ABSTRACT

Since the murder of George Floyd, there has been an increase in discussions around racism and anti-racist practice in social work. There have been questions about how pre-qualifying training prepares newly qualified social workers for working with racialised groups and dealing with racism in practice. This paper reports on a qualitative study with sixty-seven newly qualified social workers on the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme (a twelve-month employment-based course providing extra support and enhancing skills and knowledge for newly qualified social workers employed in England) within two years of completing a social work degree. Our analysis identified challenges in dealing with racism, experiences of racism and the lack of guidance on dealing with racism, witnessed and/or experienced. There is a need for organisations, and educators to develop a greater sense of racial consciousness to successfully drive anti-racism in social work. A framework that supports newly qualified social workers with processes to help challenge and address incidences of racism should encourage social workers to wrestle with race.

Introduction

The sustained continuation of racism is a public threat and affects social justice. Undoubtedly, the recent murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor demonstrate the draconian consequences of institutional racism. While there has been increased attention in discussing racism and seeking ways to tackle racism in social work education, health and social work practice, since then the struggle to address institutional racism continues. This is due to both the absence of unequivocal acceptance of institutional racism and the presence of inadequate structures to help tackle racism (Choonara, Citation2021). We argue that there is a need for social work education to strengthen anti-racism teaching, including a stronger focus on strategies to challenge racism.

Research confirms the existence of racism towards racialised people, whether overtly, covertly, or through micro-aggressions, in social work practice (Bernard, Citation2020). For example, there are disproportionate numbers of Black children on child protection plans and delays in adoptions for Black children remaining in care for extended periods; white children are less likely to be placed in care yet more likely to be adopted than Black children (Department for Education, Citation2021). Racial disparities in social care and health outcomes in health and social care, poor access to services, or punitive mental health treatment (Agarwal, Citation2020; Hackett et al., Citation2020), result in the ‘circles of fear’ that prevent ethnic minorities from seeking help (Singh, Citation2019). Such disparities have also been noted in policing, through racial profiling in disproportionate stop and search, the use of tasers, physical restraints of Black people, and young Black boys in the criminal justice system who continue to experience unfair trials (Lammy, Citation2017).

The teaching of anti-racism in the social work curriculum has been consumed by concepts such as anti-oppressive practice, power, and anti-discriminatory practices. McLaughlin (Citation2005) and G. Singh (Citation2014) argued that the move to place anti-racism under the umbrella of anti-oppressive practice was intended to prevent the hierarchy of oppression. However, further dilution of anti-racism is seen in terms such as diversity, inclusion, multiculturalism or cultural competence (Ladhani & Sitter, Citation2020). The use of these terms has led to some institutions misrepresenting themselves as being outstanding in dealing with matters relating to race. Yet, issues of race and racism are still not well understood as, often, they are simply associated with other forms of inequality (Graham & Schiele, Citation2010; Ladhani & Sitter, Citation2020).

According to Naseem (Citation2011) anti-racism education is important in addressing the power and inequality that cause racism. Importantly, it should involve untangling and understanding the structural roots, histories and political influences that result in racism while at the same time meeting the learning needs of both white and ethnic minority students (Singh, Citation2019). Without in-depth and reflective teaching about race and racism, a concern is that white students may work unknowingly and unquestioningly in practice, with little understanding or genuine appreciation about anti-racism. Ethnic minority students are silenced and often have little knowledge or skill to deal with race issues or racism (Singh, Citation2019). We argue that for anti-racism teaching to be effective, it should be rooted in theory, focused on the conscious, surface the reality of the serious impact racism and racial incivilities, and should be transformational.

Other studies argue that the effectiveness of anti-racism education comes from positive learning spaces that are empowering, that support an understanding of real-life experiences, reflection and critical thinking, and foster humanity and social justice (Cane, Citation2021; Fairtlough et al., Citation2014; Tedam, Citation2012). Thus, teaching should include the present context of racism and white supremacy in higher education, related violence, and the imperialistic and oppressive past. Notwithstanding, some regions within which social work institutions are located have benefited financially from the slave trade, and some research scholarship and theories favour racial inferiority that supports economic gains from slavery (King-Jordan & Gil, Citation2021). For this reason, teaching race, racism and anti-racism requires a particular and sensitive skill, given that the topic can be potentially controversial.

Therefore, it is important to stretch students into having uncomfortable conversations about whiteness and identifying their own privileges to facilitate growth while providing a sense of security to all involved in the learning (Cane, Citation2021; Singh, Citation2019). Crucially, anti-racist teaching should prepare students to challenge racism once they qualify. Those who have experienced racism should also be supported in the learning process and not be silenced or placed in spaces of vulnerability (Ladhani & Sitter, Citation2020). Once they are qualified, newly qualified social workers should be able to apply and enhance those skills in practice. Hence, the first few years post-qualifying are critical for newly qualified social workers.

Croisdale-Appleby argued that “the first year of practice is absolutely vital for social workers as they consolidate the learning from their degree and develop new knowledge and skills in their first employment setting’(2014, p. xiiii). Yet in (Tedam & Cane, Citationin press), the authors presented the view of newly qualified social workers with regard to anti-racist practice teaching in social work degrees. Participants reported that anti-racist practice is rarely taught as a standalone topic in the social work curriculum. Moreover, where race and anti-racism are taught, they are not explicit or well-integrated into the curriculum. Consequently, social work trainees graduate feeling ill-equipped to deal with race or racism issues. As a result, some newly qualified social workers feel less confident to engage with racialised minorities either on placement or once they commence post-qualifying practice (authors, in press). Of particular concern was the view by some participants that the murder of George Floyd gave impetus to open and honest discussions about racism and anti-racism, implying that the situation prior to this was woefully inadequate and, in many instances, absent. Much of the research looking at newly qualified social workers transitioning to practice has focused on consolidation of knowledge skills and development of analytical skills, reflection and understanding of risk. However, it reports that social workers often feel well or very well prepared for practice post-qualifying (Grant et al., Citation2017; Sharpe et al., Citation2011). Particularly in undertaking assessments, promoting and enabling, communicating and engaging (Lyons & Manion, Citation2004), building relationships, but lacking confidence in skills such as intervention and providing or dealing with budgets and finance (Carpenter, Shardlow, Patsios, & Wood, Citation2013; Pithouse & Scourfield, Citation2002). While none of these studies focused specifically on anti-racist practice, Bates et al. (Citation2010) considered newly qualified social workers readiness in additional aspects of practice, including anti-discriminatory practice and inter-professional working. They found that social workers felt confident in anti-discriminatory practice but unprepared for report-writing court-skills record keeping.

Universities generally do well in teaching students social work values, and undertaking practice related skills such as understanding risk, anti-oppressive and anti-discriminatory practice, and tackling complex aspects of practice and decision-making (Grant et al., Citation2017). However, newly qualified social workers have raised concerns about little opportunities for continuous professional development opportunities, inconsistencies in supervision and reality shock once in practice (Jack & Donnellan, Citation2010). However, no research has reported specifically on the effectiveness of anti-racist practice teaching among newly qualified social workers in the early stages of their career post-qualifying. This present paper is a follow-up paper on the authors’ research, which presents the challenges faced by newly qualified social workers, concerning matters of racism once qualified. As far as we are aware, our research is at the vanguard of research looking at the views of newly qualified social workers on the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme since the programme was launched in September 2012.

