ABSTRACT

While many studies dealing with the problem of militarised refugees analyse when and how militarised refugees lead to a diffusion of violence, it is unclear what conditions contribute to the avoidance of it. The present paper tackles this issue by linking securitisation theory to research on militarised refugees and war diffusion and thus offers new insights into the conditions of prevention of conflict diffusion. Specifically, it compares the two cases of former Zaire (now DR Congo) and Tanzania. Both countries faced an influx of refugees and refugee militarisation following the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 and the civil war in Burundi in the 1990s, though their outcomes varied in terms of regional war diffusion. The article suggests that while certain security strategies such as closure of borders and the repatriation and expulsion of refugees might be successful in preventing conflict diffusion, they often include a breach of international refugee law when preventing bona fide refugees from entering the country. Hence, communicating and cooperating with peaceful members of the refugee communities and confronting those suspected of being responsible for the violence are necessary steps to deal with this issue.

Introduction

War and large-scale violence lead vast numbers of people to seek shelter in more peaceful areas away from conflict zones. When the situation in the conflict country becomes too dangerous for people to stay, they cross borders into neighbouring countries and, as refugees, seek shelter away from the battle site. Upon arriving at border villages, they look for sanctuary, food, housing, and medication. International organisations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Doctors without Borders try to bring some remedy by providing refugees with tents, medical aid, and food. Until the violent situation in the country of origin is under control, refugees are allowed to stay in the host country.

But refugee flows are more than the mere result of war. They can also be the source of massive instability in the countries that border the conflict state. Overwhelming numbers of refugees destabilise local communities and are an enormous economic and social burden. Sometimes they are part of the conflict dynamics and play an important role in the regional diffusion of civil war. ‘Refugee warriors’ (Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo Citation1989) are those fighters hiding amongst refugees and eventually fight against their country of origin to achieve political goals, such as the capture of political power, the overthrow of the ruling regime, or secession (Mogire Citation2011, 29). Former research shows fighters hiding amongst refugees benefit from humanitarian aid (cf. Lischer Citation2003, Citation2005; Mogire Citation2006; Salehyan Citation2007; Stedman and Tanner Citation2003; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo Citation1989, 275ff.). ‘Militarised refugees’ can thus represent a significant threat to the security in conflict-affected regions – for bona fide refugees themselves as well as for the stability in the host countries. They relocate the conflict dynamics to another country, thus exacerbating conflict resolution and contributing to the regionalisation of war (cf. Ansorg Citation2014). Sometimes, countries of origin intervene in the host countries to halt the ongoing activities of rebel groups, which lead to even more insecurity in the whole region.

While refugee militarisation is an increasingly common phenomenon, recent cases show that it is still unknown what strategies can be adopted to avoid a diffusion of civil war in instances of refugee militarisation. There are only few mostly policy-driven and atheoretical approaches to the issue (cf. Jacobsen Citation1999) that cannot theoretically explain why diffusion of civil war occurs in one conflict and not in another.

This paper seeks to address this question. By linking the securitisation theory of Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde (Citation1998) to regional conflict situations and the research on refugee militarisation, it provides new insights into strategies of prevention of civil war diffusion and potentials and pitfalls of these. It argues that while a country’s elites can declare refugees as a security issue in regional discourse, certain national, regional, and international actors can contain this problem by adopting different security strategies. Regional security elites can contain regional insecurity as a cause of civil war diffusion by their speech acts and subsequent actions.

This theoretical argument will be comparatively tested against two cases of massive refugee influx and refugee militarisation in the Great Lakes region: former Zaire (today known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Tanzania. After the outbreak of violence in Burundi in 1993 and the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, hundreds of thousands of refugees crossed the borders into the neighbouring states. Among these refugees were also those responsible for violence in the first place: Hutu genocidaires from Rwanda, fearing revenge from the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie–Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (CNDD-FDD) rebels from Burundi. But while the militarisation of refugee camps in Zaire led to the diffusion of war and the development of a regional conflict system, Tanzania managed to stay relatively peaceful and prevented an intervention from neighbouring Rwanda and Burundi. Hence, these two cases provide an excellent starting point for a structured and focused comparison with a most similar systems design (George and Bennett Citation2005, 67). The two cases face similar levels of regional insecurity and experienced a similar influx of refugees after conflicts in neighbouring countries. However, they differed with regard to their policies towards militarised refugees, resulting out of different political context conditions. By comparing these two cases, this paper shows how securitisation strategies targeting the issue of militarised refugees can prevent the regional diffusion of violence. Information for these case studies was obtained mainly by primary and secondary sources collected during a field trip to the region in 2010, as well as interviews with experts from international and non-state organisations, refugee experts from both countries and government representatives.

The comparison of the two cases also shows, however, that a harsh security strategy towards insecurity in refugee camps does not come without problems: Despite successfully averting further politicisation and militarisation of refugees, it may prevent bona fide refugees from entering the country and, in some cases, even see bona fide refugees expelled from a country. The article thus suggest that states should refrain from adopting security strategies that target all refugees indiscriminately, and instead look to integrate peaceful members of the local refugee communities in a process of communication in order to solve the problem together with them.

