Abstract

With increasing focus on the outcomes of doctoral education, especially regarding employability, we aimed to explore how PhD graduates from humanities and social sciences (HASS), and science disciplines perceived the development of a holistic set of graduate attributes during their doctoral study and the application of these attributes in the workplace. We analysed 136 survey responses and interviews with 21 PhD graduates from one NZ and two US universities. We found that overall, PhD graduates are satisfied with their development as researchers, but had concerns regarding the development of some transferrable skills and attributes. Graduates from the three universities perceived the application of attributes in the workplace similarly. Comparisons of graduate attribute application to their development revealed the following areas requiring better support: teamwork, communication, project management, entrepreneurship, and networking. While development of affective attributes related to global citizenship was lower than expected, graduates perceived these were not always required in the workplace. Universities should consider how their doctoral training programmes can promote a more holistic development of desirable skills and attributes. We provide a possible categorisation to evaluate attainment of desirable attributes for PhD graduates, to ensure researchers and institutions are targeting key attributes.

Introduction

Higher education institutions have paid increasing attention to the outcomes achieved by their graduates, driven by a desire to quality assure degrees, enhance employability of graduates, and ensure curricula are relevant. Graduate outcomes are often estimated through the attainment of graduate attributes, which Bowden et al. (Citation2000, 3) defined as ‘the qualities, skills, and understandings a university community agrees its students would desirably develop during their time at the institution and, consequently, shape the contribution they are able to make to their profession and as a citizen’. Most research on graduate attributes focuses on attainment at undergraduate level, yet many institutions expect doctoral graduates to also achieve these outcomes, albeit at a higher level of ability (Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Mirosa Citation2018).

In a systematic review by Senekal, Munnik, and Frantz (Citation2022, 2), doctoral graduate attributes were defined as the ‘qualities, skills, and competencies that graduates possess, having completed their doctorate degree’. They noted a lack of conceptualisation of doctoral graduate attributes, with most studies using different terms for graduate attributes, as well as using a range of categorisations; few studies drew on existing frameworks. Their analysis of 35 journal articles between 2016 and 2021 identified 10 domains of doctoral graduate attributes: knowledge, research, communication, interpersonal, organisational, scholarship, reputation, higher order thinking, person resourcefulness, and active citizenship. They showed the Vitae Researcher Development Framework (RDF, https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers-professional-development/about-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework) provided the most comprehensive match to the domains of attributes they found, but highlighted some subdomains that were missing, especially related to scholarship and personal resourcefulness. Although their review identified studies including active citizenship attributes, there was no mention of global citizenship, nor were there studies on professional and career development attributes.

Regarding global citizenship, prominent researchers have been calling for doctoral education to generate ‘an awareness and commitment to civic engagement and world citizenship’ (Nerad Citation2005, 9). O’Brien (Citation2011, 42) gave a useful framing of global citizenship attributes that included digital literacy (communicating across media and communication technologies), cultural literacy (approaching and understanding others with greater empathy and sensitivity and an openness to value diverse perspectives), and socio-communicative literacy (negotiating across multiple perspectives from various cultural stand-points). Spronken-Smith (Citation2018) added environmental literacy (sustainability and environmental awareness) as a key aspect of global citizenship. In terms of professional and career development attributes, Seo and Yeo (Citation2020) noted a lack of empirical studies on the career development of PhD students across disciplines and called for further research. It is notable that the Vitae RDF has a subdomain (B3) for professional and career development, which includes career management, continuing professional development and responsiveness to opportunities.

At the time we began our study (in 2018), only sparse research had been reported regarding doctoral graduate attributes across a range of disciplines, and most used quantitative approaches (Manathunga, Pitt, and Critchley Citation2009; Platow Citation2012; Rudd and Nerad Citation2015; Durette, Fournier, and Lafon Citation2016; Heuritsch, Waajer, and van der Weijden Citation2016; Sinche et al. Citation2017; Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Mirosa Citation2018). This research, conducted in the Netherlands, USA, Australia and New Zealand, has used quantitative approaches where PhD graduates or students rate their perception of the development of skills and attributes, and either preparation for work or the application of these skills and attributes in the workplace. Findings from these studies are remarkably consistent: during doctoral study there has been strong development of knowledge, research, communication, scholarship and higher order thinking skills, lower development of organisational, and personal resourcefulness qualities, and poorly developed research management and interpersonal skills. However, Heuritsch, Waajer, and van der Weijden (Citation2016, 748) noted limitations of quantitative data, suggesting future studies should gain qualitative data alongside ratings to provide ‘a more richly textured picture of the experiences of PhDs’.

