ABSTRACT

Social work students on practice learning placement undertake a range of learning activities and are expected to reflect independently on their strengths and areas for development within an intervention to develop their knowledge and skills. This is often supplemented by reflective discussion in social work student supervision. Nevertheless, supervision is undertaken in a private space, so has rarely been subject to scrutiny. The uniqueness of this study is founded in two core differences. This is one of the first research studies to include both supervision participants’ perspectives and one of the first that observed social work student supervision, giving it a unique data perspective that enriched the significance of the findings. The methodology for this thesis was firmly rooted in a Narrative Inquiry, which enabled the use of a range of data collection methods which were thematically analyzed to identify two core themes of diligence and collaboration. A model is presented that develops the principle of experiential learning, applying the importance of diligent preparation for and collaborative participation within social work student supervision by both practice educator and student to enhance the development of students’ knowledge and skills.

Introduction

Social work students in England undertake two practice placements in their qualifying course. The practice learning placement requires the development of each of the core social work knowledge and skills through experiential learning. Merely doing the learning activity is considered insufficient and students are required to undertake individual reflection to develop their understanding and develop their social work knowledge and skills (Bogo, Citation2010). This article will argue that the use of collaborative reflection with the student’s practice educator in social work student supervision enhances development of knowledge and skills. The term practice educator will be used to reflect the person who supervises the student in practice, often also referred to as practice teacher or practice supervisor.

In the mid-nineteen-eighties, two distinct reflective models were developed. Whilst these were not developed in direct relation to social work practice and development, they remain influential. The first was that of the reflective practitioner (Schon, Citation1983). It was acknowledged that a practitioner makes reflective decisions in the moment that weighs their knowledge base, skill set, and needs of the individual situation. This was important to recognize: that there is a basis that enables the practitioner to implement evidence-based decision-making. However, Schon identified a second reflective point. The practitioner reflects on their work and uses understanding of what worked successfully to inform future practice, as well as critically analyzing how the task could be undertaken in an enhanced way to optimize future outcomes. He called this reflection-on-action. In turn, reflection on action enabled more effective reflection in action as the practitioner is more understanding and knowledgeable of practice.

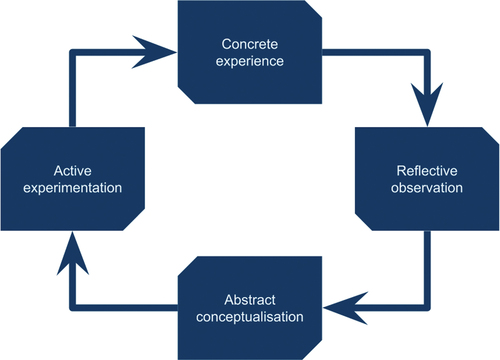

Shortly after the publication of Schon’s book, came Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning cycle, which has subsequently been modified in a variety of ways, but all have the same underpinning principles that provide a way to reflect on action. Kolb based his ideas on Knowles (Citation1973) andragogical principles that adult learning is best when it is practical, build on existing knowledge, and is goal-orientated, and Lewin’s dedication to the integration of theory to practice and an understanding that nothing happens in isolation.

As shows, the experiential learning cycle requires the person to undertake an activity, having concrete experience, which they are asked then to reflect upon to consider what they felt went well and what did not go as expected, using reflective observation. This is followed by a period of abstract conceptualization, where the person applies theory and knowledge to the situation, to develop an understanding of why the result was as it was and consider different theories to inform future practice. This is followed by a planning stage, where different options are considered to enable consideration of the most appropriate way to undertake the activity again, the principle being that students learn from both their successes and mistakes and apply them to future interventions. Kolb (Citation1984) argued that one of these stages alone is insufficient to develop knowledge and skills, but that all should be undertaken to optimize experiential learning.

Figure 1. Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning cycle.

Experiential learning is a foundational pedagogical for the development of knowledge and skills on social work placement (Bogo, Citation2010), where in England student reflection is afforded significant emphasis as one of the nine core Professional Capability Framework (PCF) domains that form the assessment criteria (BASW, Citation2018). Students are expected to undertake individual reflection on all their interventions, which often includes the form of written reflections for academic assessment. Ingram (Citation2021) argued that experiential learning can be enhanced through reflective discussion within social work student supervision. First, it is reasoned that reflective discussion in supervision teaches students how to reflect, for example where Rawles (Citation2020) recommended that practice educators support social work students to develop a critically reflective approach to case discussions in supervision to develop their skill of professional judgment making. Secondly, it enhances their reflection as they are able to contemplate and consider decision-making to ensure more appropriate outcomes with the support of the practice educator’s practice wisdom and evidence-based knowledge (Davys & Beddoe, Citation2009). The notion that reflective discussion enhances individual learning is not new as Lewin identified that participation in groupwork enhanced learning as participants benefitted from being exposed to a wider range of perspectives. Argyris and Schon (Citation1974) focused on reflective discussion, where they recommended an open and honest discussion that respects each other’s views to enable new thinking, development of ideas, and learning to occur.

