ABSTRACT

This article explores video-stimulated recall as a novel approach to understanding children’s decisions to engage in relational and physical aggression. Past studies have relied on caregiver and observer reports to investigate children’s social behaviors, omitting children’s experience and interpretation of their own behavior. Within this Australian study, 68 children age 3 to 5 years were assessed for relational aggression by teachers. Nine children identified by teachers with high relational aggression and seven children identified with average levels of relational aggression were video recorded while engaging in free play. Immediately afterward, video footage of the child engaging in aggressive behavior was shown to the child to stimulate recall of the reasons for their behavior. Subsequent analysis were focused on assessing the intentions and functions of children’s aggressive behaviors, as reported by the child. Focusing on children’s own interpretations enabled a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the child’s social cognitive processes about the intent and functions of their aggression. We demonstrate that video observations alongside video-stimulated interviews can be used to effectively elicit children’s interpretations of their own behaviors. Incorporating children’s perspectives in research and practice has several implications, such as improving communication between children and adults and fostering children’s self-reflective awareness.

During early childhood, children engage in rough and tumble play and other behaviors that may be mistaken as aggression. Researchers agree that three components are critical in identifying behaviors as truly aggressive: there must be an observable behavior rather than an aggressive thought or feeling, there must be an intention to hurt the other, and the victim must be motivated to avoid the behavior (DeWall et al., Citation2012; Warburton & Anderson, Citation2015, Citation2018).

The main forms of aggression in early childhood are relational (e.g., the threat or act of social exclusion) and physical (e.g., the threat or act of hitting, kicking; Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995). The most commonly described functions of aggression are typically classified in a dichotomy of reactive (i.e., responding to a perceived provocation) and proactive (i.e., deliberately planning to harm; Evans et al., Citation2019). Because young children give higher preference to objects and resources within the social environment, acts of unprovoked, proactive aggression, such as snatching a toy from another child to satisfy a preference for that toy, are often evident (Ostrov & Crick, Citation2007). Children as young as 3 also engage in reactive forms of aggression, such as hitting another child who is annoying them or doing something they do not like (Ostrov et al., Citation2013).

Researchers have noted the limitations of categorizing aggression as either reactive or proactive (Bushman & Anderson, Citation2001) and have suggested a more nuanced approach that stresses three dimensions: the degree to which the goal of the aggression is to harm the victim versus benefit the perpetrator, the level of hostility or agitated emotion (e.g., hostile affect) that is present, and the degree to which the aggression is an automatic response versus a deliberate, thoughtful response (Warburton & Anderson, Citation2015, Citation2018). This approach may be useful for the assessment of aggression in young children as it considers cognitive processes and developmental factors that significantly affect a young child’s likelihood to aggress. This approach addresses the “why” of child behavior, with some children responding aggressively and others employing prosocial problem-solving strategies to solve social conflict (Swit et al., Citation2016). A dimensional approach supports the examination of multiple motives that children may have for their aggression.

It is surprising that few studies involve the child in direct explanations of their own aggressive behavior. Rather, the most common methods gather evidence from parents, teachers, and adult observers (Swit & Slater, Citation2021), who typically code behavior without checking with the child about the function or intention of their behavior (Pellegrini, Citation2004). In part, this may be due to researchers’ perception that intent is a subjective concept and is, therefore, difficult to assess in young children (Geen, Citation2001; Tremblay, Citation2000). This approach has neglected the child’s voice and insights regarding the social cognitive processes underlying their aggressive behavior, such as their intentionality and motivation. It also omits key insights into the ways that young people perceive their aggression as shaped by their observations of others within various environmental contexts, including community, media, and interactions with teachers, parents, siblings, and peers (Bandura, Citation1973; Rogoff et al., Citation2003). By incorporating children’s perspectives regarding their own behavior, a clearer understanding of the significance and interaction of these factors can be obtained.

Video-stimulated methodologies

Observational methodologies have been a mainstay in aggression research, successfully identifying both direct and indirect forms of aggression (e.g., Ostrov et al., Citation2013). Video-stimulated recall interview (VSRI) techniques are used as an enhanced observational method to elicit explanations of a person’s behavior, a feature that is not typically possible in other non-recorded observational data. Such methods have been used successfully in early childhood populations in previous research. For example, video-stimulated recall of behavior has been used in studies of peer interactions (Theobald, Citation2012) and other learning behaviors in young children (e.g., Meier & Vogt, Citation2015; Morgan, Citation2007). Given that aggression is a type of peer interaction, VSRI methods also may be appropriate to investigate the dimensional functions of aggression as interpreted and explained by the child.

In VSRI, recorded episodes of the child’s behavioral or learning interactions are used to stimulate recall or explanations from the child. The audio-visual recordings provide a specific and immediate stimulus that evoke emotions and feelings in the child, allowing the researcher to understand the interaction or behavior from the child’s perspective. Graue and Walsh (Citation1998) found that audio-visual recordings supported close “microanalysis” (p. 149) of the child’s behaviors, enabling analysis of nonverbal signs and body language in young children, including their use of spatial distance, for example.

Building on the arguments presented by Graue and Walsh (Citation1998), the VSRI method allows researchers to establish what children actually do in their social interactions, rather than what they can recall or believe they would do in hypothetical scenarios. Audio-visual recordings in naturalistic settings provide a record of the situational and contextual factors surrounding young children’s social interactions and can potentially be used to help the child identify facets of their aggressive behavior along the posited dimensions that are not otherwise captured in parent or teacher reports. This method affords the opportunity to observe all forms and functions of aggression in young children and does not rely on the child’s memory of a past event, which may be limited during this developmental period. Thus, the VSRI approach is potentially analytically and theoretically useful for understanding these behaviors because it allows a closer level of observation and greater precision in data coding than other approaches (Heath et al., Citation2010; Whitebread et al., Citation2009).

