Abstract

Assessment in higher education is often a balancing act between fairness and the inherent complexity of standards, with evaluative judgement playing a crucial role in determining the quality of student work. This study employs a sociomaterial perspective to investigate the often-obscured justifications used by examiners during real-time moderation meetings, as well as their role in shaping judgements. Through participant observation and focus group interviews, a two-stage analysis was conducted. Thematic analysis identified four categories of justifications – predefined, personal, norm-based and other justifications – highlighting a range of rationales behind examiners’ grading decisions. Subsequent interaction analysis explored how these justifications inform the evaluative judgement process, revealing their role in co-constructing an understanding of fairness to reach a compromise. A key finding is that different perspectives on fairness significantly impact evaluative judgements. The study recommends the use of the concepts ‘tinkering’ and ‘rupturing’ as analytical tools to promote flexibility and harness the strengths of subjectivity while maintaining the integrity of judgements.

Introduction

Assessment in higher education is an inherently complex and subjective process. At the heart of this domain lies evaluative judgement, which is pivotal for discerning the quality and value of complex student work (Tai et al. Citation2018, 471). Here, the line between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ judgements is often blurred (Luo and Chan Citation2023), presenting a significant challenge in achieving a balance between consistent and comparable judgements while dealing with the inherent complexity of standards (Adie, Lloyd, and Beutel Citation2013, 973). This balance is crucial to upholding the integrity of the assessment process and meeting the societal demand for well-qualified professionals. Since grades are meant to reflect students’ competence levels, they impact educational and employment decisions and, in turn, individual career opportunities and societal access to skilled professionals. However, grades alone do not reveal the reasoning and negotiation behind them, leaving us partly in the dark about how decisions are made and thus the consistency and fairness of assessments. Wallander and Molander (Citation2014, 2) compared professionals’ reasoning processes to a ‘black box’, often unseen and unexamined, highlighting the need for more knowledge about these processes. Evaluative judgement in higher education remains underexplored (Tai et al. Citation2018), and limited research has investigated how examiners justify their decisions (Bloxham, Hughes, and Adie Citation2016), especially in specialised contexts such as police education.

This study investigates examiners’ evaluative judgements during real-time moderation discussions (co-grading) in the context of assessing Norwegian police students’ bachelor’s theses. In Norway, the Norwegian Police University College (NPUC) is the sole provider of police education, with the bachelor’s thesis intended as a vital tool in equipping students with knowledge-based competencies for effective policing (NPUC Citation2022a). Adopting a sociomaterial perspective, this approach emphasises the performative and situational nature of assessment. It draws on insights from Fenwick and Edwards (Citation2013) and Ajjawi, Bearman, and Boud (Citation2019) and recognises that evaluative judgement is a dynamic process shaped by human and non-human entities within specific contexts, challenging the representational view of standards as fixed. In line with these theoretical perspectives, this study uses observation data from real-time grading discussions to investigate the nature of evaluative judgement, examining how they are performed in situ.

The aim of this study is to identify the justifications used by examiners during real-time moderation meetings and to examine how these justifications influence the evaluative judgement process. The study provides insights into the reasoning behind grading decisions and their impact on examiners’ evaluative judgements. Furthermore, it provides practical insights for improving assessment practice. The research questions addressed are as follows:

What justifications do examiners use during moderation when assessing bachelor’s theses?

How do these justifications inform the evaluative judgement process?

Navigating the complexities of examiner judgement in moderation

Moderation in higher education aims to ensure consistency, reliability and evidence-based judgement in assessments (Adie, Lloyd, and Beutel Citation2013). Shay (Citation2004, Citation2005) describes the assessment of complex tasks as a socially situated interpretive act, deeply influenced by the immediate context and contingent circumstances. While traditionally conceptualised as post-judgement activities aimed at grade negotiation, moderation processes now encompass a broader spectrum of activities across different assessment stages (Bloxham, Hughes, and Adie Citation2016). The initial calibration phase aims to develop a shared understanding among examiners regarding task specifications, requirements, and assessment criteria – by evaluating student work samples. The subsequent judgement phase focuses on consensus moderation discussions to ensure judgement quality by emphasising adherence to criteria, evidence credibility and judgement consistency (Bloxham, Hughes, and Adie Citation2016, 640). Consensus moderation is a collaborative approach between examiners to develop a shared understanding of assessment standards and agree on mark allocations (Sadler Citation2013; Mason, Roberts, and Flavell Citation2022, 1). Shay (Citation2004) further clarified moderation as a critical venue for examiners to justify their judgements and resolve disputes.

