?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Some people in Japanese society have been classified as ‘invisible’ because they could not complete their compulsory elementary school education and have failed to assimilate into mainstream society. The 2010 Japan Census identified about 1.3 people per thousand over 15 years old who had not graduated from elementary school. However, the circumstances that prevented them from completing their compulsory elementary school education and their current challenges in accessing lifelong learning have yet to be researched. In an attempt to investigate these two issues, quasi-experimental panel data analysis with count data was applied to determine the characteristics of invisible people using the Japan census data disaggregated by the district for all residents and decomposed of environmental and war factors, thus unravelling the geographic anomaly in the national data. Estimation results showed that their features can be explained by three multi-level layers: 1) an explanation due to personal conditions: being in a state of poverty, 2) an explanation created by differences in nationality, and 3) identification from environmental factors, such as geographical isolation and the Battle of Okinawa. We can identify specific features of how to deliver lifelong learning to people with information barriers.

Introduction

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) calls for ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. Nevertheless, the education gap in developed countries has become a growing problem. Even if a country’s literacy rates are high as a whole, there is a group of people who do not complete their compulsory education. These people have been labelled as invisible people in Japan, often on the fringes of the main society.

According to a literacy survey by the Japanese government in 1948 and 1955, the literacy rate in Japan is almost 100 percent (UNESCO, Citation1964, p. 92). In addition, out of the 38 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, Japan ranks number one on the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) survey of adult education (OECD, Citation2023, p. 29). Nonetheless, there is a certain percentage of the Japanese population that has not completed their compulsory education (i.e. invisible people), and they are not represented by these statistics.

While some studies have confirmed the existence of invisible people in Japan, no studies have investigated their demographics, characteristics, or circumstances. This paper presents some background information on these invisible people and identifies some of their characteristics.

Literature review

This section looks at the characteristics and results of the PIAAC survey, the groups that were left out of the survey, and the characteristics of these groups.

The PIAAC survey in Japan

The PIAAC survey of adult education is ‘an international study for measuring, analysing, and comparing adults’ basic skills’ (National Center for Education Statistics, Citationn.d.) in three skill areas: literacy, numeracy, and digital problem solving. It was developed by the OECD and intended to be administered once a decade in participating member countries. The PIAAC focuses on assessing ‘the basic cognitive and workplace skills needed for individuals to participate in society and for economies to prosper’ (National Center for Education Statistics, Citationn.d.). in order ‘to help countries better understand their education and training systems and the distribution of these basic skills across the adult working-age population’ (National Center for Education Statistics, Citationn.d.).

Results from the PIAAC are reported as average scores on a 500-point scale and on continuums of proficiency levels. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (Citationn.d.), ‘proficiency refers to the “mastery” of a set of abilities along a continuum that ranges from simple to complex information-processing tasks’. The continuums for literacy and numeracy have been divided into six levels of proficiency, with each level defined by a certain range of scores. Level Five is 376–500 points, Level Four 326–375 points, Level Three 276–325 points, Level Two 226–275 points, Level One 176–225 points, and Below Level One 0–175 points. The continuum for digital problem solving has been divided into four proficiency levels with corresponding point ranges: Level Three 341–500 points, Level Two 291–340 points, Level One 241–290 points, and Below Level One 0–240 points.

This survey was administered by the Japanese Government in December 2011. Eleven thousand males and females between the ages of 16 and 65 were randomly selected from the Basic Resident Registry using a stratified two-stage sampling method (NIER National Institute for Educational Policy Research, Citation2013, p. 2). The registry is a compilation of resident records containing the name, date of birth, gender, address, etc., and serves as the basis for administrative processes relating to residents in Japan. Stratified two-stage random sampling is a method often used when conducting national sample surveys of the general public. According to NIER (National Institute for Educational Policy Research), Citation2013, p. 5), sampling was carried out as follows: municipalities nationwide are divided (stratified) into 30 groups (strata) based on a combination of regional proxies and city size. In the first stage, districts which make up the municipality are selected from each stratum as survey points, and in the second stage, individuals for the survey are selected from among the residents of towns and villages of those areas. A total of 5,173 people responded.

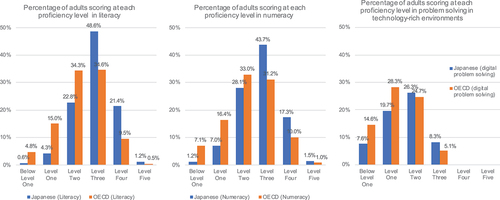

Based on the responses received, the overall level of adult education in Japan across all adult working-age groups is relatively high compared to all other participating OECD countries. Scores in literacy and numeracy rank number one, and scores for problem solving in technology-rich environments are ranked comparatively high (NIER National Institute for Educational Policy Research, Citation2013, p. 21). According to the OECD (Citation2023), ‘adults in Japan display the highest levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy among adults in all countries participating in the survey’. The distribution of score levels in Japan and a comparison with OECD countries is shown in . In literacy, the mean score for Japanese respondents is 296.2, which is the highest of all participating OECD countries (OECD, Citation2019). The mean score for all participating OECD countries is 266.2. In numeracy, the mean score for Japanese respondents is 288.2. The mean score for all participating OECD countries is 261.9. In digital problem solving, ‘the percentage of adults scoring at Level 3 in problem solving in technology-rich environments is high compared to other [participating OECD] countries’ (OECD, Citation2023).

