Abstract

Any form of disability renders one more vulnerable to becoming a victim of violence (including sexual abuse) than peers without disability. Within the disability sphere, persons with communication disabilities are particularly vulnerable due to various contributing factors. Despite this heightened risk and the subsequent increased need to seek justice, access to justice remains elusive for these individuals. Their communication disabilities hinder their ability to seek the assistance of police officers, which is the entry point for accessing the justice system. The repercussions are that these cases seldom go to court and in the rare event that they do, the court appears to be unaware and unable to efficiently provide accommodations that would allow individuals with communication disabilities to obtain justice. Augmentative and alternative communication can allow them to exercise their autonomy, to make decisions, and share information. In this paper, several different augmentative and alternative communication methods and strategies are described with a focus on picture-based systems. A recent South African case is used to illustrate how access to justice was achieved using such a system. A potential pitfall when using personally relevant photographs as part of a symbol-based system is alluded to.

1. Introduction

South Africa ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)Footnote1 in 2007, after its widespread international adoption in 2006. The CRPD has since made a significant impact on ensuring that the basic human rights of persons with disabilities are met – across a range of sectors. Access to justice, as outlined in Article 13 of the CRPD, is a prime example for the justice sector. This paper aims to address the complex nexus between the presence of communication disabilities in victims of crime and their right to access justice, with South Africa as the jurisdictional focus. By interrogating this nexus, the value of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is examined. In addition, the competing interests of both the victim and perpetrator that may arise should AAC be used in court, is also examined. Finally, the advantages and potential arguments against using photographs as part of an AAC system within the South African justice system are discussed.

2. Defining communication disabilities

Individuals with communication disabilities are often described as non-speaking, non-verbal, non-oral, or as having little or no speech.Footnote2 Having communication disabilities can impact receptive language (understanding) and/or expressive language and implies that a person cannot rely on speech alone to fulfil all their communication needs.Footnote3 This may range from having some speech, however, with significant articulation difficulties resulting in unintelligible speech, to having no speech at all, rendering such individuals as candidates for using an AAC system, as discussed in the next section of this paper.Footnote4 Furthermore, restricted expressive language (that is, speech) does not necessarily mean that these individuals do not understand language, although their receptive language may also be impacted. In some cases, however, receptive language is not affected at all – think, for example, of the renowned black-hole quantum theorist Dr Stephen Hawking, who had no speech yet could articulate his thoughts using a computer with speech output. Individuals with communication disabilities can be persons of any age, gender, and social background, and can have a range of different coexisting disabilities, such as intellectual disabilities, physical disabilities, sensory disabilities, or multiple disabilities. Furthermore, communication disabilities can be present from birth (for example, a person who never learned how to use speech, or who only has limited speech) or it can be an acquired condition (for example, a person could have lost the ability to speak following trauma, such as a motor vehicle accident, or due to illness, such as a stroke) resulting in an inability to continue communicating in conventional ways. Irrespective of the specific medical diagnosis (for example, autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, to name a few), what these individuals have in common is that their limited speech ability negatively affects their interaction with others, hampers their participation in several activities across different environments (for example, disclosing abuse to a trusted person, giving a statement to the police, or testifying in court), and ultimately restricts their independent functioning in society.

In many instances, communication disabilities are also associated with having limited literacy skills. Although a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this paper, poor literacy skills can be attributed to a plethora of contributing reasons, amongst others: the focus on the care of children with disabilities to the detriment of learning; the high number of children with disabilities who are currently not attending school; poor access to schools, particularly in rural areas due to limited or no transport options; insufficient teacher training – specifically in terms of best teaching practices in literacy and teachers’ limited experience in teaching functional literacy; low literacy expectations from children with disabilities; and insufficient infrastructure in terms of the lack of teaching and learning materials as well as support services (for example, remedial teachers or therapists to assist teachers).Footnote5 Children with disabilities are sometimes not sent to school by their primary caregiver, in an attempt to protect them from shame and stigma through name-calling and threats by their peers who might wish to humiliate and degrade them.Footnote6 Limited or no education of the victim is seen as a major obstacle in the legal system.Footnote7 This aspect increases their isolation and strengthens discrimination practices which also increases the possibility of becoming victims of abuse and neglect. A lack of literacy may thus delay and hamper language acquisition, general knowledge, vocabulary development, social acceptance, and quality of life. In contrast, literacy is power, and it transforms lives – it is the key to accessing knowledge, gaining independence, and making choices – also for individuals with communication disabilities. Once individuals with communication disabilities learn to read and write, more opportunities become available to them via literacy-based communication systems. This, in turn, will have a positive effect on their decision-making abilities, which allows more power and control in interaction. Technology goes a long way in assisting with the development of literacy skills.

In summary, persons with communication disabilities can be empowered to share their needs and thoughts if they are provided with appropriate communication systems. Misperceptions and myths (for example, if a person cannot use speech, some mistakenly take it to mean that the person does not want to communicate, or that the person has nothing to say) should be addressed and dispelled. Likewise, the inability to use speech does not mean that a person does not understand the interaction and therefore cannot participate – with appropriate and available communication support, participation is possible. Finally, if a person cannot learn to speak, it does not mean that they do not have the potential to learn other ways of communication. In the section that follows, AAC systems as a means of interaction for persons with communication disabilities are discussed, and examples of the various AAC options are provided.

3. Augmented and alternative communication: What is it, and how can it help to ensure access to justice for persons with disabilities?

Individuals with communication disabilities face a diversity of challenges that impact their ability to access the criminal justice system.Footnote8 AAC has been advocated as a method to provide accurate testimony and in doing so, break the silence of crime survivors who have communication disabilities,Footnote9 yet, very few South African cases have been heard in court where the victims used AAC to testify.

