ABSTRACT

This scoping review focuses on student veterans’ transition and reintegration into education and presents key themes in international student veteran research. Grounded in a literature search in ERIC, Scopus, and Web of Science, our scoping review includes 137 articles across research disciplines. It covers publications from the last 15 years, with a transnational focus. Analysis of these articles resulted in two key themes: (1) Transition challenges of student veterans, including differences in military and academic learning, mental health challenges in class and on campus, and social interaction with non-veteran students and faculty. (2) Support efforts for student veterans, including becoming a veteran-friendly campus, academic support, mental health support, and social support. In addition to discussing these key themes across articles, we map prevalent conceptual frameworks, and discuss commonly used definitions of student veterans, veteran demographics, as well as descriptions of military education culture and academic education culture that we found in the literature. The subsequent discussion highlights that the academic success of student veterans often focuses on metrics, which highlights the qualification function of education, while disregarding the socialisation of veterans in education and their development of relative autonomy.

Introduction

Student veteran experiences and veteran support are subject to increasing attention (Cable, Cathcart, et al., Citation2021; Castro et al., Citation2021). This article examines the literature on veterans’ experiences of transition and reintegration into educational institutions and provides a discussion of approaches to student veteran support. More than 43 NATO countries and partners have engaged in war zones since 2001, including the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, France, and Denmark. Subsequently, these countries face an ethical task in supporting veterans who return to their home countries, continue their civilian life, and often enrol in post-compulsory education. Our discussion of their experiences in educational institutions aims to enable these institutions to comprehend the situation of student veterans and prepare support for future veteran cohorts.

Existing literature reviews discuss the situation of student veterans exclusively in the United States. From the first review that we were able to identify (Bichrest, Citation2013) to the most recent one (Moeck et al., Citation2022), the transition of veterans from military service to education is described as a process that requires major adjustments. US studies highlight that challenges arise due to combat-related injuries, mental health symptoms, and social interaction with peers and faculty, and affect academic performance (Barry et al., Citation2014; Borsari et al., Citation2017; Ghosh et al., Citation2020). Moreover, studies argue that student veterans require support related to issues of mental health, alienation, social isolation, and academic performance, and that their unique skills often remain unrecognised (Blaauw-Hara, Citation2016; Sullivan & Yoon, Citation2020). Managing these issues requires educational institutions to create a space in which student veterans feel comfortable in shaping social relations with teachers, staff, and non-veteran student peers. Enabling student veterans’ social relations on campus and in the classroom reduces veterans’ experiences of alienation and social isolation and improves student well-being and mental health (Benbow & Lee, Citation2022). Further, these reviews highlight that the research field lacks a unified terminology, as examined challenges and processes are referred through a broad range of concepts, like transition, reintegration, adjustment, and acculturation. And while the most recent review (Moeck et al., Citation2022) acknowledges the importance of studies beyond the US, there is to date no review that links insights into the situation of student veterans from US studies with studies from other countries. This review is, to the best of our knowledge, the first review that focuses on student veteran research beyond the US and relates this research to the established field of study in the US.

This literature review addresses a research gap, as it includes studies on student veterans of NATO countries beyond the US and their allies. As many NATO countries have engaged in war zones over the last 20 years, veterans who return to civilian society and engage in education play an increasingly important role. Addressing NATO’s recent call for increased transnational knowledge exchange (Castro et al., Citation2021), we illustrate similarities and differences in the situation of student veterans across NATO countries and their allies. Further, we review differences, for example concerning definitions of the student veteran, highlight common conceptual frameworks used in student veteran research, and illustrate key assumptions that shape empirical perspectives on student veterans. Continuing the work from previous literature reviews, we also include the most recent studies on US veterans, giving credit to the fact that more than half of the articles found through our systematic search were published after 2018.

This literature review aims to inform future research that explores veterans’ experiences of transition into education. We use a scoping literature review approach, defined as an assessment of the breadth and scope of available literature in a given field, regardless of study design (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Grant & Booth, Citation2009). This approach enables us to identify the reviewed literature’s findings, conceptual nature, themes, as well as research gaps (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Our intended audience includes researchers from non-US NATO countries and their allies, as well as practitioners, teachers, and institutions. As the review will show, research is often limited by the scarcity of national literature that can inform studies on student veterans and may benefit from transnational scoping reviews like this one. Our paper uses the term student veteran broadly to be inclusive towards different definitions found in the literature, such as student service members and veterans (Barry et al., Citation2014). This enables a broader scope for transnational comparison of the often heterogeneous, nation-specific definitions of veteran subjects. The objective of the article is to map, summarise, and critically review research findings. Specifically, we address the research question: What are common themes in international research on student veterans’ transition experiences when re-entering education?

Our paper is organised as follows: First, we describe the methodology used for this scoping review. Subsequently, we present information about the included studies, the countries represented in this review, the dominant conceptual frameworks, key definitions in the field, and relevant student veteran demographics. The 137 studies we cover in our review provide the foundation for the next section, which presents characteristic themes in the field and a critical discussion of findings. Based on these findings, we discuss the prevalent metrics-centric definition of academic success and argue that non-US researchers may advantageously consider a different definition that focuses on self-reflexive activities to frame future research on student veterans.

Method

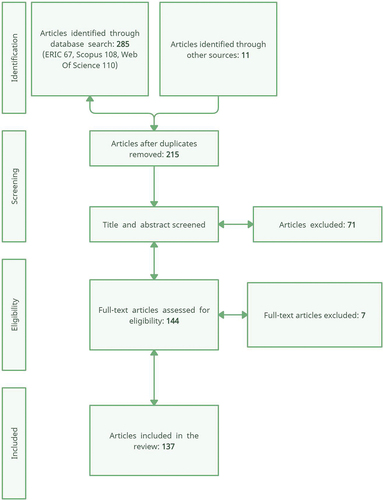

The scoping review was conducted from May – September 2023 by the two authors, white males, one with and one without military experience. For the review, publications were selected by two criteria: Publications are (1) published within the last 15 years, and (2) published in peer-reviewed, digitally available scholarly journals. Including publications from the last 15 years allowed us to cover significant developments, such as the influx of papers on student veterans after the Post-9/11 GI Bill from 2008, and the UK’s Armed Forces Covenant (Taylor, Citation2011). illustrates the process from identification to inclusion of publications.

Search string

We aimed for an inclusive search string with synonyms to avoid publication bias. Five more decisions influenced the search string: First, student, education, and synonyms directed our focus to research situated in educational institutions. Second, the combination of veteran and military excluded hits on non-military veterans, such as police officers and nurses. Third, the transition parenthesis aims to avoid bias with respect to how publications refer to concepts such as transition, reintegration and integration. Fourth, the filter Not in full text was applied. This filter narrowed the search down to contents of titles and abstracts rather than full-text documents, which reduced search results from over 15,000 to below 300. This enabled us to conduct the review within a four-month timeframe. Fifth and finally, the search string was written in English, thus excluding non-English literature. This exclusion may limit our findings significantly, as 43 countries participated in the International Security Assistance Force missions in Afghanistan, English is the official language in only three of them, and much contemporary veteran research is done on a national level (Castro et al., Citation2021). Despite being aware of this limitation, we ourselves are limited in our language abilities and are not able to include research on student veterans beyond our language competencies. We do hope that this limitation can be addressed through transnational cooperation. Based on these considerations, we used the following search string:

Database selection

Three databases were included in the search: Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Scopus and Web of Science. ERIC was chosen due to its focus on educational research and high-quality standards that are maintained through manual content and relevance checking. Scopus and Web of Science were chosen as additional databases due to their broad scopes, which complemented ERIC, and their balanced representation of research disciplines, which enabled a review of different research designs. The search results initially provided 285 articles: 67 from ERIC, 108 from Scopus, and 110 from Web of Science Further manual search resulted in 11 additional articles, aiming at addressing three gaps in the research field: (a) Articles concerned with countries underrepresented in the state of the art enabled us to review research based in these countries. (b) Articles that focused on faculty perspectives provided the possibility to compare these perspectives with veteran perspectives. (c) Articles on student veterans that were highly cited throughout the past 15 years.

