ABSTRACT

Globally significant adversities have occurred, including the COVID−19 pandemic, which had an impact on all facets of society, such as the fields of employment and education. University students should be well-equipped with the skills, knowledge, and attitude required to adapt to and withstand employability challenges. A triangulation mixed-method approach was utilised in this study to measure and explore post-secondary students’ sustainable lifelong learning for future-oriented purposes. The study began with a quantitative phase to examine the relationship between the four self-regulated learning strategies and lifelong learning. A survey approach was utilised to execute the research among 152 university students in Vietnam. The results of structural equation modelling demonstrated a significant positive association between lifelong learning abilities and metacognitive knowledge, resource management, and motivating beliefs. Cognitive involvement, however, did not reveal a significant connection. Second, qualitative follow-up research with five undergraduates indicated students’ use of strategical (self-regulated learning strategies) and psychological preparation (self-understanding, adaptability, and flexibility) for the future. Significant implications were made for teachers and students in higher education to facilitate and enhance students’ lifelong learning abilities to cope with uncertainties prior to transitions.

Introduction

Numerous disruptions have occurred as a result of population shifts, the emergence of climatic problems, and technological replacement (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning UIL, Citation2020). In terms of the most recent shift, there has been a significant pandemic that affects human lifestyles, employment choices, and opportunities. Due to a lack of demand for labour, businesses and institutions reduced their human resource allocations. The COVID−19 pandemic, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) (Citation2021), caused a 7% decrease in people’s working hours in ASEAN nations. In addition, 4.7 million individuals in Vietnam lost their jobs due to the epidemic in the third quarter of 2021, while over half of the workforce reported experiencing greater job-related challenges as a result of the epidemic (Nguyen, Citation2021). To adapt to the rapid changes shortly, humans in this scenario need to be endowed with the skills and personalities necessary. Among other necessary skills, lifelong learning is essential for strengthening employability and promoting active citizenship through fostering the growth of abilities and creativity (UIL, Citation2020). In addition to the components of education, training, and career advice, lifelong learning is one of the reasons that motivate people to put their acquired knowledge into practice and gain the necessary credentials to participate actively in the job market and global society (ILO, Citation2021). Therefore, undergraduate students who will soon encounter difficulties need to be supplemented with lifelong learning in advance, since educating students about advancing their future abilities at the university level is crucial (Jõgi et al., Citation2015; Nguyen & Walker, Citation2016; Rieckmann, Citation2012).

Since the occurrence of the COVID−19 outbreak, self-regulated learning (SRL), in addition to lifelong learning, has emerged as a tool to support teaching and learning all over the world, and it needs to be further researched for potential future changes in the education sector (Carter Jr et al., Citation2020). Students with self-regulation and autonomy in the classroom are better prepared, which leads to the objective of lifelong learning (Cornford, Citation2002; Lüftenegger et al., Citation2012). There is a considerable body of research investigating the influence of SRL methods on students’ academic accomplishment (e.g. Becker, Citation2013; Dent & Koenka, Citation2016; McMillan, Citation2010), yet studies investigating the impact of these strategies on their lifelong learning abilities remain missing. Given the need for a study investigating this association as well as the preparation of college students for future employment in an uncertain context, the current study aims at addressing two goals to fill the gaps in the literature: (1) identify the SRL strategies that had significant connections with lifelong learning, and (2) investigate how students sustained their learning to prepare for education-to-work transition. A triangulation mixed-method research was undertaken, combining quantitative and qualitative data to provide an inclusive understanding of how students get ready for lifelong learning to deal with unpredictably presented factors. Through these investigations, this study offers useful advice to college instructors and undergraduate students on how to best utilise the resources and learning methodologies for students’ future transitions. In addition, the study will contribute to enriching the empirical studies of lifelong learning in Southeast Asia, given that this topic has received less attention from Vietnamese researchers compared to the number of scholars from other countries in the same region (Do et al., Citation2021).

Lifelong learning for an uncertain transition

Despite not having a precise meaning, the phrase ‘lifelong learning’ is commonly used in literature about higher education. The ability to remain adaptable in the face of uncertainty is what lifelong learning refers to (Kirby et al., Citation2010). Some characteristics of lifelong learning capacities include the ability to adjust to rapid change (Laal & Salamati, Citation2012), endure uncertainty, and be reflexive to varied circumstances (Edwards et al., Citation2002). Regardless of whether it is deliberate or accidental, lifelong learning should encompass all forms of instruction, including formal, informal, and non-formal (Candy et al., Citation1994), which means that besides official education, it is vital that students establish a habit of continuous learning in different situations.

Uncareful preparation while being at universities may lead to unsuccessful job applications and under-ability employment after graduation. Thus, knowledgeable candidates must develop generic skills prior to graduation, including critical thinking, generating fresh ideas from a conceptual framework that has been synthesised, and effectively expressing themselves in both written and spoken forms (OECD, Citation2008). To achieve these capabilities, the process of lifelong learning and ongoing education should be implemented in such a fast-changing and high-demanding world. Lifelong learning will become more vital as the need for skills evolves due to advancements in the global economy and technology, necessitating a continuous retraining process (Lauder, Citation2020), especially for those on the transition threshold. Nevertheless, results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) demonstrated that formal schooling did not ensure that students were prepared for lifelong learning skills (Labaree, Citation2014).