Use of this methodology with young children is supported by recognition that children are the main constructors and contributors of their social worlds (Cutter-Mackenzie et al., Citation2015) and aggression is best understood by exploring the context in which it occurs (Eriksen, Citation2018; Schott & Sondergaard, Citation2014). Further, the validity and reliability of child responses are enhanced due to the immediacy of viewing and responding to the visual stimuli of one’s own behavior. In contrast, isolated or belated post-event self-reports of aggression are prone to validity concerns with children responding in a socially desirable manner and reliability concerns with underreporting of one’s own aggressiveness, because young children can and often do understand that aggression is wrong (Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995; Crick & Werner, Citation1998; Swit et al., Citation2016; Swit & Harty, Citation2023). However, by showing the child their own aggressive behavior, VSRI provides a means for children to acknowledge, relate to, and account for their behavior, and to do so from their own perspective (Huitsing et al., Citation2019).

Increasingly, the competence of young children to report on their experiences has been accepted (Theobald, Citation2012), and young children are increasingly active participants in informing understanding of child behavior. Thus, this study uses VSRI to identify direct and subtle forms of aggressive behavior, and elicit children’s reports of their intentions and motivations to engage in these behaviors.

Relational and physical aggression

It should be noted that, historically, researchers have focused on physical aggression in early childhood because these behaviors, by definition, seem intended to cause harm, and are easy to observe (see Hay, Citation2017). Intent attributions have been far harder to determine in studies assessing relational aggression through observer judgments of children’s behavior (Ostrov & Keating, Citation2004). Relational aggression, unlike physical aggression, can be subtle and is often considered normative behavior during the early years (Swit et al., Citation2018). It may be more difficult to determine the purpose of relational aggression from observation alone because the motivation may not be immediately obvious to the observer. In contrast, the function of physical aggression is immediate (Little et al., Citation2003). Standardized coding systems commonly used in observation studies tend to code aggressive behaviors, including relational aggression, based on short observations of children in their social settings. The function of children’s behavior is often coded into dichotomous categories, proactive or reactive aggression, and children are not asked to explain the function of their own behavior. Although these methods are valid and can be useful in demonstrating the prevalence of aggression in early childhood settings, they may not capture components of the aggression phenomenon from the child’s perspective, may miss functions outside the reactive-proactive dichotomy, and may underestimate young children’s ability to explain their behavior. This is at odds with the growing recognition that young children are capable of holding opinions and ideas (Merewether & Fleet, Citation2014).

VSRI versus hypothetical vignettes

Assessment of young children’s understanding of intent is often based on hypothetical scenarios or vignettes. Children’s responses to vignettes are considered reflective of their intent attributions (Karadenizova & Dahle, Citation2017). While such approaches have some utility for examining intent attributions and response decisions, such effects will only be demonstrated if the child can personally relate to the hypothetical scenario (Dodge & Frame, Citation1982). In addition, vignettes often require a child to imagine a hypothetical scenario or aggressive behavior occurring and to then answer a range of questions related to their perceptions of the information provided in the scenario (e.g., Godleski & Ostrov, Citation2020; Smetana et al., Citation1999; Swit et al., Citation2018). A young child’s understanding of a vignette is dependent on both their verbal capabilities and their memory (Findlay et al., Citation2006). Thus, encoding, comprehending, and recalling the information; setting a fictitious goal; and making a decision about a fictitious vignette are likely to be very difficult for younger children. Young children are more capable of distinguishing between intentional and unintentional behavior when the vignette is very concrete and familiar to them (Katsurada & Sugawara, Citation1998).

The current study

This study advances understanding of young children’s aggressive behavior by repositioning children as knowledgeable contributors who are capable of expressing their views about their aggressive behaviors. We also respond to the call for researchers to employ fine-grained observational methods to assess the function of young children’s aggression (Heilbron & Prinstein, Citation2008). The primary research question of this study is: Can VSRI be used to elicit self-reported internal cognitions (i.e., intentions and reasons) related to children’s aggressive behavior that can be used to better understand the nature and function of their aggressive behavior? It is expected that VSRI will be a developmentally appropriate methodological tool to allow young children to describe their intentions and reasons for engaging in aggression. The second research question for this study is: What are the explanations children (in this sample) provide for engaging in these aggressive behaviors?

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach, initially using teacher behavior reports to identify subgroups of children based on their relational aggression levels. We identify two subgroups of children with high levels and average levels of relational aggression. Subsequently, qualitative observations and video-stimulated interviews were conducted with these identified subgroups to better understand the motivations behind, and functions of, their aggression. Although the focus of this study is relationally aggressive behavior, data were collected for instances of both relational and physical aggression, as there is often an inverse relationship between these two aggression subtypes (i.e., physical aggression predicts relational aggression but relational aggression does not predict physical aggression; Evans et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it was important to screen out children high in physical aggression, as this reflects a different behavioral profile and developmental concern (Evans et al., Citation2019). Given the absence of qualitative data examining the use of in-vivo examples, this research study and the findings are considered a novel and innovative addition in the study of relational aggression in young children.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 68 preschool children between the ages of 3.0 and 5.3 years rated by their teachers for levels of relational and physical aggression. Each of the seven preschools were located in suburban regions with similar mean socio-demographic indicators to the average population in New South Wales, based on household income data. Using teacher-reported data, two sub-groups of children were selected: nine children identified as engaging in high levels of relational aggression > 1 standard deviation above the population mean (Mage = 54.0 months, SD = 5.7 months) and seven children identified as having average levels of relational aggression or close to the population mean (Mage = 52.3 months, SD = 6.1 months). The age of the two groups was not statistically different (t (14) = −.58; p = .574), providing some confidence that both subgroups of children possessed comparable developmental abilities to engage in the VSRI. A small sample (n = 3) of children were identified as high on both relational and physical aggression. They were screened out of the sample because of the low co-occurrence of these behaviors and different behavioral profile expected of children who use both forms of aggression. The total sample and subgroup sample sizes of this study are similar to previous studies that have assessed relational aggression in young children (e.g., Crick et al., Citation1997, N = 65; Curtner-Smith et al., Citation2006, N = 44) and have used VSRI methodologies (e.g., Morgan, Citation2007, N = 48 and 42).

