ABSTRACT

Although, arguably, the origins of social work in the UK have been closely aligned to community development in the past few decades, social work has occupied a bureaucratic landscape focusing primarily on individual risks and needs, leading to both fields drifting further apart. Dismantling of shared values and practices was fueled by layers of government policy and legislation, driven by a neoliberal agenda and public management reforms. However, a horizon of hope emerged when university staff in Social Work and Community Development Departments in Northern Ireland were approached to examine the need to reintroduce community development principles and practices into social work training. This paper aims to trace the development of a post-graduate diploma in community development approaches for professional social workers and analyses research that explores community development as the essence of social work. The programme was developed through a synergistic partnership between university, health trusts and the professional awarding body. Tracking 4 years of programme delivery, the paper highlights the effectiveness of, and learning from, collaboration between the two professions at strategic, technical, and operational levels. We posit here well-learned lessons for future collaborations and make recommendations providing a route map to mainstreaming community development in social work practice.

Introduction

Social work and community development are two distinct disciplines with their own professional associations, practice guides and historical developments; however, there are strong connections between the two. This article takes the position of Lathouras (Citation2016) who argues that collective approaches to social work practice are central in the pursuit of social justice and human rights and that to target systems of poverty, exclusion, and disadvantage, it is vital that work is community-led, moving beyond a local focus to effect social change. This ethos has been implemented throughout the development of a post-graduate diploma in community development approaches for professional social workers in Northern Ireland, enabling critical reflection and action derived from approaches, policy, theory, and models, promoting collective action across both disciplines.

Although the synergies between social work and community development in the UK were closer in the 1970s finding common ground in social action (Seed, Citation1973), authors such as Filliponi (Citation2011) and Popple (Citation2012) contend that social work and community development have become diametrically opposed. As discussed by Mendes (Citation2009), social work has been perceived by community workers and community development educators as supporting individuals and families to fit within current unequal systems rather than adopting a grassroots approach to initiate change, proposing that community development is positioned as radical, while social work has adopted a more conservative approach to practice. Whilst social work is built on the principles of social justice, human rights, and empowerment, neoliberal reforms and the roll out of managerial practices in public services since the 1990s have seen a shift in practice toward concepts of risk management, standardization, fragmentation, and accountability (Ferguson, Citation2008; Harlow, Citation2003; Parton, Citation2008). The growing dominance of such approaches in social services has led to a significant increase in paperwork and procedural compliance, constraining the application of professional expertise and discretion (Harlow, Citation2003; Harris & Unwin, Citation2009; Jones, Citation2001; Munro, Citation2011). It has been argued that form filling and data collection to comply with policies and procedures have predominated over relational and contextual approaches (Munro, Citation2011; Parton, Citation2008). Neoliberal driven managerial reform has caused ethical stress in practitioners, as the individualizing of problems and risk averse culture are contradictory to core social work values (Fenton, Citation2020).

Despite the growth of holistic and person-centered practice approaches and theoretical frameworks including the strength perspective (Saleeby, Citation1996, Citation2013), relationship-based practice (Ruch, Citation2005; Trevithick, Citation2003), and systems theory (Forder, Citation1982; Walker, Citation2012), the political and policy context has resulted in social work practice becoming largely driven by defensive and neo-liberal practices where a focus on risk assessment has occurred in response to serious case reviews and criticisms of the profession (Turbett, Citation2020). Although case management reviews can help develop a culture of critical reflection, prompt system improvement and contribute to professional development, Reder and Duncan (Citation2004, cited in Lazenbatt et al., Citation2009) suggest that the many inquiries into fatal child abuse cases have contributed to a blame culture in child protection work (see also Munro, Citation2004)

The community development ethos and profession, on the other hand, promotes a macro-collective radical agenda, finding creative dialogues and spaces where people are encouraged to engage in a process of conscientisation through active participation, thus providing a springboard to promote social transformation. While the aspirations are similar between the professions, the approaches and methods can be different. Community development encourages an inclusive approach that builds upon the strengths and creativity at grassroots level and is unique and stimulating, engendering visionary thinking. Community development has an embedded gene of emancipatory praxis (Beck & Purcell, Citation2020; Ledwith, Citation2020) that aspires to establish freedom from structural, cultural, and political dominations. Community development, however, is not immune to political influences and does not exist within a vacuum (Shaw, Citation2008). The neoliberal shift in policy has also constrained the radical edge through a focus on contracts and service delivery, rather than challenging structural inequalities and dynamics of power. This has been seen in some contemporary community development programmes adopting a more conservative approach which has relied on working within existing socio-political systems rather than promoting radical agendas (Mendes, Citation2009).

As articulated by the Northern Irish Department of Health (DoH, Citation2018a), community development is about collective action for positive social change. It is a long-term process that prioritizes grassroots experiences while enabling communities to set their own agendas, harness their own strengths and resources to challenge unequal power and advocate for social justice, equality, and inclusion. The aim of community development is ultimately social change to ‘improve the quality of their own lives, the communities in which they live and societies of which they are a part’ (DoH, Citation2018a, p. 6). However, the policy landscape is beginning to shift, with an ameliorative focus to fuse the complementary values of the two professions (British Association of Social Workers [BASW], Citation2021; CLD Standards Council Scotland, Citation2015). There is a necessity for a critical review and update of the Northern Ireland Social Care Council [NISCC] (Citation2019) Standards of Conduct and Practice to integrate community development within Northern Ireland social work practice and move beyond the narratives of individual casework and risk management. Although the Standards refer to the international definition of social work, there is a lack of follow-up integration with minimal reference to community, with the focus instead on ‘service users’ and ‘carers’ (NISCC, Citation2019).