Self-regulated learning strategies

In addition to being a critical tool for academic performance, self-regulation or SRL is also crucial for human adaptation to change (Eisenberg et al., Citation2011). SRL is generally understood to be a process of self-direction that involves students being proactive in defining objectives and controlling their own motivations, behaviours, and cognitive processes (Zimmerman, Citation2013). Students gain additional academic and professional advantages by having strong SRL skills. Students who are adept at organising, self-reflection, and self-monitoring tend to score better on exams (Becker, Citation2013). Because of their enormous benefits, SRL skills must be developed for students in higher education. People frequently believed that university students already possessed SRL skills, but a significant portion of them was underprepared to handle difficulties, particularly when it came to autonomy and independence (Bjork et al., Citation2013).

Prior research identified cognitive, metacognitive, resource-management, and motivational capacities as the four key categories of learner self-regulation (Pintrich, Citation1999; Pintrich et al., Citation1991; Zimmerman & Pons, Citation1986) (see ). The ability of a student to use self-regulation techniques to govern their thinking process or engage in mental tasks is known as cognitive engagement (Reeve, Citation2012). This capacity encompasses elaboration, organisation, and rehearsal practices (Pintrich & De Groot, Citation1990; Zimmerman & Pons, Citation1986), and critical thinking (Pintrich et al., Citation1991). This approach is also thought to be a fundamental strategy for considering one’s learning and reflecting on the most effective learning style (Greene, Citation2015). Metacognition is known as the awareness of and control over one’s own thought processes (Ku & Ho, Citation2010). The planning, monitoring, and regulation of students’ abilities are referred to as metacognitive control and self-regulating methods (Zimmerman & Pons, Citation1986). Resource management means the capacity to control the existing means and environment of learners, which requires regulating both internal (effort, attention) and external (time, study environment) aspects (Pintrich, Citation1999). Motivational beliefs refer to the degree to which students value the material or skills they are acquiring, their perceptions of their efficacy, and the justifications they use for desiring to accomplish academic activities (Wolters & Rosenthal, Citation2000). Self-efficacy, task value beliefs, and goal orientation are the three main categories of motivational beliefs, according to Pintrich (Citation1999).

Table 1. Self-regulated learning capabilities and their component strategies (Pintrich, Citation1999; Pintrich et al., Citation1991; Zimmerman & Pons, Citation1986.).

Empowering sustainable lifelong learning through self-regulated learning

There was prior research demonstrating the impact of SRL strategies on lifelong learning. SRL was projected to be crucial for students’ lifelong learning ability in addition to its significance for academic accomplishment (Schunk, Citation2005). Furthermore, it was anticipated that planning, monitoring, and assessment procedures would help students perform better in their professional careers (Cornford, Citation2002). A significant association was discovered between SRL cognitive, metacognitive, and resource-oriented approaches and students’ academic results (Endres et al., Citation2021; van Den Hurk, Citation2006), implying a lifelong learning capacity later in their lives. A different perspective proposed that for students to become lifelong learners, they require more elements in addition to self-regulation and individual agency (Endedijk et al., Citation2014). There is controversy over the link between undergraduate students’ SRL and lifelong learning ability.

Upon their transitions to work, students were demonstrated to prepare themselves with vital skills and competencies. Graduates equipped themselves with networking skills with mentors, alumni, classmates, and supervisors (Popadiuk & Arthur, Citation2014). Besides, perseverance, writing and speaking foreign languages fluently, public speaking, project planning, and implementation, and the capacity to deal with stress and issues are among the competencies that facilitate students’ post-university transitions (Piróg et al., Citation2021). However, how students sustain their learning for education-to-work transitions, is among the issues that have received little research, given that sustainable lifelong learning is crucial for skills evolvement at this stage (Lauder, Citation2020). In terms of study sites and research objects, the country of Vietnam and Vietnamese students were excluded from much research on university-to-work transitions, even in studies involving various countries of origin (e.g. Popadiuk & Arthur, Citation2014). Besides the earlier studies that concentrated on exploring student competencies, there is a need for a study that examines the strategies students used to achieve those assets.

All things considered, by investigating the under-researched groups of students, this study contributed to earlier research and offered new insights into how lifelong learning habits were cultivated in higher education settings for the future employability of students. Moreover, it will provide institutions with practical implications for enhancing student experiences in utilising SRL strategies to make the best of preparation for college-to-work transitions.

The current study

The major goals of this study are to ascertain the connection between each SRL strategy component and university students’ capacity for lifelong learning as well as to examine their experiences using various strategies to prepare for the uncertain world of work. The research questions in this study that need to be addressed, given the indicated research objectives, are:

Among the four SRL strategies, which ones significantly affected the lifelong learning abilities of university students in Vietnam?

In this question, we hypothesised:

H1

There is a positive relationship between students’ Cognitive Engagement and Lifelong Learning.

H2

There is a positive relationship between students’ Metacognitive Knowledge and Lifelong Learning.

H3

There is a positive relationship between students’ Resource Management and Lifelong Learning.

H4

There is a positive relationship between students’ Motivational Beliefs and Lifelong Learning.

(2) How did university students in Vietnam sustain their learning for the education-to-work transition?

To answer research question 1, four hypotheses need to be tested, whereas a qualitative study was conducted to address research question 2.

Methods

There were two phases in this triangulation mixed-method investigation. The triangulation strategy refers to answering the study topic by utilising many data sources or theories to support it (Leavy, Citation2017) and contributes to the validity of a study (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). This study applied three kinds of triangulation approaches, including data, methodological, and investigator triangulation. While the qualitative phase focused on how participants sustain their learning for transitions from college to the workplace, the quantitative phase examined correlations between participants’ SRL strategies and their lifelong learning competencies. Structured equation modelling with partial least squares (PLS-SEM), a quantitative research method, was used in the first step to evaluate the hypotheses. PLS-SEM is appropriate for small sample sizes and may be applied to various degrees of the structural model and construct complexity (Hair et al., Citation2017). While the quantitative phase demonstrated correlations among variables through statistics, qualitative research provides insight into how people perceive their actions and interpret their experiences in their own words (Gall et al., Citation1996). In this case, a qualitative study is vital to offer an understanding of students’ experiential use of diverse preparation strategies in addition to a set of pre-designed statements in the first phase.

