Abstract

Traditional assessment methods in tertiary education may not suit students’ diverse learning needs, values, and preferences. Co-designing assessment with students may engage them more effectively. This scoping review determined assessment co-design processes employed in tertiary education, evaluated the impacts on student learning outcomes and key factors contributing to effective assessment co-design. Seven databases were searched, limited to human studies in English language published between 2003–2023, with records screened by two reviewers. Data were presented in tabular form and a narrative synthesis. From 6233 records identified, 51 articles were included. Three main assessment co-design processes were: co-design of assessment rubrics and marking criteria; assessment co-design with larger student groups (e.g. via multiple-choice question pools and co-creation workshops); and intensive assessment co-design with smaller groups. Positive student outcomes included increased assessment literacy, student autonomy, engagement and interest and development of professional and learning skills. Staff support and effective communication between team members were some key enablers, while some barriers included time constraints and student resistance to participation. There were diverse co-design processes and outcomes from assessment co-design across disciplines. Future research should prioritise assessment co-design with international students for inclusion and equity and graduate students to accommodate advanced learning skills.

Background

Evolution in tertiary education settings has seen a shift away from traditional staff-led teaching methodologies in favour of a participatory approach, with students as active contributors in their education (Martel and Garcías Citation2022). Student-staff partnership has emerged as part of a broader pedagogical shift to make learning more accessible and inclusive across a range of disciplines (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Meijer et al. Citation2020). In this context, partnership is defined as a process whereby students and staff collaborate to promote enhanced learning outcomes, teaching processes and student engagement (Cook-Sather Citation2014; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014). Students can be engaged as partners in four interrelated domains of education including: (a) learning, teaching and assessment, (b) curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy, (c) research and (d) scholarship of teaching and learning (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014).

Assessments in tertiary education are an important part of evaluating both student understanding and knowledge and the effectiveness of teaching processes to support learning. However, traditional assessment processes often do not fulfil their goal of significantly influencing student learning due to inadequate transparency in assessment criteria, which can lead to poor student understanding of marking criteria and assessment outlines (Bloxham and West Citation2004; Dawson Citation2017; Bearman and Ajjawi Citation2018; Jönsson and Prins Citation2019). This can result in student difficulties and dissatisfaction in understanding how to apply feedback to further learning and assessment (Rust, O’Donovan, and Price Citation2005; Blair and McGinty Citation2013; Carless and Boud Citation2018). Additionally, traditional assessment methods may not cater to the diversity in learning styles, preferences, skillsets, and knowledge backgrounds of students (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017). Therefore, staff-student partnership in the co-design of assessment tasks may present an opportunity to not only assess student knowledge, but to engage students in further learning (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017). Such collaborative practice has been shown to be valuable in preparing students to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical, real-world application whilst also enhancing their learning outcomes (Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021).

Active student engagement in assessments and learning confer valuable benefits for both staff and students (Blackie, Case, and Jawitz Citation2010; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). Co-designing assessment tasks with tertiary education students in non-health science disciplines has been reported to increase students’ understanding of assessment tasks and marking criteria, support intrinsic motivation, engagement and confidence, foster a learning community between students and staff whilst developing students’ professional skillset (Bovill, Felten, and Cook-Sather Citation2014; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Blau and Shamir-Inbal Citation2018). However, some students and staff are hesitant to fully engage with the process perceiving a high amount of risk and uncertainty due to the unfamiliar learning environment whilst select students consider the process to be a source of further academic stress (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Blau and Shamir-Inbal Citation2018).

At present, no reviews have been conducted investigating the co-design of assessment tasks within health science disciplines. For this review, initial searches focussing on assessment co-design in the health sciences yielded insufficient results to conduct a comprehensive scoping review. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review was extended to explore the processes employed in co-designing assessments across all tertiary education disciplines and evaluate its impact on student learning outcomes and the key factors that contribute to effective or ineffective assessment co-design. This scoping review also seeks to apply this body of research to the health science field to inform the implementation of future co-design projects.

Methods

This scoping review was guided by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews (Aromataris and Munn Citation2020) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al. Citation2018). The protocol was published on the Open Science Framework platform: https://osf.io/d46ku/. The research team undertaking this review included both current university students from a health discipline (Nutrition and Dietetics) and academic staff teaching within the discipline.

Search strategy & sources

Using the PCC (Population/Concept/Context) format, a preliminary pilot search of MEDLINE and Education Source specific to the health science disciplines yielded limited results necessitating a broader scope to consider higher or tertiary education. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy for seven primary electronic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Eric, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Scopus, and Education Source. The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was adapted for each included database and/or information source. The reference list of all included sources of evidence were also screened for additional studies. The language was restricted to English for ease of identification and feasibility with time restricted to the past 20 years due to the recent emergence of staff-student partnerships within tertiary education. A copy of the search strategy for one database, Eric, is provided (Supplementary Table 1).

Study/source of evidence selection

Retrieved articles were exported into Endnote 20 citation management software (Clarivate Analytics, USA) to manage citations and remove duplicates. These citations were then imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) to manage screening and selection of studies. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (AS & LM) for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. The full texts of selected citations were assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 2): human studies, English language, original research articles and review articles describing the co-design process and/or impact in tertiary education by both reviewers with exclusions recorded and reported with reasons. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion with an additional reviewer/s. The results of the search and the study inclusion process were reported in full in the present scoping review and presented in a PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Tricco et al. Citation2018; Page et al. Citation2021).

Data extraction and analysis

Using a customised data extraction tool in Microsoft Excel, two independent reviewers (AS & LM) extracted data on: first author, year, country, study design and population characteristics (e.g. discipline, number of participants). The primary outcome was the processes or methods for co-design of assessments and secondary outcomes included factors that were enablers or barriers to effective co-design of assessments, and the impact of co-designing assessments on student learning outcomes. Relevant results were reported as tabular and textual narrative summary identifying content related to this review’s objectives.

Results

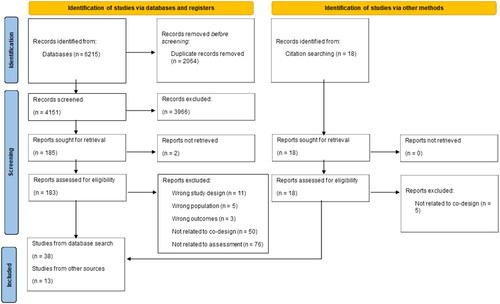

The full search yielded 6215 records from databases, and an additional 18 records included from citation searching (). Following removal of duplicates (n = 2064) and exclusions from title and abstract screening (n = 3966), a total of 201 articles were screened by full text, resulting in a final total of 51 articles included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA-ScR flow chart outlining record identification and study selection (Page et al. Citation2021).

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Of the included studies, there were 37 qualitative (Baerheim and Meland Citation2003; Brown and Murti Citation2003; Stephenson Citation2006; Tiew Citation2010; Papinczak et al. Citation2011; Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Peseta et al. Citation2016; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Leslie and Gorman Citation2017; Rivers et al. Citation2017; Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018; Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Hussain et al. Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Bovill Citation2020; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Meinking and Hall Citation2020; Ruskin and Bilous Citation2020; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021; Cosker et al. Citation2021; Curtin and Sarju Citation2021; Keeling et al. Citation2021; Matthews and Cook-Sather Citation2021; Morton et al. Citation2021; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023; Wallin Citation2023), nine quantitative (Biddix Citation2013; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Chamunyonga et al. Citation2018; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018; Chase Citation2020; Kaur and Noman Citation2020; Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Zwolski Citation2021; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023), and two mixed-methods design (Quesada et al. Citation2019; Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022). Two studies employed a longitudinal design (Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Aidan Citation2020), and one study was a systematic review (Chan and Chen Citation2023).

