ABSTRACT

The process of urbanisation and the associated urban lifestyle have been linked to social isolation and negative mental health impacts. As urbanisation and mobility continue to surge in African cities, urban planners face the challenge of creating inclusive spaces that encourage social interaction among urbanites. This research utilises the conceptual lens of ‘Third places’ to assess the role of urban community gardens in cultivating spaces that mitigate the negative effects of urbanisation within distressed communities in Cape Town, South Africa. A qualitative approach, involving open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews, along with observations, was employed to achieve the research aims. Findings revealed that individuals perceive community gardens as a channel for breaking free from isolation and fostering informal interactions among neighbourhood residents. However, the effectiveness of these gardens is hindered by several factors, such as their location and land tenure insecurity, which impede their ability to bring about meaningful changes within their communities. This research urges scholars to critically reconsider established criteria for third places, advocating for a nuanced understanding that acknowledges the diverse dynamics of community gardening in global South cities, thereby enriching theoretical discourse and informing practical interventions for fostering inclusive and sustainable urban communities.

1. Introduction

Urbanisation has brought about rapid changes, transforming rural settlements into dense urban centres (Ali & George, Citation2022). However, contrary to expectations, the massive relocation of individuals into urban centres has not promoted unity but has given rise to social problems like urban isolation. This is partly due to the design of urban spaces that tend to promote isolation as opposed to social interaction (Ali & George, Citation2022). Moreover, this is accentuated by the decline of public space in cities due to privatisation and regulation of public spaces (Milbourne, Citation2021). As a result, public spaces end up being managed with a commercial approach, leading to increased privatisation, either in full or partially, or transferred to third-sector organisations to generate profit. In seeking to comprehend the issue of isolation and the decline of public spaces, scholars have endeavoured to explore the mechanisms by which certain spaces facilitate social interaction within urban areas. Among these mechanisms is the concept of the Third Place, coined by Ray Oldenburg in 1989 in his book ‘The Great Good Place’ (Oldenburg, Citation1989).

Oldenburg emphasised the need for informal spaces to foster social interaction and bridge the gap between home (first place) and work (second place). He illustrated Third Places through examples of bars, cafes, and public parks, arguing that such spaces fostered informal interactions that were becoming a scarce phenomenon as a result of urban life. Third Places play a crucial role, especially for segments of society with limited chances for social engagement, like the elderly and recently joined members of the community i.e. migrants (Heath & Freestone, Citation2023). The concept of the Third Place has been extensively examined in the literature, particularly within the realm of leisure activities. For instance, in settings such as curling clubs and old age centres (Hutchinson & Gallant, Citation2016; Mair, Citation2009), scholars have explored its implications. Since its inception, the concept has found application across diverse disciplines, with scholars exploring various contexts such as libraries, religious institutions, marketplaces, beach sites, transportation systems, and urban community gardens (see Dolley, Citation2020; Kuzuoglu & Glover, Citation2023; Littman, Citation2022; Melete et al., Citation2015; Peters, Citation2016; Yuen & Johnson, Citation2017).

The academic literature draws connections between urban community gardens and third place, highlighting how urban community gardens can serve as valuable spaces for informal interactions in neighbourhoods (Dolley, Citation2020). For example, Dolley (Citation2020) has shown how community gardens offer solutions to problems arising from increased mobility in Australia. Milbourne (Citation2021) examines community gardening projects in 15 cities across Australia, Canada, the UK, and the USA. He emphasises how these projects are fostering new environments of publicness that transcend traditional boundaries between public, private, and in-between spaces. Similarly, Firth et al. (Citation2011) emphasise the role of community gardens as spots for informally meeting other neighbours within a community. Veen et al. (Citation2014) recognise their potential to provide spaces for regular relaxation in the company of others.

The phenomenon of urban community gardening is a global trend, observed in countries like South Africa (Kanosvamhira, Citation2023; Malan, Citation2015), Mexico (Engel Di Mauro, Citation2018), Germany (Follmann & Viehoff, Citation2015), the United States of America (Eizenberg, Citation2012), and Australia (Dolley, Citation2020). However, the academic literature on community gardening as a third place has mainly focused on Europe and America, leaving global South cities underrepresented despite the prevalence of community gardening and the impact of urbanisation in these regions. Community gardens in the Global Nouth serve as vital social spaces, particularly in urban areas grappling with rapid urbanisation and social fragmentation.

In regions with greater economic prosperity, community gardening is often perceived as a recreational pursuit. However, the context shifts significantly in the Global South, where these spaces serve multifaceted roles extending far beyond leisure. Instead, they act as vital pillars of community resilience, addressing fundamental needs such as food security, economic empowerment, social capital development, and cultural exchange (Modibedi et al., Citation2021). Consequently, scholarly attention has predominantly focused on these primary functions rather than secondary benefits. Community gardens in the Global South frequently emerge organically as grassroots responses to intricate socio-economic challenges, highlighting the resilience and agency of marginalised communities. As a result, these spaces develop into pivotal hubs where a variety of social groups converge, facilitating social cohesion and solidarity amidst urban pressures (Kanosvamhira & Tevera, Citation2020).

Hence, this research fulfils this empirical gap. With Africa’s urban population predicted to exceed that of Europe, North America, and South America by 2050 (Ali, Citation2021), and urbanisation rapidly increasing (UN-DESA/PD, Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2019), this study aims to explore whether urban community gardens can be considered as ‘third places’ and to what extent this framing is applicable in a global South context. This is a particularly timely investigation given the rates of urbanisation in the region that continue to alter social dynamics and cause-related impacts. This research explores the significance of urban community gardens as third places in urban neighbourhoods of the Cape Flats (historically marginalised areas in Cape Town as a result of apartheid). I seek to understand the potential value of these spaces by examining their role in fostering social interaction and promoting well-being on the Cape Flats. Using a qualitative approach, the research investigates how urban community gardens in Cape Town, South Africa, can function as third places and arguably ‘only’ places, promoting social ties and connections among residents in diverse urban settings. The conceptual lens is not adopted blindly but is used as a guide and also critiqued based on the specific context of Cape Town to offer considerable insights. Hence, the research makes a empirical contribution but also advances the understanding of third places within the largely ignored global South context. It develops the argument by Neo and Chua (Citation2017) who have argued that such spaces (community gardens) do require a level of responsibility from the members to ensure their sustainability. The findings can inform urban planners and policymakers in creating inclusive spaces that foster a sense of belonging and community in rapidly evolving urban landscapes.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 explores the conceptual framework of Third Places and its application to the study. Section 3 discusses the study area, emphasising spatial apartheid challenges exacerbated by urbanisation in Cape Town’s Cape Flats. The methodology is outlined, followed by Sections 5 and 6 presenting the results and their implications. The conclusion underscores the significance of the conceptual framework and offers recommendations for future research.

