Abstract

Assessors’ perspectives on their evaluative practices remain relatively under-researched. Given evidence that higher education assessment and feedback continue to be problematic, this paper proposes a specific methodological innovation with potential to contribute both to research and practice in this area. It explores the potential of a micro-analysis of textual engagement, nested within an ethnographic approach, to defamiliarize the often taken-for-granted practice of marking. The study on which the paper is based used screen capture combined with audio-recorded, concurrent talk-around-text to throw light on the processes, strategies and perspectives of eight teachers within one university as they assessed undergraduates’ work. This close-up focus was nested within broader ethnographic data generation incorporating interviews, marked assignments and other assessment-related texts. The paper presents selected ‘moments of engagement’ to show how this methodology can offer a renewed understanding of evaluative literacies as complex, ‘messy’ and shot through with influences invisible in the final assessed text but which may nevertheless be highly consequential. The paper concludes by reflecting on the potential for this type of data and analysis to contribute to assessor development and inform debate about the future of higher education assessment.

Introduction

Assessment and feedback practices in higher education have received a great deal of attention in recent decades with regard to students’ perspectives, although assessors’ perspectives remain relatively under-researched (Evans Citation2013). However, there is evidence that assessment and feedback continue to be problematic from students’ point of view (Neves and Hewitt Citation2021) and at institutional level (Knight and Drysdale Citation2020). Contrasting solutions have been proposed, ranging from large scale replacement of summative assessment with forms of “slow scholarship” (Harland et al. Citation2015) to accelerated, sector-wide innovation in digital assessment (Knight and Drysdale Citation2020; Ferrell and Knight Citation2022). Amidst these calls for change, the complexities of contemporary university teacher-assessors’ practices “at the textface” (Tuck Citation2018) are still relatively poorly understood, suggesting that methodological innovation is required if we are to productively address current and future challenges. The present paper responds to this methodological need by exploring the potential of a micro-analysis of marking using screen-and-audio recordings, nested within an ethnographic approach. It places the work of university teacher-assessors centre stage, examining marking practices as complex evaluative literacies in their own right. The aim is to ask “in what ways can a close-up focus on marking as it happens, in the context of an ethnographic study, throw light on markers’ engagement with the undergraduate written work they assess?” The paper seeks to demonstrate the potential value of this methodological approach towards deepening our understanding of routine but consequential evaluative literacies at university.

The study is influenced by academic literacies research which emphasises that academic study, teaching and research are language and literacy practices (e.g. Turner Citation2011). Researchers in this field seek to empirically and critically explore reading and writing in the academy as situated literacies, rather than generalised skills (Lillis Citation2019), typically adopting context-sensitive, ethnographic orientations and methods and often combining these with detailed attention to language and texts (Lillis Citation2008; Guillén-Galve and Bocanegra-Valle Citation2021). Academic literacies perspectives have had considerable influence on higher education assessment studies in the past 25 years; however, much work on assessment and feedback literacies concentrates on students’ practices. Marking – defined here as incorporating both evaluation and feedback practices, seen from teacher-assessors’ perspectives – is rarely centre stage (Tuck Citation2018).

The empirical study underpinning this paper employed an innovative methodological approach to data generation and analysis to capture precisely what is involved in reading, evaluating and responding to undergraduate assignments. The study used screen capture methods more often employed in studies of L2 student writing (Manchón Citation2022) or professional writing practice (Macgilchrist and Van Hout Citation2011). This was combined with audio-recorded, concurrent talk-around-text (Lillis Citation2008) to throw light on the processes, strategies and perspectives of eight university teachers as they unfolded while assessing students’ assignments. This close focus on engagement with texts was nested within broader ethnographic data generation. The ensuing rich empirical data set throws light on assessment literacies from the perspective of markers. The specific approach in this paper is to highlight selected ‘moments of engagement’ (after “sites of engagement”, Norris and Jones Citation2005) to show how this methodology can offer a means through which to deepen our understanding of evaluative literacies in the education of undergraduates - a key, but relatively neglected, aspect of assessment in higher education. I conclude by reflecting on the potential for this type of data and analysis as a tool both for assessor development and support and to contribute productively to the rethinking of higher education assessment in a period of rapid change.

Approaches to research on marking

Reimann, Sadler, and Sambell (Citation2019) comment on a relative dearth of empirical research focusing on staff assessment literacies rather than those of students. In part, this reflects a major, and welcome, trend in assessment research which foregrounds what students do with feedback (Carless and Boud Citation2018), or in some cases what they do not do (Jørgensen Citation2019). Researchers enacting this conceptual shift away from transmission towards constructivist models of feedback (Carless Citation2022) have increasingly focused on the need to ‘design in’ feedback processes which prioritise dialogue (Hill and West Citation2020) and active student engagement (Parkin et al. Citation2012). While this move towards dialogic assessment is desirable, a great deal of academic time is nevertheless still occupied by marking in the traditional sense where, alongside a summative grade, teachers offer written feedback without further formally ‘built in’ opportunities for discussion (Reiman, Sadler and Sambell 2019).