The connection between social work and community development can also be seen in the shared values evident in the professional international definitions. Both social work and community development are practice-based professions and academic disciplines which promote social justice, human rights, and the empowerment of people (International Association of Community Development [IACD], Citation2018; International Federation of Social Work [IFSW], Citation2014). While the international definition highlights how social work ‘engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing’, at a local, regional, or international level (IFSW, Citation2014), the international definition of community development also promotes engagement with people and structures through communities ‘whether these be of locality, identity, or interest, in urban and rural settings’ (IACD, Citation2018). Although the social work definition identifies social change as a key purpose of the profession, the community development definition goes further to incorporate participative democracy, sustainable development, and economic opportunity. This aligns with the Community Development National Occupational Standards (CDNOS) (All Ireland Endorsement Body [AIEB], Citation2016; CLD Standards Council Scotland, Citation2015). The connection between social work and community development is further highlighted in the BASW Code of Ethics (Citation2021) which outlines the importance of social workers engaging in social and political action to influence policy and development, while working in partnership with communities and demonstrating a commitment to the values of human rights and social justice. Tensions continue to exist between the two disciplines, with social workers and community development practitioners engaging in different spaces, applying different approaches and receiving varying levels of professional recognition. Reinforcing Lathouras (Citation2016) position advocating for collective approaches to radical social work, this article argues that enhancing the synergies between the two professions through shared knowledge, skills and practices will facilitate both individual, family, and community empowerment (Mendes, Citation2009). The social work and community development approaches programme (SWCDA) bridges the gap in social work education on community development.

Marginalisation of community development in social work

There are several factors that have contributed to the marginalization of community development in social work from 1980’s in the United Kingdom (Das et al., Citation2016), including the impact of managerialism, neoliberalism, and the increasing procedural and legalized bureaucratic state services.

Both managerialism and neoliberalism promote the idea of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in the provision of social care through marketization and performance measurement, bureaucratizing social work practice and changing and challenging its relationship with individuals, groups, and communities (Forde & Lynch, Citation2015). Despite the values that underpin such reform being contradictory to the foundations and purpose of social work (Harris & Unwin, Citation2009; Tsui & Cheung, Citation2004), managerialism and neoliberalism have re-shaped practice (Harlow et al., Citation2013), and marginalized community development (Aimers & Walker, Citation2011). The role of the social worker has become increasingly fragmented, technical and managerial, shifting to needs assessments and coordinating services (Harlow et al., Citation2013), creating a distance from direct work with individuals who use services and communities. While this shift occurred across all fields of practice in the UK, the closed professionalism has been exacerbated by the experiences of ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland (Houston, Citation2008), with a few notable exceptions (Duffy et al., Citation2019; Heenan & Birrell, Citation2011).

The dominance of neoliberal social policies overshadows the importance of addressing societal or institutional levels of oppression by placing emphasis on individualism. When an individual or group succeeds in overcoming oppression and systematic inequalities, the celebration of their achievement or resilience is often placed above the importance of addressing unjust barriers (Lathouras, Citation2016). While social justice is about empowering and improving the circumstances of whole communities (Ife, Citation2013), focusing attention on the individual can lead to social workers overlooking the wider contextual or macro-level issues, further marginalizing community development approaches in practice.

Bogues (Citation2008) highlighted that social workers were frustrated with paperwork over people work, a recurring theme picked up by professional social work associations and national regulatory bodies alike. In a study surveying 1,691 social workers in the North and South of Ireland, bureaucracy, excessive paperwork, and insufficient time face-to-face with service users were identified as key causes of dissatisfaction (BASW NI, IASW, Northern Ireland Social Care Council & Coru, Citation2020). The report argues that these factors could be addressed, although decisive leadership would be required for meaningful change. Considering the impact procedural legalized bureaucratic state services have had on direct service user engagement, wider community engagement has proven even more problematic for social workers.

Neoliberalism finds expression through the widely adopted term ‘service user’ which promotes a contract culture and the individualization of challenges, minimizing mandated intervention by assuming people wish to engage with services. McLaughlin (Citation2009) has raised a thorough critique of the term ‘service user’ contending that it denies the intersectionality of identity whilst promoting a homogenous population. The term has effectively erased opportunities and spaces for acknowledging that the individual is an active citizen and entrenches the divide between those who have access to services and those who are denied (McLaughlin, Citation2009). Throughout the remainder of this article the term ‘individuals with lived experience’ is used, deconstructing the dichotomy of provider and receiver, privileging their strengths, insight, knowledge and skills. Aligning with Freirean's emancipatory pedagogy (Hawthorne-Steele et al., Citation2015) to deconstruct power structures in education, individuals with lived experience should be actively involved in content creation and co-delivery in social work education and training, as well as decision-making processes at a programme management level. Moving beyond the critiqued contract culture associated with service user (McLaughlin, Citation2009), using the terminology ‘individuals with lived experience’ is more than a tokenistic gesture, rather it recognizes the role individuals have in contributing to their own learning and the learning of others. Regularly reviewing the development of terminology, however, is essential to understand the ongoing contested nature of titles, labels, and structures in practice.

Context of Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19)

In the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a resurgence of community development across the social work profession. Informed by social workers’ reflections on practice during the pandemic, Truell and Crompton (Citation2020) argue that where social work has predominantly focused on crisis management, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of early intervention and prevention which is at the heart of community-based social work. This can be seen in initiatives such as building collaborative relationships across agencies to ensure the provision of immediate basic needs such as food and housing (Redondo-Sama et al., Citation2020), personally delivering food, water, and other essentials to vulnerable populations, compiling databases of volunteers, and advocating for the importance of a social response in Government plans (Truell & Crompton, Citation2020).