Post-search eligibility criteria

After articles were downloaded, we removed 81 duplicates. Two eligibility criteria guided the exclusion of further articles: (1) Articles had to fit the topic of transitioning into civilian education, and (2) articles had to focus on the contexts of upper secondary education or higher education. The first criterion was applied to exclude articles on the military education of soldiers. The second criterion was applied to exclude articles that focus only on specific topics such as online education. Articles were manually screened to meet these criteria, leading to the exclusion of 71 articles. Assessment of full texts resulted in flagging further articles for exclusion. Flagging was initiated by one researcher, followed by an assessment from the other researcher, which resulted in the exclusion of 7 articles. Ultimately, 137 articles were included in the review.

Charting, collating, and summarising information

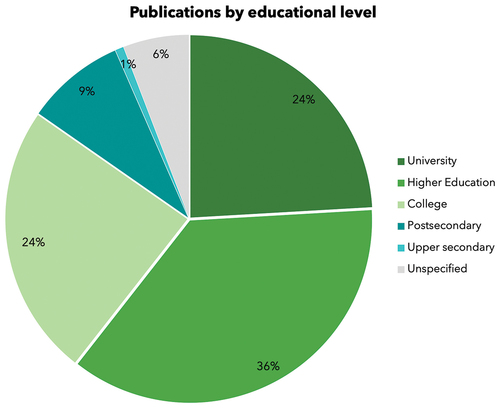

With respect to classifying publications by educational level, 85% of publications focussed on higher education. More specifically, 24% of the included publications (n = 33) were dedicated to university education, i.e. institutions with high research activity and a graduate enrolment profile. A comparable number of publications (n = 33) focused on colleges education that predominantly provide bachelor and master level degrees. Notably, the remaining majority of publications that had a dedicated research focus on higher education (n = 50) did not specify the level of education in any more detail, which indicates that veteran research is at times unprecise with respect to the concrete educational context on which it sets focus. Similarly, studies with a focus on postsecondary education (n = 12) did not provide any more precise specification, e.g. on the type of vocational education or training provided. However, the educational context of studies should be considered as relevant, because it reflects different academic cultures that impact veteran experiences. provides a visual overview of publications sorted by educational level.

We summarised information from each article into a template. The template included publication author; year; title; country of study; aims of the study; conceptual framework(s); data collection and analysis approach(es); key definitions; and finally, findings, which were inductively grouped into themes such as Challenges and Support Efforts. Next, we collated the data into tables and graphs. This step shed light on main interests, tendencies and gaps in the data. First, we counted the countries of study. Second, we built tables in which we grouped conceptual frameworks. Third, we built an overview of key definitions, which considered their frequency of occurrence and level of detail. Fourth, we built an overview of demographics. To conclude the collation phase, we counted how often a particular empirical theme was mentioned by an author, resulting in 30 thematic groups. Ultimately, we summarised information across all articles. Each author developed initial themes and subthemes individually. We met to condense them into second-order themes, which reflect in Results subchapter titles.

Publication dates and citation patterns

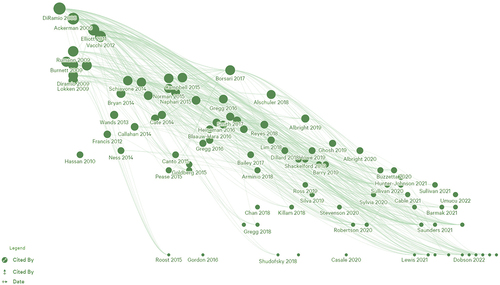

Our analysis of publication dates and citation patterns (as shown in ) can serve as a starting point to understand the development of influential conceptual frameworks, definitions, and demographics in student veteran research. The most cited articles are DiRamio et al. (Citation2008) with 753 citations, Ackerman et al. (Citation2009) with 546, Elliott et al. (Citation2011) with 397, and Vacchi (Citation2012) with 330 citations. These publications appeared at an early point in the history of student veteran research, yielding a number of citations that remains unsurpassed to date. The number of publications increased by almost 50% from 2018 to 2023, resulting in a more diversified research field: After 2018, studies employed a wide range of conceptual frameworks to illustrate the situation of student veterans, making the identification of prevalent conceptual frameworks more difficult. At the same time, this development enables researchers to develop more sensible, multifaceted research approaches. While older, highly cited articles offer an important starting point for exploring influential ideas, our citation analysis indicates that exploring the more recent, lesser-cited articles may result in a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the situation of student veterans.

Results

Nearly 90% of articles included in this scoping review focused on student veterans in the US (n = 122). However, we also identified 7 articles that were non-country specific through our search, as well as 8 articles that focused on student veterans in countries other than the US, namely Australia (Harvey et al., Citation2018), Canada (Ogrodniczuk et al., Citation2021), Denmark (Pedersen & Wieser, Citation2021), Ukraine (Sokurianska et al., Citation2019), and the UK (Cable, Cathcart, et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Matthews-Smith et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2020). The scarcity of studies on student veterans outside the US indicates how little we know about student veterans in most NATO countries. It also points to the relevance of US studies to inform research in other countries, as well as the importance of comprehending the context of US student veterans, due to their specific veteran policies and demographics. The surplus of US studies also requires us to consider what can be generalised from US findings, how the situation of student veterans is different outside of the US, and how conceptual frameworks can be adapted to inform research in non-US contexts.

The following section offers a comprehensive description of definitions, demographics, and military identities that serve to profile student veterans. The section explores various international definitions of student veterans, examines demographic trends and characteristics in different countries, and discusses the unique cultural challenges and resilience of student veterans relevant for understanding their transition from military to academic environments.

Definitions of student veterans

Definitions of who counts as a veteran are used to determine whether veterans are entitled to special student benefits and services. While no uniform definition of student veterans exists across countries, transnational comparison shows three approaches to define veterans: (1) The most inclusive approach considers all personnel who previously served in the armed forces for one day or more as veterans. Such an approach is used in the UK, where veteran status is obtained regardless of service type (regular or reserve) or deployment status (Cable, Fleuty, et al., Citation2021). (2) A deployment-oriented approach considers all personnel that were deployed to international missions as veterans, regardless of active-duty status. Such an approach is used in Denmark (Pedersen & Wieser, Citation2021). (3) A post-service approach, as used in the US, bestows veteran status to personnel after leaving military service under conditions other than dishonourable (Tomar & Stoffel, Citation2014). These differences could create difficulties for comparative research on student veterans and may be complicated further by studies that do not include a clear definition. In our review, only 24 out of 137 articles (17%) were based on a clear definition of student veterans.

Student veterans are defined as ’any student who is a current or former member of the active-duty military, the National Guard or Reserves regardless of deployment status, combat experience, legal veteran status, or GI Bill use’ in US research (Vacchi, Citation2012), and much of the literature relies on this US definition. Alternatively, some articles use the term student service members and veterans (SSM/V) to be more inclusive to military service members who are not veterans (Barry et al., Citation2021). In the US, the term SSM/V includes all students in the National Guard, Reserves, or active duty (Hodges et al., Citation2022). While the distinction between student veterans and SSM/V is relevant in the US context, that might not be the case in all countries. An alternative, Australian definition of a student veteran is ’any person who has served in the military who is in higher education’ (Harvey et al., Citation2018). Yet another definition is used in the Ukraine, where the category veteran student includes all students who are ‘a current or former member of the Active Duty Military, the National Guard, Reserves or other military formations and law enforcement agencies who could take part in combat actions on the territory of their own or other states’ (Sokurianska et al., Citation2019).

