ABSTRACT

The paper is an attempt at applying Samir Amin’s lens in the analysis of socio-economic development in Africa. Social and economic development in Africa has been substandard, largely because of the economic system followed and because effective structural transformation has not taken place – Samir Amin’s works explained what needed to be done to transform Africa (and the broader global south). It is in this context that the paper posits that post-colonial Africa has had to contend with disruptive socio-economic and political realities instituted by European colonialism, slave trade and inappropriate integration of Africa to the so-called global economy. The fundamental explanation for the poor socio-economic development in Africa is global capitalism, and one of the possible solutions is in Samir Amin’s delinking proposal as well as the restructuring of the African economies.

Introduction

The wave of political independence in Africa starts in earnest in the 1950s with Libya (1951), Morocco (1956), Sudan (1956), Tunisia (1956), Ghana (1957) and Guinea (1958). Earlier, much earlier, Liberia (1847) and before the wave of the 1950s, Egypt (1922) attained political independence. Ethiopia was never colonised. South Africa is relatively complex, but it is probably safe to place its political independence in 1994 – the year when apartheid formally ended. Many African countries became politically independent in the 1960s and 1970s. It is only Zimbabwe that attained political independence in the 1980s. It is in this context that the analysis in this paper focuses on 1960–1980 and 1980–2000 over and above examining each decade since the 1950s. It is important to study social and economic development over a longer period of time because socio-economic transformation does not happen speedily and there is usually a lag (as economists would say). Arguably, the results of the work of administrations that took over from colonial administrations started showing in the late 1960s onwards, with some exceptions (e.g. Zimbabwe, South Africa and South Sudan). There have been many studies that deal with socio-economic development in Africa during the 2000s and the later period, hence this paper focuses on the first five decades of political independence in Africa. It is also worth noting that the studies referred to mainly focus on economic development or economic growth in particular. As a disclaimer, because I have written about Samir Amin previously and about post-independent Africa, the paper focuses on some of Amin’s ideas. In any case, it is not feasible to exhaustively deal with Amin’s huge archive about Africa (and the global south) in a journal paper. Samir Amin has also published comprehensive autobiographies that capture his thinking and there are published interviews with and of him that clarify his views on many critical issues pertaining to Africa and the global south in particular.

The paper is an attempt to apply Samir Amin’s views and perspectives in explaining socio-economic development in Africa for the period under review. The focus is on some of Amin’s major ideas that are relevant for the period immediately after the political independence of many African countries. The paper draws from Amin’s perspectives in relation to socio-economic development, with a specific focus on Africa. The paper starts with providing brief background to its problematic (viz. post-independent development in early years of political independence in Africa). That is followed by the interpretation of development through Samir Amin’s lens, in the context of the early years of political independence. Before the conclusion, the paper discusses what could bring about inclusive socio-economic development in Africa.

The context

Among the critical issues is that political transformation of the 1960s and 1970s ushered in new energies during the first two decades of independence. There were robust efforts towards socio-economic development, largely shaped by nationalist agendas. In addition to issues highlighted above in the introductory section, socio-economic development remained a huge challenge because many of the post-independence African leaders rejected the market economy which they viewed as a colonialist system. They mostly embraced socialist and communist systems as the best possible path of socio-economic development which did not go down well with former colonisers. Hyden (Citation1983) makes a point that many countries in Africa during the first two decades of independence pursued what can be viewed as an ‘economy of affection’ where an indigenous form of economic and social organisation dealing with peasant production modes, governance, policymaking, and management issues were pursued. The ‘affection economy’ (not to be confused with socialism or communism) represents a system of support, interactions, and communications among groups connected by blood, kin, communities, and village affinities.

It could be argued that while the ‘affection economy’ could have served worthwhile needs such as basic survival, social maintenance, and development of the economy. It could also have been responsible for holding back development by procrastinating on changes in behavioural and institutional patterns capable of sustaining economic growth and social development. Fundamentally, however, is that the ‘economy of affection’ which was associated with socialist and communist socio-economic development approaches was going against the trend of capitalist accumulation and it was therefore frustrated by the powers that be of the times. This continues through the skewed distribution of political power globally. Decolonial scholars term this as the ‘global colonial matrix’ or ‘colonial matrix of power’, referring to power structures that limit prospects for socio-economic development in the global south because of the control that the West exerts on the global south. Samir Amin’s analysis took this into account, largely from a Marxist perspective, and he argued for delinking among other possible solutions to this challenge.

