ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the curriculum development for social work student placements in primary health care. Social work in General Practice [GP] is an emerging area for social work practice, able to fill a gap in primary health. The inclusion of social work in GP practices can be complex. Social work placements offer an opportunity for students to become familiar with this practice setting and undertake social work relevant learning; however, they need to be well prepared for such placements and able to articulate and use social work knowledge and processes. They offer an opportunity for GPs to understand what social workers can do and offer to the GP community. We have used available research, support of an active reference group and two surveys to develop a curriculum for social work students in GP practices. We provide an overview of the literature and the methods of developing the curriculum. We describe how feedback and curriculum design principles were used. Core aspects of the curriculum and accompanying resources are outlined. The discussion highlights that the curriculum was a valuable tool in not only inducting students into a GP placement setting but as a meaningful reference guide throughout the entirety of placement.

IMPLICATIONS

Social work students undertaking placements in GP settings need to be able to understand and articulate the role of social work in primary health care;

A curriculum for social work placements in primary health care provides students the opportunity to consider the clinic context, the role of social work in primary health care and getting started in GP settings;

Feedback and guidance from a range of interdisciplinary stakeholders is invaluable in developing resources for interdisciplinary work.

Background

As the entry level to health care, primary health care is generally a person’s initial encounter with healthcare systems (AIHW, Citation2016). In Australia, primary health care includes general practice [GP], allied health, pharmacy, nursing, dentistry, health promotion, maternal and child health, women’s health and family planning (Swerissen et al., Citation2018). Broadly, it includes a range of interventions and services, from treatment and management of acute or chronic conditions to health prevention and promotion and can be delivered through GP and integrated health care to improve population health (AIHC, Citation2016; Foster, Citation2017). Challenges for primary health care include the coordination and integration of health-care services in particular for those who are aging and income-poor or who have two or more chronic and complex conditions (Swerissen et al., Citation2018). GPs generally coordinate the care of patients and are the referral point for specialists. GPs provide medical care, disease prevention as well as health education and advice to a range of patients across their lifespan (Swerissen et al., Citation2018). A range of issues, including an aging population and a reduction of informal community support (Swerissen et al., Citation2018), are putting increasing demands on GPs. This pressure could be alleviated through increased collaboration between GPs and Allied Health professions such as social work (Hartung & Schneider, Citation2016).

Social workers are qualified to contribute to the provision of effective primary health care to ensure comprehensive and holistic analysis of a patient’s situation (Hudson, Citation2014). For example, in New Zealand social workers are increasingly placed in GP practices as they ‘ … have been identified as a suitably qualified health professional group that can support the medical profession, bringing appropriate theoretical foundations, knowledge and skills to the clinical setting’ (Döbl et al., Citation2015, p. 333). The Australian Association of Social Workers [AASW] outlines the broad range of social work interventions in health such as family support and intervention or working with bereavement, grief and loss; and therapeutic interventions to address chronic health conditions. Social work practice includes risk assessment, crisis intervention, case management, group work, advocacy, policy development, and research (AASW, Citation2015).

To date, there are limited studies about social workers in primary health care. Hartung and Schneider (Citation2016) found that social work in primary health care generally focused on responding to psycho-social problems across the lifespan, particularly, patients who face complex care and health needs. Social workers can support the social health care and wellbeing for patients in GP clinics (Hudson, Citation2014) and, unsurprisingly, integration of social workers in general practice can facilitate better health outcomes for population groups that are particularly vulnerable or facing health inequalities (Döbl et al., Citation2015). Social workers in primary health care explore pathways for referral and respond to issues such as domestic violence, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], sexual assault, or homelessness that adversely affect people’s health (Campbell et al., Citation2009; Coid et al., Citation2016; Hwang, Citation2001; Koziol McLain et al., Citation2008; Safren et al., Citation2013). Social workers in GP practices facilitate the exploration of a patient’s health issues in the context of wider issues such as family, lifestyle, community, and housing (Hudson, Citation2014). An integration of social work in GP practices can focus on prevention, self-care, enhancing primary care, and facilitating care in the community and people’s homes (College of Social Work. Royal College of General Practitioners [COSW.RCGP], Citation2014).

However, there can be a professional divide between health and social care; GPs and social workers can ‘ … fail to understand each other’s unique role, responsibilities and perspectives, barriers that may have to be dismantled through inter-professional education, co-location and informal networking, among other things’ (COSW.RCOGP, Citation2014, p. 3). Hartung and Schneider (Citation2016) argue that while collaboration between GPs and social workers could be beneficial for primary health-care systems, GPs have limited understanding of social work and how they could work with social work professionals. Moreover, organizational barriers such as a lack of funding and resources, space, and patient allocation processes and capturing social work in medical business systems make the inclusion of social work in GP practice complex (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review).

There are few social workers working in primary health care, resulting in limitations to what psycho-social problems can be addressed, social workers generally working with the more serious cases (Hartung & Schneider, Citation2016). Overall, while there are increasing numbers of social workers in GP practices in the US (Lombardi et al., Citation2019), there is potential to increase the collaboration between social work and primary health through further co-location of social workers in primary health settings (Bako et al., Citation2021). Co-location can lead to improved patient outcomes and stronger interdisciplinary health teams (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review).

