Abstract

This article discusses the African cohort’s contribution to the “re-inventing democracy in the digital era” project, funded by a UN Democracy Fund. The project involved almost 100 youth from five regions of the globe in deliberating upon the future of democracy, using a methodology called structured dialogical design. We explain the utility of this methodology for aiding processes of deliberative democracy. We focus on the Africa cohort’s (collective) identification of current challenges and envisioning of corrective actions for democracy in the digital age; we justify our choice and point out that many of their suggestions apply to other regions too.

Introduction

As emphasized by Laszlo (Citation1997), “the future is not what will happen but what we make happen”. The future is “there to be created” (1997, p. 31). This implies for him that our thinking (as a collective “we”) needs to be “intensely practical” and should be geared toward attempting to create a future that can be “different” (1997, p. 31). This sentiment is likewise expressed by many transformative systemic thinkers (see, for example, Ackoff & Pourdehnad, Citation2001; Banathy, Citation1991; Cardenas & Moreno, Citation2004; Flood, Citation2001; Gregory et al., Citation2020; Hsu & Nourbakhsh, Citation2020; Ison, Citation2010; McIntyre-Mills, Citation2014, Citation2017; Midgley, Citation1996, Citation2001, Citation2020; Mugadza, Citation2015; Romm, Citation1996, Citation2015; Ulrich, Citation1996, Citation2001). In this article, we focus on the use of a specific methodology that has been devised and developed with the intention of enabling a process for people to together think “practically” as well as systemically while envisaging new futures. The methodology originated in the early 70 s in what was called Interactive Management, as a process supported by a mathematical algorithm embedded in software developed to aid learning in groups toward collective decision-making, as laid out in Christakis (Citation1973); Warfield (Citation1973, Citation1994); and Warfield and Cárdenas (Citation1994). Since then it has been used and refined in many contexts across the globe, with various elaborations of its philosophical underpinning as well as elaborations of the software (e.g., Cardenas, Janes, & Otalora, Citation1999; Christakis & Bausch, Citation2006; Cisneros & Hisijara, Citation2013; Flanagan & Christakis, Citation2010; Jones, Citation2008; Laouris, Citation2012; Laouris & Laouri, Citation2008; Laouris, Citation2017; Laouris & Michaelides, Citation2018; Romm, Citation2010).

The aim of the methodology, which in 2002 became registered by the Institute for twenty-first Century Agoras under the name Structured Dialogical Design (SDD) is, as Christakis & Bausch summarize, to “harness collective wisdom” (2006). Such wisdom is not geared to extrapolating from the present to the future (by noting trends and considering how they might develop) but to what Laouris (Citation2017) name re-inventing a new imagined future. The SDD process encourages citizens from all walks of life to envision new, ideal futures, subsequently to identify the root obstacles and challenges preventing them from reaching those futures, and finally exploring options in order to discover the most effective leverage points for their actions to create such futures. The process can also be applied with experts of a particular domain as participants. For example, the European Commission designed calls for proposals for funding of almost seven billion euros on future accessible and assistive products and services using the collective intelligence of a few hundred experts who applied SDD to identify the obstacles that prevent the production of practical applications, despite the availability of powerful broadband technologies (Laouris, & Michaelides, Citation2007) and to propose mechanisms that would ensure effective technology transfer (Roe et al., Citation2011).

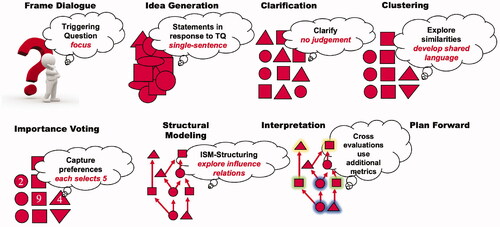

Briefly put, and detailed further below in our article, the SDD methodology sets up a specific way of developing a learning encounter between concerned stakeholders—typically citizens in societal applications—based on their deliberating (via the SDD process) around well-framed Triggering Questions (TQs), with each TQ being handled in turn through a number of identically designed structured dialogic processes. A typical application unfolds over three SDDs as explained above with the first developing a shared vision, the second identifying the root obstacles, and the third designing a roadmap with actions. The participants are encouraged through the process design to listen actively to one another’s concerns and ideas in relation to the TQ and to seek clarifications of meaning and perspective without being allowed at the early stages to express any form of judgment. This serves as precursor to cluster together ideas that seem to have affinity (as decided by participants, also in engagement with one another’s considerations and highlighting of distinctions). The process facilitates the gradual emergence of shared language and understanding. Once they complete this stage, the participants each chooses five ideas which they deem most significant. Only ideas with two or more votes enter the next step of the process during which participants explore possible influence relations between pairs of ideas. Here the facilitator asks people to consider whether for example, making progress on addressing Challenge A, will make it significantly easier to address Challenge B, or whether making progress in implementing Action X makes it significantly easier to implement Action Y. The selection of factors for pairwise comparisons is facilitated via the use of the Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) algorithm (Warfield, Citation1973) embedded in specially designed software; in our case Cogniscope v.3 and IdeaPrism.Footnote1 The Cogniscope approach (Magliocca & Christakis, Citation2001) can be characterized as what Laszlo (Citation2003, p. 639) calls a “soft technology”’ in that the purpose of using it is to “augment creative and constructive processes of human interaction” as a process of learning at regional and global levels (Laszlo, Citation2003, p. 639). In the course of the article we explain how it was used to this effect, along many other tools, also in the “re-inventing democracy in the digital age” project.

The Cogniscope software facilitates the gradual development of an influence map (or influence tree), based on people’s collective deliberations around pair-wise comparisons between ideas. The resulting map is considered as offering a systemic (as opposed to a reductionist) analysis of the various ways in which the ideas are “influencing each other,” with the ideas located at the root of the tree as particularly influential (such that a change of them is crucial to reconfigure the system). In other words, statements that end up at the root of the map are the ones that exert maximum influence to those above. In the case where the influence map expresses the results of people’s deliberations around challenges to realizing some vision (based on participants deliberating around a TQ that ask people to consider how shortcomings can be improved), statements at the root are the key challenges; when the map is about actions (based on a TQ that encourages participants to deliberate around concrete actions), statements at the root are considered to be the deep drivers for change (Laouris, Citation2017, p. 27). That is, the processes of deliberation are undertaken around TQs which focus people’s attention on a critical systemic analysis of challenges observed in “the situation” (as detected via the collective systemic approach) and on actions that can and should be undertaken in the light of further systemically oriented dialogical deliberations, which point to “deep drivers for change”.

This SDD process can be considered as entailing what Smitsman et al., (Citation2020, p. 215) call forms of learning which are aimed at locating “the difference that makes a difference” (Smitsman et al., citing Bateson, 1972) in order to envisage and activate new futures. Smitsman et al. argue that now more than ever it is crucial to set up such forms of learning which encourage people to become more conscious of “the larger realities of life,” to become “responsive to future needs” (as understood through collective deliberations); and to become more “responsible for the impacts of their [and others’] past activities” (Citation2020, p. 215). Considering current crises with which we (as humanity) are faced, which specifically affect the youth of today and future generations, they suggest that “it is imperative that we get real and at the same time draw hope and strength from what is rising through the consciousness of youth mobilization around the world” (Citation2020, p. 215)

They argue that “never before has it been more urgent and critical to develop competencies that make us future-fit and future-creative for a world that works” (Citation2020, p. 215). They define a world that works as one in which we all can “thrive together” and also protect the wellbeing of the planet. According to them:

Many youths are looking for how they can join learning networks, communities, and movements that are capable of inspiring learning for conscious action in the collective caretaking of our integral wellbeing. (Citation2020, p. 217)

They suggest that “these learning networks are beginning to emerge as a new educational prototype” (Citation2020, p. 218). They point out that for Generation Z (the generation succeeding the Millennials, where the Millennials are considered as coming of age in the Information Age), “collective learning through learning networks is not something new”. And they suggest that youth are increasingly expecting that they are “part of the co-design of new educational prototypes,” with emphasis on the need for “integral thrivability” (Citation2020, p. 218). Smitsman et al. define such thrivability in terms of a sense of wellbeing on various levels, as follows:

Personal wellbeing, which implies individual “thrivability” (fulfilment of capabilities);

Communal wellbeing, where the emphasis is on the quality of our “human relationships with others”;

Societal wellbeing, where people become (more) conscious of a “collective sense of us as one humanity”. That is, the focus is centered on how we can “interact in thrivable ways as entire societies”’ (within and across national borders).

