ABSTRACT

The push to improve Indigenous student retention and completion rates in higher education programs is a strategic goal across Australian universities. Similarly, the notion of decolonizing education to allow for a more culturally relevant educational experience is being discussed in university curricula development. In this article, we highlight challenges within the current neoliberal political context influencing a decolonized approached to higher education. We will draw on experiences from a case study of a creative therapy course situated within a Social Work program at a regional university. A team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers will propose a framework for navigating pedagogical and administrative challenges to design a course that serves as a powerful tool to advocate for changes in higher education and social work systems. We suggest that this framework can be used to build valuable connections across Indigenous and Western knowledge systems and promote truth-telling in the social work context. Finally, we argue that our framework for decolonising education is inter-disciplinary and a useful tool in helping staff and students take back their knowledge from colonial power structures.

IMPLICATIONS

In order to decolonise social work education, we need to deconstruct the whiteness embedded in pedagogy, theory and social work practice itself.

We need to work in true partnership with Indigenous knowledge holders and community members to co-create new knowledge.

This framework can be used to build valuable authentic connections across Indigenous and Western knowledge systems and promote truth-telling in the social work context. This framework works to both challenge current social work curricula in Australia and attract and retain Indigenous students in social work education, which arguably would help to ensure culturally relevant practice with and by Indigenous people.

The rabbit proof fence and higher education

The Rabbit Proof Fence is a story from the 1930s about three Aboriginal girls who escape from the native settlement in Western Australia to return to country and to their community. The narrative speaks to Australia’s colonial historical legacy of the stolen generation and intergenerational trauma, but it also highlights spirituality, relationship, connection to country and family along with courage and determination to pursue the importance of culture at all costs. It is these aspects that need to be considered if we are to truly decolonize social work education in Australian higher education. This process demands courage in truth-telling and passes a critically reflective eye on the assumptions that underlie the theories, practices, and systems that continue to be espoused and recreated in current higher education courses. More importantly we need to be fearless in recognizing social work’s complicity in the stolen generation as we challenge the influence of Eurocentrism in social work education which, by its very nature, is currently a colonized space.

The Rabbit Proof Fence is also symbolic of the socioeconomic divide between non-Indigenous and Indigenous lived experience in Australia, where the social determinants of health are in an embedded pattern of disadvantage for Indigenous people (Walter et al., Citation2011). This has translated into Indigenous Australians living in different spaces, which continues to allow for Indigenous people to be treated as a unified category. The inclusion of emancipatory theories into social work such as feminism and antiracist theory, for example, has done little to change the hierarchical power structure within social work itself, which espouses a top-down model of the professional expert who crosses the fence, only to deliver a service as defined by the western experts (Walter et al., Citation2011). The binary positioning of the black/white divide is a social construct that works to exert power. Walter et al. (Citation2011) contend that the social work gaze must shift from the ‘other’ placed on the other side of the fence to the ‘whiteness’ on their own side of the fence. That is, rather than seeing the Indigenous cultural perspectives as a deficit to the colonial ‘white’ perspective, we must flip the narrative to consider that perhaps the ‘white perspective’, particularly in the context of social work education, is deficit to the needs of Indigenous peoples. To do this, we must invert the traditional top-down power structures and understand what it is that Indigenous peoples need to feel empowered and therefore enable reconciliation and healing, from their perspective.

According to Reconciliation Australia (Citation2016), truth-telling is linked to social justice, reconciliation, and healing. Truth-telling requires ‘political will, joint leadership, trust building, accountability, transparency, and investment of resources’ (Citation2016, p. 15). Truth-telling plays a pivotal role in decolonizing higher education practices and in empowering the Indigenous voice. Truth-telling, is about privileging other voices, allowing another’s truth to be told. Truth-telling allows for new narratives to emerge beyond the veil of the dominant colonial voice. If we consider this in the current context of higher education pedagogical practices, the dominant voice is undoubtedly that of neoliberalism, across the social work curriculum. Courses are administered by the notion that current government policy based on historical colonial practices is best practice for all (Wallace & Pease, Citation2011). This view restricts Indigenous people from sharing their truth and forces compliance into a western perspective on social work education and practice in Australia, in order to become a registered practitioner. This article explores the current state of play in Australian social work tertiary education and provides a framework for moving toward a more decolonized approach to social work education in Australia. It will draw on practice experience from creating a higher education course that aims to both decolonize and create new knowledge in partnership with Aboriginal people. It will propose a framework for how this can be achieved within the current confines of neoliberal education practices and course requirements.

The authors have worked in education, child protection, and as creative therapists, in both remote and urban settings in several states in Australia, which have afforded insights that are not only relevant to social work education but are transferable across disciplines. The model of education proposed in this article is a culmination of many years of research and practice across education, social work, and creative therapies.