For social workers to participate in an integrated primary health-care model, it is important to be able to articulate the role of social work to interdisciplinary team members who might not be aware of what social work can offer. Social workers need to have ‘ … an in depth-understanding of their roles on the integrated health care team and thus the ability to articulate this role to other team members’ (Held et al., Citation2019, p. 56). Importantly, social workers need to be able to articulate their value to primary health care and develop specific skills and knowledge for this setting through social work education and professional development (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review). Yet, one of the shortcomings of social work can be the clear articulation of what it has to offer in primary health-care settings (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013).

Field education is an integral part of social work education. Social work students’ field education locates students in a specific agency setting so they can learn about themselves and generate knowledge and skills as a beginning social worker (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). The goals of any placement are to provide students with opportunities to utilize evidence—based theories and knowledge, to help them understand the professional social work role and develop a sense of professional social work identity, to broaden students’ understanding of competence and culture, to improve their interpersonal skills, apply critical thinking skills and to develop their self-awareness and skills as a reflective practitioner (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). de Saxe Zerden et al. (Citation2018) outline the value of collaborative field education opportunities for students from a range of health disciplines to create interprofessional learning environments. The authors argue that for social work students and their peers from other disciplines these environments would facilitate them to be trained in an interprofessional model of care through field education practice that is in vivo (de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018). As such placements in the general practice setting can prepare students for graduate social work in primary health care.

Students need to be supervised by a qualified social worker; however if there is no social worker available in the organization to provide the professional supervision, a field educator can be appointed externally from the agency (AASW, Citation2020). Students then receive external social work supervision as well as guidance from an internal organizational representative known as a task supervisor. The external supervision of social work students is becoming more common, with some universities in Australia providing up to 50% of their field education students with external supervision (Zuchowski et al., Citation2019). While external supervision can provide a valuable learning experience for students and allow students to critically reflect on and develop their practice, students can feel disadvantaged without the onsite social work presence. The lack of immediacy to access onsite supervision and the lack of opportunity to be observed or to observe the practice of the social work field educator are challenges students face (Cleak et al., Citation2022; Egan et al., Citation2021).

Social work student placements in GP settings can promote interdisciplinary understandings; students can learn about GP and GPs, nurses and other allied health staff can acquire further understanding of what social work can offer. Students on placement can contribute to the daily tasks and service delivery within each participating primary health service provide; not only do the patients benefit but so do the practice staff who learn more about the role of a social worker, as well as referral pathways. Providing the opportunity of placement learning experiences in the GP setting can equip students with specialized skills and knowledge in the field of primary health provision. This would value-add to their existing social work knowledge and skills repertoire and enable this cohort to become work-ready graduates in the field of primary health provision. Importantly, field education is the opportunity for social work students ‘ … to make sense of what it means to be a social worker by developing their professional identities and practice frameworks … suggesting knowledge can and should be iteratively acquired and actively applied during the formative period’ (Rollins et al., Citation2021, pp. 59–60).

The research discussed in this paper involved developing a curriculum for field education in general practice settings. As this is a new area of practice for social work field education, it was important to develop a guide for the social work placements so that students are prepared for the new placement setting. Equipping students with an understanding of the role of social work in health, general knowledge of health conditions and working with patients, as well as understanding GPs and other allied health staff was essential (Zuchowski et al., Citation2023). In this article, we present the method of developing the curriculum for social work GP field education and present an overview of the curriculum components.

Method

This project was made possible through funding by the North Queensland Primary Health Network [NQPHN]. The NQPHN (Citationn.d.,) 2019–2022Health Needs Assessment identified fragmented service systems within the region as a concern, resulting in poor coordination of care. In particular, weak links were identified between hospitals, GPs, mental health services, alcohol, and other drug services, and further related sectors (e.g. corrections, housing, social support, employment support). A funding application by the first author resulted in 15 months funding to establish a reference group and with their guidance and support develop a curriculum for social work students in GP practices. Further aspects of the project that are not reported on here, involved trialing six social work student GP placements, evaluating these, and developing a sustainability plan.

The aim of the research reported on here was to develop a field education placement curriculum for social work student placements in GP clinics in North Queensland. The objectives were to develop modules, material, and processes for social work student placements in primary health care. The purpose of the curriculum is to enable GP practices to take on social work students on their 500-h placement, internally supervised by a task supervisor and externally supervised by a social work supervisor. Students could be either in their first or second placement term, in either the Bachelor of Social Work or the Master of Social Work (Professionally Qualifying) degree. Ethics approval for this study was sought from the James Cook University Human Ethics committee and granted, approval number H8532.

