowledge and truth intriguing. They discuss their habitual negotiation with institutions and institutionalised knowledge from non-anthropocentric and artistic perspectives:

Our fascination with institutions stems from […] the way their truth value is constructed by believing in them, their authority built by use of authority, and the truths they tell built by a collective faith on their truthfulness. All these institutions are social constructions […] And through this [recognition of their constructed nature] we can also question their epistemic authority and ask why the histories we build could not be the authorised knowledge, or templates for knowledge. It depends on which viewpoints are held as valid. (GH Citation2020)

Yet even critical museums are often chided for reiterating the same power structures that they seek to unwind (Turunen Citation2020; Turunen and Viita-aho Citation2021). The problem is not that museums avoid taking a stance on difficult sociocultural phenomena, per se. Rather, their critical stances often fail to account for their own role in creating and sustaining the problems they attempt to critique. Reiterating Audre Lorde (Citation2017, 91): “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

Accordingly, if one wishes to achieve more sustainable changes within the museum space, one must reimagine the tools used in/by museums. In our interpretation, Gustafsson&Haapoja attempt to achieve this through numerous means. First, they break away from the object-centred logic of museums and move towards a knowledge-centred one that brings together artistic and scientific methods of knowledge production. In doing so, they use writing to fight the obsession museums tend to have with material artefacts and instead shift the focus onto what is “normally erased in the museums: the context” (Gustafsson and Haapoja Citation2015, 108).

In interview, Gustafsson&Haapoja recognise art markets’ capitalist involvement with the fossil fuel-based economy and arms trade.Footnote2 Discussing the reasons their exhibitions stray from the material traditions of visual art, Haapoja refers to a distinction between Western and non-Western conceptions of art:

Guatemalan curator Pablo Jose Ramirez has discussed Mayan art in the context of reproduction of life, where art is interwoven with life sustaining practice and traditions […] so I have been thinking how the Western conception of art posits art in the service of death. The practices produce a world of death, or a world that is against life, and growth, and transformation. And we did not want to be involved with it. And [when creating the 2020 exhibition] we used to think what this Museum of Becoming – because we had this pair of words – could be like. And we immediately realised that it cannot be material stuff. No way can it be material stuff that we would somehow make to represent transformation. It had to be something else … oral, immaterial, something else. (GH Citation2020)

This uncertainty is compounded by curatorial choices that play with the idea of the museum in a state of unravelling and mix traditional museum aesthetics and tropes (see Mignolo Citation2011). The exhibition space is filled with scaffolding covered by white sheets, creating an eerie feeling of an abandoned building—or a museum space in a liminal state between reconstruction and abolition. As Gustafsson&Haapoja explain, this unravelling symbolises how “the museum is in the process of changing” (GH Citation2020). It is unstable, much like the anthropocentric, colonial, and patriarchal “truths” that the museums have historically sought to promote. Scattered behind the sheets are wooden and cardboard boxes, reminiscent of those usually used to store museum artefacts. While contributing to the aesthetic atmosphere of demolition and renovation, these boxes can be interpreted as symbols of the endless number of animal and human remains locked in museum storage. On top of the boxes is a selection of animal remains, primarily skeletons or taxidermy mounts, sealed in vitrines. Together the boxes and the remains make the violence of the anthropocentric museum physically present in the exhibition space, but in a subtle, haunting way. The visitor can only see the animals and the boxes through the shadows they create on the sheets ().

This unravelling is ultimately linked to the idea of humanity itself. As Gustafsson&Haapoja elaborate in their interview:

In MoN we show how this human, or rather the [idea of] a human produced by White supremacy and patriarchal structures, has been constructed. And in Remnants it is being dismantled. And in Becoming we start constructing it again. (GH Citation2020)

Altogether, MoB could be characterised as dominated by overwhelm: projections on several screens at once make it impossible for the visitor to follow everything simultaneously. After each episode in the video, there is a break that entices the visitor to move to the next area, but after a short while a new episode begins, prompting the visitor to hesitate as to whether they are supposed to move forward or not. By refusing to play by the established rules for how a museum space orients visitors, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s museum again forces the visitor outside their comfort zone.

