ABSTRACT

Many members of the precariat in Aotearoa/New Zealand (NZ) struggle to access resources for leisure. This article draws on four interview waves with five precariat Māori (Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa/NZ) households (N = 32 interviews) using mapping and photo-elicitation interviews to explore participant leisure engagements. We document how precarious leisure for some Māori is assembled agentively by participants out of key elements associated with their situations (e.g. financial and housing insecurities) and core Māori principles and processes of whanaungatanga (cultivating positive relationships) and manaakitanga (caring for self and others). Participant accounts foregrounded the importance of mātauranga Māori (systems of knowledge) and culture in shaping contemporary leisure practices that can promote a sense of ontological security, place, belonging, connection, cultural continuity, and self as Māori. Though beneficial to self and others, participant leisure practices are rendered insecure by the resource restraints of life in the precariat.

Introduction

The precariat was initially conceptualised as an emergent social class populated by diverse groups experiencing insecurities in work, income, housing, and health (Standing, Citation2011). This emergence in Aotearoa/NZ (Groot et al., Citation2017) has been driven for indigenous Māori by the continuing impacts of colonisation, intergenerational resource confiscations, and cultural marginalisation (Rua et al., Citation2019, Citation2023). At 70% of the population Pākehā (descendants of European settlers) make up 63% of the precariat. At 16% of the population Māori are overrepresented at 28% of the precariat (Rua et al., Citation2023). Precarity for many Māori manifests in various ways, including reduced education achievement, low paid and insecure employment, unemployment, reduced civic participation, and heightened risk of illness and an untimely death (Rua et al., Citation2023; Schrecker & Bambra, Citation2015). This is because precarity is associated with key social determinants of health that have a disproportionate impact on Māori (Groot et al., Citation2017; Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017).

Drawing on the seminal work of Standing (Citation2011), Rua et al. (Citation2023) developed a cultural orientation towards the Māori precariat as a cultural assemblage (DeLanda, Citation2006/2019; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988) within the broader precariat assemblage. Such an orientation is important because although often presented with similar material challenges in life, not all persons and groups become situated within the precariat or experience and respond to associated insecurities in the same ways. Assemblage Theory was initially developed by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1988) to explore how different entities – from molecules to species, ecosystems, and institutions – take form and combine to influence one another in the constitution of the social world (DeLanda, Citation2006/2019). This theory offers a dynamic framework for understanding interconnections (relationships) between parts (elements), such as people, jobs, leisure practices, processes, policies, institutions, and wholes (assemblages) like the Māori precariat. Of central concern for our application of assemblage theory to leisure are processes of territorialisation through which such elements are woven together into collective alliances (co-existence) within a dynamic geography of relations that takes form as an assemblage of Māori precarious leisure (DeLanda, Citation2006/2019). As Rua et al. (Citation2023, p. 41) also propose, this processual understanding of the world presents a complimentary understanding to Māori theories of people as emplaced, relational, and emergent ‘ … beings entangled within larger dynamic social structures’ that are often inequitable, and which offer varying opportunities for human flourishing and, in the present case, leisure.

The core aim of this article is to explore the assemblage of Māori precarious leisure, and to document how various elements, including Māori cultural principles, relational practices, and ways of being are combined or territorialised in relation to elements of contemporary urban life when participants create opportunities for precarious leisure. Central to this exploration is how emergent engagements in leisure are adapted to the specifics of the participants precarious lifeworlds. This focus is important because, with notable exceptions, scholars have often overlooked precariat and indigenous leisure (Batchelor et al., Citation2020; Fox, Citation2006; Stronach & O’Shea, Citation2021). This article also responds to Batchelor et al. (Citation2020, p. 105) call for research into the consequences of inequitable socio-economic positioning on people’s access to and experiences of leisure as a space for participation in chosen activities that can offer respite and creative self-explorations (Kelly, Citation2019). In seeking to extend explorations of precarious and indigenous leisure, we draw insights from research documenting how leisure can provide moments of deepening connections with culture, community, self, and place (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2016; McGuire-Adams, Citation2020; Standing, Citation2011; Straker, Citation2022; Stronach & O’Shea, Citation2021; Waiti & Awatere, Citation2019; Waiti & Wheaton, Citation2022).

Precarious Leisure

Previous examinations of leisure practices among precariat groups suggests that rather than simply experiencing exclusion from leisure due to financial restraints, people often exercise considerable agency in creating leisure practices with others that enable them to work around socio-economic insecurities (Batchelor et al., Citation2020; Dhar, Citation2011; Green et al., Citation1990; Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2016). Supporting this view, Moore and Henderson (Citation2018) explored the everyday leisure practices of low-income couples, which encompassed housework, watching television, sightseeing bus rides, and attending church. Likewise, Dhar (Citation2011) documented how construction workers in India engaged in various leisure practices (chewing ‘khaini’ [tobacco], listening to music, being with friends, gossiping, and window shopping) to distract themselves from the stressors of precarious labour. Hodgetts and Stolte (Citation2016) documented how street homeless people in Aotearoa/NZ engaged in similar low-cost leisure practices, as well as engaging in ‘magical habits of mind’ by taking psychological journeys out beyond the material confines of their urban cityscapes and to re-member connections with distant persons and cultural traditions. Such engagements in precarious leisure have been linked to increases in a sense of place, ontological security, and wellbeing, which are associated with increased resilience against the negative health impacts of material deprivation (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017). These studies showcase how precarious leisure is fundamentally relational and often involves reimagining mundane everyday practices as a basis for cultivating social connections.

Previous research into leisure on the economic and cultural margins of society is important given the benefits of access to leisure for enabling indigenous people access to positive identities and opportunities for respite, wellbeing, and human flourishing. As Stronach and O’Shea (Citation2021, p. 5) propose:

… leisure activities and participation can contribute to feelings of belonging, how they contribute to the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous communities, how they strengthen the rights and welfare of Indigenous people and how they offer spaces for richer relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples through leisure.

