Abstract

Authentic assessment aligns higher education with the practices of students’ future professions, which are increasingly digitally mediated. However, previous frameworks for authentic assessment appear not to explicitly address how authenticity intersects with a broader digital world. This critical scoping review describes how the digital has been designed into authentic assessment in the higher education literature. Our findings imply that the digital was most often used to enhance assessment design and to develop students’ digital skills. Other purposes for designing the digital into assessment were less present. Only eight studies situated the students within the wider context of digital societies, and none of the studies addressed students’ critical digital literacies. Thus, while there are pockets of good practice found within the literature, the vast majority of the studies employed the digital as an instrumental tool for garnering efficiencies. We suggest that in order to fit its purpose of preparing students for the digital world, the digital needs to be designed into authentic assessment in meaningful ways.

Introduction

Higher education aims to provide meaningful, relevant courses, where graduates can learn to work and live in an increasingly digital society. The so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’ suggests a scale of change that is having enormous impact upon society, including professional labour. In addition, digital technologies such as smartphones have become entangled and constitutive with everyday life, so that all forms of work and life can be considered to take place within a digital world. The term ‘the digital’ refers to both a digital technology and a social practice: in the digital world we now live with technology rather than only use it (Bearman, Nieminen, and Ajjawi Citation2022). Thus, any authentic engagement with, or reflection of, professional workplaces should make reference to the digital in some form. This includes authentic assessment.

Authentic assessment, in its most practical conceptualisation, requires students to ‘use the same competencies, or combinations of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, that they need to apply in the criterion situation in professional life’ (Gulikers et al. Citation2004, 69). While it seems likely that the digital should be a key part of authentic assessment design, the digital aspects of authentic assessment have received surprisingly little elaboration and theorisation in the literature. The digital is not a part of Ashford-Rowe et al. (Citation2014) influential list of critical elements for authentic assessment; the literature review by Villarroel et al. (Citation2018) makes no references to ‘digital’ or to ‘technology’; and the digital is not within the six employability skills identified by Sokhanvar et al. (Citation2021) in the review. While ‘the digital’ is implicitly present in many studies concerning authentic assessment, minimal conceptualisation of how to purposefully design the digital into authentic assessment might hinder ‘the development of assessment designs relevant to a digital world’ (Bearman et al. Citation2022, 2).

This absence of consideration with respect to the digital is particularly surprising as authentic assessment is commonly defined by describing what makes a particular task authentic. This may be a consequence of its origins: authentic assessment was first connected with ‘real-life’ assessment tasks that asked primary school students to take part in authentic disciplinary practices, such as real methodologies used by scientists (Wiggins Citation1990; see McArthur Citation2022 for a brief history). Thus, authentic assessment is often considered a matter of design – both the design features and design conditions. For example, Gulikers et al. (Citation2004) report an influential five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment considering the assessment task, the physical context, the social context, the assessment result and the assessment criteria. Many other similar lists and typologies exist (e.g. Herrington and Herrington Citation1998; Schultz et al. Citation2022), perhaps most notably the eight critical elements of authentic assessment by Ashford-Rowe et al. (Citation2014) (challenge, product, transfer, metacognition, accuracy, fidelity, feedback, collaboration) and the three dimensions of authentic assessment by Villarroel et al. (Citation2018) (realism, cognitive challenge, evaluative judgement). There are multiple frameworks, models, checklists and definitions that work for different purposes. While we contend that a singular approach to authentic assessment design may not fit all the complex contexts of higher education, the general absence of reference to the digital is striking, particularly in later frameworks.

Despite this array of implementation-oriented frameworks, the higher education literature describes few deeper conceptualisations of authentic assessment: the field has largely relied on ‘a fairly disarticulated and ahistorical sense of authenticity’ (McArthur Citation2022, 2). There are some exceptions. Vu and Dall’Alba (Citation2014) draw on Heidegger to suggest a focus on students’ becoming their authentic selves through assessment in the complex world. McArthur (Citation2022) draws on Heidegger and Adorno to conceptualise ‘authentic assessment’ in terms of its interconnections with work and the surrounding society, and the capacity to transform societies. These conceptualisations, which emphasise authenticity as a means of relating to the broader world, imply that if the digital is part of the social world, then it must necessarily be a part of authentic assessment.

There thus remains a crucial gap in the literature describing how the digital and authentic assessment relate. This critical scoping review describes how the digital has been designed into authentic assessment in the higher education literature. By understanding how the research literature describes innovative authentic assessment designs, we may both create more meaningful assessment experiences for our students, as well as expand our notions of what authentic assessment design is or might be for the digital world.

Methods

Critical scoping review methodology

As we aim to map out how technology has been used in previous research and to critically examine this literature in relation to the digital world, we have employed a critical scoping review methodology. Scoping reviews are ideal for clarifying key concepts and for identifying knowledge gaps (Munn et al. Citation2018). We follow the framework by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for scoping reviews: (i) identifying the research question, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) study selection, (iv) charting the data, and (v) synthesising the findings. We also draw on the critical review tradition (Grant and Booth Citation2009). A critical review seeks to pinpoint unknown grounds, contradictions and controversies. Critical reviews are not simply for identifying ‘weaknesses’ in earlier studies; instead, they provide a ‘launch pad for a new phase of conceptual development’ (Grant and Booth Citation2009, 93).

The search process

The literature review was conducted in Scopus and ERIC in August 2021. Search terms included: authentic assessment OR authentic feedback AND higher education OR college OR undergraduate OR university. As the objective of this research was to examine the intersection between the digital and authentic assessment, not to assess authors’ positioning with regards to authenticity, we only included literature that was explicitly reported as ‘authentic assessment’. This is a departure from earlier literature reviews. Unlike Villarroel et al. (Citation2018) and Sokhanvar et al. (Citation2021), we did not employ general search terms such as ‘authentic instruction’ (Villarroel et al. Citation2018) or ‘soft skills’ and ‘graduate employability’ (Sokhanvar et al. Citation2021).