The aim of the data collection was to present, inform, review, and evaluate the GP placement curriculum design. Data collection involved feedback gained from reference group meetings and two surveys of key stakeholders. The reference group contributions were a critical factor in the project planning and development of material, evaluation, and review of the project (Pyett, Citation2003). A participatory action research approach informed this process, involving the development of the curriculum with the active involvement of the reference group as outlined below (Alston & Bowles, Citation2018). The reference group concurrently operated as a focus group to raise and consider key elements, discuss, contribute to, and authenticate the GP placement curriculum. Purposive sampling was used to invite key stakeholders to be part of the reference group (Neuman, Citation2014). Eligibility criteria to join the reference group included social workers and social work students with experience in health settings, allied health practitioners, GPs, practice managers, or other staff involved in GP clinics or medical education experts. Potential reference group members were provided with a brief overview of the project, information about the format and timing of the reference group meeting. Reference group members had the option of attending group or one-on-one meetings. Initially, 17 members agreed to join the reference group, including six social workers, four social work students, three GPs, three Indigenous allied health professionals, and one allied health professional connected to GP training. The social workers had varied experiences as social workers in Queensland Health, in private practice, health-care services and in GP settings.

Three reference group meetings and 12 individual meetings with reference group members and other key stakeholders took place prior to inform the development of the curriculum. In the first reference group meeting an overview of the project, the timeline, and the social work field education context was provided. The feedback from the reference group members was regarding: 1. what students, practice staff and field educators might do in the 14 weeks of the placement to make it an effective placement experience and valuable to the practice and patient care; 2. What orientation/preparation do students need and how this might be delivered; and 3. What supports are needed for the entire placement and how this might be delivered?. Findings from a systematic literature about social work in GP practices (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review) were presented and key ideas explored. Interprofessional training and education for Students; Electronic Record Management; Referral Processes between GPs and Students and Managing potential space limitations were discussed . Ideas gained from the reference group members included the students developing patient resources for individual clinics, students learning about the medical terminology, the usefulness of case-based discussions, integrating training in the curriculum, i.e. courses in motivational interviewing, case discussion, or on National Disability Insurance Scheme [NDIS] or on My Aged Care, collaborating on resources and developing resources for students and clinic staff. Students understanding their scope of practice in a new field and educating other health professionals about this work was an anticipated challenge. Reference group members brainstormed some of the potential tasks a student may undertake on placement and identified that clinic nurses or practice managers would likely be the task supervisor for students due to pressures on GPs time. It was agreed that clinic staff would need to be included in the curriculum due to the uniqueness of student placement. The differences between social work and other medical placements were highlighted with social work full-time placements for 14 weeks suggested as both an opportunity and challenge for clinical resources.

The information gained was used to explore further information and areas for the curriculum design to develop a draft curriculum. The suggested curriculum was presented to the reference group at the second meeting. Feedback centred around the value of a student placement project, organizational issues (such as the business of clinics, pressure on resources such as computers and space, orientation sessions and confidentiality checklists), varied demographics of the clinics, students developing confidence for the fast paced context of clinics, learning to set limits as there was so much to do and to advocate for their own profession, interprofessional learning, and potential topics to cover in the curriculum (i.e. Medicare, NDIS, and aged care). Feedback gained was used to further work on and fine-tune the curriculum. The final draft curriculum design, including modules and information for students, practices, and field educators was presented to the reference group members at the third reference group meeting.

Two surveys were applied after a draft curriculum was developed based on the literature review and the explorations with the reference group. The sampling strategy for this survey distribution was based around the convenience of a small, networked community of practice and snow-balling. The first anonymous Qualtrics survey was sent to 19 stakeholders, including a student, task supervisors, field educators, GP’s, other health professionals and reference group members. The response rate was 52% with ten respondents completing the first survey. The first survey was administered before the curriculum was applied with students and included questions that reviewed the usefulness of and suggestions for improvement for the three curriculums components and resources that had been developed at that point of time: Part 1- Information about ‘The General Practice Clinic’; Part 2 ‘Getting Started in the Clinic’, and Part 3 ‘Social Work Practice’.

The second survey was administered after the pilot placement were completed. It explored the usefulness of the curriculum, what respondents valued in the curriculum and suggestions for improvement. It was sent to 29 stakeholders, placement students, task supervisors, field educators, GP’s, other health professionals, mentors and reference group members. 16 responses were received, which resulted in an initial response rate of 55%. Of the 10 respondents in the first survey and the 16 respondents of the second survey, three in each group indicated that they did not view or used the GP student preparation modules and thus were excluded from responding to questions about the modules.

Curriculum development framework

Social work field education is undertaken in the multi-dimensional, layered and often fluid social work practice context and is characterized by the often-transient nature of knowing and not knowing and the need to learn to access and utilize different forms of knowledge (Rollins et al., Citation2021). Field education curriculum thus includes ‘teaching students to practise from a knowledge paradigm’, learning how to access knowledge, new ways of knowing and learning and being able to operate at times in not knowing situations, (Rollins et al., Citation2021, p. 61). The engagement with and feedback from the reference group and individual stakeholders further highlighted that the GP context within Australia is a unique placement context for students, underpinned by a business model rather than typical not for profit or government service model. This meant specific training was warranted to equip students for the complexity of this setting. One of the key components of the curriculum was the development of a training program for students to orient them to the placement.

