ABSTRACT

The shift towards local food consumption is creating new opportunities for regional food destinations. The growing market segment of ‘food day-trippers’ who travel to nearby destinations to experience local cuisine has elevated this trend. In response, destination marketers increasingly use local cuisine to enhance destination attractiveness and to create regional food hubs. Yet, it is unclear what attracts food day-trippers to these destinations. This paper explores destination attributes that represent regional food destination attractiveness and presents personal values that shape those attribute preferences. The Repertory Test and Laddering Analysis explore these connections, providing valuable insights into perceptual orientations influencing travel choices within this context. Supported by distance decay theory, findings show that despite the common proposition prioritising food-related attributes in food destination marketing, proximity and non-food attributes also appear important. Underlined by personal values such as a sense of security, these attribute preferences demonstrate food day-trippers’ tendency to look for novelty in food experiences rather than in the location. Practically, these insights highlight an opportunity to capitalise on repeat visitation and aid destination marketers in revisiting their value propositions to include elements that go beyond food.

Introduction

An attribute that has long gained recognition as a destination brand differentiator is cuisine (Lai et al., Citation2017). Extensive research consistently highlights the benefits of food tourism and its potential to impact various aspects of a traveller’s journey (e.g. Lyu et al., Citation2020; Stone et al., Citation2018). From the theoretical perspective of leisure, these benefits could arise from casual pursuits, such as dining out for immediate pleasure, or more serious pursuits, such as participating in cooking classes that require skills and dedication (Dimitrovski et al., Citation2021; Veal, Citation2017; Williamson & Hassanli, Citation2020). As such, the benefits of food tourism extend beyond being a ‘spare time’ activity (Cleave, Citation2020; Stebbins, Citation2005) to an experience that allows for cultural exploration, a deeper understanding of heritage, the enjoyment of authentic cuisine, and the fostering of a sense of belonging through support for local food establishments (Karsten et al., Citation2015; Tsai, Citation2016; Xueling et al., Citation2023). From a marketing perspective, food tourism presents opportunities for destination marketing organisations (DMOs) to capitalise on unique regional offerings, thereby contributing to the economic growth of local communities through leisure consumption spaces. Recognising this potential, an increasing number of DMOs are emphasising food-related attributes, with a focus on local cuisine as a key attraction (Ab Karim & Chi, Citation2010; Lyu et al., Citation2020).

Despite this attention, the shifting preferences of today’s travellers raise doubts about the effectiveness of relying on food-related attributes for promoting food destinations (Dimitrovski et al., Citation2021; Manimont et al., Citation2022). This approach carries the risk of falling into repetitive tactics with an overdependence on a singular destination attribute (Pike & Kotsi, Citation2020). Furthermore, concerns are raised around practical considerations, including factors such as time (Botti et al., Citation2008; Pearce, Citation2020) and distance (Kah et al., Citation2016; Wynen, Citation2013) which affect travellers’ interest in, and enthusiasm for, food experiences (Robinson et al., Citation2018). This concern directs attention to shifting consumer priorities when considering growing travel trends such as food day-tripping (Manimont et al., Citation2022).

Originating from the concept of day-tripping, food day-tripping is a trend in which individuals take shorter trips to nearby destinations within their surrounding region to explore local cuisine (Manimont et al., Citation2022; Nicolau et al., Citation2023). This trend gained considerable attention from DMOs, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited travel options for many people (Fountain, Citation2022; Paul et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2022). While time and distance considerations persist even in the absence of a pandemic, the unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic intensified these constraints (Luković et al., Citation2023). International travel restrictions saw a shift in destination strategies, reinforcing the enduring relevance of local and community-centric initiatives within the broader travel landscape (Lebrun et al., Citation2021).

Given this development, the potential for local cuisine to enhance destination attractiveness has heightened. However, for food day-trippers, proximity and time constraints demand sacrifices (Manimont et al., Citation2022; Mckercher & Lew, Citation2003; Wang et al., Citation2022). Consequently, other destination attributes may take precedence over food-related attributes. This raises the need to revisit earlier propositions regarding the use of local cuisine as an overarching means of differentiation. Considering the emergence of food day-trippers that coincides with destinations’ reliance on local and community-centric initiatives in recent years, further exploration is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of what attracts food day-trippers to regional food destinations – an area which remains unexplored in existing literature.

This paper investigates regional food destination attractiveness and how regional food destination attributes connect back to food day-trippers’ lifestyles to gain knowledge of this growing market segment’s preferences. This comprehension is vital as capturing travellers’ Top-of-Mind (ToM) awareness comes from a deep understanding of the target market’s travel preferences, including attributes perceived as salient for their visit (Stepchenkova & Li, Citation2014). A personal values lens is utilised for this, as it provides insights into individuals’ priorities in life, thereby providing a justified explanation of their preferences. Previous research shows that personal values drive food tourists’ behaviour (e.g. Stone et al., Citation2018). As food day-trippers are a sub-category of food tourists, an in-depth exploration into regional food destination attractiveness using personal values would help comprehend nuances that differentiate them as a distinct market segment.

This paper’s objectives are, first to explore salient destination attributes that represent regional food destination attractiveness from the food day-tripper perspective. Second, to identify perceptual orientations that demonstrate food day-trippers’ behaviour by exploring personal values that shape destination attribute preferences. Investigating these connections using Repertory Test and Laddering Analysis, provides insights into perceptual orientations that guide the travel choices of food day-trippers when considering regional food destinations.

Additionally, using distance decay theory, this paper clarifies food day-trippers’ thinking patterns to explain their uniqueness as a travel segment. This distinct understanding is important as destination attributes and values influence travellers’ behavioural outcomes in food tourism settings. Practically, the knowledge of destination attributes considered salient for food day-trippers will help destination marketers and food establishments improve their marketing campaigns and revisit value propositions going beyond the myopic practice of focusing on food. Overall, these findings and implications help progress regional food destination positioning, so attracting repeat visitation.