More broadly, the role of social workers in disaster management has included the establishment of new planning frameworks or protocols for emergency management and disaster response efforts, establishing information centers to reunite patients and families (Maher & Maidment, Citation2013), one-off community workshops or protests (Pyles, Citation2007), and advocating for the extension of support services to address long-term recovery (Hay et al., Citation2021).

Ornellas et al. (Citation2020) contend that the global impact of neoliberal economics on the day-to-day practices of social workers is fourfold in terms of the marketization, consumerization, mineralization and de-professionalization of social work. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis and beyond, the devastating impacts of an individualized, cost-effective, and business-driven social work profession are impossible to ignore. As professionals, social workers need to critically reflect on how they may be, unknowingly, promoting a neoliberal discourse and economy-centric values, and recognize the direct contradictions these hold for the mandate of the social work profession.

Northern Ireland context

While community development is practiced throughout the UK, it did not develop along the same lines in Northern Ireland, as social work practice was considered high-risk during ‘The Troubles’ and ensuing sectarian divisions (Heenan, Citation2004). There have been contrasting perspectives on the relationships between social work and community development in Northern Ireland during this time. Pinkerton and Campbell (Citation2002) suggested that during ‘The Troubles’, social work in Northern Ireland formed a detachment from communities and saw diminished engagement with civil society to develop a nonsectarian identity, creating a closed profession where distance from the community was maintained. They argued that this resulted in the delay of anti-sectarian approaches and de-politicized social work with an emphasis on client-based work (Pinkerton & Campbell, Citation2002). As claimed by Heenan and Birrell (Citation2011, p. 77), although social workers remained distant from conflict and sectarian debate, they were ‘forced to deal with the consequences of violence and intimidation, acknowledging that priorities would have to change’, but a large-scale shift toward community development was not forthcoming.

In contrast, Duffy et al. (Citation2019) contend that innovative community development approaches flourished during ‘The Troubles’. They state that, just as the peace process in Northern Ireland depended on a capacity for dialogue, so too were social workers required to navigate new relationships between their practice, the contested State and civil society groups. Much has been written about the challenging, risky and abnormal spaces that social workers and community development workers occupied during ‘The Troubles’, including negotiating with paramilitary groups in the absence of ‘normal’ policing and legal structures (Campbell et al., Citation2021; Kilmurray, Citation2017; Morrow, Citation2018).

The reemergence of community development in social work in Northern Ireland

In recent years there has been a re-emphasis on community development approaches and co-production in health and social work in Northern Ireland. Underpinning these approaches is the belief that local communities can organize to address health and social needs and to work with government agencies, voluntary bodies, and local authorities in delivering services and local solutions to problems. These methods of working challenge the current predominant focus of social work utilizing individual and family casework interventions. The DoH has stressed that community development should no longer simply be an afterthought in key aspects of health and social services but should instead be at the core of their work (Heenan, Citation2004). Innovative co-production methods (DoH, Citation2018c) have helped shift the notion of professionals as experts to recognizing the skills, capabilities and knowledge of individuals, families and communities, derived from their lived experiences. This encourages an equal partnership in processes of co-design for developing shared solutions.

Following the publication of Delivering Together (DoH, Citation2017), primary care multi-disciplinary teams were established across Northern Ireland as part of a plan to deliver more services in the community to alleviate secondary care pressures with an ageing population who have more chronic health conditions. A commitment to resource community development is evident in the policy statement: ‘It will take time to realign and grow the community development resource, and as a first step we will review existing capacity and then invest to meet any gaps, including a programme of training’ (p. 12). Furthermore, social workers in these teams have been strongly recommended to undertake post-graduate training in community development.

Other policy developments which have influenced the reemergence of community development include Transforming Your Care (DoH, Citation2011), a policy which focused on restructuring services to enhance delivery and promote, amongst other things, community development approaches for building strong resilient communities. Community development approaches, joint working and effective partnerships have also been highlighted in the 2012–2022 Strategy for Social Work (DoH, Citation2012) and, more recently, the Expansion of Community Development Approaches (DoH, Citation2018a) and Co-production Guide (DoH, Citation2018c) have provided a robust policy environment for community development to flourish. The embedded practice of community development has become more visible in social work, exemplified in the proposed Reform of Adult Social Care (DoH, Citation2022).

Community development training

It is recognized that elements of community development are touched on in qualifying degrees as outlined by the practice learning requirement for graduates by the Northern Ireland Degree in Social Work Partnership (2021) but there is no module with an exclusive focus on community development approaches or community-based social work in Northern Ireland. Barron and Taylor (Citation2010) discuss the prospects for improving social work community development learning through relevant practice placements at an undergraduate level and make a recommendation to incorporate community development approaches into post-qualifying social work training. Drawing from the work of Barron and Taylor (Citation2010) and responding to the gaps in provision, the post-graduate diploma in Social Work and Community Development Approaches (SWCDA) programme has been developed and is discussed below, bridging the gap between existing policy priorities and social work practice in Northern Ireland. Despite being marginalized in social work education and practice, community development remains embedded within the youth and community work profession and training, and in health promotion in Northern Ireland (DoH, Citation2014).