Every attempt to try new behaviour is reinforced by the instructor. (Argyris & Schon, Citation1974, p. 128)

When transferred to social work student supervision, the benefit of more than one perspective can be applied. Reflective discussion can create a greater sense of connectedness between participants, reduce power differentials, stimulate a greater sense of openness to learning, and enhance outcomes for service users, as the social worker is better placed to understand the socially constructed oppression and social justice issues the service user experiences, a core social work value (Fook, Citation2015; Hair, Citation2014; Rankine et al., Citation2018). This contributes to the development of their emotional intelligence as they understand the impact of self on others and develop empathic understanding of others perspectives (Ingram, Citation2021). Reflective discussion is effective because

reflection is most profound when it is done aloud with the aware attention of another person. (Knights, Citation1985, p. 85)

Within social work student supervision, the existing literature suggests that reflective discussion supports the development of students’ knowledge and skills. Reflective discussion required collaborative participation by both supervisory participants and the collaborative exploration of ideas to develop students’ initial reflections (Brodie & Williams, Citation2013; Rawles, Citation2020; Wilson & Flanagan, Citation2019). However, it was found that this needed to be supplemented with the practice educator both validating students’ ideas and extending the thinking by challenging their reasoning (Rawles, Citation2020; Roulston et al., Citation2018), whilst positive reinforcement and constructive feedback enhanced reflective discussion (Litvack et al., Citation2010; Miehls et al., Citation2013; Wilson & Flanagan, Citation2019). Ketner et al. (Citation2017) research identified that practice educator participants saw themselves as motivators and reflective partners to enable students’ development through exploration of ideas whilst student participants saw social work student supervision as an opportunity to gain feedback and support, and to develop their social work knowledge and skills through reflective discussion. In addition, reflective discussion was enhanced when the practice educator was seen to be open to challenge (Litvack et al., Citation2010), as collaboration indicates that both participants have equally valued perspectives. Further research that explored reflective discussion (Brodie & Williams, Citation2013) and skill development (Rawles, Citation2020) in social work student supervision was recommended.

Method

Undertaken as part of a doctorate thesis, this research utilized a narrative inquiry (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990) methodology to explore practice educators’ and students’ experiences of social work student supervision. Narrative inquiry bases its philosophy upon the remit that we can learn from the stories of how those before us experienced things and learn from both their mistakes and their successes to enhance our own behaviors. The uniqueness of this study is founded in two core differences to previous research. This is one of the first research studies to include both supervision participants’ perspectives, or narratives, and one of the first that observed social work student supervision, giving it a unique data perspective that enriched the significance of the findings. This research project gained local Higher Education Institute (HEI) ethical approval (Leeds Beckett University ethical approval 50,859). The aims of this research were to develop an evidence-base to supplement the practice wisdom available in informing practice education practice and to identify good practice in the development of student knowledge and skills in social work student supervision. The research objective was to understand both practice educators’ and student’s perspectives of their experiences of social work student supervision.

The research population came from experienced practice educators, defined as those who had practice educated more than one student, and their current student. Both practice educator and student had to consent to participate. The sample of practice educator research participants were female n = 5 and male n = 3, white-British n = 8, and aged 30+ n = 7 and −30 n = 1. The student research participants were female n = 7 and male n = 1, white-British n = 6, Black African n = 1 and mixed heritage white and black Caribbean n = 1, and aged −30 n = 6 and aged 30+ n = 2. Within the research study, eight social work student supervisions were observed, audio-recorded, and transcribed. In addition, the sixteen research participants were interviewed, which was also transcribed. Finally, the data was subjected to thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Whilst the researcher should remain neutral and listen to the research participant’s perspective and analyze it without prejudice, positionality is important because it enables the researcher to acknowledge any potential bias. As a social worker, practice educator, social work educator, and therefore insider researcher, it was important to be aware of my positionality. I had to acknowledge that my construct of supervision comes from my own experiences, personal, professional, and cultural as any research is approached with a social construction that comes from our own place in society (Warren & Hackney, Citation2000). Therefore, when conducting the data collection, I utilized social work skills of active listening (Beesley et al., Citation2018) to ensure that I heard the research participants’ perspectives rather than assume a shared understanding. The insider researcher, whilst having the benefit of understanding context and meaning without explanation., can also be disadvantaged by the pre-conceived context and meaning that may leave them not clarifying details with participants (Mercer, Citation2007). By being reflective on their positionality the researcher can minimize unconscious bias and enhance the validity of the research outcomes (Mason-Bish, Citation2019).