At institutional level, marking remains a low-status ‘Cinderella’ practice; it is physically and discursively hidden from view, attracts low status (Tuck Citation2018), is frequently outsourced to casualised staff and widely regarded as “onerous” (Knight and Drysdale Citation2020, 59), pointless, or as swallowing precious time better spent on activities viewed as more worthwhile (Stommel Citation2018). Knight and Drysdale argue for digital teaching to “address the balance away from manual marking to high-value tasks like engaging with students” (2020, 58), the implication being that marking does not involve engaging with students. University teachers generally report that they receive little or no formal training in marking, generally learning by picking it up individually (Norton, Floyd, and Norton Citation2019) or through informal socialisation (Orrell Citation2006). Thus, marking continues to be marginalised in research and practice. This is a concern given recent significant technology and market-driven changes in higher education assessment and the prospect of accelerated further change driven by developments in artificial intelligence (Weller Citation2022).

Some recent work has called for greater attention to academics’ assessment and feedback literacies (Carless and Winstone Citation2020); however, empirical work exploring the evaluative literacies of teacher-assessors is still relatively rare. There is therefore little systematic understanding of how this core higher education practice is actually carried out and what sense is made of it by markers themselves (Tuck Citation2012, Citation2018). For example, to what extent is this “manual” (Knight and Drysdale Citation2020) written approach to assessment actually transmission-oriented, rather than interactive? Research using a range of methods has contributed to understanding of two core components of marking: evaluation and feedback generation. With regard to evaluation, research falls broadly into two camps focusing respectively on mental processes (Brooks Citation2012) and on marking as social practice (Tuck Citation2012). Psychologically oriented studies generally rely on quasi-experimental methods such as eye-tracking, stimulated recall and think aloud protocols (Orrell Citation2006; Brooks Citation2012). Orrell (Citation2008, 253) researched marking in more “natural conditions”. Her study nevertheless focused on mental activity, isolating marking from specific teaching and institutional contexts. Quantitative approaches have been used to research issues such as assessor bias in response to typographic presentation (Hartley et al. Citation2006) or the effects of anonymity (Hinton and Higson Citation2017).

Researchers who theorise evaluation and grading primarily as social practices have argued that, rather than focusing in a decontextualised way on marker psychology, it is important to understand “the daily acts of judgment that teachers/academics perform” (Shay Citation2008, 160, my emphasis) and to frame such activity as enmeshed with social, economic, cultural and policy conditions. Studies in this tradition typically use methods such as observation and interviews as well as ‘think aloud’ data. A considerable body of work throws critical light on evaluation and grading processes (Francis, Read, and Melling [Citation2003] on gender; Bloxham, Boyd, and Orr [Citation2011] on the (mis)use of assessment criteria). A key finding articulated by Bloxham (Citation2009) is that university assessment policies are generally based on a techno-rational model of knowledge which belies the complex and messy reality of judgment-making and grading. Thus, institutional claims to fairness and robustness may exaggerate the capacity of universities to assess all students objectively. In most studies of evaluation and grading, the precise nature of reading what is to be evaluated (whether writing, graphics and images) is even less visible. This suggests a need for methodologies which capture the ephemeral aspects of the marking process.

Marking as a process of feedback generation is relatively unexplored, though with some recent exceptions (Norton, Floyd, and Norton Citation2019; Reimann, Sadler, and Sambell Citation2019). Practices of textual annotation in disciplinary (rather than language) assessment are seldom discussed. Research on feedback has generally focused on the nature of written feedback comments rather than on the “messy” (Shay Citation2008; Gravett Citation2022) and fluid practices through which such comments are formulated. Recent work from a socio-material perspective has explored university teachers’ feedback literacies (Tai et al. Citation2021). Human participants are analytically decentred in this approach, viewing practices as assemblages of the human/non-human, embodied/discursive and historically shaped/emergent. The current paper recognises the complex materiality and emergent nature of evaluative literacies. However, the study also attended to practitioners’ lived experience of marking in the context of their working, and non-working, lives. The paper illustrates how the hidden literacy events and nested actions involved in undergraduate assessment can be captured ‘as they happen’. This affords a defamiliarized and messier (Gravett Citation2022) view of marking practices while giving voice to markers’ perspectives as they carry out this “mundane, often overlooked” practice (Shay, Ashwin, and Case Citation2009:373).