Post-graduate diploma in social work and community development approaches

The SWCDA programme was developed to bridge the gap that has emerged between social work and community development. Fusing the similar and complementary values that underpin both practices, as outlined above (BASW, Citation2021; IACD, Citation2018; IFSW, Citation2014; NISCC, Citation2019; CLD Standards Council Scotland, Citation2015), the programme is both academically and professionally accredited and approved by NISCC, the regulatory authority for all social workers in Northern Ireland. Such approval is a key strength of the programme as the checks and balances of NISCC ensure robust content to meet professional social work standards. On successful completion, participants gain a post-graduate Professional in Practice (PiP) specialist award, one of three which social workers can undertake for continued professional development in Northern Ireland. The aim of the programme is to produce competent, effective, and informed social work practitioners capable of working with communities and across professional boundaries, with appropriate organizations and bodies, to develop cross-cutting solutions to complex societal problems. The importance of this programme has been strengthened by the promotion of community development approaches in the most recent social work training strategy (DoH, Citation2019), and the DoH commitment to full funding (see ).

Development of the SWCDA programme

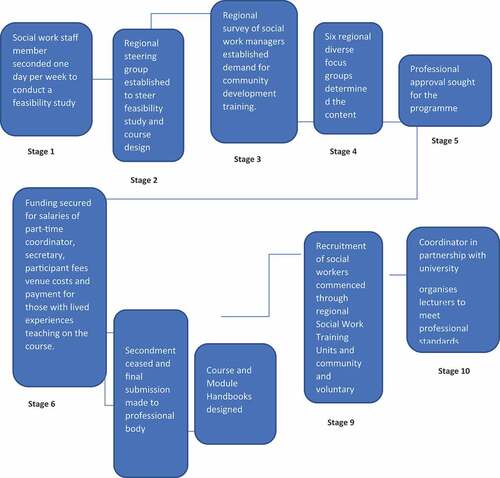

Following initial discussions between university community development and social work departments and a lead health trust, a steering group comprising of academics, social care professionals, NISCC representatives and non-governmental organizations was established. Table 1 depicts the stages in the development of the programme. Extensive consultation and focus groups were conducted with practicing social workers and people with lived experiences to shape the programme. Social workers highlighted the importance of a wide range of principles, models and methods which now feature in the programme including strengths-based social work, co-production, recovery model and family group conferences. There was a strong consensus for significant involvement from individuals with lived experience and the community and voluntary sector, ensuring that these partners be paid the commensurate rate for teaching contributions, that they are represented in the steering group, and that the programme should operate on the basis of working ‘with’ not ‘for’ people. All recommendations have been implemented at teaching and management board levels.

Module content

Shared Understandings-Social Work and Community Development: Participants engage in community development and social work theories, values, principles, and ethics, and examine relevant legislation and policies.

Social Work and Community Development in a Changing and Diverse Society: Participants are introduced to research methods and engage in reviews of international literature relevant to their specialist areas of practice.

Implementing Community Development Initiatives in Social Work: Participants apply theory to practice by implementing a local programme.

The values of participative and emancipatory practice, combined with co-production, partnership, capacity building and a commitment to empowerment underpin all three modules. A key challenge for students is articulating the differences and critically examining the practices of community-based compared with community development approaches (Nel, Citation2018). This questions who sets the agenda—the community or the agency? (for further discussion, see DoH, Citation2018a, p. 8). The case studies that follow exemplify a community asset-based approach which is participatory and inclusive, utilizing existing resources as opposed to focusing on deficits (Nel, Citation2018).

In line with the Community Development National Occupational Standards (CLD Standards Council Scotland, Citation2015) and NISCC (Citation2019) values, the delivery of the programme is collaborative, with practitioners, academics, and people with lived experience providing teaching.

Principle values underpinning the SWCDA programme

The programme is grounded in a Freirean pedagogy that informs the teaching ethos and underpinning professional values (Hawthorne-Steele et al., Citation2021). This manifests in tutors being committed to dialogical learning, promoting consciousness-raising, engaging in problem-posing discussion with each other and with the students, and designing a learning environment which continues to support the central thesis of Freire (Citation1993) who claims education as resistance which is only addressed through critical dialogue.

An essential element of the curriculum is to guide students toward a transformative social change model, by providing opportunities for them to understand why and how to challenge oppression, address social injustice and deconstruct neoliberal policies. According to Lynch et al. (Citation2021), there are three underpinning principles that are core to an exemplary community learning programme: critical, relational, and connected. This programme strives to fulfil these aspirational principles by first being critical through promoting Freirean pedagogy and reflection in summative and formative assignment tasks. An essential element of the programme is the ethos of shared learning achieved through establishing dialogical relationships between teacher and students, employer mentors who offer student supervision and joint assessment of academic assignments. Peer learning through group work and support networks significantly features in the programme. Finally, both within the programme and professional context, connectivity and solidarity between local and global perspectives are enhanced through international research undertaken by students in their specialist areas

The values are evidenced in the student projects aimed at improving social well-being as part of their final assessment. This ranges from social justice, equality and anti-discrimination work with Roma and asylum seekers, to tackling issues of food poverty and social exclusion. Other topical issues have included community empowerment with adults with physical and learning disabilities, tackling isolation in older people, addressing policy gaps in unaccompanied separated and trafficked children, and establishing condition-specific self-help groups. The implementation of local projects has been a visible asset to the programme as this is where intersectionality occurs, and innovative models of community development approaches are located.

