Abstract

The Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) is a process by which achievements gained through work or other experiences can be formally recognised and accredited in higher education. It has a role to play in providing accelerated routes for mature students and is particularly relevant to part-time learners. Despite studies showing the potential transformative effects and the benefits to retention, RPL remains a marginal activity. It is suggested that RPL assessment processes themselves may constitute a barrier to take-up and there has been a move to reconceptualise RPL as a distinctive specialised pedagogy for mediating knowledge sharing across boundaries. This paper contributes to this body of work through a study of RPL participants who were academics seeking credit for a postgraduate award. The research uses actor-network theory (ANT) to understand how and why they approached the RPL task in the way that they did. By understanding how things happened and how effects come into being it was possible to develop an RPL Translation and Transfer (RPLTT) model and typology that provides a heuristic for RPL design in practice contexts.

Background

Part-time higher education undergraduate student numbers have been in decline in England from a peak of almost 590,000 in 2008/09 to just under 270,000 in 2019/20 (Hubble and Bolton Citation2022). Changes to funding, austerity measures and the economic downturn have been identified as contributing to this decline. There has been a decline across the other UK nations but the drop in numbers is most marked in England.

Part-time students tend to be older than full-time students and high numbers are female. They are more likely to be in work and have caring responsibilities. These students often have more family and financial responsibilities than full-time students and this tends to make these students particularly sensitive to fee increases, higher levels of debt and the perceived risks of undertaking part time study (Hubble and Bolton Citation2022, 11).

Nationally, part-time students are more likely to discontinue their studies than full-time students (Hillman Citation2021). As UK universities respond to the drop in demand by reducing the number of part-time courses on offer, concern has been expressed about the impacts on widening participation, reskilling, productivity and economic growth. If this decline in numbers is to change new perspectives and approaches are required. Existing policy appears predicated on the assumption that should adults wish to resume their studies this would be via a ladder of vocational qualifications or access to higher education courses. However, it could be argued that the most efficient and effective route for a large proportion of part-time adult learners would be to value their human capital developed on-the-job or in other contexts through the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL), also known in the UK as the Assessment of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL). RPL provides a process by which prior learning achievements gained through experience in a range of contexts can be formally accredited in higher education.

Internationally, RPL is also referred to as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA), prior Learning Assessment and Recognition (PLAR), and, in other parts of Europe, the Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning (VNFIL). In the USA a study of more than 230,000 adult learners found that RPL learners were 22% more likely to complete their award than non-RPL learners. This was true for ‘adult students of color, low income adult students, and adult students across the academic performance spectrum’ (Klein-Collins et al. Citation2020, vi).

RPL potentially offers:

an innovative and flexible pedagogic model that accelerates the student’s trajectory thus saving the student money and time;

recognition for the considerable skills, knowledge and expertise gained through work and in other contexts; and

the opportunity to develop new types of partnership and models of study to support the development and application of knowledge acquired outside of formal study.

Whilst these advantages accrue for both full-time and part-time students, they are particularly important to part-time students juggling work, caring and family responsibilities. These students are likely to undertake higher education study for career advancement, to overcome qualification barriers in the workplace, or to facilitate a career transition. However, despite RPL policy commitments, Harris, Breier, and Wihak (Citation2011) report that internationally there is low overall take up.

RPL poses a challenge to the privileging of knowledge developed by and through the academy. Academic conservatism has generally led to an emphasis on demonstrating exact equivalence with learning in the taught curriculum, accompanied by a focus on the application of formal texts and canons of literature, rather than on exploring the equivalence and/or value of learning from experience more broadly. As one early proponent commented ‘a considerable amount of work is required of the APEL candidate to gain academic credit and it is often more demanding than the work completed by students on formal courses’ (Evans Citation1994, 77).