2. The third place, the ‘only’ place and urban community gardens as a conceptual lens

The concept of the Third Place has a long history but was coined by Ray Oldenburg in 1989 in his publication titled ‘The Great Good Place’. In this book, he argued that urbanisation in America had resulted in the isolation of the masses of people (Oldenburg, Citation1989). In addition to the urban lifestyle, he noted that the US failed to produce sufficient informal spaces to promote social interaction in the city. Building on the concept of the Third Place presented by Georg Simmel, he noted that a Third Place was required to bridge the gap between what they called the First Place (home) and Second Place (work). The Third Place could offer more neutral spaces that promote social capital development in the fast-paced urban life.

Based on the analysis of commuters’ lifestyles, Oldenburg (Citation1989) conceptualised the Third Place as possessing eight essential elements that could facilitate the Third Place, promoting social capital and a healthier urban lifestyle. The eight characteristics identified by Oldenburg in Chapter 2 of his book include the following: it must be easily accessible to all without entry requirements, must be accessible by walking, should be able to bring together people from all backgrounds, should feel like a home away from home, neutral ground: people are free to come and go without obligations, must have an entertaining atmosphere, maintain a group of regulars, facilitate easy conversation among members, and not stand out or be showy but plain. Hence, such places are primarily inclusive and open to the general public without any hindrance, as is the case with societies or clubs where one may need to pay for memberships. Oldenburg uses examples of commercial places such as bars, cafes, and public places such as parks as instances of Third Places. The literature has used the concept to examine third places in various contexts such as marketplaces (Melete et al., Citation2015), infrastructure (Kuzuoglu & Glover, Citation2023), curling clubs (Mair, Citation2009), old age centres (Hutchinson & Gallant, Citation2016), and urban community gardens (Dolley, Citation2020).

Urban community gardens are defined as public gardens that focus on food cultivation, typically established and maintained by local communities for the benefit of individuals and collectives (Guitart et al., Citation2012). Their main objective is to cultivate food or flowers, leading to a blend of socio-ecological, environmental, political, and economic advantages. Urban community gardens produce a ‘third place’, intersecting private and public worlds, creating a neutral social interaction space (Dolley, Citation2020; Schmelzkopf, Citation1995). Even in cases where strangers cultivate on individual plots, they find it easier to interact with one another since they share a commitment to cultivation (Huron, Citation2015). Community gardens also provide a space where garden members and non-members can meet and interact. This is achieved through day-to-day activities such as social events that occur in the garden. Therefore, in addition to cultivation spaces, urban community gardens can serve as social spaces in various communities (Kanosvamhira & Tevera, Citation2024). Empirical studies have confirmed this phenomenon (see Certomà & Tornaghi, Citation2015; Dolley, Citation2020; Milbourne, Citation2021; Veen et al., Citation2016). In global South cities such as Cape Town the literature has indicated that while community gardens primarily focus on food production, they also offer various other benefits such as promoting healthy lifestyles, providing education, and fostering community development and cohesion (Battersby & Marshak, Citation2013; Kanosvamhira & Tevera, Citation2024; Olivier & Heinecken, Citation2017). These connections between social dynamics and third place warrant further exploration. Therefore, this particular study utilises this concept by looking at how a community garden can function as a third place fostering interaction in otherwise distressed neighbourhoods suffering from various socio-economic and environmental challenges.

The concept of the third place continues to be relevant today given the continued weakening of social bonds due to urbanisation and the aforementioned challenges (Dolley, Citation2020). Urbanisation continues to occur at massive rates in Africa, where people leave rural-based economies searching for work, healthcare, and education. This move usually results in immigrants with limited social circles. Moreover, the urban lifestyle is characterised by excessive work on one’s items and limited time to interact with others. Consequently, urban planners need to rethink space to ensure they encourage social interaction among urban residents. Nevertheless, the conceptual lens has its limitations which render it inadequate for global city contexts that face different contextual variations from their global North counterparts. For example, while some of the elements of a Third Place such as access to the place are well defined they are not necessarily suitable in environments such as South Africa where public spaces are prone to theft, vandalism, and crime (Perry et al., Citation2008). Revisiting the concept of the third place provides a promising foundation for this study. Here, the concept and its eight elements guide the examination of urban community gardens as potential third places in Cape Town’s disadvantaged neighbourhoods. However, it’s crucial to critically assess its applicability and limitations in this distinct context.

3. Study area

Cape Town is generally divided between the picturesque slopes of Table Mountain and stunning white beaches on one side, and some of the world’s most dangerous areas on the other (Geldenhuys, Citation2022). This other side, also known as the Cape Flats, a flat and sandy region on the outskirts of Cape Town’s central business district, has been historically characterised by social challenges, limited social cohesion, and high levels of isolation, crime, and other social problems. It is an area primarily inhabited by the Coloured and Black racial population groups and consists of apartheid-era designated townships that continue to exist to this day. Due to poor soils, housing developments were initially discouraged, but this changed with the implementation of apartheid spatial planning policies. Cape Town has a population of approximately 4 322 031 inhabitants, experiencing rapid urbanisation at a growth rate of 1.6% annually (COCT, Citation2016). A significant component of this rapid urbanisation is the internal and external migration. Internal migration is characterised by rural to urban migrants mainly from the Eastern Cape province who relocate to Cape Town (usually on the outskirts) due to limited economic opportunities, poor education, and a failing rural economy in their province (WEF, Citation2017).

