ABSTRACT

This article presents a detailed history of the development of social work education in Northern Ireland from 1962 to 2020 as a chronology spanning 58 years. Policy mapping was used as a model to build the chronology. A brief examination of the social, political and geographical context of Northern Ireland outlining the distinctive nature of social work in a post-conflict context are discussed. The chronology is presented as a table detailing the development of social work education in Northern Ireland over the last five decades. This culminates in a discussion which highlights some key shifts in policy and practice developments as they relate to social work education in Northern Ireland at pre and post qualifying levels.

Introduction

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed how social work education was delivered in Northern Ireland. This coincided with the first period of civic lockdowns and led to a decision to prematurely end social work placements on the 18th of March 2020. This unprecedented global health emergency required social work practitioners, students, and academics to adapt rapidly and acquire new skills and competencies in the use of digital technologies. These seismic changes also created an opportunity to reflect on the history of social work education in Northern Ireland to this point. This article presents a detailed history of the developments in social work education in Northern Ireland from 1962 to 2020 as a chronology spanning 58 years.

This article begins by briefly examining the social, political, and geographical context of Northern Ireland outlining the distinctive nature of social work in this post-conflict context. Policy mapping as a methodology (Burris et al., Citation2010) is explained as the model used to build the chronology of social work education (1968–2020). Next, the chronology is presented, the author proposes this chronology is an original and significant contribution to knowledge for social work colleagues, academics, practitioners, and students detailing the development of social work education in Northern Ireland over the last five decades. The discussion section briefly highlights some key shifts in policy and practice developments as they relate to social work education in Northern Ireland at pre and post-qualifying levels.

Geographical, political, and social contexts

Northern Ireland experienced civil conflict for over three decades, resulting in people and communities being exposed to significant trauma and injuries (Breen-Smyth, Citation2012; Ferry et al., Citation2008). This period of political and civil unrest was known as ‘the Troubles’ and has been the focus of local, national, and international research (Hamber & Kelly, Citation2018; Kelly & Braniff, Citation2016; Muldoon, Citation2004). The Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement) in 1998 set out a pathway toward reconciliation and a commitment to establishing a fresh start for the people of Northern Ireland. This was approved by 71% of voters in a referendum (Morrow, Citation2019).

The Belfast Agreement (Citation1998) was a milestone in efforts to resolve the ongoing conflict in Northern Ireland, and it included the establishment of a devolved power-sharing government. From the outset, the new political arrangements challenged political parties to work together collaboratively. Several political controversies led to the collapse of the power-sharing arrangements, with two significant periods of direct rule from Westminster, 2002–2007 and 2017–2020. Throughout the years there have been continued difficulties, with smaller parties having little influence on key decisions and often being excluded from negotiations between the two dominant parties.

Northern Ireland has a growing population, estimated at 1.88 million in the most recent census (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency [NISRA], Citation2021). The ‘start-stop’ politics of Northern Ireland, which often result in legislative stagnation and continued difficulties in implementing policies on a range of social issues including health, education, and social care, are borne out as the ongoing failures of the government. Gray et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) record in Peace Monitoring Report 5 that socio-economic challenges remain for the people of Northern Ireland:

There are persistent, and in some cases, growing inequalities in relation to socio-economic conditions, educational attainment, and health status in Northern Ireland … There has been little change in poverty rates over the past decade.

At the time of writing, one in five people in Northern Ireland has a disability or long-term illness, with mental ill health recorded as the largest single cause of illness (Betts & Thompson, Citation2017). Bunting et al. (Citation2013) indicate that there is an association between mental ill health and conflict-related trauma in Northern Ireland. This research corroborates one of the key findings of Ferry et al. (Citation2008, p. 63), that ‘PTSD is a specific and significant health need in Northern Ireland’s adult population’. O’Neill and O’Connor (Citation2020) concur, adding that the continued elevation of PTSD rates in Northern Ireland exacerbates individuals’ mental health problems, resulting in the likelihood of experiencing suicidal thoughts. Early intervention programs are significant factors in mitigating these risks (McLafferty et al., Citation2019).

Gray and Birrell (Citation2013) lament the persistent inequalities of the social care system in Northern Ireland, which has been severely affected by funding cuts, austerity, and a complex system of eligibility and means testing. All of these elements have resulted in repeated calls for transformation, innovation, and a more equitable approach to social care for the people of Northern Ireland. Carers (Citation2019) reported an increase in the number of family members providing unpaid care in Northern Ireland, inconsistencies in accessing carers’ assessments, and no resources being provided to address needs and risks when a carer’s assessment was completed. The report identifies carers in Northern Ireland as having significantly lower ‘life satisfaction and happiness and twice the Northern Ireland average of anxiety levels’ (Citation2019, p. 12).