The paper proceeds as follows: The next section presents the main theoretical framework that is applied to the case studies. The third section analyses the two cases of refugee inflows and militarised refugees in Zaire and Tanzania. The last section concludes with avenues for future research and recommendations for practitioners.

Theoretical background: preventing civil war diffusion

The dependent variable in this study is the (prevention of) civil war diffusion and is operationalised by (the prevention of) an outbreak of large-scale violence in a state bordering a conflict country. While many studies primarily focus on how refugees militarise and how this affects conflict diffusion, I will show that certain securitisation strategies may contain the security problem of militarised refugees and prevent the diffusion of civil war. To elaborate on this argument, the paper links securitisation theory to the literature on refugee militarisation and the debate on civil war diffusion.

In this study, security is defined in a narrow sense as protection against the threat of physical survival given that the diffusion of armed and physical conflict is of primary interest here. This threat is a military one and concerns not only the national level (which conventional studies on security tend to focus on) but also the regional level. When it comes to civil war diffusion, the physical survival of a state or nation is in danger due to a regional threat – namely, the armed conflict in a neighbouring state and its consequences (e.g. refugees and transborder rebel groups).

In securitisation theory, security is seen as an inter-subjective, deliberative process and is thus socially constructed. Securitisation is a mixture of both objective security issues (there is an actual threat) and subjective security issues (there is a perceived threat) (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 30). According to securitisation theory, something is designated as a security concern because it can be argued that it is more important than other issues. Therefore, this issue should take full priority (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 24). When analysing an act of securitisation, one should ask ‘who securitizes, on what issues (threats), for whom (referent objects), why, with what results, and under what conditions (i.e. what explains when securitization is successful)’ (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 32). Thus, there are three types of units involved in security analysis (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 36): (1) the referent object that is seen to be existentially threatened and has a legitimate claim to survival, (2) the actors who securitise issues by declaring a referent object as existentially threatened, and (3) the functional actors who significantly influence decisions in the field of security.

A securitisation actor claims to handle a security issue through extraordinary means. This justifies any breach of the ‘normal rules of the game’ as, according to this logic, exceptional circumstances require extraordinary actions. However, the speech act itself does not guarantee the securitisation of an issue, as this is only one step in a larger process. An issue is only securitised when an audience also accepts it as a security issue (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 25). Furthermore, securitisation is not created by simply breaking the rules (which may take different forms) or the mere existence of existential threats (which does not necessarily lead to securitization) (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 25). It is only created by cases of existential threats that at the same time legitimize the breaking of rules (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde Citation1998, 25).

Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde’s (Citation1998) securitisation theory is not without its critics. Olav F. Knudsen, for instance, criticises the theory’s focus on the speech act (Knudsen Citation2001). For him, (in-)security is not solely a constructed phenomenon, but is influenced by real and objective threats (Knudsen Citation2001, 360). The present paper follows this suggestion and does not only analyse the speech acts of security elites, but also the actual threats to physical security of states and groups and the actual security measures adopted by security actors. It further presents a range of different state strategies towards militarised refugees that go beyond a mere securitisation as understood by the securitisation theory.

In regard to civil war diffusion, an armed conflict in a neighbouring state and the consequences thereof (e.g. large refugee flows, militarised refugees, transborder rebel groups) pose an existential threat to the region. Security elites such as the target state’s government or military leaders will securitise the issue of conflict and its consequences by using certain rhetorical patterns in speech acts to indicate that there is a threat to the state’s or a group’s survival. In times of increased insecurity, the audience (those in the target country and also neighbouring countries) may accept this speech act and the securitisation of the issue. This can, in turn, create a fertile soil for a securitisation of the conflict issue by elites in a country – they refer to the matter in public statements and thus create an issue of national security. I refer to this process as ‘primary securitisation’. This is the first securitisation that leads to the fact that a securitisation actor claims to handle a security issue through extraordinary means, for example by an intervention in the neighbouring country.