Limitations

This research study used an availability sample, which may have resulted in only supervisory participants volunteering who felt confident in their social work student supervision, which could have slanted the research findings positively. This is a small-scale study, with less than ten research dyads involved in a localized area where placement and supervision procedures are standardized. Most practice educators had undergone the same practice educator training and had not experienced alternative practice educating models or philosophies. Furthermore, the placement providers all came from a statutory perspective. A wider research population would be beneficial in future research.

The social work students, despite efforts to extend to a second social work education provider, all came from one university, albeit from different cohorts. Finally, this research focused exclusively on the traditional social work education route, and the inclusion of the fast-track social work courses or apprenticeship routes may have been beneficial. Each of these constitutes a limitation to the study and would be a recommendation to be included in future research. Nevertheless, narrative inquiry methodology (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990) advocated that the narratives that are gathered during data collection are the ones that should be analyzed and presented.

Results

Firstly, the research participants narratives identified diligent preparation in the form of pre-supervision reflection by both practice educator and student. PE-Lena reflected that

Practice educator narratives

‘for me, I need to be prepared.’ PE-Lena

And I did some bullet points, in relation to things that are current and appropriate for me, erm, and anything else that I wanted to discuss.’ PE-Cathy

PE-Lena reflected that social work student supervision was more than attending it, it required time spent preparing for it. In addition, PE-Cathy reflected that she would spend some time preparing ‘bullet points’ before she attended the social work student supervision, as a prompt and reminder for herself to ensure that it covered everything that was required. This indicated that being prepared enabled supervision to be more effective and students’ learning needs to be addressed. Similarly, student preparation also had an impact. In the following example, PE-Lena responded to S-Karen’s preparation for supervision, where her understanding of a referral contributed to the supervision discussion.

Supervision transcript

PE-Lena: Yeah, I think you’ve raised a really important point, a valid point. And to be honest, I’d not put that on my list of things. I’d not looked through the referral to the extent that you have so I’ve just noted the reasons for it, but you’re right. But the other things that I picked up are the respite in June, you picked up quite rightly about the query about the carers assessment, and the other thing I picked up is, do you think that they’d benefit from some regular care provision now?

This illustrated that although PE-Lena had prepared, S-Karen’s preparation had enhanced the supervision further. This identified that preparation by both participants is best. S-Karen’s preparation enabled her to provide her insight into the referral and offer a reflective opinion. S-Karen and PE-Lena both read the same documentation and S-Karen had identified different pertinent areas, highlighting the importance of a collaborative approach where ‘two heads are better than one’, as each person will have a different cognitive lens that results in differing ideas that can enhance both participants’ understanding. The reflective discussion that followed this supervision transcript extract went on to explore the point that S-Karen had identified, thus her pre-supervision preparation enhanced the range of issues to be discussed and ultimately S-Karen’s knowledge and skill development. It is an important illustration of how impactful preparation can be and how both participants have a responsibility to take the initiative to be ready to participate.

Observational fieldnotes

Both PE-Lena and S-Karen are organized, with agenda items, prepared areas for discussion, and knowledge of cases. This gives the supervision a sense of purpose, order, and direction, which makes it feel efficient. However, the knowledge of cases that both PE-Lena and S-Karen have also enabled this efficiency, as there is no need to recap what has happened which takes up valuable supervision time. A brief overview was sufficient to precede in-depth discussions that enabled exploration of the service user’s needs and S-Karen’s development. PE-Lena was able to ask pertinent questions and S-Karen was able to respond quickly to questions as they were both prepared for the reflective discussions.

The observational fieldnotes highlight that PE-Lena’s and S-Karen’s preparation was observed as both are ‘organized’. However, it is the positive impact of both supervision participants being ‘organized’ on the flow and efficiency of the supervision that is significant as it is ‘a sense of purpose, order, and direction, which makes it feel efficient’. This enabled supervision to focus on the development of knowledge and skills through time allocated to reflective discussion, which they valued.

By contrast, the following example reflects on the impact when students had not undertaken the requested pre-supervision preparation by engaging in a set activity.

