ABSTRACT

In Germany about half of the adult learners who start second chance education drop out before graduation. In this paper we aim to contribute to an explanation for this low success rate. We focus on the normative expectations of learners: What are their expectations concerning teachers’ attention to their personal abilities, teacher support and the recognition of their needs, and to what extent are these expectations met by teachers? Our main assumption is that the greater the difference between learner’s expectations and teacher practice, the more likely learners are to become disengaged and be absent from school, and this may lead to school dropout in the future. We use a database of N = 420 learners in 7 randomly selected institutions of second chance education in Germany. Results show, that (1) on average, adult learners tend to expect teachers to take an interest in their personal problems and to take responsibility for their learning process. However (2), 30% of learners experience teachers who are a) more or b) less learner-oriented than they expected them to be, and (3) students in group (b) show considerably lower school engagement and higher absences than students in group (a). Results are discussed with regard to practical implications for second chance education.

1. Introduction

As a result of educational expansion, the proportion of a cohort which gains the eligibility to study has dramatically increased in all western societies in the last few decades (H. Hadjar & Uusitalo, Citation2016). In this process, returns to education at lower secondary level have declined, whereas returns to the eligibility to study have tended to remain constant (Schuchart and Schimke, Citation2019). In modern learning societies, new social stratifications have been created between the ‘“haves” and “have-nots” in the area of skills and qualifications’ (European Commission, Citation2001, p. 5). Against this background, we focus on second chance education which is offered to adults in order to catch up and gain the eligibility to study. Second chance education is an opportunity for adults who did not realise their potential and their ambitions in mainstream education, partly because of social barriers. Particularly in stratified systems, the access to and graduation from compulsory general education is strongly influenced by social and ethnic background (Buchmann & Park, Citation2009; Parker et al., Citation2016). This is especially true in Germany (Schneider & Tieben, Citation2011), where after primary education, pupils are tracked into academic school types that lead directly to the eligibility to study or non-academic school types that do not. In lower secondary education, upward mobility is a rare occurrence (Bellenberg & Forell, Citation2012). Later opportunities for graduates from non-academic education to upgrade lower secondary certificates are of vital importance to enhance their future life chances (Ross & Gray, Citation2005; European Commission, Citation2001; Ivanvic, Citation2015).

However, although at least some adult learners may have been simply kept away from academic education by selection barriers, this does not mean that they are well prepared to obtain the eligibility to study later in life. Adults who have been out of compulsory education for a number of years have special learning needs because they have to adapt to formal schooling and learning again. Moreover, steadily increasing proportions of graduates from compulsory education with the eligibility to study have increased the pressure on those without this eligibility to upgrade their qualifications. In most educational systems, this need is met by schools with a vocational orientation which give pupils who have just graduated from non-academic school types the opportunity to catch up and acquire the eligibility to study (Orr et al., Citation2017). For adults in Germany who did not take these ‘first chances’ and instead completed a course of vocational training and/or took up employment, there is a last opportunity to upgrade a school certificate via institutions of second chance education (Harney, Citation2016; Harney et al., Citation2007). Against this background, it is not surprising that at least some of the learners in second chance education can be characterised as a ‘vulnerable group’ (Glorieux et al., Citation2011), because they often had learning difficulties in secondary education and/or repeated a year as early as in primary education.

One question is whether second chance education is well prepared for this heterogeneous learning clientele. In Germany about half of the learners who start second chance education drop out before graduation (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019). In this paper we aim to contribute to an explanation for this low success rate. School dropout is often traced back to poor academic performance, a disadvantaged socioeconomic and cultural background as well as school-related factors (Ross & Gray, 2005; McNeal, Citation1999). However, we do not focus here on factors that have been analysed in previous research on dropout, and instead we try to develop a theoretical approach that refers to the socialisation function of schools and may be better suited to explain dropout among adults in second chance education. In particular, following Dreeben (Citation1968), we focus on the relationship between learners’ needs in relation to institutional demands,Footnote1 which are moderated by teachers. Our main question is: What are the learners’ expectations concerning teacher attention to their personal abilities, teacher support and the recognition of their needs, and to what extent can these expectations be met? Our assumption is that the greater the difference between learners’ expectations and teacher practice, the more likely learners are to become disengaged and be absent from school, and this in turn is strongly associated with school dropout in the future (Tinto, Citation1975; Vaughn et al., Citation2013; De Witte & Csillag, Citation2014). In the following, we describe second chance education within the context of the German school system (2.1) and our theoretical assumption (2.2), from which we derive our research questions (2.3). We then present our database (3) and the results (4), which we finally discuss (5).

2. Theoretical and empirical background

2.1. Second chance education in the context of the German school system

In Germany, in lower secondary education (years 5–10), early selection takes place based on achievement into distinct secondary school types (Hadjar & Gross, Citation2016) that lead directly to the eligibility to study such as the Gymnasium and the comprehensive school, and school types that do not such as the lower secondary school (Hauptschule) and the intermediate secondary school (Realschule). Pupils who drop out of school or obtain a non-academic qualification may later be motivated after finishing compulsory schooling to catch up and earn the eligibility to study at vocationally oriented schools in upper secondary education (Orr & Hovdhaugen, Citation2014). Adults who did not make use of these ‘first chances’ to obtain the eligibility to study have a final opportunity to upgrade a school qualification via institutions of second chance education (Harney, Citation2016; Harney et al., Citation2007).

In Germany, the term ‘second chance education’ refers to educational programmes that aim at adults with a minimum age of 18 who have already finished their school career and have completed a course of vocational training and/or taken up employment, served in the military or cared for a family for at least two years. Second chance education is not intended to be simply the continuation of compulsory education but should represent a new start. That is why participants must have been out of school education for a longer period of time (Harney, Citation2016). There are exceptions to this for students who obtained an intermediate qualification via non-academic second chance education directly after compulsory schooling, and these students can continue in second chance education in order to obtain the eligibility to study without having fulfilled the requirements mentioned above.

Nationwide standards concerning the admission requirements, duration, number of lessons and range of subjects have been set by the Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019; Harney, Citation2016). Differences between the federal states arise mainly with regard to the significance attached to particular institutions in the organisation of second chance education, namely adult education centres as part of further education (Volkshochschulen), and the classical institutions of second chance education such as evening schools (Abendschulen), and daytime schools (Kollegs) (Harney, Citation2016).