It is also worth highlighting that socio-economic success or failure of African countries depended on economic, political, legal, and social institutions of the time. Such institutions could have created incentives for investment and the adoption of technology for business to invest, and the opportunity to amass human capital for workers. In this view, discouraging such activities could have been responsible for stagnation. There is however sufficient literature and data that provide argumentation and evidence that external influence, neo-liberal dogma and structural adjustment programmes, among other issues that had little to do with discouraging any economic activities, are responsible for poorer socio-economic outcomes than what was expected at the eve of political independence. It is in this context, as indicated earlier, that this paper focuses mainly on the early period of political independence and attempts to apply Samir Amin’s lens as far as how could Africa advance wellbeing and ensure inclusive socio-economic development.

Among his critical development ideas was the categorisation of African economies into three macro-regions: Africa of the colonial economy, Africa of the concession-owning companies and Africa of the labour reserves (Amin Citation1972). This is written about in many other publications, including in Gumede (Citation2022). Samir Amin (as explained in Gumede Citation2022) categorised the eastern and southern parts of Africa as the ‘Africa of labour reserves’, western parts of Africa as ‘Africa of the colonial economy’ and the Congo River Basin (i.e. Congo Kinshasa, Congo Brazzaville, Gabon and the Central African Republic) as ‘Africa of the concession-owning companies’. The Africa of labour reserves included Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Malawi, Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Lesotho and South Africa. The Africa of the colonial economy entailed former French West Africa, Togo, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Gambia, Liberia, Guinea Bissau, Cameroon, Chad and the Sudan.

Another critical aspect from Samir Amin’s works that is relevant for this paper relates to the evolution of social formations in Africa. As explained in Gumede (Citation2022), Samir Amin makes a point that an

analysis of a concrete social formation must therefore be organized around an analysis of the way in which the surplus is generated in this formation, the transfers of surplus that may be effected from or to other formations, and the internal distribution of this surplus among the various recipients (classes and social groups) – a social formation is an organized complex involving several modes of production. (Amin Citation1976, 18)

African formations were integrated at an early stage (the mercantilist stage)Footnote1 in the nascent capitalist system … they were broken off at that stage and soon began to regress (and might not have been able to generate by themselves the capitalist mode of production because large-scale trade of pre-mercantilist Africa was linked with relatively poor formations of the communal or tribute-paying types).

Arguably, Samir Amin’s characterisation or categorisation of the different parts of the economy still holds today, and, as he demonstrated, some of the categories/characterizations overlap. Similarly, the structure of the African economy as captured in Samir Amin’s works still largely holds today. Therefore, changing the structure of the African economy is one of the critical answers for socio-economic development in Africa (as argued by many). In other words, even if other constraints such as low savings, low investments etc. were addressed, economies in Africa would not perform well enough and they are unlikely to sufficiently advance wellbeing. Indeed, policies – particularly social policies – can help. However, to ensure that economies in Africa perform well sustainably and to ensure that levels of human development sufficiently improve, the structure of the African economy should be reconfigured.

Africa’s socio-economic development

Although data and estimates are not perfect, and some have been critiqued, it is important to examine social and economic development through empirical data in order to have a better sense of the phenomenon or phenomena instead of only talking in broad terms about Africa’s socio-economic development. Samir Amin used data in his analysis of the various phenomena and to support his arguments, recommendations and activism. Indeed, it is important to be circumspect with some data and estimates.

In order to have a better sense of wellbeing, the Human Development Index (HDI) is commonly used. The HDI is a composite index that includes a measure of income per head, education and life expectancy. It is generally used as an indicator of the level of development for a country or a region or sub-region. In the analysis of the HDI, the focus is on Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The geographic focus on Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is generally used in many studies in order to acknowledge that North Africa is different from SSA, both in economic and political terms. In addition, ideologically and historically, Arab countries have pursued a different political agenda compared to SSA countries. This paper is not about such issues as it is mainly applying Samir Amin’s lens in understanding socioeconomic development in the early years of political independence in Africa with the view of advancing an argument of what could Africa do to improve socioeconomic development. Gumede (Citation2019) wrestles with the complex question of pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism.