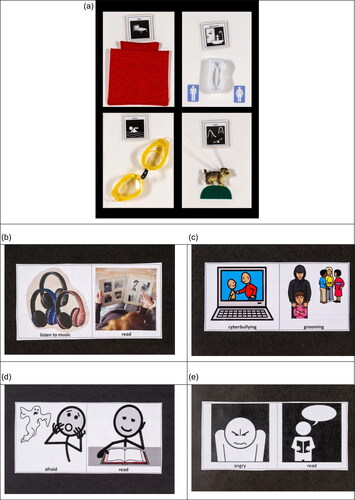

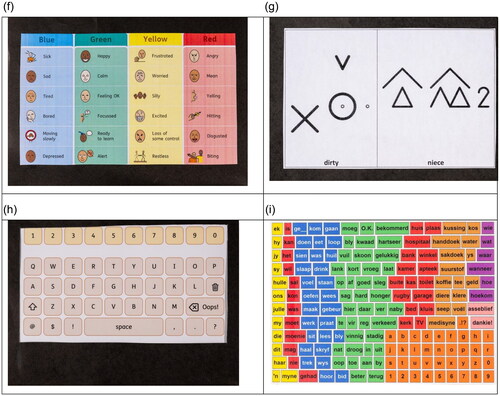

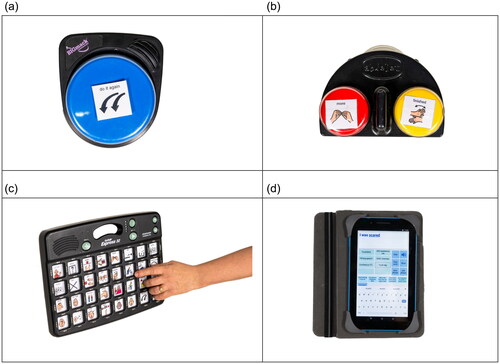

AAC refers to less frequently used methods and techniques of communication that support or replace spoken communication and to facilitate better functioning of persons with communication disabilities in society.Footnote10 AAC is typically divided into unaided systems as depicted in (systems that rely on the person’s body to convey messages, such as natural gestures (), pointing (), facial expressions (), sign language (), and finger spelling (), and aided systems as depicture in (systems that involve something in addition to the person’s body, such as objects (), photographs (including personally relevant and commercially available photographs (), different graphic symbols (a variety of symbol sets and systems –g)) or traditional orthography, that is, alphabet letters (,i)).

Figure 1. Unaided AAC systems. (a) Natural gesture depicting ‘Good bye’. (b) Pointing depicting ‘time’. (c) Facial expressions depicting ‘angry’. (d) Sign language: South African Sign Language (SASL) depicting ‘outside’. (e) Fingerspelling depicting the letters L-A-W to spell the word ‘law’.

Figure 2. Aided AAC systems. (a) Object symbols depicting ‘bedroom’, ‘bathroom’, ‘swimming’ , and ‘park’. (b) Photographs depicting ‘listening to music’ and ‘reading’. (c) Graphic symbols: Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) depicting ‘cyber bullying’ an ‘grooming’ https://goboardmaker.com/pages/picture-communication-symbols. (d) Graphic symbols: Symbolstix depicting ‘afraid’ and ‘to read’ https://www.cricksoft.com/uk/products/symbol-sets/symbolstix. (e) Graphic symbols: Bildstöd depicting ‘angry’ and ‘to read’ https://bildstod.vgregion.se/. (f) Graphic symbols: Widgit symbols depicting a range of emotions https://www.widgit.com/. (g) Graphic symbols: Blissymbols depicting ‘dirty’ and ‘niece’ https://www.blissymbolics.org/. (h) Traditional orthography board depicting only alphabet letters. (I) Traditional orthography board depicting both alphabet letters and written words.

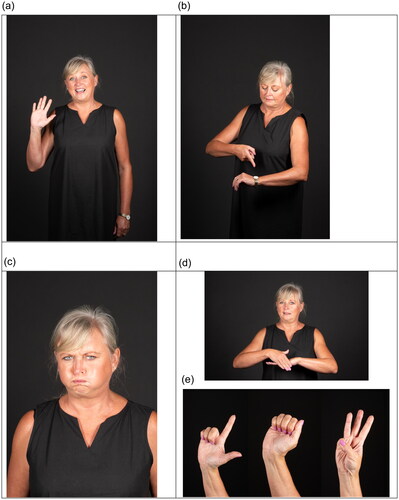

Aided symbols can be presented on paper-based systems, such as communication boards and books, or on technological devices with speech output as depicted in . These devices can range in complexity from ones that have a fixed number of options such as the BIGMack with one option (), the iTalk2 with two options (), or the GoTalk Express 32 with 32 options (), that would not require a potential user to be literate to extremely sophisticated high technology devices that use specific applications and software, such as a tablet with Speech Assistant AAC APK (). This type of text-to-speech device would require literacy skills.Footnote11

Figure 3. Technological devices with speech output. (a) BIGmack https://www.ablenetinc.com/bigmack/. (b) iTalk 2 https://www.ablenetinc.com/italk2/. (c) GoTalk Express 32 https://www.attainmentcompany.com/gotalk-express-32. (d) Tablet with Speech Assistant AAC APK https://speech-assistant-aac.en.softonic.com/

This paper focuses specifically on an aided communication system (picture-based symbols) that can be used by persons with communication disabilities who have limited to no literacy skills since this constitutes the largest proportion of individuals with communication disabilities.Footnote12

Picture-based symbols are typically recommended for individuals with communication disabilities who are not (yet) literate, as these symbols offer the most credible alternative vocabulary, making it critical and fundamental for both children and adults with communication disabilities. Such graphic symbols can be retrieved from commercially available symbol libraries, such as Picture Communication SymbolsTM (PCS) (as shown in ), SymbolStixTM (as shown in ), Bildstöd (as shown in ) or WidgitTM (as shown in ) or can be in the form of self-drawn pictures or photographs (as shown in ).Footnote13