Participants and data collection

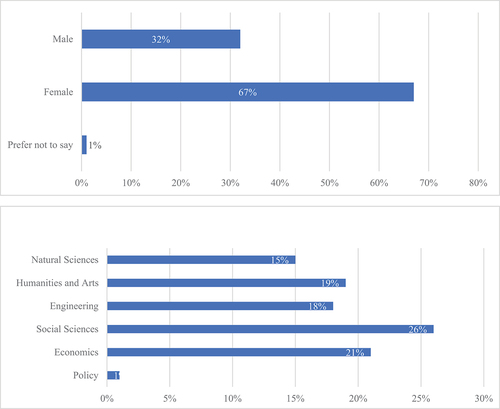

This study was approved by the researchers’ University Committee on Research Ethics. The quantitative phase employed a cross-sectional study to look at participants from different study majors at Vietnamese higher education institutions from the capital city which were situated with the most prominent universities in the country. The population included students from 18–22 years old, from first year to fourth year and above, who are studying in five big universities in Hanoi with the leading numbers of enrolled students each year for universities’ reputation in different majors. The G*power software determined the sample size. The anticipated sample size is 129 with an effect size of 0.15 and a confidence interval of 95%. Purposive and volunteer sampling methods were employed to gather data from university students in Vietnam enrolled in various academic programmes at various universities. Invitations with the survey form attached were posted by the first researcher on students’ virtual communities. The selected sites are five official Facebook groups of students’ communities whose names are ‘Students’ communities of the University of X” with an approval of an administrator who is currently a staff member there. In Vietnam, young people tend to spend more time on social networking sites (especially Facebook) compared to professional communication sites (Bich Diep et al., Citation2021) (e.g. email). Therefore, recruiting participants from the social networking community with purposive and volunteer sampling methods were chosen to achieve a higher survey response rate. Furthermore, using online questionnaires would allow for the recruitment of a large number of people from diverse backgrounds (Gall et al., Citation1996), which was also among the aims of the study. The online announcement reaffirmed that participants’ data would be kept confidential and solely utilised for research purposes. The online questionnaire then received 173 responses from students from five different universities in six main majors of study.

The instruments utilised in the quantitative study adopted two validated questionnaires that have been used successfully in post-secondary educational contexts. These two 5-point Likert Scale surveys were combined to assess students’ lifelong learning capabilities and SRL strategies. The first set of survey items was adapted from the questionnaire in Anthonysamy et al. (Citation2020)’s study about SRL strategies. The study’s modified questionnaire has 43 items spread over 4 categories, including resource management (9 items), cognitive engagement (7 items), motivating beliefs (6 items), and metacognitive knowledge (7 items). The authors’ collective group created the instruments using the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Pintrich et al., Citation1991). The second section of the survey form was modified from the 14-item Kirby et al. (Citation2010)’s lifelong learning questionnaire. Both aforementioned questionnaires were validated by the authors when going through a process of validity and reliability check which will be then presented in the data analysis section of this paper (). The combined questionnaire was provided to participants in English, in which the first researcher carefully evaluated the spelling and grammar to guarantee that it would not impair the participants’ comprehension and interpretation. The first researcher conducted a pilot test before distributing the survey form to participants, asking three students-two English majors and one non-English major – to confirm that they grasped the meaning of each item. In case there were any unclear statements, the first researcher made changes before asking the students to check the updated version once more.

Table 2. Participants’ information in the interviews.

Table 3. Internal consistency indicators.

Table 4. HTMT values of the constructs.

In the qualitative phase, the interviewees were intentionally selected by the authors based on the list of participants in the previous phase. Seniors and sophomores at Vietnamese universities were chosen, providing a range of academic and occupational backgrounds for the study. One participant had no prior work experience; all other participants were either part-time employees or independent contractors. Additionally, all participants were about to transition from studying to full-time working. A consent form had been signed by each informant before the interview was carried out. includes information about the participants. The interviews were carried out online using Zoom in Vietnamese, which was the interviewer’s and interviewees’ first language. For the sake of data accuracy, every conversation was audio recorded. Small talks and a relaxed tone were used purposely to ease the interviewers into the conversation and foster rapport (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017).

The interview guide in the qualitative study encompassed the questions related to students’ strategies of learning to prepare for the post-pandemic job market and other preparation students possessed to get ready for college-to-work transitions. Semi-structured interview questions allowed learners to reflect retrospectively and prospectively, revealing their opinions on their previous, current, and upcoming learning experiences. Each interview lasted about 30–40 minutes.

Data analysis

In the first phase of quantitative research, only 152 of the 173 qualifying responses were kept after data cleaning, even though a sample size of 129 was required. Then, using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 27, the questionnaire’s reversed items were recoded.

In PLS-SEM, internal consistency, known as convergent and discriminant validity, must be established in order to evaluate measurement models (Hair et al., Citation2021). A construct’s outer loading, also known as indicator reliability, determines a group of indications linked to the construct. According to Hair et al. (Citation2021), the indicators with factor loadings less than 0.4 should be eliminated; however, the outer loadings between 0.4 and 0.7 can be retained provided they have no impact on the fair values of average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). shows the retained indicators, and their outer loadings, CR, AVE, and VIF values. SMART-PLS software version 3 was utilised to run both measurement and structural models.