A curriculum design grid (see Appendix A) was used to develop the placement preparation modules and program and to map GP placement student learning outcomes to social work field education learning objectives. The grid highlights the use of the placement subject learning outcomes, based on the 2013 Social Work Practice Standards (AASW, Citation2013), and specific GP placement curriculum learning outcomes in the development of the modules (see ).

Table 1. GP curriculum learning outcomes.

The curriculum learning outcomes were developed based on a systematic literature review exploring social work practice in primary health settings (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review), reference group insights and project worker discussions. The development of the learning outcomes incorporated principles of the Bloom’s Taxonomy (Armstrong, Citation2010). Each GP placement learning outcome was aligned to the relevant placement subject outcomes, which themselves are based on the Social Work Practice Standards (AASW, Citation2013). The curriculum design grid was used to develop the four placement modules, including to plan the sections, topics, the key teaching and learning activities and assessment, the timeframe of when specific learning activities would be undertaken, and the alignment with the GP placement learning outcomes (see appendix A).

As prior research and feedback from the reference group highlighted that key considerations for the project would be time and resource pressures in the GP clinic on staff, and the ambiguity of social work resulting in health professionals’ misunderstanding of social work practice, it became evident that the curriculum needed to prepare all parties involved in the student placements. Therefore, resources were developed for task supervisors, likely to be practice managers and nurses, for them to be able to support the student learning on placement.

Results

The first survey responses can be summarized by the following comment made by a respondent ‘An insightful and education curriculum for all stakeholders’. Usefulness of the curriculum was described in terms of the overall beneficial orientation to the GP setting, the practice resources, such as case studies, record keeping, supports, flagging opportunities (see example Appendix B) and directing students to relevant websites, and the breakdown of roles. Comments focused on the quality of the work:

Amazing work. Well put together in a clear manner with fantastic additional resources.

Feedback to extend the curriculum was about including content about self-care, face-to-face contact with professionals working in this area and ‘Exploring with students how to develop and building relationships in a GP setting—due to the busy nature of the clinics. Brainstorming ideas or potential role plays with staff’. Respondents rated all resources and strategies developed as useful or very useful. These included a 6-week orientation check list, case-based group supervision, out of clinic professional development tutorials, the clinic guide for task supervisors, the clinic guide for the field educators/liaison person, the task suggestions for students in the clinic and out of clinic day.

Second survey responses were also very positive and particularly highlighted that the curriculum, was useful, concise, and informative for both students ‘I found it very helpful and thorough without being onerous’ and other key stakeholders ‘It was useful to know what work the students had done before going into the placement’.

Feedback for improvement included aspects that could be further developed in the curriculum material, such as more medical information, but also about needing more preparation for the GP clinics. One comment highlighted, for example:

I felt that the orientation and preparation material for the students was satisfactory, other than needing more information regarding medical terms and procedures to understand the doctors and nurses better. I feel the GP offices needed more preparation than the students, though, as some offices had no idea how to utilize our skills and this resulted in placement time wasted trying to figure out how to coordinate our jobs in the GP office.

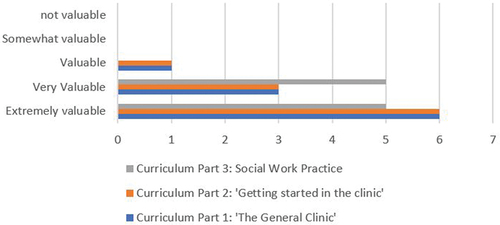

highlights that respondents particularly valued, Curriculum Part 1 and 2, modules that explored the GP clinic and getting started in the clinic.

Comments about what was particularly valuable in the modules focused on clarifying expectations (n = 4), learning about the clinic, the setting and Medicare (n = 4), and information and knowledge in general (n = 2).

The modules were useful on helping me understand some of the expectations in the GP setting and what was being asked of me.

It was valuable in teaching about the basics of gp practices, medicare, medicalunderstandings and values, and how gp practices operated

Comments for improvement included more engagement and time with the material (n = 3) more details of GP practices, medical information, and social work in these settings (n = 3), and ‘nothing/excellent/detailed’ (n = 3)

I think there should be more information about social workers in medical settings and what they can participate in

More information regarding medical terminology and even more information regarding what assessments the doctors use as well as info given to clients to understand how to better help them once the GP was finished.

The curriculum

The GP social work field education curriculum developed includes placement preparation modules for students, a progressive induction, an out of clinic education day, placement resources, and information GP Clinic guides for liaison people, field educators and for the GP clinic-based task supervisors.

Placement preparation modules and progressive induction

The final GP placement modules are structured around four placement preparation modules specific to the GP setting that students complete in their first four weeks of their placement. In the pilot period of the project, there were three modules that were completed by students over a two-week period (see ). However, social work education is an iterative process and learning from students, the reference group and the surveys have resulted in modules being slightly extended and spread over four weeks and additional days. The final modules are focused on exploring and understanding ‘The General Practice Clinic’, ‘Getting Started at the Clinic’, ‘The Social Work Role’ and a final module on developing ‘The Clinic project’. Modules are delivered through a combination of self-paced and out-of-clinic education. Complementing the delivery of the training is a progressive four-week induction into the GP clinic.

Table 2. GP placement timetable.

The progressive induction ensures that students are well prepared for the specific placement setting, can familiarize themselves with the required learning content and introduce themselves to the clinic and explore the context of the setting. Moreover, it allows the general practice to ease into the new placements. Anecdotal feedback highlighted that social work placements are intense and lengthy in comparison to other health disciplines such as nursing or undergraduate medicine in general practice. This meant that some practice managers were hesitant to consider supporting social work student placements due to the time students would be onsite.

Module 1: The General Practice Clinic

Literature about social work practice in GP practices clearly highlighted that the general practice context brought unique challenges, organizational barriers being one key theme (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review). Providing an understanding of the clinic context and introducing students to the models and processes that dominate general practice in Australia was important preparation.

This module introduces the GP clinic context including Medicare structures, Aboriginal Controlled Community Health Organsations (ACCHO’s), clinic processes such as care plans and patient demographics that are frequently found in the GP setting such as older persons. It outlines the roles of key members of the professional team including practice nurses and practice managers and introduced important attributes for working in a multi-disciplinary team. Importantly, the biomedical model is presented as well as various social work perspectives including social determinants of health and social prescribing. Cross cultural considerations, social and emotional wellbeing and valuing the lived experience. Students are guided to begin to articulate social work to their colleagues, knowing that this has been a challenge for social work in primary health elsewhere (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013).

A first six-week induction checklist (Appendix C) was developed for both students and task supervisors to support and guide the induction of the student into the GP clinic. Students are introduced to this resource in Module 1 and prompted to research their particular GP clinics in order to complete the first section of this resource. Task supervisors are provided this in their guide, and both are encouraged to use this as a guide for the placement induction.

Module 2: Getting Started at the Clinic

Module two provides a framework for getting started in GP clinics. It explores the first 6 weeks of the placement, placement supports, the various stakeholders of the placement, record keeping, hygiene and safety in a medical environment and self-care. Importantly, this module outlines supports for the student both within the community and on placement and encourages the student to network with other organizations who hold expertise in particular practice areas such as mental health or family wellbeing. Local community directories are introduced, and students are prompted to start engaging with other community resources.

Internationally, social work in primary health care is embedded in a variety of ways; social workers can undertake diverse interventions in response to the local context and patients (Zuchowski & McLennan, Citationunder review). The dynamic, social wellbeing focus and diversity of social work practice is an opportunity that can significantly enhance patient care in a variety of settings. Localized context is important to GP social work placements, and reference group members brainstormed the ways a student may both contribute to and learn in the Australian general practice setting in North Queensland. A resource was developed with suggestions for students, clinic staff and prospective placement settings, highlighting how a student may fit within the general practice (see Appendix B). This resource is introduced in module two and students are asked to assess their confidence against some of the task suggestions and discuss these with their support team. It is emphasized that these are merely suggestions and being responsive and adaptable to a setting is important.

Module 3: The Social Work Role

The foci of module three are the process and tools of social work student practice in primary health. It includes examples of assessment tools utilized and relevant for general practice, theories to support interventions, and management of safety and risk in the GP setting. There are clearly communicated processes for the student should they encounter an issue affecting patient safety, as well as pathways for further training. This component of the curriculum is compulsory for students, prior to seeing or being referred patients. Module three supports students to find their place within the GP setting and to communicate this to colleagues.

Module 4: GP clinic projects

It was identified that it would be useful for each GP placement student to complete a project for the clinic to enhance their professional learning and concurrently support the needs of the clinic. Placements with project and research opportunities facilitate students’ growth and learning about research skills and develop their confidence, expertise and other professional practice skills (Zuchowski et al., Citation2020). For agencies, such projects can include improved service delivery, collaboration and production of knowledge and policy development (Zuchowski et al., Citation2020). To develop a project for the GP placement, students are asked to understand the demographics of patients, strengths and needs of the clinic before deciding upon their project. Prompts are provided in Module 4 for students to undertake this research. The project is negotiated with the task supervisor and/or practice manager to ensure that the project is suitable for the clinic and then integrated into the placement learning plan. It is an opportunity for students to engage in research and to leave something meaningful for the clinic. Examples are:

Developing a resource on a particular community issue/challenge.

Finding information for the clinic on community pathways or building a connection with a local service.

Auditing the clinics engagement with a particular marginalized group such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

Running a one-off session for patients

Anecdotal feedback from pilot program students indicated that thinking about the project in the first few weeks of placement distracted some students from getting to know the clinic and additionally caused unintended anxiety. Subsequently, the project module is improved to be a stand-alone module introduced in week four once the students have some sense of the GP setting and have settled into the new placement.

Resources for students

A substantial consideration in the development of the modules was the awareness of students’ learning beyond the preparation phase. Consequently, the learning content was built to include a variety of valuable online resources that students could refer to throughout their placement and into their professional career. The modules include prompts for students to enroll in additional training that can be completed within their placement. For example, Domestic Violence-alert [DV-Alert] online training and professional development for elder abuse through Older Persona Advocacy Network [OPAN]. The four modules over weeks 1–4 provide scaffolding to assist the student integration into a novel setting and set them up for the best chance of placement success. It was identified early though that more would be required over the following 10 weeks to enrich the learning experience and provide additional support.