This paper focuses on daytime schools (Kollegs) and evening Gymnasiums (Abendgymnasien) which lead to the eligibility to study, and for this type of institution some statistics are presented (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019): In the 2016/17 school year 29,000 students attended 104 evening Gymnasiums and 67 daytime schools. Compared to the 2006/07 school year, these figures for schools indicate a slight increase (100 evening Gymnasiums, 66 daytime schools in 2006/07). Compared to compulsory academic education, the contribution of second chance education is small: In the 2016/17 school year it accounts for 0,8% of all institutions and 2,9% of all students. However, second chance education has a great symbolic significance: It offers adults the opportunity to upgrade their school qualifications irrespective of their previous school career (adults with any kind of qualification and previous school type affiliation can enter academic second chance education) and their economic situation (students at a day school and in their last year at an evening school are financially supported by the state).

One special feature of academic second chance education in Germany is that the curriculum and the final central exams are the same as in upper secondary education in academic school types such as the Gymnasium. Despite these similarities, there are considerable differences regarding the student body. The selection of students for the Gymnasium is based on ability and learning behaviour at primary school, whereas access to second chance education depends neither on a certain grade average nor the acquisition of a certain school leaving certificate. Moreover, against the background of the steadily growing number of graduates from compulsory and vocationally oriented education with the eligibility to study (Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, Citation2018; Käpplinger, Citation2009), the pressure on all students to obtain the eligibility to study is increasing, and the number of students who enter academic second chance education with precarious learning prerequisites has also increased (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019; Harney, Citation2016; Harney et al., Citation2007; Seitter, Citation2009). Koch (Citation2018) accordingly points to a change in the target group of second chance education from ‘gifted but disadvantaged adults’ to ‘adults with deficits’ (see also Jüttemann, Citation1991).

Therefore, second chance education in Germany faces the particular challenge of an academic school type that is attended by a significant proportion of learners with inadequate learning prerequisites who may have difficulty coping with academic learning requirements. Dropout rates of about 50% (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019) reflect the magnitude of this challenge. Since only little quantitative empirical research has been undertaken on second chance education (Boeren, Citation2018), not much is known about its learners (see for an overview Seitter, Citation2009) and their risk of dropping out. In the following, we focus on the norms and attitudes of learners, who probably do not fit the normative requirements of an academic institution, and this may be – together with inadequate learning prerequisites – a reason for the low success rates in second chance education.

2.2. Institutional demands, learner needs and teacher strategies

School produces normative orientations in pupils. In the sociological tradition dealing with educational institutions, the socialisation function of school was emphasised for a long time as its most important function (Bowles & Gintis, Citation1976; Dreeben, Citation1968; Parsons, Citation1959; Wexler, Citation1992). Following this tradition, schools introduce certain norm orientations to pupils in order to prepare them for the later demands of an adult society. Dreeben (Citation1968), building on Parsons (Citation1959), describes ‘independence, individual performance orientation, universalism and specificity’ as relevant normative orientations. These four orientations mean that pupils learn to ‘(1) act by themselves (unless collaborative effort is called for) and take personal responsibility for one’s conduct and accountability for its consequences; (2) perform tasks actively and master the environment according to certain quality standards; (3) recognise the right of others to treat them as members of categories, on the basis of (4) a few discrete characteristics, rather than on the full constellation of them that represent the whole person’ (Dreeben, Citation1968, p. 63f). In the following, we call these norms ‘universalistic-specific’. By contrast, so-called ‘particularistic-diffuse’ orientations towards the whole person in his or her actual life situation, with various interests and experiences, which are important in private contexts such as families or groups of friends, are undesirable and problematic in the school context. Whereas in private contexts people are therefore treated as ‘particular individuals’, in schools they are treated as ‘pupils’ (= specific part of a whole person), measured by the same performance standards (= universalistic) as everyone else. Due to the structural characteristics of schools (e.g., homogeneous age groups, one teacher for 30 pupils, grading according to performance), universalistic-specific norms are constantly required and thus generated as dispositions in children and adolescents.

If this structural-functionalist perspective is modified and linked to a pedagogical perspective, the needs of the pupils come into focus. Despite the superordinate validity of universalistic-specific norms in schools, pupils bring to interactive school situations ‘diffuse’ expectations based on the whole person (Helsper, Citation2004, Citation2010; Wernet, Citation2003). For instance, they confront teachers with the desire to be viewed as a person, and not simply as a pupil. The resulting contradictions between institutional demands and personal needs are constitutive factors for pedagogical actions. For instance, although affective neutrality is expected of pupils, they cannot avoid relating the actions of teachers to their own person (they may feel deeply hurt by a low grade), since teachers have a decisive influence on their educational future and thus on their life chances. Although pupils are expected to be independent individuals, in fact they depend on the help and support of teachers to fully achieve this independence in the future (Helsper, Citation2004). Furthermore, their willingness to engage in the universalistic-specific norms of school is limited for personal and family reasons (Helsper, Citation2010). Dreeben (Citation1968) pointed out that not all pupils have the cognitive resources and the social support that lead to the acceptance and adoption of the universalistic-specific norms expected in schools. Accordingly, some studies indicate that particularly at-risk pupils – pupils from disadvantaged and/or immigrant backgrounds and pupils with socio-emotional problems – depend more than other pupils on caring pupil-teacher relationships and socio-emotional support (Tardy, Citation1985; Tennant et al., Citation2015; Teuscher & Makarova, Citation2018). A further factor is that immigrant pupils may come from cultural backgrounds that place a higher value on collectivistic norms and therefore more easily come into conflict with the norms of independence and universalism in schools (Raeff et al., Citation2000; Rothstein-Fisch et al., Citation2009).

The contradictions between institutional demands and personal needs cannot be resolved, only dealt with (Helsper, Citation2004, Citation2010; Wernet, Citation2003). Teachers develop relatively stable strategies and practices with regard to when and how they give in to the socio-emotional needs and orientations of their pupils (ibid). Their selection of strategies is also influenced by the context, namely a) by the needs and prerequisites of a specific pupil body and b) by the school traditions and school-type-specific tasks and goals. For instance, the more teachers perceive their pupils as disadvantaged and at risk, the more they adopt strategies that tend towards the particularistic-diffuse pole (Reese et al., Citation2014; Weinstein et al., Citation2014). In the strongly stratified German system, the culture of academic school types is strongly based on institutional norms of independence, performance orientation, universalism and specificity, whilst in the non-academic school type ‘Hauptschule’ with a vulnerable pupil body and a non-academic curriculum, pupil-centred strategies with a particularistic tendency are traditionally employed (Kunter et al., Citation2005).