Butterworth (Citation1992) distinguished between credit-exchange and developmental APEL. In both the credit-exchange and developmental approaches assessment is generally via a portfolio of evidence with a narrative linked to specific learning outcomes or objectives. Butterworth (Citation1992) aligned the credit-exchange approach to National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs), which provide training and qualifications related to a specific job. The focus is on the foregrounding of evidence of performance, followed by assessment against pre-determined standards. Similar approaches can be seen in vocational education and training globally (Maurer Citation2021).

Unlike the credit-exchange approach with its focus on assessment of competence, Butterworth (Citation1992, 50) argued that the developmental approach provides ‘significant personal and professional development for the individual’, by drawing on models such as Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning cycle. Kolb’s model has been used by RPL practitioners to suggest that learning starts with a concrete experience and, through a process of reflective observation, leads to the development of generalisations and planned new approaches to similar experiences. Its foundations have been critiqued (Miettinen Citation2000) and Fenwick (Citation2003, 11) notes of experiential approaches that, ‘what becomes emphasised are the conceptual lessons gained from experience, which are quickly stripped of location and embeddedness’. Others have also criticised the dualistic ideological thinking that is implicit in models of reflective learning. Michelson (Citation2006) critiqued Kolb (Citation1984):

because he is at once representative and influential… [of the view that] experience always happens first; knowledge is the later product of experience acted upon by reason. (146, 149)

the activity in which knowledge is developed and deployed… is not separable from or ancillary to learning and cognition. Nor is it neutral. Rather, it is an integral part of what is learned. Situations might be said to co-produce knowledge through activity. Learning and cognition, it is now possible to argue, are fundamentally situated. (Brown, Collins, and Duguid Citation1989, 32)

[RPL] practitioners have placed too much faith in experiential learning philosophies and methodologies as the sole means to articulate, recognise, value, assess and accredit learning from experience… Such a state of affairs does not allow for problematising and improving practices. (9)

The study

This paper offers a contribution to the problematisation and development of RPL practice. It accords with a body of work that argues that:

RPL cannot be theorised as the conventional assessment of experiential knowledge with reference to a single source of epistemological authority. It is distinctively a specialised process for mediating knowledge claims that originate from two or more sets of discursive practices. (Cooper, Ralphs, and Harris Citation2017, 205)

The implications of this position are that RPL should be reconceptualised as a ‘specialised pedagogy’. (Cooper and Harris Citation2013, 450)

Some RPL participants initially produced portfolios that described the participant’s experience rather than drawing out their learning from that experience, and their work had to be revised. RPL practitioners are always exhorting learners not to be descriptive and to focus on demonstrating the learning from experience. Some participants achieved this whilst others struggled. It was not clear why there was this difference. It was not a matter of disciplinary differences. Participants in scientific disciplines could write insightful, convincing narratives for RPL while some participants in the social sciences needed extra help to do so, and vice versa. Although all participants eventually produced a credit-worthy portfolio there were differences in the end product, in size and writing style and in success rates at first submission. These differences reflected the individual’s approach to the task. There was one RPL process, one set of guidance and only one person advising participants. Therefore, it seemed that the differences were primarily the result of what the participants themselves were doing. Consequently, the aim of this study was to understand the RPL process from the perspective of the individual participant.

Research design

The research design was subject to ethics approval which included obtaining informed written consent to take part from participants. The sample included 19 academics from a variety of disciplines with one male, which reflected the gendered nature of engagement with the process. Each participant knew that their RPL application had been successful. In order that they were not relying entirely on a memory of what they included in their portfolio it was brought into the interview. A mix of participants were invited including some who had revised their work prior to final submission. The data collection method focused on an individual interview in which a narrative was prompted around the portfolio – how it was created and the significance of items of evidence for the individual. The participants and I were employed at the institution offering the programme. Such insider-research provided a rich data set but also meant that, as the researcher, I had to pay attention to where I put my focus when analysing the data, acknowledging my role in the research, and the need to make my effects visible in the analytical process. Therefore, I was especially careful to make transparent my understanding of their interpretations, checking and summarising positions provided and taking steps to maintain participant confidentiality. The interviews were transcribed and analysed for patterns in participants’ explanations. Notes for each participant recorded the properties of each interview, tracking emerging subjectivities, concepts and ideas related to their experience of the process.