Professional development/out of clinic education day

Following the progressive induction, from week 5, students undertake their placement four days located within the clinic and 1 day out of the clinic. The day out of the clinic is focused on professional development and includes peer group supervision sessions, tutorial type presentations and agency visits. Peer group supervision recognizes the additional growth that can be achieved from observing and learning from peers, engaging with a diversity of perspectives and developing supportive relationships (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). The peer supervision sessions were run as case-based supervision to allow students to engage in structured exercises and group discussions relevant to their practice area (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). Generally, students will be placed in GP clinics without practising social workers, and thus case-based group supervision provides an additional opportunity to experience a social worker facilitating, supporting, and guiding a group of students. This helps ensure actions on placement are accountable to the profession and do no harm to patients and their families, but also allow students to observe social work practice.

Case-based group supervision requires students to provide an example of a deidentified patient they have been working with to the group supervision. The social work supervisor facilitates a discussion about this patient and assists students to think about their social work values, processes, theories, and methods that apply to the patient scenario. The aim is for students to be able to articulate social work practice and gain confidence about how they may apply skills and knowledge in future patient scenarios.

The day out of the clinic aims at providing further professional development opportunities such as tutorials delivered by JCU social work educators and to partner with community organisations/health workers. This could include working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, Trauma-Informed Practice, working with older persons, grief and loss, NDIS etc. The time out of clinic is aimed at facilitating students to engage in personal research/library time, complete journals, or organize agency visits that are relevant for their placement. Students could jointly arrange visits as a group or individually organize these.

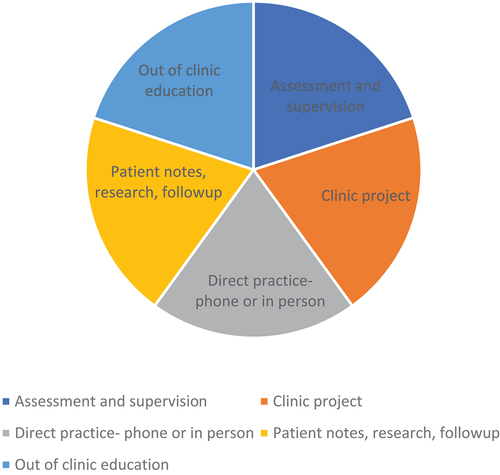

It is important for students, task supervisors, field educators, and the liaison person to understand the range of GP placement learning activities, that include but are not limited to direct practice with patients, that would take up the students’ time during placement as it is an academic subject (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). shows the five types of core learning activities that students are engaged with in these placements. Students spend time face to face, by phone or zoom with patients. Due to the broad scope of work in general practice, students require time to follow up and research, network, and refer after seeing a patient. Students need time to liaise with the clinic staff to plan, research and implement a project for the GP clinic. As outlined above, it is important that students spend one day away from the clinic engaged in peer support and professional development. The final time consideration is to cover assessment obligations and external supervision.

Clinic guides for liaison people, field educators, and task supervisors

The conceptualization of social work student time in a clinic is shared with clinic task supervisors and other support staff to optimize the understanding of a student’s experience. Social work is often misunderstood and/or ‘a little fuzzy’ (Döbl et al., Citation2015), requiring social work leaders and educators to support other disciplines to understand how they work. The finalized curriculum includes GP clinic guides for clinic-based task supervisors as well as university liaison staff and external supervisors. The guides provide an overview of the background, literature relevant to social work in primary health care, information about support roles and working collaboratively for placement success. Moreover, it gives an overview of the clinical placement curriculum, the preplacement training, and progressive induction, the first six-week induction checklist, and details of the out of clinic education/professional development day as well as GP project requirements. The task supervisor guide additionally outlines what is social work, the potential benefits of social work in primary health settings, an overview of social work education and details of the student field education requirements for the first and second placement.

Discussion

It is important for social work placements to be valuable learning experiences, assisting students to develop their professional identity and confidence (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018). Placements therefore needed to be an opportunity to learn how to learn, how to access relevant information and how to operate at times in ‘not knowing’ situations (Rollins et al., Citation2021, p. 61). The social work student placement curriculum for primary health settings works to develop important knowledge and contexts for students, but also prepare them to seek and find resources and support in those moments of not knowing and uncertainty. Importantly, the curriculum set up the expectations and ideas for continued support and guidance throughout the placement. Thus, the curriculum needs to be considered in the context of the whole placement curriculum set-up, including peer support, case-based supervision and out of clinic days, for example. Learning from peers and supervisors, engaging with a diversity of perspectives and developing supportive relationships are important aspects of field education (Cleak & Wilson, Citation2018).

For social work students to be able to undertake placements in GP settings, they need to be able to understand and articulate the role of social work in primary health care. Social workers need to have solid knowledge about social work theories, skills and processes, and communication and collaboration skills, but also have an understanding of medical conditions and interventions in order to work in integrated health care (Held et al., Citation2019). Feedback from survey participants highlighted that while the curriculum was comprehensive and detailed, some would have liked more information about GP clinics and the social work role. The extended curriculum offers both, the opportunity to develop a beginning understanding of health care and the ability to articulate the social work role, this is particularly important for social work to evidence its value and place in primary health (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013). It is an opportunity for social work students to have a better understanding of GP practices. This could be through medical, social work and other allied health students working collaboratively together and learning from each other’s professions.

The developed curriculum for social work placements in primary health care provides students the opportunity to consider the clinic context, the role of social work in primary health care and getting started in GP settings. Role clarification is important early in any placement, particularly those with external supervision (Egan et al., Citation2021). The developed placement resources provide students the opportunity to explore the GP practice settings, the roles of various stakeholders and their own role. This is as important as the provision of information and role clarification for task supervisors, as they can have a limited understanding of social work roles and values (Cleak et al., Citation2022). While the curriculum modules are an important preparation for practice, the ability to go beyond exploring this in theory and through theoretical instruction is important. Thus, the practice application in GP settings could help strengthen the understanding of roles and values and the skills of articulating the social work role.

The feedback and guidance of a range of interdisciplinary stakeholders was invaluable in developing resources for interdisciplinary work. The contributions of the reference group members were a critical factor in the project planning and the development of material, and the evaluation, and review of the project (Pyett, Citation2003). Using the face-to-face feedback gained in reference group meetings and individual discussion, as well as the survey data facilitated direction, clarity, and improvement to the curriculum design.

Conclusion

The developed curriculum is a valuable tool for introducing and inducting students into a GP placement setting and as a meaningful reference guide throughout the entirety of placement. The fundamental importance of students being able to articulate the role of social work and what resources, tools, and skills social workers bring to GP settings is noted throughout this project. This goes hand in hand with a student’s pre- and on-placement learning, in which they are required to develop an understanding of healthcare issues, relevant to their placement GP practice. The student’s ability to reconcile the social work role with the unique needs of the placement clinic needs to be considered for an extended curriculum in future.

Acknowledgment

This research has been funded by ‘Northern Queensland Primary Health Network’ (NQPHN). We would also like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Martin Hazelwood, Lisa Swanton, and Toni Weller to the reference group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ines Zuchowski

Dr Ines Zuchowski, PhD is a qualified social worker teaching and researching as a senior lecturer in social work and human services at James Cook University, Australia. She has intensivly publish in social work education, wiht a spcific focus on field education. Her current research interests are focused on field education, child protection and health.

Simoane McLennan

Simoane McLennan is a social worker who has worked in a variety of human services settings for 15 years including homelessness support, mental health, family support and medical social work. Over the past few years she has gained an interest in social work education and has worked with students as an educator teaching a variety of subjects and providing placement support. Simoane is passionate about excellent and innovative social work practice and was the project worker for the GP student placements, delivering out of clinic education sessions and facilitating group supervision.

Kat Buchta

Kat Buchta is a qualified social worker and holds a Bachelors in Social Work from James Cook University, Australia. Kat is currently working in Women's Services, primarily providing homelessness and domestic violence support and she previously worked in a coordinated medical care program at a Neuropsychiatric Institute in The United States. Kat is undertaking a Masters by research, looking into social workers' experiences of domestic violence.

Katrina Cordes

Katrina cordes is a Team Leader in the General Practice Training Program at James Cook University.

Tarun Sen Gupta

Tarun Sen Gupta (FRACGP, FACRRM, PhD) is Professor of Health Professional Education and Head of the Townsville Clinical School at James Cook University. He has a background in general practice and medical education, and has previously worked in remote solo medical practice. His interests include rural medicine, community-based education, faculty development and assessment.

Cassandra Ladesma

Cassandra Ladesma ais a social work graduate from James Cook University.

Rebecca Lee

Rebecca Lee - BSW(Hons) 2001, MBA, 2010. Both degrees completed through James Cook University. Rebecca has an strong interest in Mental Health and currently works at James Cook University in the Student Led Clinics.

Lawrie McArthur

Lawrie Mc Arthur (MBBS DRACOG FRACGP FACRRM PhD) is an adjunct associate Professor at James Cook University.

References

- AASW. (2013). AASW practice standards. https://www.aasw.asn.au/practitioner-resources/practice-standards

- AASW. (2015). Scope of social work practice. Social work in health. Australian Association of Social Workers.

- AASW. (2020). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards [ASWEAS]. https://www.aasw.asn.au/practitioner-resources/related-documents

- AIHW. (2016). Primary health care. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/primary-health-care-in-australia/contents/about-primary-health-care

- Alston, M., & Bowles, W. (2018). Research for social workers: An introduction to methods. Allen &Unwin.

- Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved July 6, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

- Ashcroft, R., McMillan, C., Ambrose-Miller, W., McKee, R., & Brown, J. B. (2018). The emerging role of social work in primary health care: A survey of social workers in Ontario family health teams. Health & Social Work, 43(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hly003

- Bako, A. T., Walter McCabe, H., Kasthurirathne, S. N., Halverson, P. K., & Vest, J. R. (2021). Reasons for social work referrals in an urban safety-net population: A natural language processing and market basket analysis approach. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(3), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1817834

- Campbell, R., Dworkin, E., & Cabral, G. (2009). An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(3), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334456

- Cleak, H., & Wilson, J. (2018). Making the most of field placement (4th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Cleak, H., Zuchowski, I., & Mark Cleaver, M. (2022). On a wing and a prayer! An exploration of students’ experiences of external supervision. British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa230

- Coid, J. W., Ullrich, S., Kallis, C., Freestone, M., Gonzalez, R., Bui, L., Yang, M. (2016). Improving risk management for violence in mental health services: A multimethods approach. Programme grants for applied research. National Institute for Health Research. https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar04160

- College of Social Work. Royal College of General Practitioners. (2014, October). GPs and social workers: Partners for better care delivering health and social care integration together. A report by the College of Social Work and the Royal College of General Practitioners. www.rcgp.org.uk/news/2014/october/~/media/Files/CIRC/Carers/Partners-for-Better-Care-2014.ashx.

- de Saxe Zerden, L., Lombardi, B. M., Fraser, M. W., Jones, A., & Rico, Y. G. (2018). Social work: Integral to interprofessional education and integrated practice. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 10, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2017.12.011

- Döbl, S., Huggard, P., & Beddoe, L. (2015). A hidden jewel: Social work in primary health care practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Primary Health Care, 7(4), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC15333

- Egan, R., David, C., & Williams, J. (2021). An off-site supervision model of field education practice: Innovating while remaining rigorous in a shifting field education context. Australian Social Work, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1898004

- Foster, J. (2017). Thoughts on GPs and social workers. British Journal of General Practice, 67(662), 416. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X692441

- Hartung, M., & Schneider, N. (2016). Sozialarbeit und hausärztliche Versorgung: Eine Literaturübersicht. Zeitung Allgemeine Medizin (Z Allg Med), 92(9), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.3238/zfa.2016.0363–0366

- Held, M. L., Black, D. R., Chaffin, K. M., Mallory, K. C., Milam Diehl, A., & Cummings, S. (2019). Training the future workforce: Social workers in integrated health care settings. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1526728

- Hudson, A. (2014). Social workers and Gps will be at the heat of bringing integration to life. The Guardian. Retrieved November 24, 2014, from https://www.theguardian.com/social-care-network/2014/nov/24/health-and-social-care-integration

- Hwang, S. W. (2001). Homelessness and health. Canadian Medical Association Journal (Cmaj), 164(2), 229–233.

- Koziol McLain, J., Giddings, L., Rameka, M., & Fyfe, E. (2008). Intimate partner violence screening and brief intervention: Experiences of women in two New Zealand health care settings. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 53(6), 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.06.002

- Lombardi, B., de Saxe Zerden, L., & Richman, E. (2019). Where are social workers co- located with primary care physicians?. Social Work in Health Care, 58(9), 885–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2019.1659907

- Mann, C. C., Golden, J. H., Cronk, N. J., Gale, J. K., Hogan, T., & Washington, K. T. (2016). Social workers as behavioral health consultants in the primary care clinic. Health & Social Work, 41(3), 196–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw027

- Neuman, L. W. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson.

- Ní Raghallaigh, M., Allen, M., Cunniffe, R., & Quin, S. (2013). Experiences of social workers in primary care in Ireland. Social Work in Health Care, 52(10), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.834030

- NQPHN. (n.d.). Northern Queensland Primary Health Network. Health Needs Assessment 2019- 2022. https://www.nqphn.com.au/sites/default/files/2020-09/NQPHN%20Health%20Needs%20Assessment%20%28HNA%29%202019-2022.pdf

- Pyett, P. M. (2003). Validation of qualitative research in the “real world”. Qualitative Health Research, 13(8), 1170–1179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303255686

- Rollins, W., Higgins, M., & Chee, P. (2021). Pedagogies and social work field education. In R. Egan, N. Hill, & W. Rollins (Eds.), Challenges, opportunities and innovations in social work field education Chapter 5 (pp. 57–70). Routledge.

- Safren, S. A., O’Cleirigh, C. M., Skeer, M., Elsesser, S. A., & Mayer, K. H. (2013). Project enhance: A randomized controlled trial of an individualized HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men conducted in a primary care setting. Health Psychology, 32(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028581

- Swerissen, H., Stephen Duckett, S., & Moran, G. (2018). Mapping primary care in Australia, Grattan Institute.

- Zuchowski, I., Cleak, H., Nickson, A., & Spencer, A. (2019). A national survey of Australian social work field education programs: Innovation with limited capacity. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1511740

- Zuchowski, I., Heyeres, M., & Tsey, K. (2020). Students in research placements as part of professional degrees: A systematic review. Australian Social Work, 73(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1649439

- Zuchowski, I., & McLennan, S. (under review). A systematic review of social work in general practice: Opportunities and challenges.

- Zuchowski, I., McLennan, S., & Sen Gupta, T. (2023). Evaluation of social work student placements in general practice. British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac244