Abstract

Dressing formally or informally as an academic may be a trade-off when it comes to managing impressions towards students, but the extant body of literature remains limited with only mixed results. This research is the first focussed investigation to examine the effects of academic dress formality on the ‘big two’ of impression formation, perceptions of warmth and competence. In a series of three controlled laboratory experiments (total N = 1361), we find dress formality to increase perceptions of competence but to decrease perceptions of warmth, which leads to ‘downstream’ effects on students’ evaluations of instructors and behavioural intentions to enrol in a course. Furthermore, we demonstrate that perceptions of competence may be subject to other information cues (success communication and discipline norms) that can mitigate negative effects associated with dress informality. Implications for higher education practitioners are provided.

Introduction

As academics, we have all experienced the great heterogeneity of dressing on campus or at a conference. Indeed, some academics may dress very formally in suits, while others prefer informal clothing, such as T-shirts, jeans and running shoes. Clothing plays a critical role in guiding impressions towards others (Goffman Citation1959; Johnson, Lennon, and Rudd Citation2014), and while employees in the corporate world ‘dress to impress’ clients and other important stakeholders (Cardon and Okoro Citation2009), academia seems to be largely void of such a strict, prescribed dress code. Yet, dressing formally or informally may still give off certain impressions to students, and importantly, affect students’ evaluations of instructors and student behaviour (Uttl, White, and Gonzalez Citation2017). Some of us may want to intentionally signal our assertiveness and competence when dressing in suits, seeking to command students’ respect and behaviour in the classroom. Others may, unintentionally but still equally effectively, convey approachability and friendliness when dressing informally, which may improve professor–student relationships and increase students’ willingness to engage. Given both formal and informal clothing seem to come with benefits and drawbacks, should academics in higher education stick to one or the other?

A small number of studies (Morris et al. Citation1996; Lightstone, Francis, and Kocum Citation2011) have specifically investigated the association between dress formality and perceptions of competence in academia. While results are mixed, professors are often advised to dress formally to raise impressions of authority, competence and professionalism in students (Morris et al. Citation1996; Gorham, Cohen, and Morris Citation1999). However, academics are largely perceived as intellectual leaders who hold the highest educational accolades (Macfarlane Citation2011), and, as such, can be considered high-status individuals. High-status individuals, in turn, project competence regardless (Fiske Citation2018), while warmth and similar traits, such as approachability and friendliness, may be less likely perceived.

Social cognition research has established the ‘big two’, competence and warmth, as critical traits that people use to assess others (Brambilla et al. Citation2010; Holoien and Fiske Citation2013; Kervyn et al. Citation2016; Fiske Citation2018). In general, formality is associated with competence, informality with warmth. Using informal language in emails, such as emoticons (e.g. Marder et al. Citation2019; Li, Chan, and Kim Citation2019), helps the sender appear warmer but makes them also seem less competent, with consequences for receivers’ evaluations, preferences and intentions. To the authors’ best knowledge, current research on the effect of academic dress formality is void of an explicit investigation of the ‘big two’. Prior research has also left unattended the ‘downstream’ effects of such impression formation, and it remains unclear whether dressing formally or informally has positive effects on students’ evaluations of instructors and behaviour.

To close this gap, the goal of this research is to offer the first focussed examination of the ‘big two’ impression formation variables, warmth and competence (Fiske Citation2018), in the context of academic dress. We address the following research questions in three controlled laboratory experiments: firstly, how does academic dress formality affect perceptions of warmth and competence? Secondly, how do perceptions of warmth and competence affect students’ evaluations and behaviour? Thirdly, how do other factors, such as communicated success of the instructor and discipline norm, affect the impact of dress formality on impressions, mitigating potentially negative effects and offering a potential resolution to a trade-off between dressing formally versus informally?

The contribution of this research is threefold. Firstly, by investigating not only the formality–competence link but also the association between dress formality and warmth, the results help disentangle extant mixed findings. Secondly, since we examine downstream consequences of such perceptions, we demonstrate the interplay of perceptions of warmth and competence in affecting students’ evaluations of instructors and behavioural intentions. These variables go beyond measures such as ‘liking’, and complete the picture of dress formality effects specifically for academia, where students’ evaluations have become a critical component of university rankings, faculty promotions and tenure decisions (Bolton and Nie Citation2010; Shin and Toutkoushian Citation2011; Eisenberg, Härtel, and Stahl Citation2013; Brown et al. Citation2015). Thirdly, this research presents a timely and necessary continuation of a topic that has been left unexamined for nearly a decade. Given the shift in higher education towards fostering closer relationships between staff and students, it may become particularly important for academics to consider impression management strategies to increase their perceived warmth (Elmore and LaPointe Citation1975; Pan et al. Citation2009; Cortina, Arel, and Smith-Darden Citation2017).

Conceptual background

Impression management & the big two

The conscious effort of creating, maintaining or altering perceptions of oneself in the eyes of others is known as impression management (Goffman Citation1959; Gardner and Martinko Citation1988). Actors strategically manipulate both verbal and non-verbal behaviours as a means towards accomplishing their self-presentation goals (Bozeman and Kacmar Citation1997). Such goals may be of social or economic nature and may include mutuality, need for power, identity-validation and social approval (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995). Impression management research has been conducted throughout a wide array of psychosocial and organisational contexts, including leader–subordinate relationships (Wayne and Ferris Citation1990; Wayne and Liden Citation1995) student perceptions of staff within higher education (Widmeyer and Loy Citation1988; Veletsianos Citation2012; Marder et al. Citation2019), psychology and consulting (Friedlander and Schwartz Citation1985) and interviewing (Baron Citation1986; Forsythe Citation1990; Knouse Citation1994).

While much of the extant research on impression management focuses on potential beneficial effects of desirable self-presentation within given contexts, this inherently carries certain risks. Should viewers align their self-presentation with sycophantic or manipulative behaviour, it is likely that corresponding perceptions from sender to receiver will be negative (Baron Citation1986; Turnley and Bolino Citation2001). Similarly, self-presentation tactics naturally hold the possibility of misperception. For example, while over-exaggerating one’s characteristics to express confidence is not uncommon in interviews or workplaces (e.g. Paulhus et al. Citation2013), listeners can easily misinterpret these cues as arrogant or conceited behaviour. Those practicing impression management techniques should take into account not only what impressions they may be conveying, but also consequential perceptions formed by receivers.

Deemed as the ‘big two’, the traits of perceived warmth and competence are known as critical facets of impressions and initiators of subsequent behaviour (Abele and Bruckmüller Citation2011; Holoien and Fiske Citation2013; Kervyn et al. Citation2016; Fiske Citation2018). Prior research has established emergent stereotypes in which one’s perceived warmth or competence is often based on socio-economic status, background and age (Cuddy et al. 2009; Fiske Citation2018). Certain groups (e.g. low paid workers, elderly) are often stereotyped as less competent but warm. High-status groups (e.g. the rich, professionals, businesspeople) are often regarded as more competent yet cold (Russell and Fiske Citation2008; Fiske Citation2018). As a result, individuals may manage impressions to countervail these perceptions. As a means of strengthening social likeness and trust, high-status individuals may strive to be perceived as warmer (as opposed to more competent) in the presence of lower-status audiences to reduce power distance, while the opposite holds true for lower-status individuals (Holoien and Fiske Citation2013).