Of the 51 studies, the countries publishing most on assessment co-design were Australia, UK and USA, with 14 originating from Australia (Papinczak et al. Citation2011; Peseta et al. Citation2016; Rivers et al. Citation2017; Chamunyonga et al. Citation2018; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Ruskin and Bilous Citation2020; Matthews and Cook-Sather Citation2021; Morton et al. Citation2021; Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022), 14 originating from the UK (Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Leslie and Gorman Citation2017; Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Hussain et al. Citation2019; Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019; Bovill Citation2020; Curtin and Sarju Citation2021; Zwolski Citation2021; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023), and eight from the USA (Brown and Murti Citation2003; Biddix Citation2013; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Chase Citation2020; Meinking and Hall Citation2020; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021; Keeling et al. Citation2021). Seven studies were conducted in Asian countries, such as China, Hong Kong and Malaysia (Tiew Citation2010; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Kaur and Noman Citation2020; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Chan and Chen Citation2023; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023).

Only four studies of the 51 studies involved co-design with graduate students (Brown and Murti Citation2003; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Kaur and Noman Citation2020), four did not report on the level at which the students were studying (Biddix Citation2013; Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Chan and Chen Citation2023), while the remaining 43 studies involved undergraduate students. Participants consisted of students (n = range 2–470), staff (n = range 1–44), graduate teaching assistants, and former students. Four studies considered the cultural diversity of students by including students from linguistically diverse backgrounds (Tiew Citation2010; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023).

Most studies involving assessment co-design were from academic disciplines outside science or health (n = 32), including business, teaching, writing, and law (Brown and Murti Citation2003; Stephenson Citation2006; Tiew Citation2010; Biddix Citation2013; Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Leslie and Gorman Citation2017; Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Hussain et al. Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Aidan Citation2020; Bovill Citation2020; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kaur and Noman Citation2020; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021; Keeling et al. Citation2021; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Zwolski Citation2021; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023; Wallin Citation2023; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023). In total, five studies addressed health science-related disciplines, such as medicine and radiography (Baerheim and Meland Citation2003; Papinczak et al. Citation2011; Chamunyonga et al. Citation2018; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018; Cosker et al. Citation2021) and three studies examined science disciplines, such as chemistry, molecular genetics and plant-science (Rivers et al. Citation2017; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Curtin and Sarju Citation2021). Furthermore, nine studies were conducted within multi-disciplinary fields, which included one paper with only science and health science-related disciplines (Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022) and seven papers that were situated in a combination of science, health science and other academic disciplines (Peseta et al. Citation2016; Chase Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Meinking and Hall Citation2020; Ruskin and Bilous Citation2020; Morton et al. Citation2021; Chan and Chen Citation2023), and one paper which was multi-disciplinary but did not report on the specific disciplines covered (Matthews and Cook-Sather Citation2021). Two papers did not report on the discipline their assessment co-design was conducted in (Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022).

Processes used in assessment co-design

A summary of the findings of all studies has been included in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

Assessment rubric co-design

The most popular method of assessment co-design involved students co-developing marking criteria and rubrics for assessing their work (n = 24). As co-designers, students collaborated with peers and staff to develop marking criteria based on the course’s learning outcomes, graduate competencies, student and staff feedback or quality standards (Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023). A range of tools and frameworks were used to guide the rubric co-design process, whether that be original, staff designed marking rubrics (Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Chase Citation2020; Joseph et al. Citation2020), unit learning outcomes, consolidated research on effective rubric design, frameworks set out by professional bodies (Joseph et al. Citation2020), or previous student work (Smith et al. Citation2023). Three assessment marking tools, a new marking matrix, a refined ‘design review’ and a ‘lexicon’ based on the unit’s learning outcomes and previous students’ work were created by students studying architecture (Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018), whilst a new set of criteria based on staff and student feedback, quality standards and benchmarking other assessment criteria were developed by students from a business course (Smith et al. Citation2023). Implementation of the latter involved faculty training on implementing the criteria into marking rubrics and delivering linked feedback.

Students also devised marking criteria by reconstructing previous criteria according to their perceived importance or understanding. For example, business students were given one week to recreate the course’s original, staff-written marking criteria in their own words, and then these versions were compared and evaluated to create a third final version (Meer and Chapman Citation2014). Similarly, science technology engineering and mathematics (STEM) students co-designed marking criteria based on skills they perceived to be important in one study (Chase Citation2020), while in another study students re-designed marking criteria by utilising several sources, including research on effective characteristics of assessment rubrics, the unit’s learning outcomes and current and original rubric, and the Australian Qualifications Framework (Joseph et al. Citation2020). Students and staff were also consulted by rubric experts to assist in the process (Joseph et al. Citation2020).

Assessment co-design with larger student groups

Implementation of assessment co-design in larger student groups (considered to be medium to large groups – defined as over 50 students (Cash et al. Citation2017) was observed in 15 studies, where all students within a class or cohort were involved. One process for large student groups applied by two studies (Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022) (159 and 240 students, respectively) was assigning business students a topic and instructing the students on how to construct multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and possible answers and workings. These MCQ were marked and ‘sanitised’ by the lecturer and then posted for student revision, with some then included in the final exam. Focus groups were used by another study of 114 students studying teaching to inform the design of an assessment and associated forms and rubrics that staff and students collaborated on, which addressed issues and experiences the students had towards inclusive and fair assessments and group work assessments (Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017). An interactive co-creation workshop was conducted with a cohort of plant science students. During the workshop, the students collaborated with academics to gather feedback and preferences and create a suite of assessments for a new university course (Snelling et al. Citation2019). In this approach, groups of students and academics discussed various aspects of assessments including the ‘pros and cons’, type, design, and timing to establish the ‘problem’, with each group collaboratively designing an assessment task that met the needs of both staff and students as well as the learning outcomes. Prototypes of the relevant assessment tasks were then created.

Assessment co-design with smaller student groups

Intensive collaboration with smaller groups of student representatives for assessment co-design was applied in 11 studies in this review. Law students were involved in discussion and evaluation to refine an assessment criteria drafted by academics (Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019). Students then collaborated with academics to develop an unofficial ‘street’ version of the criteria utilising simple language to assist students in better understanding the assessment criteria. In another study, two small groups of first-year chemical engineering students created a MCQ quiz (Chadha et al. Citation2022). The first group (n = 7) worked collaboratively with each other designing MCQs from their course notes and own research. The second group (n = 8) completed the same co-design task; however, the students were led by two final-year students to mitigate power discrepancies within the group. Other methods of assessment co-design include involving student representatives who co-design assessment and feedback practices with academics in a two-day intensive workshop and then co-created a plan for the implementation and evaluation of this new model (Matthews and Cook-Sather Citation2021).

In a study conducted with microelectronics systems students, three former students co-designed an assessment task and marking rubric with academics for the current cohort of students following a four tier-framework (Hussain et al. Citation2019). In assessment tier 1, the former students co-designed an assessment and rubric, guided by instructor feedback. In assessment tier 2, the co-designed rubric was used by the current cohort of students to peer assess their fellow students. The former students also assessed the students using the rubric to verify the marking criteria. In feedback tier 1, the former students delivered individual feedback to each student and generalised feedback pointers to clusters of students grouped by performance. In feedback tier 2, the instructor provided a pseudo-personalised feedback video addressing each feedback cluster.