Reflection on the impact, challenges, and limitations

The benefits and challenges of social work educational partnerships in Northern Ireland have long been established and documented at undergraduate (Wilson, Citation2014) and postgraduate levels (Taylor et al., Citation2010). The delivery of the SWCDA programme harnesses cross-departmental perspectives from social work and community development academics and through relationships with partners in the field of social work and community development. The genuine commitment to meaningful involvement of individuals with lived experience in the co-design of the programme is a core strength, addressing macro-level challenges with micro-level practice. The partnerships have ensured that real world examples and interagency perspectives are interwoven alongside community development theory and models, bringing the application of community development approaches to life. This further supports critical thinking, to engage in debates pertaining to the tensions between the radical roots of community development and the more contemporary risk focused, case management predominance in social work (Mendes, Citation2009). Employing a teaching module built on shared expertise and differing perspectives (Clifford et al., Citation2002) with inputs from academics, employing agencies, individuals with lived experience and community groups has ensured a balance between ‘training’ and ‘education’ (Taylor et al., Citation2010), helping address the misconception explored by Mendes (Citation2009) that the role of the social work profession is to assist individuals to fit within inequitable systems.

The underpinning principle of partnership and Freirean pedagogy of shared learning is further illustrated through joint ownership from all stakeholders where the programme management board consists of inclusive membership and representation from academic staff, employment partners from statutory and voluntary sectors, the regional professional social work body, and individuals with lived experience. Gordon & Davis (Citation2018, p.3) stress the importance of a ‘shared overarching vision within which partners can voice and negotiate inevitable differences in perspective, and to establish realistic expectations of their roles and the desired outcomes of partnership’. To ensure all voices are heard and equal opportunity for meaningful engagement in decision-making, support and training has been offered before and after management board meetings for people with lived experience who sit on the management board. Embedding support systems for individuals with lived experience are essential to ensure their own agenda is identified, and that any jargon and contextual information are fully understood for inclusive decision-making processes.

Critical reflection has also informed the continuous curriculum development, as academic and agency staff have reflected on their own and student evaluations, to improve the quality of the teaching and learning experience. Grappling with different terminologies and contexts across the social work and community development disciplines, based on the values of collective and cooperative learning, has been an important learning curve for both academic and agency staff. Double marking from agency and academic perspectives, as recommended by Taylor et al. (Citation2010), has contributed to this learning, as well as forging stronger partnership working across the sectors. A further benefit of this model is to ensure a sharp focus on the balance between theory and practice, which Ledwith (Citation2020) contends is critical to community development.

A key challenge in the delivery and maintenance of a high-quality student experience includes supporting candidates in full-time employment to complete assessed post-qualifying studies alongside balancing work, health and family commitments. This has been recognised as a long-standing challenge in the social work profession (Brown & Keen, 2004 as cited in Taylor et al., Citation2010). The support mechanisms put in place to address this challenge include using both supervision from employer mentors, and peer support within and outside the teaching days through WhatsApp groups and group exercises. Deferrals for exceptional cases may be approved to allow an extension of time for completion.

An ongoing annual challenge is changes in employer mentors responsible for staff supervision and assessment. As has been thoroughly explored by Gordon and Davis (Citation2018) social work staff turnover and retention has affected the profession throughout the United Kingdom. This has led to developments in informal relationships which have been critiqued as ‘relying too heavily on the enthusiasm and goodwill of key individuals and established, but easily disrupted, networks’ (p. 3).

In the first 2 years of the programme teaching, management meetings, assessment boards, panels and standardization were carried out face-to-face, sometimes with poor attendance due to the regional nature of the programme and management structures. However, the geographical proximity highlighted by Gordon and Davis (Citation2018)

) as being supportive of good partnership work was mitigated through Zoom and propelled by COVID-19, enabling improved attendance from regional staff at meetings and greater flexibility in teaching.

With hybrid and online education growing across the profession (Robbins et al., Citation2016; Vernon et al., Citation2009), the incorporation of virtual learning platforms is growing; however, this is not without challenges. Although the problems associated with digital inequalities (Authors own) were not a major issue as most candidates had access to IT equipment, there were, however, some variations in the quality of internet connections in rural areas. The problems of accessibility and connectivity were keenly expressed by candidates who could not access the University’s virtual learning platform, Blackboard Learn (BBL), or Microsoft Teams due to security software when working from Health and Social Care Trust equipment. This was resolved by using Zoom, but the software is more burdensome when trying to record and upload to the virtual learning platform. The Trusts have recently announced a move to Microsoft Teams which should alleviate future accessibility issues.

Whilst funding has been provided from the Department of Health, a challenge is that this on a non-recurrent annual basis and in order to ensure that it does not fall off the social work agenda, the programme needs to be mainstreamed within NI post-qualifying provision. The last 4 years have demonstrated a healthy demand, with over 20 applications annually from primary care multi-disciplinary teams and every other social work setting and sector. This is a key indicator of the programme’s viability and sustainability.

Programme outcomes

Between September 2018 and September 2022, of the 101 social workers who had registered for the programme, 74 achieved Specialist Awards, 12 post-graduate diplomas and 6 MScs in professional development. Participants represent a variety of settings, and external examiners have commented on the success of the programme to date, highlighting that it is internationally leading for social work training. The programme’s success is due to the collective efforts of the university’s Community Development and Social Work departments, along with the partner agencies, NISSC and the DoH. To minimize interagency suspicion and ‘siloed’ perspectives, the programme is co-delivered by agency staff from the statutory and not-for-profit sectors and people with lived experience. Effective partnerships have enhanced the programme and have been recognized as a core strength through external review. Building on an earlier vision of Mainstreaming Community Development Approaches (DHSS, Citation1999), the curriculum affords professionals the opportunity to reflect on and challenge the dominant neoliberal agenda, and critically analyze collective goals of tackling inequalities and social injustice while enabling specialist and generic social workers employed in both the public and not-for-profit sector to learn from one another.