Ecosystemic wellbeing—where the focus “expands beyond the exclusively human sense of self to also embrace a sense of trans-species thrivability”. This includes planetary wellbeing,

Transgenerational wellbeing, which invites us to “empathize with the hopes, dreams, needs and expectations of our ancestors and of future generations not yet born”. (They note in this regard that in First Nations indigenous education programs of the Americas this is often referred to as 7th Generation Education (e.g., Jacobs, Citation2016).)

Cosmological wellbeing, which implies a sense of connectivity with “the cosmos” of which we are part.

Taking a cue for this article from Smitsman et al.’s account of the urgency of setting up more learning networks that are future-oriented (while ensuring the involvement of youth), we relate this to the re-invent democracy project funded by the UN democracy fund and organized through the Future Worlds Center (2016–2017). The project involved almost 100 youth from 50 countries from five different regions of the globe (namely Africa, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Latin America, Europe, and Australasia) in week-long face-to-face dialogues for each region, respectively, facilitated via the SDD process. (The participants also had to locate 10 shadow participants each, with whom they were in virtual contact, thus implying that about 1000 youth were potentially involved.) We have chosen in this article to concentrate on the African cohort, because concentrating on all the regions would render the article far too long.

In our justification for choosing this cohort for this article (while subsequent articles in this or other journals can concentrate on others), we appreciate Smitsman et al.’s point that in trying to forward “transgenerational wellbeing,” we can “empathize with the hopes … of our ancestors” as well as with hopes for future generations, as indeed is one of the principles endorsed by First Nations Indigenous education programs in the Americas (Smitsman et al., Citation2020, p. 218). We relate this idea not only to First Nations in the Americas, where ancestors in cultural histories are respected (and learning from their values is endorsed), but to transnational Indigenous perspectives, including the Indigenous perspectives hailing from Africa prior to colonization. It seems to us also that prospects for the realization of democracy in Africa are often considered as bleak in scholarly and other discourses; and we wish to overturn this “deficit” perspective via this article—which itself might influence how people regard, and act in relation to, African democracy. We hope via this article to turn around this vision by focusing on an asset-based approach, which considers assets and encourages possibilities for strengthening these. This is also considered important in what is called “appreciative inquiry” mode (e.g., Acosta & Douthwaite, Citation2005; Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Citation2003; Cram, Citation2010; Stratton-Berkessel, Citation2018). As mentioned earlier, the focus on inviting youth into the project is consistent with the remarks by Smitsman et al. on youth demanding and rightfully expecting to participate in defining how we learn to embark on new futures (Citation2020, p. 215).

It may also be worth noting that in examining the demographic constitution of youth globally, statistical projections from the United Nations in 2019 suggest that Africa has the most youth:

by 2020, the people of Niger would have a median age of 15.2, Mali 16.3, Chad 16.6, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola all 16.7, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 17.0, Burundi 17.3, Mozambique and Zambia both 17.6. (This means that more than half of their populations were born in the first two decades of the twenty-first century.) These are the world's youngest countries by median age (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generation_Z#Africa).

For these various reasons, this article is directed around the African cohort. Nevertheless, this is not to say that our focus on this cohort means that the article has no relevance for readers wishing to re-think democracy across the board. Skype interviews held in 2019 with many of the African participants who read/perused the re-invent democracy reports from the different regions indicate that they felt that although there were certain issues that seemed to pertain particularly to Africa (such as wars and civil strife), the deliberations of their cohort on prospects re-inventing democracy in the digital age, were also by and large relevant across the globe and vice versa.

The article is structured as follows: In the next section we follow up Smitsman et al.’s reference to certain Indigenous cultural values, as pointing to possibilities for people participating in (radically) reshaping our future toward an inclusive “thrivability”. We relate this observation to some comments on African Indigeneity and we point to implications for democracy. We note also that the emergence of democracy in ancient Greece need not be seen as a purely Greek phenomenon. In a further section we elaborate on challenges as well as potentials of deliberative democracy as an ideal-type, as distinct from “aggregative democracy” (as aggregation of people’s preferences and/or as a process of bargaining). We indicate implications for consensus-seeking in deliberative democracy and specifically in SDD. We move on to a section detailing how SDD was used in the case of the re-invent democracy project, with special attention to: how participants were invited/selected; the TQs around which the deliberations proceeded; and how the “generic” SDD was modified somewhat in the case of the re-inventing democracy project. This is followed by a “results” section, in which we draw the results of the various phases of the dialogues from the African cohort. This section includes some pointers to the kinds of actions which participants from this region whom we interviewed in October/November 2019 indicated they were engaged in (subsequent to their participation in the SDD dialogues).Footnote2 We comment on how the African “results” relate to global challenges and prospects for re-inventing democracy in the digital age. We also comment on some feedback received from a number of the African participants. In our penultimate section, we offer some commentary in relation to how SDD is equipped in principle and in practice to support large-scale societal intervention. Finally, we conclude the article.

Learning Networks Toward Thriving: Renewal and Strengthening of Certain Indigenous Cultural Values (e.g., Relationality and Harmony-Seeking) in Forward-Looking Fashion

In Smitsman et al.’s view, Indigenous cultural values (such as those of First Nations) are increasingly becoming recognized as needing to be revitalized and further developed, in order to transform currently over-materialist visions which have become globally prevalent and which threaten possibilities for a “world that works” (Citation2020, p. 215). Smitsman et al.’s mention of Native American Indigenous programs is consistent with the interest of La Donna Harris—founder of the organization called Americans for Indian Opportunity (AIO)—in using the SDD Cogniscope as developed, inter alia, by Christakis. She has used the SDD process to forge a way for Indigenous leaders transnationally to share visions of how the “intangibles of traditional core cultural values” can become infused into new visions for the future which respect Indigenous values that forward “wellbeing” and which can also be shared with others across the globe, as part of a dialogue on the construction of the future (cf. Christakis & Harris, Citation2004; Guerra, Citation2016; Harris & Wasilewski, Citation2004). In an interview with Benking (Citation2010) Christakis explains how LaDonna Harris has been using SDD:

La Donna Harris is a very distinguished Native American from the Comanche tribe, and she has been working for the last 35 years for Americans for Indian Opportunities (AIO). La Donna was a visionary because when we met 20 years ago, she wanted to adopt the structured dialogue approach for the native American tribes [in order to address problems of survival and sustainability] … . LaDonna recognized that the consensus building approach that I was using and the structured dialogue methodology was very similar to the traditional way of Native Americans of coming together and building consensus and making decisions on the basis of consensus. So she thought that our approach was the equivalent of the traditional way of decision making. We trained them to do that, they are doing that again and again all-over the world.

Benking comments in response to this statement of Christakis that the process here described is similar to a vision of “bottom-up democracy” that he notes Christakis has been attempting to forward in various arenas, with the focus on dialogically-oriented participation (http://www.europesworld.org/NewEnglish/Home_old/PartnerPosts/tabid/671/PostID/1128/language/en-US/Default.aspx)

The AIO’s call (led by Harris) for the possible strengthening of Indigenous values such as relationality, reciprocity, and respectful dialogue toward consensually-based addressal of problems, is also consistent with what many African scholars propound as a way to cater for democratic dialogue oriented toward the common good, which they see as nascent in pre-colonial Africa. For example, Adenkule states that “the elements and indices of democracy … were present in one form or another in precolonial Africa” (Citation2012, p. 18). According to him, “African cultures infused communal values into their political practices”. Like many other scholars, he sees such values as “present” in many ways (though not in perfect ways) in Indigenous African cultural traditions prior to colonization (cf. Ani, Citation2013; Chilisa, Citation2020; Chirawurah et al., Citation2019; Goduka, Citation2012; Matlosa, Citation2007; Matshidze, Citation2013; Ryser et al., Citation2017). (And like others, he argues that processes of colonization impinged negatively on such values.)

We make this point also because the birth of democracy is often in popular parlance considered to be in ancient (classical) Greece, which then became the inspiration for democracy in other parts of the globe. But according to Cobley, this historical account as crafted by historians “expunges the Egyptian, Semitic and African roots of the West’s history” (Citation2001, p. 38). Put differently, the historians portrayed a “purity” of the Western traditions which failed to recognize its hybridity from the start (Citation2001, p. 39). He cites Bernal’s Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization (1987) as detailing the manner in which European historians writing from the 18th century onwards, “edited out the non-White elements of the Western past”. Bernal argues that classical civilization has deep roots in Afroasiatic cultures, but that these influences have been systematically suppressed by historians (and hence in popular thinking). By choosing to discuss the results of this project based on the African cohort we do justice to the African roots of democracy.

Ancient Greek democracy—which we need not interpret as “purely” Greek, as pointed out by Bernal (Citation1987) and by Cobley (Citation2001)—embraced a commitment to democratic participation based on constructive dialogue between citizens. Of course, as underscored by Kakoulaki and Christakis (Citation2018, p. 431), as well as by many commentators, neither women nor slaves had the right to enter the agoras, where the male citizenry had the opportunity to take part in the deliberations leading to decisions about issues affecting their lives. Likewise, those participating in African councils in Africa were normally composed of mainly (if not solely) men, although some authors argue that women also often had the power to partake in public deliberations, through different channels than the council meetings (cf. Buswell & Corcoran-Nantes, Citation2018; Matshidze, Citation2013). Several African authors have argued that “the fundamental category ‘woman'- which is foundational to Western gender discourses- simply did not exist” (Amadiume, 1987), but it was rather colonialism, western religion and education that imposed the particular patriarchal systems (Oyewumi, Citation1997). But what is noteworthy in both the Greek and the African context, is that the political process was not premised on counting up people’s preferences as expressed via a vote in order to find a majority preference, or as pursuing a process of bargaining of diverse individual or group preferences. That is, voting was not seen, as Laouris puts it, as a “magical instrument that secures a fair and a democratic process” (Citation2012, p. 251). Laouris considers this (aggregative) conception as being “deeply rooted in the [current] western world” (Citation2012, p. 251), where the fundamentals of the ancient Greek word “democracy” seem to have become largely lost, except in scholarly articles and in certain isolated attempts to practice it, albeit in what we consider to be a not sufficiently systemic fashion (Citation2012, p. 251). This is why it is imperative to “re-invent” democracy by taking into account the ideal of deliberative democracy, as indeed implied in the ancient Greek conception, despite its flaws in not being sufficiently inclusive and of course not having the benefit of technology to aid people to address complex interrelated problems (far more complex than in the ancient Greek agoras). Any attempt to scale up the system, without taking into account the distinctive characteristics of the Athenian context (e.g., small population size), is, however, nothing but trivial.

Democracy and Deliberative Democracy

The Greek word for democracy (δημοκρατία) is made up of two parts, with the first part (demo GR: δήμος) meaning “ordinary people” and the second part (cracy GR: κράτος) meaning “ruling” or “State”. What is important to note is that if we choose to focus on a State in which people rule by means of equal voting, such that the different votes are aggregated to form a majority rule, we miss an important quality: The ending of the word democracy in Greek translates into “holding the power or strength”—and this refers to the power of the people. To have a State in which all citizens have an equal vote is not the same as trusting the power of the people to from all walks of life to deliberate together to make decisions which affect them. The ancient Greek assemblies (agoras) gave people the opportunity to take part in deliberations, which were based on constructive dialogue. In the Greek agoras the citizens were supposed to exchange ideas and engage in deliberations in relation to the different ideas that were put forward by carefully examining alternatives together to clarify a debatable situation (on which they may initially have had divergent perspectives). Ideally, the propelling purpose of the discussions was that the citizens would try to come to a consensus via their dialogically searching together to achieve a collective wisdom that would be shared by a great majority of those participating.

The resultant collective wisdom can be regarded as a mode of intelligence achieved through “knowing together” (cf. Gergen, Citation2009; Kuby & Christ, Citation2019; Nicholas et al., Citation2019; Ossai, Citation2010; Rajagopalan, Citation2020; Rajagopalan & Midgley, Citation2015; Romm, Citation2017; Roth, Citation2018; Shotter, Citation2016). It is process-based and is a process that as Duby puts it, “unfolds in real time” as people “perform” together (as in a musical composition that requires improvization and does not have fixed notes to play). Duby continues that:

Within an improvising ensemble, musical decisions require quick action and generally are not specified in advance by a central controller (i.e., a conductor …). In free improvisation, there is a very wide range of possible decisions [as people respond to others’ performances by being attuned to them]. (Citation2018, p. 91)

This is a similar process to what many Indigenous scholars and seers (in different geographical regions across the globe) call “relational knowing” (cf. Collins, Citation2000; De Quincey, Citation2005; Kovach, Citation2009; Meyer, Citation2008; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018; Ngara, Citation2017; Wilson, Citation2008). It is knowing developed in relationship and it expresses the outcome of people’s exchanges, based on carefully listening to others’ statements (as expressed and as clarified during the course of the discussion) and based on people’s being open to change their own ideas as they together develop new ways of thinking. This then becomes the knowledge basis for the making of action-oriented decisions or policies, to which people by and large feel committed.

As indicated earlier, this way of practicing democracy is not akin to the “pluralist” model of democracy with its assumption that the common good could arise as a result of the aggregation or combination of the diversity of (undeliberated upon) interest-based preferences. Dryzek (Citation2006, p. 124) points to the arguments offered by “deliberative democrats” (like himself) who query this model of democracy. He notes that “deliberative democrats believe preferences ought to be shaped reflectively by thoughtful and competent citizens” (and by their representatives also engaging in dialogical exchanges). He sums up (with Bächtiger, Mansbridge and Warren) that deliberative democracy can be defined as “any practice of democracy that gives deliberation a central place” (Dryzek, Citation2018, p. 20, our emphasis).

Floridia likewise points to this conception of democracy when he notes that in this formulation, the common good is considered as arising from the “collective capability for deliberation, and from the public quest for shared solutions, through debates and discussions” (Citation2013, p. 37, our emphasis). Floridia attributes this notion (deliberative democracy) to Sunstein’s account (Citation1984) which Floridia (Citation2013, p. 1) recapitulates as “Deliberative Democracy, against ‘naked preferences’”. By “naked preferences” is meant preferences that have not been subjected to social deliberation and attendant learning toward new understandings on the part of those participating.

Floridia notes that Habermas’s book Between Facts and Norms (Citation1996), is an extension of this kind of argument for deliberative democracy; and he suggests that the notion of democracy can now “properly be considered as a theoretical paradigm, both critical and normative, that acts powerfully on contemporary democratic thought” (Floridia, Citation2013, p. 9). In other words, this notion of democracy allows us to query the operation of apparent “democracy” insofar as it does not match up to this potential promise (as expressed in the ideal-type of deliberation). In his book Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (Citation1989), Habermas criticizes the way in which the “public” sphere in many so-called democracies amounts to citizens following the “aura of personally represented authority,” where public figures display their positions with the intent of trying to persuade followers (often misleadingly), rather than encouraging a process of “public critical debate” making up the “public sphere” (Citation1989, p. 201). Deliberative democracy as Habermas understands it is very different from people’s passive listening to the way in which potential candidates in electoral run-ups present their positions in the media for people to become “persuaded” by (without critical engagement with simplified positions and promises as presented) as a basis for making their preference at a voting poll.

A recent example from Kenya serves to illustrate this point. Nyadera et al. (Citation2020) note that enshrined in the Kenyan Constitution of 2010 is the right of leaders (of political parties) to compete and seek support from voters (Citation2020, p. 6). They indicate, however, that this principle can become “undermined by ethnic-based political parties and voter bribery” (Citation2020, p. 6). One way in which they believe that the problem of ethnic based politics creating strife and bribery can potentially be addressed is by combining majority and consensus-types of democracy in what they call a “mixed model” (Citation2020, p. 6). The mixed model means that instead of the results of voting being added up to determine “winners”—as in aggregative democracy—a consensus arrangement is also sought. This, they believe, could be the “anchor of the future” (p. 12). However, they do not indicate the kinds of public participation that might be involved in enacting a consensus model, along with the majoritarian one. All that they refer to is the need for political actors (leaders and would-be leaders?) to “show goodwill” in their relations with the different sectors of the society. A key challenge of today’s model of representative democracy is how to keep the elected (or appointed) accountable to their promises. More frequent sampling of citizens’ satisfaction and opinion using digital voting, in connection with reforms of the electoral systems (e.g., to allow horizontal voting: Laouris & Shoshilos, Citation2014) could significantly shorten the feedback loop and improve the control and accountability process.

What Nyadera et al. do point to, which is also relevant for this article, is the way in which the media houses in recent elections supported media coverage of leaders who presented themselves via different media so that the electorate could make their choices (for leaders) on this basis. But they indicate that the media houses did not always “strive to ensure that fake news or biased coverage of aspirants was discouraged”. They indicate that in the 2017 elections there was much “fake news,” defined as “a form of yellow journalism aimed at spreading hoaxes or misinformation deliberately through broadcast media, traditional media, and social media”. That is, the media often became used to “manipulate” people’s thoughts to mislead them (Citation2020, p. 6). They summarize that:

To what extent the fake news affected the outcome of elections in Kenya is still difficult to determine; however, the relationship between information and public opinion is very critical and must be preserved at all times. (Citation2020, p. 6)

They compare this problem with the way in which the 2016 election campaign in the USA was also orchestrated, for example, in the smear campaign against Hilary Clinton. (In their understanding of fake news, they would not concur with Trump’s conception, where he defines as “fake” any critical attempts to hold his office to account, so as to emphatically re-iterate his own messages.) Clearly, a challenge for democracy is presented when “public opinion” is not a matter of the populace participating in discussing and critically reflecting upon “information/ideas” together.

So while Nyadera et al. believe that Kenya can be progressive in offering a mixed model of democracy where the “merits and demerits of combining elements of a consensus model of democracy with a majoritarian system” is experimented with (Citation2020, p. 12), it seems that the challenge is still to institute a public sphere which involves the public in genuine participation toward seeking solutions that will serve the “common good”.

Moss and O’Hare (Citation2014) concur with Nyadera et al.’s caution when they refer to the televised debates that characterized the 2013 elections in Kenya. They see these debates between the candidates seeking Kenyan presidency as being

“media spectacles”, designed more to impress than to inform the nation’s electorate. Indeed, … we aim to show that actual debate between candidates was of secondary importance to the broader image being portrayed on screen. (Citation2014, p. 79)

They feel that the debates held on television supposedly around issues of concern to all Kenyans had a positive side in that they implied “a crucial stage in the movement away from the politics of ethnicity and personality, towards a form of issue-based politics,” but they are wary of a political climate organized around “key media organizations’ mindsets” and their roles in “the run-up to the [2013] elections” (Citation2014, p. 80). They suggest that Douglas Kellner’s (Citation2009) concept of “media spectacles” (which he applied in relation to the mainstream media in the USA) helps us to recognize that “debates as media-constructed performances” are not tantamount to public deliberation—as “the public” became spectators of the “media spectacles,” which can all-too-easily simplify the issues at stake, or even mislead, in order to impress “the public”.

In commenting on Africa and the prospects of deliberative democracy, Ani adds to these accounts by indicating that neither the aggregate model (based on counting up voter preferences) nor the consensus model (unless underpinned by a process of deep deliberations in the public sphere) “works” to engage the public in participation. He proposes that deliberation, beyond mere voting in a multi-party system, and beyond leaders bargaining toward consensual arrangements as part of the system, is needed. As he points out, “for a decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by deliberation” (Ani, Citation2013, p. 207).

Ani states that he agrees with arguments which propose that:

when adequate justifications are made for claims/demands/conclusions, deliberation has the potential to have a salutary effect on people’s opinions, transform/evolve preferences, better inform judgments/voting, lead to increasingly “common good” decisions, have moral educative power, place more burden of account-giving on public officers, and furnish subjects [who are] outvoted with justifications for collectively binding decisions. (Citation2013, p. 207)

This iteration by Ani was by and large embraced in the re-invent democracy project discussed in this article, which explored the challenges as well as prospects for democracy in the digital age (also considering various commentators’ observations of how easily “misleading” news can be spread and how this might be countered). With this as background, we now turn to the question of how the SDD process incorporates the understanding of deliberative democracy as based on learning networks where people deliberate in search of consensus.

The Search for Consensus via SDD

Most proponents of SDD consider Habermas’s conception of deliberative democracy as a suitable account of what (genuine) consensus seeking amounts to. Space in this article does not permit a thorough examination of this, but suffice it to say that Habermas argues that in forms of genuine dialogue (as an ideal-typical set up), the parties to the dialogue direct themselves to trying to achieve consensus through listening to the perspectives as provided by the dialogical partners and adjusting their views accordingly, insofar as the reasoning and expressions of concern sound “valid”. Some authors claim that Habermas’s understanding of communicative processes as ideally oriented toward achieving consensus does not cater sufficiently for a recognition of dissensus as an enduring feature of our social living together—cf. Bernstein (Citation2006); Lyotard (Citation1984, Citation1993); Derrida (Citation1992); Derrida and De Cauter (Citation2006); Morris (Citation2006). However, a closer look at these various authors’ positions, indicates that such authors are also concerned with ways of our “being together” for which we can become mutually responsible.

In considering the “new technologies of language (in the digital age), Lyotard in 1993 already considers that these new emerging technologies have the potential to “directly handle the social bond, being together”—independently of “traditional regulation by institutions” (Citation1993, p. 17). Furthermore, in the Derrida-Habermas reader (Citation2006), in a chapter called “a last farewell,” Habermas’s way of bidding farewell to Derrida shortly after his death in 2004, is published. Habermas sees connections between Derrida’s ideas concerning “deconstruction” and Adorno’s “negative dialectics,” as both presaging a thrust to being reconstructive (Citation2006, p. 307). Morris (in the same book) too sees connections between Habermasian-type deliberation and Derrida-type deconstruction, as equally trying to make room for “democratic political space” (Habermas, Citation2006, p. 231). In addition, Bernstein indicates that Derrida’s concept of “democracy to come” is meant to bode us against identifying “democracy” with its present institutional forms, so as to seek alternatives (Citation2006, p. 91). As similarly remarked upon by Rajagopalan, “we now stand at a cusp where our future is suddenly uncertain—some of the great institutions we relied on, such as capitalism and democracy—are showing ruptures” (Citation2020, p. 6). Rajagopalan considers that “there is a dimly growing recognition that this situation, … is fundamentally, an epistemic failure,” although he feels that “this understanding [of the importance of increasing our capacity for developing collective wisdom] is still at the margins” and needs to be “center-placed” in order to begin to address our current “growing welter of large crises” (p. 6).