Figure 1. The distribution of score levels in Japan and a comparison with OECD countries.

Although Japan as a whole scored high in literacy, numeracy, and digital problem solving compared to other OECD participating countries, it should be noted that some groups were purposefully left out of the survey target population. Foreign residents were excluded from taking this survey (NIER National Institute for Educational Policy Research, Citation2013, p. 2). At the time of the survey in 2011, the percentage of registered foreigners in the total population was 1.63%, and they were excluded from the survey because some foreigners living in Japan have difficulties in speaking Japanese as an official language. Also, according to the PIAAC Technical Standards and Guidelines, the target population also excludes adults in institutional collective dwelling units such as prisons, hospitals, and nursing homes (OECD, Citation2023, p. 35, Guideline 4.1.1A). Another group of people who were omitted from the survey data are the ‘invisible’ people, Japanese people not officially registered in the Basic Resident Registry.

The PIAAC survey data indicate that among OECD member countries, Japan’s scores in adult education are very high. However, it should be noted that several groups were excluded from the survey. Foreigner residents were excluded from the survey because of their lack of competency in the Japanese language. Japanese people who are not registered in the Basic Resident Registry, as well as those in prisons, hospitals, and nursing homes, were also excluded from the survey. It is questionable how representative the PIAAC results are of actual Japanese society; rather, they are merely a reflection of those who responded to the survey.

Who are the invisible people?

Invisible people are those living in Japan who did not complete their compulsory education of six years of primary education and three years of secondary education. According to the qualitative studies conducted so far (Sukore, Citation2015; Hosaka, Citation2019; & Kojima; Kojima, Citation2011), the following categories of invisible people have been identified:

those who were unable to complete their schooling due to war or poverty (Sukore, Citation2015),

those who did not attend school in their childhood (Hosaka, Citation2019)

foreigners living in Japan: immigrants, refugees, or foreign residents (Kojima, Citation2011).

An example of someone who was unable to complete her primary education because of war and poverty is a female student who attended evening classes at a junior high school in Okinawa. In sharing some of her memories from World War II, she mentioned that during the Battle of Okinawa, she often had to flee deep into the jungle to avoid air raids, disrupting her studies at elementary school. Also, during the war, her father died of illness, and the family lost their main provider, so she had to do all the household chores during her school years to help make ends meet. Consequently, she could not complete her primary education (Sukore, Citation2015, pp. 18–20).

According to the National Air Raid Victims Liaison Council (Citationn.d.), the Battle of Okinawa refers to an engagement in World War II involving landings on the main island of Okinawa and some of its remote islands, with organised fighting reported to have started on 2 April 1945 and ended on 23 June of the same year. As no government survey has been carried out on the number of civilians killed during that battle, exact figures are unknown, but the Okinawa Prefectural Welfare and Relief Division estimates the number to be around 94 thousand (National Air Raid Victims Liaison Council, Citationn.d.). If deaths from fighting in the war, malaria, starvation, massacres of local residents, ships in wartime distress, and mass suicide are included in this figure, the number of civilian casualties is estimated to be around 150 thousand, with one in four Okinawans having died in the war.

The second category of invisible people includes children who were unable to attend elementary and junior high schools for various reasons. One reason someone would be deferred or exempted from school is because of severe illness or disability. Another reason one would not attend school is if that child was also a parent and had their own children to take care of. A third reason someone would not attend school is imprisonment or incarceration. Finally, in Japan, there is a family register system called koseki,Footnote1 in which the births, marriages, and deaths of Japanese citizens are recorded. If a child is not recorded in a family register, s/he does not officially exist and cannot attend school.

The third category of invisible people consists of foreigners living in Japan: immigrants, refugees, and legal and illegal foreign residents. Among these groups there are those who, during their youth, did not attend elementary school or dropped out mid-way. This occurred because until 1994 neither local authorities nor the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports, and Technology (MEXT) were legally obliged to ensure that children of foreign residents received compulsory primary and secondary education. However, in 1989, the Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted by the United Nations and entered into force as an international treaty in 1990. In 1994, Japan ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child and entered it into force that year. Article 28 of the Japanese Constitution declares that the state’s parties recognise the right of all children to compulsory education, and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports (Citation2019) declared the following:

Foreign children are enrolled in compulsory education in Japan. Although there is no obligation, if they want to attend public compulsory education schools, they can attend them free of charge, just like Japanese children, in consideration of the International Covenants on Human Rights.

How have these invisible people been identified?

A 2015 MEXT survey conducted at 31 schools in 25 cities and wards in eight prefectures, found that out of the total number of people who were studying in evening classes at public junior high schools, 1,849 had not completed their compulsory education (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Citation2016). In addition, a survey of 198 literacy classes was conducted in buraku all over Japan, and it found that many had not completed compulsory education (Tanada, Citation2011). Buraku is a general term that refers to the communities that have historically been considered outcasts in Japan. These outcast populations include descendants from people who had occupations during the feudal era (1185 AD − 1603 AD) which were considered unclean, such as butchering animals, tanning leather hides, executing condemned criminals, or preparing the dead for burial. Buraku discrimination is a serious human rights issue that is unique to Japan and manifests itself in various forms as discrimination stemming from the status system that has been shaped in the historical development of Japanese society and from the attitudes of people who have been historically and socially shaped in the process (Tokyo Metropolitan Government Human rights Devision. Citationn.d.).