The challenges of achieving fairness and consistency in assessing complex student achievement are well-documented, with Bloxham et al. (Citation2016, 479) arguing that the complexity and intuitive nature of such assessments make variability inevitable. While existing research documents variation in grading practices across time and national contexts, some findings also remain consistent across many studies. Factors influencing assessment variability include differing opinions about the quality of student work (Grainger, Purnell, and Zipf Citation2008; Rinne Citation2023), personal standards (Price Citation2005; Gynnild Citation2022) and different assessment strategies, such as norm-referencing or criterion-referencing (Sadler Citation2005; Yorke Citation2011; Bloxham and Boyd Citation2012). According to Rinne (Citation2023), examiners’ views on the achievability of assessment standards also influence grading decisions, with some adjusting expectations due to perceived gaps in students’ knowledge. Recent studies have shown that the involvement of multiple examiners does not necessarily lead to more accurate assessments (Bloxham Citation2009; Brooks Citation2012; Bloxham, Hughes, and Adie Citation2016), highlighting reported discrepancies between various examiner backgrounds (Mason, Roberts, and Flavell Citation2022; Mason and Roberts Citation2023). Despite recognising the complexities of assessment, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding the justifications behind examiners’ grading decisions. This absence may compromise the integrity of assessment practices by obscuring the factors that influence fairness and consistency. This study addresses this gap by investigating the justifications used by examiners and their impact on the evaluative judgement process. It explores how examiners apply and negotiate justifications in real-time moderation settings to reach a final-grade decision.

By employing participant observation to explore examiner justifications during real-time moderation meetings, this study further addresses a methodological gap. In their review of recent assessment and feedback research, Nieminen, Bearman and Tai (Citation2023) found that interviews and surveys/questionnaires were the predominant data collection methods. In addition to studies using interviews (e.g. Adie, Lloyd, and Beutel Citation2013; Mason and Roberts Citation2023; Rinne Citation2023), the ‘think aloud’ method has been commonly used (e.g. Crisp Citation2010; Bloxham, Boyd, and Orr Citation2011) – as it requires examiners to verbally comment on their thoughts while grading (Brooks Citation2012, 65). While these approaches provide valuable insights, they may not fully capture the complex, context-dependent judgements made during assessments. By engaging in authentic, real-time moderation settings, this study’s approach emphasises active ‘doing’ over mere ‘saying’, providing insights into how judgements are formed and enacted in specific settings.

A sociomaterial perspective: the performative dynamics of examiner judgement

This study adopts a sociomaterial perspective to explore examiners’ justifications in the moderation process. This view emphasises the interconnectedness of individual, social and material elements in professional practice to understand how knowledge and actions are enacted in everyday contexts (Fenwick and Edwards Citation2013). The sociomaterial perspective is particularly relevant for this study, as it allows for the exploration of how justifications are enacted and their influence on evaluative judgements in real-life moderation settings – providing insights into the performative nature of assessment practices in higher education. A socio-material stance has enacted practice as the analytical focal point and is therefore sensitive to variations in grading practices over time and across empirical contexts. In line with Ajjawi, Bearman and Boud (Citation2019, 2), this study does not distinguish between ‘standards’ and ‘assessment criteria’, using these terms interchangeably, as both are considered assessment tools that examiners use to evaluate student work.

Grounded in performative ontology, the sociomaterial approach challenges the representational epistemology dominant in educational research (Fenwick and Edwards Citation2013). While the established view sees standards as stable representations of intentions and expectations, the sociomaterial perspective emphasises their dynamic, performative and context-dependent nature, suggesting that they are actively enacted and co-constructed in human–material interactions (Ajjawi, Bearman, and Boud Citation2019). Bearman and Ajjawi (Citation2021, 362) illustrated the performative nature of professional standards by explaining how a nurse enacts protocol standards rather than simply following them when taking a patient’s blood pressure. While adhering to the strict protocol, the nurse simultaneously adapts to the patient’s particular situation, such as health status and restrictive clothing. Similarly, assessment criteria are dynamic entities ‘that can mobilise or constrain human action’ (Ajjawi, Bearman, and Boud Citation2019, 7). They are fluid performances shaped by the context and the actors involved, revealing their active participation in the assessment process (Bearman and Ajjawi Citation2021, 361).

Ajjawi, Bearman and Boud (Citation2019) used the terms ‘tinkering’ and ‘rupturing’ to describe the dynamic nature of standards. ‘Tinkering’ refers to ongoing, small adjustments to standards in response to specific contexts and purposes, indicating the adaptability required in different scenarios (Mol Citation2009). In contrast, ‘rupturing’ refers to significant departures from established standards, which occur when these adjustments or interpretations diverge too far from their intended application and can no longer be enacted (Law Citation2009). These concepts serve as analytical tools for understanding the elasticity of standards and the need to strike a balance between maintaining the integrity of standards and allowing for subjective and contextual flexibility. They also help examine the implications of examiners’ enactment of evaluative judgement.