In more recent years, further quantitative and qualitative studies have been undertaken, but only a few have undertaken research in science and humanities and social sciences (HASS) on PhD graduates from more than one country. McAlpine, Skakni, and Inouye (Citation2021) did an exploratory study on PhD graduates from UK and Swiss institutions who entered non-traditional careers to uncover individual and structural factors influencing post-PhD careers. Although appreciative of learning through the PhD and the opportunities and/or legitimacy this afforded them, some graduates noted a lack of skills and expertise in areas such as financial management, non-academic writing, commercial awareness, and human resource management (McAlpine, Skakni, and Inouye Citation2021, 379).

Our research adds to the sparse literature on the development and application of doctoral graduate attributes, with the major contributions including the use of mixed methods, having questions about global citizenship and professional and career development attributes, focusing on both science and HASS disciplines, and including PhD graduates from different countries. Our research aimed to explore to what extent PhD graduates from HASS and science disciplines in two different countries believed they developed a holistic set of graduate attributes, and how well prepared they felt for the workplace.

Methods

This article stems from a broader study exploring the preparedness of PhD graduates for careers, with research on PhD alumni from three research-intensive universities—two US (USU1 and USU2) and a New Zealand university (NZU). The universities were selected for pragmatic reasons as the lead author (from NZU) visited the US institutions as part of a Fulbright award. While not necessarily representative of all PhD students, the results are likely indicative of beliefs, and provide more in-depth evidence on the topic of graduate attributes than has previously been available. The doctoral education system in New Zealand involves supervised thesis research only, although most universities allow limited coursework (e.g. courses in research or statistical methods), and all have some research training available through workshops and/or online resources. In the two US universities, the PhD programme normally involved two years of coursework, and then supervised thesis research. Like NZ, workshops were available in the US universities to support researcher development. Neither of the US universities had a graduate profile for PhD graduates at the time of the study, whereas the NZU had a graduate profile specifying highly developed research skills and specialist knowledge, alongside 13 other transferable skills and affective attributes: communication, critical thinking, information literacy, self-motivation, teamwork, leadership, ethics, interdisciplinary perspective, lifelong learning, scholarship, and attributes relating to global citizenship (global perspective, cultural understanding, and environmental literacy).

A comparative case study with mixed methods design was used, comprising a US Council of Graduate Schools survey (S. Ortega, pers. comm) and individual interviews. The participants were PhD alumni from the graduating cohorts of 2011/12 and 2016/17 in HASS and science disciplines. The two cohorts were selected so they did not interfere with ongoing outcomes research by the US Council of Graduate Schools. The cohorts were surveyed in 2018, with follow-up interviews with volunteers to gain more in-depth data. The study had ethical approval from the Human Ethics Committee at the NZU (Ref: 17/147), and permission from the participating US institutions.

Approximately 700 alumni were contacted using institutional databases, with 136 relatively complete survey responses obtained (19.4% response rate); 31 from USU1 (22.8% of the sample), 53 from USU2 (39.0%), and 52 from NZU (38.2%). The demographics of the survey respondents are shown in .

Table 1. Demographic details for survey respondents.

The survey was based on the US Council of Graduate Schools PhD Career Pathways survey (https://cgsnet.org/project/understanding-phd-career-pathways-for-program-improvement/), probing the background qualifications of alumni, their current employment and demographic characteristics, and adapted to include reflection on professional development and career development opportunities during their PhD study, as well as skills and attributes fostered during study. The survey collected both quantitative and qualitative data. All respondents gave informed consent and were invited for follow-up interviews. Important for this article were questions about professional development opportunities and the adequacy of these. Lists of possible professional development activities, as well as workshops and courses were provided in the survey, with respondents indicating which activities they had participated in, and how adequate they felt the offerings were using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ‘excellent’ to 5 ‘inadequate’ (or they could indicate ‘don’t know’). Also included in the survey was a list of 20 attributes drawn from the NZU survey for graduates including knowledge, research, higher order thinking, communication, interpersonal, organisational, and personal resourcefulness skills, as well as attributes relating to global citizenship. Respondents were asked to rate to what extent their PhD programme encouraged the development of these, and to what extent they felt they applied each of these in their workplace. Ratings were on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ‘never developed/applied’ to 5 ‘almost always developed/applied’. Descriptive data from the survey were tabulated. For questions generating Likert ratings, averages were calculated. The average ratings of the development and application of graduate attributes were plotted on radar graphs. Chi-square tests were conducted to investigate associations between the three universities and particular measures of interest.