An instrument’s convergent validity is determined by calculating the outer loadings of the indicators to get the AVE from each construct (Hair et al., Citation2010). The convergent validity of that construct, according to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), is satisfactory if the CR is greater than 0.6, even when the errors are more than 60% or the AVE is under 0.4. All the CR values in are above 0.6 proving an acceptable convergent validity. A construct’s discriminant validity means that it is empirically distinct from other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2010). Compared to the cross-loading criterion and Fornell-Lacker criterion, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) has the most precise measurement for this kind of validity in PLS-SEM (Hair et al., Citation2017). When the path model’s constructs appear to be identical (‘cognitive’ and ‘metacognitive’), HTMT values less than 0.9 are acceptable (Henseler et al., Citation2015). In , all the HTMT values are well below 0.9, which proves the convergent validity of the model.

In the qualitative study, recordings and verbatim transcription of the interviews were permitted by the participants. The interviews were conducted in Vietnamese due to the preference of participants and then transcribed and translated into English by the first author. Then some excerpts of transcriptions were sent to interviewees to check whether they were content with these versions of translation. Atlas.TI software version 22 was used to analyse the five transcripts. The researchers began by carefully reading the interview transcripts, followed by preliminary independent coding. Pilot coding was conducted on the first two transcriptions to draw out the main themes. The inductively generated themes were determined by continuous comparison of the empirical data (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) and relevant conceptual ideas of SRL strategies. This shows an attentive engagement with the interview excerpts, theory, and critical readings of the quotations to evaluate how they connect with or diverge from the important conceptual tools coming from the literature. Thematic analysis, a flexible and effective research technique, provides a thorough and comprehensive interpretation of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Besides the theme of strategical preparation (SRL strategies), some codes emerged from interview excerpts that did not fit into this theme; accordingly, a theme of psychological preparation was created. The first researcher kept interviewing participants and analysing data at the same time, until there was no new data emerging from the interview transcriptions. The authors recognised that a category was saturated when no more new data was released by participants in each theme.

Findings

Quantitative findings: hypotheses testing results

illustrates the gender and academic major ratio of participants in the quantitative phase.

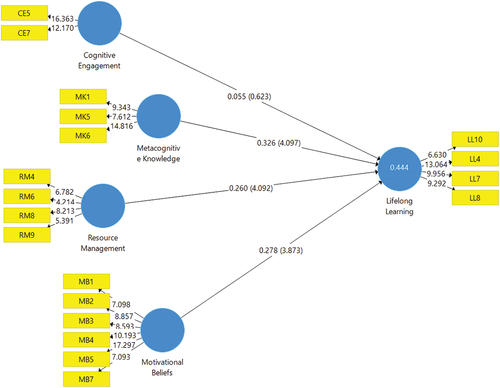

shows the research model after indicators for an acceptable level of internal consistency were removed. Following bootstrapping, the findings of the path analysis showed that there are statistically significant relationships between the outcome variable and metacognitive knowledge, resource management, and motivational beliefs. A significance level below 0.05 is present for all three predictors. Contrarily, the cognitive engagement construct has a level of significance of 0.533 (p > .05), which demonstrated that there was no association between this cognition and university students’ capacity for lifelong learning. Consequently, the three hypotheses with a positive tendency, H2, H3, and H4, were supported. The non-significant p-value allowed for the rejection of hypothesis H1. represents the hypotheses testing results.

Table 5. Hypotheses testing results.

Metacognitive knowledge emerges as the most significant indicator of lifelong learning competencies in this model, with a path coefficient of 0.326. Resource management comes in last, with a path coefficient value of 0.260, while motivating beliefs come in second, with a value of 0.278. The coefficient of determination R square should be considered when evaluating the indicators’ overall predictive possibility in a structural model (Hair et al., Citation2010). This model’s R square was 0.4439, suggesting that the four predictors of cognitive engagement, metacognitive knowledge, resource management, and motivational beliefs can explain 44.39% of the variation in a lifelong learning capacity. An R square greater than 0.44 can be regarded as considerable, according to Cohen (Citation1988).

Qualitative findings: strategical and psychological preparation for the future

The qualitative phase illuminated methods and strategies applied by a group of Vietnamese university students to sustain life transitions. Firstly, all students in the group underscored the effectiveness of SRL strategies in sustaining their learning processes for future purposes.

Strategical preparation for the future transition: using self-regulated learning strategies

To some extent, the knowledge and skills taught at university were updated and important for their future career, as Kim expressed ‘I find such academic knowledge to be completely sufficient and quite updated to be ahead of the future’. This also complied with the concept of ‘human capital’ in the graduate employability framework (Tomlinson, Citation2017), which refers to the knowledge and skills that graduates learn as a basis for their labour market results, as well as how graduates might build associations between their formal education and future jobs. Cognitive engagement and metacognitive knowledge included basic learning methods to facilitate their learning such as monitoring, regulating, or rehearsal was applied by informants to generally grasp the lessons at universities. The organisation of learning materials is utilised so that students can follow the flow of the lectures in classes. Managing the learning process by using some methods such as Pomodoro, is a way to ‘stay focused for effective knowledge acquisition for exams’ (Liam). Furthermore, to perform better in a specialised major in later life, which is individualised by each student, they chose to regulate their own agency to acquire more.

‘I choose to delve deep into other fields by updating information, reading on my own, taking courses, planning my own timetable to do all of those’.

The way they planned, monitored, and regulated their own time and habits illuminated an agency in preparing for a future rather than depending on others. Kim preferred independent studying to effectively maintain her pace: ‘If I study alone, I can set a goal of reading 20 pages a day’.

