ABSTRACT

This research explores the use of simulation technology in supporting and preparing social work students (n = 336) for core professional skills needed for practice. This study utilized a randomized experimental design using a 3 × 3 between-subjects design to assess the impact of the type of simulation (e.g. traditional written case studies, video-based simulations, and live actor simulations) and type of scenario (e.g. family/domestic violence, suicide/mental health and hospital/medical) on social work student’s ability to undertake a psychosocial assessment. Results showed that students developed more comprehensive psychosocial assessments when presented with video simulations compared to traditional methods, using actors or written case studies. This research builds evidence for social work to embrace the use of simulation to develop these skills for students in a practice setting that removes not only the fear of doing harm but also the real possibility of harm in complex scenarios. Social work field education is under increasing pressure to meet professional standards, especially with the impact of the COVID pandemic. Thus, the profession must consider alternatives for training students including utilizing technology. While many other professional disciplines incorporated the use of simulation in training, social work has been slow to embrace this trend while favoring traditional teaching methods.

Introduction

Social workers seek to provide a more socially just and inclusive society, working with the most vulnerable people in diverse roles within the community. To qualify as a social worker in Australia, there are two educational pathways, a four-year bachelor’s degree or a two-year master’s qualifying degree. Both degrees are subject to the same accreditation guidelines of the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) and requires students to undertake a minimum of 1000 hours of field education within two distinctly different placement settings (AASW, Citation2020). These accreditation standards define field education as the avenue for students to apply learning from the classroom to a professional practice setting and provide students with an opportunity to develop their professional identity, integrity and practice frameworks (AASW, Citation2020). The AASW (Citation2020) outlines that,

Field education is a distinctive pedagogy for social work education. It enables students to integrate classroom learning with professional practice so that students notice and refine their ways of thinking, doing and being. Field education socialises students into the profession through immersion in real practice context, while allowing a constructive and reciprocal learning space to develop. Students make sense of what it means to be a social worker by developing their professional identity, integrity and practice framework (p.9).

Bogo (Citation2015) argued that field education is the most important element of social work education in preparing competent, ethical and effective social workers. Many social work students embark upon their initial field placement without having had an opportunity to develop skills within an authentic practice scenario, resulting in the potential risk of students being inadequately prepared for the task (Jefferies et al., Citation2021b). Given the limited direct practice social work field placement opportunities, there has been a significant increase in placements utilizing external supervision simply to provide placement options. However, this strategy provides students with limited opportunities to observe and be observed by a qualified social worker. Consequently, students are deprived of receiving professional supports and most importantly the opportunity for valuable feedback in applying skills in direct client contact (Bogo, Citation2015; Cleak & Zuchowski, Citation2019; Cleak et al., Citation2020; Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020; Lee & Fortune, Citation2013; Wilson & Flanagan, Citation2021). Currently, the opportunities provided to students within field education vary greatly depending on the placement setting and experience in complex direct practice cases is often limited or simply not possible (Zuchowski et al., Citation2014). Jefferies et al. (Citation2021a) note that students may never have the opportunity to participate in complex cases like completing a suicidality assessment, a family and domestic violence assessment or simply engaging with diverse clients.

When designing a learning experience for students, consideration of student needs including their capacity to store information is essential. Cognitive load theory, developed by Sweller (Citation1988), proposes that there is a limited capacity on working memory which impacts how learning occurs and instructional methods should avoid overloading learners with additional activities that do not directly contribute to the learning. This theory has been applied to understand how students can best engage with a learning experience and then store the information, particularly concerning learning with simulation (Bligh & Bleakley, Citation2006; Nestel et al., Citation2014; Reedy, Citation2015). Reedy (Citation2015) states people are limited with how much information they can process simultaneously within their working memory, which impacts their ability to store information. In applying cognitive load theory to this research, an understanding of the three categories of cognitive load impacting on student learning was required. The first load is intrinsic load which refers to the complexity of the instruction and can overload student cognition. The second load is extraneous load which is caused by elements that don’t appear to contribute to students learning and can be reduced with good instructional design. The third load is germane load which support students’ ability to understand new concepts by utilizing existing knowledge and skills already stored in long term memory and can support the understanding of new knowledge by freeing up working memory (Hawthorne et al., Citation2019).