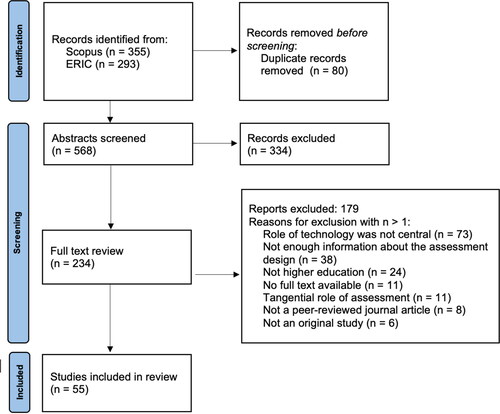

The PRISMA diagram of the search process is depicted in . The first author screened all the abstracts with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). The first author conducted the full text review, and unclear cases were discussed together by the authors. For example, 12 studies were discussed by the authors in terms of whether the assessment design in the studies reflected a ‘peripheral’ or a ‘central’ role for the digital. To identify the studies that had explicitly and meaningfully designed the digital into assessment, we categorised all included papers for the role of the digital in the assessment designs as depicted in the studies. A three-fold categorisation was used: (1) no mention, (2) peripheral or unclear role, and (3) central role of the digital. Only assessment designs with a central role of technology were chosen for our review (). A total of 55 studies were included in the final dataset.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

No quality assessment was undertaken as we focused on the descriptions of assessment designs rather than the quality of the research initiatives themselves; quality assessment is also not required by the scoping and critical review traditions (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Munn et al. Citation2018). We did not restrict the date for our review as we wanted to map out how the digital has been designed into assessment since the beginning of authentic assessment studies.

Analysis

We commenced by extracting the descriptive and contextual information of the assessment designs within the studies. We coded the year, country, discipline, type of authentic assessment (e.g. e-portfolio) and the digital technology used in assessment (e.g. the Moodle Learning Management System, LMS). Furthermore, we coded the explicitly stated rationale of assessment (credentialing, development, sustainability, or no mention) (Boud and Soler Citation2016). This categorisation was based on a holistic evaluation of each study, drawing on both the original authors’ words (e.g. the concept of ‘formative assessment’ was often used explicitly to imply the development rationale) and our own interpretations. Many studies reflected multiple rationales.

We then analysed how the digital was designed into the reported assessment design in the 55 studies. To do this we employed our previously developed conceptual framework, which articulates the complex relationships between assessment and the digital (Bearman et al. Citation2022). This framework proposes three main purposes for designing the digital into assessment. The first purpose is the rationale of improving assessment. The second purpose is the promotion and credentialing of students’ engagement with technology, which reminds us that learning how to engage with technology can also be an explicit learning objective. The third purpose focuses on developing and credentialing human capabilities in the digital world, by which we mean those characteristics that are uniquely human and that neither machines nor artificial intelligence could perform. We define these capabilities as the ‘ways of knowing, doing and being within a digitally-mediated society’ (Bearman et al. Citation2022, 8).

In addition to the deductive analysis, we also inductively coded for other purposes of authentic assessment design beyond the framework categories.

Findings

Overview of the dataset

Multiple regions were represented: 29 papers from Australasia, 14 from Europe (including the UK), and 12 from North America. Multiple disciplines were represented, with social sciences and humanities accounting for 38% (21 studies) of the dataset.

Various types of assessment were represented in the dataset. For example, 14 studies focussed on e-portfolios, 11 on some forms of authentic online tasks, eight on authentic examinations, five on longer authentic projects, four on simulations and four on authentic case studies. The technology used varied from LMSs to online materials to ‘multimedia’ to videos to flashcards.

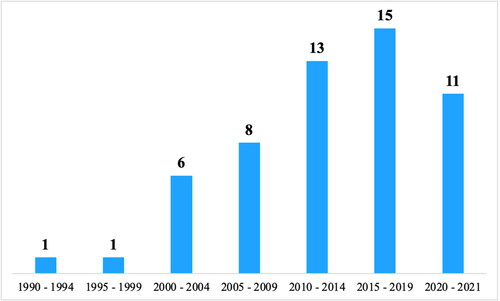

presents the publication year of the studies. The first study published in our dataset was by Mills (Citation1997). There is a growing trend in the number of publications with a focus on the digital, as 11 of the 55 studies (20%) were published between 2020 and August 2021.

Deductive analysis

The most predominant approach (52/55) employed the digital as a means to improve the assessment itself; 29/55 designs sought to develop or credential the students’ digital capabilities; 8/55 intended to develop or credential the human capabilities.

Purpose 1: digital tools for better assessment

Fifty-two assessment designs - almost all of them – employed the digital as a tool to improve the assessment. We analysed these designs firstly for their alignment with three assessment rationales: in particular Boud and Soler’s (Citation2016) distinctions between assessment that: (a) credentials student work, (b) develops student learning, and (c) provides opportunities for sustainable longer-term learning. We next considered how the digital was employed, drawing on the Substitution Augmentation Modification and Redefinition (SAMR) framework (Puentedura Citation2006) that addresses the level of innovation in educational design. We categorised assessment designs as either a) digitally enhanced – where a non-technological task is digitised to enable higher efficiency or usability or b) digitally transformed – where the digital prompts students to do things that they could not otherwise achieve.

