Abstract

Scholarship on feedback format tends to demonstrate that students prefer video feedback; however, the characteristics of study participants are often absent. This study builds on the scholarship of feedback practice mediated by technology and feedback literacy in intercultural contexts. A mixed methods approach examined international postgraduate students’ experience of, preferences for and attitudes towards three feedback formats: text, audio and video. Eighty-four participants in an Australian university completed a survey, and twelve participated in semi-structured phone interviews. The participants were mainly women from India, aged between 25 and 34 years old and declared English as a second language. Participants scored their experience with video, audio and written feedback. Written feedback was ranked first, followed by video and audio feedback. Participants reported that written feedback allows students to easily locate areas that need improvement. The role of the disciplinary traditions and respondents’ educational background is discussed to make sense of the results.

Introduction

Higher education feedback practice has gained increased attention as evidenced by the number of publications, including a meta-review by Van der Kleij, Adie, and Cumming (Citation2019). Feedback is a critical component of learning and academic performance, and effective feedback is a cornerstone in developing learner autonomy and providing a pathway for high achievement (Gibbs and Simpson Citation2005; Bloxham and Boyd Citation2008; Biggs and Tang Citation2011). Evidence on the use of feedback points to the need for the incorporation of substantive and action-oriented comments for the learner to utilise, as opposed to surface level and mechanical feedback (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Henderson et al. Citation2019; Dawson et al. Citation2019).

In their meta-review of 68 studies on the student role in feedback, Van der Kleij and colleagues reported a slow-moving shift from an approach centred on the passive role of the students (transmission model) towards a student-centric focus (dialogic model) in which students and teachers actively construct meaning (Van der Kleij, Adie, and Cumming Citation2019).

Feedback can be provided using various formats – among them audio, video and text. There is significant evidence supporting the advantages of audio and video feedback for students compared to written feedback (Evans Citation2013; McCarthy Citation2015; West and Turner Citation2016; Mahoney, Macfarlane, and Ajjawi Citation2019). In a qualitative synthesis of evidence on video feedback in higher education, Mahoney and colleagues identified 33 peer-reviewed papers. In fourteen studies video feedback was explicitly preferred by students over written feedback, contrasting with three studies where the preference was for written feedback (Edwards, Dujardin, and Williams Citation2012; Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015; Orlando Citation2016). Mahoney and colleagues observed that this evidence was largely drawn from small-scale studies – ranging from one 190 to just 4 participants (Borup et al. Citation2014; Elola and Oskoz Citation2016, respectively), with the novelty effect of video usage still unknown (Mahoney, Macfarlane, and Ajjawi Citation2019).

Our interest in exploring feedback using educational technologies was driven by seeking time-efficiencies. We all teach in a university-wide interdisciplinary post-graduate program, with students from diverse disciplinary, professional and cultural backgrounds. As students are introduced to new disciplines, concepts and academic traditions, there is a need to provide a substantial amount of feedback in the early stages of scaffolded assignments.

Review of the references

This study is focussed on two bodies of literature, feedback literacy and technology-enabled feedback, as foundations for this investigation. Feedback scholarship has been on the rise to understand what constitutes ‘effective’ feedback (Gibbs and Simpson Citation2005; Scott Citation2014; Dawson et al. Citation2019). Sutton’s (Citation2012) pivotal paper proposed three main dimensions for student feedback literacy: (i) acquiring academic knowledge (knowing) and openness to the process of learning and improvement (epistemological dimension); (ii) engaging with feedback from a position of vulnerability (being), in which boosting self-confidence and self-improvement are a critical element of developing an education identity (ontological dimension); and (iii) acting upon feedback (practical dimension) by interpreting the feedback received and deploying the necessary feed forward skills (doing). Sutton maintains that learner educational identity and the existing social relations between learners and educators can have a positive or negative impact on the development of these dimensions. Learners are not the sole focus of feedback literacy. Carless and Boud (Citation2018) identify the importance of educators creating a ‘suitable curriculum environment’ (1321) that is conducive to learner participation and modelling of desired behaviours. Carless and Winstone (Citation2023) propose a shared responsibility, also requiring educators to be feedback literate. They recommend a framework for teacher feedback literacy characterised by a curriculum and assessment dimension, a relational dimension that recognises the power-differentials and proposes a dialogic interaction between educators and learners, and a pragmatic dimension.

Feedback literacies in cross-cultural contexts

Examining the dimensions of education identity and culture, Evans and Waring (Citation2011) undertook a mixed-methods study to explore and compare UK-based and international student perceptions of feedback in relation to cognitive styles and culture. They concluded that international students (34 students from USA, Canada, Pakistan, India and Tajikistan) valued peer feedback more highly than UK-based students and favoured one-to-one feedback over group feedback. International students were also found to value detailed and comprehensive feedback on their drafts (compared to domestic students) and were less confident assessing their own performance (Evans and Waring Citation2011).

