ABSTRACT

Visiting Natural Green Spaces (NGS) is an important lifestyle factor that contributes to quality of life. Whilst NGS can be used to combat health issues, many of which are experienced by South Asian Muslim communities in the UK, it is concerning that such communities face the largest disparities in access to NGS compared to other ethnic minority groups. This paper responds to the paucity in research of South Asian people’s experiences of NGS. Data were generated through individual semi-structured interviews with 20 South Asian Muslim men and women. Using Bourdieu’s concepts of field, habitus and capital, data underwent thematic analysis. This paper reports on the key findings of the study: defining the field of NGS; enhancing wellbeing in NGS; and challenges of accessing NGS. The study concludes that we understand NGS as fields in which capital is shaped by race, religion and gender, and provides suggestions for how policy and practice can consider NGS in health enhancing interventions.

Introduction

Natural Green Spaces (NGS) are green open spaces in and around urban areas as well as the wider countryside and coastline (Natural England, Citation2017).Footnote1 Urban NGS can include public parks and people’s own gardens. More rural NGS includes national parks, moors, beaches, forests, coves, and mountainous areas (Taylor & Hochuli, Citation2017). Engaging with NGS enhances quality of life in many ways (Roe et al., Citation2016). For instance, visiting NGS can help alleviate stress by providing a break from work and life commitments (Grant & Pollard, Citation2022). The minimised traffic, noise, and pollution found in NGS generates a sense of calmness for users (Grant & Pollard, Citation2022). Visiting NGS also encourages physical activity (PA) like running, walking, and sports, thus enhancing physical wellbeing (Eyre et al., Citation2015). This was particularly important during the COVID pandemic when fitness centres were unavailable, and NGS were of the few places where people could engage in PA (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Moreover, NGS has been shown to help strengthen relationships by helping individuals to connect with friends and family without the distractions of urbanity (De la Barrera et al., Citation2016; Gentin et al., Citation2019). Other work has demonstrated how NGS help users to feel more connected with God, enhancing their spirituality (Liu et al., Citation2021).

Whilst there are benefits of engaging with NGS, these are not experienced uniformly, noted that those from ethnic minority groups account for only 1% of visitors. Amongst the infrequent visitors to NGS are South Asians who experience various physical health related challenges. One study found 69.8% of a South Asian sample exhibiting obesity related factors, the highest across all ethnic minority groups within the UK (Emadian & Thompson, Citation2017). South Asian communities are also at risk of diseases related to physical inactivity as 30% of South Asians experience hypertension, 21% high cholesterol, and 17% diabetes (Abdulwasi et al., Citation2018; Mahmood et al., Citation2019; Shah & Kanaya, Citation2014). Similar issues exist in mental health too as Roe et al. (Citation2017) found those from South Asian backgrounds to be the least likely to engage with NGS and thus reflect the lowest scores in a mental health survey. With the focus of this study being South Asian Muslims, these statistics underscore the health challenges experienced by this demographic and the significance of engaging with NGS.

Barriers to accessing physical activity in natural green spaces for South Asian Muslim people

To understand a community’s engagement with NGS, it is important to acknowledge their experiences within wider leisure and PA. Less than half of a South Asian sample met the government’s PA guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week (Emadian & Thompson, Citation2017). Other research suggests that South Asians are 2.63 times more sedentary than the general population (Emadian & Thompson, Citation2017), reflecting them as being less active than any other ethnic minority group in the UK. Scholars have indicated cultural practice as one reason for these alarming statistics. Walseth (Citation2015) found a reluctance for some South Asian Muslim women to engage with sports due to immodest/revealing clothing requirements. Other studies have noted how some South Asian Muslim women have felt their engagement in physical activity misaligns with Islamic notions of modesty, particularly in relation to undertaking PA in public spaces (Benn & Pfister, Citation2013; Walseth, Citation2015). This is particularly relevant in swimming pools, where Benn et al. (Citation2011) and Soltani (Citation2021) highlight the difficulties some Muslim girls face in pools that are mixed gendered. Relatedly, Fletcher (Citation2014) reflected the difficulties British Pakistani Muslim cricketers face having to reconcile cultural practices around alcohol with their own Islamic beliefs.

Other research focusing on traditional sports and leisure settings including gyms, leisure centres, and school PE highlights cost and proximity as significant barriers to participation (Abdulwasi et al., Citation2018; Banga et al., Citation2020; Hamdonah, Citation2022; Iliodromiti et al., Citation2016). Sports and leisure centres often require specific attire, membership, and/or an entrance fee, yet NGS is generally accessible and free to the public. Less research focuses on informal settings, like NGS, for South Asian Muslim people. This is significant considering NGS can be used to combat the aforementioned health disparities through offering opportunities to engage in health enhancing activities (Picavet et al., Citation2016; Rigolon et al., Citation2021). Despite these benefits and the need for South Asian communities to increase participation in PA, engagement with NGS continues to be low (Natural England, Citation2019).

One reason offered for this low engagement involves the distribution of NGS in areas where South Asian people tend to reside. Indeed, 40% of people from ethnic minority communities live in England’s least green areas compared to 14% of White people (Ferguson et al., Citation2018). Coupled with the lack of a car/transportation, and/or knowledge of how to access NGS, people are challenged in their access to NGS (Avery et al., Citation2020). Thus, it is unsurprising that there are existing perceptions that NGS are for White users, leading to feelings of exclusion for ethnic minority communities (Stone et al., Citation2018). Research highlights minority groups often feel like trespassers when visiting NGS, particularly in rural NGS where more White people reside (Ferguson et al., Citation2018; Slater, Citation2022). Scholars have described NGS in the UK as White, middle class and male (Edwards, Citation2021; Stone et al., Citation2018).

Whilst little research focuses on engagement with NGS from a South Asians perspective, the few studies that exist offer some useful findings. Ratna (Citation2017) investigated the sentiments and meanings Gujarati elders associated with neighbourhood spaces that motivated them to walk. Slater (Citation2022), Morris et al. (Citation2019) and Edwards (Citation2021) included South Asians in their studies on access to NGS, identifying community-based initiatives, increased representation, and transportation as facilitating access. Yet, these studies are in the minority in comparison to research on ethnic minority groups in sport and PA contexts. This study therefore set out to address the paucity in this field with the help of Bourdieu’s conceptual framework to explore South Asian Muslim people’s experiences of NGS.

Conceptual framework

Bourdieu’s tools unveil practice and power dynamics at individual levels, aligning with the current study’s focus on space and individual experience and its’ emphasis on social inequality. Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977) identifies the links between structural conditions at the macro level, and individual actions at the micro level, particularly in relation to the (re)production of practices, behaviours, tastes and values, using habitus, field, and capital (Maton, Citation2014).

Habitus is a property of social agents; that is, a product of their structured and structuring conditions (Maton, Citation2014). Habitus is structured by one’s past and present circumstances such as family upbringing and is therefore the product of early childhood socialisation within the family and other social groups including schools, and neighbourhoods (Maton, Citation2014). It can be understood as the manifestation of a huge, but unconscious, matrix of embodied values and actions carried out by people in similar ways (Fernández-Balboa & Muros, Citation2006). It is structuring since habitus shapes present and future practices, and finally, it is also a structure, comprising a system of dispositions that generate perceptions, appreciations, and practices.

Importantly, an individual’s dispositions – as the conscious manifestation of habitus – ignite when occupying a given social space or, as Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977) terms it, field. According to Bourdieu (Citation1984), a field is a social arena and site of social interaction, within which the struggle and contestation over resources takes place. For example, a physical education class can be defined as a field because it is a social arena with characteristic practices and hierarchical relationships operating within clearly defined boundaries. Those who occupy the same field usually share a similar habitus and as such, reproduce the culture of that field through their practice. Such practices are formed by the doxa of each field, or the taken for granted assumptions of the field (Bourdieu, Citation1990). Fields are therefore key sites for the accrual and transmission of various forms of capital, which can be used to define an individual’s position within a field whilst supporting access to other fields.

Bourdieu (Citation1986) conceptualised capital in three ways, economic, social, and cultural. Economic capital broadly refers to one’s financial position. Social capital refers to an individual’s social connections, that is, their relational networks that can be drawn on to gain other forms of capital. Finally, cultural capital relates to all symbolic and material goods that might give an individual a higher status in the field. Capital can therefore be considered as something that is owned, but also something that is embodied (Bourdieu, Citation1986). The amount of capital accumulated by an individual can significantly influence the range of choices available within a specific field. In this case, it may determine an individual’s access to and practices within the field of NGS. This paper now turns to the methodology employed to investigate the participants’ engagement with NGS drawing on these theoretical concepts.

Methodology

Sampling and recruitment

Participants were initially recruitedFootnote2 through a community centre in Saddleston,Footnote3 an ethnically diverse city in the north of England. The community centre was useful to recruit from as: the researcher had personal connections with volunteers at the centre; it is located in a neighbourhood with a high population of ethnic minority residents, including those of South Asian origin and Muslim; and it has a diverse membership including men and women of different ages and from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Following ethical approval, access was granted via the community centre’s Delegations Officer who agreed to facilitate access to members and promote the study (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2013). The officer sought potential participants who matched the inclusion criteria for the study, each of whom was informed to contact the researcher directly by email. The lead researcher negotiated with the participants a meeting location and time. After initially recruiting seven participants, snowball sampling occurred whereby other individuals were introduced, leading to the recruitment of seven females and 13 males who were aged between 21 to 30 years and identified as Muslim. The sample characteristics can be attributed to the snowball sampling method, and recruiting those individuals who were most readily available to participate during the pandemic. Despite holding similar identity labels, the research team is keen to point out that this does not signify a common experience. For example, levels of religiosity, interpretations of Islam, and other aspects of each participant’s identity contribute to the diverse lived experiences within Muslim communities (Kloek et al., Citation2017). Some participants, for example, prayed five times a day, whilst others did not pray at all, and some of the women wore the female head covering, while others did not.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 South Asian Muslim individuals to allow for a diversity of experiences to emerge, whilst providing a consistent approach in the generation of data (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2013). Indeed, conducting interviews exclusively with South Asian Muslims facilitated a comparison of experiences within a group that are typically viewed in homogenised ways (Fletcher, Citation2014; Kloek et al., Citation2017). Semi-structured interviews were conducted using either face-to-face meetings or online videocalls on Microsoft Teams. This depended on the changing COVID-19 governmental restrictions that were in place at the time of the study and the interviewee’s preference. Whilst interviewing in person is effective in building rapport, online interviews mitigated some of the challenges associated with this method. For example, videocall interviewing can be cost and time effective and can mitigate some cultural challenges (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2013). For instance, some South Asian Muslim women may feel uncomfortable meeting a male researcher in person, deterring them from participating (Hamzeh & Oliver, Citation2010). Interviews typically lasted an hour and followed a predetermined interview schedule that included questions about the participant’s knowledge, preferences, and challenges faced when accessing NGS. Prompts and probes were used to gain in-depth insights into participant’s experiences. All interviews were recorded electronically and transcribed verbatim before undergoing analysis.

Data analysis

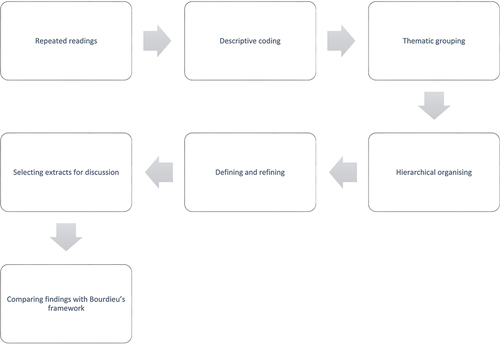

Data were analysed using a six stage thematic analysis process as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), helping to identify common threads of experiences within a range of diverse accounts (see ). This first involved closely examining the interview transcripts through repeated readings. Second, relevant excerpts which aligned to the study’s objectives were assigned descriptive codes. Third, codes were grouped together thematically. Fourth, codes that shared similarities were clustered together to form lower-order themes, which were subsequently grouped together to create higher order themes. This led to the creation of a thematic framework containing the hierarchies of themes. The fifth step included an ongoing process of defining and refining each theme, leading to a coherent narrative. Sixth, vivid excepts representing each theme were selected, and discussed in relation to the selected framework. The study did not enforce themes into the adopted framework but rather explored their compatibility with the existing concepts.

Results and discussion

From the analysis undertaken, three themes were identified: defining the field of NGS; enhancing wellbeing in NGS; and challenges of accessing NGS. These are depicted in below and are discussed next.

Defining the field of NGS

To gain detailed insights into the participants’ barriers to and motivations for engaging with NGS it was important to consider how they viewed NGS (i.e. field), as Bourdieu (Citation1984) depicted all fields as characterised by boundaries that mark the confinement of their impacts. For instance, natural features within NGS define the spatial boundaries wherein the effects of NGS are contained. In line with this concept, participants in the current study emphasised that the presence of natural features was a crucial element within NGS.

Trees, plants, park maybe, forest, scenic places, grass. (Sabah)

Natural green spaces?…a public park…land, areas that are green. (Hasy)

It is important to consider how the fields of NGS can manifest in nuanced ways. To highlight this, some participants referred to NGS that were more localised.

Even gardens, people’s gardens would be a natural green space. It’s got plants growing there. (Faheem)

Like a field like near my house … (Nabia)

Other individuals referred to NGS as areas that were further afield, often referring to rural areas.

I literally just think of like a really big outdoor space, with you know, landscapes and stuff. (Sophia)

Them kind of spaces, for example, would be Bolton Abbey. (Junaid)

Lake District, places like that. (Sany)

The woods isn’t it, a natural green space … or like a countryside. (Faheem)

It is unsurprising that the participants understood NGS in different ways from each other when the city that the study was undertaken in is considered. Saddleston, where all participants lived, has both large amounts of urban green space (36 public parks) and is situated in close proximity to more rural NGS on its outskirts. For example, within a 60-minute drive of the city there are county parks, national parks, moors, and reservoirs. Discussing these understandings helped in prompting the participants to reflect more deeply on their experiences with different kinds of NGS. Indeed, they interacted with NGS in a variety of ways, as demonstrated below.

We just went for a long walk … we just had a picnic, and we were just sat there, but just looking at the water flowing. (Nabia)

It feels more natural to run in the park than it does on the roads … The environment just sort of tells you or puts you in the mood. (Amir)

When I go climbing so to speak, I like these places where climbing is accessible. (Saad)

Among the sample of 20 participants, three gardened, two ran, two climbed, two engaged in bike riding, eight undertook sightseeing, eight walked, seven explored nature, six mountaineered, nine performed sports, four picnicked, and 19 socialised. Diversity was also evident in who they visited with as 12 generally visited with family, 10 with friends, and 9 alone. Those who visited with friends and family saw NGS as a viable place to socialise. This is evident in Nabs’ discussions, who viewed NGS as being a convenient context for her family to gather.

If you go to like Central Park … you can take food from home and you can eat together and you will basically do the same thing as going to each other’s houses, but instead we took it outside rather than staying in. (Nabs)

The emphasis for social engagement is an apparent feature of many of these South Asian Muslim participants’ interactions with NGS, but this is no different from wider communities, with the general population’s engagement with NGS also motivated by socialising (Phillips et al., Citation2022). In this research, South Asian Muslim individuals placed significant value on the meeting of others as part of their visits, highlighting the importance of communal areas within NGS. Spaces which facilitate social activity can help to fulfil preferences of socialising, enhancing users’ overall experiences of NGS. Moreover, NGS were seen as key to being able to socialise with friends and manage multiple commitments.

I think as you grow older you don’t have as much time to sort of see your friends … you have more responsibilities … so you can integrate both of them. It’s an opportunity to kind of do something you want to do, also catch up with friends. (Sammy)

The importance of NGS for social activity was particularly accentuated during the pandemic when social distancing measures limited opportunities to meet with others.

Just to meet people, like now, with the quarantine and stuff, it’s really hard to meet people, like, there needs to be a gap [social distance]. At least that way, if you were to visit green space, you could just meet your friends, but with a gap. You’re taking precautions and of course, socialising. (Nabia)

NGS allowed Nabia to continue meeting with friends during times of limited social opportunities. This consolidates previous work on NGS as facilitating social connections within diverse communities as De la Barrera et al. (Citation2016) found users of NGS from three diverse neighbourhoods experienced better social relations in comparison to non-users. These findings ultimately reflect Bourdieu’s notion of social capital whereby access to a field (in this case NGS) facilitates the development of social capital for these participants. Individuals used NGS to maintain their social capital, particularly when it was difficult to do so through alternative avenues. Moreover, some of the participants discussed how being with others made them feel more comfortable in their use of NGS. This was particularly the case in more rural areas.

It just feels better to go with somebody else I think. Like, I go local exercising, but usually going far out would be with people, for the sights. (Amir)

If I went on my own it would be possible but I’d feel like if I went to … Malham cove on my own I wouldn’t enjoy it as much because I wouldn’t have people around me. But if I went to the park behind me, I’d be able to enjoy that by myself a lot more. (Aysha)

Fourteen participants discussed feeling more comfortable when visiting more rural NGS with others. These findings are reminiscent of the sense of awareness felt by Black communities in America, who are discouraged from travelling beyond their own communities due to fears associated with racial differences (Lee & Scott, Citation2017). Geographical distribution of NGS and who resides in those areas certainly influences the comfortability minority users experience when visiting NGS. As Edwards et al. (Citation2022) and Slater (Citation2022) also found, many South Asians will avoid visiting areas where they are underrepresented. This suggests a certain level of social capital is needed to access more rural NGS for South Asian Muslims. Indeed, when discussions arose about localised NGS, participants felt more comfortable visiting alone:

I can go myself and just sit there without thinking no one’s gonna say something. Like, it’s for everything and everyone. (Nabia)

Like if I’m walking kind of locally I’d just go by myself. (Roksana)

Nine participants discussed their preferences of visiting NGS alone at times. This is not an uncommon feature as 47% of the general population visit NGS alone (Colley & Irvine, Citation2018). The familiarity users have of their localised NGS may be associated with a sense of security and relaxation, allowing users to connect with nature in a safe and intimate setting. Of interest here, is how a number of the Muslim women chose to visit their localised NGS alone. This adds valuable insights to previous work on the role of Islamic beliefs on Muslim women’s PA choices and behaviours (Shakona et al., Citation2015) and joins previous work (Ahmad (Citation2020) to disrupt stereotypes around them being chaperoned to leave their homes. The participants’ independent choices in visiting NGS showcase their habitus, indicating their ability to overcome societal constraints linked to their cultural and gender identities. This aligns with Walseth’s (Citation2015) study on PA settings, which highlighted how individuals actively sought out NGS that both fulfilled religious needs and catered to their health requirements. Health was also a significant feature of the findings in this study.

Enhancing wellbeing in NGS

The participants’ choice of destination and companionship to NGS were influenced by their motivations. The drivers of engagement centred upon wellbeing as many visited these spaces to improve their mental health.

When no one else is available … I just feel like going to clear my mind. (Faheem)

It makes you feel like you’re getting away from this life … like having a break, or just sort of getting away from everything for a while and just empty your head from it all. (Amir)

Thirteen participants expressed that spending time in NGS positively impacted their mental health, while 18 participants highlighted these areas as fostering feelings of peace. Additionally, 20 individuals noted experiencing a sense of escapism from the noise, pollution, and busy urban routines while in these environments. Previous research reflects similar associations with NGS amongst the general population, where NGS is used to enhance mental wellbeing (Grant & Pollard, Citation2022). Usage of NGS leads to feelings of solitude, calmness, and provides an opportunity to be away from the stress and busy scheduling of urban life (Roe et al., Citation2017). It is important to note here that people from ethnic minority backgrounds face poorer mental health and access to mental healthcare, as well as more negative experiences with mental healthcare services (Bansal et al., Citation2022). As an alternative, NGS can be used as a catalyst for positive mental health behaviours, as shown in these extracts. The significant of this is underscored by Roe et al. (Citation2016) who reflected stronger mental wellbeing scores in minority individuals residing in areas with more NGS. To further understand how NGS can be used to support mental health for certain ethnic minority groups, the current study reflects how this was intertwined with the participants’ spirituality.

Because I’m a Muslim, it helps me to reconnect with God. I feel like natural greenspace its thing from God is kind of like a gift from God to us. And it’s where we’re meant to be, the countryside … you always have a craving for. … to me, God’s made that so that is a step closer to perfection … emotionally and spiritually I feel a lot more content and lighter when I visit NGS. (Sammy)

You can go there if you’re looking for a bit of peace … Yorkshire dales, go on a hike somewhere … when you’re there and it helps you to be a bit more spiritual. (Hasy)

Nine of the participants linked their wellbeing and engagement of NGS with spirituality. This provides a nuanced perspective perhaps different from the general population (De la Barrera et al., Citation2016). These participants’ motivations to connect with NGS were shaped by Islamic notions of the earth as God’s creation, leading them to value NGS as sites for spiritual contemplation and religious connection. Their moments of reflecting whilst in NGS strengthened their associations of wellbeing with these environments, leading to positive emotions from their visits. This insight offers a unique perspective regarding the relationship between NGS, spirituality and mental health, consolidating previous work on how levels of spirituality can strengthen wellbeing outcomes when engaging with NGS (Kamitsis & Francis, Citation2013). Relating this to the work of Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977), these findings reflect the participants’ habitus as inclined towards NGS as a means for positive mental health behaviours, shaped by their values around wellbeing, spirituality and NGS. This contradicts stereotypes that suggest South Asian Muslim people are irresponsible of their health, and instead positions them as active participants in their own care. Similar discussions involving physical wellbeing also emerged with the participants.

In this lockdown, I try to go out for like walks so in the park behind me, Dawson’s park, I’ll go walk for half an hour. (Aysha)

You, like, climb at the top [of the hill] and come back down, and I just go for like walks generally … you walk up, it’s got like pebbly stones kind of thing … At the top obviously it gets steeper … my friends and I’ll go for like health and fitness reasons. (Roksana)

So, what I do is start by walking for like a good 30 minutes. Then, when I find the spot where I’m most comfortable … then I start jogging. And then I start walking again and then jogging. So, like, stop and start. (Sabah)

These data contradict previous notions that depict South Asian communities as being disengaged from PA and adjoin work (Ahmad, Citation2020; Bhatnagar et al., Citation2016) to challenge previous notions of South Asian Muslim women being constrained by their community in accessing PA settings. Despite the stereotypes faced and challenges related to their identities, these participants reflect a habitus that values health and wellbeing, leading them to seek NGS as an environment conducive to their health. This study resonates with the work of Stride (Citation2016) in portraying South Asian Muslim individuals as active agents in identifying appropriate contexts for engaging in PA outside of competitive settings, sports-based activities, and traditional sports facilities.

Amongst the sample in this study, 17 participants described how visits to NGS encouraged them to engage in PA. These findings are unsurprising as NGS are known to prompt PA (Rigolon et al., Citation2021). This demonstrates the importance of promoting more informal contexts such as NGS for South Asian Muslims to participate in health-promoting activity, rather than focusing solely on more organised settings such as gyms and leisure centres (Houlihan & Green, Citation2009). Linking this to field, these individuals create a unique social space by redefining ideal places for PA, emphasising NGS as crucial for health activities. The flexibility NGS offers in terms of the ways it can be used, and its accessibility, ensures that NGS can be an effective resource in enabling PA opportunities and combatting some of the aforementioned health issues.

These findings, along with those of other studies (Grant & Pollard, Citation2022; Hordyk et al., Citation2015; Picavet et al., Citation2016), portray NGS as a common ideal setting to conduct PA. Individuals occupy NGS understanding that those environments provide opportunity to engage in PA, heightening the potential to increase stocks of physical capital – that is, their health and fitness (Shilling, Citation2004). In entering such spaces, users are led to invest in developing their physical capital through aligning to the practice of PA. For the participants in this study, this led to feel a sense of achievement that was different to other environments they visited.

The three peaks ‘cause the challenge side of it … I love the competitive side going up there, taking pictures of it … [so he can say] ’got the T shirt’ sort of thing. (Wakky)

Well, the Rock and Stones was more harder … outside is more like kind of ‘figure it out yourself’ and its more of a challenge, I would say, and when you complete it you get a better sense of achievement from it. (Amir)

At this point I’m on top of everyone, and that’s not even in an egotistical way but when you’re constantly putting yourself down you realise, like, okay now I’m at the top”. (Manny)

These data reflect the participants’ habitus as actively seeking out challenging situations to feel a sense of achievement. The pursuit of reaching certain heights or distances in NGS is not uncommon, seen as a personal challenge and a source of accomplishment for many users (Slater, Citation2022). These participants used their physical capital to acquire a form of symbolic capital – defined as a resource by virtue of one’s achievements (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation2013). Overcoming physical challenges in NGS developed the participants’ symbolic capital, enabling them to assert their capabilities and achieve a sense of accomplishment. Albeit these challenges were enabling, other forms of challenges were apparent in the participants’ experiences of NGS.

Challenges of accessing NGS

This final theme highlights the challenges participants faced in accessing and engaging in NGS. First, 16 participants discussed challenges in accessing NGS due to a lack of time and energy. These barriers were often attributed to work commitments.

I’d say mainly, majority, like the commitment to work. Like, I’ll work, right? And then I’d be tired, I’ll be too like tired or lazy to do anything else. Like, on my days off,… I don’t do it as much on my days off either, but I’ll try to, but I say the main thing is work. (Sany)

The only challenge would be finding time to go in between work schedule. (Asad)

The participants’ employment situations emphasise the influence of economical capital on their ability to access NGS. Economic capital is a direct and powerful resource valued in most social contexts as it enables access to resources (Bourdieu, Citation1984). The current study reflects how a lack of economical capital acts as a barrier in accessing NGS and the benefits it affords. Individuals worked extended hours, leaving them with little time to visit NGS. When they were not working, their labour commitments left them feeling too fatigued to visit NGS. Ethnic minority groups, particularly South Asians, often face economic disparities, and greater financial hardships compared to their White counterparts, limiting opportunities for PA (Eyre et al., Citation2015; Stone et al., Citation2018). Although NGS are generally free to access, engagement is also influenced by other factors including transport costs and travel time. Ethnic minority groups are known to live in areas that contain less NGS in comparison to areas resided in by their White counterparts, forcing them to travel longer distances in order to access them (Phillips et al., Citation2022). These findings align with sociodemographic factors that influence the engagement of wider leisure pursuits and PA (Abdulwasi et al., Citation2018). However, these challenges are exacerbated for women who also highlighted their home commitments as obstacles to their engagement with NGS.

I’ll probably say if I’m busy with something else, you know, if I’ve got something else on my mind, or that needs doing, then I’d probably just get that done. Obviously, though, that doesn’t really occur to me at that point. (Haaniya)

It can be a busy schedule, I can have loads of chores at home. it can also be your own self, sometimes you just feel lazy. (Aysha)

It is important to note that women in general, regardless of their specific cultural or religious backgrounds, often face similar challenges in relation to domestic responsibilities. Slater (Citation2022) noted how home related commitments influence different women’s engagement with NGS. This reflects the ongoing gendered nature of household duties, rather than cultural or religious reasons, which affects women’s ability to visit NGS. Linking this to habitus (Bourdieu, Citation1990), the prioritising of home commitments reflects ingrained dispositions towards domestic responsibilities dictating women’s roles in caretaking for their families, subsequently limiting their time for leisure. Taking into account the participants’ preference for NGS as a social activity venue, individuals could engage in leisure and PA whilst being accompanied by their families, helping to mitigate their family commitments (Slater, Citation2022). To achieve this, spaces must be welcoming and family friendly. However, the presence of uncontrolled dogs and antisocial behaviour inhibited some of the participants’ ability to use NGS comfortably.

I’m not prejudiced towards dogs, I just don’t like them. … I just don’t like them going near me. (Bilal)

I usually avoid the local parks (chuckles)… I think it’s because people use parks as, not as parks, but as other forms of activity. (Nash)

Like if you go by yourself early in the morning or in the evening or whatever, you don’t know what can happen because there’s always guys around and stuff, and you just feel intimidated. (Nabia)

It can be used for people to obviously do their own sort of stupid activities so they might take a motor bike out there, you know, riding it about and it can be dangerous sometimes because obviously there’s kids there. (Hammy)

It was clear from these findings that whilst some NGS spaces have been designated to be used in particular ways, this is often open to interpretation. Indeed in some NGS, conflicting behaviours and perceptions created challenges for some users. Bourdieu (Citation1990) concept of hysteresis is useful to understand the disconnect and mismatch between the participants’ habitus and the practices of the field. For instance, when parks are used for particular activities that contradict the traditional, often taken for granted practices, this forms a disconnect between people’s expectations of behaviour in these spaces and what actually occurs (Hardy, Citation2014). This can cause individuals to reconsider their perception of the field which, in some instances, leads to disengagement from that space. In the current study this led to varied reactions by the participants. For example, for Nash and Nabia, a combination of antisocial behaviour and the presence of groups of men influenced when and where they engaged with their local park. This resonates with previous findings which demonstrate how most women must navigate public spaces around concerns for safety (Green & Singleton, Citation2016). For the participants of the current study, fears were compounded by the visibility of their gendered, religious and cultural identities. The risks for Muslim women can be multi-layered because of their positioning at these intersections. For example, risk of physical harm can be coupled with verbal abuse and a questioning of their religious identity. These issues were more prevalent in discussions of their experiences of rural NGS.

Clothing is very important … A lot of times as a South Asian … woman, I feel like I wear the wrong clothes and that’s what deters me. (Anya)

It happens a lot to be honest and that’s simply because we are covered like … she was literally pointing and laughing at me because I had like full sleeves and leggings … that made us so angry. (Sophia)

The cafe owner and my Aunties … there was a bit of confrontation between them. They [café owner] said something racist to them [aunty]. They were wearing the hijab and they said something to them. My aunty confronted them and it all escalated from there, so that was like a bad experience. (Sany)

These interactions depict how NGS is still demarcated as a White, male and middle-class space, excluding those who identify differently (Edwards et al., Citation2022; Kloek et al., Citation2017; Stone et al., Citation2018). The doxa in NGS – taken for granted assumptions of the field (Bourdieu, Citation1990) – are driven by ideas of gender and race. The valued capital in NGS are shaped by such doxa, and the participants highlight the importance of acquiring capital that aligns with the field in question, and the consequences of holding misaligned capital (Lee & Scott, Citation2016). In choosing to express their religious beliefs, particularly through their attire in NGS, these women faced an increased risk of abuse. This was due to their visibility as being misaligned with the field, evident when wearing Islamic head coverings. The challenges faced by South Asian Muslim women are additional to those encountered by the general population (Daniel et al., Citation2018; Rigolon et al., Citation2021; Slater, Citation2022). These identity related struggles are documented in research of Muslim women in broader Western PA contexts (Soltani, Citation2021), and are highlighted further in this context of NGS.

Conclusion

In this study, Bourdieu and Passeron's (Citation1977) notion of field was used to understand NGS as a social space that is defined by the existence of natural features. The availability and proximity to NGS influenced the preferences, practice and perceptions the participants had of such spaces, reflecting their habitus. The concept of capital was then used to explore the motives and challenges for engaging with NGS. For instance, localised NGS were used to manage and maintain social capital, especially at the time of this study (COVID-19 pandemic), where NGS was one of the few avenues where individuals could legitimately meet. In other ways, the accrual of physical capital was important in the participants’ motivations for using NGS. A lack of economical capital challenged access to NGS indirectly as people were left with a lack of time and energy due to labour commitments. This Bourdieusian approach to exploring behaviours in NGS signals opportunities for researchers wishing to explore social behaviour in different types of settings.

Leading on from this, this study reflected how NGS was conducive to physical and mental health enhancing activity, partly due to its free access, flexibility and convenience. This demonstrates the importance of more informal contexts such as NGS in supporting participation of health-promoting activity. This is particularly significant for those populations who currently experience disproportionate ill health in comparison to the general population, and those for whom the cost of gym membership or entry to leisure settings acts as a barrier. Of particular note in this study, is the ways in which the participants found a connection between NGS and their wellbeing through their Islamic beliefs, leading them to seek moments of reflection. This signals opportunities for further research to explore the role of religious spirituality within NGS and how this influences engagement and practice in this space for minority communities.

The findings of this study are significant for policy makers and practitioners tasked with improvement of public health, who must consider how these kinds of spaces can be best promoted to underrepresented groups. Policy makers should invest in targeted campaigns and community initiatives aimed at fostering awareness and facilitating access to NGS, particularly for those with distinct health needs. For example, wider South Asian Muslim communities could be encouraged to engage with NGS in ways to help combat current mental health disparities. Policy can work to organise activities in NGS such as health workshops, nature walks, and outdoor fitness sessions that are culturally sensitive and religiously linked, showcasing the value of NGS to spiritual and emotional wellbeing. Similarly, the participants of this study used NGS in various ways including to socialise, independent time, and adventurous activity. Such diverse ways of engagement should be recognised by urban planners and site management so that activities, spaces and facilities can be designed accordingly to accommodate a variety of users. For instance, NGS could be designed to contain large open spaces, communal areas exercise machines, benches, and paths to ensure they are welcoming to users who enjoy nature based, physical or social activity.

Leading on from this, there was an appeal for the participants to visit both local and more rural NGS, reflecting the importance of offering a range of options. NGS should be better distributed in urban spaces, particularly for disadvantaged groups to improve access. Additionally, transport needs to be made available for visits to more rural areas. Making more NGS available – urban and rural – will help to facilitate engagement for a broader range of users including those from the South Asian Muslim community. However, it is important to acknowledge that this recommendation is made tentatively as local councils in England are reducing their investment in leisure services.

An important lesson from this research is to consider how study participants understand and contextualise their own experiences of NGS, as this influences what they choose to share about their engagement. If NGS is defined in narrow ways by policy makers then this may lead to a failure in accurately recording engagement with NGS, contributing to fallacious stereotypes regarding the (dis)engagement of ethnic minority groups. Instead, these participants demonstrated a positive relationship with NGS and articulated clear reasons for their engagement. Building on this, there is a need to challenge stereotypes that South Asian Muslims are unconcerned about their health. Shifting the blame away from individuals and redirecting it towards governmental institutions is crucial to facilitate access. An initial step in this direction is to deconstruct notions that NGS belong to a certain demographic. Policies on access to NGS should advocate for increased diversity in representation within NGS. This could be achieved by increasing awareness of the various dress codes, religious and cultural practices to cultivate safe and inclusive spaces for all users.

It was important to identify the challenges faced by the participants when accessing NGS in order to help create more inclusive contexts. It was particularly challenging for participants who were positioned at the intersections of being South Asian, Muslim and female to engage with NGS. Their physical capital, in the form of religious clothing, was deemed incompatible to those fields, leading some women to withdraw from using more rural NGS for fear of abuse. These findings demonstrate how people can experience NGS differently as a result of their multiple and intersecting identity markers, and demonstrates how the demarcation of more rural NGS have led South Asian Muslim users to only visit when they have a certain level of social capital. This study therefore draws attention to the social injustices that exist as a result of one’s identity, and justifies the need to further investigate how race, religion, gender, and space intersect to create different kinds of challenges for South Asian Muslim women. Future research should focus on South Asian Muslim women’s experiences in the context of rural NGS to allow for a more elaborate insight of how the intersections of identity and space shape one’s engagement of NGS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Hamza

Mohammed Hamza is a lecturer and PhD researcher in Social Science and Education. His interdisciplinary research interests revolve around access to and utilisation of green spaces for health enhancing activity.

Annette Stride

Annette Stride is a Reader in Physical Education, Sport and Social Justice. Her research focuses upon issues of gender and how this intersects with other social locations to influence the PE and sporting experiences of different women and girls.

Thomas Quarmby

Thomas Quarmby is a Reader in Physical Education (PE) and Sport Pedagogy. His research focuses on the role and value of PE and sport for youth from socially vulnerable backgrounds (including care-experienced young people), and trauma-aware pedagogies in PE.

Notes

1. NGS encompasses a variety of spaces that can often be referred to with different names such as the outdoors, green spaces and the natural environment. Although a definition is provided as to what NGS refers to within this paper, understandings can vary. As such, we consider the participants’ perspectives later on in the study as an important factor in exploring experiences of NGS.

2. Ethical approval was granted by the Leeds Beckett University Ethics Committee.

3. A pseudonym is used for the name of the city and the research participants to protect anonymity.

References

- Abdulwasi, M., Bhardwaj, M., Nakamura, Y., Zawi, M., Price, J., Harvey, P., & Banerjee, A. T. (2018). An ecological exploration of facilitators to participation in a mosque-based physical activity program for South Asian Muslim women. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 15(9), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2017-0312

- Ahmad, F. (2020). Still’in Progress?‘–methodological dilemmas, tensions and contradictions in theorizing South Asian Muslim women 1. In N. Puwar & P. Ranghuram (Eds.), South Asian women in the diaspora (pp. 43–65). Routledge.

- Avery, E. E., Baumer, M. D., Hermsen, J. M., Leap, B. T., Lucht, J. R., Rikoon, J. S., & Wilhelm Stanis, S. A. (2020). Measuring place of residence across urban and rural spaces: An application to fears associated with outdoor recreation. The Social Science Journal, 59(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2019.08.007

- Banga, Y., Azhar, A., Sandhu, H., & Tang, T. S. (2020). Dance dance “cultural” revolution: Tailoring a physical activity intervention for south Asian children. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(2), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-019-00921-6

- Bansal, N., Karlsen, S., Sashidharan, S. P., Cohen, R., Chew-Graham, C. A., & Malpass, A. (2022). Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: A meta-ethnography. PloS Medicine, 19(12), e1004139. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004139

- Benn, T., Dagkas, S., & Jawad, H. (2011). Embodied faith: Islam, religious freedom and educational practices in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 16(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.531959

- Benn, T., & Pfister, G. (2013). Meeting needs of Muslim girls in school sport: Case studies exploring cultural and religious diversity. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(5), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.757808

- Bhatnagar, P., Townsend, N., Shaw, A., & Foster, C. (2016). The physical activity profiles of South Asian ethnic groups in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(6), 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206455

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Espace social et genèse des“classes”. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 52(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1984.3327

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The force of law: Toward a sociology of the juridical field. Hastings LJ, 38(5), 805.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford university press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, society and culture. Trans. Richard Nice. In M., Featherstone (Ed.), Foundations of a Theory of Symbolic Violence (pp. 15–29). SAGE Publications.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (2013). Symbolic capital and social classes. Journal of Classical Sociology, 13(2), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X12468736

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Colley, K., & Irvine, K. N. (2018). The James Hutton Institute. Social, Economic & Geographical Sciences Group. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/Fullreport-use-of-the-outdoors.pdf

- Daniel, M., Abendroth, M., & Erlen, J. A. (2018). Barriers and motives to PA in South Asian Indian immigrant women. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(9), 1339–1356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945917697218

- De la Barrera, F., Reyes-Paecke, S., Harris, J., Bascuñán, D., & Farías, J. M. (2016). People’s perception influences on the use of green spaces in socio-economically differentiated neighborhoods. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 20, 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.09.007

- Edwards, R. C. (2021). Exclusive nature: Exploring access to protected areas for minority ethnic communities in the United Kingdom. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/17416

- Edwards, R., Larson, B., & Burdsey, D. (2022). What limits Muslim communities’ access to nature? Barriers and opportunities in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(2), 880–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221116737

- Emadian, A., & Thompson, J. (2017). A mixed-methods examination of physical activity and sedentary time in overweight and Obese South Asian men living in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040348

- Eyre, E. L. J., Duncan, M. J., Birch, S. L., Cox, V., & Blackett, M. (2015). Physical activity patterns of ethnic children from low socio-economic environments within the UK [article]. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.934706

- Ferguson, M., Roberts, H. E., McEachan, R. R. C., & Dallimer, M. (2018). Contrasting distributions of urban green infrastructure across social and ethno-racial groups [article]. Landscape and Urban Planning, 175, 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.03.020

- Fernández-Balboa, J.-M., & Muros, B. (2006). The hegemonic triumvirate—ideologies, discourses, and habitus in sport and physical education: Implications and suggestions. Quest, 58(2), 197–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2006.10491879

- Fletcher, T. (2014). ‘Does he look like a Paki?’an exploration of ‘whiteness’, positionality and reflexivity in inter-racial sports research. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 6(2), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.796487

- Gentin, S., Pitkänen, K., Chondromatidou, A. M., Præstholm, S., Dolling, A., & Palsdottir, A. M. (2019). Nature-based integration of immigrants in Europe: A review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 43, 126379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126379

- Grant, G., & Pollard, N. (2022). Health group walks: Making sense of associations with the natural landscape. Leisure Studies, 41(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1971284

- Green, E., & Singleton, C. (2016). Safe and risky spaces: Gender, ethnicity and culture in the leisure lives of young south Asian women geographies of Muslim identities. Routledge.

- Hamdonah, Z. (2022). Racialized women in sport in Canada: A scoping review. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 19(12), 868–880. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2022-0288

- Hamzeh, M. Z., & Oliver, K. (2010). Gaining research access into the lives of Muslim girls: Researchers negotiating muslimness, modesty, inshallah, and haram. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390903120369

- Hardy, C. (2014). Hysteresis Pierre Bourdieu. Routledge.

- Hordyk, S. R., Hanley, J., & Richard, É. (2015). “Nature is there; its free”: Urban greenspace and the social determinants of health of immigrant families. Health & Place, 34, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.016

- Houlihan, B., & Green, M. (2009). Modernization and sport: The reform of sport England and UK sport. Public Administration, 87(3), 678–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01733.x

- Iliodromiti, S., Ghouri, N., Celis-Morales, C. A., Sattar, N., Lumsden, M. A., Gill, J. M., & Taheri, S. (2016). Should physical activity recommendations for South Asian adults be ethnicity-specific? Evidence from a cross-sectional study of South Asian and White European men and women. Public Library of Science ONE, 11(8), e0160024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160024

- Kamitsis, I., & Francis, A. J. (2013). Spirituality mediates the relationship between engagement with nature and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.013

- Kloek, M. E., Buijs, A. E., Boersema, J. J., & Schouten, M. G. C. (2017). Beyond ethnic stereotypes – identities and outdoor recreation among immigrants and nonimmigrants in the Netherlands. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1151843

- Lee, K. J., & Scott, D. (2016). Bourdieu and African Americans’ park visitation: The case of Cedar Hill State Park in Texas. Leisure Sciences, 38(5), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2015.1127188

- Lee, K. J., & Scott, D. (2017). Racial discrimination and African Americans’ travel behavior: The utility of habitus and vignette technique. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516643184

- Liu, H., Chen, X., & Zhang, H. (2021). Leisure satisfaction and happiness: The moderating role of religion. Leisure Studies, 40(2), 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1808051

- Mahmood, B., Bhatti, J. A., Leon, A., & Gotay, C. (2019). Leisure time physical activity levels in immigrants by ethnicity and time since immigration to Canada: Findings from the 2011–2012 Canadian community health survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(4), 801–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0789-3

- Maton, K. (2014). Habitus Pierre Bourdieu. Routledge.

- Morris, S., Guell, C., & Pollard, T. M. (2019). Group walking as a “lifeline”: Understanding the place of outdoor walking groups in women’s lives. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112489

- Natural England. (2017). Visits to the Natural Environment (https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/culture-and-community/culture-and-heritage/visits-to-the-natural-environment/latest

- Natural England. (2019). Monitor of Engagement With the Natural Environment Children and Young People Report (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/828838/Monitor_of_Engagement_with_the_Natural_Environment__MENE__Childrens_Report_2018-2019_rev.pdf

- Phillips, A., Canters, F., & Khan, A. Z. (2022). Analyzing spatial inequalities in use and experience of urban green spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 74, 127674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127674

- Picavet, H. S. J., Milder, I., Kruize, H., de Vries, S., Hermans, T., & Wendel-Vos, W. (2016). Greener living environment healthier people?: Exploring green space, physical activity and health in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Preventive Medicine, 89, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.021

- Ratna, A. (2017). Walking for leisure: The translocal lives of first generation Gujarati Indian men and women. Leisure Studies, 36(5), 618–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1285952

- Rigolon, A., Browning, M. H., McAnirlin, O., & Yoon, H. (2021). Green space and health equity: A systematic review on the potential of green space to reduce health disparities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052563

- Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M., & Jones, A. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098

- Roe, J., Aspinall, P. A., & Thompson, C. W. (2016). Understanding relationships between health, ethnicity, place and the role of urban green space in deprived urban communities [article]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(7), 681. Article 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070681

- Roe, J. J., Aspinall, P. A., & Ward Thompson, C. (2017). Coping with stress in deprived urban neighborhoods: What is the role of green space according to life stage? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1760. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01760

- Shah, A., & Kanaya, A. M. (2014). Diabetes and associated complications in the South Asian population. Current Cardiology Reports, 16(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-014-0476-5

- Shakona, M., Backman, K., Backman, S., Norman, W., Luo, Y., Duffy, L., Reisinger, Y., & Moufakkir, O. (2015). Understanding the traveling behavior of Muslims in the United States. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2014-0036

- Shilling, C. (2004). Physical capital and situated action: A new direction for corporeal sociology. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 473–487.

- Slater, H. (2022). Exploring minority ethnic communities’ access to rural green spaces: The role of agency, identity, and community-based initiatives. Journal of Rural Studies, 92, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.03.007

- Soltani, A. (2021). Hijab in the water! Muslim women and participation in aquatic leisure activities in New Zealand: An intersectional approach. Leisure Studies, 40(6), 810–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1933143

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2013). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Stone, G. A., Gagnon, R. J., Garst, B. A., & Pinckney, H. P. (2018). Interpreting perceived constraints to ethnic and racial recreation participation using a recreation systems approach. Loisir et Société/Society & Leisure, 41(1), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2018.1438135

- Stride, A. (2016). Centralising space: The physical education and physical activity experiences of South Asian, Muslim girls [article]. Sport, Education and Society, 21(5), 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.938622

- Taylor, L., & Hochuli, D. F. (2017). Defining greenspace: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.024

- Walseth, K. (2015). Muslim girls’ experiences in physical education in Norway: What role does religiosity play? Sport, Education and Society, 20(3), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.769946