This confusion or unsettlement is not an accidental byproduct of the exhibition. Instead, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art can be seen as a systematic attempt to create both physical and imaginative spaces to reenvisage what a society could be when it is stripped of its human exceptionalist character, with those who the museum has historically sought to reduce and objectify taking centre stage, as Gustafsson says:

For me, in the MoN the most important thing was the way it created this space where something like this can exist […] that there exists a museum, which stores all the dehumanisation, or these distinctions between humans and animals and their violent conceptual apparatus. […] That [these spaces] create these types of … utopia is a wrong term in this sense, because these places will be real … but affordances or possibilities, especially through imagination. (GH Citation2020)

Critical dissections of humanity and its “Others”

Next, we turn to how Gustafsson&Haapoja grapple with the difficult task of taking an intersectional, contra-institutional approach to the violent histories of humanity and its others, in their interview on MoB. In their own words, Gustafsson&Haapoja aim

to bring together critical animal studies perspectives, environmental or ecological justice perspectives, and social justice perspectives into the discussion of the concepts of “animal” or “nonhuman.” It is our political objective that these discussions should not be separate. We should be able to face the ways the exploitation of both nature and humanity are intertwined through these central concepts and dichotomies with shared historical roots. (GH Citation2020)

Despite this difficulty, addressing the violent histories where animal and human rights intersect is a central feature in both parts of MoB that we examine: in MoN through the critical dissection of these histories, and in Becoming through a more utopian imagining of humanity without such violence. Similarly to the artist duo, who describe the affordances of art as “facilitating seeing the broader picture of how phenomena are related to one another and what rationales they have” (GH Citation2020), we consider this intersectional approach crucial for creating sociocultural change. Like Gustafsson&Haapoja’s reimagination of the museum, which we discussed as inviting “productively unsettling” affects (Hyvärinen, Koistinen, and Koivunen Citation2021; Juvonen Citation2006), this intersectional approach creates specific affective affordances for confronting the violent structures treated in Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work (see Ahmed Citation2004).

In MoN we can witness the affective power of constant human/animal juxtapositions and their intersecting histories. The installation focuses on how binary concepts of human and animal have been constructed through discourses and the language used to distance certain lives from humanity. MoN’s study of the concept “Disgust” (), for instance, opens with the definition of pests as “any organism judged as a threat to human beings or their interests” (Gustafsson and Haapoja Citation2019, 150), and takes up the well-known example of the Rwandan genocide, where the minority ethnic group Tutsi were dehumanised through terming them Inyenzi, cockroaches. The slideshow-like examples spun around the concept of “Boundary” connect the Finnish hatred and fear of wolves, an animal seen as “rapacious, ferocious, or voracious” (Gustafsson and Haapoja Citation2015, 127), to the 1918 Civil War between White and Red Finland. During the war, the “Red women” involved with the Finnish Red army or Finnish socialist parties were called “wolf bitches,” a term systematically used to justify their massacre (Gustafsson and Haapoja Citation2015, 119–137; see also Haapoja Citation2023). The animalisation of the Tutsi and the Red women was an explicit act to move them into the animal realm, thus aligning them with nonhuman beings as discardable and freely killable (e.g. Haapoja Citation2019; Ko and Ko Citation2020): a tactic motivated by the interconnections of racial and ethnic purity and human essentialist desires.

Figure 3. In MoN, Gustrafsson&Haapoja study dehumanisation through the genealogical excavation of concept “disgust”. Photo © Terike Haapoja. Courtesy of the artists.

These genealogical excavations of the circulation of affectively loaded concepts—cockroach and wolf—testify to how certain human bodies become “sticky” with negative affect through their contact with animal- and nature-related signs, objects, and bodies that drag along affective associations, social tension, and stigma. Sara Ahmed (Citation2004) has famously argued that objects and signs become affectively invested through time, as they are culturally circulated, making specific affective content “stick.” For instance, the stripping of the Tutsi’s humanity and right to live rested on insects’ “symbolic utility in representing otherness and on their instrumentality in the differentiations between groups of people” (Kosonen Citation2022, 93), pests’ association with dirt, disease, and death (Kosonen Citation2022), and fears of their excessive proliferation (e.g. Sleigh Citation2007, 290). In the Finnish context, the wolf is affectively connected to evil and the supernatural (Vilkka Citation2009, 30; see also Lähdesmäki Citation2020) and considered specifically violent, making it important to establish a strict boundary between it and human beings (Ratamäki Citation2009, 48).