Observational fieldnotes

There was a clear incongruence between PE-Angela’s organized approach of providing activities for S-Isabelle to reflect upon between supervisions and attend supervision prepared and ready to reflect on her learning from them, and S-Isabelle’s less prepared approach of seeing the activities as to be undertaken during the supervision. This resulted in PE-Angela having to spend time in the supervision explaining the activity rather than reflective discussion that explored S-Isabelle learning from the activity.

The observational fieldnotes illustrated that the social work student supervision was less efficient as time was spent exploring what the activity was and then undertaking it rather than reflecting on her thoughts from it. If compared to PE-Lena and S-Karen’s supervision, one can see that social work student supervision benefits, and is arguably more effective, where preparation by the student enabled time to be allocated to reflective discussion to develop knowledge and skills rather than exploring how to undertake the learning activity. However, student’s reflective thoughts in supervision were supplemented with practice educator collaborative input.

Student narrative

I think that she’s just not judgmental and she helps me to weigh things up from both perspectives and kind of put things into a like a, like a sort of jigsaw puzzle, putting the pieces into where they need to go. She never tells me the answers but guides me, prompts me to look further than what I can see, makes me go a bit further. S-Pat

This narrative illustrated that PE-Cathy’s non-judgmental attitude enabled S-Pat to feel safe enough to explore her thoughts without fear of embarrassment or assessment in reflective discussion. However, S-Pat explored how collaborative reflective discussion facilitated the development of her knowledge and skills as PE-Cathy ‘makes me go a bit further’. The phrase ‘she helps me’ is important, as it showed that S-Pat developed with PE-Cathy’s support, which is reinforced by ‘guides me, prompts me’, however ‘she never tells me the answers’ revealed that she still had to determine the final solution. This was considered collaborative because it was neither PE-Cathy giving S-Pat the answers nor S-Pat working alone to determine the answer. S-Pat valued the collaborative approach by PE-Cathy which stimulated her learning and expanded her initial prioritizing of skill development, to ensure that she developed both her knowledge and her skills. Her learning was enhanced because they worked together within supervision and S-Pat was asked to consider beyond her own thinking, as is illustrated in the supervision transcription extracts below.

Supervision transcript

S-Pat: I went to see [service user SU5.1], she’s making good progress. In the original assessment, her communication skills were questioned, and she would lose track of the conversation, but actually throughout the conversation on Friday, she was, it was all her that was talking, and her husband was there to support her, but she did all the communicating, she was able to understand … {case detail} … So I just said it’s your package of support, if you don’t want it, or feel that you are using the evening call for what you want it was put there for, then it’s entirely up to you, if you’d like to.

PE-Cathy: So she explained what happens, what help she gets, what the husband does … and would there be anything that would make you worry about taking that out, or changing anything?

S-Pat: No

PE-Cathy: What might be going on for you to worry about that?

S-Pat: … I think if her husband wasn’t there, or providing the support that he was, then I’d be a bit mm, is that a wise decision to take that out. … But also herself, she felt she could manage. If she’d been like I don’t want them to come, but I don’t know how I’m going to get dressed at night, then I’d’ve been a bit like, are you sure?

In this supervision transcript, S-Pat was able to update PE-Cathy on the work undertaken with the service user since the last social work student supervision. Whilst PE-Cathy valued S-Pat by listening to her description of the work, in her second, open question, PE-Cathy asked S-Pat to think beyond her initial presentation, using the opportunity to develop S-Pat’s reflection on the situation further, thus advancing her understanding of possible future interventions. This was an important element of the collaborative student supervision that students began the discussion, which was furthered by questions designed to stimulate discussion and the development of knowledge and skills using a collaborative approach. Within the supervision, the reflective discussion was observed.

Observational fieldnotes

Quickly a pattern emerges that S-Pat describes the case and talks factually about what is happening. S-Pat’s dialogue is sometimes interrupted by open questions such as ‘what’s your observation … ’ or ‘what would you say’ to stimulate the case discussion. This is then followed by PE-Cathy speaking about what she thinks.

The observational fieldnotes confirm that PE-Cathy facilitated collaborative reflective discussion where S-Pat took the lead with input from PE-Cathy which ‘helps me to weigh things up from both perspectives’. This was replicated across other research participants’ narratives.

Student narrative

‘PE-Tim asks me what I think and then we talk about it. He gives me advice on how to do stuff.

INT: Does that work for you?

