ABSTRACT

In recent decades, a growing number of professions have integrated online simulation approaches into their higher education programs with a view to optimizing graduates’ practice readiness. The existing research attests to the value of online simulations as a vehicle for building students’ competence and confidence in practice, without the risk of harm to end service users. However, social work as a profession has been relatively tardy in adopting these pedagogies. Although COVID has created an impetus for the accelerated use of online pedagogies globally, the value of online simulations as an alternative to face-to-face teaching approaches remains contested and social work-specific literature on these approaches is still emerging. With a view to contributing to this fledgling area of scholarship, this paper reports on the development of a virtual, interactive clinic as the main platform for preparing Bachelor of Social Work students for practice in the context of placement. After providing an overview of how the Clinic was developed and implemented, the paper articulates the Clinic’s purpose, scope and functionality as a learning and assessment platform. The paper concludes with a precis of the key lessons learnt with a view to informing future work in the integration of online simulation-based learning in social work education.

Introduction

The social work profession has a longstanding affiliation with experiential learning approaches. Case studies, practice demonstrations and student-to-student role plays permeate practice skills classes since the formalization of social work education (Dodds et al., Citation2018). More recently, social work has broadened its experiential learning repertoire to include simulations, as a way to immerse students in practice situations that approximate real life. Unlike traditional roleplays, simulations typically use standardized clients and often involve trained actors who bring a level of emotional intensity to the learning that emulates real-world practice interactions (Baker & Jenney, Citation2023; Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020; Roberson, Citation2020). Egonsdotter and Israelsson (Citation2022) identified two distinct types of simulation in social work: human-based simulation involving in-person interactions with one or more trained actors in real time; and computer-based or virtual simulations where interactions occur online, in virtual practice environments with digitally enabled virtual clients.

Social work has used human-based simulations predominantly for teaching and/or assessing specialized practice skills such as suicide risk assessment, advance planning in age care and interprofessional care (Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020). The literature suggests that students generally prefer simulations to traditional role plays and experience simulation as a more interactive and practically focused way to develop practice capabilities. Students value the opportunity simulations provide to test their practice capabilities and learn by making mistakes without adversely impacting real clients (Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020). However, the research also identifies that human-based simulation can be time-intensive and costly, that students’ learning experience can vary depending on how individual actors interact with them, and that students can sometimes experience unhelpful levels of performance anxiety if not adequately prepared for the unpredictability of the learning situation (Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020).

The advent of COVID and resulting disruptions to campus-based learning created an impetus for greater use of online learning modes including computer-based simulations (Jefferies et al., Citation2021). Most studies identify that virtual simulations are primarily used in social work to teach generalist direct practice capabilities, namely, core interviewing, assessment and case management in diverse practice settings (Baker & Jenney, Citation2023; Egonsdotter & Israelsson, Citation2022; Huttar & BrintzenhofeSzoc, Citation2020). The available research suggests that virtual simulation benefits student learning in the same ways as human-based simulation; provided that the technology is used ethically, and does not essentialize service users, particularly when using avatars (Egonsdotter & Israelsson, Citation2022). Virtual simulations also have additional benefits. Online delivery creates the opportunity for self-paced practice learning, prolonged engagement with the same simulated clients, and can reduce students’ performance anxiety levels without compromising the authenticity of the learning. Furthermore, virtual simulations enable greater standardization of practice learning experiences, are more accessible and flexible in their delivery and, therefore, more cost and time effective in the long run (Baker & Jenney, Citation2023).

Despite these promising findings, virtual simulation is not yet widely used in social work across nations. Jefferies et al. (Citation2021) Australian-based study identified two key barriers for social work educators: the professional body’s resistance to acknowledging simulation as a legitimate practice learning mode, and the variable investment and expertise in online learning across Australian universities. The social-work specific literature on simulation is only just emerging, with most existing studies reporting on practice developments in Canada and the United States (Baker & Jenney, Citation2023; Egonsdotter & Israelsson, Citation2022; Kourgiantakis et al., Citation2020). There is a need for further research across nations to broaden our understanding of how social work simulation is evolving across contexts.

With a view to contributing to social work’s emerging knowledge of the processes, practices and issues associated with simulation-based learning, this paper reports on the development of a virtual, interactive clinic (the Clinic, herewith) within the Bachelor of Social Work program (BSW) at Deakin University, a regionally based university in Australia. It is important to highlight that the Clinic is a highly contextualized learning innovation, developed to respond to the specific needs of our students within the parameters set by our professional body. With this in mind, the intention of this paper is to introduce the Clinic as an example of authentic learning in social work education, rather than as an educational product wholly transferrable to other social work programs and contexts.