This theoretical understanding has significant implications for the training of social work students to appropriately deal with complex case situations. When people are presented with new information, there comes a point at which the cognitive load hits overload, and learning is disrupted. People can only deal with new knowledge for a few seconds, according to Van Merrienboer and Sweller (Citation2010), and without further practice, all information will be forgotten within about 20 seconds. As a result, new material must be repeated or practiced in order to be stored in long-term memory, and any new information must be taken in smaller, less complex chunks. Empirical research backs up the idea that giving students clear instructions and assistance, followed by an opportunity to practice and receive feedback, makes teaching new information more effective (Clark et al., Citation2012). The use of CLT to student training guarantees that the student has the opportunity to learn and practise managing working memory overloads in a safe environment (Martin, Citation2016). CLT has been used in a variety of educational settings, particularly in the health sciences (Fraser, Ayres & Sweller, Citation2015; Young et al., Citation2016). Due to the demands of training required before field education placements and the complexity of challenges faced by the populations served by social workers, particularly highly emotive contexts, this model holds potential for social work education.

Historically, the authentic learning requirements of social work education have been mostly left to the student field placement component. This method lacks a scaffolded approach and relies mainly on learning acquired from written case studies in class, rather than a genuine environment that replicates real-world exposure to complicated issues. According to research, students should begin by learning simple tasks with little variability, then progress to more difficult and complicated tasks as they gain expertise (Likourezos et al., Citation2019). As the complexity of learning increases, this scaffolded approach must include a variety of environmental factors not typically covered in traditional course work, such as individual, organizational policies and procedures, emotional factors for clients and practitioners, and organizational staff cultures. The conventional dependence on written case study learning in social work education must be replaced with carefully scaffolded learning that includes an authentic setting that addresses CLT and its impact on student cognition as part of the learning process.

Thus, in applying cognitive load theory, it would be beneficial to train social work students to deal with complex situations in the protected environment of a simulation or lab setting before they are exposed to these in real-life settings; therefore, reducing their intrinsic and extraneous load on cognition. The use of simulation in this study was designed utilizing cognitive load theory. Nimmagadda and Murphy (Citation2014) defined simulation as ‘a pedagogy using a real-world problem in a realistic environment to promote critical thinking, problem-solving and learning’ (p. 540). The use of simulation in complex client situations can simplify the case context by removing unnecessary information or extraneous load on cognition caused by fear of doing harm or failing; and thus, can also increase and improve students’ learning and the process of information. On the contrary, while dealing with a complex client in real-life, the situation is generally compounded by the setting, other people, and external environmental factors. When using CLT in the learning environment, it is important to think about the scaffolding of learning and the early reduction of elements related to the practice situation or abilities being taught so that working memory can be maximized before overloading. This can be accomplished by controlling the intrinsic load in the simulation activity through effective instructional sequencing, minimizing the extraneous load through excellent instructional design and scaffolding, and increasing the germane load or demands on working memory.

The global pandemic has created a necessary shift in social work education that has resulted in a new reliance on technology (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2020). Studies on simulation and social work education is under-researched in Australia and those which have been conducted utilize relatively small sample size without control groups (Jefferies et al., Citation2021b). Thus, there was a need for the exploration of different types of authentic technology-based simulation to be explored and tested to ensure the development of ethical and safe social work practice within the current challenges, including the COVID pandemic (Citation2021b).

The AASW (Citation2020) accreditation standards outline requirements students must comply with and the graduate attributes they need to meet. The graduate attributes developed by the professional body require students to have an ability to review, critically analyze and synthesize knowledge and values and apply reflective thinking skills to inform practice as well as to apply social work knowledge and interventions to respond effectively in meeting the needs of individuals, groups and communities (AASW, Citation2020). Academics are challenged with developing courses and assessments to ensure students can demonstrate these professional graduate attributes. Clearly understanding the skills and attributes is a further challenge for academics to ensure a student can demonstrate competencies within field education before graduating (Bogo et al., Citation2007). It is therefore imperative these limitations are addressed to minimize potential risks to the vulnerable clients which both students and graduate social workers without such skills, can pose in professional practice.

There has been an increasing need for field education units to employ ‘band-aid’ solutions to address the growth in student numbers and more recently the COVID pandemic. Solutions included a range of innovative approaches such as developing ‘student units’ whereby multiple students are allocated to an agency with shared opportunities for skill development and supervision (Cleak & Zuchowski, Citation2019) and supervised, self-directed student placements (Archer-Kuhn et al., Citation2022). Another strategy to support placement opportunities was the use of non-traditional social work settings for field placements such as in community legal services, pet refuge or in private practice settings. These strategies are resource-intensive, more expensive and require larger support from field education teams in scoping and supporting learning opportunities. Such non-traditional placement settings are often more complex for students to navigate and lack opportunities for traditional skill development. These challenges require universities to invest in developing evidence-based activities to ensure that social work students are meeting the graduate attributes and engaging in adequate skills training through exposure to assessments working in complex direct practice situations (Zuchowski et al., Citation2019).

