ABSTRACT

In this article, complexities in the relationship between academic mobility and freedom evident in Africa showing high levels of mobility but frustrations with the realisation of academic freedom are discussed. A distinction between negative, positive and epistemic dimensions of freedom helps us to analyse conditions for academic mobility but also how mobility can compromise freedom. Semi-structured interviews of scholars of social and political sciences at the main national universities in Botswana, Cameroon and Zimbabwe, representing different experiences of political developments, show that international connections allowing academics to move are crucial for their work and enable them to be critical, but do not guarantee decent working conditions or support for decolonisation of the curricula. Lack of connections increase self-censorship. Yet the situation of non-national academics can be particularly vulnerable. The space available for critical expertise is not only affected by national politics and material conditions of universities, but also by the internationalisation of higher education and research. That is why all dimensions of academic freedom should be protected within international co-operation.

Introduction

Academic mobility is important for the progress of science and spreading of knowledge. Researchers and students need to exchange views with colleagues from other institutes, including those abroad, and learn from them. Sharing data and critical infrastructure facilitates new innovations, not to speak of the importance of disseminating research results among members of the academic community all over the world. UNESCO’s recommendations on the Status of Higher-Education Teaching Personnel from the year 1997 stipulates that teachers ‘should be enabled throughout their careers to participate in international gatherings on higher education or research, [and] to travel abroad without political restrictions’ (Paragraph 13; quoted in Beiter Citation2014). In practice, however, examples of restrictions of scholars’ free travel are plenty starting from visa and passport practices to denying research permits and expelling foreign scholars (Beiter Citation2014).

Academic mobility is compatible with academic freedom. Yet the interdependence between the two is not an unambiguous one. This is particularly evident in Africa showing high levels of academic mobility but also frustrations with regard to the realisation of academic freedom that resonate with incomplete democratic transitions and authoritarianism. In the context of a rapid growth of the higher education sector in Africa, both in terms of the numbers of the institutions and students, as well as the research output, these issues clearly are pertinent. About 6 per cent of African enrolled university students go outside their country of origin. With the growth of young populations, this share is likely to grow (Kritz Citation2015).

Mobility and freedom have a direct impact on the quality of higher education and research, and in this way also on democratic rule in terms of the capacity of African societies to produce and utilise evidence-based knowledge in decision-making and policies. The question is not only about the responsibility of academics ‘to speak the truth to power’ (Said Citation1994, 97) and the acknowledgement of academic knowledge that as such is crucial for the competence of regimes, but also about the necessity of international contacts for that knowledge.

The aim of this article is to clarify the dynamics between academic mobility and freedom and their conditions in Africa. While the issue of academic freedom has been discussed and also empirically studied in various African countries and comparative data on academic mobility is also available, the relationship between them has not been under detailed analysis. I will approach this relationship from a cultural studies perspective by analysing the perceptions and experiences of scholars of social and political sciences in Botswana, Cameroon and Zimbabwe, as their political developments and academic environments differ, but scholars are mobile in all of them. Social and political sciences are chosen as these directly relate to political freedoms.

Before a description of the different contexts of academic life in the three countries and an analysis of the views and experiences of scholars on international mobility, I will give an overview of the approaches to academic mobility and academic freedom in earlier literature. The final part of this article will discuss the role of international mobility in the strategies of scholars working in different political environments.

Approaches to academic mobility

While academics have always travelled, the concept of academic mobility usually refers to a limited time during which university students, teachers and researchers work or study abroad. Academic mobility, thus, is distinguished from migration (Dervin Citation2011), although in practice academic migration is increasingly circular, involving return from a host country to a country of origin or moving to a third country. However, in all of its different forms, mobility has increased and so have its economic and cultural impacts. Much of the existing studies concentrate on the economic effects, efficiency of exchange programmes and their use as instruments of imperial soft power as well as integration of foreign scholars to local communities. But there is also research focusing more on epistemological issues such as the links between knowledge and mobility (Fahey and Kenway Citation2010) and the transformative power of university education across societies (Hoffman Citation2009, 349). Scholarship programmes have been considered as a specific object of interest: ‘how scholarships shaped career paths, disciplines, institutions and national cultures, and how they have in turn been shaped by them’ (Tournès and Scott-Smith Citation2017, 5). Instead of brain drain and gain in the framework of national economies, Terri Kim, for instance, has examined the issue as ‘brain transfer and transformation’ within globalisation (Kim Citation2009, 401). ‘Brain transfer and transformation’ helps understand how universities ranked as the best within global competition become models of exporting and attracting transnational academics, when other universities try to adapt to the norms and paradigms of ‘the best’ (Kim Citation2010, 588). And vice versa, it also helps understand why academic immobility appears to be a problem. Those who do not adapt to the norm of international recruitment are accused of ‘inbreeding’ (Altbach, Yudkevich, and Rumbley Citation2015, 3–4).

Most of the existing research is about intra-European mobility or about North America as a target region (Altbach Citation2004). The mobility of African academics is mainly approached from the economic perspective of brain drain, that is, African academics leaving the continent, or as a consequence of the deficiencies of African higher education such as a lack of adequate infrastructure (Oucho Citation2008; Teferra Citation2000, 70–72; Smallwood and Maliyamkono Citation1996). Epistemologically, however, the consequences of African academic mobility are far reaching. The history is long and the volumes exceptionally high. Colonialism and colonial heritage tie African education systems and universities to those of the old colonial powers. One very practical factor relates to linguistics: mobility has followed and been enabled by the distinctive cultural connectivities of Francophone, Anglophone and Lusophone Africa (Woldegiorgis and Doevenspeck Citation2015, 108–109). Of course, such ties have provided significant opportunities for individual African scientists and intellectuals to become influential in their disciplinary fields. Coming from English-speaking Africa and being fluent in English, for instance, has been an asset for many African academics in their careers (see Hurst Citation2014).