A key example that evidences the programme outcomes can be seen in a regional seminar, organized by the SWCDA Regional Coordinator in partnership with NISCC. Attended by 120 social work and social care staff across Northern Ireland, the seminar highlighted a variety of community development approaches across a range of settings from the perspective of social workers and individuals who use services. Effectively demonstrating how learning has been put into practice, presentations were delivered by ex-candidates from the SWCDA programme, discussing the local projects they had implemented as part of module three (NISCC, Citation2020). This recording is now available as an open-access teaching resource. From module three, the projects demonstrate the wide applicability of community development approaches in the social work profession (see NISCC, Citation2020 for a list of projects presented). A follow-up seminar is essential to evaluate and celebrate the impact of community development within multidisciplinary teams who weren’t in post at the time.

Mainstreaming community development in social work has received a major boost in a consultation document on the reform of adult social care Northern Ireland (DoH, Citation2022, p. 63) It comments on the importance of strengthening the capacity of community development in social work practice ‘including community development/community engagement routinely in Health and Social Care Trust adult social work job description … continued support for the newly developed post-graduate social work and community professional development programme’.

Under the Northern Ireland Strategy for Social Work Progress Report, the SWCDA programme is strategically positioned as one of the core factors contributing to improved service-user social wellbeing and developing social workers’ practice (DoH, Citation2018b). This report demonstrates the DoH’s commitment to monitoring the impact of using community development approaches with individuals with lived experiences and practitioners. To further explore programme outcomes, the current authors are planning to develop primary research to assess the impact of the programme on social work practice, and work has begun on developing a regional community development publication with the Department of Health.

Conclusion

The core ethos of social work is to improve the well-being of people, communities, and society, drawing upon the values of social justice, empowerment, collective responsibility, respect for diversity and human rights (IFSW, Citation2014). Yet, over the past 30 years, social work has been overwhelmed by a neoliberal agenda, and dominated by a procedural and managerial focus. Although NISCC has already taken steps towards mainstreaming community development by accrediting the SWCDA programme and supporting a regional seminar on community development approaches, this must be reflected in practice standards. Currently there is predominant focus on ‘service users’ and ‘carers’ in the NISCC Standards of Conduct and Practice (Citation2019), and a critical consideration of terminology is essential. Although community development approaches are promoted in DoH policies, a critical review of the standards is recommended to purposely incorporate the language of community and better align with the BASW (Citation2021) Code of Ethics.

Furthermore, following on from the success of the mainstreaming community development seminar which showcased the student’s final module projects, this paper proposes that a second educational seminar in partnership with NISCC is timely. This should address the impact of Delivering Together (DoH, Citation2017) and the subsequent employment of multidisciplinary teams who are now using community development approaches, many of whom have completed the SWCDA programme. However, it is vital to continue to illustrate examples from across the profession to prevent a perception that only multidisciplinary teams are using community development approaches.

There has been a reawakening of community development approaches in the social work profession, reflected in the DoH local policy developments and regional, national, and international responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Being both academically and professionally accredited, the SWCDA programme is an example of how community development can be mainstreamed into social work practice across a range of sectors and fields, not just in community-based social work posts. Demonstrating that synergies between statutory and not-for-profit organizations can work to create radical transformation through critical pedagogy, the programme has the propensity to create international impact. It is recommended that other higher education institutions adopt and implement the key tenets of this programme.

While the programme works to support social workers in integrating community development approaches in practice, the authors remain critically aware of the challenges of building such a programme within existing systems of power inequalities that perpetuate managerial and neoliberal discourses to the detriment of a radical agenda. The external and internal neoliberal forces are diametrically opposed to Freirean values of emancipatory praxis (Beck & Purcell, Citation2020), and the programme has worked to create space for radical practice through interagency partnerships.

Community development approaches need to be acknowledged as a core element of social work practice, aligning with the definition, values, principles, and ethos of the profession. This requires a paradigm shift from an ameliorative perspective to transformative practice. To avoid the dominance of a statutory agenda, time must be afforded to implement these approaches and be reinforced in job descriptions and service priorities.

The Reform of Adult Social Care consultation (DoH, Citation2022) has recognized the essential role of this programme in mainstreaming community development in social work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fergal O’Brien

Fergal O’Brien is the training and development consultant and programme coordinator for SW/CDA at social services workforce development and training team in the Southern Health & Social Care Trust (Armagh, Northern Ireland).

Isobel Hawthorne-Steele

Isobel Hawthorne-Steele is a senior lecturer in community development at Ulster University.

Katheryn Margaret Pascoe

Kathryn-Margaret Pascoe is a social and community work Lecturer at the University of Otago in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Rosemary Moreland

Rosemary Moreland is a senior lecturer in community development (and programme coordinator of the SW/CDA PG programme) at Ulster University.

Erik Cownie

Erik Cownie is a lecturer in community development at Ulster University.

References

- Aimers, J., & Walker, P. (2011). Incorporating community development into social work practice within the neoliberal environment. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 23(3), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol23iss3id159

- All Ireland Endorsement Body. (2016). All Ireland standards for community work. Community Work Ireland Retrieved August 04, 2023, from https://www.cwi.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/All-Ireland-Standards-for-Community-Work.pdf

- Barron, C., & Taylor, B. (2010). The right tools for the right job: Social work students learning community development. Social Work Education, 29(4), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903079091

- BASW NI, IASW, Northern Ireland Social Care Council & Coru. (2020). Shaping social workers’ identity: An all-Ireland study. Belfast: BASW NI/IASW/Noerthern Ireland Social Care Council/Coru.

