Abstract

Feedback has long been considered a significant lever to enhance learning experience and success in higher education. However, students have shown much discontent with the current feedback practice. Feedback experienced as a relational process in which students feel recognized and valued is perceived as paramount for helping support the uptake of feedback and promote positive learning dispositions. However, little attention has been paid to suggesting how instructors in higher educational institutions can facilitate relational feedback. In response, we conducted a rapid literature review with a particular focus on the creation of feedback content. In total, 17 peer-reviewed publications on relational feedback are included. Based on a qualitative analysis of these papers, we developed a framework of 12 characteristics for offering relational feedback. These 12 characteristics were further categorised into four types of feedback conductive to a relational process, including (i) clarifying performance, (ii) suggesting improvement, (iii) inviting further communication, and (iv) evoking positive emotions. We examined how each of these characteristics supports the relational aspects of feedback. Based on the qualitative analysis results, we offered practical recommendations for instructors to apply relational feedback in their pedagogical practices.

Introduction

Feedback is a crucial part of communication between students and teachers in terms of clarifying expectations, monitoring the current progress of students, and reflecting on the trajectory towards desired learning goals (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). However, making feedback effective is difficult due to multifaceted reasons, such as instructors’ incapability to construct effective feedback, and students not acting on the provided feedback (Henderson, Ryan, and Phillips Citation2019).

Many studies conceptualized feedback predominantly as a one-way transmission of information by emphasizing teachers’ role in ensuring the quality of feedback (Nelson and Schunn Citation2009). However, the efficacy of feedback is also inextricably intertwined with the extent to which students are actively involved in the process, which enables the conceptual shift towards learner-centred feedback. Information transmission feedback frameworks and learner-centred feedback theories typically attribute the efficacy of feedback to both the feedback sender and the receiver. More and more research indicates that the development of relationships between the participants involved in the feedback process is also important to the effectiveness of feedback, thereby introducing the concept of ‘relational feedback’.

Relational feedback recognises the affective impact of feedback and how it can be shared in a way that supports the development of positive relationships between instructors and students (Kastberg, Lischka, and Hillman Citation2016; Heron et al. Citation2023). It is important that feedback is experienced as a relational process in which students feel recognised and valued, as this helps facilitate the uptake of feedback and enhance positive learning dispositions (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). However, there is a distinct lack of studies suggesting how to design relational feedback in practice. In response, the present study was conducted with the aim to develop a framework of feedback design characteristics to guide instructors in the creation of relational feedback. We specifically focus on offering instructors guidance on the construction of relational feedback content because instructors are at the forefront of delivering feedback, and they often encounter challenges in providing feedback in a relational manner (Henderson, Ryan, and Phillips Citation2019). We performed a rapid systematic review to identify content characteristics of relational feedback. These characteristics were then evaluated by checking whether they are supported by three significant conceptualisations of relational feedback: feedback triangle model (Yang and Carless Citation2013); relational communication theory (Wu et al. Citation2019); and academic buoyance framework (Middleton et al. Citation2023), for establishing a robust design framework of relational feedback.

Literature review

From teacher-centred to learner-centred feedback

Scholars have been working on developing theoretical models that explain what principles contribute to effective feedback design. For example, Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) claimed that effective feedback should answer three questions about the goal related to the task, the progress, and the future improvement, respectively. Through conceptual analysis of these three questions, four-level principles that influence feedback effectiveness emerge, which are feedback about the task (task-level), feedback about the process needed to complete a task (process-level), feedback about self-regulated learning (self-regulated level), and feedback about the student (self-level). In line with Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007), Shute (Citation2008) specifically focused on the task-level feedback and provided concrete and comprehensive guidelines to make feedback formative, for the sake of increasing student knowledge and skills. These design principles of feedback were termed ‘Feedback Mark 1’ by Boud and Molloy (Citation2013). Feedback Mark 1 viewed feedback as a one-way transmission of information from the instructor to the student and placed the onus on the instructors to ensure that feedback produces desirable effects on student learning (Boud and Molloy Citation2013). This model risks overlooking the active role students need to play in making use of feedback. Unlike Feedback Mark 1, ‘Feedback Mark 2’ emphasised student agency in the learning process by regarding feedback as the dialogue to support learning (Boud and Molloy Citation2013). This shift has prompted the development of learner-centred feedback frameworks (Ryan et al. Citation2021) to involve students in the feedback process. The information-transmission feedback model and the learner-centred feedback theory typically place instructors and students in the central position to improve the effectiveness of feedback. This is not sufficient to make feedback effective as an increasing number of studies suggest that the relationships between instructors and students in the feedback process also play a crucial role in students’ uptake of feedback. Additionally, how the feedback is created and delivered can significantly impact how students perceive the relationships with instructors (Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak Citation2013). Therefore, the design of feedback content for the relational purpose needs further investigation.