Help-seeking and peer learning help students find solutions for existing challenges in their learning process. Group work for peer learning practices has been reported to have its own benefits, including ‘increased work efficiency and prevention of procrastination by each team member’ (Paul). While completing their bachelor’s thesis, Grace and Sarah routinely wrote to instructors with questions ‘Teachers are always open to students’ questions, so I chose to ask my teachers’ (Grace). Help-seeking can prevent failure, sustain engagement, lead to task achievement, and raise the possibility of long-term mastery and autonomous learning (Newman, Citation2002). Paul also affirmed ‘I am eager to learn from the experiences of university alumni to check how they succeeded in developing a profession, as well as build up a relationship with them to collaborate on future projects’. The way students reached out to instructors and alumni can be understood as one way to develop ‘social capital’ which is described as the networks and interactions that enable graduates to activate their current human capital and get in touch with the labour market’s opportunity structures (Tomlinson, Citation2017).

Student motivational beliefs and learning methods are significantly connected to academic performance (Bembenutty & Zimmerman, Citation2003), as a result, help prepare students with competencies and attitudes needed for future employability. An informant expressed the belief in the importance of their study programmes, although the overloaded theoretical knowledge sometimes caused him stress.

‘Although some lessons are heavily theoretical while jobs in my major require something more practical, I have the belief that there will be something good for my career, so I still try to study it’.

When encountering difficulties, the first thing participants do is try to handle these issues by themselves. This demonstrates a high level of self-efficacy for task completion among informants. The ‘beliefs in myself’ attitude helped them overcome difficult tasks and establish a habit of being problem solvers as well as lifelong learners.

Meanwhile, task-values beliefs were emphasised by an informant when dealing with unfavourable activities:

‘Although I don’t like working in groups because it is hard to find a matching partner, I think it is good somehow to learn how to collaborate’.

The informant realised the value of the group work task which motivated her to self-regulate the learning process to acquire the necessary skills of collaboration for the future, despite her unfavorability of partner choosing. Different SRL strategies were found to be beneficial to assist participants in their lifelong learning process towards well-prepared competencies for the future world of work.

Psychological preparation for the future transition

In addition to the strategical methods that informants applied to sustain their learning, some psychological determinants were also mentioned as factors to maintain efficient preparation. Grace was in doubt about her future intentions. ‘My goal isn’t so obvious, I still have doubts about my future, maybe I’ll take a gap year ahead’, Grace remarked. Meanwhile, another informant expressed his opinion on the significance of understanding our true talent and demand. ‘If we are aware of what we need, we will be able to learn and act appropriately in each circumstance to prepare for an unpredictable occurrence in life’ (Paul). Understanding oneself drove students to cultivate their talents, such as seeking opportunities to capitalise on such strengths. A participant highlighted the importance of following one’s strengths to navigate the subsequent career trajectories ‘I am an energetic person, so I try to search for internship opportunities that involve communicating with others’, Grace supposed. Strength-based career model was recommended by career counsellors (Littman-Ovadia et al., Citation2014), thus, self-awareness is important for each student to facilitate their preparation for future employability.

To cope with changes in terms of societal demands or personal interests, flexibility and adaptability were identified for the successful transferability of each individual. Liam studied Computer Science at university but soon realised that he wanted to pursue a career in Economics 'This [study-work] mismatch came from the lack of orientation in my high school, my initial plan is to study for courses in economics on massive open websites, then I will decide whether to study for a second bachelor’s degree or not.’

Besides, Grace insisted that ‘My friends and I always have a plan B which is to teach IELTS when there is no opportunity in my favourite field [of curriculum developing]’. It was obvious that they were ready to be flexible and adaptive given the fact that the employment market and personal interests always change. These were the identity and psychological capitals of graduate employability which referred to the adaptive and self-aware ability of candidates (Tomlinson, Citation2017).

Discussion

Results suggested that there is a positive association between metacognitive knowledge, resource management, and motivational beliefs strategies of students. In addition, students sustained their learning using strategic and psychological preparation.

The results demonstrate that there is no significant connection between cognitive engagement techniques and lifelong learning (or H1 was not supported). Critical thinking and organisation skill are conventional learning methods, which correspondingly entails applying existing knowledge to address problems (Pintrich et al., Citation1991), and outlining appropriate information from learning materials (Weinstein & Mayer, Citation1986). Although cognitive practices such as understanding, learning, and remembering determine academically effective learners (McMillan, Citation2010), this study proves that these cognitive approaches do not provide students with many advantages for learning in the future, particularly when they face newly-emerging problems. Instead of cognitive learning, learners should be prompted to reflect on their learning processes (Carter Jr et al., Citation2020), and comprehend the reasons behind their own assumptions (Yundayani et al., Citation2021), which refers to the role of metacognitive methods.

The capacity of university students for lifelong learning is highly predicted by metacognitive knowledge (or H2 was supported). This finding echoed prior studies, implying that effective and long-term learners are especially characterised by learning-to-learn techniques and self-regulated learning (Kallio et al., Citation2018). Additionally, monitoring and planning help students become competitive in the workforce (Cornford, Citation2002). It appears that students’ ability to reflect on how and why they are learning, as well as their level of awareness of their actions and process, are enhanced by metacognitive strategies.

In the current study, resource management strategies include time management and study environment control, getting aid from others, effort regulation, and peer learning, all of which are found to be positively associated with lifelong learning (or H3 was supported). As a way of establishing sustainable lifelong learning, the previous study also supports the value of effort regulation (Kim et al., Citation2015) and peer evaluation (Malan & Stegmann, Citation2018). It makes sense that students who actively seek assistance from other sources do better over time since they get feedback on their learning process. The tactics for managing resources are also suggested as a way to lessen learners’ procrastination and distraction (Cornford, Citation2002; Pintrich, Citation1999); as a result, they assist learners to maintain the standard of their self-education process and their desire to learn despite unfavourable changes in the environment.

