ABSTRACT

The 2021 South African local government elections continued a trend of dissipating turnout among young voters. The youth, aged 18–34, constitute nearly a third of SA's adult population, and their voting decisions could have a decisive influence on electoral politics. Youth voter behaviour - including that of the ‘born-free’ generation - has been an area of critical interest. However, this interest has mostly yielded an image of young people as disillusioned, consistent abstainers. We argue that youth electoral behaviour should be approached not as a binary of voter/abstainer, but be placed along a voting-behavioural continuum. Our analysis of UJElection Survey and the South African Social Attitudes Survey data, supports concepts that function as markers along this continuum, including ‘loyal voters', ‘casual voters', ‘party-loyal abstainers' and ‘consistent abstainers', each with different underlying motivations. Ultimately, this dispels static notions, providing a more nuanced and complex picture of youth voter behaviour.

Of all politically-active cohorts, the youth vote tends to attract the most scholarly attention, with a focus on their role as a harbinger of future political trends (Bergan et al. Citation2022; Medenica Citation2018; Seagull Citation1971; Sweetser Trammell Citation2007). In South Africa, the role of the youth vote is particularly interesting. Voting-eligible adults between the ages of 18–34 years,Footnote1 ‘the youth’, make up a third of the South African electorate and, therefore, as Schulz-Herzenberg (Citation2019a) notes, have the potential to be ‘electoral power brokers.’ However, as most young people do not have a habit of registering and voting, this potential is not converted into electoral power. Of the nearly 1.8 million people in the 18–19-year-old age group eligible to vote in the last election, 90% did not register (IEC Citation2021). Similarly, less than 20% of the population aged 20–34 registered to vote, in contrast to over 90% of the population aged 40 and older (IEC Citation2021). As a result, there has been an overarching concern to analyse youth voter abstention (Oyedemi and Mahlatji Citation2016). While valuable, this has yielded a picture of youth electoral behaviour as relatively static. Understanding the relations between voting, vote choice and abstention among the youth are important for providing insights into the future of multi-party democracy in South Africa.

This article seeks to go beyond a binary interpretation of youth voter behaviour in order to provide a more dynamic discussion. To do so, we elaborate and develop the concepts derived from behavioural models of electoral turnout to discuss the concepts of loyal voters, casual voters, party-loyal abstainers and consistent abstainers in the South African context and introduce the concept of party-loyal abstention. We illustrate the importance of these categories to analysing the youth electorate and argue for their utility to the electorate at large. Our analysis is derived from two survey datasets, the Centre for Social Change (CSC), University of Johannesburg Election survey (hereafter simply Election survey) and the Human Sciences Research Council’s (HSRC) South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS).

Analysing youth voter behaviour

Young people vote less readily than older cohorts almost everywhere (Henn and Foard Citation2012). This is intriguing – not least because, in most countries, as a cohort, they have more voting power than others – but also because compared to older generations, a much bigger proportion of young people today has a higher level of educational attainment on average – a factor conventionally linked to greater turnout rates (Pickard Citation2015). The most commonly cited reasons for decreasing turnout are ‘voting costs’ (Fowler Citation2006, Plutzer Citation2002) or barriers to voting, which are typically magnified for the youngest voters. These include: navigating the process of registration for the first time; identifying the location of polling places; learning about parties and candidates; and relying on a peer group that includes a large share of similarly inexperienced young voters.

Voter behaviour can be analysed at the hand of rational choice theory (and its derivations), or by behavioural alternatives, as proposed by Bendor et al. (Citation2003) and Fowler and Smirnov (Citation2003). Bendor et al. (Citation2003) predict the phenomenon of casual voting – that people sometimes vote and sometimes abstain, while Fowler’s models, supported by empirical evidence from the global north (e.g. Gerber, Green and Shachar Citation2003, Plutzer Citation2002, Verba and Nie Citation1987), instead finds that most people either vote always or never – they are loyal voters or consistent abstainers. More recently, Blais and Daoust (Citation2020) have shown that the factors influencing human political decisions are not purely rational ones, arguing that this relates to (universal) human psychology as much as it does to parochial factors. They go further, based on a five-country study of Canada, France, Spain, Switzerland, and Germany, arguing that the decision to vote (or not) is related to a person’s interest in politics in general, whether people perceive a moral obligation to vote, whether people perceive the outcome to be important to them (and whether they might influence the outcome), and how easy the election-related logistics (prior arrangements, travel times and costs, queuing, and the voting process itself) is to navigate for an ordinary person. All these factors take on special significance when understood through the lens of youth.

It is generally held that young people in advanced democracies are more politically apathetic and are less invested in voting as a practice of civic engagement (Dalton Citation1999; Norris Citation1999). Instead, it is argued, young people find their democratic expression through alternative means of political participation (Pickard Citation2015), often through protest. Exploring this within the context of 19 of the ‘most democratic’ countries in Africa, Resnick and Casale (Citation2011) demonstrate that while young people do vote less there is no clear indication that they are more likely to turn to protest than older citizens as an alternative means of democratic expression. However, the socio-political contexts across the continent clearly vary considerably and are distinct from that of advanced democracies. While the countries analysed by Resnick and Casale (Citation2011) are the ‘most democratic’, it is still important to highlight that the ‘costs’ of protest through direct or indirect repression and political violence may still be higher than those in advanced democracies. This, arguably, makes protest less readily available than in other contexts.

The life cycle of youth also shapes voter behaviour. It is argued that young people are less embedded in social networks that often mobilise people to vote, such as trade unions, churches and other voluntary associations (Magalhães, Segatti, and Shi Citation2016). In South Africa, Schulz-Herzenberg (Citation2019b) found that informal social networks such as partners and friends who discuss political issues or who vote themselves play a powerful role in influencing the decision to vote, but that secondary associations, such as trade unions, churches and voluntary associations, play a minimal role. She highlights that the waning of influence of trade unions and churches may have had a particular impact on the African National Congress’ (ANC) vote, who can no longer be relied upon to bring their constituencies out to vote for the ANC.