Relational feedback

The definition of relational feedback has not been unified yet, but two key relational aspects of feedback have been widely identified, i.e. relationship construction and emotion management. Yang and Carless (Citation2013) framed these two aspects as the social-affective dimension in the feedback triangle model. This dimension concerns how the management of emotions and relationships in the feedback process influences students’ ways of learning. They argued that relational feedback helps promote student self-regulation by creating a trusting atmosphere where positive relationships are supported. The value of building relationships via feedback process was also emphasized by Wu et al. (Citation2019). They viewed feedback as a communication process where students interact with the learning community to construct knowledge (informational value of feedback) and develop social relationships (relational value of feedback). Relationships fostered through the communication process in turn encourage ongoing communication and thus promote effective learning. Middleton et al. (Citation2023) stressed the importance of relational feedback in developing students’ academic buoyancy which is defined as the ability to cope with everyday setbacks in academic life. Despite the manifold advantages of relational feedback, guidelines for supporting instructors in the creation of relational feedback remain an area of ongoing research. The current study is guided by the research question: What are the content characteristics of relational feedback? In this study, we pay particular attention to the creation of relational feedback. We focus on reviewing the content of feedback that is created with the aim of promoting student learning by fostering the relationships between instructors and students, and eliciting students’ positive emotions towards learning.

Methods

A rapid systematic literature review is conducted to identify the characteristics of relational feedback in the field of education. In this study, we followed the guidelines proposed by Keele (Citation2007) to ensure transparency in the search process and analysis. In a rapid systematic review, the paper search, paper selection, and information extraction steps are often performed by a single researcher (in our case, the lead author of the paper). To ensure the rigour of the review process, all key decisions—including the selection of databases, the construction of keywords, and the establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria—were verified by the other co-authors.

Search process

Three academic databases that are prominent in publishing research in the field of education were selected, namely: Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC. The objective of this review was to identify the relational characteristics of feedback in the context of education. To facilitate a comprehensive search, we constructed keyword sets by elaborating on the core terms, i.e. ‘Feedback’, ‘Relational’, and ‘Education’. The final keywords used to perform the search are shown in . Each keyword within a group is paired using the OR operator, whereas different groups are combined using the AND operator to form the search query. We conducted iterative searches by varying the search fields for different groups of keywords. To enhance the precision of our literature search, we manually reviewed titles and abstracts of the first 20 results from each search iteration and assessed their relevance based on the criteria listed in . The optimal strategy for identifying pertinent literature was achieved when keywords from the ‘Feedback’ and ‘Relational’ groups were targeted within the ‘Title’ or ‘Abstract’ fields, and those from the ‘Education’ group were searched in all fields.

Table 1. Keywords and search field.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Selection of articles

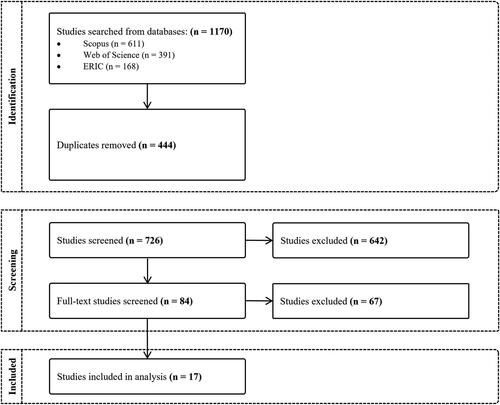

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are specified in . Note that we did not limit the search to a particular range of publication years or research areas, aiming to ensure a comprehensive scope in our literature search. The screening process is depicted in . We retrieved 1170 papers in total by searching three databases (i.e. Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC). After removing duplicates, 726 unique papers were retained for the subsequent screening process. By screening titles and abstracts, 642 studies were excluded from full-text screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

After full-text screening of the remaining 84 publications, a total of 17 papers successfully passed all the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

For each of the 17 publications reviewed in this study, we extracted the fields as listed in for subsequent qualitative analysis.

Table 3. Fields extracted from the included studies.

Qualitative synthesis

Based on the extracted descriptions of relational characteristics of feedback (i.e. No. 6 in ), we thematically analysed these qualitative descriptions by following a deductive process suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Specifically, the lead author first scrutinized every piece of extracted descriptions and generated an exhaustive list of codes. Through several rounds of moderation meetings with the co-authors involved, these codes were then categorised into potential themes. We reviewed and refined themes and codes until we obtained a clear and specific description for each code and each theme. Finally, we obtained a synthesised framework of 12 codes (feedback characteristics) and four overarching themes (feedback types). We evaluated the framework by checking whether each identified characteristic was supported by the existing conceptualisations of relational feedback, i.e. feedback triangle model (Yang and Carless Citation2013), relational communication theory (Wu et al. Citation2019), and academic buoyance framework (Middleton et al. Citation2023).