Developing the Clinic: glimpses from behind the scenes

The Clinic was developed after an internal review of our BSW program in 2018 highlighted the need for a sharper focus on placement preparation across campus and online student cohorts. The social work team initiated a meeting with Deakin’s online learning design team to explore the use of interactive, online technologies to strengthen pre-placement curriculum. The meeting established a social work simulation project group that met over a two-year period to develop the Clinic. In consideration of our educational policy context and student demographics, our interest was to develop a simulation platform that would support a combination of group-based synchronous and individual asynchronous practice learning activities across online and on-campus delivery modes. Our aspiration was to enable standardized practice learning experiences in a range of simulated practice settings that reflected the Australian health and human services system, accessible virtually to ensure sustainability over time. We resolved to use real, rather than computer-generated, people as simulated clients to optimize the authenticity of the learning experience and capitalize on the strengths of virtual and human-based simulations.

We started the development process by deciding on practice scenarios and creating multiple story lines for each practice scenario in consultation with our community partners. The various story lines were initially mapped out manually on storyboards to visualize the pathways that each scenario could take. Numerous questions and responses were scripted and generated in Twine®, a free online tool that uses branching technology to create interactive, non-linear stories. Using Twine® enabled us to embed a choose-your-own-adventure dimension to each of the practice scenarios, ultimately enabling students to make choices in their simulated practice, and to experience the impact of their decisions and actions.

Professional actors were selected from a pool of performers that Deakin University regularly uses for simulation purposes, to play the simulated service users, placement supervisors and other workers within each scenario. Prior to filming, each actor was briefed on their character’s past and present life circumstances and how these have shaped their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Actors were provided with a script of the responses they would give to various questions and prompts and directed to vary the emotional intensity of their response depending on the nature and tone of the question or prompt. Actors delivered scripted responses as a series of video monologues, directly to camera to create a sense of immediacy in the students’ Clinic experience. Visual and audio background content was then added to the video excerpts to optimize the authenticity of virtual practice environments. Video excerpts were uploaded to Twine® with the corresponding audio questions and text-based prompts to create the multi-media repository that sits behind Clinic.

The Clinic from the students’ view

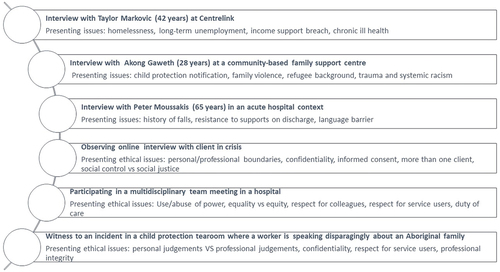

When the student virtually enters the Clinic, they are introduced to six distinctly different practice scenarios in work settings that commonly provide placements and employ social work graduates, namely, government statutory services, community-based organizations and health/hospital networks. Three of the scenarios immerse students in direct practice with simulated service users. The other three place students in ethically challenging workplace situations with implications on their use of self and professional relationships in practice. outlines the scenarios that make up the Clinic.

As they work through each simulation, students are prompted to make choices from a selection of pre-programmed questions. Students’ chosen line of questioning determines how the practice interactions evolve and students only view the video responses related to the questions they choose. With in-excess of 650 questions/responses built into the simulations, students can run each simulation numerous times and have a different learning experience within the same practice scenario.

A simulated supervisor is built into each practice simulation to guide students through four structured learning phases, as outlined in below:

Every simulation begins with the supervisor briefing the student on the practice scenario. Students are then prompted to introduce themselves to the client or worker and select their first question. Upon receiving the corresponding video response, students are offered additional questions to choose from to progress the interaction. The supervisor appears at different points throughout the simulated interaction to provide feedback on progress and suggest ways forward with the line of questioning. At the end of each scenario, the simulated supervisor appears again to provide summative feedback to the student, based on the choices they made, and to ask the student a series of reflective questions to guide their critical reflection on the practice event.

The Clinic learning experience culminates into two summative assessment tasks that test the students’ capacity to articulate their reasoning for particular choices made. The assessments require students to articulate their practice knowledge, to reflect on their own location, emotions and learnings within the practice event, and to identify implications for their future practice.

Assessment based on the simulations requires students to orally present a critical reflection on one of the direct practice interviews and one workplace scenario, imagining that they were presenting the reflection to their placement supervisor during a formal supervision session. Students audio-visually record their practice reflections. Assessors, assuming the role of a placement supervisor, provide their feedback to the student, as an audio-visual recording. The assessors’ feedback focuses on the students’ strengths and areas for development with a focus on demonstrated knowledge, skills, judgments and self-regulation. In this sense, the assessments emulate the type of reflective practice process that students will undertake as part of their supervised practice on placement.