Tian and Lowe (Citation2013) examined the feedback experience of 13 post-graduate Chinese students in a UK university. Chinese students’ first reaction to formative feedback was labelled as ‘learning shock’ and produced a negative emotional response, as the new type of formative feedback and perception of academic performance was informed by participants’ previous educational experiences and the academic culture of origin. The authors argued feedback is not only a part of the new academic culture itself, but can act as a bridge between norms, rules and practices of the two cultures (580). The authors reported a radical change in the emotional response to tutor feedback by the end of the second semester, demonstrating students’ sense of inclusion in their new academic culture (Tian and Lowe Citation2013). The emotional response conclusions were similar in a narrative inquiry, also in the United Kingdom (Rovagnati, Pitt, and Winstone Citation2022). A large-scale cross-sectional survey conducted in two Australian universities with 4514 participants adds weight to these conclusions. International students (30% of the participants) were more likely to have a negative emotional reaction and feel more discouraged by educators’ feedback than domestic students (Ryan and Henderson Citation2018).

In highly diverse intercultural higher education systems, scholarship rejects the notion of a homogenous student cohort (Ryan and Henderson Citation2018), and makes visible the importance of feedback cultures and intercultural feedback competences (Rovagnati and Pitt Citation2022). To address the criticism of cultural bias and Western-academic dominance in the internationalisation of higher education discourse, Deardorff et al. (Citation2012) and Leask (Citation2015) proposed the inclusion of intercultural competences.

Student and educator feedback literacies and cultures are complex given the contextual, behavioural and learning factors involved. Chong (Citation2021) proposed an ecological perspective for student feedback literacy anchored in contextual dimensions (textual level, interpersonal, instructional and socio-cultural), individual dimensions (abilities, experience, goals and beliefs) and engagement dimensions (understand feedback, manage affect, make judgement and take action). Chong’s framework addressed a gap in the literature by integrating individual and contextual dimensions in the context of feedback literacy.

Feedback mediated by educational technologies

The scholarship on video and audio feedback, especially students’ experience, offers a very promising alternative to written feedback. By examining students’ experience with video feedback, some of the reported advantages include greater depth and detail (Crook et al. Citation2012; Turner and West Citation2013; Vincelette and Bostic Citation2013; Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015; Henderson and Phillips Citation2015; Elola and Oskoz Citation2016; Orlando Citation2016), flexible access, personal and individualised focus (Turner and West Citation2013; Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015; Henderson and Phillips Citation2015; Lamey Citation2015; Ali Citation2016; Orlando Citation2016), and improved engagement (Ali Citation2016). Reported drawbacks include emotional reactions and discomfort during viewing, a sense of helplessness for not being able to respond (one-sided communication) (Henderson and Phillips Citation2015), and technical difficulties in downloading and accessing the video files (Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015; Henderson and Phillips Citation2015; McCarthy Citation2015). From an educator’s perspective there is some robust consensus that video feedback enables lengthier comments than written-only feedback due to educator time-pressures (Jones, Georghiades, and Gunson Citation2012; Mathisen Citation2012; Crook et al. Citation2012; Henderson and Phillips Citation2015; Lamey Citation2015; Elola and Oskoz Citation2016; Anson et al. Citation2016).

Comparative analysis of the different feedback formats – video, audio and text – shows a tendency for students to prefer video or audio-visual screencast over written feedback (Cann Citation2007; Parton, Crain-Dorough, and Hancock Citation2010; Edwards, Dujardin, and Williams Citation2012; Thompson and Lee Citation2012; Turner and West Citation2013; Borup et al. Citation2014; West and Turner Citation2016; Elola and Oskoz Citation2016) based on some of the advantages reported. Mahoney and colleagues hypothesise there may be novelty effects of using audio-visual feedback materials (Mahoney, Macfarlane, and Ajjawi Citation2019). Grigoryan tested the use of written-only and the combination of video and written feedback, and concluded that not only did student preferences align with the latter (Grigoryan Citation2017a), but those who received combined audio-visual and text gained better scores than those who received text alone (Grigoryan Citation2017b). There is contrasting evidence, however, showing students prefer written over video feedback due to its efficiency and easy accessibility (Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015). Orlando (Citation2016) suggested students’ preferences for written feedback might be explained by older age and a ‘non-traditional’ student profile, making a comparison to young adult students over-represented in the literature. Orlando’s observations about the study participants’ profile raises an important issue on the role of student mediator factors and the educators’ decision on feedback format.

While designing the feedback intervention and searching for efficient and comprehensive feedback alternatives suitable for our post-graduate students, it was evident there would not be straightforward answers. Significant variability in the way the study participants were characterised in the literature made it difficult to predict student preferences. Some authors provided limited detail about participant characteristics (), age and gender being the most common demographic variable reported. Some studies, however, do not report any characteristics of study participants (Parton, Crain-Dorough, and Hancock Citation2010; Thompson and Lee Citation2012; Harper, Green, and Fernandez-Toro Citation2012; Edwards, Dujardin, and Williams Citation2012; Mathisen Citation2012; Lamey Citation2015; Mayhew Citation2017), presenting a gap in the literature.

Table 1. Student characteristics in technology-enabled feedback literature (video, audio and text).

Applying a cross-cultural lens to the existing literature, few studies identify cross-cultural student attributes such as international/domestic enrolment, spoken languages, ‘English as Second/Additional Language (ESL)’ subjects and nationality. Chew (Citation2014) focused on assessment feedback for international students in the UK and found all five Masters of Business Administration study participants expressed a preference for audio rather than written feedback. In this study, advantages of audio feedback reported include being more interesting, personal and engaging.