More recently social work has shown success in utilizing simulation (Asakura et al., Citation2020) like nursing, occupational therapy and health disciplines (Bø et al., Citation2021; Cameron & McColl, Citation2015; Gibbs et al., Citation2017; Giles et al., Citation2014; Kacalek et al., Citation2021; van Vuuren, Citation2016). However, the current challenge for social work education is to effectively address the inclusion of simulation in the skills development of students. Simulation should not be seen as a replacement for field education but rather an important addition thus supplementing learning opportunities missing from placement experiences. Simulation as a ‘hurdle’ task prior to field placements could support student skills development and better prepare students for practice as well as support those placements in non-traditional social work settings (Jefferies et al., Citation2021b). Simulation can provide a standard or baseline for skills to address the broad diversity and limitations of placements.

Can simulation prepare students for placement?

Social work education requires methods to be identified that are reliable and effective in assessing student competence, and therefore practice assessment skills that involve simulation activities and thus may hold potential for social work (Logie et al., Citation2013). The use of simulation is vast and can include the use of actors (Asakura et al., Citation2020) or using virtual technology. Research is required to understand the impact of pre-training on field education or as an essential part of the standard field education hours. The professional responsibilities set by AASW as Practice Standards (Citation2013) require qualified social workers to practice in accordance with these and can be employed as a guide for assessment in simulation activities and thus support student development for practice. This would allow students the ability to meet learning requirements and professional practice standards in a standardized format and make certain that all students have the opportunity to meet the necessary learning requirements for social work accreditation. Ultimately, students should be adequately prepared for practice scenarios within their placement and therefore meet the requirements expected of qualified social workers. Simulation activities that meet this requirement can provide opportunities for students to develop professional practice skills without the fear of doing unnecessary harm and in a safe environment to make mistakes (Coohey et al., Citation2017). With the increased demand for field education, it is clear that not all placements will be able to afford students this type of learning opportunity, and exposure to complex cases. The key to developing students for placement and ultimately the profession may be achieved using quality simulation activities within social work education.

Research aims

Thus, the specific research questions for the current study were as follows: 1) Is there a difference between traditional written case-study learning, simulation with live actors, and video simulation in students’ ability to identify factors contributing to the development of a psychosocial assessment? 2) Is there an interactional effect between simulation type and type of scenarios in students’ ability to identify factors contributing to the development of a psychosocial assessment?

The study hypotheses were: 1) Students’ demonstration of written psychosocial assessments skills are better if they are based observation of simulated interactions (video-based simulations) or participation in interactions (live actor simulations) rather than based on written case studies. 2). Students’ ability to develop a written psychosocial assessment will be the same across simulation type and type of scenario.

Methods

Design

This study was a randomized experimental design using a 3 × 3 between-subjects design. The independent variables were the type of simulation (e.g. traditional written case studies, video-based simulations, and live actor simulations) and type of scenario (e.g. family/domestic violence, suicide/mental health, and hospital/medical). The dependent variable was participants’ competency in the skills required to develop a psychosocial assessment.

Procedures

The research was undertaken in a social work and human services program in a regional Australian university. Prior to undertaking the field placement component of the degree, students undertook pre-placement workshops to prepare them for their field experience and to assess placement readiness. The simulation activities were included as part of the pre-placement workshops for field education courses, and participants were offered the opportunity to have their data included in the study. Less than 5% of the sample did not consent to their data being included in the research. During these workshops, students participated in a simulation activity and completed a survey via Survey Monkey between July 2019 and February 2021. There were three simulation types used: traditional written case studies, video-based simulations, and live actor simulations. Type of simulation activity was randomized across the cohorts of students each semester. Each simulation type included three different simulation scenarios: family/domestic violence, suicide/mental health and hospital/medical. The simulation scenarios were randomly assigned to students within each cohort.

Participation in the simulation activity took about 30 minutes to complete, including briefing and participation. Immediately following participation in the simulation activity, students were asked to complete a survey with general questions relating to components of a psychosocial assessment based on the scenario. All data were collected anonymously, and implied consent was obtained by clicking on the survey link. Ethics approval for this study was provided by the University XXX (Ethics #XXX).

Participants

The research study included 336 participants aged between 18 and 62 years of age (M = 31, sd = 10.11), those completing a Bachelor of Social Work (n = 141, 42%), Master of Social Work (n = 169, 50%), and Bachelor of Human Services (n = 26, 8%). Fifty-nine per cent of participants were starting their first placement and 41% were embarking on their second or final placement. The sample included domestic (63%) and international (37%) students, with less than 5% of the students identified as Indigenous. A large percentage of participants reported either no prior work experience (43%) or less than 1 year of work experience (24%), and a minority of participants reported between 1–3 years (15%) or over 3 years of work experience (18%).

Measures

Type of simulation

Three simulation types were used in the study: traditional written case studies, video-based simulations, and live actor simulations. The traditional written case studies included an initial description of the scenario setting, followed by a transcript of the initial interview. For the video simulation, participants were given the same brief description of the scenario setting and then given a video clip with a role-play of the initial interview. Participants in the actor simulations were again given the same brief description of the scenario setting and then led to a room and introduced to an actor playing the role of the client in the scenario. The actor was given written and video simulations in preparation and asked not to veer from the story or give extra detail to what was in the written or video simulations. The simulation scenarios were randomly assigned to students within each cohort. to ensure that students were provided with a range of different complex scenarios with clients experiencing similar levels of emotional distress.

The setting for each simulation type was a classroom with the live actor simulations being held in a purpose build simulation room.

Type of scenario

Each simulation type included three different simulation scenarios: family/domestic violence, suicide/mental health, and hospital/medical. Each scenario was developed in consultation with local professional social workers working across these practice settings. The intention was to design scenarios that were common experiences in direct practice for social workers in each of these areas and that contained emotionally charged situations. The family and domestic violence scenario was designed to replicate an initial session for a person experiencing domestic violence who was seeking support after recently moving to a remote area and feeling quite isolated. The hospital scenario was designed to depict an older person being interviewed after being admitted to the hospital following a fall at home and lacking any informal support. The suicidal and mental health scenario was designed to reflect a youth mental health service where a young person supported by their mother, presented at the agency for an initial assessment due to the young person struggling with ‘fitting in’ at school and with relationships at home. Each scenario was designed as an initial session with the social worker to focus on the assessment of the client’s environment and needs. The simulation scenarios were randomly assigned to students within each cohort to ensure that students were provided with a range of different complex scenarios with clients experiencing similar levels of emotional distress. All scenarios were reviewed for validity by a team of professional social workers.

Psychosocial assessment

As part of the psychosocial assessment, students were asked to respond to a series of general assessment questions relating to the following areas that support the formulation of a professional risk assessment: 1) accommodation/living arrangements, 2) financial situation, 3) risk factors, 4) protective factors, 5) proposed intervention and short term follow up, 6) long term goals, and 7) identify the communication strategies utilized. Participants were instructed to provide bullet point responses to each of the seven questions, and then participants were scored against a standard marking rubric. Scores ranged from 0 to 2 in each of the 7 areas scored against a rubric with no response or a substandard response being scored as 0, a response with limited factors/plans/goals identified scored as 1 and a response with comprehensive factors/plans/goals scored as 2. The total possible score for this assessment ranged from 0 to 14 with higher scores indicating a more comprehensive and accurate psychosocial assessment.

The outcome measures were assessed by the lead author, an accredited social worker with over 10 years of experience in social work and field education. Reliability of scores was obtained by conducting random inter-rater reliability checked by a social worker with 10 years of experience in conducting risk assessments and supervising social work students in field placement settings. The social worker was provided with three participants’ responses from each scenario in each type of simulation activity, which meant a total of 27 participants responding to the 7 areas for a total of 189 responses cross-checked. Results were then moderated by the lead researcher to consider any results that differed. This process identified the social worker and lead researcher differed on 4 responses out of 189, with no centralization of errors in activities and simulation types and scores only differing between grades of 1 and 2 (i.e. difference in grades were not all located in the same simulation type or scenario). Thus, resulting in a 98% agreement in responses checked.

Results

Data from the study were analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.

Missing data

Approximately 90% of the participants did not have any missing data. For those participants with missing data resulted in the participant having all of their data removed. The decision to remove participants with missing data from the data set was decided upon so the responses included were complete and no assumptions on the participants’ ability in any missed response were made. In the outcome measure of the psychosocial assessment, participants were scored on 7 areas and therefore participants who did not respond to all seven areas were excluded as missing data. This removal of participants who answered less than seven questions was to ensure engagement with the activity for analysis. The removal of missing data resulted in the following response numbers: simulation type: actor (n = 112), traditional (n = 95), video (n = 66) and simulation activity: Family/domestic violence (n = 97), hospital (n = 103) and suicide (n = 73).

Data analysis

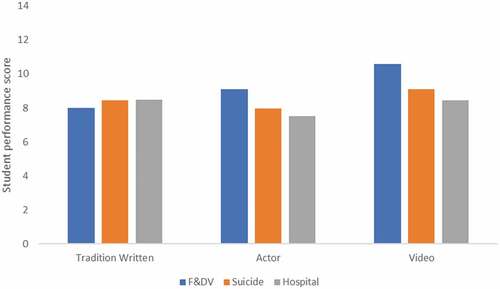

A series (factorial) of three types of simulation (traditional written case study, actor and video) by 3 scenarios (family/domestic violence, suicide, and health/hospital) resulted in a 9 group within a 3 × 3 between groups analysis of variance (ANOVA). This enables the main effect of type of simulation and type of scenario to be examined for differences in students’ mean scores on their performance in developing a psychosocial assessment. The ANOVA also assessed for any interaction effects between scenario types and whether these vary across types of simulation. provides means and standard deviations on the outcome variable for participants in each of the research conditions.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of student assessment performance across type of simulation type by type of scenario.

Findings revealed a significant main effect in the type of simulation on students’ ability to develop a psychosocial assessment [F (2,264) = 6.253, p = .002]. Post hoc analysis using LSD t-tests revealed that video simulation was significantly more effective (M = 9.30, SD = 2.1) when compared to actor simulation (M = 8.24, SD = 2.57) and traditional written case studies (M = 8.31, SD = 2.16). No significant differences were found between the simulation types of actor and traditional written case studies. Partially consistent with the first hypothesis, students were able to develop more comprehensive written psychosocial assessments skills when presented with video simulations compared to actors or traditional written case studies; however, the use of actors was not found to significantly enhance students’ ability to develop a written psychosocial assessment.

Findings also revealed a significant main effect of scenario type on students’ ability to develop a psychosocial assessment [F (2,264) = 5.50, p = 0.005]. In a similar outcome to the activity type, post hoc analysis using LSD t-tests found that family and domestic violence was significantly more effective (M = 9.06, SD = 2.59) than hospital (M = 8.07, SD = 1.83) and suicide (M = 8.44, SD = 2.55) scenarios. No significant differences were found between the scenarios of hospital and suicide. Thus, contrary to the second hypothesis, findings revealed difference between type of scenario. Students were significantly better at developing a written psychosocial assessment when presented with a scenario in family and domestic violence compared to a hospital or suicide scenario.

Findings also revealed a significant interactional effect of scenario activity within scenario type on students’ ability to develop a psychosocial assessment [F (4,264) = 2.99, p = 0.019]. Post hoc analysis using LSD t-tests found that family and domestic violence scenario in the video format had significant interaction with strong effects (see ). Contrary to hypothesis two, the findings revealed that students developed more comprehensive written psychosocial assessments skills when presented with the family and domestic violence scenario in a video format compared to all other experimental conditions. Interestingly, in the domestic violence scenario, the traditional written case study produced significantly lower student assessment performance scores compared to simulation with live actors and video.

Discussion

With the current demands on social work, both in practice and education, the need for alternate learning and assessment activities that provide students with real life complex experiences is paramount to the development of competent and skilled social workers. This research was designed to test the use of simulation-based education on the development of student practice skills. This paper applied CLT to simulation activities to better understand scaffolding of learning which reduced some complex factors associated with practice settings including emotionally charged environments. This scaffolded approach to practice skill development allowed students to maximize use of working memory before cognition entered overload. The research assessed differences between traditional written case-study learning, simulation with live actors, and video simulation in students’ ability to identify critical factors contributing to the development of a psychosocial assessment. It is essential that social work students have an opportunity to practice skills before engaging with real clients, to develop strong professional practice. This study adds to previous research (Asakura et al., Citation2020) in developing an evidence base for social work education to embrace the use of simulation to develop these skills in a practice setting that removes not only the fear of students harming others, but also the real possibility of harm in complex scenarios such as family/domestic violence, suicide, and hospital/medical settings.

Consistent with previous research (Huttar & BrintzenhofeSzoc, Citation2020; Jefferies et al., Citation2021b; Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020), this study found simulation to be effective as a learning tool for the development of essential psychosocial assessment skills that are crucial for social work students in practice. In summary, this research showed that video simulation was significantly more effective than either written case study or simulation with an actor, on students’ ability to develop a psychosocial assessment. This was particularly evident within the area of domestic and family violence. This research highlighted the limitation of written case studies which are traditionally used in social work education as a means to develop social work assessment skills. Furthermore, this research found that type of scenario/practice situation can also play a role in enhancing students’ learning with the family/domestic violence scenario showing more effectiveness compared to hospital/health or suicide. Social work, like nursing and medicine, should set simulation as a standard of practice and use it to train social work students. It is imperative that clearly defined practice standards be applied to simulation activities to assist education providers to provide sufficient support to enhance students’ learning outcomes. Social work professionals are faced with complex and ethically challenging practice scenarios just as other disciplines face professional challenges.

Research has shown that social work students lack opportunities within field education to obtain experience in complex direct practice cases (Jefferies et al., Citation2021a; Zuchowski et al., Citation2014). Before beginning a placement or graduating to practice, social work students need to have the opportunity to explore difficult scenarios and master core skills involved with professional practice. Lee and colleagues (Citation2020) talked about how social worker educators can help students improve their skills before they start working in mental health services. Through scaffolded learning in realistic circumstances, students can be introduced to essential areas of practice. If a student faces a suicidal client for the first time in practice, for example, cognitive overload may impair assessment abilities and decision-making. Consistent with the principles of CLT, students would be able to practice assessment and decision-making without interruption or distraction from external influences if they encountered this case in simulation before placement. Students could practice questioning, identifying risk and protective factors, and developing risk assessments and intervention strategies. Students should be able to transfer learning from their working memory to their long-term memory through repetition and automation in a genuine learning environment based on a thorough scaffolding or stepping through the process using simulation. Simulation education is an important tool in enhancing students’ confidence and skills in complex core social work practice areas.

This research provides evidence for the effectiveness of simulation in social work education in preparing students for these complex practice situations and giving them the opportunity to assess these high-risk cases in a low risk setting without real clients and fear of doing harm. Social work needs to consider the ethical concerns relating to working with vulnerable populations without first having the experience and capacity to practice responding to complex situations and practice to develop the required skills. Under the core value of ‘Respect for persons’ in the AASW Code of Ethics (Citation2010), social workers commit to fulling a duty of care to those they work with and to avoid doing harm.

Limitations

Despite the findings, this research is not without limitations. Although the sample was randomized across various conditions, this research only included students from one university in a regional setting, which may limit the generalizability of the study. It is recommended that future studies be conducted across different social work programs. In addition, there was a limit in the simulation types and simulation activities; therefore, further research should expand these to assess other forms of simulation such as the use of artificial intelligence and in different practice settings. This study was not designed to completely eliminate the student’s extraneous load, and it is reasonable to assume that the three types of activities—written case study, video-based and live actor—produced differing levels of extraneous load for students. While it might be reasonable to conclude a reduction in external factors associated with authentic practice environments compared to a traditional written case study, the variability between the practice settings and the three activities, in particular the video-based or live actor activities, was not controlled. Further research in this area is recommended.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of translation of this research into actual practice settings. Further research could assist in assessing how these activities have supported student abilities in either placement and/or practice in their ability to undertake a psychosocial assessment when faced with the context of (often emotionally charged) interactions with real clients. According to CLT, students should be able to utilize learning developed and committed to long term memory through engagement in these simulation activities to their practice in field placement settings resulting in enhanced assessment skills, but this needs further research.

Even with consideration to these limitations, this research demonstrates the potential of simulation in the training of social work students. The challenges facing social work education regarding field education are a continuous struggle for universities around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic has created significant challenges for social work education with community agencies forced to cease face-to-face work, which impacted their ability to continue supporting student placements in the traditional format. Given the difficulty of securing adequate field placement opportunities, social work educators struggled to create ‘real-life’ learning opportunities for social work students to complete their field placement hours and successfully gain the skills needed to meet graduate competencies. The future challenge is for the social work profession to embrace the use of simulation in social work education and to design a set of carefully scaffolded simulation activities to provide a standard of education available to students that ensures the development of essential and ethical practice skills.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gerard Jefferies

Gerard Jefferies is a lecturer in social work at the University of the Sunshine Coast and the current co-coordinator of the Master of Social Work qualifying program. Gerard completed his PhD researching the utilisation of simulation to develop practice skills in social work education. This research explored the differences between simulation technology and traditional case studies to advance the professional skills students require for practice. Gerard’s PhD research was titled ‘Rigor in authentic pre-placement assessment to strengthen student practice capacity’. Prior to coming to academia, his practice experience involved work in youth justice, mental health, homelessness and drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

Cindy Davis

Cindy Davis is the former Associate Dean of Learning and Teaching and currently the discipline lead of social work at the University of the Sunshine Coast. She has published over 80 peer-reviewed articles in social work, psychology, medical, public health, and nursing journals. She has been awarded grants to conduct research on various health issues including breast cancer survivors, cancer and HIV/AIDS prevention, premenstrual syndrome, and the needs of women with advanced breast cancer as well as teaching and learning grants.

Jonathan Mason

Jonathan Mason is the Course Coordinator for the Level 4 Master of Clinical Psychology (post-registration) and co-director of the Centre for Health, Wellbeing and Disability. His previous roles have included Clinic Director and Head of Psychology at a regional university. Jon’s primary area of research interest is in the field of Intellectual Disabilities. In the last five years, he has been awarded over $500,000 across several grants to investigate the development of an assessment methodology suitable for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. His other research interests include the use of simulation technology in teaching (for which he was the co-holder of a $200,000 grant to develop a suicide education program, with A/Prof Patrea Andersen) and the experience of burnout in students training to become registered psychologists. Prior to entering academia, Jon was the Director of Clinical Practice and Centre Director for the Queensland Forensic Disability Service, having previously worked as a Head of Psychology in forensic and forensic disability services in the UK. He sits on the Assessment and Accreditation Committee of APAC and has led many psychology accreditation assessments across Australian and overseas Higher Education Providers.

Raj Yadav

Raj Yadav completed his PhD at the University of Newcastle, Australia in 2013. His PhD, highly inspired by Foucault’s discourse and Lyotard’s postmodernism, explored the competing dynamics of the west versus the non-west in Social Work discipline. In solidarity with Others’ struggles, as well as building on Others’ history, knowledge, and experiences, his PhD thesis offered the very first account of decolonised and developmental social work. Given Raj’s interests in the areas of post-debates, especially committed to knowledge production in post-modernism, post-colonialism, and post-structuralism, he wishes to utilise these to (re-)imagining and (re-)vitalising social work in ‘our time’.

References

- AASW. (2010 , June 20). Code of ethics. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/1201

- AASW. (2013, June 20). Practice standards. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/4551

- AASW. (2020, March). Australian social work education and accreditation standards. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/6073

- Archer-Kuhn, B., Ayala, J., Hewson, J., & Letkemann, L. (2020). Canadian reflections on the Covid-19 pandemic in social work education: From tsunami to innovation. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1010–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1826922

- Archer-Kuhn, B., Judge-Stasiak, A., Letkemann, L., Hewson, J., & Ayala, J. (2022). The Self-Directed Practicum: An Innovative Response to COVID-19 and a Crisis in Field Education. In Baikady, R., S., M., S., Nadesan, V., & Islam, M.R. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Field Work Education in Social Work (pp. 531–540). Routledge India. doi:10.4324/9781032164946

- Asakura, K., Lee, B., Occhiuto, K., & Kourgiantakis, T. (2020). Observational learning in simulation-based social work education: Comparison of interviewers and observers. Social Work Education, 41(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1831467

- Bligh, J., & Bleakley, A. (2006). Distributing menus to hungry learners: Can learning by simulation become simulation of learning? Medical Teacher, 28(7), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601042335

- Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

- Bogo, M., Regehr, C., Power, R., & Regehr, G. (2007). When values collide: Field instructors’ experiences of providing feedback and evaluating competence. The Clinical Supervisor, 26(1–2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v26n01_08

- Bø, B., Madangi, B. P., Ralaitafika, H., Ersdal, H. L., & Tjoflåt, I. (2021). Nursing students’ experiences with simulation‐based education as a pedagogic method in low‐resource settings: A mixed‐method study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(9–10), 1362–1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15996

- Cameron, J. J., & McColl, M. A. (2015). Learning client-centred practice short report: Experience of OT students interacting with “expert patients”. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(4), 322–324. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1011691

- Clark, R., Kirschner, P. A., & Sweller, J. (2012). Putting students on the path to learning: The case for fully guided instruction. American Educator, 36(1), 5–11.

- Cleak, H., & Zuchowski, I. (2019). Empirical support and considerations for social work supervision of students in alternative placement models. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0692-3

- Cleak, H., Zuchowski, I., & Cleaver, M. (2020). On a wing and a prayer! An exploration of students’ experiences of external supervision. British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa230

- Coohey, C., French, L., & Dickinson, R. (2017). Core field instructor behaviors that facilitate student learning. Field Educator Journal, 7(1), 1–15.

- Fraser, K. L., Ayres, P., & Sweller, J. (2015). Cognitive load theory for the design of medical simulations. Simulation in Healthcare, 10(5), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000097

- Gibbs, D. M., Dietrich, M., & Dagnan, E. (2017). Using high fidelity simulation to impact occupational therapy student knowledge, comfort, and confidence in acute care. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1225

- Giles, A. K., Carson, N. E., Breland, H. L., Coker-Bolt, P., & Bowman, P. J. (2014). Use of simulated patients and reflective video analysis to assess occupational therapy students’ preparedness for fieldwork. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Supplement_2), S57–66. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.685S03

- Hawthorne, B. S., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., & Hattie, J. (2019). Well-being as a cognitive load reducing agent: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00121

- Huttar, C. M., & BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. (2020). Virtual reality and computer simulation in social work education: A systematic review. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1648221

- Jefferies, G., Davis, C., & Mason, J. (2021a). COVID-19 and field education in Australia: Exploring the use of simulation. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 31(4), 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2021.1945951

- Jefferies, G., Davis, C., & Mason, J. (2021b). Simulation and skills development: Preparing Australian social work education for a post-COVID reality. Australian Social Work, 75(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1951312

- Kacalek, C., Krautscheid, L., & Walkley, V. (2021). The clinical pause: An augmented approach to simulation debriefing in nursing education. Nursing Education Perspectives, 43(4), 258–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000879

- Kourgiantakis, T., Sewell, K. M., Hu, R., Logan, J., & Bogo, M. (2020). Simulation in social work education: A scoping review. Research on Social Work Practice, 30(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731519885015

- Lee, M., & Fortune, A. E. (2013). Do we need more “doing” activities or “thinking” activities in the field practicum? Journal of Social Work Education, 49(4), 646–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.812851

- Lee, E., Kourgiantakis, T., & Bogo, M. (2020). Translating knowledge into practice: Using simulation to enhance mental health competence through social work education. Social Work Education, 39(3), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1620723

- Likourezos, V., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2019). The variability effect: When instructional variability is advantageous. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09462-8

- Logie, C., Bogo, M., Regehr, C., & Regehr, G. (2013). A critical appraisal of the use of standardized client simulations in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 49(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.755377

- Martin, A. J. (2016). Using Load Reduction Instruction (LRI) to boost motivation and engagement. British Psychological Society.

- Nestel, D., Mobley, B. L., Hunt, E. A., & Eppich, W. J. (2014). Confederates in health care simulations: Not as simple as it seems. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 10(12), 611–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2014.09.007

- Nimmagadda, J., & Murphy, J. I. (2014). Using simulations to enhance interprofessional competencies for social work and nursing students. Social Work Education, 33(4), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2013.877128

- Reedy, G. B. (2015). Using cognitive load theory to inform simulation design and practice. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(8), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2015.05.004

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

- Van Merriënboer, J. J., & Sweller, J. (2010). Cognitive load theory in health professional education: Design principles and strategies. Medical Education, 44(1), 85–93.

- van Vuuren, S. (2016). Reflections on simulated learning experiences of occupational therapy students in a clinical skills unit at an institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(3), 80–84. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3/a13

- Wilson, E., & Flanagan, N. (2021). What tools facilitate learning on placement? Findings of a social work student-to-student research study. Social Work Education, 40(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1702636

- Young, J. Q., Irby, D. M., Barilla LaBarca, M. L., Ten Cate, O., & O’sullivan, P. S. (2016). Measuring cognitive load: Mixed results from a handover simulation for medical students. Perspectives on Medical Education, 5(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0240-6

- Zuchowski, I., Cleak, H., Nickson, A., & Spencer, A. (2019). A national survey of Australian social work field education programs: Innovation with limited capacity. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1511740

- Zuchowski, I., Hudson, C., Bartlett, B., & Diamandi, S. (2014). Social work field education in Australia: Sharing practice wisdom and reflection. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 16(1), 67–80.