Study context and area

The context of this study is regional food destinations in the UK. The term ‘regional’ emphasises the localised nature of travel experiences (Yang & Fik, Citation2014), and acknowledges that food is not a uniform concept. This recognition is crucial for understanding the diversity within food tourism, and appreciating the cultural and geographical nuances that shape distinct gastronomic identities. Thus, the exploration of regional food destination attractiveness is inherently contextual, recognising that food plays an important role in shaping the overall traveller experience (Rousta & Jamshidi, Citation2020). This, in turn, becomes a reflection of the essence of a place. The emphasis on ‘regional’ adds depth, authenticity, and a sense of place to the culinary narrative of a destination, making it a crucial and strategic choice in destination marketing. Despite the nuances that persist within food tourism, limited research investigates regional food destinations. Studying this context helps gain insights into how local cuisine can be strategically leveraged for tourism development (Calero & Turner, Citation2019).

The current research focuses on Dorset and Hampshire in southern England, an area of 2,479 miles2 (Population Data UK, Citation2023), often presented as sister counties in promotional efforts by DMOs. Dorset, with its picturesque countryside and coastline, offers a diverse range of food experiences. Seafood plays a prominent role in Dorset cuisine given its long coastline, with towns like Lyme Regis being renowned for their seafood offerings. Dorset’s agriculture sector excels in producing high-quality local dairy products, award-winning cheeses, and traditional ciders (Dorset, Citation2023a). Dorset’s neighbour Hampshire also has a fascinating culinary history. The county is known for its agriculture and farming, benefiting from fertile farmland and vineyards. Hampshire is particularly famous for its Hampshire breeds of pork and lamb, and the rearing of free-roaming livestock in the New Forest (Hampshire, Citation2023). The choice of Dorset and Hampshire is driven by their prominence, collaborative marketing efforts, and the rich culinary experiences they offer.

Literature review

Food destination attractiveness

Destination attractiveness and destination image are closely related concepts that reinforce each other (Gartner, Citation1993; Gordin & Trabskaya, Citation2013). Destination attractiveness captures how individuals perceive and respond to a destination’s ability to fulfil specific travel needs based on a range of destination attributes (Pike et al., Citation2021). While it considers the actual travel experience, pre-visit destination attractiveness is a function of traveller perceptions (Alahakoon et al., Citation2021b). This has led to the recognition of destination image in influencing destination attractiveness, partly due to the intangibility of travel experiences. Destination image refers to mental shortcuts that individuals form about a destination, drawing upon their beliefs formed from promotional materials as well as personal experiences (Hunt, Citation1975; Tasci & William C, Citation2007). Destination image has the potential to influence perceived attractiveness, which in turn, can affect travellers’ decisions and behaviours.

Food shapes food tourists’ destination choice preferences (Andersson & Mossberg, Citation2016), with many DMOs and destinations promoting local cuisine as a major attraction (Ab Karim & Chi, Citation2010; Lai et al., Citation2017). Studies on destination image have specifically explored the connection between food and destination attractiveness. These studies highlight that attributes such as local cuisine, local food markets and festivals, vineyards, and cultural heritage enhance destination attractiveness (e.g. Dimitrovski et al., Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2019). Emerging trends such as farm-to-fork experiences and support for local producers (Lyu et al., Citation2020; Okumus et al., Citation2018) reinforce the idea that cuisine continues to drive destination attractiveness.

Despite this sustained popularity, there is a need to expand understanding and knowledge in this area, given the emergence of new markets and the dynamic nature of travel preferences. Such change is partly due to motivations that may have evolved over time (Dimitrovski et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2022). More specifically, within food tourism, motivations towards local cuisine consumption remain contested given the role non-food-related considerations such as travel distance, duration, and time play in travellers’ decisions (Manimont et al., Citation2022) warranting further study into contemporary food destination attractiveness.

Proximity tourism

Consumer behaviour tends to be guided by rationality, involving the evaluation of costs, benefits, and personal preferences (Nicolau et al., Citation2023; Suriñ et al., Citation2017). Similar to other consumers, food day-trippers may consider adopting a rational approach, seeking to maximise the benefits of their actions before committing to travel to a destination. This rational approach extends to various decision-making processes, including destination selection, restaurant choice, and the allocation of time and resources. While emotional elements may also influence their decisions (Mayo & Jarvis, Citation1981), it is reasonable to assert that rationality significantly shapes the choices made by food day-trippers, particularly when time and distance are key factors shaping their preferences when travelling for food experiences. This rational consideration contributes to the distinctive nature of their travel choices and enhances the overall understanding of their preferences in the context of food tourism.

Travel situation influences destination choice and shapes travel experiences, yet has received limited attention in existing literature, especially concerning food destinations (Herington et al., Citation2013; Huang et al., Citation2013; Kah et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2022; Wynen, Citation2013). One such travel situation is proximity tourism, which suggests that destinations geographically closer to the traveller’s origin, such as their current residency or country of origin, tend to be more attractive for specific types of travel (Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2016). Preference for proximity is influenced by convenience and the desire to maximise limited leisure time (Cleave, Citation2020; Diaz-Soria, Citation2016; Williamson & Hassanli, Citation2020). Familiarity as a result of previous visits (Tan & Wu, Citation2016), cultural knowledge (Huang et al., Citation2013), and media representations (Garay Tamajón & Cànoves Valiente, Citation2015) also push travellers towards geographically closer destinations.

Studies examining the attractiveness of domestic short-haul destinations provide evidence that travel distance greatly impacts travel decisions and subsequent behaviours, resulting in a higher frequency of travel to near-to-home destinations (Pike, Citation2009). The perceived convenience of shorter travel distances leads to a greater likelihood of choosing nearby destinations, as the ease of reaching these destinations reduces travel barriers, motivating individuals to opt for shorter trips (Wang et al., Citation2022). Such advantages result in a re-evaluation of salient destination attributes and locational considerations when confronted with time constraints (Diaz-Soria, Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2012; Pearce, Citation2020). A theory underlying proximity tourism is distance decay theory, a geographical concept positing that the attractiveness of a destination gradually decreases as the physical distance and time required to reach it increases (Eldridge & Jones, Citation1991; Lee et al., Citation2012). This proposition aligns with research on value propositions but goes beyond the issue of physical distance alone (Mckercher & Lew, Citation2003). It encompasses a broader perspective that involves weighing the cognitive trade-offs between the benefits (consequences) and sacrifices associated with travelling to a specific destination. The perceived value of the destination experience, along with its alignment with personal preferences and expectations, becomes crucial in determining the perceived cost of travel and the subsequent decision to invest in leisure travel expenses (Hooper, Citation2015).

When applying the proposition of distance decay theory to food destination attractiveness, consumers may place greater importance on non-context-specific destination attributes (e.g. accessibility, infrastructure) compared to context-specific attributes (e.g. local cuisine, speciality food) because, in some travel situations, only a few ‘salient’ attributes hold significant weight in destination choice (Manimont et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2018). However, research is scarce on this topic in relation to regional food tourism, specifically in terms of addressing the preferences of food day-trippers who are constrained by travel time and distance. As reliance on generic attributes may result in a false sense of destination attribute salience, impacting promotional effectiveness (Alahakoon et al., Citation2021a; Pike & Kotsi, Citation2018), exploring context-specific destination attributes is important.

Personal values

Personal values serve as guiding principles in individuals’ decision-making processes (Ye et al., Citation2019). They are useful for understanding underlying motivations and reasons behind individuals’ lifestyle choices, which subsequently influence their travel behaviour (Alahakoon et al., Citation2021b; Kotsi & Pike, Citation2020). One of the earliest studies on values within travel presents three US outbound leisure traveller segments labelled ‘security-conscious’, ‘fun and enjoyment-oriented’, and ‘experience-based’ (Muller, Citation1991). These segments exhibited varying value orientations, focusing on security, excitement, or warm relationships. These value orientations, in turn, explained specific reasons for travellers’ attribute preferences. More recent studies by Chan et al. (Citation2022) and Kim et al. (Citation2022), demonstrated this connection between personal values and attribute preferences in the context of food consumption. Chan et al. (Citation2022) studied personal values associated with fast food consumption, while Kim et al. (Citation2022) explored values related to local food consumption among various inbound cultural groups. These studies emphasise the important role personal values play in shaping consumer preferences within food consumption, justifying the use of a personal values lens to explore attribute preferences of food day-trippers.

Contextually, existing literature lacks an explanation of attribute preferences and value orientations of food day-trippers, who rely on local knowledge but are constrained by limited time and distance. To address this gap, further research is necessary to investigate the value orientations of food day-trippers to help comprehend underlying reasons for their destination attribute preferences.

Methodology

Research approach

To explore food day-tripper preferences in the context of regional food destinations, a qualitative research design with the Repertory Test technique with Laddering Analysis was adopted, closely aligning with the methods used by Alahakoon et al. (Citation2021b) and Pike (Citation2012).

Repertory testwith laddering analysis

The Repertory Test has its theoretical foundations in Personal Construct Theory (PCT). First introduced by Kelly (Citation1955), PCT assumes alternate constructions whereby individuals keep revising their interpretations of the environment. Based on this assumption, PCT presents the notion that individuals like ‘scientists’ create ways of seeing the world and test them as they progress through life. These ways of seeing are labelled as constructs, defined as how ‘some things are construed as being alike and yet different from others’ (Kelly, Citation1991, p. 74). Constructs are subjective, and finite in number, but coincide with other constructs allowing for commonalities. It is these propositions that allow the aggregation of attributes elicited through the Repertory Test to conclude food day-trippers’ destination attributes (i.e. constructs), in the case of this paper. Application of the Repertory Test to food tourism is scarce but has previously been used to study motivational factors (Mak et al., Citation2013) and image attributes (Chang & Mak, Citation2018). These studies show the applicability of the Repertory Test to food tourism, but there remains a notable gap in research, particularly in exploring the contemporary behaviours of food travellers.

Laddering Analysis serves as a useful add-on to the Repertory Test to understand reasons for individuals’ attribute preferences in that it links attributes to individuals in a systematic approach, establishing meaningful links between them (Reynolds & Gutman, Citation1988). First introduced by Hinkle (Citation1965), it takes a similar approach to marketing literature’s means-end theory (Gutman, Citation1982). As one of its main outputs, Laddering Analysis presents Hierarchical Value Maps (HVMs), building links between attributes, consequences, and values, highlighting perceptual orientations within a consumption context (Reynolds & Gutman, Citation1988). Laddering Analysis has been applied to food tourism to understand culture-based influences on food preferences (Kim et al., Citation2022), fast-food preferences (Chan et al., Citation2022) and food cultural inheritance (Lee et al., Citation2018). Personal values are conceptualised using a selection of items that outline individuals’ priorities in life, and one such measurement battery is presented by Rokeach (Citation1973). Rokeach identifies values as being classified into instrumental values, which serve as day-to-day guiding principles, and terminal values, which define the desired end states of existence. Terminal values formed conceptual foundations in means-end theory (Gutman, Citation1982) and have been applied in tourism to explain differences in travel choices and behaviour (Pitts & Woodside, Citation1986) making them methodologically and contextually relevant for this study.

Sample and sample recruitment

This study recruited self-identified ‘foodies’ as its sample. Foodies are broadly recognised as individuals who are ‘food lovers’ and travel for food experiences (Getz & Robinson, Citation2014). However, given the scope of exploring food day-trippers, a focus on local food experiences was maintained. The counties of Dorset and Hampshire in the United Kingdom, food destinations with value propositions built around local produce, were set as sites for participant recruitment.

Sample recruitment used a combination of personal contacts and snowballing. Residents of Dorset and Hampshire who were 18+ years of age and who self-identified as foodies were recruited. In keeping with past similar studies (e.g. Alahakoon et al., Citation2021b), the sample size was 20. This number was deemed sufficient as the data saturation point of this study was nine aligning with the commonly accepted numbers of 8–10 for Repertory Tests (Pike & Kotsi, Citation2020). outlines sample characteristics.

Table 1. A summary of sample characteristics.

Elements and element selection

Elements or objects of interest for this study are regional food destinations. Following the same selection criteria as for the main sample, three participants took part in pilot interviews, conducted to identify popular regional food destinations within the counties of Dorset and Hampshire. It is noteworthy that the insights obtained from the pilot interview participants were highly informative; therefore, these participants were included as part of the final sample size of 20. Findings from the pilot interviews identified destination brands through the Top-of-Mind (ToM) open-ended question (i.e., What destination comes to mind when considering going somewhere in Dorset or Hampshire for a food experience?) with answers aggregating into nine destinations. Accordingly, 1. Bridport, 2. Christchurch, 3. Dorchester, 4. Lyme Regis, 5. Lymington, 6. Poole, 7. Romsey, 8. Southsea, and 9. Winchester were finalised as elements. Nine elements were considered to reflect a realistic destination choice set (Pike, Citation2012). Input from the pilot interviews was later cross-examined with online destination marketing material for confirmation. Following this it was clear that the selected elements were positioned as food destinations. For example, Lyme Regis was a known ‘foodie’s paradise’ (Dorset, Citation2023b) while Christchurch hosts an annual food festival (Tourism, Citation2023) attracting foodies from across local regions.

To present these elements to participants, sequential sets of triads, that is, a combination of three elements at a time, were used. The order of triad presentation followed the balanced incomplete design formula (Burton & Nerlove, Citation1976). This formula originally produced 84 triad combinations which were narrowed down to 24 for practical reasons as proposed by Pike (Citation2012). All interviews were conducted online via Zoom, and triads were presented in the form of PowerPoint slides following the steps outlined in Alahakoon et al. (Citation2021a).

Data collection

Interviews were conducted between April to May 2022 via Zoom to enable audio/visual interactions. They were conducted in two parts where firstly, participants were questioned about their self-identified foodie status and top-of-mind regional food destination choices. This was followed by the Repertory Test and Laddering Analysis. To ensure rigour ‘no repeat rule’ and ‘no wrong answer’ conditions were emphasised (Pike & Kotsi, Citation2016). Participants were then presented with triads of destinations, with the question ‘when thinking about local destinations to visit for food experiences in Dorset or Hampshire for a day trip, in what important way are two of these alike, but different to the third?’. This facilitated attribute elicitation. For each attribute considered as important, the follow-up question of ‘why is that important to you?’ was posed to ladder up to consequences and personal values (Reynolds & Gutman, Citation1988). This process of triad presentation and follow-up questions was repeated until the participant could not elicit any new attributes indicating saturation. Interviews averaged a duration of 20 minutes with each participant facing an average of six triads.

Data analysis and research findings

Regional food destination attractiveness

Responses to the Repertory Test formed the basis on which destination attributes salient for food day-tripping were elicited. The laddering process produced explanations of the reasoning behind those preferences. Specifically, these explanations followed an attribute (A) → consequences (C) → personal values (V) sequence to identify perceptual orientations that form the foundation of food day-tripper preferences. The inquiry took a thematic analysis format together with frequency counts (Pike, Citation2012). Hierarchical Value Maps (HVM) visualised perceptual orientations (Reynolds & Gutman, Citation1988).

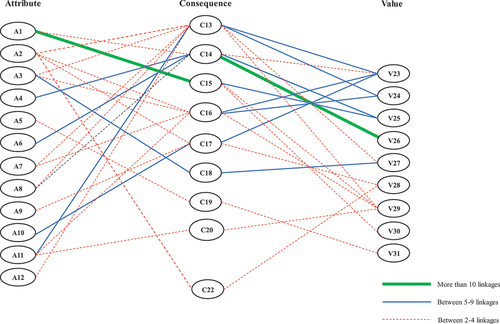

A HVM is specifically useful in demonstrating how an individual’s personal values translate to their consumption, in this case, food day-tripping. This process of analysis resulted in N = 10 personal values, N = 10 consequences, and N = 12 destination attributes as applicable to regional food destinations from food day-trippers’ perspective. highlights codes and themes and their respective frequencies for A, C, V separately.

Table 2. Themes and relevant codes.

Attributes were further condensed based on the similarity of perceptions to elicit four broader attribute categories representing regional food destination attractiveness. These broader categories serve as the highest level of themes for this study. These consist of 1) proximity-based attributes (i.e. A1 comfortable distance from home, A2 proximity to sea/beach), 2) non-food related experiential attributes (i.e. A3 history, A5 natural landscape and attractions, A10 lots to see and do), 3) food-related experiential attributes (i.e. A9 local markets, events and festivals, A11 high-end and quality of restaurants and cafes, A12 local speciality stores and food) and, 4) novelty-familiarity considerations (i.e. A4 previously visited, A6 familiarity, A7 not previously visited).

Personal values and food day-tripper attribute preferences

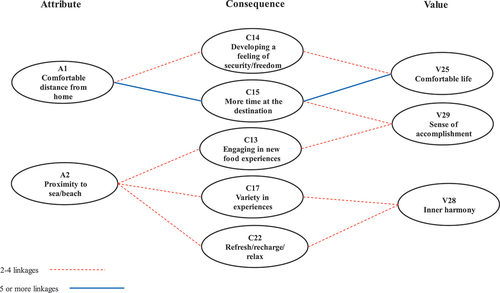

Personal values have been used to understand travel motivations (Alahakoon et al., Citation2021b; Ye et al., Citation2019) and preferences (Muller, Citation1991). The consideration of attribute, consequence, and personal value links serve a similar purpose in that they allow an understanding of individuals’ perceptual orientations or ways of thinking regarding specific consumption situations (Reynolds & Gutman, Citation1988). As can be seen from , the visualisation through a Hierarchical Value Map (HVM) offers an overview of how personal values drive attribute preferences among the entire sample of food day-trippers (n = 20) concerning regional food destinations.

Figure 1. The full hierarchical value map (HVM).

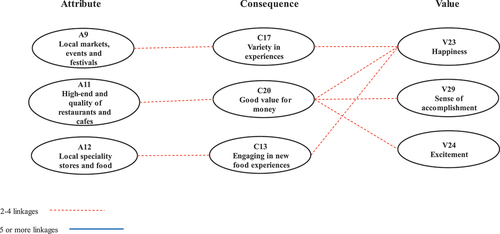

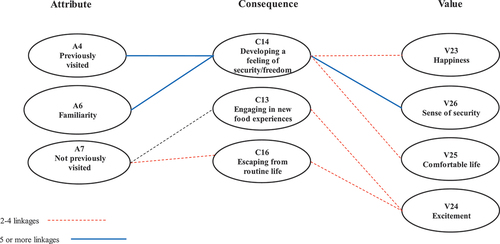

For better comprehension, individual HVM clusters were developed based on the earlier identified attribute categories presenting, 1) proximity-based, 2) non-food-related experiential, 3) food-related experiential, and 4) novelty-familiarity considerations. This categorisation enhances comprehension by presenting the dominant perceptual orientations in this context.

illustrates the proximity-based attribute cluster. The dominant orientations include: a comfortable distance from home, which leads to more time at the destination, ultimately resulting in a comfortable life.

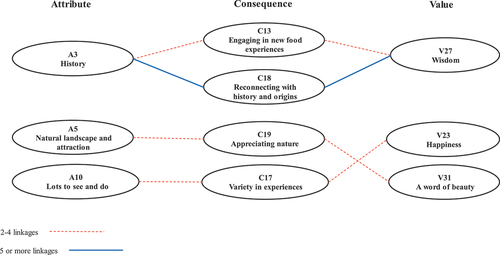

For the non-food experiential attribute cluster as demonstrated in , history, which allows for a reconnection with the past and origins, leading to wisdom appears dominant.

Figure 3. The modified HVM - non-food related experiential attributes.

Interestingly, within the food-related experiential attribute cluster no A, C, V linkage emerged as dominant as shown in .

Lastly, when considering novelty-familiarity considerations, familiarity fostering security and freedom, contributing to a general sense of security is found to be important ():

These perceptual orientation clusters indicate food day-trippers’ tendency for habitual consumption behaviours. However, varying personal values dominate those behaviours. With these insights, this study supports the proposition that food tourists are heterogeneous (Robinson & Getz, Citation2013).

Discussion

The Repertory Test results confirm that from the day-trippers’ perspective, regional food destination attractiveness is largely represented by proximity, in that a comfortable distance from home and being close to the sea/beach emerged as salient. This is followed by non-food-related experiential considerations dominated by history, so aligning with extant studies proposing culture and heritage contribute to food tourists’ choice of destination (Kim et al., Citation2022; Robinson & Getz, Citation2014). These preferences are driven by the values of comfortable life and wisdom respectively. This differs from previously reported emotional values comprising pleasure and happiness having the strongest influence on travellers’ food purchase involvement (Stone et al., Citation2018). It is however noteworthy that happiness is a value driver for food day-trippers when considering food-related experiential attributes. A further point of comparison lies in findings related to cultural tourism where exposure to culture including food, was connected to the values of identification and cultural intimacy and self-realisation and development (Zhao & Agyeiwaah, Citation2023). Food day-trippers also echoed similar value drivers through wisdom and a sense of accomplishment, showing they have value prioritisations that align with cultural tourists.

Novelty considerations among food day-trippers were conflicted. The majority recognised previous visitation and familiarity as representing regional food destination attractiveness, whilst some preferred newer destinations, closely reflecting Özdemir and Seyitoğlu’s (Citation2017) findings that categorised food tourists in a continuum of authenticity seekers, moderates, and comfort seekers. Of interest, this study found regional food destination attractiveness seemingly depends on non-food-related attributes as opposed to the suggestion that gastronomic image depends on food-related attributes such as flavour profile, cooking method and ingredients, distinctiveness, and health and safety (Chang & Mak, Citation2018). Therefore, findings demonstrate that food day-tripping is a form of casual leisure pursuit that offers individuals the opportunity to escape from their daily routines and engage in leisure activities within a short timeframe, aligning with distance decay theory (Hooper, Citation2015; Jara-Díaz et al., Citation2008; Mckercher & Lew, Citation2003; Stebbins, Citation2001, Citation2005).

Accordingly, through the lens of distance decay theory, findings highlight a cognitive trade-off between the perceived benefits of a regional food destination, and the time and effort required to travel to that destination. This supports previous research regarding the influence of time and distance on destination attractiveness (Diaz-Soria, Citation2016; Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2016). Thus, food day-trippers prioritise proximity over food-related attributes. Consistent with prior research on the role of familiarity in destination choice and value perceptions, the novelty-familiarity perceptual orientation suggests that visiting familiar food destinations outweighs the opportunity to seek and engage in new food experiences (Horng et al., Citation2012; Manimont et al., Citation2022). This is due to a desire to maintain a sense of security and comfort resulting in a lack of willingness to take risks associated with travelling to farther destinations to try new foods, which somewhat contradicts how the term ‘foodies’ is defined in previous studies (Hooper, Citation2015). In essence, it is posited that the preferences of food day-trippers are primarily influenced by proximity. As food day-tripping is considered a casual leisure activity, security and comfort seemingly take precedence over dedication to exploring new culinary experiences (Cleave, Citation2020).

Conclusion

Food tourism continues to grow in popularity. While much attention is given to international food tourism and long-haul food travel, there is an overlooked niche: food day-trippers. Considering food day-tripping as a form of casual leisure pursuit, this study examined what attracts food day-trippers to regional food destinations. Notable contributions of our research are the identification of destination attributes that represent regional food destination attractiveness and the development of HVMs that demonstrate perceptual orientations, providing beneficial insights into food day-tripper decision-making. Understanding HVMs is crucial as they illuminate how regional food destination attributes not only offer benefits but also align with the target audience’s priorities in life. This nuanced understanding enables destination marketers to tailor their strategies effectively, ensuring a more resonant and impactful connection with the target audience.

Implications for theory and knowledge

In conceptualising regional food destination attractiveness, we took a demand-side stance to explore food day-trippers’ prioritisation of destination attributes that represent regional food destinations. With the application of the Repertory Test and Laddering Analysis, we present regional destination attractiveness as consisting of proximity, non-food-related, food-related, and novelty-familiarity-based attributes. Theoretically, the importance of proximity is explained by distance decay theory which posits that destination attractiveness diminishes as distance and travel time increase (Eldridge & Jones, Citation1991; Kah et al., Citation2016; Wynen, Citation2013). This theoretical proposition has been applied to regional food tourism and leisure (Hooper, Citation2015), and this paper reinforces the same within the context of food day-tripping. We posit that food day-trippers consider the perceived benefits of a food experience in relation to the time and effort required to reach the destination. This is showcased by participants’ preference for new food experiences but within the boundaries of familiar and previously visited locations. So, despite their ‘foodie’ nature, an increase in distance may deter food day-trippers’ inclination to explore food experiences. This finding further reinforces that destination attribute preferences are circumstantial and are deeply rooted in the travel situation (Pike, Citation2012).

This research also outlines personal values that guide food day-trippers’ attribute preferences. For example, their need for comfort informs proximity, the quest for wisdom inspires engagement with history, the search for happiness inspires a preference for variety in food experiences and a sense of security guides the inclination towards previously visited destinations. These connections demonstrate food day trippers’ thinking patterns presenting them as seeking comfort, knowledge, experiential variety and locational familiarity. This nuanced conceptualisation offers a personal value-driven justification to distance decay theory, in that, we posit that together with time and effort trade-offs, the ability to enact personal values will determine a destination’s attractiveness.

This study draws parallels between food day-trippers and cultural tourists. One such characteristic is food day-trippers’ preference for historical attractions underlined by wisdom (i.e. learning) as a personal value which showed precedence over food. Another is their preference for a holistic travel experience with consumption points spread across food, beaches, historical attractions, and nature. This preference for holistic travel experiences within short time frames may be a means to offset the dissonance of selecting near-home food destinations.

Implications for practice

For destination marketers and food establishments, this study presents the specific destination attributes to highlight in marketing campaigns, including sea/beach, history, nature, variety in activities, food markets/events/festivals, high-end restaurants, and speciality stores as physical characteristics; comfortable distance from home as a spatial characteristic; and novelty considerations as an emotional association. Given the importance of non-food-related experiential attributes for food day-trippers, embedding the region’s historical and natural attractions alongside culinary ones can create a competitive advantage for regional food establishments. Furthermore, partnerships and co-branding opportunities would help create a wholesome experience for the food day-tripper. When doing so, considering the importance of personal values such as wisdom, happiness and a world of beauty, learning and engagement opportunities should be facilitated as part of the customer journey. This will ensure that food day-trippers immerse themselves in rich food experiences, reducing the dissonance that they may otherwise feel with their day-tripping choices.

Regarding the profile of the food day-tripper, this study uncovers that they look for an all-inclusive travel experience even within their limited time and space requirements. Within this profile, however, two subcategories manifest where some prefer familiar destinations and activities given their appetite for security, while others prefer novelty given their motivation for excitement that new experiences bring. This knowledge of food day-tripper thinking patterns enables marketing efforts to be tailored to suit specific market needs.

Overall, this study proposes that creating food destinations near residential areas can enhance destination attractiveness. By developing these localised food hubs, travellers can enjoy unique culinary experiences without having to travel long distances. This approach aligns with sustainability goals and contributes to the support of local businesses (Diaz-Soria, Citation2016; Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2016). This study further notes that the layout and design of geographic regions, including infrastructure, can influence the accessibility of regional food destinations. Limited accessibility may drive food day-trippers to choose destinations that are easier to get to. This emphasises the importance of spatial design in enhancing regional food destination attractiveness. Promoting walkability and accessibility apart from food-related attributes emerges as important to appeal to this emerging market of food day-trippers.

Limitations and further research

This study has limitations in terms of generalisability, which could be addressed by conducting further research with a larger sample size. There is potential to conduct quantitative research to investigate how proximity and clustering of food destinations influence travellers’ decisions to visit multiple locations within a single trip. Additionally, identifying factors that contribute to successful multi-destination itineraries would provide valuable insights for destination marketers and planners. Another promising avenue to explore is the use of choice experiments in the context of food day-tripping, which could provide valuable insights into individuals’ preferences and trade-offs when making decisions related to leisure activities, including their choices of food destinations.

Ethics approval details

The study obtained ethics approval from the Bournemouth University Research Ethics Panel, Poole, UK, and the reference number is 42165.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Guljira Manimont

Guljira Manimont is a Senior Lecturer in Business and Management at Bournemouth University. Her background in visual design complements her research interests, which span food destination branding, visual attention patterns, and sustainable consumption in pleasure-seeking contexts. She actively contributes her unique perspective to the study of food marketing, increasing visual attention towards (un)attractive food products and sustainable practices.

Juliet Memery

Juliet Memery is a Professor in Marketing at Bournemouth University. Her early research interest stemmed from her PhD thesis, which examined the influence of ethical and social responsibility issues on food and grocery shopping decisions in the UK. She continued her research in Australia and the USA, where emerging themes led her to explore her current focus on sustainable food practices, food waste, and issues related to food access and security.

Thilini Alahakoon

Thilini Alahakoon is a Research Associate at Queensland University of Technology. Her research has a broader focus on improving customer engagement behaviour through meaningful brand-consumer connections. Her specific research interests include experience studies and transformative consumer research within tourism and other service contexts.

References

- Ab Karim, S., & Chi, C. G. Q. (2010). Culinary tourism as a destination attraction: An empirical examination of destinations’ food image. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 19(6), 531–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2010.493064

- Alahakoon, T., Pike, S., & Beatson, A. (2021a). Destination image: Future research implications from the categorization of 156 publications from 2008 to 2019. Acta turistica, 33(1), 75–131. https://doi.org/10.22598/AT/2021.33.1.75

- Alahakoon, T., Pike, S., & Beatson, A. (2021b). Transformative destination attractiveness: An exploration of salients, consequences, and personal values. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 845–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1925616

- Andersson, T., & Mossberg, L. (2016). Travel for the sake of food. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1261473

- Botti, L., Peypoch, N., & Solonandrasana, B. (2008). Time and tourism attraction. Tourism Management, 29(3), 594–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2007.02.011

- Burton, M. L., & Nerlove, S. B. (1976). Balanced designs for triads tests: Two examples from english. Social Science Research, 5(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(76)90002-8

- Calero, C., & Turner, L. W. (2019). Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tourism Economic, 26(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619881244

- Chan, M. L., Opoku, E. K., & Choe, J. Y. (2022). Fast food consumption among tourists and residents in Macau: A means-end chain analysis. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 27(3), 356–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2022.2086419

- Chang, R. C. Y., & Mak, A. H. N. (2018). Understanding gastronomic image from tourists’ perspective: A repertory grid approach. Tourism Management, 68, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.004

- Cleave, P. (2020). Food as a leisure pursuit, a United Kingdom perspective. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(4), 474–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1613669

- Diaz-Soria, I. (2016). Being a tourist as a chosen experience in a proximity destination. Tourism Geographies, 19(1), 96–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1214976

- Dimitrovski, D., Starčević, S., & Marinković, V. (2021). Which attributes are the most important in the context of the slow food festival? Leisure Sciences, 46(3), 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2021.1967234

- Dorset, V. (2023a, May). Things to do in dorset. https://www.visit-dorset.com/things-to-do/

- Dorset, V. (2023b, June). Visit Lyme Regis a beautiful seaside resort. https://www.visit-dorset.com/explore/areas-to-visit/lyme-regis/

- Eldridge, J. D., & Jones, J. P. (1991). Warped space: A geography of distance decay. The Professional Geographer, 43(4), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1991.00500.x

- Fountain, J. (2022). The future of food tourism in a post-COVID-19 world: Insights from new zealand. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(2), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2021-0100

- Garay Tamajón, L., & Cànoves Valiente, G. (2015). Barcelona seen through the eyes of TripAdvisor: Actors, typologies and components of destination image in social media platforms. Current Issues in Tourism, 35(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1073229

- Gartner, W. C. (1993). Image formation process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(3), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

- Getz, D., & Robinson, R. N. S. (2014). Foodies and food events. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946227

- Gordin, V., & Trabskaya, J. (2013). The role of gastronomic brands in tourist destination promotion: The case of St. Petersburg. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 9(3), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2013.23

- Gutman, J. (1982). A means-end chain model based on consumer categorisation processes. Journal of Marketing, 46(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600207

- Hampshire, V. (2023, May). Things to do in Hampshire - visit hampshire. https://www.visit-hampshire.co.uk/things-to-do

- Herington, C., Merrilees, B., & Wilkins, H. (2013). Preferences for destination attributes: Differences between short and long breaks. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712463718

- Hinkle, D. N. (1965). The change of personal constructs from the viewpoint of a theory of construct implications. Ohio State University.

- Hooper, J. (2015). A destination too far? Modelling destination accessibility and distance decay in tourism. Geo Journal, 80(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9536-z

- Horng, J. S., Liu, C. H., Chou, H. Y., & Tsai, C. Y. (2012). Understanding the impact of culinary brand equity and destination familiarity on travel intentions. Tourism Management, 33(4), 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.004

- Huang, W.-J.-J., Chen, C.-C.-C., & Lin, Y.-H.-H. (2013). Cultural proximity and intention to visit: Destination image of Taiwan as perceived by mainland Chinese visitors. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(3), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.06.002

- Hunt, J. D. (1975). Image as a factor in tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 13(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757501300301

- Jara-Díaz, S. R., Munizaga, M. A., Greeven, P., Guerra, R., & Axhausen, K. (2008). Estimating the value of leisure from a time allocation model. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 42(10), 946–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2008.03.001

- Jeuring, J. H. G., & Haartsen, T. (2016). The challenge of proximity: The (un)attractiveness of near-home tourism destinations. Tourism Geographies, 19(1), 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1175024

- Kah, J. A., Lee, C. K., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Spatial-temporal distances in travel intention-behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.017

- Karsten, L., Kamphuis, A., & Remeijnse, C. (2015). ‘Time-out’ with the family: The shaping of family leisure in the new urban consumption spaces of cafes, bars and restaurants. Leisure Studies, 34(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2013.845241

- Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs. In Clinical diagnosis and psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Kelly, G. A. (1991). The psychology of personal constructs: volume two: clinical diagnosis and psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Kim, S., Choe, J. Y., King, B., Oh, M., & Otoo, F. E. (2022). Tourist perceptions of local food: A mapping of cultural values. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTR.2475

- Kotsi, F., & Pike, S. (2020). Destination brand positioning theme development based on consumers’ personal values. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(3), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020980056

- Lai, M., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Wang, Y. (2017). Food and cuisine image in destination branding: Toward a conceptual model. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358417740763

- Lebrun, A. M., Corbel, R., & Bouchet, P. (2021). Impacts of covid-19 on travel intention for summer 2020: A trend in proximity tourism mediated by an attitude towards covid-19. Service Business 2021, 16(3), 469–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11628-021-00450-Z

- Lee, H. A., Guillet, B. D., Law, R., & Leung, R. (2012). Robustness of distance decay for international pleasure travelers: a longitudinal approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(5), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTR.861

- Lee, T. H., Chao, W. H., & Lin, H. Y. (2018). Cultural inheritance of Hakka cuisine: A perspective from tourists’ experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.09.006

- Luković, M., Kostić, M., & Dajić Stevanović, Z. (2023). Food tourism challenges in the pandemic period: Getting back to traditional and natural-based products. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(3), 428–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2165481

- Lyu, V. C., Lai, I. K. W., Ting, H., & Zhang, H. (2020). Destination food research: A bibliometric citation review (2000–2018). British Food Journal, 122(6), 2045–2057. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2019-0677

- Mak, A. H. N., Lumbers, M., Eves, A., & Chang, R. C. Y. (2013). An application of the repertory grid method and generalised procrustes analysis to investigate the motivational factors of tourist food consumption. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.07.007

- Manimont, G., Pike, S., Beatson, A., & Tuzovic, S. (2022). Culinary destination consumer-based brand equity: exploring the influence of tourist gaze in relation to FoodPorn on social media. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1969623

- Mayo, E. J., & Jarvis, L. P. (1981). The Psychology of Leisure Travel. Boston, Massachusetts: CBI Publishing Company, Inc.

- Mckercher, B., & Lew, A. A. (2003). Distance decay and the impact of effective tourism exclusion zones on international travel flows. Journal of Travel Research, 42(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503254812

- Muller, T. E. (1991). Using personal values to define segments in an international tourism market. International Marketing Review, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339110003952

- Nicolau, J. L., Casado-Díaz, A. B., & Navarro-Ruiz, S. (2023). Assessing the effects of interaction with attractions and types of visit on day trippers’ satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(8), 1299–1315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2204396

- Okumus, B., Koseoglu, M. A., & Ma, F. (2018). Food and gastronomy research in tourism and hospitality: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 73, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.01.020

- Özdemir, B., & Seyitoğlu, F. (2017). A conceptual study of gastronomical quests of tourists: Authenticity or safety and comfort? Tourism Management Perspectives, 23, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.03.010

- Paul, T., Chakraborty, R., & Anwari, N. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on daily travel behaviour: A literature review. Transportation Safety and Environment, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/TSE/TDAC013

- Pearce, P. L. (2020). Tourists’ perception of time: Directions for design. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102932. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2020.102932

- Pike, S. (2009). Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tourism Management, 30(6), 857–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.12.007

- Pike, S. (2012). Destination positioning opportunities using personal values: Elicited through the repertory test with laddering analysis. Tourism Management, 33(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.008

- Pike, S., & Kotsi, F. (2016). Stopover destination image - using the repertory test to identify salient attributes. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.01.005

- Pike, S., & Kotsi, F. (2018). Stopover destination image–perceptions of Dubai, United Arab Emirates, among French and Australian travellers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(9), 1160–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1476303

- Pike, S., & Kotsi, F. (2020). Perceptions of stopover destinations during long haul air travel: A mixed methods research approach in four countries. Tourism Analysis, 25(2–3), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354220X15758301241774

- Pike, S., Pontes, N., & Kotsi, F. (2021). Stopover destination attractiveness: A quasi-experimental approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100514

- Pitts, R. E., & Woodside, A. G. (1986). Personal values and travel decisions. Journal of Travel Research, 25(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758602500104

- Population Data UK. (2023). UK population data. https://populationdata.org.uk/english-counties-by-population-and-area/

- Reynolds, T. J., & Gutman, J. (1988). Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. Journal of Advertising Research, 28(1), 11–31. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-35012-001

- Robinson, R., & Getz, D. (2013). Food enthusiasts and tourism: Exploring food involvement dimensions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013503994

- Robinson, R., & Getz, D. (2014). Profiling potential food tourists: An Australian study. British Food Journal, 116(4), 690–706. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2012-0030

- Robinson, R., Getz, D., & Dolnicar, S. (2018). Food tourism subsegments: A data-driven analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTR.2188

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The measurement of value and value systems. In the Nature of Human Values Free Press, (4). https://doi.org/10.1086/267645

- Rousta, A., & Jamshidi, D. (2020). Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 26(1), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766719858649

- Stebbins, R. A. (2001). The costs and benefits of hedonism: Some consequences of taking casual leisure seriously. Leisure Studies, 20(4), 305–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360110086561

- Stebbins, R. A. (2005). Choice and experiential definitions of leisure. Leisure Sciences, 27(4), 349–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400590962470

- Stepchenkova, S., & Li, X. (2014). Destination image: Do top-of-mind associations say it all? Annals of Tourism Research, 45, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.12.004

- Stone, M. J., Soulard, J., Migacz, S., & Wolf, E. (2018). Elements of memorable food, drink, and culinary tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 57(8), 1121–1132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517729758

- Suriñ, J., Casanovas, J. A., André, M. N., Murillo, J., & Romaní, J. (2017). How to quantify and characterize day trippers at the local level: An application to the comarca of the alt penedè s. Tourism Economics, 23(2), 360–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816616656273

- Tan, W. K., & Wu, C. E. (2016). An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JDMM.2015.12.008

- Tasci, A. D. A., & William C, G. (2007). Destination image and its functional relationships. Journal of Travel Research, 45(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299569

- Tourism, B. (2023, May). Food & drink experiences. https://www.bournemouth.co.uk/christchurch/food-and-drink/food-drink-experiences

- Tsai, C. T. S. (2016). Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 536–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2070

- Veal, A. J. (2017). The serious leisure perspective and the experience of leisure. Leisure Sciences, 39(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1189367

- Wang, D., Kotsi, F., Mathmann, F., Yao, J., & Pike, S. (2022). Short break drive holiday destination attractiveness during COVID-19 border closures. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 51, 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.05.013

- Williams, H. A., Yuan, J. (., & Williams, R. L. (2019). Attributes of memorable gastro-tourists’ experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348018804621

- Williamson, J., & Hassanli, N. (2020). It’s all in the recipe: How to increase domestic leisure tourists’ experiential loyalty to local food. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100745

- Wynen, J. (2013). Explaining travel distance during same-day visits. Tourism Management, 36, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.007

- Xueling, T., Yinhe, L., Yajuan, L., & Hu, Y. (2023). Production and reconstruction of food cultural spaces from a globalisation perspective: Evidence from Yanji City. Leisure Studies, 43(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2023.2191979

- Yang, Y., & Fik, T. (2014). Spatial effects in regional tourism growth. Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2014.03.007

- Ye, S., Lee, J. A., Sneddon, J. N., & Soutar, G. N. (2019). Personifying destinations: a personal values approach. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1168–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519878508

- Zhao, Y., & Agyeiwaah, E. (2023). Exploring value-based motivations for culture and heritage tourism using the means-end chain and laddering approach. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 18(5), 594–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2023.2215933