Northern Ireland has the worst hospital waiting times in the United Kingdom (Black et al., Citation2021; DoH, Citation2023). The absence of a functioning Northern Ireland Executive creates a decision-making vacuum which impacts on people and communities.

The development of social work education in Northern Ireland

The regulation of social work education is devolved across the UK, with each of the four professional councils, England (Social Work England), Wales (Social Care Wales), Scotland (Scottish Social Services Council), and Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland Social Care Council) adopting their own standards of conduct and practice. Banks (Citation2012, p. 107) discusses the nuances of the UK-wide introduction of regulators for the social work profession in 2001 as a move toward recognition and status. However, she asserts that regulation came at a price: ‘increasing state control and a focus on controlling the conduct of individual social workers’.

Social work education in Northern Ireland is unique within the four nations owing to the contested histories and conflict associated with the Troubles. The introduction of the degree (2004) coincided with a new era in Northern Ireland as an emerging post-conflict society (MacDermott and Campbell, Citation2015). The introduction of the Framework Specification for the Degree (Northern Ireland Social Care Council [NISCC], Citation2003a) places a mandatory requirement on the social work curriculum to include learning and teaching on the impact of past and current violence ‘in the education and training of social work students’ (NISCC, Citation2003a, p. 6). Furthermore the creation of the Northern Ireland Post Qualifying and Training Partnership (1993) situated Northern Ireland as the first part of the United Kingdom to establish a post-qualifying partnership with employers and academic institutions. This partnership, now named the Professional in Practice Partnership Committee following several iterations, remains the bedrock of post-qualifying social work education three decades later.

Campbell et al. (Citation2021) in their retrospective study of social worker’s experiences during the Troubles explore the significant challenges and trauma many practitioners encountered. Social workers were working in communities often polarized by religion and sectarian violence, many reflected on the invaluable support from peers and colleagues as they tried to navigate and practice in communities with contested histories and identities. Campbell et al. (Citation2019) posit that for some social workers, their experience of working through political conflict lends itself to more politically aware and activist approaches to social work. This resonates with earlier work (Pinkerton & Campbell, Citation2002, p. 724) which presents a tiered model of analysis of the ‘state’, ‘civil society’, and ‘professional ideology’ to debate how social justice can be embedded in the professional identity of social workers during ongoing and oftentimes stagnated processes of post-conflict resolution. Pinkerton and Campbell’s (Citation2002) analysis illuminates the contrast between the national and international bodies in emphasizing and promoting social justice approaches which are core to the global definition of social work (International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW], Citation2014).

The Northern Ireland Social Care Council (NISCC) is responsible for the overarching regulation and governance of the profession in Northern Ireland, including undergraduate and postgraduate education (NISCC, Citation2019c). Social work has been a regulated profession in Northern Ireland since 2005 and social worker is a protected title. In contrast, in the Republic of Ireland, the title of social worker has been a protected professional title since 2013 (Irish Association of Social Workers [IASW], Citation2020).

Heenan and Birrell (Citation2011, p. 104) reflect on the compatibility of professional qualifications in social work with a specific emphasis on Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland which ‘share a common history and legacy’. At that time challenges and issues were noted in relation to recognizing the Northern Ireland social work qualification in the Republic of Ireland. These issues impacted cross-border employment mobility for social workers who qualified in the North. Brexit has had a further huge impact on cross-border registration with social workers on the Island of Ireland required to hold dual registration to practise legally in both jurisdictions (NISCC, 2022). This has required cohesive systems in place from universities, regulators, and employers to ensure regulations are met and all island services including safeguarding and protection of children are sustained.

The BSc (Hons) degree in social work in Northern Ireland is reviewed every five years by the Northern Ireland Social Care Council (NISCC). Since the introduction of the degree in 2004, three periodic reviews have been completed and their results have been disseminated to key stakeholders (NISCC, Citation2009, Citation2014, Citation2019a).

The Department of Health commissions the number of placements with each of the key practice learning opportunity providers, including all five Health and Social Care Trusts, the voluntary sector, the Education Authority, and the justice sectors (Probation Board for Northern Ireland and Youth Justice Agency). This consists of approximately 500 placements per year across level two (85 days) and level three (100 days) placements.

Social work education and professional learning do not stop at the point of graduation, and students must complete an Assessed Year in Employment (AYE) in Northern Ireland. This is formal additional support for newly qualified social workers as they continue to form and shape their professional identity and complete the transition from education to employment; professional regulation is a condition of successful completion. The AYE should ensure that newly qualified staff caseloads are protected, supervision is frequent and space is created to promote and support reflexivity.

There is recognition by the profession’s regulators throughout the UK of the significance of the formative first year in practice as a newly qualified social worker. In England, newly qualified social workers must complete the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment (AYSE) (Social Work England, Citation2020), and in Wales, the Compulsory Consolidation Programme is the designated requirement for early career social workers as part of their PQ framework of Continuing Professional Education and Learning (Social Care Wales, Citation2020). In Scotland, work is at an advanced stage to develop a supported year in employment for newly qualified social workers following a review and several pilot projects (Scottish Social Services Council, Citation2020).