Results

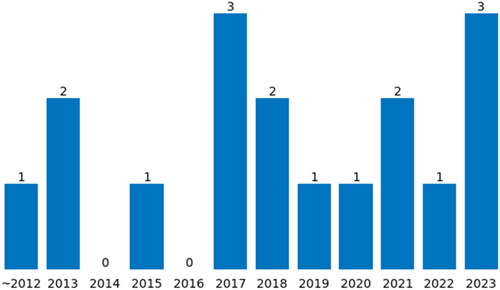

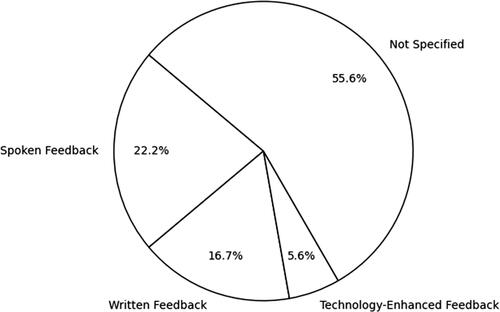

presents the annual distribution of the 17 publications analysed in this study, which shows that a significant proportion of the relevant literature has emerged in the past decade. However, the annual volume of publications remains modest. As indicated by Wu et al. (Citation2019), the relational aspects of feedback are in need of further investigation. The modes of feedback examined in these papers include spoken, written, and technology-enhanced feedback, such as audio and video formats (As shown in ).

The final framework consisting of 12 textual characteristics of relational feedback is summarised in , along with related works from which we extracted these characteristics. The 12 characteristics were categorised into four groups based on the different purposes they aim to achieve, i.e. clarifying performance (Group 1), suggesting improvement (Group 2), inviting further communication (Group 3), and evoking positive emotions (Group 4). The results of the conceptual appraisal suggested that all the identified characteristics of relational feedback are supported by the three existing conceptualisations, i.e. feedback triangle model (Yang and Carless Citation2013), relational communication theory (Wu et al. Citation2019), and academic buoyance framework (Middleton et al. Citation2023).

Table 4. Characteristics of relational feedback.

Discussion

We have identified 12 characteristics of relational feedback and organised them into four groups based on their fundamental role within the relational feedback process. Some of these characteristics resemble the features in existing feedback frameworks designed for students to develop feedback literacy (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Molloy, Boud, and Henderson Citation2020; Tam and Auyeung Citation2023). For example, ‘managing affect’ proposed by Carless and Boud (Citation2018), ‘acknowledges and works with emotions’ by Molloy, Boud, and Henderson (Citation2020) align with the characteristics of Group 4 in our framework. The 12 characteristics in our feedback framework were extracted for equipping instructors with specific strategies to craft feedback. Focusing on the role of instructors rather than students in managing the feedback effects is because instructors are the dominant provider of feedback in higher education (Ryan et al. Citation2021), and the effectiveness of feedback is intrinsically related to the content of feedback that is directly provided to students. Although the previous studies acknowledged the instructor role in enhancing the uptake of feedback and offered some activities for instructors to support the development of student feedback literacy, there remains a notable gap in specific and comprehensive guidelines specifically for creating relational feedback. This gap underscores the novelty of our feedback framework, which specifically addresses the creation of relational feedback.

Group 1: Clarifying performance

One of the crucial roles of feedback is to help students understand their current learning progress as a baseline from which to improve. Thus, feedback comments usually involve a judgement of student work, which could be supportive, or could disappoint and distress students (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). If the latter, students may be demotivated to accept and act upon the feedback (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). Consequently, it is important to inform students of their performance while also caring about their emotional responses through feedback such that they can deal constructively with the potential upset elicited by the assessment information.

Characteristic 1.1: Clarify the reason for the grade

Grades on assignments serve as a benchmark for measuring student performance against predetermined standards or learning objectives. They can also foster a range of students’ emotional responses, from pride to disappointment (Pitt and Norton Citation2017). Positive emotions can motivate students to invest more effort into their studies, while negative emotions may lead to decreased motivation, anxiety, or even withdrawal from learning activities (Pitt and Norton Citation2017). Feedback plays a crucial role in helping students regulate their emotions (Hill et al. Citation2021). Clarifying the reason for the grade in the feedback provides students opportunities to reflect how and why they did not achieve the desired grade (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). In this way, even if students receive low grades, they can use their disappointment constructively to enhance future performance (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018; Middleton et al. Citation2023). It is recommended that instructors offer precise and nuanced grade descriptors for each assessment criterion within the feedback comments (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018; Middleton et al. Citation2023). However, drafting detailed feedback on each marking criterion for a large cohort of students is time-consuming and tedious (Winstone and Boud Citation2022). Therefore, solutions, such as feedback templates (Crisostomo and Chauhan Citation2019) and automated feedback systems (Pardo et al. Citation2018) can be utilised to reduce instructors’ workload in the task of feedback construction.

Characteristic 1.2: Acknowledge the strengths of students’ performance

Feedback that acknowledges the strengths of students’ performance is not simply praise or encouragement, but the identification of positive aspects of students’ work. By explicitly indicating specific student strength in feedback, instructors offer affirmation of students’ ability to complete tasks (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018; Hill et al. Citation2021) and foster their confidence in pursuing subsequent achievement (Racheva Citation2018). Such positive encouragement is vital in maintaining a supportive environment where rapport between students and instructors can be facilitated (Heron et al. Citation2023) and students’ distress induced by assessments can be mitigated (Middleton et al. Citation2023). This characteristic is exemplified by highlighting the positive aspects of the assignment submitted. In face-to-face teaching settings, teachers often acknowledge student contributions by praising their responses to questions (e.g. ‘That’s great.’), and by showing agreement with students’ responses (e.g. ‘You are right.’) (Heron et al. Citation2023).