Assessment co-design with health science students

Assessment co-design with health science students were reported in five sole discipline studies and seven multidisciplinary studies. In a mixed-methods study (Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022), students created an educational product as part of a foundational genetics course for students from a range of health disciplines, including medical sciences and nutrition and dietetics. Students designed the assessment approach, choosing their topic and audience from a pre-determined list. Students also developed two unique marking criteria for peer-reviewing other group members. Guiding nursing and radiography students with a list of effective rubric characteristics and instructional protocols is another method of assessment co-design with academics, where the assessment rubrics are then applied in the following semester (Morton et al. Citation2021). In studies conducted with cohorts of radiography (Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018) and medical (Baerheim and Meland Citation2003; Papinczak et al. Citation2011) students, they were asked to develop and submit their MCQ or short answer questions (SAQs) for study purposes or for the final examination. Another study, engaged radiography students in a series of semi-structured focus groups with academics to firstly nominate two preferred assessment formats and develop a brief description of each task and then to identify benefits, challenges and logistics of implementation (Chamunyonga et al. Citation2018). Among medical students, co-design was embraced for developing scenarios for a practical simulation style assessment task (Cosker et al. Citation2021). Students were trained on this style of examination after which each tutor partnered with five students to co-design a medical scenario based on the 3rd year curriculum. Students were then involved in practice simulation sessions where they played the role of physician, patient, or evaluator.

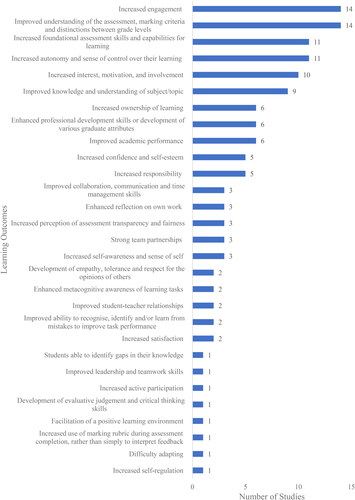

Student learning outcomes as a result of assessment co-design

There were numerous positive impacts of assessment co-design on student’s learning outcomes, as presented in & Supplementary Table 5. A key outcome noted was increased student engagement (n = 14) (Brown and Murti Citation2003; Tiew Citation2010; Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Chamunyonga et al. Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Aidan Citation2020; Bovill Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Curtin and Sarju Citation2021; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023). There was also improved assessment literacy, for example improved understanding of the assessment itself, marking criteria and distinctions between grade levels (n = 14) (Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Leslie and Gorman Citation2017; Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Aidan Citation2020; Chase Citation2020; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022), as well as increased foundational assessment skills and capabilities for learning (n = 11) (Biddix Citation2013; Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Hussain et al. Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kaur and Noman Citation2020; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023), though there was only one study which found that students used the marking rubric more during assessment completion, rather than simply to interpret feedback (Joseph et al. Citation2020).

Increased autonomy and sense of control over learning was also identified in various studies within this review (n = 11) (Stephenson Citation2006; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Hutchings, Jankowski, and Baker Citation2018; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Aidan Citation2020; Chase Citation2020; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Kaur and Noman Citation2020; Wang and Lee Citation2021; Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022). Many studies also found that the co-design process increased students’ interest, motivation and involvement (n = 10) (Tiew Citation2010; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Andrews, Brown, and Mesher Citation2018; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Aidan Citation2020; Bovill Citation2020; Ruskin and Bilous Citation2020; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021). Moreover, improved knowledge and understanding of the subject/topic was another well-noted outcome in several studies (n = 9) (Biddix Citation2013;Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018; Bell et al. Citation2019; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Wallin Citation2023; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023). Improved academic performance was also reported (n = 6) (Baerheim and Meland Citation2003; Meer and Chapman Citation2014; Leslie and Gorman Citation2017; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Bovill Citation2020; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022).

Three studies reported development of strong team partnerships (n = 3) (Brown and Murti Citation2003;Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Colson, Shuker, and Maddock Citation2022), as well as improved collaboration, communication, and time management skills (n = 3) (Zhao, Zhou, and Dawson Citation2021; Martel and Garcías Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023). Two studies noted the development of empathy, tolerance, and respect for others’ opinions (n = 2) (Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Martel and Garcías Citation2022), with another two reporting improved student-teacher relationships (n = 2) (Quesada et al. Citation2019; Wallin Citation2023).

Regarding the outcomes for academics involved in assessment co-design, several studies found it enabled the development of teaching processes (n = 3) (Lorber, Rooney, and Van Der Enden Citation2019; Joseph et al. Citation2020; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023) and a greater understanding of student perspectives (n = 1) (Joseph et al. Citation2020). Notably, only one study reported on the negative outcomes of co-designing assessment, in that students had difficulty adapting to the co-design process (Curtin and Sarju Citation2021).

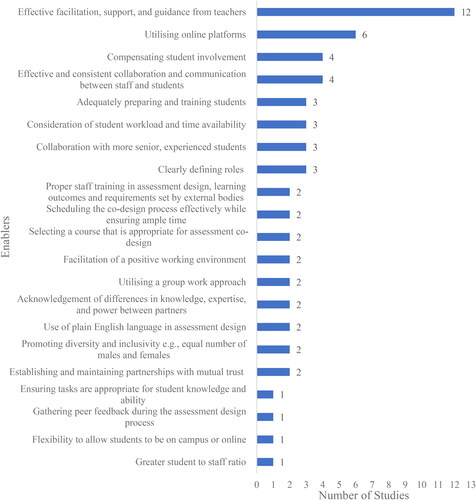

Enablers and barriers to effective assessment co-design

This review revealed several enablers that facilitate the process of effective assessment co-design ( & Supplementary Table 6). Effective facilitation, support and guidance from academic staff was identified as a key enabler in several studies in this review (n = 12) (Abdelmalak Citation2016; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019; Hussain et al. Citation2019; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Meinking and Hall Citation2020; Ruskin and Bilous Citation2020; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022; Chan and Chen Citation2023). Utilising online platforms, such as PeerWise, which allows students to create, answer, and comment on each other’s MCQs, made for a more seamless and efficient approach to collaboration (n = 6) (Joseph et al. Citation2020; Curtin and Sarju Citation2021; Keeling et al. Citation2021; Zwolski Citation2021; Doyle and Buckley Citation2022; Zhao and Zhao Citation2023). Additionally, effective collaboration and communication between staff and students facilitated a working relationship enhancing the co-design process (n = 4) (Biddix Citation2013; Bell et al. Citation2019; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022), while compensation of student involvement was also shown to be effective in assisting students engage with the co-design process (n = 4) (Peseta et al. Citation2016; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023). Furthermore, such collaboration allowed students and staff to build relationships based on mutual trust (n = 2) (Biddix Citation2013; Morton et al. Citation2021).