These genealogies discussed by Gustafsson&Haapoja rely on surprising affective associations. MoN introduces the audiences to the cockroach and wolf cases to suggest that in human societies, dehumanisation is not an exception, but the rule. Taking an example from Finland’s silenced civil war history brings the strategy of dehumanisation affectively and effectively close to the local audiences. By highlighting the multiplicity of, and intersections between, these dehumanising practices, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art causes ruptures in the affectively sticky and reiterating association chains between signs and their objects—for instance between disgust and its tendentious objects—and instead attaches these circulating affects to the harmful structures behind them.

In Becoming, the power of the intersectional approach works differently. The artists describe their strategy of bringing together activists and inspiring individuals from all fields as their interviewees:

We wanted to create a feeling that there is a huge number of people [striving for change], that we in effect are no minority, but actually the majority … That we most definitely are the majority, creating a feeling that there is a multitude of these people, and points of view, and actors working for these goals, countering the discourse of always being the underdog, with little chance of winning. (GH Citation2020)

Beyond this intersectionality, another factor we consider as enabling transformative learning in both MoN and Becoming, is the “cerebral” nature of Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art combined with the exhibitions’ affectively immersive and often unsettling nature. Gustafsson&Haapoja consider art’s ability to create experiential spaces for imagination and empathy:

An ethical awakening is not a process dependent on knowledge. Knowledge can prepare the ground for somebody being a little more open to this awakening […] but it is an experiential process that you actually awaken to something, say violence, for instance, or feel empathy or something like that. Perhaps art, at its best, has this ability to create a certain kind of space, where it is possible to be open to this experience on a level that is not cerebral, rational […] Perhaps art’s greatest potential is that it can help you imagine such possibilities that have not yet manifested. (GH Citation2020)

Furthermore, Gustafsson&Haapoja describe their means of conveying knowledge and creating these experiential possibilities as being facilitated by art’s and their own installations’ capacity to shift perspective from scientific normativity:

Somehow the instruments of art are not normative in a similar way as those of science. Or, art’s way to approach norms is such that it avoids being normative in itself, or that this normativity is on a different level to science […] In our art, we attempt to shift the perspective, or in a way we try to look at this normative knowledge from a different perspective. (GH Citation2020)

facilitating an insight, an understanding, that suddenly takes the self-evident knowledge of “dehumanisation being a mechanism of violence” somehow further … I mean everybody knows this already, it just demands that something new arises in the people who already know this. (GH Citation2020)

being in the process of becoming … against this idea and ideology of historical narratives, where there is a beginning and an end, and the history in the middle. We did not want to search for such a narrative, but for something that happens, or is in the process of taking shape, looking for a way. (GH Citation2020)

This lack of a narrative invites the audience to construct their own understanding from the fragmentary pieces presented to them. We consider this as one way in which Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art helps audiences overcome the cognitive challenges related to processing uncomfortable knowledges.

Conclusion: transformative learning in the museum space

From the dehumanising rhetoric justifying the exploitation and killing of (certain) human and nonhuman animals to the capitalist structures accelerating the environmental crisis, many of the phenomena explored by Gustafsson&Haapoja are linked to pressing threats to the environment, humanity, and nonhuman species. Leon Sealey-Huggins has introduced the term “existential imperialism” (Citation2017, 2446, see also Turunen Citation2019) to refer to how colonial and capitalist webs of exploiting nature’s resources have come to threaten all life on earth. There is no use denying that the endless pursuit of profit in the Global North poses a universal and interspecies existential threat through its role in environmental and social crises such as increasingly frequent and intense storms, heat waves and drought, rising sea levels and melting glaciers, warming oceans, and the accelerating sixth mass extinction. Due to the elusive nature of these crises, and the uncomfortable emotions involved in realising one’s responsibility in such profound forms of destruction, the threats caused by human actions are often dismissed, downplayed, or denied. In this context of deep ecological crisis, philosopher Timothy Morton calls for “art that does not make people think […] but rather that walks us through an inner space that is hard to traverse” (Citation2013, 184). Art is, of course, not free of all these harmful structures, and can participate in the destruction of our planet (e.g. Brennan et al. Citation2019; Koistinen et al. Citation2023; see also Parikka Citation2018). However, as Morton suggests, art and artistic thinking can be transformative; they can offer space for questioning oppressive structures, imagining, and inspiring more sustainable futures and practices.