indicates how selected development indicators have performed during 1950–1990 for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The HDI changed from 0.081 in 1950 to 0.185 in 1990 which is a relatively substantial improvement given how slowly HDI can change overtime. The increase in the HDI during 1950–1990 is as a result of improvements in life expectancy and educational attainment, both increased from 0.076 to 0.161 and 0.030 to 0.139 respectively. By implication, wellbeing improved relatively significantly during 1950–1990. More people in the various Sub-Saharan African countries received education and were increasingly living longer. It must be noted though that longevity (i.e. living longer) is not necessarily related to having education. The point that the HDI makes is that there were commendable improvements in access to education and in people living relatively longer. It would seem that longevity improved more than access to education. The HDI also improves when per capita incomes increase. Per capita income is a measure of standard of living. If income per head improves, it implies that the standard of living is improving.

Table 1. Sub-Saharan African development indicators.

As indicated earlier, data and estimates should be handled cautiously. The HDI, for instance, has been criticised by some who argue that it is not comprehensive. Others argue that per capita incomes are not a sound measure of the standard of living because it is based on income per head in average terms. There would be people who have very low or no income but a country’s per capita income could be increasing.

There were many countries in Africa that were still colonised during the 1950s. It is during the 1960s that countries in Africa were becoming politically independent. It would seem that substantial improvements from 1960 to 1980/1990 take place, immediately after African countries become politically independent. Improvements during 1980–1990 do not seem that significant. It can therefore be argued that the 1960–1980 period is the period with substantial improvements in Africa in terms of social and economic development as demonstrates.

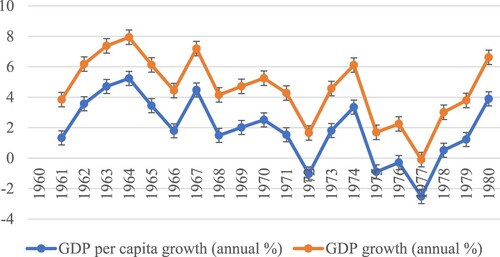

Figure 1. GDP growth and GDP/C growth rate trend (1960–1980). Source: Author’s plot based on the WDI dataset.

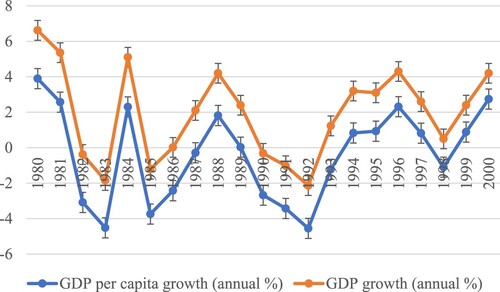

Both GDP and GDP per capita (GDP/C) have been improving since political independence in Africa but their growth has been fluctuating (see ). Hirsch and Lopes (Citation2020, 35) confirm what Mkandawire (Citation2001) had said that ‘during the first decade or so of independence, many African countries grew impressively, particularly considering their circumstances at the time of the transition.’ GDP/C however did not maintain the same consistency as the GDP, having shown a relatively small decline from 1516.392–1309,799 between 1980 and 1990 as shown in . It is not surprising that per capita incomes declined during 1980–1990. Economies in Africa took a while to recover from the oil crisis. Further, the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the 1980s and 1990s affected economic performance and development outcomes in Africa. confirms that economic crises of the 1970s and the subsequent structural adjustment negatively impacted economic performance and living standards.

Figure 2. GDP growth and GDP/C growth rate trend (1980–2000). Source: Author’s plot based on the WDI dataset.

Given that most of African countries attained political independence in the 1960s, the outcomes of their administrations at least as far as the economies in Africa are concerned, would have started to show in the 1970s and the 1980s. It is worth also examining the 1980–1990 and 1990–2000 decades because some countries got their respective political independence in the 1970s. Zimbabwe attained its political independence in the 1980s while South Africa is a late comer so to speak. Studying economic growth by region demonstrates that developing economies in Africa performed well above the global economy during 1970–80.

For 1990–2000, as shows, economic growth in developing economies in Africa performed at the same level as the global economy. The impact of the oil price shock in the 1970s and structural adjustment programmes in the 1980s resulted in African developing economies’ growth rate being below the level of the global economy during 1980–90.

Table 2. Annual average GDP growth rates, by region.