Northern Ireland diverges from the rest of the UK regarding its Professional in Practice (PiP) continued professional development (CPD) framework. The pathways in the framework are integrated with practice-based learning and academic awards and are available to all registered social workers throughout their careers. This is embedded into registration, so, for example, the renewal of professional registration after AYE is conditional on successfully completing two requirements of the Professional in Practice consolidation award within three years (NISCC, Citation2020a). As a comparison, in the Republic of Ireland, the Social Workers Registration Board has mandated that social workers must obtain 30 CPD credits in every 12-month period as the requirement to evidence compliance with the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (Social Workers Registration Board, Citation2019).

Methodology

Policy mapping applies the techniques of content analysis as a research methodology which can be conducted with reports, regulations, legislation, and social policies (Burris et al., Citation2010). Brown et al. (Citation2022) emphasizes the importance of policy mapping as a research tool for social work. The author adapted the eight-stage model presented by Burris et al. (Citation2010). As the sole researcher policy mapping is a time-consuming process and requires deep reading of policy documents, legislation, occupational standards, Department of Health circulars and reports. The methodology employed six stages: (1) research question, (2) identifying data sources, (3) inclusion and exclusion criteria, (4) data collection, (5) reliability and accuracy and (6) dissemination. The author is a social work academic at a university in Northern Ireland and therefore acknowledges their ‘insider status’ (Braun & Clark, Citation2013; Bryman, Citation2016). Drafts of the chronology were shared with the Northern Ireland Social Care Council and the Chief Social Worker for Northern Ireland.

The chronology is iterative and will need to be consistently updated to maintain currency as a resource illustrating how policy, regulations, legislation, and professional frameworks have shaped the professional education of social workers in Northern Ireland at pre and post-qualifying levels.

The chronology presented in outlining the history of the development of social work education in Northern Ireland from 1962 to 2020 is a significant and useful contribution to knowledge offering a detailed history of the key developments in social work education.

Table 1. The history and development of social work education in Northern Ireland from 1962 to 2020.

Discussion: (re)shaping social work education in Northern Ireland

Building on the descriptions of the policy, law, and practice developments included in the chronology () this section will briefly highlight some key shifts in policy and practice developments as they relate to social work education in Northern Ireland.

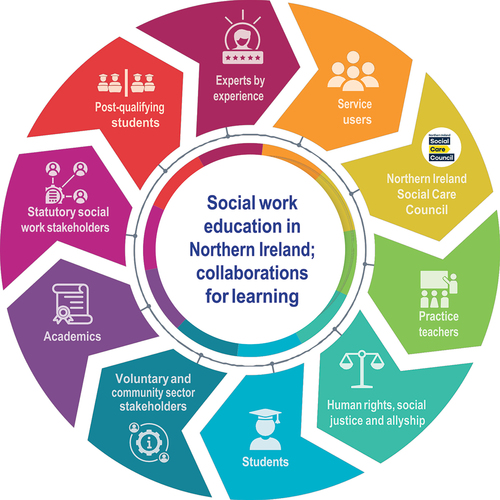

Philip (Citation1978, p. 93) argues that social work originated between the discourses of wealth and poverty. Many commentators have considered the evolution of social work as a profession since Philip’s (Citation1979) work, including Jordan (Citation2004), McLaughlin (Citation2005), and Singh and Cowden (2009). Parton’s earlier work (Parton, Citation1996, 1998) suggests that the bifurcation of the profession meant that it moved away from being concerned with the relations between those perceived to be deserving and the undeserving, and this was largely attributed to capitalism and the role of the markets. It has been suggested that continuing levels of bureaucracy and administration continue to diminish the relational aspect of social work (BASW, 2012; Ingram & Smith, Citation2018). Managerialism and increasing levels of bureaucracy have also been linked to weakening the professional identity of social workers (MacDermott, Citation2019; Ball, 2016; Laming, 2005; Munro, 2011; Singh & Cowden, 2009). Ioakmidis and Wylie (Citation2023, p. 17) posit that ‘social work should draw its legitimacy and recognition from the communities it works with, rather than the artificially prescribed hierarchies it operates within’. represents the author’s interpretation of the constellation of voices and communities collaborating in social work education in Northern Ireland.