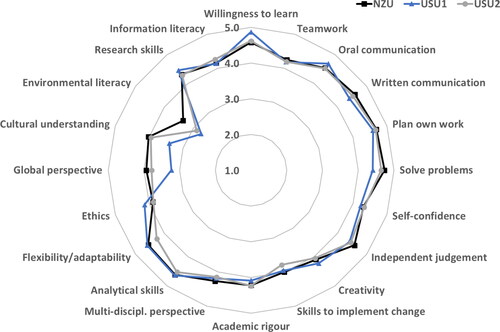

Figure 1. Average ratings of the development (n = 113) and application (n = 109) of graduate attributes across all alumni from the three universities. A rating of 5 means the attribute was ‘almost always’ developed/applied.

Those volunteering for interview were provided with an information sheet and consent form. Twenty-one alumni were interviewed, comprising two from USU1, 10 from USU2 and nine from NZU. Of the interviewees, 13 were female and eight were male, with 13 from HASS and eight from science disciplines. At the time of the interview, nine were doing postdocs, one was an assistant professor, two were tenured faculty, two were academic professionals (student or research support positions), five worked for government, one was in the private sector, and one was unemployed but had run a coaching business. The interviews were semi-structured and asked questions about career pathways and preparedness, the skills and attributes respondents acquired or enhanced during doctoral study, and how they used these in their workplace. The interviews were conducted either face-to-face or via web-conferencing and lasted about an hour. All except one were recorded with participants’ consent. The interview data were initially analysed by the second author using Atlas.ti, with 22 themes generated. Quotes from relevant themes such as career preparation, and those relating to career preparation and transferable skills were extracted to add further depth to the survey findings. Pseudonyms are used, and some details anonymised to protect identities.

Findings

Development of graduate attributes during study

Nearly 80% of the PhD graduates surveyed had worked prior to entering doctoral study: 22.8% reported working part-time, while 55.1% had full-time positions. Consequently, it is likely most already had developed a range of transferrable skills and attributes. However, at least one of the institutions was expecting their PhD graduates to attain advanced abilities in workplace attributes, so the expectation is that experiences during doctoral study would develop and/or enhance key skills and attributes.

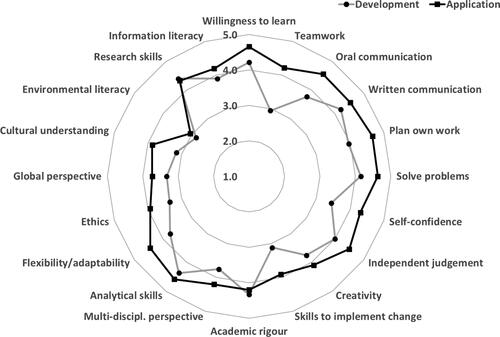

The development of graduate attributes during their PhD programme was perceived by graduates to be very patchy (). The attributes perceived to be the most highly developed are commonly associated with researcher development: research skills (mean score 4.4), analytical skills (4.4), academic rigour (4.3), willingness to learn (4.2), written communication (4.2), problem-solving (4.2), and independent judgment (4.0). The attributes perceived to be the least developed were environmental literacy (2.8) and teamwork (2.9). Other less developed attributes included the skills to implement change (3.1), cultural understanding (3.2), a global perspective, and an awareness of ethical issues and self-confidence (all 3.4).

Although there were similar ratings for the development of core research attributes between the universities (), significant associations were reported in some of the other attributes. More graduates from NZU than expected reported they were ‘often’ encouraged to have a cultural understanding, yet more NZU graduates also said they were ‘never’ encouraged to have a cultural understanding (p = 0.002), suggesting polarised perspectives. More NZU and USU2 graduates were ‘almost always’ encouraged to develop information literacy (p = 0.016), but more graduates from USU1 and USU2 compared to NZU were ‘sometimes’ encouraged to develop information literacy.

Figure 2. Average ratings of the development of graduate attributes across all alumni for the three universities (n = 113). A rating of 5 means the attribute was almost always developed.

Many graduates (122/136) reported undertaking professional development opportunities as part of their doctoral experience. Thirty-seven had engaged with one or two activities, 62 took part in three or four, 22 did five or six, and one had done seven. shows the most common form of participation in professional development activities related to research skill development (80.2%), which included publishing, writing research proposals, generating research posters and completing research ethics. Overall, 64.7% reported working as a paid teaching assistant, with no evidence of a difference between the three universities. About 43% reported working as a paid research assistant, with more than expected (p = 0.009) in that role at USU2 (58.5%), compared to 25.8% and 38.5% at USU1 and NZU, respectively. About 54% participated in teaching, and 43.4% had participated in professional and career development planning. A quarter did an experiential learning opportunity such as outreach, volunteering or an internship, and 41.2% had an international academic experience. Nearly 28% had engaged in networking, but only 14.7% did project management, 8.1% leadership development and a mere 2.9% entrepreneurship (). Respondents from the US universities were more likely to participate in professional development and career development planning activities (p = 0.027), and in teaching activities (p = 0.001). More NZ respondents had an international academic experience (p = 0.007), likely reflecting a policy at NZU whereby every doctoral student can access support to attend an international conference, and travel abroad for field or laboratory work.

Table 2. Professional development activities (not including courses or workshops—see for these) during doctoral study.

Of the 136 respondents, 31 reported not engaging in any of the listed courses or workshops during doctoral study; 65 attended one or two, 25 participated in three or four, 11 engaged in five or six, and four in seven or eight. The highest participation was in courses or workshops developing research skills (72.8%) (), with the most common being academic writing, then teaching skills and/or curriculum design, research methodology and/or methods, publishing research, literature searching and referencing, critically engaging with the literature, and quantitative analysis (breakdown not shown in table). Teaching development workshops or courses were also well-attended by respondents (39.7%). Although 25.7% participated in sessions related to professional and career development planning, attendance was heavily weighted to preparing job applications and/or interviews skills, with few respondents completing a professional development needs analysis, creating a personal development plan, or career planning (data not shown in table). About 28% had been to workshops on oral communication, but only 14.7% attended workshops on working in teams, and there was low engagement with sessions on project management (5.9%), networking (8.8%), leadership development (5.2%), and entrepreneurship (1.5%). The only evidence of a difference in participation between the universities was for courses and workshops in teaching, where more respondents participated than expected from US universities (p < 0.001).

Table 3. Professional development courses or workshops attended during doctoral study.

Application of graduate attributes in the workplace

At the time of the survey, of the 129 respondents who gave employment details, 121 (93.8%) were employed, with 85.3% in full-time work (more than 30 hours per week), and 7.8% part-time. The most frequent job was a fixed-term academic position (33.3%), followed by working for government (17.5%), working in the private sector for-profit (16.7%), tenure-track academic (13.3%), tenured academic (9.2%), private sector not-for-profit (4.2%), academic professional (3.3%), and in education below tertiary level (2.5%).

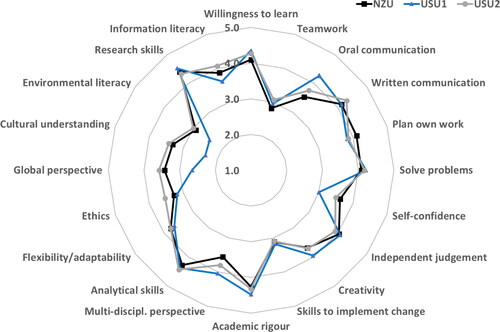

Regarding the application of graduate attributes in the workplace, shows the average ratings across all universities. Most attributes were highly rated except for environmental literacy (mean score 3.0), global perspective (3.7), cultural understanding (3.9), skills to implement change (3.9), and an awareness of ethical issues (3.9). The perception of application of attributes in the workplace is remarkably similar across all university graduates (). Although there are some differences between universities in perceptions of application of the global citizenship attributes such as global perspective, cultural understanding, and environmental literacy, these are not statistically significant.

Perceptions of the adequacy of professional and career development opportunities

Of the 21 graduates interviewed, 11 explicitly discussed how their thesis study had developed attributes that were preparing them for the workplace. Simon (USU2, research analyst in government) said ‘I can’t think of a single thing that I didn’t already get preparation for in terms of just job skills that were very transferable’, while Alice (USU2, postdoctoral fellow) commented ‘I guess essentially everything you do can be translated to some sort of job setting’. Kimi (NZU, lecturer) thought ‘It’s a thinking game… how we see the world and how we prepare ourselves to see the world from others’ views. No matter if you are in academia, in consultancy or in private, the qualification does serve a purpose, it’s just how you transfer the skills being learned to different aspects in life’. These graduates recognised that their doctoral study developed a host of transferable skills and attributes useful to their future employment.

