ABSTRACT

From a longitudinal perspective, three successive directors of a Joint Master of Social Work program analyzed the process and strategies used in gaining Council on Social Work Education candidacy status and accreditation. Joint MSW programs are partnerships combining the resources of two or more universities to conduct one collaborative program. A literature review indicated that primary advantages for universities to create joint programs include innovative opportunity, social justice, the value of collaboration over competition, and cost savings for faculty lines. The process of building and negotiating a bi-university infrastructure, in addition to developing a new program, has many hidden complexities. Evidence-Based Management was a practical approach utilized during program development. The benefits and drawbacks of establishing a Joint MSW program are considered and can be used as a guide to determine if starting a joint program is warranted. Recommendations for how to establish a joint program are discussed along with the process of attaining accreditation. Key learnings during the process included developing fruitful collaborations, navigating value differences, understanding the importance of advocacy, assessing hidden costs, and managing necessary resource allocations. Given contemporary fiscal pressures within universities, it is important that joint programs develop a road map plan.

Introduction

The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) website indicates that as of July 2022, there were 313 accredited MSW programs in the USA (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022a, Citation2022c). In contrast, it is estimated that historically there were 9 collaborative or joint MSW programs nationally before the establishment of the joint MSW Program in the case study discussed in this paper (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). This number was estimated by analyzing CSWE’s list of accredited and formerly accredited MSW programs on CSWE’s website (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022a, Citation2022c). Since 2019, five collaborative programs have closed, and all have or are in the process of reopening as separate MSW programs. As of July 2022, only four active collaborative MSW programs are in operation (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022a). Each program varies in structure, student demographics, and degree of collaboration. The rationale for developing each program differs as well. Given the current number of active collaboratives, this is a timely analysis.

Defining joint masters’ programs

Although the terms joint degree program and dual degree program have at times been used interchangeably, there is a difference between the two. A dual degree program requires students to complete two separate programs at one or more universities. In contrast, a joint degree program is for a single degree with one curriculum designed and offered collaboratively by two or more universities. Various definitions of joint programs exist. In a report for the European Consortium of Accreditation, Aerden and Reczulska (Citation2013) defined joint programs as those which are developed and implemented jointly by two or more institutions. These programs follow the legal requirements of the corresponding higher education systems. Helms (Citation2014), along with the American Council on Education, defined joint programs as degree programs designed and delivered by two or more partner institutions in different countries where a student receives a single degree endorsed by each institution.

The idea of dual/joint collaboration among educational institutions is not new. Other disciplines such as nursing education have engaged in dual admission partnerships for some time. For example, students seeking a degree in nursing may be dually enrolled in an associate degree in nursing programs while concurrently earning hours toward a Bachelor’s of Science degree in Nursing (RN-to-BSN) (Smith, Citation2018).

In social work academia, joint programs also are referred to as ‘combined’ BSW/MSW programs or MSW/Ph.D. programs. For the purpose of this paper, a joint program is defined as a joint degree program located within two (or three) universities rather than separate degree programs within the same institution (Michael & Balraj, Citation2003). It should be noted that the CSWE also refers to these types of joint social work programs as collaborative programs. For the purpose of this paper, the definition of a joint or collaborative program is when universities are cooperatively involved in planning, developing, publicizing, and implementing one educational program at the Master’s level in the field of Social Work.

Advantages and challenges in developing joint social work programs

Two key studies have substantial implications for building joint social work programs. Johnson (Citation1990) interviewed administrators in nine BSW collaboratives to determine the significance of trends in development. Advantages for the programs included pooling resources and cost savings that enable small programs to survive. Disadvantages included the complexity of program administration and the difficulty with holding all faculty accountable for quality programming. Johnson (Citation1990) concluded that cooperation and planning are essential and that it is possible to minimize the challenges and build strong joint programs.

Notably, twenty-five years passed before Wang (Citation2015) published a qualitative study on joint MSW programs after interviewing administrators in six collaboratives. Wang found that these programs often sprang up from established BSW programs and served rural or less populated areas. The researcher reported that joint programs also added ‘bench depth’ to existing programs by increasing the variety of faculty teaching in the program. Challenges Wang identified were isolation between programs and the complexity of daily operations. Many of the same advantages and challenges are present for both BSW and MSW collaboratives. Wang noted that the idea of a collaborative based on Johnson’s (Citation1990) study did not result in a proliferation of collaboratives and that there is little empirical evidence about collaboratives and administrators who might want to develop one.

Other key considerations identified in the literature for universities to develop joint programs included averting a financial crisis, the enticement of cost savings when sharing faculty lines, increasing the number of MSWs to serve under-resourced groups in a geographic region, improving access to graduate education for racial minority persons in Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), and innovation and growth (Crowell & McCarragher, Citation2007; Jewett, Citation1998; Moore, Citationn.d.). Since little is known about joint MSW collaboratives, Wang (Citation2015) recommended conducting in-depth program analyses.

Case background

The universities analyzed in this investigation are located in a Southern State and have a history of active cooperation between their BSW programs. The local context is diverse and crosses rural, mid-size, and large metropolitan areas. The two universities are very close in proximity (about 2 miles), and one university is recognized as a teaching university with approximately 17,000 students. The other institution is classified as a research university, with over 40,000 students enrolled. At the time, University A, a teaching university, was designated as a Hispanic Serving Institution, and recently University B became both a research university and a Hispanic Serving Institution. Both Universities have long-standing BSW programs, and neither University has a Social Work Ph.D. Program.

Given the BSW programs’ 10 minutes across town proximity, students were often placed at the same field agencies, held joint field agency training, and the same community stakeholders served on each program’s advisory councils. The BSW programs had a long track record of collaboration. Based upon data from two informal needs assessments and a dearth of graduate programs in the immediate area, establishing an MSW program seemed to be a logical next step. Both universities agreed they did not have the resources to start an individual program, and thus co-designing and pooling resources made fiscal sense.

Due to cooperation over time, the two universities also had similar academic calendars, making collaboration much more feasible. One of the two university chancellors was a champion for establishing a joint program due to her past experience at another university. One dean who worked as a BSW social work faculty suggested the idea of starting a joint MSW program. Thus, there was strong support from the upper administration. University B’s BSW program was originally located in another department. The chair of that department presented a joint program proposal for consideration that was approved by the Dean and upper administration. After that, a bi-university steering committee was established. The committee began initial planning, and a subcommittee developed and finalized a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). An MSW program consultant, who later became the Founding Program Director and is the first author of this paper, was hired to develop course descriptions and seek both universities’ new program curriculum approvals. The MOU stated that the program directorship would rotate approximately every four years between the universities.

Theoretical framework and application

Reviewing the limited literature describing the development of joint MSW programs, Seck et al. (Citation2014) utilized group work theory to guide their joint program development. They drew from Tuckman’s (Citation1965) stages of group work, characterizing their development as forming, storming, norming, and performing. Their conclusions included the importance of communication, willingness to embrace change, and having an ethic valuing new program development. They also noted the importance of developing a program identity. Team mentality, formal and informal communication, and the use of cutting-edge technology for distance learning were also emphasized. Tuckman’s framework appears to apply more to internal departmental level program development. Understandably, a program would utilize the infrastructure, policies, and procedures already in place in a department to expand to the Master’s level.

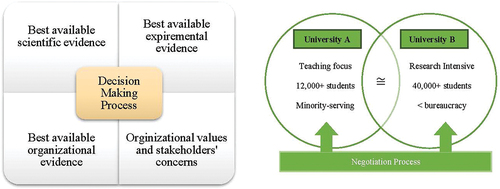

Nevertheless, there is a need to encompass and explain the multiple layers of systems change necessary to create a joint MSW program across two departments that are nested within two colleges and two universities. Evidence-Based Management (EBMgt) theory is a framework (Barends & Rousseau, Citation2018; Pfeffer & Sutton, Citation2006) that was found useful in explaining the specific efforts, strategies, and processes involved in building such a program. As the founding program director, the first author utilized EBMgt theory to establish and administer the Joint Master of Social Work (JMSW) program. EBMgt was borrowed from Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) and is defined as utilizing a ‘combination of critical thinking, and the best available evidence’ in decision making, which includes: a) scientific evidence and is traditionally defined as ‘scientific research’ outcomes; b) experiential evidence also known as practice experience and wisdom of practitioners; c) organizational evidence or information and data from the organization, and; d) stakeholder evidence including organizational values and stakeholders’ concerns (see ) (Barends & Rousseau, Citation2018; Pfeffer & Sutton, Citation2006).

Figure 1. Ebmgt/Decision making process (Barends & Rousseau, Citation2018).

It is important to note that there is a lack of research about using evidence-based management in social work organizations. Briggs and McBeath (Citation2009) presented a case study description about using EBMgt in a social service agency to improve program performance. The authors stated that utilization of EBMgt contributed to positive gains, including tripling the number of employees and obtaining licensure of a group home. They suggest further research due to barriers in implementing EBMgt. Nursing management scholars also noted that evidence-based nursing management is in emerging stages and should be taught in nursing programs (Shingler-Nace & Gonzalez, Citation2017). Further literature searches revealed no other articles to date focusing on the use of EBMgt strategies in developing and administering social work education programs. Therefore, this case study description and application of aspects of EBMgt provides application and insight into EBMgt.

Utilizing EBMgt as a theory-based strategy was beneficial because, throughout program development, each successive program director (the authors of this article) was able to provide evidence and rationale for decisions, and these decisions served as an accountability framework. Another aspect of this framework is the importance of considering the focus of the program curriculum based on the community context. For instance, (Osei-Hwedie et al., Citation2006) emphasized the importance of developing social work programs that are based on the local context and community needs. The evidence-based method used in developing this program prevented pitfalls, including myopic program leadership (Pfeffer & Sutton, Citation2006).

Scientific evidence and analytical benchmarking strategy

In addition to the field of management (Barends & Rousseau, Citation2018), a shortage of research about the administration of programs exists in social work education. The program directors consulted social work program literature, but the evidence was sometimes outdated (for example, studies published prior to development of CSWE’s Educational Policies and Standards (EPAS). Sometimes the best available scientific evidence was at odds; for instance, there was contradictory evidence from a teaching university in contrast to a research university. Therefore, a critical question to answer became, ‘What else is considered scientific evidence in the case of developing a joint master’s program?’

The founding program director utilized current social work education evidence by creating and undertaking a systematic benchmarking strategy. This began with a comparative analysis of information and data (e.g. policies, procedures, curriculum) from both JMSW’s BSW Programs. Then the director selected MSW programs within a specific geographic proximity of the JMSW program and an MSW program under establishment within the same state but much farther away. As needed, she examined information from other large state universities. The director also selected several top-ranked/well-known MSW programs in the USA (that shared some characteristics of the JMSW program or a similar concentration).

CSWE requires that social work programs publicly make certain aspects of their program information, such as mission statements, student admissions processes, course of study plans (Vliek et al., Citation2016). As a result, certain information (i.e. handbooks, admissions, field information) was typically available. Benchmarking entailed examining and systematically analyzing relevant organizational evidence/information from multiple programs to assess frequent standard practices. This strategy helped answer administrative questions such as, ‘What are MSW admissions standards in the geographic area?’

Best available experiential evidence

Each program director (the authors of this paper) had the experience of working in other MSW Programs. The founding director previously contributed to establishing an MSW program overseas. The directors also drew upon the expertise and administrative wisdom of the BSW program directors. Care was taken not to transpose the BSW model onto the JMSW Program because BSW education is pedagogically and substantively different from MSW education. Evidence-based managers do not rely solely upon their previous experiences while developing and administering a master’s program. This was a contributing factor to program success.

Administrative wisdom was also gained by navigating both university systems during the development of the program. The first program director passed along her experience to the second and the second director to the third. The third program director also served as the first field director and had gained insight from that perspective. One university had multiple changes in leadership at the college level, which added to the complexity of operations and negotiations. At times there were personnel vacancies at the universities that were not announced, and the openings were not filled immediately, which impacted the functioning of the JMSW program. Consequently, each program director gained university administrative wisdom by navigating through unexpected developments in a changing environment.

Best available organizational evidence

Since organizational evidence was gathered from two universities, it took longer to find and obtain it. Each successive program director drew upon evidence including but not limited to university data and statistics, university and college policy and procedures. Furthermore, the best organizational evidence and policies and procedures at each institution also differed. Sometimes this involved gathering data from other graduate programs within either university to identify which programs were most successful in implementing specific program processes. Occasionally, university data, such as enrollment, drove one university’s standards, which impacted the JMSW program recruitment strategies. Also, at times, university evidence and policies diverged from what was needed for CSWE candidacy status. Therefore, educating upper-level administrators about the accreditation standards, including the faculty-to-student ratio, became a necessary and ongoing endeavor for each program director.

Organizational and stakeholder values and concerns

The organizational values and stakeholders’ concerns seemed to be where differences emerged. The relational skills of the administrative team were needed to broker negotiations between the universities and stakeholders who held opposing views. In some cases, shuttle diplomacy between universities was necessary due to university administrators’ busy schedules to secure upper management approval. Some of the program elements had to be established in cooperation with both universities, requiring each program director to organize many scheduled and ad hoc meetings. Each of these elements took extra time for a program director and other personnel because of the bi-university partnership. For example, after an initial proposal at the program level before the first semester roll out, both universities agreed after long e-mail and in-person deliberations upon a fair solution of holding classes one day a week at each campus. Consensus building in any collaboration can be a lengthy and tedious process (Reilly & Peterson, Citation1997). The program directors found three helpful negotiation strategies. These included emphasizing partners’ overall common mission, focusing on the need for timely decisions, and encouraging the possibility of reevaluating decisions or direction in the future as needed.

Despite utilizing EBMgt in program development, the process was often not linear, straightforward, easy, or seamless. The program directors found that the development was complex and challenging. Each university had its own well-established infrastructure. Therefore, negotiation was intertwined with each aspect of the EBMgt decision-making process. Visually this could be depicted by superimposing the negotiation process (on the right) in within each quadrant of the EBMgt process from . Working with two partners with different policy and procedure infrastructures and values took additional discussion and time. The dual vision that emerged during these discussions led to finding a middle way forward. This sometimes involved one university taking the lead and sometimes it involved compromise. A team that was committed to making the partnership work was fundamental to the joint program’s success.

Phases and analysis of program development

The following discussion identifies the phases and analysis in the program’s development along with lessons learned along the way. Some of the main elements presented include a discussion of department infrastructure development across both universities and the strategy used to garner the needed structure. Examination of the two university infrastructures and the steps taken to build the JMSW infrastructure within the context of the two universities is also dissected. Key highlights from the phases of program development are presented to provide insights into the overall time frame and workload. The authors begin by discussing the evidence-based process of selecting the program’s concentration, given that this was a critical program decision that was made early on and set the entire foundation for the program’s curriculum.

Evidence-based decision-making example

Phase 1 - curriculum infrastructure—program concentration

One of the early decisions that needed to be made was the type of program concentration. Utilizing evidence-based decision-making, the founding program director provided a solid rationale for an Advanced Generalist Practice (AGP) concentration/specialization (Roy & Vecchiolla, Citation2004; Vecchiolla et al., Citation2001). In addition to analyzing both BSW programs, the best available evidence from other programs, examining the local context, and utilizing previous experience, the founding director also spoke to BSW faculty and administrators. Administrators and stakeholders at both universities unanimously accepted the director’s proposal of the AGP concentration. Additional positive feedback and confirmation about this evidence-based decision were provided in the CSWE Commissioner’s First Benchmark Visit Report. The Commissioner cited the AGP concentration as the best fit for the JMSW program within the regional context. The program specialization is a core component of the program’s identity, which fit a niche in the local context of being juxtaposed between both urban and rural environments.

Phase 2 – JMSW timeline– highlights year 1–illustrating workload

Program development highlights of the JMSW program timeline are provided in . Please note that it does not include prior program planning during Fall 2016. While not exhaustive, it gives a sense of the workload and some of the key steps taken, especially the heavy workload of the first year through to achieving CSWE accreditation. The authors chose not to include the specific CSWE Commission on Accreditation (COA) Candidacy Timeline that the program entered under because CSWE has changed some of the requirements since that time. Namely, the JMSW program was under the requirement that only Generalist (Foundation) students could be admitted during the program’s first year. Advanced standing students were only able to join beginning in year 2 of program development. Some of the key highlights included the CSWE Candidacy Benchmark document preparation process.

Table 1. JMSW timeline highlights.

Spring and summer year 1

There were real concerns about state hiring freezes and the potential loss of the JMSW faculty lines. Therefore, the JMSW founding program director pursued completing the benchmark documents in record time, spending many extra hours producing what CSWE commented on as a high-quality benchmark document. This was not typical of a usual faculty program director’s workload, even for new program development. At the same time, personnel searches were underway for the program field director, a JMSW faculty member, a BSW faculty member, and one department chair. During January through August of the first year, the program director consulted with University B’s Associate Dean as needed and with University A’s BSW program director. One of the early lessons learned during the first year was that an oversight had been the ‘uneven’ hiring, meaning that the universities did not bring the program director and field director on board at the same time. Both the State Board of Higher Education and the regional accrediting body were backlogged in workload. However, both approvals were received in time to begin the program.

Fall year 1

The department chair position at University B was not filled until August of the first year, and the appointment was an interim chair from within the university from another department. While the chair who joined in August of the first year was not from the social work professional field, she was familiar with University B’s processes and procedures, which was helpful. Due to the state hiring freeze, the administrative coordinator position at University B was not filled until October of year 1. Both of these personnel vacancies increased the founding director’s workload. At the same time, the BSW program at University B was undergoing CSWE reaffirmation.

The new JMSW field director at University A was hired, along with an associate professor at University B in the Fall of the first year. Filling the department chair at University B and the JMSW personnel positions made it possible to roll out the program with its first cohort of generalist students. In the fall semester of year 1, the second-year syllabi and field education manual were finalized.

Spring year 2

The First Benchmark Site Visit was very successful, and the Commissioner’s main recommendation was that the program director and field director receive additional course releases. The JMSW founding program director’s request to the dean to return to faculty after a year and a half was fully supported. Deans at both universities recognized the extra work the founding program director had undertaken, especially given the personnel vacancies. Recommendations from subsequent Commissioner site visits related to enhancing the administrative structure are discussed in the administrative infrastructure section.

Phase 3 - university infrastructure and creating program infrastructure

Metaphorically speaking, establishing a joint program is like trying to physically combine two buildings across many differences. At the level of relational values and concerns, it was like blending two different families. The initial steering committee decided that the highest standard would be followed in terms of any policy and procedure, for example, GPA for admissions. Sometimes policies were aligned while other times not, so either one policy had to be chosen or the other or a new policy created. In terms of Student Services, such as the recreation center or students’ counseling services, the students were required to access their ‘home’ university services.

During the Spring and Summer of the first year, many elements were created, including but not limited to a joint program admissions application and process, a joint program parking pass, a handbook, a program website, and a shadow registration system. Collaboration was required on many fronts. For example, the JMSW director and BSW program director from University A worked with the corresponding admissions departments at both universities to develop and pilot a joint registration process. Applicants were randomly assigned to one university or the other, and then they applied through a centralized statewide admissions portal for all state universities. Students were assigned a ‘home institution’ upon admission to the program. An exception to the random assignment was made for university employees who qualified for their institution’s scholarship. The assignment was created to ensure that student numbers were equitable and enabled revenue sharing between the two Universities. While there was potential for challenges with the random assignment or student perceptions about the reputation of universities, everything went smoothly. It is helpful to note that these could be possible issues that other universities might face.

To ensure co-ownership in cohort selection, everyone reviewed the applications when JMSW faculty came on board. The joint parking pass was considered a major milestone after Parking Services personnel at both universities collaborated. These collaborations involved setting aside old procedures to creatively establish new ones. Building the JMSW infrastructure was an iterative process. Extra planning and coordinating was an ongoing endeavor to improve the ease of operations and align with university process modifications or even personnel changes. The program directors and later the chairs were actively involved with each other across systems to continue building and implementing changes and improvements.

One of the challenges during the first-year rollout was that there was no dedicated JMSW online learning platform. Therefore, students had to log in to each university’s online learning platform to access their classes. Creating a seamless interface for the online learning system across two universities took several years. The second program director was persistent in locating a key person at University B who brainstormed an innovative solution to create the single login. Often the authors found that simply conducting informal in-person meetings with the key persons, rather than e-mails and large meetings, was the formula for successful collaboration.

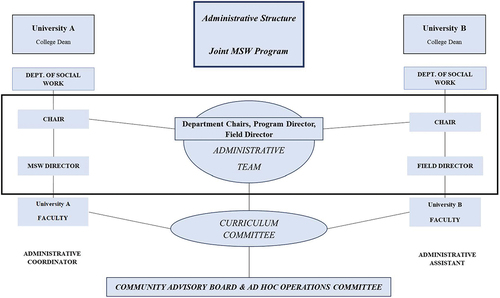

JMSW administrative infrastructure development

When starting a joint MSW program, it is vital to assess the adequacy of the departmental infrastructure. University B was granted social work department status at the beginning of the program development process. However, there was no department chair. Initially, the founding director for the JMSW program was hired to work in the BSW program. As was mentioned earlier, there was no administrative support for the JMSW program at University B until October of the first year due to a state hiring freeze. Due to resource issues, University A did not create a standalone social work department. University A’s BSW Program director assisted when possible, but his main focus was the BSW program.

In the second year of program development, the JMSW hosted its second Commission on Accreditation visit. Both first and second-year visits were successful. However, during the second visit, the Commissioner had significant concerns about the JMSW programs’ administrative structure. The Commissioner recommended that University A become a recognized social work department and that a position needed to be created for a department chair to align with University B (see ). CSWE’s feedback was the advocacy vehicle for University A’s program director to advocate to upper-level administrators to obtain resources from both universities to facilitate program success. The department chair at University B developed an administrative structure diagram from the Commissioner’s visit, which outlined how the social work administrative structure could better embody co-leadership. The chair of University B and the program director at University A advocated for these changes at both universities based on the CSWE recommendations, and the universities finally approved this structure. These structural changes were needed to ensure adequate staffing and the program’s ongoing success.

Phase 4 - faculty standards

The development and negotiation of faculty standards included elements such as promotion and tenure research expectations and teaching loads. In the JMSW program, the faculty reported to and were evaluated by the department of their home institution. This included completing the university’s annual evaluation process. The JMSW program required that faculty undertake teaching evaluations through peer teaching observations, and that was on occasion done across campuses and was beneficial for junior faculty on the tenure track. The teaching and research workload varied, given that one university was research-focused while the other was teaching-focused. However, the universities agreed that the MSW teaching loads would be the same at both universities. Faculty benefitted by having two university affiliations and being able to access both university libraries. Faculty agreed to teach at both campuses while retaining an office at their home institution.

Soliciting student feedback and involvement

Educating students to become future social workers is the main aim of any social work program. Facilitating a successful learning and teaching environment in explicit and implicit milieus is vital. Therefore, feedback about the program in a process evaluation format was sought each semester in the first several years. Students also had the opportunity to complete the standard university course teaching evaluations, and additional attention was paid to this student feedback in the context of program development. The authors were able to address student feedback, questions, comments, and concerns through process evaluation and, where needed, implement change. Some feedback included students appreciated having classes at both campuses and the opportunity to utilize both libraries. Due to the small size of the cohort during the first year, activities were planned, such as pizza lunchtime gatherings with students and faculty. In years 2 and 3, a formal student organization was established with faculty advisors.

All JMSW faculty were assigned to advise students following standard university practice. Typical of masters’ programs, a separate JMSW graduation was planned and held. Students stated they felt a strong program identity during the program and even at the end. They took pride in earning a joint degree from two universities, and the JMSW logo was seen on some students’ mortarboards at graduation. Students provided feedback that they felt it was beneficial to earn a degree from two universities in a ‘joint program’. As required, student learning outcomes were collected and reported to CSWE in year three.

Students and faculty: implicit and explicit emphasis on diversity

JMSW students were often ethnically and racially diverse but some had less exposure to diverse populations. An advanced human diversity and multicultural course was included in the curriculum. The founding program director also proposed the establishment of a diversity committee in her department to continue to infuse diversity into the learning environment and implicit curriculum. The committee helped to support BSW and MSW faculty in critical efforts to teach students about diversity and prepare them for practice by continuing to gain further self-awareness about values, bias, and privilege. When working at another university, the founding director and colleagues had implemented diversity training and evaluation for students (Saleh et al., Citation2011). Due to the findings from that research and based upon her experience teaching in the BSW program and JMSW process evaluation student feedback, she proposed that all JMSW faculty and students receive training from University B’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion. The BSW and JMSW faculty embraced the opportunity. The field director, who later became the third program director, was highly committed to diversity education and led a cross-university faculty collaboration in this area (Colvin et al., Citation2020). This commitment led to the program director seeking out and securing a grant for diversity simulation equipment to train students in developing culturally competent practice skills using simulated instruction.

Discussion

This article fills a void in the literature by synergistically combining two key understudied areas, use of Evidence-Based Management and decision-making, and a case study illustrating the process of establishing a Joint Master’s of Social Work program. The case study description and approach is timely given that limited literature is available (Patton & Applebaum, Citation2003). One of the purposes of this review is to provide information to help faculty and administrators decide if starting a joint program is feasible and logical in their settings. While it would have been impossible to describe and examine every aspect of program development in this paper, key development components were analyzed, and significant findings were presented. In this case, Evidence-Based Management was an instrumental and solid approach to develop the program at all levels. This theoretical approach supported Wang’s (Citation2015) observation that collaborative social work programs require increased scientific inquiry into decision-making in order to strengthen them.

The results showed the extensive nature of building a JMSW infrastructure in two university settings at all levels. In support of these findings, Moore (Citationn.d.), in his unpublished history of the Joint Program in North Carolina, acknowledges that coordinating with both universities on developing all elements (such as registrations, bookstores, libraries, orientation procedures) are monumental challenges. This labor-intensive process was also iterative, given the ever-changing nature of universities and personnel. The program and department administrative infrastructure required for expansion was another key finding in this case. The need to further develop program administrative infrastructure at both universities was resolved through ingenuity and advocacy to upper-level administrators. The fuel for the advocacy was the CSWE Commissioner site visit recommendations.

Another finding is that the Joint MSW Program Director role required dual vision in every consideration and endeavor to build co-ownership and consensus. A hidden cost consists of the extra time directors spend building and administering programs. Developing the JMSW program was groundbreaking and innovative, but it was also complex and multidimensional. Establishing any new program takes more time and work, and the workload for developing a bi-university program is arduous. The program directors had the opportunity to be deeply involved on multiple levels in two universities (infrastructures), which is not typical for program directors in existing or new programs at one university. Various university administrators remarked they noticed the joint program directors’ extra work. Program directors must utilize systems-level thinking, track multiple tasks, and utilize a skill set of attention to the large picture and the small details.

Recommendations

Programs wanting to develop a joint MSW program need to determine if the JMSW model is a good fit and realistic given the time commitments and phases involved in the development process. In pondering the goodness of fit, consider the following aspects.

Needs assessment, establishing a logical purpose, and inclusion in college strategic plan

As with any new program, a needs assessment should be undertaken with prospective students and community stakeholders. Establishing a clear and logical purpose for the collaboration beyond cost-sharing is critical. Including JMSW or MSW development plans in the department and college’s strategic plans would be an initial step to ensure BSW faculty and the college’s leadership start up and ongoing support. Given the dynamic process of program development and maintenance, active steering committees and councils are fundamental to working together at all levels. Infrastructure is critical to sustainability. Wang (Citation2015) emphasized the need to educate administrators about the unique aspects of collaboratives. Universities are not necessarily in the habit of developing additional infrastructures to accommodate new programs.

Assess the existing social work programs’ infrastructure and staffing

Based upon this case analysis, adequate social work personnel and resources should be established from the beginning. This includes realistically assessing the structure of both social work programs and how they blend and support each other. In the case of the JMSW program, separate social work departments were required to ensure the future success of the JMSW Program. Sufficient and even robust faculty and administrative staffing of the BSW programs is recommended, especially given that social work literature states that BSW resources are sometimes inadvertently rerouted to develop new MSW programs (Zeiger et al., Citation2005). While assessing the BSW faculty and administrative capacity and bandwidth, it is helpful to note when BSW programs are undertaking accreditation reaffirmation in relation to developing a joint MSW program.

Planning—logic model

An evidence-based step includes consulting research about University Joint Programs (Wang, Citation2015), given recent university strategies to cut costs. A critical recommendation for the JMSW planning stages and proposal includes developing a program logic model to identify and justify the resources needed (LeCroy, Citation2018; Openshaw et al., Citation2011). The logic model can serve as a guide and advocacy tool to ensure sufficient resources are granted for program development. This includes a realistic timeline for program development, including but not limited to CSWE benchmark development within the context of the program director and faculty workload. In the long run, the logic model can be updated and revised for program evaluation purposes and additional strategic planning (Greenfield et al., Citation2006). Selecting a curriculum concentration(s) that fits the contextual needs and program size can increase program sustainability and stakeholder support.

Cultivating collaborations

Several key points are recommended for joint program directors to cultivate collaborations, navigate value differences, and advocate for new joint programs. First, recognize the importance of relationships, whether through small group meetings or in-person visits. The authors found that for the program’s success, relationships must be reciprocal and persist over time. In this case, the directors took the opportunity to cultivate relationships across campuses. Expressing appreciation for colleagues’ efforts contributed to positive collaborations. It is important to find allies within universities that want the program to succeed. Second, utilize dynamic systems thinking and analysis to proactively think and take action on multiple levels. An iterative dialogue process is needed where micro and macro development intertwine and co-occur. Third, there must be ongoing advocacy by the program’s leadership to upper-level university administration officials about the program’s needs. This includes continuous efforts to educate upper administrators about CSWE regulations and requirements. It should be kept in mind that the Commissioner’s Site visits may serve as a helpful tool in the education and advocacy process.

Other lessons learned—timeline and workload

Other suggestions include establishing a longer launch period with additional planning and including ‘even hiring’ so that the program director and the field director begin simultaneously. It is helpful to plan for the CSWE Benchmark process in advance, including the related costs associated with accreditation. The workload of establishing a new ‘joint’ program across two universities must be considered. Universities need to give workload credit for extra time spent developing a new program and infrastructure. In that vein, course release for the program leadership should be sought and granted. It is helpful for university-level administrators to understand that building a joint program does not entail merely expanding a BSW program. It requires an intensive commitment of time and energy, and the CSWE Candidacy process and documentation time considerations need to be fully grasped.

Conclusion

This paper explored and analyzed the establishment of a Joint MSW program and adds to the literature about joint social work programs. It provides a case study of program development and could also be useful in administration and management courses in social work education as a case example of complex program development. The analysis presented the intricacies of program development within two university systems, including examples of Evidence-Based Management as a theoretical decision-making tool that was instrumental in program establishment. The evidence-based management model has the potential for broader use, not only for academic program development, but also for social work program administration and management in communities. Finding research evidence to answer program development questions was a practical method to develop the program. Highlights from the program development timeline were presented along with an analysis of program infrastructure development and information about faculty standards and student feedback. Ongoing evaluation and quality improvement were utilized, which is vital for any program.

It is necessary to bear in mind that only four Collaborative MSW programs in the USA are currently operating. In contrast, it is estimated that 10 MSW Collaboratives have existed historically (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Although the purpose of this paper was not to analyze why collaborative MSW programs have closed, it appears that Joint MSW programs have served as stepping stones or springboards that led to individual programs opening up separately at their own institutions rather than as programs that are necessarily sustainable over time. While some collaborations have lasted for many years and have successfully graduated many social work student cohorts (Greater Rochester Collaborative (GRC) MSW Program, Citation2019; St. Catherine University, Citation2018) it appears that others have served a purpose of facilitating program establishment and launch. Future research about social work collaborations, whether open or closed, is warranted to gather additional insights about joint program development, operations, process, and outcomes. This type of evidence may further assist social work administrators and university personnel in determining if developing a joint social work program would be a realistic endeavor in their context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mahasin F. Saleh

Mahasin Saleh is an Associate Professor in the MSW Program in the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies in Qatar. Currently, she is in her second term serving as a member of the Global Commission on Social Work Education for the Council of Social Work Education (USA).

Sharon Bowland

Sharon Bowland is an Associate Professor, the Director of the DSW Program, and the Coordinator of the Gerontology Certificate Program in the College of Social Work at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, USA.

Alex D. Colvin

Alex Colvin is an Associate Professor and Chair of Undergraduate Programs in the School of Behavioral Health and Human Services a the University of North Texas at Dallas, USA.

References

- Aerden, A., & Reczulska, H. (2013). Guidelines for good practices for awarding joint degrees. European Consortium for Accreditation in Higher Education. Occasional Paper. The Hague. http://ecahe.eu/w/index.php/Guidelines_for_Good_Practice_for_Awarding_Joint_Degrees

- Barends, E., & Rousseau, D. M. (2018). Evidence-based management: How to use evidence to make better organizational decisions. Kogan Page.

- Briggs, H. E., & McBeath, B. (2009). Evidence-based management: Origins, challenges, and implications for social service administration. Administration in Social Work, 33(3), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643100902987556

- Colvin, A., Saleh, M., Ricks, N., & Rosa Davila, E. (2020). Using simulated instruction to prepare students to engage in culturally competent practice. Journal of Social Work in the Global Community, 5(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.5590/JSWGC.2020.05.1.01

- Council on Social Work Education. (2022a). CSWE directory of accredited programs. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/directory/?

- Council on Social Work Education. (2022b). CSWE directory of formerly accredited master’s of social work programs. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.cswe.org/Accreditation/Directory-of-Accredited-Programs/Formerly-Accredited-MSW-Programs

- Council on Social Work Education. (2022c). CSWE program membership. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.cswe.org/Membership/Program-Membership.

- Crowell, L. F., & McCarragher, T. (2007). Delivering a social work MSW program through distance education: an innovative collaboration between two universities, USA. Social Work Education, 26(4), 376–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470601081688

- Greater Rochester Collaborative (GRC) MSW Program. (2019, September 2). Faculty and staff of the greater Rochester collaborative masters of social work program gathered for the last time to celebrate. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/GRCMSW/

- Greenfield, V. A., Williams, V. L., & Eiseman, E. (2006). Using logic models for strategic planning and evaluation. Application to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2006/RAND_TR370.pdf

- Helms, R. M. (2014). Mapping international joint in dual degree programs: US program profiles and perspectives. American Council on Education. https://unicen.americancouncils.org/mapping-international-joint-and-dual-degrees-u-s-program-profiles-and-perspectives/

- Jewett, F. (1998). The master’s degree in social work at Cleveland state university and the university of Akron: A case study of the benefits and costs of joint degree program offered via video conferencing. Case Studies in Evaluating the Benefits and Costs of Mediated Instruction and Distributed Learning. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED422788.pdf

- Johnson, J. H. (1990). Baccalaureate social work education consortia: Problems and possibilities. Journal of Social Work Education, 26(3), 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1990.10672157

- LeCroy, C. W. (2018). Logic models for program design and evaluation. Encyclopedia of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1273

- Michael, S. O., & Balraj, L. (2003). Higher education institutional collaborations: An analysis of models of joint degree programs. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 25(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080032000122615

- Moore, W. R. (n.d.) History of the Joint Master of Social Work Program. https://hhs.uncg.edu/jmsw/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2013/11/History-of-JMSW-Program.pdf

- Openshaw, L. L., Lewellen, A., & Harr, C. (2011). A logic model for program planning and evaluation applied to a rural social work department. Contemporary Rural Social Work Journal, 3(1). https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/crsw/vol3/iss1/6

- Osei-Hwedie, K., Ntseane, D., & Jacques, G. (2006). Searching for appropriateness in social work education in Botswana: The process of developing a Master in Social Work (MSW) programme in a ‘developing’ country. Social Work Education, 25(6), 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470600833469

- Patton, E., & Applebaum, S. H. (2003). The case for studies in management research. Management Research News, 26(5), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170310783484

- Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. I. (2006). Evidence based management. Harvard Business Review OnPoint. https://hbr.org/2006/01/evidence-based-management

- Reilly, T., & Peterson, N. (1997). Nevada’s university-state partnership: A comprehensive alliance for improved services to children and families. Public Welfare, 55(2), 21–28.

- Roy, A. W., & Vecchiolla, F. J. (Eds.). (2004). Thoughts on an advanced generalist education: Models, readings and essays. Eddie Bowers.

- Saleh, M. F., Anngela-Cole, L., & Boateng, A. (2011). Effectiveness of diversity infusion modules on students’ attitudes, behavior and knowledge. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 20(3), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2011.594995

- Seck, M. M., McArdle, L., & Helton, L. R. (2014). Two faculty groups’ process in delivering a joint MSW program: Evaluating the outcome. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2013.845125

- Shingler-Nace, A., & Gonzalez, J. Z. (2017). A pathway to evidence-based nursing management. Nursing, 47(2), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000510744.55090.9a

- Smith, A. A. (2018). Public and private institutions partner to produce more nurses, more quickly. Inside HigherEd. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/11/21/unique-nursing-programs-allow-students-earn-associate-and-bachelors-degrees

- St. Catherine University. (2018). Statement form St. Catherine, St. Thomas Presidents on School of Social Work. https://www.stkate.edu/news-and-events/news/statement-from-st.-catherine%2C-st.-thomas-presidents-on-school-of-social-work

- Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100

- Vecchiolla, F. J., Roy, A. W., Lesser, J. G., Wronka, J., Walsh-Burke, K., Gianesin, J., Foster, D., & Negroni, L. K. (2001). Advanced generalist practice: A framework for social work in the twenty-first century. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 21(3–4), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v21n03_08

- Vliek, A. S., Fogarty, K. J., & Wertkin, R. A. (2016). Are MSW admissions models working? An analysis of MSW admissions models as predictors of student success. Advances in Social Work, 16(2), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.18060/20822

- Wang, D. (2015). The development and administration of collaborative social work programs: Challenges and opportunities. On the Horizon, 23(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-08-2014-0028

- Zeiger, S. J., Ortiz, L. P., Sirles, E. A., & Rivas, R. (2005). Organizational development continues: Adding an MSW program to an existing BSW program. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 11(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.11.1.40