In contrast to the more affluent suburbs, the Cape Flats lacks adequate recreational and social facilities, as well as industrial and commercial centres. These deficiencies have contributed to limited social fabric and cohesion within the communities residing in this region. However, amidst these challenges, urban agriculture has emerged as a visible phenomenon, promoted by the local and provincial government as a means to address food insecurity (Kanosvamhira, Citation2019). The Cape Town municipality, along with civil society organisations, has been actively involved in supporting and implementing urban agriculture initiatives to alleviate poverty and improve food security. Urban agriculture occurs across the city but is particularly visible in the Cape Flats due to the municipality’s promotion of the activities as a panacea for food insecurity. In Cape Town, urban agriculture receives support from the provincial government, local government, and civil society (Kanosvamhira, Citation2019, Citation2023). The municipality has directly worked with other actors, such as the provincial government and Non-governmental Organizations, to implement food production projects within the city.

Urban gardeners in the Cape Flats heavily rely on civil society actors for resources and opportunities, leading to an uneven power structure that hinders the cultivation of a sustainable food system in low-income communities (Paganini & Lemke, Citation2020). Civil society organisations play a prominent role in encouraging urban agriculture activities in Cape Town (Kanosvamhira, Citation2019; Kanosvamhira & Tevera, Citation2021). Most urban gardeners in the Cape Flats, the study site, depend on civil society organisations for receiving subsidising inputs, infrastructure, and market opportunities (Kanosvamhira & Tevera, Citation2020). Urban community gardens in Cape Town face challenges such as resource shortages, community participation issues, and incidents of theft and vandalism within their operating areas (see Kanosvamhira, Citation2023; Olivier & Heinecken, Citation2017).

This study aims to explore the role of urban agriculture, particularly community gardens, on the Cape Flats as potential third places that may contribute to fostering social interaction and cohesion within distressed neighbourhoods. The decision to focus on Cape Town for this study is driven by the city’s unique political, social, and economic conditions, particularly in the Cape Flats area. This region, marked by historical social challenges, limited cohesion, and high levels of isolation and crime, offers a unique setting to examine the role of community gardens. The intentional selection of cases is driven by shared challenges, aiming to uncover the complexities faced by urban community gardens in distressed neighbourhoods. The study’s findings offer valuable insights for urban planners and policymakers seeking to foster inclusive and socially connected urban spaces by exploring how community gardens can address issues like isolation and crime. These insights can inform efforts in urban planning and policymaking to create more inclusive and socially connected urban environments.

4. Methodology

Between 2020 and 2021 I employed a multi-case study approach across four gardens in the neighbourhoods of Mitchells Plain, Ottery and Khayelitsha on the Cape Flats. The multi-case study approach was deemed essential as it enables thorough exploration of phenomena across diverse contexts, facilitating comparative analysis, theory building, and nuanced insights into complex issues within authentic real-world settings. For each of the gardens a combination of qualitative research instruments were employed to collect data in the Cape Flats, focusing on four urban community food gardens.

The selection of these areas was deliberate, considering their shared challenges such as poverty and food insecurity. Additionally, the areas exhibit distinct demographics, with one situated in a predominantly blackFootnote1-dominated neighbourhood and the others in predominantly coloured populations. Despite featuring four specific cases, the selection criteria extend beyond exclusivity. The aim is not to suggest that these are the sole community gardens facing such challenges, but rather to provide a concentrated exploration within a specific context. This approach allows for a nuanced examination of the unique dynamics and opportunities offered by community gardens in addressing prevalent issues such as social isolation and crime. The inclusionary criteria employed encompassed various factors. Geographical diversity was a priority to ensure representation across different neighbourhoods within the Cape Flats area, capturing a diverse range of community contexts and experiences. Additionally, sites were chosen based on their status as urban community food gardens, aligning with the study’s focus on urban spaces that foster social interaction and community cohesion. Moreover, sites were selected based on their willingness to participate, ensuring active engagement and cooperation throughout the research process.

To gain insights into urban community food gardens, a qualitative research design employed a questionnaire survey with open-ended questions targeting members of four gardens. The questions aimed to understand the gardens’ roles within their communities, dynamics of social interaction, challenges in serving as Third Places, and strategies for fostering community engagement.

These where then followed up by four semi-structured interviews with the urban community garden representatives. The main survey was conducted on the community garden sites during the day. These were then followed by semi-structured interviews that lasted between 60–70 minutes long, and also follow up phone call conversations with two garden representatives to obtain more information and clarity on issues that arose from prior conversations. The aim of the semi-structured interviews was to understand how gardens functioned as a third place in the community. So the lead questions were formulated around the eight criteria indicated in the first column of .

Table 1. Scoring each urban community garden against the eight ‘third place’ categories.Footnote4

Observations were also conducted to identify how the urban community gardens conducted key activities and to examine their general layout. A non-state organisation called Abalimi BezekhayaFootnote2 that supports urban agriculture in the area facilitated access to the urban community gardens in Khayelitsha. Subsequently, snowball sampling was used to identify the other two gardens which did not necessarily have any interactions with civil society actor that was the entry point.

The semi-structured interviews were meticulously conducted with the full consent of the participants,Footnote3 adhering strictly to ethical guidelines. Following the interviews, the recorded audio files were manually transcribed verbatim, ensuring accuracy and fidelity to the original dialogue. Subsequently, a traditional content analytical approach was employed, wherein the transcripts were scrutinised iteratively. This iterative process involved meticulous examination of the transcripts to identify recurrent patterns, emerging themes, and noteworthy insights. The rigorous and systematic nature of this analysis methodology ensured the robustness and reliability of the findings, contributing to the credibility and validity of the research outcomes. The names of the community gardens are not published and for reporting purposes, each community garden interviewee was assigned a unique number from 1 to 4. Gardener representatives were identified using specific codes, including the interviewee number, sex, and age.

To ensure the trustworthiness and rigour of the study, some key measures were implemented. Firstly, peer debriefing sessions were utilised to refine interpretations and identify potential biases, alternative interpretations, and areas for further investigation, bolstering the robustness and comprehensiveness of the study. Furthermore, triangulation was employed, utilising multiple data sources to corroborate findings and enhance the reliability and validity of the conclusions. This approach mitigated methodological biases and enriched the insights gleaned from the study. Additionally, reflexivity played a critical role, and I had to engage in ongoing self-reflection to minimise personal biases and enhance the objectivity and credibility of the findings.