Yeah, like, I need that help’. S-Sharon

S-Sharon reflected that PE-Tim asked her ‘what I think’, which enabled her to take the lead in the planning discussion where they ‘talk about it’ in relation to her caseload interventions. However, this was supplemented by S-Sharon valuing that her suggestions were developed through discussion and that her understanding was supplemented with PE-Tim’s practice wisdom as he ‘gives me advice’. Furthermore, S-Sharon attributed value to the collaborative nature of the planning, ‘I need that help’. S-Sharon’s narrative illustrated that she perceived that planning with PE-Tim enhanced her preparation for practice and, although not explicitly stated, implied that it enhanced her practice. PE-Tim reflected on how this was undertaken.

Practice educator narrative

What I consciously do with S-Sharon is make her think of the ideas, that she needs to think about what needs to happen, that that is really important, rather than just giving the answers and the solutions. Because we don’t have all the answers and solutions. I think going in as the supervisee, you almost expect that person to know everything, and say I don’t know what to do, well I don’t know what to do either, let’s figure it out together. You know this family; you give some ideas. So I think concentrating on reflective supervision is the most important aspect. PE-Tim

This narrative illustrated that PE-Tim made a ‘conscious’ choice to support S-Sharon in ‘reflective supervision’. PE-Tim provided reflection that he undertook this due to a belief that he and S-Sharon should ‘figure it out together’ rather than S-Sharon being told what to do. Here he explored the importance of a collaborative approach that stimulated S-Sharon to ‘think’ to develop her own understanding of the situation and resolution for her practice. The approach reflected upon by PE-Tim and S-Sharon was noted within my observational fieldnotes in relation to this supervision.

Observational fieldnotes

PE-Tim took a clear strategy to ask S-Sharon what she thought first every time before enhancing it with his thoughts. He used phrases such as ‘why do you think that is’ and ‘how do you feel about … ’ to stimulate her reflection.

The observational fieldnotes also provided examples of open questions that were used to facilitate the collaborative reflective discussion. Open questions are seen to be an important part of developing understanding within social work communication as they enable exploration of a situation (Beesley et al., Citation2018). Open questions allow the recipient to construct their own understanding and response, often using how, why, or what to stimulate discussion. Within social work student supervision, open questions were observed to have been used to facilitate reflective discussion and stimulate students’ reflection on experiential learning, which further developed their knowledge and skills.

This was supplemented by practice educators providing information, procedural knowledge, theoretical input and practice wisdom to enhance student knowledge.

Supervision transcription

PE-Frances: I think what will be really interesting is that when you observe panel, you get to go into the room before panel happens, so you get to see the discussions.

S-Flolella: Are they going to do a check in? (laughs)

PE-Frances: I don’t know, they might do a check in. … They will have the paperwork and they will sit and talk about each case. ‘I’m wondering how this will work’ or ‘I don’t understand this bit of the story’. And because they all come from different backgrounds, they all pick up different stuff.

S-Floella: Oh, interesting

PE-Frances: So, it’s really interesting listening to their discussions. … So, it’ll be interesting to hear from you afterward what’s coming out. And some of the adopters are really nervous, when they come in to answer questions. You’ll see some interesting body language in there (both laugh).

This supervision transcript illustrates PE-Frances preparing S-Floella for an upcoming observational visit to adoption panel by sharing her practice wisdom so that S-Floella knows what to expect and feels more confident attending.

Finally, it was important that students felt able to explore different opinions and disagree with practice educators.

Student narrative

(laughs) Coz I always say to him, well I disagree with that and we come from very different lives, so we can think from different perspectives. S-Marion

S-Marion was also able to identify that she voiced her thoughts and ideas, even when they did not coincide with PE-Phil’s. Her narrative that ‘we can think from different perspectives’ indicated that disagreement was acceptable within her supervisory relationship. This was an important point, as it enabled her to explore her understanding of a concept to develop her knowledge and skills. This supported previous research in which collaborative work that neither completely agrees with, nor dismisses, each other’s ideas is the most productive in enhancing development (Kuusisaari, Citation2014), albeit about student-teacher mentoring. This was observed in supervision.

Supervision Transcript

S-Marion: It’s not my decision, you know they are looking at homes near them, because they’ve made that decision and they don’t want to keep her there. … And not to say that I agree or disagree, but that’s what I’d do as well, but it’s just like … I’d be forget that one because they’ve been so rude, let’s just get her nearer. (laughs)

PE-Phil: But should it be a decision that’s about making it easier for them or her?

S-Marion: I think it will benefit her more if she is closer to her family because the grand kids will be able to go and see her, they will be able to take her out, it’ll take stress off of them, so they will actually go and visit her, so I am thinking about her.

PE-Phil: But if she stayed locally, she’d still be in a place where they could come and visit, she could go to the shops where she knows people.