- Beck, D., & Purcell, R. (2020). Community development for social change. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315528618

- Bogues, S. (2008). People work not just paperwork: What people told us during the consultation conducted for the NISCC roles and tasks of social work project. Northern Ireland Social Care Council.

- British Association of Social Work. (2021). Code of ethics. Retrieved August 13, 2021, from https://www.basw.co.uk/about-basw/code-ethics

- Campbell, J., Duffy, J., Tosone, C., & Falls, D. (2021). ‘Just get on with it’: A qualitative of study of social workers’ experiences during the political conflict in Northern Ireland. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(4), 1314–1331. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab039

- CLD Standards Scotland. (2015). Community development Occupational standards. Retrieved August 04, 2023, from https://cldstandardscouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/CDNOStandards2015.pdf

- Clifford, D., Burke, B., Feery, D., & Knox, C. (2002). Combining key elements in training and research: Developing social work assessment theory and practice in partnership. Social Work Education, 21(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470120107059

- Das, C., O’Neill, M., & Pinkerton, J. (2016). Re-engaging with community work as a method of practice in social work: A view from Northern Ireland. Journal of Social Work, 16(2), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017315569644

- Department of Health. (2011). Transforming Your Care, a review of health and social care in Northern Ireland. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from http://www.transformingyourcare.hscni.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Transforming-Your-Care-Review-of-HSC-in-NI.pdf

- Department of Health. (2012). Improving and Safeguarding social wellbeing: A strategy for social work in Northern Ireland (2012-2022). Department of Health Northern Ireland.

- Department of Health. (2014). Making life better: A whole system strategic framework for public health (2013-2023). Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/dhssps/making-life-better-strategic-framework-2013-2023_0.pdf

- Department of Health. (2017). Health and wellbeing 2026 – Delivering Together. Department of Health Northern Ireland.Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/health-and-wellbeing-2026-delivering-together

- Department of Health. (2018a). Expansion of community development approaches. Department of Health Northern Ireland.

- Department of Health. (2018b). Improving and Safeguarding Social Wellbeing: A Strategy for Social Work. Progress Report Stage 2.Department of Health. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/health/social-work-strategy-stage-2-progress-report.pdf

- Department of Health. (2018c). Co-production guide for Northern Ireland: Connecting and realizing value through people. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/co-production-guide-northern-ireland-connecting-and-realising-value-through-people

- Department of Health. (2019). A learning and Improvement strategy for social workers and social care workers 2019-2027. Department of Heath Northern Ireland.Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/dhssps/social-work-strategy.pdf

- Department of Health. (2022). Consultation on the reform of adult social Care Northern Ireland. Department of Health Northern Ireland.

- Department of Health and Social Services. (1999). Mainstreaming community development in the health and personal social services. DHSS.

- Duffy, J., Campbell, C., & Tosone, C. (2019). Voices of social work through the Troubles. British Association of Social Workers and the Northern Ireland Social Care Council.

- Fenton, J. (2020). ‘Four’s a crowd’? Making sense of neoliberalism, ethical stress, moral courage and resilience. Ethics and Social Welfare, 14(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1675738

- Ferguson, I. (2008). Reclaiming social work. Challenging neo-liberalism and promoting social justice. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446212110

- Filliponi, R. (2011). Integrating social work and community development? An analysis of their similarities and differences and the effect on practice. Practice Reflexions, 6(1), 49–64.

- Forde, C., & Lynch, D. (2015). Social work and community development. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-30839-9

- Forder, A. (1982). The systems’ approach and social work methods. Social Work Education, 1(2), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615478211220021

- Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed (2nd ed.). Continuum Press.

- Gordon, J., & Davis, R. (2018). Social work in a changing Scotland (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Harlow, E. (2003). New managerialism, social service departments and social work practice today. Practice, 15(2), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150308416917

- Harlow, E., Berg, E., Barry, J., & Chandler, J. (2013). Neoliberalism, managerialism, and the reconfiguring of social work in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Organization, 20(4), 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508412448222

- Harris, J., & Unwin, P. (2009). Performance management in modernized social work. In J. Harris & V. White (Eds.), Modernising social work: Critical considerations (pp. 9–30). The Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t895ct.6

- Hawthorne-Steele, I., Moreland, R., & Cownie, E. (2021). Facing the challenges of creating online critical dialogical spaces for community learning pathways into HE.The Adult Learner. https://www.aontas.com/assets/resources/Adult-LearnerJournal/ALJJ%202022/Adult%20Learner%20Journal%20Call%20for%20Abstracts%202022.pdf

- Hawthorne-Steele, I., Moreland, R., & Rooney, E. (2015). Transforming communities through academic activism: An emancipatory Praxis-Led approach. Studies in Social Justice, 9(2), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v9i2.1152

- Hay, K., Pascoe, K., & McCafferty, L. (2021). Social worker experiences in disaster management: Case studies from Aotearoa New Zealand. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work Journal, 33(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol33iss1id820

- Heenan, D. (2004). Learning lessons from the past or revisiting old mistakes: Social work and community development in Northern Ireland. The British Journal of Social Work, 34(6), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch102

- Heenan, D., & Birrell, D. (2011). Social work in Northern Ireland. Conflict and change. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89bkb

- Houston, S. (2008). Transcending ethno-religious identities: Social work’s role in the struggle for recognition in Northern Ireland. Australian Social Work, 61(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070701818716

- Ife, J. (2013). Community development in an uncertain world: Vision, analysis and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- International Association of Community Development. (2018). Towards shared international standards for community development practice. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.iacdglobal.org/international-standards-accreditation/standards/

- International Federation of Social Work. (2014). Global definition of social work. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work

- Jones, C. (2001). Voices from the frontline: State social workers and new labour. British Journal of Social Work, 31(4), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/31.4.547

- Kilmurray, A. (2017). Community action in a contested society: The story of Northern Ireland. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b10422

- Lathouras, A. (2016). A critical approach to citizen-led social work: Putting the political back into community development practice. Social Alternatives, 35(4), 32–36.