5. Findings

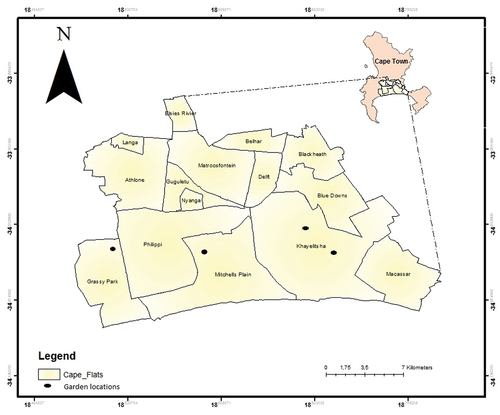

The research collected information from four urban community gardens situated on the Cape Flats in the neighbourhoods of Khayelitsha, Ottery, and Mitchells Plain (see ). provides a overview of the demographic profile of the members across the four gardens. The following paragraphs present the results. Utilising the data acquired from the questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and observations, each garden is evaluated against the Third Place categories outlined to determine the degree to which each community garden can be regarded as a third place within the community (refer to ).

Table 2. Social demographic characteristics of participants in different community gardens.

Garden A

Garden A consists of 9 members consisting of one female and 8 males. The garden was launched with the goal of contributing to his community in Ottery. Initially, the project made use of public school land, and over time, it expanded its cultivation efforts to communal spaces between residential flats. These spaces were transformed into food gardens, as depicted in the below. The garden serves as a constructive environment for community members, including individuals who were once associated with gangs. According to one of the respondent’s the garden allowed them to reconnect with their neighbourhood and overcome past stigmas associated with gangsterism. The co-founder indicated that having been a part of the drug and gang scene in the past, he had personally witnessed the pervasive and deadly violence in the area, which was under the control of gangs involved in the distribution of drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and cannabis.

Motivated by his aspiration to establish a more pleasant environment for the local children and make a positive contribution to the community, the project accomplishes more than just enhancing the area’s aesthetics; it also supplies food for elderly residents. The interviewee pointed out that some of the project’s members come from challenging backgrounds, and as a result, they deeply value the time they invest in the gardens. This time spent together enables them to develop and nurture relationships that prove beneficial. For instance, the lead gardener highlighted that:

‘Like I said in all of the communities you get certain challenges in the and for me being there and having done that I have to share my knowledge. Those people working in the garden also have immediate or extended family facing the same challenges so why are we spending time in the garden? it gives us the opportunity to actually talk about some of those issues, and discuss because we like a brother-hood and sisterhood so if you come to the garden and we see that you not looking good, we know already that something has happened we will ask if there is perhaps something we can do for you, you know or if something happens we always say, don’t stay at home but come to the garden and share even if we have to stop and sit down to quickly take break and discuss something and we can come up towards a solution. … . if one of the substance abuser or former gang member wants to join the garden we are prepared because I have been there I can invite them and say don’t feel any different I can speak your language’ (M1-50-59)

The aforementioned quote illustrates how the gardens aim to bridge the gap between individuals who may be considered outsiders to the community but seek to reconnect with it. With assistance from the city, the community garden received training, equipment, seedlings, and additional resources, leading to its expansion and heightened interest among community members. The gardens are open to all community residents, encouraging collaboration through shared responsibilities.

Despite lacking physical fencing, an unspoken rule is upheld to ensure the smooth operation of the gardens and prevent any potential challenges that could disrupt their functioning. One of the participants mentioned, ‘We have rules which we abide by, however, and everyone has a say in the manner in which the garden functions’. This indicates that members follow a democratic process in terms of their behaviour and conduct within the garden. Furthermore, he emphasised the necessity for a cautious examination and thoughtful implementation of the situation when it comes to community projects, as depicted in the excerpt below:

Establishing a food garden is unfamiliar to the community, and there’s also the issue of drug addicts viewing it as an opportunity to steal seedlings. They even go as far as stealing crops before harvest. So, your approach to establishing the garden and the success of the project could be in jeopardy if you don’t raise awareness among the people in the vicinity of the garden. You need to find a way to inform them about why you’re starting the garden and the benefits it brings to the community. By doing so, you’ll start building a sense of security. This means that if certain individuals attempt to vandalize your garden, the community will be more inclined to intervene and prevent such actions. (M1-50-59)

Based on the converstations with the participants, it was determined that the project met 7 out of the 8 criteria of the Third Place categories. However, the garden did not completely fulfil the accessibility criterion, primarily due to the fact that certain garden sites were situated on school premises and were enclosed in a way that might have made other community members feel unwelcome in the space.

Garden B

Garden B, located in Mitchells Plain, consists of five members-two males and three females. It serves as a training hub, focusing on promoting home gardening and agro-ecological vegetables within the local community. Initially formed as part of a neighbourhood watch aimed at enhancing safety in the area, Garden B (see ) shifted its focus during the pandemic to address urgent food needs within the community. As a result, alongside their safety initiatives, they broadened their efforts to tackle food security through endeavours like soup kitchens and donations.

Within the group were both experienced home and community gardeners who saw an opportunity to further their skills and advocate for urban gardening within their neighbourhood. The initial three members decided to utilise land adjacent to a community hall to establish the garden. All residents of the Block, the gardeners share a common vision: to cultivate a sustainable source of fresh, organic produce that can nourish and sustain their community. The interviewee emphasised that the primary purpose of this garden was to foster a robust sense of community, with the community garden serving as a space to achieve this objective. Respondents indicated that key activities make the place lively, encouraging social interactions in the community. For instance, two members joined the garden on a regular basis after attending workshops organised by the garden, where community members gather to learn the art of creating home gardens. This initiative stems from a desire to empower residents to nurture their own green spaces and cultivate a deeper connection with nature.

In addition to educational activities, the garden organises engaging events to attract people from diverse backgrounds. It hosts open days where community members enjoy cups of soup made from garden-fresh ingredients while discussing community issues. Despite its small size, it benefits from its proximity to the community hall, used for various events, making it conveniently located. Although fenced off, the garden uses social media to inform the community about its activities, including through the local newspaper, the Plainsman (see ).

This multifaceted approach not only enriches the community’s connection to gardening but also creates a space for meaningful interactions, knowledge exchange, and a shared commitment to building a stronger, more resilient neighbourhood.

