ABSTRACT

The history of boxing in Cape Town, South Africa, remains a minor focus of study amongst sport historians, compared to rugby, soccer or cricket. This article endeavours to address this situation by presenting a boxing narrative from 1932 to 1935. A literature review on boxing history in the British and American world is used to introduce the reader to this narrative. It shows how organised boxing in Cape Town’s black communities was historically rooted in all classes of people. It also reveals how the current body of academic research on black boxing is gaining momentum but is still in its infancy in South Africa. There are, however, many popular narratives from which researchers can draw. A methodological account is presented that outlines the reconstructionist method of historical research. Next, the article proceeds with a history of organised boxing, and it is shown how this sport was driven by class considerations from the nineteenth century onwards. The article concludes with the notion that professional boxing brought relief for promoters, boxers and gamblers during the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s. This ran parallel with the ‘upliftment’ project of the club movement with its theme of ‘keep the boys off the street’.

KEYWORDS:

Boxing History Matters

Over the past 270 years, prizefighting and boxing have exerted a considerable hold on the popular imagination.Footnote1 However, boxing has, for the most part, been a sport neglected by historians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.Footnote2 A bird’s-eye view of written South African boxing history shows that the subject has not reached a stage where it can boast a broad black database comparable to, for example, that found in the work by the American Edward Henderson, The Negro in Sports.Footnote3 The field is still plagued by the ‘reproduction of a largely unrecognised overwhelming whiteness’.Footnote4 This article is thus a contribution towards establishing a broad black South African database. A period of review (1932–1935) that coincided with the worldwide economic depression was selected. A justification for this study is, therefore, to create space for a historical narrative about the nature of professional boxing during the economic depression of the 1930s.

To date, the standard reference work on South African boxing history remains the seminal work of Chris Greyvenstein, The Fighters.Footnote5 It is a publication with a broad scope of study (1881–1981) and is indispensable for any project that undertakes to write on South African boxing history. Another useful publication is the 525-page softcover book by Gavin Evans, Dancing Shoes Is Dead. Evans, a former African National Congress operative during the apartheid era, presents his life story as one entwined with boxing and politics.Footnote6

The only known government project on South African boxing history – the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC)’s report of 1982 – is, however, silent on the social and political conditions of black boxing history.Footnote7 This report highlighted major boxing events without reference to local social and political conditions. It also neglected other important areas such as the names of local boxers, promoters, managers and venues. Although not without merit for exploring black boxing history in South Africa – Cape Town in particular – this publication fits in with a white, exclusionary narrative of the past. New narratives that challenge the colonial ways of accounting for the past are needed. For the purpose of this study, colonisation refers to British imperialism in southern Africa:

British imperialism reached its height at the end of the 19th century, an empire that comprised almost a quarter of the world, with the British crown represented on every continent. As a result, British religion, language, culture, habits and customs also came to be established in [s]outhern Africa. One of the customs to be transplanted here permanently was the British form of sports and games.Footnote8

History of organised boxing

Prior to 1838, ‘boxing’ in England was practised in a different format to what we know today. It was a no-holds-barred contest that would usually take place over three bouts: one of swordplay with a choice of swords, daggers or shields; one of bare-knuckle boxing; and one fought with quarterstaff or cudgels. Bare-knuckle fighting permitted eye-gouging, hair-pulling, spitting, head-butting, shin-kicking, stomping and kicking opponents who were on the ground, as well as using wrestling throws and grappling whilst on the ground. The men who took part in these contests were called prizefighters, because they fought for a prize, which could be money, trophies, free drinks or any other prize.Footnote10

London Prize Ring Rules

The London Prize Ring Rules (bare-fist fighting until the last fighter standing) can be traced back to 1838 and were revised in 1853.Footnote11 These rules, 29 in all, stipulated that there should be a square ring of 7.3 m on a side with a centre line where the bout must start. The ring had to be cordoned off with a double row of ropes. Boxers could grip their opponents above the waist, and wear boots with spikes (within reason), and a round was completed when a fighter was knocked or thrown down. Afterwards, he was given 30 seconds to stand up on his own and 8 seconds to move to the centre line. There was no set number of rounds and fights could last for numerous rounds or could be shortened, depending on how long the boxer wanted to use the 30-second recovery period. No biting, head-butting or punching below the waist was allowed.Footnote12

Queensberry Rules

The period under review was when the Queensberry Rules had become the accepted code governing boxing in South Africa. These were rules (named after the ninth Marquis of Queensberry) introduced in Britain in 1866 and designed for the purpose of fighting with gloves instead of bare knuckles. Being drawn up by John Graham Chambers, a pioneer of organised athletics in Wales in 1860, founder member of the Amateur Athletic Club in 1866 and present at the formation of the Amateur Athletic Association in 1880,Footnote13 it can safely be argued that these rules came from the aristocratic classes trying ‘to keep unscrupulous elements in check’.Footnote14 Understandably, then, the Queensberry Rules appeared at a time when the emerging working class in industrialising Europe, as Matthew Arnold describes,

… [was] raw and half-developed, has long lain half-hidden amidst its poverty and squalor, and is now issuing from its hiding-place to assert an Englishman’s heaven-born privilege of doing as he likes, and is beginning to perplex us by marching where it likes, meeting where it likes, bawling what it likes, breaking what it likes … Footnote15