In this article, we have argued that art may serve the sociocultural and ecological transformation required in environmental and social crises by setting in motion the process of transformative learning. As such, our article offers a novel way of negotiating the role of art in the so-called Anthropocene. Moving from informative to transformative learning often demands facing the uncomfortable feelings and cognitive dissonance invoked by the acknowledgement of difficult truths, including one’s own prejudices and presuppositions (Matikainen Citation2022; Mezirow Citation2018). The complex experiences produced—or invited—through art, such as Gustafsson&Haapoja’s work, can be productively unsettling (Hyvärinen, Koistinen, and Koivunen Citation2021; Juvonen Citation2006).

As we have proposed, the strength of Gustafsson&Haapoja’s approach is that they do not offer ready-made answers. Instead, their critical, highly atmospheric, and affective works create a space for complex contemplation, highlighting the capabilities of artistic knowledge production to confront uncomfortable realities. In their art, Gustafsson&Haapoja bring disparate histories of violence and their associated epistemologies together but leave visitors to draw their own conclusions—thereby encouraging visitors to become an active participant in the construction of knowledge. In doing so, Gustafsson&Haapoja intentionally break the established rules of museum exhibitions, and both make and invite unforeseen connections between seemingly incongruent epistemologies—such as the remarkable similarity in the hateful discourses on the Red women as wolves, and the Tutsi as cockroaches. The multimodal and fragmented aesthetics and poetics of their art emphasise the knowledge-rich and fragmentary nature of the uncomfortable genealogies of violence toward both humans and nonhuman animals, whereas the atmospheric, immersive qualities of their exhibitions facilitate a safe space for even difficult emotions and contemplations.

Thus, rather than being a material display of artefacts, the museums constructed by Gustafsson&Haapoja constitute a gathering space for critical thinking (Sterling Citation2020, 197), unsettling audiences in many ways. Building on Robert Kegan (Citation2018), we argue that Gustafsson&Haapoja’s artwork moves beyond informative learning—the practice of increasing knowledge and skills—into the realm of the transformative. Transformative learning transgresses knowledges in surprising ways, causing ruptures and mutations in existing constructions of truth; Gustafsson&Haapoja accomplish this in ways that we as researchers and visitors felt evocative and powerful. For these reasons, we suggest that art like Gustafsson&Haapoja’s can make people aware of the collectively organised denial of difficult truths (the second premise of transformative learning) and decide to act against it (the third premise).

As bell hooks (Citation1990) argues, knowledge that seeks to challenge established (Western) sociocultural truths is always inherently unsafe—since by challenging the cultural archive it also challenges the fundamental fabric of the given society. The social norms of attention, conversation, and emotion do not usually create opportunities to constructively encounter harsh social realities or their root causes. However, art can offer avenues for such encounters with uncomfortable topics and themes. While it is beyond the scope of the present article to verify any effects that art may have on museumgoers besides ourselves, the authors, our discussion suggests that art and art museums should be utilised more robustly in transformative learning.Footnote3 Although transformative learning can occur in response to a single catalytic event—like a critical art exhibition—that forces individuals to reevaluate their essential values and priorities, the process is more commonly long, complex, and cumulative (e.g. Mezirow Citation2018). Future research should examine the experiences of museumgoers, including this longer temporal dimension that transformative learning usually demands.

Finally, the effects of art are complex and difficult to foresee. If museums want to harness the power of art for transformative learning, they need pedagogical tools attuned to encountering uncomfortable knowledges. Although museums can attempt to keep the transformative learning process sparked by art aflame, they do not have a long-term relationship with their visitors. This makes sustained pedagogical approaches very difficult, a crucial factor to remember when developing tools for studying the experiences of transformative learning among art audiences and museum visitors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All citations have been translated from Finnish to English by Kosonen.

2 In this sense, Gustafsson&Haapoja’s art comments on discussions around the role of art in cultural and social sustainability: although art can be part of sustainable practices, it is not free of capitalist and oppressive structures (see Koistinen et al. Citation2023).

3 Studying behavioural or other similar effects would require the analysis of visitor experiences, and a different study frame. While no visitor experiences were systematically gathered from the exhibitions studied here, Gustafsson&Haapoja's interviews give clues about transformative learning through visitor feedback, including a shift from animal-based diet to a vegan one.

References

- Abungu, G. O. 2018. “Connected by History, Divided by Reality. Eliminating Suspicion and Promoting Cooperation Between African and European Museums.” In Museum Cooperation Between Africa and Europe: A New Field for Museum Studies, edited by Thomas L. M. Meyer, and R. Schwere, 25–41. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Ahmed, S. 2004. Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge.

- Åsberg, C., and R. Braidotti. 2018. “Feminist Posthumanities: An Introduction.” In A Feminist Companion to the Posthumanities, edited by C. Åsberg, and R. Braidotti, 1–22. Cham: Springer.

- Bal, M. 1992. “Telling, Showing, Showing Off: A Walking Tour.” Critical Inquiry 18: 556–594. doi:10.1086/448645.

- Bal, M. 1996. Double Exposures: The Subject of Cultural Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Barone, T., and E. W. Eisner. 2012. Arts Based Research. London: Sage.

- Bennett, T. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. New York: Routledge.

- Braidotti, R. 2017. “Four Theses on Posthuman Feminism.” In Anthropocene Feminism, edited by R. Grusin, 21–48. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP.

- Brennan, M., J. Collinson Scott, A. Connelly, and G. Lawrence. 2019. “Do Music Festival Communities Address Environmental Sustainability and how? A Scottish Case Study.” Popular Music 38 (2): 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143019000035.

- Chen, M. Y. 2012. Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. London: Duke UP.

- Eisner, E. W. 2008. “Art and Knowledge.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research, edited by J. G. Knowles, and A. L. Cole, 3–12. London: Sage.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Translated from French by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books.

- GH 2020: Gustafsson, L., and T. Haapoja. 2020. Interview by Heidi Kosonen. December 15, 2020.

- Gurian, E. H. 2010. “Museum as Soup Kitchen.” Curator: The Museum Journal 53 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2009.00009.x.

- Gustafsson, L. 2020. “Tarve tuijottaa suu auki – Subliimin kokemus ja taide ihmeen alueena.” Niin & Näin 1: 49–51.

- Gustafsson, L., and T. Haapoja, eds. 2015. History According to Cattle. Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books.

- Gustafsson, L., and T. Haapoja. 2019. Museum of Nonhumanity. Santa Barbara: Punctum Books.

- Gustafsson, L., and T. Haapoja. 2020. Bud Book: Manual for Earthly Living. Helsinki: HAM.

- Haapoja, T. 2019. “Unlearning Animality.” In cursive, edited by A. Alpert & S.R. Premnath, 117-122. New York: Shifter.

- Haapoja, T. 2021. “Kohti ‘eläimen’ jälkeistä aikaa: kirjoituksia ihmiskeskeisestä ajattelusta ja ilmastonmuutoksesta.” In In Taiteen kanssa maailman äärellä, edited by A. Seppä, and H. Johansson, 100–127. Helsinki: Taideyliopiston Kuvataideakatemia.

- Haapoja, T. 2023. “Museum of Nonhumanity.” Radical History Review 145: 181–194. doi:10.1215/01636545-10063927.

- Hall, S. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: SAGE Publications.

- Hansson, P., and J. Öhman. 2022. “Museum Education and Sustainable Development: A Public Pedagogy.” European Educational Research Journal EERJ 21 (3): 469–483. doi:10.1177/14749041211056443.

- Haraway, D. J. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Hiltunen, K., T. Saresma, and N. Sääskilahti. 2020. “Rajojen poetiikkaa ja politiikkaa: Taiteellinen aktivismi reaktiona ‘pakolaiskriisiin’.” Media & viestintä: kulttuurin ja yhteiskunnan tutkimuksen lehti 3: 150–175. doi:10.23983/mv.95674.

