ABSTRACT

This multi-sited ethnographic study explores how pre-service teachers (PSTs) address pupil diversity during their practicum at lower secondary schools and how this is facilitated by their participation in university courses. This investigation’s focus on diversity is grounded in the concept of differentiated instruction. We found out that university teaching contributes to PSTs having a positive approach towards pupil diversity and that in their practicum PSTs succeed in taking the needs of certain groups of pupils into account in the classroom. However, PSTs take the needs of pupils into account unevenly and tend to homogenise their teaching on their practicum, to which the university curriculum also contributes by not being sufficiently experience-based and not providing a systematic framework for addressing the needs of all pupils in the classroom.

The topic of pupil diversity is an important part of teacher education, because for each pupil to experience success at school and develop their full potential, it is necessary to address their individual educational needs. It is a difficult task, because the needs of pupils are very diverse, whether with regard to different learning preferences, academic strengths, socio-cultural background or e.g. health condition (Tomlinson Citation2022). This complex pupil diversity represents a significant professional challenge especially for pre-service teachers (PSTs) (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2016), who need considerable guidance in order to learn how to recognise and address the individual needs of diverse learners (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2019). To fulfil this goal PSTs need practical teaching experience in authentic contexts as well as quality university courses that develop foundational understandings about differentiation (Dack Citation2019a; Sherman Citation2009). When researching how differentiation is addressed in initial teacher education, PSTs’ voices should be involved more often (Ruys et al. Citation2013), but triangulation of different data sources to overcome the limits of self-reported surveys is also needed (Griful-Freixenet, Struyven, and Vantieghem Citation2021). Thus, the goal of this ethnographic study is to explore how PSTs address pupil diversity during their practicum and how this is facilitated by their participation in university courses.

Conceptualisation of pupil diversity

Although according to statistics, pupil diversity in the Czech educational system has been growing since the Velvet Revolution, there is no dominant characteristic of pupil diversity in the Czech context resulting from the available measured indicators. Altogether, on average in a classroom in a mainstream school about 10% of pupils have special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), socio-culturally disadvantaged backgrounds or parents from other countries (Czech Statistical Office Citation2019). Pupil diversity, however, results not only from different socio-cultural backgrounds, language skills or health conditions of pupils, but also from other diverse individual educational needs based on academic strengths, instructional pace, learning preferences, motivations etc. Therefore, we approach pupil diversity through the concept of Differentiated Instruction (DI, Tomlinson Citation2017), which represents a framework for understanding diversity by going beyond narrow conceptualisations arising from socio-cultural categories, such as race, ethnicity or gender (e.g. Banks and Banks Citation2019), or from SEND, such as autism or learning disabilities (Swanson, Harris, and Graham Citation2013).

Pupil diversity at the lower secondary schools and university researched is not addressed through DI, nor through any other specific unified approach; neither mentor teachers nor teacher educators are trained in such an approach and consequently, PSTs do not have any courses in their university preparation in which they learn specifically about DI. However, we based our research on the DI concept, which we work with as a ‘sensitising concept’, giving us a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances (Blumer Citation1954). The DI concept enables an analytical understanding of the complexity of pupil diversity in the researched environments (see section ‘Data Analysis’).

DI defines the principles of quality differentiation with regard to the individual specifics of each pupil in a diverse class and at the same time reflects on how to take the frequently appearing types of identified learning needs into account, defined e.g. through performance level or disabilities (Tomlinson Citation2022). DI is an approach to teaching in which the teacher proactively modifies the content (what pupils learn), process (how pupils learn) and product of their teaching (how pupils demonstrate what they have learned) to address the diverse needs of pupils, which are shaped by their readiness (entry point relative to a particular understanding or skill), interest (curiosity, or passion for a particular topic) and learning profile (formed through learning preferences, gender, culture etc.) (Tomlinson Citation2017). The basic components of DI include teachers’ positive attitudes; an environment that supports learning; the diagnosis of pupil progress through ongoing assessment; usage of flexible grouping; and adapting teaching to the level of individual pupils.

Previous research has shown that PSTs experience difficulties in implementing DI (de Jager Citation2013), lack of confidence (Brevik, Gunnulfsen, and Renzulli Citation2018) and internal struggles (Wan Citation2016). According to PSTs, it is difficult to implement DI, for example, due to problems with classroom management, difficulties with fair assessment of pupils (Wan Citation2016), learners’ socio-emotional responses or time required to plan differentiated lessons (Dack Citation2019b; Goodnough Citation2010). On the other hand, PSTs’ self-efficacy (Wertheim and Leyser Citation2002), usage of ongoing assessment, as well as self-regulation and motivation are important predictors of successful DI implementation (Griful-Freixenet, Struyven, and Vantieghem Citation2021). Moreover, teacher education can change PSTs’ beliefs in a positive way (Wan Citation2016) or can lead to their acquiring knowledge of DI (Goodnough Citation2010). Nonetheless, positive beliefs about DI may not in themselves be sufficient for PSTs to implement DI on their practicum. Although PSTs perceive DI as important, they lack the strategies needed to translate those beliefs into practice (Wertheim and Leyser Citation2002). However, if teacher educators focus solely on differentiation’s practical tools without presenting the foundational understandings, PSTs can appropriate only surface features (Dack Citation2019a; Sherman Citation2009) or ‘narrow’ understandings (Nepal, Walker, and Dillon-Wallace Citation2021) of DI. Related to this, the fact that PSTs often leave preparation programmes unable to apply DI effectively may be due to the lack of coherence in how differentiation is addressed across different teacher education programme components (Dack Citation2019a). To translate a university curriculum concerning differentiation into PSTs’ practice, teacher educators should model beliefs and practices effectively (Dack Citation2018; Ruys et al. Citation2013).