Methods

Empirical context

Within Norwegian higher education, the prevailing assessment system is criterion-referenced, where student work is assessed against predefined criteria to ensure a reliable and fair assessment of student competence (University and University Colleges Act Citation2005). Policy measures to ensure assessment quality include examiner guidelines, external evaluations, and consensus moderation. This study’s participants are therefore accustomed to consensus moderation and the use of criteria. Examiners are compensated based on specific time allocations for each assignment, which may influence the thoroughness of their judgements.

In their final year, all students at NPUC write a bachelor’s thesis with the primary aim of enhancing their basic research skills (NPUC Citation2022a). This thesis constitutes 15 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System credits (ECTS) and requires students to engage with research-based and relevant sources, focusing on topics related to policing and societal phenomena (NPUC Citation2022b). Of the 435 theses assessed in spring 2022, half underwent consensus moderation, while the remainder were assessed individually. A diverse group of 60 internal and external examiners with various academic backgrounds and examiner experience evaluated these theses. This study focused on assignments that were co-graded during several observed moderation meetings. The assessment process adhered to predefined criteria including relevance, theory use, independence, method, discussion, structure, language and referencing, supplemented by a grading scale. The case of the bachelor’s thesis at NPUC offers a rich context for exploring examiners’ justifications during the moderation process, providing insights into how evaluative judgement unfolds in practice.

The initial reading of the data revealed notable variations in examiners’ individual grades prior to the moderation discussions, highlighting the importance of exploring the rationale behind these decisions. Of the assignments co-graded in the observed consensus moderation meetings, 43% showed initial grading discrepancies of at least one full grade (e.g. from B to C), with 10% varying by two grades (e.g. from B to D). Early calibration meetings revealed differences of up to three grades for identical student work.

Data and participants

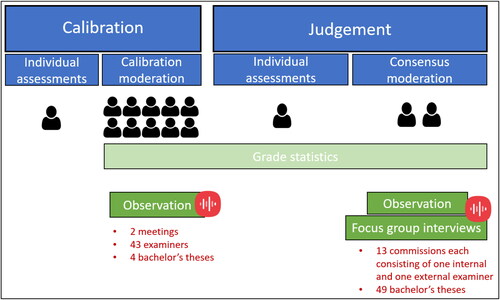

The primary data for this study were collected through participant observation of real-time moderation sessions. This included two initial calibration meetings attended by 43 internal and external examiners and 13 subsequent consensus moderation meetings, each involving one internal and one external examiner. In total, 53 theses were co-graded, with two in each calibration meeting and 49 in consensus moderation. Additionally, contextual data from focus group interviews conducted immediately after each consensus moderation meeting were used to gain deeper insights into the justifications and their impact on the evaluative process. These data are illustrated in .

All moderation meetings and focus group interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and supplemented with detailed field notes. Initial calibration meetings typically lasted about an hour, while consensus sessions varied from approximately 30 to 60 min. Additionally, focus group interviews had an average duration of up to 30 min. To minimise potential influence, the examiners were thoroughly informed of the study’s objectives beforehand and encouraged to maintain their usual assessment routines. Furthermore, the focus group interviews offered examiners an opportunity to reflect on any deviations from their standard practices.

Data analysis

The analysis involved a two-stage process to address the research questions. First, thematic analysis was used to identify and categorise the different justifications applied by the examiners. Second, interaction analysis was used to explore their impact on the evaluative judgement process in real-time moderation discussions. These approaches facilitated a comprehensive investigation of the justifications used by examiners and their impact on the evaluative judgement process. In both stages, ‘justifications’ were identified as reasons given during moderation (e.g. weak methodology chapter), and when articulated, their corresponding rationale (because…). The analysis focused on assignments that were actively discussed, as some were co-graded without discussion. This occurred, for example, in cases where the initial grades assigned by the examiners were similar. To differentiate substantial justifications from casual remarks, statements were categorised as justifications if they contained reasons that influenced the evaluative process.

The thematic analysis, drawing on Gibbs (Citation2018), involved an iterative coding of the observation and interview data, resulting in four categories of justifications: predefined, personal, norm-based and other. This process evolved from identifying initial patterns to developing more analytically and theoretically informed constructs, transforming inductive codes such as ‘lenient’ and ‘comparative’ justifications into broader concepts such as ‘personal’ and ‘norm-based’. To maintain contextual integrity, detailed information was included when categorising statements into justification types. Categories were clearly defined to ensure consistent and systematic coding (Gibbs Citation2018). Despite some overlap in category boundaries, each category captured key attributes of the justification types, making the distinction between them meaningful. Organising the justifications into these categories provided a clearer understanding of the range of reasons used by examiners when assessing student work.

