ABSTRACT

Oversubscribed social work (SW) courses and a workforce review in Northern Ireland prompted a review of admissions, to ensure recruitment of applicants with strong core values. Concerns regarding authorship, plagiarism and reliability of personal statements, and calls for values-based recruitment underpinned this research. This study evaluates psychometric properties of an SW specific personal statement (PS) and a values-based psychological screening tool, Social Work Match (SWM). Social Work students (n = 112), who commenced the 3-year undergraduate route (UGR) or the 2-year relevant graduate route (RGR) were invited to participate. Their PS scores and SWM scores permitted investigation of scoring outcomes and psychometric properties. Statistical analysis was conducted using Minitab 17. Forty-nine participants (5 male, 44 female) completed SWM on two occasions (October 2020 and January 2021). Findings provide practical, theoretical, statistical, and qualitative reasons for concluding that the PS has substantial limitations as a measure of suitability. It does not compare well with international test standards for psychometric tests. In contrast, SWM is a valid and reliable measure with good discriminatory power, standardized administration and consistent marking. SWM is a viable alternative to the PS for assessing suitability/shortlisting applicants for social work interviews.

Introduction

Social Work (SW) is notorious for poor staff retention (Baginsky, Citation2013; McFadden et al., Citation2019), high staff turnover (Mc Fadden, Citation2018; McFadden et al., Citation2019) and early exit from the profession (Baginsky, Citation2013), which is based on high levels of stress or burnout (McFadden et al., Citation2019), as well as ethical challenges and personal poverty (Pentaraki & Dionysopoulou, Citation2019). Cree et al. (Citation2018) reviewed approaches used for admissions into social work, and found that what constitutes ‘best practice’ remains unclear amidst a range of different approaches. They concluded that whilst there is little evidence that one method of selection to social work programmes is intrinsically better than another, issues of fairness and transparency in selection, as well as diversity, remain a priority.

The goal for SW programmes is to produce graduates who will be competent, ethical and effective practitioners (Ryan et al., Citation2006) as other studies suggest that once admitted, very few SW students have their place on the course terminated (Ryan et al., Citation1997). However, research regarding SW students (Roulston et al., Citation2021) found that students were more likely to be permanently withdrawn from professional training due to ‘poor professional conduct’ linked to SW values. Hayes (Citation2018) conducted a formal review of complaints made about SWs, to the Northern Ireland Social Care Council (NISCC). Findings highlighted concerns about their honesty with allegations of lying or deliberately withholding information; alleged that SWs were biased against the service user/carer or that they discriminated against them based on age, religion, disability, race or nationality; and that SWs failed to demonstrate respect when interacting with service users and carers (Hayes, Citation2018).

Previous research conducted in Northern Ireland, with social work students (Manktelow & Lewis, Citation2005), involved administration of a personality test (NEO‐PI‐R) to applicants of social work training. They found a significant difference between the personality traits of the students who were selected for social work training, when compared to those who were unsuccessful. Successful applicants were more open in terms of feelings, actions and values, less judgmental and more accepting, which are important qualities for social workers, who engage with excluded, stigmatized and discriminated individuals and groups (Manktelow & Lewis, Citation2005). However, they suggested that the significant difference may reflect the beliefs or values of the academic and agency interviewers, which are influenced by when they trained or practised, and the culture within social work agencies. Admissions officer bias toward applicants and the effects of interviewer-interviewee similarity on objectivity in admissions interviews (Frank & Hackman, Citation1975) showed three different outcomes: no relationship or bias towards applicants, low positive bias and strong positive relationship between similarity and interviewer favorableness towards applicants.

Stratton (Citation2000) found that the most commonly used methods for selecting SW applicants were academic records, application form, references, interviews and self-selection. An empirical study conducted in La Trobe University in Australia (Ryan et al., Citation2006) measured eight pre-admission entry criteria against the outcome of the first practice placement for 474 students admitted during 1997–2002. They scored academic record, pre-admission grade point average (GPA), work experience, life experience, academic references, non-academic references, discretionary points (i.e. language, management, research or exceptional interpersonal skills) and relevant subjects (i.e. psychology, sociology or research). Ryan et al. (Citation2006) concluded that their chosen selection methods were unlikely to identify students who would subsequently struggle or fail practice placements. Stratton (Citation2000) suggests this is due to Australian Schools of Social Work adopting admissions approaches with a bias toward ‘social work as a science’ (p. 34), rather than considering ‘social work as an art’ (p. 30) by valuing use of self, knowledge, personal suitability and interpersonal relating, assessed by interviews or personal statements. Ferguson et al. (Citation2000) conducted research involving 176 medical students. They reported that neither the PS information categories nor the amount of information in personal statements were predictive of future performance, whereas, both previous academic performance and conscientiousness were related to success in medical training. Research conducted by Patterson et al. (Citation2016a) found that academic records, MMIs, aptitude tests, SJTs and security checks were more effective selection methods for medical students and were generally fairer than traditional interviews, references and personal statements. Murphy et al. (Citation2009) reported that personal statements have small predictive relationships with grades and faculty performance ratings. In addition, once standardized test scores and prior grades are taken into account, they provide no incremental validity.