These same connectivities, however, are also a manifestation of colonial power relations in the African academic life. As noted by Mahmood Mamdani (Citation2019, 16), the mere fact that discipline-based universities were created during colonialism roots the form and content of the disciplines and disciplinary boundaries, including those of social and political sciences, to colonial dominance. Long after independence, a remarkable part of the teaching staff in African universities came from the ex-colonial powers Britain and France, or at least had their doctoral degrees from there or elsewhere from the West. The role of Western research foundations, like the Fulbright programme of the United States, has been significant in contributing to the capacity of African Universities. Britain had specific ‘study and serve’ programmes combining researcher’s field work with teaching at African universities (McKay Citation1968, 1), so that already in the 1960s critics claimed that the ‘inundation’ of foreigners frustrated the attempts of local scholars to enter academia (McKay Citation1968, 1; Tettey and Puplampu Citation2000, 92). Colonial connectivity, thus, has also been a hindrance for Africans to pursue academic careers. Academic mobility can exacerbate global inequalities and hierarchical positions of nation-states, evident for instance in the various university rankings renewing the dominance of the West in higher education (Bilecen and Van Mol Citation2017; Börjesson Citation2017, 1262). And indeed, dependency on the education and knowledge produced in the West has been a major source of the calls for decolonisation of universities in Africa (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2015).

The hegemonic position of the West is challenged, however. Already within the Cold War rivalry the Soviet bloc became an important destination for African students. For example, the Lumumba University, established in Moscow in 1960, was a prominent attempt to foster socialist unity in the Third World (Katsakioris Citation2019). Since 2000 the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has put increasing emphasis on academic exchange. Substantial changes have occurred also in intra-African mobility, its expansion and even more importantly its recognition (Knight and Woldegiorgis Citation2017, 113–114). New policies like the African Union Intra-Africa Academic Mobility Scheme, underlining ‘the strong potential of academic mobility to improve the quality of higher education’ (African Union Citation2018, 4), are obvious incentives for it, but mobility is also spurred by the huge differences in the investments in higher education and research between African countries. While the average number of researchers per one million inhabitants in Sub-Saharan Africa is only 91, South Africa has reached the level of 500 researchers per one million, and Tunisia has 2000 (UNESCO Institute for Statistics Citation2020a).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics data shows high levels of student mobility in the three countries discussed in this article. In 2020 about 20,000 Zimbabwean university students, 13 per cent of the total, were studying abroad. More than half of them were in South Africa. The United States, Australia, United Kingdom, Canada and Malaysia appeared to be the most popular destinations outside of Africa. The number of incoming students, mainly from Zimbabwe’s neighbouring countries, was only 600.

Cameroon was sending abroad 26,000 students, 9 per cent of the total, mostly to Germany and France. Other popular countries were Italy, Belgium, the United States and Canada, but also Tunisia and South Africa. The number of hosted students was 4000 from the neighbouring countries, like Chad. The number of Botswana’s university students abroad was 2500, 5 per cent of the total. They were mainly going to South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Canada. The number of incoming students was relatively high, too, 1200, the biggest group being Zimbabweans, but there were also students from other African countries, the United States, India and Bangladesh (UNESCO Institute for Statistics Citation2020b).

While these trends are well documented and also analysed in the literature, we know very little about the impact of mobility on the work and careers of African scholars. Critical, in this respect, are the conditions of academic freedom, both as an enabling factor of mobility and, when restricted, as instigating it.

Why is academic freedom important?

In 1990, the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, CODESRIA, and Africa Watch organised a symposium on academic freedom and social responsibility, resulting in the ‘Kampala Declaration on Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility’. The declaration stated:

Every African intellectual shall enjoy the freedom of movement within his or her country and freedom to travel outside and re-enter the country without let, hindrance or harassment. No administrative or any other action shall directly or indirectly restrict this freedom on account of a person’s intellectual opinions beliefs or activity. (Citation1990, Article 4)

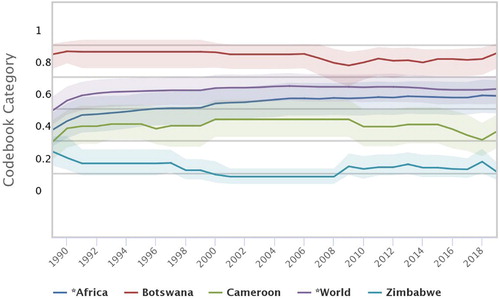

It is not a coincidence that this was presented at a time of intensifying popular protests demanding democratic opening all over Africa. Evidence shows that the ability of scholars to participate in political discussions has contributed to the consolidation of democracy in Africa (Kratou and Laakso Citation2020). According to longitudinal worldwide Academic freedom index of the Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem) that combines expert survey indications of its different dimensions (Spannagel, Kinzelbach, and Saliba Citation2020), the level of academic freedom in Africa has continuously improved between 1989 and 2019 although it was still below the world average. The improvement has not been uniform, however. Of the case studies selected for this article, the performance of Botswana has remained above the average, Cameroon, below the average, has improved, while Zimbabwe, also below the average, has become worse. None of these countries show linear or completely stable development ().

Figure 1. Academic freedom trends.

Coppedge et al. (Citation2020).

Also, a survey by Kwadwo Appiagyei-Atua, Klaus D. Beiter and Terence Karran of the legal protection of academic freedom in African universities confirms disparities between African countries. They ranked 44 countries for which sufficient data was available. Eritrea received the lowest score, and South Africa, Cape Verde and Ghana the highest. The ranking of this study’s three case countries appeared reversed to that of the V-Dem rankings. Zimbabwe in the category of ‘partly free’ was in the better half of the African countries, while Cameroon and Botswana as ‘not free’, in this order, scored below the average (Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter, and Karran Citation2016, 19–20).

Zimbabwe’s good performance stems from the fact that academic freedom is recognised in its constitution and the autonomy of public universities is respected also in the composition of their governing bodies like the university senates. Furthermore tenure, the right to work, is fully respected in public universities, although the individual rights and freedoms in teaching and research were not mentioned in the legislation or university statutes. What makes the institutional autonomy of universities in Zimbabwe qualified, is the President’s position as the Chancellor of all public universities and powers to appoint the Vice-chancellors (Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter, and Karran Citation2016, 6, 9, 12–14).