Within a professional context, people are considered to be more competent when they dress smartly (Dacy and Brodsky Citation1992). Even small changes in attire are found to make a difference; Howlett et al. (Citation2013) showed wearing a made-to-measure suit opposed to one bought ‘off the peg’ signalled greater success and confidence. Suits have been found to increase success in job interviews where competence is paramount (Forsythe Citation1990). Dressing down, in contrast, has been found to increase likeability (Sebastian and Bristow Citation2008).

Dressing in academia

Over the past few decades, a small body of research has provided some insight into students’ perceptions of their instructors’ dress. Rollman (Citation1977) offers the earliest examination, asking students to rate three photos of both male and female professors from the neck down (casual, semi-casual, formal). For both genders, increased formality was linked to an increase in perceptions of organisation and knowledgeability, but also to reductions in friendliness, sympathy, enthusiasm and, interestingly, the fairness of marking. Other studies have provided similar findings, with dress formality increasing perceived competence but decreasing measurements of likability (Lukavsky, Butler, and Harden Citation1995; Lightstone, Francis, and Kocum Citation2011). Morris et al. (Citation1996) supported the positive link between formality and perceived competence in an experimental study involving actors playing graduate teaching assistances. In a survey with students, Gorham, Cohen, and Morris (Citation1999) found some support that formality increased competence perceptions, while this effect was likely confounded with perceived age of the professor. No association was found between dress and likeability, while perceptions of extroversion increased with dress informality. Gorham, Cohen, and Morris’ (Citation1999) findings supported the latter association with extraversion in an experimental study (formal, casual professional, casual), yet provided little evidence regarding changes in competence perceptions. In contrast, a recent study by Chatelain (Citation2015) found that casual, as opposed to business casual and professional wear, reduced perceptions of credibility.

In sum, findings regarding the effects of dress formality in academia are mixed. Formality has been largely suggested to reinforce a projection of competence (or related characteristics); however, this relationship has been questioned (Gorham, Cohen, and Morris Citation1997; Sebastian and Bristow Citation2008). Perceptions of warmth have not been investigated, while liking or likability, a related construct, has been measured with mixed results, showing both negative and positive associations with formality. It is important to note that, although many of these studies examined gender of the professor and gender of the participants, only a few studies found differences in the effect of dress formality on perceptions. Morris et al. (Citation1996) found that increased perceived competence associated with formal dress was most pronounced for females rating female professors. Sebastian and Bristow (Citation2008) found that formally dressed male professors were perceived as more credible (in line with competence), while the opposite was shown for female professors.

The present research

The present research investigates the effect of academic dress formality on students’ perceptions of instructor warmth and competence. By explicitly investigating and distinguishing between perceptions of warmth versus competence, we disentangle the effect of dress formality more systematically. Based on extant research (Fiske Citation2018) and insight from the impression management literature (Sebastian and Bristow Citation2008; Peluchette, Karl, and Rust Citation2006; Cortina, Arel, and Smith-Darden Citation2017), we argue that dress formality is associated with competence, while dress informality with warmth. More formally, we hypothesise:

H1: Students will perceive instructors who dress formally as more competent than instructors who dress informally.

H2: Students will perceive instructors who dress informally as warmer than instructors who dress formally.

The three experimental studies of this research are set in the current student cohort, accounting for today’s teaching environment. Following a shift from traditional individualistic teaching styles to more connectivistic and experiential pedagogies (Kember, Leung, and Ma Citation2007; Gilis et al. Citation2008; Corbett and Spinello Citation2020), professor–student relationships are restructuring to a more ‘personalized education’ where staff are expected to also undertake pastoral roles (Lee and Schallert Citation2008). As a result, there have been recent research efforts to uncover links between connectivism and impacts on student psychological outcomes, such as attitudes, engagement and behaviours. A recent study by Gehlbach et al. (Citation2016) suggested that perceptions of student–teacher similarities had significant downstream effects on student grades. This idea of downstream effects has also been shown in other recent literature. Martin and Collie (Citation2019) investigated the impact of instructor–student relationships on academic development, suggesting that increased student relationships with instructors predicted student engagement. Pan et al. (Citation2009) found that students ranked ‘approachability’ as the most important teacher characteristic when it came to overall teaching effectiveness. In this new era, dressing more informally to foster warmth may be preferred by students; however, one could also suspect that perceptions of competence are vital for engaging students in an environment where professor–student relationships become more informal.

In order to understand such ‘downstream’ effects, this research examines the effects of warmth and competence perceptions on students’ evaluations of instructors and behaviour. Research on spill-over effects of impression traits, such as warmth and competence, suggests changes in impressions to impact subsequent evaluations of the presenter and behavioural intentions of the audience (Addison, Best, and Warrington Citation2006; Aaker, Vohs, and Mogilner Citation2010; Patrick Citation2011; Simon, Styczynski, and Gutsell Citation2020). This is further supported by social influence theory that implies perceived warmth and competence can increase amenability with requests, as the receiver has greater trust in the requester (e.g. Guadagno and Cialdini Citation2007). Marder et al. (Citation2019) provide support in the context of instructor impression formation. They find that emoticon usage in electronic communication sent by a professor had an effect on perceived warmth and competence, which in turn affected evaluation of a professor’s ability to provide feedback and students’ behavioural intentions. Nesdoly, Tulk, and Mantler (Citation2020) suggest that student likelihood to register in a given course increases when they perceive the teaching professor to be both warm and competent. Research by Widmeyer and Loy (Citation1988) investigated students’ perceptions based on perceived instructor warmth, suggesting that students who perceived the instructor as warm also believed them to be more pleasant, more sociable, more humorous and more effective, while also less formal, less irritable and less ruthless.

Uranowitz and Doyle (Citation1978) highlighted perceived warmth and competence as two important traits which increase the likeability of professors in the eyes of students. Davison and Price (Citation2009) suggest that characteristics aligning with both warmth (e.g. helpfulness, student centeredness) and competence (e.g. intellect, expertise) may significantly influence online student evaluations of teaching staff. Based on these findings, we argue that perceptions of both warmth and competence may affect evaluations and behavioural intentions positively. More formally, we hypothesise:

H3a: Students will be more likely to enroll in the course of an instructor who dresses formally, mediated by students’ increased perceptions of competence, compared to a course offered by an instructor who dresses informally.

H3b: Students will evaluate the ability to provide feedback of an instructor who dresses formally more favorably, mediated by students’ increased perceptions of competence, compared to an instructor who dresses informally.

H4a: Students will be less likely to enroll in the course of an instructor who dresses formally, mediated by students’ decreased perceptions of warmth, compared to a course offered by an instructor who dresses informally.

H4b: Students will evaluate the ability to provide feedback of an instructor who dresses formally less favorably, mediated by students’ decreased perceptions of warmth, compared to an instructor who dresses informally.

We also explore a number of moderating factors that may impact the effect of dress formality on evaluations and behavioural intentions but have been neglected in prior research. In Study 2, we test whether the communicated level of an academics’ success in staff profiles interact with dress formality to affect perceptions of warmth and competence. In Study 3, we test the possibility that dress formality effects may be a function of discipline dress norms, that is, that more formal clothing is expected in one discipline but not another, and, as such, affect the impact of dress formality on warmth and competence perceptions.

Experimental studies

We investigated the effect of academic dress in one pilot study and three experiments, employing various teaching scenarios within a business school setting. The pilot study provides an initial insight into the effect of dress formality on student perceptions. Experiments 1–3 formally test H1 through H4b, while employing variations in stimuli by using photographs (Study 1) or vignettes (Studies 2 and 3). Studies 2 and 3 explore the moderating effects of the variables of communicated success and congruence with discipline norms. All data were gathered through purposive sampling of current higher education students in the US, using panel data from Cloud Research, powered by Amazon Mechanical Turk, which is often used in similar research due to its efficiency and reliability (Law, Elliot, and Murayama Citation2012; Sommet and Elliot Citation2017; Mortensen and Hughes Citation2018).

Pilot study

A survey was administered (N = 145, 55 females, Mage = 27.99, SD = 6.41), where participants were exposed to images of six male and six female fictitious professors who wore attire of different levels of formality and stood in front of whiteboards. For each image, participants were asked to rate perceived formality of dress, perceived warmth and perceived competence on 7-point scales with one item each (Formality: ‘How casually/formally do you believe this professor was dressed?’ – ‘Very casual’ (1) to ‘Very formal’ (7); Warmth: ‘I perceive this professor to be warm’ – ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (7); Competence: ‘I perceive this professor to be competent’ – ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (7). Participants were also asked to indicate their own gender and age and to estimate each displayed professor’s age.

To investigate the effect of dress formality on perceived warmth and competence and to account for the repeated exposure of stimuli to participants and the within-subject variance, we ran Linear Mixed Models in SPSS 26.0 (West, Welch, and Galecki Citation2014), while controlling for participant and professor age and gender. The analysis provided preliminary support for H1; that is, the more formal a professor was perceived to dress, the more competent they were perceived (b = .06, F(1, 1587) = 16.81, p < .001), while controlling for estimated professor age (b = .01, F(1, 1531) = 81.07, p < .001). Gender of professor (p = .595), and gender (p = .541) and age of participant (p = .117) were not significant.

We found preliminary support for H2; the higher dress formality was perceived, the lower participants rated the professor’s warmth (b = −.08, F(1, 1630) = 22.23, p < .001), when controlling for participant age (b = .02, F(1, 143) = 4.25, p = .041) and estimated professor age (b = −.006, F(1, 1522) = 11.00, p = .001). Gender of participant (p = .991) and of displayed professor (p = .508) had no effect.

The results of this pilot study supported our expectations about an association between dress formality and perceptions of warmth and competence in academics.

Study 1

Design and participants

We tested H1 through H4 in a between-subjects design (dress: formal versus informal) on two different samples, with one being exposed to male instructors (N = 347, 177 females, Mage = 27.56, SD = 8.22, 274 undergraduate, and 73 postgraduate degree students), and one to female instructors (N = 338, 183 females, Mage = 27.60, SD = 7.86, 265 undergraduate students, and 73 postgraduate degree students). As prior work has shown differences in perceived formality may exist due to gender expectations (e.g. Chatelain Citation2015), and as formal wear for females and males generally differs and may be difficult to completely control for, we decided to test the effect of formality separately for female and male instructors. Each participant was randomly assigned and exposed to only one condition. Pre-screening questions ensured the sample met the inclusion criteria.

Stimuli, procedure and measures

We used photographs as experimental stimuli, as they often activate the same neuronal processes as real-life situations (Brodeur, Guérard, and Bouras Citation2014). In each condition, a model posed as an instructor. All instructors were placed in identical classroom settings, shown standing in front of a whiteboard. To reduce potential bias, each element of the instructors’ outfits in each experimental variation was identical in colour, style and fit, from the same retailer. The informal outfit consisted of black running shoes, navy-blue jeans and a navy-blue zip-up hoodie. The formal outfit consisted of black dress shoes or heels (male or female), navy-blue dress pants, a white button-up shirt and a navy-blue suit jacket. Models maintained the same facial expressions between conditions.

In the experiment, participants were first asked to imagine they were entering the fourth year of their undergraduate degree. A description of a fictitious university and optional course to enrol in which the photographed instructor would be leading followed. Participants were told the instructor was 30–35 years old and were presented with one of the four images. We used a page timer to ensure that participants inspected the picture for a minimum of six seconds.

Subsequently, participants were exposed to the manipulation check measure. Respondents rated the level of dress formality on two 7-point items (‘How casually/formally do you believe the instructor was dressed?’ – ‘Very casual’ (1) to ‘Very formal’ (7); ‘How informally/formally do you believe the instructor was dressed?’ – ‘Very informal’ (1) to ‘Very formal’ (7), r = .923). Additionally, we checked for participants’ perceptions of the instructor’s gender (1 = male, 2 = female).

Student perceptions of instructor warmth and competence were measured using a 3-item, 7-point differential semantic scale for each (Warmth: ‘cold’ vs. ‘warm’, ‘unfriendly’ vs. ‘friendly’, ‘unpleasant’ vs. ‘pleasant’, α = .842; Competence: ‘clumsy’ vs. ‘skillful’, ‘incompetent’ vs. ‘competent’, ‘unqualified’ vs. ‘qualified’, α = .883), adopted from Marder et al. (Citation2019). Intentions to enrol in the specified instructor’s course (compared to an alternative course they were told they were eligible for) were also measured, using a 3-item, 7-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘I would choose the course pitched by the instructor pictured, instead of the alternative’, α = .934).

In order to evaluate the displayed instructor’s overall ability, participants were asked to read a short extract of feedback they were to imagine they received from the advisor. Students’ evaluations of instructor abilities were measured using a 4-item, 7-point semantic differential scale (e.g. ‘How would you rate this instructors’ ability to give feedback?’, α = .912), adapted from Marder et al. (Citation2019). A full list of measures, items, and reliability is shown in Appendix 1.

Lastly, three control variables were collected: age and gender of participant, and their own formality of dress measured with one item on a 7-point semantic differential scale (‘When you attend classes, how do you dress?’ – ‘Very casual’ (1) to ‘Very formal’ (7)).

Analysis and results

Two one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs), one for each sample (male instructor; female instructor) were run including the three control variables. Results supported the dress formality manipulation in both samples (Male: MFormal = 5.96, SE = 0.06 vs. MInformal = 2.46, SE = 0.11, F(4, 342) = 839.61, p < .001, η2 = 0.711; Female: MFormal = 5.56, SE = 0.06 vs. MInformal = 2.70, SE = 0.11, F(4, 333) = 530.86, p < .001, η2 = 0.615). We tested the interaction between formality and degree level (undergraduate/postgraduate degrees) on perceived warmth and competence in order to ensure there were no significant differences between groups. No significant interaction was found (ps > .760).