Social work education and political conflict in Northern Ireland

An awareness of the impact of conflict, sectarianism, and trauma is critical to developing a more nuanced understanding of the realities and the learning landscape occupied by social work students in Northern Ireland (NISCC, Citation2015b). In Northern Ireland, negativity toward ethnic minorities and immigrants is a societal problem, and a strong correlation has been identified between sectarianism and racism (Doebler et al., Citation2018, p. 15). Human rights are not explicitly mentioned in the Northern Ireland Framework Specification (NISCC, Citation2015b). It can be argued that the social work profession’s commitment to social justice and human rights remains an anchor of credibility to ensure that the most disadvantaged in society have their rights and interests protected and promoted. The importance of human rights in social work education and practice, especially at a time when human rights and civil liberties are increasingly under threat from Brexit and a political landscape where conservative ideologies sustain an increasingly hostile environment for refugees and migrants (Harms-Smith et al., Citation2019; Luthra, Citation2021).

Learning to become a professional in social work in Northern Ireland has the added complexity of trying to navigate our contested histories and understand the impact of sustained political conflict on citizens and communities. Brewer et al. (Citation2010) write about the culture of silence that exists in Northern Ireland as a means of avoiding dealing with the legacy of the past. However, there is rich learning to be gained for social work students, practice teachers, service users, and experts by experience and academics from the conduct of research in a society wrestling with issues associated with conflict, social division, and trauma.

Campbell et al. (Citation2021) call for increased opportunities in qualifying social work programs for dialogue and debate on people’s and communities’ experiences of the conflict and the wider context of identity. Creating ‘safe spaces’ to explore contrasting experiences and how this shapes identity. Within social work education in Northern Ireland, exploration of our shared histories and the conflict in and about Northern Ireland are often only done by individual champions in higher education institutions (HEIs) or practices who are prepared to grasp the nettle and discuss complex intergenerational histories and identities with students (Campbell et al., Citation2021; Duffy et al., Citation2019).

Campbell et al. (Citation2013) return to neutrality as a practice approach for social workers working in conflict, yet this is not without challenge and can create a disconnect between internal identities which can impact meaningfully engaging in wider social justice and human rights issues. This resonates with Ioakmidis and Wylie (Citation2023, p. 14) commenting that ‘practitioner complicity in oppressive practice usually operates under the guise of technocratic neutrality’. Duffy et al. (Citation2019) explore the role of social workers during the Troubles between 1969 and 1998. This innovative research explores the impact of sectarianism, racism, and prolonged inequalities during this period and the occupational space encountered by social workers. Many of them were struggling to engage in social justice and human rights approaches whilst trying to adhere to apolitical, neutral stances to remain safe and reduce the risk of threat or harm from paramilitaries.

Campbell et al. (Citation2019), in their comparative study of social work and political conflict in Northern Ireland, Cyprus, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, identify contested histories, politics, and social divisions, and the nature of the conflict as key factors to explore in their effort to understand social work and political conflict. In earlier work by Smyth and Campbell (Citation1996), the impact of sectarianism on social work education was explored. Examining the ways in which political conflict impacts personal and professional identities in Northern Ireland is presented in the work of Campbell and Healey (Citation1999). Social work education in Northern Ireland has a significant and innovative contribution to make to the wider national and international profession. The issues of sectarianism and the divisions and silos in which many remain entrenched can influence a wider understanding of the complexities of practicing social work in other fractured, contested, and conflicted societies.

Reforming social work education

MacDermott and Campbell (Citation2015) reflects on the ongoing reforms of social work education which were taking place in the United Kingdom (Croisdale-Appleby, Citation2014; Narey, Citation2014). Carpenter et al. (Citation2015) analysis of newly qualified social workers concludes that their experiences of placement varied significantly and that experience of a fieldwork placement in a statutory children’s team did not necessarily prepare students for postgraduate employment in child protection teams. These reports and publications were significant in preparing for the third periodic review of the Degree (NISCC, Citation2019a) specifically tries to clearly define stakeholders’ expectations on the core competencies and skills required at the point of qualification in Northern Ireland. Meaningful service user involvement in social work education has been the focus of sustained emphasis in the delivery of the degree and was included as a recommendation (again) in 2019.

Service user involvement

In the United Kingdom, service user involvement in the delivery of social work degrees has been a requirement since 2003 (NISCC, Citation2003a; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2004). Service user involvement has remained a recommendation, and there has been repeated emphasis on it in subsequent reviews of social work degrees in Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland Social Care Council, Citation2009, Citation2014, Citation2019b). In Europe, service user involvement and inclusion is a central component of social work education and is noted in the literature. Examples of this are the use of participatory action projects in Sweden and Norway (Angelin, Citation2015), the creation of conceptual frameworks for service user involvement in Germany (Laging & Heidenreich, Citation2019), social change projects in Italy and Slovenia (Ramon et al., Citation2019) and participatory approaches to service user research and service user narratives in social work education in Ireland (Flanagan, Citation2020; Sapouna, Citation2021). In Northern Ireland Duffy et al. (Citation2019) Quality Improvement Plan to Widen the Involvement of Service Users and Carers in the NI Degree in Social Work (2018–2021) reflected on the legislative, policy, and research contexts in addition to core messages from a co-produced conference ‘Learning through listening: Service User and Carer Involvement in Social Work Education’ (May 2018). These formed the basis for the Good Practice Guide for Service User Involvement (NISCC, 2020) establishing a benchmark for meaningful involvement and the importance of shared responsibilities from all stakeholders to ensure that the service user voice is central to educating social workers in Northern Ireland.