However, the survey and interview data revealed areas where graduates felt they could have been better prepared for the workplace. It was apparent that most professional development opportunities were geared towards supporting thesis research. When asked about the perceived adequacy of professional development opportunities during doctoral study, research skills and oral communication were the most highly rated, with medians of 2 on a 5-point Likert scale (‘reasonably adequate’), except for ‘writing research proposals or grants’, which was rated 3 (). Teaching development was perceived to be ‘adequate’ or ‘reasonably adequate’, but less well rated were support for working in teams, project management, networking, and leadership development. Regarding professional and career development, support for the job application process was rated overall as being ‘adequate’, but support for planning was reported as being ‘somewhat inadequate’. Opportunities for entrepreneurship and commercialisation also received low ratings. Although there was some variation in perceptions of support for professional and career development between the universities, there was consistency in identifying areas of stronger and weaker support ().

Table 4. Perceptions of the adequacy of professional development opportunities during doctoral study according to a 5 point Likert scale.

Graduates reported higher levels of application compared to development of nearly all the graduate attributes; only academic rigour and research skills had higher development levels than application levels (). A comparison of the difference in average ratings between the application and development of graduate attributes reveals limitations in the development of teamwork (1.3 difference in average rating), self-confidence (0.9), oral communication and the skills to implement change (both 0.8).

In alignment with the survey findings, the graduates interviewed identified some limitations in their skills sets and wished there had been better support. The main areas they identified were teamwork, communication skills, and project management and networking.

Eight graduates explicitly discussed teamwork skills. Some of the science graduates expressed how they developed interpersonal skills and teamwork through their doctoral study in research laboratories. However, even these graduates wished they had some formal training for working in teams. For example, Mark (USU2) commented:

I probably got a lot of first-hand experience in that [conflict management] with my research lab, but we had a big kind of collaborative team that we worked with in my own lab, so there was times over the years where personalities kind of conflicted and we had difficult situations… it would be good to have some resources for how to deal with those kind of situations.

Many graduates discussed how they had further developed written and oral communication skills during candidature, and indeed some saw this as a real strength of their PhD. However, a few felt that better training was required to communicate to more diverse audiences. Marty (USU2) commented ‘We couldn’t actually, in my opinion, communicate that [research] to a wider audience. It wasn’t accessible at all… I think we needed technical skills’.

Project management skills were also seen as valuable for the workplace. Although graduates realised they were developing project management skills through their thesis study, they wanted more formal training. For example, George (USU2) said:

As a transferable skill they really tried to get us to understand that writing a dissertation gave us project management skills… But I wish they would have gone into a little bit more detail about what project management is… to be able to talk about those skills and the jargon of project managers.

The other area that rated very poorly in survey data was career development: only two graduates created a personal development plan and only 10 engaged in career planning activities. However, 29 attended workshops on preparing job applications or interview skills. The interview data confirmed that only a few of the graduates had purposefully reflected on their skills sets, values, and employment preferences. Moreover, there was very limited knowledge of career options beyond academia. For example, Simon (USU2) said ‘there’s a default assumption that everybody in the department is going to go into academia’, and Veronica (USU1) reflected:

I was strongly encouraged by my mentors to pursue an academic pathway from undergraduate onward. This was implied to be the only career pathway and/or career pathway for those with the best skills… No one ever discussed any other possibilities.

Regarding developing attributes associated with global citizenship, there were mixed views. When asked whether these attributes should be fostered, Maree (USU2) said ‘it depends on the programme; obviously they are important things—I agree with that. But really the purpose of my PhD is to become an expert in particle physics—not something else’. Simon (USU2) thought global citizenship ‘is firmly in place, almost universally, to begin with. It’s a generational thing… among millennials that desire is already there and it’s not something that needs to be taught’. However, Omar (USU2) thought global citizenship ‘needs to be systematised a little bit better for these conversations to help grow each other, as opposed to consume the consciousness of the department’. There was a sense by all interviewed graduates that global citizenship attributes were important, but some felt they were more relevant to certain disciplines, and rather than teaching as a separate subject, ‘we should be aware of the places where our discipline touches on that’ (Veronica USU1).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine how PhD students developed graduate attributes during their enrolment and to what extent they felt prepared for the workplace.