Related to the analysis of the life cycle is the role of partisanship. Both in South Africa and internationally, scholars find that young people have weaker partisan ties, in part because they have not had the time to develop a relationship of loyalty to a political party. Dalton (Citation2013) finds that partisans are more likely to vote than non-partisans and Schulz-Herzenberg (Citation2019b) similarly finds that this has a strong influence on voter turnout in South Africa. What remains in question is whether young people are likely to develop partisan ties as they age.

In analysing the influences on partisanship, Jaime-Castillo and Martínez-Cousinou (Citation2021) argue that four factors influence the development of partisan ties. The first factor is family socialisation. The second is the extent to which people see a political party as representing their own individual identity. The third is the extent to which they see other parties as representing stereotypes, and lastly the extent to which identity politics – practices or claims that construct political identity based on common descent, language, culture, or ideological persuasion, or another group identity contribute to the development of partisan ties.

Translating these insights into the South African context produces some interesting insights. As Mattes and Glenn (Citation2021) demonstrates, the social and political attitudes of the born-free generation – those born after the first democratic elections of 1994 – are distinct from that of their parents, suggesting that the role of family socialisation is not as great as it may be in other parts of the world. However, the role of identity may still be critical in the development of partisan ties. Race is an important factor in South Africa’s elections. Some scholars (Habib and Naidu Citation1999, Citation2006; Ferree Citation2006) go as far as arguing that South African elections are a ‘racial census’, because voters largely choose from different sets of parties, with little overlap. However, Friedman (Citation2015) is critical of this perspective. He highlights that White suburban support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) is more stable than Black support for the ANC. Indeed, he highlights that the race-party loyalty connection is frequently deployed in popular, and occasionally scholarly discourse, to portray the Black African majority as ‘an unthinking herd, willing to vote for the ANC whatever it does’, conveniently ignoring the fact that ‘electoral politics in the ANC’s strongholds is currently far more contested than that in the DA’s fiefdoms’ (Friedman Citation2015, 156).

Survey data and the 2021 local government elections

The analysis presented in this article draws on two data sources. The first is the Elections dataset is based on a telephone survey of 3905 registered voters conducted by the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Change (CSC) between 2 and 16 November 2021 within five metropolitan municipalities: Johannesburg, Tshwane, eThekwini, Cape Town, and Nelson Mandela Bay. As this was a local government election (LGE), we opted to draw a sample based on a selection of municipalities so that we may be able to understand our data within the local political context of the municipalities rather than drawing a nationally representative sample. Stratified random sampling was used, with strata based on socioeconomic status, race, gender, and age. When weighted, the data is representative of the registered voting age population in the five metropolitan municipalities. The registered population is a more restrictive focus than the total voting-age population (VAP), since slightly more than a third of eligible adults have not registered, with the latter concentrated among younger cohorts. The survey sample is therefore under-representative of those who abstain. presents the basic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Election survey sample characteristics (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

The under-representation of abstainers is not a problem unique to this survey. As Selb and Munzert (Citation2013) note, internationally, post-election surveys tend to suffer comparable problems in the overrepresentation of actual voters as non-voters are more likely to decline participation in surveys focussed on voting as well as actual non-voters misreporting their electoral participation due to the pressure of social desirability. In contrast, pre-election or social attitudes surveys, like the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), are less likely to be affected by non-voters declining to participate, but they may similarly suffer the mis-reporting of intended electoral participation due to social desirability bias.

The Election survey has evolved from previous exit poll work undertaken by the CSC (Paret Citation2016, Citation2018). As such, the survey instrument was developed from those previously deployed as part of the exit poll and reflects the CSC’s interests in the relationship between protest and voting. The final survey included 23 questions: 12 questions on socio-demographic variables; three questions on protest history; five on voting; and two questions on political opinions. Resource constraints meant that they survey instrument had to be kept necessarily short and there was therefore no scope to further probe a range of attitudinal variables that may influence voting as well as non-voting. While this is a limitation of the Election Survey in comparison to other datasets, we believe that the strength of the data lies in its ability to capture a picture of the South African electorate in the period immediately after the election.

Singh and Thornton (Citation2019) note that, as time passes from an election, reported partisan attachments decrease. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the passage of time may also influence how people answer questions about their voting choices. Other post-election surveys, such as the South African National Election Study and the Comparative National Elections Project (CNEP), tend to be conducted months or even up to a year after the election has been held, when it is possible that changing socio-political contexts may influence how people answer questions about voting. The timing of the Election survey, hopefully, overcomes some of these challenges.

A further strength of our survey instrument is the inclusion of an open-response question that asked people to explain the reason for their party choice or abstention in the 2021 election in their own words. These answers were then coded through a combination of inductive and deductive coding. Deductive codes exploring reasons for voting were based upon similar analysis conducted by the researchers in response to the same question in previous exit polls. This was combined with inductive coding for themes that were repeated but did not fit into the pre-established coding schema. Similarly, the reasons for non-voting were coded using a combination of deductive and inductive coding. Deductive codes were developed from the HSRC Voter Participation Survey (VPS) series, conducted on behalf of the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC), that have also analysed reasons for voter abstention. This was combined with inductive coding for emergent themes in the data. provides the code list developed to analyse these responses. The inclusion of this data means that we can probe more deeply into the explanations that respondents gave for voting or not.

Table 2. Category descriptions: reasons for voting and not voting (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

To compensate for some of the limitations of the Election survey data we also draw upon SASAS for additional and confirmatory evidence The SASAS series is a nationally representative general social survey series that has been conducted on an annual basis since 2003 by the HSRC. It is designed to be representative of the adult population aged 16 years and older living in private households. The survey uses random probability sampling to select 3500 visiting points each year, with a single age eligible adult respondent selected from each. The realised sample typically ranges between 2800 and 3100 in each year. The data are weighted based on benchmarking to Statistics South Africa’s mid-year population estimates.