Meaningful involvement of service users in social work education (Cabiati & Levy, Citation2021; Doel & Best, Citation2008; Driessens et al., Citation2016; Pearl et al., Citation2018; Robinson & Webber, Citation2012; Tanner et al., Citation2017) and the challenges that can hinder their involvement (Davis & Mirick, Citation2021; Doel & Best, Citation2008; MacSporran, Citation2014; Rooney et al., 2016) are central themes in the wider literature.

Practicing in a digital world

The significance for social workers to develop skills to practice in the digital world was cited as a strategic priority in the Learning and Improvement Strategy (DoH, 2019– 2027). In Northern Ireland, the Health and Social Care Board (HSCB) established the Digital Capability Framework (HSCB, 2014) as part of an ongoing ten-year transformation project. However, the Department of Health, Northern Ireland Social Care Council, social work placement providers, families, communities, and HEIs could not have anticipated the accelerated pivot to online provision of social work education in Northern Ireland by the spring of 2020. Boin (2009) writing about the implications for policymaking in responding to crises, identifies technology as a potential threat agent, albeit one that creates accelerated and potentially revolutionary possibilities to impact humanity.

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted the ways in which social work education and placements have been delivered, prompting opportunities for alternative and creative ways of delivering professional education. Safe remote working and digital skills were identified as the top two capacity-building and innovation needs of the voluntary and community sectors during COVID-19 (NICVA, 2021). The respondents to the research published in the MacDermott and Harkin-MacDermott (Citation2021) indicated a willingness to use technology when it became clear that remote delivery of social work education was a certainty. Reamer (Citation2013) writing about the use of technology for social work education suggests that educators must be aware of ‘technology-based pedagogy’ (Reamer, Citation2013, p. 423). Finlay et al. (Citation2022) set out the distinction between virtual and blended learning. Virtual learning takes place outside the traditional lecture environment, in contrast, blended learning is defined as the integration of virtual learning with opportunities for in-person teaching. Social work is an applied degree and the Covid-19 pandemic required a seismic shift in learning delivery models in universities and with placement providers. Pink et al. (Citation2022, p. 413) posit ‘hybrid digital social work should be a future-ready element of practice, designed to accommodate uncertainties as they arise’. Their important study moves beyond a polarized view of face-to-face versus digital learning, acknowledging the opportunities offered by a hybrid approach, and the increasing reality that in citizen’s lives ‘there is a digital element to almost everything we do’ (p. 419). Pink et al. (Citation2022) suggest building on learning from the pandemic and specifically social workers’ use of technology to create a framework that is agile and adaptable and one that can support practitioners and students to ‘better evaluate when and how digital technologies and media will best support their practice and judgements’ (p. 427).

This shift in policy relating to the initial impact of the pandemic is reflected in the revised Practice Learning Requirements for the Degree published by NISCC (2020b). Social work education in the post-pandemic world will face many new challenges in utilizing technology in applied professional education.

Conclusion

This article has focused on the specificity of social work education in Northern Ireland, including the distinctive social, political, and geographical context of social work in a post-conflict context. Using an adapted model of policy mapping (Burris et al., Citation2010) the author presents an original outline of the development and history of social work education from 1962 to 2020 (58 years) including an author interpretation of the constellation of voices collaborating in social work education in Northern Ireland (). The chronology offers a valuable summary of social work education and can be used by others to build and develop as Northern Ireland enters a further period of change and uncertainty in a post-pandemic world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Denise MacDermott

Denise MacDermott is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Ulster University. Her research interests include social work education; specifically collaborations for learning with experts by experience and voluntary sector social work in Northern Ireland.

References

- Angelin, A. (2015). Service user integration into social work education: Lessons learned from Nordic participatory action projects. Journal of Evidenced Informed Social Work, 12(1), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2014.960248

- Banks, S. (2012). Ethics and values in social work, practical social work (4th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- The Belfast Agreement: (Good Friday Agreement). (1998). Agreement reached in the multiparty negotiations. Belfast: The Stationery Office.

- Betts, J., & Thompson, J. (2017). Mental health in Northern Ireland: Overview, strategies, policies, care pathways, CAMHS and barriers to accessing services. Research and Information Service, Northern Ireland Assembly.

- Black, L. A., Regan, E., & Cipriano, M. (2021). The unhealthy state of hospital waiting lists: What we know, don’t know and need to know. Research and Information Service, Northern Ireland Assembly.