However, not all pupils can be satisfied at the same time and in the long run. For instance, mathematics teachers in disadvantaged schools who choose to make lower demands on norms of independence and performance orientation reject and exclude pupils who want to perform independently according to higher performance expectations (Straehler-Pohl & Pais, Citation2014). Thus, some pupils can experience a fit between individual needs and a teacher’s practice, and some pupils will tend to experience what we call a ‘mismatch of fit’. Generally speaking, the latter can occur in both directions: A) teachers who apply strategies with a particularistic-diffuse tendency may reject pupils who are not dependent on their personal attention and emotional support, and B) teachers who employ rather universalistic-impersonal strategies may reject pupils with greater personal needs. Since the choice of a teacher’s general approach in how to deal with contradictory situations is structured by contextual factors, it can be assumed that the extent of either type of mismatch depends on the context. For instance, a type A mismatch may be more typical of schools in disadvantaged contexts, and a type B mismatch more typical of academic contexts (Hadjar & Grecu, Citation2019; Helsper, Citation2010).

Our assumption is that a mismatch of fit can lead to disengagement and failure at school. Straehler-Pohl and Pais (Citation2014) show in their qualitative study on schools in disadvantaged contexts that disengagement can occur if pupils with more universalistic-specific orientations are exposed to teachers who act more according to the norms of dependence and affectivity. In contrast, pupils with greater personal needs in academic schools tend to feel disengaged and may even drop out of school if their teachers strictly follow universalistic-specific norm orientations (Hadjar & Grecu, Citation2019). However, there is another body of research which claims that a certain orientation towards a pupil’s needs is part of the professional competence of teachers, and a certain degree of pupil orientation is necessary to support school engagement and achievement by all the pupils. Studies show that the more teachers are emotionally supportive, the more pupils engage in school and the less likely they are to drop out of school (Göbel & Preusche, Citation2019; Teuscher & Makarova, Citation2018). Some results also indicate that whilst this is true for all pupils, at-risk pupils, pupils from socially disadvantaged backgrounds and immigrant pupils benefit most. From this point of view, the pedagogical contradictions described above can be overcome by a professionally managed practice of interest, caring and emotional support on the part of teachers. However, these studies give no findings on the question whether the effect of a rather learner-oriented (in our terms particularistic-diffuse) teacher practice on engagement and dropout applies to all pupils, and is therefore linear, or whether there is a limit to the positive effects of learner orientation.

2.3. Summary and research questions

The theoretical assumptions as well as the research cited apply to pupils at primary and secondary schools, hence to schools with much younger learners. Can this be a reasonable approach to understand the specific problems of second chance education? One principal characteristic of pedagogical situations that produces contradictions between personal needs and institutional demands is also present in second chance education: As in mainstream education, the actions of teachers are linked to the future of the whole person, since this is biographically the last chance to obtain a high-quality school leaving certificate and to improve future life chances (Harney, Citation2016; Harney et al., Citation2007). Whether this produces substantial experiences of a mismatch of fit on the part of the pupils and whether these are associated with engagement or disengagement from school will be elaborated in the following research questions.

1) Personal needs

Second chance education is chosen by a very heterogeneous learner body (Harney et al., Citation2007; Koch, Citation2018), and presumably learners with a low level of individual and family resources may be less willing to engage in universalistic-specific norms at school. However, as pupils grow out of adolescence, they become more able to control their personal needs (Helsper, Citation2004). Adults in second chance education who have a long history of formal school experience may therefore in general be better able to adopt the universalistic-specific norms of second education schools. Since little is known about the normative orientations of adults in second chance education, we ask:

1a) To what extent do learners in second chance education have universalistic-specific normative orientations?

1b) Are these orientations linked to individual and family resources and cultural background?

2) Mismatch of fit

The type of second chance education in Germany that leads to the eligibility to study is classified as an academic school type of general education and is therefore traditionally bound to institutional norms such as independence, performance orientation, universalism and specificity (Kunter et al., Citation2005). However, second chance education itself is traditionally committed to the concept of equality of opportunities in education, which implies attention and support for those from disadvantaged backgrounds and for those with precarious learning prerequisites as a result of a non-academic school biography (Koch, Citation2018). Teachers seem to react to the special challenges of second chance education by frequently adopting a combination of particularistic (learner-oriented) and universalistic (institution-oriented) strategies (Schuchart, Bühler-Niederberger, Sommer & Türkyilmaz, Citation2019). For instance, many teachers employ a more universalist-specific strategy including a strong orientation towards high performance standards, little importance attached to differentiating and supporting classroom measures and no consideration of the personal needs of the students. Nevertheless, at the same time some of these teachers are responsive to students, e.g., by allowing them to negotiate on grades. It is therefore unclear whether significant proportions of learners in second chance education experience a mismatch and if so, what kind of mismatch (Typ A or Typ B, see 2.2) this is. Therefore, we ask:

2a) Is there a mismatch of fit between the norms and expectations of learners and perceived practice by teachers?

2b) If there is a mismatch of fit, what kind is it?

2c) Is a mismatch associated with individual and family resources and cultural background?

3) The fit and school engagement/disengagement

Theoretically, a mismatch of fit should be associated with school engagement in the sense that pupils who experience a mismatch of fit may be less likely to be engaged in school and more likely to disengage and to drop out of school. Learners with a low level of individual and family resources and with cultural backgrounds that are rather distant from the majority culture may be most affected by the negative effects of a mismatch of fit. However, empirical findings are heterogeneous, and it is not clear whether the effect of normative expectations and perceived teacher practice is interactive (for instance, with either type of mismatch having a negative effect) or whether these are independent of each other, with a more particularistic-diffuse teacher practice having a positive linear effect on school engagement and a negative linear effect on school disengagement. If we find different types of mismatch, we ask:

3a) Are fit and different types of mismatch differently associated with school engagement/disengagement in institutions of second chance education?

3b) Is this associated with individual and family resources and cultural background of learners?

3. Method

3.1. Sample

The data collection took place in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), where evening schools (in this study: evening Gymnasiums) and daytime schools form the group of ‘Weiterbildungskollegs’. The German federal states differ widely with regard to the provision of institutions and the participation of students in academic second chance education. 31.6 per cent of all the institutions and 45.3% of all the students in academic second chance education in Germany are in NRW. These percentages are considerably larger than those in the federal state of Bavaria, comparable in terms of size, which has 6.5% of all the institutions and 7.6% of all the students. Thus, when compared with all the other federal states, academic second chance education has the greatest significance in NRW, and this justifies the selection of this federal state for data collection.

In December 2018 we collected data from pupils in 7 randomly selected schools of second chance education (65.3% in the first and 34.7% in the fourth semester of second chance education, 65% in a daytime school, 35% in an evening Gymnasium). 420 learners in tracks which lead to the eligibility to study participated, and answering the questionnaire took 45 minutes. On average, learners were 24 years old and 56% were male.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Normative expectations of learners and institutional demands

Our analysis focuses on a) the normative expectations of learners regarding the actions of teachers, b) their experiences in real school situations which involved these actions, and c) the differences between norms practised in schools and the expectations of learners. In order to measure the normative expectations, we developed a bipolar scale based on Dreeben’s four norms of performance orientation, universalism, specificity, and independence. The scale included 6 teacher-related items (alpha =.69), which were formulated in a particularistic-diffuse sense (e.g., ‘Teachers should pay attention to me as a person’) and a universalistic-specific sense (e.g., “Teachers should only pay attention to my achievements and progress). Learners were asked how much they expected teachers to take an interest in their personal problems, to take responsibility for their learning process and to consider personal circumstances when disciplining learners or when assessing their performance. Learners had to choose between 5 response categories. Higher values indicated a more universalistic-specific normative expectation (MW = 2.55, sd = .75).

A second scale was employed to capture the experiences of learners with teachers in school. In general, it matched the situations already described in the first scale and added situations that were slightly differently formulated, for instance, ‘Teachers pay attention to our personal problems’ and ‘I confide my personal problems to my teachers’ Response categories ranged from 1 (none of my teachers) to 5 (all of them). Higher values indicated that experiences tended to be more universalistic-specific. The scale contained 10 items with an alpha of .71, MW = 2.70, sd = .56.

The mismatch of fit (questions 2a – 2c) was measured in terms of the difference between the scores for experienced practice and normative expectations. Those who had a difference of more than 1 unit were assigned to the category ‘mismatch’. If respondents had higher values on the scale of normative expectations (= tendency for universalistic-specific expectations) than on the scale of experienced situations (= tendency for particularistic-diffuse experiences with teachers in school), they were assigned to the type A mismatch (expectations are less particularistic-diffuse than teacher practice). Respondents for whom the contrary was true were assigned to the type B mismatch (expectations are more particularistic-diffuse than practice).

3.2.2. School engagement and disengagement

Questions 3a and 3b refer to the predictability of the mismatch of fit for school engagement and disengagement. We used two outcome variables: First, in order to measure school engagement, we asked if learners had enjoyed going to school in the last 6 weeks (see also Fredericks et al., Citation2005). Response categories ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Learners tended to enjoy school (MW = 3.62, sd 1.01). Furthermore, we used days of absence as an indicator of how much a learner is disengaged from school and its demands (Teuscher & Makarova, Citation2018). Absence rates are high in second chance education in Germany (Bellenberg et al., Citation2019). The learners are adults and can therefore decide for themselves whether they go to school or not. However, a certain number of days of absence will lead to expulsion. Learners were asked ‘How many days have you missed school this term?’ 5 response categories were given (never, once, 2–5 days, 6–10 days, more than 10 days). Learners were on average absent from school on about 2–5 days in the current term (MW = 2.62, sd = 1.21).

3.2.3. Individual, family and cultural characteristics

We measured cognitive resources by the academic self-concept (for instance, ‘I am not gifted for school.’, 3 items, alpha = .72). The response categories ranged from ‘I strongly agree’ (1) to ‘I strongly disagree’ (4), MW = 2.03, sd = .66. A low level of individual resources was captured by the question ‘What could be the most likely reasons if you fail at school?’ and its answer ‘psychological problems’ (30%). We decided not to measure family and cultural resources in terms of ascriptive characteristics such as the family’s socioeconomic status or immigrant status but in terms of what these characteristics may mean for adult learners (processual characteristics). Pre-analyses also showed that ascriptive characteristics (for instance, immigrant status, parental school qualifications) were of no significance for dependent variables. Parents influence the success of their adult children by supporting them financially and emotionally (Roksa & Kinsley, Citation2019; Settersten & Ray, Citation2010). We capture this by the response ‘lack of parental support’ (10%) to the question ‘What could be the most likely reasons if you fail at school?’. The normative expectations of teachers in schools are part of norms rooted in a society that apply to some but not to all immigrant groups (Rothstein-Fisch et al., Citation2009). We capture this ‘distance from the mainstream culture’ by presenting learners with a bipolar scale with 7 response categories on aspects of daily life. Respondents were asked, for instance, if they took part in celebrations on only German festive days (public holidays) (1) or only non-German ones (7). The scale contained 3 items, higher values indicated a greater distance from the mainstream culture (alpha = .59, MW = 3.8, sd = .93). A last variable that we considered was age (MW = 24.29, sd = 4.25, Min = 18, Max = 54).

3.3. Statistical procedure

We answer questions 1a – 2c by presenting the distribution parameters and testing bivariate differences. In order to answer questions 3a and 3b, we estimate multiple-regression models.

4. Results

4.1. Personal needs

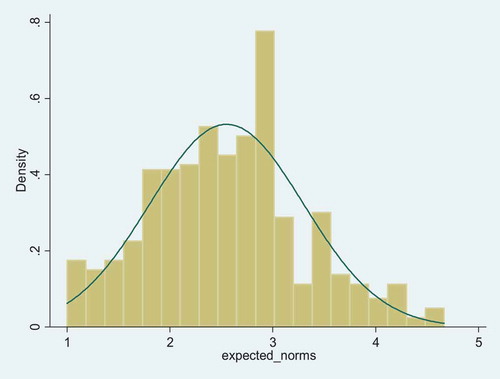

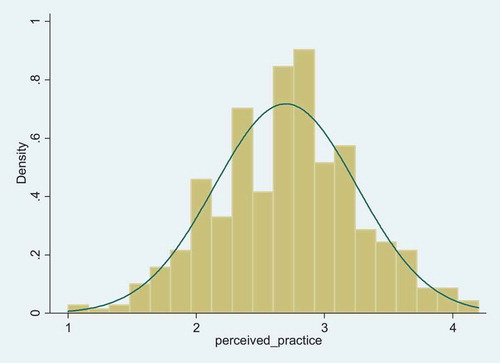

The average normative expectation of MW = 2.55 is slightly below the theoretical mean of 3, indicating that learners tend to expect their teachers to act in a way oriented towards their personal needs and circumstances. shows that the distribution is slightly left-skew (Shapiro-Wilk-test: W = 0.99, p = .003). Furthermore, learners perceive the practice of their teachers as neither clearly particularistic nor universalistic (MW = 2.70), with a slight tendency towards the particularistic-diffuse pole. The distribution is normal (, W = 1.00, p = .92).

Figure 1. Distribution of expected norms by learners in second chance education

Figure 2. Distribution of the perceived practice of teachers in second chance education

Normative expectations and perceptions are not independent of learner characteristics (). The more distant learners are from the mainstream culture, the higher their particularistic-diffuse expectations. This is also true the more they suffer from psychological problems, the less parental support they receive and the lower their academic self-concept is. Contrary to what we expected, age is not associated with the orientation of normative expectations. In the perception of teacher practice, there are significant correlations for the degree of distance from mainstream culture, academic self-concept, and age: The more distant learners feel from the majority culture and the less able they perceive themselves, the more they perceive teacher practice as universalistic-specific. However, the older learners are, the more they perceive teacher practice as particularistic-diffuse.

Table 1. Correlations between expected norms, perceived practice of teachers, and individual and family characteristics

4.2. Mismatch of fit

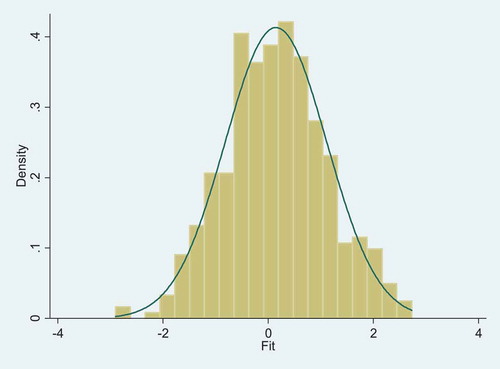

As explained in Section 3 (Method), we constructed a variable with three categories: the normative expectations fit the perceived practice, the perceived practice is more particularistic than expected (= type A mismatch), the perceived practice of teachers is more universalistic than expected (= type B mismatch), shows a normal distribution (W = .99, p = .67), with only a small minority of learners experiencing differences of larger than 2 units between practice and expectations. Learners who experience a type A mismatch or a type B mismatch differ most in normative expectations: The former have on average very high universalistic-specific expectations (MW = 3.70, sd = .45), and the latter have very low universalistic-specific expectations (MW = 1.67, sd = .42). Differences in perceived practice are smaller (type A: MW = 2.26, sd = .50; type B: MW = 3.24, sd = .41). In all, 70% of learners tend to experience a fit of practice and expectations, whilst 12% experience a type A mismatch and 18% a type B mismatch.

Figure 3. Distribution of the differences between experienced teacher practice and normative expectations

The experience of a mismatch of fit is associated with individual and family resources (). The lower the level of psychological, cognitive and family resources and the more detached learners are from the majority culture, the more likely they are to experience a type B mismatch than a type A mismatch, and to some extent a mismatch rather than a fit. There is also a tendency for older learners to experience a type A rather than a type B mismatch than younger learners.

Table 2. Mismatch of fit and individual and family characteristics (all variables standardised; MW)

4.3. The fit and school engagement/disengagement

Looking at , it can be seen that a mismatch of fit between normative orientations and perceived practice affects school engagement and absences. Compared to the experience of a fit, a type A mismatch is statistically associated with fewer absences, whilst a type B mismatch is associated with both lower school engagement and more absences. Therefore, learners tend to disengage from school if they experience universalistic-specific practice but expect teachers to be rather particularistic-diffuse. R2 is between .11 and .15, which corresponds to an effect of medium strength (Cohen, Citation2013).

Figure 4. School engagement, absences and mismatch of fit

Individual, family and cultural characteristics are associated not only with a fit and a mismatch of fit but also with school engagement and disengagement. In order to test the explanatory power of the concept of fit and mismatch, the variables used in questions 1a – 2 c are included in a multivariate regression model (, Models 1 & 3). For both school engagement and absences it can be seen that, controlling for individual and family characteristics, learners whose orientations are more particularistic-diffuse than their perception of teacher practice (Type B mismatch) are still more frequently absent from school and they enjoy school less. However, learners who perceive teacher practice as less universalistic than their expectations (Type A mismatch) do not differ regarding their engagement and their absences from learners who experience a fit.

Table 3. Regression of school engagement and absence on mismatch of fit, individual and family characteristics (all discrete variables standardised)

4.3.1. Interaction effects

We have shown that it is in particular younger learners and learners with lower levels of individual and personal resources and with a greater distance from the majority culture who tend to have higher particularistic-diffuse expectations and experience a type B mismatch. In order to determine whether the effect of a mismatch of fit interacts with these characteristics, we test interaction effects (not in the table). The results show no interaction effects except for age – older learners are more likely than younger learners to be absent from school if they experience a type B mismatch. In all, different groups of learners do not react differently to the perception of a mismatch of fit.

4.3.2. Linear effects of teacher practice

We outlined above that research findings for primary and secondary school children show that in general, the more pupil-oriented teachers are, the more pupils benefit from it. This is not consistent with our theoretical assumption that from the perspective of adult learners, teachers can also be too learner-oriented. We test the assumption of a linear independent effect of perceived teacher practice in Models 2 and 4 () by introducing into the model the linear measurement of teacher practice and in addition the linear measurement of learner normative expectations (instead of our categorial measurement of fit). While there is no linear effect of teacher practice on absences, we find a significant linear effect on school engagement: The more learner-oriented the perception of teacher practice is, the more likely learners are to be engaged in school. Furthermore, the stronger the universalistic-specific expectations of learners are, the more they are engaged in school. The absence of significant interaction effects (not in the table) of expectations and experiences indicates that the two variables tend to operate independently of each other.

5. Discussion

In this paper we were interested in whether the extent to which the normative expectations of learners and the normative orientation of teacher practice in second chance education can contribute to the explanation of school engagement and the absences of pupils and therefore to the poor success rates in second chance education.

First of all, our results indicate that adults in second chance education with a long history of formal school education are far from having clear universalistic-specific norm orientations. This means that learners tend to expect teachers to take an interest in their personal problems, to take responsibility for their learning process and to consider personal circumstances when disciplining learners or when assessing their performance. As expected, this tendency becomes stronger, the lower the level of individual and family resources and the more distant learners are from German mainstream culture. From the perspective of learners, the practice of ‘many’ teachers in these situations is rather learner-oriented, and this matches the expectations of 70% of the learners. This is in line with findings based on interviews with teachers at an institution of second chance education, which show that in order to deal with the needs of learners, more than half of the teachers combine particularistic and universalistic strategies (Schuchart, Bühler-Niederberger, Sommer & Türkyilmaz Citation2019).

However, 30% of learners experience teachers who are a) more or b) less particularistic-diffuse than they expected them to be, which we called a type A mismatch and a type B mismatch respectively. Second chance education does not seem to generate a certain kind of mismatch, although the proportion of learners who experience a type B mismatch is slightly higher. This is evidence of the contradictions that academic second chance education with a vulnerable learner composition has to deal with. Here too, learners are more likely to experience a type B mismatch if they have a lower level of resources and if they are more distant from German mainstream culture. Socially disadvantaged learners thus also have greater difficulty fitting into the learning context of second chance education. In contrast, the more resources learners have and the closer they are to German mainstream culture, the more they find teacher practice more particularistic-diffuse than expected. Although we assumed that both types of mismatch can decrease the likelihood of feeling engaged in school and increase the likelihood of being absent from school, we found significant effects only for learners who experienced a more universalistic-specific teacher practice than expected. Because of the close connection between school engagement, absences and dropout (see section 2), these learners are more likely to drop out in the future. This may also be true for particular groups of learners: For instance, the more distant learners are from German mainstream culture, the more likely they are to experience a type B mismatch and the more likely they are to be absent from school. This group partly corresponds to the category of students with an immigrant background, who have been shown to be more likely to drop out of academic second chance education (Bellenberg et al. (Citation2019). However, whether a learner feels distant or not from German mainstream culture is not simply related to the mere existence of an immigrant background, because further analyses show that the effect of ‘distance from mainstream culture’ on the perception of a mismatch is significant even if country of origin and/or language practice at home are controlled for.

For learners who experience a type B mismatch, there may be a greater risk of dropping out of school. This raises the question whether teachers and schools can do something for this group, which in our study accounted for about 20%. These learners had on average much stronger particularistic-diffuse expectations than their classmates. We must therefore ask whether teachers in second chance education, which in Germany is clearly required to follow the goals and the curriculum of academic education, can meet the needs of this group of vulnerable learners. Some studies show that preparing a vulnerable learner body for higher education is not necessarily contradictory (Athanases et al., Citation2016; Cochran-Smith, Citation2004; Woolley, Citation2009), but the emphasis is not so much on caring relationships as on the challenge of teaching academic standards. For instance, schools should involve learners in academically challenging work by offering learning activities that relate to their culture and context and thereby enable them to build on prior knowledge (ibid). In this way, the recognition of personal needs can be linked to academic standards but within the context of a learning activity. However, Athanases et al. (Citation2016) show that it is easier for schools to create a learner-oriented and at the same time study-oriented normative culture (for instance, by discussing the advantages of studying with individual students) than to establish academically challenging but learner-oriented practice.

There are some limitations of our study that must be mentioned. 1) Cronbach’s alpha was only moderate for the scales of normative expectations and teacher practice. Although there were no indications of a more complex structure with more factors, this might have become more apparent with a larger number of items. 2) Although the scales for normative expectations and teacher practice were matched in terms of content, there were differences in the response categories. In this respect, the recording of a mismatch in the sense of a difference between expectation and experience was not completely successful, and that may have distorted our results.

Our theoretical background suggested focusing on the interaction of normative expectations and the experience of teacher practice. However, further analysis of the data has suggested that the effects of normative learner expectations and teacher practice on school engagement may be rather linear: The more universalistic-specific a learner is, the more he/she is engaged in school. This raises several questions: First, to what extent is the acquisition of a universalistic attitude conditioned by the existence of family and individual resources and to what extent is it independent of this and can it be learned at school? According to our results, psychological problems and a weakly developed academic self-concept are particularly strongly linked to a low universalistic-specific attitude, and the consideration of the latter in the multivariate regression model weakens considerably the effect of normative expectations on school engagement and disengagement. Thus, a lack of individual resources increases the dependence of learners on teachers, and this may prevent learners from developing a more universalistic-specific attitude.

However, Parsons (Citation1959) and Dreeben (Citation1968) expect students to learn universalistic-specific attitudes at school. Since our data are not longitudinal in nature, we were not able to test this assumption. However, the fact that in our result older learners are less likely to experience a type B mismatch than a fit could be a slight indication that universalistic-specific attitudes can be learned. If schools want to contribute to making their pupils more independent in the sense of universalistic-specific attitudes, they will find that this is a complex task with limited probability of success. Working on learners’ psychological problems exceeds the competence of teachers and requires the involvement of counsellors and social workers. Teachers and counsellors should therefore be offered more training on interprofessional cooperation in order to be able to work together more successfully on behalf of the students (Niehoff et al., Citation2019). Teachers can also support their learners through constructive feedback that is sensitively communicated but nevertheless makes demands on them (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2005), because academic self-concept is recursively linked to performance, and teachers can influence it to a certain extent.

Second, does second chance education as an academic institution reward a universalistic-specific attitude of pupils, or is it rather the case that a learner with a universalistic-specific attitude becomes independent of the characteristics of the school context? The latter assumption is contradicted by the fact that all learners benefit from learner-oriented practice, regardless of their normative expectations. Universalistic-specific learners may pursue their goals in school more independently, but they also benefit from learner-oriented teacher practice. The effect of teacher practice on school engagement was much stronger than the effect of normative pupil expectations, which highlights the importance of the former. Since we did not measure the quality of teacher practice, we cannot say whether learner orientation is part of a professional strategy that also increases the motivation to learn and the academic achievements of learners and may hence in the end contribute to a more universalistic-specific attitude among learners. This would help them to achieve upward mobility, for instance, by entering higher education (Alheit et al., Citation2008). Overall, therefore, the particular challenge for second chance schools seems to be to guide pupils with high expectations of learner-oriented teaching practice in a way that allows them to take greater responsibility for their learning process and their goals.

Although the present study was conducted in Germany, the significance of its findings is not limited to Germany. In many countries, there are non-traditional pathways to higher education for adult learners, such as second chance education (for instance, European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, Citation2018, p. 174f). Our findings indicate that students in these pathways often belong to a ‘vulnerable group’ (Glorieux et al., Citation2011; Ross & Gray, Citation2015 for Australia; Marcotte, Citation2012; Looker & Thiessen, Citation2008 for Canada) which we have shown has specific educational needs and expectations regarding teacher practice. In future studies, however, it should be investigated which of the many international variations of these pathways offer the most favourable conditions to enable also vulnerable learners to achieve the eligibility to study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claudia Schuchart

Claudia Schuchart is professor of educational sciences at the University of Wuppertal.

Doris Bühler-Niederberger

Doris Bühler-Niederberger is senior professor of sociology at the University of Wuppertal.

Notes

1. We follow a sociological understanding of learners’ needs and institutional demands which is outlined in detail in section 2. This approach must be distinguished from the concept of supply and demand and its significance for program planning as discussed in adult and further education (for instance, Sork, Citation2010).

References

- Alheit, P., Rheinländer, K., & Watermann, R. (2008). Zwischen Bildung und Karriere. Studienperspektiven „nicht-traditioneller Studierender”. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 11(4), 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-008-0051-1

- Athanases, S. Z., Achinstein, B., Curry, M. W., & Ogawa, R. T. (2016). The promise and limitations of a college-going culture: Toward cultures of engaged learning for Low-SES Latina/o youth. Teachers College Record, 118(7), 1–60. https://education.ucdavis.edu/sites/main/files/file-attachments/athanases_tcr_college-going_cultures.pdf

- Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung. (2018). Bildungsbericht 2018: Bildung in Deutschland 2018. Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Wirkungen und Erträgen von Bildung. wbv Media.

- Bellenberg, G., & Forell, M. (2012). Schulformwechsel in Deutschland: Durchlässigkeit und Selektion in den 16 Schulsystemen der Bundesländer innerhalb der Sekundarstufe I. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Bellenberg, G., Im Brahm, G., Demski, D., Koch, S., & Weegen, M. (2019). Bildungsverläufe an Abendgymnasien und Kollegs: (Zweiter Bildungsweg). Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

- Boeren, E. (2018). The methodological underdog: A review of quantitative research in the key adult education journals. Adult Education Quarterly, 68(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713617739347

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America. Education reform and the contradictions of economic life. Basic Books.

- Buchmann, C., & Park, H. (2009). Stratification and the formation of expectations in highly differentiated educational systems. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 27(4), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2009.10.003

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). Walking the road: Race, diversity, and social justice in teacher education. Teachers College Press.

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (First published 1988). Routledge.

- De Witte, K., & Csillag, M. (2014). Does anybody notice? On the impact of improved truancy reporting on school dropout. Education Economics, 22(6), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2012.672555

- Dreeben, R. (1968). On what is learned in school. Stars.

- European Commission. (2001). Second chance schools: The result of a European pilot project. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2018). The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Publications Office of the European Union

- Fredericks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P., Friedel, J., & Paris, A. (2005). School engagement. In K. A. Moore & L. Lippman (Eds.), What do children need to flourish? Conceptualizing and measuring indicators of positive development (pp. 305–321). Springer Science and Business Media.

- Glorieux, I., Heyman, R., Jegers, M., & Taelman, M. (2011). “Who takes a second chance?” Profile of participants in alternative systems for obtaining a secondary diploma. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 30(6), 781–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2011.627472

- Göbel, K., & Preusche, Z. M. (2019). Emotional school engagement among minority youth: The relevance of cultural identity, perceived discrimination, and perceived support. Intercultural Education, 30(5), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2019.1616263

- Hadjar, A., and C. Gross (2016). Education Systems and Inequalities: International Comparisons. Bristol: Bristol University Press

- Hadjar, A., & Grecu, A. L. (2019). Sekundarschulzweige als differentielle Sozialisationsmilieus und Schulentfremdung: Eine luxemburgische Mixed-Method-Studie zur Entfremdung vom Lernen [Secondary school tracks as differential socialisation milieus and school alienation: A Luxembourg mixed method study on alienation from learning]. Presentation at the 7th conference of the society for empirical educational research, Cologne.

- Hadjar, H., & Uusitalo, E. (2016). Education systems and the dynamics of educational inequalities in low educational attainment: A closer look at England (UK), Finland, Luxembourg, and German-speaking Switzerland. European Societies, 18(3), 264–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1172719

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

- Harney, K. (2016). Zweiter Bildungsweg als Teil der Erwachsenenbildung. In R. Tippelt & A. von Hippel (Eds.), Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung (pp. 837–855). Springer VS.

- Harney, K., Koch, S., & Hochstätter, H.-P. (2007). Bildungssystem und Zweiter Bildungsweg: Formen und Motive reversibler Bildungsbeteiligung [Educational system and adult education: Forms and motives of reversible educational participation]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 53(1), 34–57. https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2011/4386/pdf/ZfPaed_2007_1_Harney_Koch_Hochstaetter_Bildungssystem_Zweiter_Bildungsweg_D_A.pdf

- Helsper, W. (2004). Antinomien, Widersprüche, Paradoxien: Lehrerarbeit - ein unmögliches Geschäft? Eine strukturtheoretisch-rekonstruktive Perspektive auf das Lehrerhandeln. In B. Koch-Priewe, F.-U. Kolbe, & J. Wildt (Eds.), Grundlagenforschung und mikrodidaktische Ansätze zur Lehrerbildung (pp. 49–98). Klinkhardt.

- Helsper, W. (2010). Pädagogisches Handeln in den Antinomien der Moderne. In H. H. Krüger & W. Helsper (Eds.), Einführungskurs Erziehungswissenschaft: 1. Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Grundfragen der Erziehungswissenschaft (pp. 15–32). Budrich.

- Ivanvic, K. S. (2015). What can we learn from second-chance education programmes for adults to prevent ESL in younger generations? Early School Leaving: Training Perspectives, 219–240. http://titaproject.eu/spip.php?article154

- Jüttemann, S. (1991). Die gegenwärtige Bedeutung des Zweiten Bildungswegs vor dem Hintergrund seiner Geschichte. Beltz.

- Käpplinger, B. (2009). Der zweite Bildungsweg zwischen dem ersten Bildungsweg und der beruflichen Bildung. Hessische Blätter für Volksbildung, 3, 206–214. doi:10.3278/HBV0903W206

- Koch, S. (2018). Die Legitimität der Organisation: Eine Untersuchung von Legitimationsmythen des Zweiten Bildungswegs. Springer.

- Kunter, M., Brunner, M., Baumert, J., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Blum, W., Jordan, A., & Neubrand, M. (2005). Der Mathematikunterricht der PISA-Schülerinnen und -Schüler. Schulformunterschiede in der Unterrichtsqualität [Quality of mathematics instruction across school types: Findings from PISA 2003]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 8(4), 502–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-005-0156-8

- Looker, E. D., & Thiessen, V. (2008). The second chance system: Results from the three cycles of the youth in transition survey. Human Resources and Social Development Canada.

- Marcotte, J. (2012). Breaking down the forgotten half: Exploratory profiles of youths in Quebec’s adult education centers. Educational Researcher, 41(6), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12445319

- McNeal, R. B. (1999). Parental involvement as social capital: Differential effectiveness on science achievement, truancy, and dropping out. Social Forces, 78(1), 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/78.1.117

- Niehoff, S., Lettau, W.-D., Fussangel, K., & Radisch, F. (2019). Individuelle Förderung in der Ganztagsschule – Ein Anlass zur interprofessionellen Kooperation? Die deutsche Schule, 111(2), 188–205. doi:10.31244/dds.2019.02.06

- Orr, D., & Hovdhaugen, E. (2014). Second chance’ routes into higher education: Sweden, Norway and Germany compared. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 33(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2013.873212

- Orr, D., Usher, A., Haj, C., Atherton, G., and Geanta, I. (2017). Study on the impact of admission systems on higher education outcomes. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Parker, P. D., Jerrim, J., Schoon, I., & Marsh, H. W. (2016). A multination study of socioeconomic inequality in expectations for progression to higher education: The role of between-school tracking and ability stratification. American Educational Research Journal, 53(1), 6–32. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215621786

- Parsons, T. (1959). The school class as a social system: Some of its functions in American society. Harvard Educational Review, 29(4), 297–318. doi:10.4324/9781315408545-9

- Raeff, C., Greenfield, P. M., & Quiroz, B. (2000). Conceptualizing interpersonal relationships in the cultural contexts of individualism and collectivism. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 87(87), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23220008706

- Reese, L., Jansen, B., & Ramirez, D. (2014). Emotionally supportive classroom contexts for young Latino children in Rural California. The Elementary School Journal, 114(4), 501–526. https://doi.org/10.1086/675636

- Roksa, J., and P. Kinsley (2019) “The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students.” Research in Higher Education, 60(4), 415–436.

- Ross, S., & Gray, J. (2005). Transitions and Re-engagement through Second Chance Education. The Australian Educational Researcher, 32(3), 103–140.

- Rothstein-Fisch, C., Trumbull, E., & Garcia, S. G. (2009). Making the implicit explicit: Supporting teachers to bridge cultures. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(4), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.08.006

- Schneider, S. L., & Tieben, N. (2011). A healthy sorting machine? Social inequality in the transition to upper secondary education in Germany. Oxford Review of Education, 37(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.559349

- Schuchart, C., Bühler-Niederberger, D., Sommer, T. & Türkyilmaz, A. (2019): Between institutional Norms and individual Needs: School Culture in Second Chance Education. In Fernandez, K. (Hrsg): School Culture. Special Issue in Bildung und Erziehung 169(6), 549–559.

- Schuchart, C and Schimke, C. (2019): Is it Worth Catching up on a Higher School-Leaving Certificate? Alternative Pathways to University Entrance Qualifications and Their Labour Market Returns. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 71, 237–273.

- Seitter, W. (2009). Bildungsverläufe im zweiten Bildungsweg. Empirische Befunde der Teilnehmer- und Adressatenforschung. Hessische Blätter für Volksbildung, 59(3), 227–237. doi:10.3278/HBV0903W227

- Settersten, R.A., and B. Ray (2010). “What's going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood.” The Future of Children, 20(1), 19–41.

- Sork, T. J. (2010). Planning and delivering programs. In C. Kasworm, A. D. Rose, & J. Ross-Gordon (Eds.), Handbook of adult and continuing education (pp. 157–166). Jossey-Bass.

- Straehler-Pohl, H., & Pais, A. (2014). Learning to fail and learning from failure – Ideology at work in a mathematics classroom. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 22(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2013.877207

- Tardy, C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00905728

- Tennant, J. E., Demaray, M. K., Malecki, C. K., Terry, M. N., Clary, M., & Elzinga, N. (2015). Students’ ratings of teacher support and academic and social–emotional well-being. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(4), 494–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000106

- Teuscher, S., & Makarova, E. (2018). Students’ school engagement and their truant behavior: Do relationships with classmates and teachers matter? Journal of Education and Learning, 7(6), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n6p124

- Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543045001089

- Vaughn, M. G., Maynard, B., Salas-Wright, C., Perron, B. E., & Abdon, A. (2013). Prevalence and Correlates of Truancy in the US: Results from a National Sample. Journal of Adolescence, 36(4), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.015

- Weinstein, C. S., Tomlinson-Clarke, S., & Curran, M. (2014). Toward a conception of culturally responsive classroom management. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487103259812

- Wernet, A. (2003). Pädagogische Permissivität: Schulische Sozialisation und pädagogisches Handeln jenseits der Professionalisierungsfrage. Leske und Budrich.

- Wexler, P. (1992). Becoming Somebody: Toward a Social Psychology of School. Falmer Press.

- Woolley, M. E. (2009). Supporting school completion among Latino Youth: The role of adult relationships. Prevention Researcher, 16(3), 9–12.