Graphic symbols function in different ways. Some represent an encoding system whereby different symbol sequences are used to encode words (Minspeak), for example, all colours would start with the icon sequence of the rainbow, followed by a second icon. Therefore, to indicate yellow one would use the rainbow icon followed by the sun icon; to indicate red, one would use the rainbow icon followed by a red apple icon; and for green, one would use the rainbow icon followed by a green frog icon, and so forth. Other symbol systems, such as Blissymbols (as shown in ), are concept-based and have a simple language structure that includes specific language indicators that could change the meaning of the word. For example, a noun (for example, ear) could be changed to a verb by adding the verb indicator (for example, ear changed to hear). In the same way, this word would be changed to the future tense by adding a future tense indicator (for example, ear changed to will hear) or to the past tense by adding a past tense indicator (for example, ear changed to heard). A large proportion of picture-based symbols attempt to use a picture to represent a single word or concept, for example, in Picture Communication SymbolsTM (PCS), an easily guessable picture of a car represents a car, or a picture that shows a thumbs up means yes. These types of picture symbols have a straight-forward one-symbol-one-concept relationship, with the perceived advantage of being easy to learn as the picture-symbols represent concepts in a way that might be easy to guess or learn (iconicity hypothesis), although this hypothesis has been challenged.Footnote14 This hypothesis indicates that the visual representation of graphic symbols may facilitate the learning and memory of symbol-referent associations. In other words, symbols that resemble their referents more closely (in other words, symbols with high transparency), will be easier to learn and remember than those with a weak visual resemblance.Footnote15

Often when introducing graphic symbols, photographs of real objects, places, and persons will be used since this represents the most direct resemblance between a real 3-D concept and its 2-D representation. As alluded to earlier, these photographs can be displayed on communication boards and books or on devices with speech output. Presenting photographs in specific categories (for example, people in the family, people at school, people at swimming lessons and so on), makes it easy for children and adults with communication disabilities who have limited literacy skills to learn how to swipe through a series of photographs and then identify and stop at the one they are trying to find. In a study with post-stroke adults, it was reported that although these adults found both photographs and line drawings helpful, they preferred and used the photographs more frequently.Footnote16 These researchers also compared the use of personally relevant photographs as opposed to general photographs and found that personally relevant photographs are the preferred option.

One of the key challenges of learning how to use an AAC system depends on how quickly the individual can learn to associate the specific picture symbol with the word it represents and with the specific communication function it aims to address.Footnote17 For example, if the person can associate a picture symbol of a glass with the concept I am thirsty, the picture can then be used to request a drink I want a drink please (communication function). Therefore, when training a person to communicate using picture symbols, symbols that are easily guessable without any previous training (that is, have high transparency) and symbols that are easily learnable (that is, have high translucency) should be selected as they promote symbol learning and comprehension.Footnote18 The use of picture symbols has been found to improve understanding (receptive language), literacy, and expressive communication significantly for both children and adults with communication disabilities and is therefore imperative to their communicative competence.Footnote19 Picture symbols are typically perceived as being relatively easy to use; they do not require literacy skills to be understood and used. Moreover, they are easily understood by partners, as the picture symbol is always accompanied by a written word, and when symbols are used on devices with speech output, the device speaks the message (for example, I want the toilet please). Picture symbols are also less context- and partner-dependent than some unaided forms of communication (for example, gestures and facial expressions) hence, no interpretation is needed. For example, an outsider without any AAC training, such as a lawyer or judge, can see what picture symbols the person with communication disabilities is pointing at – and by reading the accompanying word, understand the meaning of the message. This aspect holds potential for the legal justice system.

At the same time, picture symbol systems have limitations. Picture symbol vocabularies are typically dominated by nouns and, to a lesser degree, verbs, since these words are typically picture producers, which means that the visual relationship between the object and the picture symbol can be captured. Although picture symbols may initially appear to be easy, it soon becomes apparent that not all words are picture producers, for example, the concept of jealousy. A communication system that is predominated by picture symbols which are focused on nouns and verbs, may in practice, allow a person to communicate by providing telegraphic cues to convey the message. The communication partner co-constructs the message by, for example, asking yes/no questions to clarify what the person who is using the system wants to express.Footnote20 Using picture symbols successfully depends on the agency of the person with communication disabilities in generating a message. It also depends on the success with which the true intent of the message can be communicated which is dependent on the communication partner’s skill in interpreting the communication method, whether it be picture symbols, facial expressions, or gestures. The role of the communication partner in encouraging the person to express their message, without imposing a personal bias or opinion as to what they think the person wants to say (that is, putting words in the person’s mouth) is also important. One way of addressing this challenge is by including core vocabulary, a small set of high-frequency, re-usable words that make up around 80 per cent of our spoken words.Footnote21

Furthermore, picture symbols do not consist of meaningless sub-units that can be combined (as is the case with true languages where letters are combined to produce words, such as h-e-l-p). These types of picture-based AAC systems thus lack generativity, as each symbol represents one meaning, which implies that the person’s ability to compose messages is restricted and is limited to the picture symbols that are available on the system. It would thus appear that having more picture symbols available would be better, however, this, unfortunately, increases the memory load – as a person needs to remember where all the symbols are stored to retrieve them when needed to communicate a particular message. To assist with retrieval, frequently used symbols are typically stored in a particular location, for example, I might always be stored in the top left-hand corner on all the pages of a communication book/board or on the device, while finished might be stored in the bottom right corner on all the pages in the communication book. The person using the system therefore needs to memorise the location of the picture symbol and in the case of a device with speech output, this might mean navigating various screens. It is therefore evident that the size of the vocabulary displayed on the communication book/board or device is thus proportional to the person’s memory skills in retrieving these symbols.Footnote22 Speech-language therapists will therefore consider evidence-based practice techniques for selecting the appropriate vocabulary size for an individual, and considering how these symbols will be organised on either the communication book/board or on the device and explain this to the court.