Characteristic 1.3: Balanced critical feedback

Critical feedback or negative feedback, as opposed to positive feedback indicating strengths, informs of mistakes or weaknesses to guide students in rethinking and improving their work (Schwartz Citation2017). While pointing out weaknesses in feedback is perceived as more effective than positive feedback at directing students to future improvement (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007), an excess of negative critique will likely be upsetting to students, causing negative emotions of sadness, shame, and anger, especially for students who receive grades lower than expected (Ryan and Henderson Citation2018). These negative emotional responses can have a detrimental impact on students’ motivation, self-confidence, and self-esteem (Hill et al. Citation2021). Therefore, maintaining an appropriate balance between support and critique in feedback is important to moderate the effect of negative comments (Yang and Carless Citation2013). Negative feedback offered with a clear direction for improvement (i.e. constructive criticism) is beneficial in generating positive emotions in students through supporting them in being forward looking (Hill et al. Citation2021). Additionally, showing respect for student work and recognition of their effort invested in the task when delivering negative feedback are also useful to make students feel cared about and increase their confidence (Hill et al. Citation2021).

Group 2: Suggesting improvement

Feedback involves more than assessment information about student past performance. It is considered by students as a prompt for further actions and a resource for improvement in future assignments (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). Feedback focusing on suggesting improvement shifts students’ attention from the current grade, either satisfying or disappointing, to the next assessment. Being forward looking and being improvement focused help students cope with negative emotional reactions induced by feedback (Jones et al. Citation2012). Such management of emotions is crucial for maintaining student engagement and resilience in learning.

Characteristic 2.1: Identify areas for improvement

Students may experience anxiety and stress if they perceive critique as a threat to their self-worth. This perception can not only hamper their ability to effectively utilise feedback, but it can also lead to a breakdown in communication with instructors, driven by a fear of further criticism (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). Conversely, feedback focusing on developing future achievement shifts the emphasis towards growth and potential. This approach encourages students to view feedback as constructive guidance on enhancing their educational outcomes, rather than as a critique of their past mistakes (Bastola and Hu Citation2021). Student acknowledgement of the developmental value of feedback mitigates the negative emotions caused by critique comments or grades lower than expected. This recognition also fosters a positive feedback environment where students are more open to receiving feedback, more active to apply it to future tasks, and thus more willing to seek feedback from instructors (Hill et al. Citation2021). We provide an example of critical feedback (Example 1) and an example of feedback that identifies areas for improvement (Example 2) as follows for a clear comparison. The first example is more about pointing out faults, while the second one is encouraging and offers suggestions for improvement.

Example 1:

Your presentation was too complicated and hard to follow. You should have made it simpler.

Example 2:

Your presentation can be improved if you could simplify the graphs for easier understanding.

Characteristic 2.2: Inform methods to improve work

While feedback about improvements is crucial for students to understand what needs to be improved, it may not always provide clear guidance on how to make these improvements. In other words, it is more about ‘what’ is wrong rather than ‘how’ to fix it. Feedback that informs students about methods to improve their work (Characteristic 2.2) goes a step further, effectively paving a clear path for guiding students towards practical strategies for improvement. It often includes tips, resources, or techniques that students can use. The following Example 3 was revised based Example 2 to include Characteristic 2.2.

Example 3:

Your presentation can be improved if you could simplify the graphs for easier understanding. (Characteristic 2.1) Consider using fewer data points for clarity and employing a consistent colour scheme. (Characteristic 2.2)

Knowing exactly what methods can enhance work can increase students’ motivation to utilise feedback and boost their confidence in lifting their performance to the desired level (Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak Citation2013). Providing explanatory advice in feedback conveys to students that instructors genuinely care about their academic success, thereby fostering trust between students and instructors. As trust improves, students are more likely to collaborate with instructors in learning by taking instructors’ advice, actively engaging with the learning materials, and participating in discussions (Middleton et al. Citation2023).

Characteristic 2.3: Actionable information

Actionable feedback clearly outlines what specific, actionable steps students might take next to improve their work. By providing a clear path forward, actionable information can reduce anxiety and fear of failure and helps students focus on what they can do rather than dwelling on what went wrong (Ahmed Shafi et al. Citation2018). When students adopt a growth mindset, they can see challenges as opportunities for learning and feel more optimistic about their ability to succeed (Middleton et al. Citation2023). We revised Example 3 to include actionable information, as shown in Example 4.

Example 4:

Your presentation can be improved if you could simplify the graphs for easier understanding (Characteristic 2.1). Consider using fewer data points for clarity (Characteristic 2.2). You could select the most important points that directly support your argument. For example, if your graph currently shows data for every month of the year, consider showcasing just the quarterly data to convey the trend without overcrowding the graph (Characteristic 2.3).

Group 3: Inviting further communication

Feedback serves as a communication process where students interact with the learning community, such as instructors to construct knowledge and develop social relationships. Relationships fostered through feedback in turn influence ongoing interactions and information acquisition (Wu et al. Citation2019). Inviting further communication is beneficial to relationship building between students and instructors and encourages students to continue their discussions by transforming the role of instructors from being authoritative figures to partners in dialogue (Rubic Citation2017).

Characteristic 3.1: Request clarification

The primary objective of requesting clarification in educational settings is to enhance instructors’ or teachers’ comprehension of students’ current work. This process often involves prompting students to explain and clarify their work or responses. A common strategy used for this purpose is questioning, e.g. ‘Can you be more specific on this point’ (Heron et al. Citation2023). For questioning to be most effective, the use of questions should encourage mutual respect and students’ contribution (Rubic Citation2017). Referential questions rather than display questions are recommended to be included in feedback comments (Rubic Citation2017). Display questions to which instructors already know the answers are designed for students to ‘display’ their knowledge. Such questions are typically used to assess students’ understanding and ask them to provide confirmation (Brock Citation1986), e.g. ‘What are the steps involved in the water cycle?’. Referential questions are distinct in that their answers are not pre-determined or known to the instructor at the moment of asking, e.g. ‘How do you feel about the ending of the novel?’. Referential questions are more open-ended, inviting students’ personal perspectives, which can lead to a more dynamic and exploratory discussion (Rubic Citation2017).

Characteristic 3.2: Advance student thinking

Advancing student thinking through feedback is about encouraging students’ thinking aloud for generating further ideas. This approach not only creates opportunities for students to use the feedback to improve their understanding but also promotes ongoing discussion with instructors. To effectively stimulate student thinking, instructors or teachers can employ strategies, such as probing with ‘why’ questions (e.g. ‘Why do you think that?’), and elaborating on students’ responses to offer additional information for students to delve deeper into the subject knowledge (Heron et al. Citation2023).

Group 4: Evoking positive emotions

Characteristics in Group 4 focus on the methods of conveying feedback in a way that is relational and sensitive to emotional dynamics. Feedback causing positive emotions increases students’ motivation and confidence to learn (Kim and Lee Citation2019).

Characteristic 4.1: Positive appreciation

Unlike Characteristic 1.2 that focuses on the positive aspects of students’ performance, positive appreciation primarily involves positive evaluations about the student. Positive appreciation of students’ efforts in completing the task makes students feel valued and lets them know that instructors care about their learning. Such positive reinforcement encourages students to challenge themselves more deeply (Schwartz Citation2017). Thus, they may be more receptive to receiving and acting upon critical feedback, which in turn leads to greater academic achievement (Schwartz Citation2017). To acknowledge student input, we can simply say ‘Thank you’ or general compliments, such as ‘Great’ or ‘Well done’ to students (Heron et al. Citation2023).

Characteristic 4.2: Showing empathy

Showing empathy enhances feedback effectiveness by providing students with relational support (Carless and Winstone Citation2023). Empathy shown by instructors or teachers to students or learners was denoted as teacher empathy by Meyers et al. (Citation2019). Teacher empathy refers to the extent to which instructors understand and care for students’ social situations, personal perspectives, and feelings. It involves not only feeling a sense of caring and concern in response to students’ positive and negative emotions but also communicating this understanding and compassion to students through their behaviours (Meyers et al. Citation2019). To express empathy in feedback, instructors could comment, such as ‘I can see what you have tried to do.’ and ‘I can see you are struggling with the task.’ (Payne, Ajjawi, and Holloway Citation2022). Instructors can also demonstrate empathy by sharing their personal experiences with dealing with critical feedback. This practice could help students perceive the feedback process as an opportunity for development, rather than as a reflection of their inadequacies (Schwartz Citation2017). An alternative approach, as suggested by Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak (Citation2013), is furnishing students with a generic list of common problems in their submitted assignments instead of providing individual feedback. This strategy may assist in reducing the sense of isolation that students might feel regarding their errors, thereby potentially diminishing the emotional impact of any negative feedback received (Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak Citation2013). While listing frequent problems can be beneficial, there is a risk that individual needs may be overlooked. Students who have unique issues not covered by the list may feel neglected, which could potentially hinder their learning progress. Additionally, students whose errors are not common problems might become complacent, which can reduce their motivation to engage deeply with their own specific learning processes.

Characteristic 4.3: Phrasing feedback in a positive manner

Framing feedback in a positive manner is crucial for maintaining student confidence, which can aid students in accepting critical evaluations of their work with a constructive emotional perspective (Hill et al. Citation2021). Such regulation of emotions could further facilitate students’ engagement with feedback, increase students’ learning motivation, and enhance learning outcomes (Van De Vliert et al. Citation2004; Kim and Lee Citation2019). Students preferred positive feedback to negative comments, despite acknowledging the necessity of constructive criticisms for their academic growth (Jones et al. Citation2012). However, instructors highlighted difficulties in giving critical feedback to students in positive ways (Henderson, Ryan, and Phillips Citation2019). Bastola and Hu (Citation2021) suggested that instructors can employ praise in the feedback to mitigate the impact of criticism, thereby boosting student confidence and fostering positive interpersonal relationships. Additionally, negative feedback followed by information about how to improve can help enhance student receptiveness of critical feedback (Middleton et al. Citation2023).

Characteristic 4.4: Phrasing feedback in a polite manner

The utilization of polite language in educational contexts offers multifaceted advantages. Polite language sets a respectful tone in communication, making instructions and feedback more palatable to students. When students feel respected, their learning motivation is likely to increase. It also helps in reducing misunderstandings by ensuring information is conveyed without being obscured by unintended rudeness. By using polite language, instructors foster a trusting and respectful environment where students are more likely to engage themselves in the feedback process (Lin et al. Citation2023). To enhance the politeness of feedback, it is recommended to use strategies, such as apologising (e.g. ‘I am sorry if I misunderstand your points.’) and hedging language (e.g. ‘maybe’, ‘could’) (Ajjawi and Boud Citation2017).

Definition of relational feedback

Based on the investigation into the literature on relational feedback, we define relational feedback as an interactive process designed to facilitate effective learning through relationship construction between students and the learning community, such as instructors and peers. Feedback, in its traditional meaning, is understood as a type of assessment information delivered from others to learners. Such assessment implies a power dynamic where the giver of the feedback holds a position of authority or expertise. This power dynamic can elicit students’ negative emotions, pose a threat to students’ self-esteem (Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak Citation2013), and thus demotivate students from active participation in learning activities to avoid further criticism. If students feel unfairly treated or humiliated by feedback, they would develop a distrust of the feedback provider. Without trust, strong relationships could not be established, which leads to a hostile learning environment where every individual student may be passively involved and be negatively impacted. Relational feedback aims to build a positive learning environment where equal power relationships between different participants are fostered. Good rapport among peers provides emotional support which is crucial for overcoming daily academic challenges. Positive relationships with instructors build trust which encourages students to express concerns about learning, seek feedback, and act upon feedback to improve. In return, the improvement of learning outcomes enhances students’ engagement in the feedback process.

An effective relational feedback process requires the careful design of feedback content, as the way feedback is formulated and delivered can impact the instructor-student relationship. Based on the results in , crafting feedback that clarifies student performance (Group 1), suggests improvement (Group 2), invites further communication (Group 3), and evokes positive emotions (Group 4) can strengthen relational bonds by conveying instructors’ care and commitment in student learning. On the other hand, the instructor-student relationship built through the feedback process can significantly influence how students receive and perceive feedback. A positive and trusting relationship between instructors and students often contributes to the update of feedback. In such a learning environment, students can feel that instructors care about their development, making them more receptive to criticism and more motivated to improve (Hill et al. Citation2021). Conversely, if the relationship is perceived as unsupportive, students may interpret feedback as criticism rather than constructive advice to aid their learning.

Limitations and future work

Firstly, the rapid literature review in this study was conducted by a single researcher, unlike the traditional systematic literature review which involves multiple reviewers at various stages (e.g. paper screening and data extraction). Therefore, we may not have retrieved a comprehensive set of publications due to the potential bias introduced in the review process. Secondly, while the construction of feedback content is a critical aspect that requires attention for facilitating relational feedback, the structural dimension of feedback, such as the timing of feedback, is equally pivotal (Yang and Carless Citation2013). For example, if feedback is delivered too late, students might feel that their work is not being taken seriously and may distrust instructors (Carless Citation2012). Future research should explore the relationship between structural aspects of feedback and student emotions. Lastly, the present review reveals that most studies on relational feedback are conceptual. There is a significant need for empirical evidence to assess the effectiveness of these relational characteristics.

Conclusions

This study proposed a framework aimed at assisting higher education instructors in designing relational feedback. The 12 relational characteristics were identified and categorised into four groups based on its fundamental role within the relational feedback process. The process begins with ‘Clarifying performance’ (Group 1) which provides students with an understanding of their current performance. Once performance has been clarified, the next step is to offer concrete guidance on how to enhance learning outcomes, which leads to Group 2, i.e. ‘Suggesting improvement’. Subsequently, the feedback process naturally shifts to ‘Inviting further communication’ (Group 3) which is crucial for fostering a two-way exchange where students can discuss the feedback, asking questions, and clarify their understanding. Group 4, i.e. ‘Evoking positive emotions’ aims to reinforce a positive learning environment where positive emotions among students might motivate them to make use of feedback and actively participate in the ongoing feedback process. These identified characteristics are unsurprising, as each of them has been illuminated in the literature that benefits student learning. However, this study particularly delves into the relationship between these characteristics and relational purposes of feedback, and offers practical suggestions for instructors to facilitate relational feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wei Dai

Wei Dai is currently pursuing a PhD in the Faculty of Information Technology at Monash University. Her research focuses on enhancing feedback effectiveness through learning analytics. Wei Dai has contributed to various conferences (e.g. AIED, LAK and ICALT) and journals (e.g. Neurocomputing and IEEE Transactions on Big Data) in the field of information technology and educational research. Before embarking her PhD journey, Wei Dai earned her Master’s degree in software engineering from Shenzhen University in China, where she developed a strong foundation in statistical analysis, predictive modeling, data mining and natural language processing. Her dedication to her research is driven by a passion for leveraging technology to solve real-world problems.

Yi-Shan Tsai

Yi-Shan Tsai is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, and a core member of the Centre for Learning Analytics at Monash (CoLAM). She is also a member of the Digital Education Research Group at Monash University, an associate scholar of the Centre for Research in Digital Education and the Centre for Research in Education Inclusion and Diversity, and an honorary fellow at School of Informatics at the University of Edinburgh. Her research focuses on advancing the understanding of socio-technical issues around the use of data in education, promoting trustful and value-based adoption of learning analytics, and enhancing feedback processes using learning analytics. She has served as the Vice President (2021–2023) and Communication Working Group Chair (2020–2021) of the Society for Learning Analytics Research (SoLAR) and a Communication Working Group member of the Latin American Learning Analytics Interest Group (LALA SIG), of which she is a founding member. She is particularly known for the achievements on an award-winning project (2019 Learning Technology Research Project of the Year, Association for Learning Technology), SHEILA (Supporting Higher Education to integrate Learning Analytics), which has informed policy development for learning analytics in over 200 higher education institutions around the world.

Dragan Gašević

Dragan Gašević is Distinguished Professor of Learning Analytics and Director of Research in the Department of Human Centred Computing of the Faculty of Information Technology and the Director of the Centre for Learning Analytics at Monash University. Dragan’s research interests center around data analytic, AI, and design methods that can advance understanding of self-regulated and collaborative learning. He is a founder and served as the President (2015-2017) of the Society for Learning Analytics Research. He has also held several honorary appointments in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. He is a recipient of the Life-time Member Award (2022) as the highest distinction of the Society for Learning Analytics Research (SoLAR) and a Distinguished Member (2022) of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). In 2019-2023, he was recognized as the national field leader in educational technology in The Australian’s Research Magazine that is published annually. He led the EU-funded SHEILA project that received the Best Research Project of the Year Award (2019) from the Association for Learning Technology.

Guanliang Chen

Guanliang Chen is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Information Technology and a member of the Centre for Learning Analytics at Monash. His research is at the forefront of integrating advanced Artificial Intelligence technologies to promote fairness and inclusivity in education. His research works have been published in international journals and conferences including LAK, AIED, LAK, AAAI, IJCAI, COLING, Computers & Education, British Journal of Educational Technology, and IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies. Dr. Chen’s groundbreaking work in identifying and reducing algorithmic bias in educational contexts has earned him significant recognition. He received the Outstanding Paper award at the COLING conference in 2022, and the Dean’s Award for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (Research) from Monash University’s Faculty of Information Technology in both 2021 and 2023. He is an editorial board member for two leading journals in technology-enhanced education, including ‘Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence’ (a Q1 journal).

References

- Ahmed Shafi, A., J. Hatley, T. Middleton, R. Millican, and S. Templeton. 2018. “The Role of Assessment Feedback in Developing Academic Buoyancy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (3): 415–427. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1356265.

- Ajjawi, R., and D. Boud. 2017. “Researching Feedback Dialogue: An Interactional Analysis Approach.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (2): 252–265. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863.

- Bastola, M.N., and G. Hu. 2021. “Commenting on Your Work is a Waste of Time Only!: An Appraisal-Based Study of Evaluative Language in Supervisory Feedback.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 68: 100962. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100962.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013. “Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 698–712. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brock, C.,. A. 1986. “The Effects of Referential Questions on ESL Classroom Discourse.” TESOL Quarterly 20 (1): 47–59. doi:10.2307/3586388.

- Carless, D. 2012. “Trust and Its Role in Facilitating Dialogic Feedback.” In Feedback in Higher and Professional Education, 90–103. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203074336.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., and N. Winstone. 2023. “Teacher Feedback Literacy and Its Interplay with Student Feedback Literacy.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 150–163. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372.

- Crisostomo, M.E., and R.S. Chauhan. 2019. “Individualized Student Feedback: Are Templates the Solution?” Management Teaching Review 4 (4): 371–382. doi:10.1177/2379298118823672.

- Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Henderson, M., T. Ryan, and M. Phillips. 2019. “The Challenges of Feedback in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (8): 1237–1252. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1599815.

- Heron, M., E. Medland, N. Winstone, and E. Pitt. 2023. “Developing the Relational in Teacher Feedback Literacy: Exploring Feedback Talk.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (2): 172–185. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1932735.

- Hill, J., K. Berlin, J. Choate, L. Cravens-Brown, L. McKendrick-Calder, and S. Smith. 2021. “Exploring the Emotional Responses of Undergraduate Students to Assessment Feedback: Implications for Instructors.” Teaching & Learning Inquiry 9 (1): 294–316. doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.20.

- Jones, H., L. Hoppitt, H. James, J. Prendergast, S. Rutherford, K. Yeoman, and M. Young. 2012. “Exploring Students Initial Reactions to the Feedback They Receive on Coursework.” Bioscience Education 20 (1): 3–21. doi:10.11120/beej.2012.20000004.

- Kastberg, S., A. Lischka, and S. Hillman. 2016. “Exploring Written Feedback as a Relational Practice.” In Enacting self-study as methodology for professional inquiry edited by D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.). Herstmonceux, UK: S-STEP.

- Keele, S. 2007. “Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering.” Technical Report, Technical Report, Ver. 2.3, EBSE Technical Report. Vol. 5, EBSE.

- Kim, E.J., and K.R. Lee. 2019. “Effects of an Examiners Positive and Negative Feedback on Self-Assessment of Skill Performance, Emotional Response, and Self-Efficacy in Korea: A Quasi-Experimental Study.” BMC Medical Education 19 (1): 142. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1595-x.

- Lin, J., M. Raković, Y. Li, H. Xie, D. Lang, D. Gašević, and G. Chen. 2023. “On the Role of Politeness in Online Human–Human Tutoring.” British Journal of Educational Technology 55 (1): 156–180. doi:10.1111/bjet.13333.

- Meyers, S., K. Rowell, M. Wells, and B.C. Smith. 2019. “Teacher Empathy: A Model of Empathy for Teaching for Student Success.” College Teaching 67 (3): 160–168. doi:10.1080/87567555.2019.1579699.

- Middleton, T., A. Ahmed Shafi, R. Millican, and S. Templeton. 2023. “Developing Effective Assessment Feedback: Academic Buoyancy and the Relational Dimensions of Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 118–135. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1777397.

- Molloy, E., D. Boud, and M. Henderson. 2020. “Developing a Learning-Centred Framework for Feedback Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (4): 527–540. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955.

- Nelson, M.M., and C.D. Schunn. 2009. “The Nature of Feedback: How Different Types of Peer Feedback Affect Writing Performance.” Instructional Science 37 (4): 375–401. doi:10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x.

- Pardo, Abelardo, Kathryn Bartimote, Simon Buckingham Shum, Shane Dawson, Jing Gao, Dragan Gašević, Steve Leichtweis, et al. 2018. “OnTask: Delivering Data-Informed, Personalized Learning Support Actions.” Journal of Learning Analytics 5 (3): 235–249. doi:10.18608/jla.2018.53.15.

- Payne, A.L., R. Ajjawi, and J. Holloway. 2022. “Humanising Feedback Encounters: A Qualitative Study of Relational Literacies for Teachers Engaging in Technology-Enhanced Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (7): 903–914. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2155610.

- Pitt, E., and L. Norton. 2017. “Now That’s the Feedback I Want! Students’ Reactions to Feedback on Graded Work and What They Do with It.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (4): 499–516. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1142500.

- Racheva, V. 2018. “Social Aspects of Synchronous Virtual Learning Environments.” In Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Applications of Mathematics in Engineering and Economics 2048: 020032. Melville: AIP Publishing. doi:10.1063/1.5082050.

- Robinson, S., D. Pope, and L. Holyoak. 2013. “Can we Meet Their Expectations? Experiences and Perceptions of Feedback in First Year Undergraduate Students.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (3): 260–272. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.629291.

- Rubic, I. 2017. “Integrating Dialogic Pedagogy in Teaching ESP.” Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes 5 (1): 113–126. doi: 10.22190/JTESAP1701113R.

- Ryan, T., and M. Henderson. 2018. “Feeling Feedback: Students’ Emotional Responses to Educator Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (6): 880–892. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1416456.

- Ryan, T., M. Henderson, K. Ryan, and G. Kennedy. 2021. “Designing Learner-Centred Text-Based Feedback: A Rapid Review and Qualitative Synthesis.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (6): 894–912. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1828819.

- Schwartz, H.L. 2017. “Sometimes It’s about More than the Paper: Assessment as Relational Practice.” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 28 (2): 5–28.

- Shute, V.J. 2008. “Focus on Formative Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 78 (1): 153–189. doi:10.3102/0034654307313795.

- Tam, A.C.F., and G.K.Y. Auyeung. 2023. “Exploring Students’ Strategy-Related Beliefs and Their Mediation on Strategies to Act on Feedback in L2 Writing.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (7): 1038–1052. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2157795.

- Van De Vliert, E., K. Shi, K. Sanders, Y. Wang, and X. Huang. 2004. “Chinese and Dutch Interpretations of Supervisory Feedback.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 35 (4): 417–435. doi:10.1177/0022022104266107.

- Winstone, N.E., and D. Boud. 2022. “The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (3): 656–667. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687.

- Wu, M., X. Xu, L. Kang, J.L. Zhao, and L. Liang. 2019. “Encouraging People to Embrace Feedback-Seeking in Online Learning: An Investigation of Informational and Relational Drivers.” Internet Research 29 (4): 749–771. doi:10.1108/IntR-04-2017-0162.

- Yang, L., Y. Wu, Y. Liang, and M. Yang. 2023. “Unpacking the Complexities of Emotional Responses to External Feedback, Internal Feedback Orientation and Emotion Regulation in Higher Education: A Qualitative Exploration.” Systems 11 (6): 315. doi:10.3390/systems11060315.

- Yang, M., and D. Carless. 2013. “The Feedback Triangle and the Enhancement of Dialogic Feedback Processes.” Teaching in Higher Education 18 (3): 285–297. doi:10.1080/13562517.2012.719154.