This survey infrastructure has also been used to field the VPS series commissioned by the IEC of South Africa to examine electoral knowledge, awareness, beliefs and behavioural preferences of the voting age public. These surveys are conducted typically six months ahead of national and provincial as well as LGEs, with the purpose of providing evidence of dynamics among the electorate to inform operational planning by the election management body. The SASAS and VPS series routinely includes questions on voting intention and a range of attitudinal, behavioural and other correlates that have a potential bearing on electoral choices. For the purpose of this article, we draw primarily on evidence from the 2021 round of SASAS, which was fielded in September and October 2021, slightly ahead of the November LGE. The realised sample was 2996, and all interviews were conducted face-to-face using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI).

Defining South African youth

The typical classification of youth in South Africa is those aged between 18 and 34 years. However, in generational terms this cross-cuts a group with diverse socio-political experiences. In the United States, researchers have begun to make a distinction between millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) and Generation Z, those born from 1997 onwards (Dimock Citation2019). In South Africa, the term ‘born-free’ has most often been used to identify the youth cohort. However, there is no consistent definition as to how this term is used. For Mattes (Citation2012), the ‘born-frees’ are those born after 1980 and came of age politically after 1996. While some support a similar approach (Nhlapo, Anderson, and Wentzel Citation2017), other scholars restrict this definition to those born on or after 1994 (Oyedemi and Mahlatji Citation2016). However, it is problematic to continue to define an increasing section of the population as simply ‘born-free.’ In 2021, the oldest youth voters (those aged 34 years) were born under apartheid in 1987, while the youngest voters were born under the democratic dispensation in 2003. The socio-political experiences of the youngest and oldest youth are therefore somewhat distinct from one another.

To address this issue, Lappeman, Egan, and Coppin (Citation2020) adapt the work of Strauss and Howe (Citation1991) to map historical events that may be used to distinguish different generations. This analysis leads them to distinguish two generations that currently cross-cut the youth cohort. The ‘transition generation’, those born between 1980 and 1999, who grew up in the twilight of apartheid and the ‘Generation second-wave’, those born after 2000 who have no first-hand experience of apartheid and were born into democracy (Lappeman, Egan, and Coppin Citation2020, 12). However, it must be noted that those born after 1990 among Lapperman et al’s ‘transition generation’ would similarly have little direct experience of apartheid either. With that criticism aside, we believe that there is value in distinguishing generational differences among the current youth cohort. For the purposes of the analysis here, we split the youth into two categories, those aged between 18 and 24 (born between 1997 and 2003), which we refer to us born-free Gen Z, and those aged between 25 and 34 (born between 1987 and 1996), born-free Millennials.

Electoral fluidity in municipal elections

In recent years, the stability of electoral outcomes for the ANC has been in doubt. At the national level, the ANC’s support has declined from a high point of 69.7% of the vote in 2004–57.5% in 2019 (Schulz-Herzenberg Citation2019a, 464). However, these aggregate national election results conceal some of the complexities of South Africa’s electoral politics, which can be more clearly seen at the municipal level. Our sample for the Election survey is derived from five metropolitan municipalities, and it is therefore important to situate the following analysis within an understanding of the electoral outcomes of these particular municipalities. presents an analysis of the aggregate LGE results from 2006 to 2021 within the five metropolitan municipalities.

Table 3. Aggregate LGE results for selected metropolitan municipalities 2006–2021 (%) (Source: IEC).

The City of Johannesburg, the City of Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay are three municipalities where one may assume ANC dominance. However, the table demonstrates how this assumed dominance has been gradually unravelling. The largest decline for the ANC has been within the City of Johannesburg, where their share of the vote declined by 28.7 percentage points between 2006 and 2021. Similar losses have been witnessed in Nelson Mandela Bay where the ANC lost 27.1% of its vote in 2021 compared to 2006. In the City of Tshwane, the ANC lost just over a fifth of its support between 2006 and 2021. In eThekwini the ANC’s electoral fortunes have been uneven. Their support grew between 2006 and 2011. However, their vote share declined by five percentage points between 2011 and 2016 and by a further 13.9 percentage points between 2016 and 2021. In the City of Cape Town, where the DA dominates, we see a growth in their support from 2006 until 2016. However, in 2021, the DA registered electoral losses with its support declining by 8.3 percentage points. Therefore, across all five municipalities, the dominant party – whether the ANC or the DA – all registered significant losses.

For a period of time in the City of Johannesburg, the City of Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay the ANC’s electoral losses were the DA’s gain, with the DA increasing its vote share between 2006 and 2016. However, in 2021 this growth was arrested with the DA losing ground to other opposition parties.

Looking at the 2021 results more closely, one may note that these municipal results look different to the aggregate national picture. Nationally, in the 2021 LGE, the ANC received 45.6% of the vote and the DA 21.7%. ANC support within the five metropolitan municipalities was lower than in the national picture. eThekwini had the highest level of ANC support (42.1%) and the City of Cape Town the lowest (18.6%). While the DA’s support was higher than the national average across all five municipalities. The local context is important to bear in mind when examining the results from the Election survey, which are representative of the five metropolitan municipalities and, therefore, may produce different results than a nationally representative survey. The inclusion of the nationally representative SASAS data within the analysis assists us in helping to identify electoral dynamics that may be specific to local political dynamics, and which may be more broadly representative of the youth electorate.

Youth voting intentions

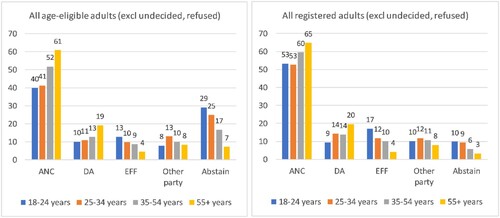

Shortly before the 2021 elections, a round of SASAS was conducted; it asked the voting age public whether they would vote (and for which political party) if an election were held ‘tomorrow’. We analysed these results by age group and registration status. The left-hand graph in shows that among 18–24-year-olds and 25–34-year-olds expressing a clear voting preference, the primary predisposition was to vote for the ruling ANC, at around 40%. This is lower than older age cohorts. Young voters, especially the born-free Gen Z cohort (18–24), were characteristically less inclined to express a preference for voting for the DA, and more likely to support the EFF. There is a clear gradient on abstention, which declines appreciably with age.