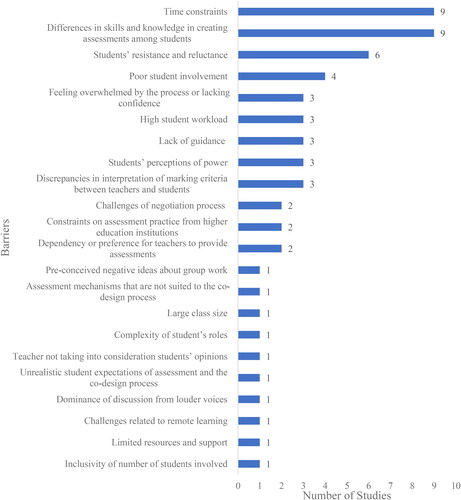

In contrast, this review identified several barriers to effective assessment co-design ( & Supplementary Table 7), which included time constraints affecting completion of co-design projects effectively (n = 10) (Biddix Citation2013; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Cook-Sather and Matthews Citation2021; Zwolski Citation2021; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023). The disparity due to students having different levels of skills and knowledge, especially related to the co-design process was also a barrier (n = 9) (Papinczak et al. Citation2011; Biddix Citation2013; Abdelmalak Citation2016; Kearney and University of Notre Dame Australia Citation2019; Quesada et al. Citation2019; Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Chadha et al. Citation2022; Johnston and Ryan Citation2022; Martel and Garcías Citation2022). Reluctance or resistance from students to engage fully with the co-design process was shown to significantly inhibit the success of this collaborative process (n = 6) (Lorente and Kirk Citation2013; Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018; Snelling et al. Citation2019; Abbot and Cook-Sather Citation2020; Wang and Lee Citation2021).

Discussion

This scoping review synthesised the literature to provide a comprehensive guide for implementation of co-design of assessments with students in tertiary education, particularly at the undergraduate level of study in academic disciplines outside of health science. The factors which constitute effective and ineffective assessment co-design and outcomes for student learning have also been summarised. The intensity of collaboration amongst staff and students across different settings and disciplines is variable with a diverse range of methodological approaches to assessment co-design. Three main processes of assessment co-design were identified: assessment rubric or marking criteria co-design; larger student group co-design; and smaller student group co-design. Key enablers of effective co-design were staff support and guidance and utilisation of online platforms, whereas barriers included time constraints and differences in skills in knowledge in creating assessments. Through working in partnership to co-design assessments, a wide range of benefits to students’ learning outcomes were identified, including increased autonomy, interest, motivation, engagement, which align with professional competencies and various graduate attributes.

Processes used in assessment co-design

Feedback and assessment are a major source of dissatisfaction within tertiary education because of the lack of transparency around assessment rubric and marking criteria (Bloxham and West Citation2004; Rust, O’Donovan, and Price Citation2005; Dawson Citation2017; Bearman and Ajjawi Citation2018). Hence, assessment criteria or rubric co-design was the most common type of co-design process used. The popularity of this process among reviewed studies, could be because it is easier and more achievable for staff and students to co-design a smaller component of the curriculum compared with working together to design and co-create a whole curriculum (Bovill et al. Citation2016). There is also flexibility for involving any number of students, from smaller to larger groups, in rubric or marking criteria co-design, particularly when this can be implemented as part of existing learning activities. However, this approach can still be time-consuming and may not be feasible to vary assessment requirements after a unit of study has commenced. This process may be better suited for cohorts who are undertaking the same classes for an entire year, for example with rubric co-design undertaken in the first semester and implemented within the second semester (Kilgour et al. Citation2020; Morton et al. Citation2021), or where the co-design is done retrospectively on assessments which have already been undertaken by a cohort. Furthermore, implementation of newly co-designed assessments within the same year may not always be possible. Particularly for assessment changes to conform with regulatory and governance procedures, it is essential to maintain ongoing communication with the designated academic authorities regarding any assessment co-design activities within a unit of study. This ensures alignment of these co-design activities with the course and unit learning outcomes. To enable this, planning must account for sufficient lead time to obtain necessary approvals and implement assessment variations in accordance with an institution’s established procedures. As institutional ethos shifts towards valuing student co-design and partnerships in learning and assessments, it is likely that some of these regulatory barriers could be overcome (Bovill et al. Citation2016). Further, novel co-designed assessment tools could provide a basis for continuous review and update of institutional policies and procedures.

Tertiary education contexts, particularly in undergraduate studies, typically have large student enrolments in courses and opportunity to benefit all students in the co-design process, meaning that large cohorts can be involved in design. Although assessment co-design in larger cohorts may pose a barrier due to the number of students to manage (Bovill et al. Citation2016), studies in this review included large whole cohorts of students in existing classes (e.g. total of 470 students) (Quesada et al. Citation2019). A common approach to larger scale co-design was having students design and submit MCQs or SAQs for use as study tools or to be integrated into the final examination. This approach was frequently employed in the science or health science disciplines (Baerheim and Meland Citation2003; Papinczak et al. Citation2011; Rivers et al. Citation2017; Warren-Forward and Kalthoff Citation2018), rather than arts disciplines, likely because these types of assessment are more commonly used to encourage students to more actively engage with large volumes of course content (Rivers et al. Citation2017). Particularly as blended or hybrid-models of learning models persist in the post-COVID-19 context, use of online platforms, such as PeerWise identified in this review, are useful for facilitating collaboration and scalability of assessment co-design, such as for classes of 100 students or more (Doyle and Buckley Citation2022) and have been found to be associated with improved student exam performance (Galloway and Burns Citation2015). Given the benefits of co-design, it has been emphasised that larger scale assessment co-design partnership opportunities provide greater accessibility and engagement of students to ensure inclusivity and equity (Bovill et al. Citation2016; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017; Bovill Citation2020). The limitation of large-scale assessment co-design processes may be less individualised support and collaboration provided by staff to students, but this can be overcome through co-creation workshops or focus group approaches to facilitate more effective staff-student partnerships among larger cohorts.

In contrast, smaller-scale co-design processes were also observed in this review, involving students, staff, and in some cases, former or senior students in more intensive partnerships, taking on more tasks and completing them within a shorter period (e.g. in workshops conducted over several days or weeks). This is consistent with another systematic review on students as partners in higher education, where co-design partnership activities were typically small-scale, extra-curricular, and focussed on teaching and learning enhancement (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). Among the reasons for electing smaller-scale co-design processes may be inherent reliance on establishing and maintaining relationships between staff and students and may be more easily managed in smaller numbers (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, students who volunteer for the smaller-scale activities may be highly motivated to make contributions to enhance their learning experience, thereby minimising the risk of poor student involvement (Abdelmalak Citation2016). However, selecting active or already very engaged students can pose the challenge of the whole cohort’s learning needs and preferences not being represented, but also the risk of co-design projects being perceived as only for privileged students (Bovill Citation2020). A recent study has also identified this inequity as a potential concern in co-designing with students (Newell and van Antwerpen Citation2024). To further ensure inclusive processes and equity of opportunity to participate in assessment co-design, this could involve paid opportunities to incentivise student involvement, consideration of students’ strengths, socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, and clear communication of the aims of co-design from teachers to encouraging participation (Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). Moreover, whole-class approaches to co-design may enhance inclusion (Bovill Citation2020), which may also offer an opportunity to capture disengaged students’ perspectives to affect change.

As tertiary education is increasingly internationalised, it is essential for assessment co-design practices to account for inclusivity and cultural and linguistic diversity. This is particularly relevant as linguistically diverse students have been found to have poorer educational outcomes due to inadequate understanding of assessments or assessment practices being unsuited to those students (Kaur, Noman, and Nordin Citation2017). Therefore, assessment co-design to increase accessibility and equity in achievements is necessary. Some considerations should be made when considering student diversity. For example, students from Asian backgrounds tend to be more familiar with didactic learning style because Asian education systems usually adopt passive learning approach (Tiew Citation2010). Based on the studies in this scoping review, it was found that assessment co-design processes, such as semi-structured interviews, focus groups, think aloud protocols, which require students to share their perspective or speak up, could lead them to feel stressed, or there may be less willingness to engage, participate or volunteer for these activities (Tiew Citation2010; Wang and Lee Citation2021). Intentional recruitment of international students into alternate co-design activity processes such as rubric or assessment criteria design may be more ideal and allow a balanced perspective to be captured from these students.

Student outcomes and barriers & enablers of effective assessment co-design

This paper supports the ongoing integration of assessment co-design in tertiary education settings due to the well documented student benefits, including increased student engagement and improved learning outcomes (Matthews and Cook-Sather Citation2021). Based on the definition of assessment literacy by Smith et al. (Citation2013), this review found that assessment co-design improved students’ understanding of the assessment and the rules surrounding assessment as well as building students’ foundational assessment skills and capabilities for learning. However, limited studies in this review reported on students’ ability to use the assessment guidelines to produce work of a predictable standard, with only one finding that marking rubrics were used to proactively guide assessment completion, rather than to reactively understand feedback (Joseph et al. Citation2020). Enhancing assessment literacy through providing clear learning goals and standards promotes student understanding of assessments, their engagement with tasks, and autonomy and is associated with student achievement in higher education (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Schneider and Preckel Citation2017; Zhu and Evans Citation2024). Assessment co-design presents an opportunity to shift traditional power dynamics that are deeply rooted in higher education (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). Thereby students are provided with more autonomy, sense of control and ownership over their learning which can increase engagement, interest, motivation, and involvement in the co-design process and personalising assessments based on their interests, needs, and learning styles.

Effective facilitation, support, and guidance from academic staff were common enablers of assessment co-design found in this review. A recent systematic review of empirical studies exploring student-partnership in higher education assessments conducted by Chan and Chen (Citation2023) also identified staff support as a crucial component of assessment partnership. Partnerships are a reciprocal process and thereby rely on interactions and contributions from both staff and student parties (Cook-Sather Citation2015). Hence, relationships built upon mutual trust were highly valued among staff and students in this review to help build a partnered learning community. Failure to do so was often seen to negatively impact on students’ ability and motivation to participate, leading to complaints of poor instruction, lack of training or facilitation.

The shift to a more democratic classroom facilitated by partnership can also face various challenges. The most common barriers include time constraints; student resistance and reluctance to engage in partnerships; and differences in skills and knowledge in creating assessments, which is consistent with previous literature (Bovill, Felten, and Cook-Sather Citation2014; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). Many co-design projects were conducted within a limited timeframe or were poorly timed during the semester due to certain co-design tasks being lengthier and more intensive than anticipated. Thus, it is vital to time co-design activities appropriately to maximise student engagement and minimise workload pressures.

Reluctance by students to engage in co-design could also be attributed to the disparity in power between students and staff in collaborative efforts (Higgins et al. Citation2019), whereby students are resistant to accept their empowered position (Seale et al. Citation2015) or staff are unwilling to relinquish their position of power (Matthews et al. Citation2018). Bovill et al. (Citation2016) has also observed the barriers to shared power in partnerships and commented that the traditional customs and structures of higher education make it challenging for students and staff to adopt new roles and engage in partnerships. However, making students aware of the benefits of co-designing assessments and staff providing support to students during the process could reduce students’ anxiety and resistance and increase engagement (Bovill et al. Citation2016). It is also important to acknowledge that resistance among staff can be present particularly in disciplines, such as the health sciences, where because of professional accreditation, students must achieve prescribed professional competency standards and specific program outcomes. However, this can be overcome by allowing for flexibility in the co-design of learning and assessment activities that enable students to still achieve the required standards (Bovill et al. Citation2016).

Assessment co-design with health science students

Studies in non-health science disciplines demonstrated positive outcomes on students’ learning that are relevant for health science disciplines due to the nature of healthcare practice. There is an opportunity for academic researchers within health science disciplines, such as Nutrition and Dietetics, to implement and contribute to the evidence-base for assessment co-design. One such example is a case study from RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, where nutrition students were given a choice about their assessments tailored to their personal interests, such as designing educational resources using communication platforms and skillsets the students want to develop and having input in peer-review assessments. The overall impact had positive results across student satisfaction, grades and academic integrity (Danaher Citation2023).

Health science graduates must meet a specific set of graduate attributes and competencies to be eligible for their qualification and professional membership. Through engaging in co-design, students can also develop skills in collaboration, leadership, teamwork, evaluative judgement, critical thinking, empathy, tolerance, and respect for others, which hold importance for working in health-related fields. In addition, as educational pedagogy has evolved, there is shift away from immediate learning outcomes and results towards enhancing the long-term capability of students and graduates with the ability to sustain effective learning – a requirement for accredited health science graduates beyond their tertiary education (Boud and Soler Citation2016). This scoping review found that the development of evaluative judgement and critical thinking skills, an enhanced ability to reflect on one’s own work, and greater self-awareness were key outcomes from participating in the co-design assessment tasks, all of which are foundational skills that facilitate ongoing professional development after graduation.

Future directions

It is evident that there is an increasing interest in research surrounding co-designing assessments, with over half of the studies captured in this review being published within the last five-year period (2019–2023). However, future research should describe the assessment co-design methodology and processes in greater detail, even in relation to the specific approaches relevant to a certain discipline, to help other university educators adopt some of the innovative practices presented within the literature. Evaluating the impact of assessment co-design, such as in a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial design of disciplines across different teaching semesters may also be beneficial as currently observational studies or case studies are the primary study design.

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI), has shifted the educational and assessment landscape in tertiary education, posing threats to academic integrity particularly for traditional assessments (Lodge et al. Citation2023). However, AI also offers opportunities for assessment reform, including advocating for authentic assessments that build professional competencies and engage students in partnerships with teachers for assessment design. Therefore, assessment co-design processes that account for and train students in authentically engaging with AI tools would be relevant (Lodge et al. Citation2023). For example, online platforms (e.g. Microsoft Teams) enhanced with AI tools, could facilitate collaborative rubric design at a whole-of-cohort level and summarise input from students and staff. AI could help students generate varied assessment responses for study and reflection, and coupled with teacher feedback, improve their assessment literacy. Students could also use AI to generate assessment responses across a range of grades for study and critical reflection purposes, which then coupled with feedback from teachers could enhance their assessment literacy. Additionally, AI could review co-designed assessments for bias, promoting inclusivity and fairness across diverse student backgrounds and learning styles.

With the majority of the reviewed studies conducted in undergraduate cohorts, future studies should examine assessment co-design processes with graduate students. Graduate students may have differing preferences towards the types of assessment co-design processes used, particularly as they often have greater academic experience, including better understanding of and familiarity with assessments (Bovill Citation2014; Wilson et al. Citation2014), greater maturity and life experience (Wilson et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, as they may have more motivational engagement and critical thinking, for example in online learning contexts (Artino and Stephens Citation2009), using online platforms could be an enabler to better engage with graduate students in assessment co-design compared to undergraduate students, where student-teacher relationships are a key enabler (Mayhew et al. Citation2016; Newell and van Antwerpen Citation2024).

Cross-national studies across disciplines, particularly health disciplines would also be necessary to investigate the impact of assessment co-design similarities, differences, trends between countries, to gain insights into global phenomena, cultural differences and influence international educational practices. International education is a prominent export industry and contributor to the economy in Western Countries, such as USA, UK, and Australia (Bound et al. Citation2021; Cannings, Halterbeck, and Conlon Citation2023; Hong, Lingard, and Hardy Citation2023). Therefore, a focus on assessment co-design with international students to enhance their educational experience and engagement with assessment and learning, as well as to reduce the failure rates for their studies is essential (Norton Citation2019).

Strengths and limitations

One of the key strengths of this scoping review is a co-design approach was undertaken between health science students and teachers/academics to complete this review. Moreover, the approach of this scoping review identified a wide range of relevant studies, providing a comprehensive overview of the application of assessment co-design in tertiary education, the types of activities, student impacts and knowledge gaps and priorities for future research. Following robust guidelines and frameworks for scoping reviews (Tricco et al. Citation2018; Aromataris and Munn Citation2020) and conducting thorough searches across seven databases ensured a comprehensive literature overview. By iteratively broadening the selection criteria, the review included studies across all tertiary disciplines, specifically identifying gaps in health sciences. This would otherwise have been missed because titles, abstracts and keywords were not always explicit about the disciplines included. Furthermore, by understanding how assessment co-design is implemented across a variety of disciplinary contexts, the findings of this review also has identified the gap in the literature highlighting the need for more research/studies in health sciences. However, the paucity of studies directly addressing assessment co-design in health sciences limits the generalisability of the findings.

Additionally, this scoping review was limited to English-language studies, excluding potentially relevant non-English research. Further, grey literature was not included for the search which could have provided greater representation of diverse populations from unpublished resources which further limits the generalisability of the findings. While scoping reviews provide a broad overview of a topic, future systematic reviews may allow synthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of specific assessment co-design methods on student and staff outcomes.

Conclusion

Co-designing assessments is an emerging and increasingly adopted practice within tertiary education and encompasses a range of methods and pedagogies. Overall, the findings from this study indicate that including students in the design of assessment tasks in tertiary education is feasible and can be a highly valuable learning experience, improving learning outcomes during students’ studies and equipping them with the skillset to be lifelong learners and valued professionals. However, research into assessment co-design with international and graduate students, as well as in the field of health science are sparse. This warrants action to bridge this gap in the research literature to ensure greater inclusion and equity across a range of tertiary education contexts. As the studies in the review lacked clarity of assessment co-design processes, future studies should detail the methods to allow tertiary educators to replicate and implement assessment co-design. Academics and students should also be equipped with training and knowledge for greater engagement and successful implementation of assessment co-design through strong staff-student partnerships.

caeh_a_2376648_sm3681.docx

Download MS Word (323 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbot, S., and A. Cook-Sather. 2020. “The Productive Potential of Pedagogical Disagreements in Classroom-Focused Student-Staff Partnerships.” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (7): 1396–1409. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1735315.

- Abdelmalak, M. M. M. 2016. “Faculty-Student Partnerships in Assessment.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 28 (2): 193–203.

- Aidan, A. J. 2020. “Students’ co-Ownership of Summative Assessment Marking Criteria towards a More Democratic Assessment in Higher Education.” In Transforming Curriculum Through Teacher-Learner Partnerships, 199–223. Hersey PA: IGI Global.

- Andrews, M., R. Brown, and L. Mesher. 2018. “Engaging Students with Assessment and Feedback: Improving Assessment for Learning with Students as Partners.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 11 (1): 32–46.

- Aromataris, E., and Z. Munn. 2020. "JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis." JBI. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Artino, A. R., and J. M. Stephens. 2009. “Academic Motivation and Self-Regulation: A Comparative Analysis of Undergraduate and Graduate Students Learning Online.” Internet and Higher Education 12 (3–4): 146–151. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.02.001.

- Baerheim, A., and E. Meland. 2003. “Medical Students Proposing Questions for Their Own Written Final Examination: Evaluation of an Educational Project.” Medical Education 37 (8): 734–738. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01578.x.

- Bearman, M., and R. Ajjawi. 2018. “From “Seeing Through” to “Seeing With”: Assessment Criteria and the Myths of Transparency.” Frontiers in Education 3: 1–8. doi:10.3389/feduc.2018.00096.

- Bell, A., S. Potter, L.-A. Morris, M. Strbac, A. Grundy, and M. Z. Yawary. 2019. “Evaluating the Process and Product of a Student-Staff Partnership for Curriculum Redesign in Film Studies.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 56 (6): 740–750. doi:10.1080/14703297.2019.1588768.

- Biddix, J. P. 2013. “From Classroom to Practice: A Partnership Approach to Assessment.” New Directions for Student Services 2013 (142): 35–47. doi:10.1002/ss.20047.

- Blackie, M. A. L., J. M. Case, and J. Jawitz. 2010. “Student-Centredness: The Link between Transforming Students and Transforming Ourselves.” Teaching in Higher Education 15 (6): 637–646. doi:10.1080/13562517.2010.491910.

- Blair, A., and S. McGinty. 2013. “Feedback-Dialogues: Exploring the Student Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (4): 466–476. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.649244.

- Blau, I., and T. Shamir-Inbal. 2018. “Digital Technologies for Promoting “Student Voice” and Co-Creating Learning Experience in an Academic Course.” Instructional Science 46 (2): 315–336. doi:10.1007/s11251-017-9436-y.

- Bloxham, S., and A. West. 2004. “Understanding the Rules of the Game: Marking Peer Assessment as a Medium for Developing Students’ Conceptions of Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 29 (6): 721–733. doi:10.1080/0260293042000227254.

- Boud, D., and R. Soler. 2016. “Sustainable Assessment Revisited.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (3): 400–413. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- Bound, J., B. Braga, G. Khanna, and S. Turner. 2021. “The Globalization of Postsecondary Education: The Role of International Students in the US Higher Education System.” Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 35 (1): 163–184. doi:10.1257/jep.35.1.163.

- Bovill, C. 2014. “An Investigation of Co-Created Curricula within Higher Education in the UK, Ireland and the USA.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 51 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1080/14703297.2013.770264.

- Bovill, C. 2020. “Co-Creation in Learning and Teaching: The Case for a Whole-Class Approach in Higher Education.” Higher Education 79 (6): 1023–1037. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w.

- Bovill, C., A. Cook-Sather, P. Felten, L. Millard, and N. Moore-Cherry. 2016. “Addressing Potential Challenges in Co-Creating Learning and Teaching: Overcoming Resistance, Navigating Institutional Norms and Ensuring Inclusivity in Student–Staff Partnerships.” Higher Education 71 (2): 195–208. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4.

- Bovill, C., P. Felten, and A. Cook-Sather. 2014. Engaging Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching (2): Practical Guidance for Academic Staff and Academic Developers.

- Brown, R., and G. Murti. 2003. “Student Partners in Instruction: Third Level Student Participation in Advanced Business Courses.” Journal of Education for Business 79 (2): 85–89. doi:10.1080/08832320309599094.

- Cannings, J., M. Halterbeck, and G. Conlon. 2023. "The Benefits and Costs of International Higher Education Students to the UK Economy." London Economics. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Full-Report-Benefits-and-costs-of-international-students.pdf.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Cash, C. B., J. Letargo, S. P. Graether, and S. R. Jacobs. 2017. “An Analysis of the Perceptions and Resources of Large University Classes.” CBE Life Sciences Education 16 (2): Ar33. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-01-0004.