Garden C

Garden C, consisting of 5 females, is situated in Khayelitsha and emerged in response to community members’ request for its establishment, with support from a non-profit organisation operating in the area in 1997. This innovative project aimed to educate economically disadvantaged individuals in the community about cultivating organic crops for both sale and personal consumption. Additionally, the initiative placed a strong emphasis on preserving indigenous flora through the implementation of windbreaks and the promotion of alternative farming technologies. The project’s main hub, located in Khayelitsha, covered a 5,000 m2 area previously under power lines.

Thriving in its endeavours, the garden not only sold its produce locally but also engaged with other third parties like the now-defunct Harvest of Hope. However, Harvest of Hope ceased its operations in 2019 due to financial reasons. As of now, Garden C serves as a micro-urban agriculture model in Cape Town. Over the years, the garden has expanded and evolved, inspiring several community members to engage in gardening, leading to the establishment of several other community gardens. Often referred to as the ‘power line project’, it remains a prominent example of micro-urban agriculture in Cape Town.

Currently, the gardeners manage the gardens, cultivating a diverse array of organic crops including cabbage, spinach, broccoli, beans, and sweet potatoes, both collectively and individually. They not only sell their produce and seedlings to local vendors and schools but also use surplus produce for their own sustenance, share with neighbours, and distribute to those in need. The respondents indicated that they appreciated the social and emotional benefits derived from participating in garden activities, beyond just economic gain.

Among the gardens in the area, this garden stands out with its solid infrastructure, including a hall that serves as a training centre. This hall houses the Young Farmers Training Centre (YFTC), where individuals are taught the art of organic farming while also promoting the conservation of indigenous flora and exploring alternative agricultural methods. The garden hosts bi-monthly meetings for its members to address any emerging issues and strengthen community bonds. The green space at the garden also plays a pivotal role, hosting various community events, especially during celebrations such as World Food Day and Mandela Day. Furthermore, the hall is utilised as a church on Sundays. This aspect has turned the gardens into a hub for the community, as confirmed by respondents who indicate that they strive to provide hope for vulnerable women facing various challenges, including domestic abuse. This project not only empowers the community through agriculture but also serves as a platform for promoting healthier lifestyles and improved access to fresh, nutritious food. The garden seeks to foster education and a stronger sense of togetherness in the community. As one respondent indicated;

The change pertains to the aspect of health; it has brought about a positive contribution in this area. Moreover, it has evolved into a social space. Beyond the challenges inherent in gardening, we gather, converse, exchange advice, and offer assistance to one another. At times, financial constraints may be present, yet our awareness of a greater number of individuals facing similar economic difficulties motivates us. Recognizing this, we choose to explore avenues through which we can provide support to those in need. … . Additionally, we engage in open discussions about various issues. As a united group of women, we collaborate to devise solutions for specific problems. On occasion, we guide others on where to seek help if a situation exceeds our capabilities, such as approaching government agencies or social development organizations. (F-40-45)

The excerpt above highlights that the garden’s mission extends beyond mere economic activities; it also prioritises the well-being of its members and the broader community. By amplifying these voices, the excerpt underscores the holistic approach adopted by the garden, which prioritises the overall well-being and resilience of its members and the community at large.

Garden D

In February of 2014, Garden D in Khayelitsha was initiated by local residents with the aim of growing crops for both personal consumption and sale in local and external markets. However, they warmly welcome individuals interested in learning about cultivation to join their garden. In the early stages, some respondents fondly recalled their leader driving around the township, announcing and inviting people to attend meetings. These meetings aimed to brainstorm ways to address food security issues within the community by utilising the land obtained from the municipality.

During the initial meetings, prior to the garden’s actual operation, discussions revolved around matters such as financing the plot and sharing electricity costs. Interestingly, many participants believed that the government would financially support their involvement in the garden, rather than requiring them to cover the costs themselves. Consequently, a significant portion of prospective gardeners dropped out of the project during this stage.

Garden D in Khayelitsha has evolved into one of the oldest community gardens in the area, boasting a dedicated team of 12 gardeners. Each member is responsible for cultivating food crops in their allocated plots within the garden. Over time, the gardeners decided to restructure the garden, assigning individual plots to each member. This reorganisation has resulted in significant improvements in harvests and has allowed for more personalised working rhythms. After seven years, what initially began as a modest vegetable garden has flourished into a comprehensive community development project. Its impact extends beyond sustaining the women involved to providing employment opportunities for men in Khayelitsha.

Of noteworthy significance, Garden D serves a dual purpose: local residents cultivate food crops both for personal use and for sale throughout Cape Town. Moreover, the community has designated a specific area within the garden to create a new indigenous food garden, further diversifying their produce and promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Despite the allocation of individual plots, the gardeners remain a closely united team, offering mutual support during challenging periods. This collective effort nurtures a sense of familial connection among the members. Additionally, since only two members possess vehicles, they gladly assist others in collecting necessary materials and seeds. The garden is open to the public and actively encourages community engagement by inviting members to volunteer their time and efforts within the garden’s nurturing environment. Nevertheless, one respondent indicated that there was limited engagement from the community. Further conversations with some respondents revealed that typically people came to the garden requesting work and payment. This could be attributed to the business model of the garden.

6. Discussion

The existing scholarly discourse on urban community gardens, as evidenced by the works of Dolley (Citation2020), Certomà and Tornaghi (Citation2015), Gray et al. (Citation2022), Milbourne (Citation2021), and Veen et al. (Citation2016) have consistently probed their potential to embody characteristics resembling third places. This study examines community gardens in Cape Town, South Africa, emphasising their unique characteristics and integration of third-place elements, contextualised within the broader theoretical framework of the ‘third place’. The concept of the ‘third place’ suggests that informal gathering spaces beyond the ‘first place’ (home) and ‘second place’ (work) are vital for nurturing community connections and social interaction (Oldenburg, Citation1989). However, the literature suggests an ongoing theoretical debate concerning the conceptual boundaries and applicability of the ‘third place’ concept across diverse urban contexts. Critics and proponents engage in discussions regarding the universality of the eight criteria outlined by Oldenburg, debating the adaptability and relevance of these criteria in different socio-cultural settings.