S-Marion: But she wouldn’t though, because she can’t anymore.

PE-Phil: Well, she would if somebody went with her …

S-Marion: Mm … There you go, we disagree. (both smile at each other)

PE-Phil: Right, so you put this in your reflection …

In this supervision transcript, S-Marion and PE-Phil had different value-based opinions that enabled them to each justify their position. They were able to disagree but hear each other’s opinion without the supervisory relationship deteriorating, as indicated by their smiles when S-Marion pointed out that ‘we disagree’. Finally, PE-Phil suggested that S-Marion used the discussion as a basis for a reflection, an assessed academic requirement, which indicated that he viewed the discussion as a developmental ethical debate with the reflection on different opinions as equally as important as the final decision. In effect, the disagreement served to develop her knowledge and skills.

In conclusion, the use of reflective discussion in supervision was considered in practice educator and student research participants’ narratives.

Practice educator narrative

it is a partnership. It’s about, it’s about … er … that sort of coming at it equally, acknowledging you know that I have sort of knowledge that I have that sort of more power as somebody who’s the educator and that got the experience and all that stuff, but you know in terms of her developing, you know, she’s doing it and she comes to me. PE-Phil

Student narrative

She lets me take the lead. I give her information from my cases and propose what I might do next. Then she will ask me questions that explore what I’m doing and why I might be thinking that way. I find it really good because she pushes me. S-Henry

These narratives illustrated that research participants valued a collaborative approach of reflective discussion, where students were expected to be responsible for their own development by resolving problems with support and the stimulation of the practice educator.

Discussion

The practice educator and student research participants’ narratives, supervision transcript excerpts and observational field notes illustrated that reflective discussion enabled students to engage collaboratively and proactively to develop their knowledge and skills in social work student supervision. This was based on pre-supervision preparation by both participants that enabled both practice educator and student to participate effectively and efficiently, mirroring recommendations by Gardiner (Citation1988), Davys and Beddoe (Citation2009) and Kadushin and Harkness (Citation2014) that recommend that both supervision participants prepare for supervision. The practice educator and student research participants valued reflective discussion that enabled students to take the lead in the supervisory discussions. This was supplemented by practice educators asking open questions that stimulated the development of knowledge and skills enabled students to ‘go a bit further’.

Within this study preparation was identified as important to facilitate social work student supervision as it enabled efficient discussions that were based on prior understanding or knowledge that had been developed within the preparation. It was considered that both practice educators and students benefitted from undertaking the preparation, as preparation was seen to be impactful throughout social work student supervision. Supervision is a relatively short activity, usually an hour and a half long, but often with a long agenda and much to discuss. Previous research has identified that students value structure within social work student supervision (Lazar & Eisikovits, Citation1997; Roulston et al., Citation2018) and the importance of structure to keep it focused and efficient (Miehls et al., Citation2013). This research identified that where participants had prepared and were aware of the pertinent information and knew what they wanted to ask or discuss, supervision was more efficient and effective.

Efficient meant that the social work student supervision was based on an understanding of priorities to facilitate focused discussion that met students’ learning needs and came from a basis of knowledge that enabled informed reflective discussion and learning activities to develop students’ knowledge and skills. This was exampled where my observational fieldnotes reflected that the pre-supervision preparation undertaken by PE-Lena and S-Karen created ‘a sense of purpose, order, and direction’. Where supervision was efficient, it enabled more opportunity for the development of knowledge and skills and was therefore considered to be effective. This reflects the andragogical principles that students are self-motivated and orientated learners (Knowles, Citation1973). In turn, pre-supervision preparation also contributes to the issue of differential power within the supervisory relationship, as if the supervisory participants are prepared, they are both able to contribute.

The practice educator research participants saw themselves as the facilitators of learning, who used open questions to stimulate the development of knowledge and skills. PE-Tim made a ‘conscious’ decision to ‘figure it out together’ in ‘reflective supervision’. It was considered important that practice educators empowered students to first express their thoughts, opinions, and perspectives before open questions were asked to further stimulate discussion and finally practice educators shared their practice wisdom. Furthermore, it was considered within this that practice educators were ‘not judgmental’ (S-Pat) to facilitate a safe space to explore their development of knowledge and skills. This mirrors previous research undertaken by Lazar and Eisikovits (Citation1997) who found that Israeli social work students preferred a practice educator who balanced both direction and independence.