Therefore, choosing the appropriate vocabulary for a picture-based communication system is of great significance and requires ensuring that the appropriate and applicable words are available so that the person can convey the specific message. In the legal system, this is of particular significance as it should also ensure that the vocabulary is large enough so that there can be no question of leading the witness. If a person’s vocabulary is restricted at any given time, to the words selected for him/her by others (for example, a parent, therapist, teacher, friend), it automatically raises a question in terms of the authorship of the message. Are the messages truly those that the person using the pictures would like to express? Does the mere presence of certain vocabulary items on the board or device lead a person to express certain messages and thus, put words in their mouths? Conversely, certain words may specifically be omitted from the board or device so that the person using the system does not have access to them. BrewsterFootnote23 discusses a case example of carers’ reluctance to include swear words on the device of a young adult, words that a speaking peer would have access to. They explained that excluding such words on the user’s system would be an implicit sanction on their behalf for the use of such words. In this, too, the question is raised – who is the author of the message?

Following this discussion on what AAC is, a subsequent question is raised, namely why is it important to consider the use of AAC within the criminal justice system? This question is addressed by briefly discussing why persons with communication disabilities are at higher risk of becoming victims of violence.

4. Violence against persons with communication disabilities

Both children and adults with disabilities are at a higher risk of becoming victims of violence (including sexual abuse) than members of the general population.Footnote24 Due to the continued scarcity of conclusive evidence regarding specific patterns of violence against persons with communication disabilities,Footnote25 particularly in low- and middle-income countries, including South Africa, data will mostly refer to the global North. Survey data from the United States of America taken from approximately 43 000 university students, showed that disability was a significant risk factor for victimisation.Footnote26 This risk was quantified in another US study, stating that persons with disabilities are four to ten times more likely to become victims of violence than their counterparts without disabilities.Footnote27 Two meta-analyses showed that violence was the type of crime both childrenFootnote28 and adults with disabilities are most exposed to.Footnote29

Reports comparing the nature of abuse show that violence against persons with disabilities tends to be more severe than violence against their peers without disabilities, consists of multiple or different forms of abuse, has a longer duration, and is typically repetitive (that is, not once-off events).Footnote30 Trauma research has also shown that its effect increases if the abuse continues over time, negatively impacting the individual’s well-being and quality of life.Footnote31 Individuals with disabilities who are victims of violence may experience depression, develop feelings of shame and guilt, lose trust in others, and display irrational fears that can lead to them becoming socially withdrawn, self-injurious, non-compliant, and demonstrating promiscuous sexual behaviour.Footnote32

Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson’sFootnote33 routine activities theory can assist in conceptualising the victimisation of persons with communication disabilities as it focuses on what is necessary for a crime to take place and hence, it can also create an awareness of how to prevent crime and victimisation. This theory concentrates on what creates an atmosphere for crime to occur. In other words, the circumstances in which a motivated offender carries out a predatory criminal act (or multiple acts) on an available victim, in the absence of a capable guardian. Routine activities theory consists of three variables that must be present for a crime to occur: a suitable victim, a lack of capable guardianship, and a motivated offender.Footnote34 In applying this theory to persons with communication disabilities, it would mean that the offender is typically a carer (for example, partner, family member, or paid carer) who may be motivated to offend due to carer stress, or due to a provocative or frustrating incident, against a victim who is easily accessible in their home (availability of a suitable victim) and who has less protection since the offender is also the carer (absence of a capable guardian). In the case of violence against persons with communication disabilities, the criminal act may also be facilitated by an increased potential on the side of the offender to evade prosecution (motivated offender).Footnote35 Furthermore, routine activity theory is based on the idea that certain situations can provide opportunities for crime and that some situations are more favourable for crime than others. This implies that the situations in which persons with communication disabilities find themselves (for example, at home with a specific carer, unsupervised at home, in a special school for children with disabilities, or in a group home for adults with disabilities) may increase their risk of being a victim of violence. The lifestyle of individuals with communication disabilities thus provides an increased opportunity for crime to take place, since the guardian may be incapable of protection and offenders see them as easily accessible targets.Footnote36 As such, the victimisation of persons with communication disabilities can be seen as the product of a complex interplay between providing potential offenders with increased access to potential victims – in the absence of capable guardians.

In line with routine activities theory, there is existing research that shows that a substantial proportion of persons with disabilities are victimised by persons with whom they have a relationship of trust and dependency. For example, a Dutch study showed that two-fifths of the alleged perpetrators were friends or acquaintances,Footnote37 while a US study reported that in 40 per cent of cases, the crimes were conducted by someone well-known to the victim.Footnote38 As is the case with sexual offences, aggravated abuse, and abuse in close relations (also with persons with disabilities) involve personal relationships and relationships of trust. A landmark study by Dick Sobsey and Tanis Doe in 1991 reported that 44 per cent of offenders had contact with victims through disability services and were thus, less likely to recognise or report a crime due to the apparent legitimacy of the disability service.Footnote39 Similarly, an Australian study that reported on the lived experiences of 36 women with disabilities recounted abuse that occurred in conjunction with the provision of care.Footnote40

Perpetrators see victims with communication disabilities as vulnerable,Footnote41 and they exploit this vulnerability. They often believe that victims are unable to seek help or report crime due to the impact of the communication disability,Footnote42 and therefore, they have little or no fear of the consequences of their acts.Footnote43

Following this discussion on the increased risk of persons with disabilities becoming abuse victims, the next section will focus specifically on the challenges they experience in accessing the justice sector.

