ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in teacher educators dealing with multiple problems caused by the disruption to the professional preparation of pre-service teachers. This led to modified arrangements for teaching, learning and assessment on an emergency basis. For teacher educators, the challenges and disruptions caused by school and HEI closures may also be seen as opportunities to learn and reshape traditional roles and practices. In this study, we sought to understand how COVID-19 shaped and transformed the lived experience of teacher educators involved in school placement in Ireland. This research utilises Mezirow’s Transformative Learning framework starting with the disorienting dilemma of COVID-19 and maps the teacher educators’ responses to the resultant challenges and possibilities. Using a qualitative approach, the researchers analysed data from online surveys, focus groups and reflections, to consider continuity and change through the ‘Now What’ stage of Rolfe et al.’s framework. The insights gained from this research will add to the growing international literature on the changes to pre-service teacher education provision, by presenting the persistent challenges of dealing with COVID-19 and potential changes within the practicalities of school placement in Ireland.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt and challenge communities globally. Higher education communities have not been immune to the ongoing disruption or challenges and have in many ways struggled to respond, cope and adapt. Shankar et al. (Citation2021) report that since the emergence of the pandemic at the start of 2020 that ‘COVID-19 has transformed Higher Education’ (170), while Farrell (Citation2021) refers to Harris and Jones (Citation2020) description of COVID-19 as a ‘game changer’ and Harford (Citation2021) likens it to a ‘black swan event’ (161) that disrupted schooling and foisted unprecedented pressure on teachers to adapt and integrate new digital technologies into their broad pedagogical repertoire.

The voices of Higher Education Institution (HEI) teacher educators regarding their lived experiences since March 2020 have been largely undocumented and unheard of to date, which is a gap in the literature that merits consideration and discussion. This research focuses specifically on how COVID-19 has shaped and transformed the lived experience of Irish teacher educators involved in school placement (SP) up to December 2021 and suggests future actions that build on a transformed landscape.

Review of literature and context

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in initial teacher education (ITE) programmes being ‘put in a lurch’ (Piccolo, Livers, and Tipton Citation2021, 229) as the closure of schools and the move to remote teaching brought unexpected and unprecedented changes to student teaching. It was and is as described by White and McSharry (Citation2021, 234) a ‘nebulous situation’ which called on teacher educators to consider how ITE prepares pre-service teachers (PSTs) for life in the classroom (Kalloo, Mitchell, and Kamalodeen Citation2020). At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the actual impact on SP, especially the move to online experiences of teaching and assessment and the challenges therein, could not have been predicted (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison Citation2020).

Among the challenges for teacher educators within the pandemic, the impact on workloads, research, teaching, caring for family and well-being of staff is documented by Shankar et al. (Citation2021). Two significant challenges faced by teacher educators were the disruption to assessment practices and the transition to online teaching and assessment. Based on the learning from these challenges, Carrillo and Flores (Citation2020), drawing on the work of Hodges et al. (Citation2020), call for teacher educators to ‘go beyond emergency online practices and develop quality online teaching and learning that result from careful instructional design and planning’ (467). However, we do not know what the future will bring or what the lasting impact of the pandemic on the teaching profession will be as ‘the landscape for teacher preparation programs and student teaching is (still) currently influx’ (Piccolo, Livers, and Tipton Citation2021, 245).

As has occurred in many countries, Ireland responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 with an immediate national shutdown of all but essential services. Schools and HEIs closed for the first time on 12th March and what was initially communicated as a three-week shutdown became a prolonged closure as institutions and learners at all levels adapted to remote provision. Further closures ensued from January to March 2021. For Irish teacher education programmes, centred on collaborative and discursive workshop and practicum-based learning, the online transition was challenging and was further exacerbated by concerns about meeting programme accreditation standards. This concern was most significant for those involved in the SP element of programmes, as at the time of the school closures, several hundred graduating ITE students had yet to conclude the school-based element of their programmes.

Prior to 2011 in Ireland, there was little state intervention or regulation and the sector exercised high levels of institutional autonomy (Harford and O’Doherty Citation2016). Within a space of 2 years, the policy landscape of teacher education in Ireland altered very significantly (Lynch and Mannix Macnamara Citation2014) through reform, and the autonomy experienced, if not enjoyed by teacher education institutes, was significantly altered. Fundamental to the reform was the reconceptualisation of teaching practice to school placement, a change more significant than solely nomenclature and one which is further echoed in the most recent accreditation standards (Teaching Council Citation2020a) which asserts that ‘School placement is considered to be the fulcrum of teacher education’ (Teaching Council Citation2020a, 7). Although this assertion has been made and there is renewed focus on the role of the cooperating teacher (CT), in Ireland, volunteerism rather than formal partnerships continues to characterise the relationship between providers and schools (Clarke and O’Doherty Citation2021).

Given the centrality of SP, the closure of schools posed significant challenges for teacher educators responsible for the conduct and assessment of the practicum. As HEI providers adhered to their own schedule of placements, the priority was the completion and assessment of placements for graduating students, some of whom were at the mid-point of their final placements. At that early point, in the absence of guidance from the statutory bodies, the Teaching Council and the Department of Education (DE), SP personnel liaised with institutional regulatory committees to chart a satisfactory pathway for graduating students. Internationally, this was an unprecedented arena for all stakeholders involved in the placement process (Flores and Gago Citation2020).

Over the summer of 2020, guidance on the organisation of placements was issued by the Teaching Council (Teaching Council Citation2020) and from the DES (Citation2020). This guidance was presented as a ‘framework’, and acknowledged the importance of ‘adaptability and flexibility’ in the light of COVID-19 and reasserted the ‘imperative that school placement continues to take place’ (Teaching Council Citation2020, 2). Schools in the Republic of Ireland re-opened for face-to-face teaching in September 2020, having been closed since 12th March, and placements resumed albeit incorporating contingencies for a return to online learning for pupils and with limited in-school assessment by HEI staff taking place.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical frame for this research is presented within the larger framework of reflective practice (RP). Defining RP is complex. Liston et al. (Citation2021) refer to how RP has been defined in the literature spanning health, social care (Johns Citation2017) and education (Brookfield Citation2017) and note how RP in these contexts is encouraged for personal development and self-care (Johns Citation2017) and as a dimension and a space to connect theory and practice (Brookfield Citation2017). In the context of this study, the research team opted to use two RP frameworks to scaffold their exploration and examination of the overarching research question of the study. Mezirow’s framework of Transformative Learning (Citation1978) was deemed appropriate given the genesis of the framework as a disorienting dilemma that acts as a catalyst for transformative learning, which was relevant in the context of COVID-19. Rolfe, Freshwater, and Jasper (Citation2001) reflective model offered a three-point framework to analyse the transformation articulated in the lived experiences of participants.

Transformation theory and transformative learning

Underpinned by the work of Kuhn (Citation1962), Habermas (Citation1971, Citation1984) and Freire (Citation1970), Mezirow’s (Citation1978) original conceptualisation of transformative learning was first applied to a group of adult women returning to education or the workplace. The theory has since grown in prominence and application. Kitchenham (Citation2008) describes how two major elements of transformative learning espoused by Mezirow are, critical reflection or critical self-reflection, on assumptions and critical discourse, where the learner validates a best judgement (Mezirow Citation2006).

Both Kennedy, Hay, and McGovern (Citation2020) and Fleming (Citation2016) refer to Habermas (Citation1972) ideas on emancipatory learning and on critical reflection being an analytical tool that could engage in an archaeology of knowledge and of assumptions. Fleming (Citation2016) also mentions how we all need recognition, how ‘at work too we may be recognised for our achievements, productivity, imagination or contribution to the aims of the organisation’ (5) and how interpersonal recognition is developmental. He proposes that without recognition ‘it is not possible to become a person with values and abilities and be able to be part of debates, discussions and engage in critical reflection’ (5). He also references Honneth’s (Citation1995) argument about the struggle for recognition that Honneth proposes is a fundamental drive for survival and development and how misrecognition can be limiting and undermining. Honneth (Citation2014) is clear that the current form of neo-liberal capitalism is a form of misrecognition (239).

Mezirow’s framework and making meaning

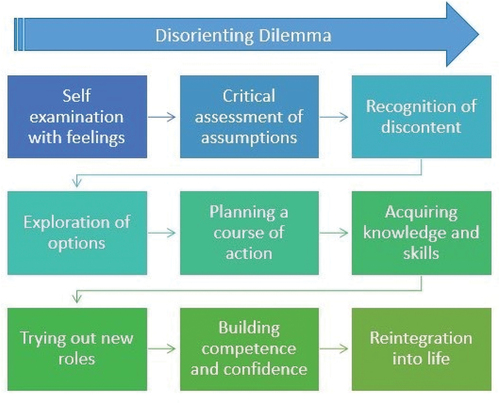

Mezirow (Citation2000) claimed that ‘as there are no fixed truths or totally definitive knowledge and because circumstances change, the human condition may be best understood as a contested effort to negotiate contested meanings’ (3). Meaning structures, which include meaning perspectives and meaning schemes are key components of Mezirow’s (Citation2000) transformative learning theory. A meaning perspective refers ‘to the structure of cultural and psychological assumptions within which our past experience assimilates and transforms new experience’ (Mezirow Citation1985, 21), whereas a meaning scheme is ‘the constellation of concept, belief, judgment, and feeling which shapes a particular interpretation’ (Mezirow Citation1994, 223). Essentially, Mezirow (Citation1991) claims that meaning structures are understood and developed by reflection and by critiquing assumptions and beliefs. In doing this, we engage in ‘learning within meaning schemes, learning new meaning schemes, and learning through meaning transformation’ (in Kitchenham Citation2008, 110). Mezirow’s framework () illustrates the various stages through which transformation of learning happens;

Figure 1. Mezirow’s 10 Stage process (adapted from Mezirow Citation1978).