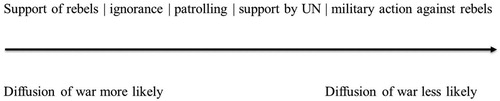

I assume that there are numerous strategies to deal with this regional security issue – all of which have major implications for regional security and the diffusion of civil war: In some cases, rebel groups are supported financially, military, or politically by receiving states. As the cases of Ugandan support to the RPF beginning of 1990s or Pakistani support to Mudjahideen in the 1980s show (cf. Muggah Citation2006; Stedman and Tanner Citation2003), this only exacerbates the situation and leads to an escalation of violence and the diffusion of the war. A second strategy is ignorance of the plea for more security in regard to militarised refugees by the host state. The conflict-affected country then may adopt countermeasures – such as an intervention on the host state’s territory from where the militarised refugees act. Intervention then sees the civil war diffuse into the neighbouring state and violence become regionalised. A third strategy is to acknowledge the security threat and increase security measure to bring the violence to a halt. These can be increased patrolling in and around the refugee camps by police or military. A screening of incoming persons already at the border to prevent combatants from entering the country is suggested by UNHCR. The screening procedures can, however, have an exacerbating effect on the situation of the refugees: Guinean border forces used this procedure to prevent bona fide refugees from entering the country. A fourth strategy would be an increased engagement by the international community in form of the UN and other bilateral donors: even if states might have the will to prevent combatants to enter the country, they might not have the capabilities to do so, as Lischer pointed out (2005, 10). Thus, the international community can address the problem of militarised refugees with sending more troops to the receiving country and helping out with resources. The UN may also implement arms embargos and sanctions against those states that support the rebel groups. However, the experience shows that especially strong states that would be capable of an increased engagement are often reluctant to do so. A fifth and more drastic strategy would be a harsh security reply to the threat of continued violence. Such measures include military action against refugees, expelling refugees from the country, or even rejecting entry into the country. In this case, security elites of the state acknowledge the existential threat and use extraordinary means to address the concern. However, with such very harsh replies – such as Guinea 1999 or Croatia 1995 – they breach the ‘normal rules of the game’ for dealing with refugees – namely, international refugee law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The extraordinary regional security threats that arise in such circumstances, however, explain the failure of host states to respect internationally and ethically accepted norms. The securitisation strategy prevents the regional diffusion of civil war, but only at the expense of bona fide refugees.

I assume that a regional diffusion of violence will only be prevented when there is a distinct reply to the threat of combatants among refugees. This may be done by increased security measures by the host states, by an increased support through the international community, as well as military action against rebels. The subsequent acts prevent a regional diffusion of violence. In those cases where there is ignorance to the primary securitisation of threatened countries or groups or where the host state even supports rebel groups financially, military, or politically, the regional diffusion is more likely: as the security actors feel threatened, they will eventually intervene in the host country to stop the ongoing violence by militarised refugees. The armed conflict thus diffuses into neighbouring states.

Securing the regional peace: Tanzania and Zaire compared

To show the implications of different securitisation strategies in relation to militarised refugees and the possibilities to prevent civil war diffusion, I compare the two cases of militarised refugees in Tanzania and Zaire after the outbreak of violence in Burundi in 1993 and the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Following George and Bennett (Citation2005, 67), this small-n comparison is systematic, structured, and focused. The generalised and objective analysing question – what strategies can be adopted to prevent a diffusion of civil war in instances of refugee militarisation – will be applied to both cases. The comparison is, however, imperfect as not all control variables can be held constant. The results will nevertheless be valuable for future research on militarised refugees and for strategies to prevent civil war diffusion.

I chose the cases of Tanzania and Zaire because they are situated in the same region and have thus faced similar levels of regional insecurity, experienced the mass influx of refugees after the conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi, have witnessed conflicts in the immediate neighbourhood, have low economic development and conflict-prone political histories, and – most importantly – have faced cases of fighters hiding amongst refugee and benefiting from humanitarian aid.

These two states, however, differed with regard to their treatment of refugee warriors: Zaire tolerated and even supported militarised refugees, whereas Tanzania replied with speech acts to the threat posed on Rwanda and Burundi and subsequently targeted combatants in refugee camps with a harsh security strategy. The two cases thus provide an excellent starting point for a most similar systems design that allows for a logical explanation of the presence or absence of the dependent variable.

After a short introduction to the history of refugee militarisation in the Great Lakes region, I will show how different securitisation strategies led to different patterns of civil war diffusion. If not stated otherwise, this part draws mainly on primary and secondary sources (e.g. official documents, statements) collected during a field trip to the region in 2010, as well as interviews with experts from international and non-state organisations, refugee experts from both countries, and government representatives.

History of refugee militarisation in the Great Lakes region

The 1990s in the Great Lakes region were characterised by massive ethnic violence in Rwanda and Burundi between Hutus and Tutsis (cf. Prunier Citation1998). In Rwanda in early 1994 militant Hutus killed over 700,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The killings were only stopped by the intervention of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Fearing revenge attacks, hundreds of thousands of Hutus fled to neighbouring countries, mainly to Zaire and Tanzania. The UNHCR estimated that 2.1 million Rwandan refugees were located in refugee camps in neighbouring countries (cf. Adelman Citation2003). In Zaire 1.5 million Rwandan refugees were situated in several different camps (Adelman Citation2003, 101). In Tanzania, about 570,000 refugees were located in camps near the border. Among the refugees in Zaire and Tanzania were also the genocidaires: members of the Forces armées rwandaises (FAR), the former Rwandan army; members of the Interahamwe, who were responsible for committing the genocide; and senior Hutu politicians who had ordered the genocide.

In Burundi – a country with a similar ethnic make-up to Rwanda – Tutsi soldiers assassinated the first-ever democratically elected president, Melchior Ndadaye (a Hutu), in June 1993. This triggered several years of violence between Burundian Hutus and Tutsis, which included massacres of Hutu civilians by Tutsi military. In 1996 Pierre Buyoya, a Tutsi, came to power through a coup d’état that was supported by the Tutsi-dominated Burundian military. Due to ongoing violence, huge numbers of people were forced to flee to neighbouring countries, particularly Zaire and Tanzania. Hiding among these refugees were Hutu-dominated rebel groups such as the CNDD-FDD. In both countries, combatants from Rwanda and Burundi were able to reorganise and benefit from the humanitarian aid provided in the refugee camps (Adelman Citation2003, 95ff.). The lack of control on the part of the Zairian government and the freedom to reorganise led to the rebels’ ongoing participation in violence against the regimes in Burundi and Rwanda. The aims of these attacks were to overthrow the regimes, return the Hutus to power, and continue the genocide of the Tutsis (Reed Citation1998, 141).

In Tanzania a similar situation emerged: Rwandan refugee camps served as a sanctuary for the Hutu militias of the FAR and Interahamwe (cf. United Nations and High Commissioner for Refugees Citation1995). They launched attacks across the border against Rwanda’s new government. Burundian refugees had an even longer history of politicisation and militarisation in Tanzania, with the rebel groups Parti pour la libération du peuple Hutu (PALIPEHUTU) and Front de Libération Nationale (FROLINA) forming on Tanzanian soil in the 1970s (Mogire Citation2011, 34). The new wave of refugees in the 1990s provided the CNDD-FDD with a safe haven in Tanzania. From there the CNDD-FDD were able to conduct military training and reorganise, which allowed them to launch attacks against Burundi from Tanzanian territory (ICG Citation1999).

Securitisation strategy in Zaire

Facing an influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees across its eastern border, the Zairian government were rather reluctant to deal with this security problem (Expert interview V). Mobutu was, together with France, one of the closest allies of the former Hutu government (see also Prunier Citation1998, 101ff.). Mobutu supported the militias not only politically but also militarily (cf. Adelman Citation2003; Reed Citation1998). Yet, Mobutu’s willingness to take in large numbers of refugees eased the international isolation Zaire faced (Expert interview VIII).

The UNHCR and other aid agencies were overwhelmed by the size of the disaster and did not react accordingly (Manahl Citation2000, 2, Expert interview VIII, Expert interview IX). They had no choice but to accept the establishment of huge refugee camps within walking distance of the Rwandan border and without screening the refugees. This was not without its problems, though, as it allowed former Hutu government and militia groups to pool and reorganise themselves. They launched regular cross-border attacks in order to destabilise the new Rwandan government (Manahl Citation2000, 2). The UNHCR tried to prevent these activities in the refugee camps by hiring members of the Zairian armed forces as police (Lischer Citation1999, 22, Expert interview VIII), which can be seen as acknowledgement of the security threat and an effort to increase security measure to bring the violence to a halt. However, this attempt backfired because the Zairian authorities started to trade with the Hutu militias rather than preventing their actions (HRW Citation1995). Despite the presence of militias in the camps, the NGOs continued their work – focusing on the humanitarian aspects rather than the political consequences – as they believed doing otherwise would have done more harm (Adelman Citation2003, 101f., Expert interview VI).

Rwandan militias were not the only active rebels based on Zairian soil and tolerated by Mobutu: at least until 1996, the CNDD-FDD was based in eastern Zaire (ICG Citation1999, 3). They not only managed to reorganise and launch attacks on Burundi, they also allied with Mobutu and the Hutu militias (Nindorera Citation2012; UN Citation1998).

There were two referent objects of regional security: (1) the states of Rwanda and Burundi, which were physically under attack by rebel groups aiming to overthrow the governments, and (2) Tutsis, who had been target for genocide by Hutu rebel groups. Soon after the start of the attacks on their country, Rwanda and Burundi demanded that the Zairian government put a stop to the violence at their borders that was being carried out by rebel groups based in and around the refugee camps. They securitised the issue in a first step. Rwanda’s president, Paul Kagame, stated in an interview: ‘We don’t envisage any point at which we shall compromise with genocidaires. If these were people with a cause, then we could find some kind of agreement. You cannot have a bunch of criminals holding a country at ransom. We shall fight them, that is the solution’ (cited in ICG Citation1999, 16). Both governments stated that they would intervene and bring an end to the insecurity if the Zairian government failed to do so.

The Rwandan and Burundian governments addressed the problem of Hutu rebel group violence in public statements and called for an end to the violence. They pointed to the security threat and made it a matter of national security – thus securitising the issue by setting it on the national agenda. By their threat to intervene in Zaire themselves if nothing was done to stop the violence, they also threatened to breach the ‘rules of the game’, which here refer to non-intervention and respecting the sovereignty of their neighbouring country. With these actions, they executed a ‘primary securitisation’ that leads to the fact that securitisation actors (Rwanda and Burundi) claim to handle a security issue through extraordinary means (by an intervention in neighbouring Zaire).

Mobutu would have had the option to put the issue on Zaire’s security agenda. He understood what the consequences of non-action would be as Rwanda and Burundi had been quite clear on the matter. Yet, he was not bothered to care about the problem, but rather searched for increasing his own benefits. He thus chose a different strategy and opted against an acknowledgement of the security problem in the refugee camps. Mobutu was not only inactive in dealing with the rebel groups operating on Zairian territory; he also supported and allied with them. Zairian troops were officially sent east to provide security in and around the refugee camps (Interview VII). But many soldiers collaborated or did business with the Rwandan militias with the approval of Mobutu (Manahl Citation2000, 2). With the help of the Zairian government the Hutu militias were able to acquire weapons from arms dealers from the UK, China, South Africa, and France (HRW Citation1995; Reed Citation1998, 138) that were used in their attacks against Rwanda and Burundi (cf. Adelman Citation2003, 104; Reed Citation1998, 137). Hence, Mobutu and the Zairian government benefited even financially from the disaster.

The international community were inactive in dealing with the ongoing violence in eastern Zaire and securitising the issue of ongoing violence at the border between Rwanda, Burundi, and Zaire (Adelman Citation2003, 115); the UN Security Council could not agree on a joint resolution. In France – which was one of the most important allies of the former Hutu government of Rwanda – the Hutu militias and the Mobutu government had an important ally in the Security Council (cf. HRW Citation1995, 3). Thus, the French government abstained from any action against the Hutu militias.

The Zairian authorities thus not only failed to securitise the issue of ongoing violence at their borders, they even cooperated with the perpetrators by providing them with arms and ammunition in violation of the arms embargo imposed by the UN Security Council (UN Citation1996). The missing securitisation of militarised refugees was highly problematic as it further escalated regional insecurity. After the Vice Governor of South Kivu, Lwabanji Ngabo, summoned to expel the local Tutsi minority from the country (Manahl Citation2000, 3), Rwanda decided to intervene in Zaire on the side of the AFDL, a Zairian opposition movement under Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a long-lasting opponent of Mobutu.

The consequences of the reaction to the ongoing violence were the diffusion of conflict from Rwanda and Burundi to Zaire and the spread of insecurity and violence throughout the whole region. In May 1997 after a seven-month military campaign, Mobutu was overthrown by the coalition of AFDL and its allies and fled the country to Morocco, where he eventually died on 7 September 1997.

Securitisation strategy in Tanzania

Facing a similar security problem, Tanzania applied a different strategy. Among the nearly 600,000 refugees from different countries that were located in the western part of Tanzania, several thousand combatants were hiding in the refugee camps and receiving humanitarian aid (Expert interview I, Expert interview II, Expert interview IV). As in Zaire, the refugees politicised and established certain government structures with leaders and chains of command (ICG Citation1999; UN Citation1995, 2, Expert interview I). In the Burundian refugee camps in Tanzania, Burundian rebel groups such as CNDD, PALIPEHUTU, and FROLINA were active (ICG Citation1999). Just as they did in Zaire, the governments of Burundi and Rwanda complained about the security threat that emanated from the border regions in Tanzania (e.g. ICG Citation1999); as a ‘primary securitisation’, they called on Tanzania to control the situation and arrest the rebel groups (Interview III). Furthermore, they threatened to intervene in the refugee camps should the Tanzanian government or the international community fail to deal with this security problem (HRW Citation1999). They thus securitised the problem and claimed to handle a security issue through the extraordinary means of an intervention.

Problematic was the Tanzanian government’s initial decision to impose sanctions on the Burundian government and support the Burundian rebel groups to bring down then president Pierre Buyoya (ICG Citation1999, 5). The difficulty in relations between the two countries increased until 1997, when cross-border shelling briefly occurred between their respective armies (HRW Citation1999, Interview III). However, the Tanzanian government publicly stated that it did not want the confrontation with Burundi to escalate and that it would thus not allow activities of Burundian rebel groups in the refugee camps (HRW Citation1999, Interview III).

Even though Tanzania also suffered from the problem of militarised refugees in the camps, the government decided to apply – after a period of denial of the security problem – another securitisation strategy, which eventually prevented the diffusion of violence.

Until the early 1990s, Tanzania followed quite liberal refugee policies in terms of the admission and administration of refugees (Mogire Citation2011, 146). However, with the masses of refugees that arrived after the outbreak of violence in Burundi in 1993 and the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, Tanzania tightened its refugee policy towards refugees, thus applying another strategy towards refugees. The sheer numbers of refugees overwhelmed not only the Tanzanian authorities but also the international aid organisations (Expert interview I, Expert interview II, Expert interview IV). Several measures were adopted by the government to prevent the diffusion of violence. First, borders were closed to limit or prevent the entry of refugees into Tanzania. During at least two years (1993 and 1995) refugees from Burundi and Rwanda were denied entry into the country. The Tanzanian government justified this by claiming that its ‘internal security’ (Interview III, Expert interview VI) – was being threatened by combatants hiding among refugees – thus distinctly securing the issue of militarised refugees over its territory.

Second, other groups of refugees – among them bona fide refugees – were for a certain period of time during the 1990s repatriated or expelled from the country (cf. Mogire Citation2011, 151) – clearly breaking international refugee law as there was still conflict and insecurity in these states (ICG Citation1999). The Tanzanian government increasingly came to see ‘voluntary’ repatriation as ‘the best solution’ (Interview III). However, government ultimatums played a role in several instances of repatriation, thus leading to international observers to question the voluntary nature thereof. According to its joint statement with the UNHCR in early December 1996, the government decided that ‘all Rwandese refugees could then return to their country in safety’ (Interview III). This statement and action clearly ignored the fact that there was still widespread insecurity in the country and that it was not safe to return. However, it clearly shows the urge of the government to further securitise the issue of militarised refugees.

Third, the Tanzanian authorities rounded up and expelled refugees who did not live in the camps but had been settled in villages for several years (ICG Citation1999, 10). Many of these Burundians were forced from their homes, separated from spouses and family, and often not even given the opportunity to collect their belongings (ICG Citation1999, 10). Again, this is a symbol of a securitisation of the issue and a clear break of international norms towards refugees.

Fourth, the Tanzanian authorities started a comprehensive strategy of control and depoliticization in the remaining refugee camps (Expert interview II). They relocated the camps away from the borders and introduced a system of separation and control to identify militarised refugees. Furthermore, police forces were assigned to the refugee camps on a full-time basis to enforce law and order and maintain the civilian nature of the camps (Crisp Citation2001; Durieux Citation2000; ICG Citation1999). The UNHCR had agreed to cover the USD 1.5 million in costs for these forces, including daily allowances and accommodation (Expert interview I). In practice, however, the police officers often lacked the time, resources, and knowledge to deal with all the kinds of rebel activities in the camps; they merely provided security on the surface (Expert interview I). Moreover, the movements of refugees were strictly controlled and eventually restricted to a four-kilometre radius from the centre of the camps.

Fifth, after 1998 the Tanzanian authorities tried to separate combatants from bona fide refugees upon their entering the country (Expert interview II). This turned out to be rather difficult in terms of practice (i.e. the actual process of distinguishing between refugees and combatants) and also due to legal reasons (Tanzania Citation1998). This measure was thus not seen as having been successful (cf. Crisp Citation2001).

The grounds for Tanzania’s change in approach and decision to implement a security strategy to deal with the threat posed at its borders are evident: Following Rwanda’s and Burundi’s intervention threats and the actions taken by the Rwandan government against Zaire, the Tanzanian government feared the diffusion of large-scale violence into its territory and the violation of its sovereignty as well. In addition, Tanzania was also interested in maintaining good relations with its neighbours.

This strategy, however, was not without problems. The closure of the borders on several occasions prevented bona fide refugees from entering the country – thus breaching a major aspect of international humanitarian law. Round-ups, expulsion, and restrictions on the freedom of movement were inhumane and disrespectful measures implemented for the sake of security. Similar problems appeared with the refoulement of refugees back to Rwanda and Burundi, where violent conflict was still prevalent. This resulted in a disastrous humanitarian situation for those who had suffered most from the armed conflicts. Furthermore, due to being stationed in the refugee camps, the police forces only addressed the problem of militarisation on-site – they did not deal with the military activities of rebel groups located outside of the camps and close to the borders (cf. Crisp Citation2001, 2). Most Tanzanian government employees, however, tend to emphasise the positive aspects of the security strategy – specifically, its prevention of an intervention by Rwanda or Burundi and the outbreak of widespread violence.

The international community was largely silent on the security strategy and the repatriation of refugees from Tanzania. There was no foreign government that objected to the inhuman treatment, the refoulment, or the round-ups experienced by refugees.

Implications for civil war diffusion and refugee policies

The analysed examples and evidence from other cases such as Sudan, Turkey, and Syria show that the militarisation of refugees is often unavoidable in cases of large-scale conflict and large inflows of refugees. Combatants sometimes hide among bona fide refugees and escape undetected to neighbouring countries. There they have a chance to reorganise under the cover of humanitarian aid. In the worst cases, they continue to participate in the ongoing attacks on the country of origin.

As the discussion in the theoretical part of the paper showed, there are different ways for a target country to deal with such a security problem. Zaire, for example, chose to ignore Rwanda’s plea to tackle the issue of militarised refugees and the threat they posed due to its close ties with the former Rwandan Hutu government. Instead, they provided the combatants with weapons and ammunition despite a UN arms embargo having been imposed on all parties involved in the Rwandan conflict. Moreover, the Zairian government allied with the Burundian rebels as it hoped for support against its internal and external opponents. This behaviour of Mobutu and the Zairian officials can be explained by Zaire’s history, which was characterised by a neopatrimonial system oriented to maintaining power (cf. Reno Citation1997). In addition, the country had not experienced a process of democratisation or an opening for a more inclusive political system. These structural conditions led to a power system that was based and continued to be dependent on long-lasting patrimonial and personal networks rather than on democratic and responsible conflict resolution. An alternative option for Mobutu and the Zairian government would have been to cooperate with Rwanda and Burundi. Instead, Mobutu chose to confront the new governments of Rwanda and Burundi due to his close relations with the former Rwandan Hutu government. The result of this was the intervention of Rwanda, together with Uganda, Angola, the AFDL, and with the political support of Burundi; this, in turn, saw the conflict spill over from Rwanda and Burundi into neighbouring Zaire.

Tanzania, on the contrary, chose to adopt a harsh security strategy that sought to contain the militarisation of refugees. The Tanzanian government also feared an intervention by its neighbours, which it wanted to avoid at any cost. It wanted to maintain its good relations with Rwanda and Burundi, even at the expense of refugees. Furthermore, at that time Tanzania had a higher state capacity than Zaire, which was evidenced, for instance, by more effective military and higher tax incomes to implement certain security policies. The security strategy included the closure of borders, the repatriation and expulsion of refugees, round-ups and expelling of refugees residing outside of refugee camps, the control and depoliticization of refugee camps, and the separation of refugees and combatants. On the one hand, this helped to avoid the widespread diffusion of the Burundian and Rwandan conflict into Tanzania. In large part this was because the Tanzanian government acknowledged the security problem identified by the Burundian and Rwandan governments and took action against it. On the other hand, in attempting to contain the problem of militarised refugees, the harsh security strategy breached the ‘rules of the game’ (i.e. international refugee law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) by preventing bona fide refugees from entering the country and staying in safe refugee camps. They were also subject to repatriation, expulsion, and round-ups. Thus, one of the key principles of refugee and humanitarian law, ‘the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution’ (“The Universal Declaration of Human Rights” Citation1948 Article 14(1)), was violated by Tanzania’s security strategy.

After analysing the two cases of Zaire and Tanzania in the light of the wide range of possible strategies towards the threat of a militarisation of refugee camps, I generally agree with the four suggestions of Karen Jacobsen’s ‘safety-first approach’ (1999). Naturally, it helps to disarm and demobilise refugees, to maintain camps as non-militarised and weapons-free zones, to locate camps at a safe distance from the border, and to create and maintain a climate of law and order. I will, however, add the recommendation the communication with refugee communities, and in particular with representatives of bona-fide refugees, which is unavoidable in the case of an incidence of militarisation within the camps. As the case of Tanzania shows, the treatment of all refugees as potential combatants does not help to maintain a humanitarian atmosphere, but rather creates a climate of fear and reluctance. Officials of the target states instead need to communicate the problem to peaceful political leaders within the refugee community and to find a solution together with them, not only for them – which can be done in joint meetings, committees, or negotiations. Furthermore, it is necessary to constantly provide refugees with information. As some of the interviews showed, the confusion associated with the aftermath of conflict means that refugees often do not know what is going on inside or outside of refugee camps. Thus, they do not understand why they are the targets of such harsh security strategies. Local authorities thus need to provide information on the security situation as well as the consequences for ongoing participation in the conflict. Lastly, in the case of militarised refugees, those allegedly responsible for politicisation and militarisation should be confronted with the accusations and provided with an opportunity ‘to submit evidence to clear’ themselves (“Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees” Citation1958, 32(2)). Refugees do not politicise without reason; often they feel they need to do something in response to a current situation. It is therefore helpful to understand and discuss with them their motives and fears.

In regard to the theory, the paper shows that the securitisation theory cannot only be applied to states, but also to regional situations of insecurity. The approach can be thus linked to theories of civil war diffusion: militarised refugees may pose an existential threat to the region. Regional security elites will securitise the issue of conflict and its consequences by using certain rhetorical patterns in speech acts to indicate that there is a threat to the state’s or a group’s survival. Security elites of the target states have different choices: A regional diffusion of violence will be prevented when there is a distinct reply to the threat of combatants among refugees and the primary securitisation. The subsequent acts prevent a regional diffusion of violence. In those cases where there is ignorance to the primary securitisation of threatened countries or groups, the regional diffusion is more likely: as the security actors feel threatened, they will eventually intervene in the host country to stop the ongoing violence by militarised refugees. The armed conflict thus diffuses into neighbouring states.

Conclusion

This paper dealt with the question of what strategies can be adopted to avoid the diffusion of civil war in cases of refugee militarisation. It addressed this question by linking Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde’s (Citation1998) securitisation theory to research on refugee militarisation and subsequent regional diffusions of civil war. The paper stated that civil war diffusion can be contained by security strategies implemented by actors (and their subsequent actions) as a reaction to the securitisation of militarised refugees.

This argument was comparatively tested against two cases of large-scale refugee influx and refugee militarisation in the Great Lakes region. In Zaire, the government refused to contain the security problem of militarised refugees, but instead cooperated with the combatants. The result was an intervention by neighbouring countries and the diffusion of war. In contrast, the Tanzanian government acknowledged the threat the militarised refugees posed to Rwanda and Burundi and implemented a comprehensive security strategy to contain the problem. Tanzania hence successfully avoided a diffusion of civil war onto its territory. This strategy did not, however, come without problems: Despite successfully averting further politicisation and militarisation of refugees, it prevented bona fide refugees from entering the country and, in some cases, even saw bona fide refugees expelled from Tanzania. Therefore, target states should refrain from adopting security strategies that target all refugees, and instead look to integrate peaceful members of the local refugee communities in a process of communication in order to solve the problem together with them, and not for them.

Future research lies in the application of the theory towards other cases of militarised refugees that lie outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, comparative approaches to the securitisation of militarised refugees may reveal more detailed patterns of security acts and produce more detailed results on how a diffusion of violence by militarised refugees can be prevented.

List of interviews

- Expert interview I, Country officer Tanzania, UNHCR, 17 August 2010.

- Expert interview II, Country officer, UNHCR, Tanzania, 19 August 2010.

- Interview III, Government spokesperson, Tanzania, 20 August 2010.

- Expert interview IV, UNDP, Tanzania, UNDP, Tanzania, 23 August 2010.

- Expert interview V, UNDP, DR Congo, 30 August 2010.

- Expert interview VI, Care, DR Congo, 31 August 2010.

- Interview VII, Government spokesperson, DR Congo, 1 September 2010.

- Expert interview VIII, Country officer, UNHCR, DR Congo, 6 September 2010.

- Expert interview IX, Country officer, Oxfam, DR Congo, 13 September 2010.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on the contributor

Nadine Ansorg, PhD, Freie University Berlin (2013) is a Senior lecturer in International Conflict Analysis, University of Kent, and a research associate at the GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies. Her current research interests focus on institutional reforms in post-conflict countries, security sector reform, and UN peacekeeping.

References

- Adelman, Howard. 2003. “The Use and Abuse of Refugees in Zaire.” In Refugee Manipulation. War, Politics, and the Abuse of Human Suffering, edited by Stephen John Stedman and Fred Tanner, 95–134. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- Ansorg, Nadine. 2014. “Wars without Borders: Conditions for the Development of Regional Conflict Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Area Studies Review 17 (3): 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865914546502.

- Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde. 1998. Security. A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.” 1958. UNHCR. 1958. http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html.

- Crisp, Jeff. 2001. “Lessons Learned from the Implementation of the Tanzania Security Package.” EPAU/2001/05 May 2001. Geneva: Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Durieux, Jean-François. 2000. “Preserving the Civilian Character of Refugee Camps.” Track Two 9 (3).

- George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- HRW. 1995. “Rwanda/Zaire. Rearming with Impunity. International Support for the Perpetrators of the Rwandan Genocide.” New York: Human Rights Watch.

- HRW. 1999. “Tanzania: In the Name of Security. Forced Round-Ups of Refugees in Tanzania.” Vol. 11, No. 4. New York: Human Rights Watch. http://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/tanzania/.

- ICG. 1999. “Burundian Refugees in Tanzania: The Key Factor to the Burundi Peace Process.” Africa Report N° 12. ICG Nairobi. http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=1661&l=1 (15 March 2010).

- Jacobsen, Karen. 1999. “A ‘Safety-First’ Approach to Physical Protection in Refugee Camps.” Working Paper #4. The Rosemarie Rogers Working Paper Series. Cambridge: Inter-University Committee on International Migration.

- Knudsen, Olav F. 2001. “Post-Copenhagen Security Studies: Desecuritizing Securitization.” Security Dialogue 32 (3): 355–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010601032003007.

- Lischer, Sarah Kenyon. 1999. “Militarized Refugee Populations: Humanitarian Challenges in the Former Yugoslavia.” The Rosemarie Rogers Working Paper Series Volume|.

- Lischer. 2003. “Collateral Damage: Humanitarian Assistance as a Cause of Conflict.” International Security 28 (1): 79–109.

- Lischer. 2005. Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Camps, Civil War, and the Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- Manahl, Christian R. 2000. “From Genocide to Regional War: The Breakdown of International Order in Central Africa.” African Studies Quarterly 4 (1): 17–28.

- Mogire, Edward O. 2006. “Preventing or Abetting: Refugee Militarization in Tanzania.” In No Refuge: The Crisis of Refugee Militarization in Africa. London: Zed Books.

- Mogire. 2011. Victims as Security Threats: Refugee Impact on Host State Security in Africa. Global Security in a Changing World. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Muggah, Robert. 2006. No Refuge: The Crisis of Refugee Militarization in Africa. London, New York: Zed Books, in association with Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC) and Small Arms Survey.

- Nindorera, Willy. 2012. The CNDD-FDD in Burundi: The Path from Armed to Political Struggle. Berlin: Berghof Foundation.

- Prunier, Gérard. 1998. The Rwanda Crisis. History of a Genocide. London: Hurst & Company.

- Reed, William Cyrus. 1998. “Guerillas in the Midst.” In African Guerillas, edited by Christopher Clapham, 135–54. Oxford, Kampala, Bloomington & Indianapolis: James Curry, Fountain Publishers, Indiana University Press.

- Reno, William. 1997. “Sovereignty and Personal Rule in Zaire.” African Studies Quarterly 1 (3).

- Salehyan, Idean. 2007. “Transnational Rebels. Neighboring States as Sanctuary for Rebel Groups.” World Politics 59: 217–42.

- Stedman, Stephen John, and Fred Tanner. 2003. Refugee Manipulation. War, Politics, and the Abuse of Human Suffering. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- Tanzania. 1998. The Refugees Act, 1998. Dar es Salaam: Government of Tanzania.

- “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” 1948. 1948. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/.

- UN. 1995. “Second Report of the Secretary-General on Security in the Rwandese Refugee Camps.” New York: United Nations Security Council.

- UN. 1996. “Report of the International Commission of Inquiry (Rwanda).” Report of the Secretary General to the United Nations Security Council S/1996/195. New York: United Nations.

- UN. 1998. “Report of the Secretary-General’s Investigative Team Charged with Investigating Serious Violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” New York: United Nations Security Council.

- United Nations, and High Commissioner for Refugees. 1995. In Search of Solutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zolberg, Aristide R., Astri Suhrke, and Sergio Aguayo. 1989. Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World. New York: Oxford University Press.