Building on these thematic insights, the subsequent interaction analysis, informed by Jordan and Henderson (Citation1995) and Heath, Hindmarsh and Luff (Citation2010), explored how these justifications came into play and informed the evaluative process in moderation discussions. One unique aspect of interaction analysis is its focus on ‘situated conduct’, emphasising the role of context in shaping interactions (Heath, Hindmarsh, and Luff Citation2010). A dialogue between an internal and external examiner over a single thesis was specifically selected for its rich illustration of various justification types.

The analysis revealed that the examiners’ perspectives on fairness were central to their evaluative judgements, influencing the justifications used and the overall outcomes. In this context, ‘fairness’ refers to the participants’ own views of what is considered a reasonable basis for setting a grade. As the findings will illustrate, this can be understood as competing sets of standards, one rooted in strict adherence to established criteria and another rooted in a holistic consideration of students’ instructional contexts. This fundamental distinction emerged from the ways in which participants enacted standards using various justifications based on different perspectives on fairness.

To improve the data analysis quality, ongoing analyses were presented for peer feedback and data excerpts were shared with colleagues for critical review.

Ethical considerations

To ensure compliance with privacy regulations, an application was submitted and authorised by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT). Necessary steps were taken to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants, which included obtaining informed consent from all participants in accordance with SIKT’s guidelines. Given that the research involved colleagues at my workplace, I paid special attention to clearly communicating the project’s aim and the voluntary nature of participation, both verbally and in writing, to mitigate any concerns of coercion or being monitored.

Findings

The findings are presented in two sections, one for each research question. The first section outlines four key categories of justifications used by the examiners during moderation sessions – predefined, personal, norm-based and other – supported by representative quotes. The subsequent interaction analysis includes a dialogue between an internal and an external examiner during consensus moderation. This is followed by a detailed analysis of how their justifications influence the assessment process. Together, these sections demonstrate the evaluative judgement process during moderation, showing that reaching an agreement is an interactional process in which different types of justification are mobilised to co-construct an understanding of fairness and reach a compromise. To ensure participant anonymity and assignment confidentiality, certain details in the quotes have been modified without altering their essence. Additionally, minor parts of the dialogue in the second section have been omitted for brevity. To preserve anonymity and present findings based on data from multiple moderation meetings, examiners are labelled numerically. The quotes from examiners 1 to 11 in the first part come from seven different moderation meetings, while the interaction analysis with examiners 12 and 13 in the second part is from a separate, eighth meeting.

What justifications shape grading decisions?

Predefined justifications

The analysis revealed that the examiners’ justifications were often based on predefined criteria. This category includes justifications rooted in the published criteria for assessing bachelor’s theses at NPUC. Despite frequent citations of these criteria, their application varied in terms of interpretation and weighting. An example of interpretation inconsistencies is illustrated by the contrasting reasons of two examiners for the ‘discussion’ criterion for the same student assignment. The intended purpose of this criterion is to evaluate how well students present and discuss their findings in relation to the research question:

Examiner 1: I particularly think that the discussion section is very well done, and I can see a common thread. So, in that sense, it is a very good assignment in my opinion.

Examiner 2: I don’t think the discussion is good. In fact, I am not sure if I can find any real discussion at all.

Examiner 3: Ultimately, it is most important that they [the students] demonstrate understanding of the method, and I think that applies to all the assignments.

Examiner 4: I don’t think we should let the method chapter be what weighs the most because I know what kind of instruction they have received.

Personal justifications

This category encompasses justifications rooted in the personal opinions of examiners, diverging from and transcending predefined criteria (Bloxham et al. Citation2016). These justifications often disclose examiners’ perspectives on fairness and their influence on the evaluative process and its outcomes. This can be further exemplified by Examiner 5’s justification of prioritising systemic issues over individual student performance:

Examiner 5: We can hardly deduct [the grades] for those poor method chapters because it is so widespread that there must be a systemic error there. (…) That is the standard, and then we can hardly start penalising them [the students] for it.

Examiner 6: These are the toughest cases. Should we give the candidate the benefit of the doubt and bump them up, or should we strictly adhere to the criteria and say that we need to be tough and give a C?

Norm-based justifications

Norm-based assessment, often termed ‘grading on the curve’, involves comparing student work with that of others, as opposed to criterion-based assessment, which dominates contemporary higher education, where student performance is measured against predefined standards (Sadler Citation2005, 178). In this study, norm-based justifications evaluate students’ work against the work of others, prioritising comparative ranking over adherence to specific standards. Such justifications were frequently used, particularly for calibration purposes, as illustrated by Examiner 7’s comment:

Examiner 7: This was the first one. I always find that it is a bit difficult when it is the first assignment. I should… I haven’t done that… go back and look at the first ones again. But when I read the first one, it is always difficult to calibrate immediately.

Examiner 8: I struggle a bit to give this one a better grade, especially since I have another assignment that I have given a C, which uses (…) much better.

Examiner 9: Yes. And it was clearly much worse than the two that have now received a B.

Examiner 8: Yes, it was.

Other justifications

This category was included to accommodate reasons that do not fit into the previous categories. It includes justifications that influence grading decisions but are not related to predefined criteria. An example of this occurred during a consensus moderation session. After discussing a student’s work, focusing on weaknesses such as a lack of critical reflection (noted by Examiner 10) and a poorly executed methodology section (noted by Examiner 11), the examiners were faced with a decision between grades ‘C’ and ‘D’. Both grades seemed lenient in relation to the predefined criteria and the general criticisms raised by the examiners during their dialogue. However, these grade options, which were in line with the examiners’ initial judgements, were the only ones they gravitated towards. In making their final decision, the examiners deviated from strictly academic considerations and instead invoked notions of ‘goodwill’ and ‘humanity’ as the deciding factor for the higher grade. A justification from the ‘other’ category became the final word on the matter:

Examiner 10: But it is much nicer for a person to get a C than a D.

Examiner 11: It is nice - definitely.

Examiner 10: So, let’s go with that then.

Co-constructing fairness to reach agreement through the mobilisation of justifications

The analysis so far has illustrated that examiners use a range of justifications as they engage in evaluative judgement. The next section analyses how these justifications inform evaluative judgement by examining a dialogue between two examiners in a consensus moderation meeting. This interaction analysis demonstrates how various justifications are used to construct an understanding of fairness to reach a reasoned compromise. It also illustrates how the assessment criterion that emphasises methodological rigour is reinterpreted within a holistic perspective considering students’ instructional contexts.

The meeting starts with the two examiners sharing their initial grades, with Examiner 12 having set a B and Examiner 13 a C. They briefly discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the thesis with reference to the predefined criteria and agree that the theoretical understanding is strong but the methodology section is weak. At this point, the examiners have a similar interpretation of the assignment quality, agreeing that the grade difference lies in the weighting of the methodology. This sets the stage for the following discussion:

(1) Examiner 12: I have not emphasised it [the methodology chapter], you see, because I think it is so terrible all the way through, that [if I emphasised it] then I could not have given any Bs.

(2) Examiner 13: No [laughs]

(3) Examiner 12: There are maybe two… out of all the assignments I have read, there might be two good methodology chapters.

(4) Examiner 13: Yes.

(5) Examiner 12: To put it this way, and…, so, I know that it is a bit like swearing in church, because there are those who believe that the methodology chapter should be very important.

(6) Examiner 13: Mm.

(7) Examiner 12: But when it is this poor, I almost feel it is a bit wrong to judge people based on it.

(8) Examiner 13: Mm

(9) Examiner 12: So, if people write about source criticism or pre-understanding, for example, emphasising its importance (…), and that is all there is…, is that more valuable than writing nothing at all?

(10) Examiner 13: No.

(11) Examiner 12: I mean, I cannot really differentiate, it does not seem like the methodology is integrated knowledge for almost any of these students.

(12) Examiner 13: Yes, it is not.

(13) Examiner 12: It turns into such a superficial way of understanding methodology, the research process, and academic process, sort of like it is just tacked on.

(14) Examiner 13: Yes, they do not really understand what they are writing about. They mix terms and… They know they should use words like pre-understanding, qualitative, and quantitative, but they use them incorrectly.

Examiner 12 persistently mobilises norm-based justifications, referring to the student theses and their general superficial engagement with methodology (lines 9 and 11). Following this, Examiner 13’s initial adherence to predefined criteria gives way to an acknowledgement of instructional deficiencies that contribute to students’ misinterpretation of key research terminology (line 14). This shift demonstrates that the methodological standard is an active participant in the interaction, shaped by other actors such as the examiners, assessment criteria, the student work being assessed and other students’ work. In the final section of the dialogue, this perspective on fairness that has been collectively constructed throughout the interaction culminates in a compromise, essentially a ‘rupture’.

(15) Examiner 12: So that is why I think maybe the difference between you and me regarding this assignment is that I have not emphasised the methodology… the weakness in the methodology chapter, and then I still gave it a B.

(16) Examiner 13: Mm. Yes, because then…

(17) Examiner 12: So, I agree that the methodology chapter is not good… enough… because it should have been better to be a B, but can you accept that we give the student the benefit of the doubt and give it a B?

(18) Examiner 13: Yes, we can do that. Because…, yes, we can do that…, because what I have critiqued here is about the methodology.

(19) Examiner 12: But is it okay for you that we don’t emphasise it that much?

(20) Examiner 13: I can agree to that. We have just lowered the grades of the other ones, so…

Examiner 12 ends the dialogue by acknowledging that their differences are merely a matter of emphasis on methodology (line 15), suggesting leniency and de-emphasis on methodology due to quality concerns (lines 17 and 19). This highlights the tension between the two perspectives on fairness at play: strict adherence to predefined criteria or a more holistic consideration of wider instructional challenges. The dialogue culminates in a ‘rupture’ when Examiner 13 agrees with Examiner 12’s perspective and a B grade, citing the lowering of grades for other assignments (‘norm-based’) (line 20). Such a large deviation indicates that the predefined standard was not applied in accordance with its intended flexibility.

In summary, this analysis demonstrates the different justifications and perspectives on fairness that come into play during moderation. The examiners mobilise certain justifications while downplaying others to reach a compromise informed by specific perspectives on fairness. In this dialogue, the examiners construct an agreed-upon understanding of why it is reasonable and acceptable to deviate from the assessment standards. This demonstrates that the deviation is a deliberate and rational decision which is based on a careful reconstruction of the significance of the pre-defined criteria.

Discussion and implications

This study investigates a crucial yet often overlooked aspect of examiners’ evaluative judgement, contributing both empirically and methodologically to the research field by providing insights into the justifications behind grading decisions and how these inform evaluative judgements using observational data from real-time moderation settings. While previous research has highlighted variability in judgement (e.g. Read, Francis, and Robson Citation2005; Grainger, Purnell, and Zipf Citation2008; Bloxham et al. Citation2016), this study enriches these insights by demonstrating that reaching an agreement during moderation is an interactional process where different types of justifications are mobilised to co-construct an understanding of fairness and arrive at a compromise.

Shay (Citation2004) distinguished between ‘consensus’ and ‘agreement’, as these terms were defined by Moss and Schutz (Citation2001). While ‘consensus’ assumes a uniform understanding among all parties, ‘agreement’ implies that all parties accept a particular outcome within a given context, even though they might interpret it differently (Moss and Schutz Citation2001). This study’s use of observational data captures the real-time co-construction of evaluative judgements. This suggests that the moderation outcome aligns more closely with ‘agreement’ than with ‘consensus’, emphasising both methodological and conceptual implications. The added value of the observational methodology used in this study lies in its unique ability to capture the intricate details of interactions, which would not be apparent without this approach. This reveals that the path to a grading decision is complex and nonlinear, unfolding as a negotiated journey towards an agreement that reflects a collective yet diverse interpretation of the student’s work quality. Examiners often move beyond the boundaries of predefined criteria and mobilise various justifications to co-construct rational explanations for their judgements. This does not indicate incompetence or unawareness of assessment standards but rather a deliberate effort to ensure fairness and adapt judgements to the realities of the instructional landscape.

A central finding of this study is the significant impact of different perspectives on fairness in the evaluative process. The observational data enabled the tracing of these perspectives, which kept resurfacing in the discussions, highlighting their central role in the interactional process, leading to an agreement. While the discussions often revolved around leniency versus strictness, this study suggests an alternative framing in that it is more a matter of competing sets of standards: one based on strict adherence to predefined criteria and another more holistic consideration of students’ instructional context. Fundamentally, both approaches involve standards being performed through various rationalisations based on different perspectives on fairness – illustrating the added value of the sociomaterial lens applied in this study. These findings resonate with Rinne’s (Citation2023) insights into a connection between the examiners’ perceptions of academic standards and their grading stringency. This pursuit of fairness reveals a paradox where examiners, in an effort to accommodate instructional shortcomings by enacting standards leniently, may inadvertently compromise assessment integrity. Overlooking, or rupturing, the methodological criterion directly contradicts the main aim of the bachelor’s thesis in policing – to develop students’ basic research skills (NPUC Citation2022a) – and strays from emphasising the crucial competencies that society expects from police professionals. This paradox echoes the concerns raised by Bloxham, Hughes and Adie (Citation2016) and Bloxham (Citation2009) about the effectiveness of moderation in ensuring quality assurance. While variability in assessments may be inevitable due to their complex and intuitive nature (Yorke Citation2011; Bloxham et al. Citation2016), this does not warrant an ‘anything goes’ approach.