Choices in defining student veterans can have a significant impact on research: A focus on deployed personnel is relevant from a mental health perspective because it emphasises challenges that relate to deployment, e.g. exposure to combat, physical injuries, and exposure to traumatic events that can lead to PTSD symptoms. On the other hand, a focus beyond deployed personnel is relevant from a sociocultural perspective because it enables highlighting reintegration challenges that relate to military training, e.g. separation from civilian society, assimilation into a military habitus, and identity transformation.

Prevalent conceptual frameworks

Conceptual frameworks in student veteran research are key to making sense of veterans’ experiences in education, as they provide a focus but at times also limit understanding of their situation. Within the scope of our review, 20% of articles discuss themes such as mental health or reintegration without referring to an explicit framework. The remaining 80% of articles employ dedicated conceptual frameworks. Our analysis indicates that the following three conceptual frameworks are most prevalent in veteran research: (1) Transition frameworks that focus on changes in which student veterans experience education over time. (2) Mental health frameworks that focus on symptoms of psychiatric disorders amongst student veterans and how these affect educational performance. (3) Reintegration frameworks that focus on conflicts between members of different groups and how these conflicts are socially and culturally negotiated. The following paragraphs offer a critical discussion of the focus that each of these three frameworks provide.

Within transition frameworks, Schlossberg’s transition model is the most used theoretical reference. Here, transition is defined as any process that results in changed relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011b). This process is characterised as consisting of three phases: moving in, moving through, and moving out (Bell, Citation2017). The ability to engage in this process of transition is influenced by four key factors (4S): self, situation, support, and strategies (Lewis & Wu, Citation2019). Despite its popularity, Schlossberg’s transition model has received some criticism, as transition is seen as the result of facilitating factors on the individual and organisational levels, whilst processes of social interaction and policy-level factors are not integrated into the model (Elnitsky et al., Citation2018). In contrast to the Schlossberg model, William Bridges (in Bell, Citation2017), another transition theorist, adds that transition may be understood through disengagement, disidentification, disenchantment, and disorientation (the four D’s), and that transition starts with an ending rather than a new beginning.

The most prevalent mental health framework in veteran research is DSM-5 (e.g. Hinkson et al., Citation2021; Reyes et al., Citation2022). The four most frequently cited conditions are Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and suicide risk. These DSM-5 indexed conditions of student veterans are described as follows: (1) TBI is a brain injury that stems from traumatic events, e.g. bomb blasts. It is the only neurological condition on the list and commonly causes neurocognitive symptoms, persistent disorientation and confusion, which may impair the ability to concentrate and learn. (2) PTSD is characterised by the development of certain symptoms following exposure to one or more traumatic events, where ‘recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive recollections of the event’ occur. (3) Depression, a term often used in student veteran research, describes a range of feelings, from sadness to clinical conditions. However, usage of the term does not in all cases equate to the clinical condition known as Major Depressive Disorder. (4) Suicide risk of student veterans is often assessed in a differentiated matter that distinguishes between suicidal ideation, suicide thoughts, having a suicide plan, and suicide attempts. In student veteran literature, PTSD is associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Hinkson et al., Citation2021), while the possibility of suicidal behaviour exists during major depressive episodes at all times (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013, p. 167). Across all these four conditions, we found that articles within the search scope frequently do not refer to frameworks such as DSM-5 when discussing mental health conditions. More specifically, only 8 out of 80 include such a reference.

Reintegration frameworks rely on a wider range of concepts, making it difficult to pinpoint clear preferences in student veteran research. A significant part of research is based on identity development models, e.g. Marcia (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011a) and Jones & McEwen (K. Jones, Citation2013). Beyond identity concepts, a wider range of studies uses acculturation models, e.g. Berry (Citation2005, in Arminio et al., Citation2018). Here, acculturation is defined as ‘the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members’ (Berry, Citation2005, p. 698). In acculturation, the simultaneous orientation towards one’s own and other cultural groups produces ‘a potential for conflict, and the need for negotiation in order to achieve outcomes that are adaptive for both parties’ (Berry, Citation2005, p. 697). Four acculturation strategies characterise such processes: assimilation/melting pot, separation/segregation, marginalisation/exclusion, and integration/multiculturalism. A smaller range of studies relies on other conceptions of acculturation but often rely on social constructivist positions that remain implicit. This situation may require that researchers who use reintegration frameworks familiarise themselves with available possibilities to come to informed theoretical decisions.

Prevalent data collection methods

Veteran research draws on a wide variety of data collection methods. Analysis of research methods across publications revealed that 59 articles were grounded in qualitative methodologies, while 44 articles employed on surveys, and 13 utilised a mixed-method design (see ). Based on the research included in this scoping review, we can see a tendency that the prevalent conceptual frameworks used in an article correlates with a preferred data collection strategy: Articles that employed a transition framework mainly employed interviews (55% of articles) and surveys (30%) as their data collection methods. Similarly, articles adopting a mental health framework favoured quantitative surveys (87% of articles). Finally, articles that relied on a reintegration framework mainly employed interviews (54%), followed by quantitative surveys (27%) and mixed-method approaches (13%). Evidently, research adopting a mental health framework is often combined with surveys to provide a large data sample, and indeed, 50% of the articles uses data samples of 200 participants or more. At the same time, the reliance on large data samples can be seen to limit an exploration of personal or contextual elements that are critical to arrive at a nuanced understanding of student veteran experiences. In contrast, research from transition and reintegration frameworks frequently combines qualitative depth and quantitative data collection methods, thus purveying a potentially more nuanced qualitative picture, while at the same time substantiating findings through large survey data sets that include between 200 and 700 participants. provides a detailed overview over different data collection methods used in articles.

Table 1. Data collection methods used in articles.

Demographics

Demographics of student veterans provide insights into similarities and differences of veteran cohorts. Considering demographic variables (average age, age difference, population changes, gender, and ethnicity) has proven relevant when identifying challenges in the US context, and comparing these variables on an international level is indispensable for effective research on student veterans. However, not all studies offer detailed demographics. Within the scope of our search, we could only get hold of student veteran demographics from the US and Australia. The following discussion is thus limited to these countries.

In the US, student veterans constitute nearly 4% of the student population in higher education (Hart & Thompson, Citation2016). The average student veteran begins higher education at the age of 25, and 85% of student veterans are older than the average higher education student, aged 18–23 (Beck, Citation2020). Approximately 73% of student veterans are male, 27% are female, 60% are white, 18% are black, 12% are Hispanic, and 3% are Asian (Falkey, Citation2016). Female veterans are younger than their male colleagues on average, and while 30% of female veterans hold a bachelor’s degree, this is only true for 20% of their male equivalents (Heitzman & Somers, Citation2015). Additionally, most are financially independent, married, divorced, and/or parents (Mahoney et al., Citation2023). In Australia, demographics are based on a national survey (n = 240) of current and former student veterans in higher education (Harvey et al., Citation2018). Approximately 80% of student veterans in the survey were male, and the age distribution of student veterans were measured in the following categories: 20–29 years old (21% of respondents), 30–39 years (35%), 40–49 years (28%), and finally, 50+ years (16%). Limitations of these demographics include that (1) the amount of student veterans in the student population is unaccounted for, perhaps in part due to several existing definitions of a veteran, which offer disparate starting points for research, and (2) no data in our review scope looked exclusively at current Australian student veterans. Thus, interpretation of these demographics to the situation of current student veterans is problematic.