All developing economies combined have performed above the global average for the period studied (1970–2000). Developing economies in Asia have been the best performers and have ensured higher growth rates over all developing economies combined, resulting to growth performance above the global average for the period studied. The fundamental point the data is making regarding economic growth is that the economic performance of African countries (combined) was not as dismal during the immediate post-independent period as some claim. The Asian economic crisis and other economic crises negatively impacted many African economies in the 1990s. Therefore, the various economic crises account for the declines in economic performance in Africa during the post-independent era in general and particularly the 1980s. This worsened wellbeing in Africa, and structural adjustment programmes further weakened socio-economic development in Africa.

It is in this context that Samir Amin becomes relevant and insightful. The weakening of economies in Africa from the 1980s is largely linked to the global economy. In addition, it is linked to how Africa or African economies were integrated to the global economy. African economies have either continued declining in performance or have not recovered from global economic shocks of the 1970s and 1980s. There have since been more economic crises, and the great recession that started as a global financial crisis in 2007 further caused a deterioration in socio-economic development in Africa. As argued elsewhere, it is important to acknowledge the culpability of leaders in Africa and other factors that have contributed to the worsening socio-economic outcomes in Africa. Among such factors is the interference by external players in the affairs of African countries and or in the affairs of the African continent. Some of the leaders in Africa have not only allowed this but actively sought ‘partnerships’ with countries and leaders outside Africa at the expense of socio-economic development in Africa.

Samir Amin, underdevelopment and development

To start with, Samir Amin attributes the pattern of underdevelopment in Africa to global capitalism and its impediments (Amin Citation1997). It is important to highlight that Amin explains that capitalism is not just about the ‘generalized market’. It should be addressed in relation to power beyond the market because the logic of capitalism is inseparable from class struggle, politics and the state. As he put it, capitalism is a ‘regime in which the world economy functions in a hierarchical, unequal and exploitative way; where “first world” countries dominate and have developed at the cost of the Third World countries’ (Amin Citation2014, 16). The pattern of capitalist development that Amin writes about enabled ‘first world’ countries to resort to the mechanism of imperialist control of Third World countries of the South culminating to what he terms a ‘permanent phase of capitalism’ (viz. the globalised historical capitalism as being built up with no intentions to cease reproducing and deepening the polarisation of the centre-periphery relations). Indeed, capitalism continues to victimise people of the periphery by imposing direct control of the whole production system, where small and medium enterprises (and even the large ones outside the monopolies), like the farmers, were literally dispossessed, reduced to the status of sub-contractors, with their upstream and downstream operations, subjected to rigid control by the monopolies. This has ensured that African countries do not progress sufficiently, or that wellbeing as shown in the previous section remains weak and fragile in Africa.

There are those who have argued that development on the continent has been obscure because of the adoption of policies that are ineffective, the adoption of ineffectual sustainable livelihood strategies, as well as the notion that the erstwhile colonisers did not provide Africa with enough space to develop, but instead soon returned with new imperialistic inclinations such as structural adjustment policies, globalisation, and contract farming (Cheru Citation2009). Even if the correct policies were implemented, socio-economic development would still be constrained by the various factors, including those that Samir Amin so eloquently wrote about. Essentially, Africa has found it difficult to progress because it has been functioning within the mode of an economic system that constrains Africa’s development. In other words, global capitalism has not worked in favour of development in Africa.

As indicated earlier, Samir Amin also writes about contemporary Black Africa which can be separated into expansive regions that are distinctly dissimilar. There is traditional West Africa, there is the historic Congo River Basin, there is the eastern and southern regions of the continent. Indeed, the regions that Samir Amin wrote about still exist. It is not surprising that socio-economic development has not been impressive in Africa. Most parts of Africa and the regions that Samir Amin distilled have not changed much. Put differently, there has not been effective structural transformation of economies in Africa and the relationship that Africa has with the so-called developed world is still largely characterised by centre-periphery relations.

Because one of colonialism’s objectives has been to create markets for European commodities and natural resources, a connection between the African economy, the market as well as the global order, which has been under the control of, and managed by the colonisers, was required. This highlights the reason why African nations continue to be significant in the global economy. According to the Eurocentric ideology of westernisation, development of African countries remains elusive due to their scarce resources and productive base; overhyped national currencies; and the presence of massive and ineffectual public service bureaucracies that intrude in ‘purely economic matters’ (Erunke Citation2009) and the maintenance of subsidies in certain economic communities that ultimately overburden the state.