- Bowen, E., Irish, A., & Lightfoot, E. (2022). A policy mapping primer for social work researchers and advocates. Social Work Research, 46(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svab029

- Braun, V., & Clark, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Breen-Smyth, M. (2012). Injured in the troubles: The needs of individuals and their families. Wave Trauma Centre.

- Brewer, J., Higgins, G. I., & Teeney, F. (2010). Religion and peacemaking: A conceptualisation. Sociology, 44(6), 1019–1037. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510381608

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bunting, B. P., Ferry, F. R., Murphy, S. D., O’Neill, S. M., & Bolton, D. (2013). Trauma associated with civil conflict and posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the Northern Ireland study of health and stress. Journal of Trauma Stress, 26(1), 134–141. PMID: 23417880 https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21766

- Burke, E. (2016). Who will speak for Northern Ireland? The RUSI Journal, 161(2), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2016.1174477

- Burris, S., Wagenaar, A. C., Swanson, J., Ibrahim, J. K., Wood, J., & Mello, M. M. (2010). Making the case for laws that improve health: A framework for public law research. Millbank Quarterly, 88(2), 169–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x

- Cabiati, E., & Levy, S. (2021). ‘Inspiring conversations’: A comparative analysis of the involvement of experts by experience in Italian and Scottish social work education. British Journal of Social Work, 51(2), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaaa163

- Campbell, J., Duffy, J., Toscone, C., & Falls, D. (2021). ‘Just get on with it’: A qualitative of study of social workers’ experiences during the political conflict in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Social Work, 51(4), 1314–1331. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab039

- Campbell, J., Duffy, J., Traynor, C., Coulter, S., Reilly, I., & Pinkerton, J. (2013). Social work education and political conflict: Preparing students to address the needs of victims and survivors of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. European Journal of Social Work, 16(4), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.732929

- Campbell, J., & Healey, A. (1999). ‘Whatever you say, say something’: The education, training and practice of mental health social workers in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 18(4), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479911220391

- Campbell, J., Ioakimidis, V., & Maglajlic, R. A. (2019). Social work for critical peace: A comparative approach to understanding social work and political conflict. European Journal of Social Work, 22(6), 1073–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1462149

- Carers, N. I. (2019) The state of caring report. A snapshot of unpaid care in Northern Ireland. Belfast. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://www.carersuk.org/northernireland/news-ni/state-of-caring-in-northern-ireland-2019

- Carpenter, J., Shardlow, S., Patsios, D., & Wood, M. (2015). Developing the confidence and competence of newly qualified children and family social workers in England: Outcomes of a national programme. British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct106

- Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work. (1989). Assuring quality in the diploma in social work: Rules and requirements for the DipSW.

- Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work. (1990). The requirements for post qualifying education and training in the personal social services: A framework for continuing professional development.

- Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care in England. (2014). A new settlement for health and social care. Kings Fund.

- Croisdale-Appleby, D. (2014). Revisioning social work education: An independent review. Department of Health. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from www./assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/285788/DCA_Accessible.pdf

- Darby, J., & Williamson, A.(Eds). (1978). Violence and the social services in Northern Ireland. Heinemann.

- Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). Covid-19 and social work field education: A descriptive study of student’s experiences. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(1), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929621

- Department of Health. (2019). A learning and improvement strategy for social workers and social care workers (2019–2027).

- Department of Health. (2023). My waiting times, Northern Ireland. Retrieved September 16, 2023, from https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/news/my-waiting-times-ni

- Department of Health and Social Services Northern Ireland. (1991). Health and personal social services: A regional strategy for Northern Ireland 1992–1997. HMSO.

- Department of Health and Social Services Northern Ireland. (2005). Good practice in consent – Social work students.

- Department of Health and Social Services Northern Ireland. (2012). Improving and safeguarding social wellbeing - a strategy for social work in Northern Ireland.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. (2006a). Assessed year in employment (AYE) of newly qualified social workers. Social Services Inspectorate.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. (2006b). Personal social services development and training 2006–2016.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. (2006c). Standards for practice learning for the degree in social work. DHSSPS.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. (2010). Degree in social work: A regional strategy for practice learning provision in Northern Ireland (2010–2015).

- Doebler, S., McAreavey, R., & Shortall, S. (2018). Is racism the new sectarianism? Negativity towards immigrants and ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland from 2004 to 2015. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(14), 2426–2444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1392027

- Doel, M., & Best, L. (2008). Experiencing social work; learning from service users. Sage.

- Driessens, K., McLaughlin, H., & Van Doorn, L. (2016). The meaningful involvement of service users in social work education: Examples from Belgium and the Netherlands. Social Work Education, 35(7), 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1162289

- Duffy, J., Campbell, J., & Tosone, C. (2019) Voices of social work through the troubles (Publication arising from workshop, 21 November 2019). BASW NI and NI Social Care Council.