McCarthy (Citation2015) compared the three formats of feedback among 77 students in a Media Arts course and concluded student preference order was video, audio and then written feedback. This same pattern was observed in 12 international students who took part in the study. A study by Hung (Citation2016) assessed student preferences for peer-to-peer feedback using video. The study involved 60 Taiwanese English as a Foreign Language students. The cohort was mainly comprised of females between 19 and 20 years of age. This study concluded participants preferred video over written feedback, suggesting this enhanced personalised learning, attentive engagement, and provided a greater understanding of content.

To understand student preferences for feedback format, it is crucial that study design considers the inclusion of student characteristics, and reports on them with some level of detail.

Purpose and contribution

This study builds on the scholarship of feedback practice mediated by technology and feedback literacy in intercultural contexts, to examine international postgraduate students’ experience of, preferences for, and attitudes towards three formats of feedback - text, audio and video.

This paper addresses a gap in understanding around international students’ experience of and attitudes towards feedback:

Research Question 1) What are study participants’ perceptions about the advantages and disadvantages of each format of feedback?

Research Question 2) Which type of feedback format is the most preferred? Is there any correlation between students’ demographics, prior experiences with feedback and format preferences?

Methodology

Research design

A mixed methods sequential approach (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2017) was adopted with an online survey comprised of both quantitative and qualitative questions (84 participants) being followed by semi-structured telephone interviews with a smaller group of 12 participants ().

Table 2. Sequential mixed methods study design.

Quantitative phase of research

An online survey sought to investigate student preferences and perceptions on which type of feedback format was perceived as the most beneficial. The self-administered online survey included closed, scale, ranking and open-ended questions. The questions elicited contextual demographic data including age, gender, country of birth, language spoken at home and enrolment type. Students were also asked about their self-assessed confidence in using computer technology, familiarity with websites, prior experience with feedback during undergraduate studies, and perceived importance of feedback in undergraduate learning. The survey sought student views on accessibility, understanding and engagement with the three formats of feedback using statements with a 5-point Likert scale with anchors from ‘strongly agree’ (5) to ‘strongly disagree’ (1), as well as what they considered to be the advantages and disadvantages of each format of feedback using open-ended questions. The data collection was conducted by a research assistant in late 2019, and study participants used iPads to access and complete the online survey. A composite score for each of the feedback formats was calculated as the sum of the responses for each format divided by the number of responses for each format.

Risk ratios were used to investigate association between gender, age group, country of birth (India to other country) for preferred format. Quantitative data was analysed using R 4.2.0 using packages ‘tidyverse’ (Wickham et al. Citation2019), ‘likert’ (Bryer and Speerschneider Citation2016) and ‘epitools’ (Aragon et al. Citation2020). The embedded qualitative component allowed researchers to explore emerging themes, informing the next phase of data collection via interviews.

Qualitative phase of research

In 2020, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted by a research assistant on behalf of the research team. This provided consistency in interview style and removed any potential for academic staff to recognise voices or identify participants. Seventeen open-ended questions were posed to participants, with interviews lasting between ten and twenty minutes. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The initial thematic coding to each question was conducted by one of the authors (AS) using a qualitative analysis software (Nvivo12) (QSR International Pty Ltd). The review of the themes was conducted by a second author (MP), and variances were discussed until reaching consensus; some research themes were omitted as no consensus was reached.

Thematic analysis of the survey open-ended questions and the interviews followed top-down and bottom-up processes (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014), allowing for a deeper exploration of new emergent themes. Inductive and deductive approaches were used in a dialectical way informing the various phases of the study design.

Mixed methods analysis

While the sequential nature of the approach meant that two phases of data analysis were undertaken, the data was also analysed in a holistic manner to gain an overall understanding of the student perceptions of feedback. In keeping with the exploratory sequential design (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2017), consideration of the quantitative data in the light of the qualitative findings enabled additional insights to be gained. For example, further analysis of questions on prior experience of feedback during undergraduate studies produced surprising results.

Study background

Participants

Participants in this study were enrolled in a core unit of a postgraduate course in Health Administration at an Australian university, both in person and online. A total of 142 students were invited to complete the survey, 86 responded and 84 are part of our analysis. Two participants were not international students, and this is representative of the cohort in this unit at that time of the study. The majority (88%) were female and came from a clinical background: 33 students self-nominated for involvement in the interview process, with 12 being contactable, available and still willing when approached.

Procedure

During the teaching period, students enrolled in this unit received individualised video, audio and written feedback as part of the summative assessments. Each feedback file was uploaded to the learning management system. Students were introduced to the study as part of their assignment briefings and provided with explanations as to how to access their feedback.

Academic staff undertaking marking were introduced to the study, trained in how to use the hardware and software, provided with an overall script adapted from Henderson and Phillips (Citation2015) to help with consistency in feedback and taught how to upload it to the learning management system.

Human research ethics clearance was obtained from the institutional review board, and participation in each phase of the research required separate consent. Participation or otherwise in the study was not related to involvement in the unit or the feedback provided on assessments.

Results

Quantitative results

Eighty-six students participated in the self-administered online survey (61% response rate), of which two were domestic students and were excluded from this analysis. Most students (65) reported their country of birth as India, with three each from Bhutan and the Philippines, two from Nepal and Kenya, and one from Ghana, Indonesia, Korea, Mozambique, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, USA and Zimbabwe (). The majority (82) reported that English was not their first language; 22 participants were 18–24 years old, 57 were 25–34, and 5 were 35–44. The students born in India were much younger than participants from other countries, with no study participants above 35 years of age. There were 75 students who identified as female and 9 as male. Overall, the study participants felt confident using computer technology with 47.6% and 45.2% of those surveyed being, respectively, ‘always’ and ‘mostly’ confident. Frequent use of websites such as YouTube was reported − 74 reported ‘twice a week or more and 10 ‘more than once a month but less than twice a week’. When asked if feedback was important during undergraduate studies, 67 strongly agreed and 13 somewhat agreed ().

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Table 4. Experiences with feedback.

Experience with feedback formats

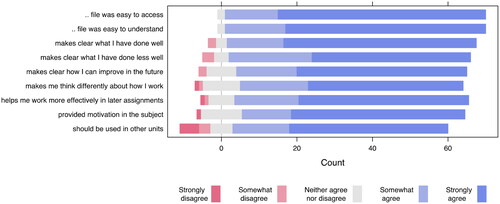

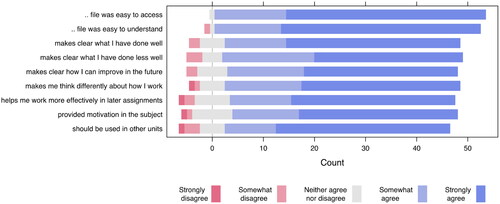

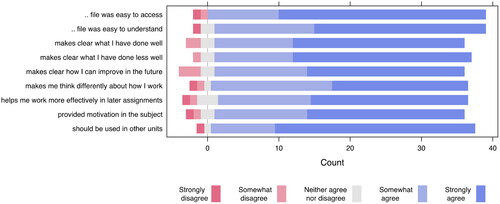

Students were asked to share their experience with video, audio and written feedback by stating their level of agreement on nine statements (). 71 students reported receiving video feedback. Overall, it was well received (), with a mean composite score of 4.5 (standard deviation 0.6, range: 2.7–5.0). Of the 71 students that had exposure to video feedback, 16 ranked it first, compared to one who did not have exposure. With audio feedback 54 participants reported experience, with a mean composite score of (sd 0.7, range: 2.4–5.0; ). All three students who ranked audio feedback as the preferred mode had received it. Finally, 41 respondents reported receiving written feedback (), with a mean composite score of 4.5 (sd 0.6, range 2.1–5.0); 23 who reported having exposure to written feedback ranked it number 1, compared to 9 (52.9%) who had not had exposure ().

Table 5. The mean Likert score for each of the 9 questions and mean composite score for each feedback formats: video, audio and written.

Feedback format preferences

At the end of the questionnaire, students were asked to rank feedback format according to their preference. Out of 52 respondents, written feedback was ranked first (63.0%), followed by video (31.5%) and audio feedback (5.6%) (). Examining the distribution according to country of birth (comparing those from India to others), there is no evidence to suggest participants born in India ranked modes of feedback differently.

Table 6. Preference for feedback format for all students, Indian students and students from other countries.

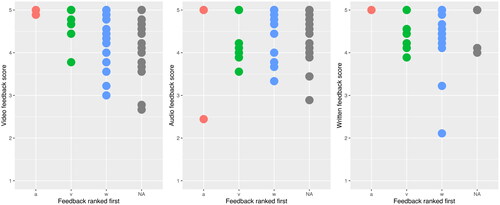

Students generally gave high scores for all formats, however the student with the with lowest composite score for audio feedback ranked it first, and the students with the two lowest written feedback composite scores ranked written feedback first ().

Figure 4. The composite score (out of 5) for different forms of feedback comparing students’ first ranked mode of feedback.

a = audio, v = video, w = written, NA = participant did not rank mode of feedback.

Experience with all formats of feedback was very positive, though there were some students who strongly disagreed that video feedback should be used in other units. There was also apparent conflict between composite scores of individual students and their ranking of formats ().

Qualitative results

The semi-structured interviews permitted breadth and depth in the analysis, confirming the validity and advantage of pursuing a mixed methods design.

Advantages and disadvantages of video feedback

The advantages that emerged from the qualitative analysis are consistent with the quantitative data and in some cases complementary. In the 75 responses from the survey and 12 interviews, students voiced six main advantages of video feedback: (i) tailored and personalised, (ii) a greater level of detail and ‘point by point’ explanation, (iii) improved understanding of their academic performance in the assignment, (iv) helpful for future assignments, (v) user-friendly and easily accessible, (vi) and fostering a personal connection (see excerpts in supplementary online materials). The theme ‘visualisation’ was absent in the questionnaire but raised by five out of twelve interviewees, while three interviewees highlighted the role of video feedback in motivating them to improve their assignments.

The analysis of disadvantages is mainly informed by the open-ended free response questions in the survey document, as interviewees reported few disadvantages and were brief in their responses. The top five most reported disadvantages were: (i) too laborious, (ii) confrontational and a cause of embarrassment and anxiety, especially if the students received a low mark in the summative assessment, (iii) technical issues with internet, ability to download files and incompatible file formats, (iv) issues with listening and watching (e.g. low voice and unfamiliar accent) and (v) difficulty in accessing files (see excerpts in supplementary online materials).

Recommendations to improve video feedback practice by educators

In both the survey and interviews, students were asked for suggestions to improve video feedback practice. Although the interviewees indicated they were satisfied with the strategies used, the survey participants suggested the combination of video feedback with text; improving the recording context (e.g. background noise, clear voice) and finding solutions that address the format/technology side of accessing the files from various devices.

Advantages and disadvantages of audio feedback

The qualitative data collected from 25 survey participants and 11 interviewees show a significant convergence of results. The main themes on the advantages include (i) easy access, (ii) versatile and permitting repetition, (iii) greater level of detail, (iv) clarity about the strengths and areas to improve (compared to written feedback), (v) greater understanding of the areas that need improvement (see excerpts in supplementary online materials). One interviewee was explicit about the importance of the conversational tone for improved understanding of the feedback. This theme was not found elsewhere in the data on audio feedback.

There are some similarities between the reported disadvantages of audio and video feedback. The main themes from the content analysis are time-consuming, problems with listening to the audio file and connectivity issues (see excerpts in supplementary online materials). However, there was no reference to any additional emotional load or anxiety-inducing situations with audio feedback.

Recommendations to improve audio feedback practice by educators

The majority of the respondents had no comments or recommendations. Those who had suggestions stressed the importance of receiving written feedback alongside the audio feedback, creating shorter files and improving the recording context in order to ensure the message is conveyed without disturbance. There are noticeable similarities between the recommendations for video and audio feedback.

Advantages and disadvantages of written feedback

Written feedback is the most common format to which study participants were exposed, and the most preferred. The themes that emerged from the data had some overlap, however not as much as for the other two formats. The top three advantages of written feedback were identified as (i) easily accessible, (ii) convenient format with future use, and (iii) providing a clear direction about what needs to be improved (see excerpts in supplementary online materials). Three students interviewed were very explicit about ‘localising’ written feedback. This feature was referred to in relation to ‘localising mistakes’, localising positive and negative points and localising the area that needs to be improved. One interviewee indicated that the written word can be easily understood even when students face communication challenges due to educators’ accents. Amongst the reported drawbacks of written feedback, the most frequent themes referred to (i) lack of detail and not being as long as other formats, and (ii) difficulty in understanding the message tutors/educators are trying to communicate. Conversely, three of the students interviewed, indicated that feedback is, at times, too extensive and tedious.

Recommendations to improve written feedback practice by educators

Students wanted lengthier and more elaborate explanations about their assignments, and the use of plain English as opposed to academic and discipline-related wording. Along the same lines, some respondents also suggested greater clarity in the written word. One respondent suggested a combination with audio feedback.

Discussion

This research was motivated by a need to understand what format of feedback was effective and the most preferred by international postgraduate students from diverse cultural backgrounds studying in a university in Western Australia. We investigated student attitudes towards three formats and their recommendations to improve feedback practice. We also explored associations between student demographics and feedback preferences.

In reference to research question one, our results are consistent with existing scholarship on video feedback which features the visual, personalised and human-presence dimensions (Mahoney, Macfarlane, and Ajjawi Citation2019). The reported benefits of audio feedback as providing greater detail than written feedback, being easily accessible and personalised are also aligned with the literature (Chew Citation2014; McCarthy Citation2015). Despite a high-level of satisfaction with video and audio feedback, respondents suggested the combination of written and video feedback as a strategy to improve practice. This recommendation may be explained by 98% of the respondents declaring English as a second language; however, this assumption needs to be tested. Written feedback is perceived as a format that allows students to localise and focus more easily on areas that need improvement. Participants also expressed a desire to receive more detailed, plain English and understandable feedback.

For our second research question, written feedback was ranked as the most preferred format, followed by video and audio feedback, and no differences were found across respondents born in India and elsewhere. Our study results are consistent with the studies by Borup, West, and Thomas (Citation2015) and Orlando (Citation2016). Borup and colleagues’ study had a sample of 180 respondents (mainly female) who ‘valued the efficiency of text over the more affective benefits of video’ (161). Orlando’s study only presents a brief characterisation of the study respondents as ‘non-traditional working adults in graduate [online] courses’ and speculates that the preference for written feedback might be due to the age and previous experience of participants (162).

As educators and researchers who have to make decisions about our teaching practice, the results of this study suggest feedback format preferences and efficacy is informed by complex and multifaced interactions between various factors, and we advise caution. The role played by respondents’ disciplinary traditions and educational systems is not yet known.

Health professional education and feedback practice

The majority of our study participants completed a bachelor level qualification in nursing, medicine or other health science degree. Feedback practice in the medicine and health has been historically characterised as an educator-driven, one-way process, embedded in hierarchical relationships (Archer Citation2010). The immersive nature of clinical education (placements) and the primacy of patient care (Watling et al. Citation2013) creates barriers for timely feedback, based on direct observation and being understood and accepted by the students (Burgess and Mellis Citation2015). Harrison et al. (Citation2015) explored the barriers to the uptake and use of feedback among medicine and health science students and found a disconnection between assessment and future learning, a powerful fear of failure in which passing the assessment was enough, and very strong emotions towards assessment and feedback. The strong emotional reaction is similar to the negative physiological reaction that interferes with the uptake of feedback described by Ajjawi, Olson, and McNaughton (Citation2022). In our study and elsewhere (Borup, West, and Thomas Citation2015; Henderson and Phillips Citation2015), video feedback was also referred to as exacerbating a negative emotional reaction. If feedback practices are ingrained in disciplinary traditions, educators might need to consider discipline-specific feedback literacies for educators and students (Carless et al. Citation2020). Some innovative uses of video feedback have been integrated in clinical performance assessments, and proven to improve medical students’ awareness of their strengths and weaknesses on clinical (Kam et al. Citation2019) and surgical skills (Farquharson et al. Citation2013).

Indian educational background

One of the factors which was considered in understanding the data on student preferences for written feedback in this study was the educational background of many of the students in the cohort. The majority of the students in the group were from India and had been subject to the Indian cultural expectations. Deb, Strodl, and Sun (Citation2015) reported that the school system in India is focussed on rote learning with ‘tremendous competition’ for entry into higher education: ‘Fear of failure is reinforced by both the teachers and the parents’ (27). Sawhney, Kunen, and Gupta (Citation2020) identified that Indian university students are expected to excel academically and ‘may experience criticism if they do not meet those expectations or show signs of not meeting the expectations by seeking help’ (276). Rote learning environments and pass or fail examinations are not conducive to the use of formative feedback or a learning approach anchored in assessment for learning, in which feedback feeds into later teaching and learning.

Another factor which emerged was the issue of critical thinking skills. The propensity for rote learning, and for seeking to provide answers which the educator is seeking, rather than taking a critical approach, while evident in much of the work from Indian students, is contrary to traditional Indian approaches. Bhattacharya, Shenolikar, and Hebbani (Citation2021) have identified that Indian logic may be a pathway to helping students to gain transferable skills such as critical evaluation of new knowledge and evidence-based insights. Potentially there are elements of Indian based logic which can be incorporated into the development of feedback literacy – such as ‘scope for questioning different viewpoints to refine them’ (Bhattacharya, Shenolikar, and Hebbani Citation2021, 8), although it is likely that educators will require increased feedback literacy to be able to draw on these traditions. Such cross-cultural awareness would also require educators to be familiar with other traditions such as Confucian approaches and Islamic approaches – and the requirement would not just be for feedback literacy, but also for other aspects of these traditions.

This study has some limitations. The study is based on a small number of participants, which we could not control. The characteristics of our study participants were, to some extent, homogenous, i.e. young female participants from India with a health sciences educational background. This constituted an obstacle to exploring associations between students’ profile characteristics and their experiences with feedback format. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted via phone, which were a less preferred way to collect the data. Further studies focused on diverse cohorts are warranted.

Conclusion – implications for teaching practice and scholarship

In the context of global student mobility and the ubiquity of technology in learning and teaching environments, our study findings raise important considerations on the preference of feedback format by international postgraduate students. The preference for written feedback over video feedback contrasts with the contemporary scholarship on video feedback as an enabler for social connection and assisting students to better understand the feedback message.

Our study findings have several implications for teaching practice and scholarship. From a teaching practice perspective, feedback literacies for educators and students need to consider cross-cultural dimensions as well as discipline-specific traditions. The inclusion of these dimensions informing feedback practice is critical in higher education learning and teaching, given global student mobility, intercultural learning communities and interdisciplinary studies. Our findings also demonstrate feedback format selection needs to move away from a one-size fits all approach toward a tailored student choice. Educators prepared to use digital technologies in feedback practice should consider students’ learning preferences instead of deferring to specific feedback format.

From a scholarship perspective, it is critical for future studies on feedback literacies informed with technology to include student characteristics in their design. By collecting granular information on participants’ socio-demographics and educational background, it might be possible to ascertain patterns in feedback format preferences. The combination of feedback format in study design is underrepresented in the literature and warrants further examination. Finally, a robust examination of the impact of feedback format focused on learning outcomes is still absent.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Aaron Alejandro, Astrid Davine, James Taylor, and Robert Sydenham for their contribution to this study. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive commentary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajjawi, R., R. E. Olson, and N. McNaughton. 2022. “Emotion as Reflexive Practice: A New Discourse for Feedback Practice and Research.” Medical Education 56 (5): 480–488. doi:10.1111/medu.14700.

- Ali, A. 2016. “Effectiveness of Using Screencast Feedback on EFL Students’ Writing and Perception.” English Language Teaching 9 (8): 106–121. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n8p106.

- Anson, C. M., D. P. Dannels, J. I. Laboy, and L. Carneiro. 2016. “Students’ Perceptions of Oral Screencast Responses to Their Writing: Exploring Digitally Mediated Identities.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 30 (3): 378–411. doi:10.1177/1050651916636424.

- Aragon, T. J., M. P. Fay, D. Wollschlaeger, and A. Omidpanah. 2020. “Epitools: Epidemiology Tools (Version 0.5-10.1).” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epitools.

- Archer, J. C. 2010. “State of the Science in Health Professional Education: Effective Feedback.” Medical Education 44 (1): 101–108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x.

- Bhattacharya, A., S. Shenolikar, and S. Hebbani. 2021. “Exploring the Significance of Indian Logic in Overcoming Contemporary Limitations in the Indian Education System.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education. doi:10.1080/02188791.2021.1987186.

- Biggs, J. B., and C. S. Tang. 2011. Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does. 4th ed. New York: Open University Press.

- Bloxham, S., and P. Boyd. 2008. Developing Effective Assessment in Higher Education: A Practical Guide. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Borup, J., R. E. West, and R. Thomas. 2015. “The Impact of Text versus Video Communication on Instructor Feedback in Blended Courses.” Educational Technology Research and Development 63 (2): 161–184. doi:10.1007/s11423-015-9367-8.

- Borup, J., R. E. West, R. Thomas, and C. R. Graham. 2014. “Examining the Impact of Video Feedback on Instructor Social Presence in Blended Courses.” International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 15 (3): 232–256.

- Bryer, J., and K. Speerschneider. 2016. “Likert: Analysis and Visualization Likert Items (Version 1.3.5). R.” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=likert.

- Burgess, A., and C. Mellis. 2015. “Feedback and Assessment for Clinical Placements: Achieving the Right Balance.” Advances in Medical Education and Practice: 6: 373–381. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S77890.

- Cann, A. J. 2007. “Podcasting is Dead. Long Live Video!.” Bioscience Education 10 (1): 1–4. doi:10.3108/beej.10.c1.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., J. To, C. Kwan, and J. Kwok. 2020. “Disciplinary Perspectives on Feedback Processes: Towards Signature Feedback Practices.” Teaching in Higher Education. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1863355.

- Carless, D., and N. Winstone. 2023. “Teacher Feedback Literacy and Its Interplay with Student Feedback Literacy.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 150–163. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372.

- Chew, E. 2014. “‘To Listen or to Read?’ Audio or Written Assessment Feedback for International Students in the UK.” On the Horizon 22 (2): 127–135. doi:10.1108/OTH-07-2013-0026.

- Chong, S. Wang. 2021. “Reconsidering Student Feedback Literacy from an Ecological Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1730765.

- Creswell, J. W., and V. L. Plano Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Crook, A., A. Mauchline, S. Maw, C. Lawson, R. Drinkwater, K. Lundqvist, P. Orsmond, S. Gomez, and J. Park. 2012. “The Use of Video Technology for Providing Feedback to Students: Can It Enhance the Feedback Experience for Staff and Students?” Computers & Education 58 (1): 386–396. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.025.

- Dawson, P., M. Henderson, P. Mahoney, M. Phillips, T. Ryan, D. Boud, and E. Molloy. 2019. “What Makes for Effective Feedback: Staff and Student Perspectives.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877.

- Deardorff, D. K., H. de Wit, J. D. Heyl, and T. Adams. 2012. The SAGE Handbook of International Higher Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Deb, S., E. Strodl, and J. Sun. 2015. “Academic Stress, Parental Pressure, Anxiety and Mental Health among Indian High School Students.” International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 5 (1): 26–34. doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150501.04.

- Edwards, K., A.-F. Dujardin, and N. Williams. 2012. “Screencast Feedback for Essays on a Distance Learning MA in Professional Communication.” Journal of Academic Writing 2 (1): 95–126. doi:10.18552/joaw.v2i1.62.

- Elola, I., and A. Oskoz. 2016. “Supporting Second Language Writing Using Multimodal Feedback.” Foreign Language Annals 49 (1): 58–74. doi:10.1111/flan.12183.

- Evans, C. 2013. “Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education.” Review of Educational Research 83 (1): 70–120. doi:10.3102/0034654312474350.

- Evans, C., and M. Waring. 2011. “Exploring Students’ Perceptions of Feedback in Relation to Cognitive Styles and Culture.” Research Papers in Education 26 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1080/02671522.2011.561976.

- Farquharson, A. L., A. C. Cresswell, J. D. Beard, and P. Chan. 2013. “Randomized Trial of the Effect of Video Feedback on the Acquisition of Surgical Skills.” The British Journal of Surgery 100 (11): 1448–1453. doi:10.1002/bjs.9237.

- Gibbs, G., and C. Simpson. 2005. “Conditions under Which Assessment Supports Students’ Learning.” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1: 3–31.

- Grigoryan, A. 2017a. “Audiovisual Commentary as a Way to Reduce Transactional Distance and Increase Teaching Presence in Online Writing Instruction: Student Perceptions and Preferences.” Journal of Response to Writing 3 (1): 5. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/journalrw/vol3/iss1/5.

- Grigoryan, A. 2017b. “Feedback 2.0 in Online Writing Instruction: Combining Audio-Visual and Text-Based Commentary to Enhance Student Revision and Writing Competency.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 29 (3): 451–476. doi:10.1007/s12528-017-9152-2.

- Harper, F., H. Green, and M. Fernandez-Toro. 2012. “Evaluating the Integration of Jing®; Screencasts in Feedback on Written Assignments.” In 2012 15th International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), 1–7. Villach, Austria: IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICL.2012.6402092.

- Harrison, C. J., K. D. Könings, L. Schuwirth, V. Wass, and C. van der Vleuten. 2015. “Barriers to the Uptake and Use of Feedback in the Context of Summative Assessment.” Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice 20 (1): 229–245. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9524-6.

- Henderson, M., E. Molloy, R. Ajjawi, and D. Boud. 2019. “Designing Feedback for Impact.” In The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education: Improving Assessment Outcomes for Learners, 267–285. Cham Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_15.

- Henderson, M., and M. Phillips. 2015. “Video-Based Feedback on Student Assessment: Scarily Personal.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 31 (1): 51–66. doi:10.14742/ajet.1878.

- Hung, S.-T Alan. 2016. “Enhancing Feedback Provision through Multimodal Video Technology.” Computers & Education 98 (July): 90–101. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.009.

- Jones, N., P. Georghiades, and J. Gunson. 2012. “Student Feedback via Screen Capture Digital Video: Stimulating Student’s Modified Action.” Higher Education 64 (5): 593–607. doi:10.1007/s10734-012-9514-7.

- Kam, B., Sung, S. Jung Yune, S. Yeoup Lee, S. Ju Im, and S. Yong Baek. 2019. “Impact of Video Feedback System on Medical Students’ Perception of Their Clinical Performance Assessment.” BMC Medical Education 19 (1): 252. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1688-6.

- Lamey, A. 2015. “Video Feedback in Philosophy.” Metaphilosophy 46 (4–5): 691–702. doi:10.1111/meta.12155.

- Leask, B. 2015. Internationalizing the Curriculum. London, UK: Taylor & Francis

- Mahoney, P., S. Macfarlane, and R. Ajjawi. 2019. “A Qualitative Synthesis of Video Feedback in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (2): 157–179. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1471457.

- Marriott, P., and L. K. Teoh. 2012. “Using Screencasts to Enhance Assessment Feedback: Students’ Perceptions and Preferences.” Accounting Education 21 (6): 583–598. doi:10.1080/09639284.2012.725637.

- Mathisen, P. 2012. “Video Feedback in Higher Education – a Contribution to Improving the Quality of Written Feedback.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 7 (2): 97–113. doi:10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2012-02-02.

- Mayhew, E. 2017. “Playback Feedback: The Impact of Screen-Captured Video Feedback on Student Satisfaction, Learning and Attainment.” European Political Science 16 (2): 179–192. doi:10.1057/eps.2015.102.

- McCarthy, J. 2015. “Evaluating Written, Audio and Video Feedback in Higher Education Summative Assessment Tasks.” Issues in Educational Research 25 (2): 153–169. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/mccarthy.html.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. London: SAGE.

- Orlando, J. 2016. “A Comparison of Text, Voice, and Screencasting Feedback to Online Students.” American Journal of Distance Education 30 (3): 156–166. doi:10.1080/08923647.2016.1187472.

- Parton, B., M. Crain-Dorough, and R. Hancock. 2010. “Using Flip Camcorders to Create Video Feedback: Is It Realistic for Professors and Beneficial to Students?” International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 7 (1): 15–21.

- Rovagnati, V., and E. Pitt. 2022. “Exploring Intercultural Dialogic Interactions between Individuals with Diverse Feedback Literacies.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (7): 1057–1070. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.2006601.

- Rovagnati, V., E. Pitt, and N. Winstone. 2022. “Feedback Cultures, Histories and Literacies: International Postgraduate Students’ Experiences.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1916431.

- Ryan, T., and M. Henderson. 2018. “Feeling Feedback: Students’ Emotional Responses to Educator Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (6): 880–892. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1416456.

- Sawhney, M., S. Kunen, and A. Gupta. 2020. “Depressive Symptoms and Coping Strategies among Indian University Students.” Psychological Reports 123 (2): 266–280. doi:10.1177/0033294118820511.

- Scott, S. V. 2014. “Practising What We Preach: Towards a Student-Centred Definition of Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.827639.

- Sutton, P. 2012. “Conceptualizing Feedback Literacy: Knowing, Being, and Acting.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 49 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.647781.

- Thompson, R., and M. Lee. 2012. “Talking with Students through Screencasting: Experimentations with Video Feedback to Improve Student Learning.” The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy Issue 1. https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/talking-with-students-through-screencasting-experimentations-with-video-feedback-to-improve-student-learning/.

- Tian, M., and J. Lowe. 2013. “The Role of Feedback in Cross-Cultural Learning: A Case Study of Chinese Taught Postgraduate Students in a UK University.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (5): 580–598. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.670196.

- Turner, W., and J. West. 2013. “Assessment for ‘Digital First Language’ Speakers: Online Video Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 25 (3): 288–296. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1029131.pdf.

- Van der Kleij, F. M., L. E. Adie, and J. Joy Cumming. 2019. “A Meta-Review of the Student Role in Feedback.” International Journal of Educational Research 98 (January): 303–323. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.005.

- Vincelette, E. J., and T. Bostic. 2013. “Assessing Writing Show and Tell: Student and Instructor Perceptions of Screencast Assessment.” Assessing Writing 18 (4): 257–277. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2013.08.001.

- Watling, C., E. Driessen, C. P. M. van der Vleuten, M. Vanstone, and L. Lingard. 2013. “Beyond Individualism: Professional Culture and Its Influence on Feedback.” Medical Education 47 (6): 585–594. doi:10.1111/medu.12150.

- West, J., and W. Turner. 2016. “Enhancing the Assessment Experience: Improving Student Perceptions, Engagement and Understanding Using Online Video Feedback.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 53 (4): 400–410. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.1003954.

- Wickham, Hadley, Mara Averick, Jennifer Bryan, Winston Chang, Lucy McGowan, Romain François, Garrett Grolemund, et al. 2019. “Welcome to the Tidyverse.” Journal of Open Source Software 4 (43): 1686. doi:10.21105/joss.01686.