5. Persons with communication disabilities and access to justice

In the previous section, an argument was built to show that persons with communication disabilities have a heightened risk of becoming victims of violent crime, and the possible reasons for that were unpacked. In this section, the specific challenges experienced by these individuals when they attempt to access the criminal justice system are provided.

Persons with communication disabilities face multiple barriers when trying to access justice.Footnote44 These individuals might find it difficult to access the justice system as they often do not have access to the vocabulary needed to report the crime and/or give a statement. As indicated earlier, when routine activities theory was described, if violence occurs at the hands of carers, the health and safety of persons with communication disabilities are compromised.Footnote45 Often the alleged perpetrator might be known to them – it may even be their trusted carer – and the names of these individuals are frequently not displayed on communication systems as they are typically present (that is, with the person) implying that their names are nor needed, or they may choose to not have their names on the communication system. Hence, filing a complaint, without being able to indicate a specific person’s name is challenging.Footnote46

Persons with communication disabilities might also experience difficulties in coping with police interviews and legal formalities as a direct result of their disability, which contribute to, for example, incomplete information which in turn compromises the successful apprehension and prosecution of the perpetrator(s).Footnote47 These difficulties may also be because of their specific form of communication and the vocabulary that they have access to. In many cases, when discussing abuse, persons with communication disabilities might use idiosyncratic or childlike words to describe private body parts (for example, ‘my peepee’) – which presents challenges when testifying in sexual abuse cases.Footnote48

Persons with communication disabilities have also reported that when they attempt to report a crime, they perceive the treatment they receive from police officers, who are the first point of contact with the criminal justice system to be unfair and unjust.Footnote49 Some victims feel that police officers are disrespectful because of their disabilities and that they appear to lack credibility within the criminal justice system.Footnote50 This could contribute to the fact that research has shown that persons with disabilities, particularly those with communication disabilities, rarely report Footnote51cases of abuse against them to the police,Footnote52 which in turn means, very few of these cases are investigated and tried in court.Footnote53 Hence, criminal case data on persons with disabilities as alleged victims is sparse.

In the police force, many negative attitudes, perceptions, false beliefs, myths, misconceptions, and stereotypes exist regarding persons with disabilities.Footnote54 Scott Modell and Suzanna Mak note that police officers identified their lack of knowledge regarding disability as the most challenging barrier in offering services to persons with disabilities.Footnote55 Jennifer Keilty and Georgina Connelly suggest that this stems from limited knowledge, information, and exposure to persons with disabilities, which then results in poor quality (or sometimes no) statements being taken from these individuals. Hence, many cases do not proceed through the criminal justice system due to the lack of a credible statement taken by the police.Footnote56 In a large Australian study, police officers mentioned attitudinal barriers due to limited knowledge and skills and stated that their feelings of uncomfortableness are transferred onto the victim, leading to the victim feeling uncomfortable when reporting a crime.

In the event of a case being heard in court, persons with disabilities, specifically those with communication disabilities, face multiple barriersFootnote57 starting from when they report a crime to the police as discussed earlier, to the court process.Footnote58 They might have difficulty understanding the complex maze of rules and practices that make up the court proceedings due to restricted receptive language skills.Footnote59 Such persons might also have difficulties testifying and giving evidence, due to restricted expressive language skills, resulting in their credibility as complainants being questioned.Footnote60 In certain situations, they may also show difficulties with decision-making tasks due to their restricted (or inappropriate) available vocabulary stemming from the fact that AAC systems are not typically developed with the aim of testifying in court. The vulnerability of these persons to access the criminal justice system is thus significantly impacted by their communication disability.

To be able to access the courts is one of the many, yet fundamental steps towards being able to access the justice context. Knowledge regarding the legal system as well as financial means are necessary to access it (through legal representation), thereby creating a hurdle to the project of having access to justice.Footnote61 If this proposition holds true for typical South African citizens, what magnitude of effect might be anticipated for persons with communication disabilities? Before considering Human Rights when proceedings have started, the right to have access to justice for persons with communication disabilities must first be considered. In instances where the primary caregiver is not the alleged perpetrator, such a caregiver might have the best intentions to support the individual, however, in the same way as most South Africans, not be aware of the correct procedures to follow to obtain justice. As mentioned, money, or the lack thereof, is as restrictive as knowledge. The vicious poverty-disability cycle is well known with poverty being regarded as both a cause and a consequence of disability.Footnote62 In a society where even those individuals who earn an income struggle to access the legal system, non-working individuals (which constitute most persons with disabilities in South Africa) will in most instances, have even fewer financial resources to obtain justice. Disability grants in South Africa are a maximum of R1,980 per month.Footnote63 Jackie Dugard and Katherine Drage noted in 2013, that an initial consultation (excluding further consultations and litigation costs) cost R1 500.Footnote64 In 2024 this would equate to an amount of R2,610.14 using an annual inflation rate of 5.2 per cent. Hence legal representation and therefore access to justice is not always a viable prospect for persons with disabilities in South Africa.

In cases where persons with disabilities can physically access the court, the next hurdle presents itself which is the legal formalities in the courtroom. The court system is often regarded as unapproachable, with a range of legal formalities, and a complex maze of rules and practices that make up the court proceedings, formal legal language, and even formal court attire (for example, robes) which create a sense of uncertainty in persons with disabilities who do not understand the context. Besides difficulties with language production (speech) and understanding (receptive language), these individuals might also experience difficulties with fluctuating concentration, memory, placing situations in time, and the speed of processing information.Footnote65 Furthermore, persons with disabilities are more vulnerable to suggestibility, confabulation, acquiescence, pseudo-memories, and imagination,Footnote66 resulting in their credibility as witnesses being questioned.Footnote67

However, access to justice, or the lack thereof, is not solely a South African or even an African conundrum. A recent Norwegian studyFootnote68 shows that in a large proportion of cases that were prosecuted in which the victims were adults with disabilities, the reported conviction rate was low (only one out of ten cases resulted in unconditional imprisonment) compared to their official crime that showed that one out of four of the prosecuted cases involving sexual abuse and violence concludes with unconditional imprisonment. In simple terms, human rights are only capable of being protected should one have access to the justice system. As indicated above – this is seldom the case for persons with communication disabilities. To analyse and argue the human rights of persons with communication disabilities would be a futile exercise if one cannot accept that it would be of no practical value since access to justice (which has proven nearly impossible for persons with communication disabilities) and the protection of such rights are inextricably linked. Systems are needed which would ensure that persons with communication disabilities can take part in judicial proceedings – which in turn, would allow for a constructive discussion relating to human rights. The issues faced by individuals with communication disabilities in accessing the justice system are undeniably human rights concerns, rooted in the principles of equality before the law and equal protection and benefit of the law, as well as the fundamental rights to freedom from unfair discrimination, the right to life, human dignity, and freedom and security of the person. Without addressing these barriers mentioned above to justice, the discourse on human rights for individuals with communication disabilities remains theoretical, highlighting the urgent need for practical solutions that enable their meaningful participation in legal proceedings and ensure their equal protection under the law. In the remaining sections of the paper, a South African example is provided, followed by a discussion of the viability of using AAC in South African courts from a human rights perspective.

6. Setting a precedent: A South African example

South African legal precedent was set when R (pseudonym),Footnote69 a non-literate young girl with cerebral palsy (spastic quadriplegia) and communication disabilities, successfully testified in court in Upington, Northern Cape Province, South Africa, using a picture-based AAC system with Afrikaans synthetic speech output in February 2020. R had never attended school, as there was no available school in the area that could accommodate her special needs. She had received a few speech-language therapy sessions at the local hospital.

R was fourteen years old when the case was finally heard in court – after almost seven years. R was raped by a family friend when she was seven years old. R disclosed the rape to her mother. The alleged perpetrator was arrested; however, due to the lack of evidence, and R’s inability to communicate using speech, the alleged perpetrator was released without any negative consequences for him. Shortly thereafter, R’s grandmother became her legal guardian. In 2017, the case was reopened due to the tenacity of a social worker involved in the case, and R was supported by the National Prosecuting Authority as well as various disability organisations. In August 2020, the alleged rapist was found guilty and sentenced to eight years imprisonment. R’s testimony, using a picture-based AAC system, played a significant role in the conviction, as she was able to answer specific questions both when giving evidence in chief and during cross-examination.

This case, the first of its kind in South Africa, broke new ground in the country’s judicial system. It illustrated the role AAC can play in facilitating access to justice for a non-literate child with communication disabilities.

7. Objections to picture-based augmentative and alternative communication systems in a South African court: A human rights perspective

R’s case was the first of its kind, and therefore, it should be analysed in the South African legal landscape. R used a picture-based AAC system that did not include personally relevant questions. photographs. Had this, however, been the case, additional aspects would have been considered. In the legal context, using personally relevant photographs as part of a comprehensive AAC system begs the question – is permission needed from specific individuals to place their photographs on an AAC system? Individuals who use speech can talk about friends, family, and even people whom they do not like, without these persons’ permission. Considering that an AAC system (with photographs) is seen as the voice of a person with communication disabilities – should they not be afforded the same opportunity as those without disabilities?

Considering the violence against persons with communication disabilities and the frequency with which the alleged perpetrators are known to them, it would seem logical that these alleged perpetrators might refuse permission for their photographs to be uploaded onto the AAC system. In doing so, they are effectively ‘silencing’ these victims for disclosing abuse. Should the right to privacy of data (by an alleged perpetrator) weigh heavier than the right to expression of speech by a victim? With the advent of the fourth industrial revolution, the right to privacy is one of the dominant areas of discussion in South Africa.

One of the most contentious pieces of legislation in the South African legal landscape is the Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act 4 of 2013. One can argue that a potential difficulty may arise in situations in court where a victim seeks to deliver testimony by way of making use of photographs as part of an AAC system, as an alleged perpetrator may argue that in terms of s 11(1)(a) of the POPI Act, consent is required for personal data (such as photographs) to be used. Section 18 of the POPI Act also specifies that individuals must be notified when their data is processed. Conversely, denying a person with communication disabilities the opportunity to rely on AAC to deliver testimony (which may include the use of photographs), would impact several human rights – such as the right to equality and dignity – as well as procedural rights, such as the right to a fair trial. Hypothetically, contentious issues might arise in court when the victim seeks to testify or identify the accused, especially through photographs as discussed earlier.

When dealing with this delicate balance of the right to speak versus data protection laws, the courts should consider the following: Firstly, it should be noted that a person’s ability to speak about other people cannot be limited in terms of legislation, even when extreme emotions exist between the parties. Naturally, this would exclude defamatory statements. Persons with communication disabilities who rely on AAC systems to communicate should be afforded this same right to talk about other people. It is closely linked with the right to freedom of expression/opinion, which is enshrined in legislation in most democracies around the world and specifically in the Bill of Rights in the South African Constitution.

Secondly, people have a right to talk about someone, not only in terms of freedom of opinion/expression but also when reporting them to the relevant authorities when someone’s rights have been infringed. If a person’s manner of reporting is via a photograph (as in the case with some AAC systems), the right to protection should not be overridden by the right to privacy or data laws. In safeguarding the fundamental human right to protection, especially for vulnerable individuals utilising alternative communication methods, such as photographs or other AAC systems, it is imperative to strike a delicate balance, ensuring that the right to report violations is not unduly constrained by privacy or data laws, thereby upholding justice, accountability, and the principles of human rights. Surely, any reliance on legislation (for example, the POPI Act) to curtail a victim’s freedom of expression must be unconstitutional. Furthermore, a mere protection of a perpetrator’s privacy will amount to an infringement of a victim’s right to dignity and equality, should the victim be barred from using photographs which in turn, would nullify the use of an AAC system. One possible suggestion is that the inclusion of photographs within an AAC system to testify is that it follows the same requirements/procedures applicable to an identification parade. Section 37(1)(b) of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 sets out these requirements. Another suggestion is that persons with communication disabilities could spell out the name (or any other identifying features of the alleged perpetrator) using AAC methods, should they have the literacy skills to do so. This suggestion would circumnavigate a perpetrator’s POPI Act defence altogether.