It is in that context that Samir Amin (Citation1990) argues that in order for development to take place within the continent of Africa and throughout the Third World, there is a pressing need to delink from the global capitalist system through the adoption of new marketing tactics and values that significantly differ from the ones of the so-called developed countries. According to Amin, it is possible for poor countries to achieve economic progress without necessarily adopting ‘rich countries’ production system approaches. Only by delinking economically from the industrialised nations and eliminating unequal exchange can countries in the periphery begin on a healthy path of growth and eventually exceed the established capitalist countries economically. Amin thinks that for Third World nations to realise the socialist structure and establish a new world economic system, independence is necessary. Self-sufficient development must be mass-oriented since only ‘mass’ development may result in a ‘national and self-sufficient economy’.

In short, delinking refers to ‘the strict subjection of external relations in all fields to the logic of internal choices without regard to the criteria of the world capitalist rationality’ (Amin 1990, 60). In addition, according to Samir Amin (1990, 55) delinking ‘is associated with a “transition” – outside capitalism and over a long time – towards socialism’. To be clear, Samir Amin (1990, 62) explains that delinking is not synonymous with ‘absolute or relative “autarky”, that is withdrawal from external, commercial, financial and technological exchanges.’ Samir Amin (1990, 62) is at pains to explain that delinking actually means

pursuit of a system of rational criteria for economic options founded on a law of value on a national basis with popular relevance, independent of such criteria of economic rationality as flow from the dominance of the capitalist law of value operating on a world scale.

In an interview with Ray Bush, published in the Review of African Political Economy (Amin and Bush Citation2014, 41:1), Samir Amin said

I understand delinking as compelling the dominant forces, imperialists, to adjust at least partly or to retreat, in two areas, political and economic. At the political level, delinking implies political solidarity between countries of the south to defeat the project of military control of the planet by the US, Europe and Japan. Second, at the economic level, there is an area where I think we could start moving ahead by dismantling the current global economic control. This is to move away from financialised globalisation – that is, not globalisation in all its dimensions, particularly trade, but controlling the flows of capital, including direct foreign investment, but also portfolio investments, speculatory investments and so on. (Amin and Bush Citation2014, 113)

Arguably, it is this major proposal of delinking that would have unlocked Africa’s development if it was pursued. It is very clear that the development of Africa is synonymous with equality as underdevelopment is with inequality; therefore, any quest towards achieving development in Africa would need to address the issue of inequality. Amin recognises that First World countries are growing at the expense of Third World countries, and the growth thereof is not equally distributed. Recognising that the capitalised system reduced countries of the periphery to being the subcontractors of central monopoly capita, and as a measure of addressing the issue of inequality for development, Amin emphasises the need for underdeveloped countries to move away from the capitalist system. He proposes socialism as an answer. It might very well be that Africa needs to come up with its own approach to socio-economic development, and not necessarily socialism. The fundamental point in Samir Amin’s delinking proposal is that Africa was wrongly integrated into the so-called world economy.

To elaborate briefly, delinking as used by Amin refers to the process of compelling imperialist countries to adjust to the needs or part of the need of Third World countries of the South, rather than Third World countries simply going along with having to unilaterally adjust to the needs of the First World countries of the North. According to Yong-Hong (Citation2013, 4) it is the ‘refusal to bow to the dominant logic of the world capitalist system’ by insisting for a change in the terms and not just the content of the conversation (Mignolo Citation2007, 459). The delinking strategy, as Samir Amin argued, is a type of revolution that liberates Third World countries from the grip of imperial power by transferring the economic hegemony to a new centre.

Samir Amin provides four propositions in justifying delinking: the first is that it is the logical political outcome of the unequal character of the development of capitalism. Unequal development, in this sense, is the origin of essential social, political and ideological evolutions. The second is that it is a necessary condition of any socialist advance, in the North and in the South. This proposition is essential for a reading of Marxism that genuinely takes into account the unequal character of capitalist development. The third is that the potential advances that become available through delinking will not guarantee certainty of further evolution towards a pre-defined socialism. Rather, socialism is a future that must be built. Fourth, the option for delinking must be discussed in political terms. This proposition derives from a reading according to which economic constraints are absolute only for those who accept the commodity alienation intrinsic to capitalism and turn into a historical system of eternal validity (Yong-Hong Citation2013, 5).