Assessment rationales

Many assessment designs reflected multiple rationales, and three studies were coded to include all of them (Allen et al. Citation2014; Baird, Gamble, and Sidebotham Citation2016; Daud et al. Citation2020). The 27 designs that emphasised solely or mostly credentialing tended to focus on authentic testing or performance situations. For example, Okada et al. (Citation2015) described an online oral examination, which aligned with authentic legal practice. The 21 designs with a main focus on development often included formative assessment practises to foster student learning. For example, Colbran et al. (Citation2017) introduced digital flashcards in constitutional law as a form of formative assessment. Finally, 18 designs with an emphasis on sustainability focused on longer-term development of the students as future professionals in their field. For example, Baird et al. (Citation2016) described an e-portfolio capstone assessment in a midwifery program. The portfolio collected a meaningful set of artefacts to summatively demonstrate students’ skills and enabled a ‘deep level of thinking and reflection’ (p. 16) while also explicitly being ‘reflective of professional practice requirements’ (p. 13).

Level of digital enhancement

The 18 assessment designs that drew on digital enhancement focussed mainly on providing high quality digital, authentic assessment for large masses of students, thus having minimal impact on the assessment experience but more on how the assessment was delivered. For example, Marriott (Citation2007a) introduced a digital case study based examination in medical education: ‘Utilising a purpose-designed computer program the students selected a standardised virtual patient from a database of over 200 potential patients’ (2007b, 344). Designs that took a digital transformation approach (34) reframed assessment design through the digital. Digital technology transformed summative assessment designs, such as examinations, into an authentic form. Often, the digital enabled students to use various media such as images, audio clips, and video in an authentic way. For example, e-portfolios were described to transform traditional pen-and-paper assessment design into a multimodal experience whose final product could, in the end, be used as an authentic artefact in social media and employment situations (e.g. Lewis and Gerbic Citation2012; Bradley and Schofield Citation2014; Yang, Tai, and Lim, Citation2016).

Purpose 2: developing and credentialing digital literacies

A total of 29 studies drew explicitly on the purpose of developing students’ digital literacies with the majority orienting towards mastery or proficiency. Developing students’ digital literacies requires them to gain mastery or proficiency with certain technology, such as learning how to use a certain software appropriately. Digital literacies may also include the skills for evaluation and critique of the digital. This aspect reminds that students should not only be taught to understand technology as a procedural tool but as a social practice with social consequences.

Mastery or proficiency

That authentic assessment should foster students’ mastery in digital skills was the prominent theme: ‘Proficiency with technology clearly sits within the realm of skills necessary to be a functional and contributing member of society’ (Ferns and Comfort Citation2014, 270). Many studies directly named digital literacies as a crucial learning goal. ‘Authenticity’ was seen in digital design that reflected disciplinary, ‘real-world’ practices. For example, rather than working in the university LMS, students were encouraged to learn digital skills that had relevance after graduation (Green and Emerson Citation2008). Students were trained to master authentic digital tools that are used in workplaces such as Google Drive and Dropbox (Harver, Zuber, and Bastian Citation2019), website design tools (Hastie and Sinelnikov Citation2007), video editing and production skills (Willmott Citation2015; Scott and Unsworth Citation2018), portable document file (PDF) skills (Brown and Boltz Citation2002), digital presentation skills (Chan Citation2011), and text lay-out skills (e.g. LaTeX) (Mallet Citation2008; Nurmikko-Fuller and Hart Citation2020).

Another important theme in the dataset was that students should learn to use digital communication tools (e.g. WhatsApp, Skype, and email) in an authentic way (e.g. Herrington, Parker, and Boase-Jelinek Citation2014). Hanna (Citation2002) reported how online discussion boards promote learning communities in digitally authentic ways: ‘Students felt more open to express their misunderstanding of concepts through non-face-to-face means. Online collaboration between students extended the scope of the concepts covered in the course and the instructor was able to link online discussions to subsequent lectures and activities’ (132).

Digital mastery was also fostered through the production of digitally authentic products. For example, Lewis and Gerbic (Citation2012) discussed how the digital design of e-portfolios in pre-service teacher education could reflect authentic teaching practices (e.g. by using digital technologies that are commonly used in schools), reflecting digital literacies specific to teachers (see also Gatlin and Jacob Citation2002; Johnson-Leslie Citation2009).

In many studies, it was reported that students required adequate support for developing their digital literacies. This reminds us about how support and scaffolding for digital literacies needs to be designed into assessment design. For example, if digital literacies are named as an explicit learning goal, then students should be engaged in feedback processes in relation to these. Moreover, industry collaboration was promoted to enhance students’ digital literacies. Jopp (Citation2020) reported how the Learning Transformations Unit of the university collaborated in authentic task design using Google Maps. An industry representative provided up-to-date data for students for the task and took part in evaluating the final products.

Critique or resistance

Critical approaches to digital literacies were notably absent. Some studies hinted toward this direction without explicitly designing critique and resistance as a part of the assessment design. For example, Johinke (Citation2020) mentions critical digital literacies in relation to Wikipedia entry tasks but does not elaborate on how this aspect is seen to be intentionally fostered in the assessment design. Similarly, Herrington et al. (Citation2014) discuss how digital technologies are taught ‘as objects of study in their own right, rather than as powerful cognitive tools to be used intentionally to solve problems and create meaningful products’ (p. 24); yet the task design did not support students to develop critical approaches to technology by design.

Purpose 3: developing and credentialing human capabilities for a digital world

Eight studies explicitly took a ‘digital world approach’ by orienting towards developing uniquely human capabilities through digitally mediated assessment. We divide such assessment designs into two categories. First, assessment could reflect how the digital world impacts students’ future activities in employment and beyond. Second, assessment could develop students’ sense of future self by guiding students in becoming future professionals. Both these approaches remind us that designing the digital into assessment does not necessarily mean that students should directly interact with technological devices, but that assessment should support students to be and become within the digital world.

Future activities

Assessment designs that drew on students’ future activities in the workplace focussed on those human characteristics that machines or artificial intelligence could not succeed with. Thus, digital assessment design developed ‘knowledge workers’ for the digital world. However, these assessment designs did not always directly engage with the digital but focussed on developing unique human capabilities in the digital world.

Many studies emphasised that digitally oriented assessment tasks should reflect the likely future realities of one’s discipline. Durand (Citation2016) introduced a blog task in tourism and hospitality studies that required students to produce an assessment artefact that would most likely be needed in the future: ‘This contributed to their preparation for professional life in the travel industry’ (Durand Citation2016, 348). Similarly, Johnson-Leslie (Citation2009) justified the use of e-portfolios as an authentic future practice for pre-service teachers as ‘today’s pre-service teachers are ‘growing up digital’ and they are “growing up” with e-portfolio assessment’ (387). Creative and personal e-portfolios were used to develop students’ inherently human capabilities for future teaching activities.

Collaborative problem-solving and co-creation were introduced as uniquely human capabilities that were being assessed. For example, Tay and Allen (Citation2011) discussed collaborative use of social media in a task that required students to create a public magazine. Technology enabled assessment enabled a move away ‘from a knowledge-object orientation towards process-driven approaches – not what to know, but how to know’” (154). Tay and Allen also reported a wiki assessment task. The students shared co-authorship of wiki articles through the digital space, offering authentic, digital peer feedback during the process. The final product could be published on social media: yet another digital space for collaboration and co-creation.

Sense of the self

Studies that sought to develop students’ ‘sense of the self’ focussed on exploring and developing students’ digital identities in the world beyond the university. This work challenged the idea of ‘place’ and identities as stable, instead emphasising that students needed to construct their online persona through networked platforms and practices. Here, we introduce the four studies that reflected this purpose.

Hein and Miller (Citation2004) introduced an assessment task which developed students’ identities in a digitally mediated world (notably in 2004!). The assessment task was a Family History Assignment in Chicano Studies that required students to ‘define themselves within their families’ collective experience’ (310) through an exploration of internet resources. As such, the assessment design aimed to develop students’ identities amidst digital resources and infrastructures: ‘The familia history assignment personalizes learning. It allows students to make a personal connection between their private lives and the public knowledge gained in this class as well as other classes and between their personal knowledge and the public information infrastructure’ (318).

The three other studies valued students’ personal backgrounds, identities and ways of thinking as a part of the assessment task. Nurmikko-Fuller and Hart (Citation2020) introduced a media-rich assessment task in media studies. Students learned how to use digital technology in ways that intertwined with their own lives: ‘There is no textbook – the technology is moving faster than the schedules of book publishers – the course gives students the task of examining their own lives, beliefs and relationships’ (p. 171). Kohnke et al. (Citation2021) described an assessment task using infographics as a form of digital multimodal authoring of self for an external audience. Through designing digital infographics about their social projects students constructed their authorial agency and ‘growth as designers and thinkers’ (p. 5). Finally, the study by Sargent and Lynch (Citation2021) brought forth the importance of emotions, embodiment and vulnerability in digitally mediated assessment design. The task design asked students to produce digital video narratives in physical education to ‘challenge hierarchical status quo assessment measures traditionally used at HE [Higher Education] institutions’ (p. 4). Emotions and vulnerability were explicitly designed into the task as ‘video narratives allowed the students in this study to be “vulnerable”, “expressive” and the embodied connections encouraged psychological emotions as an affective process’ (p. 8).

Inductive analysis

Our review identified an additional purpose for designing the digital into assessment that we had not conceptualised in our previous work (Bearman et al. Citation2022). It is particularly relevant to authentic assessment and we have articulated it as the purpose of fostering communality. Collaboration has been commonly named as an element of authentic assessment (e.g. Gulikers et al. Citation2004), but this purpose reaches further by shifting the focus from what the individual does to actively participating with the community through the digital. We derived this category from a single assessment design. Thompson’s (Citation2009) study in statistics education introduced a task design that aimed to foster social good in disability communities. Thus, authenticity was theorised in terms of whether it promoted positive change in the world outside the university. The students needed to undertake a new role as ‘active learners in pursuit of rich community-based projects’ (Thompson Citation2009, 4) as they worked together with disability agencies and organisations. For example, one project involved the students using digital tools to collect and analyse data to support independent living of blind adolescents and adults; this work was conducted closely with the community, not for them.

Discussion

In this study, we have critically reviewed the literature on authentic assessment to understand how the digital has been purposefully designed within the reported assessment designs. Our main findings imply that the digital was most often used to enhance assessment design (e.g. to make it more efficient or more ‘authentic’) and to develop students’ digital skills in rather instrumental ways such as learning to use specific software. The other purposes for designing the digital into assessment were less present; only eight authentic assessment designs sought to situate the students within the wider context of digital societies. The proposed fourth purpose was derived from a single example of fostering societal and community interactions through digitally mediated authentic assessment.

This review highlights the need for closer attention to the role of the digital in both authentic assessment design and research. Our students’ present and future lives take place within a digitally mediated society, yet our notions of authentic assessment do not take account of this. The digital is more than just a tool, or a mode of delivery in assessment design. This is why we do not simply propose that digital technology should be incorporated in authentic assessment frameworks as its own separate dimension or criterion. Instead, our review suggests that the earlier frameworks for authentic assessment should be considered in the context of the digital world; the four purposes for purposefully designing the digital into authentic assessment offer analytical tools for this. In order to grasp ‘authenticity’ in the digital world, authentic assessment needs to meaningfully engage with all the four purposes - and not predominantly with the first two as our review shows. This reinforces the value of a conceptualisation of authentic assessment that orients students to society (McArthur Citation2022), rather than a focus on task features.

The fourth industrial revolution challenges higher education to rethink its teaching practices in order to prepare students for digitally mediated futures. Authentic assessment should play a key role in this equation (see Janse Van Rensburg, Coetzee, and Schmulian Citation2021). Our review has shown that despite the growing number of publications on digitally mediated authentic assessment, the digital world was largely not accounted for, and many of these did so at an instrumental level. Given the profound impact assessment has on student learning and studying, we emphasise the need for authentic assessment design to consider the digital world (Bearman et al. Citation2022). Otherwise it might be that critical digital literacies (and likewise ideas such as digitally mediated collaborative problem-solving) are promoted in the curricula but not credentialled or developed through assessment. Although these human capabilities are commonly articulated within graduate outcome statements, it would seem that our assessment is not yet well aligned, at least when it comes to reports in research literature. Authentic assessment research has sought to connect assessment in higher education with the requirements of students’ disciplines and future professions; it is only through a proper understanding of its digital dimensions, that authentic assessment designs can meaningfully prepare students for the digital world.

Implications for research

We call for further digitally mediated authentic assessment research on critical digital literacies. Through an exploration of such critical literacies, authentic assessment research could meaningfully reach beyond ‘technopositivist’ approaches to digital assessment design that only frame the digital in a positive light (Berry Citation2014). For example, there is a need for further studies concerning assessment designs with respect to the wider socio-political questions of higher education, such as marketisation, privatisation and datafication (Selwyn Citation2007; Ovetz Citation2021). We should also consider the impact of digital surveillance upon students, including anxiety (Conijn et al. Citation2022), and how authentic assessment design could foster students’ own awareness and agency over such issues through critical digital literacies.

This review also suggests that authentic assessment designs are not incorporating human capabilities, or ways of knowing and being in a digital world. While it is possible that this is happening outside of the assessment literature, it seems to us that this is a largely missed opportunity for authentic assessment research. While there have been some calls to orient authentic assessment towards the questions of student identity and becoming (Vu and Dall’Alba Citation2014; Ajjawi et al. Citation2020; McArthur Citation2022), research on how to achieve such goals through digitally mediated authentic assessment continues to lag. We suggest that there will be increasing significance for the development of human capabilities such as digitally mediated creativity (Janse Van Rensburg et al. Citation2021) and students’ evaluative judgement, the capability to make judgements about quality of work (Bearman et al. Citation2020). This means authenticity is not just about the ‘here and now’, but about helping students come to grips with ‘there and later’ as well. How might assessment promote capabilities in a way that takes account of ‘future authentic’, the ways of working that have not yet been developed (Dawson and Bearman Citation2020)? This is an exciting area for future research that necessarily takes us away from single points in time into understanding the longitudinal impact of assessment designs.

Finally, this review highlights fostering communality as a fourth possible purpose for the digital, both for authentic assessment and within higher education more broadly. When this is considered alongside the notion of authentic assessment design supporting students as they construct their possible (future) selves in relation to the communities they seek to join, some interesting possibilities come to light. While digitally mediated communication and collaboration have been addressed widely in earlier literature (e.g. Hanna Citation2002; Herrington et al. Citation2014), wider communal approaches beyond the limits of higher education have thus far been marginal (McArthur Citation2022). As McArthur outlines, this powerful idea connects assessment with its broader societal contexts, and with the goals of social good and justice. However, digital communities are not bound by higher education institutions, and this means that notions of trust, accountability and even student-institutional relationships may change. In coming to reconceptualise authentic assessment to include notions of self within digital communities, we must ensure that communality is indeed fostered rather than hindered through our assessment designs.

Finally, if, as this review suggests, authentic assessment designs should expand to ensure that the digital is integrated into the curriculum in a fundamental way, we ourselves as researchers need to practice what we preach. If we are suggesting that authentic assessment designs should promote critical digital literacies, we too should engage in these practices. We see great potential in authentic assessment research in informing better assessment policy and practice, but this might require us researchers to draw on critical rather than complementary approaches.

Limitations

Our review study has its limitations. First, we have mainly restricted our analysis to the design sections of the reviewed studies. We did not address the research methodologies nor the quality of the studies. Moreover, we have restricted our review to peer-reviewed, published studies, and so have excluded many other ways of reporting authentic assessment designs such as book chapters, reports, and syllabi.

Our review has taken at face value the ‘authenticity’ of the assessment designs as they have been reported in the studies. Indeed, our study has shown that there has not been consensus on digitally mediated forms of authenticity. We did this as our main purpose was to identify and categorise the multiple possible purposes for designing the digital into assessment. The next step would be to analyse how specific designs might achieve the claimed purposes. For purposes three and four, more research is needed before this is possible.

One important limitation for our study that warrants further investigation is that we did not analyse the potential harms that the digital might present for students and assessment designs alike, even though it was part of the conceptual framework (see Bearman et al. Citation2022). It is notable that none of the papers in our review discussed the possible harms of designing the digital into authentic assessment. For example, digital security and academic integrity have been discussed frequently in relation to authentic assessment (e.g. Linden and Gonzalez Citation2021). This may be due to an erroneous perception that authentic assessment designs always counteract or prevent cheating (Dawson Citation2020). In addition, less attention has been given to the risks that digital surveillance promotes for the authenticity of assessment, and for other factors such as student anxiety (Conijn et al. Citation2022). Analysing such harms and risks presents an interesting future trajectory for authentic assessment research. For example, there are profound ethical implications around assessment artefacts being openly available to the public and permanently on record (see Ajjawi, Boud, and Marshall Citation2020), and we need to coordinate efforts to consider how we might support students to build their personas within digital communities (external to the university) in safe ways.

Conclusion

Our review has identified that there is scope for deeper engagement with digitally mediated forms of authentic assessment. We argue that in order to fit its purpose of preparing students for unknown, digitally mediated futures, authentic assessment needs to engage with the digital in meaningful ways. We have advanced an organising framework for digital assessment design to guide future research and practice on authentic assessment in this quest.

References

- Ajjawi, R., J. Tai, T. L. Huu Nghia, D. Boud, L. Johnson, C. J, and Patrick, C. J. 2020. “Aligning Assessment with the Needs of Work-Integrated Learning: The Challenges of Authentic Assessment in a Complex Context.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (2): 304–316. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1639613.

- Ajjawi, R.D. Boud, and D. Marshall. 2020. “Repositioning Assessment-as-Portrayal: What Can we Learn from Celebrity and Persona Studies?.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, and D. Boud, 65–78. Cham: Springer.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- * Allen, J. M., S. Wright, and M. Innes. 2014. “Pre-Service Visual Art Teachers’ Perceptions of Assessment in Online Learning.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (9): 1–17. doi:10.14221/ajte.2014v39n9.1.

- Ashford-Rowe, K., J. Herrington, and C. Brown. 2014. “Establishing the Critical Elements That Determine Authentic Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (2): 205–222. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.819566.

- * Baird, K., J. Gamble, and M. Sidebotham. 2016. “Assessment of the Quality and Applicability of an e-Portfolio Capstone Assessment Item within a Bachelor of Midwifery Program.” Nurse Education in Practice 20: 11–16. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2016.06.007.

- * Balderas, A., M. Palomo-Duarte, J. M. Dodero, M. S. Ibarra-Sáiz, and G. Rodríguez-Gómez. 2018. “Scalable Authentic Assessment of Collaborative Work Assignments in Wikis.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 15 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1186/s41239-018-0122-1.

- Bearman, M., J. H. Nieminen, and R. Ajjawi. 2022. “Designing Assessment in a Digital World: An Organising Framework.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2069674.

- Bearman, M.D. Boud, and R. Ajjawi. 2020. “New Directions for Assessment in a Digital World.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, and D. Boud, 7–18. Cham: Springer.

- Berry, D. M. 2014. Critical Theory and the Digital. London: A&C Black.

- Boud, D., and R. Soler. 2016. “Sustainable Assessment Revisited.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (3): 400–413. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- * Bradley, R., and S. Schofield. 2014. “The Undergraduate Medical Radiation Science Students’ Perception of Using the e-Portfolio in Their Clinical Practicum.” Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 45 (3): 230–243. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2014.04.004.

- * Brown, C., and R. Boltz. 2002. “Planning Portfolio: Authentic Assessment for Library Professionals.” School Library Media Research 5: 1–19.

- * Cacchione, A. 2015. “Creative Use of Twitter for Dynamic Assessment in Language Learning Classroom at the University.” Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal 24: 145–161.

- * Cameron, C., and J. Dickfos. 2014. “Lights, Camera, Action!’ Video Technology and Students’ Perceptions of Oral Communication in Accounting Education.” Accounting Education 23 (2): 135–154. doi:10.1080/09639284.2013.847326.

- * Chan, V. 2011. “Teaching Oral Communication in Undergraduate Science: Are we Doing Enough and Doing It Right?” Journal of Learning Design 4 (3): 71–79. doi:10.5204/jld.v4i3.82.

- * Colbran, S., A. Gilding, S. Colbran, M. J. Oyson, and N. Saeed. 2017. “The Impact of Student-Generated Digital Flashcards on Student Learning of Constitutional Law.” The Law Teacher 51 (1): 69–97. doi:10.1080/03069400.2015.1082239.

- Conijn, R., A. Kleingeld, U. Matzat, and C. Snijders. 2022. “The Fear of Big Brother: The Potential Negative Side-Effects of Proctored Exams.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. doi:10.1111/jcal.12651.

- * Curtis, V., R. Moon, and A. Penaluna. 2021. “Active Entrepreneurship Education and the Impact on Approaches to Learning: Mixed Methods Evidence from a Six-Year Study into One Entrepreneurship Educator’s Classroom.” Industry and Higher Education 35 (4): 443–453. doi:10.1177/0950422220975319.

- * Daud, A., R. Chowdhury, M. Mahdum, and M. N. Mustafa. 2020. “Mini-Seminar Project: An Authentic Assessment Practice in Speaking Class for Advanced Students.” Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn) 14 (4): 509–516. doi:10.11591/edulearn.v14i4.16429.

- Dawson, P. 2020. Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World: preventing e-Cheating and Supporting Academic Integrity in Higher Education. New York: Routledge.

- Dawson, P, and M. Bearman. 2020. “Concluding Comments: reimagining University Assessment in a Digital World.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, and D. Boud, 291–296. Cham: Springer.

- * Dawson, V., P. Forster, and D. Reid. 2006. “Information Communication Technology (ICT) Integration in a Science Education Unit for Preservice Science Teachers; Students’ Perceptions of Their ICT Skills, Knowledge and Pedagogy.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 4 (2): 345–363. doi:10.1007/s10763-005-9003-x.

- * Dermo, J., and J. Boyne. 2014. “Assessing Understanding of Complex Learning Outcomes and Real-World Skills Using an Authentic Software Tool: A Study from Biomedical Sciences.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 8 (1): 101–112.

- * Durand, S. 2016. “Blog Analysis: An Exploration of French Students’ Perceptions towards Foreign Cultures during Their Overseas Internships.” Alberta Journal of Educational Research 62 (4): 335–352.

- * Ferns, S., and J. Comfort. 2014. “Eportfolios as Evidence of Standards and Outcomes in Work-Integrated Learning.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 15 (3): 269–280.

- * Fulton, J., P. Scott, F. Biggins, and C. Koutsoukos. 2021. “Fear or Favor: Student Views on Embedding Authentic Assessments in Journalism Education.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 22 (1): 57–71.

- * Gatlin, L., and S. Jacob. 2002. “Standards-Based Digital Portfolios: A Component of Authentic Assessment for Preservice Teachers.” Action in Teacher Education 23 (4): 35–42. doi:10.1080/01626620.2002.10463086.

- * Gemmell, A. M., I. G. Finlayson, and P. G. Marston. 2010. “First Steps towards an Interactive Real-Time Hazard Management Simulation.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 34 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1080/03098260902982419.

- Grant, M., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- * Green, K., and A. Emerson. 2008. “Reorganizing Freshman Business Mathematics II: Authentic Assessment in Mathematics through Professional Memos.” Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications 27 (2): 66–80. doi:10.1093/teamat/hrn002.

- Gulikers, J., T. J. Bastiaens, and P. A. Kirschner. 2004. “A Five-Dimensional Framework for Authentic Assessment.” Educational Technology Research and Development 52 (3): 67–86. doi:10.1007/BF02504676.

- * Hanna, N. R. 2002. “Effective Use of a Range of Authentic Assessments in a Web Assisted Pharmacology Course.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 5 (3): 123–137.

- * Harver, A., P. D. Zuber, and H. Bastian. 2019. “The Capstone ePortfolio in an Undergraduate Public Health Program: Accreditation, Assessment, and Audience.” Frontiers in Public Health 7: 125. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00125.

- * Hastie, P. A., and O. A. Sinelnikov. 2007. “The Use of Web-Based Portfolios in College Physical Education Activity Courses.” The Physical Educator 64 (1): 21–29.

- * Hein, N. P., and B. A. Miller. 2004. “¿Quién Soy? Finding my Place in History: Personalizing Learning through Faculty/Librarian Collaboration.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 3 (4): 307–321. doi:10.1177/1538192704268121.

- * Herrington, J., and A. Herrington. 1998. “Authentic Assessment and Multimedia: How University Students Respond to a Model of Authentic Assessment.” Higher Education Research & Development 17 (3): 305–322. doi:10.1080/0729436980170304.

- * Herrington, J., J. Parker, and D. Boase-Jelinek. 2014. “Connected Authentic Learning: Reflection and Intentional Learning.” Australian Journal of Education 58 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1177/0004944113517830.

- Janse Van Rensburg, C., S. A. Coetzee, and A. Schmulian. 2021. “Developing Digital Creativity through Authentic Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1968791.

- * Johinke, R. 2020. “Social Production as Authentic Assessment: Wikipedia, Digital Writing, and Hope Labour.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (5): 1015–1025. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1750192.

- * Johnson-Leslie, N. A. 2009. “Comparing the Efficacy of an Engineered-Based System (College Livetext) with an off-the-Shelf General Tool (Hyperstudio) for Developing Electronic Portfolios in Teacher Education.” Journal of Educational Technology Systems 37 (4): 385–404. doi:10.2190/ET.37.4.d.

- * Jopp, R. 2020. “A Case Study of a Technology Enhanced Learning Initiative That Supports Authentic Assessment.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (8): 942–958. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1613637.

- * Kavanagh, Y., and D. Raftery. 2017. “Physical Physics – Learning and Assessing Light Concepts in a Novel Way.” MRS Advances 2 (63): 3933–3938. doi:10.1557/adv.2017.589.

- * Kohnke, L., A. Jarvis, and A. Ting. 2021. “Digital Multimodal Composing as Authentic Assessment in Discipline-Specific English Courses: Insights from ESP Learners.” TESOL Journal 12 (3): e600. doi:10.1002/tesj.600.

- * Lam, W., J. B. Williams, and A. Y. Chua. 2007. “E-Xams: Harnessing the Power of ICTs to Enhance Authenticity.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 10 (3): 209–221.

- * Lewis, L., and P. Gerbic. 2012. “The Student Voice in Using Eportfolios to Address Professional Standards in a Teacher Education Programme.” Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 3 (1): 17–25. doi:10.21153/jtlge2012vol3no1art555.

- * Linden, K., and P. Gonzalez. 2021. “Zoom Invigilated Exams: A Protocol for Rapid Adoption to Remote Examinations.” British Journal of Educational Technology 52 (4): 1323–1337. doi:10.1111/bjet.13109.

- * Mallet, D. G. 2008. “Asynchronous Online Collaboration as a Flexible Learning Activity and an Authentic Assessment Method in an Undergraduate Mathematics Course.” EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 4 (2): 143–151. doi:10.12973/ejmste/75314.

- * Marriott, J. L. 2007a. “Development and Implementation of a Computer-Generated ‘Virtual’ Patient Program.” Pharmacy Education 7 (4): 335–340. doi:10.1080/15602210701673787.

- * Marriott, J. L. 2007b. “Use and Evaluation of “Virtual” Patients for Assessment of Clinical Pharmacy Undergraduates.” Pharmacy Education 7 (4): 341–349. doi:10.1080/15602210701673795.

- McArthur, J. 2022. “Rethinking Authentic Assessment: Work, Wellbeing and Society.” Higher Education. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y.

- * Messham-Muir, K. 2012. “From Tinkering to Meddling: Notes on Engaging First Year Art Theory Students.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 9 (2): 3.

- * Mills, E. 1997. “Portfolios: A Challenge for Technology.” International Journal of Instructional Media 24 (1): 23–29.

- * Moccozet, L., O. Benkacem, E. Berisha, R. T. Trindade, and P. Y. Bürgi. 2019. “A Versatile and Flexible e-Assessment Framework towards More Authentic Summative Examinations in Higher-Education.” International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Life Long Learning 29 (3): 211–229.

- * Morris, M., A. Porter, and D. Griffiths, University of Wollongong, Australia 2004. “Assessment is Bloomin’ Luverly: Developing Assessment That Enhances Learning.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 1 (2): 46–62. doi:10.53761/1.1.2.5.

- Munn, Z., M. D. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- * Nurmikko-Fuller, T., and I. E. Hart. 2020. “Constructive Alignment and Authentic Assessment in a Media-Rich Undergraduate Course.” Educational Media International 57 (2): 167–182. doi:10.1080/09523987.2020.1786775.

- * Okada, A., P. Scott, and M. Mendonça. 2015. “Effective Web Videoconferencing for Proctoring Online Oral Exams: A Case Study at Scale in Brazil.” Open Praxis 7 (3): 227–242. doi:10.5944/openpraxis.7.3.215.

- Ovetz, R. 2021. “The Algorithmic University: On-Line Education, Learning Management Systems, and the Struggle over Academic Labor.” Critical Sociology 47 (7-8): 1065–1084. doi:10.1177/0896920520948931.

- Puentedura, R. 2006. “Transformation, technology, and education [Blog post].” http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/.

- * Raymond, J. E., C. S. Homer, R. Smith, and J. E. Gray. 2013. “Learning through Authentic Assessment: An Evaluation of a New Development in the Undergraduate Midwifery Curriculum.” Nurse Education in Practice 13 (5): 471–476. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2012.10.006.

- * Rinto, E. E. 2013. “Developing and Applying an Information Literacy Rubric to Student Annotated Bibliographies.” Evidence Based Library and Information Practice 8 (3): 5–18. doi:10.18438/B8559F.

- * Sabin, M., K. W. Weeks, D. A. Rowe, B. M. Hutton, D. Coben, C. Hall, and N. Woolley. 2013. “Safety in Numbers 5: Evaluation of Computer-Based Authentic Assessment and High Fidelity Simulated OSCE Environments as a Framework for Articulating a Point of Registration Medication Dosage Calculation Benchmark.” Nurse Education in Practice 13 (2): e55–e65. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2012.10.009.

- * Sargent, J., and S. Lynch. 2021. “None of my Other Teachers Know my Face/Emotions/Thoughts’: Digital Technology and Democratic Assessment Practices in Higher Education Physical Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (5): 693–705. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2021.1942972.

- * Schonell, S., and R. Macklin. 2019. “Work Integrated Learning Initiatives: Live Case Studies as a Mainstream WIL Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (7): 1197–1208. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1425986.

- * Scott, M., and J. Unsworth. 2018. “Matching Final Assessment to Employability: Developing a Digital Viva as an End of Programme Assessment.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 373–384. doi:10.1080/23752696.2018.1510294.

- Selwyn, N. 2007. “The Use of Computer Technology in University Teaching and Learning: A Critical Perspective.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 23 (2): 83–94. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00204.x.

- Schultz, M., K. Young, T. K. Gunning, and M. L. Harvey. 2022. “Defining and Measuring Authentic Assessment: A Case Study in the Context of Tertiary Science.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (1): 77–18. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1887811.

- * Silbereis, S. 2020. “Interactive, Online, Authentic Assessment in a British University’s Procurement and Contract Practice Module: Case Study.” Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 12 (2): 05020002. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000381.

- Sokhanvar, Z., K. Salehi, and F. Sokhanvar. 2021. “Advantages of Authentic Assessment for Improving the Learning Experience and Employability Skills of Higher Education Students: A Systematic Literature Review.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 70: 101030. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101030.

- * Tay, E., and M. Allen. 2011. “Designing Social Media into University Learning: Technology of Collaboration or Collaboration for Technology?” Educational Media International 48 (3): 151–163. doi:10.1080/09523987.2011.607319.

- * Tepper, C., J. Bishop, and K. Forrest. 2020. “Authentic Assessment Utilising Innovative Technology Enhanced Learning.” The Asia Pacific Scholar 5 (1): 70–75. doi:10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/SC2065.

- * Thompson, C. J. 2009. “Educational Statistics Authentic Learning CAPSULES: Community Action Projects for Students Utilizing Leadership and e-Based Statistics.” Journal of Statistics Education 17: 1. doi:10.1080/10691898.2009.11889508.

- * Way, K. A., L. Burrell, L. D’Allura, and K. Ashford-Rowe. 2021. “Empirical Investigation of Authentic Assessment Theory: An Application in Online Courses Using Mimetic Simulation Created in University Learning Management Ecosystems.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1740647.

- Wiggins, G. 1990. “The Case for Authentic Assessment.” Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 2 (1): 2.

- * Willmott, C. J. 2015. “Teaching Bioethics via the Production of Student-Generated Videos.” Journal of Biological Education 49 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1080/00219266.2014.897640.

- Villarroel, V., S. Bloxham, D. Bruna, C. Bruna, and C. Herrera-Seda. 2018. “Authentic Assessment: Creating a Blueprint for Course Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (5): 840–854. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396.

- Vu, T. T., and G. Dall’Alba. 2014. “Authentic Assessment for Student Learning: An Ontological Conceptualisation.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 46 (7): 778–791. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.795110.

- * Yang, M., M. Tai, and C. P. Lim. 2016. “The Role of e-Portfolios in Supporting Productive Learning.” British Journal of Educational Technology 47 (6): 1276–1286. doi:10.1111/bjet.12316.