The aims of this study are (1) to establish the key barriers impacting newly qualified social workers’ confidence in dealing with matters of race and challenging racism once they complete training and during or within two years of the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment phase, and (2) to foster further discussions and consideration around the implementation of appropriate strategies to support all newly qualified social workers to deal with racism post-qualifying.

Conceptual framework

This paper will draw on the notion of ‘race wrestling’ (Pollock, Citation2006) as a conceptual framework. Pollock argues that everyday struggles of race and racial inequality are a reality. To address racism, people will need to consciously wrestle with normalised ideas that perpetuate racism and racial inequality. We argue that racial wrestling starts from the point of racial consciousness, which involves the awareness of status and identity based on ancestry and colour, and is associated with social classification, prejudice, ignorance and aggression (Cane, Citation2021). Racial consciousness calls for a critical appreciation of uneven power relations between racial groups, the understanding of privilege, and bias associated with race. In line with this argument, Pollock suggests that to address racism in social work practice, the following need to be achieved:

i. rejecting false notions of human difference through ‘actively treating people as equally human, worthy, intelligent and potentialed’ (Pollock, Citation2006, p. 9);

ii. acknowledging and engaging with the lived experiences of individuals along racial lines;

iii. capitalising, building upon, and celebrating diversities that have developed over time;

iv. equipping oneself and others to challenge racial inequality and challenging the widespread tendency to accept racial disparities in opportunity and outcome as a norm.

It is from these recommendations that we argue that wrestling with race requires social workers to understand their own racial identity and how this affects others. Social workers need to access the relevant training and education, and develop the right skills to challenge racism. This learning involves reflection and appreciation of the discomfort that may arise in understanding racial privilege and taking the right actions to challenge racism and becoming an anti-racist practitioner. We argue that social work pre-qualifying courses and indeed the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme, alongside other skills (e.g assessment and recording skills, decision making, analysis, risk and complexity) and knowledge (Carpenter et al., Citation2013; Grant et al., Citation2017), should equip readiness in students and newly qualified social workers respectively, to disrupt and challenge the racism experienced by service users, the self and colleagues to promote social justice. As Pollock (Citation2006) suggests, ‘everyday anti-racism in education involves clarifying any ways in which opportunities must still be equalised along racial lines and then equipping people to actually equalise life chances and opportunities arbitrarily reduced along racial lines’ (p. 10).

Terminology

We acknowledge that language and terms used to describe ethnic minorities or people from minoritised groups remain contentious. We use the term ‘ethnic minorities’ and people from minoritised groups interchangeably where views and experiences are generic or commonly shared by those who do not identify themselves as white. However, where individual participants self-define as White, Asian or Black, these distinctions will be made to ensure accuracy in presenting the views and experiences of those participants.

The study

We undertook a qualitative study by way of round-table focus group discussions with newly qualified social workers within two years post-qualifying except for one participant who was in their final year and completing their final placement of an undergraduate social work degree. The study was promoted through Twitter, reaching out to local social work partnerships and snowballing. Those interested in taking part contacted both researchers; they were provided with the study information pack, including consent forms and a link to Calendly—a platform where participants nominated a convenient date to attend a focus group. A day before the focus group, participants were reminded to read the research information packs and were provided with the Zoom link to join the focus group.

All participants had completed their social work degrees through either traditional or fast-track programmes (Frontline, Think Ahead and Step-Up) in England, bar one, who had trained in Scotland. At the time of the study, all participants were employed across local authorities in England in both adult and children’s sectors. Participants included white and ethnic minority social workers, including but not limited to Black and White African, Asian, Arab or Caribbean backgrounds. There was no restriction by ethnicity or cultural background. Thus, focus groups were mixed heterogeneously, enabling newly qualified social workers from different pre-registration programmes, with varying practice experience across various social work settings, to reflect together, and share their views about anti-racism teaching on pre-registration programmes and their experiences (authors, in press).

Our round-table discussions included sixty-seven participants and ten groups comprising between three and ten participants and were conducted virtually on Zoom. We presented ten open-ended questions to prompt reflective discussions. Sessions began by presenting a prompt question to encourage in-depth discussions. Once a question was exhausted, additional prompt questions were presented to generate further discussions. Before the round-table discussions commenced, a confidentiality statement and commitment to General Data Protection Regulation protocols were declared and consent forms signed through Qualtrics. Participants were requested and encouraged to use anonymous names or identifiers for the purpose of the research and to ensure confidentiality. Those joining late were required to follow the same process. Both researchers (TC and PT) were present to lead and moderate discussions for all sessions.

Each round-table discussion lasted ninety minutes, with the final thirty minutes dedicated to a presentation and reflection on the 4D2P (Discussing, Discovering, Decision-making, Disrupting, Power and Privilege—explained below) anti-racist framework (Tedam, Citation2021). The aim of this framework is to ‘assist social workers to understand the steps through which they can evaluate their own non-oppressive practice on an ongoing basis’ and develop effective practice. The aim was to offer participants a newly developed tool for practice with racialised and oppressed people who use services. In summary, the 4D2P involves a process of Discussing in a non-judgemental way the reasons and circumstances a service user is involved with social workers; Discovering one’s values and beliefs and those of service users, identifying oppression and putting together an action plan to address oppressive practice; Decision-making that promotes service-user participation and respecting their voice; and Disrupting, which involves interposing and changing oppressive practice. These 4Ds are underpinned by a process of acknowledging and evaluating the 2Ps, Power and Privilege that exist in the social work role and ensuring this does not undermine the process of challenging and disrupting racism or oppression (Tedam, Citation2021).

Our general observation about using round-table focus group discussions as a methodology was that this approach provided a catalyst for engaging in conversations with colleagues, working in different settings across the country, about the challenges, experiences, what is going well, and what is going not so well in regards to anti-racist practice. Some experiences were still raw, raising concerns about what has changed, how soon and when certain concerns about racism in social work will diminish. Participants were empathetic, passionate about the topic, welcomed the opportunity to share and reflect, and appreciated learning about the new 4D2P framework and how to apply it in practice.

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Sussex Research Committee in April 2021. Hence participant consent incorporated taking part in the study and the subsequent publication of the findings. Social work training institutions (including placements), organisations where participants were employed, and personal details were not disclosed to ensure confidentiality. In any case, that information was not required for the study.

All discussions were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifying details removed to ensure anonymity. Analysis followed Smith’s interpretative analysis adopted for focus groups data (Love et al., Citation2020). The process of double hermeneutics was applied, analysis and coding were conducted inductively by TC, and emerging themes were discussed and reviewed by PT. Themes were further refined into categories and confirmed. To remove bias, researchers engaged in self-reflective sessions at the end of each focus group and throughout the interpretive stages of the analysis.

Description of participants

Of the sixty-eight participants taking part in this study, thirty-eight had recently commenced the ASYE programme, eleven had reached a year post-qualifying, twelve fell within two years post-qualifying, one was completing their final year on the undergraduate course, two participants were between the third and fourth year of employment but still taking part in the ASYE programme. Participants were trained through a range of social work programmes with those trained on the traditional Bachelors (Honour) (n = 31), Postgraduate/Master of Arts/Sciences social work routes (n = 22), Frontline (n = 6), Think Ahead (n = 3) and Step-Up fast-track (n = 6) programmes, and one on a bespoke employment-based training route. All participants trained in England with the exception of one participant, who trained in Scotland. In terms of gender the figures were as follows: female (n = 55), male (n = 11), undisclosed (n = 1) and unreported (n = 1). We also asked participants to self-disclose their ethnicity and those identifying as white British/other white background (n = 28), Black-Black British/Black Caribbean/African (n = 24), mixed race (n = 6), Asian-British/Asian (n = 5), other (n = 1), unreported (n = 4). The highest age group was 25–34 (n = 20), 35–44 (n = 18), 45–54 (n = 17), 18–24 (n = 8), 55–64 (n = 3), (unreported = 12). The majority of participants, that is, fifty-eight were employed by the local authorities in England, four in the NHS, three were locum, and one was a school social worker.

Findings

A key issue identified by newly qualified social workers in this study was the range of barriers that prevented them from speaking about race openly, or challenging racism. They also highlighted layers of barriers that contributed to lack of confidence in wrestling with race or disrupting racism. For example, lack of managerial support, lack of support, lack of exposure to people of ethnic minority either at the university, on placements or in practice (teams or caseloads), fear of being labelled as problematic, and angry or fear of losing a job.

Recognition that racism should be taken seriously

As a starting point, it is important to highlight that all newly qualified social workers who took part in this study, whatever their ethnic backgrounds, recognised that racism exists across all aspects of social work practice. Furthermore, they all agreed that taking a colour-blind approach in social work will increase oppressive practice and, therefore, where concerns about racism are reported, disclosed or witnessed, this needed to be taken seriously:

Recognising that actually if they’ve [service users] said that to me they experienced racism and that that’s something that needs to be taken seriously. Not to brush it off or attribute it to something else. A(FG2)

Participants had all witnessed racism in practice or heard of cases where service users or colleagues had experienced racism. However, the murder of George Floyd had created a sense of urgency in seeking more understanding around race and racism and becoming better at the practice of being, doing, and acting anti-racist. However, one major drawback was the lack of knowledge or skill in addressing or challenging concerns about racism.

Observing racial discrimination without support to address oppressive practice

We present one of many scenarios that were discussed, where newly qualified social workers perceived racism in their service and were unsure how to deal with what they deemed to be oppressive practice. I(FG4) expressed her concerns regarding how social workers in mental health teams failed to appreciate or empathise with the realities and experiences of Black people accessing mental health services. She had witnessed a case where a Black service user had received inadequate treatment, was prescribed high doses of anti-psychotic medicine, was involuntarily admitted into hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983, and was admitted to high profile mental health institutions but with no history recorded of symptoms of serious mental health problems or psychosis in the past fifteen to twenty years. I(FG4) was concerned about the absence of review and the lack of responsiveness to the service user’s current mental health status. She reported:

The case notes from the psychiatrist said that there were no signs of mental disorder or anything … I challenged it. They were like, what can we do now? If we try and take her off the medication it’s going to cause her more problems. I was like but she was racially profiled, she’s essentially lost her human rights. She had her children taken off her. She was in these institutions. She’s essentially been drugged with anti-psychotic medication without any mental health problems. I didn’t know how to push forwards, what else to do, what things I could try to give this woman her life back and bring her justice. There wasn’t a, right, we need to try and figure out what to do, let’s plan something, let’s take this further. I was left with it, and it was really heavy on me … [The service user], was like, I was told I needed the medication. She didn’t really understand why she’d been given the diagnosis, it had been 40 years. If she’s accepted it and she doesn’t have a problem with it, is that because she’s internalised this oppression or racism? I(FG4)

Inequalities exist in patients accessing mental health services as well as around the treatments offered (Koodum et al., Citation2021). Memon et al. (Citation2016) identified cultural naivety, insensitivity, and inappropriate and inadequate responses to the needs of ethnic minorities in the mental health services. However, the experience of helplessness in the excerpt above was not isolated. There is an evident sense of powerlessness for both the service user and the newly qualified social worker.

Other participants relayed how they witnessed oppressive practices in children and adult services. It was common across most group discussions that newly qualified social workers felt stuck when incidences of racism or racial profiling were perceived.

While newly qualified social workers were clear about their role in opposing, challenging or interrogating oppressive practices, disrupting such patterns seemed difficult when structural racism appeared to be normalised. There was a general sense that some teams or individuals in senior positions were incompetent in addressing racial oppression and promoting anti-racist practice. This was deemed unhelpful by newly qualified social workers who required case direction. This finding is consistent with Butt (Citation2006), who reported that white managers could not provide direction to Black and ethnic minority social workers as they felt they did not possess the skills to work effectively with Black and ethnic minority families, suggesting little progress since Butt’s work.

Witnessing racism in multi-agency working forums

While most participants said they lacked confidence in challenging racism, one participant from a racialised minority group, reported that she did have the confidence to have difficult conversations about racism. She reported that general life experience as a middle-aged person, and lived experience of racism, had taught her to stand up and be confident in challenging racism

I feel quite prepared to be able to talk about things. I recently worked with a family whom I very much felt that in terms of some of the other agencies that I was working alongside, that actually this woman and family were being treated the way they were being treated because of their ethnicity and colour. I talked it through in supervision first … and addressed it with some of the other agencies. I felt that, if they were a middle-class white family, they might have been dealt with very differently by some of the other professionals that were working with them. (FG2)

Ethnic minority social workers experiencing racism and lacking managerial support

It is accepted that social workers from racialised minorities also experience racism from service users and colleagues. However, they can struggle to challenge racism targeted at them directly as individuals compared to that against service users if there is little organisational support (Obasi, Citation2021a). In our study, we found that almost all the participants from racialised groups, whether on the pre-registration programme or the ASYE programme, had not received adequate training on the strategies needed to challenge racism targeted towards them by service users, or what to do if their managers were unsupportive:

I would have liked to hear [on the pre-qualifying course] more about how to challenge racism as a practitioner. Because you’re the professional and if you go to somebody’s home for an assessment and they’re being racially abusive to you, how do you deal with that because you have to be professional at the same time … In cases where somebody is saying I don’t want to work with a Black person, and you get stuck. The case will be removed from you but then if nothing is done about that … sometimes you’re like, okay, if 30 or 40 or 50 people say they don’t want to work with you and those cases keep getting removed from you how do I deal with that. It obviously leaves me feeling not so well. It leaves questions in your head because management will take those cases from you to say this person does not want to work with a Black person. How do we challenge this kind of behaviour? From the top down or down to the top, I don’t know. I would love to see something to say how you can challenge it, but when the other person is the one who is deemed vulnerable, we [the organisation] are not really prepared to deal with that. LA

We heard of numerous incidents where cases were removed from either a Black or Asian social worker who had been subjected to racism but that their managers had failed to address the situation going forward. There is a sense that because service users were vulnerable and in need of services, challenging their racist behaviour was less of a priority. The question of whose feelings or justice is noteworthy was raised. Regardless of ethnic background, participants were adamant that managers should ‘back up’ ethnic minority social workers when they are subjected to racism. They expressed a sense of anger and dissatisfaction with managers or supervisors who turn a blind eye to racism experienced by fellow colleagues of racialised minority backgrounds. In other words, the ‘customer is always right’ approach to racism, maintains the status quo. It sweeps racism under the carpet, failing to recognise the impact of racism on social workers. The lack of leadership or true allyship sometimes demonstrated management’s and supervisors’ masks and promoted ongoing racism and micro-aggressions.

Lack of skill to challenge colleagues

In light of the lack of support for those experiencing racism, one Black male participant working in child protection expressed a real sense of concern regarding the possible hostility he may experience if he were involved in removing a child into care. He was concerned about what might happen to his employment if he were racially abused during the process and if his managers failed to believe him or ‘back him up’. Brady-Williams (Citation2018), reporting on research findings relating to experiences of Black social workers, argued that Black social workers often face a high level of scrutiny compared to their counterparts, their professionalism is constantly questioned, leaving them with feelings of inadequacy. She argued that when intervening with families, Black male social workers are often seen as perpetuating oppression and discrimination and are wrongly accused of being aggressive. The Black male social worker determinedly stated:

You can imagine how families will react when I am removing a child because of child protection concerns and whether managers will support me. D(FG6)

As with most of the participants, his concern was around the lack of support from management given his gender and race. On the other hand, this participant also felt ill-equipped to challenge managers or colleagues as they either felt inexperienced as a junior member of the team or feared fracturing their working relationships:

I think sometimes it’s really hard to challenge the issues when you’re the most junior member of staff. You’re sitting in group supervision hearing people saying negative stereotypical language and you’re the most junior staff. It’s really difficult to challenge. Well, I found it really difficult to challenge it, especially in the moment. D(FG6)

Fear of challenging negative stereotypes in the moment was associated with inexperience, worrying about using an ineffective strategy, the process itself being ineffective, and worry that others may not be supportive or receptive.

Fear of whistle-blowing

Mbarushimana and Robbins (Citation2015) found that when social workers report racism, management do not always take concerns seriously and the struggles of Black social workers who experience racism are not well understood. Generally, participants described a fear of whistle-blowing due to the real possibility of losing their jobs or becoming unemployable in the future. A profound sense of fear, vulnerability and powerlessness among social workers from racialised groups, in particular, was reported:

I asked the question if you whistle-blow and you speak up, what does that do for you as a worker, as a professional in your future career? Someone made the comment that you’re kind of seen as unemployable. If you speak up, where do you go? For someone from our backgrounds [Black] it’s so difficult to get to a position of power. You have to work harder. There’s so much fear instilled within you as a practitioner, as a person, as an individual, that it really creates this bubble of oppression. That no one really tries to assist you to come out of, if that makes sense? HR(FG10)

Even those ethnic minorities who felt able to report racism through formal procedures were worried, anxious and unsure about how best to deal with the racism that they experienced from their colleagues

I’d be quite worried about how to approach it, I would potentially go quite a procedural route and go down a complaint Equality Act kind of route. Management, bring them in, just probably because of my own anxieties around it and not knowing the best way to approach it. CO(FG2)

Concerns regarding social workers of minoritised ethnic groups feeling silenced due to the fear of unemployment have also been reported by Patrick (Citation2020) who highlights the vulnerabilities of people of minoritised ethnic groups who are deemed to constantly wrestle with race, grappling with the competing values of others in the work environment.

‘We don’t want that stigma attached to us that we’re angry all the time’

It is widely accepted that race-based stereotypes adversely affect the careers of ethnic minorities and their relationships with colleagues (Obasi, Citation2021b; Ross, Citation2019). Some participants reported micro-aggressions associated with stereotypes, such as ‘crazy’, ‘forceful’, ‘an angry Black woman’, assigned to Black and Asian women in this study who had previously challenged oppression or racist views. Due to fear of receiving stereotypes or labels, some Black and Asian newly qualified social workers lost confidence or became reluctant to raise concerns regularly:

I don’t feel like I can speak out about certain things because I’m seen as the angry Black woman and I’m just feeding into the racist ideas that already exist … Sometimes you don’t want to feed into the narrative that already exists, I guess. Having that theory there or having a framework there is really helpful because you can go back to it. Say this exists and this says that we should do it like this. I think it would be helpful to have a framework because I really struggled. I(FG4)

Another reason some participants found it difficult to challenge racism was fear of being labelled as not resilient. One participant in particular, spoke strongly about how resilience has been a buzzword in their training and that it is an expectation. However, there was a concern that the term ‘resilience’ was not well understood where people are concerned about racism and the emotional impact it can have on victims. S(FG5) expressed concerns that when challenging racism and expressing emotions associated with racism, blame can be placed on the victim and they can subsequently be labelled as the perpetrator. She reported:

A lot of the times when you do bring it up, the person starts getting upset saying I didn’t mean it like that and then it gets brushed under the carpet. Then you are so frustrated that you want to still talk about it, you want it to be resolved instead of being brushed under the carpet. Then you are seen as a perpetrator. Either we don’t talk about it, and we face this, and we continuously face this and our service users face this, or we stand up and are looked at as the perpetrators that we don’t let things go, be angry. We don’t want that stigma attached to us that we’re angry all the time. We want to fight, and we want to argue about things, but this is how we feel. When the protests were happening about Black Lives Matter, one of my colleagues said there was no such thing as racism. I had this full-blown argument about it and, again, I was seen as someone that was just very angry. I was asked why are you so angry? We’re constantly pressured to stay quiet. But you should never be silenced about this matter; we just have to keep giving ourselves a voice as well as our service users. S(FG5)

Alcoff (Citation2002) argued that white social workers can feel threatened when people from minoritised ethnic groups disrupt the norms of the ‘white world’, leaving them (minoritised people) in a position where they either feel silenced or resist this threat. Refraining from raising complaints was seen as a strategy to cope or protect oneself from the humiliation or the frustration associated with racism in the social work environment.

As such, most participants wanted to see a framework or at least some clear guidance to help them deal with difficult experiences of racism, whether witnessed, experienced or reported by service users. However, most participants, be they white or from racialised minorities, believed that a framework to deal with racism was less likely to be effective unless an organisation was committed to change:

If your manager said there’s nothing we can do about it, we are left still stuck in that situation. I think something has to be done about it. But because there is no framework, there’s nothing to guide, you’re just sat there feeling guilty. You do feel that you can help this person but there’s nothing you can do. If there is a framework to guide you on your next steps in such situations, I think it will be very useful. C(FG4)

I feel as though your framework is only as good as the organisation. That’s any framework whether it’s anti-oppressive practice, whether it’s gender equality. TA(FG4)

Layers of barriers to developing skills and confidence in challenging racism

Lack of diversity in some organisations

All participants believed that numerous barriers prevented individual social workers, or their employing organisations, from tackling racism, with one such barrier being the lack of diversity in social work teams:

I don’t have any Black colleagues within my team, and this wasn’t brought up at all at our university. We used to have visiting service users and there was a service-user group which had lots of input into the course. We did have a Black woman who had adopted, and she talked about race in terms of her experience, but I would have liked to have had more service-user input. I would have liked to have had more ASYEs or practising social workers to talk about their experiences and I might have heard about these experiences that I’m hearing today more. SS

It can be argued that the notion that Black students are recruited in comparatively higher numbers onto social work programmes and in employment, as noted by Tinarwo (Citation2017) and Obasi (Citation2022), does not necessarily mean social workers from minoritised ethnic backgrounds are represented in teams across the country, or that their lived experiences are understood.

Lack of exposure and understanding

Research suggests that white professionals working with ethnic minorities, and with little experience or confidence in discussing race and racism openly, worry about making mistakes and fear being labelled racists and therefore avoid the subject (Singh, Citation2019). Another barrier was the lack of understanding that may arise from whiteness, and the lack of exposure or experience in engaging with ethnic minorities or other cultures

So, a lot of the social workers that I’m working with, a lot of them don’t have a lot of experience in that either. When we go to certain areas of our population where there is more diverse culture, nobody knows what to do. Everybody is like I don’t really know what to do, we’ll just have to ring an interpreter. It’s like you bungle your way through it because there’s not been any guidance at all. L(FG5)

Where I live right now it’s almost like an isolated area for Black people. It’s a community where it’s predominantly white people and I think you would need to walk for a few days to see another Black person in my community. That’s one of the real problems that we’ve had in my organisation, they don’t actually understand what it is to be somebody of ethnic minority. With some of my colleagues we’ve had to work really hard to try and bring the issue of racism into the organisation … S(FG4)

Discussing racism in teams is avoided

The lack of interest in discussing racism in teams or training sessions was noted. ‘Collective strategic projection’ is a term used in other research to describe how teams or colleagues may deter, prevent or obfuscate ethnic minority personnel from bringing up the issue of race or racism for discussion (Obasi, Citation2021a). One participant explained how racism as a topic is avoided or overtaken by other preferred topics:

There’s a problem, when we have diversity training, every time we try to bring up the topic [of] racism, it got changed … I think we had the training after George Floyd’s death, and we were talking about racism and stuff like that. But within five minutes of talking about racism somebody comes up and changes the subject … I think what all of you guys are saying is there’s something uncomfortable about talking about racism. One colleague said to me I grew up and I didn’t actually get to meet Black people and they’re scared to say things because it might come out wrong. NE(FG9)

Under-representation in senior roles and in academia

Existing research in health and social work shows how senior positions in this sector are held by predominantly white personnel, and that working environments with mostly white staff can be hostile, negative, and disempowering if they are less open to doing better in recognising racism and improving anti-racism (Bernard, Citation2020; Ross, Citation2019). Most participants identified the lack of representation of ethnic minorities in academia with some reporting an absence of teaching staff from minoritised ethnic groups. Others reported the lack of representation in senior management teams as a barrier to discussing race and addressing racism in social work:

One of the barriers for me is lack of representation in the higher positions in organisations. In our organisation I can tell you all the way down there is no one from an ethnic minority group … There’s not much commitment to that because that doesn’t really affect them that much. If we had that representation at the top where people have those lived experiences and they can trickle that down, I think training would probably be better and then things would probably get a lot better. It’s a bit frustrating sometimes when you feel like you want to make progress, but nothing is happening because they don’t actually understand themselves. S(FG4)

Some participants explained how the lack of opportunities to work with ethnic minorities prevented them from developing competence in anti-racism as they worked in less diverse regions:

In XXX and in my workplace, it isn’t as ethnically diverse as other parts of the country, and I think, you know, that is always going to be an issue in terms of me gaining further experience and other colleagues. Families are mostly white British families, so having the opportunity to have those experiences in work is not always going to happen. (JFG1)

My entire caseload is from a white British background – it’s quite interesting actually because in terms of my colleagues, we’re quite diverse. (AFG1)

Lack of exposure or experience with minoritised people during training

As well as working in predominantly white teams, some newly qualified social workers had limited exposure to diversity during training. Therefore, this lack of exposure was a barrier to developing an understanding of race and anti-racism:

On our [fast-track] programme I think out of 100 of us there was only eight from Black and minority ethnic. R(FG8)

I would have to echo that kind of imbalance of styles on the XXX fast-track programme. We had about 110 students on our cohort, but we were in person as well for the first year of our programme. I think we had maybe ten or eleven people who are of an ethnic minority background. I remember walking into the room for the first time and having a bit of a panic attack. I was the only person who was wearing a scarf. Very uncomfortable as well at first for the first couple of weeks. Did the programme prepare me for anti-racist practice in the learning? I don’t think it did. I(FG4)

XXX [city] is extremely multicultural. I remember walking into the room at the university and there were sixty-six people and only six were of an ethnic minority background. The entire room was literally white. I can’t put it in a different way. One of the other students from a small village had never interacted with anyone from an ethnic minority background. As the six people, she had seen it as, oh wow, this is an experience. TA(FG4)

The excerpts reporting under-representation of social workers from minoritised groups suggests geographical discrepancies. It was clear from some participants that their geographical location was predominantly white due to either socio-economic or political reasons. On the other hand, the lack of diversity reported in fast-track programmes was astounding compared to other social work programmes. Listening to participants, there was an inference that disparities in recruitment, and selection processes as well as the learning environment on fast-track programmes was not always welcoming to students from minoritised ethnic groups, suggesting an element of bias and racial inequality.

Little commitment in addressing racism

Given the range of barriers and experiences reported above, and with the exception of only a handful of notable experiences, the majority of participants felt their employers were not committed to anti-racism. Where conversations had begun to take place since George Floyd’s murder, concerns were that many discussions were tokenistic

The organisation that I work with is very committed to anti-racist practice, but very much as a tick-box exercise. It just doesn’t feel genuine sometimes. It’s like let’s go through the social graces before we discuss … right, we’ll tick that off. It’s almost done in a tokenistic way. There’s not much of a commitment to actually make it meaningful. Z(FG4)

I think for me it’s about the idea of it being a forced conversation because something’s happened. It’s only being brought up because we have to do it and it’s not explored enough by everyone that’s involved. SO(FG4)

Little commitment or a lack of conversations about race are perceived, some social workers reported making it their responsibility to create space or encourage these conversations at individual or team levels. ‘If I don’t, no one else will’:

One of the things that I’ve tried and used on my colleagues at the moment as well is unconscious bias. I always try and emphasise that every time you do something just think about your biases. S(FG4)

What I tend to do in my team meetings, I try and bring the topic of race and inequality, I bring it to the forefront. You do hesitate because you think are you going to be seen as somebody who’s always pushing this agenda. But if nobody is going to be pushing the agenda, then it’s not going to be on the agenda, is it, really? It’s courageous conversations, really reflecting on your thought process as well. Z(FG4)

Overall, our participants wanted pre-registration and Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programmes to teach them the fundamental skills they need to work with ethnic minorities and to be genuine anti-racist practitioners. Furthermore, they wanted to know how to apply those skills with confidence and without having cultural misunderstandings and making mistakes when assessing and managing risk in their day-to-day practice:

I would have liked to have learnt different cultural values … where aggressive speaking is not a form of abuse like we would see it in a white culture, that we have to be softly spoken, you have to have a [stiff] upper lip. Different cultures are different, and I would have liked to have learnt that and learnt how to address that. MG(FG3)

Teaching about risk. For example, … I think it’s called Mongolian blue spots that are sometimes on Black children. Melanated babies, they are born with these marks on their backs, on their bums … How can we be safeguarding as professionals [when] we’re not aware of something like a Mongolian blue mark that we might see? It might be escalated for no reason and it’s literally something that a child is born with. It just helps us not to act risk averse and sometimes oppress families when it’s literally a lack of knowledge and children aren’t actually at risk. DW(FG3)

Overall, findings suggest multiple layers of barriers that prevent them from developing confidence in challenging racism. These barriers begin at pre-registration, following through post-qualifying stages of the social work career journey. We believe that understanding how these barriers affect the lived experience of social workers is crucial in disrupting these barriers to ensure genuine anti-racist actions in social work environments. If confidence to deal with racism is instilled and developed by the end of the pre-qualifying stage first, then on the ASYE programme, newly qualified social workers will surely continue their career journey with much greater skill in addressing racism. Failure to do so will come in the way of genuinely achieving anti-racism in social work.

Discussion

This study gives a voice to newly qualified social workers on the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme. The lived experiences expressed through powerful quotations affirm that social workers completing social work programmes commence employment with little knowledge of how to challenge racism, whether in respect of service users, themselves or their colleagues. When on the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme, there is little training to support newly qualified social workers to develop this important skill. Previous research has demonstrated the importance of teaching anti-racist practice on social work pre-qualifying programmes to prepare students to work with minoritised ethnic groups, engage in courageous conversations around race, and challenge and disrupt racism (Cane, Citation2021; Hollinrake, Hunt, Dix, & Wagner, Citation2019). However, our study suggests that teaching is not preparing newly qualified social workers enough to challenge racism. Whatever barriers come in the way of adequately teaching about race, research suggests that some academics struggle routinely with basic quandaries of race talk, racial difference, racism and its impact. Pollock (Citation2004) argues that educators and researchers should not mask everyday struggles linked to racial issues or bury messy arguments of everyday racism. Allowing such shortfalls in social work education has real consequences of harming not just the students, or social workers but service users.

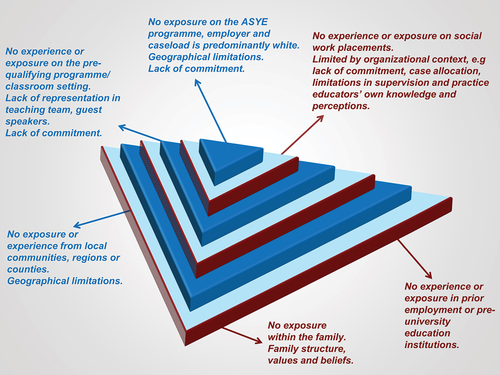

Instead of a step-up process through pre-qualifying training and the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programmes to support the development of skills, understanding and confidence in anti-racist practice, we found that there is a layering process creating multiple layers of barriers that prevent social workers from developing the adequate skills to challenge racism, as depicted in . Some individuals went through all the layers. That is, having no exposure to interacting or engaging with someone from a minoritised ethnic group due to their own family structures, community, social work training and in post-qualifying practice. The absence of experience or exposure significantly impacted on developing the right skills to challenge racism, making it very hard to find the right approach quickly enough in these early stages of their career. Others wrestled with dilemmas such as speaking in racial terms about one another or the role of race in education and training, the work environment, or in the lives of the service users they work with.

Figure 1. Layers of barriers preventing social workers from developing adequate skills to challenge racism.

Participants were keen to improve and develop antiracist practice, however for some, resistance to engage in race talk came about because they were unsure when it would be appropriate, or safe rather than beneficial. Thus, what they wrestled with was the struggle over talking, how often to talk, and how safe it is to talk in racial terms (Pollock, Citation2004). Despite the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme generally being considered a helpful programme that fosters confidence and practice competencies among newly qualified social workers (Carpenter et al., Citation2015), those required to work with ethnic minorities or to challenge racism for the first time (with no previous experience of engaging with ethnic minorities), may experience a baptism of fire and low self-efficacy linked to the fear of getting it wrong. Casey and Singh (Citation2019) also identified that the fear of making mistakes and the fear of being labelled as racist are associated with the lack of exposure, inexperience in interacting with, and the absence of learning from, people of minoritised groups. Despite social work being a profession that promotes social justice, newly qualified social workers frequently come across or witness racism, the incidence of racial profiling and micro-aggressions. These continue to persist as they are not addressed adequately due to the lack of skill and experience, the fear of losing employment, and a lack of confidence (Perez, Citation2021). Additionally, racism in social work environments goes unchallenged as social workers of minoritised backgrounds are silenced (Obasi, Citation2021a).

Although a minority with either lived experience or strong personalities reported the confidence to challenge racism, they do so not because social work training adequately prepared them for the realities of racism, but because of their own passion, and because they are risk takers. This finding supports other studies reporting that Black and Asian minority social workers can have the courage to challenge racism on behalf of service users due to their own lived experiences. However, in teams that are resistant to discussing racism, it often causes discord. Generally, all participants had the appetite to develop the relevant skills to disrupt racism. The fact that newly qualified social workers have found no helpful procedures with which to challenge racism leaves those who are keen to disrupt racism and oppression feeling stuck. A comprehensive framework would help provide clear guidance on dealing with racism in the work environment. However, most participants were less convinced that a framework would be effective, particularly in organisations where efforts to tackle racism are considered ‘tokenistic’ or ‘simply a tick-box’ exercise. We therefore recommend replacing unhelpful/unsupportive processes with helpful, clear, high- quality and non-punitive procedural guidance and information on what constitutes good practice for challenging racism (Bhatti-Sinclair, Citation2011). Attention should be paid to ensuring sensitive approaches, underpinned by genuine commitment to antiracism without gate-keeping or silencing victims.

Our findings agree with other studies reporting tokenistic approaches to dealing with racism (Arday, Citation2018). We argue that organisations should be ready and willing to wrestle with race through the implementation of the right space, structures and process to challenge racism and address white fragility. It is important for universities, fast-track programmes and emerging bespoke pre-qualifying training programmes and the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programmes to provide detailed teaching around challenging racism, whether as a victim or a witness. Employing organisations also need to show commitment so that newly qualified social workers develop trust and confidence that whatever strategies and frameworks are implemented, they are genuine and effective.

Listening to newly qualified social workers from racialised minorities, particularly Black and Asian social workers, they continue to feel vulnerable to micro-aggressions and racism and thus feel unable to challenge racism. Wrestling with race could include examining racial identity and ‘developing skills that increase risk taking, courage and self-awareness’ (Patrick, Citation2020, p. 209) and grappling with conflicting values. One of the problems identified, however, is the lack of diversity and the under-representation of ethnic minorities in certain teams or in senior positions. This lack of representation has led to Black and Asian social workers being labelled as angry or lacking resilience when they are emotionally disturbed by racism they witness in the workplace. Similar to Arday (Citation2018), who argues that Black and Minority Ethnic Academics are required to suppress their suffering, even when they experience racism, due to the need to remain professional, social workers have found it difficult to deal with racism perpetrated by their colleagues, senior colleagues and service users. As such, they feel isolated and silenced due to racial micro-aggressions and the fear of being called angry or accused of lacking resilience. Race wrestling involves disrupting an environment that promotes colour-muting, silencing victims of racism and micro-aggressions, and challenging oversimplified ways of understanding diversity while encouraging critical reflection, racial consciousness, self-awareness and skills of anti-racist practice (Patrick, Citation2020).

Hence, where racism is observed, newly qualified social workers are hesitant to whistle-blow due to the fear of becoming unemployable. It is evident that when social workers are recipients of racism, the priority is placed on the needs and vulnerability of service users rather than addressing the racism experienced by the social worker, although both are important. As Badwall (Citation2013) argued, revealing racism results in organisational discomfort and it ‘transgresses the established professional norms of the organisation that work to silence race’ (p. 75). This discomfort is often avoided by reallocating cases to avoid challenging racism perpetrated by service users. However, simply reallocating cases when social workers from minoritised ethnic groups report racism does not deal with the problem of racism in social work. Wrestling with race means challenging approaches that seem to suggest that the customer’s approach is the best while dismissing discrimination experienced by ethnic minority social workers—these approaches are not pertinent where racism is concerned, they mask the problem of racism in social work, encourage colour-blind approaches, promote white power, leave social workers vulnerable to further incidences of racism, and lead to allies of anti-racism feeling unsupported by their employers. Indeed, these barriers are linked to institutional racism that persists and complacency where managers or leaders can only describe intentions to address racism but fail to commit to actions or deliver. As such, social work managers and senior leaders should provide working environments that are safe, reflect social work values and social justice, and are open to be challenged and transformed to model anti-racist practice. There is a real need to challenge and disrupt organisational cultures that perpetuate racism.

The lack of exposure to different cultures, the lack of experience in working with ethnic minorities, in practice or during training, and the under-representation of ethnic minorities in social work education faculties are not new issues (Bernard, Citation2020; Cane, Citation2021). They significantly contribute to the lack of confidence in dealing with issues that relate to race and racism. Therefore, the long-term vision for anti-racist practice in social work should be re-established from the entry level into training, pre-registration and throughout, and post the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme. However, this will be undermined by the multi-layering of barriers our participants have seen across all stages of establishing their careers in social work unless there are considerable cultural and systemic shifts. The role of social work education is therefore to wrestle with these barriers and provide opportunities for students to learn about, and with, others from minoritised ethnic groups and to disrupt, in some cases, the inherent belief that Eurocentrism and models of working that favour the white dominant perspective are the only approaches to social work education, training, and practice as reported by some participants. Significantly, there need to be opportunities for newly qualified social workers on ASYE programmes for enhanced learning, support, guidance and mentorship as well as a review of the curriculum and organisational structures that continue to prevent social workers, both with or without prior experience, from developing confidence in dealing with racism.

Recommendations/implications for education and practice

Social work educators and employers need to recognise that some newly qualified social workers have had limited exposure to different cultures and require further detailed training on race, racism and strategies to promote anti-racist practice and challenge racially oppressive practices that they witness in the workplace.

Our study recommends ongoing open and genuine conversations about race, racism, and understanding of the impact of racial discrimination and micro-aggressions towards service users and social workers from racialised minority groups. These should happen in social work placements, classrooms, on the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment programme as well as workplace supervisions on a 1–1 basis or in clinical group supervision sessions.

It is also important for university programmes to commit to the decolonisation agenda, ensure diversity on social work programmes and encourage placement providers to offer a diverse caseload that allows social work students to engage, work with and learn from caseloads that include ethnic minorities.

Institutional racism will need to be confronted by employers and educational institutions to prevent colour blindness and perpetuate racism. In revisiting the idea of wrestling race and racial consciousness, we emphasise that educators, ASYE leads and employers should

i. actively promote racial awareness, critical self-reflection and racial consciousness;

ii. appreciate that racism continues to exist, is perpetuated by resistance to changing the norms that are racially oppressive, and that therefore racial disparities are not to be accepted as normal;

iii. acknowledge and engage with lived experiences of racialised minority ethnic people;

iv. equip oneself to wrestle with your own struggles over race and consider making empathetic decisions about the best ways to support those really affected by day-to-day struggles related to race; and

v. prepare others to develop the skills to challenge racism/racial inequality.

Limitations

While it is a strength of our study that black and white voices shared their experiences together in round-table discussions, some groups, however, were dominated by the voices of ethnic minorities who had experienced racism, struggled to navigate work structures or to challenge racism in their places of work. The strength in these instances is that these participants were supported by their counterparts, who also gained some learning from these sensitive, yet powerful and robust discussions. Although participants found it helpful to be involved in a space where they could speak openly about individual experiences, and those perceived of service users as well as difficulties with certain decisions made by managers, one limitation was the lack of representation from service users or managers. However, the focus of the study was on newly qualified social workers. Future research is needed to explore the coping strategies of newly qualified social workers struggling to challenge racism or navigate whistle-blowing policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tam Chipawe Cane

Dr Tam Chipawe Cane is a lecturer and Course Convenor for BA Social Work in the Department of Social Work and Social Care at the University of Sussex.

Prospera Tedam

Dr Prospera Tedam (SFHEA) is an Associate Professor and Chair of Department at the United Arab Emirates University. She is also an Honorary Visiting Fellow for Social Work at Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge.

References

- Agarwal, P. (2020). Sway: Unravelling Unconscious Bias. Bloomsbury.

- Alcoff, L. (2002). Toward a phenomenology of racial embodiment. In R. Bernasconi (Ed.), Race (pp. 267–283). Blackwell.

- Arday, J. (2018). Understanding race and educational leadership in higher education: Exploring the black and ethnic minority (BME) experience. Management in Education, 32(4), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020618791002

- Ashe, S. D., & Nazroo, J. (2015). Equality, diversity and racism in the workplace: A qualitative analysis of the 2015 race at work survey. ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity, University of Manchester. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/code/research/raceatwork/Equality-Diversity-and-Racism-in-the-Workplace-Full-Report.pdf

- Badwall, H. (2013). Can I be a good social worker? Racialized workers narrate their experiences with racism in every day practice (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

- Bates, N., Immins, T., Parker, J., Keen, S., Rutter, L., Brown, K., & Zsigo, S. ((2010)). ‘Baptism of fire: The first year in the life of a newly qualified social worker. Social Work Education, 29(2), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470902856697

- Bernard, C. (2020). PSDP- Resources for managers of practice supervisors: Addressing barriers to the progression of black and minority ethnic social workers to leadership roles. Department for Education. https://practice-supervisors.rip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/StS_KB_Addressing_Barriers_Progression_of_Black_and_Minority_Ethnic_SWs_FINAL.pdf

- Bhatti-Sinclair, K. (2011). Anti-racist social work practice. Palgrave.

- Brady-Williams, D. A. (2018). The black male effect: Challenges and experiences of young black male workers in children and young people’s services. Doctoral dissertation, Middlesex University].Middlesex University Achive. https://www.basw.co.uk/sites/default/files/the_black_male_effect_challenges_experiences_of_young_black_male_social_workers_in_children_and_young_people_services.pdf

- Butt, J. (2006). Are we there yet? Identifying the characteristics of social care organisations that successfully promote diversity. SCIE & The Policy Press.

- Cane, T. (2021). Attempting to disrupt racial division in social work classrooms through small-group activities. Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 18(1–2), 15–138.

- Carpenter, J., Shardlow, S. M., Patsios, D., & Wood, M. (2013). Developing the confidence and competence of newly qualified child and family social workers in England: Outcomes of a national programme. British Journal of Social Work. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct106

- Carpenter, J., Shardlow, S. M., Patsios, D., & Wood, M. (2015). Developing the confidence and competence of newly qualified child and family social workers in England: Outcomes of a national programme. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct106

- Choonara, E. (2021). Theorising anti-racism in health and social care. Critical and Radical Social Work, 9(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1332/204986021X16109919364036

- Department for Education. (2021). Adopted and Looked After Children. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health/social-care/adopted-and-looked-after-children/latest

- Fairtlough, A., Bernard, C., Fletcher, J., & Ahmet, A. (2014). Black social work students’ experiences of practice learning: Understanding differential progression rates. Journal of Social Work, 14(6), 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017313500416

- Graham, M., & Schiele, J. H. (2010). Equality-of-oppressions and anti-discriminatory models in social work: Reflections from the USA and UK. European Journal of Social Work, 13(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691451003690882

- Grant, S., Sheridan, L., & Webb, S. A. (2017). Newly qualified social workers’ readiness for practice in Scotland. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv146

- Hackett, R. A., Ronaldson, A., Bhui, K., Steptoe, A., & Jackson, S. E. (2020). Racial discrimination and health: A prospective study of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1652. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09792-1

- Hollinrake, S., Hunt, G., Dix, H., & Wagner, A (2019). Do we practice (or teach) what we preach? Developing a more inclusive learning environment to better prepare social work students for practice through improving the explorationof their different ethnicities within teaching, learning and assessment opportunities. Social Work Education, 38(5), 582–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1593355

- Jack, G., & Donnellan, H. (2010). Recognising the person within the developing professional: Tracking the early careers of newly qualified child care social workers in three local authorities in England. Social Work Education, 29(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470902984663

- King-Jordan, T., & Gil, K. (2021). Dismantling white privilege and white supremacy in social work education. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 374–395. https://doi.org/10.18060/24088

- Koodum, S., Dudhia, R., Abifarin, B., & Greenhalgh, N. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 307(7954). https://doi.org/10.1211/PJ.2021.1.107434

- Ladhani, S., & Sitter, K. C. (2020). Revival of anti-racism. Critical Social Work, 21(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v21i1.6227

- Lammy, D. (2017). An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, black, asian and minority ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643001/lammy-review-final-report.pdf

- Love, B., Vetere, A., & Davis, P. (2020). Should interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) be used with focus groups? Navigating the bumpy road of “Iterative Loops”, Idiographic Journeys, and “Phenomenological Bridges”. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 199, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1609406920921600

- Lyons, K., & Kathleen Manion, H. (2004). Goodbye DIPSW: Trends in student satisfaction and employment outcomes. Some implications for the new social work award. Social Work Education, 23(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261547042000209161

- Mbarushimana, J., & Robbins, R. (2015). We have to Work Harder”: Testing Assumptions about the Challenges for Black and Minority Ethnic Social Workers in a Multicultural Society. Practice, 27(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1014336

- McLaughlin, K. (2005). From ridicule to institutionalization: Anti-oppression, the state and social work. Critical Social Policy, 25(3), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018305054072

- Memon, A., Taylor, K., Mohebati, L. M., Sundin, J., Cooper, M., Scanlon,T., & de Visser, R. (2016). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: A qualitative study in Southeast England. British Medical Journal Open, 6, e012337. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

- Naseem, M. A. (2011). Conceptual thinking on multiculturalism and diversity in Canada: A survey, R. Ghosh & K. McDonough Eds., Diversity and education for liberation: Realities, possibilities and problems 9–15. Canadian Issues: A Publication of the Association for Canadian Studies. Special Edition.

- Obasi, C. (2021a). Black social workers: Identity, racism, invisibility/hypervisibility at work. Journal of Social Work, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173211008110

- Obasi, C. (2021b). Identity, language and culture: Using Africanist Sista-hood and deaf cultural discourse in research with minority social workers. Qualitative Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120982827

- Obasi, C. (2022). Black social workers: Identity, racism, invisibility/hypervisibility at work. Journal of Social Work, 22(2), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173211008110

- Patrick, B. C. (2020). Navigating the silences: Social worker discourses around race. Dissertation Antioch University. Available: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/560

- Perez, E. (2021). Faculty as a barrier to dismantling racism in social work education. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 500–521. https://doi.org/10.18060/24178

- Pithouse, A., & Scourfield, J. (2002). Ready for practice? The DipSW in wales: Views from the workplace on social work training. Journal of Social Work, 2(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/146801730200200102

- Pollock, M. (2004). Race wrestling: Struggling strategically with race in educational practice and research. American Journal of Education, 111(1), 25–67.

- Pollock, M. (2006). Everyday racism in education. Anthropology News, 47(2), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1525/an.2006.47.2.9

- Ross, S. (2019). Life in the shadow of the snowy white peaks: Race inequalities in the NHS workforce. KingsFund. kingsfund.org.uk

- Sharpe, E., Moriarty, J., Stevens, M., Manthorpe, J., & Hussein, S. (September 2011). Into the Workforce: Report from a Study of Newly Qualified Social Work Graduates. Kings College London, Social Care Workforce Research Unit. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/kpi/scwru/dhinitiative/projects/sharpeetal2011itwfinalreport.pdf

- Singh, G. (2014). Rethinking anti-racist social work in a neoliberal age. In M. Lavalette & L. Penketh (Eds.), Race, racism and social work (pp. 17–32). Policy Press.

- Singh, S. (2019). What do we know the experiences and outcomes of anti-racist social work education? An empirical case study evidencing contested engagement and transformative learning. Social Work Education, 38(5), 631–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1592148

- Tedam, P. (2012). Using culturally relevant case studies to enhance students’ learning: A reflective analysis of the benefits and challenges for social work students and academics. Enhancing the Learner Experience in Higher Education, 4(1), 383–398.

- Tedam, P. (2021). Anti-oppressive social work practice. Learning matters. Exeter.

- Tedam, P., & Cane, T. C. (in press). ‘We started talking about race and racism after George Floyd’: Insights from research into practitioner preparedness for anti-racist social work practice in England. Critical Social Work.

- Tinarwo, M. T. (2017). Discrimination as experienced by overseas social workers employed within the British Welfare State. International Social Work, 60(3), 707–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814562480