Procedure

As approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: #5201200783), the study sought consent from early childhood services, teachers, and parents for children between the ages of 3 and 5 years. Teachers completed the Preschool Social Behavior Scale – Teacher Form (Crick et al., Citation1997) for each participating child, with the aim of identifying high and average levels of relational aggression in the group of children. The descriptive statistics and standard deviation approach used to identify the two subgroups of children are described in Swit et al., Citation2016. During free unstructured play time, the researcher approached the focal child and invited them to participate in the study with the following invitation: “I am interested in learning about how children play together and I would like to record you playing with your friends. Is that okay?” Once an individual child assented, a wireless microphone was attached to the child’s clothing and the child was instructed to resume playing with their friends. The audio receiver was connected to the digital video recorder so that the audio and video data were recorded simultaneously. After each 20-minute observation, the wireless microphone was detached from the focal child and the child was invited to participate in the VSRI. The VSRI interview was audio-recorded, allowing for subsequent analysis and inter-rater coding.

Measures

Observation of social behavior during free, unstructured play

Children’s behavior was observed and coded using the ECPPOS procedure (Ostrov & Keating, Citation2004) during free unstructured play for 20 minutes on four different occasions over 1 month, resulting in 80 minutes of recorded data for each child. This differs slightly from recent studies (e.g., Perry & Ostrov, Citation2018), which involved eight, 10-minute observations over 2 months. The longer observation periods were used in this study to capture the unpredictable incidences of aggression that may be quite random and missed within shorter observation periods.

Similar to a previous study (Pepler & Craig, Citation1995), a digital video camera and wireless microphone were used to capture children’s vocalizations and behaviors during the observation sessions. This methodology is less intrusive than standard observations, allowing the researcher to be a more distal and impartial observer in the playground and classroom (Pellegrini, Citation2004). This has been shown to reduce child reactivity to the researcher, defined here as the focal child approaching and communicating with the researcher, direct eye contact from the focal child, and comments about the observation to other peers (Crick et al., Citation2006). Child reactivity to the methodology was very low for the observations in the current study (M < 2.0, SD < 1.12).

At the beginning of each observation, the researcher spent a few minutes listening to the focal child playing to ensure the audio was clear and gave children some time to become comfortable with having the microphone attached to their clothing. Once children appeared comfortable and resumed their regular play, the researcher started recording the observation. During each observation, the researcher concurrently observed and coded the focal child’s behavior, using the Early Childhood Play Project Observation System (ECPPOS) coding system (Ostrov & Keating, Citation2004) to identify incidences that would be replayed for the VSRI. The ECPPOS has demonstrated high reliability in past research (e.g., Ostrov & Keating, Citation2004). Two researchers coded a random sample of 40% (n = 26) of observations and found an acceptable level of inter-rater reliability for both relational aggression (ICC = .87) and physical aggression (ICC = .90) ratings.

Video-stimulated recall interview (VSRI)

The video footage of the focal child engaged in acts of aggression was taken with the concurrent use of the ECPPOS coding system to identify the aggressive incidents that would be used in the VSRI. The incidents chosen for replay included relationally and/or physically aggressive behaviors used by the focal child that (a) the researcher viewed as intentional, (b) included at least one other peer, and (c) were unambiguously aggressive (e.g., not consensual acts of rough and tumble play). The video recording was replayed to the child within 20 minutes of the initial recording to ensure children were able to discuss their goals and what they were thinking in each scenario, rather than focusing on the recall of events. The child was invited to participate in the VSRI with the following invitation: “I saw you doing some really interesting things with your friends. Do you want to come and watch the video and talk about some of the things you were doing with your friends?” Before the VSRI interview commenced, children were given 1 minute of giggle time (Pirie, Citation1996) to manage any form of anxiety they may experience from watching themselves on the video. The child was asked a series of open-ended questions that assessed their attributions of behavioral intentionality (“Did you … on purpose?”), and the function or reasons for engaging in aggression (“Can you tell me what happened there?”; “Can you tell me why you chose to do that?”). These types of questions have been shown to be effective in eliciting accurate and comprehensive reports from children in naturalistic settings (Ponizovsky-Bergelson et al., Citation2019).

The child’s reactions during the VSRI, such as body language and emotive expression, were also noted during the replay and questioning about the aggressive incident. Where such reactions were evident, these provided the researchers with a greater understanding of the child’s response to the VSRI and their reaction to the aggressive behavior being displayed in the video. For instance, a child retreated by leaning backward and looking down from the video replay when he was asked why he said he would stop being friends with his peer. This child’s non-verbal cues communicated a sense of guilt or wrongdoing that may not have been captured by playground observations alone.

Depending on the child’s responses to the VSRI, additional prompts were posed to the child until the researcher clearly understood the intentions and motivations of the child’s aggression. An example of an additional prompt was, “Do you think it is okay to tell a friend that you don’t want to play with them?,” informing the researcher of the child’s evaluation of their behavior. From the observations conducted, a total of 46 incidences were replayed, ranging from 50 seconds to 3 minutes in length, and the questioning procedure remained the same for each session. Each child from the two subgroups participated in at least one VSRI, with the majority of the children (n = 11) responding to three or more incidences. These interviews were audio-recorded, allowing for a fine-grained analysis of children’s responses. Each interview was coded using NVivo for a priori themes consistent with (a) the ECPPOS coding system (i.e., functions of behavior); (b) the three dimensions of aggressive function – goal-seeking, negative/agitated affect, and conscious deliberation; and (c) the exploration of the child’s intention and their understanding of their aggressive behavior (see for the final codes used).

Table 1. Coding system used to code children’s observations and VSRI responses.

Children’s qualitative responses during the VRSI were analyzed and interpreted independently, to reflect the utility of VSRI as a method to capture and understand the intentions and motivations of young children’s aggression and to understand common themes across children with high levels and average levels of relational aggression. The same two researchers who assessed the observations of children also coded children’s interview responses. Inter-rater reliability was acceptable with raters agreeing on coding of 89% of children’s interview responses across all VSRI observations. Where there was a disagreement between researchers or the aggressive incident had a high level of complexity and ambiguity, a discussion about the child’s behavior and explanations took place until a consensus was reached. In these cases, other aspects of children’s behavior and VSRI were analyzed, such as the child’s body language, emotive expression, non-verbal cues, and the length of the aggressive incident. Shorter aggressive incidences were typically coded as requiring lower levels of proactive thought and rationale consideration because the function of the behavior was delivered with immediacy.

Results

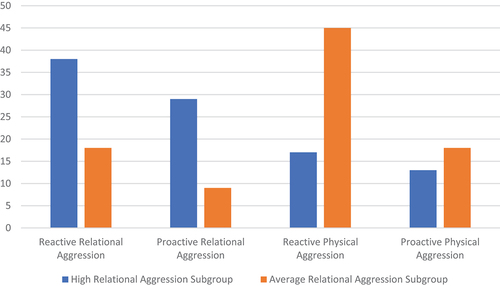

Reflecting their a priori identification, it was evident that children rated by their teachers as engaging in high levels of relational aggression, compared to the average group, used similar amounts of aggressive behaviors overall (N = 24 versus 22 instances), but used more relationally aggressive behaviors (N = 16 versus 6 instances) and used fewer acts of physical aggression (N = 7 versus 14 instances) to resolve conflict (both ps < .05). The remaining instances of aggression, which involved limited occurrences of verbal aggression, were not included in the VSRI, because while physical aggression is often inversely related to relational aggression, the relationship of non-relational verbal aggression to relational aggression is unclear and harder to interpret. presents the forms and functions of aggression based on children’s explanations of their behavior.

Figure 1. Forms and functions of aggression from children’s explanations for engaging in aggression.

Intentionality of aggressive behaviors

During the analysis, it was possible to code intentionality in 43 of the 46 recorded aggressive behavior incidences. However, in three of the videos, when asked about intentionality, the children responded with uncertainty, stating “I don’t know.” One of these children may have been using this as an avoidance technique because they also requested to watch another segment of the video, indicating that they did not want to watch the scenario being replayed. Avoidance techniques such as this may suggest that the child is aware of their negative behavior and is attempting to detract from these behaviors by requesting to move on. The two other responses occurred when the children were distracted by other events occurring in the early childhood center. As such, these responses were not included within the analysis.

Children who engaged in high levels of relational aggression acknowledged that 20 of the 24 incidences (83%) involved goal-directed, intentional behavior. An example is described below in an incident involving a boy from the relational aggression subgroup.

The focal child approached another younger child who was playing with a cooking pot. The focal child forcefully snatched the pot from the child and walked away. The other child started crying.

“Did you take the pot on purpose or by accident?”

“By purpose … . I just knew I had to have that pot from the baby.”

“And what did you want to do with the pot?”

“I just wanted to put some spiky things [spiny tree pods] in it.”

Children with average levels of relational aggression acknowledged intentional aggressive behavior in 15 of the 22 (68%) incidences reviewed. The following description involves a boy from the average relational aggression subgroup.

The focal child and another child were playing in a life-size car. The focal child was singing and the other child asked him to stop singing. The focal child continued singing. The child hit the focal child on the head and the focal child responded by hitting the child on the head forcefully, making the other child cry.

“Did you hit her on the head on purpose or by accident?”

“On purpose … . She hit me first so it’s okay to hit her back.”

“And what happened then?”

“She crying.”

“Oh, she started crying. She must have been feeling sad.”

The frequency of incidences acknowledged as intentional was higher for children in the relational aggression subgroup compared to children in the average relational aggression subgroup. The frequency of incidences seen as unintentional (i.e., by accident) was higher for children in the average relational aggression subgroup compared to children in the relational aggression subgroup. However, a chi-squared test for independence (with Yates Continuity Correction) indicated no significant association between aggression grouping and perceived intentionality, χ2 (1, n = 43) = .38, p = .540, phi = .15. All children acknowledged that they used the aggressive behavior(s) and in 35 of the 46 (76%) replayed incidences, children acknowledged the behavior was wrong. In a small number of incidences (n = 8; 17%), children indicated that their aggression was acceptable and justified (such as the above example where the focal child justified his aggression because a peer had hit him first).

Explanations of aggressive behavior

Children’s behaviors were described and objectively classified by the researcher and a second rater as serving reactive or proactive functions and as being relational or physical forms of aggression (ICC’s > .87). Based on this analysis, children’s reasons for engaging in aggression included reactive and proactive functions for both relational and physical forms of aggression and a further category that identified children choosing to enact the behavior: “Because I wanted/did not want to.” These children were not able to provide any further explanation about the function of their aggressive behavior. In addition, the researchers examined the three dimensions of aggressive function – the aggression was to harm the victim versus benefit the perpetrator, agitated/hostile emotion was present, and there was evidence of conscious deliberation.

Relational aggression

In the high relational aggression subgroup, nine of these behaviors could be classified as reactive and the remainder (n = 7) as proactive. In the average relational aggression subgroup of children, four of the six acts of relational aggression could be classified as reactive and two as proactive.

Children typically justified their use of reactive relational aggression by referring to a provocation/event that caused them frustration or hurt. For example, the following explanation for reactive relational aggression was provided by a girl in the relational aggression subgroup.

The focal child was playing with blocks on the floor and another child intentionally kicked the blocks over while also playing on the floor. The focal child stood up and said to the child, “I’m not going to be your friend anymore if you don’t stop it” and then walked away. The child was left to play alone and his facial expressions suggested that he was upset by the focal child’s reaction.

“Why did you say you weren’t going to be his friend anymore?”

“Because he was kicking the blocks away and that’s not nice.”

Here there was a clear provocation, a high level of reactivity, an increase in hostile/agitated emotion, a goal to harm the victim rather than benefit the aggressor and a low level of rational, conscious consideration that was underpinned by the short length of the social exchange (26 seconds). The interpretation of this scenario also took into consideration the focal child’s actions after she walked away from the child. Shortly after (approximately 3 minutes) the first incident, the focal child returned to the blocks and asked the child to play with her. This was coded as the focal child trying to make amends with the child, suggesting some remorse for her reactive relational aggression. Whether this remorse was self-serving (e.g., attaining a social goal) or other-serving (e.g., compensating the peer for her rejection) is unknown.

Children’s explanations of their proactive relational aggression were more varied. In the following example of a girl in the relational aggression subgroup, the aggression simply served to obtain something desired and there seemed to be an understanding that the aggression would manipulate or cause harm to the other child(ren):

Two girls were riding on a bike. A girl, “AJ,” was steering the bike and the other girl, “ML,” was riding on the back. The focal child wanted to join in and requested a turn on the bike. AJ explained that they should take turns. The focal child responded by following the girls around telling them that she would not be their friend unless she was immediately allowed a turn on the bike. She added further statements such as, “Did you know if you go down that hill you will hurt yourself? ML will hurt herself.” The focal child continued to follow the girls while repeatedly saying, “Well I’m not your friend.”

“Why did you tell them you wouldn’t be their friend?”

“Because I wanted to go on the back of AJ … . I didn’t want to wait my turn.”

“Do you think it is okay to tell your friends that you won’t be their friend?”

“I don’t care … but I was supposed to have a turn after ML and I didn’t want to have a turn after ML. ML isn’t my friend. AJ only wanted to be ML’s friend.”

This incident continued with the focal child’s use of a range of relationally aggressive strategies (i.e., threats, demands, reputational slurs) until she obtained her goal of a turn on the bike. However, the aggression was not purely instrumental; the video footage illustrates progressive increase in the negative emotional state of the child during a short period of individual reflection. Shortly after this period of reflection, the focal child reentered the situation and the aggressive interaction escalated, resulting in the social goal attainment for the focal child when AJ told ML to get off the bike and allowed the focal child to sit on the bike, while also engaging in loud visible displays of joy showing that she wished to demonstrate or “show off” her goal achievement. In achieving this goal, the victim of the relational aggression was the pillion passenger ML, who was visibly upset by being asked to leave the bike by the bike rider AJ. The bike rider had acquiesced to the threats of the focal child. Despite the display of sadness in the victim, the focal child displayed a high, even exaggerated state of positive emotions and appeared satisfied her goal had been obtained. This scenario presents the focal child switching between reactive aggression to proactive aggression to attain her social goal. The length of this incident (2.54 minutes) underlined the deliberation and reflective processes of the focal child, and the increased purposefulness or proactive use of her aggression in achieving her goal.

Overall, the VSRI provided insights into incidents where relational aggression served both proactive and reactive functions, as well as helpful information related to the three dimensions of aggressive function. In six of the nine proactive relational aggression incidences, the VSRI data revealed that proactive relational aggression often led to personal and social goal attainment (satisfaction or social dominance) for the aggressor. In contrast, the reactive relationally aggressive behaviors were less premeditated (i.e., more automatic than thought through), were typically accompanied by sudden raised levels of hostile or agitated emotion, and functioned more to harm the victim than to obtain the desired goal.

Physical aggression

Among the relational aggression group, four of the seven physically aggressive behaviors could be classified as having a reactive function and the remainder (n = 3) as having a proactive function. In the subgroup of children with average levels of relational aggression, 10 of the 14 acts of physical aggression could be classified as having a reactive function and the remainder (n = 4) a proactive function.

A boy in the average-relational aggression subgroup explained his reactive physical aggression as follows:

Three boys were engaged in independent play on play equipment designed as an obstacle course. After successfully completing the balance stepping stones, the focal child proceeded to move through a tunnel-shaped piece of play equipment. However, another child was already inside the tunnel. The focal child reacted by losing his temper and aggressively pushed the boy through the tunnel.

“Why did you push the boy through the tunnel?”

“I didn’t like it when he was being too slow on purpose and I wanted to rush. I pushed him to make him hurry up.”

This example of reactive physical aggression shows the focal child reacting with physical force because he did not approve of the other child “being too slow.” Like the previous reactive example for relational aggression, there was no indication that the physical aggression was premeditated or planned. However, the focal child’s behavior reflected a sudden raised level of hostile/agitated emotion, as evidenced by their frustration at the other child’s behavior. Their aggression, while reactive, did however reflect a clear and rapid cognitive process of goal formation – to make the other child go faster. Thus, the function was not to hurt the other child but to further this goal. This is an interesting case of reactive, hostile aggression that also involves a cognitive process to serve an instrumental goal and a purpose other than retaliation. Findings such as this underline the importance of moving away from the reactive/proactive dichotomy of aggression (Bushman & Anderson, Citation2001) and moving toward the more nuanced triple dimension of function approach that better explains complex sets of cognitions and motivations, such as in this instance. The recording of the incident lasted 13 seconds, indicating that the provocation and subsequent cognition to form a goal and react aggressively were quickly enacted.

A boy in the relational aggression subgroup described his motivations for an act of proactive physical aggression in the following way:

A group of boys were playing in the sandpit with a set of dinosaurs. After some time, the focal child kicked another child’s leg, resulting in the child crying. The focal child took the dinosaurs from the crying child and started playing with them himself.

“Why did you kick your friend?”

“I didn’t want him to play with us anymore.”

“Why didn’t you want to play with him anymore?”

“He had the tyrannosaurus and I wanted to play with it.”

This example of proactive physical aggression showed the focal child using physical force and dominance to obtain a toy he wanted to use. This suggests that the focal child perceived this form of aggression (i.e., kicking) as an effective way to remove another child from his play, allowing the focal child to achieve his personal goal. This incident took place over 1.10 minutes, indicating that it may have been planned and purposeful.

Summary of the key findings

The successful capture of young children’s interpretations of their aggressive behavior using VSRI demonstrates its value as a tool for analyzing the evolving social cognitive processes that underlie children’s aggressive behavior. For example, where researchers had coded aggressive behavior as reactive, this was corroborated by children’s reasoning that their behavior was in response to other provocations (e.g., kicking over the blocks) or barriers (e.g., a child moving slowly through a tunnel). In some instances, reactive aggression also served an instrumental goal, demonstrating that young children’s aggression can reflect reactive and proactive functions simultaneously. Across all enacted aggressive behaviors, the three dimensions of aggressive functioning provided a more nuanced understanding of a child’s intent and motivations. These findings demonstrate the value of VSRI and the need to go beyond a dichotomous view of the functions of child aggression.

Although young children’s intentional use of aggression has been questioned by researchers, VSRI-assisted children in this study to indicate whether their actions were intentional or unintentional. In most instances of aggression, children in both subgroups reported that their behavior was intentional. Young children were also able to provide explanations for their aggressive behavior, further highlighting the value of using VSRI alongside naturalistic observations as a research tool to better understand the intent and functions of young children’s aggressive behavior.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate the use of VSRI as a developmentally appropriate methodological tool to understand the internal cognitions (i.e., intentions and reasons for engaging in aggression) that may underlie young children’s aggression. The results suggest that children 3–5 years old often have insight into their intentions and motivations regarding their aggressive behavior and that the VSRI methodology was a helpful tool to identify this information by allowing young children the opportunity to provide clear explanations about why they had been aggressive.

In the present study, young children reported engaging in aggression with the intent to cause harm or to achieve a personal goal, acknowledging in most cases that their aggressive behaviors were wrong. One of the most crucial aspects of the VSRI was its ability to enable more comprehensive firsthand reflection and explanations of aggression, based on children’s viewpoint of the situation. This likely enhances the reliability of the data. Thus, VSRI may be a developmentally appropriate addition to teacher, parent, and observer reports to understand the behaviors of children. A small number of children indicated that their aggressive behavior was justifiable and acceptable, with such behaviors used in response to frustration or provocation.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first study to directly ask preschool-age children about the functions of their own behavior after being filmed engaging in actual aggressive behavior. This child-centered design enabled the researchers to construct meaning, not based on researcher assumptions of intentionality and motivation, but by including the salient perspectives of the child who enacted the aggression. Further, the use of recorded observations of children’s actual behavior, followed by VSRI, allowed for a more reliable assessment of children’s intentionality, as children responded to provocation scenarios that were concrete and familiar to them (Katsurada & Sugawara, Citation1998), rather than responding to fictitious or abstract hypothetical scenarios (Orobio de Castro et al., Citation2002; Welsh & Dickson, Citation2005). These findings suggest that there is value in directly asking children about their intentions rather than relying only on an observer’s judgment of intentionality.

Some children in this study reported that they engaged in proactive relational and physical aggression to achieve a goal (e.g., social status or obtain an object). These explanations obtained through the use of VSRI reflected the children’s ability to purposefully plan their aggressive behaviors and were often accompanied by the child having positive feelings and a positive evaluation of the outcomes of their aggression. These findings further demonstrate useful application of the three function dimensions of goal directedness, hostile affect, and deliberation. In some incidences, children’s aggression served both reactive and proactive functions, and sometimes reactive aggression was also goal directed. Thus, the commonly used reactive-proactive dichotomy of aggression was not always supported in this study. The additional prompts used during the VSRI helped the researcher to understand the child’s motivations and intentions beyond the evaluation of their behavior. These findings highlight that young children’s aggression is complex and multifaceted. Therefore, adopting measures that capture the different dimensions, situational and contextual factors that relate to children’s intentions and motivations to engage in aggression will provide researchers with a more nuanced understanding of children’s behavior.

In the majority of the proactive incidences, children showed evidence of satisfaction or social dominance gained from their aggressive behavior. These children (predominantly in the relational aggression subgroup) were cognizant of the behaviors that would more effectively harm their peers and described the adaptive purpose that their proactive aggression served. This finding is consistent with a small number of studies that suggest children who engage relational aggression may have a fairly sophisticated social cognitive understanding (Little et al., Citation2003; Swit et al., Citation2018) and may use a combination of prosocial and coercive strategies in their social interactions (Hawley, Citation2003). In contrast, while children’s reactive aggression also provided evidence of intentionality, these explanations were less suggestive of forward-thinking and planning. Rather, reactive aggression related to hostile and retaliatory behaviors that were used in immediate response to another child’s provocation and were more commonly used by children in the average-relational aggression subgroup. These behaviors are also more typical of other reports of children’s aggression during the early years (Evans et al., Citation2019), often appearing impulsive and affect driven.

These findings support the proposition that both subgroups of children process social information and respond to provocations differently. More specifically, children who engaged in high levels of relational aggression in this sample demonstrated engagement in aggression in planned and thoughtful ways and seemed to have a greater repertoire or “database” of scripts and behaviors they could employ to respond to provocation or achieve certain goals. These cognitive processes were identified in the gentle VSRI-facilitated probing of children’s intentions and reasoning.

Implications

Several implications arise from the current study. First, the use of video footage to aid children’s recall of their intentions and thoughts during social interactions provided nuanced information about why the children were aggressive and about their intentions related to hurting the other child. This approach was developmentally appropriate for preschool-age children and demonstrated that young children can offer insight into their intentions, can describe what is important to them in their social interactions, and can recall why they engaged in aggression. Thus, the VSRI procedure was a valuable methodology for gathering data on children’s motivations for their behavior in this age group – data that have been unobtainable in other studies using standardized observation coding schemes (Orobio de Castro et al., Citation2002). Second, by actively listening to children’s perspectives, communication between the adult and child are enhanced. By understanding children’s perspectives, adults are able to more accurately understand and respond to the motivations and intentions of children’s behaviors. This knowledge, in turn, helps to identify the specific needs of the child and provide developmentally appropriate guidance and intervention. Finally and most significantly, when children are encouraged to reflect on their own behaviors and express their perspective, it enhances their self-awareness. Indeed, reflecting on the consequences and impact of their behavior on others, may help young children in the development of empathy and self-regulation skills.

Limitations and future research

This study was conducted with specific limitations. The methodology relied on the observation of behavioral interactions as they unfolded in an unstructured early childhood environment. A limitation of all time-restricted observational studies is the fact that children may or may not have used more or less of their typical range of behaviors in this time period. It is possible such observations capture more or fewer behavior types than actually occur in a preschool day. Having said this, the use of remote audio-visual observation did allow for the identification of subtle behaviors, and the motives and goals of complex social behaviors, that may not always be identified in studies relying on traditional observational methods. The focus on children who engaged in high levels and average levels of relational aggression also may have limited the variability in children’s behavior and resulted in a small sample size. As with all observational studies, the method remains labor-intensive and time-consuming and the VSRI required the researcher to follow up with the child immediately after the observations were collected to ensure the child could better recall their thoughts and feelings around the recorded incident. This immediacy of follow-up is more time demanding than other methods that employ interviews and hypothetical vignettes. However, VSRI does support the identification of specific details of children’s actual social interactions with a higher level of scrutiny and precision (Heath et al., Citation2010; Whitebread et al., Citation2009).

Given that observations and VSRI are both labor-intensive methods, it would be interesting for future research to compare these methodologies (i.e., hypothetical vignettes versus observation only versus observation and VSRI) to determine whether greater detail or different types of information are elicited from each method. Similarly, future use of this methodology may include independent observers’ ratings of children’s intentional and unintentional aggressive behavior to compare these to children’s VSRI responses. This information would be useful in understanding whether VSRI elicits specific forms of responding in children above and beyond the effects arising from common observational methods. Future research should employ interactive and child-centered methods to gain insights from the child’s perspective, with possible implications for theory development. For example, utilizing VSRI with children of different age groups can provide new theoretical insights about a range of social behaviors and phenomenon among young people, including complex interactions between bullies, bystanders, defenders, and victims, and the social cognitive processes within complex group dynamics. Furthermore, the VSRI method allows researchers to obtain children’s self-reports of their behavior in a range of applied developmental and educational contexts (Morgan, Citation2007). However, it is important to consider the suitability of this methodology for older children, as they may be more likely to exhibit socially desirable responses. Therefore, we encourage researchers to continue to incorporate VSRI as a tool for capturing children’s perspectives across different developmental periods, while remaining open to potential adaptations required for younger and older children and adults.

In summary, the current study demonstrated that VSRI provided a developmentally appropriate tool that provided young children with the agency to express their perspectives regarding why they chose to engage in aggression. It was possible to capture children’s actual aggressive behavior and engage in a dialogue that allowed some conclusions to be drawn about their motivations and attributions around why they choose to use aggression in their daily social interactions.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank those children who were willing to spend valuable hours allowing us to observe their social interactions and interview them for this project. We also thank the individuals who assisted us in cross-coding hours of data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Cara S. Swit, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice-Hall.

- Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review, 108(1), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273

- Crick, N., Casas, J., & Mosher, M. (1997). Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.579

- Crick, N., & Grotpeter, J. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131945

- Crick, N., Ostrov, J., Burr, J., Cullerton-Sen, C., Jansen-Yeh, E., & Ralston, P. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational and physical aggression in preschool. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.006

- Crick, N. R., & Werner, N. E. (1998). Response decision processes in relational and overt aggression. Child Development, 69(6), 1630–1639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06181.x

- Curtner-Smith, M. E., Culp, A. M., Culp, R., Scheib, C., Owen, K., Tilley, A., Murphy, M., Parker, L., & Coleman, P. W. (2006). Mothers’ parenting and young economically disadvantaged children’s relational and overt bullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-005-9016-7 2

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A., Edwards, S., & Quinton, H. (2015). Child-framed video research methodologies: Issues, possibilities and challenges for researching with children. Children’s Geographies, 13(3), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.848598

- DeWall, C. N., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2012). Aggression. In H. Tennen, J. Suls, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (2nd ed., pp. 449–466). Wiley.

- Dodge, K. A., & Frame, C. L. (1982). Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive boys. Child Development, 53(3), 620–635. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129373

- Eriksen, I. M. (2018). The power of the word: Students’ and school staff’s use of the established bullying definition. Educational Research, 60(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2018.1454263

- Evans, S. C., Frazer, A. L., Blossom, J. B., & Fite, P. J. (2019). Forms and functions of aggression in early childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(5), 790–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1485104

- Findlay, L., Girardi, A., & Coplan, R. (2006). Links between empathy, social behavior, and social understanding in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.07.009

- Geen, R. G. (2001). Human aggression. Open University Press.

- Godleski, S. A., & Ostrov, J. M. (2020). Parental influences on child report of relational attribution biases during early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 192, 104775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104775

- Graue, M. E., & Walsh, D. J. (1998). Studying children in context: Theories, methods and ethics. Sage Publications.

- Hawley, P. (2003). Strategies of control, aggression, and morality in preschoolers: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 85(3), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00073-0

- Hay, D. F. (2017). The early development of human aggression. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12220

- Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research: Analysing social interaction in everyday life. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435385

- Heilbron, N., & Prinstein, M. J. (2008). A review and reconceptualization of social aggression: Adaptive and maladaptive correlates. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(4), 176–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0037-9

- Huitsing, G., van Duijn, M. A. J., Snijders, T. A. B., Alsaker, F. D., Perren, S., & Veenstra, R. (2019). Self, peer, and teacher reports of victim‐aggressor networks in kindergartens. Aggressive Behavior, 45(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21817

- Karadenizova, Z., & Dahle, K. (2017). Analyze this! Thematic analysis: Hostility, attribution of intent, and interpersonal perception bias. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1068–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517739890

- Katsurada, E., & Sugawara, A. I. (1998). The relationship between hostile attributional bias and aggressive behavior in preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13(4), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(99)80064-7

- Little, T. D., Jones, S. M., Henrich, C. C., & Hawley, P. H. (2003). Disentangling the “Whys” from the “Whats” of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(2), 122–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000128

- Meier, A., & Vogt, F. (2015). The potential of stimulated recall for investigating self-regulation processes in inquiry learning with primary school students. Perspectives in Science, 5, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pisc.2015.08.001

- Merewether, J., & Fleet, A. (2014). Seeking children’s perspectives: A respectful layered research approach. Early Child Development and Care, 184(6), 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.829821

- Morgan, A. (2007). Using video-stimulated recall to understand young children’s perceptions of learning in classroom settings. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930701320933

- Orobio de Castro, B., Veerman, J., Koops, W., Bosch, J., & Monshouwer, H. (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 73(3), 916–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00447

- Ostrov, J., & Crick, N. (2007). Forms and functions of aggression during early childhood: A short-term longitudinal study. School Psychology Review, 36(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087950

- Ostrov, J. M., & Keating, C. F. (2004). Gender differences in preschool aggression during free play and structured interactions: An observational study. Social Development, 13(2), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.000266.x

- Ostrov, J. M., Murray-Close, D., Godleski, S. A., & Hart, E. J. (2013). Prospective associations between forms and functions of aggression and social and affective processes in early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 116(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.12.009

- Pellegrini, A. D. (2004). Observing children in their natural worlds: A methodological primer (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. (1995). A peek behind the fence: Naturalistic observations of aggressive children with remote audiovisual recording. Developmental Psychology, 31(4), 548–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.548

- Perry, K. J., & Ostrov, J. M. (2018). Testing a bifactor model of relational and physical aggression in early childhood. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-017-9623-9

- Pirie, S. (1996). Classroom video-recording: When, why and how does it offer a valuable data source for qualitative research? [Paper presentation] Annual Meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Panama City, FL.

- Ponizovsky-Bergelson, Y., Dayan, Y., Wahle, N., & Roer-Strier, D. (2019). A qualitative interview with young children: What encourages or inhibits young children’s participation? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691984051. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919840516

- Rogoff, B., Paradise, R., Arauz, R., Mejía, C.-C. M. & Angelillo, C. (2003). Firsthand learning through intent participation. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 175–203. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118

- Schott, R. M., & Sondergaard, D. M. (2014). Introduction: New approaches to school bullying. In R. M. Schott & D. M. Sondergaard (Eds.), School bullying: New theories in context (pp. 1–17). Cambridge University Press.

- Smetana, J. G., Toth, S. L., Cicchetti, D., Bruce, J., Kane, P., & Daddis, C. (1999). Maltreated and nonmaltreated preschoolers’ conceptions of hypothetical and actual moral transgressions. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.269

- Swit, C. S. & Harty, S. C. (2023). Normative beliefs and aggression: The mediating roles of empathy and anger. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01558-1

- Swit, C., McMaugh, A., & Warburton, W. (2016). Preschool children’s beliefs about the acceptability of relational and physical aggression. International Journal of Early Childhood, 48(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-016-0155-3

- Swit, C. S., McMaugh, A. L., & Warburton, W. A. (2018). Teacher and parent perceptions of relational and physical aggression during early childhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0861-y

- Swit, C. S. & Slater, N. M. (2021). Relational aggression during early childhood: A systematic review. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101556

- Theobald, M. (2012). Video-stimulated accounts: Young children accounting for interactional matters in front of peers. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 10(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X11402445

- Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502500383232

- Warburton, W. A., & Anderson, C. A. (2015). Social psychology of aggression. In J. Wright & J. Berry (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 373–380). Elsevier.

- Warburton, W. A., & Anderson, C. A. (2018). Aggression. In T. K. Shackleford & P. Zeigler-Hill (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality and individual differences: Vol. 3 applications of personality and individual differences (pp. 183–211). Sage.

- Welsh, D. P., & Dickson, J. W. (2005). Video-recall procedures for examining subjective understanding in observational data. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.62

- Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Pasternak, D. P., Sangster, C., Grau, V., Bingham, S., Almeqdad, Q., & Demetriou, D. (2009). The development of two observational tools for assessing metacognition and self-regulated learning in young children. Metacognition and Learning, 4(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9033-1