Given an increasing emphasis on the values based recruitment of SW students (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014), the current selection process for entry into SW across Northern Ireland (NI) relies on an SW specific personal statement and interview, which offers limited opportunities to evaluate essential personal attributes or values before entry to the programme. Findings from a systematic review into nursing admissions (Crawford et al., Citation2021) suggest that cognitive screening through academic achievement and admissions tests are reliable indicators of academic achievement in health care programmes (Patterson et al., Citation2016a; Schmidt & MacWilliams, Citation2011), whereas there is insufficient evidence regarding interviews and a personal statement (PS). Personal statements are among the most commonly used sources to gather information about applicants in college admissions procedures for undergraduate and graduate programs (Clinedinst, Citation2019; Klieger et al., Citation2017; Woo et al., Citation2020). They are often used to collect information about motivation to study in a particular field and writing skills (Kuncel et al., Citation2020).

Patterson et al. (Citation2016b) reported that personal statements, references and unstructured interviews were inappropriate for values-based recruitment. Niessen and Neumann (Citation2022) reported that the PS used to capture the motivation of 806 psychology students showed low inter-rater reliability and negligible predictive validity for first year GPA and dropout, with authors suggesting that time spent reading and rating the PS was wasted.

The PS has been used in Northern Ireland (NI) since 2003 to assess the suitability of applicants, and shortlist them for interview. The PS is an additional 600-word statement applicants write in response to regionally agreed questions (see below) rather than the PS embedded within the UCAS application. However, concerns were raised by others who debated the reliability of a PS for shortlisting due to possible plagiarism, coaching or bias. They concluded the PS was not fit for purpose and that marking them wastes resources (Cleland et al., Citation2012; Patterson et al., Citation2018).

Concerns have also been raised regarding self-report psychological tests. Self‐report knowledge of a person’s mind-set, worldview and personal values is valuable information, even if the expression of identify is a managed one, or is influenced by social desirability bias, as it can be tested at interview. Milton (Citation2021) round that nursing applicants displayed objective-driven behaviors and circumvented honesty to obtain a university place. They presented a ‘pre-professional’ identity of caring and professional values during interview in line with nursing values frameworks.

The 2018 Ottawa consensus statement ‘Selection and recruitment to the healthcare professions’ (Patterson et al., Citation2018) recommended more evidence-based approaches to selection, which has also been recommended for SW (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014).

Due to concerns raised about the validity and poor inter-marker reliability of the PS, one academic institution in the United Kingdom (UK) explored alternative approaches, which resulted in the development of ‘Nurse Match’ a values-based psychological test for selecting applicants (McNeill et al., Citation2018). When they assessed the UCAS PS and ‘Nurse Match’ (NM) (American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Psychological Assessment and Evaluation Guidelines, Citation2020) against APA standards for psychometric tests, it was evident that NM was more acceptable, due to validity, reliability and test norms, and an automated objective scoring process and consistency in test administration (Traynor et al., Citation2019).

Given selection for entry into SW does not permit a comprehensive evaluation of essential personal attributes (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014), and there is a lack of well-developed measurement and assessment mechanisms to assess student professional suitability (Tam et al., Citation2017), ‘Social Work Match’ (SWM) was developed to measure SW values and promote values-based recruitment (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014), with the potential to replace the PS statement currently used for shortlisting.

Methods

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the PS as a shortlisting measure for SW admission interviews, using empirical evidence about its psychometric characteristics, when compared to the SWM psychometric. The SW specific PS has been an integral part of selection methods for professional training in NI since 2003. It previously focused on motivation and written communication skills. However, was updated in 2018 to align with interview questions. The current version consists of three questions, each weighted at 30%, which invite applicants to outline their motivation to apply for social work degree training, their understanding of the social work role within a chosen area (i.e. children and families, older people, mental health, homelessness or disability services) and the values they bring to social work training. The final 10% is for written communication skills. Questions are updated annually by the regional admissions committee, to prevent plagiarism, and prevent those re-applying submitting the same PS. Applicants submit the PS electronically (Word document) for marking by a social work academic or an agency representative who can award up to 6 points for the first three questions (0 absent, 1–2 for poor to limited, 3–4 for acceptable to good, and 5–6 for very good to excellent) and up to 2 points for written communication skills (i.e. 0 absent, 1 acceptable and 2 very good). The Academic Selector moderates any that fail to meet the threshold (lower than 12/20). This study assesses the validity and reliability of the current PS. The research method used for this project builds on previous research that underpinned the development and testing of NM, a valid and reliable values-based psychometric for shortlisting applicants to nursing (McNeill et al., Citation2018; Traynor et al., Citation2019).

Research setting

Several academic institutions in NI (i.e. Queen’s University, Ulster University, Open University, Belfast Metropolitan College and South West College) currently offer professional SW training through 275 places commissioned by the Department of Health. On average, there are 835 applicants per year. For this pilot study, we recruited a convenience sample of self-selecting participants from one institution, which offers 112 places across two programmes: three year Undergraduate Route (UGR) and two year Relevant Graduate Route (RGR).

Sampling and recruitment

We obtained ethical approval for the project from the School Research Ethics Committee in the participating university (Ref: 006_2021). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions on campus, we relied on ‘Canvas’ announcements to notify students of the research study. The announcement to all students included a research project specific URL where they could read approved study documentation (i.e. invitation letter, Participation Information Sheet, and consent form). A data controller, not involved in teaching or assessing students, obtained written consent from each participant prior to facilitating access to SWM online. Anonymous participant identity was allocated for data management and analysis purposes (e.g. Y1 001). Incentives to participate were offered (i.e. free entry into a draw to win a £50 retail voucher and credit toward a Practice Development Day).

All first year SW students, who had just commenced their professional degree programme, were invited to participate (n = 72 UGR and n = 40 RGR). Recruitment at Time 1 yielded 49 students (5 male; 44 female: 33 UGR1s; 16 RGR2s) who consented to participate and completed data collection (43.75% response rate). Three respondents were excluded due to poor engagement with the test at Time 1. Time 2 yielded 34 students from first year who consented to participate and completed data collection (30.36% response rate). However, 11 respondents were excluded at T2, as they had not participated at T1. Meaning data from 23 students from first year (4 male; 19 female: 15 UGR1s; 8 RGR2s) was available for analysis.

Data collection

At T1, the following information was collected from each consenting participant or with consent, from the appropriate administrative sources:

Demographic information (i.e. age, sex, degree program, postcode).

Preparation for Practice module assignment scores (Tuning-in and Evaluation)

PS scores (marked out of 20).

Interview scores (marked out of 40).

SWM psychometric scores

Feedback on their experience of completing SWM and their perceptions of its suitability for use in selecting SW applicants.

This paper will focus on the PS and SWM scores due to ongoing analysis of other data.

Social work personal statement

The PS has been an integral part of shortlisting methods for SW training in Northern Ireland since 2003. Eligible applicants provide a 600-word written response to assess written communication skills, their motivation to apply for SW training, their understanding of the SW role and the values they bring to training. The PS is marked by an agency or academic social worker, with three questions awarded a maximum of six points each and written communication skills being awarded a maximum of two points.

The SWM psychometric

To develop SWM, key stakeholders engaged in SW admissions across NI attended research steering group meetings. Stakeholders included representatives from the Department of Health who commission SW courses; the Northern Ireland Social Care Council (NISCC) who regulate SW in NI; the NI Degree in Social Work Partnership; admissions staff, academics, and students; social work agencies and representatives from IEL.

Following a comprehensive review of published literature and professional standards, and thematic analysis of transcripts from qualitative interviews with SW students, academics, and practitioners, an iterative process was used to derive a core set of professional values, in consultation with the research steering group.

SWM emerged from the design stage with a set of 19 values preferred by the profession brought together as a value base (VB) and five themes, ‘Professional standards’ (PS), ‘Relationship with service user’ (RSU), ‘Character’ (CH), ‘Resilience’ (RES) and ‘Self-care’ (SC). Each attribute or value was presented as a ‘dimension’ connecting two contrasting points of view (a construct) presented as discourses. Respondents used a nine‐point, semantic differential scale with center zero. A response scored 1 to 4 from weak response to strong response on the point of view it represented. One pole of each construct consisted of a preferred professional attribute or value. Preferred polar values were presented in a randomized manner. Respondents ‘tagged’ the attribute they preferred when they appraised ‘ideal’ or ‘aspirational’ self. Their personal preference may or may not have been a professional preference. Respondents were invited to use the centre point scoring zero (0) if they could not decide between polar values or understand the question.

SWM is ‘custom built’ to assess SW attributes based on the well-established Identity Structure Analysis (ISA) theoryFootnote1and its associated Ipseus software for test construction and scoring (Ellis et al., Citation2015; Weinrech & Saunderson, Citation2003). It measures the extent to which personal values match professional values. Completion is computer-based and normally takes 30–60 minutes (average 45 minutes) to appraise 14 SW related entities using 19 SW values presented as bi-polar constructs, resulting in 266 responses.

Research design

This was a case‐study, self-report, approach to screening for values that required respondents to appraise themselves and other relevant entities using SWM, designed to explore personal use of SW values and attributes. Individual question scores and the total score on the PS were collated for each student who completed SWM. The validity, reliability, fairness, and consistency of the SWM and PS tests were assessed together with psychometric probity for compliance with American Psychological Association’s test standards (American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational, & Psychological Testing (US), Citation1999). For SWM, Ipseus software recorded responses and reported the outcome as scores on theoretical concepts from ISA, three of which were used to calculate a suitability score for each professional value. International psychometric standards for development and delivery of tests, and for quantitative and qualitative data in tandem with descriptive and inferential statistics (using Minitab 17) were used to appraise data outcomes and the quality of findings. The SWM test results on SW values were compared with the PS scores alongside other factors possibly affecting competence (i.e. age, deprivation, gender) and used to assess developmental change in professional identity of students over a 12-week period (October 2019 – January 2020).

In previous research (McNeill et al., Citation2018; Traynor et al., Citation2019), staff supervised groups of students completing Nurse Match in a classroom or computer laboratory. However, due to COVID-19 restrictions, participants sat the SWM psychological test unsupervised at home, at a time most convenient to them. Automatically produced scores were securely stored using the unique identifier, prior to being analyzed by the research team.

Results

The results compare the SW specific PS and the SWM psychological test under three central themes, which emerged from the investigation: (1) quality of data, (2) distribution of scores, and (3) practical usefulness.

Quality of data

The research data were generated by two different measures, SWM and the PS, the former using a scale (SDS) the latter rubric based marking of text, each producing data of distinctly different quality in terms of discriminatory power, reliability, validity and consistency of administration (see ). The findings supporting this characterization of the research data are set out below.

Table 1. SWM and PS measures compared key criteria for good quality psychological scales.

In short, the SWM test meets international standards for psychological tests while the PS has limitations in that regard in line with the findings of McNeill et al. (Citation2018) and Traynor et al. (Citation2019) regarding the similar Nurse Match (NM) test and the nursing PS.

When investigating the quality of data generated by the two measures, three essential standards for psychological tests were applied: (a) validity, (b) reliability and (c) fairness.

Validity

Modern validity theory is considered unitary and evidence based and can be traced back to Cronbach and Meehl (Citation1955) and Messick (Citation1995). Our findings in respect of SWM and the PS include the classic concept of validity and are set out below. We used a set of research relevant criteria from the validity literature (see ).

Table 2. Summary of evidence about validity of scores on the PS measure of suitability.

Table 3. Summary of evidence about validity of scores on the SWM measure of suitability.

SWM uses a self-report case‐study approach that shares characteristics with three overlapping methods, controlled observation, interview and psychometric test to gather and data on respondent’s use of 19 validFootnote2 SW constructs to appraise self and SW relevant others and score the responses against professional use, their personal importance and their emotional significance.

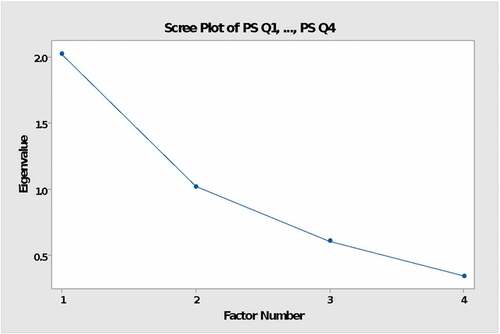

Factor analysis of the SWM scores by Level 1 students (n = 46) on the six test scales established the presence of a single underlying factor (Factor 1), accounting for 88.9% of the variance between scales see . This factor appears to be the concept ‘Suitability for SW’ and argues for the validity of the test as a whole. Factor 2 has an eigen value of <1 and deals with 0.042% of the variance and is set aside (Kaiser criteria recommending use of factors with an eigen value of at least 1). [An eigen value is a number telling you how much variance there is in the data in a given factor. The factor (eigenvector) with the highest eigen value is therefore the principle component; it accounts for the most variance. A good factor analysis should explain two thirds of the variance. There are several methods for selecting the number of factors one of which is called the Kaiser Rule. But they are all heuristics, a best guess in conditions of uncertainty, which can make sense and enable one to select the number of components that seem valid. Factor loadings can be rotated to give a solution with the best simple structure but that refinement was not used. Communality is the proportion of each variable’s variance that can be explained by the factors].

Table 4. Level 1 T1: Unrotated factor loadings and communalities.

The overall purpose of the PS has not been defined but as we know it assesses four relevant characteristics and the sum of the scores on these is used to shortlist applicants for interview. Where construct validity is concerned one must ask ‘What construct is actually being assessed?’ and ‘How well has that been done?’ Consideration of test administration, the marking criteria and marking process, revealed grounds for concern about validity in both classic and unitary terms (see Table S1 in the Supplementary material).

The four criteria appear individually to be appropriate as measures of suitability for SW even though broadly defined, un-researched and with no scientific basis in theory. Concern about the validity of the PS is related to credibility and fitness for purpose, given the issues around the robustness and reliability of subjective marking, poor inter-marker reliability, and lack of transparency around integrity of author input, with the possibility of assistance from relatives, advisers, or SWs. The substantial difference that can occur between HEI markers of the same PS was demonstrated in secondary evidence from nursing (McNeill et al., Citation2018).

Factor analysis (), established the presence of two latent variables (factors) indicating that the PS was not one-dimensional (Kaiser criteria: eigen factors >1 should count: see ). The PS criteria clustered in two factors that accounted for most of the variance (76.1%). It makes sense to think of one factor (F1) as consisting of SW attributes (motivation, understanding values and to some extent writing skills) and the other factor (F2) of writing skills and to small extent values. If true, this would tend to undermine the validity of the test as a measure of ‘suitability for SW’ since writing skill is a substantial element and authorship of the PS is not controlled.

Table 5. Level 1 T1: PS unrotated factor loadings and communalities.

We concluded that scores on values using SWM were valid because credible, fit for purpose, robust, reliable, had integrity, were representative, coherent, and transparent. We found the PS to be representative of social work values and coherent however validity was constrained by concerns about reliability, credibility, transparency, integrity and fitness for purpose mainly associated with the marking process and lack of control of authorship.

Reliability

One can assess the degree to which a psychometric measure is reliable in several ways. The most relevant being test–retest reliability, internal consistency (item or scale reliability) and interrater reliability.

SWM test-retest reliability

The essential notion here is consistency, the extent to which the test or measure yields the same approximate results when utilized repeatedly under similar conditions. This will hold for personal values so long as nothing significant has changed in context, personal experience, mood, or mind-set of the test respondent. It is assumed that ‘people don’t change’ but change and adjustment, to maintain a certain sense of self, is part of everyday human experience. SWM provides a snapshot of a student’s mind-set (on SW values) at the time of response, using the same measure and process each time.

When the analysis is performed on a group of individuals, an overarching picture of group identity in terms of social work values emerges. We assumed that if we repeated the testing process, with the same group of test takers, in similar circumstances, little would have changed, individual variations would tend to cancel out and closely similar group results would be obtained. If the whole group had had an impactful common experience such as their first semester during which everyone’s beliefs are somewhat affected, the mean score for the group would reflect the net effect of different individual responses to the experience.

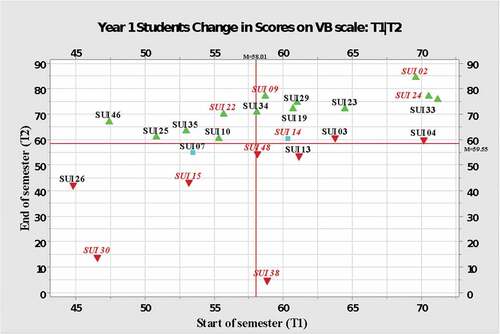

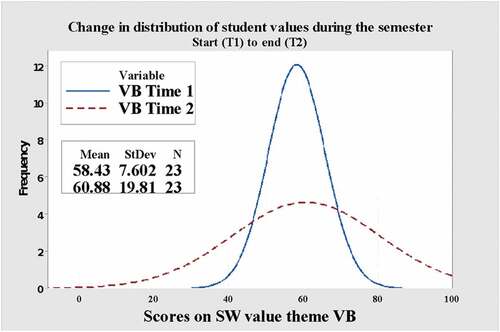

We found that at T2 there were noteworthy differences in scores on the test when compared with T1, the majority of students (13; 56.5%) improving their score probably reflecting the learning that had taken place. The scores of two students (8.7%) showed little change. There was also greater variance in scores at T2 (SD: T1, 7.59: T2, 19.1) probably reflecting differential uptake during the learning experience.

In , we see a wide range of percentage changes in scores by individuals (+41.3% to −91.92%) between (T1) commencing and (T2) finishing semester one. Yet, there is no significant difference overall in the mean score at T1 and T2 (diff = −1.09: t(23) = −0.24 p-value = 0.809). Why? Overall there was an improvement in scores on values taught during semester one (, green triangles) a positive effect due to the common educational experience. However, two very low outliers at T2 (SUI 30, SUI38) distorted the mean and offset the general gain in scores due to the educational effect.

Table 6. Students ranked by % change in VB scores on SWM test: T1 to T2.

This evidence supports the contention that SWM psychometric is a reliable measure and a useful one rather than providing proof of it. Findings indicate that the scores on values presented a picture of student development grounded in the reality of SW education as experienced by tutors. The group scores at T2 did reflect the benefit of education for a semester, that is there was a positive change in scores on values, but they also highlighted that for a minority (8:34.8%) the change was negative and for two of those the change was a very large negative one resulting in no significant difference between group mean scores at T1 and T2.

PS test-retest reliability

Given the earlier description of the PS, and the evidence about content, how it is produced, administered, and marked leading to concerns about validity, it is difficult to feel confident that if a given test was repeated the second outcome would reliably reflect real change since the first—although there is no empirical evidence to support a presumption that test–retest reliability is limited because the PS test was not repeated, this seems a reasonable inference.

SWM internal consistency (item or scale reliability)

We investigated internal reliability of the SWM test using a Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha and found a strong correlation between scores on item scales and an excellent level of internal consistency.

First Year (T1) values based (VB) scores correlated strongly and positively with ‘Professional Standards’ scores (PS), r (44) = .90, p = 0.000 (two-tailed). As indicated in , the correlation between all six theme scores were similarly strong and positive. The SWM item scales have a high level of internal consistency as determined by Cronbach’s coefficient of reliability; α = 0.9740.

Table 7. First Year T1: Pearson (r) matrices: scores on themes and value base (VB).

PS internal consistency (item or scale reliability)

We estimated reliability of the personal statement using Cronbach’s Alpha and found level of internal consistency, to be questionable (α = 0.668). However, even this conclusion must be treated with caution given the small number of items and the nature of the item measures—they are not dichotomous or Likert like scales. Consequently, one could not conclude using Alpha whether or not the PS was internally reliable mainly because the assumptions for use of Alpha were not fully met.

We also investigated internal reliability of the PS items using Spearman’s rho for non-parametric data () and found strong or very strong statistically significant correlation between the overall PS score and the three item scales. This was not the case with writing skills for which all students save one scored the maximum two (r s = 0.28), a weak correlation.

Table 8. First year T1: spearman’s rho matrices: correlation coefficient of scores on PS criteria themes and overall PS score.

The strength of association between three criteria scores (Q1, Q2, Q3) was moderate (rs 0.42–0.55) positive and statistically significant (p = 0.00 α = 0.05 for all three). Writing Skill (Q4) had weak positive association with the overall score (rs = 0.28) and with SW values (rs = 0.31) and a very weak positive correlation with Motivation (rs = 0.02) and Understanding of SW (rs = 0.07). None of these correlations were statistically significant (respectively p = 0.19, 0.94, 0.74 and 0.15: α = 0.05).

Internal consistency is lessened because of weak or very weak correlation between the scores on writing skills and scores on the other criteria, due to skills being marked out of two, and with all but one participant scoring two.

SWM inter-rater reliability

With SWM there is no inter-rater issue since the software uses the same algorithms and equations to calculate a suitability score for each respondent.

PS inter-rater reliability

The PS scoring presents a rubric for assessing the four criteria described above. The rubric offers guidance: “The marker will score the script with a zero if the candidate ‘Offers no reasons for choosing social work’; a one if ‘Reasons for choosing social work lack clarity’, … and so on until … and a six if ‘A clearly articulated desire to commence a career in SW based on clear goals, experience and knowledge of the SW role’.

This procedure involves an experienced tutor, and subjective interpretation and application of the rubric to the content of the statement to generate a score. This makes inter-rater reliability difficult to achieve. There is secondary evidence of a low positive correlation coefficient between scores on the same statements marked by two different HEIs (r = 0.27) statistically significant p = 0.002 (α = 0.05) (McNeill et al., Citation2018).

Reliability of PS and SWM

We can reasonably infer that the six SWM test scales designed to measure the construct ‘suitability for social work’ do so with a high degree of test-retest, internal and inter-rater reliability and consistently reflect the reality of social work values held by students. The PS was not intended to be reused and reliable, and both internal reliability and inter-rater reliability have issues the latter being the more serious.

Fairness

With SWM, in accordance with international standards, all participants receive comparable and equitable treatment during each phase of the testing or assessment process. Each participant receives standardized instructions controlling collaboration with others and has the same user interface. Also marking is automated and not subjective.

With the PS test all participants are processed in the same manner but the process is inherently unfair since assistance with authorship is constrained only by the resources and integrity of the applicant and marking is subjective and uneven in quality increasing the risk of unfairness.

If adopted, the SWM test will be one element in a multi-faceted assessment process that aims to provide a holistic picture of an applicant. The issue is to create a fair and effective system of methods and procedures for data collection in which the limitations of each approach are known and accounted for and the net effect is as fair and effective as possible.

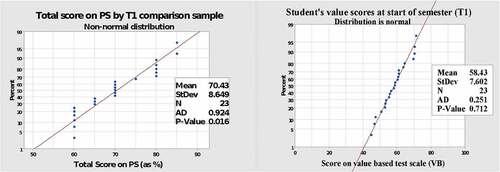

Distribution of scores

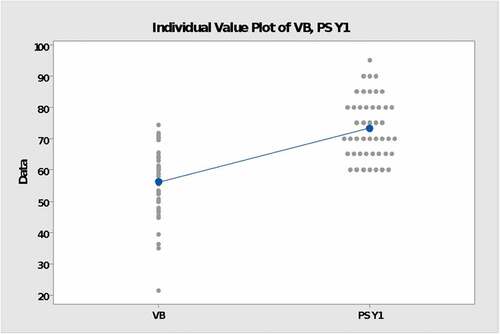

The scores awarded on the basis of the rubrics used in the PS process are ordinal numbers. The score is then the ‘category’ the applicant falls into when a rubric is applied to assess their response. The overall score on the PS is the sum of the scores on the four criteria. These scores rank order applicants in a cohort but tell us nothing about distances between ranking positions. This is a source of uncertainty since many students can inhabit the same ordinal rank and one must find another method of choosing between them or chose them all. The PS is also much easier to score well on (see : SWM -VB theme – compared with PS overall measure).

illustrates the importance of the normal distribution to the understanding of progress toward a professional SW identity. It is the most important probability distribution in statistics because it fits many natural phenomena. The learning process and the growth of a personal sense of self as an SW and of a group identity through experience of life as an SW are natural processes. A suitable candidate will have the basic values to some degree (see the T1 distribution of scores). After one semester, the distribution of scores on SWM by first year students remains a normal distribution with a similar mean but much greater variance since the learning process proceeds at a different rate for different students.

Practical usefulness

On considering the practical usefulness of these measures in the light of the above considerations, we found the following.

Distinguishability and fitness for purpose

Some individuals in a cohort will thrive and some will struggle, but the natural variation in the rate of development and understanding of SW values, as measured by the SWM psychometric, is likely to take the form of a normal distribution (). Where outliers are concerned, it is reasonable to infer that the natural process of development may not be working for them, as it should. The PS uses ordinal scoring and has a non-normal distribution producing many ties and this undermines distinguishability of candidates and understanding of developmental progress ().

The PS streamlines the number of applicants invited to interview, but does not meet international test standards and is difficult to justify as a measure. SWM offers a standardized, effective, user friendly, screening test for values that meets international standards.

SWM is externally administered online, with results returned to admissions. Therefore, SWM makes fewer demands on staff resourcing when compared to agency or academic staff marking hundreds of PS.

Completing the SWM test takes from 30 to 45 minutes, which was sufficient time for most applicants (91.1%). Preparing a 600-word PS, in response to set questions, would undoubtedly take applicants longer.

On completion of the SWM test, the following experiences were captured:

Mostly easy (94.5) and interesting (92.2%) to complete.

Mostly easy to understand (95.5%) and respond to intuitively (86.7%).

Hard to know how to respond (66.7%) vs. not hard to respond to (31.1%).

Not too challenging to complete (72.2%) vs. too challenging here and there (25.6%).

Offered enough time to complete it properly (91.1%).

Identified the most important Social Work values (78.9%).

Contained no irrelevant issues (88.9%).

Easier (31.1%) and different (34.4%) from other selection processes.

Participants described SWM as ‘an intuitive addition to the selection process’, or ‘a good way of getting an overview of somebody’s values’, and ‘easy in comparison to interview’. One participant found it ‘thought provoking and challenging’. In contrast, some participants found it ‘hard to stay focused’ as the ‘test was repetitive’, one found some questions hard to what each question meant, particularly in relation to ‘friend’ or working out someone’s perceptions of a situation. Some questioned the accuracy of some polar opposites, which were reviewed by the research steering group.

Discussion and conclusion

The International Federation of Social Workers (International Federation of Social Workers, Citation2014), in its global definition of social work, notes that ‘principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central’ to the profession. As such, it is imperative that students recruited to social work training programmes should have personal attributes and values congruent with those required for social work practice, reflecting the important gate-keeping role of admissions to qualifying training to ensure that competent, ethical, and effective practitioners enter the profession (Ryan et al., Citation1997). Narey (Citation2014, p. 14) notes that concerns about the ‘caliber of students studying for social work degrees has been an issue of debate since the social work degree was introduced in 2003’. Narey’s review, commissioned by the Department for Education, focused on the training of children’s social workers with the concerns about ‘calibre’ identified being more in relation to academic standards rather than values and attitudes. Previous research (Cree et al., Citation2018) failed to determine one ‘best’ approach to selecting applicants to study social work. Ferguson et al. (Citation2000) concluded that interviews or personality tests did not help to predict those who would successfully enter the profession, whereas Manktelow and Lewis (Citation2005) concluded that the effectiveness of interviewing as a selection method performed satisfactorily, when tested against an objective and independent measure.

In a broader review of social work education, commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care, Croisdale-Appleby (Citation2014, p. 34) concluded that University selection processes needed to be improved to ensure the consistent selection of candidates, not only with the academic qualities needed for a successful career in social work, but also with the ‘personal’ qualities required. Although Croisdale-Appleby noted that most Universities assessed values in some form, he argued that prior experience is often used as a proxy for this and that this was not always justified. As an alternative, he recommended that ‘ … consideration be given to utilizing values-based selection procedures and proven and validated selection tools … as a major part of the selection methodology’ (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014, p. 40).

Tam et al. (Citation2017), however, have noted a lack of well-developed measurement and assessment mechanisms to assess the suitability of applicants for professional social work training and their essential personal attributes and values. This study has reported on the development and evaluation of a values-based psychological screening tool (Social Work Match) and compared this to the use of a personal statement in terms of assessing suitability for social work training and shortlisting applicants for interview. The study has some limitations in that scoring on values is not generalizable to the wider population of applicants to schools of social work and there is no comparison between successful and unsuccessful applicants. Firstly, the test, while it can be regarded as a universal measure of values, should be customized for each school, since each school has its local perspective on the values, findings are based on a small number of participants (n = 49) restricted to one University and, participants were students who had already secured a place on a social work training course. Further research, therefore, is required across different academic institutions, with a larger sample across different contexts and geographical boundaries, and with applicants participating in the selection process for social work training rather than students who have already secured a place.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the Social Work Match tool, when compared to the social work specific personal statement as a method for assessing suitability and selecting applicants for interview, was more effective as a measure in terms of utility, validity, reliability, and the objectivity and resource intensiveness of the administration and assessment processes. SWM assesses the relative ‘importance’ and emotional significance given to each value dimension (bi-polar construct) in making sense-of-self in the world during test completion. Asking people directly about themselves, and what they think of others, can offer revealing or rich data, particularly when asked to respond intuitively and quickly. Consequently, valid, and reliable self‐reports rely on sound motivation, openness, honesty, and astute self‐awareness. These findings echo those of McNeill et al. (Citation2018) and Traynor et al. (Citation2019), who compared the UCAS personal statement for nurse applicants to a value-based psychological screening tool (Nurse Match) noting its stronger validity, reliability, and objectivity. It can be concluded that Social Work Match offers a viable, practical and robust alternative to the personal statement as a method for assessing the suitability of applicants for social work training and shortlisting for admissions interviews.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the university research and administrative staff, who supported this research project; Allen Erskine from Identity Exploration Limited; members of the Research Steering Committee, and Social Work students who participated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A conceptual framework explicating self-identity consisting of, in the main, life span development and identity theory (Erikson E), social id entity theory (Tajfel, H), personal construct theory (Kelly, G A), and cognitive affective consistency theory (Festinger, L) in recent years informed and supported by empirical evidence and development of theory in the neurosciences about the fundamental role of feeling in subjective experience and homeostatic processing of such information by the brain, active inference and predictive perception (Solms L, Friston K, Seth A.).

2. Had construct validity: based on a literature search, content analysis, codification, frequency of use count, trialing by SWs, advice and guidance from experienced SWs and a steering committee, re‐affirmed by feedback on its use from student social workers.

References

- American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational, & Psychological Testing (US). (1999) . Standards for educational and psychological testing. Amer Educational Research Assn.

- American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Psychological Assessment and Evaluation Guidelines. (2020). APA Guidelines for Psychological Assessment and Evaluation. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/guidelines-psychological-assessment-evaluation.pdf

- Baginsky, M. (2013). Retaining experienced social workers in children’s services: The challenge facing local authorities in England. NIHR Health & Social Care Workforce Research Unit, The Policy Institute.

- Cleland, J. A., Dowell, J., McLachlan, J., Nicholson, S., & Patterson, F. (2012). Identifying best practice in the selection of medical students: Literature review and interview survey. General medical council. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/gmc-site-images/about/identifyingbestpracticeintheselectionofmedicalstudentspdf51119804.pdf?la=en&hash=D06B62AD514BE4C3454DEECA28A7B70FDA828715

- Clinedinst, M. (2019). State of college admissions. The National Association for College Admission Counselling. https://www.nacacnet.org/globalassets/documents/publications/research/2018_soca/soca2019_all.pdf

- Crawford, C., Black, P., Melby, V., & Fitzpatrick, B. (2021). An exploration of the predictive validity of selection criteria on progress outcomes for pre-registration nursing programmes—A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(17–18), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15730

- Cree, V., Morrison, F., Clapton, G., Levy, S., & Ingram, R. (2018). Selecting social work students: Lessons from research in Scotland. Social Work Education, 37(4), 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1423050

- Croisdale-Appleby, D. (2014). Re-visioning social work education: An independent review. https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_22718-9_0.pdf.

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

- Ellis, R., Griffiths, L., & Hogard, E. (2015). Constructing the nurse match instrument to measure professional identity and values in nursing. Journal of Nursing and Care, 4, 245. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1168.1000245

- Ferguson, E., Sanders, A., O’Hehir, F., & James, D. (2000). Predictive validity of personal statements and the role of the five-factor model of personality in relation to medical training. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 73(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167056

- Frank, L. L., & Hackman, J. R. (1975). Effects of interviewer-interviewee similarity on interviewer objectivity in college admissions interviews. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 356–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076610

- Hayes, D. (2018). Relationships matter: An analysis of complaints about social workers to the Northern Ireland social care council and the patient and client council. Northern Ireland Social Care Council. https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/relationships-matter-analysis-complaints-about-social-workers-northern-ireland-social-care

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2014). Global definition of socialwork. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Klieger, D. M., Belur, V., & Kotloff, L. J. (2017). Perceptions and uses of GRE® scores after the launch of the GRE® revised General Test in August 2011. ETS Research Report Series (pp. 1–49). https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12130

- Kuncel, N., Tran, K., & Zhang, S. (2020). Measuring Student Character: Modernizing Predictors of Academic Success. In M. Oliveri & C. Wendler (Eds.), Higher Education Admissions Practices: An International Perspective (Educational and Psychological Testing in a Global Context (pp. 276–302). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108559607.016

- Manktelow, R., & Lewis, C. (2005). ‘A study of the personality attributes of applicants for postgraduate social work training to a Northern Ireland university’. Social Work Education, 24(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470500050503

- McFadden, P. (2018). Two sides of one coin? Relationships Build resilience or contribute to burnout in child protection social work: Shared perspectives from leavers and stayers in Northern Ireland. International Social Work, 63(2), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818788393

- McFadden, P., Mallet, J., Campbell, A., & Taylor, B. (2019). Explaining self-reported resilience in child protection social work: The role of organisational factors, demographic information and job characteristics. British Journal of Social Work, 49(1), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy015

- McNeill, C., Traynor, M., Erskine, A., & Ellis, R. (2018). Developing nurse match: A selection tool for evoking and scoring an applicant’s nursing values and attributes. Nursing Open Wiley, 6(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.183

- Messick, S. (1995). The once and future issues of validity: Assessing the meaning and consequences of measurement. In Test validity. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2330-8516.1986.tb00185.x

- Milton, S. (2021). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the student nurses’ perceptions on value-based recruitment in the context of their personal constructs of caring and professional values [ Doctoral Thesis], Cardiff University (EThOS ID uk.bl.ethos.852634).

- Murphy, S. C., Klieger, D. M., Borneman, M. J., & Kuncel, N. R. (2009). The predictive power of personal statements in admissions: A meta-analysis and cautionary tale. College and University, 84, 83–86.

- Narey, M. (2014). Making the education of social workers consistently effective: Report of sir Martin Narey’s independent review of the education of children’s social workers, Department for Education.

- Niessen, A. S. M., & Neumann, M. (2022). Using personal statements in college admissions: An investigation of gender bias and the effects of increased structure. International Journal of Testing, 22(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2021.2019749

- Patterson, F., Knight, A., Dowell, J., Nicholson, S., Cousans, F., & Cleland, J. (2016a). How effective are selection methods in medical education? A systematic review. Medical Education, 50(1), 36–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12817

- Patterson, F., Prescott-Clements, L., Zibarras, L., Edwards, H., Kerrin, M., & Cousans, F. (2016b). Recruiting for values in healthcare: A preliminary review of the evidence. Advanced Health Science Education, 21(4), 859–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9579-4

- Patterson, F., Roberts, C., Hanson, M. D., Hampe, W. E., Ponnamperuma, K., Magzoub, G., Cleland, A., & Tekian, J. (2018). Ottawa consensus statement: Selection and recruitment to the healthcare professions. Medical Teacher, 40(11), 1091–1101. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1498589

- Pentaraki, M., & Dionysopoulou, K. (2019). Social workers: A new precariat? Precarity conditions of mental health social workers working in the non-profit sector of Greece. European Journal of Social Work, 22(2), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1529664

- Roulston, A., Cleak, H., Hayes, D., McFadden, P., O'Connor, E., & Shore, E. (2021). To fail or not to fail: Enhancing our understanding of why social work students failed practice placements (2015-2019). Social Work Education: The International Journal, Early Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/025615479.2021.1973991

- Ryan, M., Cleak, H., & McCormack, J. (2006). Student performance in field education placements: The findings of a 6-year Australian study of admissions data. Journal of Social Work Education, 42(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2006.200303106

- Ryan, M., Habibis, D., & Craft, C. (1997). Guarding the gates of the profession: Findings of a survey of gatekeeping mechanisms in Australian bachelor of social work programs. Australian Social Work, 50(3), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124079708414092

- Schmidt, B., & MacWilliams, B. (2011). Admission criteria for undergraduate nursing programs: A systematic review. Nurse educator, 36(4), 171–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0b013e31821fdb9d

- Stratton, K. (2000). Before and after science: Admissions process to Australian university social work courses. Australian Social Work, 53(3), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070008414313

- Tam, D. M. Y., Kwok, S. M., Streeter, C., Rensink Dexter, J., & Schindler, J. (2017). research report on examining gatekeeping and assessment of professional suitability in Canadian social work education, University of Calgary.

- Traynor, M., Barr, O., McNeill, C., Erskine, A., & Ellis, R. (2019). Burdett trust for nursing final report ‘what matters to patients’: Identifying applicants to nursing who have the personal values required to build a skilled and competent workforce and lead the nursing profession in Northern Ireland. Executive Summary A. Belfast. https://www.qub.ac.uk/schools/SchoolofNursingandMidwifery/FileStore/Filetoupload,945100,en.pdf

- Weinrech, B., & Saunderson, W. (2003). Analysing identity: Cross cultural, societal and clinical contexts. Routeledge.

- Woo, S. E., LeBreton, J., Keith, M., & Tay, L. (2020). Bias, fairness, and validity in graduate admissions: A psychometric perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/w5d7r