In light of this theoretical backdrop, this study contributes by offering a nuanced examination of community gardens in Cape Town as potential third places. It delves into the dynamics, challenges, and contributions of these gardens, providing insights that enrich the ongoing theoretical debate on the ‘third place’. By analysing the unique features and contextual differences of these Cape Town community gardens, the study seeks to expand our understanding of how the ‘third place’ concept manifests in diverse urban landscapes.

Within the scope of this study, the results highlight that, of all the gardens examined, Community Garden A and B exhibit all eight essential elements of the Third Place concept, as outlined by Ray Oldenburg. These gardens maintain an open-door policy for community members and actively encourage interactions among participants, thus being generally accessible to all community members. The primary focus most is not on generating income, but rather on fostering interactions among individuals. The harvested produce is shared equally among members, with surplus produce benefiting elderly community members. These gardens effectively facilitate informal exchanges within the neighbourhood, establishing inclusive and accessible spaces that are open to all without any prerequisites.

These gardens strive to cultivate a sense of familiarity, offering a neutral ground for unrestricted engagement. As indicated by a member from Garden A, there were no judgements but a genuine intent to help one another, regardless of the challenge. This sentiment was echoed across all the four gardens. With a dedicated committee overseeing garden management, newcomers experience a welcoming atmosphere. Regular members facilitate easy conversations, especially helping new members integrate into the garden community. This integration occurs primarily through day-to-day activities and garden events, such as those in garden B. Moreover, such gardens provide an enjoyable yet unassuming environment, making people from diverse backgrounds feel embraced and welcomed (Heath & Freestone, Citation2023).

However, the economic model adopted by gardens C and D poses a significant challenge to their role as neutral and accessible third places. Gardens that prioritise economic sustainability over community engagement may allocate their time and resources predominantly towards productive activities, diminishing their capacity to function as inclusive social spaces. This observation underscores the nuanced interplay between economic imperatives and the social function of community gardens. The deviation from the traditional ethos of community gardening especially in the case of D may be attributed to the unique contextual factors shaping their operations. In contrast to more affluent regions in the global North where community gardening is often perceived as a leisure pursuit (Hencelová et al., Citation2021; Trendov, Citation2018), community gardens in the Global South, such as those in Cape Town, serve multifaceted roles beyond recreation. These spaces serve as vital hubs for community resilience, addressing pressing concerns related to access to vegetables, and economic empowerment (Modibedi et al., Citation2021). Consequently, the prioritisation of economic activities in gardens C and D may stem from the imperative to address these urgent community needs, where issues of survival and sustainability take precedence over leisure and recreation. The socio-demographic data shows that Garden D has the highest number of unemployed individuals among the sampled gardens. This suggests that many participants rely on gardening to generate income, which aligns with previous research indicating that income generation is a common motivator for engaging in urban community gardens (Tembo & Louw, Citation2013).

It is essential to acknowledge these contextual nuances and the diverse functions that community gardens serve within their respective communities. While gardens C and D may appear to be exclusionary due to their economic focus, their significance as pillars of community resilience and resource hubs cannot be overlooked. The literature demonstrates that classic examples of third places identified by Oldenburg encompass commercial businesses such as salons, coffee shops, and taverns (Oldenburg, Citation1999), all of which are commercial establishments. This suggests that commercial settings can indeed fulfil the functions of third places. Therefore, while evaluating the effectiveness of community gardens as third places, it is imperative to consider the broader socio-economic context in which they operate and appreciate the multifaceted roles they fulfil within their communities. Such nuanced analysis enriches our understanding of the complex dynamics shaping urban community spaces and underscores the need for context-sensitive approaches in assessing their social impact and relevance.

The community gardens in Cape Town transcend their physical existence as mere ‘third places’ for social interaction and leisure; they become essential sanctuaries for individuals facing profound socio-economic challenges, effectively serving as their ‘only place’ amidst adversity. Through this lens, the study reveals that certain members, grappling with unemployment and difficult family circumstances, find themselves in a precarious state, where the distinctions between their ‘second place’ (work) and ‘first place’ (home) blur. Consequently, these community gardens emerge as the sole refuge for these individuals, offering solace and a sense of belonging in the midst of adversity. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in gardens C, where the majority of participants are female, a vulnerable demographic in these distressed communities. Prior research has underscored the transformative potential of such activities for women, fostering empowerment, building vital social networks, and cultivating a sense of security and solidarity within these neighbourhoods (Olivier & Heinecken, Citation2017; Slater, Citation2001).

Similarly, garden A extends its reach to community members, including former gang members, providing a platform for reconnection with the community and their families. Recognising the profound impact of these spaces is crucial, especially for individuals who lack alternative outlets to address their challenges. Through the support and guidance of fellow community members, these community gardens become catalysts for resilience and empowerment, transcending their designation as ‘third places’ to become vital lifelines for those in need.

Conversely, while urban community gardens in Cape Town may serve as sanctuaries for marginalised individuals, it is vital to consider their limitations. The exclusive reliance on these community garden spaces as ‘only places’ for some members could hinder their effectiveness as ‘third places’. Moreover, a concentration of individuals facing hardship may detract from the recreational and social aspects typically associated with such spaces. Reliance on gardens as sole refuges could foster isolation and dependency, hindering the development of inclusive social networks. Hence, it is important for gardens such as Garden A to be connected to other stakeholders that can assist members in terms of therapy, counselling, and dealing with other issues which could be beyond the scope of the garden members. This is something garden C practising by attempting to connect their members ot relevant authorities such as government agencies or social development organisations in situations that exceeds their capabilities.

As seen in the provided garden images, these areas are generally low-profile within their respective neighbourhoods. While accessibility can be an issue, it’s apparent that in many cases, due to fencing or the inherent location of these gardens, some form of regulation is necessary to ensure controlled access. While these gardens may partially embody third-place characteristics, they may not entirely encapsulate the essence of the concept. Open spaces in South Africa are prone to vandalism and crime (Perry et al., Citation2008) hence, fencing is implemented for valid reasons, to secure the garden’s sustainability (Kanosvamhira, Citation2023). In contrast, Glover (Citation2004) discusses fencing at a community garden in the midwestern United States as a means of excluding minorities from the garden, highlighting regional variations in the reasons behind implementing fencing. Despite being fenced, a garden like Garden B maintains its role as a third place effectively. Such security measures are often necessary in these communities to protect the gardens. Therefore, it’s vital to recognise the continued importance of these spaces in various contexts, even if they don’t meet all criteria. While their appearance may suggest exclusion, the study’s findings show that participation in these gardens entails responsibility, aligning with the gardens’ objectives (Neo & Chua, Citation2017). On the other hand, gardens located around the communal spaces such as those of Garden A tend to be more inclusive and accessible to the community by virtue of the location. Past studies have shown how community gardens close to the area of residence offer more health and mental advantages to the community (Gray et al., Citation2022).

Community gardens, exemplified by Garden A, effectively distinguish between regular members responsible for maintenance and levellers. Core team members, functioning as regulars, play a crucial role in welcoming visitors and fostering leadership and inclusion, facilitating seamless integration for newcomers. They also act as levellers, ensuring a harmonious and inclusive environment. These gardens thrive as enjoyable and conversational spaces, with members pausing activities to engage in discussions about various gardening endeavours. Diverse activities, such as open days and celebrations, extend beyond cultivation, engaging the community and contributing to a conversational and enjoyable atmosphere. The success of community gardens transcends third-place criteria, underscoring their profound significance and multifaceted contributions to the communities they serve. The interplay between regulars and levellers, coupled with the enjoyable and conversational nature of these spaces, reinforces their role as hubs of community engagement and interaction.

7. Conclusion

This study unveils the intricate dynamics between urban community gardens on the Cape Flats and the concept of the ‘third place’. Through four qualitative case studies, it becomes evident that these community gardens hold the potential to serve as significant third places, fostering informal interactions and social cohesion within the Cape Flats. The research findings reveal a spectrum of experiences across the identified community gardens. Some embody all essential characteristics of third places, especially those prioritising community development initiatives over economic models. However, others, influenced by economic factors, do not fully embrace these defining traits. Beyond their physical confines, these third-place community gardens demonstrate their capacity to promote inclusivity by engaging diverse neighbourhoods and extending their impact throughout the broader community. While they play a crucial role in facilitating social interaction, strengthening social bonds, and providing safe havens for citizens, it is essential to acknowledge that not all community gardens on the Cape Flats inherently function as third places.

This article promotes a nuanced view that considers contextual intricacies before labelling a space as exclusionary within community gardens. It emphasises the need to recognise and address nuanced dynamics associated with exclusion, highlighting the responsibility to fortify these spaces as third places. While striving for inclusivity, third places inherently exclude some individuals, emphasising the value of community membership and benefits. This aligns with prior research, emphasising the importance of fortifying third places, especially for individuals in distressed communities on the Cape Flats. Furthermore, while the analysis reveals alignment of certain community gardens with the ‘third place’ concept, it underscores the necessity for a nuanced and context-specific application of the theoretical framework. By delving into the unique dynamics, challenges, and contributions of these community gardens, the study enriches the ongoing theoretical discourse on the ‘third place’ and its relevance in diverse urban contexts. This highlights the nuanced theorisation of community gardens as valuable social spaces within specific contextual constraints and emphasises the need to consider the complexities of real-world settings in interpreting and applying theoretical concepts.

Additionally, this research is poised to stimulate critical inquiry among scholars, urging them to move beyond reliance solely upon established criteria of third places. It encourages scholars to meticulously account for the specific dynamics at play within the boundaries of their case studies, particularly in global South cities where motivations for community gardening may differ significantly from their global North counterparts. By scrutinising the intricacies of community gardening practices within diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts, scholars can cultivate a more nuanced understanding of third places as dynamic and contingent upon local conditions. This critical perspective not only enriches theoretical discourse but also informs practical interventions aimed at fostering inclusive and sustainable urban communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tinashe P. Kanosvamhira

Tinashe P. Kanosvamhira is a honorary research fellow in the Department of Geography, Environmental Studies and Tourism, University of the Western Cape, Bellville 7535, South Africa. His research primarily focuses on urban geography with a specific emphasis on sub-Saharan Africa. His diverse research interests encompass various socio-spatial issues, including sustainable infrastructures, governance, livelihood strategies of the less privileged, and food systems.

Notes

1. The term ‘Black’ is frequently employed in South Africa to describe all groups that were historically marginalised, although these groups were categorised as Black, Coloured, and Indian under the apartheid race laws. However, Colored individuals are commonly perceived as having a ‘mixed race’ background and have historically occupied a middle position within the racial hierarchy of South Africa

2. Established in 1982, Abalimi Bezekhaya is a non-profit micro-farming organisation dedicated to supporting impoverished individuals and communities in the Greater Cape Town area known as the Cape Flats. They assist these communities in establishing and maintaining vegetable gardens to supplement food supplies and create sustainable livelihoods.

3. To ensure ethical standards, the study obtained clearance from the relevant ethical review board (Reference Number: HS19/9/2) before commencing the data collection process. Strict compliance with the ethical certificate ensured that issues regarding anonymity, confidentiality, and consent of the research participants were upheld throughout the research.

4. The colours green, yellow, and red are used to indicate varying levels in terms of each category. Green indicates that the category is fully met, whereas yellow indicates the category is partially filled and red not fulfilled.

References

- Ali, M. (2021). Urbanization and energy consumption in sub-saharan Africa. Electricity Journal, 34(10), 107045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2021.107045

- Ali, S., & George, A. (2022). Redressing urban isolation: A multi-city case study in India. Journal of Urban Management, 11(3), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2022.04.006

- Battersby, J, & Marshak, M. (2013). Growing Communities: Integrating the Social and Economic Benefits of Urban Agriculture in Cape Town. Urban Forum, 24(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-013-9193-1

- Certomà, C., & Tornaghi, C. (2015). Political gardening. Transforming cities and political agency. Local Environment, 20(10), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1053724

- CoCT. (2016). State of Cape Town report 2016. City of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- Dolley, J. (2020). Community gardens as third places. Geographical Research, 58(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12395

- Eizenberg, E. (2012). Actually existing commons: Three moments of space of community gardens in New York City. Antipode, 44(3), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00892.x

- Engel Di Mauro, S. (2018). Urban community gardens, commons, and social reproduction: revisiting Silvia federici’s revolution at point zero. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(9), 1379–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1450731

- Firth, C., Maye, D., & Pearson, D. (2011). Developing ‘community’ in community gardens. Local Environment, 16(6), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.586025

- Follmann, A., & Viehoff, V. (2015). A green garden on red clay: Creating a new urban common as a form of political gardening in Cologne, Germany. Local Environment, 20(10), 1148–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.894966

- Geldenhuys, K. (2022). Crime series Atlantis’s New Year gang shoot-out: Part 1. Servamus Community-Based Safety and Security Magazine, 115(7), 1–13.