Social work practice in Northern Australia

Northern Australia has the largest population of remotely based Aboriginal people in the nation. There is the historical legacy of social work practice enacting racist legislation in the removal and displacement of Aboriginal children and families. This legacy lives on, in that no matter the numerous changes in title and configuration of child protection agencies, many Indigenous people still refer to these agencies as ‘welfare’, which is synonymous with child removal. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are still 12.2% more likely to be taken into care (Liddle et al., Citation2021). To Bennett and Green (Citation2019) there is suspicion and distrust of social workers for many Aboriginal communities, families, and individuals. Many social workers are sent into communities to look introspectively into what is happening to families and how families should be monitored or changed to comply with government policy. These policies remain laced with historically ‘white’ perception on what is and is not ok for families. There are few Indigenous social workers in Northern Australia, and those working are required to uphold the government policies of the organization which employs them. This requires Indigenous social workers to ignore their own cultural truths and knowledge to uphold the government required standards. Social work education and practice is therefore governed by the same colonially grounded legislation that has been and remains inherently problematic for Indigenous peoples. It fails to educate social workers on understanding Indigenous knowledges and privileges, ‘white’ family structures, and cultural practices.

During research conducted in 2012, on how Indigenous children in care negotiate identity, it became clear that Indigenous and non-Indigenous child protection workers view identity and identity issues from opposing paradigms (Moss, Citation2012). Not only did the Indigenous workers identify that the stolen generation continues with the removal of large numbers of their childrenFootnote1 but that the theoretical basis that social workers who were interviewed identified as drawing upon, such as ‘Erikson identity theory’ and ‘attachment theory’, do not sit well with many Indigenous people. For example, two of the Indigenous workers who were shown Erikson’s theory of identity during the research commented, ‘That boy’s confused’ and ‘Someone should probe him and tell him a different story’ (Moss, Citation2012 p. 253). Similarly, extended kinships systems intrinsic to Indigenous culture can be problematic for attachment theory in practice (Moss, Citation2012). This highlights the inherent disconnect between western theories and practices and the impact of this on Indigenous workers as they try to negotiate working in a space that denies their lived reality.

Two authors having managed a therapeutic service in the Northern Territory, which was funded to evidence base a model of therapeutic practice for remotely based Aboriginal children who had suffered abuse, it became clear that the very foundation of what we are taught in terms of the underlying assumptions of western counseling practice needed critical analysis and deconstruction to work in this new context (Moss & Lee, Citation2019). This included unpacking our basic assumptions like time, place, boundaries, diagnoses and concepts of healing. These findings have direct implications for social work education and practice. There have been previous calls for decolonizing social work by democratizing social work education, being inclusive and reflecting on shared power (McNabb, Citation2017). We propose that education cannot be truly democratized without deconstructing the underlying assumptions and power base of the theories we use, that then inform practice. What this speaks to is the inherent theoretical imperialism embedded in western theories and education.

Social work practice in higher education

It has been a long-standing aim of higher education in Australia to increase Indigenous student numbers. This is particularly pertinent in social work where Indigenous people are over-represented in social services. For example, in Australia, Indigenous children come into out-of-home care at eleven times the rate of non-Indigenous children, and children who live remote are three times more likely to receive a substantiation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021). According to 2017 census data (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Citation2017), only 2.5% of social workers in Australia identify as Indigenous, with the majority of social workers being predominantly from white Anglo-Australian origin. In the context of regional areas, as a consequence of staff shortages and turnover, especially in child protection, many social workers are bought in from overseas. Papadopoulos (Citation2017) looked at the countries where overseas social work migrants to Australia attained their education. She found that 63% of all applicants come from one of the six countries, the UK, Ireland, South Africa, NZ, USA, and India. The assessment process for these applicants undertaken by the AASW it is argued conforms to a certain type of acultural social work that compares educational programs and fails to recognize the applicant’s actual skills (Papadopoulos, Citation2017). Dittfeld (Citation2020) identified colonialism as underpinning social work practices and went on to explain that by only focusing on traumatic histories for the sake of efficiency presents Indigenous people as the problem to be solved, while negating social work as a direct product of a colonialism that continues to play itself out. Tamburro (Citation2013) correctly identifies that currently the decolonization of social work practice and pedagogy is positioned as an attainment of knowledge, skills, and values that will support their work with Indigenous people but not to empower Indigenous people or privilege their knowledge. It is an add-on, rather than an interrogation of current teaching practice and content. Wallace and Pease (Citation2011) highlight how social work in Australia has become part of the neoliberal agenda with broad ranging consequences such as managerialism and marketization infiltrating all areas of social work practice including in education. To Walter and Baltra-Ulloa (Citation2019a) there needs to be a refocus of the racial lens from Indigeneity to ‘whiteness’ and that social work is caught in the ‘permanent cycle of speaking relentlessly about culture/race of the other while remaining largely mute on its own’ (p.66). They contend that social work in Australia has retained a cloak of cultural sensitivity by ‘allowing’ Indigenous knowledge and people a place while still retaining its ‘power and privilege’ by controlling how much space is given and where and when it is allocated within the profession (p. 71). To O’Keeffe and Assoulin (Citation2021, p. 114) social work education has become depoliticized, which it is argued has resulted in ‘producing depoliticized social work graduates’ who are skilled in non-critically adapting to the market values of neoliberalism.

For all universities, but particularly those located in regional areas, the need to retain students is a high priority. This is particularly important for the ongoing financial and economic sustainability of smaller institutions in the wake of the 2017 funding model changes (Parliament of Australia, Citation2017), along with the impact of government policy and funding post-COVID-19 outbreak. The underlying neoliberal ideology of these changes work to decrease overall funding while increasing student fees substantially for those students in the humanities (which one could argue is the home of critical thinking), while decreasing fees for what the government considers to be ‘job ready’ courses. To Watts (Citation2021), managerialists, which has seen a huge increase in numbers across all universities in Australia, have seen the rise of strategic plans, academic audits, performance reviews, and the like, which has coincided with the continuous worsening of the staff/student ratio. Meanwhile, courses and programs are only deemed a success when the metrics of the audit culture are favorable (Klikauer & Link, Citation2021). These criteria include high student numbers and completion rates, satisfied students and excellent customer service feedback generated by anonymous surveys. The issue with focusing on growing student numbers can mean that the needs of the community we should be serving are backgrounded.

Colonisation and control of discourse by managerialism in appropriating such terms as ‘justice, choice, opportunity, student-centered, empowerment, and ownership’, provide a smoke screen of progressiveness whilst claiming a sense of validity. These discourses combine with actions to become a set of conditions, which enables or constrains possibilities for learners (McLean, Citation2006, p. 49). We contend that social work education must realign itself with the fundamental principles of social justice if we are to positively influence outcomes for Indigenous Australians. At the heart of inclusivity, engagement and retention is the concept of social justice. To Mooney (Citation2012) neoliberalism and globalization leave little room for social justice to occur. Giroux (Citation2010) concurs in that the neoliberal educational agenda reinforces hierarchical divisions like race, gender, class, and ethnicity, making values such as social justice and collective mutual learning impossible to maintain. Martínez Herrero & Charnley (Citation2021) highlights the importance of incorporating historical perspectives in reestablishing social justice frameworks, and they recognize the limited literature on the strategies and practices related to the transmission of concepts like human rights and social justice in social work education.

Managerialism’s validity is also attained by aligning managerial systems with discourses like quality assurance and subsequently the neoliberal managerial and bureaucratization of academia has created cumbersome systems that concurrently homogenize and standardize under this guise. Any new course must be approved by several layers of bureaucracy via standardized quality assurance documents. These documents are a form of centrally controlled regulation that adheres to the Australian Qualifications Framework. The language, wordage, assessments, and learning outcomes are tightly controlled, producing a uniformity across courses that comply with the regime. Course accreditation by the relevant professional body can provide another aspect of this uniformity. Morley and Stenhouse (Citation2020) contend that the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) has bought into the medical model for some areas of practice because of the attached economic imperative. AASW members who are credentialed specialist mental health practitioners through the AASW accreditation program, and who are in private practice, can apply for Medicare provider numbers. Medicare is a national health insurance scheme through which clients of accredited mental health social workers with provider numbers can claim a Medicare benefit for the fees charged. Morley and Stenhouse argue that this has resulted in some areas of social work practice being defined in more narrow psychological terms and that this has influenced parts of the social work curriculum across Australia given the role that the AASW plays in course accreditation.

This has resulted in social work practice being defined in narrow psychological terms despite the incongruence with social work values and that this has influenced the social work curriculum across Australia given the role that AASW plays in course accreditation. Apple (Citation1988) highlights that curriculum design is never politically neutral, with the legitimizing of certain knowledge above others and the current neo-liberalist drive in education to dictate what counts as knowledge in order to produce students who are passive consumers. We would take this further, in that the business culture and language of the current university system produces ‘consumers’ of knowledge who have paid for a product that also needs to meet student expectations of graduation and employment. This marketization is taken into social work practice, which has become a one-way transaction between the social work service and passive consumer, with service delivery steeped in the logic of supply and demand (O’Keeffe & Assoulin, Citation2021). This neoliberal educational regime is acculturating learners into a market economy driven by a political agenda to produce work-ready students able to enact and enforce colonially rooted social work policy. This is founded upon the premise that the market is the most efficient mechanism upon which to organize society. To Carey (Citation2021) for social work students, this reductive curriculum buys into a politically conservative and economically determined discourse shaped by employers and policymakers.

Neoliberalism has had a profound effect on remote communities in Australia on many levels. Like colonialism before it, neoliberalism is based on an individualistic philosophy, which runs contrary to the collective nature of community life for Indigenous people. Communities experience further fragmentation and families are pitted against each other, which in turn produces powerbrokers and gatekeepers that help maintain the status quo (Moss & Lee, Citation2019). If by producing social workers within this current education model, we are teaching learners to undermine social cohesion and trust, which are the foundations of a strong community, such practices can further compound the existing trans-generational trauma present in communities, these students will be working with.

Indigenous learners in higher education

In order to attract and retain Indigenous students, it is important to consider the demographics of the Indigenous cohort in higher education.

A report by Universities Australia (Citation2018, p. 20) shows a 5.3% decline in Indigenous enrollments in Universities in 2018. According to Universities Australia, the profile for Indigenous students in Higher Education in a reginal University is:

aged 30 years and over;

female;

non-school leavers;

undertake part-time study; and

come from a regional and remote area.

Accordingly, this profile has implications for student retention and completion in that, students can take longer to complete their course of study and often move in and out of study depending on employment, family, and cultural commitments. We argue that, in order to ensure engagement and retention that Indigenous students require a more personalized approach to education that is culturally relevant. This approach runs contrary to the neoliberalist assumption that for courses to be viable they need an evidence base, ever greater efficiency with ever increasing student numbers, while reducing student contact hours (Ball, Citation2012).

In regard to assessments, Bearman et al. (Citation2014) contends that the purpose of assessments is to support learning and generate grades, which should align with unit outcomes. Hussey and Smith (Citation2002) question the concept of learning outcomes as they give the appearance of measurability, which they contend does not exist. However, learning outcomes are embedded within the university’s technical requirements and in turn within the assessments, which are a form of measurement of approved knowledge rather than learning and growth of knowledge and thinking. Assessments are deemed necessary as a way to judge if a student has reached a certain standard in what Barnett (Citation2007) describes as the judgmental space of academia. To Boud and Falchikov (Citation2007), assessments must be judged by how they will influence students in the long term and therefore must take into consideration the socio-political context. This is particularly salient in the context of Indigenous students in needing to consider the student’s past experiences of schooling, assessments, and the relationship between assessments and pedagogy. Barnett (Citation2008) takes this concept of measurement further by stating that summative assessments are a form of discipline and control and has ‘spawned’ national quality control agencies to which these assessments comply. Barnett highlights the power and control aspects that underlie assessment and the influence of these. Dochy et al. (Citation2007) cites studies that highlight how assessments dominate student learning and as such should be used strategically and be ‘engineered to be educationally sound and provide a positive influence’ (p. 97).

Using both-ways and the third space in social work pedagogies

Creating new courses, which are innovative, whilst seeking to ensure inclusivity, engagement, and retention of Indigenous students, particularly those who live remotely, has its challenges. It entails being cognizant of the specific challenges that these students face such as access to and reliability of technology, English being a second, third, or fourth language, previous potentially negative experiences of the education system and cultural factors that influence learning styles. When these considerations are set against a colonised/neoliberal education system, steeped in managerialism, consumerism, and standardization, creating a course that puts Indigenous pedagogical priorities at the forefront seems diametrically opposed. Creating new courses that are innovative, whilst seeking to ensure inclusivity, engagement, and retention of Indigenous students, particularly those who live remotely has its challenges. It entails being cognisant of the specific challenges that these students face such as access to and reliability of technology, English being a second, third, or fourth language, previous potentially negative experiences of the education system and cultural factors that influence learning styles.

When education is viewed in the neoliberal paradigm, all learners are grouped within the category of ‘client or customer’, indicating they are participants of a transaction. That is, clients purchase the product of education to consume the knowledge placed on the menu within the course. What this looks like in terms of delivery, is courses offered predominantly online, with many materials prerecorded for convenient asynchronous access by the busy learner. By virtue of the neoliberal education context, consumers of education are assumed not to want or require connection with other consumers or academic staff, but rather access to consume at their own pace and outside of a learning community. While arguably, a learning community is offered to students, some opt not to participate due to time constraints and other life commitments. What then results from this model is a one-way transmission and consumption of information, and while a valid and fiscally beneficial approach to education, it is arguably not culturally appropriate.

Indigenous cultures are grounded in relationships, family, and connection to country. For Indigenous peoples, education is seen as not only benefiting the learner but also the learner’s family and community. Learning is therefore an embodied experiential journey, not a transaction. This requires the institution and its staff to prioritize establishing student connections and fostering educational relationships over time. Diametrically opposed to current neoliberal structures, it requires hierarchical structures to be flattened and critical thinking from Indigenous and Western perspectives to be considered. Above all, it is about removing power structures that influence and deter learners from bringing new voices and knowledge to the learning environment (Lowitja Institute, Citation2020).

Foucault suggests that dominant discourse produces power (Foucault, Citation1980) and that truth ‘induces regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth, its “general politics” of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as truth (as well as) the status of those who are charged with saying what counts’ (Foucault, Citation1972, p. 131). To Shalley et.al. (Citation2019), for meaningful change to occur in academia, the academy needs to acknowledge its very limited concept of what knowledge is and who can define it. Larkin highlights that until the underlying assumption that there is only one episteme and ontology, engagement of both Indigenous academics and students will remain limited. This concept sits well with the context of Indigenous knowledge and the underlying political and power structures that inform these discourses. To Giroux and Giroux (Citation2006) in order for critical thinking to occur, critical pedagogy must create the conditions that provide the ‘knowledge, skills and culture of questioning necessary for students to engage in critical dialogue with the past, question authority and its effects, struggle with ongoing relations of power and prepare themselves for what it means to be critical in the global public sphere’ (Giroux & Giroux, Citation2006, p. 10). To O’Keeffe and Assoulin (Citation2021) there is a lack of sociological-based critical focus in social work education, which means that graduates lack the skills to critically reflect on their own practice and the systems that impact it. To Morley and Stenhouse (Citation2021) critical analysis is needed in order to identify one’s own assumptions and reject those that are oppressive.

This is where a new educational learning environment, which makes explicit colonial and neoliberal influence is needed to promote critical thinking skills.

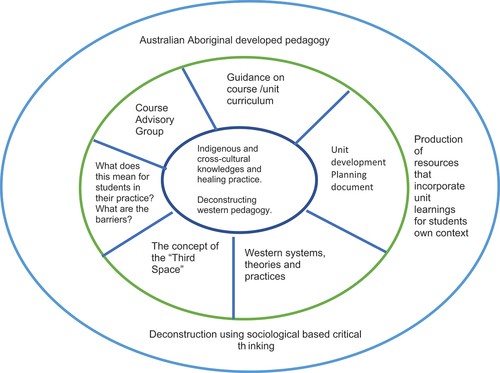

Indigenous knowledge for Carnes (Citation2014) involves a ‘third space’, which is defined as the space in-between Western and Indigenous paradigms. This third space aligns with the belief that the dominant Western paradigm is only one version of reality. It demands that the supposition of ‘truth’ be continually questioned in light of understanding and imbedding the Indigenous worldview. Atkinson (Citation2012) refers to the 5Rs respect, rights, responsibility, reciprocity, and relatedness as the core of an Indigenous critical pedagogy, which is not just about what is taught, but rather how that translates into how one conducts oneself in all interactions in both professional and personal life. This type of education is transformative (Carnes, Citation2015) in that the individual does not revert into old ways of knowing and being but grows by building on existing knowledge with new and emerging knowledge (Atkinson, Citation2012). It does not see knowledge and learning as a transaction, but rather as a vehicle to carry a strong Indigenous voice and knowledge. below presents a digram of this model.

The both-ways philosophy fosters learning through encouragement of the students to facilitate a balance between their own knowledge, language/s, and culture they bring to learning from previous education and life experience. Both-ways build an educational journey for the students by constantly including their home community and family, as part of the learning experience (Ober & Bat, Citation2007). Similar to the ‘third space’, both-ways learning privileges students existing Indigenous knowledge and ways of learning and provides opportunities to navigate between both Indigenous and Western knowledge and ways of learning. This is achieved by creating flexible learning contexts such as on campus, on country or at a student’s workplace. Allowing learners to tailor their own learning journey between Indigenous and Western knowledge, removes the rigidity of a transactional, approach which empowers learners to design their own safe and inclusive learning community.

Designing a curriculum built on relationship, trust, and authenticity

The creative therapy course sits within the College of Health Science and the discipline of Social Work. It is uniquely placed in being able to advocate for pedagogical change built on the premise of social justice without the interference of sometimes rigid course accreditation structures made by a professional body. It takes what we have learnt from our work on remote communities that was built on connection, trust, and authenticity and has embedded them into the educational context.

Social work education has a key role in prioritizing relationships, trust, and authenticity. To Walter & Baltra-Ulloa (Citation2019b) white social work educators need to ‘learn to unlearn’ which is about silence, deep listening, and forgoing power and control (p. 77). The concept of deep listening known in Daly River as Dadirri (Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr, Citation2021) is central to learning how to blend ideas and create new ways of knowing. Green (Citation2020) states that the knowledge and skills learnt must remain the property of the people who have shared it. To claim to be an expert in this area amounts to appropriation and is a colonizing act. According to Henderson et al. (Citation2015) for Indigenous people, relationship and connection are intrinsic to their being, and they cite capacities like identity, integrity, and authenticity as being critical. That is, Indigenous identity and ways of knowing are based on relationality. Building authentic connections with students in the education space demands a flatter, more circular approach to leadership. It is also important to demonstrate this approach in curriculum design and teaching by working in partnership with an Aboriginal teacher/Elder/s in all aspects of design and delivery. Gair et al. made a call for non-Indigenous social workers to relinquish their self-proclaimed expertise about Indigenous people, and instead to learn from the knowledge and wisdom of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including students (Gair et al., Citation2015). This would also provide leadership opportunities for these students whilst recognizing the knowledge and perspective they bring to the course.

Curriculum development for the new Creative Therapies courses, started from engagement with key stakeholders through a Course Advisory Group. This group included Indigenous Elders, Indigenous service providers, and educators, and they were tasked with unpacking what needed to be covered in each unit. Even though the courses are both post-graduate, there are special entry pathways for Indigenous people as a way of privileging Indigenous knowledge. We decided to incorporate the eight Aboriginal Ways of learning. ‘The eight ways belong to a place, not a person or organization. They came from a country in Western New South Wales. Baakindji, Ngiyampaa, Yuwaalaraay, Gamilaraay, Wiradjuri, Wangkumarra, and other nations own the knowledge this framework came down from’ (Yunkaporta, Citation2021). This pedagogical approach is not linear and includes aspects like deconstruction/reconstruction, community and land links, story-sharing, the non-verbal, learning maps, symbols, and images. These aspects are imbedded within each unit. The foundation unit starts from a critical thinking perspective as it invites students to unpack what critical thinking is, they are then encouraged to use these skills in looking at the theories and systems that impact their work. This includes systems such as child protection, education, mental health, biomedicine, and how government funding of services operates. Topics are then explored using the eight-way approach, which is where Indigenous knowledge is contextually explored.

There are no set texts for the course as this sits well with this pedagogical approach. Students can access written resources through the platform, but written texts are not central to learning. This is in acknowledgment that for many Aboriginal Australians, English may be a third or fourth language. The course is largely online so it was important to consider different interactive platforms that would engage the students. We chose a variety of ways for the students to interact. These include H5P’s, which has embedded quizzes and videos to work through the materials, Padlets, discussion boards, and VoiceThreads. We also offer a weekly Yarning Circle, which uses Zoom so students can interact with the lecturers and each other in real time. This is a useful platform to bring in relevant guests that can be taped for later access. We have also utilized these Yarning Circles to provide experiential learning. Harris and O’Donoghue (Citation2019) highlight the use of Yarning Circles in providing professional supervision, which provide a culturally respectful approach. This further attests to the usefulness of Yarning Circles across different aspects of social work education and practice for Indigenous students. This correlates with the authors' own findings in providing supervision for staff as part of our work with the therapeutic services mentioned earlier. In this instance, all staff participated in Yarning Circles for both professional supervision and as a way to share learning in co-developing the therapeutic model. We also offer an online 360-degree exploratory space where students can choose to further explore areas that feed into their assessment items. The assessment items are all scaffolded to encourage applied learning and are flexible in delivery mode.

Each unit works to deconstruct and critically analyze western knowledge by unpacking the underlying assumptions and questioning both the power base and their relevancy for the Indigenous and cross-cultural contexts. We bring into the forefront Indigenous knowledge systems, worldviews, and healing practices and in so doing create a ‘third-space’ as students explore what this space looks like for them and their practice. Within the restrictions of the online platform, we were also able to embed Aboriginal artwork created specifically for the course, as well as videos and audios to discuss the materials and give instructions. Continuous feedback about all aspects of the course is encouraged.

The move to online learning has also proved problematic for some remotely based students with limited computer and/or internet access. Bates (Citation2015) highlights the frustrations of the over-reliance on technology in that it tries to ‘fit human learning into the current restrictions of behaviorist computer programming’ (p.62). Further, Boyle et al. (Citation2014) state that current pedagogical approaches do not align with the technology. The use of technology also raises several challenges to navigate in the context of assessments. Rather than stipulating technology allowing students to assess their teaching and learning context and mold relevant to available and suitable technology for their context, it is important to consider what level of technological expertise we should expect from the student cohort. These considerations can then guide what additional scaffolding and support is integrated into the course.

Wilks et al. (Citation2017) highlights that online pedagogy must consider Aboriginal worldviews, cultural knowledge, and lifestyle. The online environment could include, for example, virtual meetings for cross-cultural exchanges, online learning communities, and a move to more visual instructions such as the use of multi-media to clarify complex topics. Imbedding Aboriginal art images and symbols in the content design and using devices such as narrative and storytelling rather than text-heavy platforms must be considered. It is also important to consider learning styles in the context of Indigenous learners. The posing and answering of questions are a very Western tradition and can cause discomfort for Indigenous people rather than let them be the teachers and use humor and connection (Wilks et al., Citation2017).

Findings

There are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students currently enrolled in the course from across Australia from a range of disciplines such as teaching, health, the arts, and human services including social work. Crucial to the integrity of the course is the role modeling of partnership and respect between the Aboriginal and Anglo lecturers. This partnership has been built on many years of working together. It has also been important to establish rapport with the students, which occurred in several ways. Many of the students wanted a chat about the course pre-enrollment. This was particularly the case for the Indigenous students, with some of them requesting Zoom meetings so that they could also see us. Promptness in responding to students was important.

We realized early on that students were struggling with navigating the online system. While instructions are supplied, going through the platform with the students often one-on-one provided confidence in their own skills and helped to increase their engagement. Many of the students had not studied for substantial periods, so anxiety levels were initially high. It was important to recognize this and provide strategies to counteract the impact. Internet access has been highlighted as an ongoing issue for remotely based students. In many remote communities, internet access is sketchy at best and non-existent at worse. The move to online learning and even just applying for the course online has proved highly problematic. We are having to consider other modes of delivery if we are to truly be inclusive of remotely based students.

A survey of students post-unit completion saw 52.4% of the cohort provide qualitative feedback on their experiences of studying using this decolonized approach. Students were asked to rank their overall teaching and learning experience out of 5 (0 low to 5 highest). The data show a ranking of 5.0 compared to a university social work unit satisfaction average of 3.9. Respondents were asked to provide feedback on the course teaching and structure via short answer survey to three questions. below provides a summary of questions and student feedback.

Table 1. Student feedback on teaching and learning.

Survey feedback while only of a small cohort from the pilot of the course suggests a strong support for a new and creative approach to teaching social work education. This is highlighted by both student comments and a significantly higher ranking in student satisfaction compared to other social work units.

Assessments are integral to the higher education system as highlighted above, but some interesting issues have arisen. Assessment items include learning maps, reflective learning activities, and ultimately at the completion of the course, students will have a portfolio of resources they can use in their own practice relevant to what they have learnt. The western education system of assessing and grading is so pervasive that some students initially struggle with flexibility and shifting their focus from assessment to learning. Some students have had to sit with the discomfort of learning within a different paradigm as well as change their focus to learning rather than on assessments and grades. Walking with these students as they negotiate this new ‘third space’ has occurred through a circular approach to leadership, which has helped provide a safer space to explore these issues than the traditional top-down approach provides. Being available to chat to students about their assessments and their concerns has helped alleviate the ongoing angst some students have voiced. The assessment items and the scaffolded learning embedded in the assessments have provided a mechanism for students to consider how they can take what they have learnt into their own practice. How might they decolonize their own assumptions and take this new knowledge into other colonized spaces. This is indicative of the transformative nature of this pedagogical approach.

Conclusion

This article began with the metaphor of The Rabbit Proof Fence through which the need to recognize complicity, power, privilege, and binary social constructs was explored. The concurrent legacy of colonialism and neoliberalism/managerialism on social work education within a regional university has highlighted the imperative that to truly decolonize both social work and social work education we need to reconnect with the underlying principles of social justice and equity. We have discussed the administrative and pedagogical challenges and highlighted ways to circumnavigate them. Research has highlighted the place of relationship, trust, and authenticity in education for Indigenous people. In order to decolonise social work education, we need to bring the ‘othering’ gaze back onto the self to deconstruct the ‘whiteness’ embedded in epistemology, ontology and pedagogy. Deconstruction of current theories and systems is integral to making explicit the underlying power dynamics. Without this first step, social work education will continue to view decolonizing strategies as an add on to their current knowledge, while maintaining current practices as well as the status quo. We have presented a pedagogical approach used in the formation of a Creative Therapy course built on relationship, trust, integrity, and authenticity. This transformative learning model is transferable across disciplines but is particularly salient for social work education and practice, given the disciplines legacy in the lives of Indigenous Australians. The experience of working in true partnership with an Aboriginal Elder/Healer/Artist, key stakeholders and community members and students in co-creating the Creative Therapies courses has provided a framework as we continue to explore this third space and create new knowledge in this space in-between.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. About 18,000 Indigenous children were living in Out-of-home- care at 30 June 2019 (AIHW.gov.au) with a release date of 18 May 2021.

References

- Apple, M. (1988). Work, class and teaching. In J. Ozga (Ed.), Schoolwork approaches to the labour process of teaching (pp. 99–118). Open University Press.

- Atkinson, J. (2012). Occasional address: Southern Cross university graduation ceremony, 4 May. Southern Cross University. http://scu.edu.au/graduation/download.php?doc_id=11610

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2017). Census of population and housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/lookup/2076.0main+features1102017

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Rate of children in out-of-home care remains stable. https://www.aihw.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/2021-1/may/rate-of-children-in-out-of-home-care-remains-stable

- Ball, S. (2012). Performativity, commodification and commitment: An I -spy guide to the neoliberal university. British Journal of Educational Studies, 60(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.650940

- Barnett, R. (2007). Assessment in higher education: An impossible mission? In Rethinking assessment in higher education (pp. 39–50). Routledge.

- Barnett, R. (2008). Assessment in higher education: An impossible mission. In D. Boud & N. Falchikov (Eds.), Rethinking assessment in higher education: Learning for the longer term. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.cdu.edu.auoquestcom.ezproxy.cdu.edu.au/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=292915

- Bates, T. (2015). Teaching in a digital age. Tony Bates Associates Ltd.

- Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D., Hall, M., Bennett, S., Molloy, E., & Joughin, G. (2014, September). Assessment design decisions framework. Australian Government. http://www.assessmentdecisions.org

- Bennett, B., & Green, S. (2019). Our voices: Aboriginal social work. UK.

- Boud, D., & Falchikov N. (2007). Rethinking assessment in higher education. Routledge.

- Boyle, A., Lockley, A., & Funk, J. (2014, April 22-24). Staff perspectives about gamefully designing Charles Darwin University. In AVETRA 17th Annual Conference. Surfers Paradise, QLD.

- Carey, M. (2021). Trapped in discourse? Obstacles to meaningful social work education, research, and practice within the neoliberal university. Social Work Education, 40(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1703933

- Carnes, R. (2014). Unsettling white noise: Yarning about Aboriginal education in WA prisons [ PhD Thesis]. Murdoch University.http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/22255

- Carnes, R. (2015, January 29-30). Critical indigenous pedagogy meets transformative education in a third space learning experience. In Teaching and learning uncapped. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Teaching Learning Forum. Perth, The University of Western Australia. http://ctl.curtin.edu.au/events/conferences/tlf/tlf2015/refereed/carnes.pdf

- Dittfeld, T. (2020). Seeing white: Turning the postcolonial lens on social work in Australia. Social work & policy studies: Social justice. Practice and Theory, 3(1). https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/SWPS/article/view/14278

- Dochy, P., Segers, M., Gijbels, D., & Struyven, K., (2007). Rethinking assessment in higher education: Learning for the longer term. In D. Boud & Falchikov N, Rethinking assessment in higher education. Routledge:

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge (S. Smith, Trans.). Tavistock Publications.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings. Pantheon.

- Gair, S., Miles, D., Savage, D., & Zuchowski, I. (2015). Racism unmasked: The experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in social work field placements. Australian Social Work, 68(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.928335

- Giroux, H. (2010). Bare pedagogy and the scourge of neoliberalism: Rethinking higher education as democratic public sphere. The Educational Forum, 74(3), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2010.483897

- Giroux, H., & Giroux, S. (2006). Challenging neoliberalism’s new world order: The promise of critical pedagogy. In N. Denzin, Y. Lincoln, & L. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Sage Publications. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686

- Green, J. (2020). The impacts of control, racism, and colonialism on contemporary Aboriginal-police relations. NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies (vol. 5, no. 1). https://doi.org/10.5130/nesais.v5i1.1564Vol

- Harris, T., & O’Donoghue, K. (2019). Developing culturally responsive supervision through yarn up time and the CASE supervision model. Australian Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1658796

- Henderson, D., Carjuzaa, J., & Ruff, W. G. (2015). Reconciling leadership paradigms: Authenticity as practiced by American Indian school leaders. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 17(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v17i1.940

- Hussey, T., & Smith, P. (2002). The trouble with learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 3(2), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787402003003003

- Klikauer, T., & Link, C. (2021 1). The idea of a university: A review essay. Australia Universities Review, 63(1), 65–74

- Liddle, C., Gray, P., & Prideaux, C. (2021). The Family Matters Report. Australia: SNAICC. https://apo.org.au/node/315514

- Lowitja Institute. (2020). Culture is key: Towards cultural determinants-driven health policy. Final Report. Lowitja Institute. https://doi.org/10.48455/k9vd-zp46

- Martínez Herrero, M. I., & Charnley, H. (2021). Resisting neoliberalism in social work education: Learning, teaching, and performing human rights and social justice in England and Spain. Social Work Education, 40(1), 44–57.

- McLean, M. (2006). Pedagogy and the university, critical theory and practice. Continuum International Publishing.

- McNabb, D. (2017). Democratising and decolonising social work education: Opportunities for leadership. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.221618

- Mooney, G. (2012). Neoliberalism is bad for our health. International Journal of Health Services, 42(3), 383–401. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.42.3.b

- Morley, C., & Stenhouse, K. (2020). Educating for critical social work practice in mental health. June 2020 social Work Education, 40(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1774535

- Morley, C., & Stenhouse, K. (2021). Educating for critical social work practice in mental health. Journal of Mining and Environment, 40(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1774535

- Moss, M. (2012). Broken circles to a different identity: An exploration of identity for children in out of home care in Queensland, Australia [ PhD Thesis]. James Cook University.

- Moss, M., & Lee, A. (2019). TeaH turn ‘em around healing: A therapeutic model for working with traumatised children on Aboriginal communities. Children Australia. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2019.8

- Ober, R., & Bat, M. (2007). Paper 1: Both-ways: The philosophy. Ngoonjook: Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 31(31), 64–86.

- O’Keeffe, P., & Assoulin, E. (2021). Using creative modalities to resist discourses of individualization and blame in social work education. Social Work Education, 40(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1703935

- Papadopoulos, A. (2017, January). Migrating qualifications: The ethics of recognition. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw038

- Parliament of Australia. (2017). Higher education reform. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201718/HigherEducationReform

- Shalley, F., Smith, J. A., Wood, D., Fredericks, B., Robertson, K., & Larkin, S. (2019). Understanding completion rates of Indigenous higher education students from two regional universities: A cohort analysis. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Shalley_Final_3.12.19.pdf

- State of Reconciliation in Australia Report. (2016). https://www.reconciliation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/truth-telling-symposium-report1.pdf

- Tamburro, A. (2013). Including decolonization in social work education and practice. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 2(1), 125–151. http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/29811

- Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr. (2021). Daddirri. https://www.miriamrosefoundation.org.au/about-dadirri

- Universities Australia (2018). Uniiversities Australia Indigneous Strategy First annual Report. Canberra. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/20190304-Final-Indigenous-Strategy-Report-v2-2.pdf

- Wallace, J., & Pease, B. (2011). Neoliberalism and Australian social work: Accommodation or resistance? Journal of Social Work, 1(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310387318

- Walter, M., & Baltra-Ulloa, A. J. (2019a). Australian social work is white. In B. Bennett & S. Green (Eds.), Our Voices (2nd ed., pp. 65–68). London, UK: Red Globe Press.

- Walter, M., & Baltra-Ulloa, A. J. (2019b). Australian Social Work is White, Our Voices: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work. In B. Bennett & S. Green (Eds.), Research Book Chapter (pp. 65–85). London: Red Globe Press.

- Walter, M., Taylor, S., & Habibis, D. (2011). How white is social work in Australia? Australian Social Work, 64(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.510892

- Watts, R. (2021). What crisis of academic freedom? Australian universities after French. Australian Universities’ Review, 63(1), 18–28.

- Wilks, J., Wilson, K., & Kinnane, S. (2017). Promoting engagement and success at university through strengthening the online learning experiences of indigenous students living and studying in remote communities. In J. Frawley, S. Larkin, & J. Smith (Eds.), Indigenous pathways, transitions and participation in higher education (pp. 211–233). Springer.

- Yunkaporta, T. (2021). Eight Aboriginal ways of learning. http://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-1/eight-aboriginal-ways-of-learning