Figure 1. Intention to vote if there were an election tomorrow in late 2021, by age group (%). (Source: HSRC SASAS Round 18 2021. Note: Figures exclude those refusing to answer, or undecided in response to, the intention to vote question.)

If we narrow our focus to those that were registered to vote at the time of surveying, a similar age-based voting intention pattern emerges (right-hand graph). ANC support remains the dominant response among registered youth at slightly over 50%, which is approximately 10 percentage points lower than for older age cohorts. The patterning of DA and EFF support among young, registered voters persists; support for other political parties displays less cohort-based variation. Their gradient on abstention flattens out somewhat, due to the exclusion of non-registered voters who have a greater tendency to report planned abstention when asked the voting intention question. Despite this, abstention still tends to decline with age cohort.

One of the limitations of examining voting intentions is that there is a well-established tendency to overstate planned electoral turnout. Nonetheless, the cohort-based pre-electoral intentions outlined above can be compared to the reported electoral turnout and choices from post-electoral surveys such as the Election survey to determine if similar general tendencies emerge. It is also important to note that the SASAS analysis focuses on the voting-age public not just the metropolitan-based electorate.

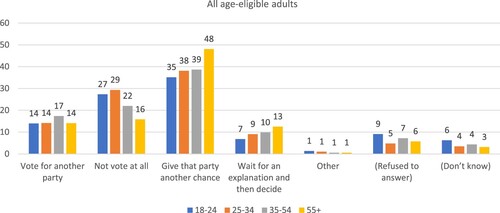

Another SASAS-based indicator related to voting intentions focuses on the electoral response to unfilled expectations. Respondents were asked the following question: ‘If the party you voted for did not meet your expectations, the next time there is an election would you … vote for another party, give that party another chance, wait for an explanation and then decide or respond in some other way?’ These response options provide, in turn, a sense of likely loyal voting, conditional loyalism, swing voting and abstention. Analysing these results again by age shows that the dominant response for all age cohorts is to loyally vote for the party again in the face of unfulfilled expectations. Youth and as well as 35–54-year-olds all display a similar level of loyal voting, while this is more deeply-rooted among voters aged 55 and above. Conditional loyalty (wait for a party explanation for poor performance before deciding) also increases with age, though this was not a particularly common preference. Swing voting was also not especially common or age variant, mentioned by between 14 and 17% across all age cohorts.

Abstention was a more frequent option, especially among the two youth cohorts, where it was selected by close to 30%. Abstention in the face of poor party performance diminishes for older age cohorts. This suggests that party performance produces age-based electoral responses that fluctuate primarily between the dynamics of continued loyalism and abstention, with the former more common to older age cohorts, and the latter more prominent among younger members of the electorate. Confining the findings only to currently registered adults (results not shown) yields largely similar results, with registered youth slightly less likely to prefer abstention and more likely to respond ‘give the party another chance’ relative to unregistered youth. Despite these differences the gradient on abstention is left intact, while the cohort variation in loyalism thins out.

These findings point to a complex calculus in the face of discontent with the party one voted for previously, with the patterns varying in degree of emphasis by age, as illustrated in . The underlying motivations informing such choices are also likely to be multidimensional. With this in mind, we now return to the Election survey to explore some of the motivations informing electoral abstention and party choice among the youth, and the fluidity and dynamics of electoral participation among the electorate.

Youth voter abstention

As discussed above, we know that a sizeable share of young people do not turn out to vote and that the Election survey sample do underrepresent non-voters, nonetheless it still provides an important insight into trends in abstention. provides a breakdown of the abstention rate within the five metropolitan municipalities that make up the sample for the Election survey. As expected, we see that abstention rates were highest among the youth and decline with age. Abstention amongst the youngest age cohort, 18–24 year olds, is more than double that of the oldest age cohort, those aged 55 years and above.

Table 4. Reported abstention rate within 2021 Election survey five metropolitan municipalities (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Moving beyond analysis of the abstention rate, our data allows us to examine why people said that they did not participate in the 2021 LGE. analyses the reasons that respondents provided for their non-participation in the 2021 LGE. The most common reasons provided by born-free Gen Z’s was a combination of individual and administrative barriers, mentioned by 36% and 32% respectively. The self-reported administrative barriers for this cohort related predominantly to not being registered to vote, while individual barriers focused largely on not being in their registered ward on election day. The latter is a particular challenge in LGE, which require voting to take place in a voter’s registered ward. It is interesting to note that self-reported individual barriers were not particularly unique to young people, while administrative barriers were more pronounced among the born-free Gen Z’s. Interestingly, the born-free Gen Z’s reported marginally lower levels of disinterest and disillusionment than older age groups as a factor motivating their decision not to vote, but were relatively less concerned with performance evaluations that older age groups. No substantive variation is evident in relation to lack of political alignment.

Table 5. Reasons for abstention in the 2021 Election survey, by age group (row %) (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

This provides some insight into the motivations behind voter abstention. For the youth, irrespective of their generation, individual and administrative barriers were the primary reasons for abstention, with not registering to vote or being ‘too busy’ to vote are being mentioned among the common reasons provided for not voting. Not registering to vote is a pre-emptive disengagement from electoral democracy, while being ‘too busy’ may suggest that participating in electoral democracy is not strongly valued by some. While these reasons reflect administrative and individual barriers, they are also deeply suggestive of a different kind of disinterest and disengagement from electoral democracy.

For older voters, individual barriers were the most common reason for abstention. However, it is interesting to note that performance evaluations accounted for just over a fifth of explanations for voters aged over 35 years. This appears to be consistent with the SASAS data that illustrated that between 16 and 22% of voters aged over 35 indicated that they would not vote if the party they voted for last time did not meet their expectations.

Youth voting decisions

As established above, a relative minority of youth voted in the 2021 LGE. Despite this, it is vital to understand how the youth vote. shows the analysis of vote choice in the 2021 LGE by age group. For both the born-free Millennials and the born-free Gen Z’s, the ANC is the most popular party, distinguishing them little from older age cohorts. Interestingly, we see that ANC support was the strongest among the Gen Z born-frees and this differs from what we saw within the voting intentions data from SASAS. This suggests that there are some important differences between the municipal and national levels of support for the ANC among the youth. While this finding may seem surprising, in other exit poll work conducted in previous elections we have seen that first-time voters do show a higher propensity for voting for the ANC (Paret Citation2016b).