- Lazenbatt, A., Devaney, J., & Bunting, L. (2009). An evaluation of the case management Review process in Northern Ireland. National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

- Ledwith, M. (2020). Community development: A critical and radical approach (3rd ed.). Policy Press.

- Lynch, D., Lathouras, A., & Forde, C. (2021). Community development and social work teaching and learning in a time of global interruption. Community Development Journal, 56(4), 566–586. https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/cdj/bsab028

- Maher, P., & Maidment, J. (2013). Social work disaster emergency response within a hospital setting. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 25(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol25iss2id82

- McLaughlin, H. (2009). What’s in a name: ‘client’, ‘patient’, ‘customer’, ‘consumer’, ‘expert by experience’, ‘service user’, - what’s next? British Journal of Social Work, 39(6), 1101–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm155

- Mendes, P. (2009). Teaching community development to social work students: A critical reflection. Community Development Journal, 44(2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn001

- Morrow, D. (2018). Sectarianism in Northern Ireland: A review. Retrieved August 13, 2022, fromhttps://www.community-relations.org.uk/sites/crc/files/media-files/A-Review-Addressing-Sectarianism-in-Northern-Ireland_FINAL.pdf

- Munro, E. (2004). Improving practice: Child protection as a systems problem. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.11.006

- Munro, E. (2011). The Munro review of child protection: Final report. Department of Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/175391/Munro-Review.pdf

- Nel, H. (2018). A comparison between the asset-oriented and needs-based community development approaches in terms of systems changes. Practice Social Work in Action, 30(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2017.1360474

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019). Retrieved August 13, 2022, from Standards of conduct and practice for social workers.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2020). Mainstreaming community development in social work. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://learningzone.niscc.info/storage/adapt/5fb2909929d6f/index.html

- Ornellas, A., Engelbrecht, L., & Atamtürk, E. (2020). The fourfold neoliberal impact on social work and why this matters in times of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 56(3), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.15270/56-4-854

- Parton, N. (2008). Changes in the form of knowledge in social work: From the social to the informational? British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl337

- Pinkerton, J., & Campbell, J. (2002). Social work and social justice in Northern Ireland: Towards a new occupational space. British Journal of Social Work, 32(6), 723–737. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/32.6.723

- Popple, K. (2012). Community practice. In M. Gray, J. Midgeley, & S. A. Webb (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social work (pp. 279–294). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446247648.n19

- Pyles, L. (2007). Community organising for post-disaster social development: Locating social work. International Social Work, 50(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872807076044

- Reder, P., & Duncan, S. (2004). Making the most of the Victoria Climbié inquiry report. In N. Stanley & J. Manthorpe (Eds.), The age of inquiry: Learning and blaming in health and social care (pp. 92–116). Routledge .

- Redondo-Sama, G., Matulic, V., Munté-Pascual, A., & de Vicente, I. (2020). Social work during the COVID-19 crisis: Responding to urgent social needs. Sustainability, 12(20), 8595–8711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208595

- Robbins, S., Regan, J., Williams, J., Smyth, N., & Bogo, M. (2016). From the editor – the future of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1218222

- Ruch, G. (2005). Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: Holistic approaches to contemporary childcare social work. Child and Family Social Work, 10(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00359.x

- Saleeby, D. (1996). The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work, 41(3), 296–305. https://www.pearson.com/en-us/subject-catalog/p/strengths-perspective-in-social-work-practice-the/P200000001772/9

- Saleeby, D. (2013). Strengths perspective in social work practice (6th ed.). US: Pearson.

- Seed, P. (1973). The expansion of social work in Britain. Routledge and Kegan Paul. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003271451

- Shaw, M. (2008). Community development and the politics of community. Community Development Journal, 43(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsl035

- Taylor, B., Mullineux, J., & Fleming, G. (2010). Partnership, service needs and assessing competence in post qualifying education and training. Social Work Education, 29(5), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903159117

- Trevithick, P. (2003). Effective relationship-based practice: A theoretical exploration. Journal of Social Work Practice, 17(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/026505302000145699

- Truell, R., & Crompton, S. (2020). To the top of the cliff: How social work changed with COVID-19. International Federation of Social Workers.

- Tsui, M., & Cheung, F. (2004). Gone with the wind: The impact of managerialism on human services. British Journal of Social Work, 34(3), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch046

- Turbett, C. (2020). Rediscovering and mainstreaming community social work in Scotland. IRISS Insight 57.

- Vernon, R., Vakalahi, H., Pierce, D., Pittman-Munke, P., & Adkins, L. (2009). Distance education programs in social work: Current and emerging trends. Journal of Social Work Education (Sage, London), 45(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2009.200700081

- Walker, S. (2012). Effective social work with children, young people, and families: Putting systems theory into practice. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446270141

- Wilson, G. (2014). Building partnerships in social work education: Towards achieving collaborative advantage for employers and universities. Journal of Social Work, 14(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017313475547