Self-efficacy, task value beliefs, and goal orientation are examples of motivational belief techniques that are also positively related to lifelong learning (or H4 was supported). This result is in line with previous motivational factor research, which demonstrated that self-efficacy and mastery goal orientation increased the potential for lifelong learning (Hee et al., Citation2019). The current study showed how lifelong learning is related to task-value beliefs, which indicates that if learners are aware of worthwhile assignments, they can be more motivated to complete them. Being high-task-value learners will benefit them in both their academic pursuits and professional endeavours as they will be more methodical and self-directed in accomplishing their goals (Lin, Citation2021).

The second aim of this study was to explore the preparation of students for forthcoming transitions. The qualitative investigation showed some alignment with the quantitative findings. The interviews’ data revealed a range of SRL techniques to keep the learning process going during crises and life transitions used by college students. Asking for help, controlling their time and space (resource management), arranging their study materials (cognitive engagement), organising, and recording their own learning processes (metacognitive knowledge), task-value beliefs, and goal-orientation beliefs (motivational beliefs) were among the strategies employed by participants. Autonomous and collaborative learning were flexibly used depending on the participants’ circumstances and activities; however, most respondents preferred independent learning and recognised its effectiveness. The results of the other earlier research revealed a discrepancy when students needed peer support and assistance from academic professionals to be well-performed in independent studies (Hockings et al., Citation2018). The difference might be attributed to an improvement in students’ abilities to learn independently since the appearance of discontinuous distance learning from 2020 to 2022. Contributing to the advantages of skills and professional growth (Lei & Medwell, Citation2021; Margaliot et al., Citation2018), collaborative learning in the current study was found to boost the efficiency of academic work and assist learners in overcoming procrastination.

To prepare for a smooth college-to-work transition under uncertain conditions, psychological factors such as self-understanding, flexibility, and adaptability were reported to play an integral role. Despite students’ efforts to prepare themselves with language, skills, or experience, when students were about to leave college and enter the workforce, there were uncertainties and anxiety, as shown by both quantitative and qualitative data. An informant experienced the difficulty of a mismatch between studies and employment as a result of a lack of orientation in secondary education and a failure to recognise his full potential, as he pointed out. When just 27% of undergraduate degree holders are employed in a position closely related to their college academic fields, this was not an uncommon occurrence among young people (Abel & Deitz, Citation2015). The student in this research decided to spend a few gap years strengthening his profile and preparing to transition to a different major, demonstrating initiative and agency in determining his own career decision. This kind of action resonated with an essential personal trait that was explained by Pham and Jackson (Citation2020), namely ‘agentic capital’. It was deemed the ability to develop strategies for effectively and strategically using various forms of capital depending on one’s cultural origin, areas of specialist knowledge, career aspirations, contextual factors, and personal attributes (Pham & Jackson, Citation2020). Besides, the feeling of doubt of students in the current study was in line with studies on task uncertainty related to the future in a group of German and Polish adult learners (Lechner et al., Citation2016), or American teens (Staff et al., Citation2010). These doubts may be caused by the lack of focus on career exploration in the classroom and the underestimation of the adult years as a time for role discovery (Staff et al., Citation2010). Students indicated the role of a strength-based career as well as awareness of oneself and his/her intention. Self-awareness is among the emotional intelligence competencies that include self-insight, self-understanding, and emotional information (Boyatzis & Boyatzis, Citation2008), which was considered crucial in helping students become more capable of overcoming obstacles in the future transition by higher education psychologists (Warrier et al., Citation2021).

Most importantly, students’ strategies in preparing for future uncertainty can be understood as attempts to develop graduate employability competencies in the model of Tomlinson (Citation2017), including human capital, social capital, identity capital, and psychological capital. Using SRL strategies as methods and employability capital as objectives, students tried to reach the goal of being lifelong learners for an effective transition. These findings concurred with other scholarship in the literature about the effort and recognition of preparation to navigate their own career trajectories (Jackson & Tomlinson, Citation2020; Tomlinson, Citation2008). Furthermore, this study contributed to those bodies of literature by identifying the four domains of SRL strategies learners use to ‘invest in the self’ for the education-to-work transition (Tomlinson, Citation2010, p. 1).

Conclusions and practical implications

The study looked at how SRL techniques affected students’ capacity for lifelong learning and how they maintained their education upon life transitions at Vietnamese higher education institutions. The qualitative data enhanced the quantitative figures by illuminating the interrelationships between variables. As a result, the model’s content validity was unaffected by the removal of some indicators in the quantitative model. PLS-SEM does not require a specific number of indicators for each construct, and it also successfully handles single-item constructs without any identification issues (Hair et al., Citation2021). Besides, three SRL dimensions are noted as having a substantial favourable impact on lifelong learning in the studies. Only cognitive engagement techniques have been proven to have no discernible impact on students’ capacity for lifelong learning. Thus, it can be inferred that to prepare students for the future by fostering a lifelong learning attitude in them, teachers, and students themselves should concentrate on promoting metacognitive knowledge, resource management, and motivational belief strategies. The qualitative findings aligned with the quantitative ones in which students took advantage of SRL strategies to sustain their learning process for future transitions. In addition to these, the study’s findings also identified the importance of students’ psychological factors and identity capital in promoting sustainable learning. The study illuminated the efforts of learners in applying different kinds of SRL strategies to achieve the objectives of graduate employability capitals and become lifelong learners throughout the preparation process. By examining the particular groups of participants, the study offered a useful implication for university teachers to incorporate useful activities as well as provide support in daily lessons so that students can have more chances to develop SRL strategies and obtain strong virtues of self-understanding, adaptability, and flexibility.

