ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the findings from a mixed methods study exploring the key learning experiences, the challenges, and the increased knowledge of interprofessional practice for students undertaking placement in the Social Work Student Health Clinic at Griffith University. The theoretical framework of the study is based on adult learning theory, a model for experiential learning. After placement had finished 36 students completed the Interprofessional Socialisation and Valuing Scale (ISVS-21) and a post-placement questionnaire that included a placement rating scale and a free text section specifically designed to collect data on student perceptions about learning outcomes while in the clinic. The quantitative data was entered into SPSS for statistical analysis. A thematic analysis of the qualitative data identified four major themes (key learning and beneficial aspects, the challenges, impact on future career options, and interprofessional practice). The themes were transformed into quantitative variables for further analysis using SPSS. The key findings indicated that the students perceived their achievements through participation in health clinics as providing positive learning experiences across a range of opportunities, some of which have impacted on future career options and an increased understanding of interprofessional practices in health care.

Introduction

Field education is an integral and compulsory component in all the social work degrees in Australia and requires students to complete 1000 h of supervised practice over two appropriate placements (Australian Association of Social Workers [AASW], Citation2020).

Placements are undertaken in a variety of practice settings (e.g. health services, community services, and statutory agencies, such as Child Safety and the Criminal Justice System. Data from the 2022 national consensus data (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2022) show that the general population in Australia is aging and becoming more culturally diverse. It is during placement that students are prepared to engage with the diversity that is inherent in culturally competent and safe practice.

Guided by the profession’s values and ethics, the aim of placement is to integrate theoretical knowledge with practice. As such, field education is underpinned by adult learning theory where, as outlined in D. A. Kolb’s (Citation1984: A. Y. Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005) model of experiential learning, adults learn by ‘doing’. McGuire and Lay (Citation2020) also highlight how learning theory is played out during placement as students learn to practice through active involvement with ‘real’ people with whom they perform a service, or a helping role. Rockey et al. (Citation2021) refers to this as ‘point of care teaching’ as, while on placement, students undertake health assessments and implement appropriate interventions under the direction of their supervisor. In doing so, it is the supervisor’s responsibility to ensure that the care clients receive from students is appropriate.

Student health clinics have been well established all over the world and are not a new concept as they provide innovative and creative ways to provide meaningful placement experiences for students while also providing them with opportunities to develop practice skills by delivering services to underserved communities (Authors).

The first Australian student-led clinic REACH (Realizing Education and Access in Collaborative Health) was established by the University of Melbourne in 2011 (Buckley et al., Citation2014). The Capricornia Project (Interprofessional Student Assisted Allied Health Clinic) established in 2011 by Queensland Health (Frakes et al., Citation2011) was closely followed by the development of the Sutherland Chronic Care Student-led Clinic in New South Wales (Tang & Stanwell, Citation2012) and the Victoria Mornington Peninsula Student Led Clinic (Kent, Citation2014).

Social work is recognized as an allied health profession in Australia that constitutes the largest group of allied health disciplines employed across public health sector (Deloitte Access Economics, Citation2016). Despite this, as Warren et al. (Citation2017) found when reviewing the literature about free health care student-led clinics, there was a paucity of literature exploring the perceptions and experiences of social work students in these clinics. In a systematic review of the literature, authors also found that very few studies included social work students, or, if a social work student presence was noted, it was more common in clinics that served lower income or marginalized groups.

Both Warren et al. (Citation2017) and Briggs & Fronek (Citation2019) suggest the absence of the role of social work in clinics reflects the ongoing hierarchies present in health services today, particularly in the Australian context where the experiences of social work students participating in these clinics remain under-reported. Furthermore, while undertaking a systematic review, authors found no specific studies about social work student-led health clinics.

A further search of the literature for studies on student-led health clinics undertaken between July 2017 and June 2022 yielded 27 studies, five of which included social work students on placement with other students. Apart from the Miselis et al. (Citation2022) study where positive changes among social workers and medical students in an interprofessional learning health clinic were found, social work student experiences in these clinics were not reported as a distinct group and no further studies on social work student-led health clinics were found.

Although the updated search of the literature is not fully described in this study, using the same research strategy and databases applied in the prior systematic review (Authors), the scarcity of research on social work student-led clinics was confirmed.

Background

Griffith University has a suite of on-campus student health clinics that provide quality, affordable health services for the public (https://www.griffith.edu.au/griffith-health/clinics). As well as providing an opportunity to develop health assessment and intervention skills, the clinics provide opportunities for interprofessional learning. In the clinics all students practice under the supervision of qualified practitioners.

As a strategy to increase capacity for meeting the demand for social work health placements, the Academic Lead for Griffith’s Social Work School’s field education program began developing a university student clinic in 2016 that started operating with two students in 2017. By 2018, the clinic had six social work students on placement and between 2019 and 2021 student numbers varied between 4 and 10 each trimester.

The Social Work Clinic comes under the auspices of Director, Griffith Health Clinics and is located within the Allied Health Clinic on Griffith’s Gold Coast campus. As such, it provides an excellent opportunity for students to undertake one of their field placements in a health-related setting. Academics within the social work school oversee the clinic, undertake liaison visits, and provide the required student supervision for students in the Clinic.

Universities have a duty of care for when students undertakeefield education. Risk analyses are concerned with the identification, evaluation, mitigation, or management of any issue that can negatively impact the student’s learning in the placement setting (Fleming & Hay, Citation2021; Hay & Fleming, Citation2021). Under AASW (Citation2020) guidelines, the Liaison Visitor maintains general oversight of the placement and it is their responsibility to respond and assist in the resolution of any concerns and issues that are raised by student, or the supervisor. The health clinic is a service provided by the University to the community at large. Having an academic staff member as the Liaison Visitor (who is not a member of the placement team), is the preferable option in this setting in terms of migration of risk for the student, the supervisor, and the University.

Unlike other clinics at Griffith, as well as practicing in the on-campus clinic building, the Social Work Clinic also offers an outreach service to schools in the Gold Coast catchment area. The request for an outreach clinic came from the Schools as, due to transport problems, having the clinic located on Griffith University campus prevented referred school pupils accessing the service.

The focus of the outreach student health clinic is on meeting the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral needs of individual school pupils and their families by providing individual assessments and short-term interventions. Weekly group work sessions tailored for specific problems (e.g. Anxiety, Social Phobia, and Body Image disorders) are also offered through the outreach clinic. Working in collaboration with school guidance counselors, career advisors, school principals, and teachers, the social work students design and develop the group work programs. This experience exposes the students to a school-based social work role, program development and implementation, and service provision to underserved populations.

Student clinics are underpinned by the concept of active student participation. This makes their voices, perceptions, and experiences a necessary inclusion in any evaluation of student-led health clinics. The study reported here sought to evaluate the key learning opportunities and benefits, the challenges, and any impact on future career options alongside an increased understanding of the importance of interprofessional practice in health services for social work students undertaking placement in a university student health clinic.

Methodology

The study employed a mixed-method design that enabled the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data concurrently. After an initial analysis of both sources of data, the results were compared (i.e. triangulated) to provide a more in-depth understanding of the students’ perception, challenges, and experiences of their learning in the social work clinic.

Quantitative data collection

A self-report questionnaire specifically designed for this study allowed for the collection of quantitative demographic data and a student rating of their overall experience while undertaking the clinic placement by circling a response on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = an extremely poor experience and 7 = an excellent experience.

Interprofessional learning was assessed by completion and scoring of the King et al. (Citation2016) Socialisation and Valuing Scale (ISVS-21). This self-report measure has excellent psychometric properties for measuring the degree of inter-professional socialization in both practitioners and students. Participants indicate their response about the beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes that they hold, or display, in each of the item statements. The items are anchored on a 7-point Likert scale with 1 = not at all and 7 = to a very great extent.

Qualitative data collection

The questionnaire included a free-text section to capture students’ perceptions of their overall learning, the challenges experienced while in the clinic, what aspects of the placement they perceived were the most beneficial and the effect, if any, the placement may have on their future employment plans.

Whether the placement had increased a student’s understanding of the role of other health-care professions was also explored. A final question asked for any suggestions or comments for future student placements in the clinic.

Analysis

The quantitative data was coded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26) predictive analytics software. Using the coding framework described by O’connor and Joffe (Citation2020), the free-text questions were read by two members of the research team and manually coded. This allowed for a list of codes to be established, defined, and organized into themes by both the primary researcher and a second reviewer. The assigned codes were reviewed by both reviewers and variations discussed. Given the close agreement on the coding, a codebook was written, and a list of themes was generated and thematically analyzed to identify the key critical learning experiences.

While the quantitative and qualitative data were initially analyzed separately, four major themes arising out of the qualitative findings converged with the quantitative data. After discussion among the research team, the themes were considered alongside the quantitative findings and were able to be transformed into quantitative variables for entry into SPSS for further analysis.

Recruitment and procedures

In total 40 social work students commenced placement in the clinic between 2017 and 2021. One student exited the placement due to ill health and another withdrew from the academic program. Participation in the study was voluntary. At the end of the final visit, the liaison visitor discussed the study with the remaining 38 students and provided a participant information sheet, a consent form, the post-placement questionnaire, and the ISVS-21 scale. After placement had finished 36 students decided to participate in the study and deposited a signed consent form, the completed questionnaires, and the ISVS-21 scale in a designated locked research mailbox for collection by the researchers.

Ethics approval

The study had approval from the Griffith University’s Human Research Ethics Review Committee (GU Ref No: 2017/340).

Results

Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis, median values, and standard deviations were ascertained for the two Likert scales. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were also conducted to ascertain any significant differences in the findings for first and second-placement students across two cohort years in the Master and Bachelor of Social Work degree programs.

Demographics

The overall demographic characteristics of the participating students are shown in . The sample consisted of 34 female students (mean age = 29 years, range 26–55 years) and two male students (mean age = 26 years; range 26–41 years). Of these students 14 (39%) were undertaking first placement and 22 (61%) second placement. Forty-two percent of the students had listed a clinic placement as their first preference, 52% had initially selected another option, and 6% had no specific placement preferences. Fifty percent of the students had previous qualifications (31% were in health care) and 25% had previous experience of working in health settings.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 36, mean age = 29.14, Std = 9.58, range 20–55 years).

Rating of overall placement experience

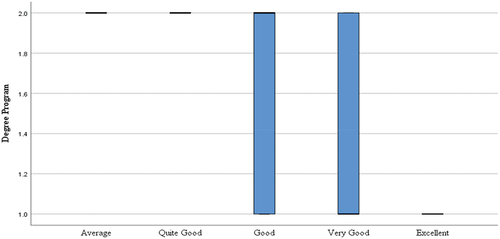

Data analysis revealed 80.5% of the students rated the overall placement experience in clinic on the 7-point Likert scale as being either ‘very good, or good’ (). The total sample median score = 5.00 (Std. Dev = 967; Range = 3–7) and median scores for first or second placement and degree programs are shown in . A one-way ANOVA found no significant differences between the first- and second-placement students nor the degree programs F(4,31) = 1.29, p = .294). This suggests that overall the placement has been a positive learning experience.

Figure 1. Student responses to on overall placement experience rated on 7-point Likert scale 1 = very poor−7 = excellent.

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of degree programs with student ratings of placement experience (N = 36).

Interprofessional practice learning

While there was no opportunity to obtain a baseline measurement prior to placement starting, post-placement student responses on the 7-point Likert scale contained in the IVSV-21, showed that 69.4% of the students had an awareness of interprofessional socialization ranging from ‘a fairly great extent to a great extent’. The ISVS-21 total sample median score = 5.70 (Std. Dev = .350; Range = 4.50–7.00) and the median scores for first or second placement and degree programs are shown in . A one-way ANOVA found no significant differences between the degree programs and the first- and second-placement student responses F(14,21) = .719, p = .734).

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of degree programs with student median scores on the ISVS-21 Scale (N = 36).

The students in the clinic did work with other professionals, especially, in the school outreach clinic where they engaged with inter-professional teams of teachers, behavioral therapists, and guidance counselors. Other studies (Iachini et al., Citation2016; Mancini et al., Citation2019) found when preparing students for interprofessional practice that most demonstrated a readiness to learn the roles and responsibilities of other disciplines. Items 16 on the IVSV-21 scale ‘I have gained a better appreciation of the importance of a team approach’ and Item 21 ‘I have gained an appreciation for the benefits in interprofessional teamwork specifically relate to the importance of interprofessional teamwork’.

Further analysis of these two items showed that 72% of the total sample rated Item 16 as occurring from a ‘great extent-very great extent’ (total sample median score = 6.00; Std. Dev 16.66; range 2–77) and 68% rating Item 21 as occurring from a ‘great extent-very great extent’ with a total sample median score = 6 (Std. Dev 1.58; range 0–7). These scores are consistent with other studies that collected pre- and post-measurements on ISVS-21 to evaluate interprofessional socialization exposure with social work students (Acquavita et al., Citation2020; Aul & Long, Citation2020; Miselis et al., Citation2022). This suggests that the clinical students did gain an understanding of professional roles and responsibilities in health care.

Themes

The four main themes identified from the qualitative responses in the post-placement questionnaire (key learning and beneficial aspects, the challenges, impact on future career options and interprofessional practice) highlighted the learning achieved while on placement in the clinic. As shown in , the considerable overlap in the identified themes puts the above quantitative findings into context.

Table 4. Cross-tabulation degree program with student perceptions of placement experience on key learning, beneficial aspects, challenges, interprofessional, and impact on future employment (N = 36).

Theme 1: key learning and beneficial aspects of placement

Most of the students rated the placement as being a positive and beneficial experience that provided an opportunity for key learning. However, four students made the point that the level of learning was dependent on their supervisor and made the following comments:

I only got minimal direction from my supervisor so much of my learning was self-directed … I had to transition from one supervisor to another one as it wasn’t working out with the first one … I couldn’t communicate with my supervisor at all which made it very hard for me … I couldn’t discuss my questions in supervision, things got very confused and felt I needed strong self-learning skills in the placement.

This finding is consistent with other social work studies that have found the student-supervisory relationship to be a major factor during placement as it facilitates much of the student learning and development of the professional identity (Shlomo et al., Citation2012; MacDermott and Campbell, Citation2016).

Within this same theme achieving new practice skills, followed by group supervision, with simulated learning to complete mental health assessments, were the two key responses recorded in post-placement questionnaire. Other responses (such as undertaking assessments and interventions in the university clinic space and during outreach in schools) would also come under learning new skills for practice.

Two students put it succinctly when stating:

Having the opportunity to learn how to undertake and write psychosocial assessments, implementing interventions and doing counselling were all new practice skills for me … assessing kids, counselling and running groups in the schools was a new and beneficial learning experience for me …

Theme 2: the challenges

Many of the key learning experiences and beneficial aspects of the placement were also perceived as challenges by the students. Although the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated the greatest crisis higher education has ever experienced, the immediate and full impact was felt by students undertaking placements (Briggs et al, Citation2022). While several of the students mentioned the impact of COVID on their placement and having to transition to a telehealth service, nine specifically noted these challenges as being:

Having to work from home and manage the COVID situation … having to do telehealth training… using telehealth with clients … feeling isolated from the clinic … not having a supervisor nearby.

Another three saw the lack of referrals to the on-campus clinic as a challenge:

Lack of client time in the on-campus clinic didn’t allow for networking with other clinics … plenty of school referrals, but I wanted to work more in the health clinic … learning how to engage clients as I only saw two in the clinic.

Theme 3: impact on future career options

Placement in the clinic provided an opportunity for the students to practice in both a health and school setting. Student responses to the question about any impact the placement may have had on future employment plans indicated it had made them realize there were more options available than previously envisaged:

Exposed me to more career choices than previously thought … rethinking my options … didn’t see health as an option previously … I want to work in mental health setting … changed my views on career options … confirmed wanting to work with youth … I’m more confident now about wanting to do school social work.

Theme 4: interprofessional teamwork

Multiple responses were made to question about the perceived benefits of interprofessional practice. While most were very positive, some were not. The most pertinent ones were as follows:

Multidisciplinary approach improves quality of client life … can now see how social workers, teachers and guidance officers can work together … case work needs a collaborative approach … great working with a psychologist and speech therapist, team approach provides safety for the clients … the placement helped me see the importance of social work in interprofessional teams.

While the understanding of different professional roles increased for most of the students for three students it highlighted the struggle for social workers working in health services:

Had to advocate for social work inclusion in case management … health social work role not recognised … power struggles among the different disciplines … as a social worker I was ignored although part of the multidisciplinary team … curious about how social workers in health get on.

Future clinic placements

The post-placement questionnaire also asked the students for comments and suggestions regarding future placements. Responses are shown in . Two main areas were identified as needing improvement within the clinic environment. The first was needing more time to practice in the on-campus clinic (42%) as this is where the students perceived they gained most of their key learning. It also acknowledged that increasing time in the clinic was dependent on the number of referrals made to the clinic. Clarity around expectations of the student role and needing more supervisory support and direction (19%).

Table 5. Students’ suggestions for future clinic placements (N = 36).

Of note, 5.6% of the students commented on the need to educate reception staff about intake into the social work clinic as some referrals were sent directly to the psychology clinic even though clients had specifically asked to see a social worker. Two comments highlighted this issue:

When ringing reception to see a social worker for counselling a client was told that social workers don’t do counselling and was put on an 18 months waitlist to see a psychologist … I saw a client during the dentist-social work Triage Day, she later rang to make an appointment with me, reception referred her to psychology.

Other suggestions included better marketing of the clinic and running the clinic continuously throughout the year rather than only during student placement times.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to evaluate the learning experiences students had in a university social work student health clinic. Practice-based education, a core element and essential component of professional social work programs, is based on the theory of experiential learning (A. Y. Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005; D. A. Kolb, Citation1984). Student-led health clinics offer valuable opportunities for student learning while meeting the health-care needs of underserved communities. The Griffith Social Work Clinic provides both a service to populations in need and a health placement for students undertaking social work degrees.

All the students in this study were undertaking an accredited social work degree and were completing either a first or second placement. Combining the survey results with thematic analysis from the post-placement questionnaire provided a deeper level of understanding of the students’ clinic experiences and a space for the student voice to be heard. In the main, the students rated their placement in the clinic as being either good or very good. It was also found that the learning experience did not differ significantly by year of training nor the degree being undertaken.

In a variety of ways, the students saw their learning was dependent on the supervision and direction they received from the supervisor. This finding was supported by other studies and highlights the importance of having appropriately qualified and experienced social work supervisors in a health clinic.

The event of COVID-19 did impact on students undertaking placement, making it challenging to provide practice experiences that would enable them to demonstrate the core required competencies when unable to engage with clients face-to-face. However, it also brought opportunities and the students did make the transition to using telehealth, a skill they may well need to use in future practice.

The aim of interprofessional education is to assist students gain a positive team-based identity and an appreciation of the role of other disciplines. The results of the ISVS-21, together with the descriptive analysis of the free-text questions indicate that the students’ perceptions of the role of other health professionals, and their understanding of the benefits of interprofessional practice, increased over the duration of the placement.

This finding is very relevant as it suggests that despite some negative experiences the students experienced, they were ready to understand other professionals’ roles and responsibilities and know, that as social workers, they have a contribution to make as a member of an interprofessional team.

The study identified opportunities for improvement within the social work clinic. That is, for some students, despite the formal curriculum teaching they had received prior to undertaking placement, in the clinic their knowledge appeared insufficient in terms of applying it in practice. As Rockey et al. (Citation2021) note, when applying classroom knowledge to practice, students need supervisors who are strong role models who can teach, and supervise, in a setting where quality client care can be delivered while achieving the learning requirements of the placement.

Limitation and strengths of the study

There were both limitations and strengths to this study. The first limitation is the relatively low number of referrals coming into the clinic. Further development and marketing of the clinic could see an increase in referrals, which in turn would increase the time the students can practice in the on-campus clinic. The second is that to date the clinic has been staffed by academics and the oversite and supervision of the students placed in the clinic is additional to their work load. Dedicated full-time posts for appropriately qualified and experienced health social workers are needed to allow time to better market the clinic (thereby increasing the referral base) and to increase the amount of support for each student. It would also allow time for the supervisor to provide more ‘hands on teaching’ and more direct supervision of the students, while they are undertaking assessments and implementing interventions with their clients.

A third limitation is that the IVSV-21 was only able to be administered post-placement, which did not allow for pre-post statistical comparisons to be made in terms of interprofessional learning. The only comparison that could be made was with other studies that had reported changes in mean scores following interprofessional training. This study, however, showed that by the end of placement, the clinic students’ IVSV-21 scores were in the same range as other students who had received interprofessional training (Acquavita et al., Citation2020; Aul & Long, Citation2020; Miselis et al., Citation2022).

Fourth, the final 2 years of the study were carried out under difficult conditions due to the COVID pandemic. This was both a key learning and a challenge as it disrupted placement for period of time and required the students to work from home, as well as having to make a quick transition to the use of telehealth. However, while having to practice remotely was challenging it also provided a key learning opportunity for students, which will better prepare them for any future pandemics.

A strength of the study was the use of mixed methods as having collected both quantitative and qualitative data the themes were able to be considered alongside the quantitative findings. This allowed for a comparison between the statistical findings and the responses made in the post-placement questionnaire. In this way, the voices of the students, were able to be heard.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to report on the establishment of a university social work health clinic and the experiences of students undertaking placement in the clinic. The study did show that overall, the placement provided a good learning environment and certainly had beneficial aspects for students going into practice on completion of their degrees. It is also clear that for future success of the clinic it needs to be more appropriately staffed.

Overall, the findings from the study contribute to a gap in the literature to date about social work-specific student-led clinics. Furthermore, while student-led clinics are not a new concept, to our knowledge, this is the first specific student social work health clinic in Australia.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all of the students who participated in the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lynne Briggs

Lynne Briggs is an academic in the School of Health Sciences and Social Work at Griffith University. She has reserched and published widely in the specialist areas of child sexual abuse, mental health outcome studies, demoralization, interventions in disasters, gender, supervision and field education.

Patricia Fronek

Patricia Fronek is Associate Professor at Griffith University, and Member of the Law Futures Research Centre and the Disrupting Violence Beacon. Her research in adoption is widely published in social work, health, international social work, adoption, surrogacy and disability.

References

- Acquavita, S. P., Lee, B. R., Levy, M., Holmes, C., Sacco, P., & Harley, D. (2020). Preparing master of social work students for interprofessional practice. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work (2019), 17(5), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2020.1781730

- Aul, K., & Long, J. (2020, January 01). Comparing the perceptions of interprofessional socialization among health profession students. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 18(3), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2020.1779

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (AASW). (2020). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS). https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/13565

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022, June). National, state and territory population. ABS Website. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population

- Briggs, L., & Fronek, P. (2019). Student experiences and perceptions of participation in student-led health clinics: A systematic review. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(2), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656575

- Briggs, L., Maidment, J., Hay, K., Medina-Martinez, K., Rondon-Jackson, R., & Fronek, P. (2022). Challenges and innovations in field education in Australia, New Zealand and the United States. In P. Fronek & K. Smith Rotabi-Casares (Eds.), Social work in health emergencies (pp. 277–290). Routledge.

- Buckley, E., Vu, T., & Remedios, L. (2014). The REACH project: Implementing interprofessional practice at Australia’s first student-led clinic. Education for Health, 27(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.134360

- Deloitte Access Economics. (2016). The registration of social workers in Australia (Report). Australian Association of Social Workers, Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/8806

- Fleming, J., & Hay, K. (2021). Understanding risks in work-integrated learning. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 22(2), 167–181.

- Frakes, K., Tyack, Z., Miller, M., Davis, L., Swanston, A., & Brownie, S. (2011). The Capricornia project: Developing and implementing an interprofessional student-assisted allied health clinic. Clinical Education and Training Queensland Health.

- Griffith University. Health clinics-social work. https://www.griffith.edu.au/griffith-health/clinics

- Hay, K., & Fleming, J. (2021). Keeping students safe: Understanding the risks for students undertaking work-integrated learning. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 22(4), 539–552.

- Iachini, A. L., Dunn, B. L., Blake, C., & Blake, E. W. (2016). Evaluating the perceived impact of an interprofessional childhood obesity course on competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 394–396. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1141753

- Kent, F. M. (2014). The interprofessional student-led clinic: Supporting older people after discharge from acute hospital admission (Final Report). State Government of Victoria, Department of Health

- King, G., Orchard, C., Khalili, H., & Avery, L. (2016). Refinement of the Interprofessional Socialization and Valuing Scale (ISVS-21) and development of 9-item equivalent versions. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 36(3), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000082

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Learning Management & Education, 4(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

- MacDermott, D., & Campbell, A. (2016). An examination of student and provider perceptions of voluntary sector social work placements in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 35(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1100289

- Mancini, M. A., Maynard, B., & Cooper-Sadlo, S. (2019). Implementation of an integrated behavioral health specialization serving children and youth: Processes and outcomes. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(4), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1661905

- McGuire, L., & Lay, K. (2020). Reflective pedagogy for social work education: Integrating classroom and field for competency-based education. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1661898

- Miselis, H. H., Zawacki, S., White, S., Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L., Mostow, C., Furlong, J., Mott, K. K., Kumar, A., Winter, M. R., Berklei, F., & Jack, B. (2022). Interprofessional education in the clinical learning environment: A mixed-methods evaluation of a longitudinal experience in the primary care setting. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(6), 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2025768

- O’connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Rockey, N. G., Weiskittel, T. M., Linder, K. E., Ridgeway, J. L., & Wieland, M. L. (2021). A mixed methods study to evaluate the impact of a student-run clinic on undergraduate medical education. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02621-y

- Shlomo, S. B., Levy, D., & Itzhaky, H. (2012). Development of professional identity among social work students: Contributing factors. The Clinical Supervisor, 31(2), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2013.733305

- Tang, M. F. M., & Stanwell, L. (2012). The Sutherland chronic care student led clinic student orientation manual. NSW Health.

- Warren, S., Puryear, E., Chapman, M., Barnett, T., & White, L. (2017). The role of social work in free healthcare clinics and student-run clinics. Social Work in Health Care, 56(10), 884–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2017.1371097