Method

This article focusses on the leisure experiences of eight Māori households in Auckland. All participants representing their households were in jobs that paid below the official living wage ($23.65 per hour) and also relied on welfare assistance to make ends meet. Recruitment was facilitated through snowball sampling via E Tū (largest private sector union in the country), and household engagements occurred over a 18-month period. Due to the richness of participant accounts, we have included selected exemplars from five households (see ) in this article that capture reoccurring leisure pursuits evident across the research corpus.

Table 1. Household composition, employment status and income.

This study was anchored in Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR), which embraces the importance of continuing traditions of mātauranga Māori or knowledge production by Māori-for-Māori. KMR in this case features modes of open engagement with households that enact cultural principles of Tino Rangatiratanga (self-determination and sovereignty), whanaungatanga and manaakitanga in the knowledge production process (Pihama et al., Citation2015; Rua et al., Citation2023; Smith, Citation1999). Our approach was consistent with the cultural emphasis Māori have traditionally placed on building trust and reciprocity with participants as a basis for engagements in dialogue that contributes to transformative praxis (Smith et al., Citation2019). Correspondingly, household engagements were designed to be participative and culturally familiar to both the researchers and participants, and to inform Government policies to address the needs of precariat via a project advisory group. This KMR approach was also informed by our own experiences of engaging with other Māori who, like us, have come from precarious lifeworlds. As with the households, the authors carry intersectional diversities. All were raised in working class households, left school early, engaged in various insecure occupations, and came to university as second chance learners. The first author is the youngest woman in the team and is Māori (Waikato-Tainui), English and Scottish. The second author is the oldest male, identifies primarily as Pākehā, whilst also acknowledging his familial ties to Kāi Tahu. The third author is a mid-thirties male of Māori (Te Rarawa/Ngāpuhi), English and Scottish descent. The fourth author was adopted under the close stranger adoption system but has been informed she has whakapapa Māori. She is a whaea (aunty).

Engagements with households began with an initial meeting at their respective homes to explore the purpose of the research and enact whanaungatanga whereby the lead author and participants connected through the sharing of their tribal affiliations.Footnote1 This was followed by a series of four enhanced interviews, each lasting approximately 90 minutes and designed to explore a broad range of issues related to life in the precariat, including leisure practices. It was culturally important to conduct these engagements kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face) and to let the conversation evolve over a series of visits. Foundational to these engagements was the principle of aroha ki te tangata (respect for people within research) through the observance of key cultural practices, including taking the time to get to know participants and sharing food. This relational process allowed for more in-depth information to be entrusted between participants and researchers.

The inclusion of visual participative techniques (mapping, timelining and photo-elicitation) also facilitated the depth of conversation. For example, during interview two participatory mapping was employed to aid participants in situating and discussing different facets of their everyday lives and spaces for leisure (McGrath et al., Citation2020). Between interviews three and four participants were asked to take photographs of places, situations, objects, and relationships discussed and/or drawn during the initial interviews, or which they felt were particularly salient to our dialogue (Hodgetts et al., Citation2007). The participants then led interview four by taking the first author through the photographs and explaining the content. These engagements with the five households listed above generated 20 interview transcripts, 22 drawings, 75 photographs, and 46 pages of field notes for analysis.

Analysis process began with all authors reviewing the empirical materials and coming together to wānanga our initial thoughts regarding participant accounts over a series of days (cf., Hodgetts et al., Citation2022b; King, Citation2019). Wānanga are a key feature of the KMR whereby collaborators seek to reach a collective interpretation of empirical materials through open dialogue (King, Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2019). We used a projector to display photographs, maps, interview extracts and related fieldnotes that had been identified as interesting by different authors. This iterative and non-replicable process of collective analysis also featured abductive reasoning (local inference) whereby extracts from the household engagements were brought into dialogue with insights from Māori culture, academic theory, and research into precarity and indigenous leisure. This process reflected characterisations of qualitative researchers as bricoleurs (Kincheloe, Citation2005) who work, in this case collaboratively as a rōpū (group of scholars) to weave together information from various sources to create an exemplified interpretation of the phenomenon under investigation (Hodgetts et al., Citation2022c). Through this initial process we identified particular leisure practices, spaces, relationships, cultural principles and concepts, benefits and costs of precarious leisure, and ways of being Māori through leisure that could be used as heuristics for categorising and interpreting participant accounts from across the eight households. The first author then went back to the empirical materials for the five randomly selected households and systematically coded the engagement materials in relation to these heuristics. The authors then engaged in a further series of wānanga (writing workshops) with the categorised materials to produce the findings.

Findings

The findings are presented in four sections. First, we deepen the conceptual basis for the analysis by conceptualising Māori leisure practices and exploring how these are implicated in the contemporary rearticulation and reterritorialization of aspects of Te Ao Māori (the traditional Māori world), particularly the marae (conceptualised below). Section two, then explores participant efforts to cultivate a sense of community through enactments of key relational imperatives towards the care of self and others that are central to the assemblage of Māori precarious leisure. This is followed by an exploration of sports clubs as key leisure sites for Māori that approximate the mutual support and connection, respite, and care that traditionally inhabits marae. This then leads to an exploration of threats of disruption to participant leisure practices and the strategies participants use to enable their continued engagements in precarious leisure practices.

Māori precarious leisure practices and the reterritorialization of marae

In exploring participant accounts of leisure activities and how these were implicated in the re-assemblage of what we recognised as traditional Māori relational principles we turned to social practice theory, which links personal (micro) actions to the reproduction of broader cultural (macro) systems (Blue, Citation2019). As a result, we mobilised key cultural heuristics to interpret how various practices were implicated in the assemblage of Māori precarious leisure. These practices comprise creative, thoughtful, and often routinised actions that allow people to not only gain some respite from adversity and enhance their wellbeing, but to also reproduce themselves culturally as Māori (King et al., Citation2018). We came to conceptualise Māori precarious leisure practices as manifesting multiple existences ontologically as key personal, collective, and cultural features of the assemblage of precarious leisure. This is because the activities participants report engaging in are shaped by both their agentive decisions and the broader cultural traditions and socio-material positionings from which these practices emerge (Blue, Citation2019; King et al., Citation2018).

It became particularly apparent that participant leisure practices reflected the continuation of everyday marae-based relational work that is grounded in mātauranga Māori (Waiti & Wheaton, Citation2022) that participants adapted to their lives in contemporary urban settings (King et al., Citation2018). In its most general sense, the marae is often understood as the cultural epicentre of everyday Māori life, often (but not always) located in rural areas where ancient ancestral continuities are seeded (Walker, Citation2004). Contemporary articulations of marae are often narrowly referred to as a set of physical structures, including wharenui (meeting house), wharekai (dining room), wharepaku (ablution block) and marae ātea (open area space in front of the wharenui) that are located on one’s tūrangawaewae (ancestorial place to stand and belong) (Rua et al., Citation2017). However, marae invokes much more and can manifest as a more fluid cultural institution for the everyday gathering of people for the conduct of things Māori and the reproduction of communal ways of being together. This occurs through the ongoing adaptation of Māori customs (tikanga) and principles to meet the needs of contemporary existence (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). As documented below, traditional relational practices of leisure and care traditionally associated with marae life have been transferred into contemporary urban life and multiple locations encompassing domestic dwellings, parks and sports clubs, for example. As Te Awekotuku (Citation1996, p. 35) explains, ‘for it is a Māori belief that wherever Māori people gather for Māori purposes and with the appropriate Māori protocol, a marae is formed at that time, unless it is contested’.

As evident with other indigenous groups (Fox, Citation2006; McGuire-Adams, Citation2020; Stronach & O’Shea, Citation2021), Māori precarious leisure practices are anchored in traditional relational principles that serve to promote respite, mutual support, connection, and wellbeing. Contemporary precarious leisure practices also reterritorialize elements from Te Ao Māori, including cultural imperatives towards whanaungatanga (cultivating meaningful relations with others) and manaakitanga (Waiti & Awatere, Citation2019; Waiti & Wheaton, Citation2022), and ancestorial marae (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). Adding further cultural nuance here, our argument should not be read to mean that locales like urban sports clubs are marae in the ‘traditional’ ancestral sense. Rather, principles, customs, and practices associated with the marae have been stretched out through the assemblage of contemporary precarious leisure into new urban locations (King et al., Citation2018).

Despite the positive personal and relational benefits of contemporary leisure, participation in particular practices can also be brought into tension with key elements of precarity, such as a lack of money. Evident in the following from Bob is how everyday life in the precariat often requires ‘trade-offs’ between keeping a precarious job that enables one to gain fulfilment by enacting manaaki towards others and continued participation in motorsport, for example:

With the work I’ve chosen to do [teacher aide], the trade-off was it doesn’t pay very well. It’s the only job I’ve ever loved. It’s fulfilling me culturally… Everything else [leisure pursuits] I have come to terms with – like I just can’t do Motorsports as I would like …

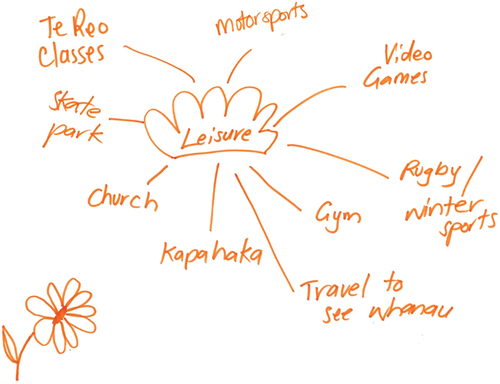

Such restraints on leisure were often surfaced during the leisure mapping exercise where participants drew and discussed key leisure practices that they find rewarding, but which are rendered precarious due to resource restraints. For example, depicts the leisure map drawn by Bob and Jenny that features key elements in the assemblage of Māori precarious leisure that encompasses both overtly Indigenous leisure practices (e.g. Te Reo Māori language class, Kapa Haka or performing arts) and practices that appear on the surface to be non-IndigenousFootnote2 (e.g. motorsport, gaming, gym, rugby), but which as we will show are modified culturally to fit Māori ways of being and relating to others.

To recap, reiterating key points raised in by Bob, Jenny also talked about how many of the depicted practices had been halted due to their precarious income, to be replaced with free or more cost-effective pursuits that are discussed throughout the following three sections. We will show how creating and sustaining opportunities for leisure often required considerable agency from participants as they assembled strategies that enable them to navigate their precarious access to leisure. This often involved finding low-cost alternatives, sacrificing time with whānauFootnote3 to generate funds, or going into debt to provide leisure options for the children.

Cultivating leisure and meaningful connections through enactments of manaaki

Colonisation has dislocated many Māori from their tribal homelands and ancestral marae (Walker, Citation2004). In response, cultural principles such as whanaungatanga and manaakitanga live on through contemporary urban Māori precarious leisure practices. Enactments of these principles offer some cultural continuity in terms of enacting meaningful connections to, and a sense of community with both Māori and non-māori persons (cf., Fox & McDermott, Citation2020). The emphasis participants placed on cultivating such connections through localised leisure practices makes sense in the context of their positions of precarity where funds for venturing further afield is limited (Standing, Citation2014). As such, participating whānau spent a vast majority of their leisure time at home together and in local civic and domestic spaces that afforded moments of human connection, respite, and a sense of being as Māori (Rua et al., Citation2017) within local urban networks and everyday settings.

Significant to these participants experiences is how a sense of belonging is cultivated through processes of whanaungatanga and manaakitanga that extend from whānau towards elderly neighbours. For example, when discussing the household’s leisure pursuits, as represented by the photo-elicitation exercise (see ), Ana spoke at length about the importance of her household living a connected life in the cul-de-sac. Ana recounted how, along with other local children, her three embark on adventures in the cul-de-sac, much like free-range children do on ancestral marae:

So, there’s next door, there is Sarah, and she is five. Then Nicola, I think she is eight or nine. They just get together, ride their bikes around the cul-de-sac, or they will go visit the elderly couple down the road. They have a vegetable garden and Mary takes the girls into the back garden and shows them all the things and picks herbs and things out of the garden and gives them to the girls. Then they go visit Jane and Arthur across there. They’re a retired couple. And get mints from Jane, or they will go and talk to Jane, and they always give Jane hugs.

and the corresponding caption above foreground Ana’s perception of the children’s local adventures as a key leisure practice that cultivates community connections and a shared sense of belonging in the cul-de-sac.

The relationships invoked are reciprocal and feature Ana’s children learning through leisure to socialise with other children and to show manaaki towards elderly neighbours. Children being allowed to roam around a local setting is also a traditional form of leisure ‘tipi haere’ (to roam) for Māori children. Historically, Māori children were encouraged to be bold and independent, often learning through participating in public life and forging their own respectful relationships with elders (E Tū whānau, Citation2018). Such practices affirm principles of mutuality of care and shared learning processes that span generations. Ana’s account also reflects her embracing the traditional role of the aunty in such collectivised settings whereby Māori mothers of her age are central to the planning of community leisure activities that deepen mutually supportive local ties via residents spending time together:

I organised a neighbourhood street party … We had barbeques, bouncy castle because that house there, the brick house, they run a bouncy castle business … Everyone came out with their barbeques … It was nice.

Evident within Ana’s account is the importance of neighbourly connection and enactments of belonging that contribute to the creation of an enclave of care (King et al., Citation2018) within which local people are afforded opportunities to cultivate meaningful connections through their participation in leisure. This exemplar highlights how marae-based practices, like coming together can be introduced into the assemblage of precarious leisure in urban settings and serve to cultivate whanaungatanga beyond the physical confines of the ancestral marae. Ana’s account is reminiscent of King et al. (Citation2018) analysis of how members of the precariat engage in being Māori in the city by reassembling aspects of the culture through new articulations of core values and relational practices that have their genealogy in everyday life in ancestorial marae. Through necessity, these practices are often transformed materially in terms of their reterritorialization in urban settings, but maintain their deeper cultural functions, which in turn, contributes positively to the overall wellbeing of the inhabitants of the cul-de-sac.

In many respects the leisure practices above are not devoid of work in the relational sense as seen in the earlier conceptualisations of leisure (Iwasaki, Citation2008). Leisure has long served as work in the practical world for low-income people, in particular (Dhar, Citation2011). In addition, leisure for women has been woven into and around household chores (Green et al., Citation1990). For Māori, it is also conventional to work to support collective leisure activities and the inclusion of others as a means of caring for oneself as a relational being at a deeply spiritual level. For example, doing the dishes for large groups of people frequenting an ancestorial marae as a group of workers is often a long and labour-intensive task that is made leisurely through the accompanying dialogue, storytelling, and kitchen banter that builds and maintains caring relationships.

To explore these ideas further, we now consider how participants offered various accounts of creative leisure practices related to the work of domestic selfcare. Like that of work on an ancestral marae, for these participants housework was re-territorialised agentively within their homes as a relaxing leisure practice that offered a sense of agency, respite, achievement, satisfaction, and selfcare. Cleaning and cooking, often with whānau, was repeatedly identified as a form of leisure that offered fleeting moments within which participants could immerse themselves in shared activities with loved ones, unwind and distract themselves from the outside complexities of life in the precariat. For example, Nan identified cleaning as a favoured domestic leisure practice that enabled her to gain mental respite from the outside stressors of precarity whilst caring for her grandchildren:

‘I like to clean … Say if I’m worried or uneasy about something outside, I just forget all about it … Yeah, I suppose some people go for a run (for leisure). I like to go and clean.

In a similar vein, Mārama spoke about how her preferred quality leisure time with her daughters was spent engaged in the mundane task of watching television as they folded the washing:

I watch all of the trashiest TV shows that I can possibly find … So, we’ll sit around on my bed with the TV going and we will fold the washing together, my daughters love ‘Beverly Hills Housewives’.

Mārama goes on to talk about the importance of such routine leisure pursuits for them to connect and have fun as a whānau. As discussed by Green et al. (Citation1990), such gendered and domesticated leisure practices enable women to use their free time to not only complete domestic chores, but to also escape precarity for a time. Such instances of precarious leisure provide opportunities for participants to transcend the emotional toll of precarity through ‘magical habits of mind’ that often feature in hard lives, and which allow people to escape their material conditions (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2016). Also, evident here are gendered cultural traditions of collective domestic work, indicative of marae-based practices, through which Māori spend quality time together and deepen bonds of connection and being Māori (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). As discussed below, such culturally patterned interweaving of domestic/whānau work and leisure also features efforts to enact care towards others that extends out beyond domestic settings and into other sites for community, including sports clubs.

Sports clubs as prime leisure spaces for connecting Māori with the neighbours

Participants emphasised the importance of sports clubs and teams as prominent sites (elements) for leisure beyond the home. This was not simply about playing sport, but also being part of the community through coaching or running the kitchen at a club. The emphasis on sport is consistent with both historical and contemporary evidence that links Māori to collective leisure practices that provide vehicles for cultivating social ties, and increasing physical and mental wellbeing (Thompson et al., Citation2017). Pre-European contact, Māori engaged in various forms of sport as an integral part of everyday life on the marae (Borell & Kahi, Citation2017). Subsequently, Māori have engaged in sports, such as rugby after their introduction to Aotearoa/NZ from the 1870s, including the running of venues and clubs at least since the 1880s (Hokowhitu, Citation2009).

In emphasising sport as a key leisure pursuit, participants referred to various marae-based practices and contributions to various clubs as connection points for engagements with other parents, children, and community members. These engagements are significant in that one of the markers of precarity is reduced civic engagement (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017; Standing, Citation2014). Often through light-hearted accounts and images, participants also spoke to the sense of respite, connection, and enjoyment that sports enabled. Below, Bob discusses rugby as a means for him to connect socially and how he dreams of playing rugby with his sons one day:

That’s our socialising as well. That’s how we get our social connection through the winter; we just see our friends at rugby … All three of the boys play rugby, like I was saying earlier. Saturdays in winter that’s kind of our thing … I want to play with them, that’s one of my dreams.

In addition, Jenny also presented an image of Bob playing rugby () and the conversation continued with reference to the importance of friendships and family for enactments of culturally anchored connections via leisure. As Jenny stated: ‘It’s just like having another family when you go to rugby pretty much’. This couple talked about how Bob is the captain for his team and the children participate in cultural practices with their teams, including karakia (ritual chants for spiritual guidance). Reflecting the cultural reworking of rugby to accommodate things Māori, Jenny stated: ‘He’s captain so for him and for his team it very much works in a Māori way … When the kids have home games, they karakia for our kai’. Evident within these discussions is an effort to assemble a leisure space that maintains whānau connective alliances with cultural practices such as karakia and provides continuity in and the socialisation/enculturation of their children within these customs.

Bob and Jenny’s sense of community through sports resonated with the accounts of the other participants, but with nuanced difference. For example, Ana outlined how she plays netball and touch rugby, how her children also play sports, and how this affords the whānau a sense of belonging and fulfilment, manaakitanga and whanaungatanga. Ana coaches her daughter’s netball team and helps at the rugby club where her sons play. Evident in accounts of such practices is the reproduction of Māori values of parenting through which the marae raises children collectively, and parenting can become blurred with activities such as coaching:

I play sports. It goes well with my active relaxing sort of thing … Socialising through team sports … I know how to parent with sports too … I coach my daughter’s netball team. I help out at the rugby club … It helps me feel connected to my community and that’s really important. It does give me a sense of belonging, being part of those sport groups. It’s important for my kids too, because the people who are part of those sport groups recognise my children and they’re invested in them … Parents have watched mine grow as well as their own kids. Same with me. I’ve watched these other kids grow up and I feel invested in them. I know them and I love them… It’s so comforting to know that there are all these other adults who care.

Ana’s account invokes her sense of belonging, ontological security, and continuity in being that is realised through teamwork and her engagement in leisure practices that make positive contributions to the local community life. Also evident is the articulation of a sense of shared emotional attachment whereby the parents of the other children also become invested in her children.

Cultural connections to local sports clubs were also foundational to Nan’s account, albeit with slight differences in the articulation of core Māori cultural values, such as manaakitanga. Nan runs the kitchen (wharekai) at the local rugby club on Thursday (training) nights and Saturday mornings (game-day) and does so by reproducing core marae-kitchen practices. Nan is not simply the ‘cook’ or ‘kitchen worker’ in a Pākehā sense. Nan is a distinguished and well-respected woman who works in the kitchen to care for the players and supporters culturally, which is a recognised leadership role for older women on marae (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). By acting as a ringawera (kitchen worker) and providing for local people and manuhiri (visitors) during sports events Nan contributes to the maintenance of the mana (high standing) of the sports club, just as is done on ancestorial marae. Such ringawera play a pivotal role in the reproduction of traditions of manaaki and the sharing of mātauranga (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012).

Nan enjoys her role and sees it both as a practical contribution to the club and form of enjoyable and relaxing leisure that provides her with a sense of cultural continuity and ontological security through feeding and caring for players and their whānau. Evident in her account of this practice is a form of hūmarie or kind-hearted gentleness in service to others that is sorely missed when absent from such kitchens. The following extract from Nan also reflects a key function of the wharaekai as a space for reminiscing, sharing stories and reconnecting with others in ways that renew shared identities and a sense of security as Māori:

Feeling centred in myself and just unwind. Also, too, it is meeting other people, adults. I just have the children at home … We are quite well known for being born and raised here. I am 61 and there is still a lot of old people living that knew mum and dad well, so it is good to hear memories that they have of our parents, too … The rugby club is quite a good place to find those interactions … And to see kids that were younger than me and watching their children grow up too, and me feeding their children. It was my dad that used to feed the rugby players back in the day and I would have to help do the cooking too then, and now it is me doing all the cooking…

Also, evident here is an articulation of whakapapa (intergenerational connection and continuity to people and place) in that Nan’s father had also engaged in these culturally patterned practices. Nan is also enacting tikanga in caring through the provision of food at the club in ways her father taught her at this very club. Nan presents herself here as having grown up in the club and as involving herself in keeping whānau practices alive in a manner common to marae (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). For Māori, such practices bring a sense of belonging, emotional attachment, and security. The practice of women of Nan’s age running the wharekai is recognised culturally as crucial for engendering a collective sense of belonging, the sharing of collective memories, connections, and what can be read as therapeutic work that nourishes community continuity. This leisure work is culturally important as an articulation of belonging, leadership, and continuity of place. As we will see in the section below, it also requires considerable agency in order to be sustained due to the threats to participation posed by precarity and issues such as income and housing insecurity, with many Māori having to relocate from legacy areas when rents rise to unaffordable levels (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017).

Threats of disruption that render leisure practices precarious

Whilst highlighting how beneficial leisure can be for gaining respite and supporting personal and communal wellbeing, participants also pointed out how the scope, form, and continuity of their engagements in leisure are often rendered precarious due to their socio-economic positioning (Standing, Citation2014). For example, whilst belonging to a sports team/club was articulated as beneficial to the research participants, it was also constructed for their households as precarious because of factors such as the consequences of living on limited incomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Several participants also reported that they avoided enrolling their children into sports due to the costs of equipment and membership fees. For example, Trish, talked about how her two eldest sons had not joined a sports team/club due to costs. Subsequently, Trish discovered that sponsors funded children’s fees and uniforms, and this meant that her third son could be enrolled in a club. During the photo elicitation exercise Trish produced a photograph of her son being awarded player of the day ():

Here’s my sports child [depicted]. Got player of the day that day … But I fully missed the boat with the older boys playing sports because I thought it costed hundreds … Yeah. Did not know how to get in with the sponsor … He loves it. He has made me proud.

This exemplar speaks to the importance of broader processes of care and support, in this case from sponsors in precariat communities that enable increased participation in collective leisure practices and the mitigation of financial barriers that can render children’s participation precarious. Such forms of inclusive care signal the valuing of children and their participation and were also evident in Nan’s efforts to ensure all players are fed, even if they do not have money to pay for the food her wharekai provides:

The kids that don’t have money to buy anything on a Thursday … They’re sitting there waiting. And I’ll see them out in front of my window sitting at the tables … They look cold and I just call them over and go, ‘Would you like some hot chips?’ ‘I’ve got no money’. I say, ‘I didn’t ask that. Would you like some hot chips?’ And they say, ‘Yes please’. I say, ‘Here you go. Would you like a hotdog or something?’ ‘Oh no thank you. Just the chips will be good’ … Yeah, that community thing, and like even parents, you know, that come and thank me cos I’ve fed their children, that they want to pay me. I say, ‘Don’t worry about it’. That’s the Māori side of me. I don’t like to see kids being hungry or cold after training; and not have a kai. [food]

Evident here is a culturally patterned interaction between a kuia (female elder) and tamariki (children) in that Nan offers the children manaaki in the form of hot chips. They accept with a thank you that promotes whanaungatanga and inclusion in leisure. Nan went on to state overtly that her offering food in this way comes from her ‘Māori side’ and commitment to caring for the community in ways characteristic of the marae.

The cultural significance of Nan’s leisure work and kindness in the club kitchen is also evident in how the small amount of money she makes from selling food at very reasonable prices enables her to support her grandchildren. Also feeding other children with even less than her and her grandchildren reduces the surplus she generates for their household, but this is preferable to her not realising her subjectivity as an older Māori woman who cares through the provision of food for children. Nan finds respite and renewal as a Māori person through such culturally patterned leisure practices (Gillies & Barnett, Citation2012). Relatedly, Nan does not present these cultural imperatives of care for her own whānau and the children of the broader community in dichotomous terms. Meeting both imperatives enables Nan to realise herself in cultural terms as a kuia who embodies manaaki (Groot et al., Citation2011) in ways that engenders a shared sense of belonging, togetherness, and shared endeavour. However, Nan’s efforts are also rendered precarious by changing circumstances and recently by the COVID-19 pandemic, which meant that the rugby club could not function as usual for lengthy periods of time due to the introduction of new elements into the precarious assemblage such as Government mandated lockdowns. As a result, Nan was not able to help others and top up her precarious income to support her grandchildren to the same extent.

Reflecting the impacts of disruptions in precarious lifeworld’s, the participants also talked about their insecure housing situations and a lack of time and finances as impacting their abilities to engage in and sustain leisure practices. Participants expressed insecurities concerning what may happen if their rental accommodation was sold or rent increases forced them to find more affordable accommodation elsewhere. Such developments were seen as threats to participants’ abilities to maintain a sense of ontological security and marae-like connections for themselves and their children. Also raising similar concerns as Ana and Nan regarding the importance of remaining embedded within supportive communities, Mārama talked about having to move districts in the past due to being priced out of the local housing market. She feared this will happen again. When asked what owning her own home would mean, Mārama responded:

It would mean stability … Instead of having to worry if the house is going to get sold next year because house prices have gone up. It means that we can continue to be contributing members of our community, and that is something I feel strong about, and help our community grow and flourish. You need to be stable within that community. Yeah, I want my children to continue those important friendships, and the house that they have …

Mārama conveys a sense of insecurity that was common to all participants and was presented as undermining their ability to act as pou whirinaki through participation in collective leisure practices. Pou whirinaki are recognised pillars of strength who exhibit a constant positive presence in communities, and who offer leadership (e.g. coaching and providing kai), who can be relied upon for manaaki in times of hardship, and who promote inclusion and a shared sense of community across time (Hodgetts et al., Citation2022a).

A lack of time was also presented as significant for making participant leisure practices precarious. Time poverty is a well-known feature of precarity whereby participants are often exhausted due to having to work long and low paid hours that often restrict their leisure to practices that can be fitted in where possible (Hodgetts et al., Citation2022a; Standing, Citation2011). Participants’ reported working, often tirelessly, to get by financially and their leisure time beyond domestic and work-related practices was often disrupted and restrained in the process. Such time limitations also exacerbate the psychological labouring working parents often experience as compounding feelings of guilt and stress that can undermine wellbeing (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017).

Members of the Māori precariat remain resilient in terms of their engagements in leisure in the face of such disruptions and restraints. They cultivated various agentive strategies within the assemblage of their precarious leisure to achieve some quality time with whānau. This included simple practices such as keeping children up late after parents returned from work so they could play games or watch movies together. Mārama also warranted the purchasing of various leisure items for her children by going into debt with fringe lenders as a sacrifice she was willing to make personally to enhance the household’s participation in leisure. Below, Mārama speaks about purchasing a bicycle for her own wellbeing as a pre-diabetic person, and to ensure she was healthy for her children and could join them on bike rides ():

We ride bikes together … Although my children laugh at me … I’ve finally got my own bike. It took a long time for me to get my own bike. It’s something that I really wanted so I could spend that time with my children. Now they want bikes [upgraded] like mine … Put it on finance. I’m becoming indebted to the things like taking care of our wellbeing … I tried to get a bike for myself, a free one [via social media] but they’re just no good.

Mārama speaks to the unaffordability of supporting her wellbeing and becoming ‘indebted’ in order to take part in fun adventures with her children. Other participants echoed this orientation towards indebted wellbeing as necessary element of precarious leisure despite their knowing they may not be able to repay the loans back and may end up in debt servitude or poverty traps due to the high interest rates charged by fringe lenders (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017). In the process, debt becomes an element of the precarious leisure assemblage that intensifies aspects of household precarity and comes to haunt these participants with further stress. Here, participants accept the risk of ‘ … tipping over into a corrosive situation of unsustainable debt and chronic economic uncertainty’ (Rua et al., Citation2019, p. 3), and in recounting such situations offers key insights into the dialectics of the benefits and costs of participation in precarious leisure.

Conclusion

This article extends previous research into the Māori precariat as an assemblage (Rua et al., Citation2023) and Indigenous (Straker, Citation2022; Stronach & O’Shea, Citation2021; Waiti & Awatere, Citation2019; Waiti & Wheaton, Citation2022) and precarious leisure (Batchelor et al., Citation2020; Dhar, Citation2011; Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2016; Moore & Henderson, Citation2018) by documenting the precarious leisure practices of participating Māori households. We explored how Māori precarious leisure practices offer provisional instances of respite that remain open to various disruptions. We documented how their assemblage of various leisure practices functions as a key aspect of contemporary life in the Māori precariat. As Stronach and O’Shea (Citation2021) have proposed, Indigenous accounts of leisure foreground community creativity and strengths in the face of considerable disruptions, and feature articulations of Indigenous knowledge systems and community practices. This article also contributes to emerging explorations of how Indigenous peoples can engage in leisure as culturally unique persons, and in ways that foster connections with other persons from non-Indigenous groups (Fox & McDermott, Citation2019). In the present case, it is through these leisure practices that aspects of mātauranga Māori and associated cultural imperatives towards whanaungatanga and manaakitanga that are traditionally associated with marae and can foster socio-cultural inclusion in new urban settings (King et al., Citation2018).

Within this article, the concept of marae provided a core analytic backdrop for interpreting the ways in which precariat Māori who reside in contemporary urban settings can re-territorialise cultural ways of being relationally with others through their participation in precarious leisure practices. This study has showcased how precarious leisure is often enacted within and across locations, including domestic dwellings, streets, parks, and sports clubs. Assemblage processes of territorialisation are also evident in how participants bring together various elements in the form of practices such as playing sport and visiting the neighbours to create what we might term precarious leisurescapes for the care of themselves and those around them. Although issues of spatial mobility and interconnection have been considered in relation to the leisure of other groups (Green et al., Citation1990; Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2016), it is the cultural anchoring of important opportunities for leisure within and between particular locations that is particularly pertinent to the present case (cf., Waiti & Wheaton, Citation2022). It is through enactments of core Māori cultural principles as key elements of the assemblage of Māori precarious leisure to include practices such as playing team sports, coaching, feeding players and acting as role models for children that these participants bring the marae as an enclave of care into their urban environments (King et al., Citation2018). Doing so contributes to the cultivation of a sense of cultural continuity, ontological security, safety, and belonging within oneself and in relation to others.

Finally, participants presented their leisure practices as fundamentally relational, as fostering interconnections with people and places, and as a means of reproducing themselves culturally as Māori and constructive community members. Previous research with the health consequences of life in the precariat has foregrounded how important social connections invoked by these participants are in buffering people against the negative impacts of material deprivation and cascading insecurities (Hodgetts & Stolte, Citation2017; Rua et al., Citation2017). Despite highlighting these positive aspects of participant access to leisure, our analysis also suggests that it is important to conduct further research into disruptions that render various leisure practices precarious and how these might be mitigated. Further research should extend present understandings of how, whilst experiencing some respite from their participation in leisure, participants simultaneously experience feelings of guilt, shame, and anxiety when disruptions surface to remind them of their insecure positions in society and the fragility of their leisure pursuits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahnya Martin

Ahnya Martin is a graduate student currently undertaking a PhD in Psychology at Massey University. She descends from Waikato Tainui. Ahnya works as a Graduate Assistant for the School of Psychology. Her research interests include the health and wellbeing of Māori and indigenous, community and health psychologies.

Darrin Hodgetts

Darrin Hodgetts is Professor of Societal Psychology at Massey University where he explores issues of precarity, health, and human security.

Pita King

Pita King is a Kaupapa Māori Senior Lecturer at Massey University, Aotearoa New Zealand. He descends from the Northern tribes of Te Rarawa and Ngāpuhi. His training has been in analytic philosophy, and community and indigenous psychologies, and maintains a research focus on issues of urban poverty, social inequalities, and indigenous philosophies.

Denise Blake

Denise Blake is Associate Professor in the School of Health at Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington. She has over 25 years’ experience within the mental health and addiction sector as a consumer, health professional and researcher, which informs her interest in issues of health and social justice. Denise applies collaborative approaches to address complex social issues.

Notes

1. Although all participants identified as Māori, it is important to note that the term Māori signifies a heterogeneous collection of different tribal groups who manifest nuanced cultural distinctiveness (Royal, Citation2011).

2. The flower in the corner of represents Jenny’s reflections on the personal and collective growth and restorative and cultural benefits that come with such leisure practices.

3. The word whānau is used in various ways and can refer to a nuclear or extended family as well as community.

References

- Batchelor, S., Fraser, A., Whittaker, L., & Li, L. (2020). Precarious leisure: (re)imagining youth, transitions, and temporality. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1710483

- Blue, S. (2019). Institutional rhythms: Combining practice theory and rhythm analysis to conceptualise processes of institutionalisation. Time & Society, 28(3), 922–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X17702165

- Borell, P., & Kahi, H. (2017). Sport, leisure, and culture in Māori society. In K. Spracklen, B. Lashua, E. Sharpe, & S. Swain (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of leisure theory (pp. 127–141). Palgrave Macmillan.

- DeLanda, M. (2006/2019). A new philosophy of society: Assemblage theory and social complexity. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. (Massumi, Trans.). University of Minneapolis Press.

- Dhar, R. (2011). Leisure as a way of coping with stress: An ethnographic study of the low-income construction workers. Leisure/Loisir: Journal of the Canadian Association for Leisure Studies, 35(3), 330–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.614842

- E Tū Whānau. (2018). Our Ancestors Enjoyed Loving Whānau Relationships. https://etuwhanau.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ETWAncestorsBookWEBprint.pdf

- Fox, K. (2006). Leisure and indigenous peoples. Leisure Studies, 25(4), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360600896502

- Fox, K., & McDermott, L. (2020). The Kumulipo, Native Hawaiians, and well-being: How the past speaks to the present and lays the foundation for the future. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1633680

- Gillies, A., & Barnett, S. (2012). Maori kuia in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Perceptions of marae and how marae affects their health. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 10(1), 27–37.

- Gotfredsen, A., Goicolea, I., & Landstedt, E. (2020). Carving out space for collective action: A study on how girls respond to everyday stressors within leisure participation. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1815486. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1815486

- Green, E., Hebron, S., & Woodward, D. (1990). Women’s leisure today. In Women’s leisure, what leisure? women in society (1st ed., pp. 1–26). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20972-9

- Groot, S., Hodgetts, D., Nikora, L., & Leggat-Cook, C. (2011). A māori homeless woman. Ethnography, 12(3), 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138110393794

- Groot, S., Van Ommen, C., Masters-Awatere, B., & Tassell-Matamua, N. (2017). Precarity: Uncertain, insecure, and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Massey University Press.

- Hodgetts, D., Andriolo, A., Stolte, O., & King, P. (2022c). An impressionistic orientation towards visual inquiry into the conduct of everyday life. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 19(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2021.1901165

- Hodgetts, D., Chamberlain, K., & Radley, A. (2007). Considering photographs never taken during photo-production projects. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 4(4), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880701583181

- Hodgetts, D., Michie, E., King, P., & Groot, S. (2022a). Everyday injustices of serving time in a penal welfare system in Aotearoa New Zealand. Community Psychology in Global Perspective, 8(1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1285/i24212113v8i1p60

- Hodgetts, D., Rua, M., Groot, S., Hopner, V., Drew, N., King, P., & Blake, D. (2022b). Relational ethics meets principled practice in community research engagements to understand and address homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(4), 1980–1992. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22586

- Hodgetts, D., & Stolte, O. (2016). Homeless people’s leisure practices within and beyond urban socio-scapes. Urban Studies, 53(5), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015571236

- Hodgetts, D., & Stolte, O. (2017). Urban poverty and health inequalities: A relational approach. Routledge.

- Hokowhitu, B. (2009). Māori rugby and subversion: Creativity, domestication, oppression and decolonization. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 26(16), 2314–2334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360903457023

- Iwasaki, Y. (2008). Pathways to meaning-making through leisure-like pursuits in global contexts. Journal of Leisure Research, 40(2), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2008.11950139

- Kelly, J. (2019). Freedom to be: A New sociology of leisure. Routledge.

- Kincheloe, J. (2005). On to the next level: Continuing the conceptualization of the bricolage. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(3), 323–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405275056

- King, P. (2019). The woven self: An auto-ethnography of cultural disruption and connectedness. International Perspective in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 8(3), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000112

- King, P., Hodgetts, D., Rua, M., & Morgan, M. (2018). When the marae moves into the city: Being māori in urban Palmerston North. City & Community, 17(4), 1189–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12355

- McGrath, L., Mullarkey, S., & Reavey, P. (2020). Building visual worlds: Using maps in qualitative psychological research on affect and emotion. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 17(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1577517

- McGuire-Adams, T. (2020). Indigenous feminist gikendaasowin (knowledge): Decolonization through physical activity. Springer Nature.

- Moore, A., & Henderson, K. (2018). Like precious gold”: Recreation in the lives of low-income committed couples. Journal of Leisure Research, 49(1), 46–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2018.1457307

- Pihama, L., Tiakiwai, S., & Southey, K. (2015). Kaupapa Rangahau: A reader. Te Kotahi Research Institute. University of Waikato.

- Royal, C., MacIntosh, M., & Mulholland, M. (Eds.). (2011). Maori and social issues huia publishers (pp. 6–8).

- Rua, M., Awa, N., Whakaue, N., Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O., King, D., Pikiao, N., Cochrane, B., Stubbs, T., Karapu, R., Awa, N., Neha, E., Maniapoto, N., Chamberlain, K., Awekotuku, N., Harr, J., Maniapoto, N., & Groot, S. (2019, May). Precariat māori households today. Nga Pae O Te Maramatanga Te Arotahi Series, 1–16. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10289/14693/teArotahi_19-0502%20Rua.pdf?sequence=16

- Rua, M., Hodgetts, D., Groot, S., Blake, D., Karapu, R., & Neha, E. (2023). Conceptualizing and addressing the needs of the growing precariat in Aotearoa New Zealand: A situated focus on Māori. British Journal of Social Psychology, 62(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12598

- Rua, M., Hodgetts, D., & Stolte, O. (2017). Māori men: An indigenous psychological perspective on the interconnected self. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 55–63.

- Schrecker, T., & Bambra, C. (2015). How politics makes us sick: Neoliberal epidemics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

- Smith, L., Pihama, L., Cameron, N., Mataki, T., Morgan, H., & Te Nana, R. (2019). Thought space wānanga—A Kaupapa māori decolonizing approach to research translation. Genealogy, 3(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040074

- Standing, G. (2011). The precariat. The new dangerous class. Bloomsbury.

- Standing, G. (2014). A precariat charter: From denizens to citizens. Bloomsbury.

- Straker, J. (2022). In the caress of a wave. Annals of Leisure Research, 25(5), 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1829493

- Stronach, M., & O’Shea, M. (2021). Learning, understanding, and valuing Indigenous peoples’ leisure. Annals of Leisure Research, 24(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2021.1881709

- Te Awekotuku, N. (1996). Māori: People and culture. In D. Starzecka (Ed.), Māori art and culture (pp. 26–49). British Museum Press.

- Thompson, C., Kerr, R., Carpenter, L., & Kobayashi, K. (2017). Māori philosophies and the social value of community sports clubs: A case study from kapa haka. New Zealand Sociology, 32(2), 29–53.

- Waiti, J., & Awatere, S. (2019). Kaihekengaru: Māori surfers’ and a sense of place. Journal of Coastal Research, 87(sp1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI87-004.1

- Waiti, J., & Wheaton, B. (2022). Culture: Indigenous Māori Knowledges of the Ocean and leisure practices. In K. Petters, J. Anderson, D. Davies, and P. Steinberg (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of ocean space (pp. 85–100). Routledge.

- Walker, R. (2004). Ka whawhai tonu mātou = struggle without end. Auckland.