Methodology and methods

The ethnographic orientation of this study entailed using multiple data sources to build “thick descriptions” of textual practice (Tardy Citation2022), with reflexive attention paid to ways in which the conditions of the study shaped data generation and its interpretation. As part of this context-sensitive approach to marking practices, the study paid close attention to the ways in which written language is both produced (in feedback) and taken up (in evaluative reading and judgment) by markers. Analytically, specific instances of students’ and markers’ language use were linked to markers’ perspectives on these instances, as marking unfolded in micro time on the electronic page. The aim was to explore how markers themselves made sense of and responded to features of students’ texts, throwing light on what was relevant to their “specific acts and practices” of evaluation (Lillis Citation2008: 381). To achieve this, screen capture data were analysed qualitatively, alongside the broader ethnographic data set, to obtain a detailed picture of the ways in which texts were being consulted and constructed verbally and multimodally. This approach allowed the study to address not only what remained in the text but also to reveal ephemeral aspects not visible in the final text or grade.

Data generation

Eight markers were recruited for the study from three Level 1 modules in business and management (4), applied linguistics (3) and health and social care (1). Markers were recruited to the study via module tutor forums. Students were then invited to join the study through the mediation of tutors who posted the researcher’s invitation to participate and study information sheet on their small (20–25) tutor group forums. Student participation was limited to giving written consent for their assignments to be included in the study. All students and markers gave informed written consent and the study received approval from the institution’s research ethics body. One continuously assessed assignment was selected from each module, based on the timing of the study. gives details of module, participants and assignments marked.

Table 1. Modules and assignments in the study.

The institution adopts a supported distance learning model for undergraduate tuition where both students and associate lecturers (tutors) work from home. Attendance at group tutorials, whether face-to-face or online, is optional, so assessment and feedback may be the main point of tutor/student contact. Associate lecturers (here, tutors T1–T8) are responsible for all continuous (non-computerised) assessment for their group of 20–25 students, though many have multiple groups. Assessment is not anonymous; typically, students receive on-script comments and a separate feedback summary from their tutor using a proforma generated by the institution’s marking software. Participants were asked to mark authentic assignments adopting their usual approach as far as possible. summarises data generated.

Table 2. Data generated/gathered for the study.

For the screen capture element of the study, Screencast-o-Matic Pro© was chosen because of its simplicity and flexibility (Séror Citation2013). Participants were trained in the use of the tool through an online briefing and bespoke instruction video. They recorded their script marking whenever convenient, in authentic home-working conditions. All managed to record their marking of between two and six assignments. Selected episodes from the screen-and-audio recordings were then followed up in interviews using screenshots as prompts. Interviews and screencast recordings were transcribed to aid analysis. This detailed approach using multiple sources of data including 25 hours of screen-and-audio recordings resulted in a substantial data set, enabling a slow and deep dive into marking practices in one institution.

A number of specific ethical and validity issues are worthy of comment here. Séror (Citation2013) claims that screen capture is relatively unobtrusive. However, as with ‘think aloud’ research, there is potential for intrusion despite attempts to capture marking in an authentic context. One participant mentioned experiencing extra ‘cognitive load’, for example. Another commented: ‘It really made me think about what I was doing’ [T1]. However, there was no indication that participants substantially altered their practices for the recording. Moreover, the study did not seek to capture what participants were ‘really’ thinking: rather, their talk was analysed as discourse. The use of concurrent ‘talk around text’ (Lillis Citation2008) was beneficial in that it allowed the capture of more ‘in the moment’ responses to specific instances of language use, without the drawbacks associated with later recall.

Data analysis

Verbal transcripts were inductively coded for initial data familiarisation (Braun and Clarke Citation2021), using as a starting point a broad, three-part framework of reading, writing and judgment-making, informed by the theoretical orientation of evaluative literacies. Data from multiple sources were iteratively read alongside one another to identify patterns and to build case studies of individual participants (not presented here). Subsequently, guided by emerging themes, short excerpts of the screen recordings were selected for fuller transcription using an adapted form of mediated discourse analysis (MDA), structured around ‘low-level’ micro actions (Norris Citation2011). The resulting focus on moments of engagement drew on the MDA concept of “sites of engagement” (Norris and Jones Citation2005). This paper focuses on these moments and what they can reveal, rather than on the broader thematic or case study analysis undertaken. However, in keeping with mediated discourse analysis and with the ethnographic orientation of academic literacies research, they were not treated as isolated moments but analysed in the light of multiple sources of data generated in relation to the relevant study participant.

Moments of engagement

This section describes four ‘moments of engagement’, each from a different marking event. These have been selected to exemplify the insights afforded by the study’s approach, ‘slowing down’, and hence defamiliarizing, the act of marking through detailed discourse analytical transcription.