Amin’s argument for delinking highlights delinking from all forms of exploitation, arguing that unequal exchange is the main means whereby capitalism reproduces inequalities. He sees delinking as associated with a ‘transition’ – outside capitalism and over a long time- towards socialism, arguing that, contrary to orthodox belief, the ongoing economic growth crisis in the West and the perpetual development crisis in Africa is derived from the problem of capitalism (Amin and Bush Citation2014, 15). He argues that the situation in Africa of high prices, massive unemployment and stunted growth is a result of the structure of capitalism which is founded on the world capitalist law of value and its role in the accumulation of capital (Amin 1990).

Amin also stresses delinking from the strict subjection of external relations in all fields to the logic of internal choices without regard to the criteria of world capitalist rationality (Amin 1990). He argues that the concept of capitalism cannot merely be addressed in relation to the ‘generalized market’ but rather, need to be addressed in relation to power beyond the market because the logic of capitalism and inequality is inseparable from class struggle, politics and the state. Based on this, delinking is a process that would compel imperialist countries to adjust to the needs or part of the need of the South, rather than Third World countries simply going along with having to unilaterally adjust to the needs of the First World countries of the North (Amin 2018). Amin (2018) emphasises that African economies/countries should follow the Bandung spirit of the revival of the states and nations of Asia and Africa. In the Bandung Conference, which was a watershed moment in the history of countries in the periphery, African states and nations aligned with countries non-aligned to neo-colonialism whose rights had also been denied by the historical colonialism/imperialism of Europe, the United States and Japan in spite of the differences in size, cultural and religious backgrounds and historical trajectories. They, in solidarity and unity, rejected the pattern of colonial and semi-colonial globalisation that the Western powers had built to their exclusive benefit and declared their will to complete the re-conquest of their sovereignty by moving into a process of authentic and accelerated inward looking development inspired by Marxism on a socialist path, which was the condition needed for their participation in shaping the world system on an equal footing with the states of the historic imperialist centres.

In the 1970s and later periods, Samir Amin argued for the process of ‘delinking’ from all Eurocentric approaches to development – globalisation, adjustment programmes, contract farming, etc. in pursuit of home-grown alternatives. It is his earlier work and that of Thandika Mkandawire and others that have informed a view that Africa’s socio-economic development is constrained by inappropriate policies in the face of a hegemonic global political economy (Gumede Citation2013; Citation2015). Amin (2016) argued that in order to bring about effective development, Third World countries needed to ‘delink’ themselves from the global capitalist structure that promotes unequal development. Essentially, for Samir Amin, Africa needs to adopt market approaches and standards which are different from those in the developed world in order to achieve its own peasant-based futures. This could be accompanied by the promotion of prospects of autonomous industrialisation (Ndhlovu Citation2020). The approaches adopted need to promote the renewal of the peasant economy which was interrupted, distorted and disfigured by the imperialistic tendencies of the Euro-North which promoted coloniality through supporting the ascendency of comprador bourgeoisie puppets who would sustain its hegemonic rule at independence (Rodney Citation1972).

Inclusive socio-economic development in Africa

Many argue that the lack of robust socio-economic development on the continent is because Africa has not had its own indigenous theories which it has implemented for social and economic development. I have called for an alternative socio-economic development approach that takes into account the history, the initial conditions and the economic realities that many African countries face (see Gumede Citation2016). Hirsch and Lopes (Citation2020, 35) make a point that ‘the colonial period was mediocre for African economic development, and independence did not change the economic trajectory significantly.’

There has been too much talk but little on implementation. Scholars such as Samir Amin, Claude Ake, and Thandika Mkandawire, among many others, have been vocal about the need for inward-looking development. However, their contributions have not reached to a point of implementation by governments. This is not to say that other constraints such as those imposed by the global matrix of power are not frustrating socio-economic development in Africa or the global south broadly. This paper is not an analysis of global capitalism. Many others have done that, including Gumede (Citation2018).

Initiatives such as the Lagos Plan of Action, the Abuja Treaty, and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development, among others, remained ignored as potential concrete solutions. These different plans have also not been informed by any clear overarching framework that should be guiding inclusive development in Africa. As a result, there has not been a clear inward-looking socio-economic development agenda in and for Africa, although the African Union Agenda 2063 was a step in the right direction. The Agenda envisions an African future of unity, integration, prosperity, and peace (African Union Citation2013). Thus, by and large, Africa has mainly relied on borrowed theories and perspectives which, in most cases, do not speak to the context of culture and context of situations of the continent’s socio-economic needs.

As argued in the preceding section, one intervention that would most like have significantly improved socio-economic outcomes in Africa is Samir Amin’s notion of delinking. The one approach that can result to better socio-economic development in Africa was also pioneered by Samir Amin and popularised by other African scholars especially those associated with the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA). The approach referred to is based on the need for an agrarian revolution on the continent as part of Africa’s collective and continuous effort to pursue culturally context-specific development using its ‘own rules’. Claude Ake, Archie Mafeje and Sam Moyo are among those who elaborated this approach, largely based on the view that the majority of households in Africa directly rely on agro-based livelihood activities (at least in the 1970s/80s). Samir Amin’s agrarian revolution proposal points to the idea of designing and implementing inward-looking and ‘home-grown’ approaches that display a clear link between social and economic policies.

Many have argued for an alternative development approach (see Gumede Citation2016). Julius Nyerere, the former president of the Republic of Tanzania, proposed the Ujamaa not only as development model, but also as a political-economic management model (Nyerere Citation1967). The Ujamaa concept prohibited personal acquisitiveness and promoted the horizontally rather than vertically distribution of wealth throughout the society. Due to its positive results in terms of socio-economic development particularly for the rural poor, the approach gained widespread support, not only in Tanzania but also across the African continent where most post-independence governments focused on agricultural development than the rest of the economic sectors. Ujamaa was partly driven by affordability in terms of capital availability and sectoral expertise in land and agricultural activities by African communities.

The majority of post-independence governments were resource poor and therefore opted to begin their development agenda on agriculture mainly because already the general populace in the region would have had existing indigenous skills in agriculture, and not in the other economic sectors (Ndhlovu Citation2020). It was in this context that Nyerere introduced the villagisation of production which fundamentally collectivised all forms of local productive dimensions and, although it had its own challenges such a soil exhaustion, brought about improved household livelihoods outcomes. As a result, while the approach is criticised in some circles for land degradation as a result of over-cultivation near villages, the indigenous people who benefited from the programme itself supported it for its capacity to improve their socio-economic fortunes (Himmestrand Citation1994). In support of the Nyerere’s model, Erunke (Citation2009) argues that the alternative indigenous paradigm for development by post-independence African governments needed to place emphasis on the creation of conducive political, socio-economic environments and an effective resource mobilisation which could translate into sustainable development so as to guarantee the right balance between the private and public sectors of the economy in pursuit of a more useful approach.

The Pan-African and African concept and spirit gained momentum in the 1960s as African scholars and activists rallied behind the Organisation of African Unity to condemn domination, suppression, enslavement, and imperialism. The concepts gave birth to terminologies such as Africa’s rebirth, political liberation and sovereignty, regeneration, reconstruction, revitalisation, and reengineering. New terms such as re-Africanisation and re-membering should be added to the list. All these terms have been coined by African thought leaders as part of the continuous attempts to regain Africa’s values and identity on the global scene. Pan-Africanism, as an ideology of the revolutionary movement, was used to mobilise African countries to stand up and reconstruct themselves after a century of dehumanisation by imperialistic powers of the Global North. The founding fathers of Pan-Africanism argued that:

No independent African state today by itself has a chance to follow an independent course of economic development, and many of us who have tried to do this have been almost ruined or have had to return to the fold of the former colonial rulers. This position will not change unless we have a unified policy working at the continental level (Nkrumah Citation1963).

Conclusion

This paper revisited the post-colonial social and economic development in Africa, focusing on the period immediately after many countries gained political independence in Africa and making use of Samir Amin to explain weak socio-economic development in Africa. It posits that post-independent Africa has had to contend with disruptive socio-economic and political realities instituted by European colonialism. The fundamental explanation for the poor socio-economic development in Africa is global capitalism, and the main answer is in Samir Amin’s delinking proposal. Indeed, other constraints such as those imposed by the global matrix of power have to be acknowledged because they are limiting socio-economic development in Africa or in the global south broadly.

Based on what leading development thinkers in Africa have said, particularly Samir Amin, the paper proposes a major rethinking of development approaches with the intention to disregard imported development approaches which are not cognisant of the context and thus, do not relate to African socio-economic and political realities. A new development approach based on the pan-African agenda and Africa’s renaissance should be at the centre of an African future not designed by the continent’s colonial past.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 As Samir Amin puts it, ‘the mercantilist period saw the emergence of the two poles of the capitalist mode of production: the creation of a proletariat and the accumulation of wealth in the form of money’ (319).

References

- African Union. 2013. Agenda 2063 Vision and Priorities: Unity, Prosperity and Peace. Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Amin, S. 1972. “Underdevelopment and Dependence in Black Africa: Historical Origin.” Journal of Peace Research 9 (2): 105–120.

- Amin, S. 1976. Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formation of Peripheral Capitalism. New York: New Monthly Review Press.

- Amin, S. 1990a. Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World. London: Zed Books.

- Amin, S. 1997. Capitalism in the Age of Globalization. London: Zed Books.

- Amin, S. 2014. “Understanding the Political Economy of Contemporary Africa.” Africa Development XXXIX (1): 15–36.

- Amin, S., and A. Bush. 2014. “An Interview with Samir Amin.” Review of African Political Economy 41 (sup1): S108–S114. October. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2014.992624.

- Cheru, F. 2009. “Development in Africa: The Imperial Project Versus the National Project and the Need for Policy Space.” Review of African Political Economy 36 (120): 275–278.

- Erunke, C. E. 2009. Evolving an Alternative Theoretical Construct for African Development: An Indigenous Approach. Keffi: Nasarawa State University.

- Gumede, V. 2013. “African Economic Renaissance as a Paradigm for Africa’s Socio-Economic Development.” In Perspectives in Thought Leadership for Africa’s Renewal, edited by K. Kondlo, 436–457. Pretoria: AISA Press.

- Gumede, V. 2015. “Exploring the Role of Thought Leadership, Thought Liberation and Critical Consciousness for Africa’s Development.” Africa Development 40 (4): 99–111.

- Gumede, V. 2016. “Towards a Better Socio-economic Development Approach for Africa’s Renewal.” Africa Insight 46 (1): 89–105.

- Gumede, V. 2018. Inclusive Development in Africa: Transforming Global Relations. Pretoria: AISA.

- Gumede, V. 2019. “Revisiting Regional Integration in Africa: Towards a Pan-African Developmental Regional Integration.” Africa Insight 49 (1): 97–117.

- Gumede, V. 2022. “Thandika Mkandawire and Samir Amin on Socioeconomic Development in Africa.” Journal of African Transformation: Reflections on Policy and Practice 7 (1): 130–142.

- Gumede, V. Forthcoming. “Social and Economic Development in Africa: Early Years of Political Independence.” In The Handbook of African Economic Development, edited by P. Carmody and J. T. Murphy. Cheltingham: Edward Elgar.

- Himmestrand, U. 1994. Perspectives, Controversies and Dilemma in the Study of African Development. London: James Currey Ltd.

- Hirsch, A., and C. Lopes. 2020. “Post-colonial African Economic Development in Historical Perspective.” Africa Development XLV (1): 31–46.

- Hyden, G. 1983. No Shortcuts to Progress. London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.

- Mignolo, W. D. 2007. “Delinking.” Cultural Studies 21 (2): 449–514.

- Mkandawire, T. 2001. “Thinking About Developmental States in Africa.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 25 (3): 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/25.3.289.

- Ndhlovu, E. 2020. “Decolonisation of Development: Samir Amin and the Struggle for an Alternative Development Approach in Africa.” The Saharan Journal 1 (1). National Institute for African Studies (NIAS).

- Nkrumah, K. 1963. Africa Must Unite. New York: Praeger.

- Nyerere, J. 1967. Freedom and Unity, Uhuru na Umoja: A Selection from Writings and Speeches 1952–1965. London: Oxford University Press.

- Rodney, W. 1972. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Washington, DC: Howard University Press.

- Yong-Hong, Z. 2013. “On Samir Amin’s Strategy of Delinking and Socialist Transition.” International Journal of Business and Social Research (IJBSR) 3 (11): 101–107.