- Glover, T. D. (2004). Social capital in the lived experiences of community gardeners. Leisure Sciences, 26(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400490432064

- Gray, T., Truong, S., Ward, K., & Tracey, D. (2022). Community gardens as local learning environments in social housing contexts: Participant perceptions of enhanced wellbeing and community connection. Local Environment, 27(5), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2048255

- Guitart, D., Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2012). Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 11(4), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.007

- Heath, L., & Freestone, R. (2023). Redefining local social capital: The past, present and future of bowling clubs in Sydney. The Australian Geographer, 54(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2022.2144257

- Hencelová, P., Križan, F., Bilková, K., & Madajová, M. S. (2021). Does visiting a community garden enhance social relations? Evidence from an East European city. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography, 75(5), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2021.2006770

- Huron, A. (2015). Working with Strangers in Saturated Space: Reclaiming and Maintaining the Urban Commons. Antipode, 47(4), 963–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12141

- Hutchinson, S. L., & Gallant, K. A. (2016). Can senior centres be contexts for aging in third places. Journal of Leisure Research, 48(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2016-v48-i1-6263

- Kanosvamhira, T. P. (2019). The organisation of urban agriculture in Cape Town, South Africa: A social capital perspective. Development Southern Africa, 36(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2018.1456910

- Kanosvamhira, T. P. (2023). How do we get the community gardening? Grassroots perspectives from urban gardeners in cape town, South Africa. Journal of Cultural Geography, 40(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2023.2187509

- Kanosvamhira, T. P., & Tevera, D. (2020). Urban agriculture as a source of social capital in the cape flats of cape Town. African Geographical Review, 39(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2019.1665555

- Kanosvamhira, T. P., & Tevera, D. (2021). Food resilience and urban gardener networks in sub-saharan Africa: What can we learn from the experience of the cape flats in cape Town, South Africa? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211043919

- Kanosvamhira, T. P., & Tevera, D. (2024). Unveiling quiet activism: Urban community gardens as agents of food sovereignty. Geographical Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12661

- Kuzuoglu, S., & Glover, T. D. (2023). Social infrastructure: Directions for leisure studies. Leisure Sciences, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2023.2253230

- Littman, D. M. (2022). Third places, social capital, and sense of community as mechanisms of adaptive responding for young people who experience social marginalization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 69(3–4), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12531

- Mair, H. (2009). Club life: Third place and shared leisure in rural Canada. Leisure Sciences, 31(5), 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400903199740

- Malan, N. (2015). Urban farmers and urban agriculture in Johannesburg: Responding to the food resilience strategy. Agrekon, 54(2), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2015.1072997

- Melete, C., Ngin, M., & Chim, M. (2015). Urban markets as a ‘corrective’ to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore. Urban Studies, 52(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014524613

- Milbourne, P. (2021). Growing public spaces in the city: Community gardening and the making of new urban environments of publicness. Urban Studies, 58(14), 2901–2919. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020972281

- Modibedi, T. P., Masekoameng, M. R., & Maake, M. M. (2021). The contribution of urban community gardens to food availability in Emfuleni Local Municipality, Gauteng Province. Urban Ecosystems, 24(2), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-020-01036-9

- Neo, H., & Chua, C. Y. (2017). Beyond inclusion and exclusion: Community gardens as spaces of responsibility. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(3), 666–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1261687

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place. Paragon House.

- Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons and other hangouts at the heart of a community (2nd ed.). Marlowe.

- Olivier, D. W., & Heinecken, L. (2017). Beyond food security: Women’s experiences of urban agriculture in Cape Town. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(3), 743–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9773-0

- Olivier, D. W., & Heinecken, L. (2017). Beyond food security: women’s experiences of urban agriculture in Cape Town. Agriculture Human Values, 34(3), 743–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9773-0

- Paganini, N., & Lemke, S. (2020). “There is food we deserve, and there is food we do not deserve” Food injustice, place and power in urban agriculture in Cape Town and Maputo. Local Environment, 25(11–12), 1000–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2020.1853081

- Perry, E., Moodley, E., & Bob, U. (2008). Open spaces, nature and perceptions of safety in South Africa: A case study of reservoir hills, Durban. Alternation, 15(1), 240–276.

- Peters, D. (2016). Inked: Historic African-American beach site as collective memory and group ‘third place’ sociability on martha’s vineyard. Leisure Studies, 35(2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.986506

- Schmelzkopf, K. (1995). Urban Community Gardens as Contested Space. Geographical Review, 85(3), 364. https://doi.org/10.2307/215279

- Slater, R. (2001). Urban agriculture, gender and empowerment: An alternative view. Development Southern Africa, 18(5), 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350120097478

- Tembo, R., & Louw, J. (2013). Conceptualising and implementing two community gardening projects on the Cape Flats, Cape Town. Development Southern Africa, 30(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2013.797220

- Trendov, N. M. (2018). Comparative study on the motivations that drive urban community gardens in central eastern Europe. Annals of Agrarian Science, 16(1), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aasci.2017.10.003

- UN-DESA/PD (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division). (2018). The world’s cities in 2018-data booklet. https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

- Veen, E., Derkzen, P., & Visser, A. (2014). Shopping versus growing: Food acquisition habits of Dutch urban gardeners. Food & Foodways, 22(4), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2014.964604

- Veen, E. J., Bock, B. B., Van den Berg, W., Visser, A. J., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2016). Community gardening and social cohesion: Different designs, different motivations. Local Environment, 21(10), 1271–1287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1101433

- World Bank. (2019). World development report 2019: The changing nature of work. World Bank report. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/816281518818814423/pdf/2019-WDR-Report.pdf

- World Economic Forum. (2017). Migration and its impact on cities. World economic forum: Cologny. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Migration_Impact_Cities_report_2017_low.pdf

- Yuen, F., & Johnson, A. J. (2017). Leisure spaces, community, and third places. Leisure Sciences, 39(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1165638