- Chadha, D., P. K. Inguva, L. Bui Le, and A. Kogelbauer. 2022. “How Far Do we Go? Involving Students as Partners for Redesigning Teaching.” Educational Action Research 31 (4): 620–632. doi:10.1080/09650792.2022.2058974.

- Chamunyonga, C., J. Burbery, P. Caldwell, P. Rutledge, and C. Hargrave. 2018. “Radiation Therapy Students as Partners in the Development of Alternative Approaches to Assessing Treatment Planning Skills.” Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 49 (3): 309–315. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2018.04.023.

- Chan, C. K. Y., and S. W. Chen. 2023. “Student Partnership in Assessment in Higher Education: A Systematic Review.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (8): 1402–1414. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2224948.

- Chase, M. K. 2020. “Student Voice in STEM Classroom Assessment Practice: A Pilot Intervention.” Research & Practice in Assessment 15 (2): 1–14.

- Colson, N., M.-A. Shuker, and L. Maddock. 2022. “Switching on the Creativity Gene: A Co-Creation Assessment Initiative in a Large First Year Genetics Course.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (8): 1149–1166. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.2011133.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2014. “Student-Faculty Partnership in Explorations of Pedagogical Practice: A Threshold Concept in Academic Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 19 (3): 186–198. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2013.805694.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2015. “Dialogue across Differences of Position, Perspective, and Identity: Reflective Practice in/on a Student-Faculty Pedagogical Partnership Program.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 117 (2): 1–42. doi:10.1177/016146811511700204.

- Cook-Sather, A., C. Bovill, and P. Felten. 2014. Engaging Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cook-Sather, A., and K. E. Matthews. 2021. “Pedagogical Partnership: Engaging with Students as co-Creators of Curriculum, Assessment and Knowledge.” In University Teaching in Focus: A Learning-Centred Approach, 243–259. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Cosker, E., V. Favier, P. Gallet, F. Raphael, E. Moussier, L. Tyvaert, M. Braun, and E. Feigerlova. 2021. “Tutor-Student Partnership in Practice OSCE to Enhance Medical Education.” Medical Science Educator 31 (6): 1803–1812. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01421-9.

- Curtin, A. L., and J. P. Sarju. 2021. “Students as Partners: Co-Creation of Online Learning to Deliver High Quality, Personalized Content.” In ACS Symposium Series, edited by E. Pearsall, Rock Hill S. C., York Technical College, K. Mock, Toledo O. H. University of Toledo, M. Morgan, Salt Lake City U. T. Western Governors University, B. A. Tucker and Birmingham A. L. University of Alabama at Birmingham, 135–163. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

- Danaher, J. 2023. "Case Study: Encouraging Active Learning by Co-Designing Authentic Assessments with Students." RMIT University. https://www.rmit.edu.au/news/next-in-teaching/2023/jul/active-learning-co-designed-assessment.

- Dawson, P. 2017. “Assessment Rubrics: Towards Clearer and More Replicable Design, Research and Practice.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (3): 347–360. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1111294.

- Deeley, S. J., and C. Bovill. 2017. “Staff Student Partnership in Assessment: Enhancing Assessment Literacy through Democratic Practices.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (3): 463–477. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1126551.

- Doyle, E., and P. Buckley. 2022. “The Impact of co-Creation: An Analysis of the Effectiveness of Student Authored Multiple Choice Questions on Achievement of Learning Outcomes.” Interactive Learning Environments 30 (9): 1726–1735. doi:10.1080/10494820.2020.1777166.

- Doyle, E., P. Buckley, and J. Whelan. 2019. “Assessment co-Creation: An Exploratory Analysis of Opportunities and Challenges Based on Student and Instructor Perspectives.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (6): 739–754. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1498077.

- Galloway, K. W., and S. Burns. 2015. “Doing It for Themselves: Students Creating a High Quality Peer-Learning Environment.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 16 (1): 82–92. doi:10.1039/C4RP00209A.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Engagement through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education.

- Higgins, D., A. Dennis, A. Stoddard, A. G. Maier, and S. Howitt. 2019. “Power to Empower’: Conceptions of Teaching and Learning in a Pedagogical co-Design Partnership.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (6): 1154–1167. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1621270.

- Hong, M., B. Lingard, and I. Hardy. 2023. “Australian Policy on International Students: Pivoting towards Discourses of Diversity?” Australian Educational Researcher 50 (3): 881–902. doi:10.1007/s13384-022-00532-5.

- Hussain, S., K. A. A. Gamage, W. Ahmad, and M. A. Imran. 2019. “Assessment and Feedback for Large Classes in Transnational Engineering Education: Student–Staff Partnership-Based Innovative Approach.” Education Sciences 9 (3): 221. doi:10.3390/educsci9030221.

- Hutchings, P., N. A. Jankowski, and G. Baker. 2018. “Fertile Ground: The Movement to Build More Effective Assignments.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 50 (6): 13–19. doi:10.1080/00091383.2018.1540816.

- Johnston, J., and B. Ryan. 2022. “From Students-as-Partners Theory to Students-as-Partners Practice: Reflecting on Staff-Student Collaborative Partnership in an Academic Development Context.” AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education 14 (1): 1–27.

- Jönsson, A., and F. Prins. 2019. “Editorial: Transparency in Assessment—Exploring the Influence of Explicit Assessment Criteria.” Frontiers in Education 3 (January): 2018–2020. doi:10.3389/feduc.2018.00119.

- Joseph, S., C. Rickett, M. Northcote, and B. J. Christian. 2020. “Who Are You to Judge my Writing?’: Student Collaboration in the co-Construction of Assessment Rubrics.” New Writing 17 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1080/14790726.2019.1566368.

- Kaur, A., and M. Noman, University Utara Malaysia. 2020. “Investigating Students’ Experiences of Students as Partners (SaP) for Basic Need Fulfilment: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 17 (1): 108–121. doi:10.53761/1.17.1.8.

- Kaur, A., M. Noman, and H. Nordin. 2017. “Inclusive Assessment for Linguistically Diverse Learners in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (5): 756–771. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1187250.

- Kearney, S. P, University of Notre Dame Australia. 2019. “Transforming the First-Year Experience through Self and Peer Assessment.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 16 (5): 20–35. doi:10.53761/1.16.5.3.

- Keeling, K., Z. Phalen, and M. J. Rifenburg, University of North Georgia, United States. 2021. “Redesigning a Sustainable English Capstone Course through a Virtual Student-Faculty Partnership.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 18 (7): 244–257. doi:10.53761/1.18.7.15.

- Kilgour, P., M. Northcote, A. Williams, and A. Kilgour. 2020. “A Plan for the co-Construction and Collaborative Use of Rubrics for Student Learning.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (1): 140–153. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1614523.

- Leslie, L. J., and P. C. Gorman. 2017. “Collaborative Design of Assessment Criteria to Improve Undergraduate Student Engagement and Performance.” European Journal of Engineering Education 42 (3): 286–301. doi:10.1080/03043797.2016.1158791.

- Lodge, J. M., S. Howard, M. Bearman, and P. Dawson. 2023. "Assessment Reform for the Age of Artificial Intelligence." Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-09/assessment-reform-age-artificial-intelligence-discussion-paper.pdf.

- Lorber, P., S. Rooney, and M. Van Der Enden. 2019. “Making Assessment Accessible: A Student–Staff Partnership Perspective.” Higher Education Pedagogies 4 (1): 488–502. doi:10.1080/23752696.2019.1695524.