- Duffy, J., MacDermott, D., & Lytle, J. (2018). A quality improvement plan to widen the involvement of service users and carers in the Northern Ireland degree in social work. Northern Ireland Degree Partnership in Social Work.

- Ferry, F., Bolton, D., Bunting, B., O’Neill, S., Murphy, S., & Devine, B. (2008) The economic impact of post-traumatic stress disorder in Northern Ireland. A report on the direct and indirect health economic costs of post traumatic stress disorder and the specific impact of conflict in Northern Ireland. Lupina Foundation.

- Finlay, M. J., Tinnion, D. J., & Simpson, T. (2022). A virtual versus blended learning approach to higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: The experiences of a sport and exercise science student cohort. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 30, 100363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100363

- Flanagan, N. (2020). Considering a participatory approach to social work – service user research. Qualitative Social Work, 19(5–6), 1078–1094. https://doi.org/10.1.1177/1473325019894636

- Gray, A. M., & Birrell, D. (2013). Transforming adult social Care. Policy Press.

- Gray, A. M., Hamiliton, J., Kelly, G., Lynn, B., Melaugh, M., & Robinson, G. (2018) NI peace monitoring report: number five. Community Relations Council.

- Griffiths, R. (1988). Community care: Agenda for action: A report to the Secretary of state for social services (R. Griffiths, Ed.). HMSO.

- Hamber, B., & Kelly, G. (2018). Northern Ireland: Case study. In Kofi Annan Foundation and Interpeace (Eds.), Challenging the conventional: Making post-violence reconciliation succeed (pp. 86–130). Kofi Annan Foundation/Interpeace.

- Harms-Smith, L., Martinez-Herrero, M. I., Arnell, P., Bolger, J., Butler-Warke, A., Cook, W., Downie, M., Farmer, N., Nicholls, J., & MacDermott, D. (2019). Social work and human rights: A practice guide. Birmingham.

- Health and Personal social Services Act (Northern Ireland). 2001 C3. HMSO. Health and Personal Social Services Act (Northern Ireland).

- Health and Social Care Board. (2014). Social work research strategy 2015–2020: In pursuit of excellence: Supporting the profession in relation to social work services in Northern Ireland. HSCB.

- Health Visiting and social work (training) Act (1962).

- Heenan, D., & Birrell, D. (2011). Social work in Northern Ireland. Policy Press.

- Ingram, R., & Smith, M. (2018) Relationship-based practice: Emergent themes in social work literature. Retrieved March 20, 2021, from www.iriss.org.uk/resources/insights/relationship-based-practice-emergent-themes-social-work-literature

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2014) Global definition of social work. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Ioakmidis, V. and Wylie, A. (Eds.). (2023). Social work’s histories of complicity and resistance: A tale of two professions. Policy Press.

- Irish Association of Social Workers. (2020). Social work registration. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from www.iasw.ie/Social-Work-Registration

- Jordan, B. (2004). Emancipatory social work? Opportunity or oxymoron. British Journal of Social Work, 34(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch002

- Kelly, G., & Braniff, M. (2016). A dearth of evidence: Tackling division and building relationships in Northern Ireland. International Peacekeeping, 23(3), 442–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2016.1166962

- Laging, M., & Heidenreich, T. (2019). Towards a conceptual framework of service user involvement in social work education: Empowerment and educational perspectives. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1498417

- Local Authority social Services Act (1970).

- Luthra, R. R. (2021). Mitigating the hostile environment: The role of the workplace in EU migrant experience of Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(1), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1726173

- MacDermott, D. (2019). Even when no one is looking: Student’s perceptions of social work professions. A case study in a Northern Ireland university. Education Sciences, 9(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030233

- MacDermott, D., & Campbell, A. (2015). An examination of student and provider perceptions of voluntary sector social work placements in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 35(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1100289

- MacDermott, D., & Harkin MacDermott, C. (2021). Perceptions of trainee practice teachers in Northern Ireland: Assessing competence and readiness to practise during COVID 19. Practice, 33(5), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2021.1904868

- MacSporran, J. (2014). A mentors path: Evaluating how service users can be involved as mentors for social work students on observational practice placements. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 17(3), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1921/swssr.v17i3.798

- McLafferty, M., Armour, C., Bunting, B., Ennis, E., Lapsley, C., Murray, E., & O’Neill, S. (2019). Coping, stress, and negative childhood experiences: The link to psychopathology, self-harm, and suicidal behaviour. Psych Journal, 8(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.301

- McLaughlin, K. (2005). From ridicule to institutionalization: Anti-oppression, the state and social work. Critical Social Policy, 25(3), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018305054072

- The Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order 1986, No. 595, (N.I. 5). HMSO.