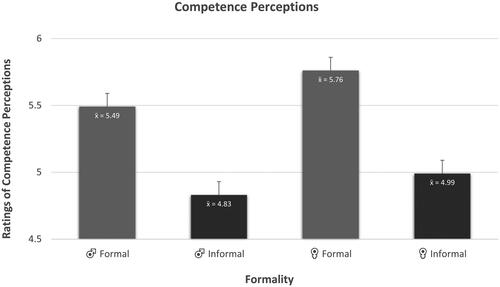

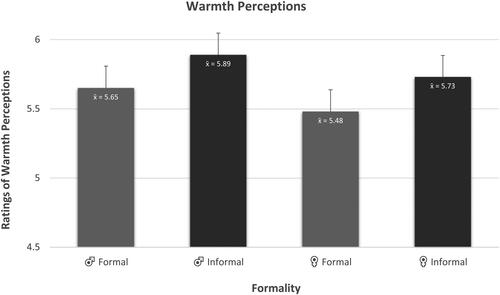

To investigate H1 and H2, we ran two multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs), one for each sample, including all three control variables. The results supported both hypotheses. Formality increased perceptions of competence for both samples (Male: MFormal = 5.49, SE = 0.09 vs. MInformal = 4.83, SE = 0.09, p = .000, η2 = 0.066; Female: MFormal = 5.76, SE = 0.09 vs. MInformal = 4.99, SE = 0.09, p = .000, η2 = 0.098). In contrast and as expected, formality decreased perceptions of warmth for both male and female instructors (Male: MFormal = 5.65, SE = 0.07 vs. MInformal = 5.89, SE = 0.07, p = .016, η2 = 0.017; Female: MFormal = 5.48, SE = 0.08 vs. MInformal = 5.73, SE = 0.08, p = .022, η2 = .016) (see and ). F-statistics and regression coefficients for the control variables are summarised for this and the subsequent studies in .

Table 1. Summary of MANCOVA results for Studies 1, 2 and 3.

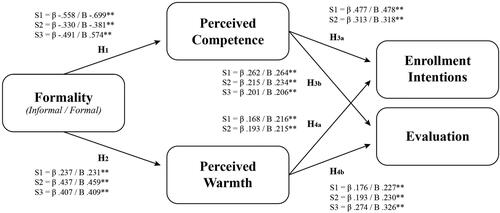

In order to test H3a, H3b, H4a and H4b, we investigated perceived warmth and competence as parallel mediators in the relationships between formality and the dependent variables, intention to enrol and evaluation of instructor. We ran two bootstrapped mediation analyses (Preacher and Hayes Citation2008) in Process v3.4, an add-on macro to SPSS (Hayes Citation2018) to test the model (), with 5000 bootstrapping samples and a confidence level of 95%, while controlling for differences in instructor gender along with the three control variables. Mediation results for this and all subsequent studies are summarised in . The results supported our expectations that perceptions of both warmth and competence mediated the relationships between dress formality and intention to enrol and instructor evaluations. While dressing formally had a positive effect on intentions and evaluations through increased perceptions of competence (H3a, 3b), it also had a negative effect on intentions and evaluations through decreased perceptions of warmth (H4a, 4b).

Table 2. Summary of indirect effects (mediations).

Study 2

In Study 2, we explore the possibility that the explicit communication of success (i.e. through personal profile excerpts) might mitigate the negative effect of dress informality on perceptions of competence. We base this assumption on prior psychological literature on status and self-promotional behaviour. Honest self-promotion, that is, any self-promotion that depicts an accurate description of past experiences, skills or abilities, has been linked to increased perceptions of competence (Amaral, Powell, and Ho Citation2019). Higher-status experience would convey higher levels of perceived competence and skill, when compared to lower-status work (Brambilla et al. Citation2010). Within an academic context, research supports these notions, highlighting that communicating qualifications may be a successful strategy to increase perceived competence. Studies have found that less cited professors displayed more professional titles in their email signature and lower-status universities presented more professional titles on their departmental website (Harmon-Jones, Schmeichel, and Harmon-Jones Citation2009). Communicated success might mitigate the negative effect of dress informality.

Design and participants

Study two employed a 2 (formality: formal versus informal) × 3 (success communicated: high, low, control) between-subjects design. We used the same sampling method with the same inclusion criteria as before and allocated participants randomly to one of the six conditions. The sample included 429 students (207 females, Mage = 27.80 years, SD = 7.20; 319 undergraduate, and 110 postgraduate degree students).

Stimuli, procedure and measures

In order to avoid employing two different samples as in Study 1, we opted to use vignettes with text, in which an instructor with a gender-neutral name, ‘Dr. Alex Taylor’, was presented. We developed six vignettes, following Rungtusanatham, Wallin and Eckerd’s (2011) recommendations to ensure clarity, realism and reliability. Participants were asked to imagine they were studying their final year in an undergraduate program at a business school, with the option of enrolling in a course pitched by the instructor, Dr. Alex Taylor. After this introduction, respondents were presented with the communicated success manipulation. This involved participants reading extracts from the instructor’s staff profile at the university. In the high communicated success condition, participants were told that the instructor received their PhD in business management from Harvard, the instructor was described as a globally renowned business researcher, with vast experience working within executive-level firms, often invited to comment in renowned business outlets. For the low communicated success condition, the profile described the instructor as a PhD in business management graduate who consulted for local companies. The instructor was also noted to run their own blog, where they discussed their personal views of business-related topics. In the control condition, no profile information was provided.

The description of the instructor’s attire followed. In the formal condition, the instructor was described as wearing dress shoes, formal black pants, a tailored blazer layered over a white button-down, collared shirt, standing next to their leather briefcase. In the informal condition, they wore sneakers, jeans, an unzipped hoodie layered over a white t-shirt and stood next to their backpack. The formality manipulation was inspired by prior work into academic attire by Lightstone, Francis, and Kocum (Citation2011).

Manipulation checks followed the stimulus exposure. To ensure that students perceived the communicated success as intended, we measured participants’ perceptions using a 4-item, 7-point Likert scale matrix (e.g. ‘Dr. Alex Taylor has had an extremely successful career’, α = 0.908). We employed the same manipulation check for dress formality as in Study 1.

As in Study 1, we measured intention to enrol and instructor evaluation, and we concluded the study by measuring the same control variables with one addition, a fourth control variable which measured participant’s knowledge on ‘what it takes to be perceived as successful in the eyes of academic peers’ on one item with a 7-point semantic differential scale (‘not knowledgeable at all’ (1) to ‘extremely knowledgeable’ (7)).

Analysis and results

ANCOVAs supported the manipulations. Instructors in the high communicated success condition were perceived as more successful than instructors in the low condition, while instructors in the control condition were perceived the least successful (MHighSuccess = 5.88, SE = 0.08 vs. MLowSuccess = 5.36, SE = 0.08 vs. MNoSuccess = 5.00, SE = 0.08, F(6, 422) = 31.22, p < .001, η2 = 0.129). Respondents perceived instructors in formal attire to be more formally dressed than instructors in casual clothes (MFormal = 5.45, SE = 0.10 vs. MInformal = 2.72, SE = 0.10, F(5, 423) = 369.92, p < .001, η2 = .467).