- Lorente, E., and D. Kirk. 2013. “Alternative Democratic Assessment in PETE: An Action-Research Study Exploring Risks, Challenges and Solutions.” Sport, Education and Society 18 (1): 77–96. doi:10.1080/13573322.2012.713859.

- Martel, J. S. S., and A. P. Garcías. 2022. “Students’ Agency and Self-Regulated Skills through the Lenses of Assessment Co-Creation in Post-COVID-19 Online and Blended Settings: A Multi-Case Study.” Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2022 (1): 1–17. doi:10.5334/jime.746.

- Matthews, K. E., and A. Cook-Sather. 2021. “Engaging Students as Partners in Assessment and Enhancement Processes.” In Assessing and Enhancing Student Experience in Higher Education, 107–124. Switzerland: Springer.

- Matthews, K. E., A. Dwyer, L. Hine, and J. Turner. 2018. “Conceptions of Students as Partners.” Higher Education 76 (6): 957–971. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y.

- Mayhew, M. J., A. B. Rockenbach, N. A. Bowman, T. A. Seifert, and G. C. Wolniak. 2016. How College Affects Students, 21st Century Evidence That Higher Education Works. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Meer, N., and A. Chapman. 2014. “Co-Creation of Marking Criteria: Students as Partners in the Assessment Process.” Business and Management Education in HE 1–15. doi:10.11120/bmhe.2014.00008.

- Meijer, H., R. Hoekstra, J. Brouwer, and J.-W. Strijbos. 2020. “Unfolding Collaborative Learning Assessment Literacy: A Reflection on Current Assessment Methods in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (8): 1222–1240. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1729696.

- Meinking, K. A., and E. E. Hall. 2020. “Co-Creation in the Classroom: Challenge, Community, and Collaboration.” College Teaching 68 (4): 189–198. doi:10.1080/87567555.2020.1786349.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., S. Dvorakova, K. Matthews, S. Abbot, B. Cheng, P. Felten, K. Knorr, E. Marquis, R. Shammas, and K. Swaim. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of Students as Partners in Higher Education.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (1): 1–23. doi:10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119.

- Morton, J. K., M. Northcote, P. Kilgour, and W. A. Jackson. 2021. “Sharing the Construction of Assessment Rubrics with Students: A Model for Collaborative Rubric Construction.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 18 (4): 1–13. doi:10.53761/1.18.4.9.

- Newell, S., and N. van Antwerpen. 2024. “Can we Not Do Group Stuff?”: Student Insights on Implementing co-Creation in Online Intensive Programs.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 21 (2): 1–23. doi:10.53761/1.21.2.05.

- Norton, A. 2019. "Do More Foreign Students Fail than Domestic Students?" University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190509074956685.

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 372: N 71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Papinczak, T., A. Babri, R. Peterson, V. Kippers, and D. Wilkinson. 2011. “Students Generating Questions for Their Own Written Examinations.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice 16 (5): 703–710. doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9196-9.

- Peseta, T., A. Bell, A. Clifford, A. English, J. Janarthana, C. Jones, M. Teal, and J. Zhang. 2016. “Students as Ambassadors and Researchers of Assessment Renewal: Puzzling over the Practices of University and Academic Life.” International Journal for Academic Development 21 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2015.1115406.

- Quesada, V., M. Á. Gómez Ruiz, M. B. Gallego Noche, and J. Cubero-Ibáñez. 2019. “Should I Use co-Assessment in Higher Education? Pros and Cons from Teachers and Students’ Perspectives.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (7): 987–1002. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1531970.

- Rivers, J., A. Smith, D. Higgins, R. Mills, A. Maier, and S. Howitt. 2017. “Asking and Answering Questions: Partners, Peer Learning, and Participation.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (1): 114–123. doi:10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3072.

- Ruskin, J., and R. H. Bilous. 2020. “A Tripartite Framework for Extending University-Student co-Creation to Include Workplace Partners in the Work-Integrated Learning Context.” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (4): 806–820. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1693519.

- Rust, C., B. O’Donovan, and M. Price. 2005. “A Social Constructivist Assessment Process Model: How the Research Literature Shows us This Could Be Best Practice.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1080/02602930500063819.

- Schneider, M., and F. Preckel. 2017. “Variables Associated With Achievement in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses.” Psychological Bulletin 143 (6): 565–600. doi:10.1037/bul0000098.

- Seale, J., S. Gibson, J. Haynes, and A. Potter. 2015. “Power and Resistance: Reflections on the Rhetoric and Reality of Using Participatory Methods to Promote Student Voice and Engagement in Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (4): 534–552. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2014.938264.

- Smith, S., K. Akhyani, D. Axson, A. Arnautu, and I. Stanimirova. 2023. "The Partnership Co-Creation Process: Conditions for Success?".

- Smith, C. D., K. Worsfold, L. Davies, R. Fisher, and R. McPhail. 2013. “Assessment Literacy and Student Learning: The Case for Explicitly Developing Students ‘Assessment Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (1): 44–60. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.598636.

- Snelling, C., B. Loveys, S. Karanicolas, N. Schofield, W. Carlson-Jones, J. Weissgerber, R. Edmonds, and J. Ngu. 2019. “Partnership through co-Creation: Lessons Learnt at the University of Adelaide.” International Journal for Students as Partners 3 (2): 62–77. doi:10.15173/ijsap.v3i2.3799.

- Stephenson, A. 2006. “Troubling Teaching.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 31 (1): 51–56. doi:10.1177/183693910603100108.

- Tiew, F. 2010. “Business Students’ Views of Peer Assessment on Class Participation.” International Education Studies 3 (3): 126–131. doi:10.5539/ies.v3n3p126.

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. doi:10.7326/m18-0850.

- Wallin, P. 2023. “Humanisation of Higher Education: Re-Imagining the University Together with Students.” Learning and Teaching 16 (2): 55–74. doi:10.3167/latiss.2023.160204.

- Wang, L., and I. Lee. 2021. “L2 Learners’ Agentic Engagement in an Assessment as Learning-Focused Writing Classroom.” Assessing Writing 50: 100571. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2021.100571.

- Warren-Forward, H. M., and O. Kalthoff. 2018. “Development and Evaluation of a Deep Knowledge and Skills Based Assignment: Using MRI Safety as an Example.” Radiography (London, England: 1995) 24 (4): 376–382. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2018.05.011.

- Wilson, W. J., A. Bennison, W. Arnott, C. Hughes, R. Isles, and J. Strong. 2014. “Perceptions of Assessment among Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students of Four Health Science Disciplines.” Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice 12 (2): 11. doi:10.46743/1540-580X/2014.1485.

- Zhao, H., and B. Zhao. 2023. “Co-Constructing the Assessment Criteria for EFL Writing by Instructors and Students: A Participative Approach to Constructively Aligning the CEFR, Curricula, Teaching and Learning.” Language Teaching Research 27 (3): 765–793. doi:10.1177/1362168820948458.

- Zhao, K., J. Zhou, and P. Dawson. 2021. “Using Student-Instructor co-Constructed Rubrics in Signature Assessment for Business Students: Benefits and Challenges.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 28 (2): 170–190. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2021.1908225.

- Zhu, X., and C. Evans. 2024. “Enhancing the Development and Understanding of Assessment Literacy in Higher Education.” European Journal of Higher Education 14 (1): 80–100. doi:10.1080/21568235.2022.2118149.

- Zwolski, K. 2021. “Assessing International Relations in Undergraduate Education.” European Political Science 20 (2): 345–358. doi:10.1057/s41304-020-00255-0.