Methodology

In this paper we asked the research questions: 1) How do PSTs reflect on and work with pupil diversity during their practicum at lower secondary schools? and 2) How is dealing with pupil diversity supported by PSTs’ participation in university courses? Pupil diversity refers to the fact that each pupil has individual educational needs, which are shaped by many influencing factors, such as learning preferences, socio-cultural background or health condition of the pupil. Addressing individual educational needs is thus the central subject of our analysis.

To answer the research questions, we used an ethnographic methodology, which is characterised by studying what people do and say in everyday contexts, while combining various techniques of data collection and putting emphasis on long-term participant observation (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). In exploring the ways in which the management of pupil diversity among PSTs is facilitated during their practicum by their participation in university courses, we were inspired by multi-sited ethnography. Its main principle is a focus on ‘chains, paths, threads, conjunctions, or juxtapositions of locations’ (Marcus Citation1995, 105), and its strategy is about connecting sites that are fruitful from the perspective of the researched phenomenon, which is produced in several locations. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic led us to respect even more the imperative of multi-sited ethnography – following people in their physical as well virtual environments, because the PSTs did some of their teaching on their practicum online and at the university some of the seminars also took place online. The partial shift of the undertaken research from the physical to the virtual research field, where we collected about one third of our data, enabled us to observe how the participants addressed the researched phenomenon in another environment (Bagga-Gupta, Dahlberg, and Gynne Citation2019).

Participants and data collection

The main participants in the research were PSTs (n = 8) enrolled as students in a two-year master’s programme, the completion of which entitles them to become teachers. Data were collected at three lower secondary schools located in a large city in Czechia where PSTs taught and at the selected university where they completed their studies. Observations of the PSTs’ teaching were conducted within the subjects English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Civics () and collected via fieldnotes. PSTs’ practicums last for three semesters, and each semester they have to complete 120 hours, of which they teach for approximately 40 lessons.

Table 1. Pre-service teachers’ characteristics.

The data collection took place at a university where PSTs were taking four general educational courses (pseudonymised as Course 1, 2, 3 and 4) as part of their master’s studies, in which the topic of pupil diversity is typically reflected on cross-sectionally. Providing ‘content-infused’ courses is one of the ways in which the issue of pupil diversity is incorporated into the curriculum of teacher education programmes (Guðjónsdóttir and Óskarsdóttir Citation2019). The courses are conducted in the form of interactive seminars with groups of about 20 students. Students can pass the courses through active participation in class and the completion of ongoing tasks, often linked to the practicum.

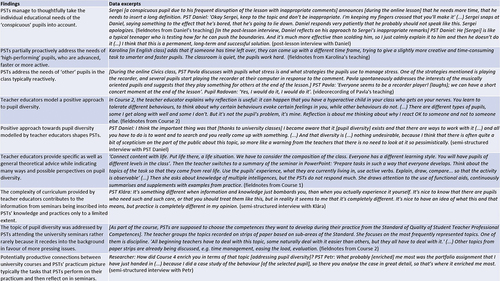

In order to comprehend the investigated phenomena fully, we collected various data sources (). All the data was collected in Czech. The data excerpts included in the manuscript were translated into English and discussed by researchers for meaning consistency and accuracy. During the interviews with the research participants, we asked thematic questions (e.g. What comes to your mind when thinking of pupil diversity? or How did you respond to the individual educational needs of the pupils in the classes?).

The data collection at the lower secondary schools and the university took place over three semesters for a period of 10 months in total, during the academic years 2019/2020 and 2020/2021, with varying intensity depending on the individual situation of PSTs, and the limitations related to anti-pandemic COVID-19 measures.

All participants in the research, including parents of pupils from the examined classes, signed consent forms which were approved by the Research Ethics Committee. All data has been anonymised using pseudonyms.

Data analysis

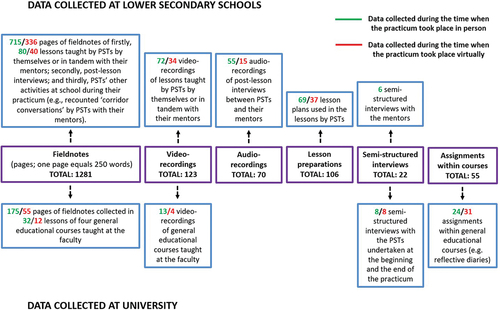

Data analysis in ethnography is not a distinct stage of the research process; subsequent data collection is strategically guided by the findings emerging from ongoing data analysis; and analysis needs to become gradually more focused. Data sources were analysed in line with the ‘grounded theorising’ principles (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007), specifically via close reading, coding, categorising and memoing. This systematic approach to analysis was useful for comprehending large and diverse data sets and thus ethnographic analysis is often inspired by grounded theory (Charmaz and Mitchell Citation2007). For more information on data analysis, see .

We enhanced the validity of the data by explicating the unique meanings and perspectives constructed by individuals acting and thinking in a particular context as well as by prolonged engagement of researchers in the field (Cho and Trent Citation2006). More specifically, we followed several analytical strategies to enhance the validity of our findings. Firstly, the coding was accompanied by researcher synchronisation so that the data snippets could be coded as unanimously as possible. This was ensured by: 1) formulation of clear definitions of all codes after they had been inductively created; 2) joint meetings, where researchers compared the degree of agreement in the application of codes on different data sources and came to a mutual understanding. Secondly, by respecting the idea that coding is a recurrent process, researchers repeatedly read and coded the data in several analytical phases to ensure the groundedness of the findings. Thirdly, we used triangulation, i. e. developing analysis and interpretation by contrasting different data sources (see ) from various environments (lower secondary schools and university environments as well as physical and virtual environments) as well as by using different data collection techniques. While triangulation of data sources is based on the comparison of data relating to the same phenomenon but deriving from different participants or phases of the fieldwork, triangulation of different methods is based on comparing data produced by different data collection techniques (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). Triangulation was facilitated by the Atlas.ti program where different data sources were coded simultaneously and thus contrasted constantly, with the exception of videorecordings, which were analysed selectively if other coded data sources were not sufficiently detailed. Finally, the findings are based on a cross-case analysis of all participants and are grounded in richly saturated codes and categories.

Throughout the analysis, we respected the strongly inductive nature of ethnography, while we also used the theory of DI as a ‘sensitising concept’ (Bowen Citation2006). We balanced between two analytical positions, where important categories of DI served as background ideas which informed our inductively driven data collection and analysis. This means that although our analysis was shaped by the concept of DI, it was not translated into a pre-conceived coding scheme. We explicitly dealt with the DI categories in findings and their interpretation.

An important part of our research process was researchers’ reflexivity focused on our different positionalities. Therefore, we reflected on the impact of our presence on the field relations as well as the analytical process in the fieldnotes during data collection and analysis (Lichterman Citation2017). For example, the researchers sought to put their expertise to one side in interactions with research participants in data collection and then reflected in the data analysis on how their expertise as perceived by participants could influence them in the way they interpret the data. As a result, reflection on researchers’ positionalities enhanced the quality of the collected data and guided us when interpreting the data.

Findings

We present the outcomes of the analysis in the following two sections in line with our research questions. Illustrative data excerpts are listed directly in the text, but also in Appendix A.

How pre-service teachers addressed pupil diversity during their practicum

Our findings demonstrate that PSTs took the needs of pupils into account unevenly. While they successfully took the individual educational needs of ‘conspicuous’ pupils into account, they failed to address the needs of ‘other’ pupils, who, however, made up the majority in the class.

The dominant patterns in our data show that PSTs managed to thoughtfully take the individual educational needs of the ‘conspicuous’ pupils into account. These were typically pupils with SEND but also pupils without formalised support measures who were conspicuous in terms of their degree of disruption, pace, motivation etc. This was not a group of pupils with the same type of needs, but nonetheless we classified pupils in this analytical category if their needs were urgent.

When differentiating for ‘conspicuous’ pupils, most PSTs typically used a well-thought-out set of strategies, similarly to those proposed by DI, which they sometimes applied within one-on-one instruction, but especially within a whole class work. This finding can be illustrated in situations where PST Daniel took the educational needs of Eda, a pupil with Asperger’s Syndrome, into account. For example, Daniel described a situation where he helped Eda recall the meaning of a word in English because Eda has trouble remembering words.

I would sit with Eda once in a while, and we would tackle some of the vocabulary. (…) It might have been jingle bells. And I would try to lead him towards it, saying, it is golden, and it can clink (…) ‘Well, this is the word in Czech’ and ‘Do you know the English expression?’ (…) And he would squeal with pleasure when he remembered it and looked very happy that he was able to decipher it. (Semi-structured interview with Daniel)

PST Daniel demonstrated one of the strategies he used to help Eda recall vocabulary in English. Daniel differentiated for Eda’s individual needs at the level of the teaching process and in response to his learning profile in other situations too, e.g. by recognising the social need to let Eda work repeatedly in a group with the same people during group work (fieldnotes from Daniel’s teaching) or by working sensitively with situations where Eda could be called on and there was a risk he would not know the correct answer (post-lesson interview with Daniel).

Similarly, the following excerpt demonstrates how PST Pavla considered strategies for taking the individual educational needs of a ‘conspicuous’ pupil into account.

The teacher told me that the young lady actually had ADHD (…) How I worked with her, it really worked for me to give her that attention, to call on her and (…) you can see a lot from her that she has low self-esteem, so when I praised her a lot, she was very calm, eh, tactical ignoring also worked on her. (Semi-structured interview with Pavla)

The quote from the interview reveals how Pavla reflected on various successful strategies for supporting her pupil Zora. Although Pavla was aware of Zora’s challenging behaviour (e.g. emotional volatility, rage, vulgarity), she expressed strong empathy for Zora despite a number of teachers having already given up on her. She considered her first experience with an ADHD pupil an excellent opportunity to gain experience in this area (Pavla’s reflective journal).

The needs of ‘other’ pupils in the classroom did not manifest themselves as significantly as in the case of ‘conspicuous’ pupils and the PSTs almost never took them into account. From the PSTs’ perspective, these pupils did not figure as individuals with unique educational needs, but rather as a group of average pupils to whom it was possible to teach the syllabus homogeneously. PSTs’ differentiation for the needs of these pupils took place exclusively within the whole class work, and these procedures were unplanned: PSTs responded to a situation in teaching, without previously reflecting on the specifics of the pupil. This reactive way of differentiation, referred to within the DI framework as ‘micro-differentiation’ (Tomlinson Citation2017), can be illustrated in an excerpt depicting PST Adam’s discussion with pupils in an online civics class. Pupil Slávek inserted a funny inscription into the task performed in an online application instead of his opinion.

The slide shows a picture of an apple, which is golden on the surface but rotten inside. Adam asked the pupils to think about what this could symbolise. They submit their definitions through the application. Slávek is leading in terms of ‘likes’, because he submitted an image with the text: ‘I know that I know nothing’. Adam comments that Slávek must have prepared himself very well for online classes because he has a folder with funny pictures. (Fieldnotes from Adam’s teaching)

Adam responded with humour to Slávek’s activity and added an ironic comment that Slávek was well prepared. However, Adam’s response was essentially just a reactive confirmation of Slávek’s needs for a funny performance in front of the class as well as for a relaxed environment for learning based on his learning profile.

Another example of reactive differentiation was evidenced by a situation from a civic education lesson, when PST Natálie was dealing with her pupil Leona’s reluctance to participate in group work.

Leona sits alone, she is not involved in a group. Natálie asks her about her opinion on conflicts and tells her to join someone in a group. Leona says that she does not like to be with others, that she prefers to work alone. Natálie says that she understands, but that it is important to overcome it, ‘you should try to overcome it, it will be useful to you in the future’. (Fieldnotes from Natálie’s teaching)

In this case, Natálie responded reactively to Leona’s need to work independently by patiently explaining to her the benefits of group work for the development of her social competences. The pattern of reactive differentiation for the ‘other’ pupils was occasionally disrupted only by PSTs somewhat proactively addressing the needs of ‘high-performing’ pupils, who were advanced, faster or more active. This can be illustrated by a situation with PST Petr. ‘Petr checks the pupils’ work, and if someone has finished, he assigns them exercise 3’ (fieldnotes from Petr’s teaching). In a research interview, Petr reflected on this differentiation strategy:

(…) thinking about the fact that some pupils would finish earlier, so what will they do so that they don’t start to get bored and disturb others in some way, I found it very useful. (Semi-structured interview with Petr)

PST Karolína also considered the involvement of high-performing pupils: ‘(…) when it is something more complicated, (…) I normally call on the better ones’ (semi-structured interview with Karolína). These procedures typical of most PSTs, i.e. assigning another exercise or a more demanding task to ‘high-performing’ pupils, were PSTs’ differentiation strategies related to content and pupils’ readiness. In post-lesson interviews, PSTs sometimes reflected on the needs of ‘high-performing’ pupils, which indicates they planned their actions to a certain degree. Nevertheless, the primary purpose of these reflections was often to address the needs of the class as a whole rather than to devise a strategy to take the needs of ‘high-performing’ pupils into account.

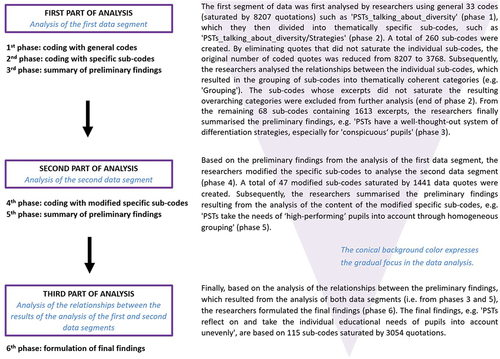

The presented excerpts show that PSTs differentiated unevenly in their teaching and illustrate the differences in PSTs’ differentiation regarding ‘conspicuous’ pupils and pupils forming the rest of the class. demonstrates that while the needs of a minority of pupils in the class were taken into account the most, the needs of the majority of pupils were taken into account the least.

Figure 3. The extent to which pre-service teachers address pupils diversity in their practicum.

We determined the extent to which PSTs differentiated for pupils on the basis of the two criteria: 1) the degree of attention that PSTs paid to individual pupils, i.e. the frequency of differentiating interactions, which was regular for ‘conspicuous’ pupils, occasional for ‘high-performing’ pupils, and minimal for ‘other’ pupils, and 2) the extent of pro/re-activity, i.e. how thoughtful and planned the strategies applied by PSTs were. PSTs’ differentiation for pupils’ educational needs was: a) completely spontaneous (reactive), which was typical for PSTs’ interaction with the vast majority of pupils in the classroom, b) to some extent pre-thought out (partly proactive), concerning the interactions of PSTs with ‘high-performing’ pupils, or c) thought-out (proactive), which the PSTs performed in relation to ‘conspicuous’ pupils.

When PSTs proactively differentiated for ‘conspicuous’ pupils they typically focused on their needs based on a learning profile. On the other hand, when they addressed the needs of ‘high-performing’ pupils, it was typically partially proactive and based on their readiness (cf. Tomlinson Citation2017).

How university teaching facilitated PSTs’ learning to address pupil diversity

We identified three dominant teaching strategies of all university teachers involved in this research, through which they conveyed the topic of pupil diversity:

modelling their approach to pupil diversity – e.g. the teacher, when explaining how to conduct a diagnostic interview, emphasises acceptance of shy pupils and respect for their responses (Fieldnotes from Course 4); the teacher made sure that for PSTs in the back rows of the classroom, the font in the PowerPoint presentation was large enough to read (Fieldnotes from Course 3);

providing specific advice and lessons, often linked to a practical example from the teacher’s experience, e.g. the teacher advised how to use an alpha pupil to integrate a pupil with SEND (Fieldnotes from Course 4); the teacher advised that pupils with attention deficit disorder needed to be calmed down, not kept busy and overloaded (Fieldnotes from Course 3);

providing general and/or theoretical advice and instruction – e.g. teacher educators expressed their rather negative views on the application of a social norm in assessment, while they underlined the importance of formative assessment (Fieldnotes from Course 1); the teacher recommended a respectful approach to pupils to break the teacher-pupil barrier (Fieldnotes from Course 4).

Teacher educators typically modelled a positive relationship to pupil diversity, which is in line with the DI concept where positive attitudes of teachers are considered to be important for creating an invitational learning environment (Tomlinson Citation2017). We can illustrate this with an example of a teaching situation in which the teacher emphasised the importance of PSTs’ knowledge about the pupils in the classroom, which she presented positively, even emotionally.

In response to other examples, the teacher says, ‘You have different pupils, but you must show them and their parents that you have a heart for everybody’, stressing that a teacher’s task in each subject is to ‘work not only with the content but also who we have in a class’. (Fieldnotes from Course 1)

The analysis also showed a positive approach towards pupil diversity modelled by teacher educators shaped PSTs, as illustrated by Pavla’s statement about one of her courses.

We really must approach our pupils individually, with a certain tolerance, with respect, yes. And this is what the course can inspire in us most of all, in my opinion (…) that there should be some understanding towards the children from us as teachers. (Semi-structured interview with Pavla)

Teachers thus contributed to the fact that PSTs considered pupil diversity to be something natural, something that was ‘okay’, as evidenced, for example, by Daniel’s statement: ‘I started to be aware that it [pupil diversity] exists (…) that diversity is not something undesirable’ (Semi-structured interview with Daniel).

In addition, all the university teachers managed to address the topic of pupil diversity with PSTs by indicating many ways and possible perspectives on the different needs of pupils, even with examples from their own teaching experience. In the university courses observed, teacher educators demonstrated a very wide range of specific topics and advice related to working with pupil diversity. The educators addressed e.g. working with pace; taking the different ‘starting points’ and performance of pupils into account; formative assessment; personalisation of teaching; and involvement of pupils in group work. In line with the DI perspective (Tomlinson Citation2017), teacher educators paid attention to all dimensions of pupil variance (readiness, interest, learning profile) as well as to the importance of formative assessment and flexible usage of different interaction patterns when being responsive to pupil diversity.

On the other hand, in the data we did not find indications showing that general or specific advice on working with pupil diversity significantly shaped PSTs. All the PSTs usually found it difficult to recall general educational courses from the university curriculum; they confused them and talked about them in general terms. According to them, these courses have a rather theoretical character, as illustrated by the following quotes:

I don’t remember much about what we did (…) I guess I don’t remember anything specific. (Semi-structured interview with Natálie)

It seemed to me that it was more on a theoretical level, but in my practicum I didn’t really use it much. (Semi-structured interview with Adam)

Our data showed that no matter whether teacher educators’ advice or instructions were theoretical or entirely specific, in the end they became ‘theory’ for PSTs. However, when PSTs were able to connect the subject matter related to the topic of pupil diversity discussed at the university to their own practical experience, they reflected more deeply on it.

It’s nice to learn about it theoretically from some of those lessons but (…) What actually happens in your practicum and you actually experience it (…) yourself it really influences you and a lot of it stays in your memory. I can then identify with it more in those specific examples [from university courses]. You’re not just hearing that someone has experienced it, but you experience it yourself. Well, you can identify with it and think more deeply about it. (Semi-structured interview with Karolína)

PSTs tended to integrate mainly information connected with their own practicum experiences into their mental structures. The complexity of the curriculum provided by teacher educators contributed to the information from seminars being inscribed into PSTs’ knowledge and practices to only a limited extent. It follows that due to a lack of connection of university teaching with PSTs’ personal experiences and the absence of a comprehensive systematic framework for addressing pupil diversity in higher education, PSTs were not able to differentiate their teaching to address the needs of all pupils in the classroom.

It turns out that once PSTs found themselves on their practicum, they were confronted with a number of new situations and challenges, which was clearly evident in Course 2, the aim of which was to give PSTs space to reflect on their own practical experience. In this course, PSTs addressed themes such as cooperation with a mentor or behaviour management, but the topic of pupil diversity was addressed by all the PSTs attending the seminars rather rarely because it recedes into the background in favour of more pressing issues (fieldnotes from Course 2).

However, we also identified potentially productive connections between university courses and PSTs’ practicum, typically within the tasks that PSTs performed on their practicum and then reflected on in seminars. For example, Pavla reflected on the task given in Course 4, in which the PSTs had to diagnose the individual educational needs of the selected pupil during their practice:

I have to admit that this was one of the best assignments we had to work on during my entire studies, because for the first time I felt like a real teacher in every way. (…) I consider creating proposals for measures to be a great experience, because I had the opportunity to really think about everything I saw in the school environment around the selected pupil, and to find out and obtain a lot of new information that will be useful to me in the future. (Task assigned within Course 4)

These tasks eliminated the perceived theorising of the curriculum by PSTs as they increased the practical relevance of university courses for PSTs.

Discussion

Our research showed the promises and challenges regarding how PSTs addressed pupil diversity during their practicum at lower secondary schools as well as regarding how university teachers facilitated PSTs’ learning to take the diverse needs of pupils into account. To conceptualise pupil diversity we used the DI framework. We found that PSTs differentiated unevenly in their teaching during their practicum. We understand the thoughtful and proactive differentiation of ‘conspicuous’ pupils by PSTs as well as the partial differentiation of ‘high-performing’ pupils as a promising step away from typically undifferentiated teaching. Similarly, previous research has shown that differentiation is focused especially on low- and high-achieving pupils, because these groups of pupils are challenging for PSTs (Brevik, Gunnulfsen, and Renzulli Citation2018; Tomlinson et al. Citation1997). PSTs’ narrow understanding of addressing pupil diversity (Nepal, Walker, and Dillon-Wallace Citation2021) corresponds with public discourse in Czech (Štech Citation2021) as well as international contexts (Guðjónsdóttir and Óskarsdóttir Citation2019; Woodcock et al. Citation2022), where a short line is drawn between inclusion and challenging pupils, typically those with SEND, and consequently diversity is viewed predominantly as a special needs concept.

In our research PSTs struggled with addressing the needs of the majority of pupils, as these did not manifest distinctively and thus PSTs usually approached them as average pupils (cf. Tomlinson Citation2022) to whom the syllabus can be taught uniformly. Also, in their lesson plans PSTs did not reflect on their differentiation strategies, and typically created the same plan for all pupils within a whole class work, which provides only limited space for individualisation or working with small groups of pupils. All this testifies to the tendency for PSTs to homogenise the teaching process, i.e. to plan and implement teaching with respect to the average level of pupils so that it can take place uniformly for the whole class. From this perspective, the partially proactive addressing of readiness of ‘high-performing’ pupils can be understood as an attempt by PSTs to correct deviations that disrupt the ‘teaching in the middle’ tendency (Tomlinson Citation2017), similar to the proactive addressing of the learning profile of ‘conspicuous’ pupils, without which there would be a risk that these pupils would be excluded from the homogenised teaching or might even disrupt the class.

The analysis of our data from university courses showed that pupil diversity was included in the curriculum from many perspectives and over a diverse range of topics. Teacher educators succeed in providing PSTs with many opportunities to learn about the different types of educational needs of pupils and how to address them. Moreover, we showed that PSTs were shaped by the positive discourse on pupil diversity modelled by the course teachers. As a result, they had a predominantly positive approach to pupil diversity (Moon, Callahan, and Tomlinson Citation1999; Wan Citation2016); however, the instructions of university teachers regarding addressing pupil diversity were not inscribed much into PSTs’ practice. Even specific advice from teachers became a kind of ‘theory’ for them as soon as it was not linked to PSTs’ practical experience (cf. Korthagen, Loughran, and Russell Citation2006). Although the university curriculum captured pupil diversity in a complex way, it did not mediate it systematically to PSTs (cf. Santangelo and Tomlinson Citation2012), i.e. as an overarching conceptual framework that would guide the use of pedagogical tools (Dack Citation2019b). It follows that incongruities among programme components such as coursework and fieldwork (Dack Citation2019a) or between different university courses (Guðjónsdóttir and Óskarsdóttir Citation2019) regarding addressing pupil diversity can cause confusion among PSTs and negatively affect their appropriation of differentiation.

The fact that PSTs did not remember that much from the university curriculum may also have been due to the tendency that university educators themselves did not tend to model differentiated practices much in seminars (cf. Swennen, Lunenberg, and Korthagen Citation2008), or that their modelling of differentiation was not explicit (cf. Santangelo and Tomlinson Citation2012). The influence of implicit modelling of differentiation on PSTs is limited (Dack Citation2018; Ruys et al. Citation2013). The absence of a systematic and experience-based curriculum as well as regularly modelled differentiation practices could contribute to the needs of most pupils in the classroom being side-lined in favour of more pressing issues, such as classroom or time management (Moore Citation2003). In such a situation a homogenising approach to teaching was a solution for PSTs to cope with pupil diversity. Relatedly, under the influence of the many demands of their practicum, PSTs can experience ‘reality shock’ (Korthagen, Loughran, and Russell Citation2006) and tend to conform to traditional ways of teaching, i.e. teaching to the middle (Tomlinson Citation2017). Instead of obtaining the information about pupils needed to conduct differentiated teaching, which is laborious (Goodnough Citation2010), it may seem more effective to mostly address the more conspicuous needs of pupils and otherwise to tailor their teaching to the average classroom level so that it is homogenous for the whole class.

Based on our research findings we suggest several implications. It has been shown that PSTs should be taught about differentiation in depth by providing them both with practical strategies as well as critical theoretical principles before entering the teaching profession, when early patterns of teaching are forming (Dack Citation2019b; Griful-Freixenet, Struyven, and Vantieghem Citation2021). Importantly, PSTs should comprehend differentiation as a theory to be applied in a contextually sensitive way, rather than as a set of teaching strategies (Sherman Citation2009). The results of our research support incorporating a holistic approach on addressing pupil diversity in teacher education programmes (Guðjónsdóttir and Óskarsdóttir Citation2019) as well as supporting coherence among different programme components (Dack Citation2019a).

Teacher educators should model behaviour in such a way as to ensure it translates into the thinking and practices of PSTs, e.g. by ‘meta-commentary’ (Swennen, Lunenberg, and Korthagen Citation2008). As providing regular and explicit modelling of differentiation in university seminars is essential but difficult, teacher educators should expand their own professional competences, especially with regard to giving meta-commentary (Ruys et al. Citation2013).

Moreover, our research also points to the importance of directly linking university teaching with PSTs’ personal practical experience, for example, through assignments (Sherman Citation2009), or other forms of practice-based artefacts.

Some of the limitations of our research are that due to the nature of the ethnographic methodology and the narrowing of our observations to EFL and Civics subjects, the findings from our research are not generalisable to the entire population of PSTs with their diverse teaching specialisations. This means that our results are limited by the selected subjects, which are specific in that, for example, a greater emphasis on interactivity can be assumed within them compared to other subjects, in which the addressing of pupil diversity may have other specificities. Further research should look at the use of various differentiation strategies in other subjects taught at lower secondary school. Although we analysed an extensive as well as complex ethnographic data set, our findings are limited because we captured individual pupils’ perspectives on how they view PSTs’ provision for their educational needs only indirectly via fieldnotes. We suggest future research should include pupils’ perspectives directly through formal interviews with pupils to comprehend the ways PSTs address the needs of diverse pupils in greater complexity.

Conclusion

The main purpose of this ethnographic study was to explore how PSTs address pupil diversity during their practicum and how this is facilitated by their participation in university courses. We contribute to the current research in the field of professional training of PSTs in addressing pupil diversity by providing robust findings based on a rich and extensive data corpus characterised by simultaneous emphasis on the thinking and behaviour of PSTs related to pupil diversity in two related settings, i.e. lower secondary schools and university. The most important contribution of our study lies in recognising the different levels of pro- and re-activity of PSTs’ differentiation strategies related to different types of pupils. Furthermore, we demonstrated that university teaching contributed to PSTs having a positive approach towards pupil diversity, but this was not inscribed sufficiently into PSTs’ knowledge and practices regarding addressing pupil diversity. We believe that enriching knowledge in the field with the results of our research will contribute to improving the quality of pre-service teacher education regarding addressing pupil diversity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation [grant number GA19-06763S, Ethnography of Diversity in Pre-Service Teacher Education]. We thank all the participants for their participation in the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bagga-Gupta, S., M. G. Dahlberg, and A. Gynne. 2019. “Handling Languaging During Empirical Research: Ethnography as Action in and Across Time and Physical-Virtual Sites.” In Virtual Sites as Learning Spaces, edited by S. Bagga-Gupta, M. G. Dahlberg, and Y. Lindberg, 331–382. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26929-6_12.

- Banks, J. A., and C. A. M. Banks, Eds. 2019. Multicultural Education. Issues and Perspectives. 10th ed. Hoboken, N. J: Wiley.

- Blumer, H. 1954. “What is Wrong with Social Theory?” American Sociological Review 19 (1): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088165.

- Bowen, G. A. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3): 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304.

- Brevik, L. M., A. E. Gunnulfsen, and J. S. Renzulli. 2018. “Student Teachers’ Practice and Experience with Differentiated Instruction for Students with Higher Learning Potential.” Teaching and Teacher Education 71:34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.003.

- Charmaz, K., and R. G. Mitchell. 2007. “Grounded Theory in Ethnography.” In Handbook of Ethnography, edited by P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, and L. Lofland, 160–174. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608337.n11.

- Cho, J., and A. Trent. 2006. “Validity in Qualitative Research Revisited.” Qualitative Research 6 (3): 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106065006.

- Cochran-Smith, M., A. M. Villegas, L. W. Abrams, L. C. Chávez-Moreno, T. Mills, and R. Stern.. 2016. “Research on Teacher Preparation: Charting the Landscape of a Sprawling Field.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching, edited by D. H. Gitomer and C. A, 439–547. Washington, USA: American Educational Research Association.

- Czech Statistical Office. 2019. Školy a školská zařízení - školní rok 2018/2019. Assessed August 28, 2021. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/skoly-a-skolska-zarizeni-skolni-rok-20182019.

- Dack, H. 2018. “Structuring Teacher Candidate Learning About Differentiated Instruction Through Coursework.” Teaching and Teacher Education 69:62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.09.017.

- Dack, H. 2019a. “The Role of Teacher Preparation Program Coherence in Supporting Candidate Appropriation of the Pedagogical Tools of Differentiated Instruction.” Teaching and Teacher Education 78:125–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.011.

- Dack, H. 2019b. “Understanding Teacher Candidate Misconceptions and Concerns About Differentiated Instruction.” The Teacher Educator 54 (1): 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2018.1485802.

- Darling-Hammond, L., J. Oakes, S. Wojcikiewicz, M. E. Hyler, R. Guha, and A. Podolsky. 2019. Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

- de Jager, T. 2013. “Guidelines to Assist the Implementation of Differentiated Learning Activities in South African Secondary Schools.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (1): 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580465.

- Goodnough, K. 2010. “Investigating Pre-Service Science Teachers’ Developing Professional Knowledge Through the Lens of Differentiated Instruction.” Research in Science Education 40 (2): 239–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-009-9120-6.

- Griful-Freixenet, J., K. Struyven, and W. Vantieghem. 2021. “Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices About Two Inclusive Frameworks: Universal Design for Learning and Differentiated Instruction.” Teaching and Teacher Education 107:103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503.

- Guðjónsdóttir, H., and E. Óskarsdóttir. 2019. “´Dealing with diversity´: Debating the Focus of Teacher Education for Inclusion.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (1): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1695774.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography. Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Korthagen, F. A. J., J. Loughran, and T. Russell. 2006. “Developing Fundamental Principles for Teacher Education Programs and Practices.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (8): 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022.

- Lichterman, P. 2017. “Interpretive Reflexivity in Ethnography.” Ethnography 18 (1): 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138115592418.

- Marcus, G. E. 1995. “Ethnography In/Of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24:95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523.

- Moon, T. R., M. Callahan, and C. A. Tomlinson. 1999. “The Effects of Mentoring Relationships on Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Academically Diverse Students.” Gifted Child Quarterly 43 (2): 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698629904300202.

- Moore, R. 2003. “Reexamining the Field Experiences of Preservice Teachers.” Journal of Teacher Education 54 (1): 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102238656.

- Nepal, S., S. Walker, and J. Dillon-Wallace. 2021. “How Do Australian Pre-Service Teachers Understand Differentiated Instruction and Associated Concepts of Inclusion and Diversity?” International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1916111.

- Ruys, I., S. Defruyt, I. Rots, and A. Aelterman. 2013. “Differentiated Instruction in Teacher Education: A Case Study of Congruent Teaching.” Teachers & Teaching 19 (1): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.744201.

- Santangelo, T., and C. A. Tomlinson. 2012. “Teacher Educators' Perceptions and Use of Differentiated Instruction Practices: An Exploratory Investigation.” Action in Teacher Education 34 (4): 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.717032.

- Sherman, S. C. 2009. “Haven't We Seen This Before? Sustaining a Vision in Teacher Education for Progressive Teaching Practice.” Teacher Education Quarterly 36 (4): 41–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23479283.

- Štech, S. 2021. “Výzkum, experti a politici – podivuhodný život ideje inkluzivního vzdělávání v ČR.” Pedagogika 71 (3): 403–420. https://doi.org/10.14712/23362189.2021.981.

- Swanson, H. L., K. R. Harris, and S. Graham. 2013. Handbook of Learning Disabilities. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Swennen, A., M. Lunenberg, and F. A. J. Korthagen. 2008. “Preach What You Teach! Teacher Educators and Congruent Teaching.” Teachers & Teaching: Theory & Practice 14 (5–6): 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802571387.

- Tomlinson, C. A. 2017. How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms. 3rd ed. Alexandria, USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Tomlinson, C. A. 2022. Everybody’s Classroom: Differentiating for the Shared and Unique Needs of Diverse Students. Washington: Teachers College Press.

- Tomlinson, C. A., C. M. Callahan, M. T. Ellen, N. Eiss, M. Imbeau, and M. Landrum. 1997. “Becoming Architects of Communities of Learning: Addressing Academic Diversity in Contemporary Classrooms.” Exceptional Children 63 (2): 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299706300210.

- Wan, S. W. Y. 2016. “Differentiated Instruction: Hong Kong Prospective Teachers’ Teaching Efficacy and Beliefs.” Teachers & Teaching 22 (2): 148–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1055435.

- Wertheim, C., and Y. Leyser. 2002. “Efficacy Beliefs, Background Variables, and Differentiated Instruction of Israeli Prospective Teachers.” The Journal of Educational Research 96 (1): 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670209598791.

- Woodcock, S., U. Sharma, P. Subban, and E. Hitches. 2022. “Teacher Self-Efficacy and Inclusive Education Practices: Rethinking Teachers’ Engagement with Inclusive Practices.” Teaching and Teacher Education 117:103802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103802.

Appendix A.

Additional Examples of Data Excerpts Illustrating Important Findings