Also, in Cameroon the President directly appoints Rectors, Vice-Rectors and Board Chairmen in the Francophone universities and Vice-Chancellors and Pro-Chancellors in the Anglophone universities. Unlike in Zimbabwe, academic freedom has not been recognised in the constitution and self-governance and collegiality, that is the representation of the university community in the governing bodies, is restricted. However, tenureship is fully respected as well as individual rights and freedoms in teaching and research (Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter, and Karran Citation2016, 6, 9, 12–14).

Until 2008 and amendment of the University of Botswana Act, the President of Botswana, too, was the Chancellor. Since then the President has appointed the Chancellor. The University Act in Botswana grants autonomy in terms of the composition of the Senate at the University of Botswana. Academic freedom is also respected with regard to the protection of tenure, but unlike in Zimbabwe, not where the explicit rights and freedoms of individual scholars to do research and to teach are concerned (Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter, and Karran Citation2016, 6–9, 12–14.)

The legal framework of university autonomy, of course, defines only one aspect of academic freedom. It relates to what Isaiah Berlin identified as the negative dimension of academic freedom (Berlin Citation1969): the absence of constraint on choices, such as censorship, and non-interference in the design of the curriculum, content of teaching and research and the scholars’ freedom to take part in public discussions. The legal and formal setting, in fact, is meaningless if there are no enabling mechanisms that facilitate choices. This positive dimension of academic freedom includes not only availability of research grants and proper infrastructure like internet access and adequate library services, but also certain privileges in the form of protection and respect of scientific knowledge, without which the views of experts would have no more value for decision making and society at large than non-expert ones.

It goes without saying that state authorities, together with external funders, bear the main responsibility of this positive dimension, too. Most important in this regard are the universities’ financial resources, which can be used also for academic mobility. The conditions set by the state and other stakeholders and the actual liberties of the scholars are mediated by university management, which is influenced also by ‘global educational environment characterised by universalistic standards and cross-national rankings’ (Ramirez and Christensen Citation2013, 696). Stensaker et al. in their study of differently ranked universities all over the world, found striking similarities in their strategies, including the emphasis given to international collaboration. But unlike the top, highly ranked universities that tend to celebrate their global reputation and reach, the medium-low-ranked and unranked universities, including African institutes of higher education, pay attention to international networks, mobility and opportunities to share infrastructure in their international cooperation (Stensaker et al. Citation2019, 552, 555–556).

Jannis Grimm and Ilyas Saliba note that the different aspects of academic freedom in the literature, their interdependency and difficulties defining it unambiguously should not hinder its recognition ‘as a normative value and right on its own’ (Grimm and Saliba Citation2017, 48). Therefore, it should also be pertinent to regard epistemic freedom as a dimension of academic freedom. Even though Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni in his ground-breaking work on epistemic freedom explicitly differentiates these two by defining academic freedom merely as university autonomy and freedom of expression whereas epistemic freedom according to him ‘draws our attention to the content of what it is that we are free to express and on whose terms … overrepresentation of Eurocentric thought in knowledge, social theory and education’ (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2018, 4). As the views of the scholars interviewed for this study below demonstrate, eurocentrism and lack of opportunities to decolonise the content of education were seen as restrictions to academic freedom.

Irrespective of their explicit categorisations, these different dimensions conditioning academic freedom are pivotal for international mobility and its role in the academic life in Africa. The experiences of African scholars show how these conditions are met, how international mobility is valued and how they navigate in the global and national environments.

Context of the three cases

Botswana, Cameroon and Zimbabwe provide suitable environments to investigate the various ways in which mobility may support or compromise academic freedom in a context where this freedom is or can be restricted. As became evident above, all of them show high levels of student mobility, but the directions of this mobility differ. They differ in terms of academic freedom, but not in an unambiguous way. Most importantly all are exemplary cases of two key features in African politics: strong executive and a dominant party system, even though their political developments have diverged. In all these countries the powers of the president and the ruling party extend to the whole public sector, including the university. It is thus the political developments that can be assumed to affect the conditions of their academic life and so also the role of mobility for individual scholars.

Botswana

Botswana has been politically one of the most stable democracies in Africa. In spite of a dominance of the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), the opposition has been free to mobilise and participate in political life also in the university campuses. But as its economy is highly dependent on diamond mining with substantial state ownership in it, there are only a few other ways to accumulate wealth than the state (Tsie Citation1996; Mogalakwe and Nyamnjoh Citation2017). The power of the government thus extends deep into all sectors of the society including research and higher education. One of the main aims of the government has been to diversify its economy through education and research. Thus, the University of Botswana claims to be a world-class institution with a specific internationalisation policy to expand international exchange programmes and research cooperation and to internationalise all curricula (University of Botswana Citation2020). And indeed, virtually all teachers in senior positions have undertaken parts of their degrees or careers abroad. The University also has several non-national staff among its teaching staff.

In 2005 Botswana’s reputation as a tolerant democracy was tarnished as the President ordered Professor Kenneth Good, a University of Botswana political science professor, and Australian citizen, to leave the country without any official reason. Good had written a scholarly article on the presidential succession in the ruling party, criticising the government’s decision to evict the country’s indigenous population from a conservation park rumoured to contain diamond deposits, the lifeline of the state (Good and Taylor Citation2006). The case was taken to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which in 2010 found that the government had violated the African Charter for freedom of expression (Good Citation2017, 113; Beiter Citation2014).