Limitations and future recommendations

There are still certain restrictions on the research design. Due to the relatively small sample size (152 participants) and non-probability sampling approaches used in the quantitative phase, it is not recommended that the results be generalised to a wider population. Similarly, the qualitative sample size is rather small, consisting of five individuals, accordingly, to gather more viewpoints on sustainable learning approaches, more interviewees should be recruited for future studies. Even though the study seeks to identify the learning styles and competencies of students from various regions of Vietnam, it mostly reaches participants from urban areas in the North. The research locations can be expanded to include additional regions, particularly understudied regions in distant areas in Vietnam (e.g. Central Highland or Northwest Vietnam) or worldwide. It is suggested that other researchers conduct longitudinal studies before and after graduation of university students to examine more precisely the causal relationship between students’ learning strategies and lifelong learning abilities over time.

Authors contributions

Huong Lan Nguyen, MA, gained her master’s degree in the field of Education at the University of Eastern Finland, Finland. Her research interests include education-to-work transition, career exploration and career decision-making, and teaching and learning in higher education.

Dr. Maryam Zarra-Nezhad is a postdoctoral researcher in the field of Psychology at the School of Applied Education Science and Teacher Education, Philosophical Faculty, University of Eastern Finland, Finland. Her research interests are early childhood social and emotional well-being, peer relations, and parenting relationships.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the research, anonymous reviewers, and the journal’s editors for their constructive comments on different versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abel, J. R., & Deitz, R. (2015). Agglomeration and job matching among college graduates. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 51, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2014.12.001

- Anthonysamy, L., Koo, A. C., & Hew, S. H. (2020). Self-regulated learning strategies in higher education: Fostering digital literacy for sustainable lifelong learning. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 2393–2414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10201-8

- Becker, L. L. (2013). Self-regulated learning interventions in the introductory accounting course: An empirical study. Issues in Accounting Education, 28(3), 435–460. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50444

- Bembenutty, H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2003). The relation of motivational beliefs and self-regulatory processes to homework completion and academic achievement.

- Bich Diep, P., Minh Phuong, V., Van Chinh, N., Thi Hong Diem, N., & Bao Giang, K. (2021). Health science students’ use of social media for educational purposes: A sample from a medical university in Hanoi, Vietnam. Health Services Insights, 14, 11786329211013548. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786329211013549

- Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

- Boyatzis, R. E., & Boyatzis, R. (2008). Competencies in the 21st century. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840730

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Candy, P. C., Crebert, R. G., & O’leary, J. (1994). Developing lifelong learners through undergraduate education (Vol. 28). Australian Government Pub. Service.

- Carter Jr, R. A., Jr., Rice, M., Yang, S., & Jackson, H. A. (2020). Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Information & Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0114

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences.

- Cornford, I. R. (2002). Learning-to-learn strategies as a basis for effective lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370210141020

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

- Do, T.-T., Thi Tinh, P., Tran-Thi, H.-G., Bui, D. M., Pham, T. O., Nguyen-Le, V.-A., Nguyen, T.-T., & Cheng, M. (2021). Research on lifelong learning in Southeast Asia: A bibliometrics review between 1972 and 2019. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1994361. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1994361

- Edwards, R., Ranson, S., & Strain, M. (2002). Reflexivity: Towards a theory of lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21(6), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260137022000016749

- Eisenberg, N., Smith, C. L., & Spinrad, T. L. (2011). Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 263–283). The Guilford Press.

- Endedijk, M. D., Vermunt, J. D., Meijer, P. C., & Brekelmans, M. (2014). Students’ development in self-regulated learning in postgraduate professional education: A longitudinal study. Studies in Higher Education, 39(7), 1116–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777402

- Endres, T., Leber, J., Böttger, C., Rovers, S., & Renkl, A. (2021). Improving lifelong learning by fostering students’ learning strategies at university. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(1), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720952025

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An introduction. Longman Publishing.

- Greene, B. A. (2015). Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: Reflections from over 20 years of research. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.989230

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (Vol. 7). Pearson.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., Ray, S. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hee, O. C., Ping, L. L., Rizal, A. M., Kowang, T. O., & Fei, G. C. (2019). Exploring lifelong learning outcomes among adult learners via goal orientation and information literacy self-efficacy. International Journal of Evaluation & Research in Education (IJERE), 8(4), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v8i4.20304

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hockings, C., Thomas, L., Ottaway, J., & Jones, R. (2018). Independent learning – what we do when you’re not there. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1332031

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2021). Reports of the general discussion working party on skills and lifelong learning. International Labour Conference. http://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/109/reports/provisional-records/WCMS_832306/lang–en/index.htm

- Jackson, D., & Tomlinson, M. (2020). Investigating the relationship between career planning, proactivity and employability perceptions among higher education students in uncertain labour market conditions. Higher Education, 80(3), 435–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00490-5

- Jõgi, L., Karu, K., & Krabi, K. (2015). Rethinking teaching and teaching practice at university in a lifelong learning context. International Review of Education, 61(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-015-9467-z

- Kallio, H., Virta, K., & Kallio, M. (2018). Modelling the components of metacognitive awareness. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 7(2), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.2018.2789

- Kim, C., Park, S. W., Cozart, J., & Lee, H. (2015). From motivation to engagement: The role of effort regulation of virtual high school students in mathematics courses. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(4), 261–272.

- Kirby, J. R., Knapper, C., Lamon, P., & Egnatoff, W. J. (2010). Development of a scale to measure lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601371003700584

- Ku, K. Y. L., & Ho, I. T. (2010). Metacognitive strategies that enhance critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9060-6

- Laal, M., & Salamati, P. (2012). Lifelong learning; why do we need it? Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 31, 399–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.073

- Labaree, D. F. (2014). Let’s measure what no one teaches: PISA, NCLB, and the shrinking aims of education. Teachers College Record, 116(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600905

- Lauder, H. The roles of higher education, further education and lifelong learning in the future economy. (2020). Journal of Education & Work, 33(7–8), 460–467. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1852499

- Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. Guilford Publications.

- Lechner, C. M., Tomasik, M. J., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2016). Preparing for uncertain careers: How youth deal with growing occupational uncertainties before the education-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95-96, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.08.002

- Lei, M., & Medwell, J. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student teachers: How the shift to online collaborative learning affects student teachers’ learning and future teaching in a Chinese context. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09686-w

- Lin, T.-J. (2021). Exploring the differences in Taiwanese University students’ online learning task value, goal orientation, and self-efficacy before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(3), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00553-1

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newberry Park.

- Littman-Ovadia, H., Lazar-Butbul, V., & Benjamin, B. A. (2014). Strengths-based career counseling: overview and initial evaluation. Journal of Career Assessment, 22(3), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072713498483

- Lüftenegger, M., Schober, B., van de Schoot, R., Wagner, P., Finsterwald, M., & Spiel, C. (2012). Lifelong learning as a goal – Do autonomy and self-regulation in school result in well prepared pupils? Learning and Instruction, 22(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.06.001

- Malan, M., & Stegmann, N. (2018). Accounting students’ experiences of peer assessment: A tool to develop lifelong learning. South African Journal of Accounting Research, 32(2–3), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2018.1487503

- Margaliot, A., Gorev, D., & Vaisman, T. (2018). How student teachers describe the online collaborative learning experience and evaluate its contribution to their learning and their future work as teachers. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(2), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2017.1416710

- McMillan, W. J. (2010). ‘Your thrust is to understand’ – how academically successful students learn. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903488105

- Newman, R. S. (2002). How self-regulated learners cope with academic difficulty: The role of adaptive help seeking. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_10

- Nguyen, T. T. H. (2021). Report on the Covid-19 impacts on labour and employment situation in the third quarter of 2021. General Statistics Office of Vietnam. https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2021/10/report-on-the-covid-19-impacts-on-labour-and-employment-situation-in-the-third-quarter-of-2021/

- Nguyen, T. T. H., & Walker, M. (2016). Sustainable assessment for lifelong learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.985632

- OECD. (2008). Learning in the 21st Century: Research, Innovation and Policy. OECD/CERI International Conference https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/oecdceriinternationalconferencelearninginthe21stcenturyresearchinnovationandpolicy15-16may2008.htm

- Pham, T., & Jackson, D. (2020). Employability and determinants of employment outcomes. In Developing and utilizing employability capitals (pp. 237–255). Routledge.

- Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-03559900015-4

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

- Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A Manual for the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED338122

- Piróg, D., Kilar, W., & Rettinger, R. (2021). Self-assessment of competences and their impact on the perceived chances for a successful university-to-work transition: The example of tourism degree students in Poland. Tertiary Education and Management, 27(4), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-021-09081-5

- Popadiuk, N. E., & Arthur, N. M. (2014). Key relationships for international student university-to-work transitions. Journal of Career Development, 41(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313481851

- Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). Springer

- Rieckmann, M. (2012). Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures, 44(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2011.09.005

- Schunk, D. H. (2005). Commentary on self-regulation in school contexts. Learning and Instruction, 15(2), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.04.013

- Staff, J., Harris, A., Sabates, R., & Briddell, L. (2010). Uncertainty in early occupational aspirations: Role exploration or aimlessness? Social Forces, 89(2), 659–683. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0088

- Tomlinson, M. (2008). ‘The degree is not enough’: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701737457

- Tomlinson, M. (2010). Investing in the self: Structure, agency and identity in graduates’ employability. Education, Knowledge & Economy, 4(2), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496896.2010.499273

- Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education + Training, 59(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090

- UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL). (2020). Embracing a culture of lifelong learning: Contribution to the futures of education initiative. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374112

- van Den Hurk, M. (2006). The relation between self-regulated strategies and individual study time, prepared participation and achievement in a problem-based curriculum. Active Learning in Higher Education, 7(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787406064752

- Warrier, U., John, M. & Warrier, S. (2021). Leveraging Emotional Intelligence Competencies for Sustainable Development of Higher Education Institutions in the New Normal. FIIB Business Review, 10(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714521992032

- Weinstein, C. E., & Mayer, R. E. (1986). The teaching of learning strategies handbook of research on teaching. Editor: MC Wittrock. Macmillan Company.

- Wolters, C. A., & Rosenthal, H. (2000). The relation between students’ motivational beliefs and their use of motivational regulation strategies. International Journal of Educational Research, 33(7–8), 801–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00051-3

- Yundayani, A., Abdullah, F., Tantan Tandiana, S., & Sutrisno, B. (2021). Students’ cognitive engagement during emergency remote teaching: Evidence from the Indonesian EFL Milieu. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.52462/jlls.2

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). From cognitive modeling to self-regulation: a social cognitive career path. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.794676

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Pons, M. M. (1986). Development of a structured interview for assessing student use of self-regulated learning strategies. American Educational Research Journal, 23(4), 614–628. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312023004614