Boxing history in the Cape Colony and Cape Province, South Africa

Past historians have recorded how knife fighting in the seventeenth-century Cape Colony, although illegal, was a popular pastime amongst visiting sailors, particularly from Batavia. In Batavia, these knife fights had fixed rules. In England, knife fights vied with boxing matches for popularity. At the Cape, however, the authorities condemned but could not control knife fighting and offenders were sent to the gallows.Footnote18 Foremost in the minds of the city lawmakers was the notion of ‘public decency’ that did not tolerate street games such as cards, pitch and toss, and ‘milling’ (boxing). In 1857, the Cape Argus reported on the following incidents:

[A] coloured gentleman, named Henry Clarke, was sentenced to eight strokes with the rattan for amusing himself with cards in Dorp Street … [in another case] … a little boy named Franz Ceaser was charged with amusing himself on the Sabbath with playing pitch and toss in Bree Street. Another boy, named Abdol [a coloured], was likewise placed in the dock for the same offence. The [judge] deplored their vicious habits and sentenced them to receive eight cuts of the rattan … Two aspirants … Japie and Mahmoud were charged with engaging in a milling match in Harrington Street … and were fined 5 shillings each.Footnote19

Boxing was popularised in the Cape Colony after the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in 1867 and gold in the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) in 1886. This led to rapid urbanisation, with gambling and mass spectator sport as key features. The sport took off under the London Prize Ring Rules.Footnote22 A boxing club was established in the cosmopolitan town of Kimberley on 24 April 1877 ‘for the manly act of self-defence’.Footnote23 Boxing was not regarded as part of middle-class society, and the Diamond Fields newspaper expressed the idea that this club be transformed into a gymnastic and athletic society.Footnote24 According to a settler of the time, Louis Cohen, Kimberley was a town where ‘Hindoos, Hottentots, Negroes from Mozambique, Cape Boys from St. Helena, Half Breeds from Anywhere, Malays, Jews, Germans, Africanders, Americans, Europeans jostled and pushed one another’.Footnote25

The following year, mining magnate Barney Barnato opened an amateur boxing school there. Prizefighting became an immensely popular sport in the black community in Kimberley. Joe Coverwell, a canteen owner in the Malay Camp, was an influential and respected man in his community, despite being a violent bully who beat his wife. This Coverwell had become a symbol of black success and achievement and when he defeated an English soldier, Denton, in a 70-round boxing match in the Free State, ‘there was no end of triumphal crowning and jeering on the part of the Malays and other dusky gentry’.Footnote26 Coverwell became a hero to poor black communities in Kimberley who had ‘become docile and mute’.Footnote27 By 1882, the Queensberry Rules had become the accepted practice in Cape Town. In this year, according to a later report, the settler boxer James Couper defeated Coverwell in a boxing match for a South African colonial championship title in Kimberley.Footnote28

The pre-World War I black intelligentsia in Cape Town’s colonised communities turned to African American society for political inspiration but clung to British cultural symbols and values. One such Cape Town-based intellectual, Harold Cressy, is quoted as saying ‘Nobody makes a more in-depth study about the negro, than the negro himself’.Footnote29 Given the prevailing racist attitudes against colonised communities in Cape Town, they were excluded from early sport clubs and federations and had to find their own way. Thus, when the Western Province Rugby Football Union met with representatives of first-class schools in Cape Town in 1898 with the intention of establishing a junior competition, it was restricted to clubs that consisted entirely of ‘European players’.Footnote30 This was no different in boxing.

Coloured and African sportspersons in Cape Town, including boxers, thus organised their own clubs in increasingly segregated and mainly lower socioeconomic living areas. The year before South Africa entered its first Olympic boxing team in 1920, a School of Physical Culture was opened by a Rhodesian, J.J. Meyers, in Cape Town. Meyers claimed to be the ‘coloured bantamweight South African boxing champion’.Footnote31 Professional boxing tournaments were staged in theatres in Cape Town, but especially in the National Theatre on William Street.Footnote32 This street was located in the hub of the economically poor area, District Six, which was described as ‘an old run-down area … to the official eye it was a slum … [but] teemed with life, providing the observer images of variety and colour and the inmates with sensations of human warmth and community … ’.Footnote33 The Salt River Institute was also a popular venue.Footnote34 The Sun also reported on a number of gymnasiums that were training facilities for boxers and included the ‘non-European pavilion in Woodstock’.Footnote35 Other venues included Cape Town City Hall, Claremont Town Hall, the National Theatre, St Phillips School and Forrester’s Hall.

In October 1932, the coloured Western Province middleweight champion, Willie Smith, was scheduled for a professional bout in the Durban Town Hall under Queensberry Rules.Footnote36 These rules, with their complicated points system, were also used in December of that year when Cape Town boxer Arthur Cupido fought the Durban-based fighter Bud Gengen in a 12-round bout which Cupido won on points.Footnote37 Previously, such bouts would last until only one fighter was left standing. The Queensberry Rules did not always bring about the desired ‘respectability’, as can be seen in the bout between Cupido and Kid Motte. The latter won on points, much to the dissatisfaction of the spectators, leading to police intervention.Footnote38

Amateur athletic clubs that promoted boxing also used the Queensberry Rules. An example of such a club is the Cape Town-based Suburban Harriers Amateur Athletics and Cycling Club that organised regular boxing tournaments, mostly outside the city centre in the suburb of Claremont, since 1904. This club was prominent in Cape Town amateur boxing communities designated as coloured.Footnote39 In March 1933, the club organised a 17-bill tournament where amateur football players and athletes such as Barney West also participated.Footnote40

By 1934, boxing bouts in South Africa had become a national enterprise under the Queensberry Rules. In Natal, V. Doorasamy Maistry was promoting professional bouts under these rules and was sanctioned by the Natal Board of Control.Footnote41 Professional boxers and promoters from Cape Town, Transvaal and the Eastern Province were also operating under a board of control, presumably under the same rules.Footnote42 These rules aimed at giving boxing a badge of respectability, structure and order. Hence, journalists were apt to report on ‘good, clean and tactical fights’.Footnote43 During the period under review, boxing in Cape Town had reached a level of statistical sophistication and The Sun carried information that is of value to boxing statisticians.Footnote44 Professional boxing promoters also preferred grand venues and started using the Cape Town City Hall instead of the more local suburban town and school halls mentioned earlier.Footnote45 On the other hand, amateur clubs such as the Protea Weightlifting and Wrestling Club continued to host wrestling and boxing tournaments in the St Phillip’s School room.Footnote46

Professional boxing promoters were also, on occasion, present at amateur tournaments, scouting for new recruits. One example is that of John de Vries, the promoter for Mannie Hommel, Jimmy Dixon, George German and others. Hommel, a saddler from Mafekeng, was regarded as the South African coloured heavyweight champion in 1919.Footnote47 De Vries was also the secretary of the City and Suburban Rugby Football Union, an amateur sport federation, with a self-declared distinct coloured and Christian culture.Footnote48 By the 1930s, professional promoters were operating on a national scale and V. Doorasamy Maistry was organising fights in Cape Town and Durban.Footnote49 As was the case in Nigeria, these various professional promoters did more than simply sell tickets. They shaped the ideals of boxers, bodies and manhood. In other words, they sold a form of masculinity and modernity to African audiences.Footnote50

Very few coloured boxers made a smooth transition from their active participation as fighters to enterprising individuals beyond the boxing ring. Jim Dixon, for example, turned to alcohol, and Andrew Jephta became a blind pauper on the streets of Cape Town. Jephta was supported by the African People’s Organisation who marketed his published life story as a fund-raising effort to provide some relief to his precarious state.Footnote51 One exception was Arthur Cupido, who became the successful trainer of Martin Ehrenreich and Willie Forgus.Footnote52 Another success story was the previously mentioned William Smith who registered the ‘Willie Smith’s School of Physical Culture’ under the 1936 Companies Act in Transvaal.Footnote53

Methodological considerations

One objective of this article was to position this boxing narrative in the field of physical culture studies in South Africa. The term ‘physical culture’ is defined by Janice Todd, an eminent scholar in the field, as follows: ‘Various activities people have employed over the centuries to strengthen their bodies, enhance their physiques, increase their endurance, enhance their health, fight against aging and become better athletes’.Footnote54 This study investigated the branch of physical culture known as pugilism or boxing. The research in this study revealed how, during the period under review, amateur boxing was as popular as other sport codes such as athletics, rugby, wrestling and gymnastics at local community levels.Footnote55

This article homes in on a newspaper, The Sun, which targeted a community in Cape Town, South Africa, defined by segregationist, apartheid and post-apartheid governments as ‘coloured’. The authors reject the concept of ‘race’ as a signifier for the human condition on four accounts. Firstly, the idea of people being of ‘mixed’ race or creole (read: ‘coloured’) as a result of biological procreation has lost scientific validity. Secondly, the idea of coloured or creole people being an independent social grouping has been disproven by accounts that point to the variety of historical backgrounds of these people, common to all nationalities.Footnote56 Thirdly, a significant number of people who were labelled ‘coloured’, including opinion makers, rejected this term. Lastly, the ethnic label ‘coloured’ was used by the apartheid government to oppress, exploit and discriminate against people. However, this racial label was a social reality. Also, international boxing history is a racialised narrative and promoters did not shy away from ‘othering’ groups by using labels such as ‘black’, ‘Jew’ or ‘Irish’ in boxing reports.Footnote57 Therefore, racial terms are used throughout this article – but with caution. Henceforth, the term ‘black’ will be used as a generic reference to all ‘non-white’ people, while the terms ‘coloured’ and ‘Indian’ will refer to those people classified as such by segregationist, apartheid and post-apartheid governments.

Contextual background to The Sun newspaper

This study collected data from The Sun newspaper for the period 1932 to 1935. This newspaper published records of boxing matches, venues, dates, and names of fighters, promoters and managers, making it a valuable instrument for the recording and analysis of boxing history. Records such as these allow historians to present information on prevailing political and social values for the period under review.Footnote58 More importantly, The Sun was a catalyst for professional boxers, mainly from Cape Town, but also from elsewhere in South Africa, to issue challenges to one another.Footnote59 Given the small pool of professional boxers in Cape Town, this newspaper proved to be a valuable platform for issuing challenges, including for championship titles.Footnote60 Hence, Bennie Herbert challenged Willie Smith, Arvie Williams or ‘anyone who was in the coloured light or welter-weight division … [and] George Frenchmen wanted to fight Renico Simons or Benny Singh or Johnnie Solomon for the coloured featherweight championship of the Cape of Good Hope’.Footnote61 Such challenges were issued and responded to from the far-flung corners of South Africa such as Durban, Kimberley and the Eastern Cape.Footnote62 The Sun also reached a Johannesburg audience, where manager A.S.W. Nkomo accepted a challenge on behalf of his boxer, Joe Gain (a former Transvaal amateur champion), from Kid Matthews (Jr) for a bantamweight bout. The challenge was put forward ‘to any coloured in the country’.Footnote63 Boxing reports were also received from Salisbury (present-day Harare).Footnote64

Historical researchers should be aware that the reliability of newspaper material varies considerably due to human error in the process of providing, receiving or printing the information to be used. This is so because journalists bring with them their own knowledge and experience in the observations, descriptions and opinions they write about.Footnote65 This may be overcome by sources gaining official status through public archiving (in this case The Sun, a newspaper). The full run of this newspaper (1932–1956) is located in a public archive, The National Library of South Africa: Cape Town Division, where microfilm copies allow researchers to clearly see the data. Because The Sun is in public archives, it holds special meaning for those historians who believe that such locations are ‘beacons of light’.Footnote66 An analysis of this newspaper is, however, necessary in order to work out and steer the methodological procedure of this study.

The Sun was a weekly newspaper directed at a particular community (designated coloured) and was issued predominantly in English, with some contributions in Afrikaans. It was an eight-page publication: six pages of politics, general interest news and entertainment, and the last two pages dedicated to sport. The publication resembled the APO newspaper that was in existence from 1909 to 1922: a propaganda organ of the African Political (later People’s) Organisation. The APO’s target audience was the franchised coloured community, and its objective was to ‘uplift the whole coloured community to a civilised status’.Footnote67 This ‘upliftment’ project was also driven by the Boys’ Club Movement, not only in Cape Town but also in other parts of the British Empire, and included boxing, which was meant to ‘keep these boys off the streets, by civilising the roughest or lowest of boys … . [and] becoming an escape route from poverty’.Footnote68 Thus, these clubs emphasised respectability, structure and order. The Sun did not deviate from this project. Hence, all boxing reports in this newspaper appeared in English, ‘the language of preference for class-conscious coloureds’.Footnote69 These reports were articles that present researchers with the names of boxers, venues where bouts took place, managers and promoters.

A contextual and background sketch of The Sun is necessary to understand the nature of reporting on boxing during the period under review. The Sun was less radical than other pre- and early post-World War II Cape Town community-based weekly newspapers. The Cape Standard (1936–1947), for example, gave some support to the Communist Party while the Torch (1946–1963) reflected a Trotskyist influence.Footnote70 According to Les Switzer and Donna Switzer:

The Sun, a predominately [sic] English weekly newspaper with contributions in Afrikaans, was founded by a journalist A.S. Hayes and printer C. Stewart in 1932. The first volume was published in Cape Town as a conservative opined coloured newspaper on 26 August 1932 which it remained until it ceased publication on 28 September 1956. Most of its space was devoted to general interest, news, sports, entertainment and society news. It came under the control of a white businessman and printer Samuel Griffiths from 1936. The Sun supported the coloured African People’s Organisation (APO) and the white United Party who accepted segregationist policies of succeeding South African governments. The United Party eventually bought The Sun Printing and Publishing Co (Pty) Ltd, nine months prior to the 1948 elections. In 1950 Griffiths bought the newspaper back again and became director. H.R. Lawley, who was a white journalist and co-director of the company was the editor in the 1950s and the main columnist was C.I.R Fortein. The United Party continued to heavily subsidize the newspaper.Footnote71

The Sun also showed how professionalism facilitated a shift towards international boxing in Cape Town. Thus in 1933, Clyde Chastain, an American cruiserweight, was scheduled to fight Jack O’Mally, a former Australian heavyweight champion, in Cape Town.Footnote75 Two years later, Fred Wells, an English professional fighter, fought the Capetonian boxer George Frenchmen in the Cape Town City Hall.Footnote76 The Sun also reported on Joe Louis’ victory over Max Baer.Footnote77

The newspaper also provided a platform where South African black professional fighters could issue challenges.Footnote78 These challenges were planned and well thought out, not left to whimsical decisions, and often were issued through managers.Footnote79 During the period under review, the newspaper also acted as a space for conflict resolution, for example when the Cape Town boxer Willie Forgus requested The Sun to issue a statement to the effect that he had not been knocked out by Sonny Thomas.Footnote80 Another dispute arose, and was addressed in The Sun, when a reader questioned Willie Smith’s credentials as the ‘South African coloured middle weight champion’.Footnote81

Although the target audience of The Sun, as mentioned earlier, was the social middle classes in a community defined as coloured, the nature of boxing in Cape Town was such that other communities could not be ignored in the newspaper. On at least one occasion, a boxing bout between white boxers was advertised.Footnote82 Occasional references were also made to institutions generally out of bounds for black people, such as the reorganised Cape Province National Sporting Club that was already in existence by 1897 and hosted a professional tournament that included white boxers such as Jim Pentz and Laurie Karstadt.Footnote83 Similarly, the coloured boxing fraternity crossed paths with South African Indian boxing promoters such as M.M. Mohamed and J.B. Panday.Footnote84 These promoters often crossed the colour line, and in 1934 they promoted a bout between the Guyanan-born Kid Mottee Singh and Cape coloured lightweight Arthur Cupido.Footnote85 Mohammed and Pandy, however, promoted their tournaments mainly in Durban centres, at Victoria Picture Palace and Durban Town Hall.Footnote86 The Sun also carried a special section, ‘The Indian World’, for Indian South Africans. Therefore, The Sun allows researchers, in small ways, to move boxing history outside the preconceived national identities of the past.

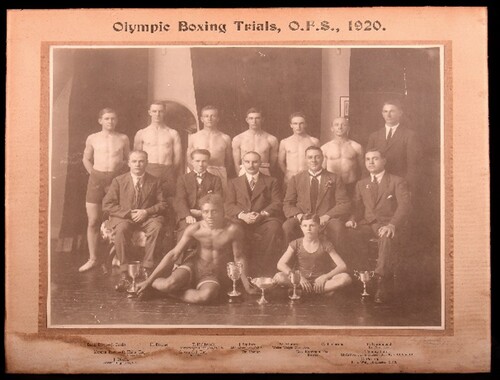

There has been some interest of late in the life and times of boxers classified as coloured.Footnote87 The Sun is a useful tool for analysis in this regard because it helps with uncovering details on unknown boxers, some of whom, such as Sonny Thomas and Willie Smith, were regarded as outstanding in their day.Footnote88 Another case in point is that of Jimmy Dixon, a middleweight boxer who fought in the heavyweight division.Footnote89 Dixon also participated in the Orange Free State Olympic trials (see ). The Sun mentioned that Dixon died in 1934, the same year as his promoter, John de Vries.Footnote90 The names of promoters currently not found in mainstream research can also be unearthed in The Sun. These include Arthur Ludski and V. Doorasamy Maistry.Footnote91 These names and venues are important in order to recover an aspect of a lost history of Cape Town, especially at a time such as the present when Cape Town has a virtual absence of professional boxing activity.

During the height of the worldwide economic recession in the 1930s, The Sun could still report on ‘fans enjoying themselves and getting their monies’ worth’.Footnote92 Consequently, promoters such as Ludski received wide publicity in a newspaper, which possibly contributed to a successful business career during a time of worldwide economic depression when social structures were collapsing.

Limitations of The Sun newspaper

Sport reports in The Sun were written by freelance reporters (called stringers) and journalists, possibly without formal training. Hence, there are regular data inconsistencies. These inconsistencies include, amongst others, inconsistent spelling of names and venues.Footnote93 A further limitation researchers experience when using The Sun is the absence of a similar newspaper during the period under review. These limitations, however, are not so serious as to stand in the way of creating historical boxing narratives. This is so because we argue that newspapers are at the intersection of lies and social life. However, the historian Premesh Lalu has argued that this is central to the work of history. Lalu claims that ‘regimes of truth are lodged in the articulation of what are ultimately considered lies … [that] offer little hope of settling the outstanding questions about the colonial past’.Footnote94

Respectability, structure and order in boxing

During the eighteenth century, prizefighting in England drew large crowds that were a ‘complete mixture of classes’.Footnote95 Structured black boxing under the direction of promoters in the Anglo-Saxon world is generally traced back to Bill Richmond, an African American, born in Staten Island and taken to England by the Duke of Northumberland in 1777. By then, public bouts were accepted practices in England, and one internet source states:

Often in those days boxers would bring along their wives or sweethearts to join in the battle! Sort of like a tag team. The ladies would use hair pulling, biting, eye gouging, spitting, head butting and stomping on the other couple … James Figg even promoted bouts solely between women … The London Journal reported in 1722 that each woman was to strike each other in the face while holding a half crown coin in each fist. The first to drop a coin would be the loser. The blood spurted from the women’s dirt-stained faces, the noses split and the eyes swelled shut. The English gentlemen in the crowd loved it and screamed for more.Footnote96

During the nineteenth century, a number of black boxers fought in internationally sanctioned bouts, the earliest recognisable black boxer being Tom Molyneux in 1810. However, there remains uncertainty about Molyneux’s true identity since he took his surname from the plantation owner, as was common practice for children born into slavery.Footnote98 Oral tradition has it that Molyneux’s father and grandfather were notable boxers among plantation slaves.Footnote99 The possibility that Molyneux was trained by the later American president George Washington has also been suggested.Footnote100 Molyneux’s most memorable bout was in 1810 against Tom Cribb, an English settler boxing champion, in a 39-round bare-knuckle bout under the London Prize Ring Rules. According to a documentary by Richard Fitzpatrick, it was extraordinarily bloody and the two men battered each other so badly that spectators were unable to tell them apart. The bout ended with Molyneux suffering a dubious defeat. Molyneux moved to Ireland in 1815, where he slipped further and further down the social scale and his body withered from drinking and tuberculosis. He died in 1818, and his last years were spent in Galway where he fought in market squares, alongside competing Sunday attractions such as badger-baiting and cock-fighting.Footnote101

Another nineteenth-century African American fighter who captured the public’s attention was Jim Wharton. On 9 February 1836, he fought a 200-round bout against Tom Britton. The bout lasted 4 hours and 7 minutes and ended in a draw.Footnote102 Edwin Henderson made special reference to the commendable way these boxers and other boxers such as Joe Louis carried themselves. ‘ … [They] were cultured … [and] carried themselves in [a] manner that merits the respect of all who knew them … ’.Footnote103 Henderson was thus one of the earliest sport historians who attempted to present black boxers as more than ‘one-dimensional, subservient and exotic characters’.Footnote104

Conclusion

This study attempted to fill in the gaps in the boxing history of Cape Town’s politically and socially oppressed communities by undertaking a historically contextualised study of the sport as reported in The Sun newspaper from 1932 to 1935. The centring and recognition of communities labelled coloured can inspire ‘ways of thinking about and doing histories of sport that break with essential whiteness’.Footnote105

This article has shown how boxing history, drawn from newspaper accounts, does not unfold as a politically neutral narrative. It is absurd to think that boxing was any different to other sport codes in oppressed communities during a time when society was shaped by segregation and ethnic sectarianism.Footnote106 The South African boxing narrative in these communities also reveals the marginalisation, even absence, of women in traces and accounts of South African boxing history. Future research needs to address this vacuum, if the intention is to create a new South African narrative. The data presented in this article serves as a powerful reminder of a history of exclusion in South Africa, where, for example, oppressed communities had no boxing representation at the Olympic Games, from the time South Africa started participating in boxing at the Games in 1920 until 1960.

The primary information source, The Sun, although riddled with grammatical and even factual inconsistencies, proved that these oppressed communities have a boxing history worthy of telling. What this study has done in the process was to create an alternative boxing history to the dominant mainstream narratives of the past that tried to prove blacks had no agency in South Africa’s sporting past. The pain of historical exclusion found in the boxing history of oppressed communities needs to be shared and felt. This is an acute need because there was no truth and reconciliation process in sport in South Africa.Footnote107 The research undertaken attempted to address these exclusions by revealing names, events and venues not present in the public discourse as yet. During the era of worldwide economic recession, professional boxing in black communities was well structured, making it possible for boxers from different geographical and economic backgrounds to challenge each other at various venues. In the process, boxers, promoters and gamblers, whether legal or not, could find some financial relief from hardship. This happened perhaps in opposition to the amateur boxing code that pursued a moral ‘upliftment’ project, largely driven by the Boys’ Club Movement that aimed to ‘keep the boys off the streets’, through a theme of ‘civilisation’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Francois Johannes Cleophas

Francois Johannes Cleophas is a senior lecturer, with an interest in decolonial sport histories, in the Division of Sport Science at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. He is the editor of two books, the most recent being Physical Culture at the Edges of Empire and Society. Since 2009, he has published more than 50 articles in accredited national and international journals, and 10 book chapters. He is currently working on a monograph about physical culture in South Africa’s marginalised communities in the Western Cape.

Mzi Qacha

Mzingwana (Mzi) Qacha graduated with an honours degree in sport science from Stellenbosch University in 2017. His research project dealt with the boxing history of Cape Town’s marginalised communities during the 1930s. He is currently employed as an Intern Sport Scientist at SEMLI (Sport, Exercise Medicine and Lifestyle Institute) at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Notes

1 J. Welshman, ‘Boxing and the Historians’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 14, 1 (1997), 195–203.

2 A few exceptions do exist. See B. Singh, My Champions Were Dark (London: Pennant Books, 1961); T. Fleming, ‘Now the African Reigns Supreme: The Rise of African Boxing on the Witwatersrand, 1924 – 1959’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28, 1 (2011), 47–62; K. Campbell, To Write as A Boxer: Disability and Resignification in the Text. A South African Boxer in Britain (London: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019).

3 E.B. Henderson, The Negro in Sports (Washington: ASALH, 2014).

4 M. MacLean, ‘Rethinking British Sport History for a Decolonising Present: Confronting Thingification and Redaction’, Sport in History (2022), DOI:10.1080/17460263.2022.2131613.

5 C. Greyvenstein, The Fighters. A Pictorial History of South African Boxing from 1881 (Cape Town: Don Nelson, 1981).

6 G. Evans, Dancing Shoes Is Dead. A Tale of Fighting Men in South Africa (London: Transworld, 2002).

7 HSRC. Number 15. Sportgeskiedskrywing en Dokumentasie. Verslag van die Werkkomitee: Sportgeskiedenis (Pretoria: HSRC, 1982), 31–42.

8 F.J.G. van der Merwe, Sport History. A Textbook for South African Students (Stellenbosch: FJG, 2007), 155.

9 E. Akyeampong, ‘Bukom and the Social History of Boxing in Accra: Warfare and Citizenship in Precolonial GA Society’, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 35, 1 (2002), 45–46.

10 M. Rendell, 2016, ‘Lest We Forget: James Figg, the Father of Modern Boxing, Died 7th December 1734’, mikerendell.com/james-figg-the-father-of-modern-boxing-died-7th-december-1734/, accessed 22 November 2021.

11 F.J.G. van der Merwe, James R. Couper. Vader van Suid-Afrikaanse Boks (Melkbosstrand: FJG, 2015), 4.

12 Van der Merwe, James R. Couper, 4.

13 C. Williams (n.d). ‘Our History’, www.welshathletics.org, accessed 29 December 2018.

14 P.C. McIntosh, Sport in Society (London: C.A. Watts, 1963), 62.

15 M. Arnold, Culture and Anarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1932), 105.

16 Van der Merwe, James R. Couper, 4.

17 H. Snyders, ‘“The Sound of the Hickory”: Baseball, Colonisation and Decolonisation’, in F.J. Cleophas, ed., Exploring Decolonising Themes in SA Sport History: Issues and Challenges (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, 2018), 81–90.

18 V. de Kock, The Fun They Had. The Pastimes of Our Fathers (Cape Town: Howard B. Timmins, 1955), 166.

19 The Cape Argus, 21 October 1857, 2.

20 Welshman, ‘Boxing and the Historians’, 196.

21 S.R. Shell, Indoda Ebisithanda (‘The Man Who Loved Us’). The Reverend James Laing among the amaXhosa 1831–1836. (Cape Town: HiPSA, 2019), 136.

22 Van der Merwe, James R. Couper, 6.

23 H.M. Scheffler, ‘Die Kulturele Lewe van die Diamantdwelwers te Kimberley van 1870 tot 1890’ [The cultural life of the diamond diggers at Kimberley from 1870 to 1890] (MA thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 1976), 41.

24 The Diamond Fields, 23 April 1877, 1.

25 L. Cohen, Reminiscences of Kimberley (London: Bennet, 1911), 13.

26 Cohen, Reminiscences of Kimberley, 202.

27 L. Mallet, The Malay Camp Kimberley. Forceful Removal Imposed by the Apartheid Regime (Kimberley, Sol Plaatje Trust, c.2007), 27.

28 The Cape Times, 10 February 1886, 3.

29 A.P.O. Official Organ of the African People’s Organisation, 25 March 1911, 7.

30 Rules of the Western Province Junior Rugby Football Union (c. 1898). Document in Author’s Collection.

31 Anon (1947). Springboks … Past and Present. A Record of Men and Women Who Have Represented South Africa in International Amateur Sport. 1888–1947. (South Africa: South African Olympic and British Empire Games Association), n.p.; M. Leach and G. Wilkins, Olympic Dream. The South African Connection (New York: Penguin, 1992), 44; SA Clarion, 6 September 1919, 5.

32 SA Clarion, 24 December 1919, 3.

33 H. Adams and H. Suttner, William Street. District Six (Diep River: Chameleon, 1989), 7.

34 SA Clarion, 24 January 1920, 12.

35 The Sun, 10 May 1935, 6; The Sun, 12 July 1936, 8.

36 The Sun, 28 October 1932, 7.

37 The Sun, 30 December 1932, 8.

38 The Sun, 27 October 1933, 5.

39 The Sun, 2 March 1934, 5; The Sun, 20 April 1934, 5,6; The Sun, 27 April 1934, 8; The Sun, 15 June 1934, 8; The Sun, 31 May 1935, 7.

40 The Sun, 10 March 1933, 8; The Sun, 15 June 1934, 8.

41 The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8.

42 The Sun, 31 May 1935, 7–8.

43 The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8.

44 The Sun, 15 June 1934, 8.

45 The Sun, 29 June 1934, 8; The Sun, 6 July 1934, 8.

46 The Sun, 10 May 1935, 6.

47 SA Clarion, 23 August 1919, 14.

48 The Sun, 5 January 1934, 8; A. Booley, Forgotten Heroes. History of Black Rugby. 1882–1992 (Cape Town: M. Booley, 1998), 163.

49 The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8; The Sun, 29 June 1934, 8.

50 M. Gennaro, ‘“Ace Boxing Promoter: Super Human Power”, Boxing, and Sports Entrepreneurship in Colonial Nigeria, 1945–1960’, in M. Ochonu, ed., Entrepreneurship in Africa: A Historical Approach (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), 213–231.

51 A.P.O., Official Organ of the African People’s Organisation, 25 January 1913, 11; Greyvenstein, The Fighters, 415.

52 The Sun, 10 May 1935, 6.

53 Western Cape Archives and Records Services, Boxing Licences, LC 1109/ UC9509.

54 J. Todd, ‘Reflections on Physical Culture. Defining Our Field and Protecting Its Integrity’, Iron Game History: The Journal of Physical Culture, 13, 2 and 3 (2015), 1–8.

55 The Sun, 18 October 1935, 8.

56 J. Loos, Echoes of Slavery. Voices from the Past (Claremont: New Africa, 2004), 47.

57 V.G. Dowling (1841). Fistiana: Or, the Oracle of the Ring: Comprising a Defence of British Boxing; A Brief History of Pugilism, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period; Practical Instructions for Training; Together with Chronological Tables of Prize Battles, from 1780 to 1840 Inclusive (London: W.M. Clement Jr, 1841), 119.

58 D. Booth, The Field. Truth and Fiction in Sport History (New York: Routledge, 2005), 89.

59 The Sun, 10 March 1933, 8.

60 The Sun, 18 October 1935, 8.

61 The Sun, 18 May 1934, 2.

62 The Sun, 24 March 1933, 7; The Sun, 31 March 1933,8; The Sun, 8 June 1934, 2.

63 The Sun, 9 June 1933, 2–3; The Sun, 14 July 1933, 3,7.

64 The Sun, 29 June 1934, 8.

65 Booth, The Field, 89.

66 Booth, The Field, 87.

67 G. Lewis, Between the Wire and the Wall. A History of South African Coloured Politics (New York: St Martin’s, 1987), 20–21.

68 F.J. Cleophas, ‘Physical Education and Physical Culture in the Coloured Community of the Western Cape, 1837–1966’ (PhD thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, 2009), 28; Welshman, ‘Boxing and the Historians’, 197.

69 M. Adhikari, ‘Coloured Identity and the Politics of Language: The Socio-Political Context of Piet Uithalders’, ‘Straatpraatjies’ column, in M. Adhikari, ed., Straatpraatjies. Language, Politics and Popular Culture in Cape Town, 1909–1922 (Pretoria: J.L. Van Schaik, 1996),1–17 (at 7).

70 L. Switzer and D. Switzer, The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho. A Descriptive Bibliographic Guide to African, Coloured and Indian Newspapers, Newsletters and Magazines 1836–1976. (Massachusetts: G.K. Hall, 1979), 34, 61.

71 Switzer and Switzer, The Black Press, 60.

72 R.E. van der Ross, The Rise and Decline of Apartheid. A Study of Political Movements of the Coloured People of South Africa, 1880–1985 (Cape Town: Tafelberg. 1986), 206.

73 Coloured Opinion, 20 May 1944, 1.

74 United Party of South Africa, The White Policy of the United Party (Johannesburg: Information Brochure, 1952), 3.

75 The Sun, 26 May 1933, 5.

76 The Sun, 14 June 1935, 2.

77 The Sun, 27 September 1935, 7.

78 The Sun, 16 June 1933, 7; The Sun, 25 May 1934, 8; The Sun, 1 June 1934, 8; The Sun, 20 July 1934, 8; The Sun, 24 August 1934, 8.

79 The Sun, 16 November 1934, 8.

80 The Sun, 28 April 1933, 7.

81 The Sun, 26 January 1934, 2.

82 The Sun, 22 June 1934, 8.

83 T. Burrows, The Text-Book of Club-Swinging. (London: Athletic Publications Ltd, 1908), 14; The Sun, 17 March 1933, 8; The Sun, 24 March 1933, 8.

84 The Sun, 30 December 1932, 8; The Sun, 23 March 1934, 7.

85 The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8.

86 The Sun, 23 March 1934, 7; The Sun, 20 April 1934, 5, 6.

87 Campbell, To Write as a Boxer; Greyvenstein, The Fighters.

88 The Sun, 21 April 1933, 8; The Sun, 25 August 1933, 2; The Sun, 23 June 1933, 6.

89 Greyvenstein, The Fighters, 415.

90 The Sun, 5 January 1934, 8; The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8.

91 The Sun, 23 February 1934, 8; The Sun, 10 May 1935, 6; The Sun, 14 June 1935, 2; The Sun, 12 July 1935, 8; The Sun, 2 August 1935, 7; The Sun, 16 August 1935, 7.

92 The Sun, 24 May 1935, 8; The Sun, 12 July 1935, 8.

93 For example, see The Sun, 12 July 1935, 8 and The Sun, 19 July 1935, 7–8.

94 P. Lalu, The Deaths of Hintsa. Postapartheid South Africa and the Shape of Recurring Pasts (Cape Town: HSRC, 2009), 5.

95 McIntosh, Sport in Society, 60.

96 N. Marcus (2014). ‘James Figg: Boxing’s First Champion’, www.boxing.com/james_figg_boxings_first_champion.html, accessed 22 November 2018.

97 Henderson, The Negro in Sports, 16.

98 R. Fitzpatrick (2017), ‘Tom Molineaux: The Slave Who Boxed his Way to Freedom before Dying Destitute in Ireland’, https://www.irishexaminer.com, accessed 10 November 2018.

99 Henderson, The Negro in Sports, 16.

100 Fitzpatrick, ‘Tom Molineaux’.

101 Fitzpatrick, Tom Molineaux’.

102 Henderson, The Negro in Sports, 17.

103 Henderson, The Negro in Sports, 22, 24, 37.

104 H. Snyders, ‘“Subservient Jester”? “Gamat” Behardien: Reinterpreting a Marginal Figure in South African Sport History’, in F.J. Cleophas, ed., Exploring Decolonising Themes in SA Sport History: Issues and Challenges (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, 2018), 24.

105 MacLean, ‘Rethinking British’, 3.

106 F. Khan, ‘From Carriers to Climbers: The Cape Province Mountain Club, 1930s to 1960s – an Untold Story’, in F.J. Cleophas, ed., Exploring Decolonising Themes in SA Sport History: Issues and Challenges (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, 2021), 67–79.

107 L. le Grange, ‘Decolonising Sport: Some Thoughts’, in F.J. Cleophas, ed., Exploring Decolonising Themes in SA Sport History: Issues and Challenges (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, 2018), 15–21.