Cameroon

Like Botswana, Cameroon has also been ruled by one party throughout its independence, currently named as the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM), but the political competition has become increasingly tense. Public protests followed the re-election of its longstanding President Paul Biya in 2018, and the government responded by detaining opposition leaders, academics among them. Armed conflict in the Anglophone regions of the country has exacerbated the restriction of civil liberties also affecting universities. In 2017 Stony Brook University Professor Patrice Nganang, who has dual Cameroon and United States citizenship, was arrested and then deported from the country after he wrote an article criticising the government for its policies in the Anglophone crisis (Nganang Citation2017). Additionally, the President’s decision in 2017 to shut down the main Anglophone universities, Bamenda and Buea, and replace the Rector of the University of Yaoundé II, have been seen as attempts to silence the pro Anglophone voices in the universities (Fatunde Citation2017). Most of the university leaders in Cameroon have also made their career in high positions in the government, in the ministries or as advisors to the President. The connection between the academia and government is very close.

The university system in Cameroon, like the whole country, follows the division between Francophone and Anglophone heritage. Universities of Yaoundé I and Yaoundé II, previously the University of Yaoundé, belong to the Francophone university association AUF (L’Agence universitaire de la Francophonie Citation2020). There is also a ‘double system’ in academic promotions, a national one and one through African and Malagasy Council for Higher Education, CAMES (Conseil Africain et Malgache pour l’Enseignement Supérieur Citation2020). Franchophone academic networks are a major part of Cameroon’s intellectual connectivity.

Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, too, the opposition has been unable to challenge the position of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) on a level playing field. The repressive policies of the regime, including the occupation of the large farms, once a main source of foreign exchange earnings, have led to serious economic downturn and erosion of public services. In 2008 the hyperinflation rendered salaries worthless also in the universities. An increase of fuel price of 150 percent in early 2019 led to mass demonstrations. The government responded by shutting off access to the internet, which was restored only after the court ruled it unlawful. The working conditions at the University of Zimbabwe, however, in terms of resources, infrastructure and salaries have seriously deteriorated. Due to the continuing economic crisis, in the summer of 2019 university workers’ committees wrote to university authorities that their inflation-eroded salaries are no longer enough for them to be able to afford transport to work more than two days a week (Mukeredzi Citation2019).

Yet the goal of the government is to transform Zimbabwe into an upper-middle income country by 2030. This includes the Ministry of Higher Education plan of 2019 for higher education ‘5.0-University vision’, which has stipulated that in addition to education, research and community service, universities have to includeinnovation and industrialisation as new tasks in their activities. The University declares itself as ‘Zimbabwe’s Global Centre of Excellence in Research, Innovation and Higher Education Training’ (University of Zimbabwe Citation2020a). Internationalisation is listed among its key strategic thrusts (University of Zimbabwe Citation2020b). And when attracting students the university notes its ‘exceptional international reputation’ as it is ‘among top universities in Africa’, which is ‘evidenced by the numerous accolades presented annually to our scholars, researchers and students at the local, regional and international levels’ (University of Zimbabwe Citation2020c).

Experiences on the ground

For this study, researchers and teachers from the University Botswana, University of Yaoundé I, University of Yaoundé II and University of Zimbabwe, were interviewed between June and November 2019 in Gaborone, Yaoundé and Harare. The interviews are part of a research project ‘The Space and Role of Political Science in the Evolving Democratic Transformation in Africa’ and represent political science scholars in a broad sense, including administration and international relations, and political sociology. The interviewees were identified by their profiles in their universities’ web pages and by a snowball method. The group of 24 interviewees selected for this study, 8 in Botswana, 8 in Cameroon and 8 in Zimbabwe, consists of 16 men and 8 women. Overrepresentation of men reflects the patriarchal structures of the academic environment in much of Africa. As elsewhere, there is a high percentage of women in the student population contrasted with a scarcity of women holding academic positions. The group is diversified covering both younger, emerging scholars and professors with permanent positions. However, their experiences could be coded under shared themes and structure of meanings. Additional interviews, not coded for this analysis, did not add to these themes confirming a saturation point in the data collection. My approach here is what Saunders et al. have defined as ‘inductive thematic saturation, based on the identification and number of codes or themes rather than the completeness of theoretical categories’ (Saunders et al. Citation2018, 1896).

The obvious limitation is that the scholars who were interviewed in one way or another have been able to proceed in their academic careers. What is thus missing are first-hand testimonies of those who have been unable to do so. And even though the three countries provide a rich variety of experiences, it goes without saying that generalisations to the whole continent should not be attempted.

Semi-structured interviews served the purpose of letting the scholars speak in their own words. The following topics were covered. Firstly, academic freedom to do research, (self)censorship and researchers’ ability to express publicly their views on government policies. Secondly, relevance of university teaching: which fields of political science research and teaching the interviewees found to be socially most relevant? This related to the content of teaching and employment opportunities of the students. The third topic was the relevance of research. Were researchers able to, or invited to, advise the government, civil society, political parties, or international actors? International cooperation and mobility was a crosscutting theme that featured in all these topics and in all 24 interviews – perhaps at least partly due to the fact that this study itself was an example of the theme as such.

Coding the interview transcripts’ references to international cooperation enabled the identification of coherent subthemes that corresponded directly to the topics of the interviews, like censorship, but also to new issues like the push to emigrate. The views and arguments of scholars are presented below along these themes in order to grasp their structure of meanings in the context (Alasuutari Citation1995; Silverman Citation2016). All interviews have been anonymized, and all the interviewees allowed the interviews to be recorded.

I will first describe what was shared in common in the interviews, and then discuss the specific themes on how the meeting of the conditions for academic freedom was frustrated in the three different contexts of political development.

Similarities

The first observation is that all the interviewees were highly motivated and eager to explain their role as global scholars in the particular political environment where they worked. Of course, the fact that all of them had accepted the invitation to the interview, in the first place, explains part of the positive attitude. But taking into account the workload of the academic staff in these universities, the interest in my study is noteworthy, and probably an indication of a broader need to tackle the complexities of producing and disseminating politically relevant knowledge in Africa. To quote one scholar from Cameroon: ‘I’m happy we could meet … I need to also get feedback, and how do you see these things … even things that we don’t always notice, actually. So I’m very, very interested in knowing, and reading what you are going to bring up’.

Secondly, the importance of doing research that is internationally recognised was a frequent theme. In the words of a senior scholar at the University of Botswana: ‘We are global researchers’. A large number of academic staff in African universities have done their doctorate research abroad, ‘in reputable universities’ according to another. And a Zimbabwean scholar noted that this was an asset to make sure their university does not become ‘an isolated institution’. At the University of Botswana, where PhD programmes in social sciences did not exist before 2010, it had been a pattern to send the best students abroad. Many had utilised exchange programmes or grants from abroad, but as the numbers of students had increased, at least the perception was that such opportunities had decreased. In Zimbabwe, the need to get training from abroad was acute. One younger lecturer, who had gone to do a PhD in South Africa with their own savings, explained ‘initially I was studying here, but … the professors who were supervising me, they also have similar challenges that I have been raising, the [teaching] load being too much’.

While there were university level partnerships and collaboration, personal relations were said to be most important. Researchers and teachers were using the networks they themselves had established. Many were ‘ad hoc’, according to a senior scholar at the University of Botswana. This was also related to the individual attempts to get resources for research: ‘we have to create international partnerships and seek finances from abroad. The paradox is that our universities often do not give any support’.

Thirdly, the unanimous view of those interviewed was that they and their colleagues had academic freedom. This was seen as stemming firstly from the collegial decision-making at the departmental level, and secondly from the nature of academic career and merits that one needs in order to be promoted, most importantly scientific publications in international peer reviewed journals. The important national universities covered in this study aspired to be internationally recognised as also expressed in their strategies and visions. Thus, the international standards for academic excellence were well respected.

The interviewees regarded cases where the state had explicitly interfered in the academic affairs, or where individual scholars had been harassed, as exceptional, but nevertheless as cases they were remembered, and the reasons behind them, as worthy of reflection. Implicitly at least, the concern that something similar could happen also in the future was apparent.

‘You can resign and go’

Lack of funding and time to do research were common obstacles to proceed in an academic career in African universities, where teaching has been prioritised over research since the colonial era. As already mentioned above, the workload of teachers is heavy. This is mainly due to the big size of classes. In Zimbabwe, for example, fees paid by the students are very moderate, a direct incentive for the university to keep the student intake high. High intake also affected the background knowledge and motivation of the students and also led to a general frustration with regard to the quality of teaching. One of the interviewees at the University of Zimbabwe said that ‘the big problem in arts and social science is plagiarism. Students have become lazy … the essays that I get are plagiarized’.

At the University of Zimbabwe, scarcity of resources had also affected research infrastructure, electricity cuts and internet downtimes were frequent. Even the toilets were out of order. The response of state authorities to the concerns of difficult working conditions and government priorities in education has been harsh. According to one scholar, they were explicitly told by a government minister in a public occasion: ‘if you do not work here, you can resign and go … state universities have no autonomy … if you want to be funded, you have relative autonomy’.

And indeed, this is what had happened. The University of Zimbabwe experienced ‘a massive exodus of lecturers’ in 2007 and 2008 to South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Australia. One of the consequences had been that a large number of the remaining lecturers at the university were ‘inexperienced lecturers … they need support so that they can establish their own contacts … they do not have contacts even in the region’. Lack of resources had affected possibilities to recruit senior staff, whether locals or foreigners. One scholar referred to the high inflation: ‘Why do you want to come and get this silly Zimbabwean dollar?’ A similar mood was shared by potential returnees, Zimbabwean academics, at the University of Botswana.

In practice, the senior university staff had to do extra work like consultancy in order to compensate for their low salaries. In Cameroon, lack of research resources has made appointments as government advisors an attractive alternative to a concentration on the academic career only. Opportunities to work at the ministries or for the President were said to be particularly important to those who did not have international connections and had not found funding for their own research. But the government was also eager to employ those who were well connected. One of the interviewees said this meant ‘subverting what is best to serve the political agenda’.

On the other hand, scholars who worked at the Cameroonian universities had made a conscious choice to invest in their academic careers. One of them explained: ‘I thought, and I still think, that my contribution as a political scientist will have a greater impact in Africa, than if I was based in Europe or in America … It was clear that I wanted to train more people, to train in a domain which is in lack of academic expertise, at the time, Africa was the place, not the US’. Another scholar, when speaking about the complicated relationship between political science and politics in Cameroon, said: ‘I think parts of the issue is that the best of us are going. So we cannot just leave the country like that, and, you know, stay abroad and continue being critical from there’.

The same scholar continued about the importance of international cooperation for somebody who has returned to a politically tense environment in Africa: ‘I decided to come back, but to try to always keep contact with at least one institution [abroad], I try to have at least one international project going on. So that I can move’. Keeping that contact alive, however, was not easy. The university authorities were not willing to let the government critics go for official exchange: ‘they know that they cannot convince me to present Cameroon the way they want, they will tell: “we cannot let you go, you can quit if you want.”’

‘Those who are able to appear internationally are very critical’

Freedom to do research and design university teaching did not mean freedom of expression. In Cameroon, one of the interviewed scholars referred to the university authorities, appointed by the President by saying: ‘it’s not that they are controlling the curricula, they are controlling people’. There was no government censorship, but people were censoring themselves. Scholars felt that featuring in the media was too often interpreted as supporting either the opposition or the government. Many said that political science in particular was ‘a matter of great suspicion’. One scholar in Cameroon stated: ‘I am not comfortable, I am just an academic. I am not comfortable going to speak to the media like that’.

Similar views were expressed by Zimbabwean scholars. The situation was very different from that of the 1990s and early 2000s, when academics featured as active members of the civil society movements campaigning for political rights and participating in public debates. The mood now was disappointment rather than mobilisation for change; concern for economic survival rather than fear of government interference or political harassment. As noted by a Zimbabwean political scientist: ‘I remember some media guys came to our department, tried to interview from office to office. Nobody was interested. Because people think, what is the point … Our guys from the department are no longer interested. If it is government media, they will switch off what you are saying to suit their own … It is not something people are looking for’.

The situation of those who were abroad was different, however. They had space and resources to criticise the government and, in some cases, even to mobilise the opposition. A scholar in Cameroon stated, ‘I wrote many pieces for the media when I was [abroad] … but lately I have not’. According to another, ‘those who are able to appear internationally … are very critical. So I think there is a link, clearly. Those who are able to access that dimension, they do not have the same relationship to the state’.

‘How critical can you be of your host?’

The University of Botswana, unlike the Universities of Yaoundé I and II and the University of Zimbabwe, had quite a significant number of non-nationals among its students and academic staff. But even there the share of non-national staff has decreased. An interviewee in political science said: ‘unfortunately, we do not have many, two Zimbabwean, one Zambian, three, one point at the time of Kenneth Good, we had around seven or so’.

The above-mentioned case of Kenneth Good was well remembered. The declaration of a professor as an ‘undesirable Immigrant’ by the government was seen as a serious scar on Botswana’s reputation. The case was explained by the intolerant personality of the then vice-president Ian Khama, and the government just taking ‘advantage of the fact that Good was not citizen’. However, one of the interviewees added that Good was not the first and only case, when a foreign academic has been victimised due to ‘some unflattering comments about the government’. There had been at least one case when a critically-minded foreign academic had been arbitrarily denied contract renewal.

What was seen to have made Good’s writings so intolerable for the government was the connection to the internationally known indigenous Masarwa population in the Kalahari. This also explained why, according to the interviewees, research permits for all research had become mandatory, even for local researchers. The Masarwa were referred to as an ‘over-researched’ and ‘over-photographed’ group raising genuine ethical concerns and justifying rigorous regulation of research activities in Kalahari. According to one scholar, colleagues at the department did not know why Good was deported. But there had been rumours, because it happened at the time when the Masarwa were told to leave the Kalahari game reserve, that the government had found diamonds in Kalahari. Even a hint of a possibility of Botswana’s diamonds being labelled ‘blood diamonds’ was seen as too damaging to the regime. Most significant, however, was not what Good had written or argued. None of the interviewees actually referred to the original article written by Good and his co-author, or its content, except by saying that it had contained ‘absolutely nothing new’. The Significant fact for them was that he was a foreigner. ‘Sometimes it is not what you say that matters, but who says it’, in the words of one of the interviewees.

It is not surprising that non-national academics felt that as ‘outsiders’ they did not enjoy the same ‘level of openness’ as the locals. One of them explained, ‘I also speak as a foreigner. How free, critical you can be of your host? How politely you can say (sic)?’ Yet, non-national academics had a prominent role in the country. Paradoxically, and in contrast to Cameroon where the government was co-opting the best of the local scholars, in Botswana, the government was said to prefer non-nationals as its advisors. According to one interviewee, the government consultancy funds go mainly to expatriate consultancy companies, because ‘the government has no confidence, or simply fears its own people, and they then tend to give consultancies to expatriates, who can give the sort of recommendations that they want to hear’.

‘Our literature is too European’

Discussion on the relevance of higher education, an enduring issue in all universities, brought the broader theme of decolonisation to the interviews. According to one of the scholars in Cameroon, the American political science ‘standard which had to be applied in Africa’ has been methodologically catastrophic. This was because the conceptualisation of social, political or economic change came from the experience of the West. The frustration of the African scholars was that ‘it’s a whole area which you exclude from analysis because you have the wrong criteria’. Yet it was difficult to escape the influence of the Western concepts and criteria, as they had formed part of the training of the scholars themselves, were at the core of international academic debates and excellence, and were applied also by organisations like the World Bank.

Academic freedom, in this epistemic dimension, points to the need to Africanise the content of teaching. An interviewee from the University of Botswana told that an external evaluator, who happened to come from West Africa, had criticised their course contents and reading lists as ‘too European’. The teachers had agreed on this and unanimously decided that they needed to do something, ‘but it is easier said than done’. Very little had changed.

A practical problem was the lack of African or locally published textbooks, which in turn was related to the bigger problem of indigenous knowledge production in competitive academic publication markets. While the universities were encouraging or even demanding teachers to include African literature in the course material, and to design course modules focusing on local issues, real incentives and opportunities to produce content that was missing. At the University of Zimbabwe, for instance, all degree programmes were supposed to include a module on Zimbabwean heritage. The teachers, however, were not certain how that was defined in various disciplines, even less had certainty of any resources available for the creation of such new course modules.

Most importantly, the production of course material was not regarded as valuable as the publication of articles in peer reviewed journals, international high impact journals, published in the UK or US, among others. Nor were the markets for African textbooks lucrative to commercial publishers. The fact that there were no course literature on local governance in Botswana, and that the interviewees expressed little prospects to get that kind of literature, was just a fact – a regrettable one as the lack of that kind of material meant the students then were taught with a material describing local governance in Western democracies.

Conclusion

While mobility and freedom are interdependent and indispensable elements of academic work all over the world, their realisation is often uneven and incomplete. In order to understand the conditions enabling or instigating mobility, and vice versa the function of mobility supporting or compromising academic freedom, the distinction between the three dimensions of academic freedom: negative, positive and epistemic, is crucial.

The perceptions and experiences of scholars representing social and political sciences at the main national universities in Botswana, Cameroon and Zimbabwe, revealed that they were not only affected by the powers of the governments and space available for critical expertise and in terms of material conditions of universities, for instance, but also by the general internationalisation of higher education and research and its competitiveness.

The African scholars navigate in the global and national environments where academic freedom is perceived but can still be and has been restricted. In all three countries studied here, the powers of the president and the dominant ruling parties extended to the university affairs, but not in an unambiguous way. What also mattered was the general political situation. In the most stable case, Botswana, local academics had space to be critical. The position of non-nationals, however, appeared to be uncertain. In Cameroon, which was in the middle of internal conflict, academics tended to self-censor themselves and saw mobility as an opportunity supporting their academic freedom. In Zimbabwe, this same perception, an exit option, was explicitly used by the government to frustrate the demands of the academics concerning their working conditions.

Lack of international connections and lack of resources increased the vulnerability of academic staff. In Cameroon, the government was able to co-opt the academics directly into its services with better remuneration and facilities than those provided at the universities. In Botswana, where the political system was more open and universities better resourced, it was foreign scholars whose consultancy the government was eager to use.

In all countries, like elsewhere in Africa, the issue of locally relevant research and course material vis-á-vis material dominated by colonial or Western approaches was a concern. This relates to the overall standards and expectation of the global academia and higher education system and the competition in it. Different monitoring and assessment techniques in the university management have harmonised tangible goals for the universities, like publications in internationally acclaimed peer review journals, instead of textbooks for local students. The consequent underrepresentation or exclusion of knowledge produced in Africa and relevant for African social, political and economic realities, distorts academic freedom there. To that extent decolonisation of the curriculum is a condition of academic freedom.

Academic mobility is a powerful social and political force in a globalised world. It features also among the harmonised goals for the universities. This as such empowers the global academia in its attempts to support academic freedom in all parts of the world. Therefore, decolonisation should be a global responsibility and deserves to be investigated in detail in the context of international co-operation too.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Anna Kristine Johansen for the interviews conducted in Cameroon, Kajsa Hallberg Edu for discussions on student mobility, the participants of the International Conference of the Consortium for Comparative Research on Regional Integration and Social Cohesion (RISC) in Johannesburg, South Africa, 4–5 November 2019, for comments and suggestions, Suzy Graham for patience and editorial help, and two anonymous reviewers who helped to improve the article drastically. My deepest gratitude goes to colleagues in Gaborone, Harare and Yaoundé, who devoted their precious time to my study in the summer and autumn of 2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- African Union. 2018. “First Progress Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on Academic Mobility Scheme in Africa.” Meeting of the Permanent Representatives’ Committee, March 29, 2018 Addis Ababa. https://au.int/en/documents/20180329/first-progress-report-chairperson-commission-academic-mobility-scheme-africa.

- Alasuutari, Pertti. 1995. Researching Culture: Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies. London: Sage.

- Altbach, Philip G. 2004. “Higher Education Crosses Borders: Can the United States Remain the Top Destination for Foreign Students?” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 36 (2): 18–25. doi:10.1080/00091380409604964.

- Altbach, Philip, Maria Yudkevich, and Laura E. Rumbley. 2015. “Academic Inbreeding: Local Challenge, Global Problem.” In Academic Inbreeding and Mobility in Higher Education: Global Perspectives, edited by Maria Yudkevich, Philip G. Altbach, and Laura E. Rumbley, 1–16. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Appiagyei-Atua, Kwadwo, Klaus D. Beiter, and Terence Karran. 2016. “A Review of Academic Freedom in African Universities Through the Prism of the 1997 ILO/UNESCO Recommendation.” AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom 7 (2): 1–23.

- Beiter, Klaus. 2014. “The Protection of the Right to Academic Mobility under International Human Rights law.” In International Perspectives on Higher Education Research, Volume 11, Academic Mobility, edited by Nina Maadad, and Malcolm Tight, 243–265. Bingley: Emerald Group. doi:10.1108/S1479-3628_2014_0000011019.

- Berlin, Isaiah. 1969. Four Essays on Liberty. London: Oxford University Press.

- Bilecen, Başak, and Christof Van Mol. 2017. “Introduction: International Academic Mobility and Inequalities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1241–1255. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300225.

- Börjesson, Mikael. 2017. “The Global Space of International Students in 2010.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1256–1275. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300228.

- Conseil Africain et Malgache pour l’Enseignement Supérieur. 2020. “Missions.” February 24, 2020. https://www.lecames.org/missions/.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. 2020. “V-Dem Dataset v10”. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Dervin, Fred. 2011. “Introduction.” In Analysing the Consequences of Academic Mobility and Migration, edited by Fred Dervin, 1–10. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Fahey, Johannah, and Jane Kenway. 2010. “International Academic Mobility: Problematic and Possible Paradigms.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 31 (5): 563–575. doi:10.1080/01596306.2010.516937.

- Fatunde, Tunde. 2017. “President Cracks Down on, Shuts Anglophone Universities.” Times Higher Education News, October 10. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20171010121644957.

- Good, Kenneth. 2017. “Democracy and Development in Botswana.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1080/02589001.2016.1249447.

- Good, Kenneth, and Ian Taylor. 2006. “Unpacking the ‘Model’: Presidential Succession in Botswana.” In Legacies of Power, edited by Roger Southall and Henning Melber, 51–72. Cape Town: HSRC Press and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Unpacking%20the%20%E2%80%98model%E2%80%99%3A%20Presidential%20succession%20in%20Botswana&author=K.%20Good&author=T.%20Ian&publication_year=2006.

- Grimm, Jannis, and Ilyas Saliba. 2017. “Free Research in Fearful Times: Conceptualizing an Index to Monitor Academic Freedom.” Interdisciplinary Political Studies 3 (1): 41–75. doi:10.1285/i20398573v3n1p41.

- Hoffman, David M. 2009. “Changing Academic Mobility Patterns and International Migration: What Will Academic Mobility Mean in the 21st Century?” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (3): 347–364.

- Hurst, Ellen. 2014. “English and the Academy for African Skilled Migrants: The Impact of English as an ‘Academic Lingua Franca’.” In International Perspectives on Higher Education Research Volume 11, Academic Mobility, edited by Nina Maadad and Malcolm Tight, 153–173. Emerald Group: Bingley.

- Katsakioris, Constantin. 2019. “The Lumumba University in Moscow: Higher Education for a Soviet–Third World Alliance, 1960–91.” Journal of Global History 14 (2): 281–300. doi:10.1017/S174002281900007X.

- Kim, Terri. 2009. “Transnational Academic Mobility, Internationalization and Interculturality in Higher Education.” Intercultural Education 20 (5): 395–405. doi:10.1080/14675980903371241.

- Kim, Terri. 2010. “Transnational Academic Mobility, Knowledge and Identity Capital.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 31 (5): 577–591.

- Knight, Jane, and Emnet Tadesse Woldegiorgis. 2017. “Academic Mobility in Africa.” In Regionalization of African Higher Education: Progress and Prospects, edited by Jane Knight and Emnet Tadesse Woldegiorgis, 113–133. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kratou, Hajer, and Liisa Laakso. 2020. “Academic Freedom and the Quality of Democracy in Africa.” The Varieties of Democracy Institute, Users Working Paper Series (33).

- Kritz, Mary. 2015. “International Student Mobility and Tertiary Education Capacity in Africa.” International Migration 53 (1): 29–49, 53. doi:10.1111/imig.12053.

- L’Agence universitaire de la Francophonie. 2020. “Qui Nous Sommes.” February 24, 2020. https://www.auf.org/a-propos/qui-nous-sommes/.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. 2019. “Decolonising Universities.” In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge, edited by Jonathan D. Jansen, 15–28. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press.

- McKay, Vernon. 1968. “The Research Climate in Eastern Africa.” African Studies Bulletin 11 (1): 1–17.

- Mogalakwe, Monageng, and Francis Nyamnjoh. 2017. “Botswana at 50: Democratic Deficit, Elite Corruption and Poverty in the Midst of Plenty.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/02589001.2017.1286636.

- Mukeredzi, Tonderayi. 2019. “University Staffers Say They Cannot Afford to Work.” University World News, July 11, 2019. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190710141523655.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2015. “Decoloniality as the Future of Africa.” History Compass 13 (10): 485–496. doi:10.1111/hic3.12264.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2018. Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization. New York: Routledge.

- Nganang, Patrice. 2017. “Cameroun: carnet de route de l’écrivain Patrice Nganang en zone (dite) Anglophone.” Jeune Afrique, January 5, 2017. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/499512/politique/cameroun-carnet-de-route-de-lecrivain-patrice-nganang-en-zone-dite-anglophone/.

- Oucho, John. 2008. “African Brain Drain and Gain, Diaspora and Remittances: More Rhetoric Than Action.” In International Migration and National Development in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by Adepoju Aderanti, Ton van Naerssen, and Annelies Zoomers, 49–66. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Ramirez, Francisco O., and Tom Christensen. 2013. “The Formalization of the University: Rules, Roots, and Routes.” Higher Education 65: 695–708. doi:10.1007/s10734-012-9571-y.

- Said, Edward. 1994. Representations of the Intellectual. London: Vintage.

- Saunders, Benjamin, Julius Sim, Tom Kingstone, Shula Baker, Jackie Waterfield, Bernadette Bartlam, Heather Burroughs, and Clare Jinks. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52: 1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Silverman, David. 2016. Qualitative Research. . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing.

- Smallwood, Anthony, and Ted L Maliyamkono. 1996. “Regional Cooperation and Mobility in Higher Education: The Implications for Human Resource Development in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Relevance of Recent Initiatives to Europe.” In Academic Mobility in a Changing World: Regional and Global Trends, edited by Peggy Blumenthal, Crauford Goodwin, Alan Smith, and Ulrich Teichler, 320–337. London: J. Kingsley.

- Spannagel, Janika, Katrin Kinzelbach, and Ilyas Saliba. 2020. “The Academic Freedom Index and Other New Indicators Relating to Academic Space: An Introduction.” The Varieties of Democracy Institute, Users Working Paper Series (26).

- Stensaker, Bjørn, Jenny J. Lee, Gary Rhoadesb, Sowmya Ghosh, Santiago Castiello-Gutiérrez, Hillary Vanceb, Alper Çalıkoğlu, et al. 2019. “Stratified University Strategies: The Shaping of Institutional Legitimacy in a Global Perspective.” The Journal of Higher Education 90 (4): 539–562.

- Teferra, Damtew. 2000. “Revisiting the Doctrine of Human Capital Mobility in the Information Age.” In Brain Drain and Capacity Building in Africa, Exode des Dompetences et Developpement Descapacites en Afrique, edited by Sibry JM Tapsoba, Sabiou Kassoljm, Pascal V. Holieno, Bankole Oni, Meera Sethi, and Joseph Ngu, 62–77. Addis Ababa: ECA/IDRC/IOM.

- Tettey, Wisdom, and Korbla P. Puplampu. 2000. “Social Science Research and the Africanist: The Need for Intellectual and Attitudinal Reconfiguration.” African Studies Review 43 (3): 81–102.

- The Kampala Declaration on Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility. 1990. Dakar: Codesria. http://abahlali.org/files/Kampala%20Declaration.pdf.

- Tournès, Ludovic, and Giles Scott-Smith. 2017. “A World of Exchanges: Conceptualizing the History of International Scholarship Programs (Nineteenth to Twenty-First Centuries).” In Global Exchanges: Scholarship Programs and Transnational Circulations in the Modern World, edited by Ludovic Tournès, and Giles Scott-Smith, 1–29. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Tsie, Balefi. 1996. “The Political Context of Botswana’s Development Performance.” Journal of Southern African Studies 22 (4): 599–616. doi:10.1080/03057079608708514.

- UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). 2020a. February 19. https://data.uis.unesco.org/#.

- UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). 2020b. February 19. https://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow.

- University of Botswana. 2020. “Office of International Education and Partnerships.” February 20, 2020. https://www.ub.bw/discover/administration-and-support/office-international-education-and-partnerships.

- University of Zimbabwe. 2020a. “Our Mission.” February 23, 2020. https://www.uz.ac.zw/index.php/our-mission.

- University of Zimbabwe. 2020b. “Strategic Goals.” February 23, 2020. https://www.uz.ac.zw/index.php/about-uz/uofz-overview/strategic-goals.

- University of Zimbabwe. 2020c. “Why Choose UZ.” February 23, 2020. https://www.uz.ac.zw/index.php/admissions/why-uz.

- Woldegiorgis, Emnet Tadesse, and Martin Doevenspeck. 2015. “Current Trends, Challenges and Prospects of Student Mobility in the African Higher Education Landscape.” International Journal of Higher Education 4 (2): 105–115.