In addition, this research identified that practice educator and student research participants alike valued an actively participant student in social work student supervision, aligning with one of the andragogical principles that students take responsibility for their own learning (Knowles, Citation1973). However, this research developed this further and identified that it is only through being proactive that students can fully and collaboratively engage in social work student supervision, mirroring previous research that identified the importance of both participants being able to express their perspectives to explore a situation (Brodie & Williams, Citation2013). Nevertheless, student research participants reflected that they needed to feel safe to explore their ideas and ask questions to seek help or further information, which they noted as receiving non-judgmental responses that encouraged further participation. Interestingly, students are required to participate in weekly social work student supervision to successfully complete the placement, so do not have a ‘choice’, making it a compulsory relationship (Lofthouse & Thomas, Citation2017). However, students do have a choice as to their level of engagement and participation with the learning activities within social work student supervision. Whilst the power dynamic can never be irradicated, collaborative experiential learning that empowers students to engage can be seen to be a positive step to reducing it. Collaboration is more than one participant working in partnership to enhance outcomes. When related to social work student supervision, collaboration is the participation of both practice educator and student. This is important as the research participants highlighted that reflective discussion should be undertaken together to facilitate students’ development of their knowledge and skills within experiential learning.

Recommendation

This research identified the importance of both practice educator and student making diligent and collaborative contributions to reflective discussion in social work student supervision, which led to the formation of a model for collaborative experiential learning (CEL) in social work student supervision, , below. The model illustrates the importance of both individual reflection prior to supervision and collaborative, reflective discussion in supervision, where both practice educators’ and students’ proactive and collaborative participation contributes to the development of students’ knowledge and skills.

Figure 2. The model of collaborative experiential learning (CEL) in social work student supervision.

The research participants narratives identified diligent preparation in the form of pre-supervision reflection by both practice educator and student. Of note was that this included pre-supervision reflection on interventions both before they happened and after they happened. It is therefore recommended that both practice educators and students reflect on, and utilize social work theory and models of intervention to understand, how a learning activity will be undertaken to enable a reflective discussion in supervision to ensure students are clear of the expectations of the intervention, which gives confidence to engage the service user. Effectively, this is enhancing their knowledge base to facilitate their skill development. Similarly, preparatory individual reflection and application of theory to practice after an intervention is recommended to enable effective collaborative, reflective discussion within social work student supervision that facilitates and enhances the development of students’ knowledge and skills.

In contrast to the wealth of knowledge in relation to individual reflection, there is a smaller body of knowledge in relation to reflective discussion within social work student supervision. Whilst Davys and Beddoe (Citation2009) developed existing theories to suggest a reflective learning model for social work student supervision, this remains untested. Instead, this research study provided evidence-based understanding of a pattern of collaborative, reflective discussion within social work student supervision both before and after a learning activity that can be seen in the model of collaborative experiential learning in social work student supervision (). It illustrates the importance of collaborative turn-taking so that students are enabled to share their ideas and reflections. PE-Cathy and S-Pat’s supervision discussion provides a representative example of a collaborative reflective discussion within social work student supervision. Students’ understanding of social work knowledge and skills is established by their sharing of their reflections. It is here that the importance of students’ diligent pre-supervision reflection is identified, as without it, students’ initial contributions will be limited thus restricting the foundation upon which to develop reflective discussion. Students’ initial reflections enabled practice educators to develop students’ ideas further through the use of both open questions to develop understanding and practice wisdom to develop knowledge. Again, diligent pre-supervision preparation here aids practice educators’ collaborative contributions as it enables effective, knowledgeable, and student-centered contributions that engage the student successfully. This includes where practice educators have understanding of students’ evidenced strengths and areas for development within the learning activity, understanding of students’ learning style and needs, knowledge of the social work theories and values that impacted students’ learning activity, and identified solutions that will aid the student to develop future knowledge and skills.

However, students need to remain diligently engaged in the collaborative, reflective discussion, as they are not being told the answers but instead supported to elaborate on their initial reflections and identify enhanced knowledge which can be applied to their social work skill development. This research identified the importance of a safe supervisory relationship that enabled students to both ask question for clarification and disagree with practice educators’ ideas to develop their own knowledge and be met with a non-judgmental response from the practice educator. Finally, practice educators and students collaboratively plan the next intervention which enables students to both practice their newly developed social work knowledge and skills and to develop more social work knowledge and skills through further experiential learning.

The model of collaborative experiential learning provides a new understanding of how the combination of diligence and collaboration enhances both participants’ ability to engage in reflective discussion that contributes to the development of knowledge and skills in social work student supervision. It is hoped that this model can be used in a wide variety of practice placements, provisional to an ability to engage in active experimentation.

Author agreement statement

I declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before, and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

I could not have carried out this research without the research participants, and I thank them for their time and openness to my intrusion into their social work student supervision. As this research project was part of a doctorate thesis, my gratitude goes to my PhD supervision team.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [email protected], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paula Beesley

Paula Beesley is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work and Academic Practice Lead at Leeds Beckett University, Practice Educator and lead-author of Developing your Communication Skills in Social Work (2018), author of Making the Most of Your Social Work Placement (2020) and co-author of Practice Education in Social Work (2023). Her teaching interests include communication skills and placement modules. She has combined the two areas and to undertake doctorate research to explore what contributes to the development of knowledge and skills in social work student supervision. She is a member of the Practice Education stream of the Leeds and Wakefield Social Work Teaching Partnership.

References

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1974). Theory in practice. Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

- BASW. (2018). Professional capability framework. https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/pcf-strat-social-worker.pdf

- Beesley, P., Watts, M., & Harrison, M. (2018). Developing your communication skills in social work. Sage.

- Bogo, M. (2010). Achieving competence in social work through field education. University of Toronto Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brodie, I., & Williams, V. (2013). Lifting the lid: Perspectives on and activity within student supervision. Social Work Education, 32(4), 506–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.678826

- Connelly, F., & Clandinin, D. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Davys, A., & Beddoe, L. (2009). The reflective learning model: Supervision of social work students. Social Work Education, 28(8), 919–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470902748662

- Fook, J. (2015). Reflective practice and critical reflection. In J. Lishman (Ed.), Handbook for practice learning in social work and social care: Knowledge and theory (pp. 450–454). Jessica Kingsley.

- Gardiner, D. (1988) Teaching and learning in social work practice placements: A study of process in professional education and training. University of London: EThOS. British Library EThOS: Teaching and learning in social work practice placements : a study of process in professional education and training (bl.uk).

- Hair, H. (2014). Power relations in supervision: Preferred practices according to social workers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 95(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2014.95.14

- Ingram, R. (2021). Emotionally sensitive supervision. In K. O’Donoghue & L. Engelbrecht (Eds.), The routledge international handbook of social work supervision (pp. 462–471). Routledge.

- Kadushin, A., & Harkness, D. (2014). Supervision in social work. Columbia University Press.

- Ketner, M., Cooper-Bolinskey, D., & VanCleave, D. (2017). The meaning and value of supervision in social work field education. The Field Educator, 7(2), 1–18.

- Knights, S. (1985). Reflection and learning: The importance of a listener. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Turning experience into learning (pp. 85–90). Routledge.

- Knowles, M. (1973). The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf Publishing.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Prentice-Hall.

- Kuusisaari, H. (2014). Teachers at the zone of proximal development: Collaboration promoting or hindering the development process. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 46–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.06.001

- Lazar, A., & Eisikovits, Z. (1997). Social work students’ preferences regarding supervisory styles and supervisor’s behavior. The Clinical Supervisor, 16(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v16n01_02

- Litvack, A., Bogo, M., & Mishna, F. (2010). Emotional reactions of students in field education: An exploratory study. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(2), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900007

- Lofthouse, R., & Thomas, U. (2017). Concerning collaboration: Teachers’ perspectives on working in partnerships to develop teaching practices. Professional Development in Education, 43(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2015.1053570

- Mason-Bish, M. (2019). The elite delusion: Reflexivity, identity and positionality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 19(3), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118770078

- Mercer, J. (2007). The challenges of insider research in educational institutions: Wielding a double-edged sword and resolving delicate dilemmas. Oxford Review of Education, 33(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980601094651

- Miehls, D., Everett, J., Segal, C., & du Bois, C. (2013). MSW students’ views of supervision: Factors contributing to satisfactory field experiences. The Clinical Supervisor, 32(1), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2013.782458

- Rankine, M., Beddoe, L., O’Brien, M., & Fouché, C. (2018). What’s your agenda? Reflective supervision in community-based child welfare services. European Journal of Social Work, 21(3), 428–440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9780429200069-9

- Rawles, J. (2020). How social work students develop the skill of professional judgement: Implications for practice educators. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 17(3), 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1921/jpts.v17i3.1445

- Roulston, A., Cleak, H., & Vreugdenhil, A. (2018). Promoting readiness to practice: Which learning activities promote competence and professional identity for student social workers during practice learning? Journal of Social Work Education, 54(2), 364–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1336140

- Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Warren, C., & Hackney, J. (2000). Gender issues in ethnography. Sage.

- Wilson, E., & Flanagan, N. (2019). What tools facilitate learning on placement? Findings of a social work student-to-student research study. Social Work Education, 40(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1702636