ABSTRACT

Washington Okumu (1936–2016) went to South Africa in April 1994 as part of the Kissinger–Carrington team charged to mediate Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP)-African National Party (ANC)/National Party (NP) differences on the interim constitution. A few days after the collapse of that effort he emerged as the individual broker for a behind-the-scenes agreement that brought the IFP back into South Africa’s democratic elections. His appearance was not a fluke. Rather, it was the culmination of a career with a conservative Christian network that was active in track-two diplomacy and constitutional theory from the 1970s through the 1990s. This article looks at this genealogy of compromise and mediation and treats it as a mode of politics in its own right, with interests, a constituency and a strategy. Okumu’s network envisioned South Africa as an interracial Christian society living under a Biblically sound legal system. They did not try to preserve apartheid, but held that federalism, free markets and protection for the heteronormative family were divinely ordained. These concerns provided essential context to Okumu’s appearance and signal a mode of politics that was not interested in either segregation or the project of deracialisation, but he was thoroughly conservative on social and cultural matters.

Washington Okumu came out of nowhere, twice. Before long, he disappeared again.Footnote1 His first appearance was just two weeks before South Africa’s first democratic elections of April 1994. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) was refusing to participate in the country’s first democratic election and the violence of its refusal was threatening the transition. Because of the deadlock, the African National Congress (ANC) assented to mediation by an international team led by US secretary of state Henry Kissinger and former British foreign secretary Lord Peter Carrington. Kissinger, Carrington and constitutional experts from North America, Europe and India arrived on Monday 11 April 1994 to facilitate a solution. Their effort began with a press conference at the Carlton Hotel.Footnote2 Interrupting the proceedings was the late arrival of an unknown black man, imposing in stature, who made his way to the front of the room. Proceedings halted as he hugged Kissinger and took his place at the table. He introduced himself as Washington Aggrey Jalong’o Okumu and said: ‘I am very much humbled to be here and to make my remarks following my former teacher at Harvard, Dr Henry Kissinger. I am the Ambassador-At-Large of the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy in Kenya and have been invited by the major parties to be the Advisor Extra-Ordinary to the mediation process’.Footnote3

It was beyond the skill of Kissinger and Carrington to broker the entry of the IFP into the poll; they left after two-and-a-half days. But unknown to the world, the latecomer Okumu stayed in South Africa and participated in behind-the-scenes negotiations. He then appeared again at a second press conference on 19 April, where he served the honoured role of witness to the Memorandum of Agreement signed by Nelson Mandela, Mangosuthu Buthelezi and F.W. de Klerk that provided for the IFP to join the elections at the eleventh hour ().Footnote4

Figure 1. The 19 April 1994 signing of the memorandum of agreement (left to right: Buthelezi, De Klerk, Mandela, Okumu) (used with permission; Associated Press LIC-01418921)

Okumu received credit for averting calamity. He had known Buthelezi for many years, and their friendship and shared Christian beliefs created the trust that was lacking until then. Headlines such as ‘How the Chief Was Turned’ and ‘Bringing in Buthelezi’ laid out Okumu’s contribution.Footnote5 Contemporary observers and later historians revised these reports about Okumu’s centrality in the negotiations: yes, he had an influence on Buthelezi, but the explanation for the 19 April agreement lay in the longer politics of the transition.Footnote6 Because he was not the actual hero of the agreement, his presence at the second press conference has become a bit of white noise in the eventful history of April 1994. I happened to remember it because I arrived in the country on 20 April as a United Nations (UN) observer for the elections and was much relieved by the news that the IFP would be campaigning rather than fighting. I remained vaguely intrigued by the Kenyan who was said to have accomplished this feat and was reminded of him over two decades later through my teaching.Footnote7

In fact, Okumu’s presence at the two press conferences was the culmination of years of experience and effort, not his alone. He was an interesting character with an unusual life, but the explanation for his appearance has as much to do with his associations as with him as a person.Footnote8 He came to prominence with a small international group of conservative Christians who hoped to influence South Africa towards a legal dispensation that adhered to biblical law. South Africa would leave behind racial segregation but keep what was, in their understanding, its Christian values: a market-based economy, devolution of power from the central state, and protection for the heteronormative, patriarchal family.

The method to secure this conservative future was mediation and consensus building among the Christian majority. It was not a large movement, and it is difficult to assess its significance; after all, the ANC and National Party (NP) participated in mediation and compromise for their own reasons. Because negotiation seems an obvious idea and because it is so thoroughly assimilated into understandings of the transition, its history as an independent concept has not received critical examination, especially as it comes to light through an actor as unlikely as Okumu. But as South Africans note the incompleteness of the transition and as historians stepped back from the metanarrative of struggle, a space may have opened to look at the genealogy of compromise and mediation, to recognise it as a mode of politics in its own right, with interests, a constituency and a strategy.

Okumu’s associates hailed from three entities: the American Fellowship, better known as the organisers of the Washington Prayer Breakfast; a British think tank, the Newick Park Initiative (NPI); and a South African evangelical effort, African Enterprise (AE). They operated in separate national political cultures and held to several Protestant traditions. They never united in a single organisation. They differed on the desirability of a public presence. Furthermore, their involvement evolved as South African politics changed, so comparisons across time are uneven. But friendship and a hope to intervene in South Africa’s future united this informal alignment of evangelicals. Facing dialectical oppositions, Okumu’s network envisioned themselves both breaking down racial obduracy and neutralising revolutionary momentum. These were religious leaders rather than politicians, but they connected to politicians. Their way to reconcile opposition was simple: face-to-face consensus building. Time and again, they reached right (a near reach) and left (a connection that took more effort) and offered themselves, and especially African colleagues, including Okumu, as facilitators. Mediation, not struggle, was to be the engine for leaving the flawed past without veering towards overly secular solutions.Footnote9

This is the context for Okumu’s appearance in South Africa, where he joined in negotiation at the highest level and could weigh in on the matter of reopening constitutional negotiations. What happened, and what did not happen, was through a complex and contingency-driven process of compromises made and confrontation averted. New perspectives on the nature of the negotiated settlement, the costs of compromise, and the limits to the concessions emerge when the proponents of mediation become historical actors in their own right. Making this case requires biographical work and close attention to actors and positions that have fallen out of fashion.

The Making of a Mediator

Elsewhere I have told the story of how Washington Aggrey Jalong’o Okumu (1936–2016), a Luo from western Kenya, developed international connections.Footnote10 He knew both Tom Mboya and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who arranged for him to join the 1958 ‘airlift’ of Kenyan students to US universities. Also in that group was Barack Obama, Sr, whom he knew. Most likely with the support of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), he received admission to Harvard University.Footnote11 In August 1960, he made a tour of several African countries – paid for by the CIA, he told me – with the longest stop in Lumumba’s Congo. He graduated from Harvard with a bachelor of arts degree in economics in 1962 and matriculated for post-graduate study at Cambridge University, but he never fulfilled the requirements for the master of arts degree listed on his curriculum vitae.Footnote12

Back in Kenya in 1963, he started work with a parastatal, the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation. His troubles began, he recounted, in 1965 when his pastor, Tom Houston of the Nairobi Baptist Church, spoke to him about corruption in the government, including the railways. Inspired by his minister, he said, he uncovered improprieties and was then himself imprisoned on charges of corruption. (Houston declined to corroborate this account.)Footnote13 Released after Mboya’s assassination and Oginga Odinga’s arrest in 1969, Okumu concluded that an ambitious Luo like himself had no future in Kenya.

In 1971 American backers secured Okumu a position with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) in Vienna. His South African involvement traces back to this time. In the 1970s, Houston introduced him to a group of US Christians: the Fellowship, best known for hosting the annual Washington Prayer Breakfast. The Fellowship, led in the late twentieth century by Doug Coe, has been a wellspring of conservative evangelical influence in US politics and international relations.Footnote14 Attending for the first time in 1973, he met influential South Africans who were active in the Fellowship’s South African wing and built friendships with them: Buthelezi, then Chief Minister of KwaZulu; and Michael Cassidy, the founder of the Pietermaritzburg-based mission organisation, AE.Footnote15

Okumu’s correspondence with Coe affirmed his Christianity, but their letters did not detail why they cared about South Africa.Footnote16 The Fellowship is a theologically flexible but circumspect organisation that does not issue public statements. It has not explained its involvement in South Africa, but it aligned with that of other white conservative Christians in the US after the 1960s. They connected with the apartheid government as fellow anti-communists. Among some, a festering discontent with the success of the US civil rights movement created sympathies with segregationist South Africa. American and British support grew out of the ‘culture wars’ in those countries.Footnote17 Whatever their commitment to protecting white status, the new right also intended to defend cultural and social traditionalism. For having held off the libertines and liberationists for so long, South Africa was a model.Footnote18

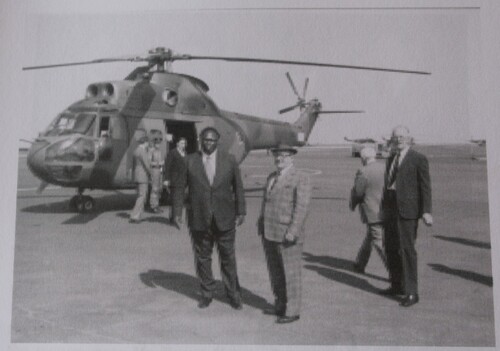

The Fellowship archives reveal that the organisation involved itself with the apartheid government to support Prime Minister B.J. Vorster’s détente policy. Vorster aimed to convince political leaders north of the Zambezi that white-dominated South Africa could belong in an ethnically and politically plural Africa.Footnote19 The Fellowship played an important role in the initiative, providing introductions for Vorster’s visit to Liberia in 1975, his second to an African country.Footnote20 They also introduced Okumu to members of Vorster’s cabinet who visited Vienna. In August 1976 Okumu made a secret trip to Pretoria. The mission was, he said, organised by South African intelligence.Footnote21 He requested, and the leading lights of the South African security establishment took him on, a helicopter tour of Soweto, still smoldering after the uprising two months earlier ().Footnote22 Okumu was vague about the issues, but South Africa and the US looked for a settlement in Rhodesia, and Vorster was perhaps willing to make a region-wide bargain that included Mandela’s release.Footnote23

Figure 2. Departing on a helicopter tour of Soweto in August 1976 (Left to right: South African Police General G. Prinsloo; Minister of Cooperation and Development Piet Koornhof Okumu; Minister of Justice, Police, and Prisoners Jimmy Kruger; South African Police General Mike Geldenhuys; and Bureau of State Security Director-General H.J. van den Bergh) (‘The African Option’, 114; used with the permission of Washington Okumu)

Whatever Vorster’s plan, it was ambitious enough to involve Julius Nyerere, President of Tanzania and leader of the Frontline States. Okumu became the emissary to Nyerere, travelling secretly in October to meet with him. A Harvard friend arranged the contact. But Nyerere refused to agree to any proposal. Okumu returned to Pretoria with that news. In 1976 and 1977, he also travelled to Rhodesia for secret negotiations.Footnote24 These initiatives may look like failed trial balloons sent up by white minority governments clinging to power, but the outreach to Nyerere, at least, was noteworthy. The Fellowship, the South African government and Okumu hoped that white minority governments and African nationalist movements would find common ground.

In his writing and his 2016 interviews with me, Okumu always emphasised his ties with the ANC, but I cannot corroborate them for this early period. After 1982, his link with them conceivably strengthened when UNIDO funded a programme for training in woodworking, metalworking and mechanical industries at an ANC school at Mazimbu, Tanzania.Footnote25 In 1985, Okumu lost his position at UNIDO for unspecified reasons.Footnote26 He took on short-term work, as a lecturer (earning the honorific ‘Prof.’) and as a technical advisor to the Zambian government.Footnote27 His mid-life professional crisis was severe. Not only did he lose his day job, but as Pretoria left détente behind, its need for him declined. As South Africa opened politically, the Fellowship’s approach of working covertly with international heads of state also became less effective. In May 1987, Okumu moved to London, where an associate of the Fellowship hosted him while he looked for employment.Footnote28

Christian Constitutionalism

Okumu’s appearance among the Kissinger–Carrington team was possible because of his association with some actors who have registered little in histories of South Africa’s transition. A British Christian organisation dedicated to South African issues, the NPI resuscitated his career. NPI retrospectives assert that it made significant contributions to the transition, but it has received no attention from historians.Footnote29 The NPI was not a British version of the Fellowship. It did not involve itself with diplomacy on behalf of the South African government and it proclaimed the ‘complete unacceptability’Footnote30 of apartheid. Still, it never connected with the British anti-apartheid movement.Footnote31 Saul Dubow’s broadly dialectical description of international politics has sketched out this territory that was not pro-apartheid but also not part of the anti-apartheid movement. As Dubow sees it, the often-secretive efforts to sway international opinion towards South Africa involved South African sympathisers conceding part of the argument to the anti-apartheid position. Pro-South African apologists ‘seldom defended apartheid directly – which was testimony in itself to the success of anti-apartheid campaigning’.Footnote32 And so, the pro-South Africa and pro-apartheid stance mutated into an anti-anti-apartheid position. The NPI arguably fits into this space. Although it accept that apartheid would end, it did not often condemn the racial exclusions, violence and exploitation of the mid-1980s. It tried to influence how they ended and to mitigate the vision that the anti-apartheid movement held for the new society. It cautioned that imposing sanctions would lead to ‘the creation of an autarchical siege economy, and a closing of the ranks of the white community against internal and external pressure’.Footnote33 Promoting peacebuilding, it held, was less a matter of addressing ‘current grievances’ than encouraging ‘those involved to look beyond the present conflict to ways of living peacefully together in the future’.Footnote34 But to characterise the NPI only as reactionary and anti-anti does not do justice to its goals and strategies. The NPI hoped to create its own synthesis, based on Christianity.

Michael Schluter, a British economist born in Kenya, founded the NPI. He had already established the Jubilee Centre, a Christian initiative in Cambridge best known for the ‘Keep Sunday Special’ campaign. The campaign aimed to bring British law in line with an updated and secular interpretation of Old Testament commandments.Footnote35 Rather than religious observance of the Sabbath as dictated in Deuteronomy, it sought to preserve Sunday blue laws in England and Wales. Rather than God’s judgement, the stated rationale for the regulation was worker and family protection.Footnote36 The NPI’s activism in South Africa was similar in that it sought contemporary adaptions of biblical laws.

In 1986, Schluter began a collaboration with Jeremy Ive, a South African doctoral student in history at Cambridge University. Ive has described his youthful enthusiasm for neo-Calvinist reformational philosophy.Footnote37 Central to this school is Abraham Kuyper’s idea of ‘sphere sovereignty’, which holds that separate spheres – including but not restricted to family, art and commerce – were each divinely ordained and responsible only to God, not the state. Historians of South Africa know the concept of sphere sovereignty well for its influence on apartheid ideology.Footnote38

Kuyper’s thought actually does not map consistently onto racial ideology. An anti-apartheid Kuyperian position was plausible. As evidence, consider that the black liberation theologian Allan Boesak appreciated Kuyper.Footnote39 For his part, Ive reports having argued that sphere sovereignty was ‘antithetical to the policy of Apartheid’.Footnote40 Kuyper’s thinking is adaptable. It has also supported libertarian Christianity. Building on his original interest to foster a plural society under a modern state, some have framed the state as one among many sovereign spheres and argue for its disempowerment. In the US, one reading of Kuyperian theology has fueled a theology of ‘dominionism’, the vision of reconstructing God’s legal order on earth.Footnote41 The NPI was never explicitly dominionist. While it advocated for government structures that adhered to their interpretation of the Bible, it did not call for exclusive control of the state by Christians.

In the mid-1980s, constitutional theory provided a sandbox for modeling South Africa’s future. Especially active were those who fell between the NP’s racially segregated tricameral system and the ANC’s plan for a unitary state.Footnote42 Joining in, Schluter and Ive produced a treatise, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa: Christian Principles and Practical Feasibility, which systematically worked through five constitutional options, some very unlikely. These included power-sharing in a unitary state, a federation of four economically comparable multi-ethnic states, a federation of seven ethnically defined states, partition into two separate countries, and a confederation with the former High Commission territories.Footnote43 Following the fashion of the 1980s, many of these possibilities incorporated consociational variants, meaning they defined electoral rolls around ‘communities of interest’ – which in South Africa were racial groups.Footnote44 Schluter and Ive’s assessment of each constitutional model was detailed and even-handed, presenting pros and cons of each in the light of their consonance with God’s character (as they understood it).Footnote45 The document did not use the language of ‘sphere sovereignty’ but echoed it by asking whether diverse constituencies could coexist without one dominating the other.

Schluter and Ive’s intended audience was Christian but divided. They hoped to bring together those on the right who called for reconciliation and those on the left who sought structural change.Footnote46 By coming together, they said, Christians could solve the impasse and ensure a better future.

The concern is not so much to find the perfect ‘solution’, which given the nature of politics in general and the South African situation in particular, might never be possible; rather, the concern is to minimize the present and prospective evils of any outcome of the present South African situation.Footnote47

The most effective way the West could help South Africa, Schluter and Ive observed, might well be to sponsor proposals for constitutional outcomes. In March 1987 they organised ‘an invited group of committed Christians of high standing’ to gather at the Newick Park Estate in England.Footnote49 The first participants were politically and religiously conservative black and white men whose politics were legal in South Africa but who had yet to talk much to each other. White participants included Cassidy (who had urged South African Christians to move towards reconciliation),Footnote50 Willem de Klerk (the brother of the future president) and Willie Esterhuyse (a Stellenbosch University professor). Black participants included Enos Mabuza (the leader of the KaNgwane Bantustan), and Stanley Mogoba and Caesar Molebatsi (both churchmen). None of the early participants was in government or was an identifiable member of the ANC or Inkatha. The NPI brought this conversation to South Africa in 1987 with a meeting in Pietermaritzburg,Footnote51 but it is not clear how they interacted with the consociational constitutional innovations – the Buthelezi Commission (1980–1982) or Natal-KwaZulu Indaba (1986) – emanating from KwaZulu and Natal.Footnote52

The intransigence in South African politics in the mid-1980s created space for facilitated conversations, now known as track-two mediation.Footnote53 These included go-betweens, most notably peace activists such as H.W. van der Merwe and Richard Rosenthal, non-governmental organisations such as the Institute for a Democratic Alternatives in South Africa (IDASA) and the US Ford Foundation, as well as the mining company Consolidated Goldfields. Consgold hosted the best known of these from 1987 through 1989.Footnote54 Thabo Mbeki and Esterhuyse, the Stellenbosch University professor who had attended both the US Prayer Breakfast and NPI meetings, met at the Mells Park Estate in England to hammer out how the ANC and the government could begin negotiations.Footnote55 By the late 1980s, the NPI had turned its attention beyond Christians and evolved into something closer to a secular low-level track-two forum, less to hammer out differences than to demonstrate the possibility for common ground. After the unbanning of the ANC in South Africa, its representatives participated in NPI meetings.Footnote56 At least one named participant, Charles Dlamini, had associations with the KwaZulu establishment, but records do not reveal a relationship with Inkatha.Footnote57

Okumu attended his first NPI event in November 1987 and became director of the organisation six months later. By early 1990, he was its executive director. The NPI held meetings two or three times a year to discuss South Africa’s future. Records of their discussions reveal that its conversations involved a range of opinions. Black participants at the first meeting registered that they ‘did not accept the view that South Africa was a country made up of racial minorities’. Moreover, participants concluded that ‘any settlement that enshrined cultural diversity [was] completely unacceptable in the present situation’.Footnote58 Okumu also objected to proposals for political set-asides for racial minorities.

One NPI participant, Fanie Cloete, has recalled his speaking out at the February 1990 meeting. Cloete, who had served as a government constitutional planner in the 1980s, presented a paper on minority rights that provoked sharp criticism from Okumu that it amounted to white domination in another form.Footnote59 One central plank of the ANC platform was registered at an NPI meeting: ‘The unitary option was seen by some as the only real alternative to the prescriptive classification on the basis of race which underlies the policies of the present South African Government’. Federalism, however, received the religious imprimatur. They deemed it ‘distinctively Christian’ because it ‘recognized the fact of basic human sinfulness, and the need for restraints to be placed on any exercise of political power’.Footnote60 The consensus seems to have been to remove ethnic or racial group protection at the national level but to devolve decision-making about the new society to the provincial level, where local convention would hold sway.

An October 1990 conference on land reform provided a space to discuss economic issues. The meeting acknowledged injustices but was chary about redistribution. Representatives of the ANC were at this meeting and critiqued proposals for market-based reforms.Footnote61 Okumu weighed in that the task was ‘to put right the long period of injustice but within a market-based framework’.Footnote62 This may seem to reflect predictable political oppositions, but the NPI found it significant that soon after this meeting ANC stopped advocating for nationalisation.Footnote63 That the NPI was the chief influence on ANC economic policy shatters credulity, but compromise around economic policy was taking place.

A note in NPI records that does not map on a racial political landscape was their concern for safeguards for the family.Footnote64 One meeting concluded with a caution that ‘individual rights are not used to undermine the God-given institution of the family’.Footnote65 ‘Protecting the family’ stands among conservative Christians for protecting parental, especially fatherly, control.Footnote66 The position was well-established among Afrikaner nationalists,Footnote67 but as late as the 1990s, the ANC constitutional guidelines also leaned patriarchal when stating ‘The tribe, parenthood, and children’s rights shall be protected’.Footnote68 Unlike the nationalisation of land, this is an area where the ANC and Okumu’s Christian networks would diverge.

Christian Facilitation

The NPI positioned Okumu to appear on the Kissinger–Carrington team not just because of its interest in constitutional planning, but also because of its efforts at mediation and facilitation. Fred Catherwood, a Conservative British politician and supporter of the NPI, once wrote, ‘There are times when a movement of Christian opinion is all that stands between a country and moral disaster’.Footnote69 In 1989, the NPI took on influencing South African Christian opinion. It launched the Jubilee Initiative (JI) within the country, describing it as a ‘networking consensus’ based in ‘the precarious “middle” of divided South African society’. The JI would take ‘Biblical principles as the framework for starting and conducting those negotiations’.Footnote70 Writing in that same year, the evangelist Cassidy expressed a similar aspiration. Christians, he said, should ‘become part of a think-tank movement’. There would be ‘hundreds of heterogeneous cells bringing together English and Afrikaner, black and white, young and old’ at the grassroots level, speaking to leaders at a second tier, who would then ‘feed their thinking to the very top, to which they would have access’. He imagined ‘the heart-beats of a saving movement of Christian political opinion’, resonating ‘in the chest of this nation’. This was to transcend apartheid divisions; he envisioned a ‘national consensus of all races’.Footnote71 These visions went beyond the work of the NPI by envisioning popular interracial Christianity as a political force.

Coming out of nowhere with hopes to reshape the political landscape from the bottom up, without acknowledgement of the specific needs of black South Africans or recognition of their rightful leadership, the JI provoked suspicion. Critical articles in SouthScan and The New Nation exposed its funders as United States Agency for International Development, Standard Bank and ‘private donors’. They also alluded broadly to South African intelligence and foreign involvement.Footnote72 Not least, a comment from a South African Council of Churches spokesperson criticised the JI for ‘by-passing structures which have struggled with the people’.Footnote73 This was true: the NPI not only lacked struggle credentials, it tried to create a space where they did not matter. Christianity was what would matter. In the fallout, British members of the JI board resigned and the organisation dropped the attempt to marshal public opinion. No mobilisation among conservative Christians could be sufficient to divert the secular anti-apartheid movement in the late 1980s. The NPI turned towards higher-level track-two work, concentrating on mediation between politicians rather than public consensus building.Footnote74

Okumu’s role at the NPI was to cultivate relationships. Esterhuyse recorded conversations suggesting that Okumu could be a thoughtful, even shrewd, observer of politics.Footnote75 An important part of his job seems to have involved connecting with the ANC. NPI records show him meeting with Mbeki and Aziz Pahad in London in 1989. Pahad has confirmed that he did meet with Okumu, but could not recall details.Footnote76 This raises questions about who else he was talking to. Okumu told me that his CIA work had ended by the late 1980s.Footnote77 Esterhuyse told me that South African intelligence was wary of him as an outsider.Footnote78

How did Okumu understand his involvement with the NPI? His memoir was prone to detail his individual achievements without providing much context about the issues at hand.Footnote79 He was not a theologian nor constitutional theorist. While he referenced the divine in his writing, he did not elaborate how Christianity shaped his approach to South Africa. The description of the NPI in his memoir never even acknowledged it as Christian.Footnote80 The best insight we have into his inspiration for this work comes from an anecdote from the mid-1980s about the transformative effect of hearing the great populariser of African history, Basil Davidson. From Davidson, Okumu learned the roots of European anti-black racism. These lessons on history held a strongly personal message for him, because they explained ‘why the world considered me, an African, inferior and incapable of any significant achievement, my educational background and experience notwithstanding’.Footnote81 Solutions to Africa’s problems, he resolved, lay in traditional knowledge systems, but only in the right hands, meaning among ‘indigenous Africans of a high calibre’.Footnote82 He experienced racism and identified proudly as an African who was qualified to move at high levels. His was an individualistic nationalism performed in international circles through exhibitions of expertise. It was well suited to working with non-Africans who were not seeking a broad political base. For their part, Okumu’s conservative friends would have gained legitimacy by having a credentialed African among them.

By 1989–1990, track-two mediation at the highest level became an interest of all the members of Okumu’s network. Two of these efforts prefigured the 1994 Kissinger–Carrington mediation by involving Okumu. First, the US Fellowship again attempted to mediate between the white minority government and the forces that opposed it.Footnote83 In 1989, SouthScan and The New Nation reported that Coe (the leader of the Fellowship) and four South Africans, including Cassidy, were in contact with Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda to arrange a meeting of regional heads of government. The New Nation characterised the effort as ‘white men planning an ambitious “black-led” initiative to start negotiations on the future of South Africa’.Footnote84 It also involved a ‘Fellowship representative’ who sounds a lot like Okumu.Footnote85 A year later, with the ANC unbanned and exiles returning, the NPI floated a proposal originating with Mabuza to host a summit at the highest level, between Buthelezi, de Klerk and Mandela. Okumu met Buthelezi in London to discuss the possibility.Footnote86 But nothing came of it. As public meetings between the government and the ANC began, the need for facilitation by foreigners receded. The NPI held its last conference in January 1991.Footnote87

The South African fellow traveller of the Fellowship and NPI, Michael Cassidy, continued the quest for reconciliation in an ideology-free ‘third way’ between apartheid and revolution.Footnote88 To that end, Cassidy’s mission, AE, hosted conversations between those who had been proponents of each. It organised ‘Harambee ‘92’, which brought teams of churchmen from east and central Africa to South Africa for ‘a ministry of encouragement’. In the buildup to the September 1993 confrontation between the ANC and the Ciskei government, Tanzanian AE evangelist Emmanuel Kopwe mediated in Bisho. Cassidy himself, as we will see, engaged both the ANC and IFP. He also held bosberade (Afrikaans for ‘conversations in the bush’) with representatives from a wide spectrum: the ANC, NP, South African Communist Party, IFP, Pan-Africanist Congress, Azanian People’s Organisation and Afrikaner Volksunie. A Kenyan, George Wanjau, served as the neutral presence among them.Footnote89 The bosberade were not for theological or policy discussions as the NPI had been, but for personal connection. This was track-two diplomacy as pastoral engagement: encouraging politically well-positioned men to have better relationships and to follow God’s plan.

Here a tendency that has been only implicit until now emerges: this network treated race as an anomaly among Christians in a moderate country. Setting aside race could be productive; the bosberade helped South African men who had been enemies become real to each other.Footnote90 But this vision for an interracial Christian centre did not erase race. These approaches would not have dislodged the power of whiteness, especially in a free market economy. Okumu knew racism, but in these circles he could claim respect as a Christian Harvard-educated international civil servant. He did not explain the NPI’s political theology in his memoir, but he summarised its importance to his career. It connected him to ‘a distinguished group of senior politicians who, because of my seniority and experience, greatly valued my advice and gave me freedom to develop the negotiations […] in an atmosphere full of trust and camaraderie’.Footnote91 Thus, his Africanness provided evidence that race could and would be transcended. In the middle of South Africa’s bifurcation, these Christians and Okumu valorised connection.

Debating the 1993 Interim Constitution

Now, the narrative turns from obscure actors to better-known constitutional debates. Without much involvement from Okumu himself, Okumu’s allies expressed concerns about the emerging settlement. The negotiations at Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) I in 1991 were difficult, but CODESA II the following year was disastrous. The subsequent stalemate was violent and foreboding until parties returned to constitutional talks in April 1993. By then, the NP and the ANC both favoured a modified unitary system that provided for provincial units under an empowered national government. Like the NP, Buthelezi and Inkatha, now called the IFP, also left consociational measures behind, but they now sought a greater devolution of federal power.Footnote92 The IFP constitutional vision became clear in the December 1992 draught constitution for the ‘state’ of KwaZulu/Natal. The ‘Federal Republic of South Africa’ (as it renamed the country) would hold responsibility only for foreign affairs, external defence, trade and monetary policy.Footnote93

But Buthelezi did not advocate for a federal structure in the constitutional negotiations in the 1993 Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF).Footnote94 The IFP walked out of the MPNF in June and never returned. Without IFP input, the MPNF agreed in November on an interim constitution that provided for a decentralised unitary system with a strong central government.Footnote95 And so, the IFP refused to sign up to contest the elections scheduled for April 1994. As a concession, in March an amendment to the constitution changed the name of Natal province to KwaZulu-Natal.Footnote96 Still, the IFP did not register as a political party contesting the election.

Because of the intransigence of the IFP, the story of constitutional politics is usually told around the federal-unitary question. Still, other issues also required negotiation. First was gender. Under pressure from women activists, the ANC Constitutional Committee committed to non-sexism.Footnote97 Yet it kept the principle that ‘the family, parenthood, and equal rights within the family shall be protected’. This provoked concerns: what sort of family merited protection: urban civil, rural customary or township informal? Nuclear or polygamous? And what about a family with same-sex parents? Feminists within the ANC objected that ‘protecting’ family within patriarchal and homophobic structures threatened to restore conventional gender roles.Footnote98 In response to these points, the Bill of Rights endorsed the principle that New South Africa would not only be antiracist but also leave behind patriarchal, heterosexual and able-body norms. It detailed 14 categories of persons protected against discrimination:

No person shall be unfairly discriminated against, directly or indirectly, and, without derogating from the generality of this provision, on one or more of the following grounds in particular: race, gender, sex, ethnic, or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, or language.Footnote99

The second issue was God. The leading South African in Okumu’s network, Cassidy, also appealed to the ANC Constitutional Committee to argue that the preamble to the constitution should declare ‘that the state is not autonomous, but has a transcendent point of accountability to the divine’.Footnote100 But the interim constitution of December 1993 contradicted these hopes. The preamble stated, ‘In humble submission to Almighty God’,Footnote101 but left out the matter of accountability to the divine, because – as Cassidy groused – of the ‘0.05 per cent of South Africans who are atheists’.Footnote102 He also objected to the expansive list in the Bill of Rights clause because it could ban discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. This, he warned, opened the country to same-sex marriage. Marriage, he maintained, was a biblically ordained union between man and woman. He feared that protection by gender opened a possibility for legalised abortion.Footnote103 A year after the elections, Cassidy argued that deracialising rights did not justify such measures:

Many are embracing the view that to liberalise on race issues, as was so right and necessary, requires us also to abandon family values and liberalise on every issue relating to sexual behaviour, pornography, abortion on demand, Sunday observance, gambling, prostitution, and what is appropriate in media and entertainment. Thus we are in danger of throwing out the baby of Judeo-Christian values and ethics with the bathwater of apartheid.

Such moral laxity beneath the surface of our apparent political and social success will imperil us as surely as it imperiled Judah immediately after Uzziah’s death.Footnote104

Schluter did not comment directly on South Africa, but he retained constitutional interests. By 1993, he had developed a concept called ‘relationism’. This vision for contemporary society originated in Old Testament law, which was meant to uphold relationships between regions and sections of society, and within the family.Footnote107 Schluter’s inspiration lay in his religion, but he believed these ideas had broader purchase. He and a co-author, David Lee, produced a secular version of relationism in their book The R-Factor. Without referring to Christianity, they explained that modern ‘Western’ mega-communities had eroded relationships.Footnote108 Federalism, as a government system that shortens distance by devolving power to local communities, provided a way to improve their quality.Footnote109 In a 1994 article, he explained what was at stake in the question of Biblical law: ‘The rise and fall of nations can generally be understood as a reflection of their conformity to God’s moral law’. Moreover, ‘obedience to God’s law in a society may be said to result in economic prosperity and political status … . A society which turns its back on God’s law will experience confusion and rebuke… . In particular, there will be acute suffering at the hands of invading armies’. In contrast, a secure nation would ‘give a central role to Biblical law in the ordering of society.Footnote110 This article did not refer explicitly to South Africa, but it suggests what Schluter thought was at stake in the political transition.

These men accepted that apartheid would rightly end. Yet they kept their distance from the popular movement to end it. Their concern was whether its ending would threaten Christianity and therefore the stability of the country. Having failed to create a moderate Christian political base, they could only direct their efforts to those at the top, where they had had some success in facilitating conversations. With the ANC’s shift towards market economics, godless socialism was no longer a threat, but South Africa’s interim constitution was not in accordance with God’s law on federalism and the family. The Kissinger–Carrington mission offered an opportunity to make a case to those empowered to reconsider the constitution. Reconstructing this concern does not suggest that Okumu, Cassidy and Schluter were insincere about peacemaking,Footnote111 but it shines light on why their route away from strife lay through a constitutional commission.

Okumu did not mention the interim constitution in his memoir. He never stated an opinion on the Christian qualities of federalism, nor on a divinely ordained family. By 1993, he was leaving South Africa behind and turning towards Kenya, which appeared to be liberalising. Oginga Odinga had founded a new political party, the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), and Okumu became its Ambassador-at-Large in London. He resigned from the NPI and moved to Nairobi, where he took a position to promote a foundation for African scientific development, a brainchild of the entomologist Thomas Odhiambo. When Odinga died in January 1994, Okumu announced his interest in the FORD nomination for the parliamentary seat.Footnote112

The Brief Life of International Mediation

The story of 1994 until just a week before the elections is one of brinkmanship and dramatic reversals. Okumu weaves through this history as a faint and minor thread. After 1993, the ANC and the NP were no longer locked in opposition. The IFP remained on the outside, pursuing a politics of refusal rather than struggle. The result was acute strife. From July 1993 through April 1994, an average of 461 people were killed every month in political violence.Footnote113 As 1994 progressed towards the April election, the IFP’s refusal to join the elections boded catastrophe. ANC opinion was split, with Mbeki and Jacob Zuma advocating for engaging the IFP.Footnote114 The ANC and the NP both began negotiations with King Goodwill Zwelithini and Buthelezi.Footnote115 At a summit with Buthelezi in Durban on 1 March, Mandela agreed that the ANC would consider international mediation in return for the IFP registering for the elections. And thus, without NP or government involvement, international facilitation led by Kissinger and Carrington came into play.Footnote116

Support from Anglo-American brought the Consultative Business Movement (CBM) into the process. Founded in 1988, the CBM was an alliance of leaders in business, labour unions and the United Democratic Front/ANC. Connecting to earlier mediation efforts, Theuns Eloff of IDASA and the JI became its executive director.Footnote117 Like the NPI and JI, it meant to promote respectful conversations between individuals, hoping they would convey their trust and insight to the opposing camps.Footnote118 By 1994, Colin Coleman was CBM’s acting executive director. In March 1994, he became the secretariat to the international mediation.Footnote119

Because the NPI had not been close to the ANC, it had played a background role in the track-two diplomacy of the 1980s. Finally, with mediation at hand, Okumu, the well-credentialed African with a professional history in an organisation that facilitated consensus building, became a promising candidate for involvement. But Okumu was in Kenya, building his political career.

When Cassidy elicited an invitation from Frank Mdlalose to send in a nomination for the team, he contacted Schluter, whose mother, a white Kenyan, made the case to Okumu that he should present himself in South Africa. They swayed him to lay groundwork for that possibility. Okumu’s memoir claims that he consulted or attempted to consult with Nyerere, Joaquim Chissano of Mozambique, and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe about his addition to the mediation team, but he received ‘lukewarm’ responses. If he was telling the truth, he was saying that these leaders of the Frontline States declined to endorse him as the African representative to this effort.Footnote120

As unpromising as these efforts were, Okumu’s Kenyan political career was even less hopeful. On 24 March, it became clear that the nomination for Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s seat would go to his son Oburu.Footnote121 This made all the difference to Okumu’s star turn at the press conference. With his Kenyan ambitions neutralised, he agreed to visit South Africa. The lack of support from African leaders posed a conundrum, but he reasoned that the mediation fell outside Organisation of African Unity (OAU) jurisdiction and therefore he need not feel held back. Invitations from Buthelezi and Mandela would hold sufficient authority. Okumu recounts that he made two trips to South Africa to secure his inclusion on the team. On Sunday, 27 March, he arrived and met with Ziba Jiyane of the IFP, Minister of Home Affairs Danie Schutte, and ‘most of the senior ANC personnel’. The only ANC leader he named was Jacob Zuma, and it is telling that for all of Okumu’s claims of connection to the ANC, Cassidy was the conduit to Zuma.Footnote122 Okumu also recounted that he reunited with the friend made two decades earlier at the Washington Prayer Breakfast, who had featured little in his memoir before this point. Buthelezi purportedly asked him, ‘Where have you been all this time, my brother. Anyway, I knew that one day you would come’.Footnote123

It was proving as hard for the IFP and ANC to cooperate on mediation as on anything else. True, they agreed on a list of experts from Italy, India, Canada, Germany and the US, including one African American. (The membership was conspicuous in its complete lack of women and Africans.)Footnote124 But the ANC and IFP still could not agree on the topic or process. Enclosed in their separate invitations, they sent different versions of the terms of reference to the team.Footnote125 How could mediation proceed if the parties did not concur about what was under consideration? Awaiting a single set of terms, the international team delayed their arrival.Footnote126

From the sidelines, Cassidy made the case for delaying the election for at least a month to give mediation more time.Footnote127 The difficulty in setting terms and the absence of Africans on the team provided Okumu one last opportunity. He rushed back for a 24-hour visit on 6 April to ‘personally see the ANC and IFP top decision makers’ (who remained unnamed).Footnote128 On 8 April, de Klerk and Mandela met with Buthelezi and King Zwelithini at Skukuza rest camp in the Kruger National Park to discuss IFP demands for Zulu sovereignty and constitutional recognition for the king. The ANC and NP acknowledged the king’s significance and offered him a symbolic role in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.Footnote129 The king and IFP rejected this, but all parties agreed to endorse international mediation.Footnote130 After this meeting they added Okumu to the team, not as a full member, but as a special advisor.Footnote131 Coleman recalls that Zuma made this proposal.Footnote132

At last, on 10 April, the ANC led by Mbeki and the IFP led by Joe Matthews finally settled on the issues. There was one point on citizenship rights, seven on provincial powers and one on ‘the demands of His Majesty the King of the KwaZulu Nation, with respect to the restoration of the Kingdom of KwaZulu, with specific regard to the right of self-determination of his people on a territorial basis’.Footnote133 The mediators were to serve as facilitators but not adjudicators. What this meant was not at all clear. The terms did not stipulate whether they had power to postpone the election. Mbeki kept this contentious problem off the table because Buthelezi assured him that the IFP would accept the date if they resolved all other matters.Footnote134 This ‘fudge’ was a problem for others in the ANC, including Cyril Ramaphosa.Footnote135 It also alarmed the government. The chief NP negotiator Roelf Meyer later framed the entire effort as ‘an international attempt […] to delay the election’.Footnote136

Mediation opened on Monday with the Carlton press conference and Okumu’s first grand entrance. Although he was not a full member of the team, he worked himself into a prominent position. The next day, a photograph of the team showed him seated between Kissinger and Carrington. He was the only black African in the room ().

Figure 3. The Kissinger–Carrington mediation team (towards the rear, from left to right: Colin Coleman, Henry Kissinger, Washington Okumu and Lord Carrington) (used with permission; Washington Okumu Personal Papers)

And so, through long preparation and dedicated effort, Okumu joined a hastily constructed, small and weak initiative to do in a week what the ANC and the government could not do over months, even years, of trying: create conditions that would convince the IFP to put its name on the ballot.

They never came close. The risk that international mediation would countermand the process was too great for the ANC and NP. The international visitors learned at the opening press conference that the government was now entering the talks. The entry of a new party required new terms of reference. Together, the ANC and NP insisted on excluding the election date from consideration.Footnote137 The mediators and representatives from all parties were scheduled to depart for a bosberaad in a game lodge, but without clarity about whether the date of the election was on the table, they remained in Johannesburg. Okumu recalled that on the morning of Thursday 14 April, Coleman informed the team that their work was over. Okumu phoned Cassidy to tell him he was returning to Kenya, but the evangelist told him to stay. As Cassidy reconstructed their conversation, he said, ‘The Lord has not brought you thus far to let the whole thing fall apart now … . Kissinger and Carrington may have to go, but not you. You need to soldier on alone’.Footnote138

Okumu’s Intervention

Even then, the process that would put Okumu at the table with Mandela, de Klerk and Buthelezi was unimaginable. A meeting with Buthelezi on Thursday evening pulled him back into the process, at its centre. Buthelezi put Okumu in touch with two white advisors to the IFP who were also well connected with Minister of Home Affairs, Schutte: Danie Joubert, Deputy Secretary General in the KwaZulu government, and Willem Olivier, a Bloemfontein advocate. On that evening these three worked out a plan to present to Buthelezi.Footnote139 Okumu had meant to meet Buthelezi very early the next morning at the Carlton Hotel, but overslept. Having phoned ahead, he raced to Lanseria airport to catch Buthelezi before the plane departed, but he was unsuccessful. The plane, however, turned back. In the blush of Okumu’s fame, the media fixated on this meeting at the airport. Was this because Buthelezi learned en route Okumu was waiting for him in the airport lounge or because of a malfunction warning (which later turned out to be false)?Footnote140 By all accounts, the conversation between Buthelezi and Okumu in the airport lounge was pivotal. Having gained Buthelezi’s confidence Okumu connected later on Friday with Coleman of the CBM, who drew in the Independent Electoral Commission and the ANC. With these connections, over the next four days, Okumu moved to the centre of the final negotiations that put the IFP on the ballot.

His success had everything and nothing to do with the years of precedent and positioning by him and his friends. Everything, because he had been a staff member at the NPI, in discussions about constitutional planning, and he embodied the phenomenon of an African Christian facilitator in the mode of Cassidy’s bosberade. Everything, because he was known to government intelligence, a London contact of the ANC, and an old acquaintance of Buthelezi’s. This does not require that these were deep connections. When queried about his knowledge of Okumu’s past, F.W. de Klerk replied: ‘As far as I can recall, I did not at that time have any prior knowledge of Okumu’s previous activities in shuttle diplomacy between Prime Minister Vorster and President Nyerere in 1976, although I may have subsequently been briefed in this regard by our authorities’.Footnote141 As for the ANC, Mac Maharaj, who had been a leader on its negotiating team, admitted that some ANC officials may have known him, but from his perspective, ‘We’d never heard of him. And in the discussions that was taking place, was the overtures of negotiations, his name never cropped up’.Footnote142 And when he was questioned in 2018, Buthelezi recalled that he had met Okumu at a Prayer Breakfast, but he did not convey there was much of a connection outside of that forum.Footnote143 Once Okumu was elevated by his position as the only African on the Kissinger–Carrington team, these weak ties proved enough. He made himself available, as he often had, to front others’ agendas. In their most desperate moment, South Africans who needed to connect with each other activated the potential of Washington Okumu and made him the emissary to each other.

Okumu’s intervention as a mediator also had nothing to do with his years of positioning. Okumu’s personal story may be most instructive to our understanding of South Africa’s transition for inserting contingency into the process. He was not the architect of the deal, which was not about federalism or family. Rather, it was about a topic that had not been evident in these Christians’ earlier conversations and had only recently appeared on constitutional agendas: the status of the Zulu King. On the afternoon of 19 April, the parties announced the breakthrough at a press conference where they signed the memorandum of agreement. The substantive provisions were that the IFP would enter the election, that all parties would reject violence and that the parties would ‘recognise and protect the institution, status, and role of the constitutional provision of the King of the Zulus and the Kingdom of KwaZulu’. Amendments to both the provincial constitution of KwaZulu/Natal and the interim constitution would reflect this. Finally, ‘any outstanding issues in respect of the King of the Zulus and the 1993 Constitution’ would be subject to further international mediation.Footnote144

The statement included these words: ‘The parties would, in particular, like to extend their warm thanks to Prof. W.A.J. Okumu of Kenya who played an important and helpful role in this process’.Footnote145

Ostensibly, King Zwelithini's status as constitutional monarch resolved the IFP’s reservations about the new dispensation, but its decision to join the election also took place at the same time as the secret formation of the Ingonyama Trust.Footnote146 The establishment of the Trust allowed the deep apartheid state to empower a homeland leader at the expense of the ANC-led government. What this deal had to do with the negotiations for the IFP to enter the election was a matter of conjecture until Hilary Lynd’s dedicated research unpacking their intertwined histories.Footnote147 The IFP has disputed that its entry into the elections had anything to do with the formation of the Trust,Footnote148 but the same actors, including Okumu, featured in both efforts, which suggests cross-fertilisation.

The IFP’s reservations were assuaged further because the agreement promised the possibility of more international mediation after the election. The terms for that mediation – the constitutional status of the Zulu king – were much narrower than those at the start of the Kissinger–Carrington effort. Still, the prospect was promising for Okumu, who formed a consulting firm, ‘WAJO Associates, International Consultants on Peace and Development’, with personnel from Cassidy’s AE on staff.Footnote149 His memoir recounts that he attempted to raise mediation with Mandela at a Presidential Forum in July 1994, but the president did not give him time for a conversation.Footnote150 Several realignments shifted the ANC away from its commitment to further international mediation. First, the peace held. Also, the king fell out with Buthelezi and gave his support to the ANC.Footnote151 From their perspective, international mediation would have been tantamount to an effort to mitigate their ascendance. In April 1995, Mbeki informed Buthelezi that the ANC considered the agreement nullified.Footnote152 In a democratic South Africa, Okumu’s specialisation as an African Christian mediator was moot, and he never reprised the role.

Parliament adopted the final constitution in 1996. The structure was no more federal than the interim constitution had been. Its preamble proclaimed ‘God bless South Africa’, but left out a phrase in the interim constitution, ‘in humble submission to Almighty God’. As in the interim constitution, the Bill of Rights protected against discrimination based on gender and sexual orientation.

Okumu reemerged as a peacemaker.Footnote153 He joined his NPI colleagues in an initiative called Relationships Foundation International, which undertook mediation of conflicts in Rwanda and Sudan. Okumu’s network had success here in the early 2000s, when the American Fellowship leader Coe brought Presidents Kabila of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kagame of Rwanda together,Footnote154 but there is little record of Okumu’s specific contribution. He also appeared in negotiations around Sierra Leone and Uganda with the organisation International Alert.Footnote155 His presence there prompted this comment from the Commonwealth Secretariat diplomat Moses Anufu: ‘Oh, that man. I have worked with this character over the Sierra Leone crisis, when he was a consultant to International Alert. I have my reservations about him’.Footnote156 In Kenya, he again ran for parliament, but never won an election.Footnote157 He retreated from politics and community life years before he died in 2016. When I met him, months before his death, he was isolated from his neighbours and poor.

In his memoir, the US ambassador to South Africa in 1994, Princeton Lyman reflected on Okumu’s mysterious appearance: ‘It is still not clear who invited Okumu to the mediation – perhaps the OAU, perhaps Inkatha. In the end, no one cared’.Footnote158 Lyman’s throwaway line encapsulates the widely held sense of inevitability around the 1994 elections. Mandela’s ascension to the presidency has been taken as natural, requiring little explanation. Did journalists leave Washington Okumu aside because he actually was insignificant or because the story of conservative Christian mediators making peace was inconvenient? Probably a bit of both. But what about historians? We agree that we should not think in teleological grooves, and historians of South Africa have stepped back from the idea of struggle as the engine of history.Footnote159 But this assertion could be a most inconvenient revision of struggle narratives: The efforts of an opportunistic front man for white Christian conservatives were essential to saving South Africa’s first democratic elections. In part because of him, they were broadly participatory, peaceful and accepted as valid.

This improbable revision of the history of April 1994 admits that Okumu was powered by luck. Just a few days before, it was not likely that the years spent working towards mediation would come to anything. Historians know that random developments matter, but when we return to the past, we hope to do more than discover the power of accident. True, chance intervened, but contingency favours a prepared assemblage. In reality, the line between over-determined and contingent can be very fine, even in a month as consequential as April 1994. One great consistency, one linear force in this history, is Okumu’s character. His political promiscuity, ambition and willingness to compromise, to play a role that was often at odds with the transition he assisted: these may not be appealing traits, but they may have made the difference in April 1994.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nancy J. Jacobs

Nancy Jacobs is a professor of history at Brown University. She specialises in South Africa, colonial Africa, the environment, knowledge and biography. Her books are: Environment, Power and Injustice: A South African History (Cambridge University, 2003); African History through Sources, volume 1: Colonial Contexts and Everyday Experiences, c. 1850–1946 (Cambridge University, 2014); Birders of Africa: History of a Network (Yale University, 2016; University of Cape Town, 2018). Her current book project, a work of animal history, is The Global Grey Parrot.

Notes

1 This article is the final instalment in a series dedicated to the proposition that Okumu’s history is worth examining. On Okumu’s American backers’ broader influences, see Jacobs, ‘American Evangelicals and African Politics: The Archives of the Fellowship Foundation’, History in Africa, 45 (2018), 473–482. On the methodological and ethical challenges of writing his life history, see N. Jacobs, ‘The Awkward Biography of the Young Washington Okumu: CIA Asset(?) and the Prayer Breakfast’s Man in Africa’, African Studies, 78 (2019), 225–245. On general intellectual and political dilemmas of biographical research, see N. Jacobs and A. Bank, ‘Biography in Post-Apartheid South Africa: A Call for Awkwardness’, African Studies, 78 (2019), 165–182.

2 An AP video now archived on YouTube conveys the energy in the room but does not capture Okumu’s entrance. Associated Press, ‘South Africa – Mediators Meet Rival Black Leaders’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbO-XZTl0pI&t=19s, accessed 13 May 2019.

3 M. Cassidy, A Witness For Ever: The Dawning of Democracy in South Africa (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1995), 164–165.

4 Associated Press, ‘South Africa – Press Conference after Agreement’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ve6o8mk3ehI&feature=youtu.be, accessed 13 May 2019.

5 M. Robertson, R. Hartley, and E. Brulbring, ‘How the Chief Was Turned’, Sunday Times 1994; R. Kraybill, ‘Bringing in Buthelezi: How the IFP Was Drawn into the Election’, Track Two, May 1994. The best early journalistic analysis: Gavin Evans, ‘Mr. Okumu, God and the Strange Case of the King’s Land’, Leadership SA, 13 (1994), 96–102.

6 In writing this history, I have benefitted especially from Waldmeir, Anatomy of a Miracle: The End of Apartheid and the Birth of the New South Africa (New Brunswick: Rutgers University, 1998); D. Atkinson, ‘Brokering a Miracle?: The Multiparty Negotiating Forum’, in S. Friedman and D. Atkinson, eds, The Small Miracle: South Africa’s Negotiated Settlement (Johannesburg: Ravan, 1994), 13–43; R. Humphries, T. Rapoo, and S. Friedman, ‘The Shape of the Country: Negotiating Regional Government’, in The Small Miracle, 148–181; R. Spitz and M. Chaskalson, The Politics of Transition: The Hidden History of South Africa’s Negotiated Settlement (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2001); C. Landsberg, The Quiet Diplomacy of Liberation: International Politics and South Africa’s Transition (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2004).

7 I had been teaching on the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum using a Reacting to the Past exercise: J.C. Eby and F. Morton, The Collapse of Apartheid and the Dawn of Democracy in South Africa, 1993 (2017). I arranged to interview him in Kenya in June 2016. My assistant for the interviews was Aidea Downie, then an undergraduate at my university. Okumu died in November of that year.

8 For a deeper consideration of Okumu’s experience of his own life, see Jacobs, ‘The Awkward Biography of the Young Washington Okumu’.

9 To examine the partisans of compromise is not the same as crediting them for South Africa’s transition, as in R. Harvey, The Fall of Apartheid: The Inside Story from Smuts to Mbeki (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001).

10 This section summarises Jacobs, ‘The Awkward Biography of the Young Washington Okumu’.

11 He told me this. I hold the following as corroboration for this claim: during the summer of 1959, before his admission, he attended the International Student Relations Seminar (ISRS) at Harvard, which has been described as a CIA recruitment wing: K. Paget, Patriotic Betrayal (New Haven: Yale University, 2015), 133–136. He named as his contact Howard Imbrey, whose obituary confirmed he was a CIA officer: Washington Post, 12 December 2002.

12 Washington Okumu personal papers, Bondo, Kenya (hereafter OP) Okumu, Curriculum Vitae, c. 1993.

13 OP Okumu, ‘Obama and the Problem of Screwtape in World Politics’, 152–156. The only independent confirmation of Okumu’s arrest is a cable from the embassy in Nairobi to the Department of State National Archives, College Park Maryland, Record Group 59, box 2256, folder POL 7 1/1/68, which qualifies as further evidence of his relation with Americans. Tom Houston indicated that the story was more complex than Okumu disclosed. T. Houston, personal communication to N. Jacobs, 3 May 2018.

14 Their website: ‘The Fellowship Foundation: Also Known as the International Foundation’, http://thefellowshipfoundation.org/, accessed 20 May 2019. Scholarly and popular considerations of their political role: D. Lindsay, ‘Is the National Prayer Breakfast Surrounded by a Christian Mafia? Religious Publicity and Secrecy within the Corridors of Power’, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 74 (2006), 390–419. J. Sharlet, The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2008). The Fellowship was the subject of the 2019 Netflix documentary The Family.

15 Cassidy had met Doug Coe, the founder of the Fellowship, in 1961 and travelled with him through Africa, from Morocco to South Africa, with many stops, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Kenya. M. Cassidy, The Passing Summer: A South African Pilgrimage in the Politics of Love (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989), 81–83. Over the next two decades Cassidy, Buthelezi and Okumu frequently wrote to Coe.

16 Wheaton College, Illinois, Billy Graham Center, Records of the Fellowship, Collection (hereafter BGC) 459. These letters have been a major resource for reconstructing this history.

17 S. Dubow, ‘New Approaches to High Apartheid and Anti-Apartheid’, South African Historical Journal, 69, (2017), 304–329. Also see R. Nixon, Selling Apartheid (London: Pluto 2016).

18 P. Gifford, The New Crusaders: Christianity and the New Right in Southern Africa (London: Pluto, 1991). Although it has much in common with those he describes, the Fellowship is not mentioned in Gifford’s book.

19 J. Miller, An African Volk: The Apartheid Regime and Its Search for Survival (New York: Oxford University, 2016).

20 BGC 459 Box 254 (South Africa 1977) Folder 27.

21 Okumu interview 11, 14 June 2016.

22 This photograph suggests Okumu’s imposing stature. Van den Bergh was 6 feet, 5 inches (196 cm) tall, and Okumu appears to be nearly that size.

23 When I asked Okumu the purpose of his South African mission, he said, ‘to secure the release of Nelson Mandela’. In an earlier publication, I dismissed this as a post facto attempt to secure nationalist cover: Jacobs, ‘The Awkward Biography of the Young Washington Okumu’, 235. Since then, I have found evidence that the Vorster cabinet discussed the release of Mandela shortly before Okumu’s arrival, on 8 August 1976. H. Giliomee, ‘Mandela and the Last Afrikaner Leaders: A Shift in Power Relations’, New Contree, 72 (2015), 69–96. I now accept that Okumu had Mandela’s release as a bargaining point for Nyerere.

24 I. Smith, Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of Its Independence: The Memoirs of Africa’s Most Controversial Leader (London: John Blake, 2008), 220. On Okumu’s travels to Rhodesia, also see C. Tracey, All for Nothing?: My Life Remembered (Harare: Weaver Press, 2009), 179–180.

25 UNIDO Industrial Development Board, Report by the Executive Director: Technical Assistance to South African National Liberation Movements Recognized by the Organisation of African Unity (Vienna: United Nations, 1985), 4; United Nations Department of Public Information, Yearbook of the United Nations, 1985, vol. 39 (Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 1988), 170.

26 UNIDO Department of Human Resources Management, personal communication to N. Jacobs, 30 April 2018.

27 Okumu, Curriculum Vitae, c. 1993.

28 BGC 459 Box 209 (England 1986–) Folder 1: A.C. to Doug Coe, 29 May 1987.

29 Newick Park Initiative Archives, Courtesy of Jeremy Ive (hereafter NPIA), Ive, ‘Chronology for Newick Park Initiative on South Africa’, 27, 30, 36. NPI retrospectives make a case for its significance: Ive, ‘A History of the Newick Park Initiative (NPI) and Its Contribution to Building Peace in South Africa 1986–1994’, 27–28, http://www.jubilee-centre.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/The-History-of-NPI-in-South-Africa-July-20141.pdf

30 M. Schluter and J. Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa: Christian Principles and Practical Feasibility (Cambridge: Jubilee Centre Publications, 1987), 7.

31 R. Skinner, ‘The Anti-Apartheid Movement: Pressure Group Politics, International Solidarity and Transnational Activism’, in N. Crowson, M. Hilton, and J. McKay, eds, NGOs in Contemporary Britain: Non-State Actors in Society and Politics since 1945 (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 129–146.

32 Dubow, ‘New Approaches to High Apartheid and Anti-Apartheid’, 319.

33 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 5.

34 Ive, ‘Peacebuilding and the Ending of Apartheid’, Jubilee Centre, 13 May 2014, http://www.jubilee-centre.org/peacebuilding-ending-apartheid-jeremy-ive/. See also J. Ive, ‘A History of the Newick Park Initiative (NPI)’, 10.

35 A. Cameron, ‘Towards a Practical Political Theology: A Provisional Typology of Public Faith in a Post-Secular Age’, in A. Maher, ed., Faith and the Political in the Post Secular Age: Explorations in Practical Theology (Bayswater Coventry, 2018), 107.

36 The name ‘Jubilee’, referring to the Old Testament dictate for restitution every seven years, is a signal for a biblical idea of economic justice. In the year of Jubilee, debts were to be forgiven, slaves freed, and land returned to original owners. On Jubilee Centre’s Bible-based reforms to capitalism: I. Abraham, ‘Capital, Culture and Contradictions: Contemporary Christian Economic Ethics’, Pacifica, 22 (2009), 53–74, 65–67.

37 ‘Jeremy Ive Page’, https://www.allofliferedeemed.co.uk/ive.htm. He also cites the influence of the Kuyperians H. Dooyeweerd and C. Van Till.

38 A. du Toit, ‘Puritans in Africa? Afrikaner Calvinism and Kuyperian Neo-Calvinism in Late Nineteenth-Century South Africa’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 27 (1985), 209–240; T. Moodie, The Rise of Afrikanerdom: Power, Apartheid, and the Afrikaner Civil Religion (Berkeley: University of California, 1980).

39 R. Mouw, ‘Calvin’s Legacy for Public Theology’, Political Theology: The Journal of Christian Socialism, 10, 3 (2009), 431–446.

40 ‘Jeremy Ive Page’. The Potchefstroom academic Wicus du Plessis also argued from a Kuyperian base against Verwoerdian apartheid, in favour of something closer to decolonisation: C. Marx, ‘From Trusteeship to Self-Determination: L.J. Du Plessis’ Thinking on Apartheid and His Conflict with H.F. Verwoerd’, Historia, 55 (2010), 50–75.

41 M. Worthen, ‘The Chalcedon Problem: Rousas John Rushdoony and the Origins of Christian Reconstructionism’, Church History, 77, 2 (2008), 399–437. This article frames dominionism as a misreading of Kuyper.

42 H. Adam and K. Moodley, South Africa without Apartheid: Dismantling Racial Domination (Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman, 1986); L. Louw, South Africa: The Solution (Bisho, Ciskei: Amagi Publications, 1986); A. Lijphart, Power-Sharing in South Africa (Berkeley: University of California, 1985).

43 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa. The document included commentary by the Oxford geographer Anthony Lemon.

44 Lijphart, Power-Sharing in South Africa.

45 These were: God as creator, love, father, just, a judge of sinners, and peaceful.

46 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 63.

47 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 9. The US spelling is in the original.

48 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 9.

49 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 61; NPIA Ive, ‘Chronology for Newick Park Initiative on South Africa’.

50 A. Balcomb, ‘From Apartheid to the New Dispensation: Evangelicals and the Democratization of South Africa’, Journal of Religion in Africa, 34 (2004), 5–38.

51 Ive, ‘Chronology for Newick Park Initiative on South Africa’, 21.

52 R. Southall, ‘Consociationalism in South Africa: The Buthelezi Commission and Beyond’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 21 (1983), 77–112; D. Van Wyk, ‘Indaba – the Process of Real Negotiation’, South Africa International, 18 (1987), 99–106.

53 If traditional track-one diplomacy is state-based, track-two diplomacy is unofficial and informal, often facilitated by non-state actors: J. Montville, ‘A Case for Track Two’, in Conflict Resolution: Track Two Diplomacy, eds. John W. McDonald, Jr., and Diane B. Bendahmane (Washington, DC: Foreign Service Institute, US Dept. of State, 1987), 7.

54 Savage counts 153 meetings between the ANC and ‘South Africans’ between 1983 and 1989: M. Savage, ‘Trekking Outward: A Chronology of Meetings between South Africans and the ANC in Exile 1983–2000’, http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/chronology-meetings-between-south-africans-and-anc-exile-1983-2000-michael-savage. Academic studies of South African track-two diplomacy: J. De Maio, Confronting Ethnic Conflict: The Role of Third Parties in Managing Africa’s Civil Wars (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2009); D. Lieberfeld, ‘Getting to the Negotiating Table in South Africa: Domestic and International Dynamics’, Politikon, 27 (2000), 19–36; D. Lieberfeld, ‘Evaluating the Contributions of Track-Two Diplomacy to Conflict Termination in South Africa, 1984–90’, Journal of Peace Research, 39 (2002), 355–372.

55 W. Esterhuyse, Endgame: Secret Talks and the End of Apartheid (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2012).

56 They included: Zola Skweyiya, Tito Mboweni, Max Sisulu, Nathaniel Masemola and Papie Moloto. NPIA, J. Ive, ‘Chronology for Newick Park Initiative on South Africa’. Retrospectives on NPI work as track two and peacebuilding: Ive, ‘A History of the Newick Park Initiative’ and J. Ive, Peacebuilding and the Ending of Apartheid’.

57 Dlamini was on the faculty at the University of Zululand. NPIA, Ive, ‘Chronology’.

58 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 65.

59 F. Cloete, personal communication to N. Jacobs, 6 October 2019; F. Cloete telephone interview 13 October 2019; Cloete’s presentation: F. Cloete, ‘Religious and Cultural Safeguards for Minorities in Public International Law and Comparative Constitutional Law’, Newick Park Initiative: Constitutional Safeguards in Unitary and Federal States, England (1990). Okumu’s critique here echoed one his patron Tom Mboya had made of multi-racialism: Jon Soske, ‘The Impossible Concept: Settler Liberalism, Pan-Africanism, and the Language of Non-Racialism’, African Historical Review, 47 (2015),16–18.

60 Schluter and Ive, Alternative Constitutional Settlements in South Africa, 65. (The US spelling is in the original.)

61 Land Reform and Agricultural Development: Papers Presented at a Conference of the Newick Park Initiative Held in the United Kingdom in October 1990 (Cambridge: Newick Park Initiative, 1990).

62 Okumu, ‘Preface', Land Reform and Agricultural Development.

63 Ive, ‘Peacebuilding and the Ending of Apartheid’, 3.

64 A publication from an NPI presentation: A. Van Wyk, ‘Safeguards for the Family: A South African Perspective’, Stellenbosch Law Review, 1 (1990), 186–197.

65 Ive, ‘A History of the Newick Park Initiative (NPI)’, 34, 49.

66 H. Stephens, Family Matters: James Dobson and the Focus on the Family’s Crusade for the Christian Home (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2019), 7.

67 S.M. Klausen, ‘“Reclaiming the White Daughter’s Purity”: Afrikaner Nationalism, Racialized Sexuality, and the 1975 Abortion and Sterilization Act in Apartheid South Africa’, Journal of Women’s History, 22 (2010), 39–63.

68 D. Driver, ‘The ANC Constitutional Guidelines in Process’: A Feminist Reading’, in S. Bazilli, ed., Putting Women on the Agenda (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1991), 85.

69 Cassidy, Passing Summer, 460–461.

70 ‘More Church-Linked Plans for Mediating S. African Negotiations’, SouthScan 17 November 1989.

71 Cassidy, Passing Summer, 461–464.