- Morrow, D. (2019). Sectarianism- A Review. Ulster University. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from www.ulster.ac.uk/data/assets/pdf_file/0016/410227/A-Review-Addressing-Sectarianism-in-Northern-Ireland_FINAL.pdf

- Muldoon, O. (2004). Children of the Troubles: The impact of political violence in Northern Ireland. Journal of Social Issues, 60(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00366.x

- Narey, M. (2014). Making the education of social workers consistently effective. Department for Education. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/sir-martin-narey-overhauling-childrens-social-work-training

- Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action. (2021). State of the sector. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from www.nicva.org/stateofthesector

- Northern Ireland Post Qualifying Education and Training Partnership. (2007). Partnership handbook.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2002). Standards of conduct and practice for social work students.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2003a). Framework specification for the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2003b). National occupational standards for social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2003c). Practice learning requirements for the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2008). The principles and quality standards for participation.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2009). The five year periodic review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2010). Practice learning requirements for the degree in social work (revised).

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2011). National occupational standards for social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2012). Rules for the approval of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2013). Readiness to practise: A report from a study of new social work graduates’ preparedness for practice: An analysis of the views of key stakeholders.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2014). The second periodic review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2015a). Framework specification for the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2015b). Standards of conduct and practice for social work students.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2016) The annual report and accounts of the Northern Ireland social care council.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019a) Report 14: Review of the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019b). Standards of conduct and practice for social workers.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2019c). Standards of conduct and practice for social work students.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2020a). Good practice guidelines for involving service users in social work education in Northern Ireland.

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2020b). Practice learning requirements for the degree in social work (amended version August-December 2020)

- Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2020c, December). The standards for practice learning for the degree in social work.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. (2021). Belfast. Retrieved March 18, 2021, from www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics

- O’Neill, S., & O’Connor, R. (2020). Suicide in Northern Ireland: Epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30525-5

- Parton, N. (1996). Social work, risk and the ‘blaming society’. In N. Parton (Ed.), Social theory, social change and social work (pp. 98–114). Routledge.

- Parton, N. (1998). Risk, advanced liberalism and child welfare: The need to rediscover uncertainty and ambiguity. British Journal of Social Work, 28(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011317

- Pearl, R., Williams, H., Williams, L., Brown, K., Brown, B., Hollinton, L., Gruffydd, M., Jones, R., Yorke, S., & Statham, G. (2018). Service user and carer feedback: Simply pass/fail or a genuine learning tool? Social Work Education, 37(5), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1420768

- Philip, M. (1979). Notes on the form of knowledge in social work. Sociological Review, 27(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1979.tb00326.x

- Pinkerton, J., & Campbell, J. (2002). Social work and social justice in Northern Ireland: Towards a new occupational space. British Journal of Social Work, 32(6), 723–737. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/32.6.723

- Pink, S., Ferguson, H., & Kelly, L. (2022). Digital social work: Conceptualising a hybrid anticipatory practice. Qualitative Social Work, 21(2), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250211003647

- Ramon, S., Grodofsky, M. M., Allegri, E., & Rafaelic, A. (2019). Service users’ involvement in social work education: Focus on social change projects. Social Work Education, 38(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1563589

- Reamer, F. G. (2013). Social work in a digital age: Ethical and risk management challenges. Social Work, 58(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swt003

- Robinson, K., & Webber, M. (2012). Models and effectiveness of service user and carer involvement in social work education: A literature review. The British Journal of Social Work, 43(5), 925–944. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs025

- Sapouna, L. (2021). Service user narratives in social work education, co-production or co- option? Social Work Education, 40(4), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1730316

- Scottish Social Services Council. (2020). Supporting newly qualified social workers in Scotland. Retrieved September 21, 2021, from https://www.sssc.uk.com/supporting-the-workforce/newly-qualified-social-workers/

- Seebohm Committee. (1968). Report of the committee on local authority and allied personal social services. Cmnd 3703. HMSO.

- Smyth, M., & Campbell, J. (1996). Social work, sectarianism and anti-sectarian practice in Northern Ireland. The British Journal of Social Work, 26(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011074

- Social Care Wales. (2020). Continuing professional education and learning for social workers. Retrieved September 20, 2020, from https://socialcare.wales/cms_assets/file-uploads/CPEL.pdf

- Social Work England. (2020). Qualifying education and training standards guidance. Retrieved September 21, 2021, from https://www.socialworkengland.org.uk/standards/qualifying-education-and-training-standards-guidance-2020/

- Social Workers Registration Board. (2019). Code of professional conduct and ethics. Retrieved July 1, 2021, from www.coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/swrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for-social-workers.pdf

- Tanner, D., Littlechild, R., Duffy, J., & Hayes, D. (2017). ‘Making it real’: Evaluating the impact of service user and carer involvement in social work education. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv121