ABSTRACT

The following paper aims to investigate how student teachers relate to the suitability of their student teacher peers after experiencing challenges to their emerging teacher identity, resulting in emotional responses. A constructivist grounded theory study was conducted in which 18 student teachers participated. Data from 14 individual interviews and one focus group were analysed. Findings revealed that encounters between student teachers sometimes resulted in emotional responses. When the student teachers were emotionally challenged by their peers, their emerging teacher identity was challenged. In addition, the student teachers compared themselves with those peers whom they judged as unsuitable and constructed a self-image of being suitable. This comparative process was connected to three suitability norms: (1) being perceived as having the right values (2) being perceived as having social skills and (3) being perceived as committed to in-depth learning as a teacher.

Introduction

There is a common deficit model of thought on student teachers in Sweden. For example, there has been a recurrent negative debate and criticism in Swedish media in relation to teacher education and student teachers regarding low standards, deficiencies, and unsuitability (Edling and Liljestrand Citation2020). Kelchtermans (Citation2019) discusses a dominant discourse characterised by deficit thinking on how newly qualified teachers lack specific competencies and therefore need individual help to compensate for their individual shortcomings, positioning newly qualified teachers as ‘formally qualified but not yet fully capable’ (Kelchtermans Citation2019, 86). Swedish teacher education was previously more competitive and selective, but during the last decades the teaching profession has decreased in attraction and status, resulting in fewer applicants (OECD Citation2015). The OECD concluded that it would be better if Swedish teacher education were to return to a more selective admission process to increase the status of the teaching profession.

Here, several important issues of suitability interconnect. There is a shortage of teachers, which means that there is a need for more people to be trained as teachers. Although there is a need for a large number of people to complete teacher education in Sweden, many of the applicants who start teacher education never graduate (Sveriges Radio Citation2019). Moreover, the admission of applicants to teacher education who subsequently fail to complete the programme triggers discussion among student teachers of what makes a person suited for a career in teaching. There is a tension between getting enough teachers and retaining them and also improving quality in schools.

This study stems from a larger project investigating emotionally challenging episodes during teacher education (Lindqvist Citation2019; Lindqvist et al. Citation2017, Citation2020). One of the recurrent patterns we found in focus groups and interviews in the project was that student teachers were emotionally challenged by peers they deemed unfit for the teaching profession. Therefore, this recurrent pattern has been further explored and analysed in this study. This study aims to investigate which characteristics are considered by student teachers to be necessary for a person to be suitable for a future teaching career, and how deviation from this norm challenges their emerging teacher identity. This is investigated using the following research questions: (1) What do student teachers perceive as being emotionally challenging in their contact with fellow student teachers? (2) How do student teachers interpret their peers as triggering challenges to their emerging teacher identity? (3) How do student teachers interpret themselves in terms of their suitability for a career in teaching?

Challenges to emerging teacher identities

Student teachers have reported encountering challenges during teacher education (Deng et al. Citation2018; Hong Citation2010; Kokkinos, Stavropoulos, and Davazoglou Citation2016) that also influence their emerging teacher identities (Yuan and Lee Citation2015). Yuan and Lee (Citation2015) showed that the student teachers’ teacher identities were formed through contacts during field work, with mentoring teachers and student teacher peers. When an emerging teacher identity is forming during teacher education, the experience can include emotional ups and downs (Timoštšuk and Ugaste Citation2010; Yuan and Lee Citation2016) and student teachers report experiences of emotional flux (Teng Citation2017). Teacher identity has previously been depicted as being fluid, dynamic and multi-faceted (Beijard, Meijer, and Verloop, Citation2004). Chen, Sun, and Jia (Citation2022) describe teacher identity and emotions as reciprocal and dependent on how student teachers appraise events and situations in relation to their goals, and this determines the intensity of their emotional response. In addition, Nichols et al. (Citation2016, p. 2) state that ‘teachers’ emerging identities not only influence their actions and emotions, but their actions and emotions influence their identity formation”.

A crucial challenge of student teachers is the dissonance between ideals and reality, and the emotional response this could result in (Sumsion Citation1998). Student teachers have beliefs about the role they will play in students’ lives. When their beliefs are challenged or compromised, this will affect their development of a teacher identity. How student teachers cope with challenging situations and the influence of negative emotions on identity is therefore crucial (Yuan & Lee, Citation2016). In addition, there are unspoken rules in teaching about what emotions are suitable (i.e. encompassing rationalist, calm and balanced features). For example, anger is usually not considered favourable in teaching, whereas caring is (Isenbarger and Zembylas Citation2006). Student teachers encounter these unspoken rules during their teaching practice. Emotional challenges are understood as relationships, situations, and interactions that student teachers perceive as distressful or unpleasant, and therefore necessary to cope with, that also influence student teachers’ emerging identity. Hadar et al. (Citation2020) describe student teachers’ need to be prepared for a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world. In their study, student teachers struggle with the uncertain conditions, and do not seem to receive enough preparation in social-emotional competencies.

Lassila et al. (Citation2017) found occasions of laughter, silence, or humour in interactions within peer groups as a response to emotionally loaded stories from their peers in teacher education. In these cases, student teachers seemed to avoid deep emotional reflection altogether (Lassila et al. Citation2017). In addition, Väisänen et al. (Citation2017) reported that student teachers rarely offer support to other student teachers. As far as we know there is no other research that examines how student teachers reflect on and judge their peers’ suitability when discussing emotionally challenging episodes. Given the rationale that teaching is not for everyone (Sirotnik Citation1990), student teachers encounter suitability norms triggered by emotional challenges related to their peers. In teacher education, student teacher peer groups have been discussed as important for coping with challenging emotions and facilitating self-regulation and social support (Karlsson Citation2013; Lindqvist Citation2019). Yuan and Lee (Citation2015) show how student teachers have peer support to overcome emotional challenges arising from teaching practice. In contrast, there is also research showing that peer-group learning might also trigger emotionally challenging episodes (Väisänen et al. Citation2017) and further consolidate suitability norms, and influence student teachers’ emerging teacher identity.

Suitability norms in teacher education

Suitability refers to ideas about having the ‘right’ values, attitudes, personality, and skills needed to fit into the teaching profession (cf. Kelchtermans Citation2019). It is connected to emotional challenges (Holappa et al. Citation2021) and therefore also influences student teachers’ emerging teacher identity.

Issues of suitability are relevant for teacher education, since the social comparative and contrasting process among student teachers might help create norms, adding to a deficit model of student teachers, and future newly qualified teachers. In teacher education programmes, norms are created, and social comparative processes are at work that are challenging for the emerging teacher identity, resulting in emotional responses. For example, how student teachers express vulnerability might be inhibited by norms regarding suitable teacher characteristics (Holappa et al. Citation2021). A Finnish study on student teachers’ perspectives on their teacher education found that student teachers created their own definition of suitable teacher characteristics, since there was a lack of criteria as to what constituted a suitable or ‘good’ teacher. The characteristics that student teachers tended to use to define the suitable, ‘good’ teacher included empathy, reflectivity, sociability, self-confidence, predominant positive mood, determination, and being active (Lanas and Kelchtermans Citation2015).

The concept of suitability for a career in teaching influences how student teachers think about themselves and others: ‘what “kind of person” one is recognised as “being”, at a given time and place, can change from moment to moment in the interaction, can change from context to context, and, of course, can be ambiguous or unstable’ (Gee Citation2000, 99). It would therefore appear to be important to explore how student teachers interpret and value their peers and themselves in emotionally challenging episodes (cf. Holappa et al. Citation2021), and what they consider to be suitable conduct for future teachers while in teacher education. Holappa et al. (Citation2021) conclude that dealing with emotions around unsuitability needs to be a part of teacher education. Even so, how suitability norms are constructed and result in challenges to emerging teacher identities that evoke emotional responses among student teachers is not previously described in the literature. We add the perspectives of student teachers that experience challenges when experiencing challenges to the prevailing and majority suitability norms, as a part of their emerging teacher identity.

Method

We adopted a constructivist grounded theory approach, since it is designed to openly and systematically explore people’s perspectives and voices in how they interpret and understand social processes, shared meaning and interaction (Charmaz Citation2014). This is suitable because our interest in how student teachers socially represented emerging teacher identities are challenged. We navigated close to data and sought to stay true to the participants’ perspectives and their empirical world (Charmaz Citation2014). The constructivist version of grounded theory views actions as interpretations that form the social world of which people are a part. In line with a constructivist version of grounded theory, we view the researchers as co-constructors in the process of gathering and analysing the data (Charmaz Citation2014).

Participants and data collection

This study stems from a larger research project, in which a total of 67 student teachers from six Swedish universities participated. Our previous analyses of the qualitative data (based on individual interviews and focus groups) have focused on emotional challenges and coping strategies among student teachers. However, during the analyses we found that in some of the interviews the participants recurrently and spontaneously discussed their encounters with peers as emotionally challenging, resulting in discussions of their peers’ (un)suitability for a career in teaching. Therefore, guided by theoretical sampling (Glaser Citation1978), for the current study we selected 15 of the interviews, including a focus group interview, for further analysis. We started the analyses by going through the entire dataset to find the interviews in which student teachers discussed and judged the suitability of their peers and presented this as emotionally challenging. Grounded theory methods were used to analyse the data (Charmaz Citation2014). The included interviews and focus group data were gathered from a total of 18 participants. See for participant demographics.

Table 1. Participants.

Teacher education lasts from three-and-a half to five years, depending on the age group that will be taught. In teacher education there is a period of teaching practice at a school. The teaching practice is up to 20 weeks spread throughout teacher education. The student teachers usually change schools for teacher practice and come to meet different supervisors who also assess and value their performance. In Sweden, teachers and other school staff are not only expected to but must embrace, express and stand for democratic values and human rights, according to national curriculum and school policy documents (Skolverket Citation2018).

The student teachers in the current study were in their last year of teacher education and were scheduled to start working as teachers within a year. In total, 14 individual interviews (of which nine were conducted face-to-face and six using a video conferencing tool) and one focus group interview were analysed. The focus group interview was done face-to-face and included four participants. The focus group interview lasted 79 minutes and the individual interviews ranged from 31 to 96 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. The names used in the findings are pseudonyms.

The interview questions focused on emotionally challenging situations in teacher education that the student teachers had been exposed to. When the student teachers described their peers as the source of emotional challenges, follow-up questions were used to elicit more information about their perspectives of peers as creating emotional challenges. This means that all participants in the study stated that their peers created emotional challenges to their emerging teacher identity, triggering the evaluation of suitability. The participants evaluated the other student teachers based on work on courses, but also from spending time together in other situations, such as time between classes and in group work.

Data analysis

In line with a constructivist grounded theory methodology approach, initial, focused, and theoretical coding were used. Initial coding was carried out word by word, sentence by sentence and segment by segment (Charmaz Citation2014). During focused coding, the most significant and common initial codes were used to further guide the analysis. The codes generated in this phase were more selective and conceptual than the initial codes. Examples of these codes are shown in

Table 2. Examples of codes.

Almost simultaneously with focused coding, theoretical coding was performed. In theoretical coding, we explored and analysed the relationships between our empirical codes using theoretical codes of dimensions (Glaser Citation1978). Constant comparisons within and between data and codes were made in each coding phase. Memos were written, compared, sorted and further elaborated to try out theoretical ideas, understandings and models (Charmaz Citation2014). We used principles of theoretical agnosticism and pluralism as guiding principles in the analysis in line with informed grounded theory (Thornberg Citation2012).

Ethical considerations

The study was granted ethical approval by the Regional Ethical Board in Stockholm . The student teachers participating in the interviews were informed as to how the data was to be used within the project. In addition, they were informed about their rights as participants before data collection, that their participation was voluntarily, and that their confidentiality would be secured by using assumed names.

Findings

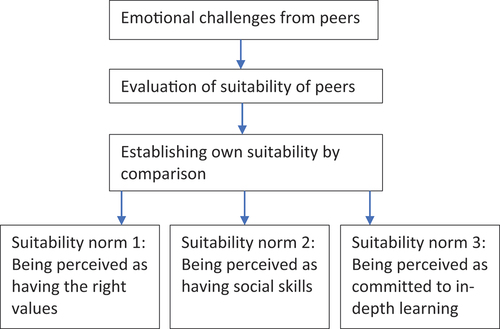

The study’s point of departure was that the student teachers recurrently reported being emotionally challenged by student teacher peers. Their experiences of peers, whom they perceived as unsuitable, evoked emotional distress by challenging their emerging professional identity. From their point of view, these peers are going to devaluate the whole teaching profession and give it a bad reputation. During the teacher training, the student teachers encountered unwritten rules of the teaching profession (i.e. suitability norms) that further complicated their understanding of the social world of teaching. They described emotionally challenging episodes in relation to being forced to interact and work with what they perceived as unsuitable student teachers, as well as from spending time together in other situations, such as time between classes and in group work. In addition, the student teachers compared themselves with those peers whom they judged as unsuitable and constructed their emerging contrasted teacher identity as suitable. This involved portraying what the breach of the norm is, as experienced by the student teachers, and does not represent an objective fact of how their student teachers’ peers were. Rather, constructing an emerging teacher identity as suitable included an interpretative and comparative process that was connected to three suitability norms: (1) being perceived as having the right values (2) having social skills and (3) being committed to in-depth learning as a teacher (see

Figure 1. Establishing suitability norms among student teachers when emotionally challenged by peers.

Suitability norm 1: being perceived as having the right values

The student teachers in the current study stated that student teachers need ‘the right values’ to be suitable for teaching, and that encountering peers who did not fit their suitability norm was experienced as challenging their emerging teacher identity. This included wishing not to engage with peers that they found unsuitable. This idea could also be interpreted as paradoxical to the inclusive ideals portrayed as necessary.

Even though we are there on the same terms and everything, you wonder if all people in teacher education really are suitable to be teachers in the future. You judge your friends, actually. When people express homophobic, transphobic values, for example, you might think that this person should not be working at a school.

The perception of suitable values was based on an interpretation process in which personal convictions, values and experiences, as well as experienced expectations from teacher education, seemed to play an important role. Lena described her interactions with other student teachers, who expressed opinions that challenged and transgressed democratic values and human rights, as challenging her emerging teacher identity.

When your future colleague expresses things that you consider to be racist, or homophobic, that is very emotionally challenging. There are no measures, no admission test to show that you have democratic values when entering teacher education. But that’s something I find extremely important and am passionate about. Even if you tell them they are wrong and they don’t change, they will still become teachers.

In addition, Lena had a hard time accepting that student teachers she assessed as racists would be allowed to teach children. In this interpretation process the student teachers judged their peers as suitable or not, based on whether they expressed values that were considered to be right or not. By this social comparative and contrasting process, student teachers could then construct and judge themselves and their emerging teacher identity as suitable in terms of having the right values to become a teacher.

Suitability norm 2: being perceived as having social skills

Student teachers considered social skills to be a requirement for a teacher. It was considered as indispensable to be able to talk in front of a group and establish relations with pupils. Peers who student teachers perceived to lack social skills during teacher education were judged as unsuitable, and created tensions in the notion of a preferable teacher identity.

They don’t have the social ability at all, and I think that’s a bit tragic – to have come this far in teacher education and they will never get a job but have high student loans. I don’t really worry about them, but more, like, imagine the pupils they will meet, how will that turn out?

According to student teachers, social skills could to a certain extent make up for poor subject knowledge; however, having subject knowledge did not make up for poor social skills. To be professional, teachers were considered to need communication skills and to respect all pupils, even those who challenge them. Jörgen argued that a professional teacher must know how to interact and communicate with the age group of pupils they teach.

Jörgen: Well, partly, but it’s mostly social, I have to say.

Interviewer: How?

Jörgen: A lot of times when supervisors have two from the same class and then you see how the children look at them like questions marks. They don’t know how to act towards the children, or they can’t relate to their level and talk to them at their level. Instead, it’s a grown-up talking to a child, and the language is totally different, and the children don’t understand and the [student] teacher doesn’t understand what the children mean, and it’s really weird just from that. When you can’t communicate and can’t create relationships (Jörgen, grades F–3).

In the interpretation process of judging peers as suitable or not, student teachers could compare themselves with those who they perceived as poorly socially skilled. Through this comparison they judged themselves to be high in suitability for a career in teaching by referring to their own perceived good social skills, as a part of their emerging teacher identity, and the unwritten rules of teaching.

Suitability norm 3: being perceived as committed to in-depth learning as a teacher

Student teachers argued that they and their peers needed to be engaged in teacher education to acquire essential knowledge and fulfil the requirements. They experienced frustration and challenges to their identity formation as a result of interacting with student teachers who acted differently. The degree to which peers displayed a commitment to in-depth learning was essential.

Celia: In course evaluations, someone could claim not to have understood the difference between, well during the Reformation, Catholicism, and Protestantism. And that feels like, if you didn’t know that beforehand, and didn’t know the terms, and if you don’t know now after, how did you pass the course and what will you teach children in your class? Sometimes you wish for higher demands in the education system.

Interviewer: Higher demands concerning?

Celia: Well, knowledge demands, in a way (Celia, grades 4–6).

Celia doubted certain peers, whom she perceived were poorly engaged in their academic studies. She blamed the peers for not studying enough but also teacher education for having low demands and requirements. In addition, Beth had experiences of poor group discussions and group work in her class:

Well, there is no discussion in class. It’s like, ‘what do you think about this?’ when you have presented something; you get no response. Or when you sit in a group and work with the task, it can be like some people don’t participate. The discussions are not very fruitful.

Mia and Kajsa discussed low academic engagement among their peers, including free riders and those who were unprepared for their campus-based lessons and seminars. They discussed this as creating a negative peer effect that challenged their idea of how a future teacher should act.

Mia: But of course, there’s a reason that you were supposed to read what you’re supposed to read. You might not have read in depth, but you …

Kajsa: Skim at least.

Mia: There is frustration when you get there and feel, ‘No I’m not getting anything back. I might as well have stayed home and done something else’. Then enormous frustration emerges. And that, I feel, I have felt a lot in teacher education, that a lot of people have got away with not doing much for three years (Focus group, grades 7–9).

Thus, their experiences of having peers in their class who were academically unmotivated and disengaged meant that the reported perception was that the whole quality of their teacher education was lowered by academically disengaged peers. Tom described experiencing challenges to his emerging teacher identity, when he thought about how low-achieving peers would work as teachers in the future.

Tom: It’s a bit frightening that they will work as teachers later because it’s an occupation where you have to be well-read about everything and to perform all the time. I think one should know that when applying for teacher education. Because this feels as if it’s the wrong place to be lazy.

Interviewer: Frightening, how do you mean?

Tom: No, well, if I had a child and got some of my peers as their teacher, I would change school or class immediately (Tom, grades 4–6).

Tom took it further by expressing that lazy student teachers were not suitable to teach his future child, insinuating that some student teachers were unfit to teach at all. This exemplifies the ideal teacher as committed to life-long learning, as well as always engaging in the potentially exhaustive enterprise of always knowing everything for their pupils.

Conclusions

A shared experience among the student teachers in the current study was that they were forced to interact with student teachers they perceived as unsuitable in course work and could not entirely ignore that this challenged their identity development. The emotional response was also influenced by their appraisal of suitable actions related to ideal teacher identities. The main concern of the student teachers was making sense of the identity challenges they experienced meeting student teachers whom they perceived to be unsuitable. These experiences also played a crucial role in their interpretation process for establishing professional ideals and their own teacher identity, their conception of suitability for a career in teaching, and their evaluation of their own suitability for a career in teaching. Thus, student teachers were engaged in an interpretative and social comparative process of judging the suitability of both their peers and themselves for teaching because of the emotional challenge this involved. This also exemplifies the two key identity development processes present in the data: (1) the reciprocal relationship between emotions and identity development, and (2) the unwritten rules of teaching as portrayed through suitability norms.

In the interpretation process of judging peers’ suitability for teaching, student teachers were engaged in developing their own teacher identity, including self-evaluation of their own suitability through social comparisons.

Discussion

The current qualitative findings illustrate a sample of student teachers’ emotional responses to challenges to the emerging teacher identity (cf. Chen, Sun, and Jia Citation2022). This included how they reflected upon and judged their peers and themselves. The study contributes to the international literature on student teachers’ suitability, student teachers’ interactions, emotions, and experiences during their teacher education (e.g. Holappa et al. Citation2021; Lassila et al. Citation2017), and their perspectives on teacher ideals and professional competence (e.g. Lanas and Kelchtermans Citation2015). For example, our findings add insight into emotional aspects of teacher education because challenges regarding identity positions were created in meeting peers who were determined unfit to teach. There are several aspects of personal convictions and necessary personal traits, seen as individual deficiencies to overcome, that connect to having teaching as a calling. In a study by Bennett et al. (Citation2013), experienced teachers report having a spiritual and personal calling to teach that enabled their longevity in teaching, and as such having a calling is portrayed as a necessary personal motivation for teachers. This relates to being suitable, being perceived as having the right values, having acceptable social skills and being committed to in-depth learning.

The negative debate and criticism in Swedish media concerning teacher education and student teachers in terms of low standards, deficiencies, and unsuitability (Edling and Liljestrand Citation2020) can be considered as a threat towards student teachers’ identity. This also illustrates the unstable nature of identity (Gee Citation2000). The deficit model of thinking concludes that newly qualified teachers need individual help to compensate for individual shortcomings (Kelchtermans Citation2019), and illustrates the need to consider suitability norms from an international perspective. This means suitability norms are relevant as teacher education establishes suitability norms, according to their social context, which influences the unstable nature of identity (Gee Citation2000). This study corroborates the potential risks of peer learning as discussed by Väisänen et al. (Citation2017), even though we also acknowledge the fact that peer learning is essential in all education. However, our study points to risks of the deficit model of thinking (cf. Kelchtermans Citation2019), and how this is reproduced among student teachers. There are groups of student teachers who are supportive of each other, but the support is based on how members are valued by the group.

When student teachers judge how their peers perform in teacher education, they also evaluate their peers’ commitment, how much they participate in activities, prepare, and contribute. Suitability norms such as empathy, reflectiveness, sociability, self-confidence, determination, and activity were also defined by student teachers in the study by Lanas and Kelchtermans (Citation2015) and are partly expressed by the student teachers of this study.

We agree with Holappa et al. (Citation2021), who state that dealing with emotions around unsuitability needs to be a part of teacher education. We suggest that teacher education offers student teachers opportunities to disseminate their beliefs about suitability. A practical application of the study would be to use its findings to discuss the envisioned practice among student teachers given the complex settings, including the different teachers, pupils, and caregivers with whom they will interact as future teachers. Farrell (Citation2022) show how journal writing and joint reflection can help articulate experienced negative emotions. Another implication from the study could be to focus on the discussions on teacher education courses, finding a disposition that could foster and nurture communication. One suggestion might be to use a set disposition to enable student teachers to evaluate and alter their teaching methods, focusing on student-active forms of education. For example, simulations with avatars could be used to develop communication with pupils and social skills. Samuelsson, Samuelsson, and Thorsten (Citation2022) showed that student teachers describe enhanced efficacy beliefs related to teaching after practising in a simulation with avatars, significantly higher than student teachers practising with peers in role play. This could also further engage the discussions about what skills and attributes could be developed through training, foster engagement for in-depth learning. In addition, practising role play in teacher teams has the potential to enhance student teachers’ ability to reduce colleagues’ misconduct (Shapira-Lishchinsky Citation2013). The student teacher establishes these necessary suitability norms as something inherent in teachers, and something you either have or don’t have. In teacher education, becoming a teacher is central, as the educational programme focuses on changes in the emerging teacher identity (Flores and Day Citation2006). Here using these suitability norms and emotional experiences as a starting point could help to expand notions of teacher identity (also exemplified by Golombek and Doran Citation2014).

Therefore, there seem to be ways to practise, and thus it is possible to deepen the ways teacher education provides nurture and practice to go beyond personal convictions and existing personal traits and to foster development among student teachers. Consequently, this might lessen experiences of working with peers as emotionally challenging to emerging teacher identities.

Limitations

Some limitations should be considered and evaluated when reading the findings of the study. Firstly, the analysis is based on interview data and contains no performative data. The participants may have portrayed an idealised narrative of themselves. Even if this is true, the participants also discussed their weaknesses, worries, self-doubts, and their future in teaching. Our contribution should be considered as an interpretative portrayal and does not assume to present a universal truth or a complete picture of the phenomenon (Charmaz Citation2014). Secondly, suitability was spontaneously discussed in 15 interviews. It was not discussed in other interviews that made up the entire dataset of the research project. In future research, suitability norms could be further investigated qualitatively with another sample of participants. This would increase our insight into the emotional challenges to student teachers’ emerging teacher identity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beijaard, D., P. C. Meijer, and N. Verloop. 2004. “Reconsidering Research on Teachers’ Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (2): 107–128. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

- Bennett, S. V., J. J. Brown Jr, A. Kirby-Smith, and B. Severson. 2013. “Influences of the Heart: Novice and Experienced Teachers Remaining in the Field.” Teacher Development 17 (4): 562–576. doi:10.1080/13664530.2013.849613.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Chen, Z., Y. Sun, and Z. Jia. 2022. “A Study of Student-Teachers’ Emotional Experiences and Their Development of Professional Identities.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810146.

- Deng, L., G. Zhu, G. Li, Z. Xu, A. Rutter, and H. Rivera. 2018. “Student Teachers’ Emotions, Dilemmas, and Professional Identity Formation Amid the Teaching Practicums.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 27: 441–453. doi:10.1007/s40299-018-0404-3.

- Edling, S., and J. Liljestrand. 2020. “Let’s Talk About Teacher Education! Analysing the Media Debates in 2016-2017 on Teacher Education Using Sweden as a Case.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 48 (3): 251–266. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2019.1631255.

- Farrell, T. S. 2022. “I Felt a Sense of Panic, Disorientation and Frustration All at the Same Time: The Important Role of Emotions in Reflective Practice.” Reflective Practice 23 (3): 382–393. doi:10.1080/14623943.2022.2038125.

- Flores, M. A., and C. Day. 2006. “Contexts Which Shape and Reshape New Teachers’ Identities: A Multi-Perspective Study.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (2): 219–232. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002.

- Gee, J. P. 2000. “Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education.” Review of Research in Education 25 (1): 99–125. doi:10.3102/0091732X025001099.

- Glaser, B. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

- Golombek, P., and M. Doran. 2014. “Unifying Cognition, Emotion, and Activity in Language Teacher Professional Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 39: 102–111. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.01.002.

- Hadar, L. L., O. Ergas, B. Alpert, and T. Ariav. 2020. “Rethinking Teacher Education in a VUCA World: Student Teachers’ Social-Emotional Competencies During the Covid-19 Crisis.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 573–586. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1807513.

- Holappa, A., E. T. Lassila, S. Lutovac, and M. Uitto. 2021. “Vulnerability as an Emotional Dimension in Student Teachers’ Narrative Identities Told with Self-Portraits.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 66 (5): 893–906. doi:10.1080/00313831.2021.1939144.

- Hong, J. Y. 2010. “Pre-Service and Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity and Its Relation to Dropping Out of the Profession.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1530–1543. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.003.

- Isenbarger, L., and M. Zembylas. 2006. “The Emotional Labour of Caring in Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (1): 120–134. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.002.

- Karlsson, M. 2013. “Emotional Identification with Teacher Identities in Student Teachers’ Narrative Interaction.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (2): 133–146. doi:10.1080/02619768.2012.686994.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2019. “Early Career Teachers and Their Need for Support: Thinking Again.” In Attracting and Keeping the Best Teachers, edited by A. Sullivan, B. Johnson, and M. Simons, 83–98. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Kokkinos, C. M., G. Stavropoulos, and A. Davazoglou. 2016. “Development of an Instrument Measuring Student Teachers’ Perceived Stressors About the Practicum.” Teacher Development 20 (2): 275–293. doi:10.1080/13664530.2015.1124139.

- Lanas, M., and G. Kelchtermans. 2015. “This Has More to Do with Who I Am Than with My Skills: Student Teacher Subjectification in Finnish Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 47: 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.002.

- Lassila, E. T., K. Jokikokko, M. Uitto, and E. Estola. 2017. “The Challenges to Discussing Emotionally Loaded Stories in Finnish Teacher Education.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (3): 379–393. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1315401.

- Lindqvist, H. 2019. “Strategies to Cope with Emotionally Challenging Situations in Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (5): 540–552. doi:10.1080/02607476.2019.1674565.

- Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg. 2017. “Resolving Feelings of Professional Inadequacy: Student Teachers’ Coping with Distressful Situations.” Teaching and Teacher Education 64: 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019.

- Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg. 2020. “Talk of Teacher Burnout Among Student Teachers.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 65 (7): 1266–1278. doi:10.1080/00313831.2020.1816576.

- Nichols, S. L., P. A. Schutz, K. Rodgers, and K. Bilica. 2017. “Early Career Teachers’ Emotion and Emerging Teacher Identities.” Teachers and Teaching 23 (4): 406–421. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1211099.

- OECD. 2015. Improving Schools in Sweden: An OECD Perspective. Accessed 23 February 2019. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/improving-schools-in-sweden-an-oecd-perspective.htm.

- Samuelsson, M., J. Samuelsson, and A. Thorsten. 2022. “Simulation Training–A Boost for Preservice Teachers’ Efficacy Beliefs.” Computers and Education Open 3: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100074.

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, O. 2013. “Team-Based Simulations: Learning Ethical Conduct in Teacher Trainee Programs.” Teaching and Teacher Education 33: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.001.

- Sirotnik, K. A. 1990. “Society, Schooling, Teaching, and Preparing to Teach.” In The Moral Dimensions of Teaching, edited by J. I. Goodlad, R. Soder, and K. A. Sirotnik, 130–151. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education]. 2018. Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare: Revised 2018. Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=3984.

- Sumsion, J. 1998. “Stories from Discontinuing Student Teachers.” Teachers and Teaching 4 (2): 245–258. doi:10.1080/1354060980040204.

- Sveriges Radio [Swedish Radio]. 2019. Stora avhopp från lärarutbildningarna [A lot of attrition from teacher education]. Accessed 01 September 2020. https://sverigesradio.se/artikel/7292587.

- Teng, F. 2017. “Emotional Development and Construction of Teacher Identity: Narrative Interactions About the Pre-Service Teachers’ Practicum Experiences.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online) 42 (11): 117–134. doi:10.14221/ajte.2017v42n11.8.

- Thornberg, R. 2012. “Informed Grounded Theory.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 56 (3): 243–259. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.581686.

- Timoštšuk, I., and A. Ugaste. 2010. “Student Teachers’ Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1563–1570. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.008.

- Väisänen, S., J. Pietarinen, K. Pyhältö, A. Toom, and T. Soini. 2017. “Social Support as a Contributor to Student Teachers’ Experienced Well-Being.” Research Papers in Education 32 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1080/02671522.2015.1129643.

- Yuan, R., and I. Lee. 2015. “The Cognitive, Social and Emotional Processes of Teacher Identity Construction in a Pre-Service Teacher Education Programme.” Research Papers in Education 30 (4): 469–491. doi:10.1080/02671522.2014.932830.

- Yuan, R., and I. Lee. 2016. ““‘I Need to Be Strong and Competent’: A Narrative Inquiry of a Student-Teacher’s Emotions and Identities in Teaching Practicum.” Teachers and Teaching 22 (7): 819–841. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1185819.