The student veteran population has increased noticeably since 2001 (Saunders et al., Citation2023). In the US, more than 1 million student veterans have enrolled in higher education (Cate et al., Citation2017). While officers commonly have college degrees before entering the military, the situation is different for the enlisted ranks, where only 18% of male veterans and 27% of female veterans are reported to have a bachelor’s degree (Morgan et al., Citation2023). Female veterans are more likely to attend higher education and constitute 27% of student veterans, while they constitute only 8.5% of veterans in the US (Samson, Citation2017). 72% of female veterans and 66% of male veterans pursue education, which makes women 51% more likely to attend higher education (Morgan et al., Citation2023). In Australia, available demographics offer different insights. For instance, 66% of student veterans had not disclosed their veteran status to their university, while 33% reported a disability that might affect their studies. Furthermore, their primary motivation for higher education was to improve career prospects. The motivation to enrol in university was not encouraged by others in 40% of student veterans, which ‘suggests high levels of self-motivation among this group, but could also reflect isolation, or the low expectations of family/friends’ (Harvey et al., Citation2018, p. 20). Overall, demographic data indicates that US student veterans are a highly heterogeneous group, which makes it difficult to portray ’the average student veteran’ (Arminio et al., Citation2018), and available demographics make transnational comparison difficult with their limited coverage and disparate definitions of veterans.

Student veteran identity between military and academic cultures

Student veterans are commonly seen to uphold a military culture after they leave military service, consisting of a distinct set of habits and beliefs that instils them into an ethos of discipline, teamwork, and a commitment to complete tasks (Blaauw-Hara, Citation2016; Osborne, Citation2013). This military culture develops through military training but also through experiences of being relocated, separated from family and friends, on non-stop on-call duty, and becoming part of a care-taking structure that provides a clear line of command, directions, and services. Military experiences of endurance and survival result in resilience in many student veterans (Hassan et al., Citation2010). However, differential studies highlight that resilience is not a static personality trait but rather a dynamic process that differs significantly amongst student veterans, where short service time leads to lower resilience and greater odds of developing mental health conditions (Rice et al., Citation2016). Consequently, some student veteran groups show both lower and higher resilience scores than non-veteran students (Reyes et al., Citation2018). Overall, studies report that entering military culture is perceived as a forceful process that imprints a strong military identity onto student veterans. While valued in the military, this identity is very different from the educational culture that institutions value in higher education students (DiRamio & Jarvis Citation2011a; K. Jones, Citation2013).

Transition challenges

Veterans are often challenged when transitioning from military education culture into academic educational culture. These challenges reflect in the completion rates of student veterans, which are below average (Dillard & Yu, Citation2018; Hart & Thompson, Citation2016). The following sections provide an overview of three common themes that relate to veteran challenges across the reviewed studies: (1) Differences in military and academic learning, learning contexts, and social roles, (2) mental health challenges in class and on campus, and (3) social interaction with non-veteran students and faculty. Beyond these challenges, some studies also went beyond deficit-focused approaches, highlighting that student veterans have qualities that contribute to the learning environment and enable them to overcome challenges (Ness et al., Citation2014).

Differences in military and academic learning, learning contexts, and social roles

Differences in military and academic learning, learning contexts, and social roles make it difficult for student veterans to navigate and perform in academia. Moreover, US studies highlight that student veterans have below-average writing skills already before entering the military (Ott, Citation2020), which puts student veterans who re-enter education in a twofold disadvantaged position. In line with US findings, a UK study finds the level of literacy skills amongst student veterans to be significantly lower than their student peers, indicating that more than 1,000 UK veterans had a reading ability of an 11-year-old or below (Cable, Fleuty, et al., Citation2021). One source for veterans’ poor literacy skills is seen in the communication style promoted in military service, favouring a fragmented, itemised writing style that is unfit for academia (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011c).

The shift from military learning to academic learning is another field that poses challenges. Military learning relies on uncritical rote learning, behaviouristic drills, and hands-on exercises, while academic learning prioritises critical thinking and higher-order thinking skills, which are both necessary for reading literature and participating in academic discussions (Hunter-Johnson et al., Citation2020; Killam & Degges-White, Citation2018). Consequently, several studies highlight that the shift towards academic learning is demanding for many student veterans, as it requests them to control their attention in a way that is very different from their military practice (Jenner, Citation2019).

Student veterans also experience a shift in the learning context. The military learning context is highly structured, in stark difference to the academic learning context, which offers a high degree of flexibility that many student veterans find challenging. Veterans thus commonly describe a loss of structure when entering higher education (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019). The military learning context often relies on a binary standard of right and wrong action, and military institutions instruct learners to accept this standard in an uncritical manner. In contrast, academia typically invites students to discuss competing paradigms or make ethical considerations, where answers are relative to the context in which they are applied (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011b).

A third field of difference reported in student veteran studies is the differences in social roles. While social roles and daily agendas are highly defined in the military (Hodges et al., Citation2022), academia requires students to adapt fluid roles and agendas (Naphan & Elliot, Citation2015). This challenges veterans to adapt social roles different from the military, prompting them to shift from conforming behaviour to independent expression, from collective to individualist thinking, from rigid rule-following behaviour to adaptive practice, and from clear instruction to becoming reflective in the face of a plurality of truths (Falkey, Citation2016; Ryan et al., Citation2011). Even though these shifts are more extensive for veterans than for average students, they also invite student veterans to engage in higher-order thinking, identity development, and individuation.

Mental health challenges in class and on campus

Student veterans also differ from non-veteran students through their high prevalence of cognitive and mental health diagnoses. Symptoms of TBI, PTSD, Military Sexual Trauma, and depression elicit flashbacks and angry reactions that disable learning and social interaction in class (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019; Messerschmitt-Coen, Citation2021).

Large lecture halls are perceived as particularly stressful by student veterans (Mahoney et al., Citation2023). Hypervigilance causes student veterans to monitor their surroundings (e.g. physical circumstances of the classroom), analyse potential threats, and be prepared to fight or flee (Kato et al., Citation2016). Large, crowded lecture halls are exceedingly difficult to monitor and require student veterans to sit with their backs towards people and doors. Some studies also report that specific sounds or images may trigger flashbacks and hyperarousal (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019; Roost, Citation2015).

Flashbacks are memories that intrude on student veterans’ current experiences. Flashbacks may be triggered by a wide range of events, e.g. a flock of birds outside the classroom window may trigger memories of shrapnel from an explosion, or red and pink colours in a PowerPoint slide may trigger memories of bleeding bodies (Mahoney et al., Citation2023; Roost, Citation2015). Such flashbacks impair attention in class. In line with these findings, other studies indicate that PTSD symptoms decrease student veterans’ self-efficacy for learning (Reyes et al., Citation2018) and increase the risk of dropout (Morgan et al., Citation2023). A Canadian study highlights that student veterans with no prior tertiary education are at particular risk of suffering from mental health challenges (Ogrodniczuk et al., Citation2021).

