Abstract

This article explores peer review through the lens of internal feedback. It investigates the internal feedback that students generate when they compare their work with the work of peers and with comments received from peers. Inner feedback was made explicit by having students write an account of what they were learning from making these different comparisons. This allowed evaluation of the extent to which students’ self-generated feedback comments would match the feedback comments a teacher might provide, and exploration of other variables hypothesized to influence inner feedback generation. Analysis revealed that students’ self-generated feedback became more elaborate from one comparison to the next and that this, and multiple simultaneous comparisons, resulted in students’ generating feedback that not only matched the teacher’s feedback but surpassed it in powerful and productive ways. Comparisons against received peer comments added little to the feedback students had already generated from comparisons against peer works. The implications are that having students make explicit the internal feedback they generate not only helps them build their metacognitive knowledge and self-regulatory abilities but can also decrease teacher workload in providing comments.

Introduction

Giving feedback to students on their work is time consuming for academic staff and it often does not result in significant learning (Price et al. Citation2010). Some students do not engage deeply with the comments they receive from teachers (Winstone et al. Citation2017). Others are unable to fully make sense of them or have difficulty translating them into actions for improvement (Higgins, Hartley, and Skelton Citation2001; Boud and Molloy Citation2013). Hence many researchers advocate peer review as an alternative to, or as a complementary method alongside, teacher comments (Nicol Citation2013; Mulder et al. Citation2014: Carless and Boud Citation2018). In peer review, students review and provide feedback comments on the work of their peers and then receive feedback comments on their own work from peers. This method is seen as a means of increasing students’ engagement with feedback processes and of improving learning without increasing the teacher burden in providing comments (Mulder et al. Citation2014; Gaynor Citation2020). Researchers also maintain that engagement in peer review helps develop in students the capacity to evaluate and regulate their own learning (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Sadler Citation2010; Evans Citation2013).

Despite considerable research evidencing students’ learning from peer review (see Huisman et al. Citation2019 for meta-review) little is known about how each component of this method (i.e. reviewing and receipt of comment) contributes to that learning, or about how that learning matches what students learn from teacher comments. One reason for this gap in research is a lack of clarity regarding the feedback mechanism that fuels learning from reviewing. This gap is addressed in this article by drawing on Nicol’s recent conceptual reframing of feedback and by using it to investigate a peer review implementation where there is no teacher input (Nicol Citation2019; Nicol Citation2020; Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014). In this reframing, feedback is seen as an internal process that students activate when they compare their work against some external information. Using this internal feedback lens, this article provides new insights into students’ learning from the different activities that comprise peer review and suggests ways in which practitioners might leverage more effective learning from peer review implementations without increasing their own feedback workload.

Literature review

Peer review research

While there is a long history of research showing that the receipt of feedback from peers results in learning benefits (Topping Citation1998; Falchikov Citation2005), it is only in the last 10–15 years that researchers have begun to tease apart and investigate the important role that the reviewing component of peer review plays in learning. This research shows that in terms of performance improvements, students learn as much or more from reviewing and providing feedback on the work of peers than from receiving feedback comments from peers (Lundstrom and Baker Citation2009; Li, Liu, and Steckelberg Citation2010: Cho and Cho Citation2011; Patchan and Schunn Citation2015; Huisman et al. Citation2018). Students also often perceive reviewing and giving feedback as more beneficial for their learning than receiving feedback, although this depends on many factors one of which is from whom they receive feedback (Gaynor Citation2020).

Despite the positive results from learning outcome and perception studies little is known about how students actually learn from reviewing the work of their peers. Even less is known about how this learning compares with what they learn from receiving teacher comments. In a meta-review, Huisman et al. (Citation2019) found only three studies which compared students’ learning during peer review with their learning from receiving feedback from teaching staff. However, the direction of the effects was mixed across these studies. More importantly, a major limitation was that these studies did not disentangle learning through reviewing from learning through receipt of peer comments.

Conceptions of feedback and learning from reviewing

While conceptions of feedback have shifted in recent years from a transmission view to one that recognizes the role and agency of the learner in processing received information (Boud and Molloy Citation2013), this conception is problematic with regard to peer review. While it fits the situation where students receive comments from peers, it does not easily explain how students learn from reviewing. How do students learn about their own work by giving feedback to others? Is the giving of feedback comments to others the causal mechanism behind learning from reviewing? Are the cognitive processes underpinning learning from reviewing the same or completely different from those involved in learning from receiving reviews? Most peer review researchers either do not distinguish these as different processes (Huisman et al. Citation2018), or they merely state that students learn more from ‘giving feedback’ than from ‘receiving feedback’ without further explanation (Gaynor Citation2020). A few however do provide a theoretical interpretation.

One interpretation is that reviewing engages students in problem-solving in relation to the peer’s work – in weakness detection, diagnosis and solution formulation - which they then apply to their own work (Cho and Cho Citation2011; Cho and MacArthur Citation2011; Snowball and Mostert Citation2013). Another interpretation is that reviewers take a reader perspective when they evaluate peers’ work, and that this allows them to re-evaluate their own work from a more detached reader perspective (Cho and Cho Citation2011). Still another position is that the requirement to write a feedback response for peers, causes students to revisit and rehearse their own thinking about the topic and build new understandings about it (Roscoe and Chi Citation2008).

Reviewing and receipt and internal feedback generation

Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) offer a simpler explanation of learning from reviewing, an explanation that has wider explanatory power beyond peer review. In their peer review study, they asked engineering students to explain the mental processes they engaged in during reviewing. Most reported that as they were reviewing the work of a peer, they compared that work with their own, and out of that comparison they generated ideas about the content, approach, weaknesses and strengths in their own work and about how to improve it. Many students actually used the word comparison or a phrase with that meaning. This finding has been reported elsewhere (McConlogue Citation2015: Li and Grion Citation2019).

Nicol (Citation2018, Citation2019) refers to the ideas (i.e. new knowledge) that students generate from making comparisons as internal feedback, an interpretation that informs the research here. What triggers internal feedback during reviewing is that students have produced similar work themselves in the same topic domain beforehand (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014: Nicol Citation2014). In effect, the comparison processes in reviewing are spontaneous and inevitable. Writing comments for peers is not what generates internal feedback. Rather, writing merely intensifies the comparison process and in turn the internal feedback that students generate from it (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014; van Popta et al. Citation2017; Peters, Körndle, and Narciss Citation2018). From this perspective, problem detection, alternative reader perspectives and elaborating prior understandings through writing comments for peers – the interpretations offered by other researchers to explain students’ learning from reviewing – are all dependent on prior comparison processes, on students detecting similarities and differences between their own work and that of peers.

Comparison underpins all feedback processes

More recently, Nicol (Citation2020) has proposed that students not only learn from reviewing, by comparing their own work with that of their peers and by generating internal feedback from those comparisons, but that all feedback is internally generated in this way (see also, Nicol and Selvaretnam Citation2021). The following is Nicol’s (Citation2020) definition of internal feedback which underpins this article.

Internal feedback is the new knowledge that students generate when they compare their current knowledge and competence with some reference information (p2).

Note that inner or internal feedback is not a product or output; rather it is a process of change in knowledge - conceptual, procedural or metacognitive knowledge.

Even when students receive feedback information from a teacher or a peer, if it is to have an impact on learning, students must compare that information with the work they have produced and generate new knowledge (i.e. inner feedback) out of that comparison. Teachers or peers only provide information, it is students who generate feedback: it is this change in knowledge and understanding that is the catalyst for students’ regulation of their own performance and learning (Butler and Winne Citation1995; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006). Similar feedback models have been proposed before, although these researchers identified the mechanism for internal feedback generation as monitoring rather than comparison (Butler and Winne Citation1995; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Panadero, Lipnevich, and Broadbent Citation2019), and have mostly focused on comments as the comparator.

Taking this inner feedback view, an important difference between reviewing and receipt of comments is in the nature of the information which is used for comparison. During reviewing students compare their own work against concrete examples of similar works. In contrast, the receipt of comments involves them in comparing their own work against a textual description of what is good or deficient in their work or about how that work might be improved. This difference in comparison information, arguably, at least in part, helps explain the finding that students learn different things from reviewing than from receiving comments (Sadler Citation2010: Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014: van Popta et al. Citation2017).

Making the results of feedback comparisons explicit

The main problem with viewing peer review through an internal feedback lens is the absence of any empirical data regarding what new knowledge students actually generate from the comparisons they make. Existing research on peer review has to date involved outcome (e.g. Huisman et al. Citation2018) or perception studies (e.g. McConlogue Citation2015). In this study, therefore, a methodology was devised whereby what students generate from making comparisons - against the work of peers and comments from peers – was made explicit in writing. Specifically, students were asked to produce a written feedback commentary on their own learning from comparisons.

The purpose of making the results of inner feedback processes explicit was two-fold. First, in line with the argument that internal feedback is the catalyst for students’ self-regulation of learning, one intention was to increase the potency of these inner feedback processes. Considerable research on self-explanation and on metacognition shows that making the results of internal thinking processes explicit has beneficial effects on students’ learning. For example, Chiu and Chi (Citation2014) summarise evidence showing that having students verbally externalize their understanding as they read a conceptually complex text enables them to identify gaps in their own understanding which they then try to fill by themselves (see also, Tanner Citation2017; Bisra et al. Citation2018). A second reason for making the results of comparisons explicit in writing is that this enabled us to address some research questions with regard to peer review that had not been addressed before.

Research questions

Prior research provides indirect evidence that students can generate productive internal feedback during the activities that comprise peer review, as demonstrated through learning gains (e.g. Lundstrom and Baker Citation2009; Cho and Cho Citation2011; Huisman et al. Citation2018). Yet it does not provide any evidence about what students generate from these activities, nor about how this compares with the comments a teacher might provide. In terms of reducing the burden on teachers in providing comments this represents a significant gap in pedagogical knowledge. By having students make the results of their internal feedback processes explicit in writing, we were able to address this gap. Hence the first research question was:

RQ 1: How do the feedback comments that students generate about their own work during their peer review activities compare against the feedback comments a teacher might provide?

Another issue concerns the number of comparisons students make during reviewing. In some studies, students have opportunities to compare their own work with the work of a number of peers, one after another (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014; McConlogue Citation2015; Purchase and Hamer Citation2018) while in others they compare their work against that of a single peer (Huisman et al. Citation2018). One logical prediction of the internal feedback model is that multiple sequential comparisons should generate more elaborate feedback than that deriving from a single comparison.

In addition to multiple sequential comparisons the students in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) maintained that during reviewing they made multiple simultaneous comparisons. They reported comparing one peer work against another and of using the ideas generated from one to think about and comment on the other, while still reflecting back on their own work. These researchers propose that such multiple simultaneous comparisons enable students to develop their own internal concept of quality. However, once again, these researchers did not provide actual data on the internal feedback students generated from their multiple simultaneous comparisons. Hence, the following constitutes research question 2:

RQ 2: What are the effects of multiple comparisons, sequential and simultaneous, on the feedback comments that students generate about their own work?

A related issue concerns the quality of the peer works against which students compare their own work (Patchan and Schunn Citation2015). In most peer review implementations, the works that students review are randomly assigned from within the class cohort. Hence the quality of the works they use for comparison is usually unknown. Yet, some researchers maintain that students will only learn from reviewing works of a high quality, or of a higher quality than their own (Grainger, Heck, and Carey Citation2018). Others argue that students need to review a variety of works of different quality, good and poor, so that they learn about the quality continuum and where their own work sits within that continuum (Sadler Citation2010). Hence research question 3:

RQ 3: Does the quality of the works reviewed influence the feedback comments that students generate about their own work?

Some studies of peer review show that, in terms of writing performance, students learn both from reviewing the work of peers and from receiving reviews from peers (e.g. Huisman et al. Citation2018), while other studies show they learn more from reviewing (Çevik Citation2015). Perception studies show that students often perceive each process as differentially beneficial (e.g. Ludemann and McMakin Citation2014). For example, when Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) asked students what they learned from reviewing, students reported that comparing their work with their peers’ work helped them view their own work from a new perspective and to discover different ways that they might approach that work. Others reported that reviewing helped them appreciate what might constitute quality or standards in terms of the work they were producing. In contrast, from receiving peer comments their main perception was that this resulted in their learning about errors, deficiencies or gaps in their work.

A confounding factor, however, in most peer review studies is that reviewing always precedes receipt of feedback; that is, comparisons against other similar works precede comparisons against comments. This ordering makes it difficult to tease apart these different feedback effects. Given this methodological difficulty, this study did not directly compare the feedback comments that students generate from reviewing versus receipt, but rather tried to ascertain the added value of receipt of comments, as per research question 4:

RQ 4: What does the feedback that students generate from received comments add to the feedback they generate about their own work from reviewing peer works?

Method

Participants

This study involved 139 students enrolled in an introductory first-year undergraduate course in Financial Accounting at a UK university. However, the data analysis was based on a sample of 41 students, which included students from a range of ability levels. This sample was determined by ethical consent, by the completeness of each student’s dataset and by the workload implications of analysing a large body of qualitative data. Ethical approval to carry out this study was provided by the University College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Research Involving Human Subjects [reference number 400170027].

Procedure

Essay task and orientation

The focus for peer review and the self-review activities was a 500-word academic essay. Before writing this essay, students participated in an orientation task. In tutorials, working in small groups, they examined a selection of four past student essays on a topic different from the one used in this study, discussed them, and identified the criteria for a good essay. The teacher then collated the criteria outputs from across all the tutorials and created a framework comprising four broad criteria headings with explanatory detail. The headings were: (i) answers the question; (ii) has a convincing argument; (iii) is well structured; and (iv) uses appropriate referencing and writing style. Students used these criteria when reviewing their peers’ work. This orientation task is known to improve students understanding of assignment requirements and hence the quality of what they produce (Rust, Price, and O’Donovan Citation2003). After the orientation, students read an academic journal article and wrote their 500-word essay.

Sequence of peer and self-reviews

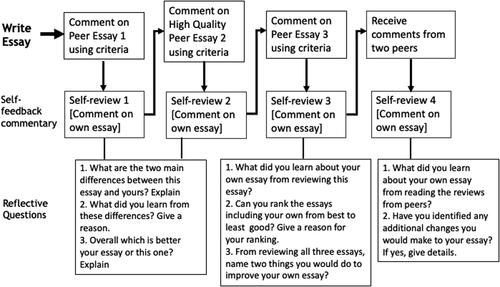

After submitting their essay, students completed three peer reviews each followed by a self-review (see ). Peer-review required that students compare each peer essay against each of the four criteria and write comments for that peer. Self-review required that students write comments about their own essay in response to some reflective questions (see ). Two of the three essays that were reviewed, the first and the third, were written by fellow classmates, whereas the second essay was a high-quality essay produced by a student the year before. The inclusion of this second essay ensured all students compared at least one high-quality essay with their own. Students were not informed at the time of reviewing that this essay was not written by a classmate.

Figure 1. Sequence of peer review and self-review activities and questions used to elicit feedback commentary.

After students had received feedback from two peers, they engaged in a fourth self-review by answering another two questions (self-review 4). All peer review and self-review activities were completed online using AROPA software. This software manages the anonymous distribution of essays for review and the return of feedback reviews to students. Other software tools support similar functions, for example, the Workshop tool in Moodle or the Self and Peer Assessment tool in Blackboard.

Questions used to elicit internal feedback

The self-review questions, shown in , framed students’ self-generated feedback commentaries. Essentially these questions were scripts that called on students to make the comparisons that students had already reported spontaneously making in earlier studies. For example, in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) students reported that during reviewing they learned by comparing their work against that of each peer, so in this study one question asked students to write out how their work differed from their peer’s work and the next asked them to write down what they learned from these differences. The self-review questions after peer review 1 and 2 were identical. In self-review 3 students were asked to make multiple simultaneous comparisons, that is to rank all essays including their own from best to least good and to give a reason for their ranking. Again, this was intended to make explicit a comparison that some students had spontaneously reported making in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014). Similar self-review questions were given to students after receiving comments from peers, with the same requirement for a written response. This ensured parity of engagement by students after reviewing and after receipt of comments from peers.

The teacher did not provide students with any feedback on their essays or their reviewing activities. Hence, if this had been a teaching intervention, it would not have incurred extra teacher workload in commenting. The main burden would be in setting up the AROPA software. However, in order to address the research questions, the second author did grade and write feedback comments on the essays that students wrote following exactly the same pattern that she had followed in the past for this essay task.

Survey and focus groups

As part of a wider evaluation of the course all students answered a short survey, and seven students took part in two focus group sessions. In this article, some reference is made to the results of this evaluation data where it helps elaborate the findings.

Data analysis

The students’ self-reviews, that is their written self-feedback commentaries, were the main data used for analysis. These commentaries were first coded in terms of the extent to which the comment segments matched the comments that the teacher wrote. The teacher’s comments were framed by the assessment criteria. Where the student’s commentary went beyond the teacher’s comments it was first coded in terms of the criteria to ascertain its added value on that basis (e.g. was it more detailed), and then the comments that remained were coded in terms of the themes that emerged. Reference to earlier studies and in particular to students’ perceptions of their learning from reviewing in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) influenced the latter coding. Coding was done by both researchers independently and any discrepancies discussed, and a resolution agreed. Initial coding before discussion of any issues achieved 95% agreement.

Results and interpretation

Teacher feedback versus student-generated feedback [RQ1]

shows the results of a comparison of students’ self-feedback commentaries with the feedback the teacher wrote. Specifically, teacher comments were compared with students’ written responses to self-review 1, then with self-review 1 and 2 combined, and so on. From this analysis, the self-review stage at which students’ commentary fully matched the areas for improvement identified by the teacher’s comments could be ascertained.

Table 1. Number of self-reviews (comparisons) required for students’ feedback commentary to match teacher feedback comments.

From it can be seen that almost all students (37/41), regardless of ability level, identified the areas for improvement that the teacher identified. As the teacher comments were referenced back to the criteria, this meant that the students’ self-review comments covered the same essay criteria. also shows that the stage at which the match with teacher feedback occurred differed across students: that is 7 students (17%) matched teacher comments after self-review 1, 19 (46%) after self-review 2 and 27 (66%) after self-review 3. Importantly, only 10 students (24%) had to compare their essay against received peer comments (self-review 4) to fully identify the areas for improvement noted by the teacher. Of the four students (10%) who did not make a complete match with teacher comments, three missed a specific point about the argument in their essay that the teacher noted, and one missed a point about referencing.

Going beyond teacher feedback

Although shows the stage in the sequence of self-reviews at which the students’ feedback matched teacher feedback, all students generated more feedback comments than the teacher. Combining the four comparisons (i.e. four self-reviews), students generated between 2.5 and 12 times more written feedback comments than the teacher wrote. This extra feedback was classified in two ways, feedback still framed in relation to the criteria but more elaborate than what the teacher produced, and feedback that was more holistic and not specifically identifiable as related to the criteria and that was of a type that the teacher did not produce.

shows the extra feedback that students produced where it was aligned to the criteria. It shows: (i) when this extra feedback was generated, either during self-reviews 1–3 (during comparisons against other peer essays) or during self-review 4 (during comparison against comments); (ii) how many categories of extra feedback were generated (1, 2 or 3 categories); and (iii) the distribution of extra feedback in relation to the quality of the students’ submitted essay (graded A, B or C). The latter is a proxy for student ability.

Table 2. Feedback that students generated beyond what the teacher identified in relation to the criteria.

To clarify, in one case, the teacher identified an issue with the logical structure of the essay whereas the student specified what the problem was in more detail (e.g. by relating it to her paragraph structure and the sequencing of paragraphs). This was categorized as more detail. Another category was additional feedback issue where a student generated feedback on an issue not mentioned by the teacher. For example, one student produced a good argument and hence the teacher did not comment on this while the student did, making comments about its weaknesses. The third category was additional action point which means that the student proposed an action for improvement of their work that the teacher did not identify. Some students identified one category of extra feedback, others two, and still others three categories.

This analysis shows that almost all of the extra feedback was generated by students from comparing their own essay with other essays (i.e. during self-review 1–3) rather than comparing against comments (self-review 4). Overall, 38 students out of 41 produced extra feedback in relation to the criteria. Students who produced a C-grade essay mostly identified a single extra feedback issue or elaboration rather than multiple extra feedback issues. It is important to note however, that students who wrote a C-grade essay and who matched the teacher feedback had already generated a great deal of feedback as they would have required much more self-identification of issues to match the teacher comments.

shows the extra feedback that students generated where it was not directly tied to the criteria, and that was of a type that the teacher did not provide. Three main categories of this kind of extra feedback were identified, feedback of a motivational nature (e.g. I learned that I must have written quite a good essay as I feel a similarity with this essay and my own), feedback about the students’ own essay framed from a reader perspective (e.g. my essay could do with a clearer introduction so that the reader will know what the essay will include) and feedback about different approaches they could take to essay writing (e.g. the difference in structure gave me an alternative approach to consider when laying out my essay). It is notable again, that most of this extra feedback was generated when students compared their essay against other essays rather than against comments from peers. The exception was motivational feedback which was generated by 17 students during self-review 1–3 and by 11 students during self-review 4. Also notable is that 32 out of the 41 students (78%) generated extra feedback of this more holistic nature. Finally, combining data across and it should be noted that all students, without exception, generated additional feedback of some kind over and above what the teacher wrote.

Table 3. Feedback that students generated beyond what the teacher identified that was not linked to the criteria.

Multiple comparisons and student-generated feedback [RQ2]

Multiple sequential comparisons

From the data in it is clear that most students had to make multiple sequential comparisons to match teacher feedback, and that this matching mostly derived from students’ comparisons of their own essay with other essays rather than with comments. Furthermore, an analysis of the data (before it was collated into and ) also showed that the extra feedback that students generated unfolded over sequential comparisons. Again, this extra feedback mainly derived from comparisons against peer essays rather than against comments.

Multiple simultaneous comparisons

During self-review 3, students were required to make a multiple simultaneous comparison. They had to rank order all the essays they had reviewed, including their own, from good to least good and to provide reasons for their ranking. Of the 38 students who provided this ranking not all ranked with accuracy. However, most (32/38) correctly ranked all essays with the exception of their own. In other words, the main difficulty students had was in judging the relative quality of their own essay in the set being ranked.

The reasons that students gave for their ranking decisions reveals the nature of the feedback that such multiple simultaneous comparisons generate. Thirty-seven students provided a reason and most (26/37) implicitly generated what might be referred to as a ‘rubric’. These students first identified the best essay and wrote what was good about it in relation to one or more criteria, and then they commented, one by one, on how each subsequent essay was less good. We refer to this as a rubric because the differences across essays were always framed in terms of the essay marking criteria. Some students provided considerable detail (e.g. a half-page of text) in their responses, with a few sentences of explanation given for each essay position, while other students were briefer in their rationalizations. The following is one less detailed example.

I would rank the essays in this order as I think the second essay had a very clear train of thought, valid arguments, good referencing and also a clear structure. The first essay was also very good: however, I felt that the difference was in tone as I feel the second essay had a more formal tone than the first one. I would rank mine next as I think my structure was better than the third one and has a slightly more formal style. [student’s ranking: essay 2: essay 1, mine, essay 3]

A number of students (5/37) explained their ranking decisions in relation to a smaller number of high-level criteria that they saw as cutting across all four essays.

I would say that argument development made a difference in this ordering particularly between mine and essay 2. Also, writing style, language and grammar made a difference to the ordering. [student’s ranking: essay 2, essay 1, mine, essay 3]

Five students, even though they did rank, wrote about the characteristics of the better essay and compared this with one other essay but did not mention all the essays. One student just wrote down what criteria had informed her ranking without connecting this to the essays being ranked. All the feedback students generated during this ranking process was valid in terms of the identification of what made for a good quality essay, even when their actual rankings were inaccurate. Inaccuracy in rankings appeared to be the result of students focusing on specific features (i.e. criteria) in others’ essays relative to their own rather than on making a holistic comparison.

Quality of the comparators and student-generated feedback [RQ3]

Given the pattern of the data in we can infer that students generate productive feedback from each review, regardless of the quality of the essay they compared their own against. However, to gain a deeper insight into how the quality of the comparator influenced students’ feedback generation, we carried out further analysis of the data from a subset of students, namely, those who had produced a B-grade essay and who had first reviewed a C-grade essay then an A-grade essay. There were ten such students. The analysis involved comparing the feedback they generated in self-review 1 (comparison against C-grade essay) with the feedback they generated in self-review 2 (comparison against A-grade essay). Since these students always compared their own essay against the lower quality essay first, there was no contamination from a prior high-quality comparison on the feedback they generated from the lower-quality comparison.

The results of this analysis showed that all ten students generated productive feedback regardless of the quality of the peer’s essay. It did however reveal some differences in the nature of the feedback they generated depending on the comparator. When students compared their essay against a lower quality essay, they were more likely to write about the strengths in their own essay or about weaknesses to avoid in future essays. When they compared their essay against a higher quality essay, they were more likely to write about how they could improve their own essay.

In the survey and focus groups, students gave reasons as to why a low-quality essay might be valuable. Some noted that a weak essay might not be weak in every respect. Others noted, consistent with the analysis of the feedback commentaries of the ten students, that scrutinizing a weak essay alerts you to things you should avoid in your own essay in the future. Still others noted that sometimes a really good work is ‘too far removed from where you are’ and hence it is harder to learn from that than from a work that is weaker and hence closer in quality to your own. All students in the focus groups however agreed that the inclusion of a high-quality example was necessary if they were to make improvements in their work.

Student-generated feedback: peer essays versus peer comments [RQ4]

and show that most extra feedback, beyond that provided by the teacher, was, to a large extent, apart from motivational feedback, generated by students during essay comparisons rather than the peer comments comparison.

To ascertain the extent to which the student’s comparison of their own essay against received comments added value over and above the comparisons they had already made against other essays, an analysis was carried out comparing all the self-feedback they generated during self-review 1–3 with what they generated during self-review 4. This revealed that while 24 students generated self-feedback over and above that which they generated during self-review 1–3, only two students added something completely new at self-review 4. The rest of their comments only added something minor to what students had already generated during self-reviews 1–3, usually a minor elaboration of, or comment on an area already identified (e.g. introduce paragraph breaks; improve conclusion; improve referencing; minor tone and wording points).

An example of one student’s self-feedback commentary

Appendix 1 provides a complete example of one student’s feedback commentary as it unfolded over the four self-reviews. This feedback narrative brings to life the meaning behind the data analysis. It highlights both the student’s own feedback capability and the methodological value of having them make explicit the results of their self-generated feedback in writing. The authors also provide a brief interpretation of this commentary as it relates to the arguments in this article.

Discussion

This study shows that students, regardless of ability level, are able to generate high-quality feedback on their own without any teacher feedback input. Students generated more detail and more feedback issues than the teacher with many also generating feedback of a type that the teacher did not produce, in particular, motivational and reader perspective feedback and feedback about alternative approaches they could take to their work.

However, in order to match teacher feedback, and especially to generate extra and alternative feedback, students had to make multiple sequential comparisons. This investigation shows that feedback builds up and becomes more elaborate from one comparison to the next. Hence, in planning peer review implementations, practitioners must go beyond the single comparisons that seem to dominate peer review research (e.g. Huisman et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, students should also be asked to make multiple simultaneous comparisons as this resulted in students generating feedback of a type that even a conscientious teacher might have difficulty providing, namely, high-level feedback about where their own essay sits in relation to a set of similar essays of different quality.

Students generated productive feedback both when comparing their essay with essays that were of a lower quality than their own, as well as with those of a higher quality, although analysis suggested that they learn something different from these different comparisons. This finding concurs with Sadler’s (Citation2010) view that to understand what constitutes quality one needs to appreciate both what good and poor-quality looks like. However, as the sample size for this aspect of the investigation was small there is a need for further research on the effects of comparator quality on feedback generation. For now, based on their internal feedback commentaries and students’ self-reports in the survey and focus groups, the main recommendation is that those designing peer review studies should include at least one high-quality work in the range of works being compared, so as to ensure that all students have at least one benchmark for comparison. This is an overlooked issue in many feedback studies as when the works students produce are randomly assigned by software some students may not receive any work of high-quality.

Teacher comments versus self-generated feedback

In this investigation, students were not asked to compare teacher comments against their own work. Hence, we do not know what feedback students would have generated from comparisons against those comments. Also, it is not surprising that students generated more comments than the teacher wrote, as given that they are the agents of their own learning, they will always generate insights that a teacher could not provide. One could also argue that the results of this study would have been quite different had the teacher merely spent more time writing comments. For these reasons, we should not jump to the conclusion that teacher comments are in some way sub-standard.

Yet there are limits to how far one might push these arguments. First, students’ self-generated feedback differed from teacher feedback across a number of dimensions (reader response, alternative perspectives, relational quality of different essays). Hence increasing teacher feedback would not necessarily mean inclusion of these other dimensions, especially given that these dimensions seemed to derive from students comparing their work against similar works rather than against comments from peers. Second, the feedback students generated during self-review 1–3 was formulated in relation to their own self-determined needs and was not capped by the criteria. Even the best students generated considerable self-feedback. As writing feedback comments is time-consuming, teachers usually prioritize, by commenting on work that does not meet the criteria or standards rather than commenting under every criterion in every student’s work. In contrast there is no such ceiling on students’ self-generated feedback. Third, even if a teacher gives students comments that match the comments that students might self-generate from other information sources there would be no guarantee that students would interpret them as intended, or be able to make productive comparisons of them against their own essays. Indeed, there is a great deal of research about the difficulties that students have in interpreting teacher feedback comments (Price et al. Citation2010; Orsmond and Merry Citation2011). These difficulties don’t apply to self-generated comments.

Nonetheless, the argument here is not that teacher feedback is not needed or valuable, only that there is significant merit in having students generate as much feedback as they can themselves using other reference comparators before receiving teacher comments (Nicol, Serbati, and Tracchi Citation2019, Nicol Citation2020). Taking this approach not only prioritizes the development of learner self-regulation, and attenuates teacher dominance, but also opens up the possibility of both reductions in and better targeted teacher feedback, as well as greater receptivity to it by students when it is received. For example, students would likely derive more from teacher feedback if they had already generated some themselves beforehand from other comparisons.

The question of quality and standards

One concern that teachers might have with regard to self-generated feedback during peer review is that it might not inform students about how to improve the quality of their own work as judged in relation to externally defined standards. This was tackled in this implementation by the insertion of a high-quality essay into the set to be reviewed. The requirement that students both judge whether their own essay was of a higher or lower quality than the one they were reviewing (in self-review 1 and 2) and to make comparisons across all the essays (self-review 3) was also intended to raise students’ awareness about essay quality. Prior research has shown that when students review the work of peers and comment on it against criteria this raises their own awareness about how those criteria relate to their own work (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014; To and Panadero Citation2019). It also shows that engaging students in peer review does result in grade improvements, another indicator that this method raises standards (Huisman et al. Citation2019). Taking a wider view, ensuring that students acquire a conception of standards is not just an issue in peer review, it is also an issue with regards to teacher feedback comments. It is far from clear how the inner feedback that students generate from teacher comments actually helps them grasp what constitutes an acceptable standard of quality.

Self-generated feedback and impact

Another concern is that while students generated feedback on their essays, they did not have an opportunity to update and improve those essays based on that feedback. Some researchers claim that the only real proof of learning from feedback processes is evidence of a performance impact (Boud and Molloy Citation2013). In response, it could be argued that providing a commentary on one’s own work is a form of action. Also, students are more likely to act on feedback that they have deliberately spent time writing out than that which they generate from reading comments, which they might have trouble interpreting. Nonetheless, as this study was not designed to collect impact data, there is a need to address this issue directly. In that regard, we have investigated this in a follow-up study. Initial findings show that 70% of students achieved a higher grade, from comparing peer essays with their own, in a draft-redraft scenario without any teacher input, and indeed without the receipt of any comments from peers.

Peer comments and feedback generation

In this investigation, comparisons against peer comments contributed little to the generation of additional feedback beyond the comments the teacher wrote. This finding is consistent with research which shows that students learn more from reviewing than receipt of comments when the metric for learning is either performance improvements or student self-reports (Cho and Cho Citation2011; Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014). It is also consistent with arguments of Sadler (Citation2010) that comparing your work against actual works is more powerful than comparing against comments, as words cannot really convey what quality is or how to produce it. Student self-reports also show that a key benefit of having them compare their work with other works is that they envisage different ways of improving their work and different perspectives they could take to their work (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014; McConlogue Citation2015; Li and Grion Citation2019). The results of this investigation were consistent with that research in that feedback of these types was evident only during self-reviews 1–3.

Nevertheless, that students learned so little from comparisons with received comments was surprising in relation to other published studies (Cho and MacArthur Citation2010; Huisman et al. Citation2018: Nicol, Serbati, and Tracchi Citation2019) and must be interpreted with caution. First, in this study, as in almost all peer review implementations, reviewing preceded receipt of comments. Hence the advantage of reviewing over receipt might be accounted for by this sequence, and especially given that the number of comparisons students made before receipt was more in this study than in most other peer review studies. Second, despite the data showing very little learning from receipt of comments many students in the survey and focus groups, as in other studies, reported that they did learn from comparisons with received comments (e.g. Mulder, Pearce, et al. Citation2014). Hence controlled studies are needed to properly disentangle the feedback that students generate from similar works versus comments comparisons. However, this study also suggests a need for much greater caution about taking students’ reports of their perceptions of learning at face value, as these might not be congruent with the actual learning that results from different feedback comparisons.

Generalizability to other disciplines and contexts

The participants in this study were first-year students studying Accountancy and Finance and they generated feedback in relation to an essay task. There is therefore a need to investigate these methods and the feedback students generate in other disciplinary contexts, in other years of study and with other assignment types. However, that these students in the first semester of the first year were able to produce feedback at this level and of this quality is very promising. It begs the question: What will they be able to produce in later years if these methods become an integral part of the curriculum?

Making natural comparisons explicit

The unique feature of this investigation was that we built on the natural comparison processes that students reported engaging in in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014) by making them deliberate and the outputs of them explicit in writing. Making the outputs of comparison processes explicit in this way will very certainly have increased the quality of the feedback that students’ self-generated. Research on self-explanations and metacognition provides strong support for this assertion (Fonseca and Chi Citation2011; Tanner Citation2017; Bisra et al. Citation2018). Yet, a controlled study comparing natural feedback comparisons against deliberate and explicit comparisons would move this research forward. Nicol (Citation2020) makes a case that explicitness is the key to unlocking the power of internal feedback in all feedback settings. Given this argument, there is a considerable scope to revisit many prior published peer review studies and to implement them again but this time making implicit feedback processes explicit. This would not only provide deeper insight into students’ learning from different peer review interventions but would also help us ascertain what conditions maximise that learning.

This methodology of making comparisons explicit shifts the balance in peer review away from students’ commenting on others’ work to reviewing their own work. This is a fundamental shift as most studies of peer review assume that the comments that students produce about other’s work (e.g. Patchan and Schunn Citation2015) are a proxy for the quality of the students’ own learning. Yet in our follow-up peer review implementation we did not ask students to comment on their peers’ essay. They only used their peers’ essays as comparators to self-review and comment on their own work, and as noted earlier 70% of the students still made performance improvements from draft to redraft. Hence, while providing comments for peers might add value and will help students develop important graduate skills, eliminating this aspect might at times also have merit. Specifically, it would help address the main concern that students have about peer review, the negative emotional impact of receiving or giving peer comments (Kaufman and Schunn Citation2011).

Conclusion

This study suggests that there would also be considerable merit in making explicit the internal feedback that students generate from comparing their work against the comments they receive from teachers. Yet, while this would certainly ensure better engagement with teacher comments and improve learning impact, we should not lose sight of the wider benefit of having students make comparisons of their performance against information sources other than teacher comments, and even other than peer works or peer comments. As Nicol (Citation2020) proposes, we could ask students to make explicit comparisons of their work against information in a textbook or in a journal article or against a rubric or the assessment criteria or against a video of an expert discussing their thinking. Appendix 1 shows the immense power of this methodology in peer review, but it really needs to be applied more widely using many other resources. Doing so would not only help strengthen students’ own self-regulatory capability, and over the long term reduce their dependence on the teacher, but at the same time it would significantly reduce teacher workload in providing comments – a win-win situation for both students and teachers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Lee Parker for his feedback on an early draft of this article and to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the submitted version.

References

- Bisra, Kiran, Qing Liu, John C. Nesbit, Farimah Salimi, and Philip H. Winne. 2018. “Inducing Self-Explanation: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 30 (3): 703–725. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9434-x.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013. “Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 698–712. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

- Butler, D. L., and P. H. Winne. 1995. “Feedback and Self-Regulated Learning: A Theoretical Synthesis.” Review of Educational Research 65 (3): 245–281. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543065003245.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Çevik, Y. D. 2015. “Assessor or Assessee? Investigating the Differential Effects of Online Peer Assessment Roles in the Development of Students’ Problem-Solving Skills.” Computers in Human Behavior 52: 250–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.056.

- Chiu, J. L., and M. T. H. Chi. 2014. “Supporting Self-Explanation in the Classroom.” In Applying Science of Learning in Education: Infusing Psychological Science into the Curriculum , edited byV. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson and C. M. Hakala, 91–103. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-44868-008.

- Cho, Y. H., and K. Cho. 2011. “Peer Reviewers Learn from Giving Comments.” Instructional Science 39 (5): 629–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9146-1.

- Cho, K., and C. MacArthur. 2010. “Student Revision with Peer and Expert Reviewing.” Learning and Instruction 20 (4): 328–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.006.

- Cho, K., and C. MacArthur. 2011. “Learning by Reviewing.” Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (1): 73–84. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021950.

- Evans, C. 2013. “Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education.” Review of Educational Research 83 (1): 70–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312474350.

- Falchikov, N. 2005. Improving Assessment through Student Involvement. London: Routledge-Falmer.

- Fonseca, B., and M. T. H. Chi. 2011. “The Self-Explanation Effect: A Constructive Learning Activity.” In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction edited by R. E. Mayer, and P. A. Alexander, 296–321. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- Gaynor, J. W. 2020. “Peer Review in the Classroom: Student Perceptions, Peer Feedback Quality and the Role of Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (5): 758–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1697424.

- Grainger, P. R., D. Heck, and M. D. Carey. 2018. “Are Assessment Exemplars Perceived to Support Self-Regulated Learning in Teacher Education?” Frontiers in Education 3: 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00060.

- Higgins, R., P. Hartley, and A. Skelton. 2001. “Getting the Message across: The Problem of Communicating Assessment Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 6 (2): 269–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510120045230.

- Huisman, B., N. Saab, P. van den Broek, and J. van Driel. 2019. “The Impact of Formative Peer Feedback on Higher Education Students’ Academic Writing: A Meta-Analysis.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (6): 863–880. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1545896.

- Huisman, B., N. Saab, J. van Driel, and P. van den Broek. 2018. “Peer Feedback on Academic Writing: Undergraduate Students’ Peer Feedback Role, Peer Feedback Perceptions and Essay Performance.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (6): 955–968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1424318.

- Kaufman, J., and C. Schunn. 2011. “Students’ Perceptions about Peer Assessment for Writing: Their Origin and Impact on Revision Work.” Instructional Science 39 (3): 387–406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23882808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9133-6.

- Li, L., and V. Grion. 2019. “The power of giving feedback and receiving feedback in peer assessment.” All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/413

- Li, Lan, Xiongyi Liu, and Allen L. Steckelberg. 2010. “Assessor or Assessee: How Student Learning Improves by Giving and Receiving Peer Feedback.” British Journal of Educational Technology 41 (3): 525–536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00968.x.

- Ludemann, Pamela M., and Deborah McMakin. 2014. “Perceived Helpfulness of Peer Editing Activities: First-Year Students’ Views and Writing Performance Outcomes.” Psychology Learning & Teaching 13 (2): 129–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2014.13.2.129.

- Lundstrom, K., and W. Baker. 2009. “To Give is Better than to Receive: The Benefits of Peer Review to the Reviewer’s Own Writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing 18 (1): 30–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002.

- McConlogue, T. 2015. “Making Judgements: Investigating the Process of Composing and Receiving Peer Feedback.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (9): 1495–1506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.868878.

- Mulder, R., C. Baik, R. Naylor, and J. Pearce. 2014. “How Does Student Peer Review Influence Perceptions, Engagement and Academic Outcomes? A Case Study.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (6): 657–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.860421.

- Mulder, R. A., J. M. Pearce, and C. Baik. 2014. “Peer Review in Higher Education: Student Perceptions before and after Participation.” Active Learning in Higher Education 15 (2): 157–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787414527391.

- Nicol, D. 2013. “Resituating Feedback from the Reactive to the Proactive.” In Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding It and Doing It Well, edited by D. Boud and E. Molloy, 34–49. Oxon: Routledge.

- Nicol, D. 2014. “Guiding Principles of Peer Review: Unlocking Learners’ Evaluative Skills.” In Advances and Innovations in University Assessment and Feedback edited by C. Kreber, C. Anderson, N. Entwistle and J. McArthur. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Nicol, D. 2018. “Unlocking Generative Feedback through Peer Reviewing.” In Assessment of Learning or Assessment for Learning: Towards a Culture of Sustainable Assessment in Higher Education, edited by V. Grion and A. Serbati. Pensa: Multimedia.

- Nicol, D. 2019. “Reconceptualising Feedback as an Internal Not an External Process.” Italian Journal of Educational Research Special Issue. 71–83. https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/sird/article/view/3270.

- Nicol, D. 2020. “The Power of Internal Feedback: Exploiting Natural Comparison Processes.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1823314.

- Nicol, D. J., and D. Macfarlane-Dick. 2006. “Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 199–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090.

- Nicol, D., A. Serbati, and M. Tracchi. 2019. “Competence Development and Portfolios: Promoting Reflection through Peer Review.” All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 11 (2):1–13. http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/405/664.

- Nicol, D., A. Thomson, and C. Breslin. 2014. “Rethinking Feedback Practices in Higher Education: A Peer Review Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (1): 102–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.795518.

- Nicol, D., and G. Selvaretnam. 2021. “Making Internal Feedback Explicit: Harnessing the comparisons students make during two-stage exams.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. .

- Orsmond, P., and S. Merry. 2011. “Feedback Alignment: Effective and Ineffective Links between Tutors’ and Students’ Understanding of Coursework Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (2): 125–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903201651.

- Panadero, E., A. Lipnevich, and J. Broadbent. 2019. “Turning Self-Assessment into Self-Feedback.” In The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education, edited by M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_9.

- Patchan, M. M., and C. D. Schunn. 2015. “Understanding the Benefits of Providing Peer Feedback: How Students Respond to Peers’ Texts of Varying Quality.” Instructional Science 43 (5): 591–614. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43575308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-015-9353-x.

- Peters, O., H. Körndle, and S. Narciss. 2018. “Effects of a Formative Assessment Script on How Vocational Students Generate Formative Feedback to a Peer’s or Their Own Performance.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 33 (1): 117–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0344-y.

- Price, M., K. Handley, J. Millar, and B. O’Donovan. 2010. “Feedback: All That Effort, but What is the Effect?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3): 277–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903541007.

- Purchase, H., and J. Hamer. 2018. “Peer-Review in Practice: Eight Years of Aropä.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (7): 1146–1165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1435776.

- Roscoe, R. D., and M. T. H. Chi. 2008. “Tutor Learning: The Role of Explaining and Responding to Questions.” Instructional Science 36 (4): 321–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9034-5.

- Rust, C., M. Price., and B. O’Donovan. 2003. “Improving Students Learning by Developing Their Understanding of Assessment Criteria and Processes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 28 (2): 147–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301671.

- Sadler, D. R. 2010. “Beyond Feedback: Developing Student Capability in Complex Appraisal.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (5): 535–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903541015.

- Snowball, J. D., and M. Mostert. 2013. “Dancing with the Devil: Formative Peer Assessment and Academic Performance.” Higher Education Research & Development 32 (4): 646–659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.705262.

- Tanner, K. D. 2017. “Promoting Student Metacognition.” CBE Life Sciences Education 11: 113–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033.

- To, J., and E. Panadero. 2019. “Peer Assessment Effects on the Self- Assessment Process of First-Year Undergraduates.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (6): 920–932. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1548559.

- Topping, K. 1998. “Peer Assessment between Students in Colleges and Universities.” Review of Educational Research 68 (3): 249–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068003249.

- van Popta, Esther, Marijke Kral, Gino Camp, Rob L. Martens, and P. Robert-Jan Simons. 2017. “Exploring the Value of Peer Feedback in Online Learning for the Provider.” Educational Research Review 20: 24–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.10.003.

- Winstone, N., R. A. Nash, J. Rowntree, and M. Parker. 2017. “It’d Be Useful, but I Wouldn’t Use It: Barriers to University Students’ Feedback Seeking and Recipience.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (11): 2026–2041. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032.

Appendix 1

This Appendix provides an example of a student’s self-generated feedback, showing how this unfolds over time based on her answers to the reflective questions shown in . In relation to the University of Glasgow’s grading-scale this student produced a B2-grade essay then compared her essay against an A4-grade, A3-grade (the inserted high-quality essay) and C2-grade essay. The final comparison was against comments received from two peers.

The comments the teacher wrote are also provided so readers can compare the students written feedback commentary against the comments the teacher wrote. Note these were not given to the student. The authors also provide their analysis of this student’s unfolding feedback commentary.