Table 6. Vote choice in 2021 Election survey, by age group (row %) (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Support for opposition parties differs between the born-free Millennials and the born-free Gen Z. The DA is more strongly favoured by the born-free Millennials, drawing over twice the level of support than from born-free Gen Zs. For born-free Gen Zs, the EFF is the most popular opposition party. Indeed, the table illustrates that the EFF receives most of its support from young people. Another interesting aspect to note is that young people, both born-free Millennials and born-free Gen Zs, seem slightly more inclined to vote outside the three main parties compared to older age groups.

The youth, of course, are not a homogenous category and it’s important to analyse the youth vote further through a selection of socio-demographic factors. As demonstrates, the youth vote follows the expected patterns of racialized support for the three main parties. The ANC was the most popular amongst the Black African youth vote accounting for 59% of their vote. While support for the DA and EFF was almost the same, 11% and 12% respectively, 18% of Black African youth voted for a party outside of the two main opposition parties. While the ANC is clearly the most popular party amongst Black African youth, it does appear that young Black African people may be more likely to cast a vote outside of the two main opposition parties.

Table 7. Political party voted for in the 2021 LGE among those aged 18–34, by selected socio-demographic characteristics (row %) (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Among Coloured and Indian or Asian youth voters, the DA was the most popular party, attaining 46% and 39%, respectively, of the vote. Coloured youth also had the highest proportion of support for parties outside the main three parties. The EFF drew minimal support from among Coloured youth and no votes from the Indian and Asian or White youth in our sample. The DA was overwhelmingly the most popular party amongst White youth with the ANC only receiving 4% of their votes within this sample.

Analysing the youth vote by self-reported gender reveals some gendered differences in party support. Young women support the ANC slightly more than men, 52% compared to 46%. While the EFF drew slightly more support from men compared to women. There seems to be little gendered difference in support for the DA among young people.

Among employed youth, the ANC drew more support among the unemployed while support for the DA was strongest among the employed. The EFF drew a considerable share of its support from among students. While education appears to have the strongest bearing on the ANC’s youth support, with those with a matric or less than matric showing higher levels of support for the ANC than those with tertiary education.

As part of the Election survey we asked participants to explain in their own words why they voted for the party that they had. provides the aggregate results of this analysis. What this table illustrates is that the motivations for party choice are largely consistent with older voters. However, it is interesting to note that party loyalty is more prominent among the born-free Gen Zs compared to older voters. While the motivation for change was most strongly felt among the born-free Millennials.

Table 8. Reason for vote choice, by age group (row %) (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Taking this analysis further, provides an analysis of party choice and explanations for vote choice among the youth. For ANC youth voters, party loyalty is the strongest motivation for their choice (37%), followed by performance evaluations (22%). For DA youth voters, nearly half (45%) explained their vote choice in relation to performance evaluations. While for EFF youth voters, performance evaluations and the desire for change were the two largest motivations provided for their vote choice.

Table 9. Explanations for vote choice in 2021 LGE among those aged 18–34 (row %) (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Voter fluidity

The analysis above provides insights into voting decisions in the 2021 LGE. However, elections are not static phenomena and the advantage of the Election survey data is that it enables us to track voting decisions over time. In this section, we consider the extent of voter fluidity across the last three elections, both national and local government elections, among youth voters. As not all youth would be eligible to vote in the last three elections we restrict our analysis to those aged between 26 and 34 years, those who would have been eligible to vote across the last three elections. This restricts our sample of youth voters to 1172 respondents. This enables us to determine the extent to which young people learn ‘the habit of not voting’ (Schulz-Herzenberg Citation2019b, 370). The Elections survey asked about voting in the 2019 national elections and the 2016 LGE. While it is acknowledged that national and local elections have differing political dynamics, as our previous research has demonstrated (Runciman, Bekker, and Maggott Citation2019), there are broadly consistent profiles of voters across local and national elections meaning that there is basis for comparison.

shows that there is a core (19%) of consistent abstainers among the youth vote within the five municipalities suggesting that there is some credence to the argument that young people are learning not to vote. However, most of the youth who were eligible to vote in the last three elections had some form of participation in at least one election. This suggests that while there may be a core of consistent abstainers that many more young people display a degree of fluidity in their electoral engagement.

Table 10. Vote trajectory of voters aged 26–34 (Source: CSC Election Survey 2021).

Nearly a fifth (18%) of young voters in the five metropolitan municipalities were loyal ANC voters, 6% were loyal DA voters and 2% were loyal to the EFF or other opposition parties. In 2021, 21% of formally loyal ANC voters did not vote again for the ANC in 2021, with the majority opting for opposition (16%) and a minority (5%) opting to vote for an opposition party. This suggests that many young people do not feel able to register their discontent with the ANC through voting for an opposition party and would rather abstain from voting. For young people voting for opposition parties, it is interesting to note that this trend is marked by a pertinent degree of fluidity, with 14% fluctuating between voting for an opposition party or abstaining with a further 4% voting for different opposition parties across the last three elections.

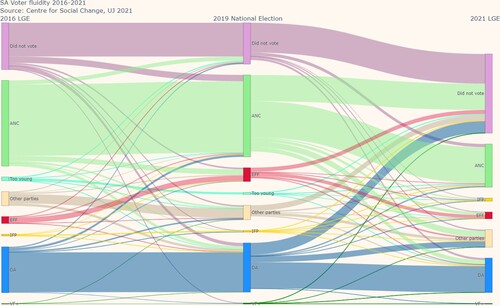

The Sankey diagram in helps to visualise the flow of support among parties (and between electoral participation and abstention) at elections since 2016. Ostensibly the most prominent feature is the illustration of broad and sustained non-participation, made manifest in the ‘Did not vote’ stream: about half of our respondents classified as youth did not vote in any of the elections, several of whom are likely not registered for voting. Besides this, the flows confirm our findings about electoral behaviour in South Africa in general – that there is a non-negligible amount of fluidity between voting and abstention, and in the switching of support from one election to another.