What is vital to emphasize is that in line with the intention to regenerate the promise of democracy, the SDD process indeed “center-places” this epistemology, and encourages stakeholders involved in deliberations to review their initial ideas/views (and their significance) toward the eventual co-construction of maps of understanding that express their deliberated-upon collective intelligence. The map does not necessarily present a 100% consensus, but is made up of pair-wise comparisons of the direction of influence of ideas to which at least 75% of the participants agree before it becomes part of the map. (The facilitator continues the discussion asking those who either believe or do not believe that achieving idea X will significantly impact on idea Y to indicate their reasoning until 75% have agreed on an “answer”.) In this way a systemic account of connections between ideas, and considerations of their significance in addressing issues posed as problematic for realizing a better future, is built up. This means that the rhetoric or superficial accounts perpetuated by powerful forces in the society (which Habermas calls the systems of money and power) can become overridden in processes of public debate. (See Bausch, Citation2016; Romm, Citation2001a, Citationb; Staats, Citation2004 for further expositions/interpretations of Habermas’s position.) The rhetoric which supports the systems of “money and power” and which distorts people’s genuine communications, thus can become “deconstructed” (to use Derrida’s language, Citation1992, p. 38) as ordinary citizens come to recognize its superficiality. Genuine dialogue in the public sphere implies for Habermas generating a system of discourse of ideas about how to achieve a just society, which takes into account the complexity and heterogeneity of society (Staats, Citation2004, p. 584).

Consistent with this understanding of the public sphere, the purpose of SDD is ultimately, as Jones puts it, to use a

systems thinking methodology developed from principles of communicative action, dialogic design facilitates diverse groups in disentangling core issues from complex, interconnected problem areas … using computer-assisted information displays to generate and maintain a shared [or largely shared] common ground throughout dialogue. (Jones, Citation2008)

It is however, important to bear in mind Staats’s caution (Citation2004, p. 585) that in Habermas’s writings, there seems to be insufficient attention given to the threats to democracy posed by the “influence of the modern mass media,” which can all-too-easily create what Staats calls a “system-wide false consciousness”. Ortega too reminds us of the “agenda setting of the media” and their potential influence on the public, with implications for the operation of the public sphere as a genuinely communicative sphere (Citation2012, p. 273). This is one of the challenges to democracy in the digital age which was examined in the “re-invent democracy” project as discussed in this article, with attention also to the opportunities provided by existing and emerging digital technology to reshape the future direction of democracy.

The Methodology Employed in the Re-invent Democracy Project

Formulating TQs and Recruiting Participants

As indicated in our Introduction, SDD processes are always structured around a set of TQs. Potential participants have an opportunity to see the TQs before applying/agreeing to participate in the planned dialogical sessions. This has two functions. Firstly, it means that those who apply and/or are selected are aware of the arena of dialogue; and secondly, people can prepare some of the ideas beforehand, so that they already have given some thought to the questions (Laouris, Citation2012, p. 255). The selection of the TQs for the re-invent democracy project of course had to be carefully reflected upon by those formulating the questions, because not “everything” can be discussed, as emphasized by Midgley (Citation2000, Citation2001, Citation2008) in his account of the making of boundary judgements in critical systemic thinking. In this case, the implementing organization, Future Worlds Center (FWC), felt that “democracy” was in urgent need of re-invention, especially to take into account the challenges and the opportunities for democracy in the digital age. This then became the substance of the two TQs that guided the project:

TQ1 What are the shortcomings of our current systems of governance that could be improved through technology; and

TQ2 What concrete action, project or product would you propose to solve a particular shortcoming of current systems of governance?

How, then were participants selected for participation in SDD processes (that is, how was it decided who would be invited/selected to participate)? This is another kind of boundary judgment that Midgley identifies as needing to be made in any research/learning project, because not everyone can be selected as stakeholder (see also Gregory et al., Citation2020, p. 322). The idea behind SDD is that those people who are (most) concerned with, and/or affected by the issues under consideration should become the primary participants; furthermore, attention is also given to the involvement to those who have previously been relatively marginalized in terms of participation in social discourses. In the case of deliberating about our future, the youth being the main owners of the future are of course prime contenders for participation; but meanwhile they are often side-lined in democratic discourses. Hence the re-invent democracy project focused in the first instance on “youth” (18–30 years of age).

The youth who became participants in the project were chosen on the basis of a number of criteria that the FWC team applied in assessing the submissions submitted to the FWC, following the project being advertised in various forums globally and nationally (using global alliances and various social media). What was firstly important was that provision needed to be made for a variety of viewpoints/knowledge-bases, so that the discussion could proceed on the basis of sufficient breadth of ideas. Hence years of relevant experience and prior relevant activities became criteria of selection. Youth were also selected on the basis of their being potentially influential as young leaders, and as belonging to associations with wide networks. The commitment to the project (as sensed by the team by perusing the applications with the attendant videos) was of course taken into account. Their country of origin was also considered, so that participants from a range of countries in the region could contribute to the discussions. The FWC team also ensured a balanced gender distribution of participants (to counteract the problem that politics are often “monopolized” by men). Other criteria that were applied were their communication skills and that they had uninterrupted access to social networking ().

Table 1. Weight given to each criterion.

In the African cohort, countries that were represented were: Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe (with 16 core participants). The week-long dialogues were held in Kenya (9–13 May 2016) at the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development.

Week-Long Process for All Five Regions: SDD Co-laboratories plus Last Day for Action Plans

Week-long sessions (called co-laboratories in the SDD literature) were held with all five groups of participants. The five-day sessions all followed the same format: Two days were spent on TQ1 (namely, a critical systemic examination of shortcomings, with a view to considering the potential for improving democracy in the digital age). Then two days were spent on TQ2, namely, the development of their collective understanding of the “deep drivers for change,” which could serve as an inspiration for significant action to be pursued (by the participants or by others inspired by the maps, which were later made accessible on the internet via a Manifesto, Laouris, Citation2017). The final day of the week was put aside for participants in groups to create action plans for themselves to pursue, springing from the collective work in locating leverage points for significant types of action while working on the second TQ.

On this final day the participants of various action groups in each region offered their concrete proposals and guidelines for action that they foresaw as feasible and necessary, with the goal to increase youth participation in democratic processes. The groups presented their ideas to the co-participants in the region: Selected participants were trained to act as multipliers to support and maintain the ideas of their respective groups. These individuals monitored the actions of the group with the support of the project leaders at FWC, toward their reporting on the final results (as presented in the individual final reports for all the regions, 2017—https://www.futureworlds.eu/wiki/Reinventing_Democracy_in_the_Digital_Era_(UNDEF)#Final_Reports). That is, a particular person in each case, chosen by each respective group, assumed the responsibility to coordinate communications. That person received a small grant to be used to implement the group’s actions and initiatives as conceptualized. (The criteria for awarding the grant included the commitment and previous contributions of the applicant(s) as well as evaluation of the potential of their proposed activities to serve the wider dissemination of the ideas, the change of attitudes and participation levels of youth and the sustainability of the project at large.) In the case of the African cohort, the grant was awarded to a team of three participants who planned to generate panel discussions on local community radio and TV in Kenya and Uganda, in addition to setting up educational activities for women and youth on governance and democracy, with attention also to “social media engagement” (so that social media could be used to develop increased discussion around governance and democracy).

It can be said that these action groups (in all five regions) were a primary force of the envisioned results because, after all, the whole process was meant to inspire and propel action (on a regional and global level). Feedback that we received in October/November 2019 via questionnaires and follow up Skype interviews with about five participants from each region, offered us a further indication of the kinds of additional action the participants had become involved in, other than the planned projects as discussed during the final day of the week-long sessions. (Later in the article we offer a glimpse of such feedback, as pertained to the African cohort.)

We have concentrated in this section on how the SDD co-laboratories in the case of the re-invent democracy project included support by the FWC team in encouraging follow up in the arena of action. We regard this support as a fundamental innovation to the “normal” practice of SDD, which does not normally pay attention to following up how the participants choose to activate their (collective) learning. For this reason, we have foregrounded this in this section.

In the next section we outline the generic use of SDD which became for the most part practiced in the structuring of the co-laboratories in the re-invent democracy project, with some minor modifications.

The SDD Co-Laboratory Phases as Practiced Also in This Project (with Some Modifications)

The Generic SDD Phases (in Relation to Any TQ)

During the first 1–2 h, each participant (in robin-round format) proposes single-sentenced Statements in response to the TQ being considered, without being allowed to elaborate on the meaning of his/her contribution. In the next 1–3 h, the group reviews all Statements one-by one, and the other participants may now ask the corresponding author for clarification. Judgment questions are not allowed in this step (or indeed in any step).

In the next step, called Clustering, a bottom-up approach is applied in order to cluster all Statements into groups according to similarity. This leads to a bottom-up discovery of Categories (based on people’s considering each other’s reasoning around the affiliation between ideas and finally based on 2/3 majority voting as to the final Categories and their names). The purpose of engaging in the joint clustering into categories is that people gain some kind of shared language in relation to the meaning of the various statements falling under the categories. It thus gives participants a further opportunity to listen to others’ perspectives with view to clarifying the meaning of statements (as defined in relation to others with which the statements are considered as having affinity or not). Finally, participants are asked to choose, among all Statements, five they consider as the most important. The Statements that receive two or more votes enter the final discussion (i.e., the pair-wise comparison step) in which participants explore

In the pair-wise comparison stage (no matter whether the TQ is directed to seeking to generate maps of connections between Challenges or maps to locate leverage points for Actions), influence relations between two Statements at a time, are sought, using a question like below:

If we make progress in addressing Challenge (or Action) X [a Statement/Idea] will this help us SIGNIFICANTLY to address Challenge (or Action) Y [another Statement/Idea]

The first influence map expresses the map of Challenges and their systemic influence on each other. Interpretations of the map are then invited so that participants can interpret and discuss together what they consider this means in terms of the issues that need to be tackled as priority This paves the way for the next TQ (namely, deliberations around prospects for Action which are most likely to help realize the envisaged changes).

The generic process (whether discussing Ideas around Challenges or around Actions) can be represented as follows

The implementation of an SDD Process (SDDP) goes through the steps shown in , which have been explained in great detail many previous write ups of SDD applications, as indicated in our Introduction. This was the generic process followed also in the re-invent democracy project. However, some modifications were made using additional technology (over and above version 3 of the Cogniscope), as pointed to below.

Some Process Innovations Used in the Re-Invent Democracy Project

The main differences from what can be called the generic SDD in the re-invent democracy project was the additional use of technology called Idea Prism and Concertina Walls. The Idea Prism was used firstly to enable participants before they attended the sessions to introduce themselves, explain their motivation to participate, and also state their preliminary ideas (using this shared technology) responding to the two TQs, so that they would already have given some consideration to the issues. Once they arrived at the sessions, they were asked to “convert” their ideas into a single-sentence statement in each case. Furthermore, during the sessions each participant was asked to stand in front of the group and “pitch” their ideas for 1–2 min, by way of clarification. Further clarifications were also invited as per the usual SDD practice. All clarifications were recorded via the Idea Prism App (typically using their own mobile device) and made available to the cloud and on YouTube, so that the Shadow participants as well as the Core participants could review them at any time. The “logic” of asking youth to express their ideas in front of an audience and a camera was a conscious one on the part of the FWC team, meant to perform the function of enabling young citizens to learn how to verbalize and share their ideas (while the audience asked clarifying questions; a form of capacity building). That is, given the aim of the project to be “transformative,” this innovation had the transformative intention of enabling the youth to feel more “empowered” not only to share, but also to communicate and promote their ideas after the workshops.

Once all people’s Statements were clarified, the participants proceeded (as is normal SDD practice) to cluster them into Categories and to name the Categories. But another innovation introduced in the re-invent democracy project was to use a Concertina technology to project the various statements (with the Clustering) onto the “wall” for everyone to see. This was before the participants proceeded to the stage called the pair-wise comparisons, where maps of influence could be generated through the Cogniscope (which were also displayed on the wall, as is “usual” SDD practice, so that people can in turn participate in interpreting the maps). The projection of all Statements and Clusters onto the wall (to further facilitate the SDD process) was thought to be helpful in aiding the participants to “remember” the essence of the various statements as clarified and clustered, while they were partaking in the pair-wise comparisons toward the creation of the maps of influence.

In the results section below, we provide details of the steps leading to the two Influence Maps generated by the African cohort, which point to their collective wisdom, and which offer what we consider to be novel ideas for re-inventing democracy in the digital age. (The full report of the African cohort is available online3)

Results of the African Cohort’s Deliberations

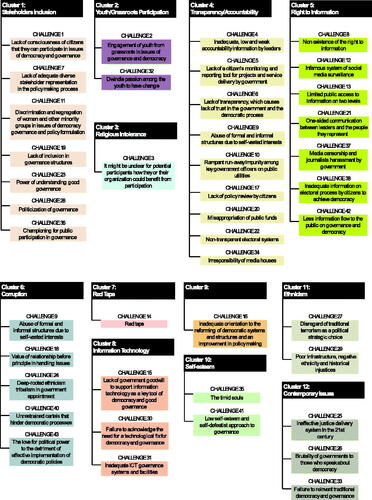

In this section we turn to some of the “content” that emerged as a result of the deliberations of the African cohort. To start with, the Ideas that were developed and Clustered into Categories in relation to TQ1 resulted in the creation of 12 Categories as shown in .

A lot of what is being discussed among the participants in an SDD session cannot be shared in a short article like this, but it can still be found in the original reports in which also the extended clarifications of each statement are reported (see Note 3). For example, poverty, insecurity and militancy which are major challenges in youth engagement in African societies, might not appear directly in the above statements or clusters, but they appear in many clarifications and they have also emerged in the larger themes when text analysis was conducted using word clouds (see below).

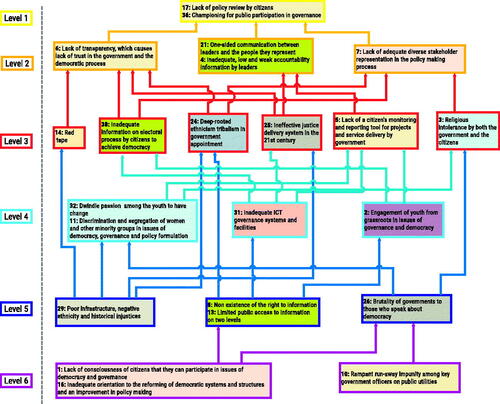

In accordance with SDD practice, participants then each chose five ideas they considered as important to enter the pair-wise comparison phase. In total, 28 of the 43 original ideas received one or more votes, and thus entered the pair-wise comparison phase. Interestingly, this meant that in terms of a parameter called “Spreadthink” there was a high percentage of this (where N is the number of ideas and V is the number of ideas that receive more than one vote). This implies that to start with the participants displayed a high divergence of opinion and cannot be said to have been subject to what is sometimes called “Groupthink” (where people tend to concede with each other too early in the discussions, as noted by Wojciechowska, Citation2019). The 28 ideas were then subjected to the pair-wise comparisons phase, using a version of the Cogniscope technology, with the facilitator ensuring that deliberations proceeded until 75% of the participants agreed or not on whether addressing Statement X (as a Challenge) would significantly alter attempts to address Statement Y (another Challenge). The resultant influence map is pictured in .

The same process was followed for TQ2. The Clusters which were created in relation to TQ2 are depicted in .

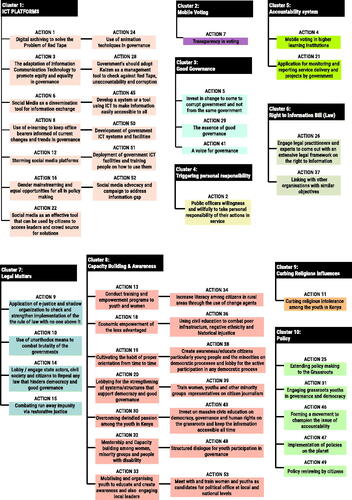

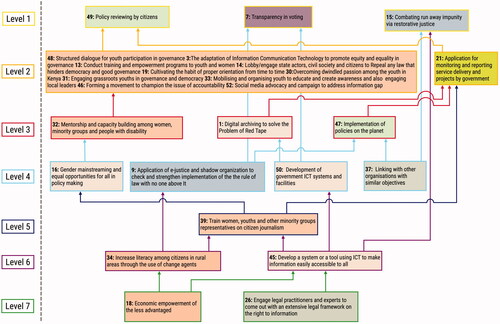

Again, there was a high percentage of Spreadthink to start with in terms of choosing Statements to enter the pair-wise comparison phase. In this case, the participants created the Influence Map by first structuring ideas with two or more votes and then used a re-voting process (choosing from action proposals that received one of no votes) so that additional proposals could be structured to form the “final” Influence Map in relation to key Actions. This map is depicted in .

When perusing the maps drawn in and , readers can consider their novelty and whether they feel that this in turn aids their own understanding of challenges in Africa and/or elsewhere in the globe and offers fresh ideas for involvement in significant action to regenerate democracy. We will not venture to offer any of the mappings as “prescriptions” for conduct; but we will underscore that they represent the results of 800 h of careful deliberation by concerned African youth, all intent on invigorating democracy in the digital age.

What we will highlight is that in , the Level 6 Statements (that is, Ideas, 1, 10, and 16 at the bottom of the “tree,” exerting most influence on the ideas at other levels) refer to: the “lack of consciousness of citizens that they can participate in issues of democracy and governance”; “inadequate orientation to the reforming of democratic systems and structures”; and “rampant runaway impunity among government officers on public utilities” (that is, their unaccountability). These were all Challenges that were taken forward by the action group awarded the grant which we mentioned above when discussing the time set aside on the last day for “action plans”. (When we interviewed certain participants in October/November 2019, the ones involved in this project again made reference to this.Footnote4) The issues considered as the most influential Challenges to address (as expressed in Statements 1, 10 and 16 of ) also filtered into the influence map expressing deep drivers for change ().

Level 6 (at the penultimate level of the “tree” of ) refers to Statements 34 and 45, with Statement 34 being the need to increase literacy among citizens in rural areas. As indicated above, the new radio programs and other use of community discussion panels in the media by the grant-awarded “action group” were tackling this. The other idea on level 6 of this tree was to “develop a system or tool using ICT to make information easily accessible to the public,” which in turn would increase the likelihood of officials having to be more accountable as they could no longer use information in a misleading fashion. This was an initiative in which another of the participants whom we interviewed in November 2019 was working, by her becoming involved in an African Union institution called the African Governance Platform. She indicated that her involvement in the re-invent democracy project had been empowering for her in that it piqued her “curiosity and interest in participating in governance issues and youth participating. And I really loved that we used technology, I love technology and would love to do more with tech”.

As far as economic empowerment of the less advantaged (Idea 18 at the bottom of the tree, on Level 7) is concerned, one can say that all of the participants whom we interviewed in 2019 in some way were trying to forward this, mainly through setting up educational opportunities for people as a route to improving their empowerment. One participant had founded a particular organization in Kenya—Elgon Center for Education—which was making progress in this regard. He mentioned also that he felt that while addressing economic issues it is important to take into account and raise awareness of the problem of the natural forests and good soils for agriculture around the Elgon mountains being massively destroyed of late. He was using his blog as well as the Elgon Center for Education Facebook page as media to write articles to increase awareness of this as an issue (which he stated in our interview that the RD co-laboratories had helped renew his interest in putting his energies into this). His concerns are consistent with the views of ecological economists who decry the way in which an economic system geared around profit-making tends to exploit “nature” in the name of profit, and are also consistent with the tenor of Smitsman et al.’s pointing to the importance of the quest for “ecosystemic wellbeing” (2020, p. 218). The understanding of ecological issues was also expressed in nearly all the interviews (from all the regions) held with the sample of participants in October/November 2019. That is, “economic empowerment” was not seen as at the expense of the wellbeing of the planet.

Also, at the bottom of the tree in was Idea 26, which refers to the need to “engage legal practitioners and experts to come out with an extensive legal framework on the right to information (as a means, inter alia, to mitigate against government officials being held accountable). One of the participants whom we interviewed in October 2019 who was a lawyer, had advocated (successfully) for the law in Ghana to be changed. He remarked in the interview that although there had been a law regarding the right to information, one aspect of the law still had made it difficult for people to get access to information—that is, there were limitations on the kinds of information that was accessible. But with a lot of pressure from civil society, lawyers (including himself) and the general public this aspect of the law had been taken out in 2018. He regarded this as an important breakthrough in Ghana. According to him his involvement in the re-invent democracy project inspired him to write more in the social media and to talk on the radio, with a view to Ghana offering an example for other African countries which were in similar situations.

This participant also mentioned that besides the changes in the law regarding the right to information, in one of the previous elections in Ghana the way in which the election had been handled was challenged in court, and this led to a reform of the electoral process. He stated that in subsequent elections there was transparency from grassroots level, so that at the end of the voting at every polling station the results are posted for everyone to see. Prior to this, results were sent to a coalition center which then decided how the general public gets to know the result. The participant had been personally involved in advocating for the electoral process to be more transparent (and was using various networks to disseminate ideas for transparency in the rest of Africa). He and one of the participants who was a journalist (from Kenya) whom he had met during the re-invent democracy project were now trying to use their journalism to make an impact in Africa. The journal in which they are involved, set up by this journalist, is called “Signature Africa Journal”. Incidentally, when he was asked during our interview with him if he felt this was relevant only for Africa, he commented that he realized that many of the issues that the African cohort had identified as problematic, are globally relevant, albeit in different ways. He referred to the apathy when it comes to voting in Europe—he remarked that people do not want to vote because they think at the end of the day their vote is not going to make any difference. Also, he felt that they often do not have confidence in political leaders, as another example of a global problem.

Other participants who had read or glanced at the various reports that had been sent to them after they were finalized (at the end of 2017) expressed the same sentiment—that although there were issues and prospects of significant action specific to Africa, there were many similarities too. In summary, this brief reference to some of the interview materialFootnote5, offers a glimpse of how the participants’ involvement in the collective SDD enterprise had been helpful in identifying areas for significant action in Africa, and how some of the ideas could also pertain to problems of the functioning of “democracy” in other parts of the globe.

Meanwhile, while compiling the various regional reports and the Manifesto, the FWC team themselves undertook to create comparative analyses, based on a number of methods of analysis, which we will not detail here as they are detailed in the Manifesto (available at http://futureworlds.eu/w/1/b/b7/Manifesto_Democracy_in_the_Digital_Era_20181222.pdf). In brief, word clouds expressing the frequency of words used in all the statements across the regions; word connections expressing the way words were connected with other words in the various regions, examination of the issues which were named in Clusters across the regions, and examination of the Statements that appeared at the various levels of all the Influence trees (with statistical priority given to those appearing at the lower levels) resulted in 7 themes (some with subthemes) finally being identified as relevant across the globe, taking into account the collective wisdom of all the youth who had participated in the project. The themes (all with novel options for action outlined) can be found on pages 10–13 of the Manifesto. The themes themselves (which clearly all in their naming below already express an action-orientation) as identified are:

Participation of all Stakeholders

Effective Participation

Effective Management and Governance in Public Spheres

Abolish Corruption

Eradicate Violence, Poverty and Injustice

Citizenship Education

Harness the Digital Era to design new models of Governance

The authors of the Manifesto (Laouris, Citation2017) mention that “this Manifesto is only the beginning toward designing a new world that is sustainable, just and ethical” (p. 13). The authors urge readers via the Manifesto to consider seriously the ideas as generated by the youth in their concerted deliberations around prospects for “re-inventing democracy in the digital era”.

Some of the Participants’ Expressions of Appreciation of the SDD Process

When we received feedback from a sample of about 25 participants across the regions in October/November 2019, participants by and large recalled that they had not been intent that “their” initial ideas/Statements would enter the pair-wise comparison phase; and nor when it came to this phase did they vote to consider “their” Statements as the significantly influential ones. Rather, they had strong memories of having participated in a process of collectively arriving at a better systemic understanding of influences so that they (or others) could become involved in what Smitsman et al. (Citation2020, p. 215, citing Bateson, 1972) call “the difference that makes a difference” in the realm of action. In this Section we highlight how a few of the participants from the African cohort expressed this.

One of the participants, when asked to comment on whether the way of facilitating the SDD process meant that people who initially had different views could come to a deeper insight on which they agreed, answered that:

A: Yes. throughout the week of engagement, using myself as an example, I had issues where I didn't really buy into others' views because they were too serious. But as we had chances to explain our views and give more reasons why we think it should be accepted, I started to accept what others said. So yes, from the beginning there were some conflicting views, but there was a point where we got to explain our ideas, that is when we began to accept other ideas as more pressing than others.

When probed about whether she felt that “through the whole process a kind of collective energy was being generated; that somehow in the room people were bonding and feeling connected to each other and that there was a group energy?,” she responded strongly in the affirmative:

A: Yes. I really felt that. The first thing I would use to show this point is the fact that FWC brought us from different countries where we didn't even know each other, we had never met. Even in Ghana, we were 3 people but we didn't know each other. But we went there together and put ideas together, we discussed and we became like family. There was this kind of unity. And even after we left Kenya, we still have this bond as if we are still in Kenya because we really discussed and chatted a lot and we still follow up with each other. So, there was this feeling of ownership of what we did that graduated from Kenya [from the re-invent democracy project] and has followed us until now and we still discuss with each other. [She was here referring to the Whatsapp group that had been set up and also Facebook communications that too had been set up during the re-invent democracy project.]

She continued that:

We are still learning from each other because we had different backgrounds, some were journalists, some were project officers, etc. So even though our communication and some explanations, and exchanging contacts, networking with each other we learned from each other. We learned what goes into their media, how youth can actively participate in governance, etc. So, we are still learning from each other.

Another participant who was interviewed commented that the facilitation via the SDD process meant that everyone participated:

This [SDD process] was making everyone contribute because our contributions matter, and nobody could criticize another because of their contribution didn't sound well or you didn't understand. Also, when someone make a contribution and you have a different opinion, but when that person is given the opportunity to explain, then you have a better understanding. For example, the mobile application that we used. If someone makes a contribution, there is an opportunity to ask that person for their explanation. When that is done you really get to understand what that person's point is. So with my experience from [other] projects, this is what struck me about this process.

He went on to make the point that when you “changed your mind” it was “not because you were forced to, but because you listened to others’ opinions”. He added that:

Some of the contributions that were made caused conflicting opinions and even times where we felt that people's opinions were too harsh. But once we went through the process, then it became clearer and we got to know we are actually talking about the same thing in different ways [and so they realized there was common ground].

He pointed out finally that the SDD process is “an alternative way of making decisions in a group”.

By way of offering a further glimpse of what struck the participants as “alternative” about the SDD process, we refer to one more participant’s remark:

Even when it came to the issue of voting, we were not voting for our own ideas, but choosing the best five. It was so amazing that even somebody would not vote for his own idea simply because he or she sees another idea that is more pressing or more important than even their own. That was the most important thing that I learned about this SDD. That it’s not just about what you say, it's not about what you think or what you believe is right, somebody's idea can supersede yours and its good actually to listen. I was happy with everything I learned. It was new to me.

At this point, the audio recording became a bit unclear as we lost connection, but when asked whether he had been suggesting that what was interesting for him was that people “seemed to agree with the collectively constructed map in the end, even though initially they might have had different visions,” he answered:

A: That is true. I remember not even voting on my own opinion, and finding myself voting of other people's ideas because I thought that was really the key challenge. So, I find it very interesting because it showed that when we come together to discuss things and we give each other an opportunity to speak and opportunity to contribute then we can find out that we might have one idea but different versions of understanding. It was very important for me. I loved it and even in my academic mentorship, I'm trying to use a kind of structured dialogue to find out the cause of why our students are not performing well. And I have received really interesting things [outcomes], and I am working to come out with a final report at the end of this year that will inform our next project and even deal with other education stakeholders to find out the root causes. So, it is very important and I like that you can think of something and somebody can think better than you or explain better than you, in order to be understood by everybody.

When probed whether he remembered “the pair-wise comparison voting, where you had to say “IF X was done, would it influence on Y?”, he affirmed:

A: That is true. I remember that process. And I remember that was the foundation of our discussion, it was even more clarity. “Will this thing help solve this challenge; will it have a significant improvement in changing the other?” It was interesting. There were those that we could outrightly say “yes”. And then at least two or three people would say “I don't think so.” and then we give that opportunity to explain. And sometimes we could discuss a lot until we came to an agreement that, “Yes, I think to some extent, or no it cannot”. So, it was also an interesting discussion. That gave us independent thinking, critical thinking part of our discussion. Because there were those people that just participate in a conference, or in a talk and all they do is say “yes, yes”. But it is not just about saying yes, it is about critically thinking, why are you saying “yes”. And that came out well in our Re-Invent Democracy session, that when you say yes, somebody will say no and then we start discussing. So, it promoted a certain kind of critical thinking in us. I think it was one of the wonderful sessions.

And when asked: “did you feel that in this process a collective energy was being established?”, he responded:

A: OH YES! Oh yes. As I said, I have attended several functions with people discussing things, but after such these kinds of meetings everyone leaves and we forget about each other. But for this team, we are still together, still conversing. Even if we are not talking about something very important, we are still keeping in touch because of what came out of that collaboration. It was all collective energy, and the young people we met there are people of substance in Africa and trying to do something on their own and that brought us a good network. We learned from each other, we learned what they are doing in their own community and country and so that also brought us together. Even when we were discussing, we were discussing with such energy and anxiety to see change. I can say that there was a lot of energy and collectiveness. It was fantastic and that is what has kept us together all these years, it’s been about 4 years now and we are still talking to each other.

These expressions of these three sample participants (that we have sampled for this article) show how they experienced the SDD process as facilitating what Habermas would call genuine dialogue through people listening carefully to one another’s ideas and not being “forced” to change their mind, but nevertheless doing so as they engaged with others. These expressions of the participants, with only some brief extracts of their statements here, provide an indication of how the various SDD phases culminating in the pairwise comparisons generated a collectively constructed critical systemic analysis, which could inspire transformative action toward re-inventing democracy.