Satisfaction and support for developing as a researcher

Across the three universities, the attributes perceived by our study graduates to be best developed during their PhD were research-related skills. Graduates recalled developing or enhancing research skills through opportunities that arose during their thesis research, as well as training opportunities such as workshops and courses. The most common activities graduates recalled included publishing, writing research proposals, generating posters and working as a paid research assistant. Discussed in the literature are notions of becoming a scholar or researcher, with studies unpacking aspects of doctoral education that contribute to these identities. Mantai (Citation2017) frames key aspects of researcher development, which include formal research outputs, doing research, and talking about research. Like others (McAlpine, Jazvac-Martek, and Hopwood Citation2009), she noted the importance of ‘formal research outputs’ such as publications and presentations. The ‘doing research’ included the engagement in often mundane acts of research, such as laboratory work, reading articles, collaborating with others, fieldwork and finishing drafts of a paper (Mantai Citation2017, 642).

Desire for better support for some transferable skills and attributes

It was apparent from both survey and interview data that graduates from all universities desired more opportunities to develop specific skills, especially related to teamwork, communication skills, project management, networking, and career development. These findings are well aligned with past research, which has noted limited development of teamwork during doctoral study (Manathunga, Pitt, and Critchley Citation2009; Rudd and Nerad Citation2015; Heuritsch, Waajer, and van der Weijden Citation2016; Sinche et al. Citation2017; Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Mirosa Citation2018), and lower levels of development of communication (Manathunga, Pitt, and Critchley Citation2009; Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Mirosa Citation2018) and project management skills (Heuritsch, Waajer, and van der Weijden Citation2016). Networking and career development attributes have not been found to be important to PhD graduates in past quantitative research, likely because these may not be listed amongst typical graduate profiles. Yet qualitative research has noted the importance of networking (McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2016) and career development (Seo and Yeo Citation2020) in career preparation.

Some areas of professional development support were perceived as limited: professional development needs analysis, career planning, entrepreneurship, commercialisation, leadership, and networking. Past research has queried the value of short-term training. For example, Feldon et al. (Citation2017) found that boot-camps (intense, focused professional development, and usually over several days) and short-format training did not increase skills development, socialisation into the academic community or scholarly productivity. However, others (e.g. Craswell Citation2007) have noted doctoral students may still value these opportunities. Recent research training responding to perceived lack of support for career preparation has focussed on career development, and has been more successful (e.g. Layton et al. Citation2020).

Boosting global citizenship attributes

Graduates across all the universities perceived environmental literacy, cultural understanding, and global perspective to be less well developed during doctoral study, and less applied in the workplace. Yet all interviewed graduates agreed they were important in doctoral education, but mostly in relation to their discipline. Only sparse research has reported on the development of citizenship attributes in PhD graduates. Boulos (Citation2016) noted that social justice can be developed serendipitously through study, in her case through an influential supervisor. But to develop more holistic global citizenship attributes may require participation in volunteering, community-based project work or outreach (Porter Citation2021). However, as Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Cameron (Citation2022) signal, supervisors may need to be educated to allow such participation, as some vigorously discourage activities outside thesis study.

Implications

Given the skills and attributes people bring into doctoral study, coupled with their different employment aspirations, it is important that doctoral education allows a personalised programme of study (Sharmini and Spronken-Smith Citation2020), encouraging PhD students to develop or further enhance desired skills and attributes. Since interests and opportunities in careers extend beyond academia, institutions must broaden professional development beyond research skills and attributes. Areas perceived as needing more support were entrepreneurship and commercialising research, teamwork, communication skills, project management, networking and career development.

If universities value fostering global citizens, they may need to think creatively about how they support students to develop relevant attributes. The provision of high-impact training opportunities through working with external partners is one possibility (e.g. Porter Citation2021), but requires resourcing, and a cultural shift in supervisors to encourage students to participate in such activities.

A common complaint in our study was lack of awareness of career options, the focus of related research (Spronken-Smith, Brown, and Cameron Citation2022). Each university in our study had excellent career services, but these were seldom accessed by PhD students. An embedded personal development plan in PhD programmes could require students to engage with career services and professional development opportunities to develop career competencies and better prepare them for future career pathways.

Our survey drew in part on a pre-existing institutional instrument to evaluate the development and application of graduate attributes. Ideally, a more theoretically-based tool should be developed for researching and quality assuring doctoral graduate attributes. We synthesised our findings with those of Senekal, Munnik, and Frantz (Citation2022) and the Vitae RDF to produce a new tool with seven domains (). Notably, active citizenship is recast as global citizenship to reflect the dynamic attributes related to digital, cultural, socio-communicative, and environmental literacies anticipated in a global employment environment. Furthermore, we think that professional and career development should be more explicit, and included ‘career management’ as a subdomain in ‘personal resourcefulness’.

Table 5. Simplified categorisation of doctoral graduate attributes for research and institutional quality assurance (adapted from Senekal, Munnik and Frantz (Citation2022, 11)).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study was the use of mixed methods, combining survey data to capture a wider range of PhD graduate perceptions about career preparedness, followed by interviews that further explored participants’ perceptions. The comparative case study approach enabled comparisons across universities with different contexts. However, recruitment was challenging, and the sample of PhD graduates from each institution is small, meaning our results should be treated with caution, and may not be generalisable to other cohorts and institutions. The study relied on graduate perceptions, which are inherently individualistic and may be differently interpreted, both in terms of the level of attainment and how they were developed. Indeed, some may not be aware that supervisors or programmes were trying to foster particular attributes. Our survey was limited to a narrow set of graduate attributes. It is possible our responses were biased to those in academic positions, given the stigma associated with PhD graduates leaving academia. Finally, our data collection was pre-COVID-19, and we are aware that during the pandemic the career landscape became more complex for PhD graduates (Spronken-Smith et al. Citation2022).

Conclusions

The overall aim of our study was to explore career preparedness in PhD graduates from science and HASS disciplines in PhD graduates from one NZ and two US universities. Our findings reveal mixed views on the degree of career preparedness in graduates from the three universities. Evidence in support of career preparedness includes the high employment rate in the PhD graduates (93.8%), but it was noticeable that only 22.5% of the surveyed graduates were working in tenured or tenure-track positions in academia. A further 33.3% were in fixed term academic positions and 3.3% in academic professional positions such as research managers, but the remaining 40.9% were working outside tertiary education. Our finding of 59% going into academia is a little higher than most reported research for western nations, but, like others, we found that over half of the graduates in academia were precariously employed.

Many interviewees expressed the transferability of the PhD qualification, preparing them well for employment. Overall, PhD graduates were satisfied with support for developing as a researcher but concerned about development of some transferrable skills and attributes. Comparisons of graduate attribute application to graduate attribute development revealed the following areas requiring better support: teamwork, communication, project management, entrepreneurship, networking, and career development. Satisfaction results resonate with Woolston’s (Citation2019) findings from a Nature survey where 26% of respondents thought their PhD programme had prepared them ‘very well’ for a satisfying career.

Our survey focused on a narrow set of attributes, so future research and quality assuring of doctoral graduate attributes should cover all domains illustrated by our proposed new categorisation (). Given the increasing interest in fostering global citizens, future research is suggested to explore the views of students, university administrators, faculty and employers regarding the desirability of global citizenship attributes in doctoral graduates, and how these are best developed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Boulos, A. 2016. “The Labour Market Relevance of PhDs: An Issue for Academic Research and Policy-Makers.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (5): 901–913. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1147719.

- Bowden, J., G. Hart, B. King, K. Trigwell, and O. Watts. 2000. Generic Capabilities of ATN University Graduates. Sydney: University of Technology Sydney.

- Craswell, G. 2007. “Deconstructing the Skills Training Debate in Doctoral Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 26 (4): 377–391. doi:10.1080/07294360701658591.

- Durette, B., M. Fournier, and M. Lafon. 2016. “The Core Competencies of PhDs.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (8): 1355–1370. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.968540.

- Feldon, D. F., S. Jeong, J. Peugh, J. Roksa, C. Maahs-Fladung, A. Shenoy, and M. Oliva. 2017. “Null Effects of Boot Camps and Short-Format Training for PhD Students in Life Sciences.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (37): 9854–9858. doi:10.1073/pnas.1705783114.

- Heuritsch, J., Waajer, C. J. F. I, and C. M. van der Weijden. 2016. “Survey on the Labour Market Position of PhD Graduates: Competence COMPARISON and Relation between PhD and Current Employment.” Paper Presented at the.” 21st International Conference on Science and Technology Indicators, València, September 14–16. pp. 741–749. http://ocs.editorial.upv.es/index.php/STI2016/STI2016/paper/viewFile/4543/2327.

- Layton, R. L., V. S. H. Solberg, A. E. Jahangir, J. D. Hall, C. A. Ponder, K. J. Micoli, and N. L. Vanderford. 2020. “Career Planning Courses Increase Career Readiness of Graduate and Postdoctoral Trainees.” F1000 Research 9.

- Manathunga, C., R. Pitt, and C. Critchley. 2009. “Graduate Attribute Development and Employment Outcomes: Tracking PhD Graduates.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (1): 91–103. doi:10.1080/02602930801955945.

- Mantai, L. 2017. “Feeling like a Researcher: Experiences of Early Doctoral Students in Australia.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 636–650.

- McAlpine, L., and C. Amundsen. 2016. “Post-PhD Career Trajectories—Intentions.” Decision-Making and Life Aspirations. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McAlpine, L., I. Skakni, and K. Inouye. 2021. “PhD Careers beyond the Traditional: Integrating Individual and Structural Factors for a Richer Account.” European Journal of Higher Education 11 (4): 365–385. doi:10.1080/21568235.2020.1870242.

- McAlpine, L., M. Jazvac-Martek, and N. Hopwood. 2009. “Doctoral Student Experience in Education: Activities and Difficulties Influencing Identity Development.” International Journal for Researcher Development 1 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1108/1759751X201100007.

- Nerad, M. 2005. “From Graduate Student to World Citizen in a Global Environment.” International Higher Education (40). Accessed July 8, 2022 doi:10.6017/ihe.2005.40.7491.

- O’Brien, A. J. 2011. “Global Citizenship and the Stanford Cross-Cultural Rhetoric Project.” Journal of the NUS Teaching Academy 1 (1): 32–43.

- Platow, M. J. 2012. “PhD Experience and Subsequent Outcomes: A Look at Self-Perceptions of Acquired Graduate Attributes and Supervisor Support.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.501104.

- Porter, S. 2021. “Doctoral Reform for the 21st Century.” In The Future of Doctoral Research: Challenges and Opportunities, edited by Lee, A. and Bongaardt, R., London: Routledge.

- Rudd, E., and M. Nerad. 2015. “Career Preparation in PhD Programs: Results of a National Survey of Early Career Geographers.” GeoJournal 80 (2): 181–186. doi:10.1007/s10708-014-9587-1.

- Senekal, J. S., E. Munnik, and J. M. Frantz. 2022. “A Systematic Review of Doctoral Graduate Attributes: Domains and Definitions.” Frontiers in Education 7. doi:10.3389/feduc.2022.1009106.

- Seo, G., and H. T. Yeo. 2020. “In Pursuit of Careers in the Professoriate or beyond the Professoriate: What Matters to Doctoral Students When Making a Career Choice?” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 15: 615–635. doi:10.28945/4652.

- Sharmini, S., and R. Spronken-Smith. 2020. “The PhD—Is It Out of Alignment?” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (4): 821–833. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1693514.

- Sinche, Melanie, Rebekah L. Layton, Patrick D. Brandt, Anna B. O’Connell, Joshua D. Hall, Ashalla M. Freeman, Jessica R. Harrell, Jeanette Gowen Cook, and Patrick J. Brennwald. 2017. “An Evidence-Based Evaluation of Transferrable Skills and Job Satisfaction for Science PhDs.” Plos One 12 (9): e0185023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185023.

- Spronken-Smith, R. 2018. “Reforming Doctoral Education: There Is a Better Way.” CSHE Occasional Research Paper Series, 9. 18 (August, 2018). Accessed July 8, 2022 https://cshe.berkeley.edu/publications/reforming-doctoral-education-there-better-way-rachel-spronken-smith-university-otago

- Spronken-Smith, R. A., K. Brown, and C. Cameron. 2022. “Preparing PhD Candidates for Careers: Can We Do Better? In Proceedings of the Tertiary Education Research in New Zealand (TERNZ) Conference, edited by E. Heinrich, A. Jolley & L. Rowan, 73–74). HERDSA Aotearoa/New Zealand, November 23rd–25th.

- Spronken-Smith, R. A., K. Brown, C. Cameron, M. McAuliffe, T. Riley, and K. Weaver. 2022. “COVID-19 Impacts on Early Career Trajectories and Mobility of Doctoral Graduates in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Higher Education Research and Development. doi:10.1080/07294360.2022.2152782.

- Spronken-Smith, R., K. Brown, and R. Mirosa. 2018. “Employability and Graduate Attributes of Doctoral Graduates.” In Spaces, Journeys and New Horizons for Postgraduate Supervision, edited by Bitzer, E. Stellenbosch, SA: African Sun Media.

- Woolston, Chris. 2019. “PhDs: The Tortuous Truth.” Nature 575 (7782): 403–406. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7.