Rolfe et al’s framework

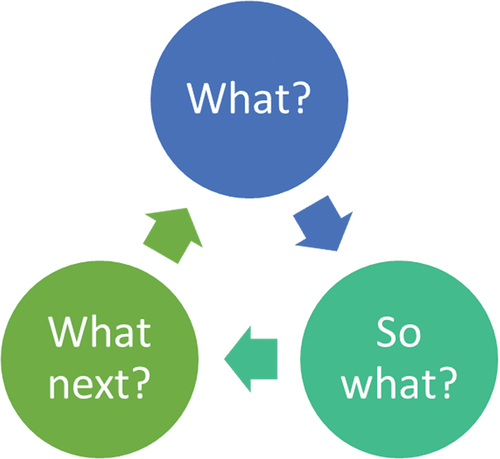

The Rolfe, Freshwater, and Jasper (Citation2001) framework uses a three-step framework to scaffold and progress reflection. The framework extends beyond ‘a radical critique of technical rationality’ (Rolfe Citation2002, 21), and instead extends to engaging in debate, discussion and outlining proposals about future actions and iterations through objective and imaginative discourse (Uí Choistealbha et al. Citation2021). illustrates the Rolfe, Freshwater, and Jasper (Citation2001) framework and prompts us to engage in critical reflection.

Figure 2. Rolfe, Freshwater, And Jasper (Citation2001) reflective framework.

Methodology

This qualitative case study utilised an online survey (n = 19), online focus group interviews (n = 3) and self-reflection accounts (n = 5) and was analysed using a Braun and Clarke (Citation2020) framework. The researchers selected these instruments to elicit descriptions of contextual insight from practitioners within the practice of SP in Ireland during COVID-19ʹs impact.

Sample and design

Ethical clearance was granted by the host university's Ethics Board. The initial survey was devised as qualitative in approach, piloted and amended in line with feedback received and then sent to 40 prospective recipients nationally by ITE providers. A response rate of 47.5% was recorded. Interviewees elected to participate in focus groups by purposeful self-selection at completion of survey. While acknowledging potential inclinations towards summary consensus in focus groups (Barbour Citation2008), the research team valued the co-creation of understanding and negotiated discourse that the interviews fostered, particularly when triangulated with other data collection methods (Caillaud and Flick Citation2017). Two participant focus groups took place online using a Zoom platform (n = 8 participants), each approximately 70 minutes in length.

A self-reflection template, underpinned by a Mezirow framework (Citation2000, 22), was also disseminated to each of the research team (n = 5). The self-reflection accounts included five overarching questions relating to the participant researcher’s context, the COVID-19 dilemma from their perspective, the strengths, the challenges, and any opportunities for change. Finally, all self-reflection accounts were read by a separate independent researcher who was not a member of the research team and not involved in the collection/coding who then conducted a third online focus group with members of the research team (n = 3).

Reliability, validity and limitations

The research is not without limitations. It is presented as a case study from one jurisdiction that utilised purposive sampling. Results therefore may not be generalisable to a general population. The research team are all teacher educators working in SP and may therefore be considered as what Sikes and Potts (Citation2008) describe as ‘insiders’ and hold latent professional biases as a result. The research team acknowledges that this research is value laden and draws on their own professional values. Thus, the team endeavoured to manage ‘multiple integrities’ (Drake and Heath Citation2008) and invited an independent researcher to evaluate and manage their self-reflection contributions to the research.

Data analysis

To ensure trustworthiness, the data sets were cleaned by one member of the research team to ensure anonymity and shared via a closed, password protected online file share platform. Each member of the research team was allocated a specific data set from the survey and three focus groups (research members), and self-reflection accounts. These were read, reviewed and open coded, following a general reading of all datasets to ensure common understanding. Following a reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2020), reflexive reading and review cycles began in order to allow for shared coding discussion and development to occur. The researchers agree that ‘themes as patterns of shared meaning, cohering around a central concept – the central idea or meaning the theme captures’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2020, 331) allows for deep practitioner research insights and honest telling of lived experiences of those involved in SP in Ireland.

Findings and discussion

Utilising Rolfe, Freshwater, and Jasper (Citation2001) framework as a mechanism, we present and discuss the findings under three main sections;

‘What’: The complexity of the school placement role

The ‘So What’: The COVID-19 dilemma and school placement management

‘Now What’: A space to readdress school placement?

‘What’: the complexity of the school placement role

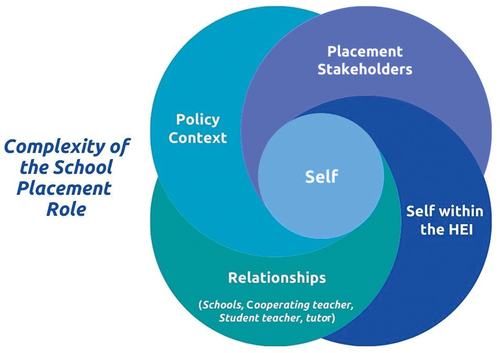

COVID-19 significantly transformed the working of SP, along with all aspects of ITE programmes in Ireland. The data indicates that the role of the SP Director or Coordinator in particular was impacted by COVID-19 in terms of workload changes as they were viewed as ‘the point of contact for all’ (FG1). The School Placement Director and Coordinator role acts as a conduit for multiple stakeholders, including PSTs, school principals, class teachers, HEI management, tutors (internal and external), professional services personnel, and involved stakeholders like the Teaching Council, Department of Education, Teacher Unions, and management bodies ().

‘So What’: the Covid-19 dilemma and school placement management challenge?

The COVID-19 shift in work practices amassed significant stress on the role undertaken by those involved in SP, especially as ‘school placement is the fulcrum for teacher education’ (FG2). Participants reflected on this pressure as ‘the most challenging and draining I’ve ever encountered’ (FG1), ‘like there were different phases of disorientation’ (Reflection 4), and ‘the complexity of SP (the many balls in the air) was brought into sharp focus’ (Reflection 5). Many commented on an additional pressure within an already pressurised, extensive role, with one participant explaining ‘it’s a non-stop train … it’s all the extensive social partners and the engagement that goes on with it. It’s vast’ (FG3).

Two particular concerns articulated in the data include (1) human resources and (2) the professional cost for career trajectory of SP Directors and Coordinators. The data evidenced a situation where the ‘amount of work … was phenomenal’ (FG1) arising from the upskilling and familiarisation of new technologies for all stakeholders. Recruitment of external staff was challenging, there was an immediate shortfall due to unfamiliarity with technology and online assessment and due to older external staff becoming unavailable;

Our recruitment during the summer of new tutors was whistling in the wind. It was really sparse … I’ve never had it so tight … we’ve never been so short on tutors, and even the tutors that are here this year, some of them saying I don’t think I can do this next year again. (FG1)

Professional cost for career mobility, especially lack of time to conduct highly valued research as was reported by Shankar et al. (Citation2021), was cited regularly by participants in the research. Recognition of the value of work and the workloads of SP staff manifested in the form of goodwill from others and was welcomed by participants:

There was suddenly a quite serious and voiced value on our work (particularly by management, by schools, by colleagues) and on the workloads that we deal with constantly. While our workloads have increased dramatically in recent years, people were almost shocked by the actual workloads when they realised the full impact. (Reflection 2)

However, others felt that the COVID-19 dilemma has ‘really stripped it [SP] back and shown the vulnerability of school placement and the lack of importance attached to it. And I think COVID has accelerated that’ (FG3). COVID-19 created such demands on SP Directors and Coordinators, who cited:

The need to build a bigger school placement team. The management, organisation, teaching, development, assessment, monitoring and mentoring students and associated school responsibilities was overwhelming, and professionally and personally took its toll, but more than anything highlighted the lack of importance associated with school placement at a school and management level. (Reflection 1)

‘Now What’: a space to readdress school placement?

Within this ‘Now What?’ stage a number of high-level themes identify potential continuity and changes to teacher education, including the enhanced mentoring role of tutors’ and CTs, portfolio use, improved reflective practice, development of formal and informal communities of support and online assessment.

Looking beyond traditional assessment

The COVID-19 dilemma provided valuable opportunities to explore innovative assessment formats in SP in the Irish context. Mutton (Citation2020) posed the question of ‘what is likely to be the “new normal” in assessment of practicum?’ (440), and it appears that critical reflection and a validation of best judgement (Mezirow Citation2006), informed by discussions with participants, illustrates how this open question was addressed in practice. Many participants agreed that

We have developed new and meaningful ways of assessing student teachers online and identified new modes of assessment that are successful in allowing student teachers to demonstrate that they have met the learning outcomes. (Reflection 4)

This favourable outlook on adapting assessment processes contrasted with uncertainty in the change-making, similar to Shanker et al.’s findings (Citation2021), particularly as COVID-19 posed a live dilemma. Nonetheless, changes to assessment were governed, and to some extent limited, by internal HEI requirements around grading. One participant noted that ‘the greatest challenge was having to continually update and reinvent how SP was conducted as the circumstances continued to change and disimprove’ (Reflection 4). Others explained the pressure to ‘still stay within, you know, assessment guidelines and rubrics that we had previously’ (FG1).

Participants noted greater emphasis on reflective practice, increased discussion fora (including on-line mentoring), and presenting post-placement presentations as alternative modes of assessment. This was facilitated by the harnessing of technology, as occurred in education globally (Sasaki et al. Citation2020). Although this approach to grading was deemed a positive development, it is desirable that the potential of this change in assessment processes has agreement across the sector, particularly given CEIM’s (Teaching Council Citation2020b) positioning of SP at the centre of ITE programmes.

A FG1 participant valued ‘detailed accounts’ from a ‘professional portfolio’ and how students ‘weren’t having that fear of the tutor coming out’. Another noted the ‘professional conversation, focusing in on their planning, that that got such good feedback and a good response that we’re holding on to that’ (FG1) and overall confidence displayed by PSTs. Generally, the ‘acknowledgement that there are other forms of assessment that we should be exploring, and the sacrosanct, you know, visit that everything relies upon is not the ideal, necessarily model’ (FG2) was mooted. The voices of the participants above are akin to agreeing with Carrillo and Flores (Citation2020) and Hodges et al.’s (Citation2020) calls to redefine SP based on positive observations and occurrences experienced in the COVID-19 melee.

Guidance from the Department of Education and Skills (Citation2020) and the Teaching Council (Citation2020a) still left the remit of how to enact changes to the HEIs, even with the aforementioned ‘imperative’ of continuing placements (Teaching Council Citation2020aa, 2). The recent assessment-related changes are an example of how Directors or Coordinators once more make meaning from the pandemic’s upheaval.

Reflecting on Mezirow’s framework (Citation2000, 22), it seems that those involved in SP may be limited to the ‘provisional trying of new roles’ and struggle to break the boundary to Mezirow’s penultimate level of ‘building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships’. Maybe this is due to external and/or internal barriers, and a resultant lack of true recognition of the role’s importance (Fleming Citation2016). Also, whilst it becomes apparent that the participants are discursively reflecting on the strengths, challenges and opportunities as seen at the second of Mezirow’s learning process (Citation1985), the participants are embedded in a political vacuum within the final or third learning process, and effectively cannot transform the SP experience, but self-reflectively remain responsible for it.

Pass/fail grading

Adopting pass/fail grading was initiated to limit the consequences of disrupted placements due to COVID-19:

We moved our grading to Pass/Fail (on the basis that to award traditional grades would be inappropriate when we did not see students in classrooms) and this has had a largely positive outcome for both students and tutors. The student/tutor dynamic has changed as grading is less of a concern and mentoring takes centre stage. (Reflection 3)

Some participants noted the initial perceived challenges of pass/fail grading, citing tradition of having a grade and students’ future CVs as the biggest impasse to moving to pass/fail nationally:

… it’s not universally accepted, and also when it comes to recruitment, jobs and so on, until all institutions embrace the pass fail …, some institutions have percentages and some haven’t (FG2)

The national position was noted as important by multiple participants such as ‘I also agree that it would be something you’d want to see happening across the different institutions as well’ (FG2) and ‘I would keep pass/fail grading and embed it nationwide if I could’ (Reflection 2). One participant, who was involved in moving to Pass/Fail, whilst acknowledging the challenges, also noted that there were many successes attached to the development of such an approach:

Pass/fail grading afforded new mentoring focus as tutors had to change the dynamic rapidly away from any sort of lingering deficit pail-filling model mentality to one of guide and facilitator of learning. (Reflection 2)

Criterion-referenced grading was deemed important to complement pass/fail grading:

We had to move to criterion referenced grading, grading that provides students massive feedback … they also get a competence summary document, which summarises under the criteria of the placement … So we’re not just saying, you’re good, we’re saying you passed, and this is how well you passed. (FG3)

Finally, the positive effect on PSTs’ learning was evident:

We’ve seen some fantastic results, we anticipated such results. We know, looking at surface-learning versus deep-learning approaches … What we’ve seen with the move to pass fail, we’ve seen deeper, more critical reflection. We’ve seen students who’ve more confidence because they can take risks and actually see the benefit of taking those risks. (FG3)

The proposal provided in this section to move to pass/fail grading demonstrates how challenging it is to harness an adaptation that seems to yield a positive outcome, especially as transformations continue to occur within SP nationally. New meaning schemes, which were compatible with existing schemes, as per Mezirow (Citation2000), are explicitly observed here. The participants demonstrated a discovery mode of valuing the new, whilst being very aware of tradition, PSTs’ needs and workforce regulation. In some instances, the lack of agency afforded to those working in SP to adopt a Pass/Fail approach is notable, considering the work of Prosser et al. (Citation1999) on surface-learning and deep-learning approaches. Participants noted successes of an opportune experimentation phase (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison Citation2020) of Pass/Fail grading, alongside the need to move beyond such experimentation and embed new ways of working (Carrillo and Flores Citation2020).

Readdressing school placement

COVID-19 challenged assumptions and whilst it was stressful for all participants, it created opportunities for potential change and a move away from the traditional placement approach,

It is hard to believe that what began as a survival task in March 2020 became a new and possible modus operandi of blended approaches as we move ahead. Despite any pre-planning and through pure necessity there has been a transformation in how we do school placement. The interesting piece will be how we continue to do it as we move forward. (Reflection 4)

One participant recognised that SP is characterised by its ‘focus on strict requirements and regulations’ but COVID-19 put them in a space where they had no requirements and that they had to create ‘new requirements and new regulations literally overnight’ (reflection 5). As a result, all participants were ‘challenged to reconceptualise and rethink the role and associated requirements of school placement’ (survey), which aligns with Habermas (Citation1972) approach to archaeological digging up of assumptions to renew possibilities. This also resonates with Mezirow’s (Citation2000) claim that there are no fixed truths or definitive knowledge, challenging the participants to move from the norm and the set boundaries that existed within SP policies. This fluidity forced participants to negotiate their own understanding and meaning of policy enactment. It was evident in the data that this remained both a challenge and an opportunity as they were continually faced with changing circumstances.

One participant stated ‘what surprises me most is that we got through so many challenges and disorienting dilemmas, righted and reoriented ourselves and continue to learn plenty along the way’ (Reflection 4). In responding to the pandemic, changes to SP included upskilling on technology, virtual meetings, online professional dialogues, adapted online professional development for tutors, live streaming of PSTs classes, paperless documentation and the creation of online communities for both PSTs and tutors. Another significant challenge was that of training and re-training tutors to meet the needs of adapted supervision in the light of school closures.

Another participant noted ‘we did develop practices within the supervision domain which have been very positive and [hope to] retain in a hybrid approach (Reflection 3). To ensure these improvements and innovations are harnessed most participants mentioned the need for greater recognition of the role and responsibilities of those involved in SP and the need to effectively resource it,

More acknowledgment of the importance and associated time commitment of placement is required at management level, it is a fundamental part of a core activity, yet not weighted so in resourcing and supports (Survey)

Piccolo, Livers, and Tipton (Citation2021) stress that although COVID-19 has put ITE programmes in flux there is a need to ‘respond to today’s issues and tomorrow’s possibilities’ with flexibility and creativity’ (246). The COVID-19 situation demonstrated the bottoming out of perceived ‘truths’ within SP, akin to Mezirow’s contextual understanding (Citation2000). When allowed (or indeed forced) to break with tradition, new opportunities flowed in, not just assessment opportunities, but to the entire readdressing of SP in Ireland.

National context

The final theme identified was the urgent need to address the national context of SP in Ireland. Considering that the SP system in Ireland is not formally structured and remains based on the goodwill of schools, which are under no obligation to accept student teachers (Hall et al. Citation2018), COVID-19 exposed the fragility of the Irish system and put extensive pressure on school–university partnerships. The system creates an inequity of experience for PSTs:

What is needed is to formalise school university partnerships. I really think that is important going forward, I think it’s key to try and make our school placement system a more robust and fair system really, for all our students. (FG1)

COVID-19 brought significant changes to the role of CTs, particularly in the absence of tutor visits during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, PST-CT best practice was evident, although mainly undocumented, largely unrecognised and wholly inconsistent. The findings indicated many CTs took on more of a structured mentoring role, reflecting a dyadic ST-CT community characterised by observation, feedback and professional conversations as proposed by Young and MacPhail (Citation2016). A number of participants highlighted the importance of the improved support:

So the cooperating teachers had to take that role on [mentor]. We’ve never had that before, to the level that it occurs. So students were observed and given feedback on a daily or weekly basis. And the schools were fully supportive. My hope for the future is that this continues, or we can package that a bit better (FG3).

Another participant, in discussing the improved interaction with CTs, commented on the need to build on these relationships:

I think there’s something out there that needs to be harnessed. I don’t know what the answer is, but I do think this is a moment in time when everything shifted, and we could harness that for the betterment of school placement, nationally and within our institution. (FG2)

CÉIM (Teaching Council Citation2020aa) places greater emphasis on the role of the CT in supporting PSTs. Currently, recommended roles for CTs (Teaching Council Citation2013) are not formalised. Redefining these roles has the potential to transform SP and school–university partnerships. Devolving some responsibility to schools, in terms of mentoring and assessment, which is common practice internationally, will not be possible without the resourcing and support of all stakeholders. One participant, acknowledging ‘that schools don’t get enough credit for hosting placements and for the work they do’ (FG3) also reflected that traction might now be lost with schools and CTs in the absence of investment into teacher education. There is a further concern of not capitalising the extensive goodwill of CTs, particularly in the absence of in-school tutor visits. In discussing the future of SP, one participant commented

It’s [SP] at breaking point. The increased numbers of students, the increased pressure on schools who don’t have any requirements to take student teachers, the pressure the internal staff are having, and are not finding time to do visits and don’t want to do it. And then COVID has had massive impacts. And we’re seeing the fallout now. (FG3)

This is reinforced further by another participant who stated, ‘An unintended consequence of COVID-19 has been the opening up of conversations and the realisation by more stakeholders that school placement, in its current state, is not sustainable’ (reflection 1).

Participants noted the toll that the management of SP was taking, notwithstanding challenges prior to COVID-19, it has shown the fragility of the SP system in Ireland;

We’re getting so much bigger, we can’t sustain what we’re doing. And as much as this is my passion, and this what we want to do, the sustainability and the toll it’s taking is huge. And until there’s recognition from the powers that be and at a greater level, we’re going to break and the system will break’ (FG3).

The ongoing absence of a structured and formalised partnership approach to SP in Ireland continues to limit and undermine (Honneth Citation2014) the progress and opportunities presented during the pandemic. The extent of transformative learning, as elucidated by Mezirow (Citation2000), by those involved in SP, was enabled by challenging past experiences and perspectives and creating new meanings for SP, particularly around the importance of school–university partnerships and the mentoring capabilities of CTs.

Learning from COVID-19: making meaning and more dilemmas?

Notwithstanding the stress, panic and fear generated by COVID-19, various possibilities and opportunities were created. The challenge now lies with teacher education to enact and harness the positive practices emerging during the pandemic. This is reinforced by Farrell (Citation2021) who emphasises that ‘this time of disruption has generated a chance for rethinking and reinventing the school-university nexus in ITE in Ireland’ (165).

The disruption caused by COVID-19 is a global phenomenon, is ubiquitous and both a common factor and a catalyst for new waves of research on the impact of the pandemic on ITE. This has enabled the research team to make some meaning from the lived experience of the pandemic, which included a number of disorienting dilemmas at different points along the way in the ongoing cycle of adapting, coping and continuing. The lived experience has posed multiple questions and dilemmas still present. The research evidences transformative learning in how our assumptions have changed and how we act on those assumptions is also different;

It kind of relates back to the way Mezirow was challenging our own assumptions and presumptions, that it has to be a particular way. Because when COVID came, it couldn’t be that way. It had to be different. And we had to think about it or conceptualise it differently. (FG3)

Fleming (Citation2016) reports that Mezirow always insisted that learning had not occurred or indeed the transformation had not been complete until one acted on the basis of the new set of assumptions. The final excerpt below captures the essence of transformative learning and its potential for change;

That’s what transformation and the transformative learning piece is and … as educators we sometimes forget, we’re also learners., we learn about ourselves and we learned about other people. And we learn about what is important and what isn’t important. (FG3)

The pandemic continues, and therefore we continue to encounter disorienting dilemmas. Reflecting on our experiences and challenging our assumptions guided by Mezirow’s theory (Citation1978), we have initiated changes at institutional levels, though recognise the need for these to be discussed and considered at a system-wide level. New modes of meaning and understanding provide an opportunity to consolidate some of the concrete actions explored during this upheaval in school placement. These include: development of further structured communications with schools, use of electronic filing, presentation of materials, online mentoring meetings and alternative grading processes. Significantly, in the Irish context, the cooperating teacher’s more frequent and meaningful involvement in placement conversations and in-school support embodies the engagement espoused by the Teaching Council (Citation2020). These aspects of placement may afford pathways for future developments for school placement in Ireland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barbour, R. 2008. Doing Focus Groups. London: Sage.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2020. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Brookfield, S. D. 2017. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Caillaud, S., and U. Flick. 2017. “Focus Groups in Triangulation Contexts.” In A New Era in Focus Group Research: Challenges, Innovation and Practice, edited by R.S. Barbour and D.L. Morgan, 155–177. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-58614-8.

- Carrillo, C., and M.A. Flores. 2020. “COVID-19 and Teacher Education: A Literature Review of Online Teaching and Learning Practices.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 466–487. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184.

- Clarke, L, and T O'Doherty. 2021. “The Professional Place of Teachers on the Island of Ireland: Truth Flourishes Where the Student's Lamp Has Shone.” European Journal of Teacher Education 44 (1): 62–79. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1844660.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2020. “Reopening Our Schools: The Roadmap for the Full Return to School.” July 26. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/b264b-roadmap-for-the-full-return-to-school/

- Drake, P., and L. Heath. 2008. “Insider Research in Schools and Universities: The Case of the Professional Doctorate.” In Researching Education from the Inside. Investigations from Within, edited by P. Sikes and A. Potts, 127–143. London: Routledge.

- Farrell, R. 2021. “Covid-19 as a Catalyst for Sustainable Change: The Rise of Democratic Pedagogical Partnership in Initial Teacher Education in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 161–167. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1910976.

- Fleming, T. 2016. “Toward a Living Theory of Transformative Learning: Going beyond Mezirow and Habermas to Honneth.” This is the text of the 1st Mezirow Memorial Lecture at Columbia University Teachers College sponsored by AEGIS IXX, the Department of Organization and Leadership and the Office of Alumni Relations at Teachers College, New York.

- Flores, M., and M. Gago. 2020. “Teacher Education in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic in Portugal: National, Institutional and Pedagogical Responses.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4): 507–516. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1799709.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herter and Herter.

- Habermas, J. 1971. Knowledge of Human Interests. Boston: Beacon.

- Habermas, J. 1972. Knowledge and Human Interests. Boston: Beacon.

- Habermas, J. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society T. McCarthy, Trans. Boston: Beacon.

- Hall, K., R. Murphy, V Rutherford, and B. Ní Áingléis. 2018. School Placement in Initial Teacher Education. Dublin: Irish Teaching Council.

- Harford, J., and T. O’Doherty. 2016. “The Discourse of Partnership and the Reality of Reform: Interrogating the Recent Reform Agenda at Initial Teacher Education and Induction Levels in Ireland.” Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 6 (3): 37–58. doi:10.26529/cepsj.64.

- Harford, J. 2021. “All Changed: Changed Utterly’: Covid19 and Education.” International Journal for the Historiography of Education 11: 55–81 .

- Harris, A, and M Jones. 2020. “COVID-19 - School Leadership in Disruptive Times.” School Leadership & Management 40 (4): 243–247. doi:10.1080/13632434.1811479.

- Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust, and A. Bond. 2020. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Retrieved from Educause: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Honneth, A. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Honneth, A. 2014. Freedom’s Right: The Social Foundations of Democratic Life. Cambridge: Polity.

- Johns, C. 2017. Becoming a Reflective Practitioner. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kalloo, R. C., B. Mitchell, and V.J. Kamalodeen. 2020. “Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Trinidad and Tobago: Challenges and Opportunities for Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4): 452–462. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1800407.

- Kennedy, A., L. Hay, and B. McGovern. 2020. “A Story of Transforming Teacher Education.” Scottish Educational Review 52 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1163/27730840-05201003.

- Kitchenham, A. 2008. “The Evolution of John Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory.” Journal of Transformative Education 6 (2): 104–123. doi:10.1177/1541344608322678.

- Kuhn, T. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Liston, J., M. Ní Dhuinn, M. Prendergast, and T. Kaur. 2021. “Exploring Reflective Practice in an Initial Teacher Education Program in Ireland.” In Recruiting and Educating the Best Teachers: Policy, Professionalism and Pedagogy, 226–246. Netherlands: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004506657_01310.1163/9789004506657_013.

- Lynch, R., and P. Mannix Macnamara. 2014. “Teacher Internship in Ireland.” In Practical Knowledge in Teacher Education: Approaches to Teacher Internship, edited by J. Calvo de Mora and K. Wood, 128–142. London: Routledge.

- Mezirow, J. 1978. “Perspective Transformation.” Adult Education 28 (2): 100–110. doi:10.1177/074171367802800202.

- Mezirow, J. 1985. “A Critical Theory of Self-directed Learning.” In Self-directed Learning: From Theory to Practice (New Directions for Continuing Education, edited by S. Brookfield. Vol. 25, pp. 17–30. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions in Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 1994. “Understanding Transformation Theory.” Adult Education Quarterly 44 (4): 222–232. doi:10.1177/074171369404400403.

- Mezirow, J. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 2006. “An Overview of Transformative Learning.” In Lifelong Learning: Concepts and Contexts, edited by P. Sutherland and J. Crowther, 24–38. New York: Routledge.

- Mutton, T. 2020. “Teacher Education and Covid-19: Responses and Opportunities for New Pedagogical Initiatives.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4): 439–441. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1805189.

- Piccolo, D.L, S.D. Livers, and S.L. Tipton. 2021. “Adapting Student Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison of Perspectives and Experiences.” The Teacher Educator 1–20. doi:10.1080/08878730.2021.1925382.

- Prosser, M, and K Trigwell. 1999. Understanding Learning and Teaching: The Experience in Higher Education. UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Rolfe, G., D. Freshwater, and M. Jasper. 2001. Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions: A User’s Guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Rolfe, G. 2002. “Reflective Practice: Where Now?” Nurse Education in Practice 2 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1054/nepr.2002.0047.

- Sasaki, R., W. Goff, A. Dowsett, D. Paroissien, J. Matthies, C. Di Iorio, S. Montey, S. Rowe, and G. Puddy. 2020. “The Practicum Experience during Covid-19–Supporting Pre-Service Teachers Practicum Experience through a Simulated Classroom.” Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 28 (2): 329–339.

- Sepulveda-Escobar, P., and A. Morrison. 2020. “Online Teaching Placement during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chile: Challenges and Opportunities.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 587–607. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1820981.

- Shankar, K., D. Phelan, V. Ratnadeep Suri, R. Watermeyer, C. Knight, and T. Crick. 2021. “The COVID-19 Crisis Is Not the Core Problem’: Experiences, Challenges, and Concerns of Irish Academia during the Pandemic.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 169–175. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1932550.

- Sikes, P.J, and A Potts. 2008. Researching Education from the Inside: Investigations from Within. London; New York: Routledge.

- Teaching Council. 2013. Guidelines on School Placement. Maynooth: Teaching Council.

- Teaching Council. 2020. “Guidance Note for School Placement 2020/2021”. 10th August. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/News-Events/Latest-News/10-08-2020-Guidance-Note-for-School-Placement-2020_.pdf

- Teaching Council. 2020a. Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education. Maynooth: Teaching Council.

- Uí Choistealbha, J., M Ní Dhuinn, T Kaur, and S.A. Garland. 2021. “DEEPEN, Droichead: Exploring and Eliciting Perspectives, Experiences and Narratives.” Final Report submitted to Teaching Council, October.

- White, I., and M. McSharry. 2021. “Preservice Teachers’ Experiences of Pandemic Related School Closures: Anti-structure, Liminality and Communitas.” Irish Educational Studies 1–9. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916562.

- Young, A.M., and A MacPhail. 2016. “Cultivating Relationships with School Placement Stakeholders: The Perspective of the Cooperating Teacher.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1187595.