Data analysis

Actor-network theory (ANT) was drawn upon for analysis of the data. Consistent with constructivism, ANT highlights that the reality we live in is one which is performed into existence and ‘helps to conceptualise how different realities are experienced and enacted by different actors’ (Cresswell, Worth, and Sheikh Citation2010, 3). ANT frees the researcher from the task of finding a single overarching explanation for how things come to be as they are. This was important as the data described how participants went about making their RPL claim, tracing actions and actors (a network) to understand how and why they do what they do. As Latour (Citation1999) noted, ‘Actors know what they do and we have to learn from them… It is us… who lack knowledge of what they do, and not they who are missing the explanation’ (19).

One of the distinguishing features of ANT is its focus on non-human actors and the lack of privileging of human actors. This is an approach missing from much of the writing in education that offers a largely individualised, cognitive or social framing of learning. Earlier research carried out with RPL participants (Pokorny Citation2013) implied that the material evidence included in a portfolio generally played an important role in the process for RPL participants, but this was not necessarily the same for the assessor, and it was unclear why this was the case. Thus, an approach that included material as well as human elements in its explanation was appealing.

ANT is concerned with tracing the process of translation by which any network expands or contracts, and through which knowledge becomes patterned in particular ways (Latour Citation1999). When translation has succeeded an actor-network will perform knowledge in a way that can be taken for granted and appear immutable, forming the reality of the process for the individual and driving their actions. Analysis of the data in this study focused on tracing the networks by which individual portfolios were produced and describing the realities of the process for each individual, providing insights into why they did what they did. Certain sensitising concepts from ANT applied to the data were particularly helpful. These included:

immutables, which are the taken for granted actor-networks that form the reality of the process for the individual;

intermediaries, which transport another force or meaning without changing it;

mediators, which can transform, modify or distort meanings to create possibilities and occurrences within the translation process;

obligatory passage points, through which all relations in the network must flow at some time: Callon (Citation1986) referred to this as problematisation; and

boundary objects: In ANT these can sit anywhere within a network, and mark both a separation and a connection. Star and Griesemer (Citation1989) argued that boundary objects are:

plastic enough to adapt to local needs and the constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites… They have different meanings in different social worlds, but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognisable, a means of translation. The creation and maintenance of boundary objects is a key process in developing and maintaining a coherence across intersecting social worlds. (393)

Thus, a boundary object is a key concept for tracing the translation of practice learning into an academic context.

Reporting the data

A report for each participant and six detailed case studies were produced. There were some broad similarities in the RPL experience of individuals, and these are categorised in .

Table 1. Participants’ RPL experiences.

Summaries of the data illustrate these categories. Names of participants have been changed to preserve anonymity.

Category A: RPL as a positive experience of articulating professional learning

I thought it [RPL] would help me to pull together what I had actually learned and put a framework around what I had learned and make me reflect on what I had actually done. (Thérèse)

Nine of the nineteen respondents were categorised as finding RPL a positive experience of articulating their professional learning. This was the largest category.

Each of these participants had their own network that made up their individual reality and influenced their interpretations of the process, some of which may be related back to their biography. One had been a secondary school teacher and offered this role as a direct link to her focus on reading as part of the process. Some were initially employed as researchers and reading was core to their professional career; others came from an industry/training background. Confidence was a theme in this group and in completing their RPL and they wanted ‘to have some theoretical support for what I’ve done’ in order to provide confidence in their professional articulation of their practice - as one participant said.

For me models and concepts are interesting… it was useful for me to see a lot of things that are quite obvious are written by people, so like I said it’s reassuring.

shows how the objective of the RPL process for these participants was to align their professional learning with the language of academic learning, enabling them to join a new community.

Table 2. Recognition of prior learning translation and transfer: pedagogic features.

Everyone in this category talked about how educational concepts provided a metalanguage through which they could articulate and make recognisable their professional learning in an academic context. Sometimes these concepts came from the two articles that had been provided. Other participants had read widely, although it had been stressed that the RPL process was about practice and did not require further reading and research. It was interesting to note that most participants, although academics, did not feel the need to include citations or a bibliography, and their reading was often invisible in the final portfolio. They were not reading and researching to demonstrate and apply knowledge, as in conventional academic practice. Instead, they problematised the RPL process as one of using these concepts to make their tacit knowledge explicit. They engaged with these concepts not as new learning but as a means of making visible their prior learning and translating it across contexts.

Participants talked of the ways in which these concepts supported meaning-making. They were mediators enabling them:

to properly understand what it is that you are asking so I could have my ah ha! moment. Oh yeah! I do that, and that… it gives you a better self-awareness. It’s kind of back to front in that way, isn’t it? So, when you finish, you think oh, actually, a bit of a sense of achievement because I really am doing all that. I wasn’t aware that this is what I’m doing necessarily.

That [evidence] is really the internal relationship between theory and practice, isn’t it? I am saying all this chat, but does it really, actually relate to anything that I have delivered?

Category B: RPL as a positive experience of demonstrating professional practice

My practice is my practice and that’s what I’m trying to demonstrate to you. (Olivie)

Seven of the nineteen participants reported finding RPL a positive experience of demonstrating professional practice.

Participants had varied backgrounds with slightly more coming from industry than an academic route. They had all come into teaching in a circuitous way, and it was perhaps less of a deliberate career choice than for participants in Category A. The concept of developing confidence in articulating their learning did not appear in the data, instead they talked about sharing their professional practice. shows that the objective for these participants was to communicate their professional practice peer to peer, rather than join a new community.

In contrast to Category A, each participant commented that it was the mediating effects of interrogating their evidence that was the catalyst for meaning making and writing their explanatory narratives. Reading did not appear as a mediator and some professed to have done none as they did not see it as relevant to the process. Instead, they problematised the RPL process as one of demonstrating their professional practice. This they did by asking questions of their practice or of artefacts from their practice: for example – what was the intention here?; how was the evidence designed?; what was the outcome? For some the evidence was in the mind of the writer, a module, a lecture, an activity. Others gathered evidence in a material sense, collecting physical artefacts before writing their narrative. One participant commented:

Perhaps if I didn’t produce the evidence… I wouldn’t have thought so deeply about it. How did I do that, and did it work? And how do I know it worked? Did I get any student feedback on that? So instead of just making that comment I considered it more deeply in terms of, was it useful? So, I was trying to provide substantiation to you the reader that this is what I did and this is how it worked out. So, I think that the whole process was reflective and perhaps more reflective because of having to evidence it.

Just showing some lecture slides doesn’t mean much to anyone else except those in that lecture room environment. But then I could relate to it, why is it this way? So, I would say just to write - I would have found that much, much harder.

Having done it, actually it was quite good because it showed you knew more than you thought you did. ‘I do this, and I can explain it’.

It can be seen in Appendix 11, this year’s module leader’s report, that I have taken into consideration the feedback from students in other years.

Category C: RPL as a negative experience of authenticating professional competence

I put that there so I could say, see I’m not just making it up. (Bella)

The three participants in Category C found the RPL process to be a negative experience of authenticating professional competence. Each was dissatisfied with the RPL process and found it constrained their ability to present their professional identity. In contrast to Category A and B participants, the mediating effects of the evidence were predominantly to silence, constrain or make invisible their practice.

There were two participants in this group who followed a generic university template rather than the RPL handbook guidance provided for their portfolio format. Paulette used this template which had 3 columns – ‘learning outcomes’, ‘links to evidence’ and ‘brief description of the evidence’. Her interpretation was that the assessment focus was on evidence. She argued that there was nowhere to express her professionalism, so she collated her evidence and then it was down to the assessor to ‘guess from the evidence what I have done’. She was clearly frustrated and had no confidence in the RPL process saying, ‘I don’t think it will achieve what you want it to achieve’. She knew what she wanted to say. At one stage she explained that she wanted to show the lessons she had learned around a module assessment and how she had changed it. However, ‘the rationale for the changes though it’s all in my mind’. She felt there was no place to express this learning or, ‘explain particular concepts’.

Emilie used the same template but changed its orientation from portrait to landscape and produced a lot of reflective text in the central column. Hers was the longest narrative at 38 pages whilst Paulette’s was the shortest at 3 pages. For both Paulette and Emilie, the template’s mediating effect was to focus on evidence as authentication. This focus on evidence as authentication and proof of competence was the immutable reality for this group. Emilie’s efforts were focused on providing the ‘correct evidence’. Thus, she tried to include impartial third-party reviews of her work, derived from quality assurance processes whilst also feeling that this focus on evidence was unfair.

Bella, the third participant in Category C, produced a portfolio that was more narrative in structure, but her conceptualisation of the process was equally constraining. She gathered her material evidence and wrote around it and, as with Paulette and Emilie, she understood the process to be one of providing material evidence as proof of competence. Thus, she felt her evidence had to provide authentication of ‘successful practice’. Therefore, an example of teaching she was passionate about and experienced as a ‘fabulous activity’ was omitted as only one student mentioned it in the end of module feedback. She was sceptical about the RPL process and its focus on authentication of competence through evidence, arguing that much of this evidence could be manipulated. She gave the example of a peer observation form completed by an office colleague, ‘so of course he’s going to say nice things’.

Discussion

Across the three categories there were broad similarities in the disciplinary backgrounds of participants, with the majority being in business, law and computer science: and in the length of time in teaching, with the minimum being 4 years and the majority around 8 years.

Analysis of the data using ANT provided useful insights. By tracing the individual actor-networks of participants in the study it was possible to identify three obligatory passage points (OPP) or ways that participants problematised (Callon Citation1986) the RPL experience. The key importance of the OPP is that it mediates interactions shaping the network and driving activities, helping to explain why actors do what they do. In this study each category has a different OPP that shaped the activities that flowed from it. These were;

articulating professional learning

demonstrating professional practice

authenticating professional competence

A significant relationship also emerged between the OPP and boundary objects.

In Category A the OPP was articulating professional learning, and participants were using concepts as a boundary object to name and index some relevant activity in their context, thus making visible the translation of learning across practice and academic contexts. It is important to note that the activity pre-existed the naming, not the other way around. The activity had meaning in the practice context, and it was the conceptual naming of it that was plastic enough to be recognisable and maintain a common identity across the two sites of learning. As one participant said, ‘it [the concept] helped me find those words or understand those words to give you the context of what it is I’m doing’. It was not the naming per se that was important but that the concept was common enough to enable different actors to recognise and use it to explain or translate practice. In Category A the evidence was not a mediator. Instead, it was an intermediary and of semiotic importance to the text. It helped participants to support and illustrate their translation in that it embodied the meaning of the text. The material evidence was generally selected as a record or partial representation of practice.

In Category B the OPP was demonstrating professional practice, and participants used questions as a boundary object. For some the interrogation was of their practice – they were analysing and explaining activities, a module, a class, an assessment, etc. Others gathered physical evidence which also had mediating effects, with one participant commenting:

I needed to go through those processes [of evidence collation] to get to this because the more I thought about it and the more I gathered stuff, then I felt comfortable doing the writing. And I think if you don’t have those things then I couldn’t have just sat down and do this [writing].

One participant’s portfolio narrative changed considerably after she submitted an initial draft which read largely as a list of relevant activities. After reading the feedback she received she said:

I then thought OK they’re [the feedback] questions – because that’s what I do, I ask my students questions! And that’s what it was, it was questions, and you think OK I can answer the questions now.

For participants in Category C the OPP was one of authenticating professional competence. For this to align with successful transfer of learning would require that the material evidence is the boundary object. As Butterworth (Citation1992) noted, this is more likely to happen in contexts where technical competency can be shown through products and practices, for example in vocational qualifications. This OPP is relevant where there is a process of direct learning transfer rather than translation, and does not generally work well for more tacit professional learning. Paulette was frustrated by the limitations imposed on her by the tabulated format of the university proforma, which appeared to require the evidence to authenticate competence. Emilie was also seeking evidence that would authenticate her competence (which often it could not easily do). Bella’s problematisation of the process meant that if there was no material evidence she was silenced. This left them all feeling angry and frustrated.

The different OPPs which characterised how participants understood and experienced the RPL process can broadly be categorised as:

articulating professional learning – where do I?

demonstrating professional practice – why do I?

authenticating professional competence – what do I?

The first two categories offered more opportunity for an agentic process and a positive RPL participant experience. The study also helped to unpack the observation in Pokorny (Citation2013) that evidence was important to RPL participants by showing that evidence can be an important catalyst for writing and reflection. In Pokorny (Citation2013), the tutor conceptualised evidence solely as authentication and commented:

Appendices to me aren’t overly important but I think to the student they are very important … I very much trust the people we have. I do believe if they said they’ve done it they’ve done it. (Pokorny Citation2013, 532)

represent or illustrate practice

verify or authenticate competence

be a catalyst for interrogation of practice

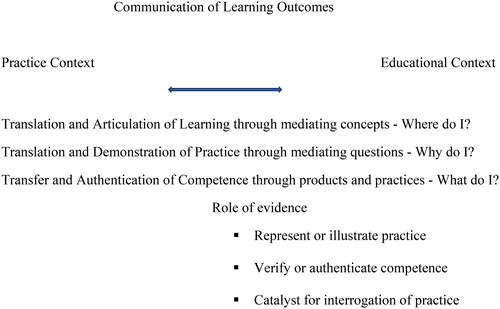

There were many examples throughout the data in Categories A and B of new learning which was valued by participants as they encountered educational concepts or developed new perspectives on their practice. This suggests that there may be some overlap with experiential learning models. However, it is important to note that the participants’ RPL focus was on making explicit their situated learning through a boundary object. The findings from the data can be brought together in a new conceptual model as shown in , that positions RPL as a pedagogy of learning translation and transfer, and outlines the different roles that evidence can play.

The potential benefit to the RPL practitioner in using this model as a heuristic for RPL design is to provide a framework to facilitate the translation/transfer process. The two-way arrow indicates the need to communicate across different social worlds. The model recognises that some skills and knowledge may directly transfer across contexts whilst others require mediation and translation. It is important that RPL practitioners and policy makers conceptualise and clearly articulate the pedagogic aims and strategies of their RPL processes for all participants. These are set out in .

Table 3. RPLTT pedagogic aims and strategies.

suggests that the RPL processes they design should align with these aims and broad strategies because these are the OPPs and boundary objects that determined the subsequent problematisation and activities of participants, forming the immutable reality of their RPL process, shaping their actions and experience of the process.

The subjectivities of the RPLTT model that emerged through the data were summarised in a typology shown in . These shared understandings around the role of evidence and how participants interpreted and experienced RPL – its objectives, motivations, drivers, effects and identity impacts – broadly reflect the realities of the RPL experience for participants in different categories. They are not neutral and have implications. The RPLTT model and the typology of its pedagogic features can help RPL practitioners to design the conditions for supporting RPL in their own context.

Many participants initially undertook RPL for instrumental reasons, seeing it as a quicker and more flexible route to gaining credit than formal study. This acceleration is important particularly for part-time students, and one can see how the transfer approach would appear to be the most straightforward and instrumental approach to RPL. However, this study has shown that this is not necessarily the case, and it may have negative outcomes for participants.

Conclusions and applications

There are limitations to this study. The sample was small and predominantly female. Research has not been undertaken to see if there are gendered, ethnicity or other patterns of inclusion/exclusion that can be identified. The participants were all academics in a single location. However, there was also a potential benefit to participants being higher educators. They thought about what they were doing and were willing to articulate this. As one participant told me ‘[RPL] is a practice so you need to understand what it is you are trying to do’.

Using pertinent ANT concepts in this study resulted in a rewarding, visible and generative method of analysis. ANT fitted easily with what participants experienced and provided a clear explanation of the data. It demonstrated not only what and how participants did RPL but also explained why they did what they did.

Whilst not a panacea or toolkit, the RPLTT model does point to ways in which RPL practitioners can exercise their professional artistry and develop a specialised pedagogic practice to facilitate RPL in the higher education system (Pokorny Citation2021).

The RPLTT model has been applied in practice; for example, in an undergraduate award in Leadership and Professional Development (Pokorny, Fox, and Griffiths Citation2017). The curriculum was designed to award two-thirds of the credit (equivalent to years 1 and 2 of a full-time degree) by RPL. The aim of the RPL process was to translate prior professional learning using a combination of articulation and demonstration strategies. Cohorts came together for four one-day workshops over a three-month period to discuss a range of concepts around business and leadership and how these appeared (or not) in their practice. These workshops were a key motivator for participants who started to see themselves as students on a journey with other equally skilled and knowledgeable peers. The result was three narratives framed around specific questions that encouraged interrogation and articulation of specific aspects of practice, with evidence attached to represent or illustrate their claim. The final workshop guided participants through an additional piece of work that was rooted in their practice and required reading and bibliographic referencing. This acted as a bridge into the final year of formal study.

Thus, the RPL framework addressed some of the issues involved in awarding credit for prior learning, whilst preparing participants to join a qualification with advanced standing. Students moved directly onto the final level of the programme as a cohort. Part-time students have successfully graduated from this course over a number of years with negligible drop-out, excellent degree outcomes, and high levels of reported student satisfaction. As one student stated, ‘It allowed me to take decades of professional experience and transfer it into a recognisable academic qualification… priceless’. This RPL framework has been rolled out to other part-time degrees for mature students. (Pokorny and Fox Citation2019).

It would be useful to explore the application of both the research methodology and RPLTT model in other contexts, including those encompassing wider life experiences and the social justice agenda which to date has been less successfully integrated into RPL in higher education than has work-based learning (Starr-Glass Citation2002, Starr-Glass and Schwartzbaum Citation2003, Peters Citation2005, Harris Citation2006).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Helen Pokorny is a Learning and Teaching Specialist and Academic Development Lead (Apprenticeships & Professional Programmes) at the University of Hertfordshire, UK. She was previously Assistant Director at University Campus St Albans, a joint venture between the University of Hertfordshire and Oaklands College, Hertfordshire dedicated to providing part-time degrees for mature students.

References

- Brown, J. S., A. Collins, and P. Duguid. 1989. “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning.” Educational Researcher 18 (1): 32–42.

- Butterworth, C. 1992. “More than One Bite at the APEL.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 16 (3): 39–51.

- Callon, M. 1986. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of Saint Brieuc Bay.” In Power, Action and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge?, edited by J. Law, 196–233. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Cooper, L., and J. Harris. 2013. “Recognition of Prior Learning: Exploring the ‘Knowledge Question.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 32 (4): 447–463. doi:10.1080/02601370.2013.778072.

- Cooper, L., A. Ralphs, and J. Harris. 2017. “Recognition of Prior Learning: The Tensions between Its Inclusive Intentions and Constraints on Its Implementation.” Studies in Continuing Education 39: 197–213.

- Cresswell, K. M., A. Worth, and A. Sheikh. 2010. “Actor-Network Theory and Its Role in Understanding the Implementation of Information Technology Developments in Healthcare.” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 10 (67): 67.

- Engeström, Y. 1999. “Innovative Learning in Work Teams: analysing Cycles of Knowledge Creation in Practice.” In Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Y. Engeström, R. Meittinen, and R. L Punamaki, 377–406. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, N. 1994. Experiential Learning for All. London: Cassell Education.

- Fenwick, T. 2003. “Inside out of Experiential Learning: Troubling Assumptions and Expanding Questions.” Keynote Paper Presented to the Experiential, Community, Workbased: Researching Learning Outside of the Academy Conference Proceedings, Glasgow, UK.

- Harris, J. 2006. “Introduction and Overview of Chapters.” In Re-Theorising the Recognition of Prior Learning, edited by P. Andersson, and J. Harris, 31–51. Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE)

- Harris, J., M. Breier, and C. Wihak. 2011. Researching the Recognition of Prior Learning: International Perspectives. Leicester: NIACE.

- Hillman, N. 2021. “A short guide to non-continuation in UK universities, Higher Education Policy Institute Note 28.” https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/A-short-guide-to-non-continuation-in-UK-universities.pdf

- Hubble, S., and P. Bolton. 2022. “Part-time undergraduate students in England: Research Briefing 7966, 13 April”, House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7966/CBP-7966.pdf

- Klein-Collins, R., J. Taylor, C. Bishop, P. Bransberger, P. Lane, and S. Leibrandt. 2020. “The PLA Boost: Results from a 72 -institution targeted study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes”. USA, Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL). https://www.cael.org/news-and-resources/new-research-from-cael-and-wiche-on-prior-learning-assessment-and-adult-student-outcomes

- Kolb, D. A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Latour, B. 1999. “On Recalling ANT.” In Actor Network Theory and After, edited by J. Law and J. Hassard, 15–25. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers/The Sociological Review.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maurer, M. 2021. “The ‘Recognition of Prior Learning’ in Vocational Education and Training Systems of Lower and Middle Income Countries: An Analysis of the Role of Development Cooperation in the Diffusion of the Concept.” Research in Comparative and International Education 6 (4): 469–487.

- Michelson, E. 2006. “Beyond Galileo’s Telescope: Situated Knowledge and the Assessment of Prior Learning.” In Re-Theorising the Recognition of Prior Learning, edited by P. Andersson, and J. Harris, 141–162. Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE).

- Miettinen, R. 2000. “The Concept of Experiential Learning and John Dewey’s Theory of Reflective Thought and Action.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 19 (1): 54–72.

- Peters, H. 2005. “Contested Discourses: Assessing the Outcomes of Learning from Experience for the Award of Credit in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (3): 273–285.

- Pokorny, H. 2013. “Portfolios and Meaning-Making in the Assessment of Prior Learning.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 32 (4): 518–534.

- Pokorny, H., S. Fox, and D. Griffiths. 2017. “Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) as Pedagogical Pragmatism.” Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning 19 (3): 18–30.

- Pokorny, H., and S. Fox. 2019. “Developing the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) using SEEC credit level descriptors”. The impact of the SEEC Credit Level Descriptors: Case Studies. https://seec.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/The-impact-of-the-seec-credit-level-descriptors-case-studies-2019.pdf

- Pokorny, H. 2020. “Researching APEL Routes to Becoming Professionally Recognised as a Teacher in Higher Education.” DProf diss., University of Westminster, London.

- Pokorny, H. 2021. “Recognising Prior Learning.” In Enhancing Teaching Practice in Higher Education. 2nd ed., edited by Pokorny, H. and Warren, D. 96–97. London: Sage.

- Schatzki, T. 2002. The Site of the Social: A Philosophical account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Star, S. L., and J. R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology 1907-39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420.

- Starr-Glass, D. 2002. “Metaphor and Totem: Exploring and Evaluating Prior Experiential Learning.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 27 (3): 221–231.

- Starr-Glass, D., and A. Schwartzbaum. 2003. “A Liminal Space: Challenges and Opportunities in Accreditation of Prior Learning in Judaic Studies.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 28 (2): 179–192.