Angry reactions to stressors in class are another issue for some student veterans and may strain social relations with their peers. In extension of this issue, some studies highlight that strained relations are a leading cause of suicide (Lokken et al., Citation2009). Statistically, 47% of veterans frequently show angry reactions, 7.7% of student veterans in the US attempt suicide (as compared to 1.8% of non-veterans), and 20 veterans die by suicide every day (Hinkson et al., Citation2021; Messerschmitt-Coen, Citation2021; Wisner et al., Citation2015). Outside of the US, similar findings exist, and a Canadian study shows 6% of student veterans attempted suicide in the past year (Ogrodniczuk et al., Citation2021). Comparing veteran and non-veteran students, research indicates that student veterans were 33% more likely to suffer from depression, and 26% more likely to suffer from PTSD (Fortney et al., Citation2016). Here, PTSD more often led to symptoms of anxiety, depression, and suicidality in student veterans than non-veterans (Hetelekides et al., Citation2023). From a qualitative perspective, veteran with PTSD seem to experience more difficulties maintaining peer relationships and social isolation (Barmak et al., Citation2021), as well as a lack of peer support (Reyes et al., Citation2018; Young & Phillips, Citation2019). Overall, the relationship between mental health and social interaction is essential to understanding student veterans’ experiences.

Social interaction with non-veteran students and faculty

Numerous studies examine the reintegration of student veterans based on their social interactions. These studies commonly highlight that veterans, non-veteran students, and faculty base their actions on significantly divergent worldviews, which leads to conflicts or misunderstandings in classroom interactions (DiRamio et al., Citation2008; Lim et al., Citation2018). How student veterans can communicate their worldviews impacts the extent to which they can draw on military values and skills in interaction (Bagby et al., Citation2015). Similarly, worldview- and value-related conflicts can cause student veterans to feel alienated or socially isolated (Samson, Citation2017).

Student veterans often act in a highly disciplined manner, influenced by experiences of combat and humanitarian crises in foreign countries (Cable, Cathcart, et al., Citation2021), and linked to a value of duty. Student veterans commonly juxtapose their experiences in foreign countries with their experience as students (Hart & Thompson, Citation2016), and continue to act in disciplined, dutiful ways, which reflects in efforts to meet submission and exam deadlines and in the way in which they engage in interaction. In the academic context, veterans exhibit a work ethic that values discipline, teamwork, and leadership skills, all of which are found beneficial for peer collaboration and academic success (Harvey et al., Citation2018; Hinkson et al., Citation2021). At the same time, student veterans experience non-veteran students to be more likely to complain, to participate in classes in an unengaged manner (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019; Killam & Degges-White, Citation2018), and to be unrespectful towards teacher authority and the educational environment (Kato et al., Citation2016). Student veterans seem to be particularly disconnected from younger students (Gregg, Howell, et al., Citation2016a).

Irritations related to divergent worldviews are rarely voiced by student veterans. From a veteran perspective, such self-silencing signals respect for authorities (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019). Studies also report that student veterans avoid exposing differences in communication, as their military style of communicating may be misinterpreted as offensive, in contrast to a civilian communication style which veterans experience as politically correct and difficult to navigate (Roost, Citation2015). However, self-silencing disables reintegration, as no self-advocacy or inquiry takes place to explore the underlying issues (Howe & Shpeer, Citation2019). Consequently, some veterans complete their entire education without building social relations (Gregg et al., Citation2018), an undesirable outcome that is also incongruent with the military-learned values of group belonging and collectivism (Mahoney et al., Citation2023).

Different role expectations between faculty members and student veterans are also reported as a cause of misunderstanding (Lim et al., Citation2018). In accordance with their different cultures, faculty expect veterans to devise their own plans for academic tasks, and to ask for guidance when necessary. At the same time, veterans expect faculty to deliver detailed instructions that minimise ambiguity and eradicate the need for follow-up questions (Blaauw-Hara, Citation2016). This leads to a situation where student veterans perceive teachers to be incompetent leaders, and where faculty perceives student veterans as incompetent – equally unfavourable perceptions that impair their relationship and their social interaction, often to the disadvantage of veterans (Lim et al., Citation2018).

Support efforts for student veterans

Many reviewed articles provide suggestions about how to support the well-being of student veterans. Within these articles, we identified four common themes, illustrated in the following sections: (1) Becoming a veteran-friendly campus, (2) academic support, (3) mental health support, and (4) social support. Overall, the literature indicates that support efforts have a widely positive influence on veteran well-being and that social support is a protective factor for mental health challenges. The outlined support efforts in the literature also illustrate that student veterans are highly diverse in their needs, which makes it difficult to maintain a one-size-fits-all approach to veteran support. Veteran support professionals often have to tailor support efforts, so they fit the different contexts in which veterans live and study, and good practice often relies on their case-specific, professional judgement.

Becoming a veteran-friendly campus

An initial step towards support is for veterans to identify supportive campuses to enrol in. The veteran-friendly campus is a prominent category used to identify institutions with dedicated veteran support and sensitivity towards military culture (Ackerman et al., Citation2009; Lokken et al., Citation2009). Still, the category of a veteran-friendly campus has its limitations, as there is no monitored, uniform standard to what veteran-friendliness means (Falkey, Citation2016). Irrespective of these limitations, it remains imperative to identify and connect with enrolled veterans to create veteran-friendly campuses (Kato et al., Citation2016), and many institutions achieve this through questionnaires that are sent out to student veterans, particularly to ask about how they use veteran benefits (Hodges et al., Citation2022). However, some student veterans overlook such benefits, and others hide their veteran status to blend in (Alschuler & Yarab, Citation2016), which limits insights into their situation (Vacchi, Citation2012).

Academic support

The second major theme in veteran support focuses on academic support efforts. Here, a larger number of US studies highlight the role of Veteran Resource Centres on campus. These centres are designated spaces for veterans that offer various services related to navigating bureaucratic administrations, often staffed with specifically trained personnel (Barmak et al., Citation2021). Studies also highlight that veterans are challenged by navigating higher education bureaucracies and external funding schemes, which may delay funding and render veterans unable to pay for tuition, books, and housing (Hunter-Johnson et al., Citation2020). Moreover, some student veterans may be recalled into military service, which tasks them to withdraw from education, deploy to an international mission, and re-enrol upon return (Hodges et al., Citation2022). Veteran Resource Centres also offer services to develop academic skills, including specialised writing workshops (Canto et al., Citation2015; Hart & Thompson, Citation2016) and tutoring sessions (Ott, Citation2020). Studies indicate that such services should consider veteran backgrounds when designing course materials and activities, to scaffold academic development around veterans’ strengths (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011c; Hart & Thompson, Citation2016).

Mental health support

Mental health support, often through specialised programmes and outreach efforts, is a third common theme within veteran support efforts. Support programmes are often campus-integrated and offer vulnerable veterans access to specialised counselling and treatment (Barragan et al., Citation2021). However, studies also indicate that these services are not utilised much by veterans (Gregg et al., Citation2016b; Gordon et al., Citation2016). Exploring the issue, studies from the US and Canada highlight that veterans have a tendency to hide their disability from faculty and peers, described as help-seeking stigma (Lewis & Wu, Citation2019; Ogrodniczuk et al., Citation2021). Help-seeking stigma makes student veterans avoid seeking treatment, commonly due to concerns of being branded as weak or broken (Kato et al., Citation2016). Such concerns originate in a military culture that values self-reliance (Dobson et al., Citation2019), makes veterans avoid burdening their group (K. C. Jones, Citation2016), and frames help-seeking as a weakness that potentially undermines military masculinity (Alschuler & Yarab, Citation2016). Help-seeking is also a potential threat for veterans who want to continue their military careers after their studies, as mental health conditions such as depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation disqualify for enlistment in the US (Messerschmitt-Coen, Citation2021). This renders seeking help and maintaining a military career incompatible. At the same time, help-seeking may be supported through outreach efforts and proactive counselling (Barragan et al., Citation2021) that portrays help-seeking as a strength, and confronts self-reliance norms (Harris et al., Citation2022).

Social support

Social support efforts commonly focus on how student veterans can build social relations with veteran peers, faculty, and self-expression.

Building relations with veteran peers can be enabled through veteran lounges that provide a space for peer support and belonging (Falkey, Citation2016). Veteran lounges can also help in addressing veterans’ desire for a safe space (Jenner, Citation2019). In contrast, some articles warn that veteran lounges promote self-segregation (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011b). The safe-space quality of lounges may reinforce peers as veterans’ primary social group, disable their socialisation with non-veteran peers, and reduce exposure to other intellectual spaces (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011d). Combining both perspectives, veteran lounges may serve as incubators for initial campus relations but may lose relevance as veterans continue to build relations with non-veteran peers.

Building relations with faculty is often enabled through specific programmes, such as the Green Zone training programme. This programme increases the visibility of veteran-friendly faculty and administrative staff through office door stickers and guides veterans towards knowledgeable support (Dillard & Yu, Citation2018). Within the programme, veteran-friendly indicates that faculty and staff have either military experience or veteran-related training (Nichols-Casebolt, Citation2012). However, some studies are critical towards using military-experienced faculty as mediators between cultures as such approaches may have a segregating effect (Arminio et al., Citation2018).

Self-expression of student veterans is supported through programmes that focus on self-authorship or artistic expression, which engages veterans in meaning-making processes that can ultimately bridge dissonant military and civilian worldviews. As meaning-making mediates dissonances, these programmes contribute to reintegration and overcoming trauma (Mahoney et al., Citation2023). Here, dissonances are experiences that put current ways of meaning-making into question (DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011b). In the context of military service, dissonances often result from experiences of traumatic or immoral events in military service that disrupt other meaning perspectives (Baechtold & De Sawal, Citation2009; Mahoney et al., Citation2023). Through self-authorship and artistic expression, veterans share how military experiences have shaped their worldviews (Gregg et al., Citation2018) and develop self-advocacy skills necessary to convey their worldview through storytelling (Belanger et al., Citation2021). The programmes also engage veterans and non-veterans in interpreting and negotiating experiences that underpin their different worldviews. Such negotiations include constructive, mutual critiques that stimulate veterans’ reflections on how war experiences and military culture shape their worldviews. Ultimately, these negotiations can lead to more nuanced worldviews and an increased awareness of how veterans want to relate to their non-veteran peers on campus (Canto et al., Citation2015; DiRamio & Jarvis, Citation2011b).

Discussion

Across the reviewed literature, we found that research on student veterans is often related to some definition of academic success. Academic success is a topic in 38% of reviewed articles (n = 53). Most of these articles do not feature an explicit concept of academic success (n = 41), but articles that do define the term rely on a metrics-centric definition (n = 12). At the same time, only two articles provide a definition of academic success that does not exclusively rely on metrics. Metrics-centric definitions can thus be understood as widely prevalent, at least in the US literature, and their measurements focus on academic achievements, competence levels, tests, and grade point averages (Barragan et al., Citation2021; Hinkson et al., Citation2021). In non-US literature on student veterans, academic success remains widely undefined. Therefore, we find it particularly relevant for non-US researchers to consider what the term entails, emphasising that metrics-oriented definitions and their focus on competence levels are found inadequate to represent student veterans’ perceptions of success (Blaauw-Hara, Citation2016; Zoli et al., Citation2017). In line with these critical evaluations, prominent European educational researchers highlight the relevance of going beyond metrics-centric approaches, arguing that metrics create an instrumental view on education that replaces the educational aim of ‘learning to be’ in the world and with others, with ‘learning to be productive and employable’ (Biesta, Citation2022, p. 660). Arguing for an alternative, these researchers emphasise that education needs to be non-instrumental, as its aim lies in self-reflexive activities in which learners ‘develop a morally reflected will directing a responsible way of living together [with] others’ (Uljens, Citation2023, p. 4). Thinking of education as an encouragement to self-reflexive activities, then, summons learners – in our case, veterans – to become the subject of their own life, denying them the comfort of not being a subject, and entering a state of relative autonomy that is necessary for existing ‘in and with the world’ (Biesta, Citation2020, p. 95).

Empirical findings from student veteran research indicate that veterans experience this encouragement to become self-reflexive very differently from non-veteran students, and indeed may have a very different way of existing in and with the world: Based on our review, we suggest thinking about student veterans as a group that shares a set of moral beliefs that distinguishes itself from that of non-student veterans. This set of moral beliefs constitutes a disposition about what living together with others entails, which is instilled by military culture and consolidated through war experiences. Furthermore, this disposition affects how student veterans develop moral reflections when education prompts them to do so. We argue that it is the distinct moral disposition of veterans that makes them experience non-veteran students as people who ‘haven’t seen the world’ and to ‘hold very immature view points’ (Harvey et al., Citation2018, p. 26). Similarly, student veterans’ perception of non-veteran peers as naive, entitled, and ‘out of touch with the world’ (Cassidy & Albanesi, Citation2023; Ness et al., Citation2014; Osborne, Citation2013) can be explained through their existential perspective, which makes them see non-veterans as individuals who have ‘a disregard for what is real’ (Biesta, Citation2020, p. 97). This existential reality that veterans have been instilled into also makes them perceive that their ‘daily lives held importance and gratification’ during deployment and that their ‘civilian jobs do not matter’ (Kato et al., Citation2016, p. 2140).

Limitations

This review has several limitations that should be noted.

Language and literature scope. As an initial delimitation of our scope, we did not include non-English, grey literature. This can lead to publication bias. We are aware that non-English literature exists, possibly as grey literature, and that research in other languages may offer different perspectives and findings. Future reviews could benefit from considering such literature, particularly from the NATO countries not mentioned here, that have recently been involved in wars.

Geographical limitations. Despite our intention to identify and include non-US studies, our review strongly relies on US research. Due to the scarcity of non-US research, researchers should reflect on the national context of US research, and similarities or differences to the cultural, economic, and political situation of veterans. To give one example, we see a significant difference in the economic situation of veterans, which is marked by the Post-9/11 GI Bill in the US, whereas the Danish situation is marked by the European welfare state model that provides free access to higher education.

Comparing student veterans and other non-traditional students: While a comprehensive comparison of student veterans with other non-traditional students is beyond the scope of a review article, we would like to share some initial remarks: Like student veterans, non-traditional students, and in particular older, male students, often experience social integration challenges, disconnection, and stereotyping (Carreira & Lopes, Citation2021; Hunter-Johnson, Citation2022). Further research may illustrate whether veteran status has a secondary function in these experiences or not. Like non-traditional students, student veterans can be seen to participate in a globalised and increasingly homogenous education, even though national differences in navigating the educational system for them continue to exist (Field, Citation2018). Because of the various national contexts in which research takes place, comparative analysis holds a certain degree of complexity, which cannot be sufficiently addressed within the scope of this literature review. At the same time, student veterans are unlike other non-traditional in that they are much more likely to suffer from PTSD (Fortney et al., Citation2016). Focussing on students diagnosed with PTSD, student veterans also differ from other non-traditional students in that they more frequently suffer from anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Hetelekides et al., Citation2023). Ultimately, we want to emphasise that comparing student veterans and other non-traditional students requires attention to divergent definitions of non-traditional students, adult learners, lifelong learners, and non-traditional adult learners (Brücknerová et al., Citation2020; Shelton, Citation2021), which should be considered in further research.

Conclusion

This review identified three primary conceptual frameworks in student veteran research: transition, mental health, and reintegration frameworks. Key themes in the literature include differences in military and academic learning, mental health challenges, and social interaction issues with non-veteran students and faculty. Based on these themes, support efforts for veterans focus on creating veteran-friendly campuses, academic support, mental health support, and social support.

Several research gaps were identified. Most importantly, statistics about student veterans exist only on a local level and attempts to represent the situation of student veterans on a larger scale remain inconclusive. This leaves researchers in the dark concerning the scale and severity of student veteran challenges. Furthermore, and despite our emphasis on non-US contexts, only 8 of 137 articles focused on non-US contexts, including research from Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ukraine, and the UK. This is remarkable, considering that more than 43 NATO countries and partners have engaged in war zones since 2001.

Finally, we highlighted that much research on student veterans relies on metrics-centric approaches that entail an instrumental view of education and a narrow definition of academic success. Metrics-centric definitions of academic success focus on academic achievement, testing, and grade point averages, and thus provide a narrow perspective on education, while disregarding the purpose of education to provide socialisation and to develop autonomy. Understanding education as a process that focuses on the acquisition of qualifications, but equally on learning to be in society – recognising the values of civilian society and participating with relative autonomy in its social fields – will provide a more nuanced comprehension of adjustment and acculturation challenges and related support services. Ultimately, such an understanding of education may help to explain why some support services are under-utilised and indicate how to address prevalent challenges of veterans in their transition into education.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank our project advisory board members Arnd-Michael Nohl, Linda Maguire, and Thomas Randrup Pedersen. Your feedback and reflections contributed significantly to this paper, and we would like to express our warmhearted gratitude for collaborating with us on our project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerman, R., DiRamio, D., & Mitchell, R. L. G. (2009). Transitions: Combat veterans as college students. New Directions for Student Services, 2009(126), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.311

- Alschuler, M., & Yarab, J. (2016). Preventing student veteran attrition: What more can we do? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 20(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025116646382

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arminio, J., Yamanaka, A., Hubbard, C., Athanasiou, J., Ford, M., & Bradshaw, R. (2018). Educators acculturating to serve student veterans and service members. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(3), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2018.1399895

- Baechtold, M., & De Sawal, D. M. (2009). Meeting the needs of women veterans. New Directions for Student Services, 2009(126), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.314

- Bagby, J. H., Barnard-Brak, L., Thompson, L. W., & Sulak, T. N. (2015). Is anyone listening? An ecological systems perspective on veterans transitioning from the military to academia. Military Behavioral Health, 3(4), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2015.1057306

- Barmak, S. A., Barmaksezian, N., & Der-Martirosian, C. (2021). Student veterans in higher education: The critical role of veterans resource centers. Journal of American College Health, 71(8), 2406–2416. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1970562

- Barragan, C., Ryckman, L., & Doyle, W. (2021). Improving educational outcomes for first-year and first-generation veteran students: An exploratory study of a persistent outreach approach in a veteran-student support program. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 70(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2021.1908773

- Barry, A. E., Jackson, Z. A., & Fullerton, A. B. (2021). An assessment of sense of belonging in higher education among student service members/veterans. Journal of American College Health, 69(3), 335–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1676249

- Barry, A. E., Whiteman, S. D., & Wadsworth, S. M. (2014). Student service members/veterans in higher education: A systematic review. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 51(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2014-0003

- Beck, K. E. (2020). From GI joe to college joe: Bridging the gap between military and college life. Stonybrook University. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1341815.pdf

- Belanger, B., Steele, A., & Philhower, K. (2021). Tailoring higher education options for smaller institutions to meet veterans’ needs: Enhancing inclusion in higher education: Practical solutions by veterans for veterans. Journal of Veterans Studies, 7(1), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.v7i1.229

- Bell, B. (2017). In and out: Veterans in transition and higher education. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 5(3), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/sem3.20111

- Benbow, R. J., & Lee, Y.-G. (2022). Exploring student service member/veteran social support and campus belonging in university STEMM fields. Journal of College Student Development, 63(6), 593–610. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2022.0050

- Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

- Bichrest, M. M. (2013). A formal literature review of veteran acculturation in higher education. Rivier Academic Journal, 9(2), 1–12. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/a-formal-literature-review-of-veteran-acculturation-bichrest/95b4844269a8c2298e405190ff11db96afabe1f9

- Biesta, G. (2020). Risking ourselves in education: Qualification, socialization, and subjectification revisited. Educational Theory, 70(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12411

- Biesta, G. (2022). World-centred education: A view for the present. Routledge.

- Blaauw-Hara, M. (2016). “The military taught me how to study, how to work hard”: Helping student-veterans transition by building on their strengths. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(10), 809–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2015.1123202

- Borsari, B., Yurasek, A., Miller, M. B., Murphy, J. G., McDevitt-Murphy, M. E., Martens, M. P., Darcy, M. G., & Carey, K. B. (2017). Student service members/veterans on campus: Challenges for reintegration. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000199

- Brücknerová, K., Rozvadská, K., Knotová, D., Juhaňák, L., Rabušicová, M., & Novotný, P. (2020). Educational trajectories of non-traditional students: Stories behind numbers. Studia Paedagogica, 25(4), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2020-4-5

- Cable, G., Cathcart, D. G., & Almond, M. K. (2021). The case for veteran-friendly higher education in Canada and the United Kingdom. Journal of Veterans Studies, 7(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.v7i1.225

- Cable, G., Fleuty, K., & Almond, M. (2021). Snapshot: Education and training. Forces in Mind Trust Research Centre. http://www.fimt-rc.org/article/20210517-snapshot-education-and-training

- Canto, A. I., McMackin, M. L., Hayden, S. C. W., Jeffery, K. A., & Osborn, D. S. (2015). Military veterans: Creative counseling with student veterans. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 28(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2015.1011473

- Carreira, P., & Lopes, A. S. (2021). Drivers of academic pathways in higher education: Traditional vs. non-traditional students. Studies in Higher Education, 46(7), 1340–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1675621

- Cassidy, S. P., & Albanesi, H. (2023). “You haven’t gone out and done anything”: Exploring disabled veterans experiences in higher education. Armed Forces & Society, 49(2), 507–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X211063920

- Castro, C. A., Dursun, S., Duel, J., Elands, M., Fossey, M., Harrison, K., Mr Heinzt, O. A., Lazier, R., Lewis, N., MacLean, M.-B., & Truusa, T.-T. (2021). NATO technical report STO-TR-HFM-263: The transition of military veterans from active service to civilian life. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Science and Technology Organization. https://www.sto.nato.int/publications/STO%20Technical%20Reports/STO-TR-HFM-263/$TR-HFM-263-ES.pdf

- Cate, C. A., Lyon, J. S., Schmeling, J., & Bogue, B. Y. (2017). National veteran education success tracker: A report on the academic success of student veterans using the Post-9/11 GI Bill. Student Veterans of America. https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/veteran-success-tracker.pdf

- Dillard, R. J., & Yu, H. H. (2018). Best practices in student veteran education: Faculty professional development and student veteran success. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 66(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2018.1469072

- DiRamio, D., Ackerman, R., & Mitchell, R. L. (2008). From combat to campus: Voices of student-veterans. NASPA Journal, 45(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1908

- DiRamio, D., & Jarvis, K. (2011a). Crisis of identity? Veteran, civilian, student. ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3703

- DiRamio, D., & Jarvis, K. (2011b). Home alone? Applying theories of transition to support student veterans’ success. ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3703

- DiRamio, D., & Jarvis, K. (2011c). Ideas for a self-authorship curriculum for students with military experience. ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3703

- DiRamio, D., & Jarvis, K. (2011d). Transition 2.0: Using Tinto’s model to understand student veterans’ persistence. ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3703

- Dobson, C. G., Joyner, J., Latham, A., Leake, V., & Stoffel, V. C. (2019). Participating in change: Engaging student veteran stakeholders in advocacy efforts in clinical higher education. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167819835989

- Elliott, M., Gonzalez, C., & Larsen, B. (2011). U.S. military veterans transition to college: Combat, PTSD, and alienation on campus. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 48(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.6293

- Elnitsky, C. A., Blevins, C., Findlow, J. W., Alverio, T., & Wiese, D. (2018). Student veterans reintegrating from the military to the university with traumatic injuries: How does service use relate to health status? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(2S), S58–S64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.10.008

- Falkey, M. E. (2016). An emerging population: Student veterans in higher education in the 21st century. Journal of Academic Administration in Higher Education, 12(1), 27–39. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1139143

- Field, J. (2018). Comparative issues and perspectives in adult education and training. In B. Bartram (Ed.), International and comparative education: Contemporary issues and debates (1st ed., pp. 100–112). Routledge.

- Fortney, J. C., Curran, G. M., Hunt, J. B., Cheney, A. M., Lu, L., Valenstein, M., & Eisenberg, D. (2016). Prevalence of probable mental disorders and help-seeking behaviors among veterans and non-veteran community college students. General Hospital Psychiatry, 38, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.09.007

- Ghosh, A., Santana, M. C., & Opelt, B. (2020). Veterans’ reintegration into higher education: A scoping review and recommendations. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 57(4), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2019.1662796

- Gordon, H. R. D., Schneiter, H., Bryant, R., Winn, V., Buke, V. C., & Johnson, T. (2016). Staff members’ perceptions of student-veterans’ transition at a public two-year and four-year institution. Educational Research: Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–14. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1252603

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Gregg, B. T., Howell, D. M., & Shordike, A. (2016a). Experiences of veterans transitioning to postsecondary education. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.021030

- Gregg, B. T., Kitzman, P. H., & Shordike, A. (2016b). Well-being and coping of student veterans readjusting into academia: A pilot survey. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 32(1), 86–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1082081

- Gregg, B. T., Shordike, A., Howell, D. M., Kitzman, P. H., & Iwama, M. K. (2018). Student veteran occupational transitions in postsecondary education: A grounded theory. Military Behavioral Health, 6(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2017.1333063

- Harris, M. P. J., Palmedo, P. C., & Fleary, S. A. (2022). “What gets people in the door”: An integrative model of student veteran mental health service use and opportunities for communication. Journal of American College Health, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2129977

- Hart, D. A., & Thompson, R. (2016). Veterans in the writing classroom: Three programmatic approaches to facilitate the transition from the military to higher education. College Composition and Communication, 68(2), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc201628884

- Harvey, L., Andrewartha, A., Sharp, M., & Wyatt-Smith, M. (2018). Supporting younger military veterans to succeed in Australian higher education. Centre for Higher Education Equity and Diversity Research, La Trobe University. 4(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.v4i1.82

- Hassan, A. M., Jackson, R., Lindsay, D. R., McCabe, D. G., & Sanders, J. E. (2010). The veteran student in 2010: How do you see me? ACPA - College Student Educators International, 15(2), 30–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.20020

- Heitzman, A. C., & Somers, P. (2015). The disappeared ones: Female student veterans at a four-year college. College and University, 90(4), 16–26. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1083721

- Hetelekides, E., Bravo, A. J., Burgin, E., & Kelley, M. L. (2023). PTSD, rumination, and psychological health: Examination of multi-group models among military veterans and college students. Current Psychology, 42(16), 13802–13811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02609-3

- Hinkson, K. D., Jr., Drake-Brooks, M. M., Christensen, K. L., Chatterley, M. D., Robinson, A. K., Crowell, S. E., Williams, P. G., & Bryan, C. J. (2021). An examination of the mental health and academic performance of student veterans. Journal of American College Health, 70(8), 2334–2341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1858837

- Hodges, T. J., Gomes, K. D., Foral, G. C., Collette, T. L., & Moore, B. A. (2022). Unlocking SSM/V success: Welcoming student service members and veterans and supporting SSM/V experiences. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/15210251221086851

- Howe, W. T., Jr., & Shpeer, M. (2019). From military member to student: An examination of the communicative challenges of veterans to perform communication accommodation in the university. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 48(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2019.1592770

- Hunter-Johnson, Y. (2022). A leap of academic faith and resilience: Nontraditional international students pursuing higher education in the United States. Journal of International Students, 12(2), 2166–3750. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v12i2.1986

- Hunter-Johnson, Y., Liu, T., Murray, K., Niu, Y., & Suprise, M. (2020). Higher education as a tool for veterans in transition: Battling the challenges. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 69(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2020.1743621

- Jenner, B. M. (2019). Student veterans in transition: The impact of peer community. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition, 31(1), 69–83. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1211881

- Jones, K. (2013). Understanding student veterans in transition. The Qualitative Report, 18(37), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1468

- Jones, K. C. (2016). Understanding transition experiences of combat veterans attending community college. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 41(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2016.1163298

- Kato, L., Jinkerson, J. D., Holland, S. C., & Soper, H. V. (2016). From combat zones to the classroom: Transitional adjustment in OEF/OIF student veterans. The Qualitative Report, 21(11), 2131–2147. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2420

- Killam, W. K., & Degges-White, S. (2018). Understanding the education-related needs of contemporary male veterans. Adultspan Journal, 17(2), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsp.12062

- Lewis, M. W., & Wu, L. (2019). Depression and disability among combat veterans’ transition to an historically black university. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671258

- Lim, J. H., Interiano, C. G., Nowell, C. E., Tkacik, P. T., & Dahlberg, J. L. (2018). Invisible cultural barriers: Contrasting perspectives on student veterans’ transition. Journal of College Student Development, 59(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0028

- Lokken, J. M., Pfeffer, D. S., McAuley, J., & Strong, C. (2009). A statewide approach to creating veteran‐friendly campuses. New Directions for Student Services, 2009(126), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.315

- Mahoney, M. A., Rings, J. A., Softas-Nall, B. C., Alverio, T., & Hall, D. M. (2023). Homecoming and college transition narratives of student military veterans. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 37(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2021.1926034

- Matthews-Smith, G., Mackay, D., Sholl, S., & Thomas, L. J. (2021). You’re in your own time now: Understanding current experiences of transition to civilian life in Scotland. Interim report. Edinburgh Napier University. https://www.napier.ac.uk/~/media/youre-in-your-own-time-now–interim-report.pdf

- Messerschmitt-Coen, S. (2021). Considerations for counseling student veterans. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 35(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2019.1660292

- Moeck, E. K., Takarangi, M. K. T., & Wadham, B. (2022). Assessing student veterans’ academic outcomes and wellbeing: A scoping review. Journal of Veterans Studies, 8(3), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.21061/jvs.v8i3.327

- Moore, E., Williams, K., & Jaynes, Z. (2020). Status of veterans in the United Kingdom. In E. Moore, K. Williams, & Z. Jaynes (Eds.), United Kingdom veteran landscape (pp. 7–11). Center for a New American Security. Washington. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26042.5

- Morgan, N. R., Aronson, K. R., McCarthy, K. J., Balotti, B. A., & Perkins, D. F. (2023). Post-9/11 veterans’ pursuit and completion of post-secondary education: Social connection, mental health, and finances. Journal of Education, 204(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574231168638