- hooks, bell. 1990. Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics. Boston, MA: South End.

- hooks, bell. 1995. Art on my Mind: Visual Politics. New York: New Press.

- Hyvärinen, P., A. Koistinen, and T. Koivunen. 2021. “Tuottavan hämmennyksen äärellä – Näkökulmia feministiseen pedagogiikkaan ympäristökriisien aikakaudella.” Sukupuolentutkimus – Genusforskning 34 (1): 6–18.

- James, W. 1999. The Listening Ebony: Moral Knowledge, Religion, and Power among the Uduk of Sudan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Janes, R. R., and R. Sandell. 2019. Museum Activism. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Juvonen, T. 2006. “Kohti pervopedagogiikkaa. Lesbo- ja queer-tutkimuksen opettaminen haasteena yliopistopedagogiikalle.” Naistutkimus–Kvinnoforskning 19 (4): 6–16.

- Karkulehto, S. et al. 2016. “Reconfiguring Human, Nonhuman and Posthuman: Striving for More Ethical Cohabitation.” In Reconfiguring Human, Nonhuman and Posthuman in Literature and Culture, edited by S. Karkulehto et al., 1–19. New York: Routledge.

- Katriel, T. 1993. “Our Future is Where Our Past Is: Studying Heritage Museums as Ideological Performative Arenas.” Communication Monographs 60 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1080/03637759309376296.

- Kegan, R. 2018. “What ‘Form’ Transforms? A Constructive-Developmental Approach to Transformative Learning.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning. Learning Theorists … in Their own Words, edited by K. Illeris, 29–45. New York: Routledge.

- Klastrup, L., and S. Tosca. 2014. “Game of Thrones: Transmedial Worlds, Fandom, and Social Gaming.” In Storyworlds Across Media. Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, edited by M-L Ryan, and J-N Thon, 295–314. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Ko, A., and S. Ko. 2020. Aphro-Ism – Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. Brooklyn: Lantern Books.

- Koistinen, A., K. Kortekallio, M. Santaoja, and S. Karkulehto. 2023. “Towards Cultural Transformation: Culture as Planetary Well-Being.” In Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Planetary Well-Being, edited by M. Elo, J. Hytönen, S. Karkulehto, T. Kortetmäki, J. Kotiaho, M. Puurtinen, and M. Salo, 231–245. London: Rougledge. doi:10.4324/9781003334002-23.

- Kosonen, H. 2022. “The Yuck Factor: Reiterating Insect-Eating (and Otherness) Through Disgust.” In Cultural Approaches to Disgust and the Visceral, edited by M. Ryynänen, H. Kosonen, and S. Ylönen, 90–103. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003205364-10.

- Kosonen, H. 2023. ““Isn’t Self-Destruction Coded Into Us, Programmed Into Each Cell?”: A Thanatological, Posthumanist Reading of Garland’s Annihilation (2018).” Journal of Ecohumanism 2 (2): 161–175. doi:10.33182/joe.v2i2.3007.

- Kosonen, H., and P. Greenhill. 2022. “’Something’s not Right in Silverhöjd’: Nordic Supernatural and Environmental and Species Justice in Jordskott.” Folklore 133 (3): 334–356. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2022.2044598.

- Kyrölä, K. 2018. “Negotiating Vulnerability in the Trigger Warning Debates.” In The Power of Vulnerability. Mobilising Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti-Racist Media Cultures, edited by A. Koivunen, K. Kyrölä, and I. Ryberg, 29–50. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lähdesmäki, H. 2020: Susien paikat. Ihminen ja susi 1900-luvun Suomessa. Jyväskylä: Nykykulttuuri.

- Lähdesmäki, T., J. Baranova, S. Ylönen, A. Koistinen, V. Juškienė and I. Zaleskienė. 2022. Learning Cultural Literacy Through Creative Practices in Schools: Cultural and Multimodal Approaches to Meaning-Making. Switzerland: Palgrave Pivot. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007978-3-030-89236-4.

- Lähdesmäki, T., and A. Koistinen. 2021. “Explorations of Linkages Between Intercultural Dialogue, art, and Empathy.” In Dialogue for Intercultural Understanding: Placing Cultural Literacy at the Heart of Learning, edited by F. Maine and M. Vrikki, 45–58. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-71778-0.