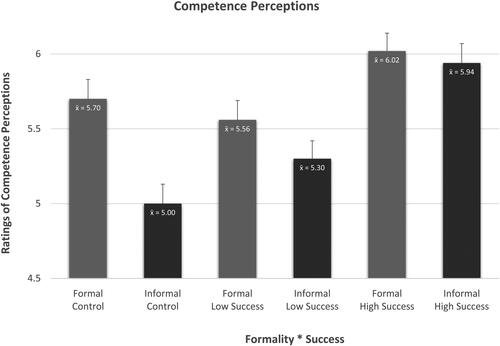

In order to investigate the effect of the manipulations and their interaction, we ran a MANCOVA. Effects are summarised in . While we found a significant interaction term for perceptions of competence, perceptions of warmth were only affected by the dress formality but not by the communicated success manipulation. For perceptions of competence, the dress formality effect depended on the communicated success (see ). While instructors being displayed as highly successful were generally perceived as more competent than those in the low success or control conditions (MHighSuccess = 5.98, SE = 0.09 vs. MLowSuccess = 5.43, SE = 0.09 vs. MControl = 5.35, SE = 0.09, p < .001, η2 = 0.064), this effect was further qualified by a significant interaction term (p = .044). In the control condition where instructor’s success was not communicated, the results mirrored those of Study 1, with formal (informal) attire increasing (decreasing) perceptions of competence (MFormal = 5.70, SE = 0.13, vs. MInformal = 5.00, SE = 0.13, p < .001, η2 = 0.025), supporting H1. However, when success was communicated, irrespective of its level, instructors were perceived as equally competent across formality treatments (MFormal/LowSuccess = 5.56, SE = 0.13, vs. MInformal/LowSuccess = 5.30, SE = 0.12, p = .152; MFormal/HighSuccess = 6.02, SE = 0.12, vs. MInformal/HighSuccess = 5.94, SE = 0.13, p = .710).

In contrast, perceptions of warmth were independent from communicated success. When the instructor was dressed informally, they were perceived warmer than when dressed formally (MFormal = 5.13, SE = 0.07 vs. MInformal = 5.59, SE = 0.07, p < .001, η2 = .050), irrespective of communicated success (ps > .26), supporting H2.

In order to test H3a through H4b, we ran two bootstrapped mediation analyses for both intention to enrol and instructor evaluation (). Since communicated success had no effect on warmth, we ran a serial mediation while including the dummy-coded success manipulation variable as control variable. As in Study 1, the results supported the mediation in that increased (decreased) perceptions of competence from formality (informality) affected the dependent measures positively (negatively), while decreased (increased) perceptions of warmth from formality (informality) affected the dependent measures negatively (positively).

Study two demonstrated that dressing formally only unfolded its positive effect through perceptions of competence when no other information (such as success) was available. When success was communicated, instructors were perceived as equally competent when dressed both formally and informally, while perceptions of warmth remained a function of dress formality.

Study 3

In Study 3, we explore the possibility of a discipline effect. We expected students would hold different stereotypical beliefs about dress codes in different business school disciplines; for example, students might expect a marketing professor to dress less formally than a finance professor (Alston Citation2020). Links between dress attire, stereotypes and competence perceptions have been touched upon in the literature. Wookey, Graves, and Butler (Citation2009) have investigated the relationship between attire and job role, finding that women in higher-status roles who are dressed in business attire were viewed as more intelligent, capable and competent than those dressed in provocative attire. The findings were opposite for women in lower-status roles, with competence perceptions being higher in provocative attire, suggesting that cohesion between one’s role and attire choices may impact perceptions. Dellinger (Citation2002) investigated dress norms within various disciplines, finding that ‘the suit’ embodies the standard business professional in accounting and finance fields, while noting that in more creative roles dress formality may not be so strict.

Media suggestions on job-acceptable dress code aligns with our expectations, stating that in finance, a smart suit, shirt and tie is expected, while creatives, such as marketers or media executives, have more freedom in their attire (Gao Citation2020). Such normative beliefs on discipline and role stereotypes, in turn, should affect perceptions of warmth and competence, in that negative effects of informality on perceived competence should be mitigated in a discipline with a less formal dress code.

Design and participants

We employed a 2 (formality: formal versus informal) × 2 (discipline norm: formal versus informal) between-subjects design, following the same sampling and randomisation procedures as before. A total of 247 students participated (122 females, Mage = 27.38 years, SD = 7.02; 180 undergraduate, and 67 postgraduate degree students).

Stimuli, procedure and measures

As in Study 2, participants were asked to imagine they were studying in their final year of a business school undergraduate degree, with the choice of enrolling into an optional course run by the instructor specified in the vignette. Dress formality was manipulated the same way as in Study 2. The second manipulation, discipline norm, was operationalised through the type of the course the instructor led. The instructor in the informal discipline norm condition led the course ‘Creative Digital Brand Management’, and in the formal discipline norm condition, the course presented was ‘Financial Statement Analysis Management’. Each course had a brief headline-description.

Manipulation checks followed. Dress formality was measured as in the previous studies (r = .879). To check the manipulation of discipline norm, we tested to what extent the described instructor dressed according to the norm of the respective discipline of the presented course on three, 7-point differential scale items (‘Now rate how the instructor was dressed compared to those people who are employed in the field’ – ‘Inappropriate’ (1) vs. ‘Appropriate’ (7); ‘Dissimilar’ (1) vs. ‘Similar’ (7); ‘Incongruent’ (1) vs. ‘Congruent’ (7), α = .908).

Perceived warmth (α = .772), competence (α = .887) and instructor evaluation (α = .904) were measured as in the previous studies. We measured participant perceptions of instructor influence as a complementary alternative to behavioural intention measures in the previous studies. In doing so, we used a 3-item, 7-point Likert scale (e.g. ‘The instructor has a strong impact on student behaviour’, α = .731). We concluded the questionnaire with the three control variables as before.

Analysis and results

An ANCOVA supported the formality manipulation (MFormalDress = 5.47, SE = 0.11 vs. MInformalDress = 2.98, SE = 0.12, F(4, 242) = 237.035, p < .001, η2 = 0.495). In order to test the discipline norm manipulation, we ran a one-sample Student’s t-test against the mid-point of the scale (4), which demonstrated that instructors were perceived to dress according to norms of the respective discipline (MNorm = 5.26, t(246) = 17.92, p < .001, d = 1.145).

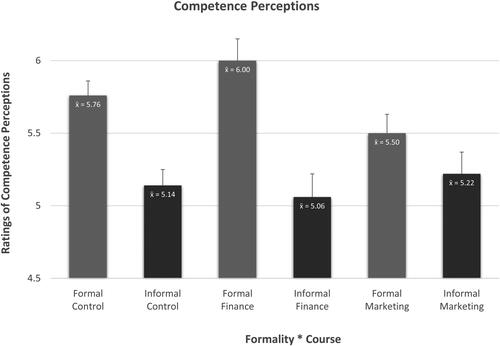

In order to test the effect of the manipulations on perceptions of warmth, competence, instructor evaluation and instructor influence, we ran a MANCOVA. Similarly to Study 2, perceptions of warmth decreased (increased) when instructors were dressed formally (informally) (MFormalDress = 5.13, SE = 0.09 vs. MInformalDress = 5.53, SE = 0.09, p = .003, η2 = 0.037), while discipline norm did not affect it, neither directly nor in interaction with dress formality (ps > .16), supporting H2. While perceptions of competence generally increased with dress formality (MFormalDress = 5.76, SE = 0.10 vs. MInformalDress = 5.14, SE = 0.11, p < .001, η2 = 0.069), this effect was further qualified by a significant interaction term. Formal attire increased perceptions of competence in the finance discipline (MFormalDress/Finance = 6.00, SE = 0.15 vs. MInformalDress/Finance = 5.06, SE = 0.16, p < .001), but dress formality had no significant effect when the instructor led a marketing-related course (MFormalDress/Marketing = 5.50, SE = 0.13 vs. MInformalDress/Marketing = 5.22, SE = 0.15, p = .136), supporting H1 only for a discipline with a more formal dress code (see ).

Lastly, we ran two bootstrapped mediation analyses as in Study 2, controlling for discipline norm. The results () supported H3a through H4b; while increased (decreased) perceived warmth derived from dress informality (formality) impacted instructor evaluation and instructor influence positively (negatively), increased (decreased) perceived competence from dress formality (informality) had a positive (negative) effect on the dependent variables.

Discussion

In a series of experiments, this investigation consistently demonstrated that the level of dress formality in academia affects perceptions of instructors’ warmth and competence. We showed that while dress casualty or informality had a positive impact on perceptions of warmth throughout, perceptions of competence were influenced by other information cues (i.e. communicated success and discipline norms). While dress informality affected perceptions of competence negatively, this effect could be mitigated when instructor’s success was communicated explicitly (Study 2) or when the instructor’s background was a discipline with more informal dressing norms (Study 3). We showed that perceptions of warmth and competence had consequences for students’ evaluations of instructors and students’ behavioural intentions to enrol in a course.

Theoretical contributions and practical implications

We provide the first focussed examination of instructor dress on the ‘big two’, warmth and competence. While our findings largely support prior research that found formality to increase competence (Lukavsky, Butler, and Harden Citation1995; Lightstone, Francis, and Kocum Citation2011) the inclusion of warmth provides a more fine-grained picture and a possible reconciliation of existing contrasting findings on formality and likability (Gorham, Cohen, and Morris Citation1999). We considered the potential trade-off between desired levels of perceived competence versus warmth when choosing to dress more or less formally. Our findings demonstrate that perceptions of competence may be a function of other, either more factual information cues (Study 2: success communication) or of information cues that are less objective (Study 3: discipline norms), irrespective of the level of dress formality. Perceptions of warmth remained a function of dress formality only. Not only does this show that dressing informally can lead to perceptions of warmth and competence when other cues are present, but is also theoretically interesting insofar as perceptions of competence seem to be more malleable to other information.

Though not directly tested as a moderator, the findings of Study 1 suggest that changes in warmth and competence occur irrespective of gender. This is in contrast to other researchers, who found significant differences in impression attribution dependent on gender (Kierstead, D’Agostino, and Dill Citation1988; Sebastian and Bristow Citation2008). This suggests that societal efforts towards dismantling gender stereotypes in the workplace may have been stepping in the right direction.

Our findings contribute with knowledge about downstream effects of dress formality. They corroborate extant literature that suggests perceptions of likability, here warmth, are a significant determinative factor of student–professor ratings and evaluations (Elmore and LaPointe Citation1975; Shevlin et al. Citation2000; Patrick Citation2011; Marder et al. Citation2019). We show not only that increases in evaluations arise from increases in perceived competence (and warmth), but also that competence (warmth) perceptions affect evaluations of actual written feedback, rather than of photographic stimuli. Our findings similarly align with previous research, which suggest that student perceptions of characteristics within teaching environments play an important role in evaluations (Basow Citation1995; Church, Elliot, and Gable Citation2001; Pan et al. Citation2009; Patrick Citation2011; Merkt et al. Citation2020). While our experiments specifically focus on formality within attire, future research may investigate other non-verbal stimuli in higher education environments.

Our findings suggest that intentions to enrol in a specified professor’s course are mediated by both perceived warmth and competence. This aligns directly with recent research by Nesdoly, Tulk, and Mantler (Citation2020), which suggests that students indicate higher likelihood of course registration when professors are perceived to be more caring and of higher teaching quality. It is clearly an important avenue for future research to find opportunities that may diminish decreases in perceptions of warmth as competence increases, or competence as warmth increases.

The findings of this research allow for valuable advice to higher education managers and practitioners. Teaching staff who face instructor evaluations which explicitly measure warmth-based attributes (e.g. approachability, flexibility, respect) may consider dressing more informally. By communicating successes more explicitly, such as sharing significant work/education-related experiences, informally dressed professors may compensate for potential losses in competence perceptions. If teaching staff are focussed on increasing competence-based students’ evaluations, they may consider dressing more formally, keeping in mind that this may result in a loss of warmth perceptions. Factors external to the person and their success may influence competence perceptions; it is therefore important that professors understand surrounding discipline norms before following these suggestions.

This research was conducted prior to the COVID19 pandemic. Teaching has taken a dramatic and rapid shift towards virtual teaching environments, which led us to ponder if the same impacts of instructor formality would exist in online environments. This led to a fourth experiment (N = 220) similar to the first three studies. The two-condition experiment contained short video clips of a professor pitching a generic business course from their home in either a formal or informal outfit in front of a filled bookshelf.

The results from this post hoc experiment suggest that impressions of instructor dress formality differ in virtual learning environments, when contrasted against offline environments. Dressing formally did not reduce warmth in this set-up. We propose that instructors are seen as inherently warmer when lecturing from home as opposed to the colder and more sterile seeming lecture theatre environments. Although the rise in competence perceptions are still significant, the effects are far more modest than in the previous experiments. With such a minimal effect, we suggest that instructors not stress about what they wear in virtual teaching environments.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our research adopted a multi-study experimental design, focussing on increasing internal validity and reliability. While our findings support more informal professor dress to increase warmth perceptions, there is a key balance staff must meet in order to fulfil both workplace duties and service provisions. Future research in this area is warranted. While we found two information cues to affect perceived competence ratings while warmth perceptions remained unaffected, future research may investigate information cues or conditions that may mitigate negative effects of formality on warmth.

While the differences based on instructor gender were touched upon in this study, they were not fully investigated. We believe it would be both interesting and timely for future research to focus on understanding the impact of gender on formality-based impression formation. Developing a deeper understanding of this topic could also aid in shining a light on the impacts of recent societal pushes towards gender equality in the workplace.

Although self-reporting of behavioural intent is common in relevant literature, we cannot claim actual behaviours. Future research that validates these intentions through real-world behaviours is clearly necessary. Student participants were mainly from western higher education institutions, where hierarchical relationships are often deemed ‘softer’ than in other cultures. Researchers may take this opportunity to expand our findings to a variety of cultural contexts.

It is also important to note that our research is limited to business school faculty and students. We suggest that future research should investigate the role of attire formality on warmth and competence perceptions within other higher education schools.

Due to some unbalance across group sample size in our experiments, we recommend generalising our results be done with caution. Future research is needed to further support our results while ensuring an exactly balanced sample. More research should also focus on investigating the role of warmth and competence related perceptions within virtual teaching environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aaker, J., K. Vohs, and C. Mogilner. 2010. “Non-Profits Are Seen as Warm and for-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (2): 224–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1540134.

- Abele, A. E., and S. Bruckmüller. 2011. “The Bigger One of the “Big Two”? Preferential Processing of Communal Information.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (5): 935–948. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.028.

- Addison, W. E., J. Best, and J. D. Warrington. 2006. “Students’ Perceptions of Course Difficulty and Their Ratings of the Instructor.” College Student Journal 40 (2): 409.

- Alston, J. M. 2020. “Dress Code for Economic Conferences: What to Wear and What to Avoid.” https://inomics.com/advice/dress-code-for-economic-conferences-what-to-wear-and-what-to-avoid-48004.

- Amaral, A. A., D. M. Powell, and J. L. Ho. 2019. “Why Does Impression Management Positively Influence Interview Ratings? The Mediating Role of Competence and Warmth.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment 27 (4): 315–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12260.

- Baron, R. A. 1986. “Self-Presentation in Job Interviews: When There Can Be "Too Much of a Good Thing”.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 16 (1): 16–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb02275.x.

- Basow, S. 1995. “Student Evaluations of College Professors: When Gender Matters.” Journal of Educational Psychology 87 (4): 656–665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.4.656.

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117 (3): 497–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Bolton, D., and R. Nie. 2010. “Creating Value in Transnational Higher Education: The Role of Stakeholder Management.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 9 (4): 701–714. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.9.4.zqr701.

- Bozeman, D. P., and K. M. Kacmar. 1997. “A Cybernetic Model of Impression Management Processes in Organizations.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 69 (1): 9–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.2669.

- Brambilla, M., S. Sacchi, F. Castellini, and P. Riva. 2010. “The Effects of Status on Perceived Warmth and Competence.” Social Psychology 41 (2): 82–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000012.

- Brodeur, M. B., K. Guérard, and M. Bouras. 2014. “Bank of Standardized Stimuli (BOSS) Phase II: 930 New Normative Photos.” PLoS ONE 9 (9): e106953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106953.

- Brown, G. D. A., A. M. Wood, R. S. Ogden, and J. Maltby. 2015. “Do Student Evaluations of University Reflect Inaccurate Beliefs or Actual Experience? A Relative Rank Model.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 28 (1): 14–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1827.

- Cardon, P. W., and E. A. Okoro. 2009. “Professional Characteristics Communicated by Formal versus Casual Workplace Attire.” Business Communication Quarterly 72 (3): 355–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569909340682.

- Chatelain, A. M. 2015. “The Effect of Academics’ Dress and Gender on Student Perceptions of Instructor Approachability and Likeability.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 37 (4): 413–423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080x.2015.1056598.

- Church, M. A., A. J. Elliot, and S. L. Gable. 2001. “Perceptions of Classroom Environment, Achievement Goals, and Achievement Outcomes.” Journal of Educational Psychology 93 (1): 43–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.43.

- Corbett, F., and E. Spinello. 2020. “Connectivism and Leadership: Harnessing a Learning Theory for the Digital Age to Redefine Leadership in the Twenty-First Century.” Heliyon 6 (1): e03250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03250.

- Cortina, K. S., S. Arel, and J. P. Smith-Darden. 2017. “School Belonging in Different Cultures: The Effects of Individualism and Power Distance.” Frontiers in Education 2: 56. [Mismatch] doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00056.

- Cuddy, A. J. C., S. T. Fiske, V. S. Y. Kwan, P. Glick, S. Demoulin, J.-P. Leyens, M. H. Bond, et al. 2009. “Stereotype Content Model across Cultures: Towards Universal Similarities and Some Differences.” The British Journal of Social Psychology 48 (Pt 1): 1–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608x314935.

- Dacy, J. M., and S. L. Brodsky. 1992. “Effects of Therapist Attire and Gender.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 29 (3): 486–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088555.

- Davison, E., and J. Price. 2009. “How Do we Rate? An Evaluation of Online Student Evaluations.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (1): 51–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801895695.

- Dellinger, K. 2002. “Wearing Gender and Sexuality “on Your Sleeve”: Dress Norms and the Importance of Occupational and Organizational Culture at Work.” Gender Issues 20 (1): 3–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-002-0005-5.

- Eisenberg, J., C. E. J. Härtel, and G. K. Stahl. 2013. “From the Guest Editors: Cross-Cultural Management Learning and Education—Exploring Multiple Aims, Approaches, and Impacts.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 12 (3): 323–329. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2013.0182.

- Elmore, P. B., and K. A. LaPointe. 1975. “Effect of Teacher Sex, Student Sex, and Teacher Warmth on the Evaluation of College Instructors.” Journal of Educational Psychology 67 (3): 368–374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076608.

- Fiske, S. T. 2018. “Stereotype Content: Warmth and Competence Endure.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 27 (2): 67–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417738825.

- Forsythe, S. M. 1990. “Effect of Applicant’s Clothing on Interviewer’s Decision to Hire.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 20 (19): 1579–1595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1990.tb01494.x.

- Friedlander, M. L., and G. S. Schwartz. 1985. “Toward a Theory of Strategic Self-Presentation in Counseling and Psychotherapy.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 32 (4): 483–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.32.4.483.

- Gao, M. 2020. “How to Dress for Different Professions?” https://www.mrdraper.com/blog/article/how-to-dress-for-different-professions.

- Gardner, W. L., and M. J. Martinko. 1988. “Impression Management in Organizations.” Journal of Management 14 (2): 321–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400210.

- Gehlbach, H., M. E. Brinkworth, A. M. King, L. M. Hsu, J. McIntyre, and T. Rogers. 2016. “Creating Birds of Similar Feathers: Leveraging Similarity to Improve Teacher–Student Relationships and Academic Achievement.” Journal of Educational Psychology 108 (3): 342–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000042.

- Gilis, A., M. Clement, L. Laga, and P. Pauwels. 2008. “Establishing a Competence Profile for the Role of Student-Centred Teachers in Higher Education in Belgium.” Research in Higher Education 49 (6): 531–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9086-7.

- Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Gorham, J., S. H. Cohen, and T. L. Morris. 1997. “Fashion in the Classroom II: Instructor Immediacy and Attire.” Communication Research Reports 14 (1): 11–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099709388641.

- Gorham, J., S. H. Cohen, and T. L. Morris. 1999. “Fashion in the Classroom III: Effects of Instructor Attire and Immediacy in Natural Classroom Interactions.” Communication Quarterly 47 (3): 281–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379909385560.

- Guadagno, R. E., and R. B. Cialdini. 2007. “Persuade Him by Email, But See Her in Person: Online Persuasion Revisited.” Computers in Human Behavior 23 (2): 999–1015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.08.006.

- Harmon-Jones, C., B. J. Schmeichel, and E. Harmon-Jones. 2009. “Symbolic Self-Completion in Academia: Evidence from Department Web Pages and Email Signature Files.” European Journal of Social Psychology 39 (2): 311–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.541.

- Hayes, A. F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Holoien, D. S., and S. T. Fiske. 2013. “Downplaying Positive Impressions: Compensation between Warmth and Competence in Impression Management.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49 (1): 33–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.09.001.

- Howlett, N., K. Pine, I. Orakçıoğlu, and B. Fletcher. 2013. “The Influence of Clothing on First Impressions.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 17 (1): 38–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021311305128.

- Johnson, K., S. J. Lennon, and N. Rudd. 2014. “Dress, Body and Self: Research in the Social Psychology of Dress.” Fashion and Textiles 1 (1): 20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-014-0020-7.

- Kember, D., D. Y. P. Leung, and R. S. F. Ma. 2007. “Characterizing Learning Environments Capable of Nurturing Generic Capabilities in Higher Education.” Research in Higher Education 48 (5): 609–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-006-9037-0.

- Kervyn, N., H. B. Bergsieker, F. Grignard, and V. Y. Yzerbyt. 2016. “An Advantage of Appearing Mean or Lazy: Amplified Impressions of Competence or Warmth after Mixed Descriptions.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 62: 17–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.09.004.

- Kierstead, D., P. D’Agostino, and H. Dill. 1988. “Sex Role Stereotyping of College Professors: Bias in Students’ Ratings of Instructors.” Journal of Educational Psychology 80 (3): 342–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.342.

- Knouse, S. B. 1994. “Impressions of the Resume: The Effects of Applicant Education, Experience, and Impression Management.” Journal of Business and Psychology 9 (1): 33–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230985.

- Law, W., A. J. Elliot, and K. Murayama. 2012. “Perceived Competence Moderates the Relation between Performance-Approach and Performance-Avoidance Goals.” Journal of Educational Psychology 104 (3): 806–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027179.

- Lee, G., and D. L. Schallert. 2008. “Constructing Trust between Teacher and Students through Feedback and Revision Cycles in an EFL Writing Classroom.” Written Communication 25 (4): 506–537. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088308322301.

- Li, X., K. W. Chan, and S. Kim. 2019. “Service with Emoticons: How Customers Interpret Employee Use of Emoticons in Online Service Encounters.” Journal of Consumer Research 45 (5): 973–987. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy016.

- Lightstone, K., R. Francis, and L. Kocum. 2011. “University Faculty Style of Dress and Students’ Perception of Instructor Credibility.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 2 (15): 15–22.

- Lukavsky, J., S. Butler, and A. J. Harden. 1995. “Perceptions of an Instructor: Dress and Students’ Characteristics.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 81 (1): 231–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.81.1.231.

- Macfarlane, B. 2011. “Professors as Intellectual Leaders: Formation, Identity and Role.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (1): 57–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903443734.

- Marder, B., D. Houghton, A. Erz, L. Harris, and A. Javornik. 2019. “Smile(y) – and Your Students Will Smile with You? The Effects of Emoticons on Impressions, Evaluations, and Behaviour in Staff-to-Student Communication.” Studies in Higher Education 45: 2274–2286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1602760.

- Martin, A. J., and R. J. Collie. 2019. “Teacher–Student Relationships and Students’ Engagement in High School: Does the Number of Negative and Positive Relationships with Teachers Matter?” Journal of Educational Psychology 111 (5): 861–876. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000317.

- Merkt, M., S. Lux, V. Hoogerheide, T. van Gog, and S. Schwan. 2020. “A Change of Scenery: Does the Setting of an Instructional Video Affect Learning?” Journal of Educational Psychology 112 (6): 1273–1283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000414.

- Morris, T., J. Gorham, S. Cohen, and D. Huffman. 1996. “Fashion in the Classroom: Effects of Attire on Student Perceptions of Instructors in College Classes.” Communication Education 45 (2): 135–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529609379043.

- Mortensen, K., and T. L. Hughes. 2018. “Comparing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Platform to Conventional Data Collection Methods in the Health and Medical Research Literature.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 33 (4): 533–538. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4246-0.

- Nesdoly, N., C. Tulk, and J. Mantler. 2020. “The Effects of Perceived Professor Competence, Warmth and Gender on Students’ Likelihood to Register for a Course.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (5): 666–679. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1689381.

- Pan, D., G. S. H. Tan, K. Ragupathi, K. Booluck, R. Roop, and Y. K. Ip. 2009. “Profiling Teacher/Teaching Using Descriptors Derived from Qualitative Feedback: Formative and Summative Applications.” Research in Higher Education 50 (1): 73–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9109-4.

- Patrick, C. 2011. “Student Evaluations of Teaching: Effects of the Big Five Personality Traits, Grades and the Validity Hypothesis.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (2): 239–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903308258.

- Paulhus, D. L., B. G. Westlake, S. S. Calvez, and P. D. Harms. 2013. “Self-Presentation Style in Job Interviews: The Role of Personality and Culture.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (10): 2042–2059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12157.

- Peluchette, J. V., K. Karl, and K. Rust. 2006. “Dressing to Impress: Beliefs and Attitudes regarding Workplace Attire.” Journal of Business and Psychology 21 (1): 45–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-005-9022-1.

- Preacher, K. J., and A. F. Hayes. 2008. “Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models.” Behavior Research Methods 40 (3): 879–891. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879.

- Rollman, S. A. 1977. “Nonverbal Communication in the Classroom: Some Effects of Teachers’ Style of Dress upon Students’ Perceptions of Teachers’ Characteristics.” Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University.

- Rungtusanatham, M., C. Wallin, and S. Eckerd. 2011. “The Vignette in a Scenario-Based Role-Playing Experiment.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 47 (3): 9–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493x.2011.03232.x.

- Russell, A. M. T., and S. T. Fiske. 2008. “It’s All Relative: Competition and Status Drive Interpersonal Perception.” European Journal of Social Psychology 38 (7): 1193–1201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.539.

- Sebastian, R. J., and D. Bristow. 2008. “Formal or Informal? The Impact of Style of Dress and Forms of Address on Business Students’ Perceptions of Professors.” Journal of Education for Business 83 (4): 196–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/joeb.83.4.196-201.

- Shevlin, M., P. Banyard, M. Davies, and M. Griffiths. 2000. “The Validity of Student Evaluation of Teaching in Higher Education: Love Me, Love my Lectures?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 25 (4): 397–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713611436.

- Shin, J. C., and R. K. Toutkoushian. 2011. The Past, Present, and Future of University Rankings, 1–16. Netherlands: Springer.

- Simon, J. C., N. Styczynski, and J. N. Gutsell. 2020. “Social Perceptions of Warmth and Competence Influence Behavioral Intentions and Neural Processing.” Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience 20 (2): 265–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-019-00767-3.

- Sommet, N., and A. J. Elliot. 2017. “Achievement Goals, Reasons for Goal Pursuit, and Achievement Goal Complexes as Predictors of Beneficial Outcomes: Is the Influence of Goals Reducible to Reasons?” Journal of Educational Psychology 109 (8): 1141–1162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000199.

- Turnley, W. H., and M. C. Bolino. 2001. “Achieving Desired Images While Avoiding Undesired Images: Exploring the Role of Self-Monitoring in Impression Management.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (2): 351–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.351.

- Uranowitz, S. W., and K. O. Doyle. 1978. “Being Liked and Teaching: The Effects and Bases of Personal Likability in College Instruction.” Research in Higher Education 9 (1): 15–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00979185.

- Uttl, B., C. A. White, and D. W. Gonzalez. 2017. “Meta-Analysis of Faculty’s Teaching Effectiveness: Student Evaluation of Teaching Ratings and Student Learning Are Not Related.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 54: 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007.

- Veletsianos, G. 2012. “Higher Education Scholars’ Participation and Practices on Twitter.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 28 (4): 336–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00449.x.

- Wayne, S. J., and G. R. Ferris. 1990. “Influence Tactics, Affect, and Exchange Quality in Supervisor–Subordinate Interactions: A Laboratory Experiment and Field Study.” Journal of Applied Psychology 75 (5): 487–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.487.

- Wayne, S. J., and R. C. Liden. 1995. “Effects of Impression Management on Performance Ratings: A Longitudinal Study.” Academy of Management Journal 38 (1): 232–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/256734.

- West, B. T., K. B. Welch, and A. T. Galecki. 2014. Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Widmeyer, W. N., and J. W. Loy. 1988. “When You’re Hot, You’re Hot! Warm–Cold Effects in First Impressions of Persons and Teaching Effectiveness.” Journal of Educational Psychology 80 (1): 118–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.1.118.

- Wookey, M. L., N. A. Graves, and J. C. Butler. 2009. “Effects of a Sexy Appearance on Perceived Competence of Women.” The Journal of Social Psychology 149 (1): 116–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.1.116-118.

Appendix 1

Measurements of constructs.