After initial implementation in 2020, we commenced an annual cycle of evaluation to continually enhance the Clinic and its learning impacts. To date, our findings align with those of the existing literature from the student perspective. Most students experience the Clinic as a more authentic learning activity than peer-to-peer roleplays. They report that the Clinic enables them to test and consolidate their professional knowledge and skills in complex practice scenarios, and to build confidence in making professional assessments. Students particularly appreciate that they can access the Clinic and run the simulations several times, at any time and from anywhere. However, students also identify the Clinic is limited in that it does not allow them to design their own questions and/or redirect the interview outside of the pre-programmed questions and pathways. Interestingly, this limitation prompts rich conversations about what questions students would have wanted to ask and why. Furthermore, our evaluations provide some important insights into the extent and ways in which the Clinic potentially supports students’ self-awareness and self-regulation in practice. The process and outcomes of our evaluation research will be reported in future papers.

Concluding remarks: key lessons learnt

There are several pertinent lessons we learnt through this work that are potentially useful for readers contemplating the use of online simulations. Firstly, such projects require an upfront investment of dedicated time, money and technological resources to create the conditions for cutting edge ideas to be translated into viable action. Secondly, such developments require a unique mix of technological expertise, written and visual storytelling, problem solving as well as instructional design abilities that often transcend our capacities as social work educators. In this sense, the experience in this project echoes Jefferies et al. (Citation2021) findings that dedicated resources and expertise are integral to progress simulation-based learning approaches.

However, this project has also highlighted that these foundational inputs are not sufficient to enable the paradigm shift from which the Clinic has emerged. In addition to adequate resourcing and expertise, there needs to be a preparedness to engage in a long-range, iterative process with people who bring a completely different lens to the teaching and learning process. It requires us, as social work educators, to let go of longstanding affiliations with particular ways of teaching, and to commit to engaging openly with diverse knowledges on what constitutes quality education for the future. Most importantly, it requires adjustment, constant self-reflection, the willingness to invest time, well beyond allocated curriculum development hours, and furthermore, to prioritize innovation in teaching and learning above other academic metrics, particularly in the development and initial implementation phases.

Another key lesson learnt is that it is not workable for us, as academics, to conceptualize the learning as a product and then hand over to the online experts to put our ideas into action. At the same time, it is not feasible for us to rely on the online learning experts to source, import and replicate learning innovations with an expectation that these will meet our specific needs. These projects require sustained engagement in a collaborative process of discovery and learning, with a view to co-creating new approaches that are continually reviewed as new technologies emerge.

Ultimately, we learnt that the upfront investment of time, people and resources to integrate authentic learning at a course level translates into less time and energy spent on remedial activities such as placement improvement planning and placement cessations. This contributes to greater student and placement provider satisfaction and creates opportunity to potentially grow both course demand and placement supply. It is notable that our previous placement supply issues have gradually dissipated since the Clinic was established as the central plank in our pre-placement learning and assessment approach. Our experience is that placement capacity increases as organizations discover the benefits of hosting students who are well prepared to engage with the emerging tensions, uncertainty and ambiguity in real-world practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the significant contribution of Deakin University’s social work academics, online designers, creative producers, IT professionals involved with the Clinic project including (in alphabetical order): Tim Crawford, Associate Professor Sophie Goldingay, Peter Lane, Dr James Lucas, Jodie Satour, Darci Taylor, David Williams, Brett Wilson and Rusi Zhang. This project would not have been possible without the collective knowledge, skills, enthusiasm and commitment of these people. The authors also acknowledge the invaluable contribution of industry partners and students in the development and ongoing enhancement of the Clinic.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no known actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to the work reported in this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sevi Vassos

Sevi Vassos, PhD is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work and Academic Lead in Field Education at Deakin University. Her research is primarily focused on social work education. She is particularly interested in the development of evidence-informed learning and teaching approaches focused on preparing students for complex practice.

Michelle Hunt

Michelle Hunt, PhD is a Lecturer in Social Work and Academic Lead in Social Work Field Education at Deakin University. Michelle’s primary research interests are in social work education and participatory approaches to social work education, research and practice.

References

- Baker, E., & Jenney, A. (2023). Virtual simulations to train social workers for competency-based learning: A scoping review. Journal of Social Work Education, 59(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2022.2039819

- Dodds, C., Heslop, P., & Meredith, C. (2018). Using simulation-based education to help social work students prepare for practice. Social Work Education, 37(5), 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1433158

- Egonsdotter, G., & Israelsson, S. (2022). Computer-based simulations in social work education: A scoping review. Research on Social Work Practice, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315221147016

- Huttar, C. M., & BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. (2020). Virtual reality and computer simulation in social work education: A systematic review. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1648221

- Jefferies, G., Davis, C., & Mason, J. (2021). COVID-19 and field education in Australia: Exploring the use of simulation. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 31(4), 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2021.1945951

- Kourgiantakis, T., Sewell, K. M., Hu, R., Logan, J., & Bogo, M. (2020). Simulation in social work education: A scoping review. Research on Social Work Practice, 30(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731519885015

- Roberson, C. J. (2020). Understanding simulation in social work education: A conceptual framework. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656587