Moment 1: ‘reassurance’

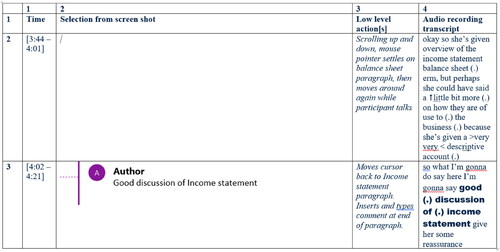

Moment 1 occurs early in the marking of a business and management assignment (see ). Marker T1 has already commented for the audio recording that this script is from a ‘troubled’ student and has ascertained that the (incomplete) assignment was submitted five minutes before the deadline. captures actions surrounding the addition of one marginal feedback comment.

What is revealed here is that the marker’s spontaneous initial response to the student’s answer is transformed into something quite different in written feedback. A ‘very, very descriptive account’ [Column 4 Row 2] becomes a ‘good discussion’ [Columns 2 and 4, Row 3]. Concurrent ‘talk-around-text’ suggests the reason for this shift: the marker wants to give the student ‘reassurance’ [Column 4 Row 3]. Thus, a marginal written comment is revealed as being oriented more towards the student than to the text itself. This prioritisation of feedback as a response to students and their circumstances rather than to assignments per se is borne out in the broader data set for this participant who, while marking, frequently focuses on students’ lives and struggles. For example, in the screen recording for another script, they comment ‘the back stories of these students are so, so important’. T1’s priority orientation towards the student carries through into later comments on this script and to an exchange in which T1 ‘offer[s] … reassurance’ to the student that this assignment ‘isn’t to everyone’s taste’, and, finally, to grading of the one completed question (of three) which they give 18 out of 20. Moments after the extract in , T1’s orientation to the student appears to cause them not to add a comment. They notice some errors, flagged through the spell checker function, but decide that, even though the student’s ‘grammar needs to be looked at’, they ‘don’t like to say that now because I’m being very pedantic… to have done this first question, I think for her was very good’.

Moment 2: ‘the tick’

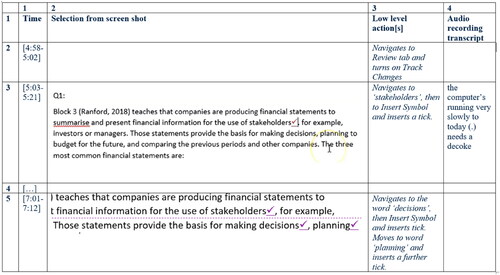

The second moment selected here also relates to the business assignment (see ). T4 is focusing on the 56-word introductory paragraph a student has written to Question 1.

shows T4 inserting several ticks, first after ‘stakeholders’ [Columns 2 and 3, Row 3], then returning two minutes later to the same paragraph to insert ticks after ‘decisions’ and ‘planning’ [Columns 2 and 3, Row 5]. To insert ticks, T4 always navigates to ‘Insert’, then to ‘Symbol’, and selects the tick symbol from the ‘frequently used’ list (rather than, say, using a shortcut key). This takes several seconds each time, with large cursor movements from the assignment to the toolbars and back [Column 3 Rows 3 and 5]. T4 uses ticks liberally in all the assignments marked for the study. Analysis of the wider data set suggests that they do so despite viewing the use of ticks as controversial. For example, in the feedback summary for every student T4 writes: ‘as usual ticks in the text mean ‘relevant point noted’ rather than ‘this is correct’. At interview, T4 explains that they include this standard caveat in feedback every time because ‘if I say ‘this is correct’, people will start… over-interpreting [the ticks]’. They explain this standard comment is not only for students but also for ‘monitors and managers… because I’m thinking somebody else might be reading this feedback, I’d better make it clear’. Later, T4 explains that because of their physical home-working set up, their mouse is on a tilted flat-lap pad on their knee as they work. This means that ‘it’s always in [their] hand’ (to prevent it sliding away) so while they read, T4’s mouse is continually poised over the text. This might help to explain their frequent use of this symbol.

Moment 3: ‘the puzzling reference’

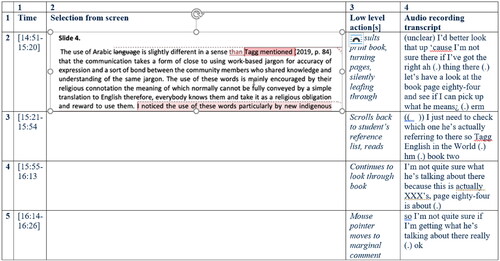

The third moment selected involves T5, marking an applied linguistics assignment consisting of a set of presentation slides and a written ‘script’ of the accompanying talk (see ). T5 has several documents open on screen, including both parts of the assignment, and navigates between them. The extract in begins at the point where T5 is trying to make sense of an in-text citation in the student’s script. This triggers an attempt not only to locate the relevant reference, but to try to work out what the student is saying in the paragraph as a whole.

