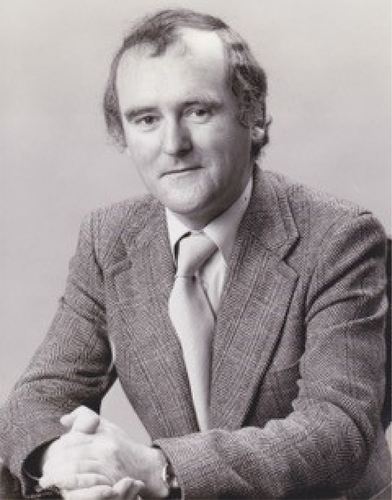

Teddy Thomas, who died aged 89 on 11th July, was a co-founder, with the late Peter Jarvis, of the International Journal of Lifelong Education; together, they edited it for its first seventeen years. A major figure in adult education nationally and internationally, he served as Reader and later Robert Peers Professor of Adult Education at the University of Nottingham, as well as Deputy Head and Head of the Department of Adult Education. He was also a leading figure in the University more broadly, serving both as Dean of the Faculty of Education and senior Pro-Vice-Chancellor. An excellent scholar – he was awarded a higher doctorate (D.Litt.) by the University of Nottingham – he had sixteen books and many articles and chapters to his name. A firm advocate of research in adult and lifelong education, he worked tirelessly for SCUTREA (the Standing Conference on University Teaching and Research in the Education of Adults), chairing it during the early 1980s. He campaigned energetically for university adult education, not only in the East Midlands but nationally, as a member of the Universities Council for Adult Education – what has now become UALL.

Teddy was, as none who knew him could doubt, a Welshman. He came from Pembrokeshire; his early childhood, spent in a Haverfordwest council house, was tough – though, as he told his family, ‘very happy’ and with a strong sense of community. For generations his forebears had been farm labourers and fishermen; as a child, a similar future beckoned for him.

Two events changed his life. First, just a year into the Second World War, with Teddy just 6½, his father – second engineer on a trawler – was killed, along with the entire crew, when their ship ran into a mine off the Irish coast. A fatherless childhood and deep poverty followed.Footnote1 Second, he found himself – born at the end of 1933 – one of the first beneficiaries of the 1944 Education Act. Many criticisms have since been levelled at the ‘tripartite’ system the Act introduced – children were allocated to different types of secondary school, and their lifelong education and career opportunities thus largely determined, based on a rough-and-ready assessment of ability at age 11. But for Teddy it worked. Passing the ‘eleven plus’, the wider intellectual and cultural world offered by grammar school opened: literature, music – the trumpet, which he played in the National Youth Orchestra of Wales – and jazz. And every day a free hot meal.

After school came National Service in the army, followed by a degree in English Literature at St. Peter’s Hall (now St Peter’s College), Oxford (1954–1957). Then, still in his early twenties, he spent three years in the Colonial Service, becoming responsible for a territory – the size of Wales, apparently – in what is now Zambia. (He learnt to speak Bemba.) Perhaps because his role involved administering several prisons, on leaving Africa – the ‘Winds of Change’ were blowing – his next career move, after a term’s school-teaching in Birmingham, was seven years in the English Prison Service. He began, after training, at a Borstal (for young offenders) in Feltham, Middlesex; but he combined five of his prison years with part-time study for a University of London External B.Sc. in Economics (awarded in 1967), and four he spent training ‘prison staff at all levels, and of most ranks, at the Prison Service Staff College’ (Thomas, Citation1972b, p. 199). He then studied for a D.Phil. on the history of prison officers at the (then rather new) University of York, completing his thesis in 1970. It appeared two years later as a book (Thomas, Citation1972a).

By then he had moved, as a lecturer, to Hull University’s adult education department. He was to remain there through the 1970s, though he found time for an extended visit to Australia and New Zealand – less common then than it has become. At Hull his research on prisons continued, with contributions on policy (e.g. Thomas, Citation1975a, Citation1975b, Citation1981), and following a major disturbance in Hull, on prison riots (Thomas, Citation1977; Thomas & Pooley, Citation1980). But he also involved himself more generally with adult education. (To observers today this may seem natural, but half a century ago many university adult education staff had little or no interest in their field of practice, focussing instead on the subjects they taught.) Teddy taught on Hull’s Diploma in the Teaching of Adults, and also began to think and write about the field – though his contributions on adult education as such began to appear largely after he moved from Hull to Nottingham in 1979.

That said, Teddy’s views on adult education, and what it should comprise, were forming even as he focused on vocational training for prison staff. We can see this in a thoughtful early paper on ‘Training Schemes for Prison Staff’: he valued training not merely for its vocational dimension, for the skills it developed – though that he certainly did – but for its own sake. It enabled people. It also encouraged them, and institutions and systems they created, to think about their worlds, to experiment, to challenge, and to begin processes of change. The fact, he wrote, is

that training is a beginning, not an end, that indulgence in it will generate as many problems as are solved, and that it is a process, once begun, which is difficult to arrest and eradicate. This is only to say that it is education. (Thomas, Citation1972b, p. 200)

He developed the argument: training must be ‘a continuous process’; this not only showed that the organisation valued it, but was ‘actually conducive to its success’. Where training is ‘an episode, an incident almost … any threat it may pose to existing orders can be contained. It can be made into an island. But if training is to make any kind of impact, it has to be continuous, with regular meetings, discussions, and follow-up of various kinds’ (Thomas, Citation1972b, p. 201). He advocated engaging with social scientific material ‘relevant to the task of helping staff to understand the complexities of human behaviour more effectively’, such as ‘the sociology of “total institutions”’ – he mentioned ‘pioneer work’ by Goffman (Citation1961) – ‘not often included’, apparently, at the time (Thomas, Citation1972b, pp. 203–204). More generally:

What is needed to offset the tendency to limit the course to vocational training is a liberal component. This is desirable in any vocational course, but for prison staff it should be a central feature. … What kinds of subjects should constitute this liberal element? … I mean, for example, a study of crime … through plays and novels about criminals. History, which is of great interest to most people, especially mature students, could be approached through a study of the history of crime and of the treatment of criminals. Fagin, Macbeth, and some of the Russian heroes can all be used to illustrate aspects of criminal psychology. Teachers trying to communicate the essence of stratification, its form and meaning, could use novels which draw their inspiration from this particular social phenomenon. … Once training is seen as a broadly based educational experience, then whole new possibilities are opened up. … (Thomas, Citation1972b, pp. 204–205)

As this suggests, Teddy joined Hull with well-formed and strong views on the importance of a broad, liberal education – very much in line with what mattered in British university extra-mural education and the Workers’ Educational Association. Yet in the same article we can already see a desire to strengthen what might now be called the ‘research base’. It was ‘often claimed’, he wrote, that ‘mature students of limited educational experience’ were able to ‘see parallels between apparently different situations, … to apply theoretical concepts to practical experience, … to generalise from the particular and, … particularise from the general’. His observation was almost acid: ‘There is no real evidence of this, except as an expression of faith by adult educators’ (Thomas, Citation1972b, p. 204). Faith, even adult educators’ faith, was not enough.

Teddy’s attitude to research made his appointment as Reader and Deputy Head in the Nottingham Adult Education Department particularly welcome. Michael Stephens, the youthful Robert Peers Professor and Head of Department,Footnote2 was a strong advocate of research, a pioneer in the teaching of adult education as an academic discipline, and a founder (in 1969) and continuing champion of SCUTREA, contributing ‘significantly’ – as Teddy wrote – ‘to the elevation of Adult Education from conferential polemics to serious academic study’ (Thomas, Citation1994, p. 422). Teddy had himself been an enthusiastic member of SCUTREA from its early days (cf Toye et al., Citation1972), and together – through the 1980s – Teddy and Michael contributed much to developing adult education as a strong field of university study and research. In particular, the University of Nottingham’s Department of Adult Education became a leading publisher in the field. Teddy was key to this, as one of a triumvirate of editors (with Michael Stephens and Kenneth Lawson) of the book series, ‘Nottingham Studies in the Theory and Practice of the Education of Adults’. This published out-of-print classics of the field (e.g. Harrop, Citation1987; Ministry of Reconstruction Adult Education Committee, Citation1980), with new, scholarly introductory essays, as well as new editions of important recent books (e.g. Lovett, Citation1982). But equally significant was the original research work: some, such as Teddy’s own Radical Adult Education (Thomas, Citation1982), by members of the Nottingham department, but much by authors from elsewhere (e.g. Hall, Citation1985; Styler, Citation1984). Other series followed (‘Nottingham Studies in the History of Adult Education’, ‘Nottingham Working Papers in the Education of Adults’), as well as self-standing works.

The mutually supportive relationship between Teddy and Michael Stephens also contributed to the formation of the International Journal of Lifelong Education, and to Teddy’s role as its co-founder and joint editor. As Teddy recounted only last year, Michael was ‘fanatical’ about developing theories of adult education – he ‘had a national reputation’ for it. ‘So when Peter [Jarvis] was looking around for allies [to start the journal], Michael was clearly one of his first ports of call. Michael was extremely busy at the time. And he asked me if I’d take an interest in it, which … I was very glad to do’ (Thomas, Citation2022). Thus began seventeen years of journal editing. Peter and Teddy built one of the leading scholarly publications in the field; they secured high-quality contributions in good numbers, strong sales, and by the early 1990s were able to persuade the publishers to move from four to six issues a year. Teddy also persuaded his Nottingham colleague John Davies to take on the role of review editor – a considerable boost for the journal (Holford et al., Citation2023, p. 540); no doubt this contributed to their joint work on adult education bibliography (Davies & Thomas, Citation1988; Thomas & Davies, Citation1984).

In parallel with his editorial work for the Nottingham series, and for the International Journal of Lifelong Education, Teddy was a leading figure in SCUTREA, which he chaired during a difficult period (1981–1984) of ‘cuts’ to university, and adult education, budgets. (A taste of worse to come.) A fascinating address from the chair to the 1984 conference reflected on what SCUTREA had achieved, and what it had not. It still repays reading. Research, he was clear, ‘means something more than arithmetical surveys, what C. Wright Mills called “relentless empiricism”’:

… in part as a result of the stimulus afforded by SCUTREA, university adult educators have written books which, while not the outcome of ‘research’ in the sense in which the statisticians would understand it, are nevertheless important because they intellectualise about adult education and give the subject depth.

As one among ‘many examples’, he mentioned Adult Education for a Change (Thompson, Citation1980) – still a classic. SCUTREA, Teddy concluded, ‘contributed, directly and indirectly, to the development of research and theory … notably, by concentrating on teaching and research and by providing platforms for people who wish to discuss these at a critical and analytical level’. But he remained practical: the ‘urgent need’ was ‘to identify ways of improving the theory of our work and by so doing to improve its practice’.

Teddy also played a key role in the early development of the utopian and short lived International League for Social Commitment in Adult Education (ILSCAE). Intrigued by the aspirations outlined at its founding event in 1984 (among them ‘To encourage all those involved in adult education to foster participation in dialogue on the critical social issues confronting humankind today, such as class inequality, environmental concerns, peace, racism, sexism and ageism’, and ‘to encourage all those involved in adult education to identify and act to overcome the social, political and economic forces which perpetuate the existence of poverty, oppression and political powerlessness’), Teddy attended the second event in Sweden along with radical and liberal scholars and activists from North America, Europe and South Africa, as well as Chilean refugee and PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation) educators. Teddy co-planned and hosted ILSCAE’s third event at Nottingham (ILSCAE, Citation1987), reinforcing critical debate between academics and practitioners, and participated in a memorable workshop and conference hosted by Sandinista literacy workers in Nicaragua. He formed a powerful friendship with Palestinian educators active in ILSCAE.

Teddy was always an advocate of developing ‘theory’ in adult education, but he was not by disposition a ‘theorist’. His research interests, though reflective and (as his allusions to Goffman and Wright Mills mentioned above testify) informed by theory, were strongly historical. In the early 1980s he embarked on an International Biography of Adult Education (Thomas & Elsey, Citation1985); later in the decade he published another book on the history of prisons and their inmates (Thomas, Citation1988). He developed an interest in Japan: initially he focussed on education for democracy (Thomas, Citation1985), but the interest in its society and culture broadened and flourished in later works (Thomas, Citation1993, Citation1996); he was elected a Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

During the later 1980s and 1990s, Teddy was drawn more and more into university administration. When Michael Stephens retired in 1989, Teddy became Robert Peers Professor of Adult Education and Head of the Department of Adult Education. He served as Dean of the Faculty of Education, and from 1990 to 1994 – the appointment was for a fixed term – as Pro-Vice Chancellor, responsible in particular for ‘making sure things worked for the students’ and ‘access, which was then very fashionable’ (Thomas, Citation2022). When he stepped down – by then he was senior Pro-Vice Chancellor and effectively second-in-command of the entire university – he preferred not to return to departmental management, and soon opted instead to retire slightly early. He was appointed professor emeritus.

Teddy retired from the editorship of the International Journal of Lifelong Education at the end of 1998. He remained remarkably active: an allotment, choir, brass bands, his family – he and Olwen Yolland married in 1957, and have been parted only by his death; their two sons Simon and Philip were born in 1958 and 1961. But he also remained a researcher and scholar: no longer driven by the requirements of institutional research strategies and funding priorities, his publications no doubt say much of his more personal interests; they speak to his historical bent. A book on the last invasion of the British mainland – the French landed on 22 February 1797 at Fishguard, just fifteen miles from Teddy’s childhood home (Thomas, Citation2007) – took him back to Pembrokeshire. His focus remained on Wales with a book on the power of the gentry, radicalism and religion in Wales in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Thomas, Citation2011). A biography of Sabine Baring-Gould – Victorian antiquarian, novelist, scholar, and hymn-writer – followed (Thomas, Citation2015).

Teddy had a capacity to mix congenially with men and women from all backgrounds; but he was ever a radical, a man of the Left. His most recent books show how this continued to the end: Voices from Captivity: Incarceration from Siberia to Guantánamo Bay is ‘about the experience of being locked up’, including testimony from those who ‘are guilty of heinous crimes and those who have committed no offence at all’. ‘I make no judgement’, Teddy wrote in the introduction, ‘on the reasons why people find themselves in captivity, or on the accuracy of what they say. The fact is that this is what they experienced, and no one is in any position to say they are mistaken’ (Thomas, Citation2018, p. 13). Giving voice to the dispossessed, supporting them in developing their own articulacy, is a continuing concern of the adult educator, and Teddy displayed it to the last. According to the publisher’s ‘blurb’, his final book, The Grandest Larceny: The Foundation of Israel (Thomas, Citation2023) argues that ‘when the British “gave” Palestine to the Jews by the Balfour Declaration’ it represented ‘the handing over of a country by a country who did not own it, to a third which had only mythical claims to it’, and as a result ‘the region has been plagued by wars, deaths and a refugee problem of millions’.Footnote3

Teddy’s later life may have taken him into other areas of scholarship, but we should conclude by noting that his commitment to adult education never wavered. In several events in recent years he excoriated the destruction of adult education in Britain – not least in events at Nottingham, the University he had served so loyally and effectively for so long, but which, just after the millennium, joined a national insanity, razing the achievements of eighty years with gay abandon. In the final year of his life he attended various events associated with the exhibition Knowledge is Power: Class, Community and Adult Education.Footnote4

It was Teddy’s misfortune – though not his alone – to have moved to a leading position in adult education at Nottingham in 1979, just as what he later called ‘the Thatcher pestilence’ descended on Britain (Thomas, Citation2017). He engaged in a vigorous campaign to ‘Save Adult Education’; it had some successes, though in retrospect we know there were decades of defensive, and generally vain, campaigning to come. In a paper, ‘Adult Education and Political Process’, published shortly after he came to Nottingham, he analysed the ‘sustained attack upon adult education provision’ of the previous two years. He rightly saw it ‘part of the philosophy of monetarism’, which sought ‘a reversion to Puritan social and financial accounting’ and was ‘a philosophy … gaining ground as a solution to economic malaise’.

Given sufficient ignorance or ill will on the part of policy makers, any economic or political policy could justify destruction of adult education. Adult educators are now called upon to ask why provision is a target for cuts, how the machinery to effect these cuts is mobilised, and how they can resist the relentless move towards the extinction of a singularly Anglo-Saxon component of civilised society. (Thomas, Citation1980, p. 1)

The analysis that followed was in many ways prescient. This is not the place to rehearse it, though it repays reading. (Its main weakness, viewed from today, probably lies the then very reasonable assumption that such economic policies would be ‘transient’.) He understood that the government was ‘trying to alter fundamental structures and assumptions’; adult education was ‘in danger of becoming one of the most significant casualties in the process, with incidentally, only modest “saving”’ (Thomas, Citation1980, p. 8). But it contains an insight, which I heard him repeat, in more or less the same words, forty years later:

An educated electorate, conscious of the diminution of political difference between the various parties seeking to hold power, and aware of the more important phenomenon – a gap between rulers and ruled – would be a threat indeed. So modern rulers have no desire to encourage adult education which might create political sophistication. (Thomas, Citation1980, p. 3)

He was right.

Acknowledgements

In drafting this obituary, the author has drawn on his own personal knowledge, as well as recollections from Ian Sutton, Sir Alan Tuckett and Stirling Smith. He is particularly grateful to Olwen, Philip and Simon Thomas for information and for their comments on a draft of the article.

Notes

1. It may not be significant, but is nonetheless noteworthy, that Peter Jarvis also lost his father when very young (he was eight), and grew up in a consequently impoverished working-class family; cf Holford (Citation2017, p. 5).

2. Teddy’s obituary of Michael Stephens (1936–1994) can be found in this journal (Thomas, Citation1994).

3. See https://www.fonthill.media/products/larceny (accessed 9th August 2023). The Grandest Larceny was published on 17th August 2023, shortly after Teddy died.

4. The exhibition, held at the University of Nottingham’s Weston gallery in late 2022 and early 2023, marked the centenary of Robert Peers' appointment to the world’s first university chair in adult education. It ‘showcased how adult education enriches the lives and culture of ordinary – and extraordinary – people, and helps build a fairer and more democratic society’. Various exhibits, along with recordings of several talks, are available online at: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/exhibitions/online/knowledgeispower/knowledgeispower.aspx.

References

- Davies, J., & Thomas, J. E. (1988). A select bibliography of adult continuing education. National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the condition of the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Anchor Books.

- Hall, W. A. (1985). The adult school movement in the twentieth century. University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Harrop, S. A. (1987). Oxford and working-class education: Being the report of a joint committee of the University and working-class representatives on the relation of the University to the higher education of workpeople (New ed.). University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Holford, J. (2017). Local and global in the formation of a learning theorist: Peter Jarvis and adult education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 36(1–2), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2017.1299994

- Holford, J., Hodge, S., Knight, E., Milana, M., Waller, R., & Webb, S. (2023). Lifelong education research over 40 years: Insights from the International Journal of Lifelong Education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 41(6), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2022.2167445

- ILSCAE. (1987). About a week in Nottingham: Themes from the 1986 conference of the International League for Social Commitment in Adult Education. Clapham-Battersea Adult Education Institute.

- Lovett, T. (1982). Adult education, community development and the working class (2nd ed.). Dept. of Adult Education, University of Nottingham.

- Ministry of Reconstruction Adult Education Committee. (1980). The 1919 report: The Final and Interim reports of the Adult Education Committee of the Ministry of Reconstruction, 1918-1919. University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Styler, W. E. (1984). Adult education and political systems. Department of Adult Education, University of Nottingham.

- Thomas, J. E. (1972a). The English prison officer since 1850: A study in conflict. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Thomas, J. E. (1972b). Training schemes for prison staff: An analysis of some problems. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 5(4), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/000486587200500402

- Thomas, J. E. (1975a). Policy and administration in penal establishments. In L. Blom-Cooper (Ed.), Progress in Penal Reform. Clarendon Press.

- Thomas, J. E. (1975b). Special units in prison. In K. Jones (Ed.), The year book of social policy in Britain 1974, (pp. 89–100). Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Thomas, J. E. (1977). Hull ’76: Observations on the inquiries into the prison riot. Howard Journal of Penology and Crime Prevention, 123, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.1978.tb00340.x

- Thomas, J. E. (1980). Adult education and political process. Studies in Continuing Education, 3(5), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037800030501

- Thomas, J. E. (1981). From caprice to anarchy: The role of the English prison governor. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 25(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X8102500303

- Thomas, J. E. (1982). Radical adult education: Theory and practice. University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Thomas, J. E. (1985). Learning democracy in Japan: The social education of Japanese adults. SAGE Publications.

- Thomas, J. E. (1988). House of care: Prisons and prisoners in England 1500-1800. University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Thomas, J. E. (1993). Making Japan work: Origins, education and training of the Japanese salaryman. Japan Library.

- Thomas, J. E. (1994). Obituary: Professor Michael Dawson Stephens. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13(6), 421–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260137940130602

- Thomas, J. E. (1996). Modern Japan: A social history since 1868. Addison Wesley Longman.

- Thomas, J. E. (2007). Britain’s last invasion: Fishguard 1797. Tempus.

- Thomas, J. E. (2011). Social disorder in Britain 1750-1850: The power of the gentry, radicalism and religion in Wales. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755622788

- Thomas, J. E. (2015). Sabine Baring-Gould: The life and work of a complete Victorian. Fonthill Media.

- Thomas, J. E. (2017). Dr. Kenneth Lawson. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 36(4), 387. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2017.1355649

- Thomas, J. E. (2018). Voices from captivity: Incarceration from Siberia to Guantánamo Bay. Jessica Kingsley.

- Thomas, J. E. (2022, July 6). Unpublished interview/Interviewer: J. Holford. University of Nottingham.

- Thomas, J. E. (2023). The grandest larceny: The foundation of Israel. Fonthill Media.

- Thomas, J. E., & Davies, J. H. (1984). A select bibliography of adult and continuing education in Great Britain. National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

- Thomas, J. E., & Elsey, B. (1985). International biography of adult education. University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education.

- Thomas, J. E., & Pooley, R. (1980). Exploding prison: Prison riots and the case of Hull. Junction Books.

- Thompson, J. (Ed.). (1980). Adult Education for a change. Hutchinson.

- Toye, M., Connor, W., Pask, G., Thomas, J. E., & Nichol, J. B. (1972). Report of the special interest group on managerial training for adult education. Paper presented at the Standing Conference on University Teaching and Research in the Education of Adults.