- Leavy, P. 2017. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Levitt, P. 2015. Artifacts and Allegiances: How Museums Put the Nation and the World on Display. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Lorde, A. 2017. Your Silence Will not Protect you. London: Silver Press.

- Matikainen, M. 2022. Transformatiivinen opettajaksi oppiminen: fenomenologis-hermeneuttinen analyysi luokanopettajakoulutuksesta. PhD dissertation. Jyväskylä. University of Jyväskylä.

- Mezirow, J. 2018. “An Overview on Transformative Learning.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning. Learning Theorists … in Their own Words, edited by K. Illeris, London: Routledge. 114–128.

- Mignolo, W. 2011. “Museums in the Colonial Horizon of Modernity. Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992).” In Globalization and Contemporary Art, edited by J. Harris, 71–85. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Morton, T. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. London: Minnesota UP.

- Norgaard, K. 2011. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Parikka, J. 2018. “Medianatures.” In Posthuman Glossary, edited by R. Braidotti, and M. Hlavajova, 251–253. London: Bloomsbury.

- Ratamäki, O. 2009. “Luonto, kulttuuri ja yhteiskunta osana ihmisen ja eläimen suhdetta.” In Ihmisten eläinkirja, edited by P. Kainulainen and Y. Sepänmaa, 21–36. Helsinki: Palmenia.

- Reilly, M. 2018. Curatorial Activism. Towards an Ethics of Curating. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Said, E. W. 2003. Orientalism. London: Penguin. Penguin Classics.

- Sealey-Huggins, L. 2017. “‘1.5°C to Stay Alive’: Climate Change, Imperialism and Justice for the Caribbean.” Third World Quarterly 38 (11): 2444–2463. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1368013.

- Simoniti, V. 2018. “Assessing Socially Engaged Art.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 76 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1111/jaac.12414.

- Sleigh, C. 2007. “Inside Out: The Unsettling Nature of Insects.” In Insect Poetics, edited by E. C. Brown, 281–297. London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sterling, C. 2020. “Heritage as Critical Anthropocene Method.” In Deterritorializing the Future. Heritage in, of and After the Anthropocene, edited by R. Harrison, and C. Sterling, 188–219. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Stout, C. J. 1999. “The art of Empathy: Teaching Students to Care.” Art Education 52 (2): 21–34. doi:10.2307/3193759.

- Sumartojo, S., and S. Pink. 2019. Atmospheres and the Experiental World: Theory and Methods. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Turunen, J. 2019. “Katoavan maailman elegia: kapitalismin ekokritiikki ja eksistentiaalinen imperialismi.” Lähikuva. Audiovisuaalisen Kulttuurin Tieteellinen Julkaisu 32 (4): 25–33. doi:10.23994/lk.90786.

- Turunen, J. 2020. “Decolonising European Minds Through Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (10): 1013–1028. doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1678051.

- Turunen, J. 2021. "Unlearning narratives of privilege: A decolonial reading of the European Heritage Label." PhD dissertation. JyU Dissertations 427, Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Turunen, J., and M. Viita-aho. 2021. “Kriittisen museon mahdottomuus? Gallen-Kallelan Afrikka-kokoelman uudelleentulkinnat 2000-luvulla.” In Marginaalista museoihin, edited by L. Koivunen, and A. Rastas, 93–114. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Vilkka, L. 2009. “Eläinten oikeudet.” In Ihmisten eläinkirja, edited by P. Kainulainen and Y. Sepänmaa, 21–36. Helsinki: Palmenia.

- Weik von Mossner, A. 2017. Affective Ecologies: Empathy, Emotion, and Environmental Narrative. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press.

- Wekker, G. 2016. White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Williams, R. 1985. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Zerubavel, E. 2002. “The Elephant in the Room: Notes on the Social Organization of Denial.” In Culture in Mind: Toward a Sociology of Culture and Cognition, edited by K. Cerulo, 21–27. New York: Routledge.

- Ziehe, T. 2018. “‘Normal Learning Problems’ in Youth: In the Context of Underlying Cultural Convictions.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning. Learning Theorists … in Their own Words, edited by K. Illeris, 204–218. London: Routledge.