The 2010 Population Census of Japan identified over 128,187 people aged 15 and above (about 1.3 people per thousand) who had not graduated from elementary school. This includes 49 thousand males (0.09% of the total male population) and 79 thousand females (0.14% of the total female population), with females outnumbering males by 1.61 times. According to Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports (Citation2016), out of these 128,187 people, only 1,849 of them (1.4%) were studying in evening classes at a public junior high school.

Although some invisible people have enrolled in lifelong learning programmes, such as literacy classes in buraku or in evening classes at public junior high schools, they account for only a small proportion of the total population of lifelong learners in these programmes and of the total population of invisible people. Surveys of students enrolled in lifelong learning programmes can help to identify invisible people; however, since only a small percentage of the total invisible people population is enrolled in these programmes, these surveys are inadequate to discern the general characteristics of the invisible people population.

Using data from Japan’s 2000 and 2010 national population census, a larger proportion of the invisible people population can be identified. The Population Census of Japan is conducted every five years, and it includes items related to people’s biographical information, such as gender, date and time of birth, nationality, length of residence in their current residence, and employment status, as well as items related to information on households, such as type of household, number of household members, and type of dwelling. However, every 10 years the census also includes items to elicit information on educational background and other data. Therefore, the 2000 and 2010 population census data can provide information on those who did not complete their compulsory primary education.

Not only is the national census a survey of the entire Japanese population, but it also includes foreign residents. Foreigners living in Japan for more than three months, excluding illegal aliens and tourists, are subject to the national census. Thus, the 2000 and 2010 population census data can provide information on foreign residents who did not complete their elementary school education and are a part of the invisible people population.

Research questions

This study attempts to confirm the existence of invisible people and to identify some of their characteristics using data from the 2000 and 2010 Population Census of Japan. Invisible people are those living in Japan who did not complete their compulsory education. The existence and specific characteristics of the invisible people have not been identified in previous literacy surveys or in the PIAAC surveys National Institute for Educational Policy Research (NIER, Citation2013).

With information from the 2000 and 2010 Population Census of Japan, the existence of invisible people can be confirmed because it includes a self-reporting question asking for the respondent’s highest level of education. However, while data for those who did not complete elementary school are elicited by the census, data for those who did not complete junior high school are not. MEXT has recognised this problem and has requested the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication (MIC) to include such survey items in the Population Census. Such items were included in the latest 2020 survey. In future studies, this will allow for an almost complete analysis of the statistics for people who did not complete compulsory education, both primary and secondary, as those figures have yet to be published in any study at this time. This study, however, based on the data currently available from the 2000 and 2010 censuses, focuses on invisible people who did not complete their compulsory elementary education.

As no study has ever analysed the data from the Population Census of Japan for those who did not finish their primary education, this study is the first to do so. It focuses on three questions regarding the characteristics of invisible people in Japan:

Are those who did not complete their primary education now in a state of poverty?

Are foreigners among the invisible people in Japan who did not complete their primary education?

Did the Battle of Okinawa during WWII have an impact on the number of people who did not complete their primary education?

Method

Data

This study uses data from the 2000 and 2010 Population Census of Japan which includes a question eliciting the highest level of education completed by the person being surveyed. One of the answer choices regarding one’s highest level of education completed is that he/she has not finished elementary school.

The use of the 2000 and 2010 population census data has three advantages. First, these two versions of the census are comprehensive surveys examining residents’ lives in detail. They survey all residents in Japan, not only Japanese nationals but also all foreign residents living in Japan. These surveys are available in a variety of languages, and a part of their results reflects the type of education all people residing in Japan have had. Second, these versions of the census elicit precise information about the location of one’s residence. In 2020, there were approximately 1,600 cities, towns, and villages in Japan. However, there are more than 100,000 subdistricts identified in the 2000 and 2010 versions of the census. Third, these surveys employ a visit-and-remain survey method rather than an interview method. The visit-and-remain survey is one of the methods of door-to-door surveys in which the surveyor visits the survey target’s home, explains the purpose and content of the survey, gives a survey form to the subject, and revisits at a later date to collect the answers. Subjects can take their time to respond the survey. Therefore, the problem of interviewer bias may be avoided because there is no interviewer to influence the respondent’s response. Furthermore, the data can be treated as large panel data. Panel data pool observations on a cross-section such as households, countries, firms, and other entities over several periods (Baltagi, Citation2005, p. 1). This study has constructed panel data for over 100,000 sub-regions continuously followed in the 2000 and 2010 censuses.

Procedures

Using the 2000 and 2010 Population Census of Japan data, the geographical distribution and density of those who did not complete their primary education were calculated. The density is determined by dividing the number of invisible people by the population aged 15 and over and showing it as a percentage Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC, Citation2000, Citation2010). A geographic information system (GIS) was used to create maps showing the geographic distribution and density of these groups. GIS data is map data that integrates location data with associated information, such as the density of people who did not complete elementary school.Footnote2

Using the resulting panel data set, regression analysis was conducted to determine whether the characteristics mentioned in the above three questions are associated with people who responded that they did not complete elementary school. Each research question addresses a different factor because the circumstances of people who did not complete elementary school involves multiple factors. Given that the reasons for non-completion of elementary school are diverse and complex, it is necessary to identify different factors. This study’s research questions were formulated to: (1) explain whether the current population is in a state of poverty based on data from the census questionnaires; (2) examine whether being a foreigner is associated with non-completion of elementary school. After controlling for (1) and (2) simultaneously, research question three was considered to examine the existence of barriers that may have prevented individuals from completing their primary education. Specifically, whether geographical factors, such as the remoteness of the island on which one lived and the area which served as a battlefield in WWII, are significant. As Japan is an island country with numerous landmasses separated by the sea, it is reasonable to think that the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education varies greatly depending on geographical isolation or whether or not a location was a war zone. Usui (Citation2020) investigated the number of people who did not complete elementary school on 322 remote islands in Japan and found statistically significant differences among 74 islands.

To address these three research questions simultaneously, we used a random-effects negative binomial regression model, which is a form of regression analysis. This type of panel data analysis is a method for controlling for omitted variable bias. A negative binomial regression model is used for analyses that take non-negative integer values. We applied count data analysis and panel data analysis simultaneously. First, a detailed description of a random-effects (model) was generated. This analysis allows to control for time-invariant unobservable effects, for example, the buraku discrimination factor, which has a positive impact on the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education as a result of living in a particular sub-region; however, it is not possible to introduce a dummy variable to indicate whether the sub-region is buraku or not. Panel data analysis can overcome the problem of omitted variable bias. First, it is difficult to collect all location data of burakus. Even if they could be collected, there are ethical problems in making them explicit. The lack of this variable would lead to exclusionary variable bias. A way to solve this is to use panel data analysis. This analysis does not identify buraku discrimination factors but controls for them as an omitted variable. Therefore, random effects estimation was used to control for the effects of buraku discrimination factors. For an explanation of the selection method for random effects estimation in econometric analysis.Footnote3

Second, a detailed description of a negative binomial regression which is a type of count data analysis, was generated. Count data is generally defined as an event count and refers to the number of times an event occurs, for example, the number of airline accidents or earthquakes. It is the realisation of a nonnegative integer-valued random variable (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation1998, p.1). Since the dependent variable is the number of people who did not complete elementary school, which are very rare events and are scattered across regions of the country, this could be considered to be in the nature of count data. In this case, the use of negative binomial regression was applied. For more details.Footnote4

Results

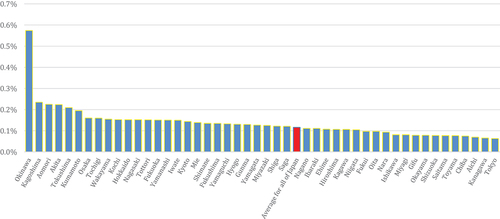

In the 2010 census, the data show that 128,187 people 15 years of age or older (about 1.3 people per thousand) across all prefectures responded that they had not finished their primary education (MIC, Citation2010). shows the ratio of people aged 15 years or older who did not complete elementary school by prefecture and the national average. This figure provides insights into the distribution of these people in Japan, with the percentage for Okinawa Prefecture being predominantly higher than any other prefecture.

Figure 2. The ratio of people over 15 years old who did not graduate elementary school per capita by prefecture level.

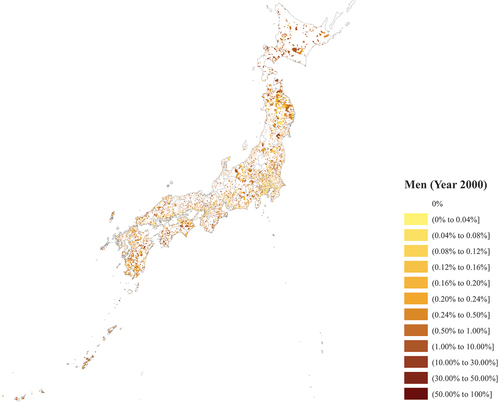

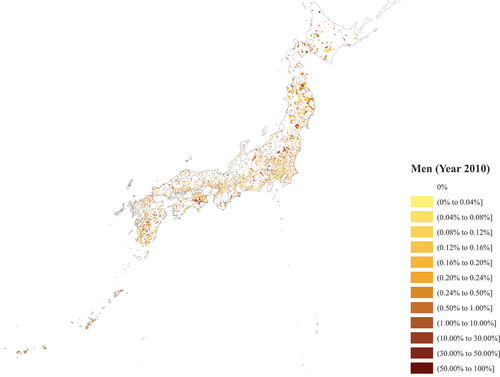

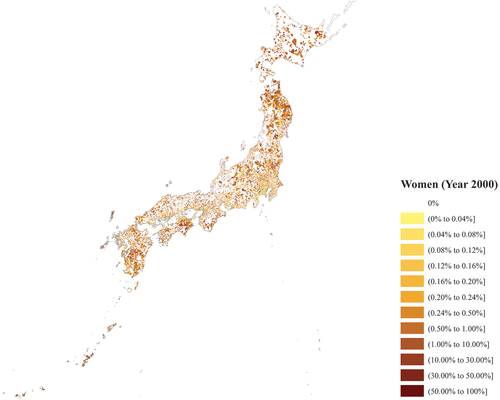

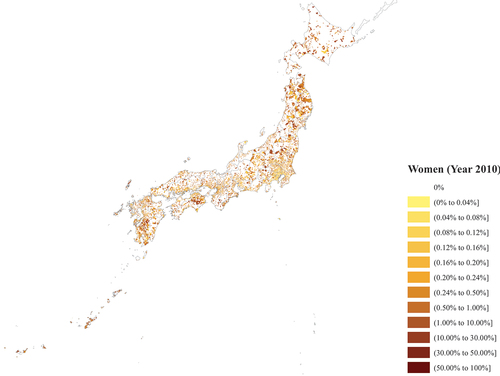

show the geographical distribution of those who did not complete elementary school. Most districts are white because the number of people who did not complete elementary school was zero percent in those areas. The darker the colour, the higher is the density of people who did not complete their primary education. Overall, the number of high-density areas in the 2010 population census decreased from that in the 2000 census. On the other hand, high-density areas still exist in the inland areas of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu Islands, as well as southwest in the island areas of Okinawa Prefecture.

Figure 3. The ratio of people over 15 years old who did not graduate elementary school per capita by prefecture level.

Figure 4. Geographical distribution of the ratio of men over 15 years old who did not graduate elementary school per capita (Year 2010).

Figure 5. Geographical distribution of the ratio of women over 15 years old who did not graduate elementary school per capita (Year 2000).

Figure 6. Geographical distribution of the ratio of women over 15 years old who did not graduate elementary school per capita (Year 2010).

The maps show that some areas continue to have a high density not only because people continue to live in those areas but also because there is a factor that is not reflected in the density data: time-invariant unobserved regional variations. This factor creates a bias for omitted variables when conducting regression analysis. In this study, this factor is a land-specific factor, the existence of buraku discrimination, which has an expected effect of increasing the number of people who have not completed elementary school in the area. In a study of 198 literacy classes held for buraku residents all over Japan, Tanada (Citation2011) notes that about 10 percent of the learners were young people between the ages of 16 and 30. Iwatsuki (Citation2019) also mentions that the efforts to increase adult literacy among the buraku residents began because nearly a quarter of the buraku population had never been to school and needed literacy education. Because of buraku discrimination, this study did not try to identify the location of buraku communities geographically as doing so would have encouraged further discrimination against them. Instead, the bias due to time-invariant unobserved regional characteristics was resolved by applying a panel data analysis.

Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable in our data set was the number of men or women over 15 years of age who did not complete elementary education and who lived in designated districts. The independent variables are descriptive statistics by gender and age (see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for male/female sample.

Some biases needed to be removed in testing the hypotheses. First, biases can be removed by control variables, such as the age structure of people living in the district, the proportion of occupations, the number of households, and the history of residence. These are typical census items. However, the control variables mentioned above cannot remove a few effects, such as the time trend. Additionally, the disparity brought about by geographical factors was controlled by assuming a random effect because the variables cannot be introduced. By making such bias corrections, the hypotheses were tested.

Additionally, the disparity brought about by geographical factors was controlled by assuming a random effect because the variables cannot be introduced. By making such bias corrections, the hypotheses were tested using dummy variables for island groups: (1) islands bridged to the main island of Japan (Honshu), (2) islands not bridged to the main island of Japan (Honshu), (3) the Ogasawara Islands, (4) the Amami Islands, (5) the Okinawa Islands excluding the main island of Okinawa, and (6) the Okinawa main island (see ). These island groups vary geographically. The reference group is the main island of Japan, Honshu, and the other major islands of Japan, including Hokkaido, Shikoku, and Kyushu. The Ogasawara Islands are a group of islands located southeast of Tokyo and are a subprefecture of Tokyo. The Amami Islands are a group of islands located southwest of Kyushu and are part of Kagoshima Prefecture. The main island of Okinawa and the Okinawa Islands combine to form Okinawa Prefecture.Footnote5

Table 2. Summary of averages in the categories of remote islands those who have not graduated from elementary school.

As depicted in , the non-completion of primary education for people living on islands in island groups (1), (2), and (3) is rather low. For island group (1), 0.15% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.11% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education while 0.33% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.19% surveyed in 2010 also did not do so. For island group (2), 0.22% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.15% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education, while 0.33% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.21% surveyed in 2010 also failed to do so. For island group (3), 0.06% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.07% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education while 0% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.12% surveyed in 2010 also did not do so.

However, the non-completion of primary education for people living on islands in island groups (4), (5), and (6) is relatively high. For island group (4), 0.28% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.29% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education, while 0.74% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.51% surveyed in 2010 also did not. For island group (5), 0.74% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.60% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education, while 1.93% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.99% surveyed in 2010 also failed to do so. For island group (6), 0.45% of the men surveyed in 2000 and 0.38% surveyed in 2010 did not complete their elementary school education, while 1.16% of the women surveyed in 2000 and 0.71% surveyed in 2010 also did not.

As shown in , many people in Okinawa Prefecture did not complete their elementary school education. The Okinawa main island and the Okinawa remote islands were battlefields in the Battle of Okinawa in WWII. Not only geographical isolation but also the Battle of Okinawa may have significantly influenced the high rate of non-completion of primary education in these areas.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs)

The estimation results of all estimated parameters are shown as observed multiplicative expressions, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and instead of coefficients (see ). The IRR value shows how many times the dependent variable increases when the variable increases by one unit while the other variables are held constant. For example, for the male population between the ages of 20 and 34, the IRR value is 0.9986, which is not statistically significant at the 5% level. Hence, what can be interpreted from this parameter is that a one-percent increase in the the male population between the ages of 20 and 34 results in 0.9986 times the number of men who did not complete their elementary school education. This is expressed in terms of a multiplier. When expressed as a rate of change, the IRR value minus one equals the rate of change (%). For example, if the IRR value equals 0.9986, minusing one from that value results in (%). This means that a one-percent increase in the male population between the ages of 20 and 34 would result in a

percent decrease in the number of males who did not complete elementary school. It is important to note that if the magnitude of the IRR value is less (more) than one, the rate of change will decrease (increase). The reason for adopting IRRs rather than coefficients is that IRRs are more intuitive for comparison.

Table 3. Estimation results of the random-effects negative binomial regression models.

The IRR value sorted by the most prominent IRR among the island groups , the female groups were the Okinawa Islands (IRR

), Okinawa main island (IRR

), Amami Islands (IRR

), and islands bridged with the mainland (IRR

). The IRRs for the outlying island groups and the Japanese mainland, were compared with the other variables held constant in the model. The magnitude of the IRR for the Okinawa Islands region can be attributed to an island-isolation effect and an effect caused by the Battle of Okinawa. For example, the IRR for the Okinawa Islands was about

times larger than that of the mainland of Japan (reference group). The IRR of island group (4) showed that there were about

times more people who had not completed their elementary education than those on the main island of Japan.Footnote6

However, on the Okinawa main island, there was an additional isolation effect; the incidence of interruption of education was times higher than the effect of isolation of Amami. The multiplier can be calculated as follows:

In the same way, the multiplier can be calculated as follows:

Among men, the IRRs of the Okinawa island groups was (Okinawa main island) and

(Okinawa Islands) times higher than the main island of Japan. Among men on islands bridged with Japan’s main island, the isolation effect was only

times higher than that for men Japan’s main island. When the Battle of Okinawa effect was added to the isolation effect, the number of men who had not completed their elementary education was

to

times larger than the isolation effect alone.

Discussion

Are those who did not complete elementary school now in a state of poverty?

Estimation results show that those who have not completed their primary education are living in relative poverty. Controlling for age structure, marital status, spousal bereavement, the proportion of unmarried people, and those who are living in a facility, it was found that an increase in the population in public housing households has a positive relationship with the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education. The IRR value for the non-completion of elementary school education for males living in public housing is 1.0189, while the value for females is 1.0182. In other words, a one-percent increase in the number of public housing households in the district would result in a 1.89% and 1.82% increase in the number of males and females, respectively, who did not complete their primary education. According to Tajimi (Citation2015), there is a high correlation between public tenancy and low income; therefore, living in public housing is a proxy measure of economic poverty. Examining whether the population of those living in public housing includes those who did not complete their compulsory primary education, there is a high correlation between the two groups. Since the number of people living in public housing can be considered a proxy indicator for people living in poverty, it was concluded that those living in poverty and those who did not complete their elementary school education comprise a partially common group.

Are there foreigners among invisible people in Japan?

In districts where the ratio of foreigners was high, the number of invisible people increased for both men and women. A one-percentage point increase in the foreign male population results in a 1.91% increase in the number of males who did not complete their primary education and a 2.06% increase in the number of females who did not complete elementary school. In Japan, foreigners are granted some kind of residence permit by the state. However, unlike the parents of Japanese children, the parents of children with foreign roots are not required to send their children to primary school. These children are only allowed to receive education only if they or their parents wish them to do so.

Japan’s lack in requiring children of foreign nationals to attend elementary school is based on a current interpretation of the Japanese Constitution. The rights afforded to Japanese and foreign residents are different. One such example is the article on the right to receive primary (six years) and secondary (three years) education. Since the Constitution of Japan does not mention the right to education and the obligation to provide general education for children of non-Japanese nationals, Japanese public education allows children of a foreign nationality to attend school only but does not require them to do so. As a result, some children of foreign nationals do not attend school even though they are of school age (Kojima, Citation2011).

Did the battle of Okinawa in WWII have an impact on the completion of one’s elementary school education?

Estimation results show that the war disrupted elementary school. From the calculation of the IRRs for the islands groups, the effect of the Battle of Okinawa on women is 2.878 to 3.627 times greater than on women in islands groups that are isolated but have not experienced ground warfare. While the effect of the Battle of Okinawa on men is 2.372 to 3.050 times greater than on men in islands groups that are isolated but have not experienced ground warfare. Thus, for both women and men, war represented a significant factor that disrupted their elementary school education.

The reasons behind the children not going to school are revealed by an oral history of the Battle of Okinawa: Testimonial records show that women and children worked in place of their parents to provide for their families. As per the life history of a woman born in 1935 (Sukore, Citation2015, pp. 131–132), her mother died soon after she was born, and her father was killed in the Battle of Okinawa. It is assumed that many others had such experiences, even if they were not recorded as life histories.

Limitations

The limitation of the current research was not enough for the detailed data collection in the area of the Battle of Okinawa. It is important to check whether there are significant differences between the cohort groups of school-aged children who attended elementary school after the Battle of Okinawa and during the period of US occupation between 1945 and 1972, and other regions. There is scope for further research using national census data to improve causal inferences about the presence of people who did not complete their elementary school education created by the breakdown of the family structure after the Battle of Okinawa.

Contributions

The contributions of this study to the literature in the field of lifelong learning is fivefold.

First, this study demonstrated the use of quasi-experimental panel data analysis to determine the characters of people who did not complete their elementary school education by regions. Essentially, it would be ideal to be able to show how the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education changed between the pre-and post-war periods. However, there is no relevant numerical data from the WWII period. There may also be factors other than war that caused the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education to fluctuate. In such cases, panel data are used to make quasi-experiment and estimate intervention effects based on the difference between facts and counterfactuals under the assumption.

Second, this study used census data that are disaggregated by the district for all residents. By using two years of data from more than 100,000 districts nationwide, a detailed analysis was possible.

Third, this study used count data analysis to eliminate sample distortions. Since most of the districts have zeroes, it is necessary to devise an estimation method. This study addressed this issue appropriately.

Fourth, the strength of this study’s analysis is the comprehensiveness of the data: the Japanese version of the PIAAC survey excludes foreign residents in Japan and people with severe disabilities from the survey, whereas the census we use includes all people living in Japan. In other words, census data allowed the inclusion of socially vulnerable groups.

Fifth, since Boeren (Citation2017) suggested considering geographical differences as a reason adults participate or do not participate in lifelong learning activities, this study considered geographic factors, such as living in isolated islands. The estimated results suggest that the Battle of Okinawa during WWII significantly disrupted elementary school education in Japan, even if other factors are considered. However, it is understood that the effects of the Battle of Okinawa with a dummy variable of geographical location are rudimentary, and caution is needed in showing causality because so much has happened in the roughly 80 years since the war ended in 1945. However, the first step was to identify the characteristics of the people living in the districts by adding control variables and conducting regression analysis. This group difference identifies environmental factors specific to remote islands and factors from the Battle of Okinawa. As other life history studies have shown, the effect of not being able to complete elementary school continues even after the end of the Battle of Okinawa.

Conclusion

Though adult education in Japan ranks high in the PIAAC survey, there is a group of people who did not complete their compulsory education: invisible people. The following categories of invisible people have been identified: (1) those who were unable to complete their schooling due to war or poverty, (2) those who did not attend school in their childhood, and (3) foreigners living in Japan: immigrants, refugees, or foreign residents. In contrast, the Population Census is an all-counts survey of citizens residing in Japan and, therefore, can capture foreign nationals who did not complete their elementary school education. This study focused on three questions regarding the characteristics of invisible people in Japan: (1) Are those who did not complete their elementary school education now in a state of poverty? (2) Are foreigners among the invisible people in Japan who did not complete their elementary school education? (3) Did the Battle of Okinawa during WWII have an impact on the number of people who did not complete their elementary school education? To address these three research questions simultaneously, we used a random-effects negative binomial regression model, which is a form of regression analysis. The estimation results showed that (1) those who have not completed their elementary school education are living in relative poverty; (2) in districts where the ratio of foreigners was high, the number of invisible people increased for both men and women; and (3) the Battle of Okinawa in WWII had a significant effect on people’s non-completion of primary education with women being more negatively affected than men in remote areas. Therefore, additional support through lifelong learning activities is needed to counter such structural factors in remote areas. We recommend conducting comprehensive research using census data because citizens who have not completed their primary education due to environmental and war-related factors probably also exist in other countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Takehiro Usui

Takehiro Usui holds a Ph.D. degree in Economics from Kobe University, Japan. Currently, he is a Professor in the Faculty of Economics, Soka University, Japan. He has researched people who could not complete basic education, often using large-scale national census, and sometimes does life history research.

Mitsuko Chikasada

Mitsuko Chikasada holds a Ph.D. degree in Agricultural, environmental, and Regional Economics, and Demography from the Pennsylvania State University. She is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Economics, Soka University, Japan. She has been involved in research using geospatial analysis in the fields of agricultural economics and demography. In this research, she analyzed the geographic distribution of municipalities using Arc GIS to examine the impact of environmental policies of neighboring municipalities on the municipality in question.

Edwin Aloiau

Edwin Aloiau holds an Ed.D. degree in Education from Temple University. Currently, he is a Professor in the Faculty of Economics, Soka University, Japan, and the coordinator of the faculty’s International Program. He focuses on the design, implementation, and enhancement of intensive academic English language programs; second language teaching methodology and materials design; and enhancing student motivation to learn.

Notes

1. Ido (Citation2016) estimated that there are 10,000 people who are not recorded in a family register (koseki) over the last 20 years because each year approximately 3,000 births are not recorded in a family register with 2,500 of these births eventually registered through the courts. No koseki registration arises if the child’s birth is not registered within 300 days after birth. This could happen because of fear of abuse from the child’s father. The child becomes ‘invisible’ to the school board and does not receive an education.

2. The software used was ArcMap 10.8.1. The map data used is from Statistics of Japan (e-Stat is a portal site for Japanese Government Statistics), available at https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/ We downloaded the boundary data registered in Statistics on a Map (JSTAT MAP). As for the map data, we obtained district level boundary data issued by the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, which is a map of the smallest administrative division. Then, we integrated the boundary data and the density of people who did not complete elementary school using software called ArcGIS and output on a map.

3. In this study, we adopted a random effects model. Since the census is a whole population survey and an unbiased sample, we do not consider unobservable individual differences as fixed effects, but rather, as variables that follow an independent probability distribution. Since random effects are probability distributions independent of the error term, we tested using categorical groups as dummy variables.

4. Readers might think that the fixed-effect model should be used in panel data analysis, but there is a caveat to the fixed-effects negative binomial regression (FENB). Using the conditional maximum likelihood estimator of the negative binomial with fixed effects, introduced by Hausman et al. (1984), does not necessarily remove the individual fixed effects in count panel data (Allison & Waterman, Citation2002; Guimarães, Citation2008). To check the validity of the model, Guimarães (Citation2008) proposed a score test, but it does not apply to a model similar to ours with a short fiscal year. Therefore, we used the random-effect model instead of the FENB.

5. The dummy variables were set as the Okinawa main island and Okinawa Islands separately because the population size of Okinawa main island is over one million people.

6. This is what the lower limit of 1.00, which means that there is no significant difference with the reference group, and the upper limit of 1.769, means. Islands that are not bridged with the mainland are not different from the mainland because it was not significant at the 5 percent level; that is, the IRR is not statistically significantly different from 1. The IRR of Amami, a highly isolated representative, was .

References

- Akaike, H. (1978). A bayesian analysis of the minimum AIC procedure. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 30(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02480194

- Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. (2002). 7. Fixed-effects negative binomial regression models. Sociological Methodology, 32(1), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9531.00117

- Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Boeren, E. (2017). Understanding adult lifelong learning participation as a layered problem. Studies in Continuing Education, 39(2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2017.1310096

- Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (1998). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge University Press.

- Guimarães, P. (2008). The fixed effects negative binomial model revisited. Economics Letters, 99(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2007.05.030

- Hosaka, T. (2019). Gakkou wo choki kesseki suru kodomo tachi: Fukoukou negurekuto kara gakkou kyouiku to jidou fukushi no renkei wo kangaeru [children who are absent from school for a long period of time: Considering the collaboration between school education and child welfare from the perspective of truancy and neglect]. Akashi Shoten.

- Ido, M. (2016). Mukoseki no Nippon jin [Japanese who have no family register]. Syuueisya.

- Iwatsuki, T. (2019). What is ‘educational support’ for youth in social difficulties?: A qualitative study of support groups for literacy learning in Japan. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 38(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2019.1648575

- Kojima, Y. (2011). Gakurei wo choka shita gimukyoiku mishuryo no gaikokujin jumin no gakushuken hoshou [A study on the right to learn of foreigners who were over school age and had no access to the compulsory education]. Journal of Volunteer Studies from. 11, 21–33. Retrieved July 26, 2021 http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110009425444

- MIC (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). (2000). National population census, 2000. Statistics Bureau of Japan.

- MIC (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). (2010). National population census. Statistics Bureau of Japan.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science, and Technology (MEXT). (2016). Chugakkou yakan gakkyu ni kansuru jittai chousa ni tsuite [survey on evening classes at junior high schools]. MEXT.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT). (2019). Gaikokujin no kodomo no shugaku no sokushin oyobi shugaku jokyo no haaku to ni tsuite [promotion of school attendance and monitoring of school attendance of foreign children]. MEXT.

- National Air Raid Victims Liaison Council. (n.d.). What damage did the Okinawans suffer during the ‘battle of Okinawa’? https://www.zenkuren.com/aboutus_qanda/aboutus_q4.html

- National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). What PIAAC measures. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/measure.asp#:~:text=In%20PIAAC%2C%20results%20are%20reported,into%20five%20levels%20of%20proficiency.

- NIER (National Institute for Educational Policy Research). (2013). PIAAC Japan report: Summary of findings.

- OECD. (2019). Skills matter: Additional results from the survey of adult skills. https://doi.org/10.1787/23078731

- OECD. (2023). PIAAC Technical Standards and Guidelines. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/PIAAC-NPM(2014_06)PIAAC_Technical_Standards_and_Guidelines.pdf

- Sukore, S. (2015). Machikanti: Ugokihajimeta manabi no tokei [A message from the grandmother and grandfather who attended a night junior high school in Okinawa]. Koubunken.

- Tajimi, S. (2015). Function of Public Housing in the Regional Housing Market – Analysis of deviation of public housing in the market. Journal of Architecture and Planning, 80(711), 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.80.1179

- Tanada, Y. (2011). Nihon no shikiji gakkyu no genjo to kadai: 2010 nendo zenkoku shikiji gakkyu jittai chosa no kekka [The current state and issues of buraku literacy classes in Japan: The results of ‘The National Buraku Literacy Class Survey 2010’]. Buraku Liberation Research, 192, 2–15.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government Human rights Devision. (n.d.). Buraku discriminartion. https://www.soumu.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/10jinken/minna/kadai_5/

- UNESCO. (1964). Literacy and education for adults: Research in comparative education. International Bureau of Education.

- Usui, T. (2020). Individuals with incomplete basic education on Japanese islands: Using district-level data from the population census. The Journal of Island Studies, 21, 53–74. https://doi.org/10.5995/jis.21.1.53