The transcript shows T5 moving back and forth between the module materials in hard copy [Column 3 Rows 2 and 4] and the student’s assignment [Column 3 Rows 3 and 5], as well as scrolling within the assignment to the student’s reference list and back to the in-text citation [Column 3 Rows 3 and 5]. This absorbs several minutes before they write a marginal comment querying whether the correct reference has been used (this occurs just after the moment represented in ). T5 continues to puzzle for several more minutes over the student’s meaning. Eventually, they heavily edit the original comment to reflect a revised interpretation of the reference but are still unsure whether they have understood the student’s intended meaning. This single query takes over six minutes, without resolution; dealing with the paragraph in total takes over ten minutes. When this moment is explored at interview, T5 comments that the student later got in touch to discuss ‘this very thing’.

Moment 4: ‘plagiarism detector’

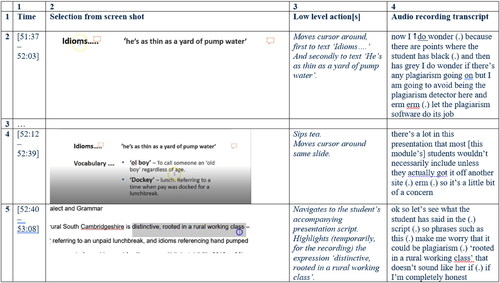

The fourth moment selected captures the work of T7, marking an applied linguistics student’s assignment with the same brief as that shown in Moment 3 (see ). T7 has just added two comments to slide 5 of 9 in the student’s powerpoint presentation. The extract in begins over 50 minutes into the marking time for this script. Earlier, T7 identified some formatting inconsistencies but they decided at that point ‘not to go on a plagiarism adventure’. T7 has also commented for the recording on the student’s use (on an earlier slide) of an ‘unfamiliar’ word, the linguistic term diphthong which, given that it is not taught on the module, makes T7 ‘worry’ about the student’s use of sources. These concerns about source use resurface in Moment 4, as shown in .

The transcript shows T7, like T5 in Moment 3, navigating between slides and script [Column 3 Row 5]. Later in the recording, T7 comments that they plan to Google some of the phrases the student has used, and so will go on the ‘plagiarism adventure’ after all. T7 reads a perceived difference in font colour (grey and black) as a possible indicator of plagiarism on the slide [Column 2 Row 4]. T7’s reading here may be ‘primed’ by earlier concerns raised by inconsistent formatting on a different part of the student’s assignment. This concern seems to carry across to T7’s uptake of the presentation script where the student’s use of the phrase ‘rooted in a rural working class’ is read as a possible indication that the student is plagiarising [Column 4 Row 5]. The final text of feedback on the assignment includes comments which encourage the citing of sources and the use of module materials, but no comment is made about the use of this particular phrase, and no reference is made to plagiarism.

Methodological insights

What types of insight can this approach offer towards deepening our understanding of markers’ engagement with undergraduate assessed written work? Transcribed moments of engagement reveal the potential slippage between a marker’s initial response and its final version as crystallised in written feedback, as well as throwing light on the possible motivations for such shifts. Moment 1 provides a clear example of this, where T1’s reading of the student’s text shifts in the process of entextualisation as a result of their ‘reading’ of the student and their desire to ‘reassure’ a student who seems to be ‘troubled’ and to avoid being ‘pedantic’. Moment 4 exemplifies how participants often ‘read’ certain textual features as indexing negative student behaviours (such as plagiarism or failure to read feedback), but consciously refrain from commenting.

The labour-intensive nature of reading, annotation and feedback is made highly visible in the screen capture recordings. Moment 3 illustrates just one of many moments across the data for all participants where markers engaged in great detail with a small chunk or feature of a student’s text. Puzzling to make sense of a wording or reference led to a trail of clues which might be followed for minutes. Moment 4 shows how T7 routinely spends time tracing students’ sources if they are not recognisable or if wordings do not seem to ‘sound like’ a student’s own. These and other ‘moments’ in the study afford a glimpse of the tutor-assessors’ experience which helps to empirically ground frequent references in assessment research to the time-consuming nature of marking.

A related aspect of evaluative reading revealed through these ‘moments’ is the high degree of non-linearity, even when marking highly successful scripts. As Moment 3 reveals, the reading process can be more akin to a form of ‘puzzling through’ the text than any form of linear reading. Moment 2 reveals how the evaluative reading process can be extremely non-linear as T4 returns to the same paragraph to add more ticks, and where each of the many ticks involves sweeping movements of the cursor across the screen and back. At interview, T1 (also seen in Moment 1) captures the difference between the linear expectations markers (and others) may have of reading for assessment and the bumpier reality and its possible consequences for grading:

If I can’t read it or it doesn’t make sense, paragraphs are too long or they haven’t used full stops, I will subconsciously mark it down… if they’ve used long sentences – long sentences is another one – woo woo woo [tracing the imaginary text using a finger and gaze, mimes reading a long sentence line after line]… it makes you go back… what are they trying to say here, you know?

Another significant area of tension revealed through the analysis of moments of engagement was tutor-assessors’ need to simultaneously address different audiences as they write feedback. This is demonstrated in Moment 2 where T4 consciously words feedback to students in order to clarify their approach for monitors. Addressivity may be rendered more complex by the need to reconcile different functions of feedback, for example the need to encourage as well as judge as shown in Moment 1. The approach explored in this paper allows us to see the complexity of this ‘delicate balancing act’ (T7) as it unfolds.

Discussion

This exploration illustrates the value of the attempt to close “the gap between text and context” (Lillis Citation2008) to defamiliarize an assessment practice such as marking, in this case through the close-up analysis of ‘moments of engagement’ within a broader ethnographic study. The approach explored here permits exposure of the complex practices which lie behind sometimes brief and unremarkable comments and annotations, and points to intangible influences on grading, revealing what is invisible as well as accounting for what is visible in the final grade and feedback. The main purpose here is not to comment in depth on empirical findings in relation to the marking practices in the site institution, nor is it to judge participants’ practice – all were experienced, highly competent and committed educators. Rather, the aim is to show how this approach, combining both context-sensitive qualitative methods with language-sensitive, detailed analysis, offers a view of marking not usually available or systematically understood.

What is happening may even go unnoticed even by markers themselves: at interview, T4 described watching the screen recording: ‘being able to see the mouse going up and down and up and down and up and down the page… I had no idea I was doing that!’ The methodology adopted allows us to consider aspects of practice which rarely receive empirical attention: markers’ responses which do not remain visible in the final feedback text; the complexity, non-linearity and messiness of the literacy labour involved; the often decidedly ‘bumpy’ reading experience which runs counter to readers’ expectations in a “writer-responsible” (Hinds Citation1987) academic rhetorical culture; and the navigation of tensions around readership and purpose. We see the ways in which precise technical affordances, or the perceived affordances, of specific software influence the marking process as it happens and the moment-by-moment decisions which determine what is, and is not, included in written feedback.

It is my contention here that such a defamiliarized view of a routine practice, captured through the detailed analysis of moments of engagement, can help to throw light on some of the persistent challenges associated with assessment in higher education, for example the challenge of making marking judgments ‘objective’ and reproducible. Moments of engagement reveal, for example, that readings of texts were tangled up with ‘readings’ of students (as in Moments 1 and 4). While there have been calls to conceptually and practically ‘disentangle’ the distinct purposes of assessment and feedback (Winstone and Boud Citation2022), in many contexts, this ‘entanglement’ remains the challenging routine reality for markers. The study also brings to the fore the complex skill involved in this relatively invisible aspect of academic work, raising questions about how institutions allocate time to and value such labour. It raises questions about the nature of human marking at a time when marking by non-humans is very much on the agenda (Bearman et al. Citation2020). Watching markers working close up and in ‘real time’ also busts the myth of “digital dualism” (Gourlay, Lanclos, and Oliver Citation2015) with respect to staff as well as students’ practices: there is no clear-cut distinction between the human and the non-human – marking practices always involve technologies which play potentially agentive roles. This insight may help to inform future debates about when and how it may be helpful to assess students’ work using AI, and what may be lost in the process.

As reflected in earlier studies (Norton, Floyd, and Norton Citation2019) none of the participants could recollect formal training or development in marking, as opposed to informal mentoring or moderation. Unsurprisingly, then, some study participants expressed a desire to find out what other markers were doing, hoping that the study would lead to some ‘tips’ (T2). Such sharing is not always straightforward in the performative conditions of contemporary higher education, so ways of working are often not shared. To illustrate with an example from this study, one participant commented at interview on the process of screen recording their marking practices for the study: ‘when I was doing the recordings… I was very much ‘shall I just hide this?’ ‘cause somebody… would probably think I shouldn’t be doing it that way’. This points to the potential practical value of using screen capture data in combination with supportive, context-rich developmental conversations (or even for individual professional reflection).

It also has potential as a peer support tool, similar to the much commoner practice of peer classroom observation, as a way of exploring relatively hidden and individual aspects of marking practice. Tutor-assessors could share time-saving strategies, compare the benefits of different reading pathways, comment on technological affordances that could be more effectively exploited or learn from each other’s practices around grading and feedback. These small details about how someone works, or could work differently, are unlikely to come up without the sort of ‘live’ recording and subsequent reflexive conversations which occurred in this study. This offers a means of professional sharing about an aspect of practice which may feel, and often remains, intensely private.

In addition, those who design assessments – especially if they do not themselves do the marking which such assessments generate – could learn from such data about what aspects of assessment design create practical difficulties for markers, or which make the experience of marking more positive and less draining. Thus screen-and-audio recording of marking has potential not only as a research methodology for deepening our understanding of this practice but as an academic development methodology.

Finally, this paper contributes to the argument that we need to know more about marking in the context of the contemporary university. This study was conducted in one university with very specific conditions and contexts for markers: the supported open and distance learning model of this institution may mean a higher than typical level of teacher-assessor engagement with undergraduate assignments. More empirical research is needed which defamiliarizes this pedagogic practice so that we can work towards keeping and growing what is valuable, freeing up time for positive, formative, human assessment interactions while finding appropriate ways to leverage technologies to create efficiencies. A clear next step will be to report on the broader empirical findings from this study, before expanding the enquiry across different institutions and disciplines.

The close-up analysis illustrated here through ‘moments of engagement’ also opens up potential for theoretical development in the field of evaluative reading and literacies, bringing dynamic forms of discourse analysis to bear on the study of assessment practice. As a starting point, the analysis points to divisions of assessment labour that are based on an understanding of the complexity and importance of human, interpersonal marking interactions (Harland et al. Citation2015), as well as on the need to harness digital technologies effectively to support assessment throughout the sector (Knight and Drysdale Citation2020). Wherever the balance lies, it is essential to study, acknowledge and embrace the complex mixture of functions, priorities and practices which marking involves.

Ethical declaration

This research received favourable opinion from the Open University’s research ethics committee: reference HREC/3884/Tuck. The author has no conflict of interest. The project was supported with internal research development funding (Faculty of WELS) at the Open University.

Notes on contributors

Jackie Tuck is a Senior Lecturer in English Language and Applied Linguistics at the Open University, UK. Her research brings an ethnographic, social practices lens to the study of literacies, pedagogies and language work in academia. She is particularly interested in throwing light on the complexity of “hidden” literacy practices and events which play a huge but take-for-granted role in higher education.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following colleagues for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper: Jane Cobb, Lynn Coleman, Maria Leedham, Julia Molinari.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bearman, M., and R. Luckin, et al. 2020. “Preparing University Assessment for a World with AI: Tasks for Human Intelligence.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, 49–63. Cham: Springer.

- Bloxham, S. 2009. “Marking and Moderation in the UK: False Assumptions and Wasted Resources.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (2): 209–220. doi:10.1080/02602930801955978.

- Bloxham, S., P. Boyd, and S. Orr. 2011. “Mark my Words: The Role of Assessment Criteria in UK Higher Education Grading Practices.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (6): 655–670. doi:10.1080/03075071003777716.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Doing. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Brooks, V. 2012. “Marking as Judgment.” Research Papers in Education 27 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1080/02671520903331008.

- Carless, D. 2022. “From Teacher Transmission of Information to Student Feedback Literacy: Activating the Learner Role in Feedback Processes.” Active Learning in Higher Education 23 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1177/1469787420945845.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Students’ Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., and N. Winstone. 2023. “Teacher Feedback Literacy and Its Interplay with Student Feedback Literacy.” Teaching in Higher Education 28(1): 150–163. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372.

- Evans, C. 2013. “Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education.” Review of Educational Research 83 (1): 70–120. doi:10.3102/0034654312474350.

- Ferrell, G., and S. Knight. 2022. Principles of Good Assessment and Feedback. Bristol: JISC. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/principles-of-good-assessment-and-feedback.

- Francis, B., B. Read, and L. Melling. 2003. “University Lecturers’ Perceptions of Gender and Undergraduate Writing.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (3): 357–372. doi:10.1080/01425690301891.

- Gourlay, L., D. M. Lanclos, and M. Oliver. 2015. “Sociomaterial Texts, Spaces and Devices: Questioning “Digital Dualism” in Library and Study Practices.” Higher Education Quarterly 69 (3): 263–278. doi:10.1111/hequ.12075.

- Gravett, K. 2022. “Feedback Literacies as Sociomaterial Practice.” Critical Studies in Education 63 (2): 261–274. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1747099.

- Guillén-Galve, I. and A. Bocanegra-Valle, eds. 2021. Ethnographies of Academic Writing Research: Theory, Methods and Interpretation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Harland, T., A. McLean, R. Wass, E. Miller, and K. N. Sim. 2015. “An Assessment Arms Race and Its Fallout: High-Stakes Grading and the Case for Slow Scholarship.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (4): 528–541. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.931927.

- Hartley, J., M. Trueman, L. Betts, and L. Brodie. 2006. “What Price Presentation? The Effects of Typographic Variables on Essay Grades.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 31 (5): 523–534. doi:10.1080/02602930600679530.

- Hill, J., and H. West. 2020. “Improving the Student Learning Experience through Dialogic Feed-Forward Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (1): 82–97. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1608908.

- Hinds, J. 1987. “Reader versus Writer Responsibility: A New Typology.” In Writing across Languages: Analysis of L2 Texts, edited by U. Connor and R. Kaplan, 141–152. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Hinton, D. P., and H. Higson. 2017. “A Large-Scale Examination of the Effectiveness of Anonymous Marking in Reducing Group Performance Differences in Higher Education Assessment.” PloS One 12 (8): e0182711. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182711.

- Jørgensen, B. M. 2019. “Investigating Non-Engagement with Feedback in Higher Education as a Social Practice.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (4): 623–635. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1525691.

- Knight, G. L., and T. D. Drysdale. 2020. “The Future of Higher Education (HE) Hangs on Innovating Our Assessment – But Are We Ready, Willing and Able?” Higher Education Pedagogies 5 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1080/23752696.2020.1771610.

- Lillis, T. 2008. “Ethnography as Method, Methodology and Deep Theorising: Closing the Gap between Text and Context in Academic Writing Research.” Written Communication 25: 353–388. doi:10.1177/0741088308319229.

- Lillis, T. 2019. “Academic Literacies”: Sustaining a Critical Space on Writing in Academia.” Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. doi:10.47408/jldhe.v0i15.565.

- Macgilchrist, F., and T. Van Hout. 2011. “Ethnographic Discourse Analysis and Social Science.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 (1). doi:10.17169/fqs-12.1.1600.

- Manchón, R. 2022. “The Contribution of Ethnographically-Oriented Approaches to the Study of L2 Writing and Text Production Processes.” In Ethnographies of Academic Writing Research edited by I. Guillén-Galve, and A. Bocanegra-Valle, 83–104. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Neves, J., and R. Hewitt. 2021. Student Academic Experience Survey. Advance HE and Higher Education Policy Institute. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/reports-publications-and-resources/student-academic-experience-survey-saes.

- Norris, S. 2011. Identity in (Inter)Action: Introducing Multimodal (Inter)Action Analysis. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

- Norris, S., and R. H. Jones. 2005. Discourse in Action: Introducing Mediated Discourse Analysis. Florence: Routledge.

- Norton, L., S. Floyd, and B. Norton. 2019. “Lecturers’ Views of Assessment Design, Marking and Feedback in Higher Education: A Case for Professionalisation?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (8): 1209–1221. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1592110.

- Orrell, J. 2006. “Feedback on Learning Achievement: Rhetoric and Reality.” Teaching in Higher Education 11 (4): 441–456. doi:10.1080/13562510600874235.

- Orrell, J. 2008. “Assessment beyond Belief: The Cognitive Process of Grading.” In Balancing Dilemmas in Assessment and Learning in Contemporary Education, edited by A. Havnes, and L. McDowell, 251–263. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.1080/13562510600874235.

- Parkin, H. J., S. Hepplestone, G. Holden, B. Irwin, and L. Thorpe. 2012. “A Role for Technology in Enhancing Students’ Engagement with Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (8): 963–973. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.592934.

- Reimann, N., I. Sadler, and K. Sambell. 2019. “What’s in a Word? Practices Associated with “Feedforward” in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (8): 1279–1290. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1600655.

- Séror, J. 2013. “Screen Capture Technology: A Digital Window into Students’ Writing Processes.” ‘ Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology 39 (3): 1–16. doi:10.21432/T28G6K.

- Shay, S. 2008. “Researching Assessment as Social Practice: Implications for Research Methodology.” International Journal of Educational Research 47 (3): 59–164. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2008.01.003.

- Shay, S., P. Ashwin, and J. Case. 2009. “A Critical Engagement with Research into Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (4): 373–375. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2008.01.003.

- Stommel, J. 2018. “How to ungrade.” Accessed February 13 2023. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-ungrade/

- Tai, J., M. Bearman, K. Gravett, and E. Molloy. 2021. “Exploring the Notion of Teacher Feedback Literacies through the Theory of Practice Architectures.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48(2): 201–213. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1948967.

- Tardy, C. 2022. “What is (and Could Be) Thick Description in Academic Writing Research?” In Ethnographies of Academic Writing Research, edited by I. Guillén-Galve, and A. Bocanegra-Valle, 21–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Tuck, J. 2012. “Feedback-Giving as Social Practice: Academic Teachers’ Perspectives on Feedback as Institutional Requirement, Work and Dialogue.” Teaching in Higher Education 17 (2): 209–221. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.611870.

- Tuck, J. 2018. Academics Engaging with Student Writing: Working at the Higher Education Textface. London: Routledge.

- Turner, J. 2011. Language and the Academy: Cultural Reflexivity and Intercultural Dynamics. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Turner, J. 2018. On Writtenness. London: Bloomsbury.

- Weller, M. 2022. “25 Years of Ed Tech: AI Generated Content.” Accessed February 13 2023. http://blog.edtechie.net/assessment/25-years-of-ed-tech-2022-ai-generated-content/

- Winstone, N. E., and D. Boud. 2022. “The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (3): 656–667. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687.