Ensuring the professional readiness of graduates, especially in pivotal professions such as policing, is a societal imperative. Leniency in the application of assessment criteria not only risks undermining assessment quality but may also fall short of meeting society’s broader expectations for professional competence – highlighting the need for a structured approach to evaluative judgement. In this context, the terms ‘tinkering’ and ‘rupturing’ are helpful analytical tools to balance fairness and complexity, aligning with Ajjawi, Bearman and Boud (Citation2019) and Shay (Citation2004) on valuing diversity in moderation and with Grainger, Purnell and Zipf (Citation2008) on fostering a shared language through professional discussions around real student work. These concepts facilitate discussions about criterion elasticity and boundaries, which are particularly useful in early calibration moderation sessions (Ajjawi, Bearman, and Boud Citation2019). Practical steps might include examiner discussions grounded in the assessment of specific student works to identify acceptable levels of tinkering and pinpoint ruptures that deviate too far from established criteria. Furthermore, in light of this study’s findings, addressing different fairness perspectives and their impact on judgements early, rather than leaving them to be resolved by small groups in subsequent consensus moderation without prior discussion, is essential. By engaging in calibrating discussions about what is considered fair and why, the examiners can explore the range of justifications applied as they enact and re-enact standards, talk about their relevance and clarify decision boundaries. For example, discussing the consequences of overlooking a weak methodology section due to inadequate instruction can assist examiners in identifying and mitigating subsequent ruptures that threaten to undermine overall fairness. A structured approach to discussing the flexibility and limitations of the standards can help examiners develop a common understanding of acceptable criteria elasticity and effectively balance fairness and complexity. This method encourages different interpretations, harnessing the power of subjectivity while maintaining the integrity of the assessment process.

Finally, gaining insights into the black box of examiners’ justifications can reveal valuable information, such as systemic challenges that call for adjustments to be better aligned with instructional realities. This highlights the importance of feeding this knowledge back into the system. The discovery of competing sets of standards stemming from different perspectives on fairness requires action, such as enhanced instructional training or the potential exclusion of the criterion from the guidelines. Once the assessment stage has been reached, it is too late to make adjustments to the assessment criteria or instructional practices. Therefore, it is essential to establish a feedback loop to incorporate moderation insights into instructional designs for the constructive reintegration of this knowledge into the system.

Future research should explore the nuances of examiners’ evaluative judgements across various disciplines. Investigating ‘tinkering’ and ‘rupturing’ as methods for structuring examiner dialogues and clarifying criteria elasticity could provide valuable insights into bridging the gap between fairness and complexity. Additionally, future research should explore students’ perceptions of the validity of the grading process, as they may differ from examiners’ perceptions.

Limitations

This qualitative study was conducted within a specific institution, limiting its generalisability. However, the use of multiple methods (participant observation and focus group interviews) and a rich dataset (field notes, audio recordings and transcripts) strengthens the study’s quality. Awareness of being observed may have influenced the participants’ behaviour. To mitigate this, the participants were thoroughly informed about the study’s objectives and encouraged to maintain their usual assessment routines. Transparency about theoretical and methodological choices and using a rich dataset facilitated analytical generalisability. The study does not include students’ views.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the examiners who generously devoted their time to participate in this study. The author would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable input to earlier versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christine Sætre

Christine Sætre is a PhD Research Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Professions at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. She is also a teacher and police superintendent at the Norwegian Police University College (NPUC). Her research interests include higher education assessment, specifically evaluative judgement and moderation processes in the assessment of complex student work.

References

- Adie, L., M. Lloyd, and D. Beutel. 2013. “Identifying Discourses of Moderation in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (8): 968–977. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.769200.

- Ajjawi, R., M. Bearman, and D. Boud. 2019. “Performing Standards: A Critical Perspective on the Contemporary Use of Standards in Assessment.” Teaching in Higher Education 26 (5): 728–741. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1678579.

- Bearman, M., and R. Ajjawi. 2021. “Can a Rubric Do More than Be Transparent? Invitation as a New Metaphor for Assessment Criteria.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (2): 359–368. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1637842.

- Bloxham, S. 2009. “Marking and Moderation in the UK: False Assumptions and Wasted Resources.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (2): 209–220. doi:10.1080/02602930801955978.

- Bloxham, S., and P. Boyd. 2012. “Accountability in Grading Student Work: Securing Academic Standards in a Twenty-First Century Quality Assurance Context.” British Educational Research Journal 38 (4): 615–634. doi:10.1080/01411926.2011.569007.

- Bloxham, S., P. Boyd, and S. Orr. 2011. “Mark My Words: The Role of Assessment Criteria in UK Higher Education Grading Practices.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (6): 655–670. doi:10.1080/03075071003777716.

- Bloxham, S., B. den-Outer, J. Hudson, and M. Price. 2016. “Let’s Stop the Pretence of Consistent Marking: Exploring the Multiple Limitations of Assessment Criteria.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (3): 466–481. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1024607.

- Bloxham, S., C. Hughes, and L. Adie. 2016. “What’s the Point of Moderation? A Discussion of the Purposes Achieved Through Contemporary Moderation Practices.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (4): 638–653. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1039932.

- Brooks, V. 2012. “Marking as Judgment.” Research Papers in Education 27 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1080/02671520903331008.

- Crisp, V. 2010. “Judging the Grade: Exploring the Judgement Processes Involved in Examination Grading Decisions.” Evaluation & Research in Education 23 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1080/09500790903572925.

- Fenwick, T., and R. Edwards. 2013. “Performative Ontologies. Sociomaterial Approaches to Researching Adult Education and Lifelong Learning.” European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 4 (1): 49–63. doi:10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela0104.

- Gibbs, G. R. 2018. “Analyzing Qualitative Data.” In The SAGE Qualitative Research Kit. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Grainger, P., K. Purnell, and R. Zipf. 2008. “Judging Quality through Substantive Conversations between Markers.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 33 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1080/02602930601125681.

- Gynnild, V. 2022. “«Jeg Tror Jeg Brukte Den Som Taus Kunnskap, Om Du Skjønner Meg»: En Studie Av Sensurveiledning På Bachelornivå.” Uniped 45 (1): 39–52. doi:10.18261/uniped.45.1.5.

- Heath, C., J. Hindmarsh, and P. Luff. 2010. Video in Qualitative Research: Analysing Social Interaction in Everyday Life. Los Angeles, California: Sage.

- Jordan, B., and A. Henderson. 1995. “Interaction Analysis: Foundations and Practice.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 4 (1): 39–103. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2.

- Law, J. 2009. “Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics.” In The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, edited by B. S. Turner, 141–158. West Sussex: Blackwell.

- Luo, J., and C. K. Y. Chan. 2023. “Conceptualising Evaluative Judgement in the Context of Holistic Competency Development: Results of a Delphi Study.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (4): 513–528. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2088690.

- Mason, J., L. D. Roberts, and H. Flavell. 2022. “Consensus Moderation and the Sessional Academic: Valued or Powerless and Compliant?” International Journal for Academic Development 28 (4): 468–480. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2022.2036156.

- Mason, J., and L. D. Roberts. 2023. “Consensus Moderation: The Voices of Expert Academics.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (7): 926–937. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2161999.

- Mol, A. 2009. “The Art of Medicine: Living with Diabetes: Care Beyond Choice and Control.” The Lancet 373 (9677): 1756–1757. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60971-5.

- Moss, P., and A. Schutz. 2001. “Educational Standards, Assessment, and the Search for Consensus.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (1): 37–70. doi:10.3102/00028312038001037.

- Nieminen, J. H., M. Bearman, and J. Tai. 2023. “How is Theory Used in Assessment and Feedback Research? A Critical Review.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2047154.

- NPUC. 2022a. Sensorveiledning for Bacheloroppgaven Politihøgskolen Vår 2022. Oslo: Politihøgskolen.

- NPUC. 2022b. Strategi 2022-2025. Oslo: Politihøgskolen.

- Price, M. 2005. “Assessment Standards: The Role of Communities of Practice and the Scholarship of Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (3): 215–230. doi:10.1080/02602930500063793.

- Read, B., B. Francis, and J. Robson. 2005. “Gender,‘Bias’, Assessment and Feedback: Analyzing the Written Assessment of Undergraduate History Essays.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (3): 241–260. doi:10.1080/02602930500063827.

- Rinne, I. 2023. “Same Grade for Different Reasons, Different Grades for the Same Reason?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 49 (2): 220–232. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2203883.

- Sadler, D. R. 2005. “Interpretations of Criteria-Based Assessment and Grading in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (2): 175–194. doi:10.1080/0260293042000264262.

- Sadler, D. R. 2013. “Assuring Academic Achievement Standards: From Moderation to Calibration.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 20 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2012.714742.

- Shay, S. 2004. “The Assessment of Complex Performance: A Socially Situated Interpretive Act.” Harvard Educational Review 74 (3): 307–329. doi:10.17763/haer.74.3.wq16l67103324520.

- Shay, S. 2005. “The Assessment of Complex Tasks: A Double Reading.” Studies in Higher Education 30 (6): 663–679. doi:10.1080/03075070500339988.

- Tai, J., R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, P. Dawson, and E. Panadero. 2018. “Developing Evaluative Judgement: Enabling Students to Make Decisions About the Quality of Work.” Higher Education (00181560) 76 (3): 467–481. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3.

- University and University Colleges Act. 2005. “Ministry of Education and Research.”

- Wallander, L., and A. Molander. 2014. “Disentangling Professional Discretion: A Conceptual and Methodological Approach.” Professions and Professionalism 4 (3): 1. doi:10.7577/pp.808.

- Yorke, M. 2011. “Summative Assessment: Dealing with the ‘Measurement Fallacy.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (3): 251–273. doi:10.1080/03075070903545082.