Figure 3. Flow of youth votes between various elections.

While parties generally receive their support from people who voted for them in the previous election, voters are not consistently party-loyal. Evidence of this is seen in how the ANC cedes votes to the DA and other parties (especially looking at the flows from 2019 to 2021) but also towards former supporters not voting in 2021. Similarly, a significant portion of DA voters (in 2019) voted for the ANC or not at all in 2021. As is widely reported elsewhere, the DA appears to be the biggest loser of support between 2019 and 2021. Starkly, more respondents who voted for the EFF in 2019 did not vote in 2021 than vote again for the EFF, while several also gave their vote to smaller (‘Other’) parties. Thus, we confirm the trend of the EFF maintaining support, while not retaining the same voters, from one election to the next, as identified in our 2021 report. There appears also to be a measure of ideological flow – while there is some movement from the ANC to the EFF (from 2016 to 2019, and from 2019 to 2021), the reverse is not true; by our data, former EFF voters tend to either vote for alternative options (‘Other’), or not at all. Of course, the apparently poor voter retention in evidence among all parties may also be related to people voting differently in LGE than in National Elections.

The analysis of flows of voter preferences does not mean that party-loyalty is a defunct notion in South African politics. Instead, different parties retain their votes to significantly varied degrees. illustrates this by reporting the percentage of each parties’ 2021 voters (among youth) that voted for another party (thus, the DA, EFF or ‘Other’, and thus excluding ‘Too young to vote’, ‘Did not vote’ or refusals) in 2016, the previous LGE. Here we note that only 4% of ANC ‘youth’ voters cast their ballot for another party in 2016. This might be contrasted with the DA and EFF, where respectively 24% and 35% of their 2021 voters had supported another party in 2016. Regarding the shifting of support between LGE, the most significant changes are seen among voters for smaller parties (including, notably, the newly formed ‘Action SA’), where over half of their 2021 votes came from voters whom had voted for the ANC, DA or EFF in 2016.

Discussion

As our analysis has demonstrated, young voters cannot simply be classed as voters or non-voters, there is fluidity between these positions, and it is therefore important to analyse voting behaviour as a dynamic phenomenon. What emerges from our data is that there is a cohort of youth that can be described as loyal voters as well as a cohort of consistent abstainers. However, the analysis also reveals two further categories, those of casual voters and what we call party-loyal abstainers. We now discuss each of these categories in further detail.

Loyal voters

As a rule, political parties generally receive their support from people who voted for them in the previous election (Verba and Nie 1972), and expectations regarding loyalty by-and-large bear out in the empirical case of the South African 2021 LGE. Deep-rooted reasons for voting, or inertia over motivations, may help explain the phenomenon of party loyalty or voting habituality, as discussed by Fowler (Citation2006), Plutzer (Citation2002), harking back to Verba and Nie (1972). Our analysis illustrates that about a quarter of youth voters were party loyal over the last three elections with over a third of ANC youth voters stating that party loyalty was the reason for their vote choice. Thus, by-and-large regardless of parties’ appeals, membership strategies, and other attempts at fostering external political socialisation, a population may be said to consist of firstly ‘regular voters’, who are generally consistent in their electoral preferences, and secondly of ‘persistent non-voters’ (Miller, Shanks and Shapiro Citation1996).

Consistent abstainers

Abstention is clearly the most common voter behaviour among the youth, a trend that is witnessed in South Africa and elsewhere in the world. Across the globe, election turnout is falling (Kostelka and Blais Citation2021) to a degree that some see electoral democracy as approaching a crisis (Facchini and Jaeck Citation2019; Merkel and Kneip Citation2018; Papadopoulos Citation2013). Abstention is generally framed as an indicator of dissatisfaction or disillusionment with political options, or with party politics altogether (Auerbach and Petrova Citation2022; Ambrus, Greiner, and Zednik Citation2019). Regardless of the youth’s involvement in other forms of political participation, young people are the least likely cohort to vote (Bergan et al. Citation2022; Henn and Foard Citation2012). Relative to older cohorts, young people face more prohibitive barriers to voting (Plutzer Citation2002), while also tending to exhibit ‘a persistent gap between turnout intentions and turnout behaviour’. In other words, young people are also much less likely to follow through on their intent to vote than older citizens (Holbein and Sunshine Hillygus Citation2020). Regarding post hoc justifications provided for not having voted, we noted that administrative and individual barriers were the most common explanations.

Along with the growth of voter abstention has been speculation regarding how election outcomes might present should abstainers have voted (e.g. Shaw and Petrocik Citation2020; Umbers Citation2020, writing in the context of developed nations). However, we explained above that, for the South African case presented, when comparing the nationally representative intentions of would-be voters (most of whom abstain) and the actual votes cast, they remain in commensurate proportions, regarding relative support for the top four political parties. While this may not be significant in itself, it points to the value of introducing a third, new category, to the ‘loyal voter – serial abstainer’ binary.

Party-loyal abstainers

While the intention to vote, as expressed by people before an election, does not always translate to actual voting on the day, this does not mean that people are necessarily party-apathetic. While some scholars argue that, as a rule, most people are politically apathetic (e.g. Zhelnina Citation2020); however, it is possible that in contemporary socially polarised times, politics and identity are more closely linked than before (and perhaps more so in postcolonial loci). Nonetheless, the dual phenomena residing in habitual voting behaviours, that of party-loyal voters and serial abstainers, imply the possibility of a Hegelian triad – sublating into a speculative third category, that of the party-loyal abstainer.

By comparing the SASAS data with the Election survey we can clearly see that the intention to vote does not necessarily convert into actual voting. Instead, we see a category of voters who identify with a party, but apparently without the intention to vote. This is underscored when we reflect upon that 16% of youth voters who had previously been loyal to the ANC in 2016 and 2019 opted not to vote rather than vote for an opposition party, what we call a party-loyal abstainer.