The South African judiciary is eager to allow persons with communication disabilities to testify since s 7 of the Criminal and Related Matters Amendment Act 12 of 2021 now allows any form of communication to be seen as viva voce, should the person have disabilities that render them unable to speak. However, it is important to note that the possible objections discussed in this section are based on the authors’ opinions, and ultimately, the legal arguments will need to be decided by a court, should they arise in the future.

8. Conclusion

The court must establish legal precedents by handling cases to address the utilisation of picture-based AAC systems. This is particularly crucial when addressing the use of photographs and other potential constraints in cases where individuals with communication disabilities are striving for equal access to justice.

Picture-based symbols can be used successfully to increase communication and participation in the legal context. A multi-disciplinary approach is needed, where speech-language therapists can work with legal practitioners to circumvent the challenges brought on by using picture symbols, such as selecting and programming the appropriate vocabulary, organising how the vocabulary will be displayed, and finally, how the person will be trained in using the AAC system. Legal practitioners should also be trained in using appropriate questioning techniques when a victim or alleged perpetrator uses an AAC system.

Nevertheless, as previously explored in this paper, individuals with communication disabilities frequently do not have guaranteed access to justice due to the numerous obstacles they encounter. Courts cannot set a precedent if cases do not end up in court. Obtaining justice is often a very time-consuming practice, as was seen in the seven-year time span in R’s case. Moreover, drafting or amending legislation to remedy this situation is no easy feat. South African victims with communication disabilities appear to be caught in a state of uncertainty and indecision when it comes to laying charges against someone who has hurt or abused them. Accessing the legal system and seeking justice through courts is by no means easy for these vulnerable individuals and when access is achieved, they might still face a plethora of hurdles when eventually testifying. A solution is urgently needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mariki and Lourens Uitenweerde (EyeScape Photography) for the time and effort spent on carefully considering different angles and backgrounds to ensure that each of the photographs specifically taken for this manuscript capture the essence of the constructs, thereby enhancing the understandability of the text.

When the paper was submitted, the corresponding author was a professor at the Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Pretoria.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juan Bornman

Juan Bornman, professor, Stellenbosch University; research fellow, University of Pretoria; registered speech-language therapist, Health Professions Council of South Africa

Heinrich Gustav Bornman

Heinrich Gustav Bornman, candidate attorney, Weavind and Weavind Attorneys Inc.

Notes

1 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

2 J Bornman ‘Preventing abuse and providing access to justice for individuals with complex communication needs: the role of augmentative and alternative communication’ (2017) 38 Seminars in Speech and Language 321.

3 DR Beukelman & JC Light Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs 5 ed (2020).

4 J Sigafoos, RW Schlosser & D Sutherland ‘Augmentative and alternative communication’ in JH Stone & M Blouin (eds) International Encyclopaedia of Rehabilitation (2010).

5 J Bornman ‘Developing inclusive literary practices in South African Schools’ in M Milton (ed) Inclusive Principles and Practices in Literary Education (2017) 105.

6 TN Phasha & D Nyokangi ‘School-based sexual violence among female learners with mild intellectual disability in South Africa’ (2012) 18 Violence Against Women 209.

7 R Jewkes, Y Sikweyiya, R Morrell & K Dunkle ‘Understanding men’s health and the use of violence: Interface of rape and HIV/AIDS in South Africa’ (2009) South African Medical Research Council.

8 R White, J Bornman, E Johnson & D Msipah ‘Court accommodations for persons with severe communication disabilities: A legal scoping review’ (2021) 27 Psychology, Public Policy and Law 399.

9 Bornman (note 2 above).

10 Beukelman & Light (note 3 above).

11 J Bornman, A Waller & LL Lloyd ‘Background, features and principles of AAC technology’ in D Fuller & LL Lloyd (eds) Principles and Practices in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (2023) 192.

12 Beukelman & Light (note 3 above).

13 J Bornman & K Tönsing ‘Augmentative and alternative communication’ in E Landsberg, D Krüger & E Swart (eds) Addressing barriers to learning: A South African Perspective 4 ed (2019) 215.

14 CH Huang & PJ Lin ‘Effects of symbol component on the identifying graphic symbols from EEG for young children with and without developmental delays’ (2019) 9 Applied Sciences 1260.

15 FT Loncke, J Campbell, AM England & T Hayley ‘Multimodality: A basis for augmentative and alternative communication-psycholinguistic, cognitive and clinical/educational aspects’ (2006) 38 Disability and Rehabilitation 169.

16 J Griffith, A Dietz & K Weissling ‘Supporting narrative tells for people with aphasia using augmentative and alternative communication: photographs or line drawings? Text or no text?’ (2014) 23 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 213.

17 Bornman et al (note 11 above).

18 Loncke et al (note 15 above).

19 Bornman & Tönsing (note 13 above).

20 C Binger, J Kent-Walsh, N Harrington & QC Hollerbach ‘Tracking early sentence-building progress in graphic symbol communication’ (2020) 51 Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 317.

21 E Laubscher & JC Light ‘Core vocabulary lists for young children and considerations for early language development: A narrative review’ (2020) 36 Augmentative and Alternative Communication 43.

22 Bornman & Tönsing (note 13 above).

23 S Brewster ‘Saying the ‘F-word…in the nicest possible way’: Augmentative communication and discourses of disability’ (2013) 28 Disability and Society 125.

24 J Taylor, K Stalker & A Stewart ‘Disabled children and the child protection system: A cause for concern’ (2016) 25 Child Abuse Review 60.

25 TH Åker & MS Johnson ‘Sexual abuse and violence against people with intellectual disability and physical impairments: Characteristics of police-investigated cases in a Norwegian national sample’ (2020) 33 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability 139–145.

26 BW Reyns & H Scherer ‘Stalking victimization among college students: The role of disability within a lifestyle-routine activity framework’ (2018) 64 Crime and Delinquency 650.

27 SL Martin, N Ray, D Sotres-Alvarez et al ‘Physical and sexual assault of women with disabilities’ (2006) 12 Violence Against Women 823.

28 L Jones, MA Bellis, S Wood et al ‘Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systemic review and meta-analysis of observational studies’ (2012) 380 The Lancet 899.

29 K Hughes, MA Bellis, L Jones et al ‘Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systemic review and meta-analysis of observational studies’ (2012) 379 The Lancet 1621.

30 LE Powers, RB Hughes & EM Lund ‘Interpersonal violence and women with disability: A research update’ (2009) VAW-Net, a project of the National Resource Centre on Domestic Violence/Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

31 J Macintosh, J Wuest, M Ford-Gilboe et al ‘Cumulative effects of multiple forms of violence and abuse on women’ (2015) 30 Violence and Victims 502.

32 JG Kheswa ‘Mentally challenged children in Africa: Victims of sexual abuse’ (2014) 5 Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 959.

33 LE Cohen & M Felson ‘Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach’ (1979) 44 American Sociological Review 588.

34 Reyns & Scherer (note 26 above).

35 BC Fogden, SDM Thomas, M Daffern & JPR Ogloff ‘Crime and victimisation in people with intellectual disability: A case linkage study’ (2016) 16 BMC Psychiatry 1.

36 KL Arney ‘Perceptions, lived experiences, and environmental factors impacting the crime reporting practices of private college students’ (2019) doctoral thesis, Walden University.

37 PM van den Bergh & J Hoekman ‘Sexual offences in police reports and court dossiers: A case-file study’ (2006) 19 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 374.

38 E Harrell ‘Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009-2011’ (2012) Center for Victim Research.

39 D Sobsey & T Doe ‘Patterns of sexual abuse and assault’ (1991) 9 Sexuality and Disability 243.

40 JM Maher, C Spivakovsky, J McCulloch et al ‘Women, disability and violence: Barriers to accessing justice: Final report’ Anrows Horizons 2018.

41 I Grobbelaar-du Plessis ‘African women with disabilities: The victims of multi-layered discrimination’ (2007) 22 South Africa Public Law 405.

42 L Middleton ‘Corrective rape: Fighting a South African scourge’ (8 March 2011) Time.

43 K Ericson, N Perlman & B Isaacs ‘Witness competency, communication issues and people with developmental disabilities’ (1994) 22 Developmental Disabilities Bulletin 101.

44 DN Bryen & J Bornman Stop Violence Against People with Disabilities! An International Resource (2014).

45 Powers et al (note 30 above).

46 JR Petersilia ‘Crime victims with developmental disabilities: A review essay’ (2001) 28 Criminal Justice and Behaviour 655.

47 Hughes et al (note 29 above).

48 D Wubs, L Batstra & HWE Grietens ‘Speaking with and without words: An analysis of foster children’s expressions and behaviours that are suggestive of prior sexual abuse’ (2018) 27 Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 70.

49 R Vergunst ‘Access to health care for persons with disabilities in rural Madwaleni, Eastern Cape, South Africa’ (2016) doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University.

50 Åker & Johnson (note 25 above).

51 T Beckene, R Forrester-Jones & GH Murphy ‘Experiences of going to court: Witnesses with intellectual disabilities and their carers speak up’ (2017) 31 Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 1.

52 Martin et al (note 27 above).

53 Maher et al (note 40 above).

54 E Viljoen, J Bornman & K Tönsing ‘Interacting with persons with disability: South African police officers’ knowledge, experience and perceived competence’ (2021) 15 Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 965.

55 SJ Modell & S Mak ‘A preliminary assessment of police officers’ knowledge and perceptions of persons with disabilities’ (2008) 46 Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 183.

56 J Keilty & G Connelly ‘Making a statement: An exploratory study of barriers facing women with an intellectual disability when making a statement about sexual assault to police’ (2001) 16 Disability and Society 273.

57 Bornman (note 2 above).

58 NA Spaan & HL Kaal ‘Victims with mild intellectual disabilities in the criminal justice system’ (2019) 19 Journal of Social Work 60.

59 White et al (note 8 above).

60 Keilty & Connelly (note 56 above).

61 J Dugard & K Drage ‘To whom do the people take their issues? The contribution of community-based paralegals to access to justice in South Africa’ (2013) Justice and Development working paper series 21.

62 N Groce, M Kett, R Lang & JF Trani ‘Disability and poverty: The need for a more nuanced understanding of implications for development policy and practice’ (2011) 32 Third World Quarterly 1493; X Hunt, C Laurenzi, S Skeen et al ‘Family disability, poverty and parenting stress: Analysis of a cross-sectional study in Kenya’ (2021) 10 African Journal of Disability (Online) 1.

63 South African Government ‘Disability Grant’.

64 Dugard & Drage (note 61 above).

65 NA Spaan & HL Kaal (note 58 above).

66 L Henry, A Riley, J Perry & L Crane ‘Perceived credibility and eyewitness testimony of children with intellectual disabilities’ (2011) 55 Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 385.

67 Keilty & Connelly (note 56 above).

68 Åker & Johnson (note 25 above).

69 S v Elvin Davids (RC61/2017).