The Party-loyal abstainer (such as an ANC-non-voter) is somewhat analogous to a category like ‘Christian atheists’, where the nature of the absence is shaped by the very thing it omits. This phenomenon has been identified since the 1990s in cultural theory with Lacanian references to the rise in popularity of coffee without caffeine, beer without alcohol, ice-cream without fat, candy without sugar, smoking without nicotine, among other objects deprived of its substance (Žižek Citation2002). Such essence-less phenomena are seen at once as a perverse (in the Freudian sense) negation, while also part of the maintenance of a certain (in this case economic and moral) system, even by appearing to undermine it. Regarding the negation – the ultimate consequence of the pleasure principle is that the object of desire is somehow unattainable. Regarding the maintenance, as scholars (Von Holdt et al. Citation2011) have highlighted, while protests in South Africa often appear insurrectionary, they often reflect an entanglement with dominant party politics that may be more about ensuring a stake in the status quo than offering opposition to it, in effect playing a role in sustaining the social order. Thus, political identity must nonetheless be constructed – in fact, it cannot but be constructed – and so to be an ANC-loyal non-voter is to believe in the idea (l) of the ANC, but probably not in the actual contingent personnel of the present party. The prosaic effect of this category is that, had those who abstained in the 2021 elections voted, the overall outcome would have been by-and-large the same.

Casual voters

A final category, outside of the triad of loyal voters, consistent abstainers and party-loyal abstainers, is that of the casual voter. A fifth of the youth cohort who were eligible to vote in the last three elections could be described as such, either voting only once or fluctuating between abstention and voting. This highlights an under-discussed phenomenon within youth voters that highlights important elements of dynamic behaviour as young people move in and out of voting.

Conclusion

This article examined the dynamics of the youth vote in South Africa in the 2021 LGE and provided an analysis of youth voter trajectories over the last three election cycles. In so doing, we have engaged with the seeming paradox of loyalty and abstention theories – that, in general, people are socialised into political parties, and tend to remain loyal to these parties, while actual voting turnout seems to be declining around the world.

Among scholars of electoral behaviour, there is an almost universal appreciation for studying the choices of first-time and young voters at national and local elections. Examining patterns among first-time voters serves to identify the political orientations of the young demographic – a sizable cohort in the case of many developing countries – providing information about their political experience and orientation. Such patterns also intimate the shape of things to come, ostensibly foreshadowing the outcomes of future elections. This is especially true in places with youthful demographics where younger voters wield considerable (potential) power in shaping electoral outcomes, and has, just as in the global north, long overtaken older demographics as the largest voting bloc in the electorate. Nonetheless, barriers to voting disproportionately affect younger voters, resulting in their collective inability to fully realise the weight of their electoral power.

As South Africa’s ‘born-free’ generations have become eligible to vote, focus on the electoral participation or non-participation of young people in the country has increased. The youth – aged 18–34 – constitute nearly a third of the South African adult population, and thus their voting decisions are rightly anticipated to play a powerful role in shaping the country’s electoral politics.

Yet South Africa appears to ‘conform’ to the paradox presented by juxtaposing loyalty and abstinence theories – with its youth perhaps epitomising it – on the one hand, younger voters within metropolitan municipalities are more supportive of the ANC than older cohorts, while, on the other, less than 10% of newly eligible voters voted at all. Perhaps counterintuitively, a large portion of youth appeared to indicate allegiance to a party, while never turning out to vote on election day. This points not only to the role of barriers to voting, but, we suggest, to the vital nature of party-loyal abstinence, especially where election outcomes are relatively predictable.

In the South African case, young voters display a non-negligible degree of voter fluidity, switching between voting and abstention, and in switching party support among different political parties. In developing concepts from dynamic behavioural models of electoral turnout, we conceptualise a more dynamic way to analyse the South African youth electorate that goes beyond the binary of voter or non-voter. The concepts of loyal voters, casual voters, party-loyal abstainers and consistent abstainers provide a more nuanced view of youth voting behaviour. While we have developed these arguments solely in relation to the youth electorate, there is a strong basis upon which these concepts can be used to analyse the South African electorate at large.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Young voters are conceptualised differently across numerous different studies. South Africa's Youth Development Policy defines young people as aged between 14 and 35. While Statistics South Africa generally defines young adults as aged between 18 and 34 years. We adopt Statistics South Africa's approach as this better enables as to compare the youth to older generations.

References

- Ambrus, A., B. Greiner, and A. Zednik. 2019. “The Effects of a ‘None of the Above’ Ballot Paper Option on Voting Behavior and Election Outcomes.” Economic Research Initiatives at Duke (ERID) Working Paper 277.

- Auerbach, K., and B. Petrova. 2022. “Authoritarian or Simply Disillusioned? Explaining Democratic Skepticism in Central and Eastern Europe.” Political Behavior, 1–25.

- Bendor, J., D. Diermeier, and M. Ting. 2003. “A Behavioral Model of Turnout.” American political science review 97 (2): 261–280.

- Bergan, D. E., D. Carnahan, N. Lajevardi, M. Medeiros, S. Reckhow, and K. Thorson. 2022. “Promoting the Youth Vote: The Role of Informational Cues and Social Pressure.” Political Behavior 44 (4): 2027–2047.

- Blais, A., and J.-F. Daoust. 2020. The Motivation to Vote: Explaining Electoral Participation. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Dalton, R. 1999. “Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies.” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, edited by P. Norris, 57–77. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. J. 2013. Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Dimock, M. 2019. “Defining Generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z Begins.” Pew Research Center 17 (1): 1–7.

- Facchini, F., and L. Jaeck. 2019. “Ideology and the Rationality of Non-voting.” Rationality and Society 31 (3): 265–286.

- Ferree, K. E. 2006. “Explaining South Africa's Racial Census.” The Journal of Politics 68 (4): 803–815.

- Fowler, J. H. 2006. “Habitual Voting and Behavioral Turnout.” The Journal of Politics 68 (2): 335–344.

- Fowler, J., and O. Smirnov. 2003. A Dynamic Calculus of Voting. Chicago, IL: Paper read at Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting.

- Friedman, S. 2015. “Archipelagos of Dominance. Party Fiefdoms and South African Democracy.” Comparative Governance and Politics 9: 139–159.

- Gerber, A. S., D. P. Green, and R. Shachar. 2003. “Voting may be Habit-forming: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 540–550.

- Habib, A., and S. Naidu. 1999. “Election ‘99: Was There a ‘Coloured’ and ‘Indian’ Vote?” Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies 26 (2): 189–199.

- Habib, Adam, and Sanusha Naidu. 2006. “Race, Class and Voting Patterns in South Africa’s Electoral System: Ten Years of Democracy.” Africa Development 31 (3): 81–92.

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2012. “Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 47–67.

- Holbein, J. B., and D. Sunshine Hillygus. 2020. Making Young Voters: Converting Civic Attitudes into Civic Action. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Holdt, Von, K. Langa, M. Molapo, S. Mogapi, N. Ngubeni, K. Dlamini, and A. Kirsten. 2011. Insurgent Citizenship, Collective Violence and the Struggle for a Place in the New South Africa. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Independent Electoral Commission [of South Africa] (IEC). 2021. Voter Registration Statistics. https://www.elections.org.za/pw/StatsData/Voter-Registration-Statistics

- Jaime-Castillo, A. M., and G. Martínez-Cousinou. 2021. “Political Socialisation.” In Politicians in Hard Times, edited by Coller Xavier and Leonardo Sánchez-Ferrer, 69–87. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kostelka, F., and A. Blais. 2021. “The Generational and Institutional Sources of the Global Decline in Voter Turnout.” World Politics 73 (4): 629–667.

- Lappeman, J., P. Egan, and V. Coppin. 2020. “Time for an Update: Proposing a New Age Segmentation for South Africa.” Management Dynamics: Journal of the Southern African Institute for Management Scientists 29 (1): 2–16.

- Magalhães, P. C., P. Segatti, and T. Shi. 2016. “Mobilization, Informal Networks, and the Social Contexts of Turnout.” In Voting in Old and New Democracies, edited by R. Gunther, P. A. Beck, P. C. Magalhães, and A. Moreno, 64–98. New York: Routledge.

- Mattes, R. 2012. “The ‘Born Frees’: The Prospects for Generational Change in Post-apartheid South Africa.” Australian Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 133–153.

- Mattes, R., and I. Glenn. 2021. “South Africa: A United Front? A Divided Government.” In Political Communication and COVID-19, edited by D. Lilleker, I. A. Coman, M. Gregor, and E. Novellipp, 303–311. Johannesburg: Routledge.

- Medenica, V. E. 2018. “Millennials and Race in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 3 (1): 55–76.

- Merkel, W., and S. Kneip. 2018. Democracy and Crisis: Challenges in Turbulent Times. New York: Springer.

- Miller, W. E., J. M. Shanks, and R. Y. Shapiro. 1996. The New American Voter, 140–146. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nhlapo, M. S., B. A. Anderson, and M. Wentzel. 2017. Trends in Voting in South Africa 2003-2015. Pretoria: HSRC Press.

- Norris, P. 1999. “Introduction: The Growth of Critical Citizens?” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, edited by P. Norris, 1–31. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oyedemi, T., and D. Mahlatji. 2016. “The ‘Born-Free’ Non-voting Youth: A Study of Voter Apathy among a Selected Cohort of South African Youth.” Politikon 43 (3): 311–323.

- Papadopoulos, Y. 2013. Democracy in Crisis?: Politics, Governance and Policy. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Paret, M. 2016. “Contested ANC Hegemony in the Urban Townships: Evidence from the 2014 South African Elections.” African Affairs 115 (460): 419–442.

- Paret, M. 2018. “. “Beyond Post-Apartheid Politics? Cleavages, Protest and Elections in South Africa”.” Journal of Modern African Studies 56 (3): 471–496.

- Pickard, V. 2015. America's Battle for Media Democracy: The Triumph of Corporate Libertarianism and the Future of Media Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Plutzer, E. 2002. “Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth in Young Adulthood.” American Political Science Review 96 (1): 41–56.

- Resnick, D., and D. Casale. 2011. The Political Participation of Africa's Youth: Turnout, Partisanship, and Protest. No. 2011/56. WIDER Working Paper.

- Runciman, C., M. Bekker, and T. Maggott. 2019. “Voting Preferences of Protesters and Non-protesters in the South African Elections (2014-2019): Revisiting the ‘Ballot and the Brick’.” Politikon 46 (4): 390–410.

- Schulz-Herzenberg, C. 2019a. “The New Electoral Power Brokers: Macro and Micro Level Effects of ‘Born-Free’ South Africans on Voter Turnout.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 57 (3): 363–389.

- Schulz-Herzenberg, C. 2019b. “To Vote or Not? Testing Micro-Level Theories of Voter Turnout in South Africa’s 2014 General Elections.” Politikon 46 (2): 139–156.

- Seagull, L. M. 1971. “The Youth Vote and Change in American Politics.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 397 (1): 88–96.

- Selb, P., and S. Munzert. 2013. “Voter Overrepresentation, Vote Misreporting, and Turnout Bias in Postelection Surveys.” Electoral Studies 32 (1): 186–196.

- Shaw, D., and J. Petrocik. 2020. The Turnout Myth: Voting Rates and Partisan Outcomes in American National Elections. Boston, MA: Oxford University Press.

- Singh, S. P., and J. R. Thornton. 2019. “Elections Activate Partisanship Across Countries.” American Political Science Review 113 (1): 248–253.

- Strauss, W., and N. Howe. 1991. Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: Quill.

- Sweetser Trammell, K. D. 2007. “Candidate Campaign Blogs: Directly Reaching Out to the Youth Vote.” American Behavioral Scientist 50 (9): 1255–1263.

- Umbers, L. M. 2020. “Compulsory Voting: A Defence.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (4): 1307–1324.

- Verba, S., and N. H. Nie. 1987. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. University of Chicago Press.

- Zhelnina, A. 2020. “The Apathy Syndrome: How we are Trained not to Care About Politics.” Social Problems 67 (2): 358–378.

- Žižek, S. 2002. Welcome to the Desert of the Real!: Five Essays on September 11 and Related Dates. London: Verso.